Abstract

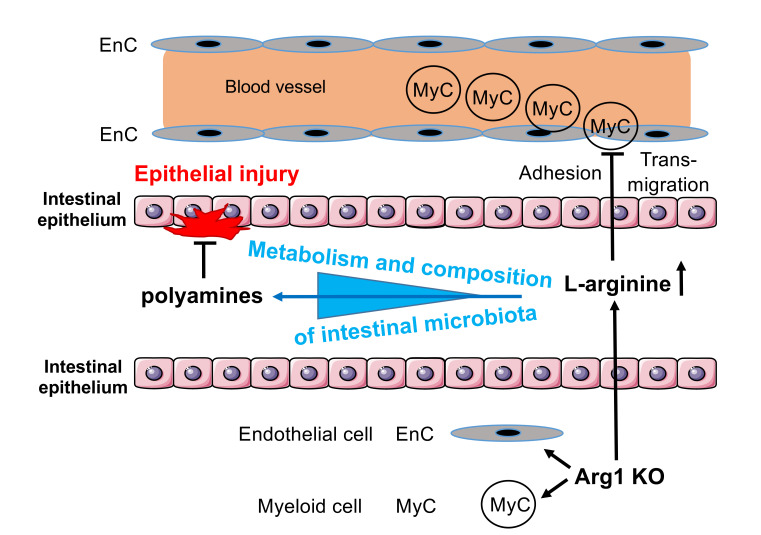

Arginase 1 (Arg1), which converts l-arginine into ornithine and urea, exerts pleiotropic immunoregulatory effects. However, the function of Arg1 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains poorly characterized. Here, we found that Arg1 expression correlated with the degree of inflammation in intestinal tissues from IBD patients. In mice, Arg1 was upregulated in an IL-4/IL-13– and intestinal microbiota–dependent manner. Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice lacking Arg1 in hematopoietic and endothelial cells recovered faster from colitis than Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) littermates. This correlated with decreased vessel density, compositional changes in intestinal microbiota, diminished infiltration by myeloid cells, and an accumulation of intraluminal polyamines that promote epithelial healing. The proresolving effect of Arg1 deletion was reduced by an l-arginine–free diet, but rescued by simultaneous deletion of other l-arginine–metabolizing enzymes, such as Arg2 or Nos2, demonstrating that protection from colitis requires l-arginine. Fecal microbiota transfers from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice into WT recipients ameliorated intestinal inflammation, while transfers from WT littermates into Arg1-deficient mice prevented an advanced recovery from colitis. Thus, an increased availability of l-arginine as well as altered intestinal microbiota and metabolic products accounts for the accelerated resolution from colitis in the absence of Arg1. Consequently, l-arginine metabolism may serve as a target for clinical intervention in IBD patients.

Keywords: Gastroenterology, Immunology

Keywords: Cellular immune response, Polyamines

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are characterized by an immune-mediated inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Both inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are thought to result from dysregulated interactions of the commensal microbiota, the intestinal epithelium (IE), and the mucosal humoral and cellular immune network (1). Genetic, geographic, microbial, and habitual factors contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD (2). As biologic agents targeting these complex interactions induce remission in not more than 50% of the patients (3–5), novel therapeutic approaches are urgently required. The intestinal microbiota plays a critical role in the development of IBD, as it influences the nutrient metabolism and immune responses of the host. Fecal microbiota transfers (FMTs) are currently discussed as treatment for IBD (6–8).

One promising medical target is the semiessential amino acid l-arginine, a central intestinal metabolite, which is converted by the isoenzymes arginase 1 (Arg1) and Arg2 into ornithine and urea. Mitochondrial Arg2 is widely distributed in extrahepatic tissues (9). Although Arg2 is predominantly constitutively expressed, bacterial LPS, for example, has been shown to upregulate Arg2 expression in myeloid cells (10, 11). The cytoplasmic Arg1 is efficiently induced by microbial compounds, hypoxia, and Th2 cytokines in myeloid, endothelial, and epithelial cells (12–15). Constitutive expression of Arg1 is found in hepatocytes (16), innate lymphoid 2 cells (ILC2s) (17, 18), and rat and human fibroblasts (19–22). Numerous studies have reported an involvement of Arg1 in immune cell (dys)function. For example, Arg1 can either promote or inhibit T cell proliferation, which results from an increased availability of polyamines and impaired nitric oxide (NO) production or from depletion of l-arginine as a building block for the synthesis of multiple metabolites and proteins, respectively (23). Ornithine, one of the metabolic products of Arg1, serves as precursor for the synthesis of polyamines and proline, which are involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and collagen synthesis, respectively. Thus, organ fibrosis, tissue repair, and wound healing are regarded as classical examples of Arg1-dependent processes (24, 25).

