Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is not a unique disease, encompassing multiple entities with marked histopathological, transcriptomic and genomic heterogeneity. Despite several efforts, transcriptomic and genomic classifications have remained merely theoretic and most of the patients are being treated with chemotherapy. Driver alterations in potentially targetable genes, including PIK3CA and AKT, have been identified across TNBC subtypes, prompting the implementation of biomarker-driven therapeutic approaches. However, biomarker-based treatments as well as immune checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy have provided contrasting and limited results so far. Accordingly, a better characterization of the genomic and immune contexture underpinning TNBC, as well as the translation of the lessons learnt in the metastatic disease to the early setting would improve patients’ outcomes. The application of multi-omics technologies, biocomputational algorithms, assays for minimal residual disease monitoring and novel clinical trial designs are strongly warranted to pave the way toward personalized anticancer treatment for patients with TNBC.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Breast cancer

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) refers to a subgroup of breast cancer (BC) defined by the lack of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Accounting for 15–20% of all BCs, TNBC is more prevalent in younger women, African and Hispanic descents and carriers of deleterious germline mutations in BC susceptibility genes1.

Pivotal microarray profiling studies categorized BC into five intrinsic subtypes2. Although the TNBC subgroup is considered a single entity based on immunohistochemistry (IHC), molecular profiling has revealed an unexpectedly level of heterogeneity. 50–75% of TNBCs have basal-like phenotype (BLBC), being characterized by the expression of genes of normal basal and myoepithelial cells2,3. Similarly, ∼80% of BLBCs are ER-negative and HER2-negative4. Even if the terms “TNBC” and “BLBC” are often used interchangeably, not all BLBCs determined by gene expression profiling (GEP) lack ER, PgR and HER2 and, conversely, not all TNBCs show a basal-like phenotype5–8. Moreover, another intrinsic subtype, namely claudin-low, was identified and characterized by a brisk stromal infiltration and expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) and immune-response genes9, while the study that provided this information included a limited number of TNBC samples. Recently, claudin-low tumors were described as enriched in metaplastic histology variants, with lower levels of genomic instability, mutational burden, and targetable driver aberrations. Although the latter study identified claudin-low subtype to be associated with poor prognosis10, the heterogeneity among these studies requires further evidence to fully elucidate if the claudin low subtype can be intrinsically prognostic.

Further evidence demonstrated that TNBC is not a unique disease, encompassing multiple entities with pronounced histopathological, transcriptomic and genomic heterogeneity. Nonetheless, TNBC has been uniformly treated with chemotherapy. Exploiting TNBC diversity may help identifying new targetable pathways. Despite several efforts, these molecular classifications have remained merely theoretic and out of the clinical practice. Interestingly, potential targetable alterations have been identified across TNBC subtypes. Herein, we summarize the main evidence that defined transcriptomic and genomic heterogeneity of TNBC. Furthermore, we point out current and emerging biomarker-driven treatments for TNBC subtypes and describe the most common mechanisms of drug resistance for approved therapies in TNBC. Lastly, we discuss the challenges and possible future directions in the implementation of a biomarker-driven drug development in TNBC, potentially resulting in a practical classification of this BC subtype.

Tumor heterogeneity of TNBC: an unsolved conundrum

TNBCs have several histology variants such as poor tumor differentiation, presence of metaplastic elements, medullary features, and stromal lymphocytic response11–16. In spite of this, TNBC spectrum also encompasses low-grade neoplasms. Despite being rare, these low-grade variants range from tumors with no or uncertain metastatic potential to invasive carcinomas. Several studies suggested that at least two subsets of low-grade TNBCs can be distinguished, including the low-grade TN breast neoplasia family (microglandular adenosis, atypical microglandular adenosis, and acinic cell carcinoma) and the salivary gland-like tumors of the breast17. Interestingly, these latter are characterized by salivary gland-like morphologic features and are often driven by specific genetic alterations, such as adenoid cystic and secretory carcinomas that are underpinned by the MYB-NFIB and ETV6-NTRK3 fusion genes, respectively18,19.

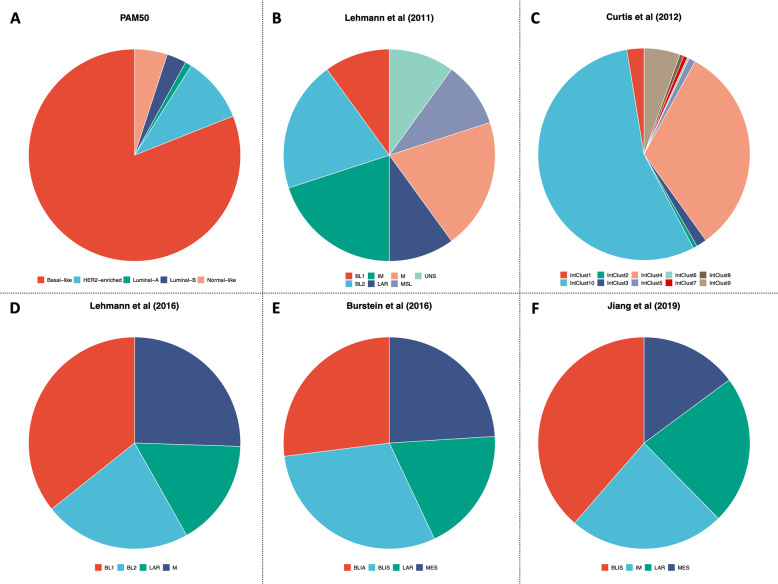

Besides the histopathological differences, TNBC displays great heterogeneity also at transcriptomic level. The landmark study by Lehmann et al. 20 identified seven clusters of TNBC, namely basal-like 1 (BL1), basal-like 2 (BL2), immunomodulatory (IM), mesenchymal (M), mesenchymal stem-like (MSL), luminal androgen receptor (LAR), and unstable (UNS). Among the basal-like subtypes, BL1 is enriched in cell cycle regulator and DNA damage response pathways, while the BL2 shows high levels of growth factor and metabolic pathways, as well as an increased myoepithelial marker expression. The IM subtype is characterized by immune cell processes and immune signaling cascades. Although the M and MSL subtypes are quite similar at transcriptomic level being enriched for genes implicated in cell motility and EMT, the MSL subtype shows lower expression of genes associated with cellular proliferation and is enriched for genes related to mesenchymal stem cells. Lastly, the LAR subtype has luminal-like gene expression pattern, despite ER negativity. Albeit Lehmann et al. 20 had provided a proof-of-concept for personalized therapies in TNBC, further studies did not confirm a prognostic value for these subtypes21. Accordingly, subsequent efforts21–25 refined the TNBC molecular clusters into four tumor-specific subtypes (Fig. 1), each presenting different GEP, response to standard treatments and prognosis. These achievements were mainly gained thanks to the application of multi-omics profiling and single-cell analysis technologies, which allow preventing samples’ contamination by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and other tumor microenvironment (TME) components26,27.

Fig. 1. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes across studies.

Transcriptomic-based and gene expression-based subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) according to PAM5028 (a) and defined by Lehmann et al.20,22 (b and d), Curtis et al.24 (c), Burstein et al.23 (e), and Jiang et al.25 (f). BLIA basal-like immune-activated, BLIS basal-like immunosuppressed, BL1 basal-like 1, BL2 basal-like 2, IM immunomodulatory, IntClust integrative clusters, LAR luminal androgen receptor, M mesenchymal, MES mesenchymal, MSL mesenchymal stem-like, UNS unstable. Figures was generated by reanalysis of publicly available studies and open-source platforms (cBioPortal: https://www.cbioportal.org).

Along with transcriptional heterogeneity, TNBC is also characterized by complex genomes, dictated by high genetic instability and intricate patterns of copy number alterations and chromosomal rearrangements28–32. TNBCs present few highly recurrently mutated genes, being enriched in somatic mutations of tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN). Conversely, driver alterations in genes of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, including PIK3CA mutations, have been described in ∼10% of cases28. Moreover, genomic analysis of the TNBC residual disease specimens after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) revealed at least one potentially-targetable genetic alteration33. Lately, Bareche et al. 34 reported the genomic alterations characteristic of each TNBC molecular subtype. BL1 tumors have high levels of chromosomal instability, high rate of TP53 mutations (92%), copy-number gains and amplifications of PI3KCA and AKT2, and deletions in genes involved in DNA repair mechanisms. Conversely, the LAR subtype is characterized by higher mutational burden and enrichment in mutations of PI3KCA, AKT1 and CDH1 genes. Mesenchymal and MSL subtypes are associated with higher signature score for angiogenesis. As expected, the IM group showed high expression levels of immune response-associated signatures and checkpoint inhibitor genes, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Such enrichment in the IM tumors should be related to the contamination by the immune infiltrate22. Of note, LAR subtype was associated with a worst prognosis, while IM subtype showed to be associated with a better prognosis34. In addition, it is relevant to underline that when Bareche et al. tried to reproduce Lehmann’s TNBC classification, BL1, IM, LAR, M, and MSL were the more stable subtypes. On the other hand, BL2 and UNS subtypes lacked reproducibility, as already observed in previous studies21,35.

