Abstract

Background & Aims

Female sex is associated with lower incidence and improved clinical outcomes for most cancer types including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The mechanistic basis for this sex difference is unknown. We hypothesized that estrogen signaling may be responsible, despite the fact that PDAC lacks classic nuclear estrogen receptors.

Methods

Here we used murine syngeneic tumor models and human xenografts to determine that signaling through the nonclassic estrogen receptor G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) on tumor cells inhibits PDAC.

Results

Activation of GPER with the specific, small molecule, synthetic agonist G-1 inhibited PDAC proliferation, depleted c-Myc and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and increased tumor cell immunogenicity. Systemically administered G-1 was well-tolerated in PDAC bearing mice, induced tumor regression, significantly prolonged survival, and markedly increased the efficacy of PD-1 targeted immune therapy. We detected GPER protein in a majority of spontaneous human PDAC tumors, independent of tumor stage.

Conclusions

These data, coupled with the wide tissue distribution of GPER and our previous work showing that G-1 inhibits melanoma, suggest that GPER agonists may be useful against a range of cancers that are not classically considered sex hormone responsive and that arise in tissues outside of the reproductive system.

Keywords: Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, PDAC, G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor, GPER

Abbreviations used in this paper: DMEM, Dulbecco modified Eagle medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GPER, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor; HPDE, human pancreatic ductal epithelial; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1

See editorial on page 862.

Summary.

Pharmacologic activation of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) has been shown to inhibit multiple cancer types. Here we demonstrate that activation of GPER inhibits models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and that activation of GPER has combinatorial effects with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

For many cancers, incidence and age-adjusted mortality rates are lower in female patients than in male patients, suggesting that biological differences between the sexes influence tumor initiation, progression, and response to modern therapeutics.1, 2, 3 Understanding the mechanisms responsible for these differences may lead to identification of new therapeutic targets for cancer. A growing body of evidence suggests that nonclassic estrogen signaling through the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) may be tumor suppressive, including in some cancers that are not traditionally considered sex hormone responsive, such as adrenocortical carcinoma, non–small cell lung cancer, colon carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and cutaneous melanoma.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Consistent with this, we recently showed that systemic administration of a specific small molecule synthetic GPER agonist, named G-1,10 in mice with therapy-resistant syngeneic melanoma induced differentiation in tumor cells that inhibited proliferation and rendered tumors more responsive to αPD-1 immune checkpoint blockade.8 GPER is expressed in many tissues11 and signals through ubiquitous cellular proteins that mediate cyclic adenosine monophosphate signaling. This led us to consider whether G-1 may have therapeutic utility as a broadly acting anticancer agent effective against GPER-expressing cancers.

To test this idea, we turned to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a highly aggressive GPER-expressing cancer that is poorly responsive to current therapy and a major cause of cancer death in the United States.12 As with many cancers, women have lower PDAC incidence and more favorable outcomes than men, suggesting that estrogen may suppress PDAC.1,2,13 Consistent with this, use of estradiol-containing oral contraceptives and history of multiple pregnancies, which correlate with high estrogen exposure, are both associated with decreased PDAC risk.14, 15, 16 Further supporting the idea that PDAC is influenced by estrogen are human clinical trials showing that tamoxifen, which is a GPER agonist, extends survival in PDAC patients.17,18 These data, coupled with a lack of clear evidence that nuclear estrogen receptors are expressed or functional in PDAC,19 and our RNAseq data (Supplementary Data) showing an absence of transcript for both of the classic estrogen receptors (ERα/ERβ) led us to test whether GPER activity inhibits PDAC.

Li and colleagues recently generated a library of clonal PDAC tumor cell lines from a genetically engineered mouse model of PDAC, KPCY (‘KPCY’ mice, KRas LSL-G12D/+; Trp53 L/+ or Trp53 LSL-R172H/+; Pdx1-Cre; Rosa- YFP), which faithfully recapitulates the molecular, histologic, and clinical features of the human disease.20, 21, 22 In syngeneic, immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice, the degree of immune infiltration in each tumor varies with each cell line. This variability reflects the natural heterogeneity in immune infiltrates observed in human PDAC. Here we used these new murine models, along with human PDAC tumor lines, to test whether GPER activation inhibits PDAC and/or improves PDAC response to immune checkpoint blockade.

Results

To test whether PDAC responds to GPER signaling, we used 3 genetically defined murine PDAC tumor lines that together represent the heterogeneity in immune infiltration and response to therapy: 6419c5 tumors are associated with minimal CD8+ T-cell infiltration and respond poorly to combined cytotoxic and immune therapy, 2838c3 tumors attract robust CD8+ T-cell infiltration and respond to therapy, and 6499c4 tumors are associated with robust CD8+ T-cell infiltration but only modest responses to therapy.22

