Abstract

Background

Since coronavirus disease 2019 was first discovered, at the time of writing this article, the number of people infected globally has exceeded 1 million. Its high transmission rate has resulted in nosocomial infections in healthcare facilities all over the world. Nursing personnel account for nearly 50% of the global health workforce and are the primary provider of direct care in hospitals and long-term care facilities. Nurses stand on the front line against the spread of this pandemic, and proper protection procedures are vital.

Objectives

The present study aims to share the procedures and measures used by Taiwan nursing personnel to help reduce global transmission.

Review methods

Compared with other regions, where large-scale epidemics have overwhelmed the health systems, Taiwan has maintained the number of confirmed cases within a manageable scope. A review of various national and international policies and guidelines was carried out to present proper procedures and preventions for nursing personnel in healthcare settings.

Results

This study shows how Taiwan's health system rapidly identified suspected cases as well as the prevention policies and strategies, key protection points for nursing personnel in implementing high-risk nursing tasks, and lessons from a nursing perspective.

Conclusions

Various world media have affirmed the rapid response and effective epidemic prevention strategies of Taiwan's health system. Educating nurses on procedures for infection control, reporting cases, and implementing protective measures to prevent nosocomial infections are critical to prevent further outbreaks.

Keywords: Nursing, COVID-19, Novel coronavirus disease 2019, Pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, ncov, Taiwan

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has designated 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and Midwife. With approximately 21 million nurses and midwives worldwide, our profession makes up nearly 50% of the global health workforce.1 Nurses make up the largest component of the healthcare workforce and are the primary providers of direct patient care in hospitals and deliver most of the long-term care in institutions.2 Nurses are critical to any health system and are on the front lines of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.3 As of July 25, 2020, data from the WHO have confirmed more than 15.5 million cases in more than 200 countries and territories and more than 635 000 deaths.4 The COVID-19 outbreak has posed serious threats to countries and health systems as it spreads too rapidly for healthcare personnel to react. In particular, when healthcare workers on the front line have to treat numerous patients with insufficient protective gear, they are exposing themselves to danger. As of early March, 3300 healthcare workers in China have been infected.5 A report from an earlier time of the outbreak in Wuhan, China, showed that hospital-associated transmission was suspected as the presumed mechanism of infection for affected health professionals (40 [29%]) and hospitalised patients (17 [12.3%]).6 Data from Spain reported to the National Center for Epidemiology between February 28, 2020, and April 23, 2020, reveal that 20.4% of total cases (23 728/116 386) are healthcare providers.7 , 8 Italy reported a 10.7% rate of infection among healthcare providers (18 553/173 730), with at least 150 Italian physicians having lost their lives.8 , 9 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) counts more than 113 000 cases among healthcare providers and 576 deaths as of July 26, 2020, but acknowledges that this may be undercounted owing to limitations in data as only 20% of cases reported to the CDC included data if the patient was a healthcare provider.10 With the prevalence of community infection in some countries such as the United States of America, some of these cases in healthcare providers could have been acquired in the community; an earlier report from the CDC in April showed that 55% of healthcare providers think they contracted the virus while at work.11 The success of Taiwan in the current pandemic can be seen in the absence of nosocomial infection spread with a lack of healthcare workers being infected and small number of infections and mortality rates; as of July 27, 2020, there were 458 confirmed cases and seven deaths, which calculates to 0.03 deaths per 100 000 people, compared with 4 million confirmed cases in the United States of America, which is more than 146 000 deaths or 44.9 deaths per 100 000 people.12 As scientists are still developing antiviral drugs and vaccines for this new virus, infection control measures need to be prioritised to protect healthcare workers who are the most valuable resource for many nations.5

2. Prevention policies and strategies

Similar to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses, COVID-19 exhibits typical coronavirus traits. It is spread mostly among people through droplets or by direct contact, although fomite and airborne transmission is possible.13 The average incubation period is 5.2 d.14 Each patient with COVID-19 is estimated to be able to infect 2.2 people,15 and the number of infected people doubles every 6.4 d on average.16 People who contract COVID-19 may exhibit mild, severe, or critical symptoms. Severe and critical symptoms include severe pneumonia, respiratory distress, sepsis, and, eventually, death.1 As per an analysis of 72 314 cases in China, 81% of patients exhibited mild symptoms, whereas 14% had severe symptoms (i.e., difficulty in breathing and reduced blood oxygen saturation). Another 5% had critical symptoms (i.e., respiratory failure, septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction, or organ failure).17