Considering the great genomic complexity and heterogeneity28–31, analysis of a single genetic alteration might not be informative of the mutational processes driving TNBC. Accordingly, the application of mathematical models and computational frameworks allowed deciphering and identifying mutational signatures36–38. By analyzing the patterns of single nucleotide variants, pivotal studies led to the identification of two mutational signatures that were consistent with the activity of the apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) family of deaminases. APOBEC enzymes activity has a central role in tumorigenesis, leading to subclonal expansion and intratumor heterogeneity across several tumors39. In BC, the role of APOBEC-associated mutagenesis has been extensively studied in ER-positive disease40, while scant information on TNBC is available. Therefore, additional research is needed to fully elucidate prognostic and therapeutic implications of mutational signatures in TNBC.

Lastly, histopathological and genomic characterization of tumor biopsy specimens can present several limitations, including a limited representativeness of the entire tumor mutational repertoire and its heterogeneity, technical issues in tissue processing and mutation detection, and low feasibility in some clinical circumstances41. Accordingly, some tools, referred to as “liquid biopsies”, have been implemented to identify and quantify tumor fractions released into the peripheral blood, including circulating tumor cells (CTCs), exosomes, and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)42. Different studies highlighted that CTCs-based and ctDNA-based liquid biopsies are able to real-time monitor disease evolution and identify patient with high-risk of disease recurrence and poor prognosis43–45. In TNBC, ctDNA-based genome-wide profiling demonstrated to be useful in characterizing tumor-specific alterations, as well as in predicting patient prognosis46–48. Considering that these observations mainly derive from retrospective and secondary analyses, further prospective trials investigating new treatments matched with liquid biopsy-assessed genomic alterations are warranted.

Biomarkers-driven treatments in TNBC

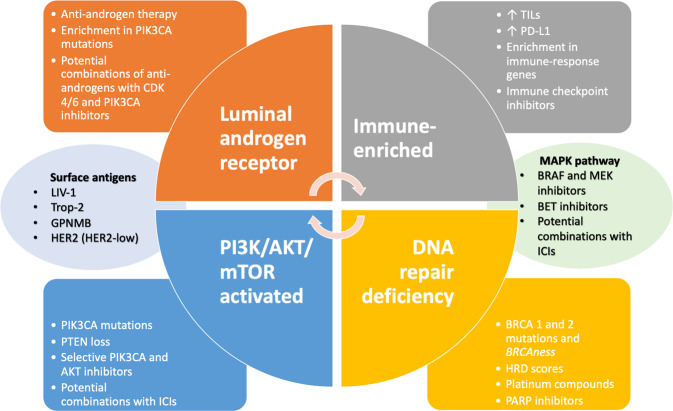

The history of TNBC has observed several attempts to identify biomarkers capable to refine the patients’ selection and predict responses to standard and innovative therapies. Discovery and clinical implementation of new drugs in biomarker-driven manner is essential to decrypt the multitude mechanisms of resistance conferring poorer prognosis to TNBC patients (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Biomarker-driven therapeutic approaches in triple-negative breast cancer.

Tackling hormone receptors in TNBC: the androgen pathway

Pivotal studies on TNBC led to the identification of the LAR subtype20–22. Representing 10–15% of all TNBCs, androgen receptor (AR)-positive tumors are characterized by low proliferation rates and luminal-like gene expression profile, being inherently resistant to chemotherapy20–23,34,49. By contrast, AR expression assessed by IHC does not seem to imply a worse prognosis50. AR is a ligand-activated transcription factor that exerts genomic and non-genomic effects on cells by involving different intracellular signaling pathways and promoting tumor proliferation and invasiveness51,52.

AR has been identified as an appealing target for the TNBC treatment, prompting the clinical implementation of anti-androgens molecules. Androgen manipulation can be generally obtained with the use of direct AR-blockers. The non-steroidal AR inhibitor bicalutamide was tested in a phase II trial53 that included patients with pretreated, metastatic AR-positive TNBC, using a minimal threshold of IHC expression of 10%. The study failed to show any benefit, corresponding to a clinical benefit rate (CBR) of 18% and median progression-free survival (mPFS) of 12 weeks. Based on the possibility to overcome acquired androgen-resistance across cytoplasmatic and nuclear AR-related pathways, the non-steroidal anti-androgen enzalutamide was tested in a phase II trial in patients with pretreated TNBCs with nuclear AR staining >0%54. In the overall population, CBR and mPFS was 25% and 2.9 months, respectively. Interestingly, TNBCs expressing AR more than 10% and enriched for an androgen-driven gene signature seemed to be more sensitive to enzalutamide (mPFS 32 vs. 9 weeks)55. The clinical experience with the steroidal inhibitor of androgenesis abiraterone appeared consistent with enzalutamide, for AR of 10% or more, resulting in a mPFS of 2.8 months and CBR of 20%56.

Taken together, these data suggest a narrow benefit of androgen blockers in TNBC. Although androgen blockade has demonstrated a potential value in AR-positive TNBC, the predictive role of AR expression alone needs a better characterization. Accordingly, a deeper androgen suppression or AR degradation could improve the anti-tumoral activity, as being tested in ongoing clinical trials (Table 1). Moreover, co-targeting possible mechanisms of escape in alternative pathways implicated in androgen-resistance can represent an attractive strategy, as validated in ER-positive BC with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors and PI3K blockers57,58. Considering that the LAR subtype demonstrated highly sensitivity to CDK 4/6 inhibition in preclinical models59, as well as higher mutational burden and enrichment in mutations of the PI3K pathway34,60,61, clinical trials testing CDK 4/6 and PI3K-selective inhibitors in combination with novel anti-androgens are currently ongoing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected ongoing phase II or III clinical trials in TNBC.

| Agent(s) | Target(s)/pathway(s) | Phase | Setting | Sample size | Estimated study completion | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotherapy | ||||||

|

Pembrolizumab IL-12 gene therapy L-NMMA Chemotherapy# |

PD-1 IL-12 |

II | (Neo)-adjuvant | 43 | Aug 2020 | NCT04095689 |

|

HLX10 Chemotherapy## |

PD-1 | III | (Neo)-adjuvant | 522 | Apr 2027 | NCT04301739 |

|

Atezolizumab Ipatasertib Paclitaxel |

PD-L1 AKT |

III | Advanced/metastatic | 1155 | Oct 2025 | NCT04177108 |

|

Spartalizumab LAG525 Carboplatin |

PD-1 LAG-3 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 88 | Jan 2021 | NCT03499899 |

|

Toripalimab Nab- paclitaxel |

PD-1 | III | Advanced/metastatic | 660 | Feb 2022 | NCT04085276 |

|

Camrelizumab Famitinib Carboplatin |

PD-1 | II | Advanced/metastatic | 46 | Jan 2021 |

(FUTURE-C-PLUS) |

|

Lacnotuzumab Gemcitabine Carboplatin |

M-CSF | II | Advanced/metastatic | 50 | Mar 2020 | NCT02435680 |

|

Nivolumab Capecitabine |

PD-1 | II | Post-neoadjuvant without pCR | 45 | Dec 2022 | NCT03487666 (OXEL) |

|

Pembrolizumab Imprime PGG |

PD-1 Dectin |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 64 | Nov 2021 | NCT02981303 |

| Avelumab | PD-L1 | III | Adjuvant | 335 | June 2023 |

(A-BRAVE) |

|

Pembrolizumab Tavokinogene telseplasmid (intratumoral) |

PD-1 | II | Advanced/metastatic | 25 | Jan 2020 | NCT03567720 (KEYNOTE-890) |

|

Nivolumab Ipilimmumab Capecitabine Radiation therapy |

PD-1 CTLA-4 |

II | Adjuvant | 98 | March 2022 |

(BreastImmune03) |

|

Durvalumab CFI-400945 |

Pd-L1 Plk4 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 28 | Dec 2022 | NCT04176848 |

|

KN046 Nab-paclitaxel |

PD-L1 CTLA-4 |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 90 | Sept 2021 | NCT03872791 |

|

Atezolizumab Ipatasertib Ladiratuzumab-Vedotin Bevacizumab Cobimetinib RO6874281 Selicrelumab Chemotherapy |