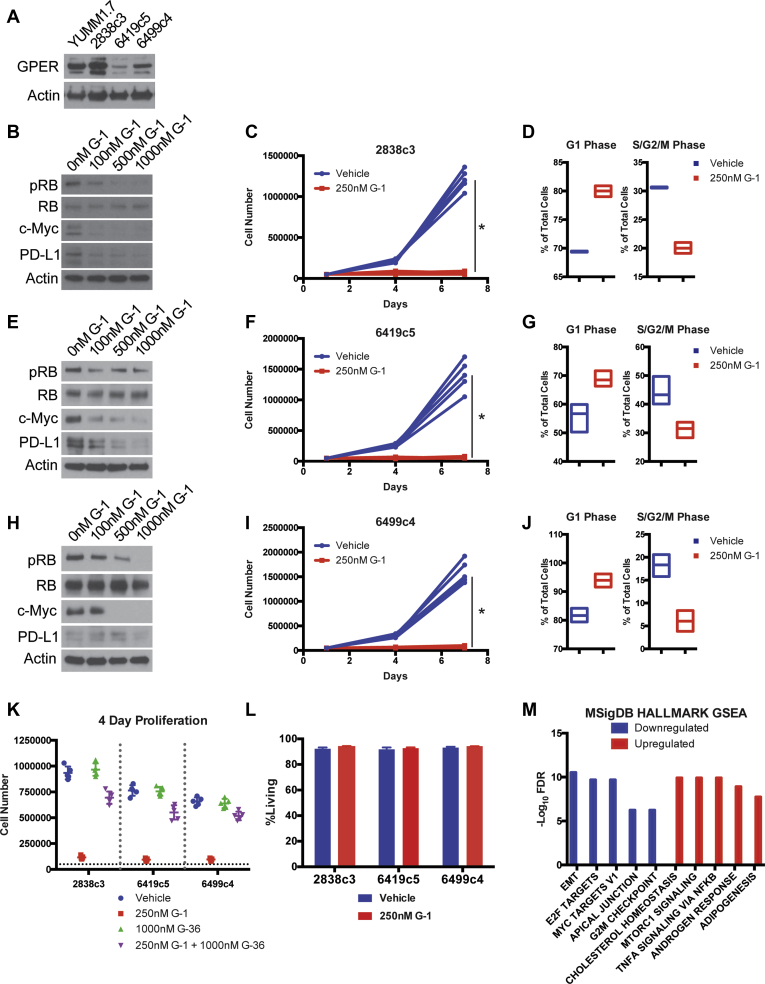

We first determined that GPER is expressed in all 3 PDAC tumor lines (Figure 1A). Each line also proved to be highly responsive to G-1. We observed a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation, which was associated with a G1-S cell cycle block and corresponding decreases in p-RB and c-Myc. The c-Myc depletion is significant, because c-Myc drives cell proliferation, invasion, and escape from immune surveillance and is commonly overexpressed in many cancers including PDAC. Consistent with the known role of c-Myc as a positive regulator of the immune checkpoint modulator programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1),23 we also noted that GPER activation depleted PD-L1 (Figure 1B–J), which we predicted would render cells more vulnerable to immune clearance. To test whether these effects were GPER dependent, we treated PDAC cells with a 4-fold molar excess of G-36, a specific GPER antagonist,24 and determined that G-36 blocked the effects of G-1 (Figure 1K). G-1 induced tumor cell growth arrest was not associated with cell death (Figure 1L).

Figure 1.

GPER activation inhibits PDAC. (A) GPER Western blot of lysates from murine YUMM1.7 melanoma cells (GPER positive control) and murine PDAC cells. (B) Western analysis of lysates from 2838c3 PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (C) Proliferation of 2838c3 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. *Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (D) Cell cycle analysis of 2838c3 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 3 per group. (E) Western analysis of lysates from 6419c5 PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (F) Proliferation of 6419c5 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (G) Cell cycle analysis of 6419c5 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 3 per group. (H) Western analysis of lysates from 6499c4 PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (I) Proliferation of 6499c4 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (J) Cell cycle analysis of 6499c5 PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 3 per group. (K) Proliferation assay of 2838c3, 6419c5, and 6499c4 PDAC cells treated with vehicle, 250 nmol/L G-1, 1000 nmol/L G-36, or combination of 250 nmol/L G-1 and 1000 nmol/L G-36. (L) Viability assay of murine PDAC cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 3 per group. (M) MSigDB HALLMARK gene set enrichment analysis of overlapping up-regulated and down-regulated genes in 2838c3, 6419c5, and 6499c4 cells treated with 250 nmol/L G-1 for 16 hours.

To determine whether GPER induces additional changes in PDAC cells that would suggest general antitumor activity, we performed RNA-Seq and HALLMARK gene set enrichment analysis on 2838c3, 6419c5, and 6499c4 tumor cells treated with G-1 vs vehicle control (Figure 1M). Consistent with observed changes in proliferation and c-Myc in Figure 1, GPER activation was broadly associated with decreased expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, invasion, and immune evasion including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition drivers, E2F targets, c-Myc targets, and cell cycle checkpoint regulators. These data are all consistent with the hypothesis that GPER signaling is generally tumor suppressive.

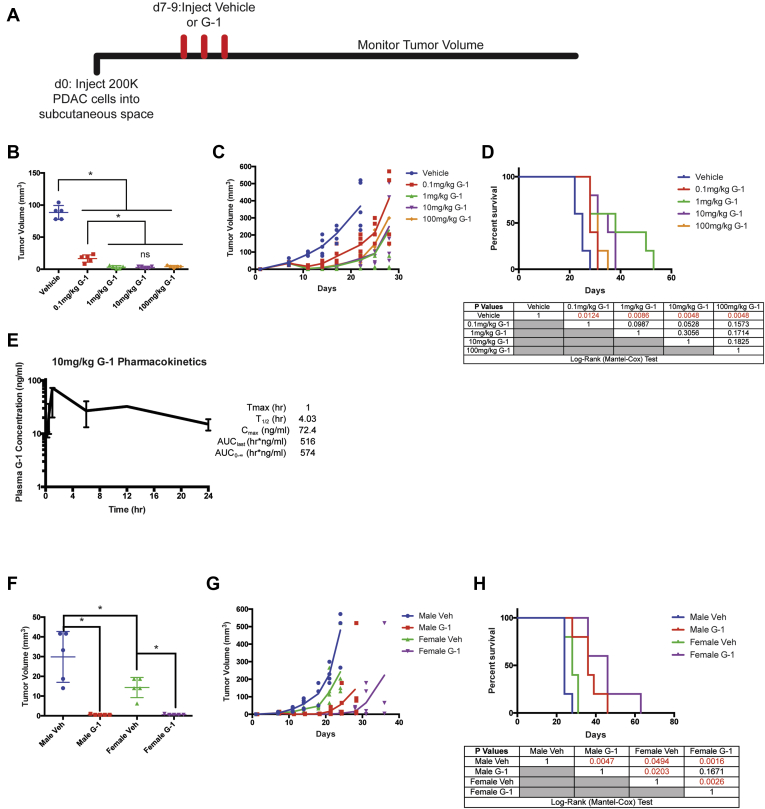

We next tested whether G-1 inhibited PDAC in vivo, and whether antitumor activity was saturable at pharmacologically achievable, nontoxic doses (Figure 2A). We observed tumor responses at 0.1 mg/kg (Figure 2B–D), with a maximal response that saturated at 1 mg/kg G-1. We did not observe any obvious toxicity at doses up to 100 mg/kg. A pharmacokinetic analysis at 10 mg/kg G-1 in mice showed a maximum plasma exposure of 72.4 ng/mL (176 nmol/L) (Figure 2E), which is comparable to the saturating exposure level we observe in vitro (Figure 1). We therefore used a dose of 10 mg/kg daily for all subsequent studies to ensure full GPER activity in vivo at a realistic, pharmacologically achievable dose.

Figure 2.

G-1 dose response in vivo and pharmacokinetics. (A) Experimental timeline of murine 2838c3 PDAC-bearing mice treated with subcutaneously delivered vehicle or a dose response of G-1, n = 5 per group. (B) Tumor volumes of 2838c3 PDAC tumors 1 day after final treatment with vehicle or G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by one-way analysis of variance. (C) 2838c3 tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (D) Survival curve of 28383-bearing mice treated with vehicle or a dose response of G-1; significance between groups by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test is listed in the table below. (E) Pharmacokinetics of 10 mg/kg G-1 in mice, n = 3 mice per time point. (F) Tumor volumes of 2838c3 PDAC tumors 1 day after final treatment with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1 in male and female mice, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by one-way analysis of variance. (G) 2838c3 tumor volumes in male and female mice, treated with 10 mg/kg G-1 measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (H) Survival curve of 28383-bearing male and female mice treated with vehicle 10 mg/kg G-1; significance between groups by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test is listed in the table below. AUC, area under the curve.

