Abstract

Objective

To describe the perspectives on life participation by young adults with childhood-onset chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design

Semi-structured interviews; thematic analysis.

Setting

Multiple centres across six countries (Australia, Canada, India, UK, USA and New Zealand).

Participants

Thirty young adults aged 18 to 35 years diagnosed with CKD during childhood.

Results

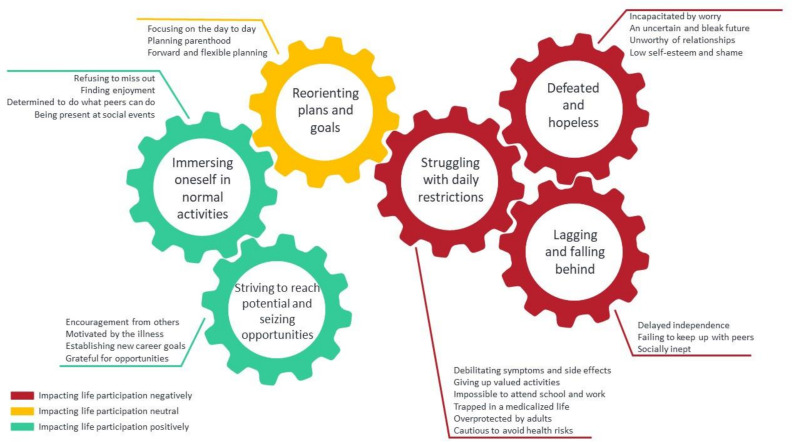

We identified six themes: struggling with daily restrictions (debilitating symptoms and side effects, giving up valued activities, impossible to attend school and work, trapped in a medicalised life, overprotected by adults and cautious to avoid health risks); lagging and falling behind (delayed independence, failing to keep up with peers and socially inept); defeated and hopeless (incapacitated by worry, an uncertain and bleak future, unworthy of relationships and low self-esteem and shame); reorienting plans and goals (focussing on the day-to-day, planning parenthood and forward and flexible planning); immersing oneself in normal activities (refusing to miss out, finding enjoyment, determined to do what peers do and being present at social events); and striving to reach potential and seizing opportunities (encouragement from others, motivated by the illness, establishing new career goals and grateful for opportunities).

Conclusions

Young adults encounter lifestyle limitations and missed school and social opportunities as a consequence of developing CKD during childhood and as a consequence lack confidence and social skills, are uncertain of the future, and feel vulnerable. Some re-adjust their goals and become more determined to participate in ‘normal’ activities to avoid missing out. Strategies are needed to improve life participation in young adult ‘graduates’ of childhood CKD and thereby strengthen their mental and social well-being and enhance their overall health.

Keywords: chronic renal failure, dialysis, renal transplantation, paediatric nephrology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with young adults aged 18 to 35 years diagnosed with chronic kidney disease during childhood, who were purposively sampled across six countries to obtain in-depth and diverse data on their perspectives on life participation.

We conducted interviews until data saturation.

Participants were all interviewed in English language and most participants were from high-income countries, therefore the transferability of the findings to other populations and settings is uncertain.

Few participants were receiving dialysis at the time of the study though most of the participants had been on dialysis previously and discussed their past experiences.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in children is associated with increased mortality and may lead to impaired physical, social and cognitive functioning.1–6 These challenges undermine the ability of children with CKD to achieve developmental milestones, autonomy and independence, which can in turn limit successful participation in society during adulthood.7–9 Young adults with childhood-onset of CKD have reported difficulties and delays in attaining educational, vocational and relationship goals, and are less likely to be employed than the age-matched general population.10 11

Through a global consensus process that involved over 700 patients, caregivers and health professionals from more than 70 countries, the Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology–Children and Adolescents (SONG-Kids) initiative established life participation as the most important patient-reported outcome for children with CKD.12–14 Where quality of life is defined as an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.15 The concept of life participation is more specific and is defined as the ability to participate in meaningful activities that provide a sense of fulfilment, enjoyment, control and hope.16 For children with CKD, meaningful activities include study, sport, social and leisure activities.17 18 Life participation is often restricted by the symptoms, side effects and treatment burden associated with CKD, and this has long-term consequences in young adulthood.7 8 19 20

There is increasing recognition of the need to address the ability to participate in life,10 20 as this may also impact on motivation for self-management, coping and treatment satisfaction. However, little is known about patients’ perspectives on the meaning and impact of childhood CKD on ‘life participation’. The aim of this study was to describe the perspectives of young adults with childhood-onset CKD on life participation, to inform interventions and clinical care and ultimately to improve health outcomes for patients with CKD.

Methods

We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ) to report this study21 (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2020-037840supp001.pdf (25.7KB, pdf)

Participant selection and setting

Participants were eligible to participate if they were English-speaking, aged from 18 to 35 years old and diagnosed with CKD prior to the age of 18 years. We included any cause of kidney disease and treatment stage of CKD (CKD Stage 1 to 5 (not receiving kidney replacement therapy), dialysis or transplant). Those determined to be medically unsuitable by their clinician were excluded. Participants were recruited through the SONG network using standardised invitation emails and by clinicians from centres across Australia, Canada, India, UK and USA. Ethics approval was obtained from all participating sites listed in online supplemental file 2. We applied a purposive sampling strategy to ensure a diverse range of demographic and clinical characteristics.

bmjopen-2020-037840supp002.pdf (40.4KB, pdf)

Data collection

The interview guide was developed based on the literature on life participation and discussion among the research team14 22 (online supplemental file 3). The questions focussed on the meaning and impact of childhood CKD on life participation during childhood and in young adulthood. From September to November 2019 author JK (a female medical student, who completed training in qualitative research) conducted one semi-structured interview with each participant face-to-face at a venue as preferred by the participant, or by video conference using zoom. There were no prior relationships established between JK and the participants. We conducted interviews until we reached data saturation, that is, when no new concepts on life participation were raised after three consecutive interviews. All the interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed. No fieldnotes were taken.

bmjopen-2020-037840supp003.pdf (32.3KB, pdf)

Data analysis

The transcripts were imported into HyperRESEARCH (V.4.0.3) software. Using thematic analysis, JK coded line-by-line all meaningful segments of text in the transcripts to inductively identify concepts, which were grouped into initial themes and subthemes. We identified patterns and links among themes to develop a thematic schema. To ensure the themes captured the breadth and depth of the data, these were discussed with EH, CH and AT, who also read the transcripts, and participants were emailed a copy of the preliminary findings and invited to provide comments. Any additional perspectives received were integrated into the final analysis.