PD-L1 AKT LIV-1 VEGF MEK IL-2 CD40 |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 310 | Aug 2021 | NCT03424005** (MORPHEUS-TNBC) |

|

PF-04518600 Avelumab Binimetinib Utomilumab |

OX-40 PD-L1 MEK 4-1BB/CD137 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 150 | June 2023 | NCT03971409 (inCITe) |

|

Atezolizumab Cobimetinib Nab-paclitaxel/paclitaxel |

PD-L1 MEK |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 269 | Apr 2020 | NCT02322814 |

|

Durvalumab Oleclumab Paclitaxel Carboplatin |

PD-L1 CD73 |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 171 | Dec 2022 | NCT03616886 (SYNERGY) |

|

CAN04 Chemotherapy |

IL1RAP | I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 100 | Oct 2020 | NCT03267316 (CANFOUR) |

|

Sarilumab Capecitabine |

IL-6 | I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 50 | June 2020 | NCT04333706 (EMPOWER) |

|

NKTR-214 Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

CD122 PD-1 CTLA-4 |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 780 | Dec 2021 | NCT02983045 (PIVOT 02) |

|

Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

PD-1 CTLA-4 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 30 | Oct 2022 | NCT03789110 (NIMBUS) |

| PARP inhibitors and other DNA modulating agents | ||||||

|

Niraparib Pembrolizumab |

PARP PD-1 |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 121 | Mar 2020 |

(TOPACIO) |

| Olaparib | PARP | III | Adjuvant | 1836 | Nov 2020 |

(OlympiA) |

|

Olaparib AZD6738 AZD1775 |

PARP ATR WEE1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 450 | Nov 2020 | NCT03330847 |

|

Olaparib Durvalumab |

PARP PD-L1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 28 | Dec 2020 | NCT03801369 |

|

Olaparib Durvalumab Bevacizumab |

PARP PD-L1 VEGF |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic gBRCAm | 427 | Sep 2022 |

(MEDIOLA) |

|

Talazoparib Avelumab |

PARP PD-L1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 242 | Aug 2020 | NCT03330405 |

|

Olaparib Durvalumab |

PARP PD-L1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 60 | Apr 2020 |

(DORA) |

|

Olaparib Platinum-based CT |

PARP | II/III | (Neo)-adjuvant | 527 | Jan 2032 |

(PARTNER) |

|

Olaparib Durvalumab AZD6738 |

PARP PD-L1 ATR |

II | (Neo)-adjuvant | 81 | Dec 2025 |

(PHOENIX) |

| Olaparib | PARP | II | Advanced/metastatic | 91 | Dec 2020 | NCT00679783 |

|

Olaparib Durvalumab |

PARP PD-L1 |

I/II | (Neo)-adjuvant | 25 | Apr 2020 | NCT03594396 |

|

Talazoparib ZEN003694 |

PARP Bromodomain |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 29 | Jan 2021 | NCT03901469 |

| Talazoparib | PARP | II | Advanced/metastatic | 40 | Aug 2021 | NCT02401347 |

|

Veliparib Cisplatin |

PARP | II | Advanced metastatic | 333 | Oct 2021 | NCT02595905 |

|

Pembrolizumab Olaparib Gemcitabine Carboplatin |

PD-1 PARP |

II/III | Advanced/metastatic | 932 | Jan 2026 | NCT04191135 |

| Olaparib | PARP | II | Advanced/metastatic | 39 | Nov 2021 | NCT03367689 |

| PI3K/mTOR/AKT/PTEN pathway | ||||||

|

Tak-228 Tak-117 Cisplatin Nab-paclitaxel |

TORC 1/2 PI3Kα |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 20 | June 2022 | NCT03193853 |

|

LY3023414 Prexasertib |

PI3K/mTOR CHEK1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 10 | Aug 2021 |

(ExIST) |

|

Everolimus Carboplatin |

mTOR | II | Advanced/metastatic | 72 | June 2021 | NCT02531932 |

|

Ipatasertib Paclitaxel |

AKT | II/III | Advanced/metastatic | 450 | Dec 2021 |

(IPATunity130) |

|

Alpelisib Nab-paclitaxel |

PIK3CA | II | Advanced/metastatic | 62 | Dec 2021 | NCT04216472 |

|

Capivasertib Paclitaxel |

AKT | III | Advanced/metastatic | 800 | Sept 2021 | NCT03997123 (CapItello290) |

|

IPI-549 Atezolizumab Bevacizumab Nab-paclitaxel |

PI3K-gamma PD-L1 VEGF |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 90 | Aug 2022 | NCT03961698 (MARIO-3) |

|

Gedatolisib Talazoparib |

PI3K/mTOR PARP |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 54 | May 2022 | NCT03911973 |

|

Vistusertib Selumetinib |

mTORC1/2 MEK |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 118 | Mar 2020 | NCT02583542 (TORCMEK) |

|

Capivasertib Ceralasertib Adavosertib Olaparib |

AKT ATR WEE1 PARP |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 64 | Mar 2020 | NCT02576444 (OLAPCO) |

| RAS/MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| ONC 201 |

ERK AKT |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 90 | Dec 2027 | NCT03394027 |

| Antibody-drug conjugates | ||||||

|

Sacituzumab govitecan Chemotherapy |

Trop2 | III | Advanced/metastatic | 529 | July 2020 | NCT02574455 (ASCENT) |

| CAB-ROR2-ADC BA3021 | ROR2 | I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 120 | May 2022 | NCT03504488 |

| SKB264 | Trop2 | I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 78 | Dec 2022 |

(A264) |

| EnfortuMab Vedotin | Nectin-4 | II | Advanced/metastatic | 240 | Apr 2023 |

(EV-202) |

| Androgen pathway | ||||||

| Orteronel | 17α-hydroxylase | II | Advanced/metastatic | 71 | Feb 2020 | NCT01990209 |

|

Enobosarm Pembrolizumab |

AR PD-1 |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 29 | Nov 2020 | NCT02971761 |

|

Bicalutamide Palbociclib |

AR PARP |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 51 | Nov 2020 | NCT02605486 |

|

Enzalutamide Taselisib |

AR PI3K |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 73 | Dec 2021 | NCT02457910 |

|

Enzalutamide Alpelisib |

AR PIK3CA |

II | Advanced/metastatic | 28 | Dec 2020 | NCT03207529 |

| Bicalutamide | AR | II | Advanced/metastatic | 262 | Dec 2020 | NCT03055312 (SYSUCC-007) |

| Enzalutamide | AR | II | Adjuvant | 50 | May 2020 | NCT02750358 |

|

Enzalutamide Paclitaxel |

AR | II | Neoadjuvant | 37 | Sept 2021 | NCT02689427 |

|

Bicalutamide Ribociclib |

AR PARP |

I/II | Advanced/metastatic | 11 | Sept 2021 | NCT03090165 |

|

Darolutamide Capecitabine |

AR | II | Advanced/metastatic | 90 | Sept 2021 | NCT03383679 (START) |

| Orteronel | 17α-hydroxylase | II | Advanced/metastatic | 71 | Feb 2020 | NCT01990209 |

IL-2 gene therapy refers to Adenoviral-mediated IL-12. L-NMMA, NG-monomethyl-L-arginine, inhibitor of the nitric oxide synthetase. Famitinib, inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinase receptor anti c-Kit, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 and 3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor and FMS-like tyrosine kinases Flt1 and Flt3. M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor. pCR, pathological complete response. Tavokinogene telseplasmid is aDNA plasmid that encodes genes for both the p35 and p40 subunits of the heterodimeric human interleukin 12 (hIL-12) protein.

PLK4 Polo-like kinase 4, IL1RAP Interleukin 1 Receptor Accessory Protein, pCR pathological complete response, DDR DNA damage repair.

#standard neoadjuvant regimen with anthracyclines and taxanes.

##nab-paclitaxel, carboplatin, doxorubicin/epirubicin and cyclophosphamide.

**umbrella study evaluating the efficacy and safety of multiple immunotherapy-based treatment combinations.

Refining the selection per biomarker in targeting PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR (PAM) pathway is frequently dysregulated in cancer, promoting cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. The activation of the PAM pathway can result from the oncogenic activation of growth factor receptors and direct oncogenic activation of the PAM proteins or their regulators, including PTEN and inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase (INPP4B)62.

