Abstract

Objective: To develop an evidence-based clinical practice guideline (CPG) through a broad-based consensus process on best practices for chiropractic management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) pain.

Design: CPG based on evidence-based recommendations of a panel of experts in chronic MSK pain management.

Methods: Using systematic reviews identified in an initial literature search, a steering committee of experts in research and management of patients with chronic MSK pain drafted a set of recommendations. Additional supportive literature was identified to supplement gaps in the evidence base. A multidisciplinary panel of experienced practitioners and educators rated the recommendations through a formal Delphi consensus process using the RAND Corporation/University of California, Los Angeles, methodology.

Results: The Delphi process was conducted January–February 2020. The 62-member Delphi panel reached consensus on chiropractic management of five common chronic MSK pain conditions: low-back pain (LBP), neck pain, tension headache, osteoarthritis (knee and hip), and fibromyalgia. Recommendations were made for nonpharmacological treatments, including acupuncture, spinal manipulation/mobilization, and other manual therapy; modalities such as low-level laser and interferential current; exercise, including yoga; mind–body interventions, including mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavior therapy; and lifestyle modifications such as diet and tobacco cessation. Recommendations covered many aspects of the clinical encounter, from informed consent through diagnosis, assessment, treatment planning and implementation, and concurrent management and referral. Appropriate referral and comanagement were emphasized.

Conclusions: These evidence-based recommendations for a variety of conservative treatment approaches to the management of common chronic MSK pain conditions may advance consistency of care, foster collaboration between provider groups, and thereby improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: chronic pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, spinal manipulation, chiropractic, clinical practice guideline

Introduction

Pain prevalence has increased among United States adults by 25% from 1998 to 2014, according to a 2019 report, with 41% reporting pain in the period 2013–2014.1 At least 70 million U.S. adults have chronic pain.1,2 Opioid use has risen along with the increase in pain prevalence.1 Visits to health care providers decreased slightly within this same time period, perhaps suggesting that people tend to manage pain with medications rather than provider-based nonpharmacological approaches.1

Authoritative groups, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the American College of Physicians (ACP), have recommended that chronic back pain and other chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) pain be treated initially through nonpharmacological approaches.3

Some experts recommend viewing chronic pain as “a disease entity in itself, rather than merely a symptom of another condition.”4 The International Classification of Disease 11 (ICD-11) has created a new category of “chronic pain,” with the following disorders included: (1) chronic primary pain, which includes disorders such as fibromyalgia or back pain, which is not otherwise classified; (2) chronic cancer pain; (3) chronic post-traumatic and postsurgical pain; (4) chronic neuropathic pain; (5) chronic headache and orofacial pain, which includes temporomandibular joint pain; (6) chronic visceral pain; and (7) chronic MSK pain.5,6

The AHRQ, Institute of Medicine (IOM), and the National Pain Strategy Report6–8 recommend that chronic pain be addressed through the biopsychosocial model, rather than solely through the conventional biomedical model. This includes an emphasis on nonpharmacological and self-management approaches, with pharmacological approaches being secondary.3,6–8

The 2018 and 2020 AHRQ systematic reviews recommend noninvasive, nonpharmacological approaches to several of the most common chronic MSK pain conditions: chronic LBP (CLBP), chronic neck pain, osteoarthritis (OA), fibromyalgia, and chronic tension headache.6,9 A 2018 review in the Journal of Family Practice organized its evidence-based recommendations for common chronic pain conditions by the treatment approach: (1) exercise-based therapies such as yoga and t'ai chi; (2) mind–body therapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based meditation; and (3) complementary modalities such as acupuncture and spinal manipulation.10

The purpose of this project was to develop a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for chiropractic management of chronic MSK pain. The chiropractic profession's primary approach to patient care has traditionally been spinal manipulation, but its scope of practice includes many other nonpharmacological approaches.11 Like medical physicians, chiropractors may not be familiar with many of these approaches other than spinal manipulation, or may not directly employ them with patients. It is important that all health care providers become familiar with evidence-based approaches, within a biopsychosocial model, to help patients manage chronic pain. This is important whether the provider directly employs such approaches, refers the patient to other providers who do, or advises the patient on self-care activities.

In response to the opioid epidemic, nonpharmacological approaches to chronic pain management are expected to become increasingly legitimized.12 Because the public expects Doctors of Chiropractics (DCs) to use such therapies more than medical physicians do, they may be more likely to seek out chiropractic practitioners for these therapies.13 Thus it is important that DCs become familiar with these approaches within the context of the biopsychosocial model. Currently, although there are CPGs addressing a chiropractic approach to LBP,14,15 neck pain,16,17 and headaches18 separately, there is not a single CPG addressing nonpharmacological approaches to more than one type of MSK pain as a primary complaint. The purpose of this project was therefore to develop such a guideline.

Methods

The purpose of the project was to develop an evidence-based CPG through a broad-based consensus process on best practices for chiropractic management of patients with chronic MSK pain.

The development of recommendations followed steps developed and tested in previous projects15,17,19:

Establish a Steering Committee (SC) to perform the core project functions of examining the evidence, developing recommendations based on the best available evidence, and integrating the Delphi panelists' ratings and contributions into the recommendations until a consensus is reached.

Examine the most current CPGs and/or systematic reviews related to each aspect of management.

Identify gaps in the CPG(s) and/or systematic reviews that may form barriers to best practices.

Perform targeted literature searches for the highest available evidence on the gap topics.

Make recommendations on chiropractic management, based on the best available evidence.

Conduct a Delphi consensus process with a panel of practitioners, faculty, and researchers experienced in chronic MSK pain management.

Gather additional feedback from a public posting of the consensus statements.15

Human subject considerations

The lead institution's Institutional Review Board approved the project before it started. All Delphi panelists participated voluntarily and without compensation; they signed an informed consent and agreed to be acknowledged by name in any publication only if they signed a consent to be acknowledged.

Project SC

Of the 11-member SC, 8 were DCs. All of these have extensive experience in chiropractic management of chronic MSK pain and/or knowledge of the evidence base on clinical care of MSK pain. All have held or currently hold leadership positions in chiropractic professional organizations, education and/or research. Three of the DCs are members of the Scientific Council of the Clinical Compass (Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters. Three of the DCs work full time at the Veterans Health Administration (VA); two are full-time faculty at chiropractic institutions; and one DC is cross-trained as a registered nurse (RN). The project director is a DC with a PhD in Preventive Medicine and is also a Certified Health Education Specialist. One SC member is a medical physician (MD) with many years of experience with chronic pain management; one is a psychologist (PhD) who works with chronic pain patients in the VA; and one is a representative for laypeople and also a journal editor with extensive experience with complementary health care. The SC was responsible for identifying, reviewing, and evaluating the evidence underlying the development of the initial seed statements, modifying these statements based on the Delphi panelists' comments, and writing the final article.

Literature search

The literature search focused on the evidence base for nonpharmacological, nonsurgical interventions for chronic MSK pain. A health sciences librarian, working with the SC, conducted the literature search in two stages. The databases we searched were Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PubMed/Medline, because it is unlikely that higher levels of evidence would be found in other databases, but not in these. The search strategy may be accessed in Supplementary Data S1. In addition, we used reference tracking and consulted topic experts on the SC to ensure that relevant articles were not missed.

First stage search

To identify a “seed” document or documents on which to base development of the initial set of recommendations, we conducted two searches: (1) identify the most recent systematic reviews for nonpharmacological treatment of chronic MSK pain and (2) identify CPGs specific to manipulation and manual therapy. We restricted the searches to recent literature rather than doing a comprehensive search, since CPGs should be based on the most current literature, and current systematic reviews were expected to cover earlier studies.20

Search 1 inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Published January 1, 2017, to August 15, 2019.

-

2.

English language.

-

3.