Patient and public involvement

The topic of life participant was identified by patient as a critically important outcome through the global Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology–Children and Adolescents (SONG-Kids) Initiative.12 17 18 Patients were directly involved in the study as participants in the interviews. Author CG is a caregiver and also a member of the SONG-Kids Steering Committee who was involved in the planning and design of the study. She advised on the study protocol including the data collection (eg, interview guide), and was involved in the interpretation of the data. Patients were not involved in the recruitment and were not involved in conducting the interviews. Participants were emailed a copy of the preliminary findings and invited to provide comments. Any additional perspectives received were integrated into the final analysis.

Results

Study participants

Overall, 30 young adults from Australia (n=16), Canada (n=5), India (n=4), UK (n=3), USA (n=1) and New Zealand (n=1) were included. They were between 18 to 32 years of age (mean 23.4 years, SD 4.0), and 20 (67%) were women. Non-participation (3) was due to refusal, illness or inability to schedule an interview after three attempts. The participant characteristics are shown in table 1. The average age at diagnosis was 7.7 years (SD 5.3). Seven (23%) participants were not receiving kidney replacement therapy, two (7%) were receiving dialysis and 21 (70%) had a kidney transplant. The average duration of the interview was 53 min, with 14 interviews (47%) were conducted face-to-face. A parent was present in five interviews (17%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | N (%) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 10 (33) |

| Women | 20 (67) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 18 to 21 | 12 (40) |

| 22 to 25 | 9 (30) |

| 26 to 30 | 7 (23) |

| 31 to 35 | 2 (7) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 16 (55) |

| Canada | 5 (17) |

| India | 4 (13) |

| UK | 3 (10) |

| USA | 1 (3) |

| New Zealand | 1 (3) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Primary school | 1 (3) |

| Secondary school, grade 10 | 4 (13) |

| Secondary school, grade 12 | 6 (20) |

| Tertiary, certificate/diploma | 4 (13) |

| Tertiary, undergraduate/bachelor | 13 (43) |

| Tertiary, postgraduate/masters/PhD | 2 (7) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 6 (20) |

| Part-time or casual | 7 (23) |

| Student | 13 (43) |

| Voluntary work | 1 (3) |

| Not employed | 4 (13) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 4 (13) |

| Partner (living together) | 4 (13) |

| Partner (not living) | 4 (13) |

| Divorced/separated | 0 (0) |

| Single | 18 (60) |

| Living with | |

| Parents/family | 19 (63) |

| Housemates | 2 (7) |

| Partner | 7 (23) |

| By themselves | 2 (7) |

| No. of children | |

| 0 | 28 (93) |

| 1 | 2 (7) |

| Age at CKD diagnoses (years) | |

| Prenatal or at birth | 2 (7) |

| 0 to 5 | 7 (23) |

| 6 to 10 | 9 (30) |

| 11 to 15 | 8 (27) |

| 16+ | 4 (13) |

| CKD diagnosis or cause | |

| Congenital abnormalities of kidney/urinary tract | 7 (23) |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 4 (13) |

| Nephrotic syndrome (cause not specified) | 3 (10) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 (10) |

| Haemolytic uraemic syndrome | 2 (7) |

| Lupus nephritis | 2 (7) |

| Reflux nephropathy | 2 (7) |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 1 (3) |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | 1 (3) |

| Diabetic | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

| Other | 3 (10) |

| Current CKD treatment stage | |

| Not on kidney replacement therapy | 7 (23) |

| 5D, haemodialysis | 2 (7) |

| 5D, peritoneal dialysis | 0 (0) |

| 5T, deceased donor kidney transplant | 13 (43) |

| 5T, living donor kidney transplant | 8 (27) |

| Treatment during childhood* | |

| No kidney replacement therapy | 15 |

| Haemodialysis | 8 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 8 |

| Transplant | 13 |

N=30. Percentage may not total 100 due to rounding.

*May not add up, because of possible multiple answers per person.

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Themes

We identified six major themes: struggling with daily restrictions, lagging and falling behind, defeated and hopeless, reorienting plans and goals, immersing oneself in normal activities and striving to reach potential and seizing opportunities. Each theme is expounded by subthemes.

Young adults who grew up with CKD struggled with daily restrictions, felt defeated and hopeless and lagging behind in their studies and other life goals. They had to give up valued activities, lacked confidence and social skills, were uncertain of the future and felt vulnerable. Some had to reorient their plans and goals. Some participants initially struggled with this then overcame these struggles and re-adjusted their goals. They immersed themselves in ‘normal’ activities, refusing to miss out and were determined to do what their peers could do. Some strived to reach potential and seize opportunities. Figure 1 depicts how the themes relate to each other. Selected quotations to support each theme are provided in table 2.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema.

Table 2.