To determine whether responsiveness to G-1 is dependent on the sex of the host, we treated male and female immunocompetent BL/6 mice harboring syngeneic PDAC with subcutaneously administered G-1 at a 10 mg/kg dose. Treatment with G-1 in both male and female mice resulted in tumor regression and prolonged survival (Figure 2F–H). Responses did not vary significantly with the sex of the mouse.

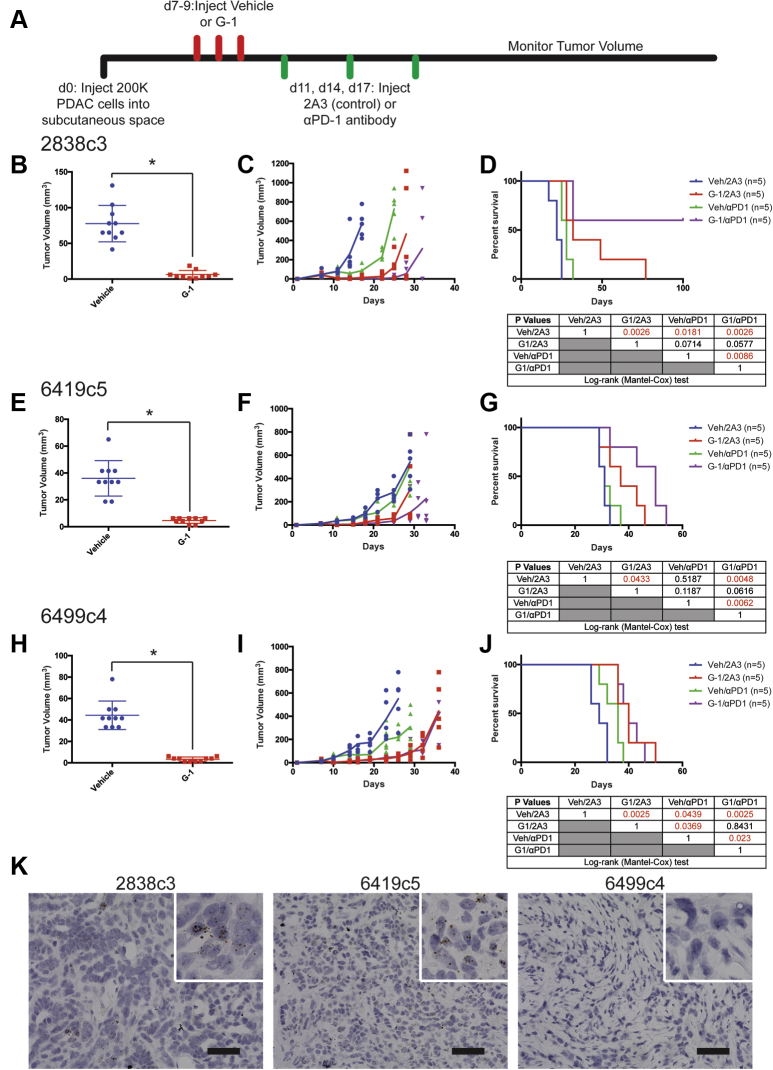

We next tested whether G-1 has therapeutic utility when delivered in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Immunocompetent BL/6 mice harboring syngeneic PDAC were treated with subcutaneously administered G-1, αPD-1 antibody, or both, and tumor growth and survival were compared with matched controls treated with vehicle and isotype antibody controls (Figure 3A–J). All 3 PDAC tumor models responded to G-1 monotherapy with rapid initial tumor regression and prolonged survival. Tumor response to αPD-1 varied with each tumor line but was significantly potentiated by G-1 in 2 of the 3 lines. The 2838c3 line was highly responsive to both G-1 and αPD-1, and the combination of both agents completely cleared tumors in 60% of animals with no evidence of disease at day 100, suggesting a combinatorial benefit. The 6419c5 line responded to G-1 but was completely resistant to αPD-1 monotherapy. However, G-1 and αPD-1 combination therapy extended survival beyond that observed with G-1 alone, again suggesting a combinatorial benefit. In contrast, combination therapy did not provide any additional benefit over G-1 monotherapy in 6499c4 tumors, which were only minimally responsive to αPD-1 alone.

Figure 3.

The specific GPER agonist G-1 inhibits murine PDAC in vivo. (A) Experimental timeline of murine PDAC-bearing mice treated with subcutaneously delivered vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1, as well as 10 mg/kg αPD-1 antibody or isotype antibody control (2A3), n = 5 per group. (B) Tumor volumes of 2838c3 PDAC tumors 1 day after final treatment with 10 mg/kg G-1, n = 10 per group. ∗Significance by one-way analysis of variance. (C) 2838c3 tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (D) Survival curve of 28383-bearing mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1, as well as 10 mg/kg αPD-1 antibody or 10 mg/kg isotype antibody control (2A3); significance between groups by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test is listed in the table below. (E) Tumor volumes of 6419c5 PDAC tumors 1 day after final treatment with 10 mg/kg G-1, n = 10 per group. ∗Significance by one-way analysis of variance. (F) 6419c5 tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (G) Survival curve of 6419c5-bearing mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1, as well as 10 mg/kg αPD-1 antibody or 10 mg/kg isotype antibody control (2A3); significance between groups by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test is listed in the table below. (H) Tumor volumes of 6499c4 PDAC tumors 1 day after final treatment with 10 mg/kg G-1, n = 10 per group. ∗Significance by one-way analysis of variance. (I) 6499c4 tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (J) Survival curve of 6499c4-bearing mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1, as well as 10 mg/kg αPD-1 antibody or 10 mg/kg isotype antibody control (2A3); significance between groups by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test is listed in the table below. (K) In situ hybridization for PD-L1 in murine PDAC tumors. Original magnification, ×40; scale bar = 50 μm.

In an effort to understand the mechanistic basis for the heterogeneous responses to αPD-1 with or without G-1, we next tested whether PD-L1 is expressed in each tumor. Using in situ hybridization for PD-L1 in treatment naive tumors, we detected high levels of PD-L1 expression in the anti-PD-1 responsive 2838c3 and 6419c5 lines and complete absence of PD-L1 in the nonresponding 6499c4 line (Figure 3K), indicating that the combinatorial survival-promoting effect of G-1 and αPD-1 depends on whether the tumor cells express PD-L1.