During the SARS epidemic in Taiwan in 2003, a local hospital in Taipei had 17 members of the medical staff from different departments who were infected with SARS, and some had no direct contact with SARS cases. Within 3 months, 120 healthcare workers had been infected after exposure to the medical ward, where the index patient had stayed. During the SARS outbreak in Taiwan, there were 668 cases and 181 deaths.18 The Taiwanese CDC analysed the spread to come up with the traffic control bundle.19 The traffic control bundle takes its name from the “traffic light system”, with separate zones of risk delineated by wooden or acrylic boards, red meaning the contaminated or hot zone, yellow meaning the transition zone, and green meaning the clean zone with checkpoints equipped with hand sanitation stations between zones.20 The traffic control bundle's pilot testing was very successful with significantly lower rates of infection in healthcare workers than those in the control hospital (P = .03) and was then implemented in all Taiwan hospitals, leading to a significant decrease in infection rates after 2 weeks.19 , 21

2.1. Hospital screening and triage

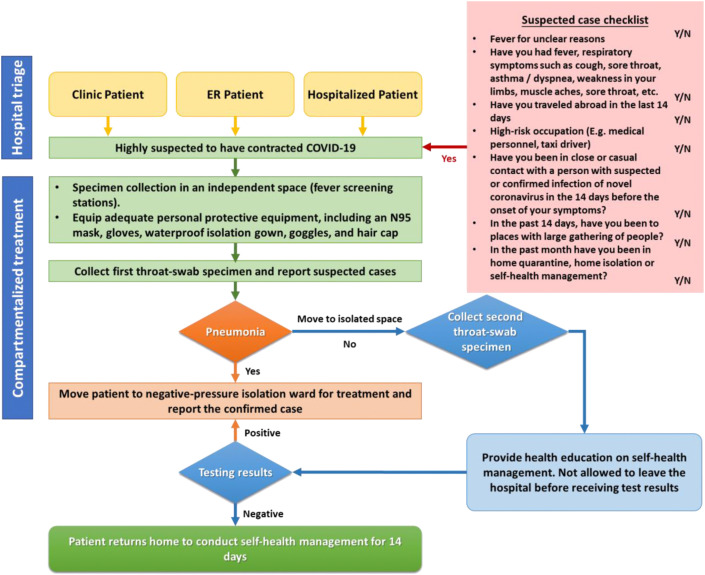

Another aspect of the traffic bundle control strategy is setting up triage or screening stations and implementing diversion of patients in outdoor locations before the entrance to the hospital. A critical measure for controlling viral infections such as COVID-19 is the prevention of its spread among people.22 Therefore, identifying patients with suspected infection and isolating them early is crucial for preventing nosocomial infection. As per the WHO, to be identified as having a suspected COVID-19 infection, a person might exhibit various clinical symptoms (including fever, cough, fatigue, anorexia, myalgias, nonspecific symptoms) and lack other causes that explain his/her clinical conditions.1 In addition, patients' travel histories to infected areas (Travel), involvement in high-risk industries (Occupation), close or casual contacts with people in the past 14 d who had suspected or confirmed infections (Contacts), and exposure to known infectious cases in gatherings places such in the neighbourhood or large events (Clusters) are used as screening questions in the Travel, Occupation, Contacts, Cluster survey to assess for risk of COVID-19.23 The suspected case standard definitions of the WHO are applied in Taiwan. Nurses conduct screening and inquiry for patients in clinics and emergency departments and for those who are newly hospitalised to effectively identify suspected cases and conduct triage management (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 suspected case screening and hospital compartmentalisation and triage procedure. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. (Guidelines on infection control measures for medical institutions in response to COVID 19). [Internet]. Updated 2020 June [cited 2020 July 18]; [about 17-18 p.]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/File/Get/F8NzTBwSxgz4Rjcy-6Y50w. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

After evaluation by using the COVID-19 screening procedure, patients with suspected infections or at high risk are transferred to quarantine areas with sufficient ventilation for evaluation, specimen collection, and inquiry. Triage for patients with fever is conducted where entrances and walkways are segregated for patients and medical personnel. Additional handwashing facilities were installed to protect healthcare personnel.19 Proper and correct infection control and adequate isolation–protection measures need to be used during specimen collection (see Fig. 1). High-risk patients whose testing results are pending are moved to quarantine wards, and patients with confirmed COVID-19 are moved to negative-pressure rooms in isolation wards for treatment (Fig. 1).23

2.2. Inpatient management strategies

-

I.

Wards specifically for epidemic prevention should be established to centralise suspected patients as per the interim guideline from the WHO.24 In principle, one patient is placed in one room.1 The traffic flows of ward staff and patients should be separated.25

-

II.

