Abstract

Objective

To estimate the effect of oral contraceptives (OC) containing different progestins on parameters of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Patients and methods

Premenopausal women aged 18 or older, who received oral contraceptives containing chlormadinone, cyproterone, drospirenone, levonorgestrel, desogestrel, dienogest, gestodene or norgestimate, for at least 3 months. Outcome variables were changes in plasma lipids, BMI, insulin resistance and plasma glucose. We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for randomized trials and estimated the pooled within-group change in each outcome variable using a random-effects model. We performed subgroup analyses by study duration (<12 months vs ≥12 months) and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) status.

Results

Eighty-two clinical trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria. All progestins (except dienogest) increased plasma TG, ranging from 12.1 mg/dL for levonorgestrel (P < 0.001) to 35.1 mg/dL for chlormadinone (P < 0.001). Most progestins also increased HDLc, with the largest effect observed for chlormadinone (+9.6 mg/dL, P < 0.001) and drospirenone (+7.4 mg/dL, P < 0.001). Meanwhile, levonorgestrel decreased HDLc by 4.4 mg/dL (P < 0.001). Levonorgestrel (+6.8 mg/dL, P < 0.001) and norgestimate (+11.5 mg/dL, P = 0.003) increased LDLc, while dienogest decreased it (–7.7 mg/dL, P = 0.04). Cyproterone slightly reduced plasma glucose. None of the progestins affected BMI or HOMA-IR. Similar results were observed in subgroups defined by PCOS or study duration.

Conclusion

Most progestins increase both TG and HDLc, their effect on LDLc varies widely. OC have minor or no effects on BMI, HOMA-IR and glycemia. The antiandrogen progestins dienogest and cyproterone displayed the most favorable metabolic profile, while levonorgestrel displayed the least favorable.

Key Words: oral contraceptive, lipids, lipoproteins, insulin resistance metabolism

Introduction

Four of every five reproductive-age women in the world have used oral contraceptives (OC) (1). Most OC combine one estrogen with one progestin so there are multiple possible combinations and dosing schemes. Although OC are highly effective for preventing pregnancy, their impact on lipid, lipoprotein, and carbohydrate metabolism is not fully acknowledged. First- and second-generation progestins (desogestrel, gestodene, norgestimate, levonorgestrel, and others) are chemically related to testosterone and may have been undesirable androgenic effects (2). Newer progestins derived from progesterone or spironolactone (cyproterone, chlormadinone, nomegestrol, drospirenone) are expected to result in a more favorable metabolic profile (2).

Estrogens and progestins bind rapidly to nuclear receptors that ultimately regulate the transcription of target genes (2). Estrogens promote insulin secretion, peripheral glucose utilization, synthesis of triglycerides, secretion of HDL, and favor LDL cholesterol uptake and catabolism (3). On the other hand, progesterone induces insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, resembling the physiological state of pregnancy (4). Of note, progestins may bind not only the progesterone receptor, but also the glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid and androgen receptors with different affinities (3). Androgen receptor binding may induce weight gain and higher plasma LDL cholesterol (2). Combined OC containing newer progestins like drospirenone and dienogest are considered anti-androgenic (3).

Given that available studies have used combined OC with distinct combinations and doses of estrogen and progestin, using a wide variety of comparators, the overall impact of each OC on metabolic variables is not easy to assess. For these reasons, we conducted a pre–post effect size meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in order to estimate a consolidated effect of OC containing different progestins on plasma lipid profile, body weight, glycemic levels, and insulin resistance, in adult premenopausal women.

Methods

This meta-analysis was designed and executed according to the guidelines for the preferred reporting items (PRISMA) (5). The questions to be answered by this meta-analysis were: Among premenopausal women: (i) What are the within-person effects of OCs containing different progestins on plasma lipids? (ii) What are the within-person effects of OCs containing different progestins on other metabolically relevant variables (BMI, FPG, HOMA-IR)? (iii) Do the effects of OCs with different progestins differ in women with PCOS vs without PCOS and (iv) Do the effects of OCs on metabolic variables vary by duration of use?

The studies considered for inclusion were those in premenopausal women aged 18 or older, who received oral contraceptives containing chlormadinone, cyproterone, drospirenone, levonorgestrel, desogestrel, dienogest, gestodene or norgestimate, for at least 3 months. The comparator was the baseline value for each outcome variable, namely LDLc, triglycerides (TG), HDLc, HOMA-IR, BMI or fasting plasma glucose (FPG).

Literature search

The search strategy was devised using a combination of keywords and database-specific controlled vocabulary for the concepts of oral contraceptives, lipids and carbohydrates. Additional terminology was added for randomized clinical trials and to eliminate animal studies. Each database, OVID Medline, OVID Embase, LiLACS, and SciELO, was searched from inception, current to July 2020. Please see Supplementary Table 1 (see section on supplementary material given at the end of this article) for a copy of the OVID Medline search. In addition, the reference lists of prior reviews from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were also reviewed for relevant citations that may not have been picked up through the search strategy.

The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017078740) and can be accessed at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=78740.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all randomized clinical trials of OC reporting mean and standard deviation of plasma LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol or triglycerides before and after treatment. The duration of treatment had to be at least 3 months. Only studies in premenopausal women (with or without PCOS) were included. Studies of hormonal replacement therapy, or studies in which OC were used as a treatment for endometriosis were excluded. Trials with incomplete data reporting were also excluded. The inclusion of only randomized clinical trials allowed us to analyze studies with greater methodologic rigor, provision of study intervention and tracking of adherence, all of which improve the ascertainment of exposure status and increase the internal validity of our results.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

Two individual reviewers examined each article for inclusion according to patient characteristics, design, intervention and outcomes. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus. One record of each study was included in case of duplicates. We retrieved data from each trial in a de-identified manner, using a standardized form that included estrogen and progestin received, number of participants in each group, relevant demographics and length of follow-up. We extracted for each study group the mean and standard deviation of the baseline and final values for our study outcomes: LDL cholesterol (LDLc), triglycerides, HDLc, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), BMI and fasting plasma glucose (FPG). Risk of bias was individually evaluated according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Assessment Tool. Each study was considered to have risk of bias (yes or no) in each of six determined categories: allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. We classified studies as follows: If 4–6 domains were ‘yes’: high risk of bias, 2–3 domains: medium risk of bias, 0–1 domains: low risk of bias.

We assessed publication bias by visual assessment of the funnel plot asymmetry, and by performing Begg’s and Egger’s tests when there were at least 5 groups for that particular outcome. In cases in which publication bias was likely, we used the trim and fill method (employing the meta trimfill command in STATA) to correct it.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was used to compare changes in metabolic outcomes associated with the use of OC containing different progestins. The effect measure for the meta-analysis was the unstandardized pooled mean difference (pMD) (where mean difference = final mean of outcome − baseline mean of outcome) for each variable of interest within each study group. For our analyses, we grouped OC containing the same progestin, regardless of the dose. We quantified the degree of inter-study heterogeneity with the I2 statistic and its associated CI. The CI for I2 in most of our study outcomes did not include zero, so we decided to analyze all endpoints using a random-effects model.

Given the heterogeneity between studies in the duration of treatment and study groups, we performed two separate subgroup analyses. First, we performed a comparison by the duration of treatment (less vs more than 12 months), and second, a comparison by the presence of PCOS diagnosis (with PCOS vs without PCOS). In addition, a meta-regression of each outcome vs age and BMI was done for each progestin, adjusting for estrogen dose.

Meta-analyses were executed in RevMan, version 5.0, meta-regression analyses in SPSS, version 23, and trim-and-fill analyses in STATA, version 16.

Results

We included in this review 143 study groups from 82 studies, published between 1979 and July 2020 (Table 1). Of the 82 studies, 53 (64.6%) were conducted in Europe, the average group sample size was 22 (Q1−Q3: 15−30) and the duration ranged from 3 to 24 months. A total of 2354 women were included, their average age was 25.1 and their mean BMI 24.7 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study groups included in the meta-analysis.

| Progestin in OC | First author | Ref. | Country | na | Age | BMI | Follow-up (months) | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlormadinone | Vieira | (6) | Brazil | 20 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 12 | Medium |

| Chlormadinone | Cagnacci | (7) | Italy | 12 | 28.1 | 23.1 | 6 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Vrbikova | (8) | Czech Republic | 12 | 25.4 | 24.4 | 3 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Vexiau | (9) | France | 24 | 25.0 | 20.6 | 12 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Vermeulen | (10) | Belgium | 13 | – | – | 6 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Vermeulen | (10) | Belgium | 17 | – | – | 6 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Venturoli | (11) | Italy | 20 | 22.9 | 22.6 | 12 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Teede | (12) | Australia | 26 | 33.5 | 35.8 | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Sabuncu | (13) | Turkey | 14 | 28.8 | 37.8 | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Rautio | (14) | Finland | 10 | – | – | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Porcile | (15) | Chile | 10 | 25.0 | 23.2 | 24 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Moran | (16) | Australia | 30 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Miccoli | (17) | Italy | 20 | 25.0 | 21.2 | 6 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Mhao | (18) | Iraq | 10 | – | 30.5 | 3 | High |

| Cyproterone | Luque-Ramirez | (19) | Spain | 15 | 23.4 | 29.2 | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Lemay | (20) | Canada | 7 | 20.0 | 33.9 | 6 | High |

| Cyproterone | Kahraman | (21) | Turkey | 26 | 21.0 | 22.8 | 12 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Hutchison | (22) | Australia | 19 | 34.1 | 35.3 | 6 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Hagag | (23) | Israel | 70 | 21.0 | 23.5 | 12 | High |

| Cyproterone | Fugère | (24) | Canada | 40 | 22.7 | 22.1 | 12 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Fugère | (24) | Canada | 33 | 23.2 | 22.2 | 12 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Feng | (25) | China | 41 | 28.6 | 27.8 | 3 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Elter | (26) | Turkey | 20 | 23.5 | 21.8 | 4 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Dardzińska | (27) | Poland | 24 | 24.9 | 24.9 | 4 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Cetinkalp | (28) | Turkey | 33 | – | 24.7 | 4 | High |

| Cyproterone | Bilgir | (29) | Turkey | 20 | 24.3 | 28.2 | 3 | Medium |

| Cyproterone | Leelaphiwat | (30) | Thailand | 16 | 26.9 | 23.0 | 3 | Low |

| Cyproterone | Behboudi-Gandevani | (86) | Iran | 32 | 24.2 | 25.4 | 3 | High |

| Cyproterone | Song | (87) | China | 60 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 3 | High |

