Abstract

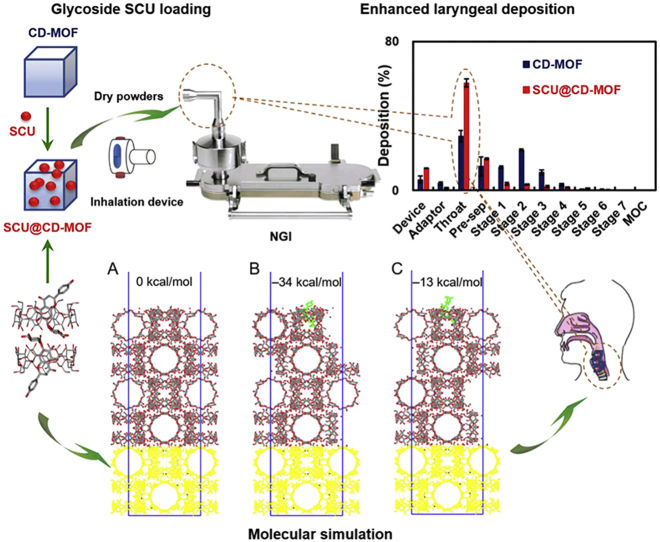

It is essential to develop new carriers for laryngeal drug delivery in light of the lack of therapy in laryngeal related diseases. When the inhalable micron-sized crystals of γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic framework (CD-MOF) was utilized as dry powder inhalers (DPIs) carrier with high fine particle fraction (FPF), it was found in this research that the encapsulation of a glycoside compound, namely, scutellarin (SCU) in CD-MOF could significantly enhance its laryngeal deposition. Firstly, SCU loading into CD-MOF was optimized by incubation. Then, a series of characterizations were carried out to elucidate the mechanisms of drug loading. Finally, the laryngeal deposition rate of CD-MOF was 57.72 ± 2.19% improved by SCU, about two times higher than that of CD-MOF, when it was determined by Next Generation Impactor (NGI) at 65 L/min. As a proof of concept, pharyngolaryngitis therapeutic agent dexamethasone (DEX) had improved laryngeal deposition after being co-encapsulated with SCU in CD-MOF. The molecular simulation demonstrated the configuration of SCU in CD-MOF and its contribution to the free energy of the SCU@CD-MOF, which defined the enhanced laryngeal anchoring. In conclusion, the glycosides-like SCU could effectively enhance the anchoring of CD-MOF particles to the larynx to facilitate the treatment of laryngeal diseases.

Key words: Laryngeal delivery, γ-Cyclodextrin metal-organic framework, Scutellarin, Dexamethasone, Molecular simulation

Graphical abstract

Glycoside scutellarin enhanced inhalable γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic framework particles anchoring in larynx. As a proof-of-concept, dexamethasone co-delivered with scutellarin (SCU) had enhanced laryngeal deposition. Laryngeal deposition of dried powders was evaluated using the Next Generation Pharmaceutical Impactor. Molecular simulation revealed the scutellarin incorporation in CD-MOF and its effect to the surface properties.

1. Introduction

Laryngeal local diseases such as laryngitis, squamous cancer of the larynx, and laryngeal abnormalities need topical drug administration1, 2, 3, 4. As a result of multiple connective tissue barriers in the larynx, a number of studies have focused on the targeting or sustained release system to reduce frequency of multiple dosing and adverse effects. The existing laryngeal deposition strategies mainly include lipids5,6, nanoparticles7,8, throat sprays9, and lozenges10. Lipids and nanoparticles provide a slow-release delivery system for bioactive agents in the larynx, but they are usually limited by rapid clearance and metabolism from the injection site5,11. Further, throat sprays are difficult to use for some patients and may cause gagging or choking reactions. Lozenges are not efficiently delivered to the throat in sufficient concentration as they are readily dissolved and swallowed12. In this context, the deposition of bioactive molecules in larynx tissue or surface would be an attractive strategy for the management of a variety of laryngeal pathologies.

Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) deliver active drugs in powdered form through the oral cavity into the lungs using a special inhalation device13, which have potential advantages in laryngeal delivery. DPIs contain only drug particles without additional propellants and preservatives14, which do not irritate the laryngeal mucosa and upper respiratory tract. Conventional throat sprays deliver the drug by applying pressure with a manual pump, for which the dosages were hard to control due to the lack of coordination between drug release and patient inhalation. However, DPIs have overcome this problem by actively inhaling the powder. Only by passing through the larynx into the respiratory tract, can drug gain access to the pulmonary site of action or absorption. This indicates that the inhalation administration and the larynx are naturally related. Laryngeal administration in powder form is an ancient treatment in traditional Chinese medicine, which requires the patient to open the mouth and sprinkle the powder directly to the larynx. For example, Zhuhuang Chuihou Powder and Qingdai Powder, the ancient herbal medicinal formulas, exert therapeutic effects on sore throat. The fine powders are easy to disperse and quick on-set for the effects. Thus, it is of great interest to optimize the properties of a conventional DPI so as to be transformed for specific laryngeal drug delivery, which would pave the way to the treatment of a variety of local diseases in the larynx.

Cascade impactors are the most widely used device to evaluate the aerodynamic behaviour for DPIs15, 16, 17. Among them, the Next Generation Impactor (NGI), consisting of an artificial larynx, a pre-separator and impactor stages, not only has the characteristics of Andersen Cascade Impactor (ACI), but also has the advantages of fast analysis speed and easier manual operation18, 19, 20. Nowadays, there is still lack of direct and precise methods for in vitro evaluation of laryngeal administration. Perkins et al.21 reported computational fluid dynamics to predict the ideal inhaled particle size range for targeted laryngeal deposition. Wang et al.22 measured powder deposition with an idealized mouth–throat geometry and the powders retained in the filter indicated lung delivery. The in vitro NGI evaluation method to DPIs can be utilized as a surrogate to evaluate laryngeal administration with maximum throat portion and less fine particle fraction (FPF), because the powders pass through the oral cavity via inhalation after the capsule is punctured by the inhalation device23. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) defined throat of NGI as a right angle according to the characteristics of the human larynx, though its internal structure is highly simplified, which is mainly used to simulate the deposition of inhaled powders in the mouth, pharynx and larynx of human body during actual use process. Meanwhile, the emptying rate can be also introduced from DPIs methodology for laryngeal powder systems administered in capsules.

It is well known that high drug deposition in the pharynx and larynx is undesirable and is challenging to be avoided in conventional DPI formulations24. For instance, in the case of inhaled lactose-based DPIs, a considerable part of the carrier lactose deposits in the larynx without being delivered to the lungs25. In most cases, the incorporation of lactose in the carrier is not for improved laryngeal adhesion of drugs but to enhance the powder flowability26,27. Lactose deposits in the larynx mainly due to its large particle size without drug loading capability28. Therefore, it is of great importance to develop the new carrier to achieve the targeted drug deposition and localization of the larynx.

