Abstract

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) causes extensive mortality in poultry flocks, leading to extensive economic losses. The aim of this study was to investigate the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics and antimicrobial resistance of recent APEC isolates. Of the 79 APEC isolates, the most predominant serogroup was O78 (16 isolates, 20.3%), followed by O2 (7 isolates, 8.9%) and O53 (7 isolates, 8.9%). Thirty-seven (46.8%) and six (7.6%) of the isolates belonged to phylogenetic groups D and B2, respectively, and presented as virulent extraintestinal E. coli. Among 5 analyzed virulence genes, the highest frequency was observed in hlyF (74 isolates, 93.7%), followed by iutA (72 isolates, 91.9%) gene. The distribution of the iss gene was significantly different between groups A/B1 and B2/D (P < 0.05). All group B2 isolates carried all 5 virulence genes. APEC isolates showed high resistance to ampicillin (83.5%), nalidixic acid (65.8%), tetracycline (64.6%), cephalothin (46.8%), and ciprofloxacin (46.8%). The β-lactamases–encoding genes blaTEM-1 (23 isolates, 29.1%), blaCTX-M-1 (4 isolates, 5.1%), and blaCTX-M-15 (3 isolates, 3.8%); the aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme gene aac(3)-II (4 isolates, 5.1%); and the plasmid-mediated quinolone genes qnrA (10 isolates, 12.7%) and qnrS (2 isolates, 2.5%) were identified in APEC isolates. The tetA (37 isolates, 46.8%) and sul2 (20 isolates, 25.3%) were the most prevalent among tetracycline and sulfonamide resistant isolates, respectively. This study indicates that APEC isolates harbor a variety of virulence and resistance genes; such genes are often associated with plasmids that facilitate their transmission between bacteria and should be continuously monitored to track APEC transmission in poultry farms.

Key words: avian pathogenic Escherichia coli, antimicrobial resistance, phylogenetic group, broilers

Introduction

Colibacillosis is an infectious disease caused by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) and affects poultry flocks worldwide including Korea (Kim et al., 2007, Lutful Kabir, 2010). APEC is associated with different kinds of disease ranging from respiratory tract infection to swollen head syndrome in poultry (Dho-moulin and Fairbrother, 1999). Avian colibacillosis primarily affects broiler chickens between the ages of 4 and 6 wk and is considered a principal cause of morbidity and mortality, leading to considerable economic losses to the poultry industry (Dho-moulin and Fairbrother, 1999, Guabiraba and Schouler, 2015).

APEC strains mostly belong to the phylogenetic group associated with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), but studies report wide serological diversity among strains (Wang et al., 2010a, Schouler et al., 2012). Although serogroups O2 and O78 represent 80% of disease-causing APEC worldwide (Dziva and Stevens, 2008), their prevalence varies among farms and countries described (Oh et al., 2011, Barbieri et al., 2015, Younis et al., 2017). A recent report characterized a set of APEC strains as E. coli isolates containing 2 or more virulence markers (Johnson et al., 2008). In particular, de Oliveira et al. (2015) reported that several virulence genes (hlyF, ompT, iroN, iss, and iutA) located on the large virulence-plasmid ColV were associated with APEC strains. In addition, Johnson et al. (2008) reported that APEC strains with virulence genes may act as zoonotic pathogens and virulence reservoirs and could jump to other species and cause human infection.

In Korea, colibacillosis in broilers is a critically important disease and often occurs during respiratory stress caused by infection with Mycoplasma gallisepticum or viral agents such as infectious bronchitis virus (Oh et al., 2011). The use of antimicrobial drugs such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones remains the predominant option for colibacillosis outbreak (Kim et al., 2007). The continuous use of these antimicrobial drugs in poultry, however, has contributed to the emergence and sustenance of antimicrobial-resistant E. coli in Korea (Unno et al., 2011). Resistance in poultry bacteria may present a public health threat because of the potential transmission of resistance genes to human bacteria (Cavicchio et al., 2012).

Studies from several countries have documented the presence of virulence and resistance genes in APEC strains (Ahmeda et al., 2013, Ozaki et al., 2017). However, there have been only few systematic studies in Korea. This study investigated the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics and antimicrobial resistance in recent APEC isolates from commercial broiler farms in Korea.

Materials and methods

Bacterial Strains

In 2018, liver swab samples were obtained using transport media (Yuhan Lab tech, Seoul, Korea) from chickens presenting with colibacillosis lesions from 60 commercial broiler farms across the country. Isolation of E. coli was carried out according to the Processing and Ingredients Specification of Livestock Products published by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (2014). Swab samples were transported to the laboratory in a cooler and inoculated into mEC (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Subsequently, enriched samples were streaked onto MacConkey agar (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 37°C for 18 to 20 h. Suspected E. coli colonies were identified using PCR as previously described (Candrian et al., 1991). All E. coli isolates were analyzed using PCR as described by Johnson et al., (2008) as the minimal predictors of APEC virulence; hlyF, iroN, iss, iutA, and ompT genes (Table 1). If several isolates from the same farm demonstrated the same antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, one of these isolates was randomly selected for further study. A total of 79 APEC isolates were included in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used for the amplification and DNA sequencing.

