Abstract

Objective

To confirm that metformin prevents flares in patients with SLE with low disease activity, we performed a post hoc analysis combining our previous two randomised trials.

Methods

Post hoc analyses were performed on data from the open-labelled proof-of-concept trial (n=113, ChiCTR-TRC-12002419) and placebo-controlled ‘Met Lupus’ trial (n=140, NCT02741960) comparing the efficacy of metformin versus placebo/nil add-on to standard therapy in patients with SLE with low disease activity (SELENA-SLEDAI ≤4). The primary endpoint was defined by the SELENA-SLEDAI Flare Index at 12-month follow-up. A subgroup analysis was performed.

Results

Overall, 201 eligible patients were included, with 99 allocated to metformin group and 102 allocated to the placebo/nil group. By 12 months of follow-up, 21 patients (21.2%) flared in the metformin group, as compared with 36 (35.3%) in the placebo/nil group (p=0.027, risk ratio=0.68, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.96). Subgroup analysis showed that patients with negative anti-dsDNA antibody and normal complement at baseline, and a disease duration <5 years with concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine had a better response to metformin.

Conclusion

Post hoc pooled analyses suggested that metformin reduced subsequent disease flares in patients with SLE with low disease activity, especially for serologically quiescent patients.

Keywords: lupus erythematosus, systemic, autoantibodies, therapeutics

Introduction

SLE remains a chronic autoimmune disease very difficult to treat despite growing advances. Three fundamental questions are always asked in the definition of treatment goals for SLE, that is, ‘How to control active disease?’, ‘How to minimise accrual organ damage?’ and ‘How to prevent disease flares?’. The reality of the last question is burdensome. It has been reported that the overall annual flare rate in various lupus populations, non-Caucasian or multi-ethnic cohorts in particular, is over 20%–40%, even in a stable disease setting.1–3 Owing to the intrinsic immunometabolic abnormalities of SLE,4 5 metformin, a traditional anti-diabetic drug, add-on to standard therapy becomes an intriguing and promising metabolic approach to prevent flares.

Two investigator-initiated, randomised controlled trials have been completed, each with inconclusive results. The first single-centre, open-labelled, proof-of-concept trial enrolled Chinese patients with SLE with mild-to-moderate disease activity (baseline prednisone ≤30 mg/day) and demonstrated that metformin add-on decreased 1-year frequency of disease flares (metformin: 23.2% vs nil: 42.1%, p=0.04).1 Thus, we initiated a multicentre, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial (‘Met Lupus’ Trial) to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of metformin in low-grade activity (baseline SELENA-SLEDAI ≤6, prednisone ≤20 mg/day) Chinese patients with SLE at risk of flares (with documented flare within 12 months before screening).3 However, this trial was under-recruited to draw a definite conclusion. The primary endpoint of reducing disease flares within 12 months was unmet, although a lower frequency was observed (metformin: 20.9% vs placebo: 34.2%, p=0.08).3 Nevertheless, the safety profile of metformin was consistently good in these two trials. To further address the lupus flare prevention outcome, we carried out a post hoc analysis by combining the aforementioned two trials, which were the only two existing and similarly designed. This post hoc pooled analysis was empowered to evaluate the effect of metformin on subgroups of patients.

Methods

The proof-of-concept trial (ChiCTR-TRC-12002419, n=113, 2012–2014 enrolment) and the ‘Met Lupus’ trial (NCT02741960, n=140, 2016–2017 enrolment) were conducted in Shanghai, China. Eligible patients fulfilled the following criteria from the intention-to-treat populations: (1) SLE classification criteria6 and age ≥18 years; (2) SELENA-SLEDAI score7 ≤4 at screening; (3) stable treatment regimen with fixed doses of prednisone (≤20 mg/day), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or immunosuppressants for at least 30 days before screening. The exclusion criteria included (1) previous exposure of metformin within 30 days before screening; (2) history of type I or type II diabetes; (3) hepatic or renal dysfunction; (4) current pregnancy or breast feeding; (5) previous exposure to cyclophosphamide or biological agents in the past 6 months. Metformin was administered with a target dose of 0.5 g, three times daily. The control group was either taking placebo or nil.

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients with lupus flares defined by the modified SELENA-SLEDAI Flare Index8 at 12-month follow-up. The secondary outcomes included the frequency of major flares, mild-to-moderate flares, time to flare, time to major flare, change of prednisone dose, change of body mass index (BMI) and subgroup analyses. Continuous parameters were compared with Student’s two-tailed t-test, and categorical parameters were analysed with χ2 test. Kaplan-Meier curve was applied, and event-free survival was adjusted for trial by Cox regression analysis. Subgroup and interaction analyses in the Forest plot for outcomes were carried out according to clinical and laboratory parameters, including BMI, disease duration, concomitant drug use and serology markers (anti-dsDNA antibody and complement levels), using Cox regression model without trial adjustment. A p value <0.05 was considered as significant. SPSS software V.22.0 and GraphPad software V.5.0 were used for analysis.