Workers should be assigned to care for patients in specific zones of the hospital and should not work across departments. Their resting areas should also be separated. This system prevents all workers from having contact with the patient and being quarantined when a unit has a confirmed case, which would hinder medical operation capacity.26

-

III.

Patients are triaged and sent to different zones based on the risk severity of their conditions, such as whether they have contact history or pneumonia, thereby enhancing adequate patient placement.23

2.3. Worker management strategies

Healthcare personnel are categorised by their scope of care areas into negative-pressure isolation wards, isolation areas and fever-screening stations, clinics, respiratory departments, infectious disease departments, intensive care units (ICUs), and general ward areas. The allocation of nursing staff is fixed. The nursing workforce of the negative-pressure isolation ward, isolation area, and fever-screening stations is composed of staff from the emergency department and ICU. They are separated into groups and care for their designated patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in their areas. Healthcare personnel should not work interchangeably across areas to avoid cross infection.26

When healthcare personnel are infected, their ward must be closed and sanitised. Healthcare personnel who were exposed to or have contact with patients with COVID-19 must be evaluated and quarantined, and this would substantially reduce the healthcare workforce. Foreseeing this crisis, the Taiwanese government banned healthcare personnel from travelling abroad to maintain healthcare capacity when the number of COVID-19 cases began to increase globally.23

2.4. Protection of policies of nursing personnel

As per the WHO, when nursing staff members care for patients with a high risk of contracting COVID-19, they should act to prevent contact with pathogens.1 Public health and infection control interventions are urgently required to hinder the spread of COVID-19 among people. In hospitals, secondary infection among healthcare staff members must be prevented.27 After patients are identified at high risk of COVID-19, they should be placed in a well-ventilated single-person room, provided with surgical masks, and reminded to cover their mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing. Hand hygiene so far is the most effective evidence-based prevention against viral infections.1 , 22

2.4.1. Personal protective equipment

During the SARS outbreak in 2003, most hospitals in Taiwan did not thoroughly implement principles for controlling nosocomial infections. Many medical workers were infected because they lacked proper understanding of infection control and procedures in donning and doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE).28 Hospitals in Taiwan have incorporated lessons on proper infection control procedures in nurses' orientations. In 2005, the Taiwan government established the National Health Command Center (NHCC) as a disease outbreak management centre that operates as the command point for communication among central, regional, and local authorities. The centres of operation under the NHCC include the Central Epidemic Command Center, the Biological Pathogen Disaster Command Center, the Counter-Bioterrorism Command Center, and the Central Medical Emergency Operations Center.29

In addition, the Taiwan Disease Control Agency has amended the law to establish a three-tier inventory system for PPE (including surgical masks, N95 masks, and full-body protective clothing) for central, regional, and local governments and medical institutions. It stipulates the safety reserves of each medical unit to ensure that the supply of PPE required for public health, epidemic prevention, and medical care in the early stage of the epidemic can be provided. The calculation method of the safety reserve refers to the requirements of the WHO-recommended isolation measures, PPE replacement rate, supply capacity, delivery time, usual usage rates, and so on. The NHCC recommended implementation of border quarantine and support for local needs in response to community epidemic prevention and provides support to medical institutions to estimate the materials needed for prevention and mobilisation in the early stages (within 30 d) of the epidemic situation. The disease control materials are stored by the Taiwanese CDC, and the reserves of other medical-related materials are delegated among the ministries of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Ministry of National Defense, the Agricultural Committee, and the Ministry of the Interior. The epidemic command centre coordinates the distribution and dispatch of materials in a timely manner.30

The Centers for Disease Control of the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan mandates that when healthcare staff members care for patients with a high risk of contracting COVID-19, they must use PPE, including goggles, visors, an N95 respirator mask, surgical masks, gloves, gowns, waterproof gowns, shoe covers, and a hair cap. A fit check should be conducted every time nurses have to wear an N95 respirator mask. Suitable masks, head straps, or helmets should be picked to ensure that the skin is protected and that there are no leaks while wearing the mask. The Taiwanese Centers for Disease Control has also explained in detail the level of protection required when implementing specific treatments or collecting specimens, thereby protecting healthcare staff and preventing COVID-19 from spreading in healthcare institutions (Table 1 ).23 As per various reviews, proper PPE can reduce contamination and infection from contagion.31 , 32

Table 1.