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

Base pair | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |||

| Virulence genes | ||||

| iroN | AATCCGGCAAAGAGACGAACCGCCT | GTTCGGGCAACCCCTGCTTTGACTTT | 553 | Johnson et al., 2008 |

| ompT | TCATCCCGGAAGCCTCCCTCACTACTAT | TAGCGTTTGCTGCACTGGCTTCTGATAC | 496 | Johnson et al., 2008 |

| hlyF | GGCCACAGTCGTTTAGGGTGCTTACC | GGCGGTTTAGGCATTCCGATACTCAG | 450 | Johnson et al., 2008 |

| Iss | CAGCAACCCGAACCACTTGATG | AGCATTGCCAGAGCGGCAGAA | 323 | Johnson et al., 2008 |

| iutA | GGCTGGACATCATGGGAACTGG | CGTCGGGAACGGGTAGAATCG | 302 | Johnson et al., 2008 |

| β-lactamases | ||||

| TEM | CATTTCCGTGTCGCCCTTATTC | CGTTCATCCATAGTTGCCTGAC | 800 | Dallenne et al., 2010 |

| SHV | CACTCAAGGATGTATTGTG | TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG | 885 | Briñas et al., 2002 |

| OXA | TTCAAGCCAAAGGCACGATAG | TCCGAGTTGACTGCCGGGTTG | 702 | Briñas et al., 2002 |

| CTX-M group I | GACGATGTCACTGGCTGAGC | AGCCGCCGACGCTAATACA | 499 | Pitout et al., 2004 |

| CTX-M group II | GCGACCTGGTTAACTACAATCC | CGGTAGTATTGCCCTTAAGCC | 351 | Pitout et al., 2004 |

| CTX-M group III | CGCTTTGCCATGTGCAGCACC | GCTCAGTACGATCGAGCC | 307 | Pitout et al., 2004 |

| CTX-M group IV | GCTGGAGAAAAGCAGCGGAG | GTAAGCTGACGCAACGTCTG | 474 | Pitout et al., 2004 |

| Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes | ||||

| aac(6′)-Ib | TGACCTTGCGATGCTCTATG | TTAGGCATCACTGCGTGTTC | 508 | Jiang et al., 2008 |

| aac(3)-II | TGAAACGCTGACGGAGCCTC | GTCGAACAGGTAGCACTGAG | 369 | Sandvang and Aarestrup, 2000 |

| ant(2″)-I | GGGCGCGTCATGGAGGAGTT | TATCGCGACCTGAAAGCGGC | 740 | Sandvang and Aarestrup, 2000 |

| Plasmid-mediated quinolone | ||||

| qnrA | TCAGCAAGAGGATTTCTCA | GGCAGCACTATTACTCCCA | 627 | Wang et al., 2003 |

| qnrB | CGACCTGAGCGGCACTGAAT | TGAGCAACGATGCCTGGTAG | 515 | Jiang et al., 2008 |

| qnrD | CGAGATCAATTTACGGGGAATA | AACAAGCTGAAGCGCCTG | 582 | Cavaco et al., 2009 |

| qnrS | ACCTTCACCGCTTGCACATT | CCAGTGCTTCGAGAATCAGT | 571 | Jiang et al., 2008 |

| qepA | CGTGTTGCTGGAGTTCTTC | CTGCAGGTACTGCGTCATG | 403 | Minarini et al., 2008 |

| Tetracyclines | ||||

| tetA | GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC | CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT | 956 | Sengeløv et al., 2003 |

| tetB | CTCAGTATTCCAAGCCTTTG | ACTCCCCTGAGCTTGAGGGG | 414 | Sengeløv et al., 2003 |

| tetC | CCTCTTGCGGGATATCGTCC | GGTTGAAGGCTCTCAAGGGC | 505 | Sengeløv et al., 2003 |

| Sulfonamide | ||||

| sul1 | CTTCGATGAGAGCCGGCGGC | GCAAGGCGGAAACCCGCGCC | 433 | Sandvang et al., 1998 |

| sul2 | CGGCATCGTCAACATAACC | GTGTGCGGATGAAGTCAG | 720 | Maynard et al., 2003 |

| Chloramphenicol | ||||

| catA1 | AGTTGCTCAATGTACCTATAACC | TTGTAATTCATTAAGCATTCTGCC | 547 | Van et al. 2008 |

| cmlA | CCGCCACGGTGTTGTTGTTATC | CACCTTGCCTGCCCATCATTAG | 698 | Van et al. 2008 |

| Phylogenetic group | ||||

| chuA | GACGAACCAACGGTCAGGAT | TGCCGCCAGTACCAAAGACA | 279 | Clermont et al., 2000 |

| yjaA | TGAAGTGTCAGGAGACGCTG | ATGGAGAATGCGTTCCTCAAC | 211 | Clermont et al., 2000 |

| TspE4C2 | GAGTAATGTCGGGGCATTCA | CGCGCCAACAAAGTATTACG | 152 | Clermont et al., 2000 |