Results

Of the 113 patients in the proof-of-concept trial, 28 were excluded due to SELENA-SLEDAI score >4 at screening, 13 were subsequently ruled out because their baseline prednisone was >20 mg/day and another 2 were excluded due to recent exposure to cyclophosphamide, leaving 70 eligible patients for this post hoc pooled analyses. Of the 140 patients in the ‘Met Lupus’ trial, 131 patients were selected according to the same criteria (online supplemental figure S1). Of those 201 eligible patients with SLE, 91% (187) were female. The mean age was 32.5 years, and the mean disease duration was 4.3 years. The average baseline SELENA-SLEDAI score was 2.2 and the daily dose of prednisone was 10.2 mg at screening. The metformin arm included 99 patients, of which 36 were from the proof-of-concept trial and 63 from the Met Lupus trial; while 102 patients in the placebo/nil arm consisted of 34 and 68 patients from the two trials, respectively. Baseline characteristics of eligible patients from two trials and two pooled arms (metformin vs placebo/nil) were comparable (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients from the two trials and two treatment groups

| Characteristics | Proof-of-concept trial (n=70) | Met Lupus trial (n=131) |

Pooled data (n=201) |

Metformin (n=99) |

Placebo/nil (n=102) |

| Age (years) | 31.00±12.73 | 33.23±11.65 | 32.47±12.05 | 32.63±12.07 | 32.31±12.08 |

| Female | 87.1% (61) | 93.1% (122) | 91.0% (183) | 89.9% (89) | 92.2% (94) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.22±3.52 | 22.84±3.64 | 22.62±3.60 | 22.29±3.44 | 22.95±3.74 |

| Disease duration (years) | 3.46±3.78 | 4.74±4.28 | 4.30±4.13 | 4.01±3.74 | 4.57±4.51 |

| SELENA-SLEDAI | 1.63±1.65 | 2.44±1.54 | 2.15±1.62 | 2.04±1.60 | 2.26±1.65 |

| Serological results | |||||

| dsDNA+ | 58.6% (41) | 61.1% (80) | 60.2% (121) | 59.6% (59) | 60.8% (62) |

| Low C3 | 55.7% (39) | 51.9% (68) | 53.2% (107) | 51.5% (51) | 54.9% (56) |

| Low C4 | 24.3% (17) | 16.0% (21) | 18.9% (38) | 18.2% (18) | 19.6% (20) |

| Baseline therapy | |||||

| Prednisone (mg/day) | 9.6±4.46 | 10.53±4.44 | 10.21±4.46 | 10.09±4.63 | 10.32±4.31 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 88.6% (62) | 90.1% (118) | 89.6% (180) | 91.9% (91) | 87.3% (89) |

| IS* | 60.0% (42) | 67.2% (88) | 64.7% (130) | 67.7% (67) | 61.8% (63) |

| Mycophenolate | 24.3% (17) | 34.4% (45) | 30.9% (62) | 29.3% (29) | 32.4% (33) |

| Methotrexate | 21.4% (15) | 18.3% (24) | 19.4% (39) | 20.2% (20) | 18.6% (19) |

| Azathioprine | 11.4% (8) | 6.9% (9) | 8.5% (17) | 9.09% (9) | 7.8% (8) |

| Ciclosporin | 1.4% (1) | 2.3% (3) | 2.0% (4) | 2.0% (2) | 2.0% (2) |

| Tacrolimus | 0% (0) | 3.1% (4) | 2.0% (4) | 4.0% (4) | 0% (0) |

| Leflunomide | 1.4% (1) | 2.3% (3) | 2.0% (4) | 3.03% (3) | 1.0% (1) |

| Flares | |||||

| Any | 30% (21) | 27.5% (36) | 28.4% (57) | 21.2% (21) | 35.3% (36) |

| Major | 12.9% (9) | 20.6% (27) | 17.9% (36) | 12.1% (12) | 23.5% (24) |

*IS: immunosuppressive agents; none of the patients were treated with sirolimus. Number of patients are indicated in parentheses.

