Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The colonic mucosa constitutes a critical barrier and a major site of immune regulation. The immune system plays important roles in cancer development and treatment, and immune activation caused by chronic infection or inflammation is well-known to increase cancer risk. During tumor development, neoplastic cells continuously interact with and shape the tumor microenvironment (TME) which becomes progressively immunosuppressive. The clinical success of immune checkpoint blockade therapies (ICBs) is limited to a small set of CRCs with high tumor mutational load and tumor infiltrating T cells. Induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD), a type of cell death eliciting an immune response, can therefore help break the immunosuppressive TME, engage the innate components and prime T cell-mediated adaptive immunity for long-term tumor control. In this review, we discuss the current understanding of ICD induced by antineoplastic agents, the influence of driver mutations, and recent developments to harness ICD in colon cancer. Mechanism-guided combinations of ICD-inducing agents with immunotherapy and actionable biomarkers will likely offer more tailored and durable benefits to colon cancer patients.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cancer-related killer worldwide, with an increased incidence projected in many developing countries. The survival rate of metastatic CRC remains low at around 11% [1]. Most sporadic CRCs develop from benign pre-neoplastic polyp-like lesions following somatic inactivation of the APC tumor suppressor and progress with a series of genetic and epigenetic alterations accumulated over years or decades in KRAS/BRAF, SMAD/TGFBR2, p53, and PIKCA3 among others [2]. Existing research has highlighted critical interactions between the immune system and emerging tumor cells, and the complex changes in the tumor microenvironment (TME) during cancer progression towards immunosuppression and loss of immunosurveillance [3]. Cancer cell-intrinsic mechanisms are believed to play a key role in shaping local immune landscapes and therapeutic responses [4]. The breakthrough in immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICBs), such as antibodies against Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1), Programmed Death Ligand 1(PD-L1), and Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte associated Antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [5,6], supports immune normalization or restoration in tumor control [7]. However, T-cell activating therapies have limited success in solid tumors. Induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD), a type of cell death eliciting an immune response, is, therefore, an attractive approach to break the immunosuppressive TME and re-establish immune surveillance by engaging both the innate and adaptive components [8,9]. ICD can be induced by a variety of chemopreventive agents, radiation, chemotherapeutics, and targeted therapies, and is shown to be critical for the antitumor effects in preclinical models through a systemic antitumor immunity [10]. A better mechanistic understanding of drug-induced cell death and immunologic consequences, particularly the influence of oncogenic signals, will likely hold the key to help devise more efficacious and precise strategies to prevent and treat colon cancer. This review will discuss recent findings that can help advance the research and clinical development of ICD in this direction.

2. Changing immune landscapes during CRC development

Immunogenomic analysis of over 10,000 tumors across 33 diverse cancer types using data compiled in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed that tumor immune landscapes differ greatly between and within cancer types [4,11]. Driver mutations can dictate the immune contexture of tumors, and their bidirectional interactions shape tumor evolution and therapeutic response [4,11]. The accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes in cancer cells reflects clonal expansion [12] driven by selective pressure including that from immune cells and neutral drift intrinsic to normal intestinal stem cell replacement [13,14]. CRC progression is associated with changes in the composition, density, and location of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) that predict clinical outcomes. CRCs heavily infiltrated with TILs and natural killer cells (NKs) have a more favorable prognosis, and the infiltration of CD3+, CD8+, or CD45RO memory T cells is a strong prognostic factor [15,16]. Tumor-suppressive role of immunosurveillance has also been established in mice. Immunodeficient IFN-γ−/−, RAG2−/− or Prkdcscid (better known as severe combined immune deficiency, or SCID) mice are more susceptible to chemically-induced and spontaneous tumorigenesis [17], or intestinal polyposis driven by APC loss [18].

Immunosurveillance is gradually diminished during malignant transformation, from tumor cell elimination, equilibrium, and finally to escape accompanied by ongoing immune editing [3,19,20]. The escape phase is associated with poor prognosis and characterized by diminished tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), type I helper (Th1) CD4+ T lymphocytes, and NKs, and an increased presence of immunosuppressive regulatory T (Treg) and myeloid cells producing TGF-β and interleukin-10 in the TME [21]. Escaping from immunosurveillance occurs on tumor cells due to the loss of tumor antigens, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins, sensitivity to the complement system, T cell or NK cell lysis, and production of immunosuppressive molecules such as TGF-β, indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), PD-L1, PD-L2 or CTLA-4 [5,6], making tumor cells a poor target for an immune attack [3].

3. Immunogenic cell death of cancer cells

ICD is a type of cell death that primes a systemic immune response [8]. ICD is essential for the host defense against viral and bacterial infections and can be induced by various anticancer agents in a context-dependent manner [9]. The role and regulation of ICD in cancer therapy remains an active area of investigation.

Death by many ways

Cell death is an irreversible fate, highly regulated and stimulus-specific [22]. Apoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved form of cell death important for normal development in the animal kingdom. Apoptosis is regulated by mitochondria-dependent intrinsic and death receptor-dependent extrinsic pathways, converging on the activation of executioner caspases-3 and −7 [23,24]. During transformation, neoplastic cells frequently become resistant to apoptosis via genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, driving the accumulation of additional oncogenic events and therapeutic resistance [25,26].

Several forms of nonapoptotic cell death have been discovered, including necroptosis, the most extensively studied in inflammation and cancer [22,27]. Necroptosis can be initiated upon activation of the extended TNF-α receptor family on the cell surface, and propagated through the receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinases, RIP1 and/or RIP3 [28–30], particularly when apoptosis is compromised due to blocked activation of caspase-8 or other caspases [31,32]. The cell death is then executed by plasma membrane pores formed by Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like protein (MLKL) [33], and amplified by autocrine TNF-α production [34,35]. Intracellular pathogens, lipid oxidation, loss of attachment, increased reactive oxygen species, PARP-1 hyperactivation mediated-bioenergetic failure, or prolonged mitotic arrest can trigger pyroptosis, ferroptosis, anoikis, autophagic cell death, parthanatos, and mitotic death, respectively [22].