Addressed nondrug, nonsurgical treatment of chronic MSK pain in adults.

-

4.

Systematic reviews/meta-analyses.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Nonrelevant (e.g., addressed interventions outside the scope of U.S. chiropractors or addressed risk factors, but not interventions; did not address chronic MSK pain).

-

2.

Addressed only one type of MSK pain as a primary complaint (e.g., only back pain) and/or one type of intervention (e.g., only CBT), to have a comprehensive seed document to base our recommendations.

-

3.

Included in another systematic review.

Search 2 inclusion criteria

-

1.

Guidelines related to spinal manipulation and/or manual therapy.

-

2.

Published 2016–2019.

-

3.

English language.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Nonrelevant (not CPGs; outside chiropractic scope of practice or not related to chronic MSK pain).

Second stage search

First, we drafted preliminary evidence-based recommendations based on the results of the initial search. In cases where recommendations for specific modalities or procedures were absent due to sparse evidence for procedures commonly used in chiropractic practice (as identified by the current Practice Analysis of Chiropractic11), we did a targeted search of the published literature from the end date of the source systematic review or guideline through 2019. We included guidelines, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, or outcome cohort studies.

Evaluation of the quality of the evidence

We then evaluated the quality of the articles identified in our searches. We evaluated CPGs using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation instrument (AGREE) Global Rating Scale (Table 1).21 We evaluated systematic reviews, RCTs, and cohort studies investigating treatments using modified SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network) checklists, which have been used in other studies by our team.22–24 The SIGN checklist rates the studies as “high quality, low risk of bias,” “acceptable quality, moderate risk of bias,” “low quality, high risk of bias,” or “unacceptable” quality. See Tables 2–4 for details of scoring. We did not assess the quality of other types of studies, simply identifying their design and categorizing them as “lower level.” At least two investigators rated each study and discussed differences in ratings until they reached agreement.

Table 1.

AGREE Global Rating Scale

| Each item is rated on a 1–7 scale from lowest (1) to highest (7) quality; maximum score = 49. Quality assessed as follows: |

| • Divide total score by 7 for average score. |

| • High quality: average 6–7; acceptable quality: average 4–5; unacceptable quality: <4 |

| Process of development |

| 1. Rate the overall quality of the guideline development methods. |

| • Were the appropriate stakeholders involved in the development of the guideline? |

| • Was the evidentiary base developed systematically? |

| • Were recommendations consistent with the literature |

| Presentation style |

| 2. Rate the overall quality of the guideline presentation. |

| • Was the guideline well organized? |

| • Were the recommendations easy to find? |

| Completeness of reporting |

| 3. Rate the completeness of reporting. |

| • Was the guideline development process transparent and reproducible? |

| • How complete was the information to inform decision-making? |

| Clinical validity |

| 4. Rate the overall quality of the guideline recommendations. |

| • Are the recommendations clinically sound? |

| • Are the recommendations appropriate for the intended patients? |

| Overall assessment |

| 5. Rate the overall quality of this guideline. |

| 6. I would recommend this guideline for use in practice. |

| 7. I would make use of a guideline of this quality in my professional decisions. |

Table 2.

Randomized Controlled Trial Modified SIGN Checklist

| Item | Yes/noa | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The study addressed an appropriate and clearly focused question. | |

| 2 | Group assignment was randomized. | |

| 3 | The sample size was justified by a power calculation. | |

| 4 | Investigators were blinded to patients' group assignment. | |

| 5 | Patients were blinded to group assignment. | |

| 6 | Groups were similar at the start of the trial. | |

| 7 | The only difference between groups was the treatment of interest. | |

| 8 | Outcomes were measured in a standard, valid, and reliable way. | |

| 9 | A power calculation was used and required sample size attained. | |

| 10 | An intention to treat analysis was performed. | |

| Total scoreb |

Rating: “Yes” = 1; “No” or unable to tell from the article = 0.

Scoring—sum of items as follows: 9–10 = high quality, low risk of bias; 6–8 = acceptable quality, moderate risk of bias; <6 = low quality, high risk of bias.

Table 3.

Cohort Study Modified SIGN Checklist

| Item | Yes/noa | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question. | |

| 2 | Groups are similar, except for factor of interest. | |

| 3 | Number of people who declined enrollment is stated. | |

| 4 | Likelihood that some patients might have the outcome when enrolled are taken into account in the analysis. | |

| 5 | Attrition in each group stated. | |

| 6 | Dropouts and compliant participants compared by exposure. | |

| 7 | The outcomes are clearly defined. | |

| 8 | Assessment of outcome is made blind to exposure status. | |

| 9 | The method of assessment of exposure is reliable. | |

| 10 | Evidence from other sources is used to demonstrate that the method of outcome assessment is valid and reliable. | |

| 11 | Main potential confounders identified and accounted for in design and analysis. | |

| 12 | Confidence intervals are reported. | |

| Total scoreb |

Rating: “Yes” = 1; “No” or unable to tell from the article = 0.

Scoring—sum of items as follows: 10–12 = high quality, low risk of bias; 6–9 = acceptable quality, moderate risk of bias; <6 = low quality, high risk of bias.

Table 4.

Systematic Review/Meta-Analysis Modified SIGN Checklist

| Item | Yes/noa | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Research question was clearly defined and eligibility criteria listed. | |

| 2 | A comprehensive literature search was conducted. | |

| 3 | At least two people selected studies. | |

| 4 | At least two people extracted data. | |

| 5 | The status of publication was not used as an inclusion criterion. | |

| 6 | The excluded studies were listed. | |

| 7 | The relevant characteristics of included studies were provided. | |

| 8 | The quality of included studies was assessed and reported. | |

| 9 | At least two people assessed quality of the included studies. | |

| 10 | Appropriate methods were used to combine individual study results. | |

| 11 | Likelihood of publication bias was assessed appropriately. | |

| 12 | Conflicts of interest were declared. | |

| Total scoreb |

Rating: “Yes” = 1; “No” or unable to tell from the article = 0.

Scoring—sum of items as follows: 10–12 = high quality, low risk of bias; 6–9 = acceptable quality, moderate risk of bias; <6 = low quality, high risk of bias.

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to assess the overall quality of the evidence.25,* Table 5 summarizes GRADE.25 At least two investigators performed the GRADE assessment independently. If they disagreed, they discussed the assessment and used the majority opinion.

Table 5.

Rating the Quality of Evidence Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation System

| Level of evidence | Quality rating | Explanation of quality rating |

|---|---|---|

| A | High | High level of confidence in the effects of the intervention. |

| • Several high-quality studies with consistent outcomes | ||

| B | Moderate | Confidence in the effects of the intervention may change with future research findings |

| • Only one high-quality study or | ||

| • Several lower quality studies | ||

| C | Low | Confidence in the effects of the intervention is very likely to change with future research findings |

| • All studies have severe limitations | ||

| D | Very Low | Uncertainty about the effects of the intervention |

| • Only expert opinion and/or | ||

| • No research evidence or | ||

| • Very low-quality evidence |

Source: GRADE.103

Development of seed statements

The SC drafted a set of seed statements/concepts encompassing key aspects of the clinical encounter, including informed consent, diagnosis, treatment, concurrent care and co-management, and/or referral. Based on the literature, in addition to statements regarding chronic MSK pain in general, we addressed five of the most common chronic MSK pain conditions: LBP, neck pain, knee and hip OA pain, and fibromyalgia.6 We cited evidence supporting all statements in the text and provided live links to the full text or abstracts in the attached reference list, so that during the consensus process, panelists could conveniently access them to make an evidence-informed rating.

Delphi consensus panel

We sought to recruit a broad-based panel of DCs and other health professionals who had experience with managing patients with chronic MSK pain, valued scientific evidence, and were geographically dispersed throughout the United States. We focused on the United States because practice parameters and reimbursement issues vary among countries. We also made it clear to participants that they must be able to respond in a timely manner to the process, which was conducted by e-mail.