Serogrouping

O serogrouping was carried out using 162 primer pairs, from O1 to O187 as previously described (Iguchi et al., 2015).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

An antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed using the disc diffusion method, according to the standards and interpretive criteria described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2017). The following antimicrobials were used (BD Biosciences): amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), cefadroxil (30 μg), cefazolin (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), cephalexin (30 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg). The E. coli strain ATCC 25922 was used for quality control purposes.

Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

Detection of antimicrobial resistance was performed with PCR using the primers listed in Table 1. Target antimicrobial resistance determinants were genes conferring resistance to β-lactam (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, and blaCTX), aminoglycoside [aac(6′)-Ib, aac(3)-II, and ant(2″)-I], plasmid-mediated quinolone (qnrA, qnrB, qnrD, qnrS, and qepA), tetracycline (tetA, tetB, and tetC), sulfonamide (sul1 and sul2), and chloramphenicol (catA1 and cmlA). β-Lactamase gene amplicons were sequenced with an automatic sequencer (Cosmogenetech, Seoul, Korea) and compared with those in the GenBank nucleotide database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool program available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (www.nici.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Phylogenetic Groups

APEC phylogenetic grouping was accomplished by multiplex PCR-based phylogenetic typing method as described by Clermont et al. (2000). Groups were assigned as follows: Group A, chuA-negative and TspE4.C2-negative; Group B1, chuA-negative and TspE4.C2-positive; Group B2, chuA -positive and yjaA-positive; and Group D, chuA-positive and yjaA-negative.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 25 (IBM, Seoul, Korea). The unpaired t test was used to investigate the relationship between phylogenetic groups and virulence genes from APEC isolates. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Serogrouping of APEC Isolates

Distribution of the O serogroups is shown in Table 2. Among 79 APEC isolates, 70 (88.6%) isolates were classified into 30 O serogroups, with 9 isolates remaining ungrouped. The most predominant serogroup was O78 (16 isolates, 20.3%), followed by O2 (7 isolates, 8.9%), O53 (7 isolates, 8.9%), O3 (3 isolates, 3.8%), O86 (3 isolates, 3.8%), and O174 (3 isolates, 3.8%).

Table 2.

Distribution of serotypes and antimicrobial resistance genes of avian pathogenic E. coli.

| O serogroup | No. of isolates | No. of isolates carried target gene (%) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactamases |

Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes |

Plasmid-mediated quinolone |

Tetracyclines |

Sulfonamide |

Chloramphenicol |

|||||||||

| blaTEM-1 | blaCTX-M-1 | blaCTX-M-15 | aac (3)-II | qnrA | qnrS | tetA | tetB | tetC | sul1 | sul2 | catA1 | cmlA | ||

| O78 | 16 | 6 (37.5) | - | - | 3 (18.8) | 1 (6.3) | - | 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | - | 1 (6.3) | 3 (18.8) | 1 (6.3) | - |

| O2 | 7 | -5 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (57.1) | - | - | - | 3 (42.8) | - | - |

| O53 | 7 | - | - | - | 1 (14.3) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O3 | 3 | 1 (33.3) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (33.3) | - | - |

| O86 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 1 (33.3) | - | 3 (100.0) | 1 (33.3) | - | - | - | - | 1 (33.3) |

| O174 | 3 | - | 3 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | 3 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O8 | 2 | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O9 | 2 | 2 (100.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | - | 2 (100.0) | - | 2 (100.0) | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - |

| O25 | 2 | 2 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100.0) | - | - | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | - | - |

| O45 | 2 | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | - |

| O115 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | - |

| O132 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - |

| O142 | 2 | 1 (50.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - | 2 (100.0) | - | 1 (50.0) |

| O11 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| O37 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O60 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| O76 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O88 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| O99 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| O103 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - |

| O104 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O111 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O146 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - |

| O158 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| O161 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O166 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - |

| O173 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| Ogp61 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ogp82 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - |

| Ogp143 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ONT4 | 9 | 2 (22.2) | - | 1 (11.1) | - | 2 (22.2) | - | 4 (44.4) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | - | 1 (11.1) | - | 3 (33.3) |

| Total | 79 | 23 (29.1) | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) | 4 (5.1) | 10 (12.7) | 2 (2.5) | 37 (46.8) | 10 (12.7) | 2 (2.5) | 5 (6.3) | 20 (25.3) | 5 (6.3) | 5 (6.3) |

O46 or O134.