Supramolecular drug carriers made of polymers are constructed based on noncovalent interactions, and can undergo dynamic dissociation under specific external environment stimulation29. In this regard, cyclodextrin metal-organic framework (CD-MOF) has attracted growing attention. CD-MOF is the supramolecular assembly, where γ-CDs are used as building blocks and potassium ions play an auxiliary role in the coordination of (γ-CD)6 cubic cell units and link them to form a whole three-dimensional topological network crystal30, 31, 32. Recently, a number of reports on CD-MOF as a promising drug carrier have emerged to load valsartan33, folic acid34, sucralose35, leflunomide36, resveratrol37, ibuprofen38 and lansoprazole39. However, most of these studies have focused on enhancing the solubility, stability and bioavailability of drugs40,41. It is noteworthy that budesonide has been reported being encapsulated in the pores of CD-MOF as a new inhalers of pulmonary drug delivery due to its uniform inhalation size42. All in all, CD-MOF has the characteristics of special porous for loading of insoluble drugs, uniform controllable cubic morphology and size for quality control and high portability, which provide the basis for inhalable CD-MOF particles as a potential new carrier for laryngeal administration in the field of laryngeal delivery.

In this study, cubic CD-MOF particles with uniform size ranging from 1 to 5 μm were prepared based on our previous work. A natural product flavonoid glycoside, scutellarin (SCU) was successfully incorporated in the CD-MOF to be used as DPIs. It was discovered that SCU can enhance the laryngeal deposition of CD-MOF, opening avenues for their use as a new carrier for laryngeal delivery. Dexamethasone (DEX), an anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid, has therapeutic effects on pharyngolaryngitis by reduction of the contractile response of smooth muscles and edema of the laryngeal mucosa. DEX was assessed as proof-of-concept test for SCU-improved laryngeal deposition when co-delivered in CD-MOF.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Scutellarin was purchased from Xi'an TongZe Biotech Co., Ltd. (Xi'an, China). Dexamethasone was supplied by Dalian Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). γ-Cyclodextrin was acquired from Maxdragon Biochem Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Potassium hydroxide (KOH), methanol (MeOH), ethanol (EtOH), polyethylene glycol 20,000 (PEG 20,000) and glacial acetic acid of analytical grade were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Phosphoric acid (85%–90%) of HPLC grade was purchased from Honeywell Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Methanol of HPLC grade was obtained from J&K Chemical Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Water was purified using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

2.2. Synthesis of CD-MOF

The synthesis protocol for CD-MOF was adapted from a previously reported procedure43. In a nutshell, γ-CD (64.8 g) and KOH (22.4 g) were dissolved in purified water (2000 mL) with a molar ratio of γ-CD to KOH of 1:8. After adding methanol (1200 mL), the reaction mixture was kept in water bath (60 °C) until a clear solution was obtained. PEG 20,000 (12.8 g) was added, conducing to the rapid sedimentation of crystalline particles after further heating the solution for 20 min. The suspension liquid was incubated in ice water overnight, then the CD-MOF crystals were harvested by centrifugation (2826×g, 3 min) and washed with anhydrous ethanol (4% acetic acid) to neutralize the alkaline CD-MOF. Finally, CD-MOF was washed with methanol till reaching a pH about 6.5–7.5, and then dried at 60 °C for 5 h to obtain white powders of cubic crystal particles.

2.3. Preparation of drug-loaded CD-MOF

SCU was loaded in CD-MOF using a simple incubation approach, in which SCU and CD-MOF were mixed in ethanol under the condition of heating and stirring for a period of time. According to the previous trials, the main factors to the loading rate were reaction temperature, molar ratio of SCU:CD-MOF and incubation time. Herein, SCU@CD-MOF was prepared using SCU:CD-MOF molar ratios of 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 5:1 and 10:1, under gentle stirring (400 rpm) at 30, 40, 50 and 60 °C for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 h (RCT basic, IKA, Staufen, Germany). The precipitates were washed thrice with 30 mL of anhydrous ethanol to remove the non-incorporated SCU. The crystals were obtained after being dried in vacuum (DZF-6050, Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 40 °C for 12 h (n = 3). In addition, the physical mixtures of SCU and CD-MOF were prepared by mixing SCU and CD-MOF with the proportion of the optimal SCU loading above.

The preparation of SCU@DEX@CD-MOF was similar to that of SCU@CD-MOF. Generally, DEX and SCU were added into 100 mL ethanol at the molar ratio of 1:1 and 1:2 respectively, and then 726.5 mg of CD-MOF was added. After incubation, the obtained mixtures were washed and thoroughly dried under vacuum. DEX@CD-MOF at the molar ratio of 2:1 was prepared in the same way.

2.4. Determination of SCU loading

HPLC analysis was established on Agilent 1260 (Agilent Technologies, Torrance, CA, USA) using Diamonsil C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) at the column temperature of 40 °C and the injection volume of 10 μL. The mobile phase composed of methanol and 0.1% phosphoric acid (40:60, v/v) whereas the flow rate was at 1.0 mL/min. Spectra was recorded at 335 nm wavelength by UV detector to determine the SCU content.

About 5 mg of dried solid SCU@CD-MOF crystals were accurately weighted (n = 3) and completely dissolved in 25 mL of solvent composed of ethanol and water (2:3, v/v). The SCU payload was measured using the above HPLC method, and calculated by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

2.5. Determination of dexamethasone

DEX was determined using HPLC‒MS/MS, which consisted of an Agilent 1260 liquid chromatograph and an Agilent 6460 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). The detection by the Acquisition software (Agilent Technologies) was as follows: ESI, positive-ion mode, capillary voltage 3500 V; gas temperature 300 °C, gas flow 8 L/min; sheath gas temperature 35 °C, flow 10 L/min; Nebulizer 35 psi. The optimized precursor to product ion transition monitored for DEX was m/z 393.2/373. The mobile phase consisted up acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water (30:70, v/v), a running time of 7 min, 35 °C column temperature, flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and 10 μL as injection volume.

2.6. Characterization

2.6.1. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The mean size and morphology of SCU, CD-MOF and SCU@CD-MOF were determined by SEM (Phenom LE, Phenom Scientific, Shanghai, China). Samples were sprinkled on the conductive glue and coated with gold before observation.

2.6.2. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermal stability of the samples was performed with TGA (Pyris, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MN, USA) in the temperature range from 30 to 600 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen flow rate of 30 mL/min.

2.6.3. Powder X-ray diffractometry (PXRD)

The PXRD analysis was performed to measure the crystallinity of the powders. Diffractograms were collected using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, AL, USA). Powders were irradiated with monochromatized CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) and were inspected at a tube voltage of 40 kV and a tube current of 40 mA at a scan speed of 0.1 s/step in a 2θ angle range of 3°–40°.