We recruited Delphi panelists by (1) inviting experts who had participated in our previous consensus projects and (2) circulating an invitation through the Clinical Compass board, which includes representatives of the Congress of Chiropractic State Associations, the American Chiropractic Association, the International Chiropractors Association, and the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. The SC reviewed the resulting volunteers, who submitted both a form with their practice characteristics and their CV.

Methodology of the Delphi process

The process was conducted electronically, through e-mail. Throughout the process, panelists remained anonymous, having been assigned an identification number at the beginning. This was done to avoid possible bias, since all raters' comments were shared among the SC and the Delphi panelists. As in all of our previous consensus processes, we used the RAND-UCLA methodology.26 This method employs an ordinal Likert “appropriateness” rating scale in which “appropriate” indicates that the expected patient health benefits exceed expected negative effects by a large enough margin that the recommended action is worthwhile, without considering costs.26 This 1–9 scale is anchored by 1 = “highly inappropriate and 9 = “highly appropriate, with “uncertain” placed over the middle of the scale. Panelists had unlimited space for comments immediately following each statement. They were also instructed to provide citations to support their comments, if possible.

Data management and analysis

The project coordinator entered the ratings data into an SPSS (v. 25) database, and she and the project director computed medians and percentages of agreement. In keeping with the rigorous RAND-UCLA methodology, we set the threshold for consensus at 80% agreement with a median rating of at least seven. This was calculated by categorizing ratings of 1–3 as “inappropriate” (i.e., disagreement with the statement); 4–6 as “uncertain”; and 7–9 as “appropriate” (i.e., agreement). The project coordinator organized the panelists' comments by panelist ID, statement number, and rating to facilitate review. The SC then reviewed the ratings and their accompanying deidentified comments. Taking the comments and supporting evidence into account, the SC then revised the statements that did not reach consensus. The project coordinator provided these revised statements and the deidentified comments to the Delphi panel for another round of rating.

External review: Public comments

Influential organizations such as the AGREE Enterprise recommend incorporating various means for ensuring stakeholder involvement into a guideline development process. We already involved stakeholders in the SC and the Delphi panel. For additional input, we invited public comments on the draft CPG after completing the Delphi process. We used several routes to disseminate this invitation:

Clinical Compass e-mailing list through a MailChimp e-mail blast; this includes the Clinical Compass Board (comprised United States state chiropractic organizations and a number of national chiropractic and academic organizations (about 900 individuals total). It also includes vendors, whose contacts included interested laypersons.

Invitations were sent through the chiropractic organization ChiroCongress to its member associations, representing over 35,000 chiropractors.

Facebook and LinkedIn through the Clinical Compass page, which is open to both health professionals and interested laypersons

Chiropractic Summit e-mail list; this is a national organization of chiropractic groups and individuals.

These routes had some overlap, which served to reinforce the message. In addition, a reminder was sent out 2 weeks after the first invitation. We allowed 30 days for the comment period.

We posted the draft CPG on the Clinical Compass website as a PDF, along with a summary of the background and methodology of the project, as well as the references for all statements. We provided a user-friendly comment form to facilitate response. The project coordinator collected responses. The project director and the SC reviewed and decided how to respond to each comment. If the comments resulted in substantive change, the revised statements were to be recirculated to the Delphi panel to reach consensus.

Results

Literature search and evaluation

First stage search 1: Systematic reviews

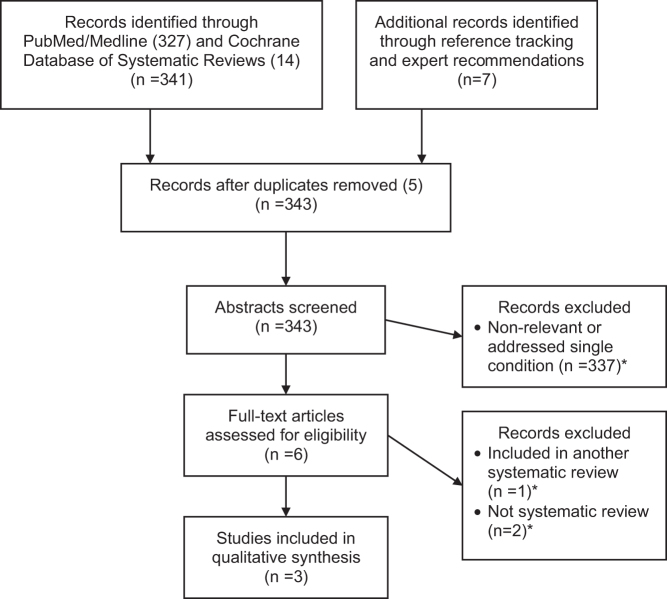

We identified 343 articles (guidelines and systematic reviews/meta-analyses) through PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, reference tracking, and consultation. Figure 1 is the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for the literature search. After applying eligibility criteria, three systematic reviews remained.6,10,27 (Excluded articles are available in Supplementary Data S2.)

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for first-stage literature search. Excluded studies listed in Supplementary Data.

Evaluation

We evaluated two of the articles as high quality6,27 and one as unacceptable quality10; we did not use the unacceptable (low) quality study to support recommendations. We selected one of the two remaining articles, the extensive and high-quality systematic review by the AHRQ on noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain,6 as an appropriate document to serve as the initial framework for our recommendations. We accepted AHRQ's overall rating of the quality of evidence for noninvasive, nonpharmacological interventions as low to moderate and that “there was no evidence suggesting increased risk for serious treatment-related harms for any of the interventions, although data on harms were limited.”6,p.ii We included in our CPG, the five conditions covered in the AHRQ review, which are among the most common causes of chronic MSK pain: LBP, neck pain, chronic tension headache, OA (knee and hip), and fibromyalgia.6

First stage search 2: Clinical practice guidelines

From an initial pool of 147 articles, 23 remained after title screening and 10 remained after abstract/full-text screening. Table 6 lists these CPGs; all were considered high quality, either by our rating with AGREE or a published systematic review of the quality of CPGs on MSK pain using AGREE.28 All the guidelines were single-condition focused: 5 on neck pain,16–18,29,30 4 on LBP,3,14,15,31 and 1 on headaches associated with neck pain.32 There were none on other types of chronic MSK pain.

Table 6.

Clinical Practice Guidelines That Include Manipulation and Manual Therapies, 2016–2019

| Topic | First author | Year | Qualitya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic headache associated with neck pain | Cote.32 | 2019 | H |

| Acute and CLBP | Globe15 | 2016 | Hb |

| Acute and CLBP | Bussieres14 | 2018 | H |

| Acute and CLBP and sciatica | National Guideline Center31 | 2016 | H |

| Acute and CLBP | Qaseem3 | 2017 | H |

| Acute and chronic neck pain | Whalen17 | 2019 | H |

| Acute and chronic neck pain | Cote18 | 2016 | Hb |

| Acute and chronic neck pain | Blanpied30 | 2017 | H |

| Acute and chronic neck pain | Bussieres16 | 2016 | H |

| Acute and chronic neck pain | Bier29 | 2018 | H |

Second stage search

We did a targeted search of the published literature from the end date of the AHRQ review (November 1, 2017) for topics that showed gaps in the evidence for therapies used commonly in chiropractic practice. The interventions we performed searches for were spinal manipulation/manual therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and interferential current, low-level laser (LLL) therapy, and acupuncture. Table 7 summarizes the articles identified after searching for each specific modality from a pool of 348 articles. There were a total of 21 articles: 5 CPGs,14,17,29,32,33 4 RCTS,34–37 and 12 SRs,38–49 as shown by condition and therapy in Table 7. Nine were acceptable quality and 11 were high quality, using the modified SIGN rating checklists shown in Tables 1–3 or, for CPGs, the AGREE scale shown in Table 4).

