Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is considered a lethal disease with a low survival rate due to its late-stage diagnosis, few opportunities for resection and lack of effective therapeutic strategies. Multiple, highly complex effects of gut microbiota on pancreatic cancer have been recognized as potential strategies for targeting tumorigenesis, development and treatment in recent decades; some of the treatments include antibiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. Several bacterial species are associated with carcinogenesis of the pancreas, while some bacterial metabolites contribute to tumor-associated low-grade inflammation and immune responses via several proinflammatory factors and signaling pathways. Given the limited evidence on the interplay between gut microbiota and pancreatic cancer, risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer, such as diabetes, chronic pancreatitis and obesity, should also be taken into consideration. In terms of treatment of pancreatic cancer, gut microbiota has exhibited multiple effects on both traditional chemotherapy and the recently successful immunotherapy. Therefore, in this review, we summarize the latest developments and advancements in gut microbiota in relation to pancreatic cancer to elucidate its potential value.

Keywords: gut microbiota, pancreatic cancer, inflammation, immune response, immunotherapy

Highlights

Alterations in gut microbiota in the human intestinal tract influence the initiation and development of pancreatic cancer.

Chronic inflammation and the immune response generated by microbial metabolites modulate biological activities of pancreatic cancer.

Gut microbiota also impacts pancreatic cancer via diabetes, obesity, and chronic inflammation.

Treatments for pancreatic cancer could also affect gut microbiota.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is commonly regarded as one of the most fatal diseases owing to its high malignancy and poor prognosis. According to the latest data, the 5-year overall survival rate of PC has increased slightly, but remains <10% (American Cancer Society, 2020). Rare representative symptoms and diagnosis of PC are considered key reasons why the mortality is close to its incidence (Kamisawa et al., 2016). Surgical resection is the only potential cure for patients with localized PC, but no more than 20% of whom are eligible for initial resection. With these shortcomings, other substitutive therapies are highlighted for early metastasis or recurrence. However, treatment resistance lowers the therapeutic effectiveness and limits clinical utility. Taken together, an earlier diagnosis and implementation of efficient strategies appear to be increasingly beneficial.

As the most neglected system in the human body, gut microbiota (GM) has received increasing attention in recent years. GM comprises up to trillions of microbes within the human intestinal tract (Costello et al., 2009; Sekirov et al., 2010). Data on the human fecal microbial metagenome showed that an aggregate of 9.9 million microbial genes across these fecal microbiomes have been identified (Li et al., 2014). Despite several studies on the genetic susceptibility of dysbiosis on mice transplanted with disease-associated GM, the question remains open as to whether GM dysbiosis is a consequence or a cause of human diseases (Lynch and Pedersen, 2016). Influenced by age, dietary habits, antibiotic intake and other environmental factors, GM has been found to have a crucial impact on obesity, diabetes mellitus and even carcinogenesis. The Human Microbiome Project Part 2 has explored the mechanisms of GM in inflammatory bowel disease (Lloyd-Price et al., 2019), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and prediabetes (Zhou et al., 2019). Nevertheless, until now, what is emerging and has been discovered regarding the effect of GM on PC is just a tip of the iceberg. This review will elucidate the latent causality and underlying relevance between PC and GM.

Influence of GM on PC

Alterations of Microbial Metabolites

Despite the colonization of the human gastrointestinal tract, only 10 are determined as carcinogenesis by International Agency for Cancer Research (de Martel et al., 2012; IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 2012), which indicates complex relations existing among GM, environmental triggering factors and cancer initiation (Karpinski, 2019).

There is flourishing evidence demonstrating changes in physical characteristics resulting from GM overgrowth (Shin et al., 2019). GM disorders reduce the thickness of mucus layer, which is always followed by a decreased antimicrobial defense and fewer gut peptides from L-cells and limited short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Cani, 2018). As a consequence, transformations of relative microbial metabolites lead to subsequent chain reactions. The reduced gut peptides, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY, play regulatory roles in food intake and glucose metabolism. Moreover, PPAR-γ inactivation resulting from lack of SCFAs requires higher oxygen available for the microbiota at the proximal mucosa and promotes Enterobacteriaceae proliferation (Philipson et al., 2013). Despite with low concentrations, bacterial metabolites, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), flagellin and SCFAs, can reach the circulation and distant organs via paracellular diffusion or co-transport with chylomicrons. To be specific, LPS, an important cytoderm component of gram-negative bacteria, can interact with several Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways with a distinct structural composition from other bacterial taxa (Backhed et al., 2003). Furthermore, lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a surface component of gram-positive bacteria and a key virulence factor, has been found to trigger the over-secretion of proinflammatory factors by binding to CD14 or TLR2 (Hermann et al., 2002). This activity may result in the ultimate development of PC, as illustrated by its involvement in chronic pancreatitis progression on mice with infection of Enterococcus faecalis (Maekawa et al., 2018). Another microbial metabolite generated by 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria and secondary bile acids, deoxycholic acid (DCA), was shown to enhance the induction of PC (Cao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). DCA also accelerates the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (Saretzki, 2010) and the progression of intestinal cancer through increasing DNA damage and genome instability (Louis et al., 2014). Moreover, DCA-induced activation of the EGFR ligand, amphiregulin was identified as an oncogenic factor in both colorectal and PC by EGFR, mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and STAT3 signaling pathways (Nagathihalli et al., 2014). Acetate, propionate and butyrate are typical SCFAs. For instance, butyrate can interfere histone modifications and transcriptional regulation (Cani and Jordan, 2018). Additionally, a decrease in propionate lowers the abundance of mucosal-associated invariant T cells and regulatory T cells guarding the intestinal lamina propria (Cani, 2018) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The effects of microbes, bacterial components and their metabolites in pancreatic cancer.