Polyamines are synthesized not only by mammalian cells, but also by microorganisms. Bacteria synthesize polyamines from l-arginine as well as from l-lysine, l-ornithine, and l-aspartic acid (26). Bacteria in the gut represent an important source of polyamines (27). Furthermore, several microbes use the l-arginine pool of the host for their own survival and/or the expression of various pathogenicity genes (28, 29). The consequences of an Arg1 deficiency of the host for the intraluminal polyamine pool and/or the composition of the intestinal microbiota have not yet been studied.

Type 2 nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) is typically induced in myeloid and endothelial cells by type 1 T helper cell cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF). It catalyzes the formation of citrulline and NO and shares with Arg1 the substrate l-arginine. NO exerts potent antimicrobial and immunoregulatory activities and stimulates mucosal blood flow and mucus generation. Nitrite and nitrate represent oxidative end products of endogenous NO metabolism that, however, can become NOS2-independent sources of NO (30, 31). The utilization of nitrate from dietary or endogenous sources by mammalian organisms requires its initial reduction to nitrite by intestinal microbiota (32, 33), as mammals lack specific and effective nitrate reductases. Various bacteria even gain a survival advantage due to their ability to use nitrate and nitrite as energy sources under anaerobic conditions (so-called nitrate respiration or dissimilation) (34, 35).

Several studies revealed an enhanced expression and activity of Arg1 in the intestinal (sub)mucosa of patients with IBD (36–38) and upon application of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) in the colon of mice (39). Furthermore, l-arginine metabolism is altered in IBD patients (40). Initial studies with Arg1 inhibitors led to conflicting results in murine colitis models (39, 41). These results have to be interpreted with caution, as Arg inhibitors are not isoform selective, affect the hepatic urea cycle, and might even serve, as described for Nω-hydroxy-l-arginine (NOHA), as substrates of NOS2. Furthermore, neither their optimal dose nor exact tissue distributions have been established. Reliable functional analyses of Arg1 in the immune system have only become possible with the generation of conditional Arg1fl/fl mice (14). However, both the cellular source and the cell-specific function of Arg1 in the gut have remained undefined to date. Furthermore, the antagonistic regulation of Arg1 and NOS2 and its impact on the intestinal microbiota has not yet been explored.

Here, we observed that Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, which do not express Arg1 in hematopoietic and endothelial cells, unexpectedly developed a less severe DSS- or oxazolone-induced colitis than littermate controls. The accelerated resolution of pathology was associated with compositional changes in the intestinal microbiota, intraluminal polyamine accumulation, and altered permissiveness of the host to inflammatory microbial compounds. FMTs from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors into broad-spectrum antibiotic–treated WT recipients restored the protective, antiinflammatory phenotype, suggesting that altered host-microbiota interactions in the absence of Arg1 decrease the susceptibility of mice to experimentally induced intestinal damage.

Results

Arg1 expression correlates with the degree of inflammation in tissue biopsies of IBD patients.