PIK3CA is one of the most frequent mutated genes in TNBC (∼10%), being enriched in basal-like and LAR subtypes24,25,28–34,36,63. Notably, metastatic TNBCs carrying PIK3CA mutations seem to have better overall survival (OS) than wild-type counterparts. However, such observation could be partially explained by an enrichment in PIK3CA mutations in luminal BCs that loss ER expression in the metastatic setting63. Furthermore, loss-of-function of PTEN and INPP4B have been described in up to one-third of the TNBCs, especially in BLBC where heterozygous loss of PTEN has been identified in >45% of cases28.

Despite the key role in tumorigenesis, the clinical implementation of drugs targeting PAM molecules has resulted in disappointing results so far. The perception is that the regulation of single downstream effectors may activate uncontrolled resistance feedback loops. Conversely, the combination of multiple agents against PAM molecules has often resulted in unacceptable toxicity, mainly with mTOR and pan-PI3K inhibitors64,65. Thus, biomarker selection and more selective inhibitors were argued. In a phase I/II trial of patients with HER2-negative BC66, the α-selective PI3K inhibitor alpelisib combined with nab-paclitaxel provided the largest benefit in the population harboring PIK3CA mutations (mPFS 13 months). Similar results were obtained in the phase II randomized trial LOTUS, where the AKT inhibitor ipatasertib combined with paclitaxel provided meaningful benefit in patients carrying PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN alterations67,68. Similarly, the phase II randomized study PAKT confirmed an improvement in PFS and OS in the biomarker-enriched (PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN) population treated with the AKT inhibitor capivasertib added to first-line chemotherapy69.

As dominated by PAM alterations, a further step to target TNBC per biomarker will be driven by the deeper understanding of the collateral activated pathways and biological implications of PAM dysregulations and pharmacological inhibition. In this perspective, combined approaches with AR, CDK 4/6, and double PI3K/mTOR inhibitors are under investigation (Table 1). Furthermore, considering the metabolic function of PAM signaling in the insulin response, it has been proposed that the reactivation of the insulin feedback induced by PI3K inhibitors may reactivate the PI3K-mTOR signaling axis in tumors, thereby compromising treatment effectiveness70. Accordingly, a medical intervention capable to reduce the insulin secretion could enhance the benefit of PI3K inhibitors, for instance through a switch of the metabolic use of nutrients on a ketogenic profile71. Despite preliminary, these findings support a possible synergistic action of PAM agents and dietary interventions, as investigated in several clinical trials72.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades is a finely-controlled signal transduction pathway consisting of phosphoserine/threonine kinases that mediates the cellular response to external signals73. The pathway proceeds from the sequential phosphorylation of several molecules (Erk, Mek, and Raf), and is finely regulated by GTPase proteins, including the RAS proteins.

Alterations in genes encoding for components of the MAPK pathway, including KRAS, BRAF, and MEK1/2, are described in less than 2% of TNBCs28. However, somatic alterations of regulatory proteins that contribute to the oncogenic dysregulation of MAPK pathway have been more commonly reported, such as the negative regulator of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 dual specificity protein phosphatase 4 (DUSP4)33,74. In TNBC, the regulation of MAPK has demonstrated to be potentially targetable, suppressing redundant pathways converging on the cascade. For instance, EGFR overexpression was shown to upregulate the Ras/MAPK signaling, becoming an appealing therapeutic target75. However, neither monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) nor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting EGFR demonstrated meaningful activity in TNBC in phase II/III trials76–81. Some possible explanations can be offered to explain the clinical failure of anti-EGFR agents in TNBC82. First, the EGFR signaling may change during disease progression, with low EGFR expression in the metastatic cells, despite an overexpression in primary tumor83. Second, the significant interaction between EGFR and other oncogenic signaling pathways (MET, PI3K/mTOR, and MEK pathways) might render TNBC cells intrinsically resistant to EGFR-specific inhibition. In this way, further studies investigating new TKIs84, as well as novel combinatorial strategies are underway.

Moreover, given the central role of MAPK dysregulation in BC tumorigenesis, the opportunity to target MEK in TNBC patients with the selective inhibitor cobimetinib was explored in the phase II trial COLET. Again, the addition of cobimetinib to first-line paclitaxel did not demonstrate significant improvement in mPFS85. Interestingly, the biomarker explorative analysis showed a potential immunomodulatory effect of cobimetinib in increasing the immune infiltration within TME86. Consistently, the part 2 of COLET study was designed to test the combination of cobimetinib, nab-paclitaxel and atezolizumab, with preliminary signs of activity in the PD-L1-positive population87. Recently, the concomitant inhibition of MEK and bromodomain and extraterminal motif (BET) has shown synergistic activity in TNBC preclinical models overexpressing the neuroendocrine-associated oncogene MYCN88, providing a rationale to explore this combination in patients with MYCN-positive TNBC.

Comparable to other MAPK pathway components, somatic mutations of BRAF have been reported in less than 1% of BCs89. Although no specific data on TNBC patients are available, compelling evidence suggests potential clinical benefit for BRAF inhibition in tumors carrying V600E BRAF mutations90,91. Overall, the evidence converges on the concept that the pharmacological manipulation of MAPK in TNBC can be effective when the MAPK pathway is dysregulated, commonly for genomic alterations of its regulators. In this way, ongoing trials are exploring the opportunity to target MAPK with single agents in biomarker-selected patients for MAPK dysregulations, such as DUSP4 expression92, as well as the potential immune-enhancing effect by the pharmacological inhibition of Ras/MAPK pathway93 (Table 1).

Tailoring the homologous recombination repair mechanisms and its regulators: the BRCAness paradigm

Defects in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) repair mechanisms are characteristic of TNBC, as a result of either germline or somatic mutations in BRCA1/2 and other genes involved in DNA repair94. Germline mutations in BRCA1/2 occur in ∼10% of TBNC patients and increase the lifetime risk of BC to 60–70%95–97. Notably, BRCA1-mutated BCs usually display a basal-like phenotype98. Key feature of BRCA1/2 mutant TNBC is the deficiency of homologous recombination repair (HRR), making essential other DNA repair machineries to maintain the integrity of the genome. Similar to BRCA1/2, HR deficiency (HRD) can result from the loss of several proteins, contributing to the acquisition of a BRCA-like phenotype (also defined BRCAness)99. The term has been introduced to define the situation in which an HRR defect exists in a tumor in the absence of a germline BRCA1/2 mutation, conferring sensitivity to poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPis) based on the principle of synthetic lethality99–101. Computational modeling of sequencing data allowed to identify additional tumors with somatic loss or functional deficiency of BRCA1/2 where no mutations were detected, potentially expanding the BC population amenable to PARPis102.

Nowadays, germline pathogenetic mutations of BRCA1/2 are the only clinically validated biomarkers of sensitivity to PARPis, based on the results of clinical trials testing olaparib, talazoparib and veliparib in metastatic BC (Table 2)103–106. In addition, patients carrying BRCA pathogenic mutations showed to derive a greater benefit with DNA-targeting cytotoxic agents, as demonstrated in the phase III trial TNT that compared docetaxel to carboplatin in the first-line setting of metastatic TNBC107. Pre-specified analysis of biomarker-treatment interaction assessed the predictive role of germinal BRCA mutations and BRCAness alterations, including somatic BRCA1 methylation and HRD mutational signature (per Myriad assay)107. If on one hand germinal BRCA mutational status was able to predict the responses to carboplatin with a doubled overall response rate (ORR), on the other no difference could be detected by utilizing the other proposed biomarkers. Notably, patients with non-basal-like tumors (according to PAM50) derived greater benefit with docetaxel. Apparently, the benefit observed with platinum compounds seems applicable to other DNA-targeting agents, including anthracyclines, as showed in the INFORM trial that compared doxorubicin and cisplatin in the neoadjuvant setting108. In this trial, the single-agent platinum compound did not improve pCR rates compared to doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide. When head-to-head comparisons have been performed across different agents, data suggest that the selection for HRD can predict equally a benefit to DNA-disrupting agents, regardless of their pharmacological class. The phase II trial GeparOLA assessed the efficacy of neoadjuvant paclitaxel and olaparib vs. paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with HRD: overall, the study failed to show a difference in terms of pCR109. Eventually, the combination of PARPis and carboplatin did not result in a synergistic activity, across different settings of care, providing none or narrow added clinical benefit, at the cost of increased toxicity110,111.