| Desogestrel | März | (31) | Germany | 22 | – | – | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Bertolini | (32) | Italy | 20 | – | – | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Miccoli | (17) | Italy | 19 | 26.0 | 21.1 | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Gevers | (33) | Netherlands | 28 | – | – | 12 | Low |

| Desogestrel | März | (34) | Germany | 11 | – | – | 12 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Robinson | (35) | England | 17 | 38.2 | 20.9 | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Steinmetz | (36) | Germany | 23 | 21.5 | 21.1 | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Petersen | (37) | Denmark | 15 | 24.0 | – | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Porcile | (38) | Chile | 9 | – | – | 24 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Porcile | (38) | Chile | 6 | – | – | 24 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Porcile | (15) | Chile | 10 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 24 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Porcile | (15) | Chile | 6 | 22.4 | 23.5 | 24 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Kauppinen-Mäkelin | (39) | Finland | 15 | – | – | 3 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Song | (40) | China | 11 | 32.2 | 20.8 | 3 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Song | (40) | China | 11 | 32.2 | 20.8 | 3 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Cachrimanidou | (41) | Sweden | 13 | 24.0 | – | 12 | High |

| Desogestrel | Cachrimanidou | (41) | Sweden | 7 | 24.0 | – | 12 | High |

| Desogestrel | Kuhl | (42) | Germany | 16 | – | – | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Kuhl | (42) | Germany | 16 | – | – | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Singh | (43) | USA | 23 | 24.9 | – | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | van den Ende | (44) | Netherlands | 20 | 27.5 | 21.3 | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | van der Mooren | (45) | Netherlands | 62 | 26.3 | 22.5 | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Gaspard | (46) | Belgium | 25 | 21.2 | 21.9 | 13 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Klipping | (47) | Netherlands | 30 | 23.7 | 21.7 | 6 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Banaszewska | (48) | Poland | 48 | 24.0 | 22.3 | 3 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Cagnacci | (49) | Italy | 20 | – | 24.1 | 6 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Cagnacci | (7) | Italy | 12 | 27.8 | 23 | 6 | Low |

| Desogestrel | Kriplani | (50) | India | 29 | 22.5 | 26.1 | 6 | Medium |

| Desogestrel | Shahnazi | (51) | Iran | 68 | 30.0 | 28.7 | 3 | Low |

| Dienogest | Wiegratz | (52) | Germany | 25 | 26.1 | 21.9 | 6 | Low |

| Dienogest | Wiegratz | (52) | Germany | 25 | 26.1 | 21.9 | 6 | Low |

| Dienogest | Junge | (53) | Germany | 30 | 28.1 | 23.2 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Gaspard | (46) | Belgium | 25 | 21.5 | 20.2 | 13 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Klipping | (47) | Netherlands | 29 | 23.8 | 21.8 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Özdemir | (54) | Turkey | 32 | 22.7 | 24.3 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Yildizhan | (55) | Turkey | 72 | – | 22.9 | 12 | High |

| Drospirenone | Battaglia | (56) | Italy | 19 | 23.4 | 25.1 | 6 | Low |

| Drospirenone | Fruzzetti | (57) | Italy | 16 | 24.3 | 24.7 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Kriplani | (50) | India | 29 | 22.5 | 27.6 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Machado | (58) | Brazil | 39 | 27.9 | 22.5 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Machado | (58) | Brazil | 38 | 27.7 | 22.3 | 6 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Mohamed | (59) | Egypt | 245 | 30.9 | 25.9 | 12 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Klipping | (60) | Netherlands | 26 | 24.8 | 22.5 | 12 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Klipping | (60) | Netherlands | 21 | 24.4 | 25.5 | 12 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Klipping | (60) | Netherlands | 28 | 24.8 | 22.5 | 12 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Romualdi | (61) | Italy | 15 | 22.9 | 22.06 | 12 | Low |

| Drospirenone | Romualdi | (61) | Italy | 15 | 21.9 | 22.7 | 12 | Low |

| Drospirenone | Kahraman | (21) | Turkey | 26 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 12 | Medium |

| Drospirenone | Orio | (62) | Italy | 50 | 26.4 | 27.0 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Bertolini | (32) | Italy | 20 | – | – | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Kjaer | (63) | Denmark | 16 | 24.7 | – | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Miccoli | (17) | Italy | 18 | 24.0 | 20.9 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Gevers | (33) | Netherlands | 32 | – | – | 12 | Low |

| Gestodene | März | (31) | Germany | 11 | – | – | 12 | Low |

| Gestodene | Robinson | (35) | England | 20 | 38.1 | 22.2 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Steinmetz | (36) | Germany | 21 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 3 | Low |

| Gestodene | Petersen | (64) | Denmark | 20 | 24.5 | 20.9 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Petersen | (37) | Denmark | 19 | 23.0 | – | 3 | Low |

| Gestodene | van der Mooren | (45) | Netherlands | 62 | 26.1 | 22.1 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Endrikat | (65) | Germany | 35 | 24.7 | 22.7 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Endrikat | (65) | Germany | 34 | 25.2 | 22.6 | 6 | Low |

| Gestodene | Merki-Feld | (66) | Switzerland | 8 | 22.0 | – | 3 | Medium |

| Gestodene | Merki-Feld | (66) | Switzerland | 8 | 20.3 | – | 3 | Medium |

| Gestodene | Merki-Feld | (67) | Switzerland | 6 | 22.8 | 21.6 | 3 | High |

| Gestodene | Merki-Feld | (67) | Switzerland | 6 | 20.8 | 24.2 | 3 | High |

| Gestodene | Yildizhan | (55) | Turkey | 71 | – | 22.5 | 12 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (68) | Sweden | 24 | 27.3 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (68) | Sweden | 20 | 23.3 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (68) | Sweden | 23 | 25.0 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (68) | Sweden | 20 | 23.3 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (68) | Sweden | 23 | 25.0 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (69) | Sweden | 25 | – | – | 6 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (69) | Sweden | 25 | – | – | 6 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (69) | Sweden | 24 | – | – | 6 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Larsson-Cohn | (69) | Sweden | 24 | – | – | 6 | High |

| Levonogestrel | März | (34) | Germany | 22 | – | – | 3 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Bertolini | (32) | Italy | 20 | – | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Boonsiri | (70) | Thailand | 59 | 23.8 | – | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Boonsiri | (70) | Thailand | 62 | 23.7 | – | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Boonsiri | (70) | Thailand | 66 | 24.5 | – | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Kjaer | (63) | Denmark | 17 | 24.7 | – | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Notelovitz | (71) | USA | 29 | 25.4 | 23.6 | 12 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Patsch | (72) | USA | 45 | – | – | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Loke | (73) | Singapore | 21 | 25.7 | 20.8 | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Loke | (73) | Singapore | 24 | 25.3 | 21.0 | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Steinmetz | (36) | Germany | 15 | 22.5 | 22.1 | 3 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Janaud | (74) | France | 32 | 26.1 | – | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Kauppinen-Mäkelin | (39) | Finland | 15 | – | – | 3 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Song | (40) | China | 12 | 32.2 | 20.8 | 3 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Kakis | (75) | Canada | 8 | 22.4 | 22.1 | 24 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Reisman | (76) | USA | 155 | 26.8 | 25.2 | 4 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Endrikat | (77) | Germany | 23 | 22.7 | 22.2 | 13 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Endrikat | (77) | Germany | 25 | 24.2 | 22.5 | 13 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Merki-Feld | (66) | Switzerland | 8 | 20.3 | – | 3 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Merki-Feld | (66) | Switzerland | 8 | 22.0 | – | 3 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Merki-Feld | (67) | Switzerland | 6 | 20.8 | 24.2 | 3 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Merki-Feld | (67) | Switzerland | 6 | 22.8 | 21.6 | 3 | High |

| Levonogestrel | Wiegratz | (52) | Germany | 25 | 26.1 | 21.9 | 6 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Scharnagl | (78) | Austria | 44 | 27.0 | 22.3 | 12 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Scharnagl | (78) | Austria | 46 | 26.0 | 22.3 | 12 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Skouby | (79) | Denmark | 22 | 23.5 | 21.1 | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Skouby | (79) | Denmark | 27 | 24.1 | 21.9 | 12 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Skouby | (80) | Denmark | 9 | 22.0 | – | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Elkind-Hirsch | (81) | USA | 20 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Ågren | (82) | Finland | 58 | 29.1 | 22.3 | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Junge | (53) | Germany | 28 | 31.1 | 22.1 | 6 | Medium |

| Levonogestrel | Beasley | (83) | USA | 58 | 25.0 | 26.1 | 3 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Beasley | (83) | USA | 51 | 24.6 | 26.7 | 3 | Low |

| Levonogestrel | Shahnazi | (51) | Iran | 69 | 28.9 | 28.5 | 3 | Low |

| Norgestimate | Janaud | (74) | France | 34 | 24.7 | – | 6 | Medium |

| Norgestimate | Petersen | (64) | Denmark | 17 | 23.5 | 20.3 | 6 | Low |

| Norgestimate | Cibula | (84) | Czech Republic | 14 | 23.2 | 22.1 | 6 | Medium |

| Norgestimate | Essah | (85) | USA | 10 | – | 32.6 | 3 | Low |

| Norgestimate | Hagag | (23) | Israel | 25 | 22.0 | 24.0 | 12 | High |

a n refers to the number of women in the group receiving the progestin of interest.

In all but 2 of the included studies (one with dienogest and one with cyproterone), the estrogen present in the OC was ethinyl estradiol. Among the 143 intervention groups included, the progestin received was chlormadinone acetate in 2, cyproterone acetate in 27, desogestrel in 29, dienogest in 3, drospirenone in 17, gestodene in 17, levonorgestrel in 43 and norgestimate in 5.