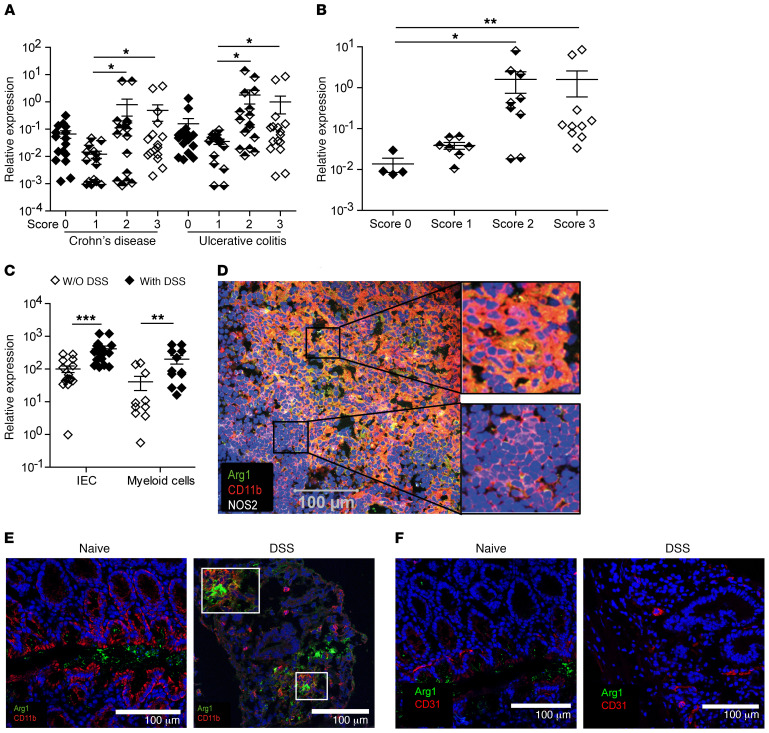

To address a potential correlation between the expression of Arg1 and the severity of inflammation in IBD, we screened intestinal tissue biopsies from CD and UC patients that were graded from 0 to 3 depending on the degree of inflammation for Arg1 mRNA copy numbers using quantitative PCR (qPCR). Indeed, in tissue biopsies from various segments of the gut of both IBD patient cohorts as well as in biopsies from the sigmoid colon of UC patients, a higher inflammatory score correlated with up to 20 times higher Arg1 mRNA levels (Figure 1, A and B), implying a prominent role of Arg1 in the pathogenesis of IBD. Therefore, we investigated the impact of Arg1 on the resolution of intestinal inflammation in different experimental colitis models.

Figure 1. Expression of Arg1 in human IBD and mouse DSS-induced colitis.

(A–C) Using qPCR, Arg1 expression was evaluated in intestinal tissue biopsies from CD and UC patients (A), sigmoid tissue biopsies from UC patients (B), or in IECs or myeloid cells purified from WT mice before and after DSS application (C). The ratio of Arg1 mRNA copies relative to Hprt copies was calculated in the indicated cells and tissues of 14–16 CD and UC patients (A), 4–10 UC patients (B) for each score and 10–16 individual female mice (C). The relative increase in Arg1 copy numbers in tissues of patients for each score and of naive versus DSS-treated WT mice is displayed. Depending on the number of groups and the distribution of data, data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons if the former was significant, or for multiple comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used if the former was significant. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean. (D–F) Using confocal laser microscopy, Arg1 expression was determined in mLNs (D) and in total colonic tissue of naive and DSS-treated SPF B6 mice (E and F). Serial sections from mLNs (D) or colonic lesions (E and F) were stained for Arg1 (green), NOS2 (white), CD11b (red), or CD31 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 100 μm. Original magnification, ×100.

Arg1 in the intestine is regulated in a cell-specific manner.

Under physiological conditions, the intestine is characterized by a hypoxic microenvironment (42) that on its own is sufficient to cause upregulation of Arg1 (43). To identify Arg1+ cell types in naive and colitic mice, we studied the distribution of Arg1 in intestinal tissues before and after application of DSS. We also analyzed the expression of Arg1 in different cell populations in vitro following exposure to various bacteria and oxygen concentrations.

Constitutive expression of Arg1 mRNA was detectable in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC), myeloid cells, and ILC2s from naive mice (Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI126923DS1). Following DSS treatment, upregulation of Arg1 mRNA was readily seen in the lamina propria (LP), myeloid cells, and IECs, but not in unseparated IE or in purified ILC2s (Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). Arg1-expressing cells in mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs) and colonic tissues were predominantly positive for CD11b after DSS application, as shown by using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy (CLSFM), whereas no coexpression was detected in naive mice (Figure 1, D–F). A comparable upregulation of Arg1 in intestinal tissues was also observed after the application of oxazolone (Supplemental Figure 2A). Although Arg1+ cells in the colon of DSS-treated mice hardly coexpressed CD31, we observed an expression of Arg1 by murine endothelial cells in response to E. coli under hypoxic conditions in vitro (Supplemental Figure 1C), suggesting that endothelial cells form an additional source of Arg1. This has also been previously observed with human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells after exposure to LPS/TNF (38).

Arg1 expression in intestinal tissues requires intestinal microbiota and IL-4/IL-13.