Table 2.

Main results of phase II/III trials testing PARP inhibitors in breast cancer.

| Drug(s) | Phase | N | Population enrolled | Design | Primary endpoint | Results | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olaparib | III | 302 | Advanced gBRCA, HER2 negative, ≤ 2 prior lines of CT | Olaparib vs TPC | PFS |

Median PFS (mo) 7.0 vs 4.2 Median OS (mo) 19.3 vs 17.1 ORR 59.9% vs 28.8% |

OlympiAD |

| Olaparib | II | 102 | Neoadjuvant therapy for HER2 negative BC with gBRCA or tBRCA and/or high HRD score | Olaparib + paclitaxel → AC vs Carboplatin+ paclitaxel → AC | pCR |

pCR 55.1% vs 48.6% |

GeparOLA |

| Veliparib | III | 634 | Neoadjuvant therapy for stage II/III TNBC | Carboplatin + paclitaxel + veliparib → AC vs carboplatin+ paclitaxel + placebo →AC vs placebo+placebo + paclitaxel→ AC | pCR |

pCR 58% vs 53% vs 31% |

BrighTNess |

| Veliparib | II | 116 | Neoadjuvant therapy for stage II/III TNBC | Carboplatin + paclitaxel + veliparib/placebo → AC | pCR |

pCR 51% vs 26% |

I-SPY 2 |

| Veliparib | II | 290 |

Advanced gBRCA 0–2 prior lines of CT |

Carboplatin+ paclitaxel + veliparib vs carboplatin+ paclitaxel + placebo vs temozolamide + veliparib | PFS |

Median PFS (mo) 14.1 vs 12.3 vs 7.4 Median OS (mo) 28.3 vs 25.9 vs 19.1 ORR 77.8% vs 61.3% vs 28.6% |

BROCADE |

| Veliparib | III | 513 |

Advanced gBRCA, HER2 negative 0–2 prior lines of CT |

Carboplatin + paclitaxel + veliparib vs carboplatin + paclitaxel + placebo | PFS |

Median PFS (mo) 14.5 vs 12.6 Median OS (mo) 33.5 vs 28.2 ORR 75.% vs 74.1% |

BROCADE3 |

| Talazoparib | III | 431 |

Advanced gBRCA, HER2 negative ≤ 3 prior lines of CT |

Talazoparib vs TPC | PFS |

Median PFS (mo) 8.6 vs 5.8 Median OS (mo) 22.3 vs 19.5 Response rate 62.6% vs. 27.2% |

EMBRACA |

| Niraparib | III |

Advanced gBRCA, HER2 negative ≤ 2 prior lines of CT |

Niraparib vs TPC | PFS |

Ongoing (no results available) |

BRAVO |

AC doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide, CT, chemotherapy, gBRCA germline BRCA mutation, HRD score Homologous Recombinant Deficiency score, iDFS invasive disease free survival, mo months, ORR objective response rate, pCR pathological complete response, PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, tBRCA somatic BRCA mutation, TPC treatment of physician’s choice chemotherapy.

The expansion of the concept of BRCAness beyond BRCA means to deepen the identification and study of key regulatory mechanisms of HRR, in order to develop predictive biomarkers for DNA disrupting agents and discover new pharmacological targets. ATR and its downstream effector (e.g., CHK1, WEE1, Aurora A, Polo-Like Kinase 1) have been proposed as possible modulators of BRCAness, potentially extending the spectrum of DNA-targeting and sensitivity to PARPis to a greater proportion of BC patients. These effectors seem to link the cell cycle control and the DNA damage response, both commonly disrupted mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis. Preliminary results have been reported for the Aurora A kinase selective inhibitor alisertib combined with paclitaxel112 and the Aurora A inhibitor ENMD-2076113 in phase I trials. Similarly, a combination trial of TNBC, with a pre-specified enrichment of BRCA mutated patients, assessed the benefit of the ATR-blocker M6620 with cisplatin, showing preliminary encouraging results114. The only suggested biomarker emerged for the HRR modulator targeting CHK1, GDC-0425, is TP53-mutated, tested as a chemotherapy-potentiating agent in patients with solid tumors, including TNBC115.

So far, no clinical experience with multiple HRR modulators is available, and clinical trials are ongoing. For the potential role in predicting a benefit with chemotherapy and PARPis, HRD has been proposed for the biomarker-enhanced design of clinical trials, with single agent PARPis and other modulators of the DNA damage response as single agents or in combination (Table 1). In addition, the preclinical evidence of a potential role for PI3K blockade in determining BRCAness phenotype in BRCA1/2-proficient TNBC116 would potentially expand the BC population likely benefiting from PARPis. However, a phase I trial testing the combination of buparlisib and olaparib reported modest results in terms of efficacy with relevant additional toxicity117. Lastly, preclinical evidence showed a potential immunomodulant activity for PARPis, including PD-L1 upregulation on cancer cell and activation of immune-response pathways such as STING118–120, leading to the design of clinical trials testing the combination of PARPis and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)121,122. Other agents targeting DNA repair proteins in combination with immunotherapy are also being currently investigated (Table 1).

Toward a precision immunotherapy for TNBC

The clinical landscape of drug development for immunotherapy agents in TNBC is complex and wide. Considering the key role of immune system in influencing responses to standard chemotherapy and prognosis of TNBC123–126, several trials tested ICIs targeting PD-1/PD-L1, showing limited activity as monotherapy and promising results in combination with chemotherapy (Table 3)127–134. The phase III trial IMpassion130, which tested the combination of atezolizumab with nab-paclitaxel in the first-line metastatic setting, established a potential role of immunotherapy in patients with PD-L1-positive TNBC, defined as ≥1% in tumor-infiltrating immune cells based on the IHC SP142 assay135,136.

Table 3.

Main results of clinical trials testing immune checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer.

| Drug(s) | Phase | N | PD-L1 stratified | ORR (%) | Median PFS | Median OS | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | |||||||

| Pembrolizumab | I | 32 | ≥1% TC | 18.5 | 1.9 (1.7–5.5) | 11.2 (5.3-NR) |

KEYNOTE-012 |

| Overall | 5.3 | 2.0 (1.9–2.0) | 9.0 (7.6–11.2) | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | II | 170 | ≥1 CPS | 5.7 | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 8.8 (7.1–11.2) |

KEYNOTE-086-A |

| Negative | 4.7 | 1.9 (1.7–2.0) | 9.7 (6.2–12.6) | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | II | 84 | ≥1 CPS | 21.4 | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 18.0 (12.9–23.0) |

KEYNOTE-086-B |

| Overall | 9.6 | 2.1 (1.33–1.92) | 9.9 (0.82–1.15) | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | III | 622 | ≥1 CPS | 12.3 | 2.1 (1.08–1.68) | 10.7 (0.69–1.06) |

KEYNOTE-119 |

| ≥10 CPS | 17.7 | 2.1 (0.82–1.59) | 12.7 (0.57–1.06) | ||||

| ≥20 CPS | 26.3 | 3.4 (0.49–1.18) | 14.9 (0.38–0.88) | ||||

| Overall | 5.2 | 5.9 (5.7–6.9) | 9.2 (4.3–NR) | ||||

| Avelumab | I | 58 | ≥10% IC | 22.2 | NA | NA |

JAVELIN |

| <10% IC | 2.6 | NA | NA | ||||

| Atezolizumab | I | 115 | ≥1% IC | 10 | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 8.9 (7.0–12.6) | NCT01375842 |

| Combinations | |||||||

| Pembrolizumab + eribulin | I/II | 106 | Overall | 26.4 | 4.2 (4.1–5.6) | 17.7 (13.7–NR) |

ENHANCE-1 |

| ≥1 CPS (1 line) | 34.5 | 6.1 (4.1–10.2) | 21.0 (8.3–29.0) | ||||

| <1 CPS (1 line) | 16.1 | 3.5 (2.0–4–2) | 15.2 (12.8–19.4) | ||||

| ≥1 CPS (2–3 line) | 24.4 | 4.1 (2.1–4.8) | 14.0 (11.0–19.4) | ||||

| <1 CPS (2–3 line) | 18.2 | 3.9 (2.3–6–3) | 15.5 (12.4-18-7) | ||||

| Atezolizumab + nabpaclitaxel | I | 33 | Overall | 39.4 | 9.1 (2.0–20.9) | 14.7 (10.1–NR) | NCT01375842 |

| Atezolizumab + nabpaclitaxel | III | 902 | Overall | 56 | 7.2 (0.69–0.92) | 21.0 (0.72–1.02) |

IMpassion130 |

| ≥1% IC | 58.9 | 7.5 (0.49–0.78) | 25.0 (0.54–0.93) | ||||

PFS and OS are expressed as median (95% confidence interval), in months.