Immunogenic cell death

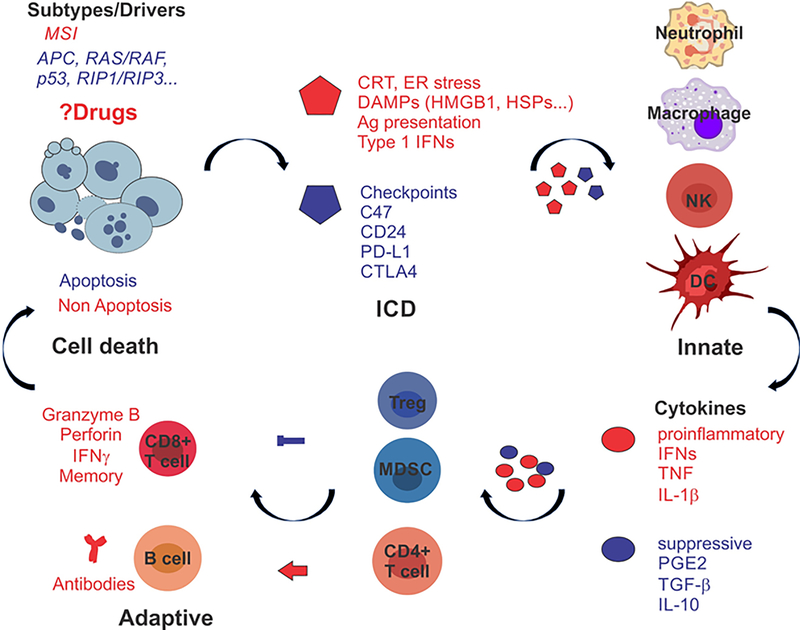

ICD is associated with several hallmarks in dying cells, such as calreticulin (CRT or CLAR) cell-surface translocation, extracellular release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as HMGB1, heat shock proteins, or ATP, and the production of Type I interferons (IFNs) among others [36–38]. DAMPs attract innate immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and NKs through various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), and promote their maturation and/or activation, including dead cell clearance, optimal antigen uptake, processing and presentation, cytokine production, and cell killing within days [9]. Cross-priming of CD8+ CTLs is triggered by mature DCs and γδT cells in an IL-1β- and IL-17-dependent manner. Primed CTLs then elicit a direct cytotoxic response to kill tumor cells through the generation of IFN-γ, perforin-1, and granzyme B, followed by memory (Figure 1). T-cell mediated immunity is regulated by a constant and complex interplay between stimulatory and inhibitory signals to promote antigen-specific adaptive response while avoiding autoimmunity [9].

Figure 1. Heating up “cold” tumors with the right kill.

MSI and MSS CRCs display different immune TME and response to ICBs while sharing mutations in several major drivers. Anticancer drugs often induce mixed types of cell death and immunological outcomes, which are strongly influenced by tumor intrinsic factors (genetic and epigenetic) such as MSI, mutant APC, KRAS/BRAF or p53, or silenced RIP1/RIP3 as detailed in the text. ICD breaks the “cold’ TME, engages innate response to prime adaptive response required for long-term tumor control. The “right” kill is expected to be dominated by pro-inflammatory (red) effectors (ICD markers and cytokines), and cells (i.e., CD8+ T cells) and over suppressive (blue) effectors and cells (i.e., Treg and MDSCs).

Calreticulin plasma membrane exposure

CRT is a 46-kDa, Ca2+-binding, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone. CRT translocation to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane is considered an “eat-me” signal, occurs during ER stress-associated cell death and is mediated by endocytosis and the protein complex SNAP Receptor (SNARE) [38–40]. ER stress is an arm of the evolutionarily conserved and multipronged integrated stress response (ISR) [41], characterized by the phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) by PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) in response to unfolded proteins. Exposed CRT is recognized and engulfed by cells expressing CD91, also known as LDL Receptor Related Protein 1 (LRP1) (e.g., DCs and macrophages). CRT binding to CD91 triggers a cascade of events to facilitate the recruitment of antigen-presenting cells (e.g., DCs), optimal antigen presentation, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) and activation of type 17 helper T (Th17) cells [42].

Extra Cellular DAMP Release

HMGB1 is an abundant DNA minor groove binding protein, and its release from dying cells triggers a strong inflammatory response [43,44]. HMGB1 binds to several PRRs including Toll-like receptor 4, (TLR4), receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) to activate MAPKs (p38 and ERK1/2), and NF-κB in DCs. HMGB1 also facilitates DC maturation, migration, presentation of tumor-associated antigens to T cells, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Release of chaperones such as HSP70 and HSP90 from dying cells can also stimulate tumor antigen uptake, DC maturation, and function [44].

ATP secretion from dying tumor cells triggers an immune response and requires autophagy [45,46]. Extracellular ATP from dying tumor cells generates a strong “find-me” signal for DCs and macrophages, upon its binding to purinergic receptor P2Y2 on the target cells [47], to promote DC maturation and macrophage expansion [47]. In fact, increased ATP hydrolysis by ectonucleotidases (e.g., CD39 and CD73) in the TME [48,49] blunted TILs and tumor response to chemotherapy [50].

Type 1 IFN response

Virtually all cells can secrete Type 1 interferons (IFNs) upon viral or bacterial infections and the activation of nucleic acid (RNA and DNA) sensors such as TLR3, TLR7, TLR9, RIG1/MDA5-MAVs (Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene 1 Protein/Melanoma Differentiation-Associated protein 5 Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein), and cGAS-STING (cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase -Stimulator of interferon genes) [51]. The binding of Type 1 IFNs (alpha and beta) to IFNAR1–IFNAR2 heterodimers activates JAK/STAT signaling to establish an antiviral state, from inhibiting viral production, activating antigen presentation and innate immunity to kill and remove infected cells, and ultimately to mounting adaptive immunity against future infections [51,52]. Type 1 IFN response regulates highly cell-type specific expression of numerous Interferon Stimulated Genes (ISGs), and controls the production and function of numerous chemokines, cytokines, and immune cells via crosstalk with TNF-α/NF-κB and IL-18/IL-1β pathways. The host and immune cell-dependent roles of Type 1 IFN response in controlling infection and tumor growth are well-established [51,53], while its tumor-intrinsic role is less understood.