BMI, body mass index.

lupus-2020-000429supp001.pdf (812KB, pdf)

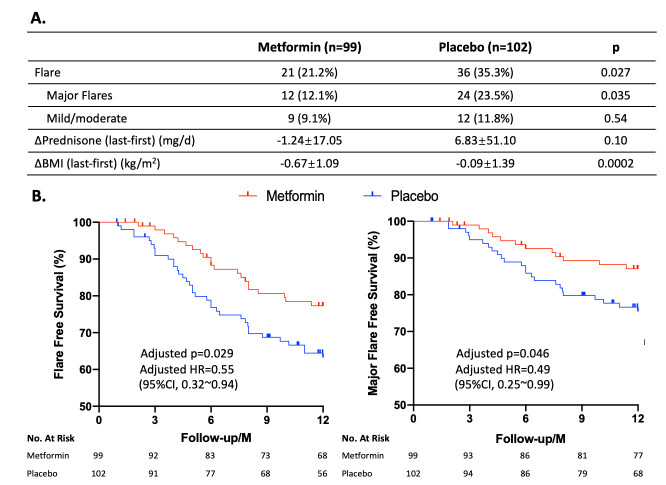

During the 12-month follow-up, 21.2% patients (n=21) flared in the metformin group, which was significantly lower than in the placebo/nil group, which was 35.3% (n=36) (p=0.027, RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.96). Patients taking metformin also had less major flares (12.1% vs 23.5%, p=0.035, RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.97) (figure 1A). Flare-free and major flare-free survival analysis by Kaplan-Meier curve further indicated that metformin reduced disease flares by 45% (adjusted HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.94) and major flares by 51% (adjusted HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99) within 12 months (figure 1B). Specific flare events in the two arms are listed in online supplemental table S1. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the prednisone dose changes from baseline to last visit, whereas the BMI net reduction was more pronounced in the metformin group (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Outcome measures of pooled analysis. (A) Flares, changes of prednisone and body mass index (BMI) during 12-month follow-up. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of flare-free survival and major flare-free survival. P values and HRs were adjusted for trial using Cox model.

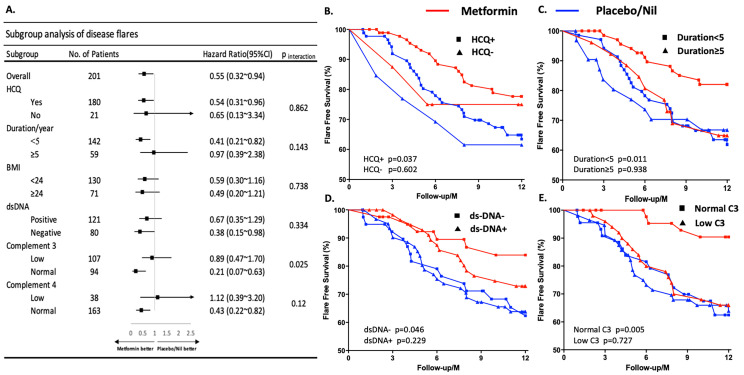

In order to identify specific subtypes of patients with SLE who will benefit most from metformin, a subgroup analysis was performed. Interestingly, patients with negative anti-dsDNA antibody (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.98), normal complement 4 (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.82) and normal complement 3 (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.63) level in particular (p=0.025 for the interaction) at baseline showed a better response to metformin in terms of preventing disease flares. Patients with a disease duration <5 years (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.82) and concomitant use of HCQ (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.96) also incurred a better responsiveness to metformin (figure 2A–E).

Figure 2.

Subgroup and interaction analysis. (A) Forest map for different subgroups. Comparisons of flare-free survival curves in patients with or without concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (B), with disease duration <5 or ≥5 years (C), with baseline status of anti-dsDNA (D) and C3 (E) as indicated. BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

Most of the current SLE clinical trials focus on how to control active disease,9 10 which leaves the question on how to prevent lupus flares largely unanswered. This question, however, is likely to be the key that bridges active disease control and accrual damage protection. Metformin, given its good safety profile and very low cost, becomes an appealing candidate as a secondary prevention tool to reduce SLE flare risk.

This post hoc pooled analyses focused on a group of SLE with low disease activity but at risk to flare. Two-thirds of the subjects belonged to the ‘Met Lupus’ trial in which the participants had had at least one documented disease flare within the past 12 months. The previous flare information was lacking for the remaining one-third of patients. However, patients from both trials share a similar subsequent annual flare incidence (~30%) and other baseline clinical features. The rationale for specifying SELENA-SLEDAI ≤4 in the inclusion criteria for the current pooled analysis is to enrich a more homogeneous population, that is, patients with SLE with baseline low disease activity by definition.11 As an informative example, a recent randomised trial tested the withdrawal of low-dose prednisone (5 mg/day) in patients with SLE with a clinically quiescent disease (SELENA-SLEDAI≤4). All participants were flare-free for more than 1 year, and 46% of them had long-term clinical quiescence (> 5-year flare-free). After prednisone withdrawal, the 12-month flare incidence increased from 7% to 27%.12 In other words, pursuing higher treatment goals such as glucocorticoid-free Doris remission11 in patients with an established low disease activity may subject them to flare risks. Whether metformin add-on could facilitate achieving these higher treatment goals in low-activity patients with SLE by preventing flares is yet to be explored.