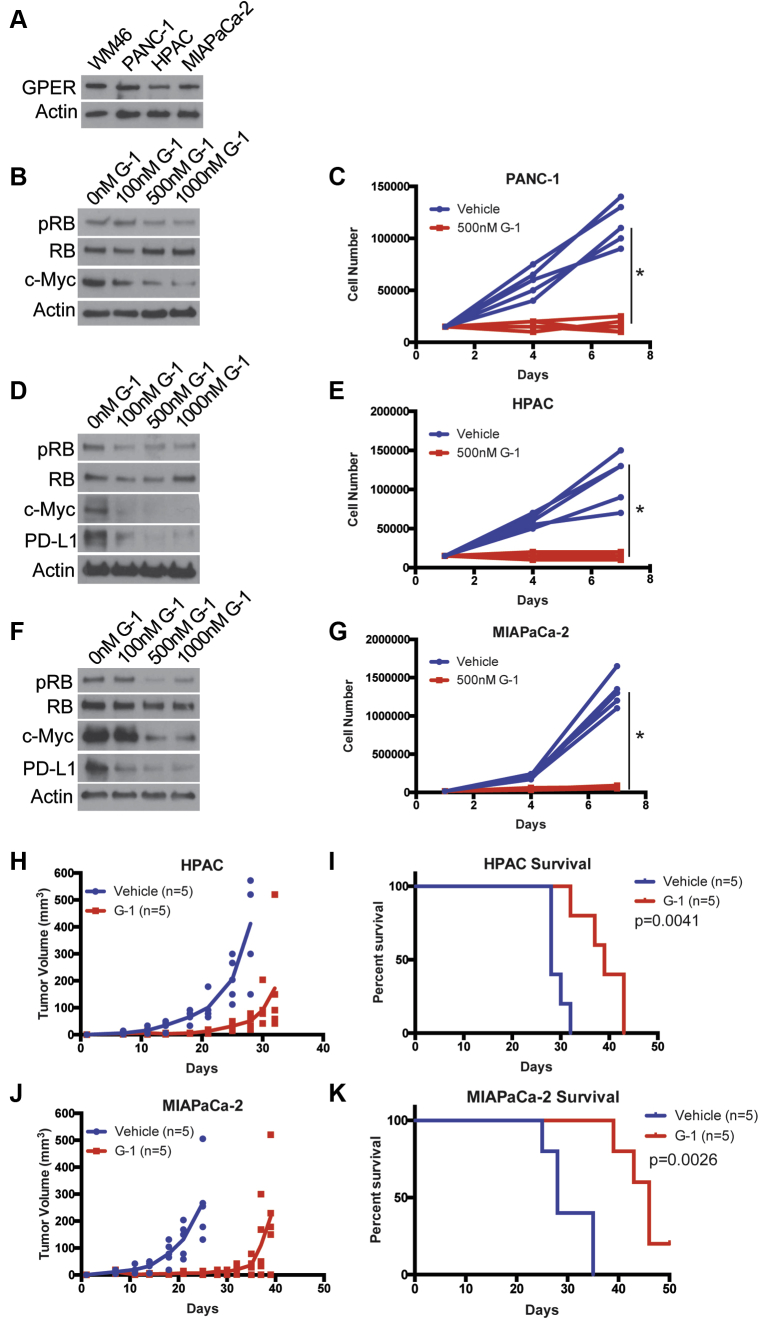

Next, we used human PDAC cell lines, harboring the activating K-Ras mutation that drives the vast majority of human PDAC, to test whether GPER activation has similar effects in human models. We detected GPER protein in all 3 human lines (Figure 4A). To test whether the effects of GPER signaling in human PDAC paralleled those in murine PDAC, we treated the human PDAC tumor cell lines with G-1 and observed similar dose-dependent decreases in p-RB and c-Myc, which were paralleled by decreases in proliferation (Figure 4B–G). We also observed depletion of PD-L1 in HPAC and MIA PaCa-2 cells but did not observe PD-L1 protein in untreated PANC-1 cells. To test whether G-1 has therapeutic utility against human PDAC in vivo, we treated nude mice harboring HPAC and MIA PaCa-2 tumors with subcutaneous G-1 one week after tumor implantation. HPAC and MIA PaCa-2 cells were originally derived from a female and a male patient, respectively. The PANC-1 cell line failed to establish tumors in nude mice. Treatment with G-1 significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival relative to vehicle treated controls in both male and female derived cell lines, suggesting the sex of the cell line does not influence responsiveness to a GPER agonist (Figure 4H–K). Because these studies with human PDAC models were conducted in immunodeficient mice, it was not possible to test for combinatorial activity with immune therapy, as we did in the murine models. Nonetheless, these in vitro and in vivo data using human PDAC are consistent with our findings in the mouse models, and together they support the idea that GPER activation with G-1 inhibits PDAC.

Figure 4.

The specific GPER agonist G-1 inhibits human PDAC. (A) GPER Western blot of lysates from human WM46 melanoma cells (GPER positive control) and human PDAC cells. (B) Western analysis of lysates from PANC-1 PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (C) Proliferation of PANC-1 PDAC cells treated with 500 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (D) Western analysis of lysates from HPAC PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (E) Proliferation of HPAC PDAC cells treated with 500 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (F) Western analysis of lysates from MIA PaCa-2 PDAC cells treated for 16 hours with increasing concentrations of G-1. (G) Proliferation of MIA PaCa-2 PDAC cells treated with 500 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. ∗Significance by two-way analysis of variance. (H) HPAC tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (I) Survival curve of HPAC-bearing mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1 on days 7–9, 14–16, and 21–23 (3 weekly pulses); significance between groups by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (J) MIA PaCa-2 tumor volumes measured over time; line terminates after first survival event in the group, n = 5 per group. (K) Survival curve of MIA PaCa-2–bearing mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg G-1 on days 7–9, 14–16, and 21–23 (3 weekly pulses); significance between groups by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