To assess the influence of gut microbiota on Arg1 expression, we obtained organs and cells from germ-free (GF) mice, specific pathogen–free (SPF) mice, or SPF mice treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. We observed a 10-fold reduction of Arg1 mRNA in the colon of naive GF mice compared with SPF mice. A similar significant reduction of Arg1 was observed in cells purified from the LP of GF mice (Figure 2A). The colonic tissue of SPF mice that were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics also contained significantly lower Arg1 mRNA copy numbers compared with that of untreated SPF controls before and after DSS application (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Intestinal microbiota and IL-4/IL-13 promote Arg1 expression.

(A–C) Using qPCR, Arg1 expression was assessed in total colonic tissue, unseparated LP, IE, and mLNs of naive GF, SPF (with or without application of broad spectrum antibiotics) (A and B), or Il4/Il13–/– mice, and respective WT controls (C). The ratio of Arg1 mRNA copies relative to Hprt copies was calculated in 4–14 individual female mice. The relative increase in Arg1 copy numbers in tissues of naive versus DSS-treated WT mice is displayed. Depending on the number of groups and the distribution of data, data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons if the former was significant, or for multiple comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used if the former was significant. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

IL-4 and IL-13 are among the cytokines that are induced upon DSS application (44) and are regulated by commensal bacteria (45). Both cytokines promote DSS-mediated intestinal damage (46, 47). Here, they were found to be critical for the induction of Arg1, as documented by the strongly decreased Arg1 expression in Il4/Il13–/– mice compared with WT littermates (Figure 2C). Both cytokines and the intestinal microbiota also perpetuated the expression of Arg1 in the colon following application of oxazolone (Supplemental Figure 2, B and C). Together, these data argue for a cell type–specific regulation of Arg1 expression in the intestine that is modulated by oxygen tension, microbiota, and inflammation.

Mice with a deletion of Arg1 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells develop milder colitis than WT littermates.

l-arginine catabolism by Arg1 can cause suppression of immune responses (48). Since Arg1 is expressed in myeloid, epithelial, and endothelial cells as well as in ILC2s (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1), we crossed Arg1fl/fl mice to the respective cell type–specific Cre deleter mice and evaluated the impact of conditional Arg1 deletions on DSS-induced colitis. None of the generated mouse strains exhibited spontaneous pathology, signs of colitis, or weight loss. Upon DSS application, Villin-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, which lack the expression of Arg1 in IECs, had no clinical phenotype (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B). Importantly, the deletion of Arg1 in IECs led to an enhanced expression of Arg1, Arg2, and Nos2 upon DSS application in CD11b+ myeloid cells purified from the LP (Supplemental Figure 3C). In contrast, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, which are deficient for Arg1 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells, did not exhibit any significant alterations in the expression of Arg1 or Nos2 in IECs (Supplemental Figure 3D). Following DSS application, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice lost weight regardless of their sex and the number of DSS cycles to a degree similar to that of Arg1-expressing litters (Arg1fl/fl) (Supplemental Figure 4, A–C), except for in 1 out of 6 experiments, in which the weight loss in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice was significantly smaller than in the control group (Supplemental Figure 4A). Importantly, however, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice exhibited significantly reduced colitis compared with Arg1-expressing littermates and recovered faster from DSS-induced tissue damage (Figure 3, A–H), suggesting an unexpected colitogenic role of Arg1. The improved recovery from DSS-induced damage was most prominent after 1 cycle of DSS (data not shown). Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice also developed less severe wasting disease and colitis than WT litters upon application of oxazolone (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 3. The deletion of Arg1 within the endothelial and hematopoietic cell compartment ameliorates colitis.

(A–G) The severity of colitis in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and in the respective littermate controls was monitored by high-resolution endoscopy (A–D) and histopathological analyses of H&E-stained tissue sections (E–H) on days 10 (A, B, E, and F) and 15 (C, D, G, H). Representative images from colonoscopies (A and C) and H&E-stained tissue sections (E and G) as well as the means (± SD) of the endoscopic and histological scores from 11–13 (B and F) and 6–7 (D and H) individual knockout female mice and littermate WT controls (Arg1fl/fl) are displayed. Scale bars: 200 μm (E); 100 μm (G). Depending on the number of groups and the distribution of data, data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons if the former was significant, or for multiple comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used if the former was significant. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