Intriguingly, subgroup and interaction analysis identified that patients with serological quiescence (negative for anti-dsDNA antibody or normal complement levels) at baseline had the lowest disease flare incidence when treated with metformin, especially those with normal complement 3. As accepted biomarkers reflecting disease activity, anti-dsDNA antibody and complement levels do not predict well subsequent flares.13 Indeed, our pooled data demonstrated similar flare incidence between serological quiescent and serological active patients in the placebo/nil group (figure 2D, E). This serological-quiescent-responder pattern of metformin may be rooted to its unique mode of action, apart from other treatments, such as belimumab where the responders tend to be serologically active patients.14 This phenomenon offers a rationale for future investigations on combination therapies. In fact, according to our data, metformin may have a synergic effect with HCQ, while no such effect was observed with other immunosuppressants, such as with mycophenolate mofetil (data not shown). Of note, since metformin indirectly blocks mTOR, which is a canonical target of sirolimus in SLE,10 however, none of our patients were treated with sirolimus. Therefore, analysis regarding the possible interaction between these two agents was unavailable. In addition, the disease duration <5 years was another indicator for metformin response. The BLISS trials indicated that a damage index (SDI score) >1 reduced the efficacy of belimumab.15 Whether the disease duration reflects the accrual damage over time, which in turn impacts the metformin response, deserves further investigation.

Our study has several limitations. First, this post hoc pooled analyses combining one open-labelled study and one underpowered RCT requires a cautious interpretation. The caveat is that the evidence it provided should not surpass strictly designed RCT. In addition, as we have mentioned previously,4 our studies were conducted only with Chinese patients with SLE in Shanghai, which limits its generalisability. A larger and longer multicentre trial in different ethnic populations is warranted.

In conclusion, this post hoc pooled analysis further confirmed the possible efficacy of metformin in patients with SLE with low disease activity in regard to preventing disease flares, especially for serologically quiescent patients. Moreover, our data may help to shape further clinical trial design to provide evidence guiding better management for this very difficult disease.

Footnotes

FS and SG contributed equally.

Contributors: SY and LM participated in study design and revision of the manuscript. FS and SG were involved in literature search, data collection, statistical analysis, writing and revision of the manuscript. HaW, HuW, ZL, TL and XW participated in data collection. LL, WW and XT were involved in data collection and supervision of the study. All the authors revised the manuscript and approved the final report.

Funding: This study was supported by Shanghai Shenkang Promoting Project (16CR1013A), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC0909002) and National Institutes of Health (R01 AI128901).

Competing interests: SY reports personal grants from Shanghai Shenkang Promoting Project (16CR1013A); LL reports grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC0909002); LM reports a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI128901).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Wang H, Li T, Chen S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap mitochondrial DNA and its autoantibody in systemic lupus erythematosus and a proof-of-concept trial of metformin. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:3190–200. 10.1002/art.39296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez D, Kirou KA. What causes lupus flares? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016;18:14. 10.1007/s11926-016-0562-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun F, Wang HJ, Liu Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of metformin in systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e210–6. 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin Y, Choi S-C, Xu Z, et al. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:274ra18. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ursini F, Russo E, Pellino G, et al. Metformin and autoimmunity: a “new deal” of an old drug. Front Immunol 2018;9:1236. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725. 10.1002/art.1780400928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 1992;35:630–40. 10.1002/art.1780350606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2550–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa051135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:721–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai Z-W, Kelly R, Winans T, et al. Sirolimus in patients with clinically active systemic lupus erythematosus resistant to, or intolerant of, conventional medications: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet 2018;391:1186–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30485-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Vollenhoven R, Voskuyl A, Bertsias G, et al. A framework for remission in SLE: consensus findings from a large international task force on definitions of remission in SLE (DORIS). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:554–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathian A, Pha M, Haroche J, et al. Withdrawal of low-dose prednisone in SLE patients with a clinically quiescent disease for more than 1 year: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:339–46. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiman AJ, Gladman DD, Ibañez D, et al. Prolonged serologically active clinically quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: frequency and outcome. J Rheumatol 2010;37:1822–7. 10.3899/jrheum.100007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1343–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parodis I, Sjöwall C, Jönsen A, et al. Smoking and pre-existing organ damage reduce the efficacy of belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 2017;16:343–51. 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

lupus-2020-000429supp001.pdf (812KB, pdf)