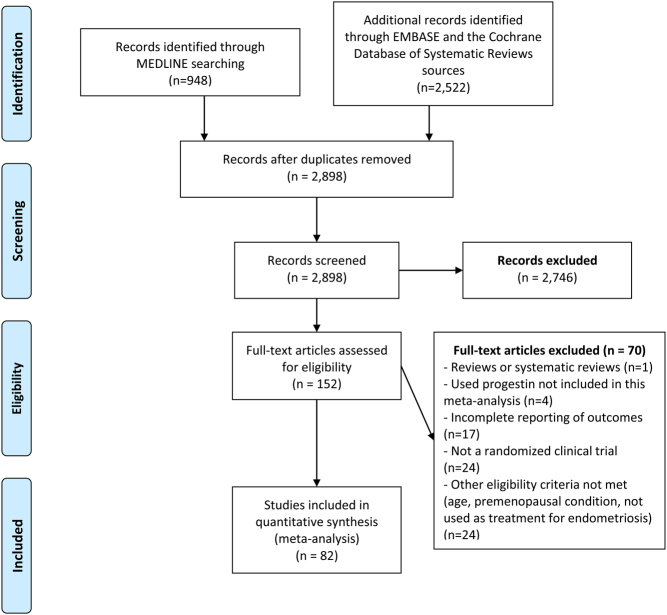

We screened 3470 references through database searching for articles published up to July 2020 (Fig. 1). The searches yielded 948 results from MEDLINE and 2522 from EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Based on this electronic search, we assessed for duplicates, discarded studies that clearly were not related to the interventions or outcomes of interest and downloaded the titles and abstracts of the remaining records. After abstract review, the number of potentially eligible studies was limited to 152. After procuring the full text of these studies, the complete information for baseline and follow-up measurements of study outcomes was evaluated by at least two independent authors. Seventy studies were excluded because they were reviews or systematic reviews, used a progestin not included in this meta-analysis, had incomplete information on outcomes, were not clinical trials, or failed to meet other eligibility criteria (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study.