Table 7.

Evidence from Targeted Search for Interventions 2018–2019, by Condition

| Condition | Design | First author | Quality | Primary intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP | CPG | Bussieres14 | H | SM/MT |

| SR | Wu47 | H | TENS | |

| SR | Almeida38 | A | TENS/IFC | |

| RCT | Barone-Gibbs35 | A | MB/L | |

| RCT | Eklund36 | H | SM | |

| Neck pain | CPG | Whalen17 | H | SM/MT |

| CPG | Bier29 | H | SM/MT | |

| SR | Almeida38 | A | TENS/IFC | |

| RCT | Albornoz-Cabello34 | H | IFC | |

| RCT | Yesil37 | A | TENS/IFC | |

| Headache | CPG | Cote et al.32 | H | SM/MT |

| CPG | Steiner33 | H | Multiple | |

| SR | Gu42 | H | MB/L | |

| Knee OA | SR | Gong41 | A | ACU |

| SR | Sun46 | A | ACU | |

| SR | Stausholm45 | H | LLL | |

| SR | Wysynska48 | A | LLL | |

| SR | Anwer39 | H | MT | |

| Hip OA | SR | Ceballos-Laita40 | H | MT |

| Fibromyalgia | SR | Kim44 | H | ACU |

| SR | Yeh49 | A | LLL | |

| SR | Honda43 | A | LLL/TENS |

ACU, acupuncture; LLL, low-level laser therapy; MB/L, mind–body, psychological therapies or lifestyle counseling; MT, manual therapy; OA, osteoarthritis; SM, spinal manipulation; TENS/IFC, transcutaneous nerve stimulation/interferential current; Multiple = various nonpharmacological therapies, including those already listed and others.

Table 8 summarizes the quality of the evidence from both the AHRQ review and our targeted search (2018–2019). Overall, the evidence was favorable, moderate to low.

Table 8.

Quality of Evidence for Targeted (Procedure/Topic Specific) Searches

| CLBP | CNP | CTTH | KOA | HOA | FM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM/MT | C | B | C | B | C; B | C (MT) |

| C (SM) | ||||||

| TENS/IFC | B | C | B | C | ||

| LLL | C | B | B | B | ||

| ACU | C | C | C | B-C; B | C | |

| MB/L | B-C | B | C |

Strength of evidence rated by the AHRQ systematic review is in bold italics. Strength of evidence is otherwise based on rating of literature published 2018–2019, including clinical practice guidelines, systematic review/meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials. GRADE classifications: (see Table 5 for details): A = high; B = moderate; C = low; D = very low.

ACU, acupuncture; CLBP, chronic low-back pain; CNP, chronic neck pain; CTTH, chronic tension-type headache; FM, fibromyalgia; HOA, hip osteoarthritis; KOA, knee osteoarthritis; LLL, low-level laser therapy; MB/L, mind–body, psychological therapies and lifestyle counseling; MT, manual therapy; SM/MT, spinal manipulation/manual therapy; SM, spinal manipulation; TENS/IFC, transcutaneous nerve stimulation/interferential current.

Delphi process

There were 62 panelists (of 70 invited); 58 were DCs. Ten DCs were cross-trained: five in acupuncture, three in physical therapy (Doctor of Physical Therapy [DPT]), two in medicine (MD), two in nursing (RN), and one in mental health counseling (MA). Eighteen of the DCs had academic master's degrees. One panelist was an MD and three were DPTs. Almost all (57) were practitioners with an average time in practice of 24 years (range 1–48). Sixteen of the panelists worked in the Veterans Administration (VA) and one had a referral arrangement with a local VA. Seven panelists were faculty at chiropractic institutions and seven were faculty at nonchiropractic institutions. Practitioners saw an average of 82 patient visits per week (range: 12–250) and the average estimated proportion of patients with a chief complaint of chronic (>3 months' duration) MSK pain was 61% (range: 15–100). Panelists' locations (58 of 62 responded) represented 31 states plus 1 from Australia and 1 from Canada as follows: five from CA; four each from IA and NY; three each from AZ, KS, MI, OH, and TX; two each from MD, MN, MO, NY, OR, SD, an WA; and one each from CO, HI, IL IN, MA, MS, MT, NC, ND, PA, RI, SC, and TN.

On the first Delphi round, a high level of consensus (from 87% to 100% agreement) was reached on all statements. The panelists had extensive comments, but most were based on clarifying rather than substantively changing the statements. The SC made revisions for the purposes of clarification.

Public comments

We disseminated an invitation for comment very widely through the Clinical Compass board, chiropractic state and national organizations, thus reaching the majority of chiropractors in the United States as well as interested laypeople. Postings on the organization's Facebook page and website were accessed by 209 different people. We received three public comments. All were from DC faculty at U.S. chiropractic colleges; their suggestions were detailed and specific, primarily recommending clarifications in the wording of statements. The SC reviewed their comments and made a number of nonsubstantive changes for clarity in the seed statements; additional Delphi rounds were therefore not required. The final statements are found below.

Chronic pain terminology and definitions

Based on the literature, we prefaced the Delphi consensus process with definitions of key terminology so that panelists would be “on the same page” as they rated the statements.

Chronic pain terminology

Chronic pain: persistent or recurrent pain lasting longer than 3 months (ICD-11 definition)5 or pain present on at least half the days during the past 6 months (National Pain Strategy definition).8

Chronic primary pain: chronic pain in one or more anatomic locations accompanied by significant emotional distress or functional disability and that cannot be better explained by another chronic pain condition.”5

High impact chronic pain: chronic pain that causes enduring restrictions on activities of daily living, work, social, and/or recreational activities.8

Neuropathic pain is identified using the following criteria50,51:

-

1.

Confirmed pain distribution and sensory dysfunction that are neuroanatomically congruent.

-

2.

Confirmed history or presence of a relevant disease or lesion affecting the peripheral or central nervous system.

-

3.

A description of burning, shooting, or pricking pain.

Nociceptive pain is identified using the following criteria51:

-

1.

Confirmed proportionate mechanical/anatomical symptom characteristics.

-

2.

Pain comparable to trauma/pathology and in an area of injury or dysfunction with/without referral.

-

3.

Resolution congruent with anticipated tissue healing time.

-

4.

Pain description typically intermittent and sharp with movement/mechanical aggravation.

-

5.

Pain involves additional symptoms of inflammation (e.g., swelling and redness).

Central sensitization is differentiated from neuropathic and nociceptive pain using these criteria5,51,52:

When neuropathic pain has been excluded, central sensitization pain is differentiated from nociceptive pain as follows52:

-

1.

Pain is out of proportion to the severity of the associated injury or disease.

-

2.

Distribution is diffuse and/or variable, not anatomically congruent with associated injury or disease, with accompanying allodynia or hyperalgesia.

-

3.

Patient is hypersensitive to stimuli such as light, temperature, stress, and emotions.

Other key terminology and abbreviations

Biopsychosocial intervention: a treatment plan that includes at least one physical component (such as spinal manipulation or exercise) and at least one psychological/social component (such as CBT or mindfulness meditation).53

CIH: Complementary and integrative health care.

CBT: Cognitive behavioral therapy, in which unhelpful thought or behavioral patterns are challenged by restructuring thoughts/beliefs and increasing engagement in meaningful activities.

MTI: Maximum Therapeutic Improvement.

Psychological and mind–body interventions focus on interactions among the brain, the rest of the body, the mind, and behavior and the ways in which emotional, mental, social, spiritual, experiential, and behavioral factors affect health. Examples are as follows: psychological therapies such as CBT and mindfulness meditation; physical mind–body therapies such as t'ai chi; and yoga.54

Red flags are signs or symptoms noted in the history or clinical examination that suggests the possibility of serious pathology or illness requiring immediate referral, more extensive evaluation, or co-management, or present a contraindication to an aspect of the proposed treatment plan.55,56

Self-care: An active practice that a person can perform at home independently after being provided with appropriate instruction.57

SMT: Spinal manipulative therapy: usually practiced by DC, doctors of osteopathy (DO), or physical therapists (PT).