Selected participant quotations for each theme

| Theme | Quotations |

| Struggling with daily restrictions | |

| Debilitating symptoms and side effects | I'd wake up and be totally fine and then by 3 o'clock in the afternoon, I couldn't walk because my ankles and my knees were so swollen with water. (F, 22–25) |

| It was limiting in a lot of ways. I got sick a lot, with infections and colds. It seemed like everything knocked me down. And then I would deal with the HSP* rash and then I had nephrotic syndrome and I actually went through chemo to treat the nephrotic syndrome, which caused me to drop out of college and it, it impacted my academics a lot and a lot of the things that I got to do.(F, 18–21,) | |

| The medications, they are really strong. They affect your memory, they affect your body, they affect you in every way. (F, 31–35) | |

| Giving up valued activities | I did a lot of sports in my early teens. I did competitive swimming, football and rugby and I had to stop. I was devastated. (F, 18–21) |

| What I wanted then was just to feel better so that I could go to school. I loved school. I've always been quite academic. I hated not being there. I hated that, I wasn't well enough to go to my dance school and I pretty much gave up dancing. (F, 22–25) | |

| My friends went to Europe, I couldn’t go. Travel’s probably the main thing. That was quite hard. (F, 26–30) | |

| Impossible to attend school and work | I was physically uncomfortable, because of tubes sticking out of my stomach and chest. I just wanted to be home all the time. (F, 31–35) |

| I'm juggling school, it’s just a big juggling act at the moment. And even then, I'm still struggling cause sometimes I can't make it to school. Not because of my mental state. Just because I'm so tired. (M, 18–21) | |

| Trapped in a medicalised life | Back then I had a lot of restrictions. I had catheters, Hickman lines and was fed via a peg tube (F, 26–30) |

| Before, I was doing home haemodialysis, I thought my life was ending because I had to be stuck with this machine, three times a week for hours. (F, 26–30) | |

| It’s three times a week, 5 or 6 hours each day. It’s just ridiculous. So much time. And then when you get off, you feel so drained and I couldn't really socialise much and everything. (F, 22–25) | |

| I kept going back and staying in hospital. For me that was a bit like escaping from the real world I guess. I guess you just get a bit institutionalised. (F, 22–25) | |

| Overprotected by adults | I was able to, but my parents didn’t let me go outside. They said: you should stay home and rest. (M, 18–21) I've talked to Dr. X about it, and he’s like ‘no,’ because his other |

| Patients have gotten really sick, so that adds to my anxiety. I mean he’s telling me not to go (travel to Asia). (F, 26–30) | |

| After the transplant they told me ‘maybe you shouldn’t play netball because you could hit the kidney’. What some doctors tell you keeps you in a bubble if you follow it, I guess. (F, 18–21) | |

| Cautious to avoid health risks | I'd absolutely love to go to Egypt. But they recommend live vaccines. I can’t have that. And it’s definitely not worth having the vaccine and getting ill from it. (F, 22–25) |

| Always when I do something, there’s a list that I go through in my head; how is this going to affect me and if it’s going to be bad or positive or how it’s going to affect my kidneys. (F, 18–21) | |

| I cannot go out drinking with friends or I can go and I'm the only one sitting with no drink, it feels stupid. (F, 22–25) | |

| Lagging and falling behind | |

| Delayed independence | I missed out on a proper education. I feel like I've missed 3 years of my life, I feel like a 17-year-old stuck in a 19-year-old body. I feel like I'm too old for who I really am. I just feel like I'm not quite smart enough at the moment to be almost 20 years old. (M, 18–21) I’d like to move out, but if anything serious happens and I can’t work, I can’t pay for the place anymore. (M, 22–25) I think financially is mostly where it’s been an issue. I feel like I'm dependent on either the government or my dad or even my fiancé sometimes, because I don't have the same education. I don't have a degree in order for me to get a good job. (F, 22–25) |

| Failing to keep up with peers | All my friends would go out after school and play out and all that kind of thing. I was never able to do that because I just didn't feel well enough. (F, 22–25) |

| My friends are already graduated and at work and they look like they have a goal and I don't even know what I want and I'm already 25. (F, 22–25) | |

| I would always play hide and seek instead of tag because I didn't want people to make fun of me for not being able to run properly. (F, 22–25) | |

| Socially inept | I'll exclude myself in situations where I can't do something or didn’t feel comfortable. (M, 22–25) |

| I kind of withdrew from a lot of my friends. I think that I missed out on some social skills. Socially I feel kind of impeded. (F, 22–25) I used to be sad too. I'd really kind of avoided hanging around with kids. (F, 22–25) I feel a bit socially awkward, I don’t know if it’s because of my lack of social interactions when I younger. (M, 22–25) | |

| Defeated and hopeless | |

| Incapacitated by worry | Because when you have kidney disease, it just feels like you're a prisoner versus normal. (F, 26–30) |

| Oh my gosh, I'm nearly halfway (estimated graft survival). And you know that there’s no say in that it’s only 20 years or that it is definitely 20 years. It could be more, it could be less. You just don't know. But at that time it just got in my head that I was almost halfway (about the transplant). (F, 18–21) | |

| And then if your kidney was to fail then what? If you are a young mum and you have kids and everything. You can't afford to be in hospital again. (F, 22–25) | |

| An uncertain and bleak future | I understand that my life participation is going to decline and that I won't be able to do things and I'm going to have to compromise. (F, 18–21) |

| I think you can only have a couple of transplants because of the medication and because of the antibodies and all that kind of stuff. And each transplant works for like 10 years. I mean, you can do the counting. (F, 18–21) | |

| I'll probably say Brexit is one of them. We don't know what’s going to happen. Cause I probably will be doing home dialysis and the supplies are all from European countries. (M, 26–30) | |

| Unworthy of relationships | I'm not in a relationship now. I had to like consider it with a guy and that’s when it comes up. I feel like I don't want to burden people. (F, 26–30) |

| You put yourself down and you start thinking, would anyone ever love me because I have those problems. (F, 22–25) | |

| It’s a little bit hard to be friends with somebody who’s a sick kid, which is though to say, but I think it is harder to have a friend who’s sick. (F, 18–21) | |

| Low self-esteem and shame | I have been on prednisone for 6 years now, so I have a moon face and it’s caused me to gain weight. I was a lot skinnier before, I had a lot better self-image. It’s been really impactful. (F, 18–21) |