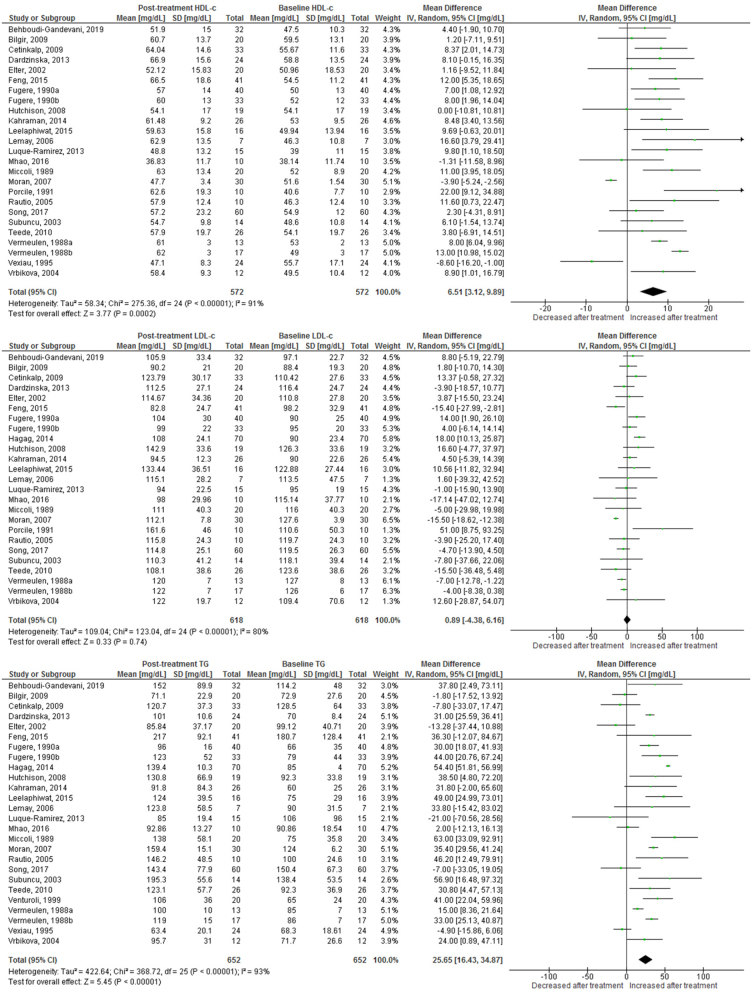

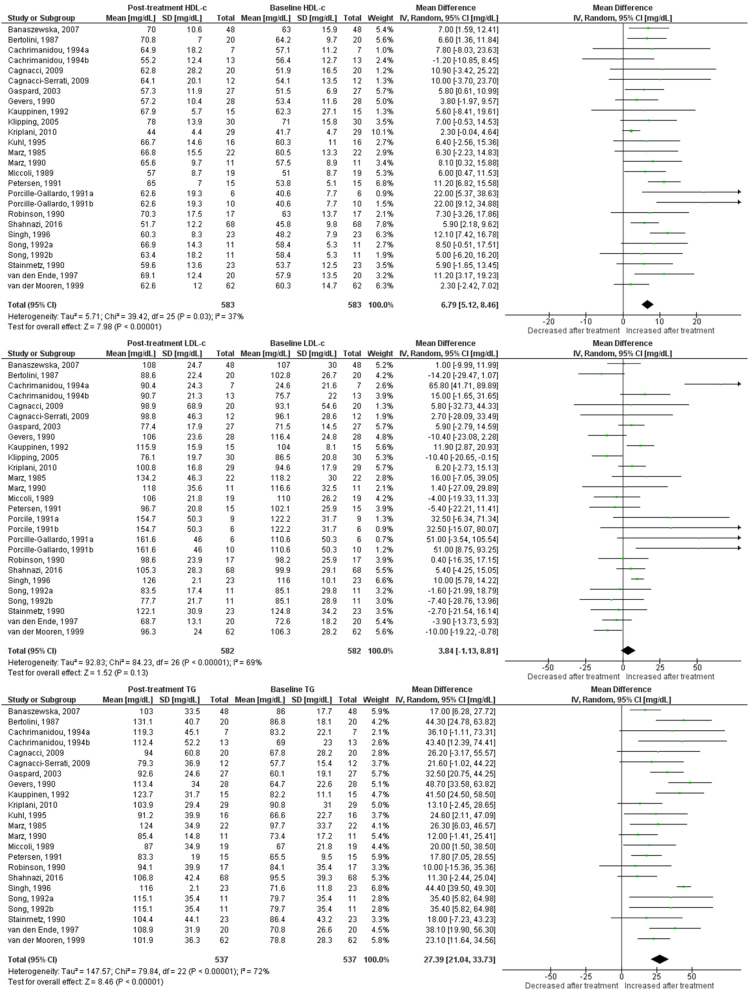

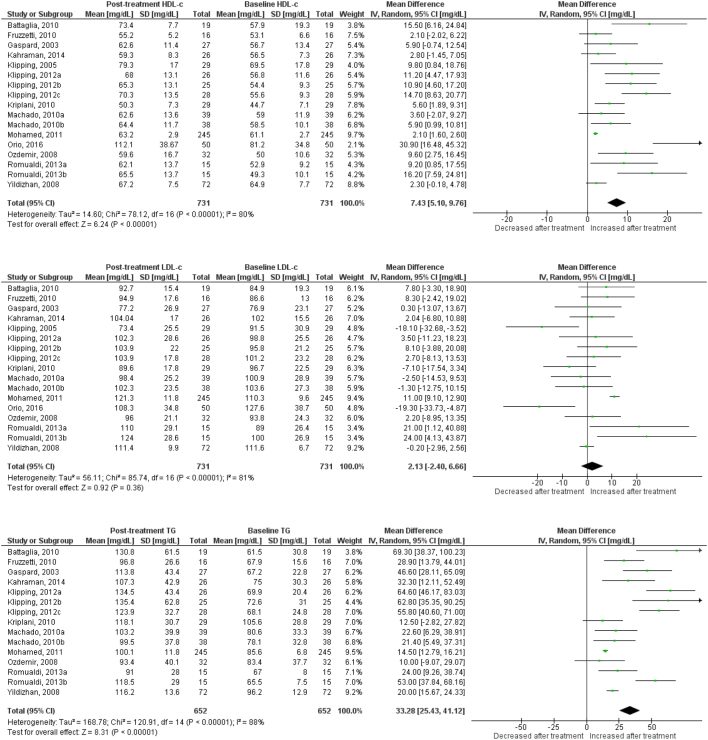

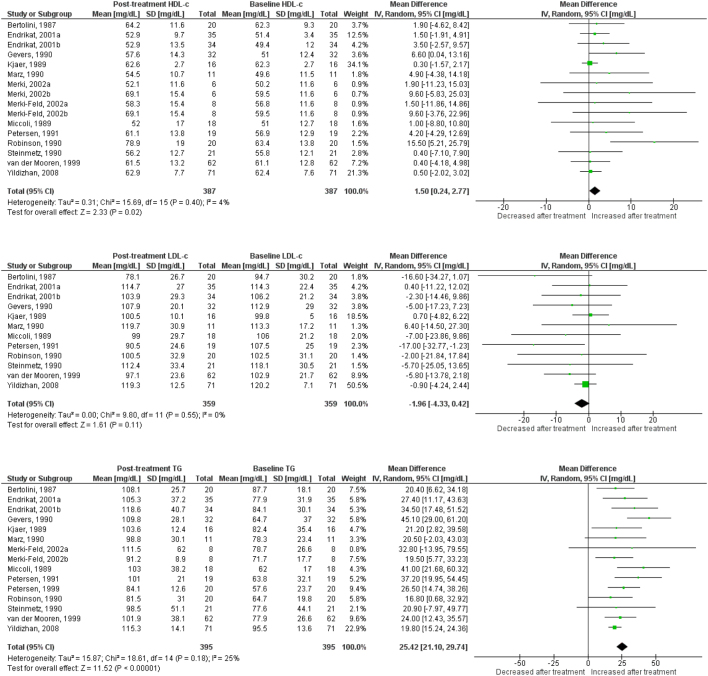

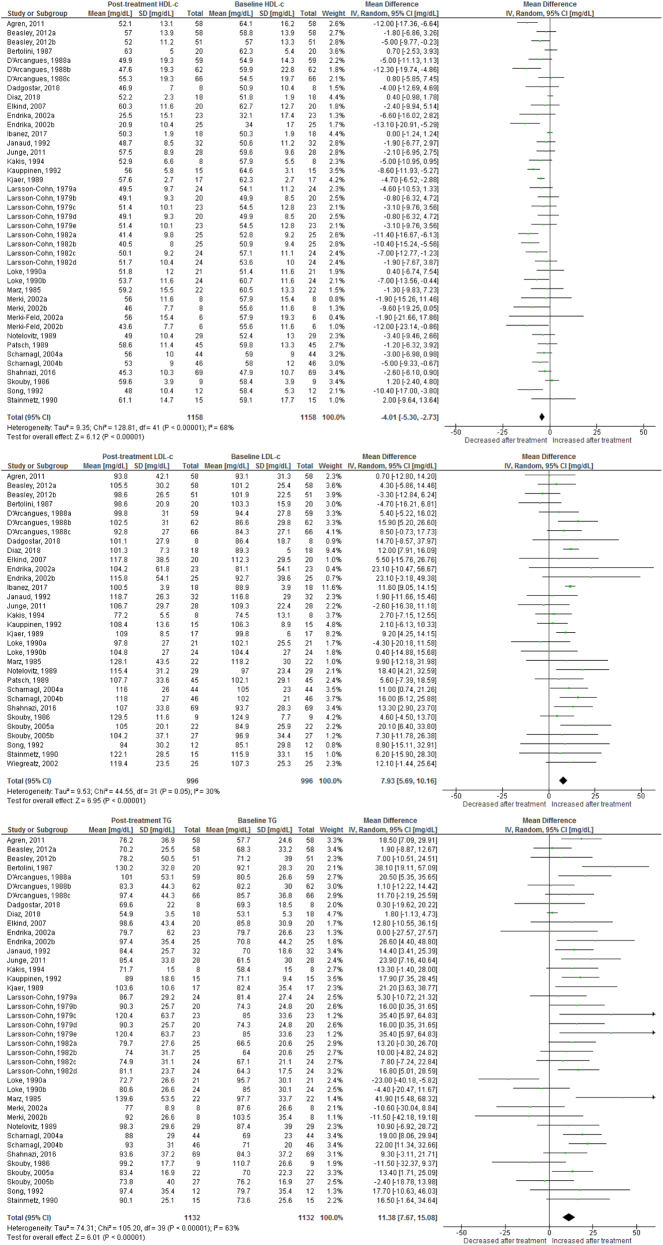

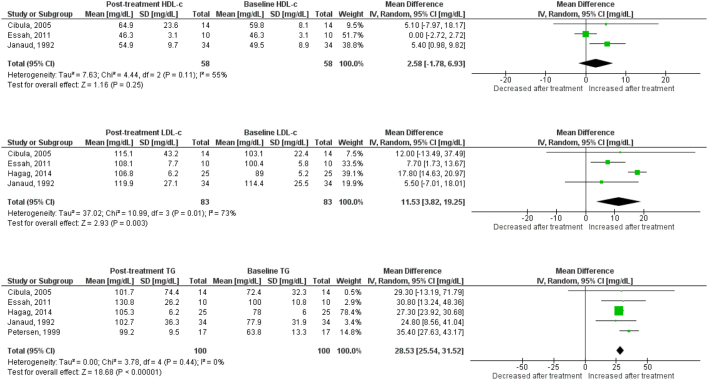

HDL cholesterol

Use of OC containing chlormadinone (pMD: 9.6 mg/dL; 95% CI: 4.5 to 14.7) was associated with significant increases in HDLc. Similar results were found for cyproterone (pMD: 6.5 mg/dL; 95% CI: 3.1 to 9.9, Fig. 2), desogestrel (pMD: 6.8 mg/dL; 95% CI: 5.1 to 8.5, Fig. 3), drospirenone (pMD: 7.4 mg/dL; 95% CI: 5.1 to 9.8, Fig. 4) and to a lesser extent, gestodene (pMD: 1.5 mg/dL; 95% CI: 0.2 to 2.8) (Fig. 5). In the case of cyproterone, meta-regression analyses showed that older age was significantly correlated with smaller increases in HDLc (standardized beta= −0.58, P = 0.045). Contrastingly, levonorgestrel use decreased HDLc (pMD: −4.40 mg/dL; 95% CI: −5.67 to −3.13, Fig. 6). Studies of norgestimate that reported data on HDLc showed no significant changes (Fig. 7).

Figure 2.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of cyproterone in clinical trials.

Figure 3.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of desogestrel in clinical trials.

Figure 4.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of drospirenone in clinical trials.

Figure 5.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of gestodene in clinical trials.

Figure 6.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of levonorgestrel in clinical trials.

Figure 7.

Changes in plasma HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides after use of norgestimate in clinical trials.

LDL cholesterol

An increase in LDLc was observed for levonorgestrel (pMD: 6.8 mg/dL; 95% CI: 4.3 to 9.3), being significantly larger in long-term (>12 months) studies (pMD: 10.2 mg/dL; 95% CI: 6.2 to 14.2; P = 0.04 for interaction) (Table 2). Few studies of norgestimate reported LDLc, but these data showed a significant increase (pMD: 11.5 mg/dL; 95% CI: 3.8 to 19.3) (Fig. 7). LDLc increased significantly in women after cyproterone use only in long-term studies (pMD: 11.7 mg/dL; 95% CI: 3.3 to 20.1, P = 0.003 for interaction) (Table 2). Similarly, LDLc increased only with long-term use for desogestrel (pMD: 22.3 mg/dL; 95% CI: 5.7 to 38.9; P = 0.01 for interaction) and drospirenone (pMD: 6.3 mg/dL; 95% CI: 0.6 to 12.0; P = 0.04 for interaction) (Table 2). By contrast, use of dienogest-containing OC was associated with a significant reduction in LDLc (pMD: −7.7 mg/dL; 95% CI: −14.9 to −0.5).

Table 2.

Changes in metabolic outcomes after use of oral contraceptives containing different progestins, by study duration.

| Outcome | Subgroup (months) | N studies (participants) | pMD (95% CI) | I2 | P-value for difference between subgroups | P-value for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyproterone | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | 14 (300) | −0.13 (−0.45, 0.19) | 0 | 0.35 | 0.66 |

| ≥12 | 2 (50) | 0.23 (−0.46, 0.92) | 0 | 0.84 | ||

| Glucose | <12 | 11 (233) | −1.63 (−3.11, −0.16) | 11 | 0.64 | 0.34 |

| ≥12 | 2 (50) | −3.11 (−9.09, 2.87) | 97 | <0.0001 | ||

| TG | <12 | 18 (347) | 23.7 (15.6, 31.9) | 80 | 0.49 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 6 (213) | 32.6 (8.9, 56.2) | 96 | <0.0001 | ||

| HDL | <12 | 18 (347) | 6.87 (2.64, 11.1) | 93 | 0.94 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 4 (133) | 6.55 (−0.56, 13.7) | 81 | 0.0002 | ||

| LDL | <12 | 18 (347) | −3.07 (−7.83, 1.69) | 66 | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 5 (179) | 11.7 (3.34, 20.2) | 61 | 0.04 | ||

| HOMA | <12 | 9 (216) | −0.32 (−0.85, 0.22) | 97 | 0.64 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 1 (26) | −0.55 (−1.39, 0.29) | NA | NA | ||

| Chlormadinone | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | 1 (12) | 0.20 (−2.45, 2.85) | NA | 0.87 | NA |

| ≥12 | 1 (20) | 0.50 (−2.10, 3.10) | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | <12 | 1 (12) | 0 (−4.04, 5.04) | NA | 0.28 | NA |

| ≥12 | 1 (20) | −4.20 (−10.01, 1.61) | NA | NA | ||

| TG | <12 | 1 (12) | 23.0 (5.80, 40.2) | NA | 0.12 | NA |

| ≥12 | 1 (20) | 56.7 (17.6, 95.8) | NA | NA | ||

| HDL | <12 | 1 (12) | 12.3 (1.01, 23.6) | NA | 0.60 | NA |

| ≥12 | 1 (20) | 8.90 (3.22, 14.6) | NA | NA | ||

| LDL | <12 | 1 (12) | −7.70 (−32.9, 17.5) | NA | 0.53 | NA |

| ≥12 | 1 (20) | −0.76 (−13.7, 12.1) | NA | NA | ||

| HOMA | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Desogestrel | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | 6 (196) | 0.11 (−0.45, 0.67) | 0 | 0.16 | 0.79 |

| ≥12 | 2 (15) | 2.20 (−0.67, 5.07) | 0 | 0.99 | ||

| Glucose | <12 | 9 (281) | 1.53 (−0.56, 3.61) | 58 | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| TG | <12 | 18 (451) | 25.9 (18.6, 33.2) | 74 | 0.40 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 4 (86) | 33.1 (18.0, 48.2) | 71 | 0.008 | ||

| HDL | <12 | 19 (481) | 6.69 (4.94, 8.45) | 33 | 0.73 | 0.08 |

| ≥12 | 7 (102) | 7.63 (2.72, 12.5) | 52 | 0.05 | ||

| LDL | <12 | 18 (465) | 0.19 (−4.37, 4.75) | 58 | 0.001 | |

| ≥12 | 9 (117) | 22.3 (5.66, 38.9) | 80 | <0.0001 | ||

| HOMA | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Drospirenone | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | 5 (146) | −0.07 (−0.87, 0.73) | 0 | 0.25 | 0.96 |

| ≥12 | 4 (128) | −0.69 (−1.04, −0.16) | 0 | 0.58 | ||

| Glucose | <12 | 7 (223) | 0.27 (−2.36, 2.90) | 76 | 0.37 | 0.0003 |

| ≥12 | 2 (271) | 4.71 (−4.60, 14.01) | 98 | <0.0001 | ||

| TG | <12 | 6 (173) | 24.0 (12.4, 35.6) | 61 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| ≥12 | 9 (479) | 38.9 (28.4, 49.4) | 92 | <0.0001 | ||

| HDL | <12 | 8 (252) | 7.91 (4.11, 11.7) | 67 | 0.78 | 0.003 |

| ≥12 | 9 (479) | 7.21 (4.12, 10.3) | 82 | <0.0001 | ||

| LDL | <12 | 8 (252) | −2.96 (−9.71, 3.80) | 62 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| ≥12 | 9 (479) | 6.30 (0.56, 12.0) | 84 | <0.0001 | ||

| HOMA | <12 | 5 (146) | −0.16 (−0.61, 0.28) | 60 | 0.64 | 0.04 |

| ≥12 | 6 (172) | 0.10 (−0.91, 1.11) | NA | NA | ||

| Gestodene | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | 2 (38) | 0.56 (−0.50, 1.63) | 0 | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| ≥12 | 1 (71) | 0.10 (−0.56, 0.76) | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| TG | <12 | 12 (281) | 25.7 (21.1, 30.3) | 0 | 0.79 | 0.69 |