To further dissect the contribution of the myeloid, ILC2, and endothelial cell compartment to this unexpected phenotype, we analyzed Cx3cr1-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Il13-Cre Arg1fl/fl, and Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, respectively. Neither Cx3cr1-Cre Arg1fl/fl nor Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl or Il13-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice showed a significant reduction in the severity of DSS-induced colitis, as seen in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Supplemental Figure 3, E–G). However, irradiated Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice reconstituted with bone marrow from Cx3cr1-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors developed a milder colitis compared with Arg1-expressing controls (Supplemental Figure 3H), which resembled the results obtained with Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 3, A–H). Thus, the deletion of Arg1 within the myeloid and endothelial cell compartment is required and sufficient to confer protection. In accordance with these findings, transfer of T cells from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl or WT littermate (Arg1fl/fl) donors induced a similarly severe disease in Rag1–/– recipients, whereas T cell transfer colitis was significantly less severe in Rag1–/– × Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl recipients (Supplemental Figure 6). These data suggest that the combined expression of Arg1 by myeloid and endothelial cells counteracts the resolution of inflammation in 3 different models of experimental colitis.

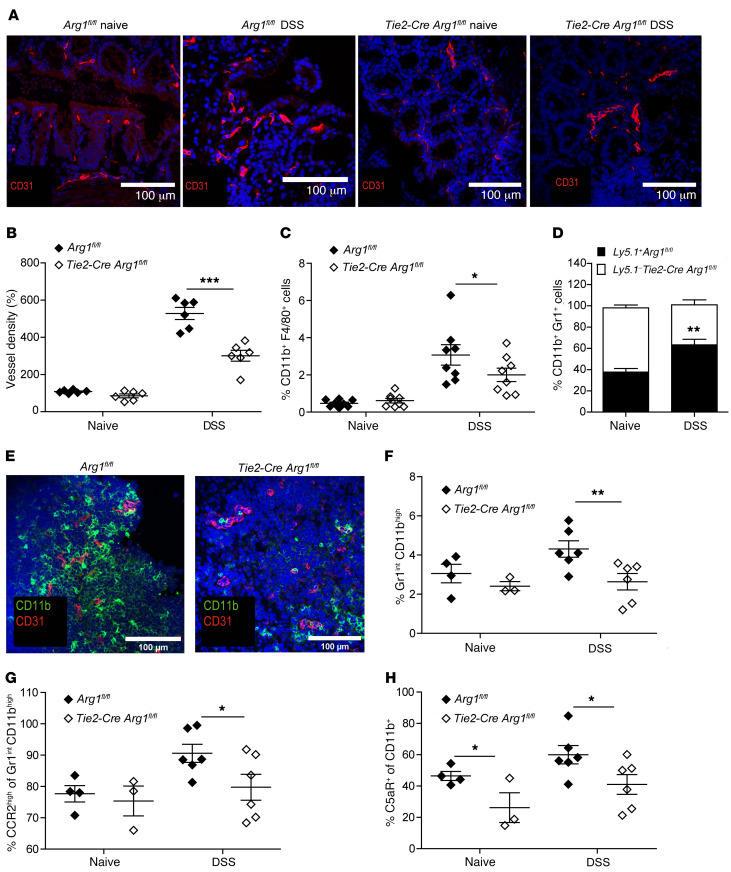

Arg1 deficiency decreases vessel density and myeloid cell adhesion.

As enhanced Arg1 expression and activity in microvessels and submucosal tissues of IBD patients had been associated with endothelial pathobiology and more severe disease (38), we evaluated the content, architecture, and density of intestinal blood vessels in naive and DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermate (Arg1fl/fl) controls. While the vascular architecture appeared to be similar in naive mice of both genotypes, the vessel density was decreased in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice compared with Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) upon DSS application (Figure 4, A and B, and Supplemental Video 1). As Arg1 expression has been linked to enhanced cellular adhesion and transmigration by virtue of suppression of NO production (38, 49, 50), we analyzed, before and after DSS application, the distribution of immune cell subsets in the LP and their chemokine, integrin, and adhesion molecule expression patterns in the blood, draining the GI tract of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and respective WT controls (Arg1fl/fl). We detected a higher percentage of F4/80+CD11b+ and Gr1+CD11b+ cells in the LP of Arg1-competent (Arg1fl/fl) mice (Figure 4, C and D, and Supplemental Figure 7, A, B, and D–G) and found more CD11b+ cells accumulating around CD31+ endothelial cells in these animals compared with Arg1-deficient littermates (Figure 4E). Furthermore, a significantly larger proportion of CD11bhiGr1int myeloid cells (Figure 4F and Supplemental Figure 7, A and C) with a higher expression of CCR2 (Figure 4G and Supplemental Figure 7, H–J) and C5aR (Figure 4H and Supplemental Figure 7K) were recovered from the gut-draining vessels of these animals compared with Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice. In contrast, the expression of CCR5, LFA-1, and α4β7 did not differ significantly between the 2 mouse strains (data not shown). Together with previous observations on an improved course of colitis after blocking CCR2 or C5aR (51–57), these data suggest that the expression of Arg1 by endothelial and myeloid cells promotes vascular adhesion and transmigration of myeloid cells responsive to chemoattractants, thereby entertaining colonic inflammation.