Personal protective equipment for treating patients with COVID-19 (Resource from Taiwan hospital-Taipei Veterans General Hospital).

| Protective equipment | Fever-screening station | Specimen collection | Caring for patients with reported cases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirmed cases or 2. Cases with pending test results |

Cases with a negative first-test result | |||||

| Mask | Outer layer | General surgical masks | V | V | ||

| Changing frequency | Each time | V | V | |||

| Inner layer | N95a | Ve | V | V | V | |

| Changing frequency | After a cumulative 8 h or after having been removed 5 times | V (Change when doubtful or when wet) |

V (Change when doubtful or when wet) |

V (Change when doubtful or when wet) |

V | |

| Gown | Outer layer | Waterproof gownb | V | V | V | |

| Changing frequency | After caring for each patient | V | V | V | ||

| Other | V (Change when removing) |

|||||

| Inner layer | Waterproof gownb | Waterproof aprond (contact with blood or body fluids) | Full-body type | Full-body type | Waterproof aprond (contact with blood or body fluids) | |

| Changing frequency | After caring for each patient | |||||

| Other | V (Change when removing) |

V

|

V | |||

| Gloves | Single layer | V (use dry hand wash between patients) |

V | V | ||

| Double layer | V (Remove the outer glove. Use dry hand wash between patients.) |

|||||

| Eye-protection equipmentc | Goggles/Visor | Goggles/face mask | Visor | Goggles/visor | Goggles/visor | |

| Hair cap | Yes | V | V | V | V | |

| Shoe cover | Single layer | V | ||||

| Double layer | V | |||||

| Treatment location | Negative-pressure isolation ward | V |

|

|||

| Single ward (Door closed) | V | V | ||||

§ Treatments involving droplets, including bronchoscopy, airway intubation, processes involving coughing to collect mucus or spray inhalation, respiratory secretions suction, and treatments using high-speed equipment to conduct anatomical pathology or lung surgery.

N95mask: Accumulated time of use should not exceed 8 hours, or the mask should be replaced after being removed 5 times. A fit check should be conducted each time before use. In locations where PPE is required, a fit check graph should be provided for reference.

Waterproof gown: Full-body or waterproof apron with a splash-proof gown on top (the outer-layer gown must cover the internal waterproof apron).

Goggles: medical treatment requiring general contact with the patient, such as evaluating body temperature, blood pressure, and performing X-rays. Visor: medical treatment involving a risk of contact with blood, body fluids, or excretions or medical treatments that may generate droplets§.

Medical treatment involving risk of contact with blood, body fluids, or excretions or treatments that may generate droplets.

V Checkmark indicates the equipment needs to be applied.

To ensure understanding and awareness of protective measures of infection control, hospitals can designate a nurse who has advanced understanding of the use of PPE to train fellow nurses in the donning and doffing of PPE with the aid of the checklists, which are provided in Table 2 .33

Table 2.

Personal protective equipment donning and doffing checklist (Resource from Taiwan hospital-Taipei Medical University-affiliated hospital).

|

Donning (Putting on) Personal Protective Equipment:Evaluation results: V: pass; X: fail; NA: not applicable(personnel can pass only after checking each item thoroughly) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Check | Steps | Description |

| Sanitise hands |

|

|

| Put on the first (inner) layer of gloves |

|

|

| Put on waterproof boot-length shoe covers |

|

|

| Put on the waterproof one-piece protective suit (without cap) |

|

|

| (Fit check) Put on an N95 mask and hair cap; conduct a fit check |

|

|

| Put on disposable waterproof one-piece protective suit and cap |

|

|

| Put on the second (outer) layer of long gloves |

|

|

| Put on disposable waterproof isolation cover |

|

|

| Put on protective visor |

|

|

| Inspect equipment for completion |

|

|

| Sanitise hands |

|

|

|

To enter an isolation ward, personnel must complete the registration form with their name, title, and time of entry. | ||

|

Doffing (Removal) of Personal Protective Equipment. Evaluation results: V: pass; X: fail; NA: not applicable (personnel can pass only after checking each item thoroughly) | ||

|

Check |

Steps |

Description |

|

||

| Inspect protective equipment →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove waterproof isolation clothing →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove outer-layer gloves →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove protective visor →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

|

The aforementioned steps above should be completed in the contaminated zone (behind the door to the inner room of the isolation ward.) | ||

| Remove one-piece protective suit →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove hair cap →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove waterproof boot-length shoe cover →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove inner-layer gloves →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

|

The aforementioned steps should be completed in the buffer area (in the front room of the isolation ward). | ||

| Put on new gloves |

||

| Remove N95 mask →alcohol-based hand rub |

|

|

| Remove gloves → Sanitize hands (hand washing) |

|

|

| When leaving the isolation ward, personnel must complete the registration form with their time of exit. | ||