| ≥12 | 3 (114) | 28.0 (11.2, 44. 9) | 77 | 0.01 | ||

| HDL | <12 | 13 (273) | 1.39 (−0.03, 2.81) | 2 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

| ≥12 | 3 (114) | 2.80 (−1.39, 7.00) | 42 | 0.18 | ||

| LDL | <12 | 9 (245) | −3.24 (−6.88, 0.40) | 2 | 0.37 | 0.42 |

| ≥12 | 3 (359) | −1.01 (−4.20, 2.18) | 0 | 0.64 | ||

| HOMA | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Levonorgestrel | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | <12 | 5 (199) | −3.0 (−11.1, 5.09) | 87 | 0.35 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 4 (296) | −8.16 (−15.3, −0.99) | 88 | <0.0001 | ||

| TG | <12 | 25 (650) | 13.7 (9.42, 17.9) | 41 | 0.26 | 0.02 |

| ≥12 | 13 (456) | 9.02 (2.06, 16.0) | 64 | 0.0008 | ||

| HDL | <12 | 28 (707) | −4.19 (−5.73, −2.66) | 58 | 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| ≥12 | 11 (407) | −4.94 (−7.18, −2.70) | 31 | 0.15 | ||

| LDL | <12 | 16 (496) | 5.08 (2.42, 7.75) | 0 | 0.04 | 0.49 |

| ≥12 | 13 (456) | 10.2 (6.15, 14.2) | 21 | 0.23 | ||

| HOMA | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Norgestimate | ||||||

| BMI | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| TG | <12 | 5 (98) | 36.3 (28.3, 44.2) | 56 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| ≥12 | 1 (25) | 27.3 (23.9, 30.7) | NA | NA | ||

| HDL | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA | ||

| LDL | <12 | 4 (81) | 9.02 (5.73, 12.3) | 0 | 0.0002 | 0.86 |

| ≥12 | 1 (25) | 17.8 (14.6, 20.8) | NA | NA | ||

| HOMA | <12 | – | NA | NA | – | NA |

| ≥12 | – | NA | NA | NA |

NA, not applicable, heterogeneity not calculable in this subgroup; NR, not reported.

Plasma triglycerides

Most progestins induced a significant increase in plasma TG. The observed effect was largest for chlormadinone (pMD: 35.1 mg/dL; 95% CI: 3.4 to 66.8), followed by drospirenone (pMD: 33.3 mg/dL; 95% CI: 25.4 to 41.1), norgestimate (pMD: 28.5 mg/dL; 95% CI: 25.5 to 31.5), desogestrel (pMD: 27.4 mg/dL; 95% CI: 21.0 to 33.7), cyproterone (pMD: 25.6 mg/dL; 95% CI: 16.4 to 34.9), gestodene (pMD: 25.4 mg/dL; 95% CI: 21.1 to 29.7) and levonorgestrel (pMD: 12.1 mg/dL; 95% CI: 8.42 to 15.7) (Figs 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Only for norgestimate there was a difference between PCOS status subgroups, the impact on plasma TG was larger for studies in women without PCOS (P = 0.02 for interaction, Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in metabolic outcomes after use of oral contraceptives containing different progestins, in participants with or without polycystic ovary syndrome.

| Outcome | Subgroup | N studies (participants) | pMD (95% CI) | I2 | P-value for difference between subgroups | P-value for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyproterone | ||||||

| BMI | PCOS | 14 (306) | −0.06 (−0.37, 0.24) | 0 | 0.92 | 0.63 |

| No PCOS | 2 (44) | −0.11 (−1.01, 0.78) | 0 | 0.50 | ||

| Glucose | PCOS | 13 (283) | −2.26 (−3.97, −0.56) | 51 | <0.0001 | 0.02 |

| No PCOS | 1 (24) | −6.11 (−3.97, −0.56) | NA | NA | ||

| TG | PCOS | 17 (393) | 25.1 (13.8, 36.4) | 92 | 0.70 | <0.0001 |

| No PCOS | 7 (167) | 28.6 (15.1, 42.0) | 88 | <0.0001 | ||

| HDL | PCOS | 16 (323) | 6.09 (1.91, 10.3) | 84 | 0.49 | <0.0001 |

| No PCOS | 7 (157) | 8.17 (3.95, 12.4) | 85 | <0.0001 | ||

| LDL | PCOS | 17 (393) | 0.08 (−8.01, 8.16) | 83 | 0.80 | <0.0001 |

| No PCOS | 6 (133) | 1.49 (−6.23, 9.22) | 72 | 0.003 | ||

| Chlormadinone | ||||||

| BMI | PCOS | 1 (20) | 0.50 (−2.10, 3.10) | NA | 0.87 | NA |

| No PCOS | 1 (12) | 0.20 (−2.45, 2.85) | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | PCOS | 1 (20) | −4.20 (−10.01, 1.61) | NA | 0.28 | NA |

| No PCOS | 1 (12) | 0 (−4.04, 5.04) | NA | NA | ||

| TG | PCOS | 1 (20) | 56.7 (17.6, 95.8) | NA | 0.12 | NA |

| No PCOS | 1 (12) | 23.0 (5.80, 40.2) | NA | NA | ||

| HDL | PCOS | 1 (20) | 8.90 (3.22, 14.6) | NA | 0.60 | NA |

| No PCOS | 1 (12) | 12.3 (1.01, 23.6) | NA | NA | ||

| LDL | PCOS | 1 (20) | 1.70 (−13.3, 16.7) | NA | 0.53 | NA |

| No PCOS | 1 (12) | −7.70 (−32.9, 17.5) | NA | NA | ||

| Desogestrel | ||||||

| BMI | PCOS | 2 (77) | 0.48 (−0.82, 1.78) | 41 | 0.64 | 0.19 |

| No PCOS | 6 (134) | 0.12 (−0.57, 0.82) | 0 | 0.78 | ||

| Glucose | PCOS | 2 (77) | 3.84 (−2.58, 9.54) | 76 | 0.45 | 0.04 |

| No PCOS | 7 (204) | 0.99 (−1.30, 3.29) | 55 | 0.04 | ||

| TG | PCOS | 2 (77) | 15.7 (6.92, 24.6) | 0 | 0.02 | 0.69 |

| No PCOS | 21 (460) | 28.9 (22.3, 35.4) | 70 | <0.0001 | ||

| HDL | PCOS | 2 (77) | 3.99 (−0.43, 8.41) | 59 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| No PCOS | 24 (506) | 7.26 (5.68, 8.83) | 14 | 0.27 | ||

| LDL | PCOS | 2 (77) | 4.13 (−2.80, 11.1) | 0 | 0.99 | 0.47 |

| No PCOS | 25 (505) | 4.09 (−1.47, 9.65) | 71 | <0.0001 | ||

| Drospirenone | ||||||

| BMI | PCOS | 8 (202) | −0.04 (−0.68, 0.61) | 0 | 0.02 | 0.99 |

| No PCOS | 9 (274) | −0.60 (−1.04, −0.16) | 0 | 0.58 | ||

| Glucose | PCOS | 6 (172) | 0.12 (−2.63, 2.88) | 80 | 0.33 | 0.0001 |

| No PCOS | 3 (322) | 3.55 (−2.76, 9.85) | 95 | <0.0001 | ||

| TG | PCOS | 7 (152) | 32.0 (17.5, 44.6) | 76 | 0.64 | 0.0003 |

| No PCOS | 8 (500) | 35.1 (24.9, 45.2) | 91 | <0.0001 | ||

| HDL | PCOS | 8 (202) | 9.26 (4.84, 13.7) | 75 | 0.30 | 0.0002 |

| No PCOS | 9 (529) | 6.46 (3.65, 9.28) | 78 | <0.0001 | ||

| LDL | PCOS | 8 (202) | 3.44 (−4.29, 11.2) | 68 | 0.99 | 0.003 |

| No PCOS | 9 (529) | 1.30 (−4.70, 7.30) | 87 | <0.0001 | ||

| Norgestimate | ||||||

| BMI | PCOS | 2 (24) | 6.14 (−1.49, 1.77) | 0 | 0.95 | 0.69 |

| No PCOS | 1 (17) | 0.20 (−0.75, 1.15) | NA | NA | ||

| Glucose | PCOS | 2 (24) | −0.16 (−2.45, 2.13) | 0 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| No PCOS | 1 (17) | 1.80 (−1.09, 4.69) | NA | NA | ||

| TG | PCOS | 3 (49) | 27.4 (24.1, 30.8) | 0 | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| No PCOS | 3 (74) | 37.1 (27.5, 46.7) | 74 | 0.02 | ||

| HDL | PCOS | 2 (24) | 0.21 (−2.45, 2.87) | 0 | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| No PCOS | 2 (57) | 8.70 (2.14, 15.3) | 76 | 0.04 | ||

| LDL | PCOS | 3 (49) | 13.0 (4.37, 21.7) | 77 | 0.47 | 0.01 |

| No PCOS | 2 (57) | 9.54 (5.55, 13.5) | 0 | 0.50 |

NA, not applicable, heterogeneity not calculable in this subgroup; NR, not reported.

BMI

Drospirenone caused a small reduction in BMI (pMD: –0.60 kg/m2; 95% CI: –1.04 to –0.16). However, this effect was driven by a study among women without PCOS ((65), pMD: –1.1 kg/m2; 95% CI: –1.7 to –0.5; P = 0.02 for interaction; Table 3). None of the other progestins included in this study had a significant impact on BMI (Figs 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7).

Insulin resistance

None of the studied progestins had a significant impact on HOMA-IR.

Plasma glucose

Women taking cyproterone showed a trivial yet statistically significant decrease in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (pMD: –2.7 mg/dL; 95% CI: –4.8 to –0.7). This reduction was significantly larger in the only cyproterone study in participants without PCOS than in the studies among women with PCOS (P = 0.02 for interaction; Table 3). None of the other progestins showed a significant effect on FPG.

Risk of bias

Out of the 82 studies included, 32 were found to be of low ROB, 40 of medium ROB and 10 of high ROB (Table 1). We performed a sensitivity analysis in which we removed the 10 studies with high ROB and repeated meta-analyses for all OCs and all metabolic outcomes (Supplementary Table 2). Despite minor numerical differences, the significance of modifications in metabolic parameters and the central results of the study remained the same.