ICD defined in vivo

The type of cell death can influence immunologic outcomes in animals. Apoptosis is considered to be less immunogenic due to the lack of ICD markers and direct suppression of necroptosis, TNF-α/NFκB, or type 1 IFN signaling as a result of caspase-mediated cleavage of RIP1 [31,32] or cytoplasmic RNA/DNA sensors [54]. However, no single type of cell death or marker defines ICD, and mixed types of cell death and shared regulators or effectors are often observed [22]. As such, tumor cell ICD is defined by two major criteria in immunocompetent mice [55,56]. First, tumor cells upon ICD induction in vitro without any adjuvant function as a vaccine to protect mice against a subsequent challenge with live tumor cells of the same type. Second, antitumor immunity in vivo is associated with the infiltration of immune effector cells into the TME and is dependent on the host immune system and CD8+ cells.

4. ICD-inducing agents in CRC prevention and therapy

Emerging evidence supports that the clinical activity of most, if not all, conventional and targeted antineoplastic agents currently used in humans can be attributed to the re-establishment of immune surveillance and reactivation in the TME [10]. These agents can induce ICD and alter TILs abundance and composition, which is associated with more favorable therapeutic responses or prognosis in cancer patients [9]. However, a detailed mechanistic understanding of ICD in relation to often highly variable in vivo efficacy is lacking. The use of more physiological and immune-competent models, such as APCMin mice and MC-38 and CT-26 syngeneic models, will help explain how preventive and therapeutic agents work under substantially different oncogenic signals and the TME [57,58]. We will focus our discussion on CRC relevant agents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Drug-induced ICD in colon cancer.

| ICD inducer | Model | Mechanism and *Biomarker | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention | |||

| NSAIDs (Sulindac, Aspirin) | Human, CRC cells, APCMin mice | apoptosis, ER stress, IFN and IL-8 signaling, increased TILs, decreased Tregs and PEG2 | [62–70] |

| Metformin | Human, CT-26 syngeneic model | apoptosis, increased MHC-1 expression and T-cell functions | [74–77] |

| Radiation and chemotherapy | |||

| Radiation | CRC patients, CT-26 and MC-38 syngeneic models | cell death, the abscopal effect, modulated peptide repertoire, enhanced MHC-1 expression and host type 1 IFN response | [78–80] |

| Chemotherapy (5-FU, Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin, Doxorubicin) | CRC cells, CT-26 and MC-38 syngeneic models | cell death, increased surface CRT, MHC-1 expression, and TILs, especially in combination | [37,40,86,87] |

| Targeted therapies | |||

| VEGF antibodies (Bevacizumab) | mCRC patients | Increased B-cell and T-cell compartments | [92] |

| EGFR antibody (Cetuximab) | mCRC patients, CRC cells, and CT-26 | Th1-cytotoxic phenotype, CTL-dependent, DC phagocytosis, *mutant KRAS/BRAF for exclusion | [93–95] |

| Regorafenib | mCRC patients, CRC cells, xenografts and CT-26 syngeneic model | apoptosis, enhanced anti-tumor immunity via macrophage modulation | [96–98] |

| PI3K inhibitor | CT-26 syngeneic model | enhanced activity of effector CD8+ T-cells | [99] |

| Emerging agents | |||

| Inhibitors of proteasome, HSP, GRP78, mTOR and BET | CRC cells, xenografts, 3D spheroids | cell death, ER stress, single agent or in combination | [101–108] |

| Natural compounds, epigenetic drugs and oncolytic viruses | CRC cells, CT-26 syngeneic | cell death, increased CD8+ T cells, CRT exposure and HMGB1 release, and IFN signaling | [87,109–114] |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor | |||

| Anti-PD1 | mCRC patients | T-cell activation in the TME, *MSI, high TMB, pretreatment TILs for inclusion | [118,119] |

CRC preventive agents

A variety of pharmacological agents, natural products, and dietary components have been shown to have CRC preventive activity in human studies and animal models. The most potent and best studied are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [59–61]. NSAIDs induce apoptosis selectively in APC-deficient and Myc-high preneoplastic stem and cancer cells via ER stress, involving the crosstalk of the death receptor and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways [62–65]. The efficacy of NSAID in human CRC patients is associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in interferon and interleukin-8 (IL-8) signaling [66–68], as well as increased active TILs and reduced immunosuppressive Treg cells [69] or cytokines [70] in the TME, and increased MHC expression in tumor cells [71]. In APCMin mice, NSAIDs promoted the antitumor M1 polarization of macrophages [72] and inhibited COX2-mediated production of prostaglandin E2(PGE2) and immunosuppressive Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs), Treg and TH2 cells [73]. The anti-diabetic drug metformin reduced CRC risk in epidemiological and preclinical studies [74], which is associated with growth suppression, apoptosis induction, and improved MHC1 expression and T-cell functions [75–77].

Radiation and chemotherapy

Radiation therapy and most conventional chemotherapeutic agents trigger DNA damage ultimately apoptotic and non-apoptotic cell death [23]. Besides direct cytotoxicity to tumor cells caused by non-reparable double-stranded DNA breaks, the abscopal effect of radiation therapy has been well-recognized with systemic antitumor immunity capable of shrinking established tumors that have not been subjected to treatment. Radiation can modulate the peptide repertoire, enhance MHC class I expression and response to immunotherapy in syngeneic tumor models such as MC-38 and CT-26 [78–80]. cGAS-STING-dependent Type 1 IFN response in the host is important in these preclinical models. IFN therapy (Type 1 and 2), however, has not been efficacious in solid tumors.

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a pyrimidine analog that inhibits thymidylate synthase required for nucleotide synthesis [81,82], and is standard of care for CRC patients. The platinum drug Oxaliplatin or the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan is often given in combination with 5-FU as FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) or FOLFIRI (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan) for improved efficacy [83]. 5-FU or irinotecan treatment induced ICD hallmarks CRT exposure and MHC-1 expression in the mouse colon cancer cell line CT-26 and human cancer cells [40]. Genetic ablation of Caspase-3 enhanced RIP1 dependent necroptosis and response to 5-FU in HCT 116 cells and xenografts [84]. Interestingly, agents with similar chemical structures may have very different immunological consequences [85]. Oxaliplatin, but not cisplatin, acts as a potent ICD inducer in CRC syngeneic murine models by triggering ER stress and CRT exposure [37,86]. A combination of cytotoxic agents such as doxorubicin [87] or 5-FU and radiation [88] can potentiate ICD, CD8+ CTLs and therapeutic responses in mice.