| It was hard at school because obviously I looked different. I had tubes sticking out of my stomach. I had to be careful how I sat, I had to be careful around other kids. Kids had no idea what it was. They'd make fun of you. (F, 26–30) | |

| I used to see girls of my age getting complimented by guys and the guys actually wanted to go out with them. So I used to feel really bad about that. (F, 22–25) | |

| I think I am kind of a self-conscious person as well. So the symptoms of the prednisolone and the face blowing up and all that was a big issue for me. I was always conscious about that and the kids bullying and stuff like that. That was hard. (F, 22–25) | |

| Reorienting plans and goals | |

| Focussing on the day to day | Whenever I plan a future, it doesn't happen. Just planning short-term. I'll be planning what I have to do in the evening and what I have to do tomorrow. (F, 22–25) |

| I've definitely learnt to just kind of take every day as it comes and just see what happens. (F, 22–25) | |

| I feel like the transition from being in hospital for so long and coming out, it was really hard. In the hospital you had stress as well, but you're only stressed about; Oh, am I getting dialysis today? Am I going to cramp really bad today? While now, I suddenly have to think about other stuff. (F, 22–25) | |

| Planning parenthood | Getting my eggs harvested so that, when I decide if I want children I can select ones without the PKD*. (F, 18–21) |

| I had to change medications because it causes birth defects. So I had to do that and I just have these worries. Like what if I start to lose my kidney during pregnancy? Do I have to get back on dialysis? Is my child going to be okay? Am I going to pass anything down to my child? And that’s if I can get pregnant. (F, 31–35) | |

| Being a father, I found out I have to stop my mycophenolate for 3 months and then I have to do IVF* now. (M, 22–25) We were told we had to have kids soon. So from not really hearing that before to hearing that straight away, we were quite a bit shocked. (F, 26–30) | |

| Forward and flexible planning | I do find myself thinking, it would be beneficial to find something where if I have to go part-time, I can still afford to live. I'll probably have to go part-time at some point to accommodate dialysis. (F, 22–25) |

| I didn't drink yesterday and I haven't drunk today just so I could drink this warm chocolate. (M, 18–21) | |

| Before the diagnosis I was really into track and after the diagnosis I was into rowing because I could sit down and do it. (F, 18–21) | |

| Immersing oneself in normal activities | |

| Refusing to miss out | I didn't see myself as unable to do things that they could. (F, 18–21) |

| I still tried to do the things I wanted to do, while still being on haemodialysis. It didn't stop me from what I wanted to do. (F, 26–30) | |

| We did five-a-side football, which I was able to do because they made like a special shield that went over the kidney. (M, 26–30) | |

| Finding enjoyment | My experience is a lot of friends come and see me, support me. And you know, we play cards during dialysis as well. (F, 22–25) |

| I feel like there’s a sense in me that just wants to keep having fun. I think when getting dialysis, I couldn’t have fun, I couldn’t really enjoy my life as much. My participation in life was really low. So, I don’t know why, but there is just an urge, I just want to keep having fun now that I can. (F, 26–30) | |

| I suppose getting a hobby, like for me, I play games and I also go to the gym. I suppose just doing things that make you feel good about yourself. (M, 22–25) | |

| I just enjoy it because I've seen the worst parts of life, now I'm enjoying the best. (M, 22–25) | |

| Determined to do what peers can do | And I think just being able to do the things that your friends do. I think that’s, as a child, that was all I wanted. All I wanted was just to be in quotations ‘normal’. And to be able to do everything that everybody else did. (F, 22–25) |

| You want to be able to participate in the way your peers are participating, like people your age, without having to make adjustments. So, you don't feel different or left out. (F, 31–35) | |

| Being present at social events | If you are able to handle it, you should go party with your friends. Because why not? You don't have to do everything your friends are doing, you don't have to smoke or drink. (F, 18–21) |

| I suppose just getting out there and doing things. Like if a friend invites me to go see a movie or get lunch, I just do it. (M, 22–25) | |

| I still go to a lot of activities and stuff like that. I don't let that stop me. I went on a lot of dates, met people. (F, 22–25) | |

| Striving to reach potential and seizing opportunities | |

| Encouragement from others | My parents always made sure that my education didn't get affected because of it. I used to get hospitalised a lot, so my mother used to teach me in hospital. I used to do my homework there. (F, 22–25) |

| I joined a Facebook group with patients from all over the world. They participated in this year’s world transplant games and really encouraged us. (M, 18–21) | |

| My family, friends and faith, 3 times F, gave me the confidence to try new things, get back on my feet again, do the things I want to do. (F, 26–30) | |

| Motivated by the illness | There’s a difference now where I'm no longer using it as an excuse to not do things, but as an excuse to do things. I’m making it a reason to do things. (F, 18–21) |

| I recently started a health blog on Instagram and I'm starting a YouTube channel. (F, 22–25) | |

| I try to do my best to give them (children with CKD) advice or just try to be there for them, because I didn't have that when I was transitioning (to adult care). I'm there for the new generation, help them cope, be that inspiration. (F, 22–25) Doing the best I can to keep fit and well. Going to the gym twice a week. (M, 22–25) | |

| Establishing new career goals | Maybe that sickness will give me strength. And it will help me if I work as a nurse. (F, 18–21) |

| If it wasn't for haemodialysis I wouldn't be where I am today. Like being an advocate, being working at the hospital, you know, getting that voice heard. (F, 26–30) | |

| I, for example, would not have started counselling. I wouldn't care so much about people. I wouldn't care so much about their mental health. Before kidney failure, I was into fashion. (F, 26–30) | |

| Grateful for opportunities | So I met up with him and we talked about our own experiences and now he has published a book as well. He’s a big star in Taiwan, I look up to him. (F, 22–25) |

| I'm competing in the world transplant games, I compete at the British games every year and next year I'm competing at my first European games. (M, 26–30) | |

| Got invited into lots of functions. Met lots of celebrities and sports stars. We're still friends with some of the people that are still on television. (F, 18–21) | |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; IVF, In vitro fertilisation; PKD, Polycystic kidney disease.