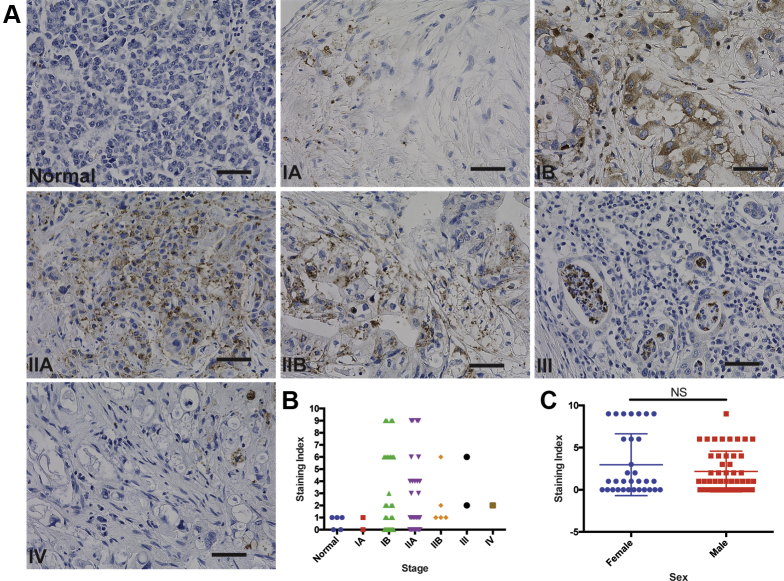

We next questioned the extent to which GPER is expressed in spontaneous human PDAC. Using a tissue microarray representing several stages of PDAC, immunohistochemical staining for GPER demonstrated both peripheral membrane and punctate cytoplasmic staining, alone or in combination in tumor cells. Staining for GPER was observed in islets, which was consistent with previous reports.25 There was a wide range of staining intensity across different clinical stages (Figure 5A and B). Overall, GPER was detected in 61% of the PDAC cases tested, suggesting that GPER may be a widely expressed and pharmacologically accessible therapeutic target in human PDAC. GPER was expressed similarly in male and female samples (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

GPER is expressed in human spontaneous PDAC. (A) Representative images of normal human pancreas and stage 1A-IV PDAC stained for GPER. Original magnification, ×40; scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Pathologist scoring of pancreatic tissue microarray stained for GPER; scoring index was determined by scoring percentage of positive cells on scale of 0–3, as well as intensity of GPER staining on scale of 0–3; these scores were multiplied to generate the scoring index. (C) Scoring of pancreatic tissue microarray comparing expression in male and female samples; significance by Mann-Whitney test.

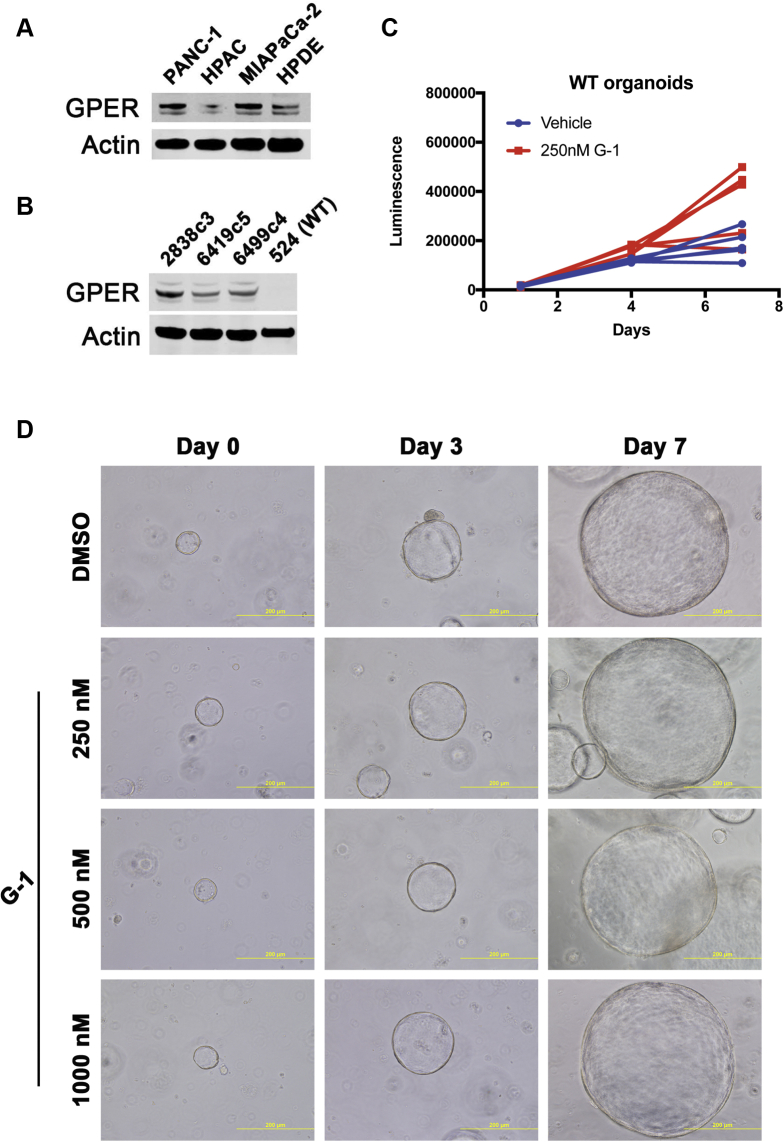

To determine whether GPER was expressed in normal pancreatic ductal cells, we analyzed protein expression in human pancreatic ductal epithelial (HPDE) cells and wild-type mouse pancreatic organoids. We observed some GPER expression in HPDE cells but did not detect GPER in wild-type mouse pancreatic organoids (Figure 6A and B). G-1 did not affect proliferation or appearance of wild-type mouse pancreatic organoid cultures, suggesting that expression of GPER is necessary for the effects of G-1 (Figure 6C and D).

Figure 6.

GPER is not expressed in normal pancreatic ductal cells, and G-1 is not active. (A) GPER Western blot of lysates from human PDAC cell lines and HPDE cells. (B) GPER Western blot of lysates from murine PDAC cell lines and wild-type murine pancreatic ductal organoids. (C) Proliferation of wild-type pancreatic ductal organoids treated with 250 nmol/L G-1, n = 5 per group. (D) Brightfield images of wild-type pancreatic ductal organoids treated with G-1. WT, wild-type.

Discussion

This body of work is consistent with multiple independent reports implicating noncanonical estrogen signaling as an important tumor suppressive pathway in PDAC. Recent reports demonstrate that GPER activation in PDAC results in peritumoral stromal remodeling and reduced desmoplasia, inflammation, and immune suppression.26,27 Another group demonstrated that 17β-estradiol increased the sensitivity of PDAC cells to chemotherapeutic drugs.28 Also consistent with our data, high GPER expression is correlated with improved survival in PDAC, and genistein analogs that activate GPER have chemoenhancing functions in PDAC patient-derived xenografts.29

Together with our previous study on melanoma, this work raises the possibility that the highly specific GPER agonist G-1 may have therapeutic utility against a wide array of GPER-expressing cancer types and critically may extend the utility of modern immune therapeutics to tumors that have thus far been resistant to immune therapy such as PDAC.30 These data highlight the importance of GPER signaling in cancer, demonstrate that GPER activity is tumor suppressive in cancers that are not classically considered hormone responsive, and suggest that GPER activity may contribute to biological differences between the sexes that influence cancer progression and response to modern therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Cell Lines

The 2838c3, 6419c5, and 6499c4 murine PDAC cells were derived from female mice in the laboratory of Ben Stanger22 (University of Pennsylvania) and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). PANC-1, HPAC, and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines were a gift from the laboratory of Ben Stanger (University of Pennsylvania) and cultured in DMEM (Mediatech) with 5% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). PANC-1 is derived from a male, HPAC is derived from a female, and MIA PaCa-2 is derived from a male. WM46 melanoma cells were a gift from Meenhard Herlyn (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA) and were cultured in TU2% media. Tumor cells were regularly tested by using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit from Lonza (Allendale, NJ). G-1 (10008933) and G-36 (14397) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Cells were trypsinized by using 0.05% trypsin with EDTA (Invitrogen) for 5 minutes to detach from the plate.