Recommendations on Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Patients with Chronic MSK Pain

General considerations for chronic pain management

-

1.

Emphasize the biopsychosocial model. In keeping with the recommendation of organizations such as the AHRQ and the International Society for the Study of Pain (IASP), management of patients with moderate to severe and/or complicated chronic MSK pain is best addressed within a biopsychosocial model rather than the conventional biomedical model.6,58

-

2.

Prioritize self-management and nonpharmacological approaches. Self-management and nonpharmacological therapies should be prioritized over pharmacological approaches whenever possible.3,6–8

a. For patients on prescribed pain medications, co-management with a provider of nonpharmacological approaches may improve outcomes.53

-

3.

Emphasize active interventions. Although passive interventions are useful in the initial stages of management to decrease pain, active interventions—particularly exercise and self-care—should be introduced as soon as possible and emphasized in the management plan.8

a. Passive interventions, both conventional medical approaches (e.g., medication or surgery) and many nonpharmacological approaches (e.g., acupuncture, massage, spinal manipulation, and physical modalities) should be combined with active interventions and self-care (e.g., exercise, healthy diet,59 meditation, yoga, and other lifestyle changes) whenever possible to improve outcomes.38

-

4.

Include both physical and mind–body approaches. For patients reporting moderate to severe chronic pain, a nonpharmacological approach that includes both a physical and mind–body component is recommended.53 These may be administered by the primary treating clinician, or by referral or co-management with an interdisciplinary team.53

-

5.

Identify the neurophysiological type of pain. In keeping with recent advances in the understanding of the physiology of chronic pain, it is important to differentiate patients' chronic pain in terms of its neurophysiology (neuropathic, nociceptive, and central sensitization), because this may affect treatment choices.51,60,61

-

6.

Consider risk stratification, such as the STarT Back risk assessment tool, for new episodes of pain to inform shared decisions about treatment approaches. Patients with low risk of a poor outcome may require a less intensive approach, while those with higher risk may require a more intensive approach incorporating multiple therapies, including psychological.31

Informed consent/risks and benefits

-

1.

Engage the patient in the informed consent process. Informed consent is a process requiring active communication between the patient and clinician. Using clear and understandable terms, the clinician explains the examination procedures, diagnosis, treatment options (including no treatment), and their benefits and risks.15 The clinician should ask the patient if he/she has any questions, and answer them to the patient's satisfaction. The patient must understand this information to make an informed decision.15 The informed consent discussion and the patient's consent to proceed should be recorded in the medical record.

-

2.

Comply with local regulations. Legal requirements may differ by geographic location; clinicians should seek specific advice from local authorities such as their malpractice carrier or state association. Both the American Chiropractic Association (ACA) and the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (ACC) have guidelines on informed consent.17,†

-

3.

Maximize patient safety.

a. Nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain have fewer associated harms than pharmacological interventions, particularly when administered by appropriately trained health professionals.3

b. Carefully assess patients with chronic pain for possible contraindications to manipulation, particularly high-velocity, low-amplitude “thrust” maneuvers (Table 9) and red flags (Table 10).62–64

Table 9.

| System | Condition |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | • Primary or metastatic bone tumors |

| • Severe osteoporosis | |

| • Structural instability (such as unstable spondylolisthesis or postsurgical joint instability) | |

| Inflammatory | • Osteomyelitis |

| • Rheumatoid arthritis in the active systemic stage, or locally if acute inflammation or atlantoaxial instability is present | |

| Neurologic | • Progressive or sudden neurologic deficit |

| • Spinal cord tumors with neurological compromise or requiring medical intervention | |

| Hematologic | • Any unstable bleeding disorders, including high-dose anticoagulant therapy |

| • Unstable aortic aneurysm | |

| Clinician attributes | Inadequate physical examination |

| Inadequate manipulative training |

Table 10.

| Red flags: History | Red flags: Examination6 |

|---|---|

| • Cancer • Confusion/altered consciousness • Connective tissue disease • Osteopenia • Severe nocturnal pain • Significant trauma or infection • Unexplained weight loss • Unexplained/novel neck pain • Visual or speech disturbances • Weakness or loss of sensation • “Worst headache ever” or new headache, unlike any previous |

• Abnormal sensory, motor or deep tendon reflexes • Fever >100°F • Nuchal rigidity • Pain pattern unrelated to movements or activities |

General diagnostic considerations—history, examination, and imaging

History and physical examination

-

1.

Recognize the effect of psychosocial factors on chronic pain physiology. Chronic pain physiology may be differentiated as nociceptive, neuropathic, and/or central sensitization types. However, pain physiology can manifest in individuals through interactions with psychosocial factors. These may be negative, such as mood or sleep disorders or work-related factors (such as hostile work environment, job insecurity, and long work hours65,66) or protective influences such as coping skills and social support.4,67,68

-

2.

Take a thorough pain history. A thorough history of the patient's pain symptoms, previous and concurrent treatment, and psychosocial factors is important to develop an appropriate chiropractic management plan for patients with chronic pain. Components of the history include17 the following:

a. Assessment of red and yellow flag risk factors.

b. Onset of current pain and perceptions about initial precipitating factors.

c. Pain parameters, including type, severity, location, frequency, and duration.

d. Provocative and relieving factors.

e. Review of systems.

f. Previous treatment and response, including medical, surgical, and nonpharmacological.

g. History of past, current, or considered self-care strategies.

h. History of diagnostic tests with results.

-

i

. Current medications and nutraceuticals.

j. Complicating factors/barriers to recovery, including social determinants of health‡

k. Psychological and behavioral health factors (e.g., depression, stress, anxiety, and PTSD).

l. Lifestyle factors such as tobacco use, drugs/alcohol, diet, exercise, and sedentary lifestyle.

-

3.

Consider “yellow flags.” “Yellow Flags” are psychosocial factors that might predict poorer outcomes or prolonged recovery time. They relate to issues such as beliefs about illness and treatment; attitudes and emotional states; and pain behavior.69 Examples include17,69 the following:

a. Belief that activity should be avoided.

b. Pain catastrophizing.70

c. Negative attitude/depression.

d. Work-related stress.

e. Lack of social support.

f. Current compensation and claims issues related to chronic pain.

-

4.

Consider referral for co-management. Patients with psychological factors, which may present an obstacle to compliance with or success of the management plan, may benefit by a referral to a psychologist or behavioral health counselor for further evaluation and/or a trial of CBT.71,72

-

5.

Conduct an appropriately focused physical examination.73 Conduct a physical examination informed by symptoms and health history, including areas/sites of primary and secondary symptoms. Both function and pain should be assessed and include a comprehensive MSK and neuromuscular examination.73

Diagnostic imaging (general considerations and specific recommendations under each condition)

-

1.

Avoid routine use of imaging. Because chronic MSK pain is often multifactorial and may not originate from a local source, imaging evidence is rarely capable of definitively identifying a pain source.73 However, imaging may be necessary if red flags are present and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis after a thorough history and examination are performed.

General treatment considerations

Outcome assessment

-

1.