The route of transmission of COVID-19 is mostly through respiratory droplets and close contacts. However, there is the possibility of airborne transmission when exposed to high concentration of aerosol in a relatively closed environment or using procedures generating aerosols such as bronchoscopy.13 The healthcare institution should implement standard, contact, and airborne precautions when taking care of patients with COVID-19.34 In addition, RNA of COVID-19 was detected in feces and urine; thus, attention should be paid to fecal and urine sewage to avoid environmental pollution.35

2.5. Environmental disinfection and waste management

Single-use medical devices should be used whenever possible and discarded in the ward's medical waste bin. Avoid using reusable medical devices. If they must be used, disinfect them after use following manufacturers' instructions. Eating utensils can be cleaned in accordance with normal procedures. Surfaces that the patient touches often (such as the cabinet at the head of the bed, the desk next to the bed, and bed rails) should be disinfected with 70% isopropyl alcohol. The washroom and the toilet surface should be disinfected using a combined detergent–chlorine-releasing solution at a concentration of 1000 ppm.36 Avoid shaking used comforters, clothes, and woven items, and send them for disinfection and laundering as soon as possible. Used bed sheets, comforters, and clothes should be bagged in accordance with procedures for handling contaminated woven items, and they should be regarded as having a high contamination risk and require laundering.26 All wastes generated in the isolation ward or area should be discarded in appropriate containers to ensure that they will not overflow or leak. Relevant governmental regulations on infectious waste management need to be followed.

Conducting high-risk nursing tasks

Although COVID-19 mostly spreads through contact and droplet transmissions, airborne and fomite transmission is possible. In medical institutions, airborne transmission is possible when aerosols are generated during aerosol-generating procedures.1 Aerosol-generating procedures are those that produce droplets that are small enough to be widely dispersed. They pose a higher infection risk for health professionals and should only be carried out in a hospital setting if COVID-19 is suspected. These procedures require airborne precaution and include tracheal intubation, noninvasive ventilation, tracheostomy, manual ventilation, bronchoscopy, sputum suction, high-flow nasal oxygen therapy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and nebulised treatment. Other high-risk technical nursing procedures include vein or artery puncture and nasopharyngeal specimen collection.37 Critical principles of implementing these techniques include performing treatments in well-ventilated rooms or negative-pressure wards, limiting the number of people in a room, reserving techniques related to the trachea to professionals, and considering early intubation to ensure sufficient preparation.38

3.1. Diagnostic respiratory specimen collection

-

I.

Collecting nasopharyngeal specimens by using a swab is likely to induce coughing or sneezing and should be carried out in a spacious, negative-pressure single room or well-ventilated environment outdoors. Limit the number of personnel around. Complete the procedure by involving just one person. Wipe and disinfect the surfaces in the operation area as soon as the area becomes contaminated (with 2000 mg/L of chlorine disinfectants).39

-

II.

Nurses collecting specimens for COVID-19 testing from patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (i.e., a person under investigation) should adhere to the standard, contact, and airborne precautions, including the use of eye protection.1

-

III.

These procedures should take place in an airborne infection negative-pressure isolation room. Ideally, the patient should not be placed in any room where room exhaust is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air filtration.14

3.2. Sputum suction technique

Endotracheal tube suctioning should only be carried out as needed. To prevent droplet transmission of coronavirus, closed suctioning circuits are used. The endotracheal suction catheter is left connected to the suction apparatus to minimise break in the system. When not in use, the suction apparatus needs to be turned off. Patients should be hyperoxygenated by setting the ventilator oxygen to 100% before suctioning instead of disconnecting the patient from the ventilator and hand-bagging the patient.40

3.3. Oxygen therapy

For patients with highly contagious respiratory tract diseases (such as COVID-19) requiring isolation, oxygen therapy measures are as follows:

3.3.1. Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation may be reserved for the occasional patient with mild acute respiratory distress syndrome who is hemodynamically stable, is easily oxygenated, does not need immediate intubation, and has no contraindications to its use.