Mice

All mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Five- to 7-week-old C57BL/6J or nude (NU/J) mice were allowed to acclimatize for 1 week before being used for experiments. All mice were female unless otherwise noted. These studies were performed without inclusion/exclusion criteria or blinding but included randomization. On the basis of a 2-fold anticipated effect, we performed experiments with at least 5 biological replicates. All procedures were performed in accordance with International Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols at the University of Pennsylvania.

Subcutaneous Tumors and Treatments

Subcutaneous tumors were initiated by injecting tumor cells in 50% Matrigel (Corning, Bedford, MA) into the subcutaneous space on the left and right flanks of mice. Two × 105 murine PDAC cells or 5 × 105 human PDAC cells were used for each tumor. In vivo G-1 treatments were performed by first dissolving G-1, synthesized as described previously,9 in 100% ethanol at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. The desired amount of G-1 was then mixed with an appropriate volume of sesame oil, and the ethanol was evaporated off using a Savant Speed Vac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), leaving the desired amount of G-1 dissolved in 50 μL sesame oil per injection at a 10 mg/kg dose. Vehicle injections were prepared in an identical manner using 100% ethanol. Vehicle and G-1 injections were delivered through subcutaneous injection as indicated in each experimental timeline. Isotype control antibody (Clone: 2A3; BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH) and αPD-1 antibody (Clone: RMP1-14; BioXcell) were diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and delivered through intraperitoneal injections at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

Survival Analysis

As subcutaneous tumors grew in mice, perpendicular tumor diameters were measured by using calipers. Volume was calculated using the formula L × Wˆ2 × 0.52, where L is the longest dimension and W is the perpendicular dimension. Animals were euthanized when tumors exceeded a protocol-specified size of 15 mm in the longest dimension. Secondary endpoints included severe ulceration, death, and any other condition that falls within the International Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines for Rodent Tumor and Cancer Models at the University of Pennsylvania.

Western Blot Analysis

Adherent cells were washed once with Dulbecco’s PBS and lysed with 8 mol/L urea containing 50 mmol/L NaCl and 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 50 mmol/L iodoacetamide. Lysates were quantified (Bradford assay), normalized, reduced, and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis on 4–15% Tris/Glycine gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Resolved protein was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) by using a Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad), blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin in TBS-T, and probed with primary antibodies recognizing β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; #3700, 1:4000), c-Myc (Cell Signaling Technology; #13987, 1:1000), GPER (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; HPA027052, 1:500), HLA-ABC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA; w6/32,1:500), human PD-L1 (Cell Signaling Technology; #13684, 1:1000), mouse PD-L1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; AF1019, 1:500), p-RB (Cell Signaling Technology; #8516, 1:1000), and RB (Cell Signaling Technology; #9313, 1:1000). After incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody, proteins were detected by using either Luminata Crescendo Western HRP Substrate (Millipore), ECL Western Blotting Analysis System (GE Healthcare, Bensalem, PA), or the Odyssey CLx imaging system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). All Western blots were repeated at least 3 times.

Immunohistochemistry and Quantification

FFPE tissue microarrays were purchased from Biomax (9461e; Derwood, MD) and were stained GPER (Novus Biologics, Littleton, CO; NLS1183) as previously described with some modifications.8 Briefly, slides have been deparaffinized and rehydrated in extend time than standard immunohistochemistry protocol (in 3 xylenes 7 minutes each time, 3 times 100% alcohol, 2 times 95% alcohol, one times 70% and 50% alcohol, and finished with distilled water). The antigen retrieval was done by immersing the slides in Tris-EDTA pH 8.0, microwaved for 14 minutes at power 9, then cooled down to room temperature on the bench, washed 3 times in wash buffer, and blocked sequentially the endogenous peroxidase and nonspecific protein binding. The volume and the dilution/concentration (500 μL per slide at the dilution 1:70) of the primary antibody were calculated considering the total area of tissue and incubated overnight at 40°C. After multiple washes secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, was applied, incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature, and then washed out, and signal was amplified with substrate-DAB chromogen buffer. The tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cover-slipped, and analyzed. A board-certified pathologist performed scoring of the stained tissue microarray, and scoring index was determined by scoring the percentage of positive cells on a scale of 0–3 as well as the intensity of GPER staining on a scale of 0–3; these scores were multiplied to generate the scoring index value.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Tumor cells were cultured in 5% FBS in DMEM following standard cell culture protocol. Hoechst 33342 (ThermoFisher Scientific; #H1399) was added directly to the cell culture medium with the final concentration of 10 μg/mL 1 hour before sample collection. Cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 at 37°C for 1 hour. Then, cells were prepared to single cell suspension by using trypsin and washed with PBS twice. Cells were resuspended in flow buffer (1% FBS in PBS) for flow analysis in a BD LSR II flow cytometry machine. Flow results were analyzed by using the FlowJo software to assess the percentage of cells in G1 phase and S-G2-M phase.

Cell Viability Analysis

Tumor cells were cultured in 5% FBS in DMEM following standard cell culture protocol. Cells were prepared to single cell suspension by using trypsin and washed with PBS twice. Cells were resuspended in flow buffer (1% FBS in PBS) with DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific; #D21490) incubation for flow analysis in a BD LSR II flow cytometry machine. Flow results were analyzed by using the FlowJo software to assess the percentage of cells with negative staining of DAPI.

RNA-seq

RNA was extracted by using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; catalog no. 74014) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All RNA-seq libraries were prepared by using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module followed by NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (both from New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA). Library quality was analyzed by using Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and libraries were quantified by using NEB Library Quantification Kits (New England Biolabs). Libraries were then sequenced by using a NextSeq500 platform (75 base pairs, single-end reads) (Illumina). All RNA-seq was aligned by using RNA STAR under default settings to Homo sapiens UCSC hg19 (RefSeq & Gencode gene annotations). FPKM generation and differential expression analysis were performed by using DESeq2. DESeq2 output was analyzed by comparing differentially expressed genes with P <.05, and HALLMARK gene set enrichment analysis was performed by using MSigDB database.31 All RNAseq data are deposited on GEO under accession GSE117312.