Use validated Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to assess patient symptoms and characteristics, and to assess progress over time.4 Some Patient-Reported Outcome Measures appropriate for chronic pain chiropractic patients are shown in Table 11.4,17,74

Table 11.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Assessing Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain4

| Pain characteristics | Functional ability | Quality of life | Psychological factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Rating Scale Numeric Rating Scale |

Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)17 | Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | Beck Depression Inventory Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) |

| Visual Analog Scale | Pain Disability Index | Global Well-Being Scale74 | Profile of Mood States |

| Neuropathic Pain Scale Central Sensitization Inventory51,61,101 |

Brief Pain Inventory | EuroQol PROMIS Global Health |

Coping Strategies Questionnaire PTSD Checklist-Specific Version Alcohol/drug dependency: CAGE-AID102 |

Tools for assessing specific types of pain (low back, etc.) are shown in those sections Only tools for assessing general chronic pain rather than those for specific locations (low back, etc.) are shown.

Care pathway

-

1.

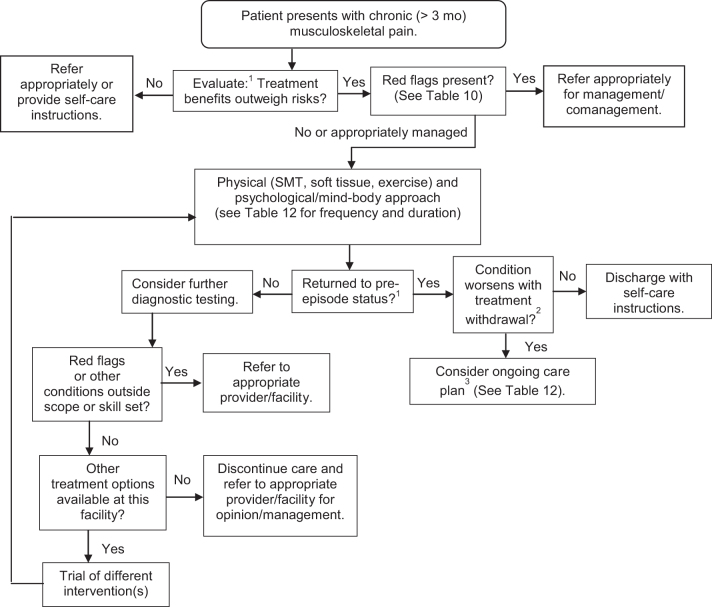

Follow an appropriate care pathway. Figure 2 shows the chiropractic care pathway for a typical adult patient with chronic MSK pain.

FIG. 2.

Care pathway for chiropractic management of adult patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain.14,161Evaluation and re-evaluation components: History; perform focused examination; imaging if warranted (new trauma/symptoms/red flags); patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) (Table 11); pain frequency and intensity; functional ability; quality of life; psychological factors. 2Attempt treatment withdrawal when patient reaches maximum therapeutic improvement. If improvements deteriorate, ongoing care may be necessary to maintain functional status. Withdrawal can be tapered or abrupt. Either instruct patient to return if symptoms recur; or schedule him/her for re-evaluation at regular intervals. 3To document necessity for ongoing care, record: Response to initial treatment (use valid outcome measures); MTI, Maximum Therapeutic Benefit; residual activity limitation; patient's self-care attempts; have alternative treatments been considered or attempted?

Considerations for frequency and duration of treatment

-

1.

Avoid a “curative model” approach. A “curative model” approach is not likely to be successful with chronic pain management. Pain medications are not expected to “cure” chronic pain, but to make it more manageable for the patient. Similarly, nonpharmacological approaches should not be expected to “cure” chronic pain within a specified course of treatment, but may need to be included as part of an individual's ongoing pain management plan.15,17,19,36,75,76 (see Table 12 for details of “Ongoing Management.”)

-

2.

Set appropriate chronic pain management goals. The goals of chronic pain management are different from the goals associated with acute care management. Chronic care goals may include (but are not limited to) the following:

a. Pain control: relief to tolerance.

b. Support or maximize patient's current level of function/ADLs.

c. Reduce/minimize reliance on medication.

d. Maximize patient satisfaction.

e. Maximize patient's engagement in meaningful/pleasurable activities to de-emphasize pain (examples: playing with grandchildren; getting hair done; or going to the park)77,#

f. Minimize exacerbation frequency and/or severity.

g. Minimize further disability.

h. Minimize lost time on the job.

-

3.

Consider patient-specific goals. Patients with chronic MSK pain generally fall into one of these categories:

a. Self-management is sufficient using strategies/procedures such as exercise, ice, heat, and stress reduction.

b. Episodic care is necessary to manage pain. Patients arrange nonpharmacological care on an as-need basis to support their self-care strategies for acute flare-ups, 1–12 visits/episode, followed by release.

c. Scheduled ongoing physician-directed care is necessary to manage pain. Treatment withdrawal results in deterioration36 (Fig. 2 and Table 12).

Table 12.

Visit Frequency and Duration of Care for Chiropractic Management of Chronic (>3 Months) Musculoskeletal Pain15,17

| Type of episode | No. of treatment visits | Duration of care | Re-evaluation period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild exacerbation | 1–6/episode | Per episode | Beginning and end of episode |

| Moderate or severe exacerbation | 2–3/week | 2–4 weeks | Every 2–4 weeks |

| Scheduled interval for ongoing management36,a,b | 1–4/month | Ongoing | Minimum of every 6 visits, or as needed to document changes.c |

Support with documentation of either functional improvement or functional optimization. This may include, but is not limited to the following: (1) substantial symptom recurrence upon treatment withdrawal, (2) minimization/control of pain, (3) maintenance of function and ability to perform, (4) minimization of dependence on interventions with greater risk(s) of adverse events, and (5) maintained or improved work capacity.

Three to four visits per month on an ongoing basis only indicated in exceptional circumstance. One to two visits per month may be necessary if care is supported by a well-documented care

management plan.

Document patient's efforts to comply with self-care recommendations.

Condition-specific diagnosis and treatment recommendations

This guideline includes recommendations for best practices for chiropractic management of some of the most common chronic MSK pain conditions. These are (1) LBP, (2) neck pain, (3) tension headache, (4) knee and hip OA, and (5) fibromyalgia.6

See General Considerations for Chronic Pain Management section for details of history, examination, and red and yellow flags. Specific considerations for each condition are provided below.

1. Chronic LBP

Diagnostic considerations for LBP

-

1.

Develop an evidence-based working diagnosis. Providers should develop evidence-based working diagnoses that describe condition characteristics that will inform a management approach.67,68

-

2.

Consider physiological pain type. Providers are advised to consider whether the likely dominant cause of the LBP is neuropathic, nociceptive, and/or due to central sensitization to determine the most appropriate management strategies.4,5,51,67,68

Diagnostic imaging

-

1.

Avoid routine imaging. Routine imaging is not recommended for patients with nonspecific LBP.14,73 Factors that indicate the need for imaging are15 as follows:

a. Severe and/or progressive neurologic deficits.

b. Suspected anatomical anomaly such as spondylolisthesis.

c. Severe trauma.

d. Other red flags on history or physical examination.

e. Patient shows no improvement after a reasonable course of care.

f. Additional factors vary with location and type of pain.

-

2.

Consider advanced imaging for some cases of radiculopathy. For patients with CLBP accompanied by radiculopathy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans are preferred to plain film radiographs.15 Certain conditions that are not detected on physical examination, such as spinal stenosis, may require MRI to be detected.30

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan. The following are recommended, based on current evidence6,14

a. Physical active interventions:

Exercise

Yoga/qigong (which may also be considered “mind–body” interventions)

Lifestyle advice to stay active; avoid sitting35; manage weight if obese78; and quit smoking78,79

b. Physical passive interventions:

Spinal manipulation/mobilization

Massage

Acupuncture

LLL therapy

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or interferential current may be beneficial as part of a multimodal approach, at the beginning of treatment to assist the patient in becoming or remaining active.38,47

c. Combined active and passive: multidisciplinary rehabilitation

d. Psychological/mind–body interventions80

CBT

Mindfulness-based stress reduction

2. Chronic neck pain

Diagnostic considerations

See General Diagnostic Considerations—History, Examination, and Imaging section

Diagnostic imaging

Consider appropriate circumstances for imaging. According to the American College of Radiology:

-

1.