2.6.4. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Calorimetric measurements were characterized by DSC (Q2000, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) in the temperature range from 25 to 250 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

2.6.5. Synchrotron radiation Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (SR-FTIR)

SR-FTIR spectra of samples were obtained using a spectrometer (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MN, USA). The dry powders were mixed with potassium bromide at a mass ratio of about 1:10 and compressed under the form of a tablet. Each sample was scanned 64 times at a resolution of 4 cm−1 in a wavenumber range from 400 to 4000 cm−1.

2.7. Molecular mechanism

The molecular structure of SCU was downloaded from the open chemistry database of PubChem (PubChem CID: 6426802). The crystal structure of basic CD-MOF was extracted from the reported single crystal structure of γ-CD-MOF44.

AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 was employed to perform the automatic docking procedure. The Visualizer module in Materials Studio 2017 (MS, Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was employed to perform the model construction and the Forcite module with cvff forcefield in MS was used to carry out the structure optimization. In the structure optimization procedure, the “Ultra-fine” quality was used. Firstly, the hydrogen atom was optimized with the heavy atom fixed; secondly, all of the atoms were optimized with the cell parameters fixed; finally, all the parameters were optimized to make symmetry to P1. The surface preparation procedure: The (0 1 0) surface of CD-MOF was selected as the most stable interface. The vacuum width of 100 Å and a 3-layer slab (totally about 93.018 Å) as the minimum thickness were needed to obtain meaningful results. During the relaxation of the (0 1 0) surface, a slab thickness of one layer (about 31.006 Å) at the bottom of the periodicity box was fixed. Then the optimized SCU structure was located on the most stable surface to obtain two drug-loading surfaces, one was the glucose rings end of SCU inside the (0 1 0) surface, the other one was that outside the (0 1 0) surface.

2.8. Evaluation of laryngeal deposition

2.8.1. Powder flowability

In this experiment, the angle of repose of SCU@CD-MOF was determined by the fixed cone method45, 46, 47. Two funnels with a diameter of 7.0 cm were taken in series on an iron stand. A watch glass with a diameter of 3.2 cm on a horizontal table was placed at a distance of 5.0 cm from the bottom of the funnel. The center of the watch glass was directly opposite the funnel outlet. An appropriate amount of SCU@CD-MOF was poured slowly into the funnel, and let it flow naturally through the two funnels under the gravity until the powders formed a cone and started to overflow from the edge of the watch glass. The height H of the powder cone was measured, and the measurement was repeated for three times. The angle of repose was calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

An appropriate amount of SCU@CD-MOF were filled into the 10 mL graduated cylinder (M1) until its volume read as 9 ± 1 mL, recorded it as V1, weighed as M2. The graduated cylinder was allowed to fall freely from a prescribed height until its volume did not change significantly, which was recorded as the V2. The bulk density (ρb), tapped density (ρt) and Carr's index (CI) were calculated as following Eqs. (3), (4), (5) 48:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

2.8.2. Determination of emptying rate and laryngeal deposition rate

The dosage form of DPIs is usually a capsule, which must be punctured with sharpened pins to release the powders49. Laryngeal administration of powders are inhaled through the oral cavity, and the suction of powders from the mouth is the first step. Therefore, emptying rate is an important indicator for evaluating DPIs50. Firstly, shells of 10 empty capsules were precisely weighed (W1), filled each capsule with SCU@CD-MOF or free CD-MOF 10 mg, and accurately weighed respectively (W2). Then, the capsules were placed one by one into the inhalation device for NGI (NGI-094, Copley Scientific Ltd., Nottingham, UK), the flow rate was set to 65 L/min, the capsule weight was measured after emptying (W3), and the emptying rate was calculated as shown in Eq. (6).

| (6) |

The laryngeal deposition rate was used as an evaluation index to compare the difference between CD-MOF, SCU@CD-MOF, SCU@DEX@CD-MOF and DEX@CD-MOF by NGI. Firstly, the eight impactor stages were successively covered with 1% dimethicone in n-hexane solution to prevent the powder from bouncing back. After n-hexane was dried, about 15 mL of 40% methanol solution was added into the pre-separator. A sample-filled capsule was placed in the inhalation device and the capsule was punctured by pressing the buttons on both sides of the device. The inhalation device was connected horizontally through an adapter to the artificial throat as required. The parameters such as inhalation time were repeated for the measurements of five capsules. After the NGI test was completed, each part was washed with 40% methanol solution and transferred to a volumetric flask and diluted to volume. The concentration of γ-CD was determined using HPLC-ELSD (Agilent 1290, Agilent Technologies), with the drift tube temperature of 70 °C, the N2 pressure of 3.2 bar, and the gain of 10. The InertSustain AQ-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was used for separation with column temperature at 35 °C. The mobile phase was made up of methanol and water (15:85, v/v) at the flow rate of 1.0 mL/min with 5 μL of injection volume. The laryngeal deposition was the ratio of the dose deposited in throat part in NGI to the total dose deposited at all the parts.

3. Results and discussion

First, the preparation of SCU@CD-MOF crystals was optimized to maximize SCU loading. After in depth characterizations, molecular simulation was employed to investigate the configuration of SCU in CD-MOF and its contribution to the surface free energy of SCU@CD-MOF, related to laryngeal deposition. It seemed that glycoside SCU transformed pulmonary inhalable CD-MOF with a particle size of 1–5 μm anchoring in larynx as assessed by in vitro deposition test in vehicles and co-delivery of DEX. Although this strategy needs more in vivo verifications if an approach is available technically and ethically.

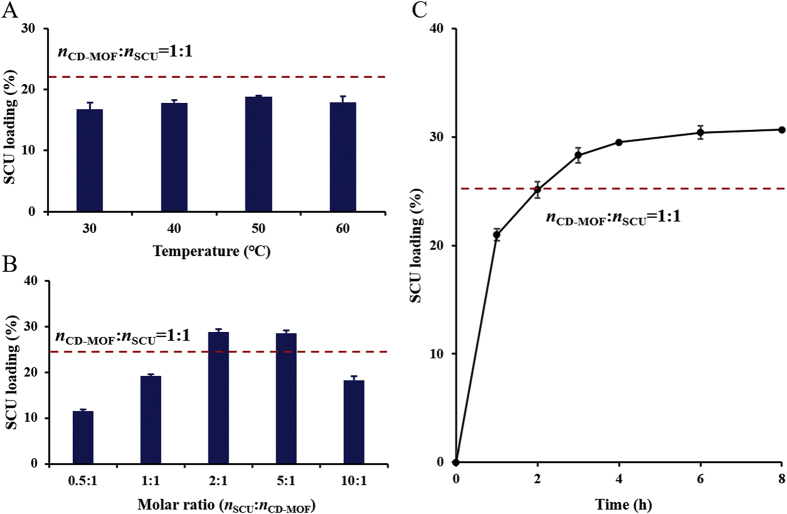

3.1. Loading of SCU to CD-MOF

The payload of SCU in SCU@CD-MOF was determined by an HPLC method. The reaction temperature, time and molar ratio of SCU to CD-MOF were the key parameters that determined the loading efficiency. All these factors were carefully monitored to optimize the loading process. The incubation temperature had the weakest effect on SCU loading (Fig. 1A). For instance, at a molar ratio of 1:1 (SCU to CD-MOF), the lowest and highest drug loadings were 16.75 ± 1.11% at 30 °C and 18.80 ± 0.18% at 50 °C, respectively, with a merely difference of 2.05%. The molar ratio of SCU to CD-MOF played a more important role, reaching maximal values between 2:1 and 5:1 (Fig. 1B). It is of sense to note that the SCU loading was stagnated after extension the reaction time of 4 h, the loading efficiency was 29.51 ± 0.71% at 4 h and 30.42 ± 0.1% at 6 h, with a merely difference of 0.91%. Thus, the reaction time was selected as 4 h (Fig. 1C). In general, the optimal SCU loading was achieved within 4 h through gentle stirring (400 rpm) for molar ratio of SCU to CD-MOF of 2:1, in ethanolic solution at 50 °C.