| Item | Content | Description | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial components or metabolites | Lipopolysaccharides | An important cytoderm component of gram-negative bacteria | Interact with several Toll-like receptor signaling pathways with a distinct structural composition from other bacterial taxa | Backhed et al., 2003 |

| Lipoteichoic acid | A key virulence factor on the gram-positive bacteria surface | Trigger the over-secretion of proinflammatory factors by binding to CD14 or TLR2 | Hermann et al., 2002 | |

| Deoxycholic acid | A kind of secondary bile acid generated by 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria from a high dietary fat intake | Accelerate the senescence-associated secretory phenotype and the progression of intestinal cancer via promoting DNA damage and genome instability and activation of the EGFR ligands amphiregulin | Saretzki, 2010; Louis et al., 2014; Nagathihalli et al., 2014 | |

| Short chain fatty acids | Fermented dietary fiber in intestinal tract, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate | Stimulate the secretion of gut peptides involved in food intake or glucose metabolism | Vatanen et al., 2018 | |

| Butyrate inhibits histone deacetylases via interfering histone modifications and transcriptional regulation | Cani and Jordan, 2018 | |||

| Propionate decreases the abundance of mucosal-associated invariant T cells and Treg guarding inside the intestinal lamina propria | Cani, 2018 | |||

| Cytolethal distending toxin | Produced by proteobacteria | Participate in genetic alterations and induce formation of endoreduplication or hyperploidy even in the absence of cell division | Nougayrede et al., 2005 | |

| Cyclomodulins | A growing family of bacterial molecules | Cause carcinogenesis through the active interference with host cell cycle | Nougayrede et al., 2005 | |

| Cytotoxic necrotizing factor | A prevalent virulence determinant exclusively confined to E. coli phylogroup B2 | Lead to the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells | Nougayrede et al., 2005 | |

| Certain typical bacteria | Enterobacteriaceae | Natural inhabitants in the human intestine implicated in intestinal and extraintestinal illnesses | Promote proliferation by PPAR-γ that requires higher oxygen available for the microbiota at the proximal mucosa | Philipson et al., 2013 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Aggravate chronic pancreatitis and damage pancreas tissue by the stimulation inflammatory cytokines | Maekawa et al., 2018 | ||

| H. pylori | An initiating factor of kinds of gastrointestinal cancer | Increase the risk of pancreatic cancer relating to gastric ulcer via the greater endogenous nitrosation and the inflammatory response to ulcer development and healing process | Bao et al., 2010 | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | The most prevalent oral microorganism for periodontal disease | Its associated serum level of IgG is positively related to the risk of PC | Ahn et al., 2012 | |

| Fusobacterium spp | A group of anaerobic bacterium colonizing oral cavity | Remain malignant potential in the development of pancreatic cancer with the 8.8% presence | Mitsuhashi et al., 2015 | |

| Bifidobacteria | The dominant bacterial populations in the gastrointestinal tract interacted in maturation of the immune system and use of dietary components | Induct tumor-specific T cell and increase CD8 (+) T cell numbers in the tumor microenvironment combined with anti-PD-L1 immunomodulator | Sivan et al., 2015 | |

| Bacteroides | One of the most abundant bacterial phyla in the human gut breaking down host dietary and mucosal polysaccharides | Assist Escherichia coli to improve the tumorigenic effectiveness via triggering damage of double-stranded DNA | Cougnoux et al., 2014 |

Several bacterial toxic productions have been identified as possible carcinogenetic molecules. Colibactin and Bacteroides fragilis toxin assist Escherichia coli to improve the tumorigenic effectiveness via triggering damage of double-stranded DNA (Cougnoux et al., 2014). Significantly, cyclomodulins, a growing family of bacterial molecules, play putative roles in tumorigenesis through the active interference with host cell cycles. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor from E. coli and CagA lead to the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells, while cytolethal distending toxin and cycle inhibiting factor act as predisposing factors of tumorigenesis by participating in genetic alterations and inducing formation of endoreduplication or hyperploidy even in the absence of cell division (Nougayrede et al., 2005).