RNA In Situ Hybridization Analysis

Tumor cells were subcutaneously implanted into C57BL/6 mice for tumor growth. Tumors were collected 3 weeks after implantation, fixed with Zinc Formalin Fixative (Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA; #21516), and embedded in paraffin. Tumor sample paraffin sections were used for RNA in situ hybridization analysis by using the RNAscope 2.5 HD Assay – BROWN (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA) with probe targeting CD274 (PD-L1) (420501). The RNA in situ hybridization analysis was performed following standard procedures from the kit manual and published protocol32 (RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues).

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed by Ricerca Biosciences (Concord, OH). Briefly, animals were not fasted before dosing. Animals were divided into 6 subgroups of 3 animals each. Each subgroup was bled at 1 time point and terminated after blood collection. G-1 was administered as described in “Subcutaneous tumors and treatments” section. Blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital sinus at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 6, 12, and 24 hours after dose. No animal was found dead or deemed moribund during the study. No abnormalities were observed at the detailed clinical observations, during the daily observations, or after initiation of dosing. At each blood collection period, 1 subgroup of animals was placed under deep anesthesia induced with CO2/O2; while still under anesthesia, the final blood sample was collected, and the animals were terminated by cervical dislocation. Plasma samples were sent to Ricerca Bioanalytical department for analysis. Pharmacokinetic analysis was conducted by using WinNonlin Version 6.2 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA), operating as a validated software system. Noncompartmental analysis was conducted by using an extravascular administration model. The area under the plasma concentration-time curves, peak plasma concentration, the time to achieve peak plasma concentration, and the plasma terminal half-life were calculated from mean plasma concentrations for each sampling time for G-1. Nominal blood collection times were used for toxicokinetic calculations.

Murine Pancreatic Ductal Organoid Culture

Pancreatic ductal cells were isolated from C57BL/6J mice, embedded in Matrigel domes, and maintained in mouse organoid complete feeding media, as previously described.33 Briefly, mouse organoid complete feeding media contain 0.5 μmol/L A83-01, 0.05 μg/mL EGF, 0.1 μg/mL FGF-10, 0.01 μmol/L gastrin I, 0.1 μg/mL noggin, 1.25 mmol/L N-acetylcysteine, 10 mmol/L nicotinamide, 1× B27, and 1× R-Spondin1-Conditioned Media. After treatment with G-1, organoid viability was assessed by CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Fitchberg, WI).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed by using Graphpad Prism 8 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Details of each statistical test used are included in the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Pennsylvania Skin Biology and Disease Research-based center for analysis of tissue sections. The authors also thank Michael Feigin, Miriam Doepner, and Junqian Zhang for critical pre-submission review.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Christopher Natale (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Jinyang Li (Data curation: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Jason R. Pitarresi (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Validation: Supporting)

Robert J. Norgard (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Validation: Supporting)

Tzvete Dentchev (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Brian Capell (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

John Seykora (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Ben Stanger (Conceptualization: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Todd W. Ridky (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Project administration: Supporting; Resources: Supporting; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: C.A.N. is listed as an inventor on a patent application held by the University of Pennsylvania related to this work (PCT/US2017/035278) and is a cofounder and current employee of the Penn Center for Innovation supported startup Linnaeus Therapeutics Inc. T.W.R. is listed as an inventor on a patent application (PCT/US2017/035278) held by the University of Pennsylvania related to this work and is a cofounder and consultant to the Penn Center for Innovation supported startup Linnaeus Therapeutics Inc. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding T.W.R. is supported by a grant from the NIH/NCI (R01 CA163566), a Penn/Wistar Institute N.I.H. SPORE (P50CA174523), the Melanoma Research Foundation, and the Dermatology Foundation. C.A.N was supported by an NIH/NIAMS training grant (T32 AR0007465-32) and an NIH/NCI F31 NRSA Individual Fellowship (F31 CA206325). This work was supported in part by the Penn Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center (P30-AR069589). This work was also supported in part by a phase I STTR from the NIH/NCI (R41CA228695). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary RNA-seq data are deposited on GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession GSE117312.