Struggling with daily restrictions

Debilitating symptoms and side effects

Symptoms and side effects such as infections, tiredness and pain limited the participants’ day-to-day activities. Fatigue made them ‘too tired to do anything’, and ‘unable to get up in the morning’. For some, swelling impaired their mobility—‘I couldn’t move because of my swollen ankles’. Specific side effects of immunosuppression, including weight gain, osteoporosis, hair growth and cognitive impairment restricted daily activities and prevented them from excelling (eg, sports) and caused some to drop out of college/university.

Giving up valued activities

Some felt forced to stop doing things they enjoyed, particularly sports including swimming, football and rugby—‘the (doctors) told me to quit the team’. They resented having to forgo activities they valued—‘I hated that I wasn't well enough to go to my dance school and I pretty much gave up dancing.’ Some had to refrain from foods they liked because of the dietary restrictions, or were disappointed about being unable to travel—‘I'd rather backpack, I'd rather go to a random country, but I can’t.’

Impossible to attend school and work

Attending school was ‘a big juggling act’, and some missed years of education. Being too tired, unwell and having to do dialysis or undergo surgery had prevented them from attending school. Some felt self-conscious and wanted to stay home—‘I was physically uncomfortable, because of tubes sticking out of my stomach and chest. I just wanted to be home all the time’. One participant was homeschooled for over a year because of the risk of infection. Some had to take time off work because of treatment.

Trapped in a medicalised life

The frequent and lengthy hospital appointments, dialysis regimen, surgeries and having to take medications consumed their childhood. They were not allowed to go to school camp or sleepovers because they had tubes and lines and needed to remain close to the hospital in case they needed medical attention—‘I am always going to have to be tied to the hospital because that’s my lifeline, for medications, blood tests, doctor appointments, checkups. It’s always going to be at the forefront of my life.’ For patients receiving dialysis, they were ‘stuck to the machine’. Some could not spend the night with their partner because they had to be home to do peritoneal dialysis. One participant mentioned that having multiple surgeries (‘20 surgeries in 21 months’) precluded them from educational and social activities. Some participants felt ‘left to their own devices’ after kidney transplant because they had been ‘institutionalised’ while on dialysis.

Overprotected by adults

Some believed that overprotectiveness by adults inhibited their ability to live life freely and with confidence—‘Because they (my parents) were protective of me, I became a bit fearful, I became scared of a lot of things’. Some were made to wear a medical mask or remain inside their house for no apparent medical reason. Some also felt that doctors and teachers kept them ‘in a bubble’ by advising them against playing sports or travelling—‘I've talked to Dr X about it, but because his other patients have gotten really sick, he’s telling me not to go (travel to Asia).’

Cautious to avoid health risks

Some were cautious and vigilant to avoid health risks to avoid being blamed for getting sick. They always considered the consequences of their behaviour and questioned, ‘is this going to affect my kidney?’ They were not able to drink alcohol or travel to certain places. They were constantly planning ahead for simple tasks such as what they would eat and drink. Participants from India mentioned being particularly careful not to get an infection when leaving the house.

Lagging and falling behind

Delayed independence

Participants felt they lacked the foundations for developing into independent adults and were unprepared for the future. Those who were on dialysis during childhood felt their lives had been put on hold—‘I have missed 3 years of my life’. Some had to live with their parents because they depended on them for financial support and were concerned about their ability to sustain employment and afford housing during periods of ill health—‘I’d like to move out, but if anything serious happens and I can’t work, I can’t pay for the place anymore’. They felt their ability to gain independence was limited because they had ‘grown up with pretty much everything being done for me’.

Failing to keep up with peers

Some were too tired and unable to concentrate and were often ‘falling asleep in school’. They missed learning the basics and felt unable to reach their potential—‘Now I experience difficulty while studying. If my basics were better, I would have scored higher (in mathematics).’ Some were upset as they watched their classmates graduate while they were left behind—‘I was studying engineering and I watched a lot of my friends go on and graduate from that programme’. This led them to feel lacking in intelligence and skills compared with their peers.

Socially inept

Having missed out on interacting with friends because of childhood CKD, some felt they lacked social skills as a young adult and felt ‘awkward’ and suffered ‘social anxiety’—‘I've missed out on like the social side to life as a kid… I have social anxiety. I struggle with big crowds and the work Christmas party I don't go to’. Some felt alone and isolated. One participant was confined at home during childhood to avoid infection—‘No one could really come over. I was just in my room for a little bit over a year’. Some withdrew from others because they ‘didn’t feel like being around people’ to avoid stigma, pity and having to explain themselves. Some lost friends or felt forgotten by them or became distanced from former friends because CKD had changed who they were and what they could do.

Defeated and hopeless

Incapacitated by worry

Participants worried about their health and ‘dying young’—‘I feel like I’m definitely going to die younger than a lot of my family’. Some participants, not yet on kidney replacement therapy worried about ‘having to rely on a (dialysis) machine in the future’. Transplant recipients were concerned about graft failure. Some were ‘living their lives on hold’ because of the constant daily worries—‘I get in a bad headspace and worrying about things that haven’t even happened yet (transplant failure)’.

An uncertain and bleak future

At times, when ‘they didn’t see the point anymore,’ they wanted to give up—‘When the doctor said, ‘Oh you might need to be on dialysis.’ It kind of just made me give up in school’. Some participants, particularly those with genetic kidney disease, braced themselves for deteriorating health and consequent restrictions—‘My life participation is going to decline and that I won’t be able to do things’. Participants who did not know the cause of their kidney disease felt ‘insecure’ about the future.