Publication bias analyses

Visual examination of funnel plots and formal testing for publication bias with Egger’s and Begg’s tests revealed no indication of publication bias for most outcomes in most progestins (Supplementary Figs 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). Four intervention-outcome pairs showed indication of publication bias: LDLc change after desogestrel, TG change after drospirenone, HDLc change after drospirenone and LDLc change after levonorgestrel. There was a study in which there was a 63 mg/dL increase in LDLc after use of a desogestrel-containing OC (51), this outlier contributed only 2.6% of the weighted mean difference but was largely responsible for an asymmetric funnel plot and significant Egger and Begg’s tests (Supplementary Fig. 2). Change in TG after drospirenone also exhibited an asymmetric funnel plot and significant Egger and Begg’s tests (Supplementary Fig. 3), but asymmetry was mainly due to small studies reporting larger increases in TG. After trim-and-fill analysis for these outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 6), only the modification of HDLc after drospirenone use was affected by publication bias adjustment, the increase in HDLc became smaller and borderline significant.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we estimated the effect of OCs containing different progestins on plasma lipids and other variables related to metabolic health, using data from randomized trials, including premenopausal women. The lipid fractions most influenced by OCs were plasma triglycerides and HDLc. All progestins except dienogest (whose studies did not report changes in TG) induced a significant increase in plasma TG, which ranged numerically between 12.1 mg/dL (levonorgestrel) and 35.1 mg/dL (chlormadinone), consistent with the existing literature from nonrandomized studies.

Most of the newer progestins including chlormadinone, cyproterone, desogestrel and drospirenone induced statistically and clinically significant increases in HDLc, as had been found in previous studies in multiple different populations (88). Even though in observational studies gestodene induced significant increases in HDLc (2), our study showed a numerically marginal increase. Meanwhile, norgestimate did not affect HDLc and levonorgestrel significantly reduced it. Clinical trials of dienogest did not report on HDLc but a previous observational study of patients with endometriosis did show a tendency to lower it (89). On the other hand, the effect of OCs on plasma LDLc was generally more modest, and affected to the greater extent by the duration of use. The above-mentioned observational study of dienogest in endometriosis found no effect of dienogest on lipid profile variables (89), in contrast with our meta-analysis, which showed a 7 mg/dL decrease in LDLc. In accordance with earlier literature (3), levonorgestrel and norgestimate relevantly increased LDLc (7 and 11 mg/dL, respectively) (Table 4). For progestins with an effect on LDLc, this effect was evident mostly for studies of long-term (>12 months) use. A recent randomized cross-over trial that compared OCs containing newer progestins vs levonorgestrel in women with PCOS found the largest positive impact for drospirenone, both in terms of anti-androgenic activity (reduction in free androgen index and acne) and modification of plasma lipids (reduction of LDLc and increase of HDLc) (90).

Table 4.

Summary of changes in metabolic outcomes after use of oral contraceptives containing different progestins in randomized clinical trials.

| Progestin in OC | Metabolic outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDLc | HDLc | TG | BMI | FPG | HOMA-IR | |

| Chlormadinone | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ | NA |

| Cyproterone | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ↓ | ↔ |

| Desogestrel | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Dienogest | ↓ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Drospirenone | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Gestodene | ↔ | ↔↑ | ↑ | ↔ | NA | NA |

| Levonorgestrel | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Norgestimate | ↑ | ↔ | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ | NA |

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDLc, HDL cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance; LDLc, LDL cholesterol; NA, not available; TG, triglycerides.

Perhaps unexpectedly, we found a negligible or non-existent effect of OCs on body weight. Drospirenone use was accompanied by a significant yet small 0.6 kg/m2 reduction in BMI, an effect that was not significant in prior individual observational studies or short-term trials (91). None of the other progestins affected BMI. Though few clinical trials were available, our analyses revealed that cyproterone use was associated with a slight decrease in plasma glucose. HOMA-IR, an index of insulin resistance in the fasting state, was not affected by any of the progestins included in our analyses.

Interestingly, BMI did not appear to be a significant modifier of the metabolic effects for most of the studied OCs, and age was a significant modifier for only one of the outcomes (HDLc change after cyproterone). Thus, the intrinsic pharmacology of each OC seemed to be a greater determinant of its metabolic effect than its interaction with the patient’s age or BMI.

A recent meta-analysis compared the effects of OCs on metabolic parameters, specifically in women with PCOS patients based on the type of progestin and duration of follow-up (88). Similar to our results, the most salient modifications in plasma lipids were increases in both triglycerides and HDLc, with elevations of HDLc occurring sooner than those of TG for most agents. This study also found a significant increase in LDL with use for 12 months or longer for all progestins, something that we also found for levonorgestrel, desogestrel, drospirenone and cyproterone; but not for dienogest, which in fact reduced LDLc. Also, in line with our results, this prior systematic review in PCOS found no impact of OCs on body weight or plasma glucose.

We observed that the selection criteria for inclusion in this review resulted in a sample of studies with a reasonably low risk of bias. Most (72/82, or 87.8%) of the studies included were of low or medium risk of bias, and the exclusion of the remaining 10 studies did not modify the magnitude or significance of the modifications in metabolic parameters estimated in the complete sample.

The main strengths of our study are the inclusion of clinical trials only, the analysis of OCs containing multiple different progestins and the study of various relevant metabolic outcomes. The fact that we restricted our search to studies of premenopausal women receiving OCs at contraceptive doses (as opposed to the doses used for hormonal replacement or for the treatment of endometriosis), may also have contributed to a reduced clinical heterogeneity of the studies. The meta-analysis addresses a relevant question and its results provide useful guidance for clinicians.

The main limitations of our study include the presence of a fair amount of heterogeneity for most outcomes, and the scarcity of high-quality clinical trials reporting on variables related to carbohydrate metabolism like glycemia and HOMA-IR. In order to take into account the very likely existence of between-studies heterogeneity on the observed effects, we synthesized study results using random-effects models for all outcomes. Concerning the effects of OC’s on glycemia and HOMA-IR, it is important for these parameters to be included in future studies of OCs, in order to perform a more complete assessment of the physiological impact of hormonal contraception.

Conclusion

OCs containing different progestins have small, but potentially clinically important effects on the metabolic profile in premenopausal women. Most progestins increase plasma TG and some raise HDLc. In general, OCs have minor or no effects on LDLc, BMI, HOMA-IR and FPG. Baseline lipid and glucose testing should be considered to help determine the most appropriate OC prescription for women.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

R J de Souza has served as an external resource person to the World Health Organization’s Nutrition Guidelines Advisory Group on tra fats, saturated fats, and polyunsaturated fats. The WHO paid for his travel and accommodation to attend meetings from 2012 to 2017 to present and discuss this work. He has also done contract research for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism, and Diabetes, Health Canada, and the World Health Organization for which he received remuneration. He has received speaker’s fees from the University of Toronto, and McMaster Children’s Hospital. He has held grants from the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research, Population Health Research Institute, and Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation as a principal investigator, and is a co-investigator on several funded team grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research. He serves as an independent director of the Helderleigh Foundation (Canada).

Funding

Support for this study came from the Office of the Vice Provost for Research (Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones), School of Medicine, Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. C O Mendivil has received speaker honoraria or has participated in advisory boards for Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Beckman Coulter, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Café de Colombia, Colmédica, Craveri, Jannsen, LabCare Colombia, Merck S A, Novamed, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, PTC Therapeutics, Rochem Biocare, Sanofi and Sicma Pharma. He has been a consultant to Alpina S A, Bavaria S A, Cuquerella Consulting and Team Foods Colombia.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Universidad de los Andes, School of Medicine, for its administrative and logistic support throughout the development of this project.