O107 or O117.

O62 or O68.

Not grouped.

Not detected.

Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of APEC Isolates

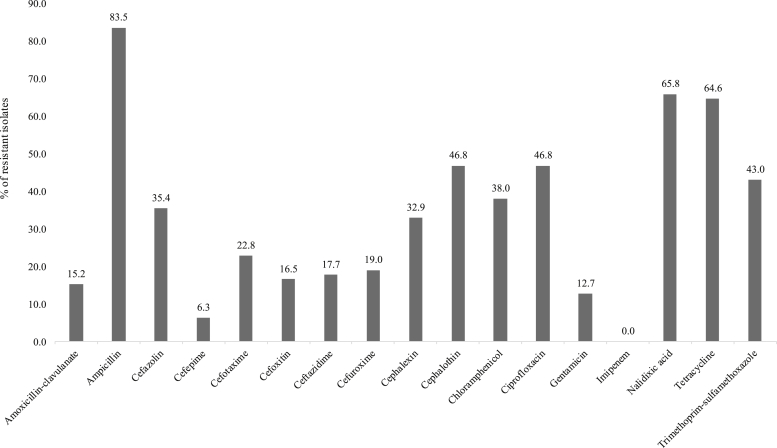

The 79 APEC isolates showed high resistance to ampicillin (66 isolates, 83.5%), nalidixic acid (52 isolates, 65.8%), tetracycline (51 isolates, 64.6%), cephalothin, and ciprofloxacin (37 isolates, 46.8% for each). Resistance to the third generation cephalosporins cefotaxime and ceftazidime and the fourth generation cefepime was detected in 18 isolates (22.8%), 14 isolates (17.7%), and 5 isolates (6.3%), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance of avian pathogenic E. coli.

Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

The prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes is shown in Table 2. Twenty-eight (35.4%) APEC isolates carried the following β-lactamase encoding genes: blaTEM-1 (23 isolates, 29.1%), blaCTX-M-1 (4 isolates, 5.1%), and blaCTX-M-15 (3 isolates, 3.8%). Three types of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes were examined, but aac(3)-II was only found in 4 (5.1%) APEC isolates. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes were detected in 12 (15.2%) APEC isolates as follows: qnrA (10 isolates, 12.7%) and qnrS (2 isolates, 2.5%). The qnrB, qnrD, and qeqA genes were not detected. Among tetracycline resistance genes, tetA (37 isolates, 46.8%) was the most prevalent one, followed by tetB (10 isolates, 12.7%) and tetC (2 isolates, 2.5%). The sul1 and sul2 sulfonamide resistance genes were detected in 5 isolates (6.3%) and 20 isolates (25.3%), respectively. The catA1 and cmlA chloramphenicol resistance genes were each found in 5 isolates (6.3%).

Phylogenetic Groups and Virulence Genes of APEC Isolates

Distributions of phylogenetic groups and virulence genes are shown in Table 3. Thirty-seven (46.8%) and six (7.6%) of the isolates belonged to groups D and B2, respectively, and presented as virulent extraintestinal E. coli. The 16 isolates from the predominant O78 serogroup were divided into groups A (8 isolates, 50.0%), B1 (4 isolates, 25.0%), and D (4 isolates, 25.0%). O2 and O53, followed by predominant serogroups, belonged to groups B2 or D. The virulence gene found most often was hlyF (74 isolates, 93.7%), followed by iutA (72 isolates, 91.9%), ompT (71 isolates, 89.9%), iroN (63 isolates, 79.9%), and iss (62 isolates, 78.5%). The distribution of the iss gene varied significantly between groups A/B1 and B2/D (P < 0.05). All group B2 isolates carried all 5 virulence genes.

Table 3.

Distribution of phylogenetic groups and virulence genes of avian pathogenic E. coli.

| Phylogenetic group | No. of isolates (%) | No. of isolates with each virulence gene (%) |

O Serotypes (no. of isolates) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hlyF | iroN | iss1 | iutA | ompT | |||

| A | 18 (22.8) | 16 (88.9) | 11 (61.1) | 11 (61.1) | 14 (77.8) | 16 (88.9) | O3 (3), O8 (1), O9 (1), O78 (8), O99 (1), O103 (1), Ogp14 (1)2, ONT (2)3 |

| B1 | 18 (22.8) | 18 (100.0) | 15 (83.3) | 12 (66.7) | 17 (94.4) | 16 (88.9) | O37 (1), O76 (1), O78 (4), O86 (1), O88 (1), O115 (2), O132 (1), O173 (1), Ogp6 (1)4, ONT (5) |

| B2 | 6 (7.6) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | O2 (5), O104 (1) |

| D | 37 (46.8) | 34 (91.9) | 31 (83.8) | 33 (89.2) | 35 (94.6) | 33 (89.2) | O2 (2), O8 (1), O9 (1), O11 (1), O25 (2), O45 (2), O53 (7), O60 (1), O78 (4), O86 (2), O111 (1), O132 (1), O142 (2), O146 (1), O158 (1), O161 (1), O166 (1), O174 (3), Ogp8 (1)5, ONT (2) |

| 79 | 74 (93.7) | 63 (79.7) | 62 (78.5) | 72 (91.1) | 71 (89.9) | ||

There were significant differences (P < 0.05) between A and B1 and between B2 and D.