Alterations of Specific Microbial Species in Human Intestine

Growing evidence demonstrates that GM affects the outcomes of PC (Aykut et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019). Compared to the short-term survivors, long-term PDAC survivors possessed higher tumor microbial diversity and more composition, which is presented as a predict on PDAC survival (Riquelme et al., 2019). H. pylori may be an indispensable issue for the initiation and progression of PC. The increasing risk of PC relating to gastric ulcer found in a prospective cohort study involving 51,529 male subjects might have resulted from the greater endogenous nitrosation and the inflammatory response due to H. pylori infection (Bao et al., 2010). Additionally, given the overlap of oral microbiomes in the intestine, bacterial translocation from oral cavity or intestinal tract is also closely associated with PC (Whitmore and Lamont, 2014). For instance, Fusobacterium spp, a group of anaerobic bacterium colonizing the oral cavity, has been demonstrated a potentially prognostic biomarker of PC with the 8.8% presence (Mitsuhashi et al., 2015). Large prospective studies have reported a higher risk of PC in patients with higher concentrations of Porphyromonas gingivalis (Fan et al., 2018) and a reduced risk for increased levels of specific antibodies against commensal oral bacteria (Michaud et al., 2013) (Table 1).

Currently, compared with normal tissue of pancreas, a 1000-fold increase in intrapancreatic bactibilia was observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) specimens (Dickson, 2018). This finding is widely divergent from the previous assumption of a sterile pancreas (Wei et al., 2019; Nejman et al., 2020). Data from a constituent analysis of microbes harboring in pancreatic cyst fluid characterized this specific microbiota ecosystem and demonstrated microbiota harboring in the pancreas; the results showed that some taxa with possible deleterious effects within this niche may lead to the pancreatic neoplastic process (Li et al., 2017). Notably, it is the bacterial composition, rather the bacterial abundance, within the pancreas that correlates with pancreatic carcinogenesis. Therefore, the mechanism by which microbes flow toward and penetrate the pancreas is a key issue. The identification of Enterococcus and Enterobacter species primarily found in bile indicate a possible pathway where GM is transported toward the pancreatic tissue (Maekawa et al., 2018). Additionally, Pushallkar et al. demonstrated the accessibility of gut bacteria to pancreas, suggesting their direct effect on the microenvironment around the pancreas (Pushalkar et al., 2018).

Microbiota-Driven Chronic Inflammation

In the past several decades, PC has been regarded as an inflammation-driven disease. However, explorations of details underlying chronic inflammation and PC are still ongoing. The tumorigenesis-promoting effects of the transportation of bioactive molecule to the tumor microenvironment, such as growth, survival and proangiogenic factors, were confirmed, which was unanticipated and counter to the previous understanding of tumor-associated inflammation (Grivennikov et al., 2010). Hence, inflammation is proposed as an emerging hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Moreover, compelling investigations shed light on the important contributions of mutant Kras influenced by inflammation and changes in GM to the key activities related to oncogenesis. Despite its common mutation in ~90% of PC cases, the activation of Kras still requires hyperstimulation from LPS-driven inflammation (Daniluk et al., 2012). The activated Kras subsequently accelerates carcinogenesis by activating nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway components, including inhibitor of NF-κB kinase 2 and cyclooxygenase 2 (Huang et al., 2014). Another study supplied evidence that chronic inflammation in pancreatic tissue triggers the oncogenic mutation of Kras in insulin-positive endocrine cells and induces dedifferentiation of functional epithelial cells, which results in PDAC (Gidekel Friedlander et al., 2009). Additionally, periodontal inflammations, commonly including gingivitis and periodontitis, are considered to cause systemic inflammation (Chang et al., 2016). Porphyromonas gingivalis is the most prevalent oral microorganism in periodontal disease, of which the level of serum immunoglobin G is reported to 8.8% correlate with PC (Ahn et al., 2012).

Microbiota-Mediated Immunoregulation

Immune cells along with substantial microbes maintain the symbiosis between the human body and microorganisms (Mowat and Agace, 2014). Compositions of the microbiota are influenced by the immune system. Conversely, GM also plays an indispensable role in the maturation and continued education of the host immune system (Fulde and Hornef, 2014) and modulates the homeostatic state when existing an imbalance between the immune system and tumorigenesis (Kau et al., 2011; Schwabe and Jobin, 2013).