Targeted therapy

Several targeted drugs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for CRC treatment, including the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody bevacizumab, the anti-EGFR antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab, and the multi-kinase inhibitor regorafenib [89,90]. These agents inhibit RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling and can lead to transient remissions but rarely cures, as feedback activation of survival pathways and suppression of apoptosis leads to a drug-tolerant state and resistance [91]. Bevacizumab-based first-line therapy increased T and B cell compartments in metastatic CRC (mCRC) patients [83,92]. Cetuximab with chemotherapy increased circulating DCs, NKs, memory T cells, and cancer-specific CTLs in mCRC patients, and promoted ER stress and phagocytosis by DCs in vitro [93–95]. Regorafenib promoted apoptosis and NF-κB activation in human CRC models [96,97], and enhanced anti-tumor immunity in mCRC patients [98]. PI3Kα/δ inhibition was shown to promote anti-tumor immunity through direct enhancement of effector CD8(+) T-cell activity in the CT-26 syngeneic model [99].

Emerging therapeutic agents

ER stress inducers including FDA-approved cancer drugs can trigger ICD. Bortezomib is a specific inhibitor of the 26S proteasome subunit and induces apoptosis of various cancer cells, associated with enhanced phagocytosis and DC cross-presentation of tumor antigens to T cells [100]. In preclinical CRC models, bortezomib, HSP inhibitors, mTOR/PI3K inhibitors, BET inhibitors or a GRP78 inhibitor induced ER stress-associated cell death [101–106]. Interestingly, several drug combinations were particularly effective in killing CRCs harboring mutant KRAS/BRAF or SPOP through elevated ER stress and DR5 expression [107,108]. Various natural compounds, epigenetic drugs, and oncolytic viruses can also induce or enhance ICD [109–111]. Anticancer efficacy observed was associated with increased CD8+ T cells [87], tumor cell CRT exposure and HMGB1 release [112], or activation of endogenous retroviruses and IFN signaling [113,114].

5. ICD regulation by cancer intrinsic mechanisms in CRC

Therapeutic responses to anticancer agents and induction of ICD hallmarks are highly variable, lacking clinically actionable biomarkers (Table 1). Studies on cancer-immune interactions reveal that virtually every step from innate to adaptive immunity can be altered in the TME, which differs significantly among cancers and cancer types [3]. A transcriptomic meta-analysis defined five major CRC subtypes with distinct mutational, growth, stroma, and immune profiles [85,115], supporting tumor-intrinsic mechanisms in shaping disease heterogeneity, local immune landscapes and therapeutic responses [4]. We will focus on CRC-relevant ICD mechanisms in the context of differential therapeutic responses and “Hot” and “Cold” tumors (Figure 1).

Mismatch Repair Deficiency

Approximately 15% of CRCs display microsatellite instability (MSI) due to mutation or promoter methylation in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, and PMS2. MSI is characterized by highly elevated DNA replication errors in microsatellite repeats in both noncoding and coding sequences [2]. MSI CRCs have high tumor mutational burden (TMB), more T-cell inflamed or “Hot” TME [116,117], and respond favorably to ICBs such as anti-PD-1 [118,119]. However, MSI CRCs respond poorly to 5-FU-based chemotherapy [120]. Nearly all microsatellite stable (MSS) CRCs and approximately 30–50% of MSI CRCs do not respond to ICBs, and relatively few tumor-specific antigens have been confirmed [121,122]. Resistance mechanisms in MSI tumors appear to be complex, most notably mutational inactivation of MHC-1 and IFN regulators such as B2M, NLRC5, JAK1/2 (over 60%) [123–125], Transforming Growth Factor β Receptor 2 (TGFBR2), PTEN, Asteroid Homolog 1 (ASTE1), Caspase 5 [117], and BAX [62]. ICB resistance is associated with the lack of pretreatment T cells or “inflamed” CD8+ T cell and DC gene signature [126,127].

Wnt/Myc

Hyperactivation of Wnt/β-catenin and oncogenic Myc is an early and near-universal event in CRCs [2] and is found to be strongly associated with immunosuppressive TME, absence of TILs, and ICB resistance across cancer types [128,129]. Wnt/β-catenin/Myc signaling impairs a multitude of immune functions in the TME by reducing MHC-1 expression [130] and NKG2D ligand in tumor cells [131], as well as activation and expansion of cytotoxic T-cells [132] through inhibitory signals and metabolic deprivation [133,134]. Wnt/Myc also upregulates T cell inhibitory PD-L1, as well as “don’t-eat-me” signals CD47 [135] and CD24 [136], whose binding to their respective receptors signal-regulatory protein α (SIRPα), and Siglec-10 on immune cells triggers phagocytosis checkpoints and protects cancer cells from immunosurveillance [137]. CD47 was also upregulated by TNF/NF-κB [138] and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) [139]. High mRNA expression of CD47 [140] and CD24 [136] is associated with poor survival in cancer patients. Myc can inhibit IFNβ production via direct binding to the STAT1 promoter [141].

Mutant KRAS/BRAF

KRAS and BRAF mutations are mutually exclusive and found in over 50% of CRCs. Hot spots include codons 12, 13, 61, 146 in KRAS, and codon 600 in BRAF, leading to constitutive RAF/MAPK and PI3K signaling [2]. Mutant KRAS/BRAF is a significant resistance mechanism in CRCs [142] in response to front-line therapy, targeted therapies against EGFR [143–146], mutant BRAF [147], and mTOR [102], which activates compensatory survival pathways and blocks apoptosis. Mutant KRAS was recently shown to drive resistance to immune therapy through IRF2 loss- and CXCL3/CXCR2-dependent recruitment of MDSCs [148]. Mutant KRAS also cooperated with Myc to promote CLL9 and IL-23-dependent inflammation and stroma immunosuppression [149] and is associated with more frequent JAK1/2 or B2M mutations [124]. Mutant BRAF was reported to inhibit antigen presentation and T cell infiltration in melanoma [150]. These findings suggest defective ICD as a potential therapeutic target in CRCs harboring mutant KRAS/BRAF.

Compromised cell death, genome integrity, and immune recognition

Widespread mutational inactivation of p53 and activation of RAS/RAF and PI3K/AKT pathways in CRC impair DNA damage repair [151], removal of cells with chromosomal instability (CIN) [152], and apoptosis, and leads to therapeutic resistance (reviewed by [91]). Mutant FBW7 was recently shown to cause resistance to targeted therapies in CRC preclinical models by blocking drug-induced Mcl-1 phosphorylation and its subsequent degradation or dissociation from BH3-only proteins [97,153,154]. Epigenetic silencing of RIP1 or RIP3 blocks necroptosis induced by anticancer agents including 5-FU in CRC cells (reviewed by [155]).