O62 or O68.

Not grouped.

O46 or O134.

O107 or O117.

Discussion

APEC is associated with extraintestinal infections causing a range of disease known as colibacillosis in poultry. Although different O serogroups have been associated with colibacillosis, a limited number of serogroups, O1, O2, and O78, have been reported in chickens. In this study, O78 was the most predominant serogroup, followed by O2 which is similar to the results from previous studies (Wang et al., 2010b, Younis et al., 2017). ExPEC has a complex phylogenetic structure and carry a wide range of virulence factors (Sarowska et al., 2019). In particular, virulent extraintestinal stains are predominantly found in phylogenetic groups B2 and D, whereas commensal intestinal strains are found in groups A or B1 (Koga et al., 2015). Although only 25% of the O78 isolates belonged to group D, all O2 E. coli isolated in this study belonged to groups B2 or D. Serogroup O2 contain the most frequently isolated E. coli types from humans, along with serogroup O1 strains which were not detected in this study (Ciesielczuk et al., 2016). Delannoy et al. (2017) also reported that serogroup O2 E. coli from avian colibacillosis shares certain ExPEC virulence traits with human E. coli isolates. In this study, O53 was also a major serogroup, although it was not the predominant serogroup in the previous studies (Wang et al., 2010b, Solà-Ginés et al., 2015), and three isolates were grouped in O174, which was described in E. coli isolates from beef cattle (Mekata et al., 2014). In particular, all O53 and O174 isolates also belonged to phylogenetic groups B2 or D. These results indicate that the diversity of antigens presented by APEC may be members of a broad reservoir in domestic animals and humans.

Five essential virulence genes, hlyF (hemolysin), ompT (outer membrane protease), iroN (siderophore), iss (serum survival), and iutA (iron transport), are considered markers for APEC (de Oliveira et al., 2015, Jørgensen et al., 2019). Johnson et al. (2008) reported that APEC isolates from poultry clinically diagnosed with colibacillosis were positive for at least one of these 5 genes. In this study, all APEC isolates also carried at least one of these 5 genes, and the prevalence of genes was 78.5 to 93.7%. In particular, all the phylogenetic group B2 APEC isolates carried all 5 virulence genes, and the distribution of the iss gene was significantly different between groups A/B1 and B2/D (P < 0.05). The iss gene confers resistance to serum complement immune responses and increases the virulence of E. coli 100-fold in day-old chicks (Nolan et al., 2002). Presence of majority of APEC virulence genes, however, was independent of phylogenetic group.

Antimicrobial treatment has been considered to be an important determinant for reducing economic losses by colibacillosis. The APEC isolates from this study were resistant to antimicrobials critically important to human medicine, such as cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, and also showed resistance to antimicrobials such as ampicillin and tetracycline. In particular, cephalosporin-resistant isolates from poultry industries have been on the rise (APQA, 2017), and many β-lactamase–encoding genes have been described (Dallenne et al., 2010, Seo et al., 2019). In this study, 2 groups of β-lactamase genes were identified, of which blaTEM-1 was the most prevalent. The blaTEM-1 is widespread in E. coli from the poultry industry, including APEC isolates in Korea, but only codes for narrow-spectrum β-lactamases that can inactivate penicillins and aminopenicillins (Kim et al., 2007, Poirel et al., 2008, Seo et al., 2019). Extended-spectrum β-lactamases such as CTX-M that hydrolyze the characteristic β-lactam ring are of greater concern because they confer resistance to most β-lactam antimicrobials, including cephalosporins (Paterson and Bonomo, 2005), and can lead to increased resistance to other antimicrobials via horizontal gene transfer (Zurfluh et al., 2014, Hoepers et al., 2018). The blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-15 were also detected in this study. Although these genes have been previously reported in E. coli isolates from poultry industry (Jo and Woo, 2016, Seo et al., 2019), this study is the first to report detection of these genes in APEC in Korea.

Fluoroquinolones are also important antimicrobial agents for treating various types of infections in both humans and animals (Mellata, 2013, Dandachi et al., 2018). Several plasmid-encoded resistance genes related with Qnr-like proteins (qnrA, qnrD, and qnrS) which protect DNA from quinolone binding, the aac(6′)-Ib-cr acetyltransferase that modifies certain fluoroquinolones, and active efflux pumps (qepA) have been found in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates (Poirel et al., 2008, Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2016). In this study, only qnrA and qnrS were identified; however, these genes can be transferred to other strains by conjugative plasmids.