PFS progression-free survival OS overall survival, NR not reached, TC tumor cells, CPS combined positive score, IC immune cells, NA not available.

So far, PD-L1 is the only biomarker applied in clinical practice for the selection of patients more likely to respond to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs. However, how to define the “PD-L1-positive” population in the clinical practice remains challenging. Even if the biomarker analysis of IMpassion130 showed a correlation between the expression of PD-L1 on tumor and immune-infiltrating cells, issues on the IHC assay to apply and the definition of the optimal threshold for “positivity” could still be arisen. When SP142 assay was compared with the other commercially available antibodies 22C3 (expressed as the percentage of viable staining positive to PD-L1 or tumor proportion score) and SP263 (PD-L1 staining on immune and tumor cells), the latter were both able to identify more patients with PD-L1-positive tumors137. Conversely, within the Impassion130 trial, the patients defined “PD-L1-positive” by 22C3 and SP263 clones derived lower PFS and OS benefit than with SP142. Furthermore, despite the clinical implementation of PD-L1 as a clinically useful biomarker, concerns have been raised on the broad utility of PD-L1 expression for selecting patients. As a dynamic biomarker, PD-L1 can be differentially expressed in primary and metastatic sites and responses are observed in PD-L1 negative patients as well138.

In the TNBC early setting, the role of PD-L1 becomes particularly controversial. In the phase III trial KEYNOTE-522, the addition of pembrolizumab to anthracycline, taxane and platinum neoadjuvant regimen improved pCR rates (64.8% vs. 51.2%)139, regardless of PD-L1 expression140. In another neoadjuvant phase III trial (NeoTRIPaPDL1), the addition of atezolizumab to carboplatin and nab-paclitaxel failed to show an improvement in pCR compared to standard chemotherapy alone141. Of note, the exploratory analysis identified the PD-L1 expression as the strongest predictor of response to the immune-chemotherapy combination. These contrasting results might be partially explained by the different chemotherapy regimens used. As highlighted in the TONIC trial142, the presence of an anthracycline or platinum compound as induction chemotherapy may create a more favorable TME and increase pCR to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in TNBC.

Overall, PD-L1 is still a suboptimal biomarker to properly select TNBC patients for immunotherapy-based treatments. Therefore, additional biomarkers have been proposed or are currently under investigation143.

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has emerged as biomarker of improved survival in cancer patients receiving ICIs144,145. However, limited data are available on the value of TMB in BC, also considering the low proportion of hypermutated BCs146. A recent study on patients with metastatic TNBC treated with ICIs showed that high TMB (≥6 mutations/megabase) was significantly associated with longer PFS, but not OS147. Preclinical evidence suggested that neoantigen quality, rather than quantity, is the major determinant for inducing effective and durable immune responses and shaping response to ICIs148, as demonstrated in melanoma and lung cancer models149. Accordingly, further research is ongoing to develop pipelines for identifying specific mutational signatures that may be associated with anti-tumor immune response in BC150–152. As described above, an hypermutated phenotype in BC can be sustained with APOBEC-associated mutational processes in ∼60% of cases36–39, while only few hypermutated tumors present HRD (1%) or dysregulation of the DNA polymerase-epsilon (3.4%)146. This makes clear that HRD alone is not able to predict a hypermutated phenotype nor a pronounced likelihood of response to ICIs. Lastly, an in-silico analysis showed that immune infiltration was associated with TMB in tumors driven by recurrent mutations, but not in those driven by copy number alterations such as BCs153. Overall, further research is needed to clarify the role of these biomarkers in predicting ICIs efficacy in TNBC.

The spatial architecture and arrangement of TILs have been primarily addressed, initially assessing the presence, pattern and density and then moving to their functional characterization. While ICIs mainly act reinvigorating a pre-existing anti-tumor immune response, TILs density has been associated with ICIs activity in several solid tumors154. In BC, these findings were confirmed in patients with metastatic TNBC who were treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy in the phase II KEYNOTE-086 trial155, where TILs levels were independent predictors of response. In addition, the presence and density of pre-treatment and on-treatment stromal TILs were significantly associated with pCR in a cohort of the KEYNOTE-173 trial, which assessed the benefit of pembrolizumab added to NAC156. Similar results have been showed in exploratory biomarker analysis of the IMpassion130157 and KEYNOTE-119 trials158. Interestingly, the latter study showed that high TILs predicted favorable clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic TNBC treated with pembrolizumab, but not with chemotherapy, reinforcing the predictive value of this biomarker. Nevertheless, further evidence suggested that qualitative differences in TIL composition, as well as immune-related genetic signatures are able to fine-tune patients’ prognosis in TNBC and response to ICIs154,159,160. So far, no functional characterization of the immune infiltrate has been reported from controlled trials testing ICIs in TNBC.

Optimizing the delivery of cytotoxic agents via surface antigens: the model of antibody drug-conjugates

Drug delivery via antibody drug-conjugates (ADCs) sublimates the traditional concept of target in cancer treatment. So far, the most common use of mAbs in BC has been directed to an oncoprotein with a pathogenetic role in tumorigenesis. With the advent of ADCs, the identification of cell surface targets has now the explicit role to tag cancer cells, ensuring the univocal identification of the malignancy and providing a precise delivery of the conjugated payloads, either cytotoxic agents or biological molecules161. This demands a change in the perspective: identifying target molecules with a restricted expression on cancer cell surfaces, irrespective of their biological function. In the clinical setting, the identification and quantification of possible targets for ADCs have used IHC scores, both as a semiquantitative scale (e.g., 0 to 4+ for LIV-1 and Trop-2) or percentage of positive cells (e.g., GPNMB).

In BC, the pipeline of ADCs is being continuously growing161. Sacituzumab-govitecan-hziy is an ADC recognizing Trop-2 on cells to deliver the camptothecin-derived cytotoxic payload SN-38162. Trop-2 is a transmembrane calcium signal transducer and is overexpressed in many epithelial cancer, including nearly 90% of TNBCs163,164. The phase I/II trial IMMU-132-01 showed promising results in pretreated TNBC patients, with PFS and OS of 5.5 and 13 months, respectively165. On these bases, FDA grants accelerated approval to sacituzumab govitecan-hziy for metastatic TNBC treatment. Furthermore, the phase III trial ASCENT, which tested sacituzumab-govitecan-hziy against the investigators’ choice in third or further line, was recently stopped for the fulfillment of the study endpoints166. Another transmembrane glycoprotein, GPNMB, has been proposed as surface antigen for ADC, being enriched in ∼30% of TNBCs167. Glembatumumab-vedotin is an ADC (carrying the auristatin-derivate monomethyl auristatin E) directed toward GPNMB. In clinical studies, this ADC failed to improve the ORR in the overall population expressing the target in ≥5% and ≥25% of cells, in two independent trials (EMERGE and METRIC), suggesting that the mere expression of the target could not be sufficient to elicit effective and durable responses168,169. Furthermore, ladiratuzumab-vedotin, an ADC against the membrane zinc transporter protein LIV-1, is under investigation in several clinical trials (Table 1). Preliminary results have been observed with the combination of ladiratuzumab-vedotin and pembrolizumab in heavily pretreated TNBC patients, with 54% of ORR170.

Lately, the implementation of novel ADCs targeting HER2 provided encouraging results even in BC population with low levels of HER2 expression and no detectable ERBB2 amplifications, potentially defining a new role for HER2 also in TNBC. Trastuzumab-deruxtecan is an ADC carrying a topoisomerase I inhibitor payload that has been tested across several tumor types with varying levels of IHC HER2 expression. Recent data reported from a phase Ib trial showed an interesting activity of trastuzumab-deruxtecan in HER2-low tumors, though only a minority (13%) was TNBC. In the overall population, the study reported an ORR of 37.0% and mPFS of 11.7 months171, establishing HER2-low as a potential biomarker of patient selection in clinical trials with anti-HER2 ADCs.

Mechanisms of resistance to standard therapies in TNBC

Resistance to chemotherapy

Chemotherapy currently represents the mainstay for TNBC treatment172. As aforementioned, molecular profiling can identify TNBC subtypes more likely to benefit from NAC21,22. However, TNBCs usually become resistant during treatments or can be intrinsically unresponsive to chemotherapy, with numerous possible mechanisms of chemoresistance.