Unworthy of relationships

Some worried about ‘ending up alone,’ because they felt they ‘weren’t good enough’ for a partner and thought ‘no one would ever love them’. One participant from India explained: ‘if you have to buy an apple, you will take a fresh one, not the one that has a hole in the middle. They will choose the healthy one (for an arranged marriage). Another recalled their partner breaking up with them because of kidney disease—‘he said, ‘I want an active future. I don't want a future where I'm in and out of hospital with someone’.

Low self-esteem and shame

Childhood CKD impaired self-esteem through to adulthood—‘I am still not fully confident about myself, and this would not have happened (if I didn’t have CKD as a child)’. Some became ‘upset looking in the mirror’, felt ‘ashamed’ or ‘avoided going out’ because of CKD and treatment-related weight gain, stretch marks or scars—‘I didn't want to do anything because I had fluids (swelling) everywhere and I just wanted to be normal’. Some reported being bullied by others because of CKD.

Reorienting plans and goals

Focussing on the day-to-day

Thinking about the future was difficult because of the unpredictability of the kidney disease, so instead participants focussed on ‘living in the present’ and ‘doing a day at a time’. Some explained that whenever they planned their future, ‘it never seemed to happen’ (going back to school or work). Patients who had been on dialysis formed a habit of concentrating on getting through each day.

Planning parenthood

Some felt pressured to think about parenthood at a young age, when they were not ready to have a family, and said doctors advised to ‘have children as soon as possible’, ‘get their eggs harvested’ or advised that ‘it was going to be more difficult due to previous treatments and medication.’ One participant said, ‘to become a father I will have to do IVF (in vitro fertilisation)’. Some feared the possibility of genetic transmission and causing their child to suffer—‘I will never have my own kids, because I don’t know how I got the disease. Because if he or she ends up having a problem, I will be blaming myself’. Some women were concerned about jeopardising their kidney health (or graft) by becoming pregnant.

Forward and flexible planning

Participants had to think ahead, change goals or make adjustments to their lives because of kidney disease, which was frustrating though some learnt to accept this. Some transplant recipients tried to find part-time work in case they lost their graft. Participants with fluid and diet restrictions would ‘save’ their intake so they could eat and drink more freely at social events—‘I will not eat potassium foods and I’ll be careful today with water, so when I get to the party, I can actually have a soft drink’. Some established daily and travel schedules around the medication regimen.

Immersing oneself in normal activities

Refusing to miss out

Some strived to do ‘normal’ things refusing to let the CKD stop them. They ‘didn’t see themselves as unable to do things’. Some made adjustments to enable them to play sports—‘We did five-a-side football, which I was able to do because they made like a special shield that went over the kidney’. They were adamant not to fixate on restrictions.

Finding enjoyment

Some learnt to enjoy life more and to ‘appreciate the little things’ because of the kidney disease, making every effort to ‘enjoy every day and have fun’. During dialysis, patients developed new hobbies or invited friends to visit and play card games.

Determined to do what peers can do

Some were determined to do what their peers could do. During childhood, they desired ‘to be normal’ and to ‘be able to do everything everyone else did,’ which also included drinking—‘I still went out and drank, because I wanted to be normal’.

Being present at social events

Being able to socialise and ‘hang out’ with friends and family was important—‘(kidney disease) doesn’t impact me that it stops me from going out and having a social life’. At times, they had, ‘friends joining my dialysis session’ or ‘parents joining a school camp’.

Striving to reach potential and seizing opportunities

Encouragement from others

Participants talked about how ‘not being treated differently or as if they couldn’t do things’ helped them stay motivated and not to feel like a patient. Some found it helpful to meet others with kidney disease, ‘people that understood’—‘that was the point where my whole attitude towards everything changed, because I realised that I wasn’t alone and I realised that actually people were coping with it’.

Motivated by the illness

For some, CKD gave them ‘a reason to do things’ and motivated them ‘to make healthier choices in life’. Some made it their mission to be as fit as possible to ‘slow down’ the disease. Some were inspired to support and mentor other children and young adults with kidney disease—‘I’m there for the new generation, to help them cope and be that inspiration’.

Establishing new career goals

Some changed career path because they felt they lacked education, had health problems or wanted to avoid the risk of infection—‘I’d probably go into something with childcare. But because of infection and stuff, that’s probably not a good idea’. Others redirected their goals to pursue work in healthcare because the disease made them realise they wanted to be a ‘doctor’, ‘nurse’ or ‘social worker’—‘it made me realise that I wanted to be a nurse. I suppose that’s a good thing out of a bad situation’.

Grateful for opportunities

Some participated in activities (eg, world transplant games, cruises) that were organised by the hospitals, support groups and charity organisations.—‘I probably never would have experienced that (if I didn’t have kidney disease). Having experienced illness in childhood made them grateful for what they were able to do now as young adults—‘when I go on a hike or to the gym, I’m like, I am so lucky. I’m so grateful that I can do these things because I wasn’t able to do it before’.

Discussion

Young adults with childhood-onset CKD struggled with day-to-day restrictions and limitations in their ability to work, study and participate in social and leisure activities because of symptoms and side effects and burden of treatment, the need to minimise health risks and being overprotected by adults. They felt unable to keep up with their peers and attributed social anxiety and feelings of inferiority to missing out on social interaction and school during childhood. Some were frustrated in having to remain dependent on their parents and being unable to gain independence, move out of home and establish relationships, feeling defeated and hopeless about their future. These challenges meant they had to reorient their plans and goals. Some became determined to immerse themselves in normal activities and to take every opportunity to do what their peers were able to do. They reflected that childhood CKD gave them opportunities they would not have had otherwise (eg, participating in transplant games), or motivated them to establish career goals, for example, in counselling and nursing.