Aminoglycosides are frequently used in poultry industry in Korea (APQA, 2017), particularly gentamicin, which is commonly injected subcutaneously to vaccinate against Marek's or bursal disease in day-old chicks in hatcheries (Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency (APQA), 2017, Kim et al., 2018). The most common mechanism of aminoglycoside resistance is chemical modification by aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes (Garneau-Tsodikova and Labby, 2015). In this study, the aac(3)-II gene that encodes N-acetyltransferases was identified in 4 APEC isolates. Resistance to gentamicin is generally found in less than 20% of APEC isolates, similar to the prevalence of gentamicin-resistant E. coli isolated from poultry in Korea (APQA, 2017).

According to reports from the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Program, tetracyclines are the leading antimicrobials purchased in Korea (AQPA, 2017). In this study, 37 of the 51 tetracycline-resistant APEC isolates carried the tetA gene. The tetA and tetB genes encode efflux mechanisms and are the most common tetracycline resistance determinant in E. coli (Van et al., 2008, Diarra et al., 2016). The relative prevalence of tetA was higher than that of tetB or tetC in Korea (Kim et al., 2007, Dessie et al., 2013).

Sulfonamide resistance is conferred by sul1 and sul2 (Shin et al., 2014). In this study, the sul2 gene was detected in a larger proportion of the isolates, and the more frequent presence of sul2 than sul1 has also been reported in previous studies about E. coli from poultry industry (Guerra et al., 2003, Drugdová and Kmeť, 2013). The sul1 gene, however, is often found together with other antimicrobial resistance genes in gene cassettes in the carriable components of class 1 integrons (Poirel et al., 2008).

Chloramphenicol resistance is mediated enzymatically by the plasmid-located chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene catA1 and nonenzymatically by the chloramphenicol resistance gene cmlA (Kikuvi et al., 2007). In this study, 10 of the 30 chloramphenicol-resistant APEC isolates carried catA1 or cmlA, and these genes may also be cotransferred to bacteria with other antimicrobial resistance genes as previously reported (Travis et al., 2006). This study characterized a wide diversity of serogroups, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence properties in recent APEC isolates, and we recommend continuous monitoring to track APEC transmission in poultry farms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs Research Center Support Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (716002-7).

References

- Ahmeda A.M., Shimamoto T., Shimamoto T. Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from septicemic broilers. Poult. Sci. 2013;94:601–611. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency (APQA) Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency; Gimcheon, Republic of Korea: 2017. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Program. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri N.L., de Oliveira A.L., Tejkowski T.M., Pavanelo D.B., Matter L.B., Pinheiro S.R., Vaz T.M., Nolan L.K., Logue C.M., de Brito B.G., Horn F. Molecular characterization and clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains isolated from broiler chickens with colisepticemia. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:74–83. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briñas L., Zarazaga M., Sáenz Y., Ruiz-Larrea F., Torres C. Beta-lactamases in ampicillin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from foods, humans, and healthy animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3156–3163. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3156-3163.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candrian U., Furrer B., Höfelein C., Meyer R., Jermini M., Lüthy J. Detection of Escherichia coli and identification of enterotoxigenic strains by primer-directed enzymatic amplification of specific DNA sequences. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1991;12:339–351. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90148-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco L.M., Hasman H., Xia S., Aarestrup F.M. qnrD. A novel gene conferring transferable quinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky and Bovismorbificans strains of human origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:603–608. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00997-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchio L., Dotto G., Giacomelli M., Giovanardi D., Grilli G., Franciosini M.P., Trocino A., Piccirillo A. Class 1 and class 2 integrons in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli from poultry in Italy. Poult. Sci. 2012;94:1202–1208. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielczuk H., Jenkins C., Chattaway M., Doumith M., Hope R., Woodford N., Wareham D.W. Trends in ExPEC serogroups in the UK and their significance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;35:1661–1666. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O., Bonacorsi S., Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4555–4558. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2017. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, M100-S27. [Google Scholar]