One of the major mechanisms is mediated by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that causes the ATP-dependent efflux of various chemotherapy compounds across cellular membranes. Interestingly, a significantly higher expression or upregulation of multidrug-resistant protein-1 (ABCC1/MRP1), breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2/BCRP) and multidrug-resistant protein-8 (ABCC11/MRP8) was observed in TNBC173–176. Each of these confers resistance to different agents, with extensively overlap. Several strategies aiming to inhibit activity or expression of the ABC transporters are being studying to overcome chemoresistance, as the use of sulindac, PZ-39 and various TKIs combined with chemotherapy177–180. However, many issues still exist, including the need to inhibit multiple transporters and the unacceptable associated toxicities.

The chemoresistance observed in TNBC may also be due to the presence of cancer stem cells (CSCs), a tumor cell subpopulation with the ability of self-renewal following treatment, subsequently leading to tumor re-growth181. Although CSCs have been observed in all BC subtypes, TNBC resulted to be intrinsically enriched in CSCs182,183. Moreover, accumulation of chemo-resistant CSCs has been described in residual tumor after NAC184. CSC-associated chemoresistance may be due to several factors including their relatively low proliferation rate and the high expression of ABC transporters185. Different therapeutic strategies to overcome CSCs chemoresistance are under evaluation, including targeting of CSC surface antigens and signaling pathways crucial for CSC self-renewal181.

Hypoxia is another described mechanism promoting tumor growth, survival, and therapy resistance186. Hypoxia alters TME and compromises uptake and/or activity of many cytotoxic agents, and confers resistance to radiation therapy. Moreover, hypoxia induces breast CSCs phenotype and promotes immunosuppression187,188. TNBC subtype is usually associated to high levels of hypoxia189. Use of hypoxia-activated prodrugs acting as cytotoxins190 or inhibition of molecular targets critical for hypoxia processes, including hypoxia-inducible factor inhibitors191,192, may potentially target hypoxia.

TP53 mutations, present in >50% of TNBC28–32, can also determine resistance to chemotherapy, especially platinum compounds193. As demonstrated in preclinical models, loss of p53 function promotes tolerance to platinum-induced DNA interstrand cross-links and double-strand breaks via G1 checkpoint abrogation and subsequent activation of alternative DNA-repair pathways that allows cancer cell survival194. The impact of TP53 mutation on response to specific chemotherapeutics is not well established in TNBC195,196, deserving further investigation. Furthermore, TNBC is encompassed by a complex network of different signaling pathways, including nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT, that promote TNBC progression and chemoresistance4. NF-kB is frequently upregulated in TNBC, while attempts to inhibit this pathway provided only modest results due to high toxicity197,198. PAM pathway is also frequently hyperactivated in TNBC, mainly due to PTEN loss, and is associated with poor prognosis and chemoresistance199,200. Similarly, abnormal JAK/STAT signaling is frequently observed in TNBC and a crosstalk between STAT3 and upregulation of ABC transporters have been observed28,33. However, the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib did not demonstrate compelling efficacy as single-agent in a phase II trial201, corroborating the concept that inhibition of a single pathway is poorly effective in TNBC. Other clinical trials testing specific inhibitors of the JAK/STAT pathway are currently ongoing. Lastly, EGFR and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) pathways are also implicated in TNBC chemoresistance202–204. Despite EGFR and IGF-1R overexpression in ∼40% of TNBCs205,206, disappointing results in clinical trials targeting these pathways have been obtained so far76–81,206,207.

Resistance to PARP inhibitors

Likewise other targeted therapies, acquired resistance to PARPis might develop over time through multiple different mechanisms208. One of the most well described is the restoration of sufficient HRR despite PARP inhibition, as in the case of secondary “revertant” mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2209–212. Restoration of BRCA1 or BRCA2 protein functionality may occur by genetic events that may restore the open reading frame, thus leading to a functional protein, or by genetic reversion of the inherited mutation that may restore the wild-type protein. These events frequently determine resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy and PARPis213. Moreover, HRR may also be restored by loss of BRCA1 promoter methylation, leading to expression of BRCA1 gene similar to the one of HR-proficient tumors. Probably, this is due to a positive selection of tumor cells clones with lower promoter methylation208.

The ability to protect the stalled replication fork, despite HR defects, may represent another resistance mechanism214. Upregulation of the ATR/CHK1 pathway has been observed with the subsequent phosphorylation of multiple proteins contributing to fork stability215. Fork protection may also be obtained by reducing recruitment of the nucleases to the stalled replication fork, especially through the downregulation of the activity of different proteins, as PTIP and EZH2, responsible for nucleases recruitment. As a result, tumor cells may achieve resistance to PARPis without restoring HR215. Furthermore, since PARPi activity is mediated by the inhibition of PARP enzymes, another possible mechanism of resistance is represented by the decreased expression of these proteins216. Moreover, mutations of PARP1 and other proteins involved in DNA repair may be responsible for primary and secondary resistance to PARPis, respectively217. In addition, specific mutations of the BRCA1 and 2 genes, especially missense mutations that disrupts the N-terminal domain of BRCA1, may favor rapid resistance to PARPis. Mutation in the BRCA C terminal domain may generate protein products unable to fold properly, thus being more subject to protease-mediated degradation. Heat shock protein-90 (HSP90) stabilizes these mutant BRCA1 proteins that can in turn efficiently interact with PALB2-BRCA2-RAD51 complex, conferring PARPis and cisplatin resistance218. In this case, treatment with an HSP90 inhibitor may potentially restore cancer cell sensitivity to PARP inhibition.

Lastly, mutations in genes encoding for shieldin subunit complex219,220 and loss of REV7221 can cause resistance to PARPis in BRCA1-deficient cells, owing to restoration of HRR. Of note, some of these alterations in BRCA-deficient tumors confer sensitivity to platinum compounds, suggesting that the underlying mechanism of resistance could influence the TNBC therapeutic algorithm. Alternative treatment strategies that may revert or delay the emergence of resistant clones, including combining PARPis with other agents or targeting alternative molecules involved in DNA-damage response (ATR, ATM, WEE1), as well as the identification of the individual mechanism of resistance are required to identify potential therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance. Since some of these mechanisms may provide resistance also to other drugs, therapies given prior to and after PARPis should be carefully selected.

Resistance to immunotherapy

Primary and acquired resistance to ICIs have been observed in several patients. Understanding the multifactorial mechanisms of resistance to ICIs should go in parallel with the identification of reproducible and reliable biomarkers that may predict the likelihood and extent of response222.

Defective tumor immunorecognition may impair not only physiologic but also therapy-stimulated immunosurveillance. Indeed, an altered/insufficient antigen presentation or a limited neoantigen repertoire may contribute to dampen immune responses. Moreover, abundance and activation of CD8-postive T cells is key. Several strategies investigating the possible combination of multiple DNA damaging agents (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) or agents targeting DNA repair (PARP and ATR inhibitors) are being studied223. These agents can promote the release of neoantigens within the TME enhancing immunogenicity of the tumor and T-cell infiltration.

TME composition in influencing response to ICIs has been extensively studied, ranging from “immune-inflamed” to “immune-desert” phenotypes224. As aforementioned, high levels of TILs have been associated with better prognosis and promising response to immunotherapy in TNBC123–126,159. However, different subpopulations of T cells may have a different significance225–227. Regulatory T cells (CD4+/CD25high/FoxP3+) may promote tumor growth while inhibiting activity of cytotoxic CD8-positive T cells through direct cell-cell contact and/or secretion of transforming growth factor-β. The role of B lymphocytes is still not clear; activated B cells may participate in anti-tumor immune response through different mechanisms, including secretion of antigen-specific antibodies, induction of innate immune cells (e.g., M1 tumor-associated macrophages), release of different cytokines (e.g., IL-6) and activation of complement cascades. Recently, Kim et al. 228 classified TNBC in two “subtypes” according to neutrophils and macrophages infiltration, each with its own regulation pathways: neutrophil-enriched (NES), characterized by immunosuppressive neutrophils resistant to ICI, and macrophage-enriched subtype (MES) containing predominantly CCR2-dependent macrophages and exhibiting variable responses to ICI. Authors postulated that a MES-to-NES conversion may mediate acquired ICB resistance228. Furthermore, angiogenesis plays a crucial role in the formation of spatially-limited “immunoresistant niches”, difficult to reach by immune cells. The use of anti-angiogenic therapies may promote vascular normalization, improve lymphocyte trafficking across the endothelium and reverse immunotherapy resistance229.