Nearly all MSS CRCs display CIN at early stages [2,156,157], with little or no response to ICBs even in combination trials with conventional or targeted therapies [158]. CIN has been shown to activate the cGAS-STING pathway to promote genomic heterogeneity and inflammatory signaling [159]. Compromised Type 1 IFN response can lead to resistance to radiation, anthracycline-based chemotherapy and immune therapy [121,160–162]. Besides rare JAK1/2 mutations [123–125], the cause appears to be mostly non-genetic, such as promoter methylation and reduced expression of cGAS or STING [163] and loss of INFAR1 protein expression [164]. Elevated T-cell inhibitory signals such as CTLA-4, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), PD-1, TIM-3 are also attributable to epigenetic mechanisms such as loss of DNA methylation or suppressive histone marks in CRC [165].

Harnessing ICD via combination therapies

Cancer immunotherapy comes in different forms, including immune effectors such as antibodies, cytokines, activated T cells, NK cells that act directly on tumor cells, or those designed to educate or activate (e.g. vaccines) the immune response in the patient [3]. ICD bridges innate and adaptive immunity and therefore can potentiate ICBs and chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy [166]. Anti-CD47 in combination with other therapeutic agents enhanced cell-surface CRT and reduced Treg and MDSCs [167]. STING [162] and TLR [168] agonists have entered early phase clinical testing. The intestinal barrier is a major site of epithelial, immune, and microbiota interactions. The gut microbiota regulates mucosal immunity, colon cancer development, therapeutic responses, and likely influences ICD through tumor and immune interactions including heterogeneity [169,170]. The use of syngeneic models, human-derived models, and ongoing clinical trials will likely help guide the development of biomarkers to facilitate patient-tailored therapy.

6. Conclusions

Emerging evidence supports the establishment of antitumor immunity in the clinical success of antineoplastic agents. Tumor intrinsic mechanisms play a critical role in shaping the immune TME, tumor development and therapeutic responses. Drug-triggered ICD represents a promising approach to restore the immunogenicity in “cold” tumors by engaging both the innate and adaptive components to prime the TME for a greater antitumor response (Figure 1). A better understanding of this process will likely help translate ICD into the clinic. Some critical questions await answers. Cell death, stress response, and immunological outcomes are interconnected and highly cell type- and stimulus-specific. It remains to be determined if and how specific types of cell death, ER stress or other arms of ISR regulate immunogenicity in the context of CRC driver mutations and subtypes. The hallmarks of ICD and immune effectors seem numerous. However, key molecular determinants in the activation of innate immunity upon cell death required to prime adaptive anticancer immunity remain to be elucidated. Lastly, actionable ICD biomarkers will be critical to help guide treatment decisions.

Acknowledgments

We thank members in Zhang and Yu lab for critical reading and apologize to those whose work was not referenced due to space limitation.

Funding: The work in Zhang and Yu lab is currently supported by NIH grants R01CA215481, R01CA203028, R01CA217141, R01 CA236271, R01CA247231, and U19AI068021, and by UPMC HCC startup fund.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional Information:

All authors have reviewed the content in full and agreed on submission.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(1):7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr.,, Kinzler KW . Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finn OJ. Immuno-oncology: understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO 2012;23 Suppl 8:viii6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Cancer-Cell-Intrinsic Mechanisms Shaping the Tumor Immune Landscape. Immunity 2018;48(3):399–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015;348(6230):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 2015;27(4):450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanmamed MF, Chen L. A Paradigm Shift in Cancer Immunotherapy: From Enhancement to Normalization. Cell 2018;175(2):313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nature reviews Immunology 2009;9(5):353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nature reviews Immunology 2017;17(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunological Effects of Conventional Chemotherapy and Targeted Anticancer Agents. Cancer Cell 2015;28(6):690–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018;48(4):812–830 e814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahill DP, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Genetic instability and Darwinian selection in tumours. Trends in cell biology 1999;9(12):M57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Garcia C, Klein AM, Simons BD, Winton DJ. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science 2010;330(6005):822–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 2010;143(1):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anitei MG, Zeitoun G, Mlecnik B et al. Prognostic and predictive values of the immunoscore in patients with rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(7):1891–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 2006;313(5795):1960–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol 2002;3(11):991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagamine CM, Sohn JJ, Rickman BH, Rogers AB, Fox JG, Schauer DB. Helicobacter hepaticus infection promotes colon tumorigenesis in the BALB/c-Rag2(−/−) Apc(Min/+) mouse. Infection and immunity 2008;76(6):2758–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng MW, Galon J, Fridman WH, Smyth MJ. From mice to humans: developments in cancer immunoediting. J Clin Invest 2015;125(9):3338–3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. N Engl J Med 2008;358(25):2704–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018;25(3):486–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strasser A, Cory S, Adams JM. Deciphering the rules of programmed cell death to improve therapy of cancer and other diseases. Embo J 2011;30(18):3667–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leibowitz B, Yu J. Mitochondrial signaling in cell death via the Bcl-2 family. Cancer Biol Ther 2010;9(6):417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, Zhang L. Apoptosis in human cancer cells. Curr Opin Oncol 2004;16(1):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144(5):646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D, Yu J, Zhang L. Necroptosis: an alternative cell death program defending against cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016;1865(2):228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degterev A, Yuan J. Expansion and evolution of cell death programmes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9(5):378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mocarski ES, Upton JW, Kaiser WJ. Viral infection and the evolution of caspase 8-regulated apoptotic and necrotic death pathways. Nature reviews Immunology 2012;12(2):79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15(2):135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature 2011;471(7338):368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green DR, Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Salvesen GS. RIPK-dependent necrosis and its regulation by caspases: a mystery in five acts. Mol Cell 2011;44(1):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun J, Sun Q, Brown MF et al. The Multi-Targeted Kinase Inhibitor Sunitinib Induces Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells via PUMA. PLoS One 2012;7(8):e43158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunther C, Martini E, Wittkopf N et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature 2011;477(7364):335–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welz PS, Wullaert A, Vlantis K et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 2011;477(7364):330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med 2007;13(9):1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tesniere A, Schlemmer F, Boige V et al. Immunogenic death of colon cancer cells treated with oxaliplatin. Oncogene 2010;29(4):482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med 2007;13(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Brockmeier U et al. Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO J 2009;28(5):578–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamura Y, Tsuchikawa T, Miyauchi K et al. The key role of calreticulin in immunomodulation induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20(2):386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol 2011;13(3):184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pawaria S, Binder RJ. CD91-dependent programming of T-helper cell responses following heat shock protein immunization. Nat Commun 2011;2:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2002;418(6894):191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kepp O, Semeraro M, Bravo-San Pedro JM et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation as a biomarker of immunogenic cell death. Semin Cancer Biol 2015;33:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michaud M, Martins I, Sukkurwala AQ et al. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science 2011;334(6062):1573–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 2010;40(2):280–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kronlage M, Song J, Sorokin L et al. Autocrine purinergic receptor signaling is essential for macrophage chemotaxis. Science signaling 2010;3(132):ra55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature 2001;414(6866):916–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stagg J, Beavis PA, Divisekera U et al. CD73-deficient mice are resistant to carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2012;72(9):2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun X, Wu Y, Gao W et al. CD39/ENTPD1 expression by CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promotes hepatic metastatic tumor growth in mice. Gastroenterology 2010;139(3):1030–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nature reviews Immunology 2014;14(1):36–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mesev EV, LeDesma RA, Ploss A. Decoding type I and III interferon signalling during viral infection. Nat Microbiol 2019;4(6):914–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corrales L, McWhirter SM, Dubensky TW Jr.,, Gajewski TF . The host STING pathway at the interface of cancer and immunity. J Clin Invest 2016;126(7):2404–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ning X, Wang Y, Jing M et al. Apoptotic Caspases Suppress Type I Interferon Production via the Cleavage of cGAS, MAVS, and IRF3. Mol Cell 2019;74(1):19–31 e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kepp O, Senovilla L, Vitale I et al. Consensus guidelines for the detection of immunogenic cell death. Oncoimmunology 2014;3(9):e955691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang YJ, Fletcher R, Yu J, Zhang L. Immunogenic effects of chemotherapy-induced tumor cell death. Genes & Diseases 2018;5(3):194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finn OJ, Beatty PL. Cancer immunoprevention. Current opinion in immunology 2016;39:52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fletcher R, Wang YJ, Schoen RE, Finn OJ, Yu J, Zhang L. Colorectal cancer prevention: Immune modulation taking the stage. Biochimica et biophysica acta Reviews on cancer 2018;1869(2):138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lippman SM. The future of molecular-targeted cancer chemoprevention. Gastroenterology 2008;135(6):1834–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ricciardiello L, Ahnen DJ, Lynch PM. Chemoprevention of hereditary colon cancers: time for new strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13(6):352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drew DA, Cao Y, Chan AT. Aspirin and colorectal cancer: the promise of precision chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16(3):173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang L, Yu J, Park BH, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Role of BAX in the apoptotic response to anticancer agents. Science 2000;290(5493):989–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang L, Ren X, Alt E et al. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by targeting APC-deficient cells for apoptosis. Nature 2010;464(7291):1058–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu W, Wang X, Leibowitz B et al. Chemoprevention by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs eliminates oncogenic intestinal stem cells via SMAC-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(46):20027–20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leibowitz B, Qiu W, Buchanan ME et al. BID mediates selective killing of APC-deficient cells in intestinal tumor suppression by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(46):16520–16525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bondurant KL, Lundgreen A, Herrick JS, Kadlubar S, Wolff RK, Slattery ML. Interleukin genes and associations with colon and rectal cancer risk and overall survival. Int J Cancer 2013;132(4):905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Slattery ML, Lundgreen A, Kadlubar SA, Bondurant KL, Wolff RK. JAK/STAT/SOCS-signaling pathway and colon and rectal cancer. Mol Carcinog 2013;52(2):155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Slattery ML, Lundgreen A, Bondurant KL, Wolff RK. Interferon-signaling pathway: associations with colon and rectal cancer risk and subsequent survival. Carcinogenesis 2011;32(11):1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lonnroth C, Andersson M, Arvidsson A et al. Preoperative treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) increases tumor tissue infiltration of seemingly activated immune cells in colorectal cancer. Cancer immunity 2008;8:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bergman M, Djaldetti M, Salman H, Bessler H. Inflammation and colorectal cancer: does aspirin affect the interaction between cancer and immune cells? Inflammation 2011;34(1):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arvind P, Qiao L, Papavassiliou E, Goldin E, Koutsos M, Rigas B. Aspirin and aspirin-like drugs induce HLA-DR expression in HT29 colon cancer cells. Int J Oncol 1996;8(6):1207–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakanishi Y, Nakatsuji M, Seno H et al. COX-2 inhibition alters the phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages from M2 to M1 in ApcMin/+ mouse polyps. Carcinogenesis 2011;32(9):1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalinski P Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. Journal of immunology 2012;188(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H et al. Metformin suppresses colorectal aberrant crypt foci in a short-term clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(9):1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufi S, Vazquez-Martin A et al. Metformin rescues cell surface major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) deficiency caused by oncogenic transformation. Cell Cycle 2012;11(5):865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pereira FV, Melo ACL, Low JS et al. Metformin exerts antitumor activity via induction of multiple death pathways in tumor cells and activation of a protective immune response. Oncotarget 2018;9(40):25808–25825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eikawa S, Nishida M, Mizukami S, Yamazaki C, Nakayama E, Udono H. Immune-mediated antitumor effect by type 2 diabetes drug, metformin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(6):1809–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006;203(5):1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, Hesser J, Demaria S, Formenti SC. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18(5):313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Asna N, Livoff A, Batash R et al. Radiation therapy and immunotherapy-a potential combination in cancer treatment. Curr Oncol 2018;25(5):e454–e460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyerhardt JA, Mayer RJ. Systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;352(5):476–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abrams TA, Meyer G, Schrag D, Meyerhardt JA, Moloney J, Fuchs CS. Chemotherapy usage patterns in a US-wide cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106(2):djt371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Atreya CE, Yaeger R, Chu E. Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: From Current Standards to Future Molecular Targeted Approaches. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2017;37:246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown MF, Leibowitz BJ, Chen D et al. Loss of Caspase-3 sensitizes colon cancer cells to genotoxic stress via RIP1-dependent necrosis. Cell death & disease 2015;6:e1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fessler E, Medema JP. Colorectal Cancer Subtypes: Developmental Origin and Microenvironmental Regulation. Trends in cancer 2016;2(9):505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gou HF, Zhou L, Huang J, Chen XC. Intraperitoneal oxaliplatin administration inhibits the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment in an abdominal implantation model of colon cancer. Mol Med Rep 2018;18(2):2335–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuai R, Yuan W, Son S et al. Elimination of established tumors with nanodisc-based combination chemoimmunotherapy. Sci Adv 2018;4(4):eaao1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lim SH, Chua W, Cheng C et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiation on tumor-infiltrating/associated lymphocytes in locally advanced rectal cancers. Anticancer Res 2014;34(11):6505–6513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381(9863):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El Zouhairi M, Charabaty A, Pishvaian MJ. Molecularly targeted therapy for metastatic colon cancer: proven treatments and promising new agents. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011;4(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang L, Yu J. Role of apoptosis in colon cancer biology, therapy, and prevention. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 2013;9(4):331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manzoni M, Rovati B, Ronzoni M et al. Immunological effects of bevacizumab-based treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncology 2010;79(3–4):187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Botta C, Bestoso E, Apollinari S et al. Immune-modulating effects of the newest cetuximab-based chemoimmunotherapy regimen in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Journal of immunotherapy 2012;35(5):440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Correale P, Botta C, Cusi MG et al. Cetuximab +/− chemotherapy enhances dendritic cell-mediated phagocytosis of colon cancer cells and ignites a highly efficient colon cancer antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell response in vitro. Int J Cancer 2012;130(7):1577–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pozzi C, Cuomo A, Spadoni I et al. The EGFR-specific antibody cetuximab combined with chemotherapy triggers immunogenic cell death. Nat Med 2016;22(6):624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen D, Wei L, Yu J, Zhang L. Regorafenib inhibits colorectal tumor growth through PUMA-mediated apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(13):3472–3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tong J, Wang P, Tan S et al. Mcl-1 Degradation Is Required for Targeted Therapeutics to Eradicate Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Res 2017;77(9):2512–2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arai H, Battaglin F, Wang J et al. Molecular insight of regorafenib treatment for colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2019;81:101912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carnevalli LS, Sinclair C, Taylor MA et al. PI3Kalpha/delta inhibition promotes anti-tumor immunity through direct enhancement of effector CD8(+) T-cell activity. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2018;6(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spisek R, Charalambous A, Mazumder A, Vesole DH, Jagannath S, Dhodapkar MV. Bortezomib enhances dendritic cell (DC)-mediated induction of immunity to human myeloma via exposure of cell surface heat shock protein 90 on dying tumor cells: therapeutic implications. Blood 2007;109(11):4839–4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yu J, Tiwari S, Steiner P, Zhang L. Differential Apoptotic Response to the Proteasome Inhibitor Bortezomib [VELCADE(TM), PS-341] in Bax-Deficient and p21-Deficient Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Biol Ther 2003;2(6):694–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.He K, Chen D, Ruan H et al. BRAFV600E-dependent Mcl-1 stabilization leads to everolimus resistance in colon cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.He K, Zheng X, Li M, Zhang L, Yu J. mTOR inhibitors induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells via CHOP-dependent DR5 induction on 4E-BP1 dephosphorylation. Oncogene 2016;35(2):148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.He K, Zheng X, Zhang L, Yu J. Hsp90 inhibitors promote p53-dependent apoptosis through PUMA and Bax. Mol Cancer Ther 2013:2013 August 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tong J, Tan S, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Yu J, Zou F, Zhang L. FBW7-Dependent Mcl-1 Degradation Mediates the Anticancer Effect of Hsp90 Inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16(9):1979–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wernitznig D, Kiakos K, Del Favero G et al. First-in-class ruthenium anticancer drug (KP1339/IT-139) induces an immunogenic cell death signature in colorectal spheroids in vitro. Metallomics 2019;11(6):1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li X, Li M, Ruan H et al. Co-targeting translation and proteasome rapidly kills colon cancer cells with mutant RAS/RAF via ER stress. Oncotarget 2017;8(6):9280–9292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tan X, Tong J, Wang YJ et al. BET inhibitors potentiate chemotherapy and killing of SPOP-mutant colon cancer cells via induction of DR5. Cancer Res 2019;79(6):1191–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Diederich M Natural compound inducers of immunogenic cell death. Arch Pharm Res 2019;42(7):629–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Siebenkas C, Chiappinelli KB, Guzzetta AA et al. Inhibiting DNA methylation activates cancer testis antigens and expression of the antigen processing and presentation machinery in colon and ovarian cancer cells. PLoS One 2017;12(6):e0179501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee CL, Veeramani S, Molouki A et al. Virotherapy: Current Trends and Future Prospects for Treatment of Colon and Rectal Malignancies. Cancer Invest 2019;37(8):393–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang Q, Ren M, Feng F, Chen K, Ju X. Treatment of colon cancer with liver X receptor agonists induces immunogenic cell death. Mol Carcinog 2018;57(7):903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R et al. DNA-Demethylating Agents Target Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inducing Viral Mimicry by Endogenous Transcripts. Cell 2015;162(5):961–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A et al. Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell 2015;162(5):974–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015;21(11):1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer discovery 2015;5(1):43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kloor M, von Knebel Doeberitz M. The Immune Biology of Microsatellite-Unstable Cancer. Trends in cancer 2016;2(3):121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372(26):2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017;357(6349):409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pino MS, Chung DC. Microsatellite instability in the management of colorectal cancer. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology 2011;5(3):385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16(5):275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Finn OJ. Human Tumor Antigens Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Cancer immunology research 2017;5(5):347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer discovery 2017;7(2):188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Budczies J, Bockmayr M, Klauschen F et al. Mutation patterns in genes encoding interferon signaling and antigen presentation: A pan-cancer survey with implications for the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017;56(8):651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ozcan M, Janikovits J, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Kloor M. Complex pattern of immune evasion in MSI colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 2018;7(7):e1445453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Olson DJ, Luke JJ. The T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment as a paradigm for immunotherapy drug development. Immunotherapy 2019;11(3):155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Trujillo JA, Sweis RF, Bao R, Luke JJ. T Cell-Inflamed versus Non-T Cell-Inflamed Tumors: A Conceptual Framework for Cancer Immunotherapy Drug Development and Combination Therapy Selection. Cancer immunology research 2018;6(9):990–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Grasso CS, Giannakis M, Wells DK et al. Genetic Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer discovery 2018;8(6):730–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. WNT/beta-catenin Pathway Activation Correlates with Immune Exclusion across Human Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(10):3074–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yang W, Li Y, Gao R, Xiu Z, Sun T. MHC class I dysfunction of glioma stem cells escapes from CTL-mediated immune response via activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncogene 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lee YS, Heo W, Son CH, Kang CD, Park YS, Bae J. Upregulation of Myc promotes the evasion of NK cellmediated immunity through suppression of NKG2D ligands in K562 cells. Mol Med Rep 2019;20(4):3301–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Xiao Q, Wu J, Wang WJ et al. DKK2 imparts tumor immunity evasion through beta-catenin-independent suppression of cytotoxic immune-cell activation. Nat Med 2018;24(3):262–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 2012;149(1):22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Palm W, Thompson CB. Nutrient acquisition strategies of mammalian cells. Nature 2017;546(7657):234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science 2016;352(6282):227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Barkal AA, Brewer RE, Markovic M et al. CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 2019;572(7769):392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Feng M, Jiang W, Kim BYS, Zhang CC, Fu YX, Weissman IL. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2019;19(10):568–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Betancur PA, Abraham BJ, Yiu YY et al. A CD47-associated super-enhancer links pro-inflammatory signalling to CD47 upregulation in breast cancer. Nat Commun 2017;8:14802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhang H, Lu H, Xiang L et al. HIF-1 regulates CD47 expression in breast cancer cells to promote evasion of phagocytosis and maintenance of cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(45):E6215–6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109(17):6662–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Schlee M, Holzel M, Bernard S et al. C-myc activation impairs the NF-kappaB and the interferon response: implications for the pathogenesis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Int J Cancer 2007;120(7):1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Knickelbein K, Zhang L. Mutant KRAS as a critical determinant of the therapeutic response of colorectal cancer. Genes & Diseases 2015;2(1):4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Banck MS, Grothey A. Biomarkers of Resistance to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15(24):7492–7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359(17):1757–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(10):1626–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Knickelbein K, Tong J, Chen D et al. Restoring PUMA induction overcomes KRAS-mediated resistance to anti-EGFR antibodies in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 2018;37:4599–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Mao M, Tian F, Mariadason JM et al. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutant colon cancer can be overcome with PI3K inhibition or demethylating agents. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(3):657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liao W, Overman MJ, Boutin AT et al. KRAS-IRF2 Axis Drives Immune Suppression and Immune Therapy Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell 2019;35(4):559–572 e557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kortlever RM, Sodir NM, Wilson CH et al. Myc Cooperates with Ras by Programming Inflammation and Immune Suppression. Cell 2017;171(6):1301–1315 e1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bradley SD, Chen Z, Melendez B et al. BRAFV600E Co-opts a Conserved MHC Class I Internalization Pathway to Diminish Antigen Presentation and CD8+ T-cell Recognition of Melanoma. Cancer immunology research 2015;3(6):602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell 2009;137(3):413–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Begus-Nahrmann Y, Lechel A, Obenauf AC et al. p53 deletion impairs clearance of chromosomal-instable stem cells in aging telomere-dysfunctional mice. Nat Genet 2009;41(10):1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tong J, Tan S, Zou F, Yu J, Zhang L. FBW7 mutations mediate resistance of colorectal cancer to targeted therapies by blocking Mcl-1 degradation. Oncogene 2017;36(6):787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tong J, Zheng X, Tan X et al. Mcl-1 Phosphorylation without Degradation Mediates Sensitivity to HDAC Inhibitors by Liberating BH3-Only Proteins. Cancer Res 2018;78(16):4704–4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chen D, Tong J, Yang L et al. PUMA amplifies necroptosis signaling by activating cytosolic DNA sensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(15):3930–3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature 1997;386(6625):623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Fodde R, Kuipers J, Rosenberg C et al. Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3(4):433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Lee JJ, Chu E. Recent Advances in the Clinical Development of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy for Mismatch Repair Proficient (pMMR)/non-MSI-H Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clinical colorectal cancer 2018;17(4):258–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bakhoum SF, Cantley LC. The Multifaceted Role of Chromosomal Instability in Cancer and Its Microenvironment. Cell 2018;174(6):1347–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Salaun B, Zitvogel L, Asselin-Paturel C et al. TLR3 as a biomarker for the therapeutic efficacy of double-stranded RNA in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2011;71(5):1607–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Sistigu A, Yamazaki T, Vacchelli E et al. Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 2014;20(11):1301–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Flood BA, Higgs EF, Li S, Luke JJ, Gajewski TF. STING pathway agonism as a cancer therapeutic. Immunol Rev 2019;290(1):24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Konno H, Yamauchi S, Berglund A, Putney RM, Mule JJ, Barber GN. Suppression of STING signaling through epigenetic silencing and missense mutation impedes DNA damage mediated cytokine production. Oncogene 2018;37(15):2037–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Katlinski KV, Gui J, Katlinskaya YV et al. Inactivation of Interferon Receptor Promotes the Establishment of Immune Privileged Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2017;31(2):194–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Sasidharan Nair V, Toor SM, Taha RZ, Shaath H, Elkord E. DNA methylation and repressive histones in the promoters of PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT, PD-L1, and galectin-9 genes in human colorectal cancer. Clin Epigenetics 2018;10(1):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Newick K, O’Brien S, Moon E, Albelda SM. CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Annual review of medicine 2017;68:139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gholamin S, Mitra SS, Feroze AH et al. Disrupting the CD47-SIRPalpha anti-phagocytic axis by a humanized anti-CD47 antibody is an efficacious treatment for malignant pediatric brain tumors. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(381). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Urban-Wojciuk Z, Khan MM, Oyler BL et al. The Role of TLRs in Anti-cancer Immunity and Tumor Rejection. Front Immunol 2019;10:2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Gopalakrishnan V, Helmink BA, Spencer CN, Reuben A, Wargo JA. The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Cancer, Immunity, and Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2018;33(4):570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Turajlic S, Sottoriva A, Graham T, Swanton C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2019;20(7):404–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]