These findings were broadly consistent across the different demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, and their care settings. However, we noted some differences by age group, age at diagnosis, country and experience of dialysis. Younger participants reported difficulties with attending school/study and keeping up with peers, dropping out of higher education and were concerned about missing social events. Older participants were focussed on being able to work and establish a career path given their uncertain prognosis, and seemed to contemplate longer-term consequences. Those who were diagnosed with kidney disease at an older age found it more difficult to give up valued activities such as sport. There were some specific concerns such as infection, identified by participants in India, which may be attributable to the higher risk.23 They also worried about being ‘unsuitable’ for arranged marriage. Participants who had been on dialysis for a longer period of time during childhood seemed to face, to a greater extent, loss of friendship and inability to participate in recreational activities.

Our findings reflect those of previous studies,24 which have also found that young adults with childhood-onset CKD report difficulties with education, employment and social relationships,25–28 and perceive that their lives are ‘on hold’.29 30 These problems of life participation have also been documented in studies in young people diagnosed with other childhood chronic conditions, including cystic fibrosis, haematological and autoimmune disease, who also feel impaired in their social interactions and capacity to keep up with peers31 and have lower life satisfaction.32 Our study further reveals that young adults believe that missing school and social opportunities, and being ‘overprotected’ during childhood caused them to lack the fundamental skills and confidence for social interaction, and develop independence to participate in life as autonomous adults. Consequently, this instilled vulnerability, uncertainty and fear of their future in terms of day-to-day functioning, and setting and pursuing educational and career goals.

This study was multinational and offers in-depth insights gained from a reasonably diverse group of young adults with childhood-onset CKD. We achieved data saturation and used investigator triangulation to ensure that the themes reflected the breadth and depth of the data. However, there are some potential limitations. Most participants were from high-income countries, therefore the transferability of the findings to other populations and settings is uncertain. The sample was skewed in relation to gender with only one-third of the population being men, while CKD affects more men. This could be a weakness we want to acknowledge. Only two patients were receiving dialysis at the time of the study though most of the participants had been on dialysis previously and discussed their past experiences. Some interviews were conducted with parents present, but we are unable to determine if this inhibited open responses.

There is a need to improve life participation in patients with childhood CKD and strategies that encompass psychosocial, educational and vocational support delivered in both the paediatric and adult healthcare settings are suggested. A multidisciplinary model of care involving nephrologists, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists may help to bring awareness and address the barriers to life participation. For example by managing unresolved anxiety, uncertainty and fears to strengthen confidence and self-esteem in participating in activities, establishing relationships and decision-making about parenthood. Identifying and building social networks may motivate and support young patients to develop independence, autonomy, and determination to engage in life activities and work towards their goals. Online support groups and camps could promote a sense of normality and social inclusion.33 School-based interventions, that includes advocacy for patients to increase understanding among their peers and individual tutoring may improve social and educational outcomes.34 Social workers and potentially peer navigators, could assist young adults with finding employment, and accessing social benefits and housing.27 Given the medical, ethical and emotional complexities of fertility and parenthood in CKD, we suggest counselling that is sensitive to patients’ preparedness and life priorities.35 36

Rehabilitation programmes may have potential in young people with chronic kidney disease. Trials of cognitive-based problem-solving strategies improved level of activity and life participation in children with other conditions including development coordination disorder and cerebral palsy.37 38 This study used a strategy comprised of identifying occupational performance problems by the children and their parents, and conducting weekly group sessions for 10 weeks, along with 15 min per day of home activities. Physical rehabilitation programmes for adults on dialysis have been shown to improve the ability to perform daily activities and physical functioning.39 This particular programme comprised of an assessment of level of activity and functional ability, collaborative goal setting that accounted for patient’s preferences and lifestyle, problem solving to address barriers to physical activity and identifying social supports to maintain an increased level of activity. Similar rehabilitation programme may be adapted for young people with chronic kidney disease, focussed on relevant activities in this population.

While the need to improve life participation in young adults with childhood CKD is evident, trials of interventions to improve the aspects of life participation prioritised by our participants are sparse. Recognising that patient involvement in research improves the relevance, implementation and uptake of research,40 we suggest that future studies should involve patients in co-designing and evaluating interventions. Also, we recognise that assessing this outcome may be challenging as there is currently no patient-reported outcome measure for life participation validated for use in this population. Further work is needed to identify or establish a patient-reported outcome that includes the dimensions of life participation that are important to children and young adults with CKD.

Young adults encounter lifestyle limitations and missed school and social opportunities during childhood CKD and as a consequence feel lacking in confidence and social skills, uncertain of the future and vulnerable. Some re-adjust their goals and become more determined to participate in ‘normal’ activities to avoid missing out. Strategies and interventions are needed to improve life participation in young adults with childhood CKD and thereby strengthen their mental and social well-being and enhance overall health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for sharing their interesting and thoughtful perspectives in this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @jasmijnkerklaan, @allisontong1