References

- 1.Cook M.B., Dawsey S.M., Freedman N.D., Inskip P.D., Wichner S.M., Quraishi S.M., Devesa S.S., McGlynn K.A. Sex disparities in cancer incidence by period and age. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1174–1182. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook M.B., McGlynn K.A., Devesa S.S., Freedman N.D., Anderson W.F. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1629–1637. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQuade J.L., Daniel C.R., Hess K.R., Mak C., Wang D.Y., Rai R.R., Park J.J., Haydu L.E., Spencer C., Wongchenko M., Lane S., Lee D.Y., Kaper M., McKean M., Beckermann K.E., Rubinstein S.M., Rooney I., Musib L., Budha N., Hsu J., Nowicki T.S., Avila A., Haas T., Puligandla M., Lee S., Fang S., Wargo J.A., Gershenwald J.E., Lee J.E., Hwu P., Chapman P.B., Sosman J.A., Schadendorf D., Grob J.J., Flaherty K.T., Walker D., Yan Y., McKenna E., Legos J.J., Carlino M.S., Ribas A., Kirkwood J.M., Long G.V., Johnson D.B., Menzies A.M., Davies M.A. Association of body-mass index and outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy: a retrospective, multicohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:310–322. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu G., Huang Y., Wu C., Wei D., Shi Y. Activation of G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor inhibits the migration of human nonsmall cell lung cancer cells via IKK-beta/NF-kappaB signals. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35:434–442. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Q., Chen Z., Jiang G., Zhou Y., Yang X., Huang H., Liu H., Du J., Wang H. Epigenetic down regulation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) functions as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:87. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0654-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimento A., Sirianni R., Casaburi I., Zolea F., Rizza P., Avena P., Malivindi R., De Luca A., Campana C., Martire E., Domanico F., Fallo F., Carpinelli G., Cerquetti L., Amendola D., Stigliano A., Pezzi V. GPER agonist G-1 decreases adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19190–19203. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z., Chen X., Zhao Y., Jin Y., Zheng J. G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor suppresses the migration of osteosarcoma cells via post-translational regulation of Snail. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2768-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Natale C.A., Li J., Zhang J., Dahal A., Dentchev T., Stanger B.Z., Ridky T.W. Activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor signaling inhibits melanoma and improves response to immune checkpoint blockade. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.31770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natale C.A., Duperret E.K., Zhang J., Sadeghi R., Dahal A., O'Brien K.T., Cookson R., Winkler J.D., Ridky T.W. Sex steroids regulate skin pigmentation through nonclassical membrane-bound receptors. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.15104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bologa C.G., Revankar C.M., Young S.M., Edwards B.S., Arterburn J.B., Kiselyov A.S., Parker M.A., Tkachenko S.E., Savchuck N.P., Sklar L.A., Oprea T.I., Prossnitz E.R. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nature Chemical Biology. 2006;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olde B., Leeb-Lundberg L.M. GPR30/GPER1: searching for a role in estrogen physiology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahib L., Smith B.D., Aizenberg R., Rosenzweig A.B., Fleshman J.M., Matrisian L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J., Siegel R., Jemal A. Pancreatic cancer death rates by race among US men and women, 1970-2009. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1694–1700. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu B., Zou L., Han J., Chen W., Shen N., Zhong R., Li J., Chen X., Liu C., Shi Y., Miao X. Parity and pancreatic cancer risk: evidence from a meta-analysis of twenty epidemiologic studies. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5313. doi: 10.1038/srep05313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee E., Horn-Ross P.L., Rull R.P., Neuhausen S.L., Anton-Culver H., Ursin G., Henderson K.D., Bernstein L. Reproductive factors, exogenous hormones, and pancreatic cancer risk in the CTS. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1403–1413. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson G., Borgquist S., Jirstrom K. Hormonal factors and pancreatic cancer risk in women: the Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:52–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong A., Chan A. Survival benefit of tamoxifen therapy in adenocarcinoma of pancreas: a case-control study. Cancer. 1993;71:2200–2203. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930401)71:7<2200::aid-cncr2820710706>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theve N.O., Pousette A., Carlstrom K. Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a hormone sensitive tumor? a preliminary report on Nolvadex treatment. Clin Oncol. 1983;9:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satake M., Sawai H., Go V.L., Satake K., Reber H.A., Hines O.J., Eibl G. Estrogen receptors in pancreatic tumors. Pancreas. 2006;33:119–127. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000226893.09194.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hingorani S.R., Wang L., Multani A.S., Combs C., Deramaudt T.B., Hruban R.H., Rustgi A.K., Chang S., Tuveson D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhim A.D., Mirek E.T., Aiello N.M., Maitra A., Bailey J.M., McAllister F., Reichert M., Beatty G.L., Rustgi A.K., Vonderheide R.H., Leach S.D., Stanger B.Z. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J., Byrne K.T., Yan F., Yamazoe T., Chen Z., Baslan T., Richman L.P., Lin J.H., Sun Y.H., Rech A.J., Balli D., Hay C.A., Sela Y., Merrell A.J., Liudahl S.M., Gordon N., Norgard R.J., Yuan S., Yu S., Chao T., Ye S., Eisinger-Mathason T.S.K., Faryabi R.B., Tobias J.W., Lowe S.W., Coussens L.M., Wherry E.J., Vonderheide R.H., Stanger B.Z. Tumor cell-intrinsic factors underlie heterogeneity of immune cell infiltration and response to immunotherapy. Immunity. 2018;49:178–193.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casey S.C., Tong L., Li Y., Do R., Walz S., Fitzgerald K.N., Gouw A.M., Baylot V., Gutgemann I., Eilers M., Felsher D.W. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;352:227–231. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennis M.K., Field A.S., Burai R., Ramesh C., Petrie W.K., Bologa C.G., Oprea T.I., Yamaguchi Y., Hayashi S., Sklar L.A., Hathaway H.J., Arterburn J.B., Prossnitz E.R. Identification of a GPER/GPR30 antagonist with improved estrogen receptor counterselectivity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar R., Balhuizen A., Amisten S., Lundquist I., Salehi A. Insulinotropic and antidiabetic effects of 17beta-estradiol and the GPR30 agonist G-1 on human pancreatic islets. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2568–2579. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes E., Sarper M., Robinson B., Lachowski D., Chronopoulos A., Thorpe S.D., Lee D.A., Del Rio Hernandez A.E. GPER is a mechanoregulator of pancreatic stellate cells and the tumor microenvironment. EMBO Rep. 2019;20 doi: 10.15252/embr.201846556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cortes E., Lachowski D., Robinson B., Sarper M., Teppo J.S., Thorpe S.D., Lieberthal T.J., Iwamoto K., Lee D.A., Okada-Hatakeyama M., Varjosalo M.T., Del Rio Hernandez A.E. Tamoxifen mechanically reprograms the tumor microenvironment via HIF-1A and reduces cancer cell survival. EMBO Rep. 2019;20 doi: 10.15252/embr.201846557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akula S.M., Candido S., Abrams S.L., Steelman L.S., Lertpiriyapong K., Cocco L., Ramazzotti G., Ratti S., Follo M.Y., Martelli A.M., Murata R.M., Rosalen P.L., Bueno-Silva B., Matias de Alencar S., Falasca M., Montalto G., Cervello M., Notarbartolo M., Gizak A., Rakus D., Libra M., McCubrey J.A. Abilities of beta-estradiol to interact with chemotherapeutic drugs, signal transduction inhibitors and nutraceuticals and alter the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Adv Biol Regul. 2019:100672. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2019.100672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mesmar F., Dai B., Ibrahim A., Hases L., Jafferali M.H., Jose Augustine J., DiLorenzo S., Kang Y., Zhao Y., Wang J., Kim M., Lin C.Y., Berkenstam A., Fleming J., Williams C. Clinical candidate and genistein analogue AXP107-11 has chemoenhancing functions in pancreatic adenocarcinoma through G protein-coupled estrogen receptor signaling. Cancer Med. 2019;8:7705–7719. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison A.H., Byrne K.T., Vonderheide R.H. Immunotherapy and prevention of pancreatic cancer. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Mesirov J.P. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F., Flanagan J., Su N., Wang L.C., Bui S., Nielson A., Wu X., Vo H.T., Ma X.J., Luo Y. RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boj S.F., Hwang C.I., Baker L.A., Chio I.I., Engle D.D., Corbo V., Jager M., Ponz-Sarvise M., Tiriac H., Spector M.S., Gracanin A., Oni T., Yu K.H., van Boxtel R., Huch M., Rivera K.D., Wilson J.P., Feigin M.E., Ohlund D., Handly-Santana A., Ardito-Abraham C.M., Ludwig M., Elyada E., Alagesan B., Biffi G., Yordanov G.N., Delcuze B., Creighton B., Wright K., Park Y., Morsink F.H., Molenaar I.Q., Borel Rinkes I.H., Cuppen E., Hao Y., Jin Y., Nijman I.J., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Leach S.D., Pappin D.J., Hammell M., Klimstra D.S., Basturk O., Hruban R.H., Offerhaus G.J., Vries R.G., Clevers H., Tuveson D.A. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]