- Dallenne C., da Costa A., Decré D., Favier C., Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:490–495. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandachi I., Chabou S., Daoud Z., Rolain J.M. Prevalence and emergence of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-, carbapenem- and colistin-resistant gram negative bacteria of animal origin in the Mediterranean basin. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1–26. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delannoy S., Beutin L., Mariani-Kurkdjian P., Fleiss A., Bonacorsi S., Fach P. The Escherichia coli serogroup O1 and O2 lipopolysaccharides are encoded by multiple O-antigen gene clusters. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessie H.K., Bae D.H., Lee Y.J. Characterization of integrons and their cassettes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from poultry in Korea. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:3036–3043. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dho-moulin M., Fairbrother J.M. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) Vet. Res. BioMed Central. 1999;30:299–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarra M.S., Giguère K., Malouin F., Lefebvre B., Bach S., Delaquis P., Aslam M., Ziebell K.A., Roy G. Genotype, serotype, and antibiotic resistance of sorbitol-negative Escherichia coli isolates from feedlot cattle. J. Food Prot. 2016;72:28–36. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drugdová Z., Kmeť V. Prevalence of β-lactam and fluoroquinolone resistance, and virulence factors in Escherichia coli isolated from chickens in Slovakia. Biologia. 2013;68:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dziva F., Stevens M.P. Colibacillosis in poultry: unravelling the molecular basis of virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in their natural hosts. Avian Pathol. 2008;37:355–366. doi: 10.1080/03079450802216652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau-Tsodikova S., Labby K.J. Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: overview and perspectives. Medchemcomm. 2015;7:37–54. doi: 10.1039/C5MD00344J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guabiraba R., Schouler C. Avian colibacillosis: still many black holes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015;362:1–8. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra B., Junker E., Schroeter A., Malorny B., Lehmann S., Helmuth R. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in German Escherichia coli isolates from cattle, swine and poultry. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;52:489–492. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoepers P.G., Silva P.L., Rossi D.A., Valadares Júnior E.C., Ferreira B.C., Zuffo J.P., Koerich P.K., Fonseca B.B. The association between extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and ampicillin C (AmpC) beta-lactamase genes with multidrug resistance in Escherichia coli isolates recovered from turkeys in Brazil. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018;59:396–401. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2018.1468070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi A., Iyoda S., Seto K., Morita-Ishihara T., Scheutz F., Ohnishi M. Escherichia coli O-genotyping PCR: a comprehensive and practical platform for molecular O serogrouping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:2427–2432. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00321-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Zhou Z., Qian Y., Wei Z., Yu Y., Hu S., Li L. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6')-Ib-cr in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:1003–1006. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.J., Woo G.J. Molecular characterization of plasmids encoding CTX-M β-lactamases and their associated addiction systems circulating among Escherichia coli from retail chickens, chicken farms, and slaughterhouses in Korea. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;26:270–276. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1507.07048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen S.L., Stegger M., Kudirkiene E., Lilje B., Poulsen L.L., Ronco T., Pires Dos Santos T., Kiil K., Bisgaard M., Pedersen K., Nolan L.K., Price L.B., Olsen R.H., Andersen P.S., Christensen H. Diversity and population overlap between avian and human Escherichia coli belonging to sequence type 95. mSphere. 2019;4:e00333-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00333-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T.J., Wannemuehler Y., Doetkott C., Johnson S.J., Rosenberger S.C., Nolan L.K. Identification of minimal predictors of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli virulence for use as a rapid diagnostic tool. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:3987–3996. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00816-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuvi G.M., Schwarz S., Ombui J.N., Mitema E.S., Kehrenberg C. Streptomycin and chloramphenicol resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolates from cattle, pigs, and chicken in Kenya. Microb. Drug Resist. 2007;13:62–68. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.E., Jeong Y.W., Cho S.H., Kim S.J., Kwon H.J. Chronological study of antibiotic resistances and their relevant genes in Korean avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:3309–3315. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01922-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.J., Park J.H., Seo K.H. Comparison of the loads and antibiotic-resistance profiles of Enterococcus species from conventional and organic chicken carcasses in South Korea. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:271–278. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga V.L., Rodrigues G.R., Scandorieiro S., Vespero E.C., Oba A., de Brito B.G., de Brito K.C.T., Nakazato G., Kobayashi R.K.T. Evaluation of the antibiotic resistance and virulence of Escherichia coli strains isolated from chicken carcasses in 2007 and 2013 from Paraná, Brazil. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:479–485. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutful Kabir S.M. Avian colibacillosis and salmonellosis: a closer look at epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and public health concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010;7:89–114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C., Fairbrother J.M., Bekal S., Sanschagrin F., Levesque R.C., Brousseau R., Masson L., Larivière S., Harel J. Antimicrobial resistance genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O149:K91 isolates obtained over a 23-year period from pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3214–3221. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3214-3221.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekata H., Iguchi A., Kawano K., Kirino Y., Kobayashi I., Misawa N. Identification of O serotypes, genotypes, and virulotypes of shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli Isolates, including non-O157 from beef cattle in Japan. J. Food Prot. 2014;77:1269–1274. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellata M. Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013;10:916–932. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minarini L.A., Poirel L., Cattoir V., Darini A.L., Nordmann P. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants among enterobacterial isolates from outpatients in Brazil. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62:474–478. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety . Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; Cheongju, Republic of Korea: 2014. Processing Standards and Ingredient Specifications for Livestock Products. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan L.K., Horne S.M., Giddings C.W., Foley S.L., Johnson T.J., Lynne A.M., Skyberg J. Resistance to serum complement, iss, and virulence of avian Escherichia coli. Vet. Res. Commun. 2002;103:101–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1022854902700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J.Y., Kang M.S., Kim J.M., An B.K., Song E.A., Kim J.Y., Shin E.G., Kim M.J., Kwon J.H., Kwon Y.K. Characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from laying hens with colibacillosis on 2 commercial egg-producing farms in Korea. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:1948–1954. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira A.L., Rocha D.A., Finkler F., de Moraes L.B., Barbieri N.L., Pavanelo D.B., Winkler C., Grassotti T.T., de Brito K.C., de Brito B.G., Horn F. Prevalence of ColV plasmid-linked genes and in vivo pathogenicity of avian strains of Escherichia coli. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:679–685. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki H., Matsuoka Y., Nakagawa E., Murase T. Characteristics of Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chickens with colibacillosis in commercial farms from a common hatchery. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:3717–3724. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson D.L., Bonomo R.A. Clinical update extended-spectrum beta-lactamases : a clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:657–686. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J.D., Hossain A., Hanson N.D. Phenotypic and molecular detection of CTX-M-beta-lactamases produced by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:5715–5721. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5715-5721.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Madec J.-Y., Lupo A., Schink A.–K., Kieffer N., Nordmann P., Schwarz S. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Environ. Health. 2008;70:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martínez J.M., Machuca J., Cano M.E., Calvo J., Martínez-Martínez L., Pascual A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: two decades on. Drug Resist. Updat. 2016;29:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvang D., Aarestrup F.M., Jensen J.B. Characterisation of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998;160:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarowska J., Futoma-Koloch B., Jama-Kmiecik A., Frej-Madrzak M., Ksiazczyk M., Bugla-Ploskonska G., Choroszy-Krol I. Virulence factors, prevalence and potential transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from different sources: recent reports. Gut Pathog. 2019;11:10. doi: 10.1186/s13099-019-0290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvang D., Aarestrup F.M. Characterization of aminoglycoside resistance genes and class 1 integrons in porcine and bovine gentamicin-resistant Escherichia coli. Microb. Drug Resist. 2000;6:19–27. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2000.6.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouler C., Schaeffer B., Brée A., Mora A., Dahbi G., Biet F., Oswald E., Mainil J., Blanco J., Moulin-Schouleur M. Diagnostic strategy for identifying avian pathogenic Escherichia coli based on four patterns of virulence genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:1673–1678. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05057-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengeløv G., Agersø Y., Halling-Sørensen B., Baloda S.B., Andersen J.S., Jensen L.B. Bacterial antibiotic resistance levels in Danish farmland as a result of treatment with pig manure slurry. Environ. Int. 2003;28:587–595. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(02)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo K.W., Shim J.B., Lee Y.J. Comparative genetic characterization of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from a layer operation system in Korea. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:1472–1479. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H.W., Lim J., Kim S., Kim J., Kwon G.C., Koo S.H. Characterization of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance genes and their relatedness to class 1 integron and insertion sequence common region in gram-negative bacilli. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;25:137–142. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1409.09041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solà-Ginés M., Cameron-Veas K., Badiola I., Dolz R., Majó N., Dahbi G., Viso S., Mora A., Blanco J., Piedra-Carrasco N., González-López J.J., Migura-Garcia L. Diversity of multi-drug resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) causing outbreaks of colibacillosis in broilers during 2012 in Spain. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis R.M., Gyles C.L., Reid-Smith R., Poppe C., McEwen S.A., Friendship R., Janecko N., Boerlin P. Chloramphenicol and kanamycin resistance among porcine Escherichia coli in Ontario. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58:173–177. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno T., Han D., Jang J., Widmer K., Ko G., Sadowsky M.J., Hur H.-G. Genotypic and phenotypic trends in antibiotic resistant pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from humans and farm animals in South Korea. Microbes Environ. 2011;26:198–204. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van T.T.H., Chin J., Chapman T., Tran L.T., Coloe P.J. Safety of raw meat and shellfish in Vietnam: an analysis of Escherichia coli isolations for antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008;124:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Tran J.H., Jacoby G.A., Zhang Y., Wang F., Hooper D.C. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Shanghai, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2242–2248. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2242-2248.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Liao X., Zhang W., Jiang H., Sun J., Zhang M. Prevalence of serogroups, virulence genotypes, antimicrobial resistance, and phylogenetic background of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in South of China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7:1099–1106. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tang C., Yu X., Xia M., Yue H. Distribution of serotypes and virulence-associated genes in pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from ducks. Avian Pathol. 2010;39:297–302. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.495742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younis G., Awad A., Mohamed N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial susceptibility of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chickens. Vet. World. 2017;10:1167–1172. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.1167-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfluh K., Wang J., Klumpp J., Nüesch-Inderbinen M., Fanning S., Stephan R. Vertical transmission of highly similar blaCTX-M-1-harbouring IncI1 plasmids in Escherichia coli with different MLST types in the poultry production pyramid. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]