Figure 1.

The main factors affecting scutellarin loading. (A) Incubation temperature. (B) Molar ratios of scutellarin to CD-MOF. (C) Reaction time. The dashed line represents the loading molar ratio as scutellarin to CD-MOF of 1:1.

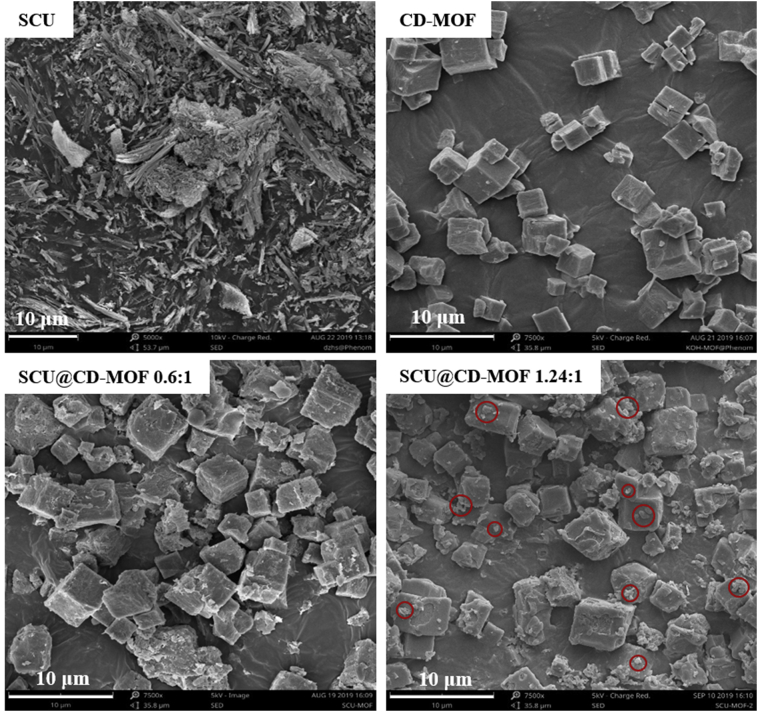

3.2. Characterizations of SCU@CD-MOF

The CD-MOF was cubic crystal with particle size of 1–5 μm, suitable size for inhaled administration, whereas SCU as free drug was long flaky crystals (Fig. 2). Notably, when the SCU loading was 15.68% (the loading molar ratio of SCU to CD-MOF was 0.6:1), the shape of SCU@CD-MOF remained cubic and almost no particles on the surface of CD-MOF could be observed, indicating most of SCU molecules were embedded in CD-MOF. Remarkably, when the maximum loading of SCU was 27.74% (the loading molar ratio of SCU to CD-MOF was 1.24:1), the morphology of SCU@CD-MOF was still cubic with some tiny adhering particles, which are possibly excessive free SCU.

Figure 2.

SEM images of scutellarin (SCU), CD-MOF and SCU@CD-MOF at two molar ratios of SCU:CD-MOF (0.6:1 and 1.24:1).

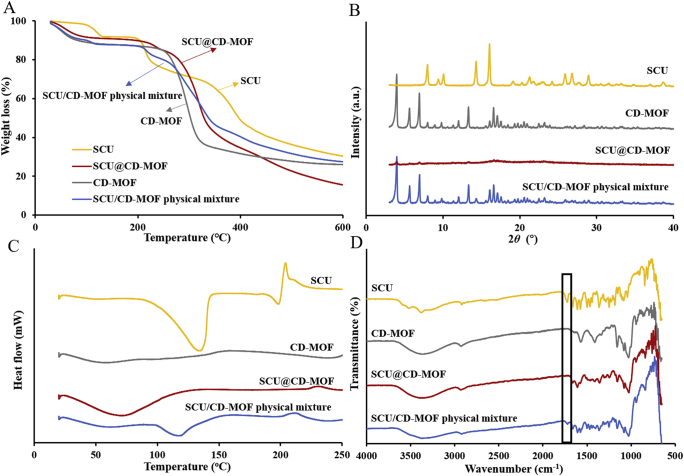

In TGA curves (Fig. 3A), the weight loss of SCU was about 15.8% in the range of 200–260 °C, while the weight loss of SCU@CD-MOF was about 5.3% and the range of weight loss was shifted to high temperature, indicating CD-MOF had a certain protective effect on the thermal stability of the SCU molecules. In addition, the weight loss of SCU@CD-MOF in the range of 200–400 °C was 48.2% and was similar with the weight loss trend of CD-MOF.

Figure 3.

Experimental characterizations confirmed loading of scutellarin in CD-MOF. (A) Thermogravimetric analysis curves. (B) Powder X-ray diffractometry patterns. (C) Differential scanning calorimetry curves. (D) Synchrotron radiation Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra.

PXRD studies showed a dramatic change of SCU crystallinity when incorporated in CD-MOF (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the drug was embedded inside the CD-MOF cavities. The crystalline SCU had intrinsic diffraction peaks (7.97°, 10.06°, 14.31°, 16.05°, 25.90°, 26.80° and 28.93°) that were different from CD-MOFs (3.96°, 5.64°, 6.91°, 13.32°, 16.58° and 17.07°). The physical mixtures of CD-MOF and SCU displayed both peaks. Interestingly, the SCU@CD-MOF had an amorphous structure showing that both the drug and the vehicle lost their crystallinity during SCU loading owing to the super-loading of SCU in CD-MOF34.

To further illustrate the interaction between SCU and CD-MOF, the thermal behaviors of SCU and SCU@CD-MOF were characterized by DSC (Fig. 3C). The pure SCU displayed typical crystalline features with characteristic endothermic peaks at 134.74 and 198.51 °C, and an exothermic peak at 203.84 °C. As a control group, the endothermic peak of SCU still existed in the physical mixture, and the endothermic peak shifted to the low temperature to 118.06 °C. Except for a large and broad endothermic peak at around 70 °C, corresponding to trace solvent (ethanol) evaporation, no significant endothermic and exothermic peaks were observed in SCU@CD-MOF. This result demonstrated that SCU distributed inside CD-MOF was in non-crystalline state and supported the previously hypothesis of SCU insertion into the molecular cavities of CD-MOF.