Noninvasive ventilation devices, such as those for bilevel positive airway pressure, continuous positive airway pressure, intermittent positive pressure breathing, and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, that increase the number of germs or viruses spreading into the environment and, therefore, the infection risk should be avoided. Oxygen therapies that generate mist or vapour, such as multipurpose nebuliser and aerosol inhalation therapies, and devices that increase the number of pathogens in the environment and infection risk should be prohibited.41 However, in the case wherein noninvasive ventilation (NIV) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is not contraindicated, Cabrini et al42 suggest that a helmet device could be used to avoid aerosolisation as the helmet is connected to the ventilator without air dispersion through a spring valve. The number of available ICU beds during the COVID-19 outbreak is mostly likely less than the total number of patients with COVID-19 requiring NIV or CPAP. Thus, to prevent ICU admission, the use of helmets in general wards could be implemented. However, as the number of ICU beds may not be able to adequately supply the number of patients with COVID-19 requiring NIV or CPAP, a helmet bundle could be considered in the isolation wards of COVID-19.43

Regarding the nasal cannula for general oxygen therapy or connection tubes for tracheostomy or tracheal intubation, use disposable devices for single-person use. The ventilator must have high-efficiency particulate air filters. High-flow nasal oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation are not recommended for regular use in patients with COVID-19. When providing oxygen therapy, if the oxygen flow is lower than 4 L/min and if the patients are not receiving tracheostomy or tracheal intubation, a humidifier bottle is not required. However, exceptions are made for patients who require long-term oxygen therapy or had an adverse reaction to tracheostomy or tracheal intubation.26

For most patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, defined as the acute onset of respiratory failure; bilateral infiltrates on the chest radiograph; hypoxaemia from the Berlin definition with either mild hypoxia (PaO2/FIO2: 200–300 mm Hg), moderate hypoxia (PaO2/FIO2: 100–200 mmHg), and severe hypoxia (PaO2/FIO2: <100 mm Hg); and no evidence of hydrostatic oedema, we suggest proceeding directly to invasive mechanical ventilation.38 , 44

3.3.2. Invasive mechanical ventilation

3.3.2.1. Principles of invasive mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients

Use a low tidal volume (4–8 ml/kg of predicted body weight) and lower inspiratory pressure (plateau pressure <30 cmH2O).1 Prone ventilation, as opposed to the more commonly used supine position, is a strategy to improve oxygenation in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. The period recommended for prone ventilation is more than 12 h each time.45 For patients using invasive mechanical breathing aids, a closed suctioning system is recommended. Gastric residual volume and gastrointestinal function should be routinely evaluated for the prevention of regurgitation and aspiration. Appropriate enteral nutrition is recommended to be given as earlier as possible. In addition, if no contraindication, a 30° semirecumbent position is supported.46 , 47

Furthermore, fluid management is also vital. Excessive fluid burden worsens hypoxaemia in patients with COVID-19. Thus, to reduce pulmonary exudation and improve oxygenation, the amount of fluid should be strictly controlled while ensuring the patient's perfusion.48 It is also very important to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. The ventilator-associated pneumonia bundle should be strictly implemented.49 The heat and moisture exchanger is recommended instead of heated humidifiers.50 Single-use ventilator circuits are recommended, and routine replacement is not advised.26

3.4. Tracheostomy and tracheal intubation care

When cleaning the tracheotomy wound, do not remove the closed suctioning system to prevent the patient's sputum from leaving the tube. When operating and changing the closed suctioning system, be gentle to avoid stimulation that would cause the patient to cough.

Endotracheal intubation should be performed by a trained and experienced provider using airborne precautions.40 When conducting tracheal intubation, assign the minimum number of nurses who can smoothly complete the operation. Before intubation, using a disposable balloon for aeration is strongly advised. If using a reusable balloon, contain it after use in a double-layered yellow garbage bag marked “COVID-19 contaminant”, and deliver it in a closed container to the cleaning and disinfecting supply centre for disinfection.51

3.5. Artery and vein puncture

Providing medicine through peripheral venous indwelling cannulae is advised to reduce puncture frequency, thus saving resources and reducing risks for the operator.52 When applicable, needleless connectors can be used. Indwelling cannulae do not require routine replacement but should be replaced with clinical indication.53 When indwelling cannulae are used, reinforce observation of the area near the puncture point. If adverse reactions such as phlebitis occur, immediately replace the indwelling cannulae. When puncturing an artery or vein, follow operation regulations to prevent sharp instrument wounds.54

4. Psychological empowerment and education

Recent studies conducted in hospitals in East Asia on healthcare workers treating patients with COVID-19 showed that 50% of frontline healthcare personnel showed symptoms of depression, 44% had anxiety, 34% had insomnia, 13.3% reported trauma, and 80% showed extreme levels of stress.55 , 56 Therefore, it is essential to conduct psychological empowerment and psychoeducational activities to reduce fears and reinforce beliefs. Healthcare systems and government can provide education and empowerment for people who have been affected by COVID-19 to assist their psychological and social reintegration. Establishing and implementing just-in-time staff education online can provide updates on the newest findings and development of pandemic and strengthen nurses' ability to care for patients with COVID-19.57 Transparency in communicating any change in services or policies to staff, residents, families, and the healthcare coalition is also needed.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread widely over the last few months. This disease has attracted global attention and required prompt action in all aspects of the society either in or out of the hospital. The response speed of most governments has been much slower than the rate at which the virus has spread. Staying alert and taking initiatives in pre-emptive preparation are keys to deal with a new contagious disease.