References

- 1.Daniels K, Mosher WD.Contraceptive methods women have ever used: United States, 1982–2010. National Health Statistics Reports 2013. 14 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitruk-Ware R, Nath A.Characteristics and metabolic effects of estrogen and progestins contained in oral contraceptive pills. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2013. 27 13–24. ( 10.1016/j.beem.2012.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastianelli C, Farris M, Rosato E, Brosens I, Benagiano G.Pharmacodynamics of combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives: effects on metabolism. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 2017. 10 315–326. ( 10.1080/17512433.2017.1271708) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varlamov O, Bethea CL, Roberts CT.Sex-specific differences in lipid and glucose metabolism. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2014. 5 241 ( 10.3389/fendo.2014.00241) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG.PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009. 151 264–9, W64. ( 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieira CS, Martins WP, Fernandes JB, Soares GM, dos Reis RM, de Sá MF, Ferriani RA.The effects of 2 mg chlormadinone acetate/30 mcg ethinylestradiol, alone or combined with spironolactone, on cardiovascular risk markers in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contraception 2012. 86 268–275. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.12.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cagnacci A, Ferrari S, Tirelli A, Zanin R, Volpe A.Route of administration of contraceptives containingdesogestrel/etonorgestrel and insulin sensitivity: a prospective randomized study. Contraception 2009. 80 34–39. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.01.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vrbikova J, Stanicka S, Dvorakova K, Hill M, Vondra K, Bendlová B, Stárka L.Metabolic and endocrine effects of treatment withperoral or transdermal oestrogens in conjunction with peroral cyproterone acetate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Endocrinology 2004. 150 215–223. ( 10.1530/eje.0.1500215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vexiau P, Vexiau-Robert D, Martineau I, Hardy N, Villette JM, Fiet J, Cathelineau G.Metabolic effect at six and twelve months of cyproterone acetate (2 mg) combined with ethinyl estradiol (35 μg) in 31 patients. Hormone and Metabolic Research 1990. 22 241–245. ( 10.1055/s-2007-1004893) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen A, Rubens R.Effects of cyproterone acetate plus ethinylestradiol low dose on plasma androgens and lipids in mildly hirsute or acneic young women. Contraception 1988. 38 419–428. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(8890083-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venturoli S, Marescalchi O, Colombo FM, Macrelli S, Ravaioli B, Bagnoli A, Paradisi R, Flamigni C.A prospective randomized trial comparing low dose flutamide, finasteride, ketoconazole, and cyproterone acetate-estrogen regimens in the treatment of hirsutism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1999. 84 1304–1310. ( 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teede HJ, Meyer C, Hutchison SK, Zoungas S, McGrath BP, Moran LJ.Endothelial function and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: the effects of medical therapy. Fertility and Sterility 2010. 93 184–191. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabuncu T, Harma M, Harma M, Nazligul Y, Kilic F.Sibutramine has a positive effect on clinical and metabolic parameters in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2003. 80 1199–1. ( 10.1016/s0015-0282(0302162-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rautio K, Tapanainen JS, Ruokonen A, Morin-Papunen LC.Effects of metformin and ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate on lipid levels in obese and non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Endocrinology 2005. 152 269–275. ( 10.1530/eje.1.01840) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porcile A, Gallardo E.Long-term treatment of hirsutism: desogestrel compared with cyproterone acetate in oral contraceptives. Fertility and Sterility 1991. 55 877–881. ( 10.1016/s0015-0282(1654291-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran LJ, Meyer C, Hutchison SK, Zoungas S, Teede HJ.Novel inflammatory markers in overweight women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome and following pharmacological intervention. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2010. 33 258–265. ( 10.1007/BF03345790) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miccoli R, Orlandi MC, Fruzzetti F, Giampietro O, Melis G, Ricci C, Bertolotto A, Fioretti P, Navalesi R.Metabolic effects of three new low-dose pills: a six-month experience. Contraception 1989. 39 643–652. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(8990039-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mhao NS, Al-Hilli AS, Hadi NR, Jamil DA, Al-Aubaidy HA.A comparative study to illustrate the benefits of using ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate over metformin in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome 2016. 10 (Supplement 1) S95–S. ( 10.1016/j.dsx.2015.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luque-Ramírez M, Alvarez-Blasco F, Botella-Carretero JI, Martínez-Bermejo E, Lasunción MA, Escobar-Morreale HF.Comparison of ethinylestradiol plus cyproterone acetate versus metformin effects on classic metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007. 92 2453–2461. ( 10.1210/jc.2007-0282) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemay A, Dodin S, Turcot L, Déchêne F, Forest JC.Rosiglitazone and ethinyl estradiol/cyproterone acetate as single and combined treatment of overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome and insulin resistance. Human Reproduction 2006. 21 121–128. ( 10.1093/humrep/dei312) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahraman K, Sükür YE, Atabekoğlu CS, Ateş C, Taşkın S, Cetinkaya SE, Tolunay HE, Ozmen B, Sönmezer M, Berker B.Comparison of two oral contraceptive forms containing cyproterone acetate and drospirenone in the treatment of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2014. 290 321–328. ( 10.1007/s00404-014-3217-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchison SK, Harrison C, Stepto N, Meyer C, Teede HJ.Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care 2008. 31 1427–1432. ( 10.2337/dc07-2265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagag P, Steinschneider M, Weiss M.Role of the combination spironolactone-norgestimate-estrogen in Hirsute women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2014. 59 455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fugère P, Percival-Smith RK, Lussier-Cacan S, Davignon J, Farquhar D.Cyproterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne. A comparative dose-response study of the estrogen component. Contraception 1990. 42 225–234. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9090106-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng W, Jia YY, Zhang DY, Shi HR.Management of polycystic ovarian syndrome with Diane-35 or Diane-35 plus metformin. Gynecological Endocrinology 2016. 32 147–150. ( 10.3109/09513590.2015.1101441) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F.Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Human Reproduction 2002. 17 1729–1737. ( 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1729) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dardzińska JA, Rachoń D, Kuligowska-Jakubowska M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, Płoszyński A, Wyrzykowski B, Lysiak-Szydłowska W.Effects of metformin or an oral contraceptive containing cyproterone acetate on serum C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 concentrations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes 2014. 122 118–1. ( 10.1055/s-0033-1363261) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cetinkalp S, Karadeniz M, Erdogan M, Ozgen G, Saygl F, Ylmaz C.The effects of rosiglitazone, metformin, and estradiol-cyproterone acetate on lean patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinologist 2009. 19 94–97. ( 10.1097/TEN.0b013e3181a58772) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilgir O, Kebapcilar L, Taner C, Bilgir F, Kebapcilar A, Bozkaya G, Yildiz Y, Yuksel A, Sari I.The effect of ethinylestradiol (EE)/cyproterone acetate (CA) and EE/CA plus metformin treatment on adhesion molecules in cases with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Internal Medicine 2009. 48 1193–1199. ( 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2177) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leelaphiwat S, Jongwutiwes T, Lertvikool S, Tabcharoen C, Sukprasert M, Rattanasiri S, Weerakiet S.Comparison of desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol plus spironolactone versus cyproterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2015. 41 402–410. ( 10.1111/jog.12543) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.März W, Jung-Hoffmann C, Heidt F, Gross W, Kuhl H.Changes in lipid metabolism during 12 months of treatment with two oral contraceptives containing 30 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 75 micrograms gestodene or 150 micrograms desogestrel. Contraception 1990. 41 245–258. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9090066-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertolini S, Elicio N, Cordera R, Gapitanio GL, Montagna G, Croce S, Saturnino M, Balestreri R, De Cecco L.Effects of three low-dose oral contraceptive formulations on lipid metabolism. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1987. 66 327–332. ( 10.3109/00016348709103647) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gevers Leuven JA, Dersjant-Roorda MC, Helmerhorst FM, de Boer R, Neymeyer-Leloux A, Havekes L.Estrogenic effect of gestodene- or desogestrel-containing oral contraceptives on lipoprotein metabolism. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990. 163 358–362. ( 10.1016/0002-9378(9090582-r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.März W, Gross W, Gahn G, Romberg G, Taubert HD, Kuhl H.A randomized crossover comparison of two low-dose contraceptives: effects on serum lipids and lipoproteins. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1985. 153 287–293. ( 10.1016/s0002-9378(8580114-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson GE, Bounds W, Mackie IJ, Stocks J, Burren T, Machin SJ, Guillebaud J.Changes in metabolism induced by oral contraceptives containing desogestrel and gestodene in older women. Contraception 1990. 42 263–273. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9090014-m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinmetz A, Bauer K, Jürgensen R, Kaffarnik H.Low-dose oral contraceptives lower plasma levels of apolipoprotein E. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 1990. 37 155–1. ( 10.1016/0028-2243(9090108-d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen KR, Skouby SO, Pedersen RG.Desogestrel and gestodene in oral contraceptives: 12 months’ assessment of carbohydrate and lipoprotein metabolism. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1991. 78 666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porcile A, Gallardo E.Oral contraceptive containing desogestrel in the maintenance of the remission of hirsutism: monthly versus bimonthly treatment. Contraception 1991. 44 533–540. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9190155-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kauppinen-Mäkelin R, Kuusi T, Ylikorkala O, Tikkanen MJ.Contraceptives containing desogestrel or levonorgestrel have different effects on serum lipoproteins and post-heparin plasma lipase activities. Clinical Endocrinology 1992. 36 203–209. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb00959.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song S, Chen JK, Yang PJ, He ML, Li LM, Fan BC, Rekers H, Fotherby K.A cross-over study of three oral contraceptives containing ethinyloestradiol and either desogestrel or levonorgestrel. Contraception 1992. 45 523–532. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9290103-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cachrimanidou AC, Hellberg D, Nilsson S, von Schoulz B, Crona N, Siegbahn A.Hemostasis profile and lipid metabolism with long-interval use of a desogestrel-containing oral contraceptive. Contraception 1994. 50 153–165. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9490051-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhl H, Jung-Hoffmann C, Fitzner M, März W, Gross W.Short- and long-term effects on lipid metabolism of oral contraceptives containing 30 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 150 micrograms desogestrel or 3-keto-desogestrel. Hormone Research 1995. 44 121–125. ( 10.1159/000184610) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh M, Thomas D, Singh R, Saxena BB, Ledger WJ.A triphasic oral contraceptive pill, CTR-05: clinical efficacy and safety. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 1996. 1 285–292. ( 10.3109/13625189609150671) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Ende A, Geurts TB, Kloosterboer HJ.A randomized cross-over study comparing pharmacodynamic and metabolic variables of a new combiphasic and a well-established triphasic oral contraceptive. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 1997. 2 173–180. ( 10.3109/13625189709167473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Mooren MJ, Klipping C, van Aken B, Helmerhorst E, Spielmann D, Kluft C.A comparative study of the effects of gestodene 60 microg/ethinylestradiol 15 microg and desogestrel 150 microg/ethinylestradiol 20 microg on hemostatic balance, blood lipid levels and carbohydrate metabolism. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 1999. 4 (Supplement 2) 27–35. ( 10.3109/13625189909085267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaspard U, Endrikat J, Desager JP, Buicu C, Gerlinger C, Heithecker R.A randomized study on the influence of oral contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol combined with drospirenone or desogestrel on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism over a period of 13 cycles. Contraception 2004. 69 271–278. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.11.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klipping C, Marr J.Effects of two combined oral contraceptives containing ethinyl estradiol 20 microg combined with either drospirenone or desogestrel on lipids, hemostatic parameters and carbohydrate metabolism. Contraception 2005. 71 409–416. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banaszewska B, Pawelczyk L, Spaczynski RZ, Dziura J, Duleba AJ.Effects of simvastatin and oral contraceptive agent on polycystic ovary syndrome: prospective, randomized, crossover trial. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007. 92 456–461. ( 10.1210/jc.2006-1988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cagnacci A, Ferrari S, Tirelli A, Zanin R, Volpe A.Insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism with oral contraceptives containing chlormadinone acetate or desogestrel: a randomized trial. Contraception 2009. 79 111–11. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kriplani A, Periyasamy AJ, Agarwal N, Kulshrestha V, Kumar A, Ammini AC.Effect of oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol combined with drospirenone vs. desogestrel on clinical and biochemical parameters in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contraception 2010. 82 139–146. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahnazi M, Farshbaf-Khalili A, Pourzeinali-Beilankouh S, Sadrimehr F.Effects of second and third generation oral contraceptives on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in overweight and obese women: A randomized triple-blind controlled trial. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 2016. 18 e36982. ( 10.5812/ircmj.36982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiegratz I, Lee JH, Kutschera E, Bauer HH, von Hayn C, Moore C, Mellinger U, Winkler UH, Gross W, Kuhl H.Effect of dienogest-containing oral contraceptives on lipid metabolism. Contraception 2002. 65 223–229. ( 10.1016/s0010-7824(0100310-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Junge W, Mellinger U, Parke S, Serrani M.Metabolic and haemostatic effects of estradiol valerate/dienogest, a novel oral contraceptive: a randomized, open-label, single-centre study. Clinical Drug Investigation 2011. 31 573–584. ( 10.2165/11590220-000000000-00000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Özdemir S, Görkemli H, Gezginç K, Ozdemir M, Kiyici A.Clinical and metabolic effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate and ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2008. 103 44–49. ( 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.05.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yildizhan R, Yildizhan B, Adali E, Yoruk P, Birol F, Suer N.Effects of two combined oral contraceptives containing ethinyl estradiol 30 microg combined with either gestodene or drospirenone on hemostatic parameters, lipid profiles and blood pressure. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009. 280 255–261. ( 10.1007/s00404-008-0907-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Battaglia C, Mancini F, Fabbri R, Persico N, Busacchi P, Facchinetti F, Venturoli S.Polycystic ovary syndrome and cardiovascular risk in young patients treated with drospirenone-ethinylestradiol or contraceptive vaginal ring. A prospective, randomized, pilot study. Fertility and Sterility 2010. 94 1417–1425. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.044) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fruzzetti F, Perini D, Lazzarini V, Parrini D, Gambacciani M, Genazzani AR.Comparison of effects of 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinyl estradiol alone or combined with metformin or cyproterone acetate on classic metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2010. 94 1793–1798. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Machado RB, de Melo NR, Maia H, Jr, Cruz AM.Effect of a continuous regimen of contraceptive combination of ethinylestradiol and drospirenone on lipid, carbohydrate and coagulation profiles. Contraception 2010. 81 102–106. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohamed AM, El-Sherbiny WS, Mostafa WA.Combined contraceptive ring versus combined oral contraceptive (30-μg ethinylestradiol and 3-mg drospirenone). International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2011. 114 145–148. ( 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klipping C, Duijkers I, Fortier MP, Marr J, Trummer D, Elliesen J.Long-term tolerability of ethinylestradiol 20 μg/drospirenone 3 mg in a flexible extended regimen: results from a randomised, controlled, multicentre study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 2012. 38 84–93. ( 10.1136/jfprhc-2011-100214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romualdi D, De Cicco S, Busacca M, Gagliano D, Lanzone A, Guido M.Clinical efficacy and metabolic impact of two different dosages of ethinyl-estradiol in association with drospirenone in normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized study. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2013. 36 636–6. ( 10.1007/BF03346756) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orio F, Muscogiuri G, Giallauria F, Savastano S, Bottiglieri P, Tafuri D, Predotti P, Colarieti G, Colao A, Palomba S.Oral contraceptives versus physical exercise on cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Endocrinology 2016. 85 764–771. ( 10.1111/cen.13112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kjaer A, Lebech AM, Borggaard B, Refn H, Pedersen LR, Schierup L, Bremmelgaard A.Lipid metabolism and coagulation of two contraceptives: correlation to serum concentrations of levonorgestrel and gestodene. Contraception 1989. 40 665–673. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(8990070-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petersen KR, Christiansen E, Madsbad S, Skouby SO, Andersen LF, Jespersen J.Metabolic and fibrinolytic response to changed insulin sensitivity in users of oral contraceptives. Contraception 1999. 60 337–344. ( 10.1016/s0010-7824(9900107-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Endrikat J, Klipping C, Gerlinger C, Ruebig A, Schmidt W, Holler T, Düsterberg B.A double-blind comparative study of the effects of a 23-day oral contraceptive regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 75 microg gestodene and a 21-day regimen with 30 microg ethinyl estradiol and 75 microg gestodene on hemostatic variables, lipids, and carbohydrate metabolism. Contraception 2001. 64 235–241. ( 10.1016/s0010-7824(0100236-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Keller PJ.Effects of two oral contraceptives on plasma levels of nitric oxide, homocysteine, and lipid metabolism. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 2002. 51 1216–1221. ( 10.1053/meta.2002.34038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Merki-Feld GS, Rosselli M, Dubey RK, Jäger AW, Keller PJ.Long-term effects of combined oral contraceptives on markers of endothelial function and lipids in healthy premenopausal women. Contraception 2002. 65 231–236. ( 10.1016/s0010-7824(0100312-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Larsson-Cohn U, Wallentin L, Zador G.Plasma lipids and high density lipoproteins during oral contraception with different combinations of ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel. Hormone and Metabolic Research 1979. 11 437–440. ( 10.1055/s-0028-1092755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larsson-Cohn U, Fåhraeus L, Wallentin L, Zador G.Effects of the estrogenicity of levonorgestrel/ethinylestradiol combinations of the lipoprotein status. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica: Supplement 1982. 105 37–40. ( 10.3109/00016348209155316) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boonsiri B, Kolkijkovinda S, Chutivongse S, Crona N, Medberg M, Gundersen G, Samsioe G, Garza-Flores J, Valles de Bourges V, Juarez-Ayala J.A multicentre comparative study of serum lipids and lipoproteins in four groups of oral combined contraceptive users and a control group of IUD users. World Health Organization. Task Force on Oral Contraceptives. Contraception 1988. 38 605–629. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(8890045-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Notelovitz M, Feldman EB, Gillespy M, Gudat J.Lipid and lipoprotein changes in women taking low-dose, triphasic oral contraceptives: a controlled, comparative, 12-month clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989. 160 1269–1280. ( 10.1016/s0002-9378(8980012-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patsch W, Brown SA, Gotto AM, Jr, Young RL.The effect of triphasic oral contraceptives on plasma lipids and lipoproteins. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989. 161 1396–1401. ( 10.1016/0002-9378(8990703-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loke DF, Ng CS, Samsioe G, Holck S, Ratnam SS.A comparative study of the effects of a monophasic and a triphasic oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Contraception 1990. 42 535–554. ( 10.1016/0010-7824(9090081-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Janaud A, Rouffy J, Upmalis D, Dain MP.A comparison study of lipid and androgen metabolism with triphasic oral contraceptive formulations containing norgestimate or levonorgestrel. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica: Supplement 1992. 156 33–38. ( 10.3109/00016349209156513) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kakis G, Powell M, Marshall A, Woutersz TB, Steiner G.A two-year clinical study of the effects of two triphasic oral contraceptives on plasma lipids. International Journal of Fertility and Menopausal Studies 1994. 39 283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reisman H, Martin D, Gast MJ.A multicenter randomized comparison of cycle control and laboratory findings with oral contraceptive agents containing 100 microg levonorgestrel with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol or triphasic norethindrone with ethinyl estradiol. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999. 181 45–52. ( 10.1016/s0002-9378(9970363-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Endrikat J, Klipping C, Cronin M, Gerlinger C, Ruebig A, Schmidt W, Düsterberg B.An open label, comparative study of the effects of a dose-reduced oral contraceptive containing 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg levonorgestrel on hemostatic, lipids, and carbohydrate metabolism variables. Contraception 2002. 65 215–221. ( 10.1016/s0010-7824(0100316-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scharnagl H, Petersen G, Nauck M, Teichmann AT, Wieland H, März W.Double-blind, randomized study comparing the effects of two monophasic oral contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol (20 microg or 30 microg) and levonorgestrel (100 microg or 150 microg) on lipoprotein metabolism. Contraception 2004. 69 105–113. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skouby SO, Endrikat J, Düsterberg B, Schmidt W, Gerlinger C, Wessel J, Goldstein H, Jespersen J.A 1-year randomized study to evaluate the effects of a dose reduction in oral contraceptives on lipids and carbohydrate metabolism: 20 microg ethinyl estradiol combined with 100 microg levonorgestrel. Contraception 2005. 71 111–117. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.08.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Skouby SO, Mølsted-Pedersen L, Kühl C, Bennet P.Oral contraceptives in diabetic women: metabolic effects of four compounds with different estrogen/progestogen profiles. Fertility and Sterility 1986. 46 858–864. ( 10.1016/s0015-0282(1649825-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elkind-Hirsch KE, Darensbourg C, Ogden B, Ogden LF, Hindelang P.Contraceptive vaginal ring use for women has less adverse metabolic effects than an oral contraceptive. Contraception 2007. 76 348–356. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ågren UM, Anttila M, Mäenpää-Liukko K, Rantala ML, Rautiainen H, Sommer WF, Mommers E.Effects of a monophasic combined oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate and 17β-oestradiol in comparison to one containing levonorgestrel and ethinylestradiol on markers of endocrine function. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 2011. 16 458–467. ( 10.3109/13625187.2011.614363) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beasley A, Estes C, Guerrero J, Westhoff C.The effect of obesity and low-dose oral contraceptives on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Contraception 2012. 85 446–452. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.09.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, Stanicka S, Dvorakova K, Hill M, Skrha J, Zivny J, Skrenkova J.The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenaemia, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Human Reproduction 2005. 20 180–18. ( 10.1093/humrep/deh588) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Essah PA, Arrowood JA, Cheang KI, Adawadkar SS, Stovall DW, Nestler JE.Effect of combined metformin and oral contraceptive therapy on metabolic factors and endothelial function in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2011. 96 501, .e2–504.e2. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.091) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Behboudi-Gandevani S, Abtahi H, Saadat N, Tohidi M, Ramezani Tehrani F.Effect of phlebotomy versus oral contraceptives containing cyproterone acetate on the clinical and biochemical parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Ovarian Research 2019. 12 78 ( 10.1186/s13048-019-0554-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Song J, Ruan X, Gu M, Wang L, Wang H, Mueck AO.Effect of orlistat or metformin in overweight and obese polycystic ovary syndrome patients with insulin resistance. Gynecological Endocrinology 2018. 34 413–417. ( 10.1080/09513590.2017.1407752) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Amiri M, Tehrani FR, Nahidi F, Kabir A, Azizi F, Carmina E.Effects of oral contraceptives on metabolic profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis comparing products containing cyproterone acetate with third generation progestins. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 2017. 73 22–35. ( 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Köhler G, Göretzlehner G, Brachmann K.Lipid metabolism during treatment of endometriosis with the progestin dienogest. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1989. 68 633–635. ( 10.3109/00016348909013283) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Amiri M, Nahidi F, Bidhendi-Yarandi R, Khalili D, Tohidi M, Ramezani Tehrani F.A comparison of the effects of oral contraceptives on the clinical and biochemical manifestations of polycystic ovary syndrome: a crossover randomized controlled trial. Human Reproduction 2020. 35 175–186. ( 10.1093/humrep/dez255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aydin K, Cinar N, Aksoy DY, Bozdag G, Yildiz BO.Body composition in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome: effect of ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone combination. Contraception 2013. 87 358–362. ( 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a