AP and lateral views of the cervical spine may be appropriate in patients with a history of (1) chronic neck pain with or without trauma; (2) malignancy; or (3) neck surgery.81

-

2.

Diagnostic imaging to identify degeneration is not recommended because it has not been determined to necessarily be a source of pain.82

-

3.

Serial radiographs of the cervical spine are not associated with improved outcomes.83,84

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan for maximum therapeutic effect. The following are recommended, based on current evidence.6

Exercise (range of motion and strengthening).

Exercise combined with manipulation/mobilization.

b. Physical passive interventions:

Massage

Low-level laser

Acupuncture

These modalities may be added as part of a multimodal treatment plan, especially at the beginning, to assist the patient in becoming or remaining active:

Transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS), traction, ultrasound, and interferential current.17,34,37

Yoga

qigong

3. Chronic tension headache

Diagnostic considerations for tension headache

By definition, tension-type headache (TTH) is one that is present at least 15 days each month for more than 3 months. It may be daily and unremitting and may be accompanied by mild nausea.33 TTH is diagnosed by history exclusively, although a focused examination that includes blood pressure should also be conducted. Imaging and other special tests are not indicated unless the history or examination is suggestive of another condition, which may be the underlying cause.33

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan for maximum therapeutic effect. The following are recommended, based on current evidence6:

a. Physical active interventions33

Reassurance that TTH does not indicate presence of a disease.

Advice to avoid triggers.

Exercise (aerobic).

b. Physical passive interventions

Cold packs or menthol gels33

c. Combined active and passive

d. Mind–body interventions33

CBT

Relaxation therapy

Biofeedback

Mindfulness Meditation42

4. Knee and hip OA

Knee OA

Diagnostic considerations for knee OA

-

1.

Rely first on history and physical examination. For knee OA, the diagnosis relies on the history and physical examination findings and is often confirmed with plain radiographs. Laboratory tests are reserved to rule out other diagnoses.86 It is more common in older adults and in the obese (body mass index >30).87,88

Diagnostic imaging

-

1.

Imaging is not typically required. Imaging is not required for typical presentation of knee OA; however, with chronic knee pain, conventional (plain) radiographs should be utilized before other imaging modalities. Considerations of radiographic views are important for optimizing the detection of knee OA, and specifically, weight bearing and patellofemoral views are recommended.89,90

-

2.

Consider advanced imaging in some cases. For additional diagnoses, soft tissues are best imaged with diagnostic ultrasound or MRI without contrast, and bone by CT scan or MRI.89 Radiographic factors for chronic knee pain in which MRI without IV contrast is usually appropriate to include89,90:

a. Negative radiographs

b. Joint effusion

c. Osteochondritis dissecans

d. Loose bodies

e. History of cartilage or meniscal repair

f. Prior osseous injury (i.e., Second fracture and tibial spine avulsion)

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan. The following are recommended, based on current evidence6:

a. Physical active interventions:

Exercise

b. Physical passive interventions:

Manual therapy39

Ultrasound

Acupuncture, using “high dose” (greater treatment frequency, at least 3 × week)41,46

Hip OA

Diagnostic considerations for Hip OA

-

1.

Develop a clinical diagnosis. Hip OA commonly presents as anterior or posterior hip pain, with persistent deep groin pain that is worse with activity.91 The American College of Rheumatology supports clinical diagnosis of hip OA when patients have hip pain, increased pain on internal hip rotation, and concurrent morning stiffness lasting <60 min.92

a. Patients may also have coexisting limitation of flexion with flexion less than or equal to 115° and <15° of internal rotation.93

Diagnostic imaging

-

1.

First consider plain radiographs. According to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria for chronic hip pain, the first line of imaging should be plain radiographs of the hip and pelvis for most, if not all, cases. For OA of the hip, physical examination and radiographs may be better for diagnosis than MRI and have reasonable sensitivity and specificity.92,94

-

2.

Consider advanced imaging for signs of cartilage degeneration. MRI is more sensitive than plain radiographs for detecting early signs of cartilage degeneration. MRI with or without contrast may be indicated if the following are suspected and not confirmed with radiographs92:

a. Impingement

b. Labral tears

c. Pigmented villonodular synovitis or osteochromatosis

d. Arthritis of uncertain type

e. Infection

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan. The following are recommended, based on current evidence6

a. Physical active interventions:

Exercise

b. Physical passive interventions

Manual therapy40

5. Fibromyalgia

Diagnostic considerations for fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is diagnosed primarily from a history of a typical cluster of symptoms—widespread chronic pain, nonrestorative sleep, and fatigue (physical and/or mental)—when other possible causes have been excluded.95

Interventions

-

1.

Consider multiple approaches. Both active and passive, and both physical and mind–body interventions should be considered in the management plan. The following are recommended, based on current evidence6,95,96:

a. Physical active interventions:

Exercise (aerobic and strengthening)

Advice on healthy lifestyle95

Education on the condition95

b. Physical passive interventions:

Spinal manipulation97

Myofascial release97

Acupuncture44

c. Combined active and passive: multidisciplinary rehabilitation

d. Mind–body interventions, including CBT, mindfulness meditation, yoga, and t'ai chi, qigong

Discussion

The management of chronic pain has seen a dramatic shift recently, with nonpharmacological approaches being preferred to pharmacological, due to the opioid epidemic. Therefore, the management of chronic pain patients is not the domain of any one type of provider. In addition, evidence supports the biopsychosocial approach that includes not only multifactorial treatment approach but also a strong emphasis on psychosocial factors, active care, self-care, and patient empowerment.

This guideline is meant to emphasize the use of evidence-based approaches to chronic MSK pain management that help patients become active as soon as possible and empower themselves to manage their pain successfully. It also aims to encourage DCs to work collaboratively with other providers to provide patients with the optimal resources for successfully managing their chronic pain.

A limitation in making such recommendations is that some treatment practices in common use may not have accumulated the highest quality evidence. However, it is important to give practitioners as much guidance as possible, using the best available evidence, as Sackett first described it.98

There are factors that contribute to the relative scarcity of high-quality evidence for nonpharmacological treatments, particularly manual therapies, for chronic pain. One is that randomized controlled trials of nonpharmacological treatments, particularly manual therapies, usually assume a curative model.75 For example, RCTs usually test the hypothesis that a course of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) will result in long-term pain reduction—a curative model—and if it does not, then SMT is considered ineffective.75 However, chronic MSK pain is not medically managed in that same curative model. Analgesics are not expected to function like antibiotics—that is, to “cure” pain after a course of treatment. Although some studies are beginning to approach the topic of chronic pain from a management, rather than curative, approach,36,75,99 currently, the literature is still scarce on optimal treatment parameters, and future studies are important to conduct.

After our project was completed and we were preparing this article, AHRQ published a 2020 update9 to their 2018 review,6 which had formed the foundation of our recommendations. We found that their 2020 update did not substantively alter our recommendations. The fact that AHRQ saw fit to produce an update so quickly emphasizes the importance of the topic of nonpharmacological approaches to chronic MSK pain.