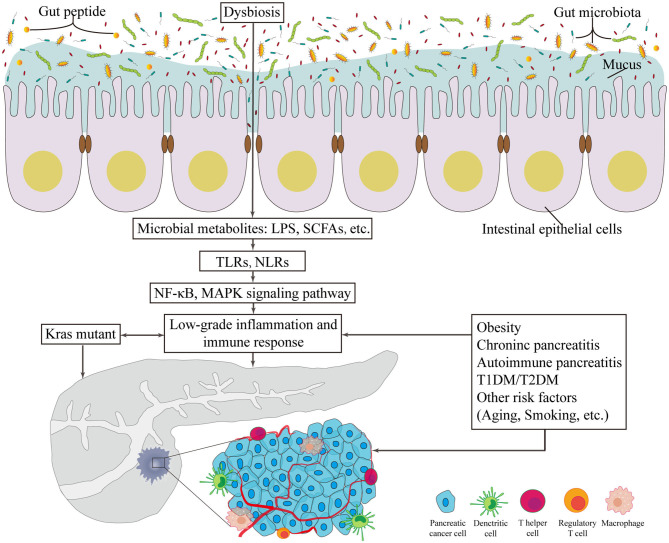

A limited number of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) exists in the innate immune system; these receptors recognize pathogens of microorganisms, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns. TLR family plays a remarkable role in inflammation transmission and tumorigenesis acceleration once activated in response to microbiota-derived products (Zambirinis et al., 2015), such as bacterial LPS, LTA, lipoproteins, lipopeptides, flagellin, single- or doubled-stranded DNA, and CpG DNA (Kawai and Akira, 2010). In addition to detecting the conserved microbe associated molecular patterns, TLRs can also be activated by inflammation or damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). As downstream targets of these patterns, the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways are activated, which ultimately initiates cytokine production and further recruitment of proinflammatory entities and even contributes to the occurrence and development of cancer (Rakoff-Nahoum and Medzhitov, 2009) (Figure 1). Importantly, one example of protection against pancreatic carcinogenesis is to blockade the activation of TLR7 to inhibit its interactions with the STAT3, Notch, NF-κB and MAPK pathways. This effect has been successfully tested in systemic lupus erythematosus (Ochi et al., 2012). Similarly, more studies focus on another PRR, the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod)-like receptors (NLRs). These receptors recognize microbial signals to activate caspase-1 inflammasomes and release of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 (such as NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP4) (Martinon et al., 2009). Additionally, NLRs participate in bacterial clearance by inducing the activation of NF-κB, P38 MAPK and interferon signaling; regulate autophagy-associated protein expressions; and promote autophagosome formation (such as NOD1 and NOD2) (Moreira and Zamboni, 2012; Mukherjee et al., 2018). As a result, the intestinal microbiota plays a critical role in the maturation and continued education of the host immune system (Fulde and Hornef, 2014), provides protection against pathogen overgrowth (Kamada et al., 2013), and influences host-cell proliferation (Ijssennagger et al., 2015) and vascularization (Reinhardt et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

The potentially carcinogenetic roles of gut microbiota in pancreatic cancer. Disorders of gut microbiota contribute to multiple changes associated with pancreatic cancer. Locally, it lowers the thickness of intestinal mucus and the level of gut peptide. Infiltrated bacterial metabolites, such as LPS and SCFAs, can render low-grade inflammation and immune responses via TLR and NLR that activates NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Besides, risk factors of pancreatic cancer provide novel consequential directions to explore the relationship between gut microbiota and pancreatic cancer. LPS, lipopolysaccharides; SCFA, short chain fatty acid; TLR, Toll-like receptor; NLR, Nod-like receptor; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; MAPK, mitogen activated protein kinase; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

GM and Risk Factors for PC

Since the initiating oncogenic factor, mutant Kras, alone cannot sufficiently explain the oncogenesis and the development of PC, additional environmental and metabolic stressors are likely required (Eibl and Rozengurt, 2019). The effects of bacterial etiology on PC could well be underestimated because the direct link between cancers and bacterial infections is not always detectable. Nevertheless, mounting evidence on the association between GM and the relative risks of PC has been presented in numerous studies (Figure 1).

Obesity

It is no longer a novel discovery that obesity significantly increases the risk and lowers the overall survival rate of PC (Li et al., 2009). Compared to leaner counterparts, obese mice and humans present a decrease in the overall diversity of GM, which has recently been considered the main reason for alterations in metabolic signaling pathways (Mishra et al., 2016). Therein, increases in Firmicutes species and reductions in Bacteroides species are mostly obvious. Dysbiosis is associated with obesity and increased risk of cancer due to the generation of procarcinogenic microbial metabolites, low-grade inflammation and the loss of energy (Rogers et al., 2014). The modulation of gut peptides on obesity and tumorigenesis has been reported in many cancers, but multiple promising areas warrant further investigations in PC. The increasing circulating levels of inflammatory factors derived from adipose tissues in individuals with obesity and diabetes, such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, activate the innate immune system via abnormal regulation of the NF-kB signaling pathway (Creely et al., 2007), which has been strongly demonstrated to be activated in PC.