Figure 4. Arg1 increases vessel density and enhances myeloid cell adhesion.

(A and B) Colonic tissue sections of naive or DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) were stained for CD31 (red) and DAPI (blue) (A), and the relative blood vessel density was quantified in 6 individual mice each (B). Scale bars: 100 μm. (C and D) Distribution of the indicated cell subsets was assessed in the LP by flow cytometry; displayed data represent the results of 8 individually analyzed Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermate controls (Arg1fl/fl) (C) as well as 6 individually assessed mixed Ly5.1+/Ly5.1– Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl/WT (Arg1fl/fl) bone marrow chimeric mice (D). (E) Colonic tissue sections of DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) were stained for CD31 (red) and CD11b (green). Scale bars: 100 μm. (F–H) Surface phenotype of myeloid cells harvested from blood vessels draining intestinal tissues of 3–6 individually analyzed Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and respective littermate controls (Arg1fl/fl) was assessed by flow cytometry 12 hours after DSS application (F) along with CCR2 (G) and C5aR expression (H). Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

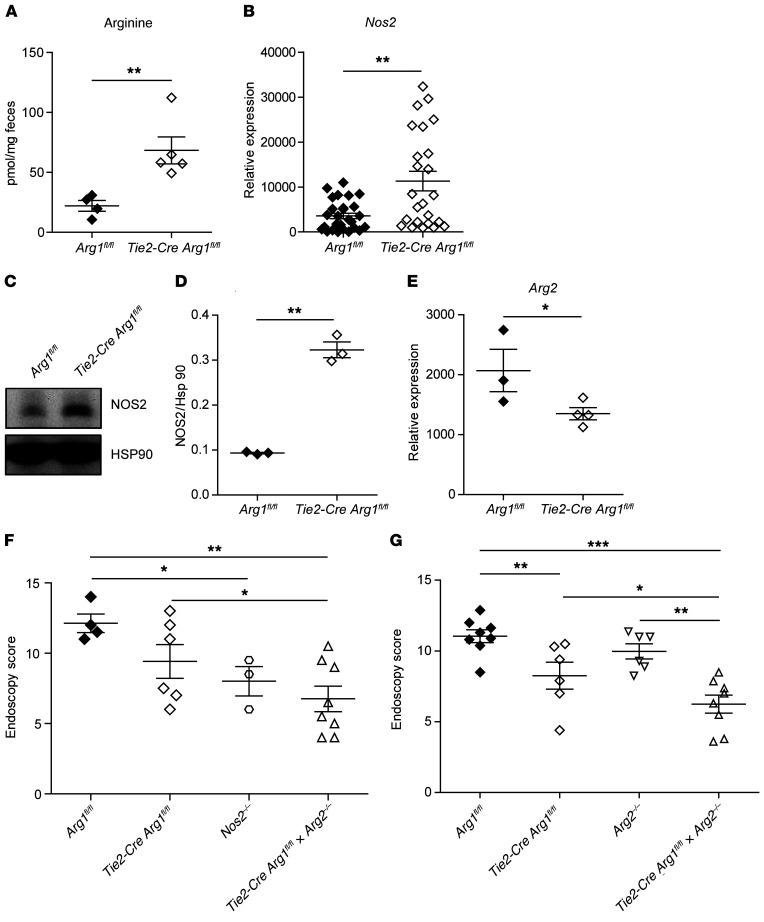

An additional deletion of Arg2 or Nos2 in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice further ameliorates colitis.