The changes in bonding between SCU and SCU@CD-MOF were carried out by SR-FTIR (Fig. 3D). The characteristic peaks of SCU were –OH groups at 3000‒3600 cm−1, C–H stretching vibration at 2920 cm−1, C O stretching vibration at 1725 cm−1, benzene skeleton vibration at 1664, 1610 and 1577 cm−1, and C–H out-of-plane bending vibration at 844 and 835 cm−1. The spectrum of the physical mixture was the superposition of SCU and CD-MOF with obvious characteristic absorption peaks. Moreover, the C O stretching vibration peak at 1725 cm−1 of SCU disappeared in SCU@CD-MOF, indicating that strong host–guest interaction between SCU and CD-MOF.

In general, the results of characterizations showed that SCU was successfully loaded to the CD-MOF particles and had a strong host–guest interaction.

3.3. Molecular mechanism

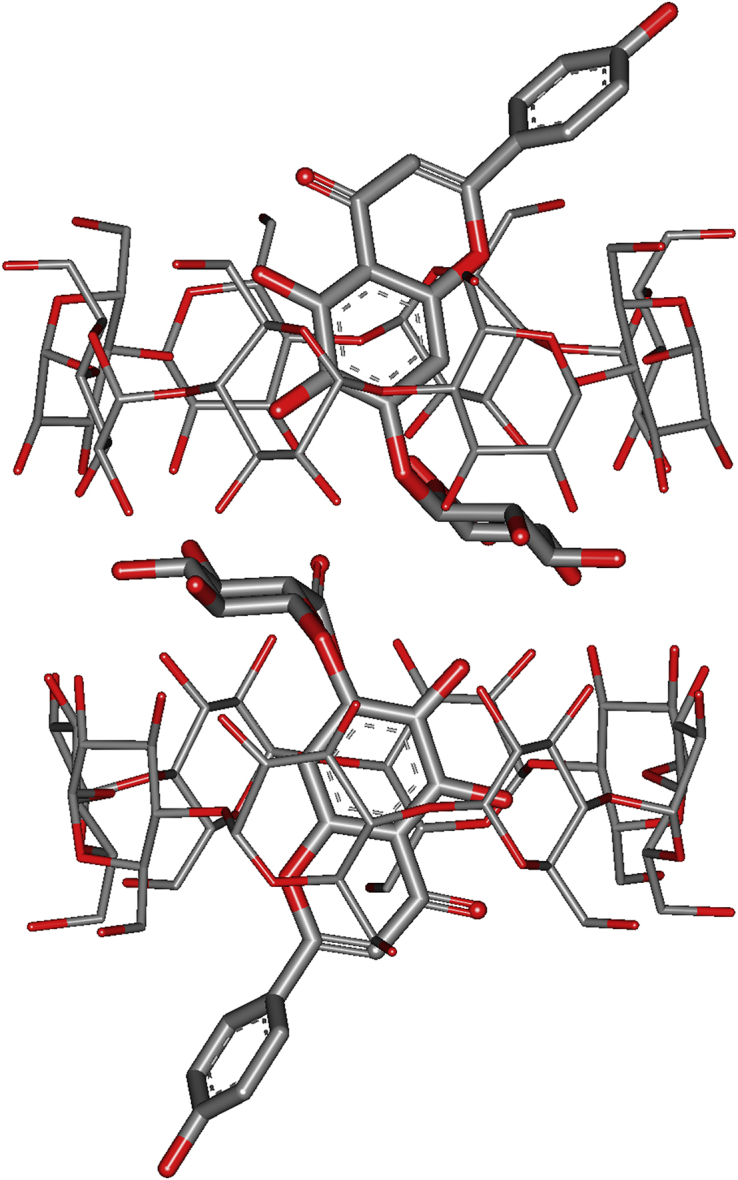

3.3.1. The status of SCU in CD-MOF

In the CD-MOF, the γ-CD molecules were parallelly face-to-face in couples. The polar hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of SCU formed strong hydrogen bonds with the γ-CD in CD-MOF (Fig. 4). As a result, the docking free energy of the first molecule of SCU reached −9.3 kcal/mol, while the docking free energy of the second molecule was −9.2 kcal/mol. The simulation showed that two SCU molecules hardly interacted with each other, which almost completely symmetrically distributed in the bi-cyclodextrin pair.

Figure 4.

Configuration diagram of scutellarin (SCU) molecules in CD pairs of SCU@CD-MOF.

3.3.2. Effect of SCU loading to the flowability of CD-MOF

To benchmark the accuracy of the methods for our calculations, the initial tests were carried out on the MOF crystals. The obtained lattice constants were a = 31.511 Å, b = 30.854 Å, c = 31.512 Å, which were in good agreement with the experimental values a = b = c = 31.006 Å within 2% error.

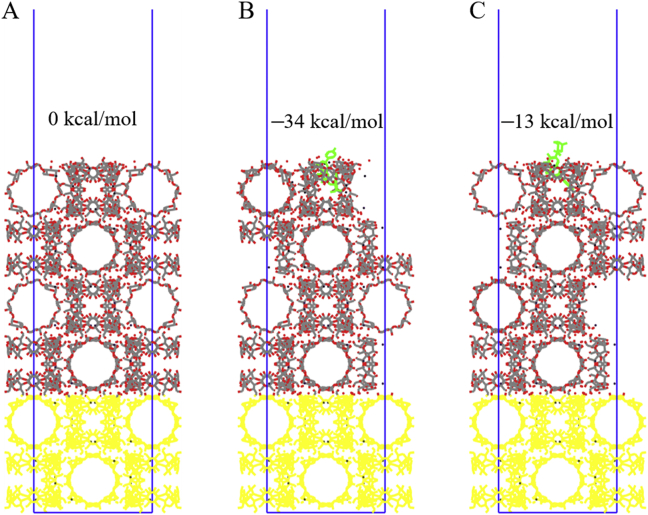

The results of surface relaxation showed that the surface structure with the double-cyclodextrin was the most stable one which was at least 1.5 × 10−4 kcal/mol lower than other surfaces. Based on this surface structure, the models of the glucose rings in SCU inside and outside the CD-MOF surface were constructed and simulated respectively (Fig. 5B and C). The results showed that the structure of the glucose ring inside the CD-MOF surface (Fig. 5B) was more stable (129 kcal/mol lower than the other case), which was also the maximum possibility in the realistic circumstances. The energy of the more stable surface was 34 kcal/mol lower than the blank surface, which lead to a lower possibility of agglomeration or great flowability between particles. In these two primary typical statuses, the difference of surface free energy of SCU@CD-MOF meant that the three-dimensional orientation of SCU inside CD-MOF would affect the surface properties of the powders, which possibly contributed to its laryngeal deposition.

Figure 5.