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is another strong risk factor (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001), presenting as a localized or systemic inflammation. Non-alcoholic fatty pancreatic disease was recently identified as a novel clinical obesity-related disease that increases pancreatic fatty degeneration and may progress to chronic inflammation and PC (Tomita et al., 2014). Concomitantly, overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine was commonly observed among chronic pancreatitis patients, with up to 92% of patients presenting this increase (Kumar et al., 2014; Capurso et al., 2016). Maekawa and coworkers have presented direct proof of E. faecalis in chronic pancreatitis (Maekawa et al., 2018). Although the association of subclinical chronic pancreatitis and PC remains ambiguous, evidence showed E. faecalis or LTA might aggravate chronic pancreatitis and damage pancreatic tissue by stimulating inflammatory cytokines and become potential biomarkers for PC.

Diabetes

T2DM is associated with moderate and profound intestinal dysbiosis. Data from a metagenome analysis show an increase in certain Lactobacillus species but a decrease in the numbers of butyrate-producing Roseburia intestinalis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in stool samples from T2DM patients (Qin et al., 2012). Currently, the t2definitive causal relationships among GM, SCFAs and T2DM have been reported. One study found that the improved insulin response after oral glucose-tolerance test was related to the increase in butyrate driven by host-genetics, while the increasing risk of T2DM was causally associated with production or absorption abnormalities of propionate (Sanna et al., 2019). Moreover, studies of the environmental determinants of diabetes suggested the protective effect of SCFAs against T1DM (Vatanen et al., 2018). Mechanistically, SCFA recognition by GPR-41or−43 subsequently stimulate the secretion of gut peptides involved in food intake or glucose metabolism. Nevertheless, further extensive exploration of influences of other microbial metabolism or gut microbiomes on diabetes is warranted.

Therapy

The use of bacterial toxins from Streptococcus erysipelas and Serratia species for sarcoma treatment in 1891 (Coley, 1910) established the application of bacteria or their metabolites in cancer therapy. Fecal microbiota transplantation has become a novel therapeutic approach for severe or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (Kelly, 2013; Hvas et al., 2019), although more studies to identify the efficacy and safety of this approach in cancer treatments are needed. Applications of GM in cancer therapy have become increasingly prevalent.

Chemotherapy

Although chemotherapy is efficient in inhibiting proliferation or shrinking the volume of cancer, there still exist problems in severe side effects and chemoresistance (Chabner and Roberts, 2005). Nevertheless, chemotherapy still maintains a central status in cancer therapy, especially synergized with GM. For example, oxaliplatin, a platinum preparation especially for PC chemotherapy, would be reduced without the assistance of the innate immune response activated by GM (Iida et al., 2013). Additionally, gemcitabine, the first-line chemotherapeutic drug for PC, was also shown to be affected by pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase and cytidine deaminase enzymes, most of which are produced by Gamma-proteobacteria and mycoplasma identified inside PDAC tumors; these data provide an individualized and targeted strategy for combating chemoresistance based on microbiota modulation (Vande Voorde et al., 2014).

Current tools designed to modify GM are quite blunt and almost all of them are focused on the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs rather than their efficacy. James and colleagues proposed the TIMER (translocation, immunomodulation, metabolism, enzymatic degradation and reduced diversity and ecological variation) method to summarize interactions between GM and host in order to modulate chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity (Alexander et al., 2017). Interestingly, GM is responsible for promoting the development of chemotherapy-induced mechanical hyperalgesia partly mediated by TLR4-expressing macrophages, while that pain was reduced in germ-free or antibiotics-pretreated mice (Shen et al., 2017).

Immunotherapy

In the late nineteenth century, William Coley proposed the first immunotherapeutic concept based on pyogenic bacteria (Coley, 1991). Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have recently become fairly prominent, several negative feedback pathways due to resistance necessitates a greater focus on increasing the efficacy of immunotherapy. Currently, GM has been recognized as a possible modulator influencing immune responses in different individuals (Robert et al., 2011; Borghaei et al., 2015). Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) are more efficacious in cancers with Kras mutations, which still lacks targeted therapies (Ansell et al., 2015; Routy et al., 2018). A study showed that oral administration of Bifidobacteria combined with an anti-PD-L1 immunomodulator could induce the production of tumor-specific T cells and increase CD8(+) T cell numbers. Correspondingly, Bifidobacterium facilitates the effects of anti-PD-L1 via T-cell priming and peritumoral accumulation in melanoma (Sivan et al., 2015). As vigorously as the field of immunotherapy is growing, there is still no remarkable improvement in the survival of PC patients. This gap in care reflects the urgent demand for novel treatment strategies, such as considering the auxiliary effect of GM.

Perspectives

PC is highly malignant and lacks effective treatments. GM has been recognized to involve in the inflammatory state and immune responses in PC and its associated risk factors. Targeting GM has been explored as a novel opportunity for cancer chemotherapy and immunotherapy via alterations of not only GM compounds but also molecules related to the immune response and chronic inflammation. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which certain molecules or subtypes of immune cells are targeted for microbiota-associated initiation, progression, development and treatment of PC remain unclear, leaving extensive room for further explorations.