Taiwan's medical system has acquired awareness and demonstrated professionalism in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic because of its experience with SARS in 2003. At that time, nosocomial infection occurred because most hospitals lacked the following: consolidated protocols for preventing nosocomial infections, protective equipment, and the disease prevention strategies of the traffic control bundle.58 The subsequent closing of hospitals and deaths of medical staff substantially affected Taiwanese people and the medical system. We have learned some hard lessons. Since then, in new nurse orientation training and continuing education sessions, the use of PPE and infection control are mandatory topics. When facing COVID-19, hospitals rapidly and decisively enacted the compartmentalisation and triage policy and various critical infection control procedures. Healthcare workforce capacity and supplies were inventoried to provide frontline personnel with sufficient protective supplies and effectively control the spread of the virus to increase time for sufficient preparation.

Fighting a disease resembles fighting a war. Awareness among frontline healthcare personnel in standard operating procedures for infection control and implementing protective measures to prevent nosocomial infections are critical to prevent disease outbreaks. Healthcare systems must safeguard public health. Nurses, along with other healthcare personnel, are the frontline defenders. component of the healthcare workforce also defence. As nurses make up the largest component of the healthcare workforce in number, they are also integral to surmounting a good defense defence against the coronaviruses. When facing the possibility of large-scale community infection, healthcare institutions must protect healthcare personnel and cooperate with the government and rapidly change to form a collaborative defence system to battle this disease. All levels of the health system should summarise the requirements for epidemic prevention and infection control work and further implement and provide the documents as a consolidated guideline.59

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shu-Yen Liu: Resources, Roles/Writing - original draft, Visualisation. Xiao Linda Kang: Resources, Validation, Roles/Writing - original draft. Chia-Hui Wang: Resources, Validation, Roles/Writing - original draft. Hsin Chu: Validation, Writing - review & editing. Hsiu-Ju Jen: Resources, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Hui-Ju Lai: Resources, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Shu-Tai H. Shen: Resources, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Doresses Liu: Resources, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Kuei-Ru Chou: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Validation, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the healthcare personnel working tirelessly through the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- 1.WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected

- 2.Nursing AAoCo AACN fact sheet–nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Fact-Sheets/Nursing-Fact-Sheet files/2128/Nursing-Fact-Sheet.html 11:26:25.

- 3.Choi K.R., Skrine Jeffers K., Cynthia Logsdon M. Nursing and the novel coronavirus: risks and responsibilities in a global outbreak. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76:1486–1487. doi: 10.1111/jan.14369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.The L COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iscii Informes COVID-19. https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Paginas/InformesCOVID-19.aspx

- 8.Harrison D., Muradali K., El Sahly H., Bozkurt B., Jneid H. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on health-care workers. Hosp Pract. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2020.1771010. (1995)0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FnomceO Elenco dei Medici caduti nel corso dell’epidemia di Covid-19. https://portale.fnomceo.it/elenco-dei-medici-caduti-nel-corso-dellepidemia-di-covid-19/

- 10.CDC U Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

- 11.Team CC-R Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477–481. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins J. Mortality analyses. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- 13.WHO Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions

- 14.CDC Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

- 15.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395:689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen K.T., Twu S.J., Chang H.L., Wu Y.C., Chen C.T., Lin T.H. SARS in Taiwan: an overview and lessons learned. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yen M.Y., Lin Y.E., Lee C.H., Ho M.S., Huang F.Y., Chang S.C. Taiwan's traffic control bundle and the elimination of nosocomial severe acute respiratory syndrome among healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz J., King C.-C., Yen M.-Y. Protecting healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: lessons from Taiwan's severe acute respiratory syndrome response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen M.Y., Schwartz J., Wu J.S., Hsueh P.R. Controlling Middle East respiratory syndrome: lessons learned from severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1761–1762. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jefferson T., Del Mar C.B., Dooley L., Ferroni E., Al-Ansary L.A., Bawazeer G.A. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taiwan C. 醫療機構因應COVID 19感染管制措施指引 (Guidelines on infection control measures for medical institutions in response to COVID 19) https://www.cdc.gov.tw/File/Get/F8NzTBwSxgz4Rjcy-6Y50w