We sought to secure buy-in from the chiropractic profession in developing this guideline by forming a large and broad-based Delphi panel and by disseminating the preliminary recommendations very widely throughout the profession. We hope that the consensus achieved will facilitate their use in chiropractic practice. We also hope that these evidence-based recommendations for a variety of conservative treatment approaches to the management of common chronic MSK pain conditions will foster collaboration between provider groups, and thereby improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cathy Evans for excellence, as usual, in coordinating the complex consensus process and ensuring the highest response rate possible. We also thank Sheryl A. Walters, MLS, for her expertise in the literature search and Robert Vining, DC, DHs, for his thorough and constructive review of the seed statements. The Delphi panelists were an essential part of the development of these recommendations. We thank them for so generously donating their time and expertise to participate: Wayne Bennett, DC, DABCO; Craig R. Benton, DC; Charles L. Blum, DC; Gina Bonavito-Larragoite, DC, FIAMA; Michael S. Calhoun, DC, DACBSP; Wayne H. Carr, DC, CCSP, DACRB, IFMCP; Jeffrey R. Cates, DC, MS; Matthew C. Coté, DC, MS; Monica Curruchich, DC, RN-BSN; John Curtin, MSS, DC, FACO; Vincent DeBono, DC; Mark D. Dehen, DC, FICC; C. Michael DuPriest, PT, DPT, DC, FACO; Paul Ettlinger, DC; James E. Eubanks, MD, DC, MS; Jason T. Evans, DC, FIACN, DIBCN, ABIME; Andrew Fogg, DC, MS, DACRB; David Folweiler, DC; Vinicius Tiepppo Francio, DC, MD; Margaret M. Freihaut, DC; William P. Gallagher, Jr., DC; Derek Golley, DC, MHA; Stephen D. Graham, PT, DPT, OCS; Jason N. Guben, BSc(N), DC; Renee Hunter, DC, RN; Brian James, MD; Jeffrey M. Johnson, DC; Yasmeen Khan, DC, MS, MA; Robert E. Klein, DC; Rick Louis LaMarche, DC; Lawrence J. Larragoite, DC, FIAMA, CFMP; William Lawson, DC, MSc, FIANM(us); Robert Leach, DC, MS, CHES; Duane T. Lowe, DC; Eric Luke, DC, MS; Ralph C. Magnuson, PT, DPT, Dip. MDT; Hans W. Mohrbeck, DC; Scott A. Mooring, DC, CCSP; Jack A. Moses, Jr, DC; Mark Mulak, DC, MBA, MS, DACRB; Marcus Nynas, DC, FICC; Juli Olson, DC, DACM; Colette Peabody, DC, MS; Mariangela Penna, DC; Roger Kevin Pringle, DC, MEd; David C. Radford, DC, MSc; John Rosa, DC, FACC, FICC; Vern Saboe, Jr, DC, FACO; Mark Sakalauskas, DC; Bruce Scott, DC; Christopher R. Sherman, DC, MPH; Scott M. Siegel, DC; Charles A. Simpson, DC, DABCO; Albert Stabile, Jr, DC, FICC, CPCP; Kevin Stemple, RPT, MBA; James P. Stupak, DC; Lisa Thomson, DC, CFMP, CME; Jason Weber, DC, DACRB; Susan Wenberg, MA, DC; John S. Weyand, DC; Clint Williamson, DC; and Morgan Young, DC.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

A grant from the NCMIC Foundation provided partial funding for the project director, and the Clinical Compass provided funding for the project coordinator.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Nahin RL, Sayer B, Stussman BJ, Feinberg TM. Eighteen-year trends in the prevalence of, and health care use for, noncancer pain in the United States: Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Pain 2019;20:796–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clauw DJ, Essex MN, Pitman V, Jones KD. Reframing chronic pain as a disease, not a symptom: Rationale and implications for pain management. Postgrad Med 2019;131:185–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015;156:1003–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review. Rockland, MD: AHRQ, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America. Washington, DC: IOM, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Pain Strategy Task Force. National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population Health-Level Strategy for Pain. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lemmon R, Hampton A. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic pain: What works? J Fam Pract 2018;67:474.;477;480;483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic, 2020. Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tick H, Nielsen A, Pelletier KR, et al. Evidence-based nonpharmacologic strategies for comprehensive pain care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. Explore (NY) 2018;14:177–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Timmons E, Hockenberry JM, Durrance CP. More battles among licensed occupations: Estimating the effects of scope of practice and direct access on the chiropractic, physical therapist, and physician labor market. Mercatus Res 2016:1–29 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low back pain: A guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2018;41:265–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Chiropractic care for low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016;39:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. The treatment of neck pain-associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016;39:523–564 e527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al. Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of patients with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2019;42:635–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cote P, Wong JJ, Sutton D, et al. Management of neck pain and associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur Spine J 2016;25:2000–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farabaugh RJ, Dehen MD, Hawk C. Management of chronic spine-related conditions: Consensus recommendations of a multidisciplinary panel. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010;33:484–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vernooij RW, Sanabria AJ, Sola I, et al. Guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines: A systematic review of methodological handbooks. Implement Sci 2014;9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brouwers M, Kho M, Browman GP, et al. Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:E839–E842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harbour R, Lowe G, Twaddle S. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: The first 15 years (1993–2008). J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2011;41:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hawk C, Minkalis AL, Khorsan R, et al. Systematic review of nondrug, nonsurgical treatment of shoulder conditions. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2017;40:293–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hawk C, Minkalis A, Webb C, et al. Manual interventions for musculoskeletal factors in infants with suboptimal breastfeeding: A scoping review. Evid Based Integr Med 2018;23:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fitch K, Bernstein S, Aquilar MS, et al. The RAND UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Falla D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin I, Wiles LK, Waller R, et al. Poor overall quality of clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters WGM, Staal JB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Phys Ther 2018;98:162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: Revision 2017. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:A1–A83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Guideline Center. Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cote P, Yu H, Shearer HM, et al. Non-pharmacological management of persistent headaches associated with neck pain: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario protocol for traffic injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain 2019;23:1051–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, et al. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition): On behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: The Global Campaign against Headache. J Headache Pain 2019;20:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albornoz-Cabello M, Perez-Marmol JM, Barrios Quinta CJ, et al. Effect of adding interferential current stimulation to exercise on outcomes in primary care patients with chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2019;33:1458–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barone Gibbs B, Hergenroeder AL, Perdomo SJ, et al. Reducing sedentary behaviour to decrease chronic low back pain: The stand back randomised trial. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eklund A, Jensen I, Lohela-Karlsson M, et al. The Nordic Maintenance Care program: Effectiveness of chiropractic maintenance care versus symptom-guided treatment for recurrent and persistent low back pain-A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yesil H, Hepguler S, Dundar U, et al. Does the use of electrotherapies increase the effectiveness of neck stabilization exercises for improving pain, disability, mood, and quality of life in chronic neck pain? A Randomized, Controlled, Single Blind Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:E1174–E1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Almeida CC, Silva V, Junior GC, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and interferential current demonstrate similar effects in relieving acute and chronic pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther 2018;22:347–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anwer S, Alghadir A, Zafar H, Brismee JM. Effects of orthopaedic manual therapy in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2018;104:264–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ceballos-Laita L, Estebanez-de-Miguel E, Martin-Nieto G, et al. Effects of non-pharmacological conservative treatment on pain, range of motion and physical function in patients with mild to moderate hip osteoarthritis. A systematic review. Complement Ther Med 2019;42:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gong Z, Liu R, Yu W, et al. Acutherapy for knee osteoarthritis relief in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019;2019:1868107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gu Q, Hou JC, Fang XM. Mindfulness meditation for primary headache pain: A meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018;131:829–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Honda Y, Sakamoto J, Hamaue Y, et al. Effects of physical-agent pain relief modalities for fibromyalgia patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag 2018;2018:2930632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim J, Kim SR, Lee H, Nam DH. Comparing verum and sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019;2019:8757685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stausholm MB, Naterstad IFM, Joensen J, et al. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sun N, Tu JF, Lin LL, et al. Correlation between acupuncture dose and effectiveness in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Acupunct Med 2019;37:261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu LC, Weng PW, Chen CH, et al. Literature review and meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in treating chronic back pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018;43:425–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wyszynska J, Bal-Bochenska M. Efficacy of high-intensity laser therapy in treating knee osteoarthritis: A first systematic review. Photomed Laser Surg 2018;36:343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]