Author Contributions

YL and LJ contributed to the conception and design of the review. QL wrote the main text of the manuscript. MJ prepared the figures and tables. QL and MJ contribute equally to this review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all investigators at the participating study sites. The authors thank American Journal Experts for English language editing.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- E. faecalis

Enterococcus faecalis

- GM

gut microbiota

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- LTA

lipoteichoic acid

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NLR

Nod-like receptor

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- PC

pancreatic cancer

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- SCFA

short chain fatty acid

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TLR

Toll-like receptor.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by grants from the Jilin Province health and technology innovation project (No. 2017J047).

References

- Ahn J., Segers S., Hayes R. B. (2012). Periodontal disease, Porphyromonas gingivalis serum antibody levels and orodigestive cancer mortality. Carcinogenesis 33, 1055–1058. 10.1093/carcin/bgs112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J. L., Wilson I. D., Teare J., Marchesi J. R., Nicholson J. K., Kinross J. M. (2017). Gut microbiota modulation of chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 356–365. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2020). Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. Available online at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf (accessed August 26, 2020).

- Ansell S. M., Lesokhin A. M., Borrello I., Halwani A., Scott E. C., Gutierrez M., et al. (2015). PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory hodgkin's lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 311–319. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykut B., Pushalkar S., Chen R., Li Q., Abengozar R., Kim J. I., et al. (2019). The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 574, 264–267. 10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Normark S., Schweda E. K., Oscarson S., Richter-Dahlfors A. (2003). Structural requirements for TLR4-mediated LPS signalling: a biological role for LPS modifications. Microbes Infect. 5, 1057–1063. 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00207-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F., Mantovani A. (2001). Inflammation and cancer: back to virchow? Lancet 357, 539–545. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y., Spiegelman D., Li R., Giovannucci E., Fuchs C. S., Michaud D. S. (2010). History of peptic ulcer disease and pancreatic cancer risk in men. Gastroenterology 138, 541–549. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghaei H., Paz-Ares L., Horn L., Spigel D. R., Steins M., Ready N. E., et al. (2015). Nivolumab vs. docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1627–1639. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. (2018). Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 67, 1716–1725. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D., Jordan B. F. (2018). Gut microbiota-mediated inflammation in obesity: a link with gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 671–682. 10.1038/s41575-018-0025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., Xu M., Dong W., Deng B., Wang S., Zhang Y., et al. (2017). Secondary bile acid-induced dysbiosis promotes intestinal carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 140, 2545–2556. 10.1002/ijc.30643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capurso G., Signoretti M., Archibugi L., Stigliano S., Delle Fave G. (2016). Systematic review and meta-analysis: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in chronic pancreatitis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 4, 697–705. 10.1177/2050640616630117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabner B. A., Roberts T. G., Jr. (2005). Timeline: chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 65–72. 10.1038/nrc1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. S., Tsai C. R., Chen L. T., Shan Y. S. (2016). Investigating the association between periodontal disease and risk of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 45, 134–141. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley W. B. (1910). The treatment of inoperable sarcoma by bacterial toxins (the mixed toxins of the streptococcus erysipelas and the bacillus prodigiosus). Proc. R. Soc. Med. 3, 1–48. 10.1177/003591571000301601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley W. B. (1991). The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas. With a report of ten original cases. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1893, 3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E. K., Lauber C. L., Hamady M., Fierer N., Gordon J. I., Knight R. (2009). Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326, 1694–1697. 10.1126/science.1177486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougnoux A., Dalmasso G., Martinez R., Buc E., Delmas J., Gibold L., et al. (2014). Bacterial genotoxin colibactin promotes colon tumour growth by inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Gut 63, 1932–1942. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creely S. J., Mcternan P. G., Kusminski C. M., Fisher F. M, Da Silva N. F., et al. (2007). Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 292, E740–E747. 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniluk J., Liu Y., Deng D., Chu J., Huang H., Gaiser S., et al. (2012). An NF-kappaB pathway-mediated positive feedback loop amplifies Ras activity to pathological levels in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1519–1528. 10.1172/JCI59743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Martel C., Ferlay J., Franceschi S., Vignat J., Bray F., Forman D., et al. (2012). Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 13, 607–615. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson I. (2018). Microbiome promotes pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15:328. 10.1038/s41575-018-0013-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibl G., Rozengurt E. (2019). KRAS, YAP, and obesity in pancreatic cancer: a signaling network with multiple loops. Semin. Cancer Biol. 54, 50–62. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Alekseyenko A. V., Wu J., Peters B. A., Jacobs E. J., Gapstur S. M., et al. (2018). Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut 67, 120–127. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulde M., Hornef M. W. (2014). Maturation of the enteric mucosal innate immune system during the postnatal period. Immunol. Rev. 260, 21–34. 10.1111/imr.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidekel Friedlander S. Y., Chu G. C., Snyder E. L., Girnius N., Dibelius G., Crowley D., et al. (2009). Context-dependent transformation of adult pancreatic cells by oncogenic K-Ras. Cancer Cell 16, 379–389. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. (2010). Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C., Spreitzer I., Schroder N. W., Morath S., Lehner M. D., Fischer W., et al. (2002). Cytokine induction by purified lipoteichoic acids from various bacterial species–role of LBP, sCD14, CD14 and failure to induce IL-12 and subsequent IFN-gamma release. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Daniluk J., Liu Y., Chu J., Li Z., Ji B., et al. (2014). Oncogenic K-Ras requires activation for enhanced activity. Oncogene 33, 532–535. 10.1038/onc.2012.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvas C. L., Dahl Jorgensen S. M., Jorgensen S. P., Storgaard M., Lemming L., Hansen M. M., et al. (2019). Fecal microbiota transplantation is superior to fidaxomicin for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 156, 1324–1332 e1323. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2012). Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 100, 1–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida N., Dzutsev A., Stewart C. A., Smith L., Bouladoux N., Weingarten R. A., et al. (2013). Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science 342, 967–970. 10.1126/science.1240527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijssennagger N., Belzer C., Hooiveld G. J., Dekker J., Van Mil S. W., Muller M., et al. (2015). Gut microbiota facilitates dietary heme-induced epithelial hyperproliferation by opening the mucus barrier in colon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 10038–10043. 10.1073/pnas.1507645112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada N., Chen G. Y., Inohara N., Nunez G. (2013). Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 14, 685–690. 10.1038/ni.2608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisawa T., Wood L. D., Itoi T., Takaori K. (2016). Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 388, 73–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski T. M. (2019). The microbiota and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 48, 447–464. 10.1016/j.gtc.2019.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau A. L., Ahern P. P., Griffin N. W., Goodman A. L., Gordon J. I. (2011). Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 474, 327–336. 10.1038/nature10213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. (2010). The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384. 10.1038/ni.1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C. P. (2013). Fecal microbiota transplantation–an old therapy comes of age. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 474–475. 10.1056/NEJMe1214816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K., Ghoshal U. C., Srivastava D., Misra A., Mohindra S. (2014). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is common both among patients with alcoholic and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 14, 280–283. 10.1016/j.pan.2014.05.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Morris J. S., Liu J., Hassan M. M., Day R. S., Bondy M. L., et al. (2009). Body mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA 301, 2553–2562. 10.1001/jama.2009.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Jia H., Cai X., Zhong H., Feng Q., Sunagawa S., et al. (2014). An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 834–841. 10.1038/nbt.2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Fuhler G. M., Bn N., Jose T., Bruno M. J., Peppelenbosch M. P., et al. (2017). Pancreatic cyst fluid harbors a unique microbiome. Microbiome 5:147. 10.1186/s40168-017-0363-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Arze C., Ananthakrishnan A. N., Schirmer M., Avila-Pacheco J., Poon T. W., et al. (2019). Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569, 655–662. 10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis P., Hold G. L., Flint H. J. (2014). The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 661–672. 10.1038/nrmicro3344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. V., Pedersen O. (2016). The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2369–2379. 10.1056/NEJMra1600266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T., Fukaya R., Takamatsu S., Itoyama S., Fukuoka T., Yamada M., et al. (2018). Possible involvement of Enterococcus infection in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis and cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 506, 962–969. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. (2009). The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 229–265. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud D. S., Izard J., Wilhelm-Benartzi C. S., You D. H., Grote V. A., Tjonneland A., et al. (2013). Plasma antibodies to oral bacteria and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large European prospective cohort study. Gut 62, 1764–1770. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A. K., Dubey V., Ghosh A. R. (2016). Obesity: an overview of possible role(s) of gut hormones, lipid sensing and gut microbiota. Metabolism 65, 48–65. 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi K., Nosho K., Sukawa Y., Matsunaga Y., Ito M., Kurihara H., et al. (2015). Association of Fusobacterium species in pancreatic cancer tissues with molecular features and prognosis. Oncotarget 6, 7209–7220. 10.18632/oncotarget.3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira L. O., Zamboni D. S. (2012). NOD1 and NOD2 signaling in infection and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 3:328. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat A. M., Agace W. W. (2014). Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 667–685. 10.1038/nri3738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee T., Hovingh E. S., Foerster E. G., Abdel-Nour M., Philpott D. J., Girardin S. E. (2018). NOD1 and NOD2 in inflammation, immunity and disease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 670, 69–81. 10.1016/j.abb.