Contributors: Research idea and study design: AT and JK. Data acquisition: JK. Data analysis/interpretation: JK, EH, CH and AT. Supervision or mentorship: AT, JG, JCC. AT, JG, JCC, YC, CG, MC, LH, JR, AS and GW contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This project is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (ID 1092957). The funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All participants provided written informed and voluntary consent. The study was approved by The University of Sydney, The Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (Westmead, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia), Royal Children’s Hospital (Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) and Princess Alexandra Hospital (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia). Furthermore, The University of Sydney (Australia) provided ethics approval to recruit through the international SONG Initiative Patient Network. Patients from any country can voluntarily register to receive information about opportunities to participate in SONG-related research. The network is hosted on the University of Sydney server. Participants outside of Australia were not recruited from hospitals/institutions.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. No data are available. No data are available. Upon reasonable request de-identified participant data could be made available.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Gerson AC, Wentz A, Abraham AG, et al. Health-related quality of life of children with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics 2010;125:e349–57. 10.1542/peds.2009-0085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong A, Tjaden L, Howard K, et al. Quality of life of adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr 2011;159:670–5. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lande MB, Gerson AC, Hooper SR, et al. Casual blood pressure and neurocognitive function in children with chronic kidney disease: a report of the children with chronic kidney disease cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1831–7. 10.2215/CJN.00810111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haavisto A, Korkman M, Holmberg C, et al. Neuropsychological profile of children with kidney transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:2594–601. 10.1093/ndt/gfr650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper SR, Gerson AC, Johnson RJ, et al. Neurocognitive, social-behavioral, and adaptive functioning in preschool children with mild to moderate kidney disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016;37:231–8. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thys K, Schwering K-L, Siebelink M, et al. Psychosocial impact of pediatric living-donor kidney and liver transplantation on recipients, donors, and the family: a systematic review. Transpl Int 2015;28:270–80. 10.1111/tri.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groothoff JW, Grootenhuis M, Dommerholt A, et al. Impaired cognition and schooling in adults with end stage renal disease since childhood. Arch Dis Child 2002;87:380–5. 10.1136/adc.87.5.380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groothoff JW, Grootenhuis MA, Offringa M, et al. Social consequences in adult life of end-stage renal disease in childhood. J Pediatr 2005;146:512–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocha S, Fonseca I, Silva N, et al. Impact of pediatric kidney transplantation on long-term professional and social outcomes. Transplant Proc 2011;43:120–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tjaden LA, Grootenhuis MA, Noordzij M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with pediatric onset of end-stage renal disease: state of the art and recommendations for clinical practice. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:1579–91. 10.1007/s00467-015-3186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellerio H, Alberti C, Labèguerie M, et al. Adult social and professional outcomes of pediatric renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2014;97:196–205. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a74de2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson CS, Gutman T, Craig JC, et al. Identifying important outcomes for young people with CKD and their caregivers: a nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;74:82–94. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A, Samuel S, Zappitelli M, et al. Standardised outcomes in Nephrology-Children and adolescents (SONG-Kids): a protocol for establishing a core outcome set for children with chronic kidney disease. Trials 2016;17:401. 10.1186/s13063-016-1528-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SONG-Kids Standardised outcomes in nephrology – children and adolescents (SONG-Kids), 2019. Available: https://songinitiative.org/projects/song-kids/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization Health statistics and information systems, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/

- 16.Ju A, Josephson MA, Butt Z, et al. Establishing a core outcome measure for life participation: a standardized outcomes in nephrology-kidney transplantation consensus workshop report. Transplantation 2019;103:1199–205. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logeman C, Guha C, Howell M, et al. Developing consensus-based outcome domains for trials in children and adolescents with CKD: an international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:533–45. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanson CS, Craig JC, Logeman C, et al. Establishing core outcome domains in pediatric kidney disease: report of the standardized outcomes in Nephrology-children and adolescents (SONG-KIDS) consensus workshops. Kidney Int 2020;98:553–65. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groothoff JW. Long-Term outcomes of children with end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20:849–53. 10.1007/s00467-005-1878-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjaden LA, Vogelzang J, Jager KJ, et al. Long-Term quality of life and social outcome of childhood end-stage renal disease. J Pediatr 2014;165:336–42. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, et al. COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies). Guidelines for reporting health research: a user’s manual, 2014: 214–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization International classification of functioning disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortes-Santiago N, Leung DH, Castro E, et al. Hepatic steatosis is prevalent following orthotopic liver transplantation in children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;68:96–103. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton AJ, Caskey FJ, Casula A, et al. Psychosocial health and lifestyle behaviors in young adults receiving renal replacement therapy compared to the general population: findings from the speak study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;73:194–205. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Henning P, Wong G, et al. Experiences and perspectives of adolescents and young adults with advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61:375–84. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cura J. Interpreting transition from adolescence to adulthood in patients on dialysis who have end-stage renal disease. J Ren Care 2012;38:118–23. 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2012.00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray PD, Dobbels F, Lonsdale DC, et al. Impact of end-stage kidney disease on academic achievement and employment in young adults: a mixed methods study. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:505–12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis H, Arber S. Impact of age at onset for children with renal failure on education and employment transitions. Health 2015;19:67–85. 10.1177/1363459314539773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowley-Matoka M. Desperately seeking “normal”: the promise and perils of living with kidney transplantation. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:821–31. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molzahn AE, Bruce A, Sheilds L. Learning from stories of people with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Nurs J 2008;35:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nap-van der Vlist MM, Kars MC, Berkelbach van der Sprenkel EE, et al. Daily life participation in childhood chronic disease: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:463–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthie N, Hamilton J, Wells D, et al. Perceptions of young adults with sickle cell disease concerning their disease experience. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1441–51. 10.1111/jan.12760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen C, Vassilev I, Kennedy A, et al. Long-term condition self-management support in online communities: a meta-synthesis of qualitative papers. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e61. 10.2196/jmir.5260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lansing L. Back to school for the child on long-term hemodialysis. J Am Assoc Nephrol Nurses Tech 1981;8:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bramham K, Lightstone L. Pre-pregnancy counseling for women with chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol 2012;25:450–9. 10.5301/jn.5000130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiles KS, Bramham K, Vais A, et al. Pre-pregnancy counselling for women with chronic kidney disease: a retrospective analysis of nine years' experience. BMC Nephrol 2015;16:28. 10.1186/s12882-015-0024-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron D, Craig T, Edwards B, et al. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP): a new approach for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2017;37:183–98. 10.1080/01942638.2016.1185500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thornton A, Licari M, Reid S, et al. Cognitive orientation to (daily) occupational performance intervention leads to improvements in impairments, activity and participation in children with developmental coordination disorder. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:979–86. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1070298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tawney KW, Tawney PJ, Hladik G, et al. The life readiness program: a physical rehabilitation program for patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;36:581–91. 10.1053/ajkd.2000.16197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liabo K, Boddy K, Burchmore H, et al. Clarifying the roles of patients in research. BMJ 2018;361:k1463. 10.1136/bmj.k1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-037840supp001.pdf (25.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-037840supp002.pdf (40.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-037840supp003.pdf (32.3KB, pdf)