- 24.WHO Operational considerations for case management of COVID-19 in health facility and community. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/10665-331492

- 25.Millar R.C. Nursing a patient with Covid-19 infection. https://journal-ebnp.com/2020/02/25/nursing-a-patient-with-covid-19-infection/

- 26.Liang T. Handbook of COVID-19 prevention and treatment. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339998871_Handbook_of_COVID-19_Prevention_and_Treatment/citations

- 27.Song F., Shi N., Shan F., Zhang Z., Shen J., Lu H. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y.C., Chen P.J., Chang S.C., Kao C.L., Wang S.H., Wang L.H. Infection control and SARS transmission among healthcare workers, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:895–898. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C.J., Ng C.Y., Brook R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new Technology, and proactive testing. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welfare MoHa Provide a steady supply of disease prevention supplies to reassure society and the people. https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/en/cp-4785-53788-206.html files/2536/cp-4785-53788-206.html

- 31.Verbeek J.H., Rajamaki B., Ijaz S., Sauni R., Toomey E., Blackwood B. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu D.K., Akl E.A., Duda S., Solo K., Yaacoub S., Schunemann H.J. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansson M., Liao X., Rello J. Strengthening ICU health security for a coronavirus epidemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;57:102812. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. COVID-19 overview and infection prevention and control priorities in non-US healthcare settings.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/overview/index.html files/2580/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2004973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scotland DoH Rapid Review of the literature: assessing the infection prevention and control measures for the prevention and management of COVID-19 in healthcare settings. https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2985/documents/1_2020-3-19-Rapid-Review-IPC-for-COVID-19-V1.0.pdf

- 37.O'Neil C.A., Li J., Leavey A., Wang Y., Hink M., Wallace M. Characterization of aerosols generated during patient care activities. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1335–1341. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murthy S., Gomersall C.D., Fowler R.A. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson J. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018. (Infection control in clinical practice updated edition E-book). [Google Scholar]

- 40.NHS . 2020. Clinical guide for the management of critical care for adults with COVID-19 during the coronavirus pandemic.https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0216_Specialty-guide_AdultCritiCare-and-coronavirus_V2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41.NHS Guidance for the role and use of non-invasive respiratory support in adult patients with coronavirus (confirmed or suspected) https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/CLEARED_Specialty-guide_-NIV-respiratory-support-and-coronavirus-v2-26-March-003.pdf

- 42.Cabrini L., Landoni G., Zangrillo A. Minimise nosocomial spread of 2019-nCoV when treating acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2020;395:685. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucchini A., Giani M., Isgro S., Rona R., Foti G. The "helmet bundle" in COVID-19 patients undergoing non invasive ventilation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;58:102859. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Force A.D.T., Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., Ferguson N.D., Caldwell E. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munshi L., Del Sorbo L., Adhikari N.K.J., Hodgson C.L., Wunsch H., Meade M.O. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S280–S288. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-343OT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic S [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia] Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi. 2020;17 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L., Li X., Yang Z., Tang X., Yuan Q., Deng L. Semi-recumbent position versus supine position for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults requiring mechanical ventilation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009946.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beitler J.R., Schoenfeld D.A., Thompson B.T. Preventing ARDS: progress, promise, and pitfalls. Chest. 2014;146:1102–1113. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kao C.C., Chiang H.T., Chen C.Y., Hung C.T., Chen Y.C., Su L.H. National bundle care program implementation to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gillies D., Todd D.A., Foster J.P., Batuwitage B.T. Heat and moisture exchangers versus heated humidifiers for mechanically ventilated adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004711.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehta Y., Gupta A., Todi S., Myatra S., Samaddar D.P., Patil V. Guidelines for prevention of hospital acquired infections. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:149–163. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.128705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pittiruti M., Pinelli F., GAWGfVAi C.O.V.I.D. Recommendations for the use of vascular access in the COVID-19 patients: an Italian perspective. Crit Care. 2020;24:269. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02997-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster J., Osborne S., Rickard C.M., Marsh N. Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007798.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Grady N.P., Alexander M., Burns L.A., Dellinger E.P., Garland J., Heard S.O. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e162–e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen R., Sun C., Chen J.J., Jen H.J., Kang X.L., Kao C.C. A large-scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/inm.12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang L., Lin G., Tang L., Yu L., Zhou Z. Special attention to nurses' protection during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care. 2020;24:120. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng V.C., Chan J.F., To K.K., Yuen K.Y. Clinical management and infection control of SARS: lessons learned. Antivir Res. 2013;100:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bao Y., Sun Y., Meng S., Shi J., Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395:e37–e38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]