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagathihalli N. S., Beesetty Y., Lee W., Washington M. K., Chen X., Lockhart A. C., et al. (2014). Novel mechanistic insights into ectodomain shedding of EGFR ligands amphiregulin and TGF-alpha: impact on gastrointestinal cancers driven by secondary bile acids. Cancer Res. 74, 2062–2072. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejman D., Livyatan I., Fuks G., Gavert N., Zwang Y., Geller L. T., et al. (2020). The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science 368, 973–980. 10.1126/science.aay9189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nougayrede J. P., Taieb F., De Rycke J., Oswald E. (2005). Cyclomodulins: bacterial effectors that modulate the eukaryotic cell cycle. Trends Microbiol. 13, 103–110. 10.1016/j.tim.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi A., Graffeo C. S., Zambirinis C. P., Rehman A., Hackman M., Fallon N., et al. (2012). Toll-like receptor 7 regulates pancreatic carcinogenesis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 4118–4129. 10.1172/JCI63606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson C. W., Bassaganya-Riera J., Viladomiu M., Pedragosa M., Guerrant R. L., Roche J. K., et al. (2013). The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in immune responses to enteroaggregative escherichia coli infection. PLoS One 8:e57812. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushalkar S., Hundeyin M., Daley D., Zambirinis C. P., Kurz E., Mishra A., et al. (2018). The pancreatic cancer microbiome promotes oncogenesis by induction of innate and adaptive immune suppression. Cancer Discov. 8, 403–416. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Li Y., Cai Z., Li S., Zhu J., Zhang F., et al. (2012). A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60. 10.1038/nature11450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S., Medzhitov R. (2009). Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 57–63. 10.1038/nrc2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt C., Bergentall M., Greiner T. U., Schaffner F., Ostergren-Lunden G., Petersen L. C., et al. (2012). Tissue factor and PAR1 promote microbiota-induced intestinal vascular remodelling. Nature 483, 627–631. 10.1038/nature10893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme E., Zhang Y., Zhang L., Montiel M., Zoltan M., Dong W., et al. (2019). Tumor microbiome diversity and composition influence pancreatic cancer outcomes. Cell 178, 795–806 e712. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C., Thomas L., Bondarenko I., O'day S., Weber J., Garbe C., et al. (2011). Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2517–2526. 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. J., Prabhu K. S., Vijay-Kumar M. (2014). The microbiome and obesity-an established risk for certain types of cancer. Cancer J. 20, 176–180. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., Duong C. P. M., Alou M. T., Daillere R., et al. (2018). Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97. 10.1126/science.aan3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna S., Van Zuydam N. R., Mahajan A., Kurilshikov A., Vich Vila A., Vosa U., et al. (2019). Causal relationships among the gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids and metabolic diseases. Nat. Genet. 51, 600–605. 10.1038/s41588-019-0350-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saretzki G. (2010). Cellular senescence in the development and treatment of cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 79–100. 10.2174/138161210789941874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe R. F., Jobin C. (2013). The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 800–812. 10.1038/nrc3610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekirov I., Russell S. L., Antunes L. C., Finlay B. B. (2010). Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 90, 859–904. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Lim G., You Z., Ding W., Huang P., Ran C., et al. (2017). Gut microbiota is critical for the induction of chemotherapy-induced pain. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1213–1216. 10.1038/nn.4606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin A., Preidis G. A., Shulman R., Kashyap P. C. (2019). The gut microbiome in adult and pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 256–274. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan A., Corrales L., Hubert N., Williams J. B., Aquino-Michaels K., Earley Z. M., et al. (2015). Commensal bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 350, 1084–1089. 10.1126/science.aac4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita Y., Azuma K., Nonaka Y., Kamada Y., Tomoeda M., Kishida M., et al. (2014). Pancreatic fatty degeneration and fibrosis as predisposing factors for the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 43, 1032–1041. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Voorde J., Sabuncuoglu S., Noppen S., Hofer A., Ranjbarian F., Fieuws S., et al. (2014). Nucleoside-catabolizing enzymes in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures compromise the cytostatic activity of the anticancer drug gemcitabine. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13054–13065. 10.1074/jbc.M114.558924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatanen T., Franzosa E. A., Schwager R., Tripathi S., Arthur T. D., Vehik K., et al. (2018). The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature 562, 589–594. 10.1038/s41586-018-0620-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Dong W., Liu L., Xu M., Wang Y., Liu T., et al. (2019). Interplay between bile acids and the gut microbiota promotes intestinal carcinogenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 58, 1155–1167. 10.1002/mc.22999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M. Y., Shi S., Liang C., Meng Q. C., Hua J., Zhang Y. Y., et al. (2019). The microbiota and microbiome in pancreatic cancer: more influential than expected. Mol. Cancer 18:97. 10.1186/s12943-019-1008-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore S. E., Lamont R. J. (2014). Oral bacteria and cancer. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003933. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambirinis C. P., Levie E., Nguy S., Avanzi A., Barilla R., Xu Y., et al. (2015). TLR9 ligation in pancreatic stellate cells promotes tumorigenesis. J. Exp. Med. 212, 2077–2094. 10.1084/jem.20142162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Sailani M. R., Contrepois K., Zhou Y., Ahadi S., Leopold S. R., et al. (2019). Longitudinal multi-omics of host-microbe dynamics in prediabetes. Nature 569, 663–671. 10.1038/s41586-019-1236-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]