The relaxed (0 1 0) surface of CD-MOF with/without scutellarin (SCU). (A) Blank surface. (B) The glucose rings end of SCU inside the (0 1 0) surface. (C) The glucose rings end of SCU outside the (0 1 0) surface. The yellow atoms had been fixed and the green ones denoted SCU. The energy of blank surface was set to 0 kcal/mol as the reference energy.

3.4. Laryngeal deposition of SCU@CD-MOF

3.4.1. Evaluation of powder flowability

The angle of repose and the Carr's index are considered as the key indicators for the characterization of powder flowability51. The angle of repose is an indication of adhesion between particles and thus reflect the powder flowability. The smaller the angle of repose, the better the flowability. The Carr's index reveals the flowability based on its compressibility. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software. There was significant difference in the Carr's index between CD-MOF and SCU@CD-MOF, while there was no significant difference in angle of repose, bulk density and tapped density (Table 1). The results indicated the Carr's index was potentially an indicator for the characterization of laryngeal deposition in combination with aerodynamic performance.

Table 1.

Flowability parameters of CD-MOF and SCU@CD-MOF powders.

| Sample | Angle of repose (°) | Bulk density (g/mL) | Tapped density (g/mL) | Carr's index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-MOF | 48.10±2.50 | 0.21±0.01 | 0.43±0.01 | 50.10±0.02 |

| SCU@CD-MOF | 52.22±1.52 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.46±0.02 | 56.08±0.14a |

P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Significantly different compared to CD-MOF.

3.4.2. Determination of emptying rate and laryngeal deposition rate

The characteristics of inhalable particles cannot be judged solely by flowability, the aerodynamic performance shall be more reliable. In the formulation design, each capsule contained 10 mg SCU@CD-MOF (2.58 mg SCU per capsule). The results showed that the emptying rate of SCU@CD-MOF was 98.56 ± 0.30% (Supporting Information Table S1), which fit the requirements of greater than or equal to 90%. It was indicated that slight changes in flowability of SCU@CD-MOF had no effect on the emptying rate under certain circumstances.

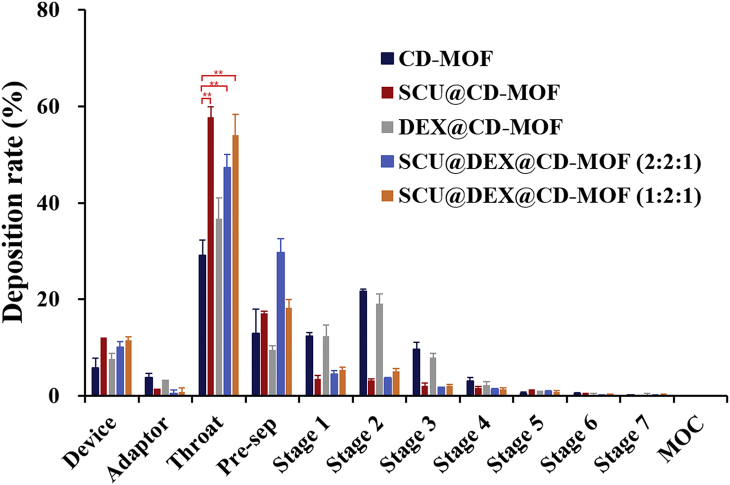

The test conditions for NGI experiment were P1 = 4.00 kPa and Qout = 63.80 L/min. The inhalation time was calculated to be 3.8 s. The laryngeal deposition rate of SCU@CD-MOF was 57.72 ± 2.19%, about twice as high as that of blank CD-MOF (P < 0.01, Table 2). It can be concluded that the encapsulation of SCU can greatly enhance the laryngeal deposition of CD-MOF particles.

Table 2.

The laryngeal deposition rates of CD-MOF, SCU@CD-MOF, DEX@CD-MOF and SCU@DEX@CD-MOF.

| Sample | Laryngeal deposition rate (%) |

|---|---|

| CD-MOF | 29.16 ± 3.11 |

| SCU@CD-MOF | 57.72 ± 2.19a |

| DEX@CD-MOF | 36.64 ± 4.29 |

| SCU@DEX@CD-MOF (feed molar ratio of 2:2:1) | 47.35 ± 2.68a |

| SCU@DEX@CD-MOF (feed molar ratio of 1:2:1) | 54.00 ± 4.34a |

P < 0.01. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Significantly different compared to CD-MOF.

The laryngeal deposition rate of DEX@CD-MOF was 36.64 ± 4.29% (not statistically significant compared to CD-MOF), while DEX and SCU were co-loaded into CD-MOF, the laryngeal and pre-separator deposition of SCU@DEX@CD-MOF were significantly increased with the reduction of stages 1–3 (Fig. 6). The statistical analysis of laryngeal deposition showed that there was significant difference between CD-MOF and SCU@DEX@CD-MOF (P < 0.01). This was similar to the results of SCU loaded into CD-MOF, which further proved that SCU had an improved effect on the aerodynamic behavior of CD-MOF particles and delivered DEX to the throat. On the other hand, it did not require a large amount of SCU to deposit more particles in the throat. The laryngeal deposition of SCU@DEX@CD-MOF (feed molar ratio of 2:2:1) was 47.35 ± 2.68%, lower than that of 1:2:1 feed molar ratio (54.00 ± 4.34%), which meant it was possible to reduce the content of SCU during the modification of CD-MOF particles and more conducive to the evaluation of biological safety in the later stage. Between 47.35% and 54.00%, there was no single concept/parameter that proved to be correlated. To the reason why laryngeal deposition rate of SCU@DEX@CD-MOF in different molar ratio was significantly different, one was because NGI results were related to multiple factors of ambient temperature, humidity, and particle distribution, the other one was because the molar ratio may changed the guest molecules’ configuration in the molecular voids in CD-MOF, which may changed the interaction between the particles and the artificial throat.

Figure 6.

The in vitro evaluation of CD-MOF, SCU@CD-MOF, DEX@CD-MOF and SCU@DEX@CD-MOF tested by NGI. Significantly different from CD-MOF, ∗∗P < 0.01. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The payload of DEX in DEX@CD-MOF was 1.43 ± 0.21% measured by HPLC-MS/MS. In the system of DEX and SCU co-loaded CD-MOF, DEX payloads with feed molar ratio of 2:2:1 and 1:2:1 were 1.33 ± 0.05% and 0.87 ± 0.04%, respectively, whilst the SCU payloads were 28.36 ± 0.30% and 17.80 ± 0.31%, respectively. It was worth to note that DEX was a highly active drug that can achieve local therapeutic effects in small quantity. On the other hand, it also showed that the loading efficiency of SCU in CD-MOF would not be reduced by co-loading of DEX.

From the characterizations of the powders, there was little difference between SCU@CD-MOF and the blank CD-MOF. Thus, the molecular configurations and SCU locations in CD-MOF were helpful to elucidate the mechanism for the interactions among particles, especially the potential interaction between the particles and the surface of the throat in the NGI device, which in turn changed the laryngeal particles distribution.