To further examine l-arginine metabolism in colonic tissues of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and littermate (Arg1fl/fl) controls, we assessed the accumulation of l-arginine in the feces. In addition, we analyzed the expression of (a) argininosuccinate lyase (Asl) and argininosuccinate synthase (Ass), the 2 enzymes required for the regeneration of l-arginine from l-citrulline; (b) ornithine carbamoyltransferase (Otc), which transfers carbamoyl phosphate to ornithine and thereby generates citrulline; and (c) the inducible transporter Slc7a2, required for the uptake of l-arginine from the intestinal lumen (Supplemental Figure 8). Significantly more l-arginine was recovered from the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice than from WT (Arg1fl/fl) litters (Figure 5A). There were no differences in the expression of Slc7a2 (data not shown), Otc, and Ass (Supplemental Figure 9, A and B) between WT (Arg1fl/fl) and Arg1-deficient mice. However, gene expression of Asl was increased in Arg1-expressing control (Arg1fl/fl) mice compared with Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Supplemental Figure 9C), potentially reflecting a compensatory mechanism to counterbalance the enhanced consumption of l-arginine by Arg1.

Figure 5. The additional deletion of Arg2 or Nos2 in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice further ameliorates colitis.

(A) The concentration of l-arginine was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in the feces of DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and WT control litters. (B–E) The expression of NOS2 (B–D) and Arg2 (E) were assessed by qPCR (B), Western blotting (C and D), and RNA-Seq (E) in colonic tissues (B and E) and mLNs (C and D) of 4 to 24 DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and 3–28 Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl). The ratio of the mRNA copies of the indicated genes relative to the Hprt copies was calculated (B), and the relative increase in the respective gene copy numbers is displayed. Western blot signals from 3 experiments containing 2 to 3 mice per group in each cohort were quantitated using ImageJ software (D). (F and G) Severity of colitis in the indicated mouse strains was monitored by endoscopy (n = 3–8). Depending on the number of groups and the distribution of data, data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons if the former was significant, or for multiple comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used if the former was significant. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

Arg1 competes with NOS2 for l-arginine, which is also metabolized by arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (Agat), arginine decarboxylase (Adc), and Arg2 (16). While Adc mRNA remained undetectable, there were no differences in gene expression of Agat and guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (Gamt) in colonic tissue as well as in the fecal accumulation of creatine, the final product of both enzymatic reactions (Supplemental Figure 9, D–F). The expression of agmatinase (Agmat) (the enzyme that cleaves agmatin, the metabolic product of Adc) also did not differ between the 2 mouse strains (Supplemental Figure 9G). In addition, the expression of the ornithine aminotransferase (Oat) and the accumulation of its metabolic product (proline) in the feces were comparable between Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and littermate controls (Supplemental Figure 9, H and I). The expression of NOS2, in contrast, was slightly enhanced in colonic tissues (Figure 5B) and mLNs (Figure 5, C and D) of DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice compared with WT littermates (Arg1fl/fl), while the expression of Arg2 was decreased (Figure 5E).

As the functional role of NOS2 and Arg2 in the pathogenesis of colitis is a matter of ongoing debate (58), we directly assessed the impact of NOS2 and Arg2 on the clinical phenotype by (a) applying the NOS2 inhibitor L-NIL to Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) and by (b) crossing Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) with Nos2–/– or Arg2–/– mice. Both experimental strategies failed to reverse the phenotype observed in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice; in fact, colitis was even further ameliorated when Nos2 or Arg2 was additionally depleted (Figure 5, F and G, Supplemental Figure 9J). Together, these results give strong support to the concept that protection in our model correlates with an increased availability of l-arginine.