Recent research has been focused on enteric microbiome as a potential factor influencing immunotherapy efficacy230. However, the impact of gut bacteria on response or resistance to ICIs in BC has not been elucidated yet. Potential strategies to manipulate gut microbiota are still under investigation to enhance anticancer therapy efficacy. Lastly, PTEN alterations have been found to be associated with reduced survival in TNBC patients treated with anti-PD-1/L1 ICIs147. As PAM pathway inhibition can revert the T-cell-mediated resistance231, a phase I trial is investigating the combination of ipatasertib, atezolizumab and paclitaxel in TNBC patients with promising antitumor activity (ORR 73%), regardless of PD-L1 expression and PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN status232.

Conclusions and future perspectives

TNBC is a heterogeneous disease that encompasses different histological and molecular subtypes with distinct outcomes. Each subtype is defined by specific transcriptomic and genetic alterations, which can be potentially targeted. However, only a small proportion of TNBC patients is actually treated with biomarker-driven therapies, as PARPis or platinum agents in germline BRCA1/2 carriers and ICIs in PD-L1-positive TNBCs. Therefore, chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for the largest part of patients. GEP allows to identify TNBC subtypes with distinct responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, supporting the implementation of standard and new therapies in selected TNBC subgroups. Not all TNBCs have a bad prognosis and, thus, risk stratification is necessary for tailoring escalation/de-escalation of therapies. Accordingly, recognizing histological and molecular heterogeneity of TNBC is essential to tailor treatment on individual basis to maximize the clinical benefit. However, several challenges have to be addressed.

The low frequency of highly recurrently mutated genes and potentially actionable alterations represent a relevant issue for the development of new therapeutic strategies. Whole-genome sequencing technologies can expand the number of patients amenable to targeted therapies, as hypothesized for patients with large-scale state transition-high or somatic biallelic loss-of-function in HR-related genes31,233,234. Furthermore, metastatic TNBC seems to display great heterogeneity and genetic complexity as compared to early stage31. Such observation suggests that tailored treatments should be implemented in the early setting to prevent the onset of complex and redundant mechanisms of resistance. In addition, multiple alterations can affect the same pathway at same time. For instance, TNBCs carrying PIK3CA activating mutations can concomitantly present PTEN loss thus not benefiting from PIK3CA-selective inhibition, as demonstrated in ER-positive BC235,236. Furthermore, new methodologies, such as liquid biopsy-based assays capable to identify tumors at very early stages and to monitor minimal residual disease, would allow to better predict outcomes during the disease course. Accordingly, new drugs could potentially be placed when disease is less complex biologically, identifying patients with breast cancer who need experimental therapy early in the disease course and for which fast-track drug approval is required.

The immune TME in TNBC considerably influences the risk of relapse and response to chemotherapy, providing the rationale for the application of ICI-based therapies. However, controversial results with immunotherapy in TNBC have been reported so far. Therefore, refinement of biomarker-selected TNBC population more likely to derive benefit from immunotherapy-based therapies represents the issue of several ongoing researches. The abovementioned biomarkers should not be interpreted as interchangeable, but complementary, since each one describes a feature of the complex cancer–immune interplay. In this way, a better definition of a TNBC “immunogram” is essential to properly select patients for immunotherapy-based treatments and, concomitantly, implement innovative strategies to enhance immunogenicity in “immune-excluded” cancers through combinatorial approaches.

In conclusion, TNBC is solely an operational term, considering the marked histopathological, transcriptomic and genomic heterogeneity that encompasses this BC subtype. The application of multi-omics technologies and biocomputational algorithms as well as novel clinical trial designs are strongly warranted to expand the therapeutic armamentarium against TNBC and pave the way towards personalized anticancer treatments.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with Ricerca Corrente and 5×1000 funds.

Author contributions

A.M., C.C., and G.C. conceived the work. Each author wrote a section of the manuscript. A.M. and C.C. drafted the manuscript. A.M. designed and finalized graphics. G.C. supervised the work. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Source data for all tables are provided in the paper. Figures was generated by reanalysis of publicly available studies and open-source platforms using RStudio (version 1.1.463). No new datasets have been generated or analyzed for this article.

Competing interests

C.C. received speakers’ bureau and consultancy/advisory role from Lilly, Roche Novartis, and Pfizer. G.C. reports personal fees for consulting, advisory role and speakers’ bureau from Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, Lilly, Foundation Medicine, Samsung, and Daichii-Sankyo; honoraria from Ellipses Pharma; fees for travel and accommodations from Roche/Genentech, and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Basal-like breast cancer: a critical review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2568–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrido-Castro AC, Lin NU, Polyak K. Insights into molecular classifications of triple-negative breast cancer: improving patient selection for treatment. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:176–198. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertucci F, et al. How basal are triple-negative breast cancers? Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:236–240. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker JS, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Ronde JJ, et al. Concordance of clinical and molecular breast cancer subtyping in the context of preoperative chemotherapy response. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;119:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastien RR, et al. PAM50 breast cancer subtyping by RT-qPCR and concordance with standard clinical molecular markers. BMC Med Genom. 2012;5:44. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prat A, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fougner C, Bergholtz H, Norum JH, Sorlie T. Re-definition of claudin-low as a breast cancer phenotype. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1787. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulford LG, et al. Specific morphological features predictive for the basal phenotype in grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Histopathology. 2006;49:22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livasy CA, et al. Phenotypic evaluation of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2006;19:264–271. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner NC, et al. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreike B, et al. Gene expression profiling and histopathological characterization of triple-negative/basal-like breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R65. doi: 10.1186/bcr1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorlie T, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorlie T, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geyer FC, et al. The spectrum of triple-negative breast disease: high- and low-grade lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 2017;187:2139–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lae M, et al. Secretory breast carcinomas with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene belong to the basal-like carcinoma spectrum. Mod. Pathol. 2009;22:291–298. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson M, et al. Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and neck. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18740–18744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909114106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmann BD, et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2750–2767. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masuda H, et al. Differential response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among 7 triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:5533–5540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehmann BD, et al. Refinement of triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes: implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burstein MD, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies novel subtypes and targets of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:1688–1698. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis C, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang YZ, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic landscape of triple-negative breast cancers: subtypes and treatment strategies. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaayvaz M, et al. Unravelling subclonal heterogeneity and aggressive disease states in TNBC through single-cell RNA-seq. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3588. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, et al. Chemoresistance evolution in triple-negative breast cancer delineated by single-cell sequencing. Cell. 2018;173:879–893. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cancer Genome Atlas, N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kandoth C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertucci F, et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic breast cancers. Nature. 2019;569:560–564. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah SP, et al. The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple-negative breast cancers. Nature. 2012;486:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balko JM, et al. Molecular profiling of the residual disease of triple-negative breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies actionable therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:232–245. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bareche Y, et al. Unravelling triple-negative breast cancer molecular heterogeneity using an integrative multiomic analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:895–902. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tseng LM, et al. A comparison of the molecular subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer among non-Asian and Taiwanese women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;163:241–254. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4195-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149:979–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandrov LB, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexandrov LB, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swanton C, McGranahan N, Starrett GJ, Harris RS. APOBEC enzymes: mutagenic fuel for cancer evolution and heterogeneity. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:704–712. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris RS. Molecular mechanism and clinical impact of APOBEC3B-catalyzed mutagenesis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0498-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shang M, et al. Potential management of circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Cancer. 2018;9:4627–4634. doi: 10.7150/jca.28458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan JCM, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:223–238. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Murillas I, et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:302ra133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olsson E, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015;7:1034–1047. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radovich M, et al. Association of circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with disease recurrence in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: preplanned secondary analysis of the BRE12-158 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1410–1415. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeshita T, et al. Prognostic role of PIK3CA mutations of cell-free DNA in early-stage triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1582–1589. doi: 10.1111/cas.12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madic J, et al. Circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells in metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:2158–2165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stover DG, et al. Association of cell-free DNA tumor fraction and somatic copy number alterations with survival in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:543–553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilborn E, et al. Androgen receptor expression predicts beneficial tamoxifen response in oestrogen receptor-alpha-negative breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2016;114:248–255. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu M, et al. Prognostic significance of androgen receptor expression in triple negative breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2020;20:e385–e396. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Zazzo E, et al. Prostate cancer stem cells: the role of androgen and estrogen receptors. Oncotarget. 2016;7:193–208. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]