It is interesting to note that there was only Carr's index capable to distinguish the SCU@CD-MOF from the free CD-MOF among the conventional measurements, and the space configurations of SCU in CD-MOF had significantly different surface stabilities. Since the size was not enlarged in microscopic observations, it is hypothesized that the enhanced laryngeal depositions are not generated by the conventional particle size growth or particle agglomerations. The SCU loading may greatly change the interaction of SCU@CD-MOF and the surface of the throat of the NGI instrument. Yet there are technical and ethical challenges to directly observe the laryngeal depositions in vivo, the enhanced anchoring of SCU@CD-MOF suggests potential applications.

4. Conclusions

Given the natural inhalation relationship between laryngeal administration and dry powder inhalation, it is of great interest to transform conventional DPIs from pulmonary delivery to throat disease therapy. In this study, the DPIs carrier of CD-MOF with highly uniform inhalable particle size of 1–5 μm was modified using SCU to enhance the laryngeal anchoring of the CD-MOF particles as a novel carrier for laryngeal delivery. The laryngeal deposition rate was successfully evaluated using NGI. The flowability of the powder combined with the emptying rate (98.56 ± 0.30%) indicated that the powders were efficiently released from the capsule container. Efficient encapsulation of glycosides of SCU (payload of 27.21 ± 0.75%) significantly shifted the deposition characteristics of CD-MOF particles from the lungs to the larynx. At a flow rate of 65 L/min, the laryngeal deposition rate of SCU@CD-MOF was 57.72 ± 2.19%, while CD-MOF was 29.16 ± 3.11%. Furthermore, DEX was used as a model drug co-encapsulated with SCU in CD-MOF, which verified that SCU could target CD-MOF particles to the larynx. It was possible to achieve better therapeutic effects on laryngeal inflammation than other routes of administrations with less dosage and reduced systemic side effects of glucocorticoids. Molecular simulation combined with characterizations successfully supported the efficient SCU loading into the CD-MOF cavities, and enabled gaining insights on the configuration of SCU in CD-MOF and its contribution to the surface free energy of the SCU@CD-MOF, which possibly defined the enhanced laryngeal anchoring. The phenomenon that SCU successfully increased laryngeal deposition of CD-MOF suggests that it is of great significance to screen inactive glycosides with similar physicochemical properties to SCU as excipients for the administration of laryngeal therapeutic drugs. In a word, the inhalable CD-MOF carrier has great potential in laryngeal drug delivery as a new strategy for laryngeal administration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA12050307, China), the ANR AntiTBnano project (ANR-14-CE08-0017, France), the National Research Council of Science and Technology Major Projects for “Major New Drugs Innovation and Development” (2018ZX09721002–009, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.015.

Contributor Information

Senlin Shi, Email: pjstone@163.com.

Ruxandra Gref, Email: ruxandra.gref@universite-paris-saclay.fr.

Jiwen Zhang, Email: jwzhang@simm.ac.cn.

Author contributions

Jiwen Zhang, Senlin Shi and Ruxandra Gref designed the research. Kena Zhao, Caifen Wang and Priyanka Mittal carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Tao Guo performed the molecular simulation. All the co-authors wrote and revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Becker M., Burkhardt K., Dulguerov P., Allal A. Imaging of the larynx and hypopharynx. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66:460–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bykova V.P., Daikhes N.A., Platonova G.A., Bakhtin A.A., Kornienko K.A., Romanenko S.G., et al. Tumor-like amyloidosis of the upper respiratory tract. Arkh Patol. 2019;81:74–79. doi: 10.17116/patol20198105174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irem Turkmen H., Elif Karsligil M., Kocak I. Classification of laryngeal disorders based on shape and vascular defects of vocal folds. Comput Biol Med. 2015;62:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickhard A., Smith E., Rottscholl R., Brosch S., Reiter R. Disorders of the larynx and chronic inflammatory diseases. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol. 2012;91:758–766. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolachala V.L., Berg E.E., Shams S., Mukhatyar V., Sueblinvong V., Bellamkonda R.V., et al. The use of lipid microtubes as a novel slow-release delivery system for laryngeal injection. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1237–1243. doi: 10.1002/lary.21796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillai R., Petrak K., Blezinger P., Deshpande D., Florack V., Freimark B., et al. Ultrasonic nebulization of cationic lipid-based gene delivery systems for airway administration. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1743–1747. doi: 10.1023/a:1011964813817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolachala V.L., Henriquez O.A., Shams S., Golub J.S., Kim Y.T., Laroui H., et al. Slow-release nanoparticle-encapsulated delivery system for laryngeal injection. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:988–994. doi: 10.1002/lary.20856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yalcin E., Kara G., Celik E., Pinarli F.A., Saylam G., Sucularli C., et al. Preparation and characterization of novel albumin-sericin nanoparticles as siRNA delivery vehicle for laryngeal cancer treatment. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;49:659–670. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1599395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limb M., Connor A., Pickford M., Church A., Mamman R., Reader S., et al. Scintigraphy can be used to compare delivery of sore throat formulations. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:606–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNally D., Simpson M., Morris C., Shephard A., Goulder M. Rapid relief of acute sore throat with AMC/DCBA throat lozenges: randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:194–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleek R.L., Rege A.A., Denner L.A., Eskin S.G., Mikos A.G. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell growth in vitro by an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide released from poly (d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;35:525–530. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970615)35:4<525::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrer F. Sprays and lozenges for sore throats. S Afr Pharm Pract. 2011;78:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng T.T., Lin S.Q., Niu By, Wang X.Y., Huang Y., Zhang X.J., et al. Influence of physical properties of carrier on the performance of dry powder inhalers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang T.T., Chen Y.M., Ge Y.Y., Hu Y.Z., Li M., Jin Y.G. Inhalation treatment of primary lung cancer using liposomal curcumin dry powder inhalers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida H., Kuwana A., Shibata H., Izutsu K.I., Goda Y. Comparison of aerodynamic particle size distribution between a next generation impactor and a cascade Impactor at a range of flow rates. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2016;18:1–8. doi: 10.1208/s12249-016-0544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoe S., Young P.M., Traini D. Aerosol tribocharging and its relation to the deposition of Oxis™ Turbuhaler® in the electrical next generation impactor. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2011;100:5270–5280. doi: 10.1002/jps.22721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasr M.M., Ross D.L., Miller N.C. Effect of drug load and plate coating on the particle size distribution of a commercial albuterol metered dose inhaler (MDI) determined using the Andersen and Marple-Miller cascade impactors. Pharm Res. 1997;14:1437–1443. doi: 10.1023/a:1012180924063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdou E.M., Kandil S.M., Morsi A., Sleem M.W. In-vitro and in-vivo respiratory deposition of a developed metered dose inhaler formulation of an anti-migraine drug. Drug Deliv. 2019;26:689–699. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2019.1618419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L.D., Kong D.Q., Hu Q.F., Gao N., Pang S.X. Evaluation of high-performance curcumin nanocrystals for pulmonary drug delivery both in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2015;10:381–389. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-1085-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammed H., Roberts D.L., Copley M., Hammond M., Nichols S.C., Mitchell J.P. Effect of sampling volume on dry powder inhaler (DPI)-emitted aerosol aerodynamic particle size distributions (APSDs) measured by the Next-Generation Pharmaceutical Impactor (NGI) and the Andersen eight-stage cascade impactor (ACI) AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012;13:875–882. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9797-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins E.L., Basu S., Garcia G.J.M., Buckmire R.A., Shah R.N., Kimbell J.S. Ideal particle sizes for inhaled steroids targeting vocal granulomas: preliminary study using computational fluid dynamics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158:511–519. doi: 10.1177/0194599817742126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z.L., Grgic B., Finlay W.H. A dry powder inhaler with reduced mouth-throat deposition. J Aerosol Med. 2006;19:168–174. doi: 10.1089/jam.2006.19.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobo J.M., Schiavone H., Palakodaty S., York P., Clark A., Tzannis S.T. SCF-engineered powders for delivery of budesonide from passive DPI devices. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2005;94:2276–2288. doi: 10.1002/jps.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kugler S., Nagy A., Kerekes A., Veres M., Rigó I., Czitrovszky A. Determination of emitted particle characteristics and upper airway deposition of Symbicort® Turbuhaler® dry powder inhaler. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;54:101229–101236. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahimpour Y., Kouhsoltani M., Hamishehkar H. Alternative carriers in dry powder inhaler formulations. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Q., Liu G.J., Zhao Z.Y., Wei D.W., Pang J.F., Jiang Y.B. Design of gefitinib-loaded poly (l-lactic acid) microspheres via a supercritical anti-solvent process for dry powder inhalation. Int J Pharm. 2017;532:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Healy A.M., Amaro M.I., Paluch K.J., Tajber L. Dry powders for oral inhalation free of lactose carrier particles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;75:32–52. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiraki M. Physical characterization of TRK-720 hydrate, the very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) inhibitor, as a solid form for inhalation: preparation of the hydrate by solvent exchange among its solvates and mechanistical considerations. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2010;99:3986–4004. doi: 10.1002/jps.22246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matern J., Dorca Y., Luis Sánchez L., Fernández G. Revising complex supramolecular polymerization under kinetic and thermodynamic control. Supramolecular cyclodextrin-based hydrogels for controlled gene delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:16730–16740. doi: 10.1002/anie.201905724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He Y.Z., Hou X.F., Liu Y., Feng N.P. Recent progress in the synthesis, structural diversity and emerging applications of cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:5602–5619. doi: 10.1039/c9tb01548e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smaldone R.A., Forgan R.S., Furukawa H., Gassensmith J.J. Metal-organic frameworks from edible natural products. Angew Chem. 2010;49:8630–8634. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abuçafy M.P., Caetano B.L., Chiari-Andréo B.G., Fonseca-Santos B., do Santos A.M., Chorilli M., et al. Supramolecular cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks as efficient carrier for anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;127:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W., Guo T., Wang C.F., He Y.Z., Zhang X., Li G.Y., et al. MOF Capacitates cyclodextrin to mega-load mode for high-efficient delivery of valsartan. Pharm Res. 2019;36:117–131. doi: 10.1007/s11095-019-2650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J., Wu L., Guo T., Zhang G.Q., Wang C.F., et al. A “Ship-in-a-Bottle” strategy to create folic acid nanoclusters inside the nanocages of γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. Int J Pharm. 2019;556:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lv N.N., Guo T., Liu B., Wang C.F., Singh V., Xu X.N., et al. Improvement in thermal stability of sucralose by γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. Pharm Res. 2019;34:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-2059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kritskiy I., Volkova T., Surov A., Terekhova I. γ-Cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks as efficient microcontainers for encapsulation of leflunomide and acceleration of its transformation into teriflunomide. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;216:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao Q., Wang J.P., Huang Z., Qin Y., Xu X.M., Jin Z.Y. Novel approach with controlled nucleation and growth for green synthesis of size-controlled cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks based on short-chain starch nanoparticles. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:9785–9793. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartlieb K., Ferris D., Holcroft J., Kandela I., Stern C., Nassar M., et al. Encapsulation of Ibuprofen in CD-MOF and related bioavailability studies. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:1831–1839. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X., Guo T., Lachmanski L., Manoli F., Menendez-Miranda M., Manet I., et al. Cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks particles as efficient carriers for lansoprazole: study of morphology and chemical composition of individual particles. Int J Pharm. 2017;531:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moussa Z., Hmadeh M., Abiad M.G., Dib O.H., Patra D. Encapsulation of curcumin in cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks: dissociation of loaded CD-MOFs enhances stability of curcumin. Food Chem. 2016;212:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang G.Q., Meng F.Y., Guo Z., Guo T., Peng H., Xiao J., et al. Enhanced stability of vitamin A palmitate microencapsulated by γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. J Microencapsul. 2018;35:249–258. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2018.1462417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu X.X., Wang C.F., Wang L.B., Liu Z.X., Wu L., Zhang G.Q., et al. Nanoporous CD-MOF particles with uniform and inhalable size for pulmonary delivery of budesonide. Int J Pharm. 2019;564:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu B.T., Li H.Y., Xu X.N., Li X., Lv N.N., Vikramjeet S., et al. Optimized synthesis and crystalline stability of γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks for drug adsorption. Int J Pharm. 2016;514:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forgan R.S., Smaldone R.A., Gassensmith J.J., Furukawa H., Cordes D.B., Li Q., et al. Nanoporous carbohydrate metal–organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;134:406–417. doi: 10.1021/ja208224f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y., Yang Z.W., Ren Y.F., Mei X.G. Effects of formulation and operating variables on Zanamivir dry powder inhalation characteristics and aerosolization performance. Drug Deliv. 2014;21:480–486. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.883113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J., Hamishehkar H., Valizadeh H. Development of dry powder inhaler formulation loaded with alendronate solid lipid nanoparticles: solid-state characterization and aerosol dispersion performance. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2014;41:1–7. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2014.956111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rawal T., Kremer L., Halloum I., Butani S. Dry-powder inhaler formulation of rifampicin: an improved targeted delivery system for alveolar tuberculosis. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2017;30:388–398. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2017.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carr R.L. Evaluating flow properties of solids. Chem Eng. 1965;72:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torrisi B.M., Birchall J.C., Jones B.E., Díez F., Coulman S.A. The development of a sensitive methodology to characterise hard shell capsule puncture by dry powder inhaler pins. Int J Pharm. 2013;456:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steuer G., Prais D., Mussaffi H., Mei-Zahav M., Bar-On O., Levine H., et al. Inspiromatic-safety and efficacy study of a new generation dry powder inhaler in asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:1348–1355. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J.H., Zhai W.W., Yu J.Q., Wang J., Dai J.D. Preparation and quality evaluation of salvianolic acids and tanshinones dry powder inhalation. J Pharm Sci-US. 2018;107:2451–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.