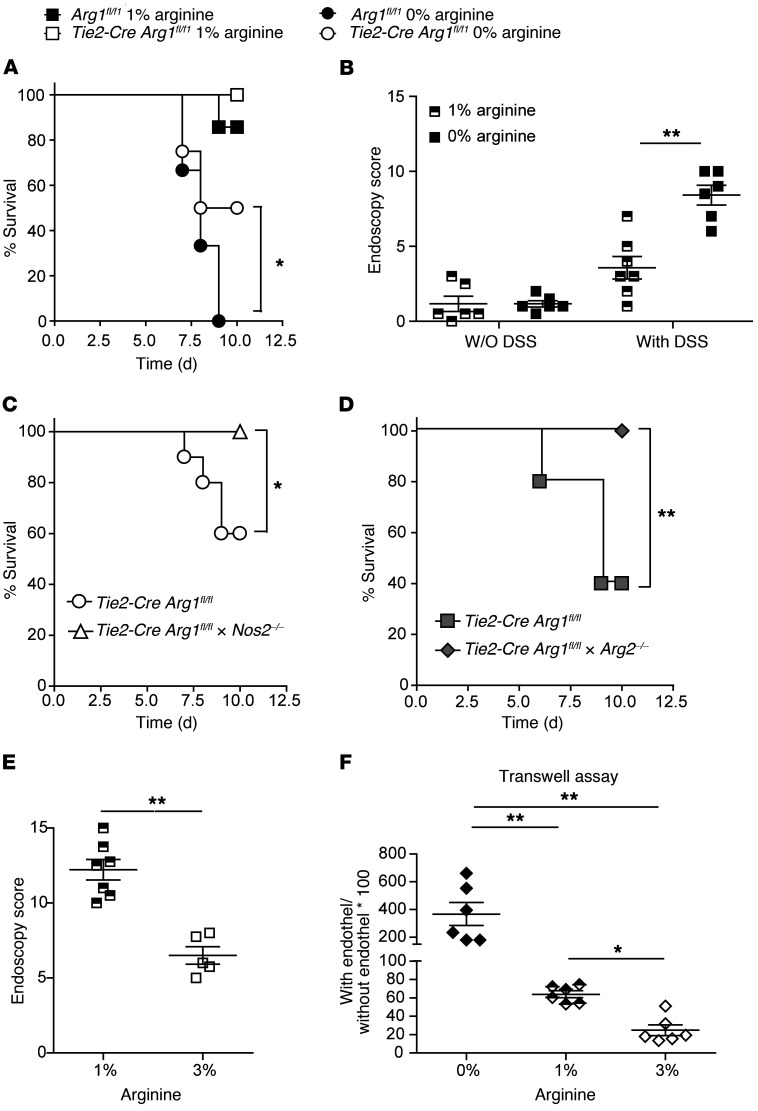

Enzymatic consumption of l-arginine promotes colitis.

Recently, oral l-arginine supplementation of DSS-treated mice was found to improve the course of colitis (59, 60) and to enhance intraluminal and systemic polyamine concentrations (61). Here, we tested to determine whether dietary l-arginine restriction reversed the improved outcome of DSS-induced colitis in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice. Indeed, dietary restriction of l-arginine induced progressive weight loss, Il17 production, and fatal wasting disease in DSS-treated animals (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 10A). Interestingly, the effect was more prominent in WT (Arg1fl/fl) than in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice. The surviving Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice lost weight more quickly and developed more severe colitis under l-arginine restriction than mice on a control diet (Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure 10, B and C). In contrast, untreated control mice neither lost weight nor developed signs of colitis, suggesting that the protective effect of Arg1 deletion depends on the increased availability of l-arginine following DSS application. None or only few animals of these mouse strains succumbed to wasting disease under control chow (Figure 6A), further supporting the concept that protection in our model is conferred by the availability of l-arginine. In addition, under dietary l-arginine restriction, wasting disease was delayed in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/f × Nos2–/– and Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl × Arg2–/– mice compared with Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, respectively (Figure 6, C and D). As previously observed (59, 60), l-arginine supplementation improved colitis in WT mice (Figure 6E). In line with the improved endothelial integrity (Figure 4), enhanced availability of l-arginine (Figure 5A) in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice in vivo, and reversion of endothelial dysfunction by l-arginine in patients (62–64), supplementation with l-arginine inhibited the transmigration of myeloid cells in vitro, whereas depletion of l-arginine enhanced endothelial permeability (Figure 6F). In the oxazolone model of colitis, l-arginine supplementation similarly improved survival and ameliorated inflammation in the large intestine, while dietary restriction of l-arginine induced progressive weight loss and fatal wasting disease (Supplemental Figure 11).

Figure 6. Arg1-dependent depletion or nutritional restriction of l-arginine exacerbates colitis and endothelial permeability.

(A, C, and D) The survival curves for 12–14 (A), 10 (C), and 8–15 (D) individual mice of the indicated mouse strains are displayed. Data shown in panels C and D is for mice on an l-arginine–free chow. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for each cohort, and statistical significance was determined by log-rank test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01. (B and E) The severity of colitis in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice fed with control or l-arginine–free chow (B) as well as in WT mice fed control (1% l-arginine) or l-arginine–enriched chow (3% l-arginine) (E) was monitored by endoscopy. The means (± SD) of the endoscopic scores from 5–7 individual knockout female mice in each cohort are displayed. (F) Macrophage transmigration across an endothelial layer in the presence of the indicated l-arginine concentrations was measured with Transwell chambers (n = 6). Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed with Dunn’s multiple comparisons if the former was significant. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

Polyamines accumulate in the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice.

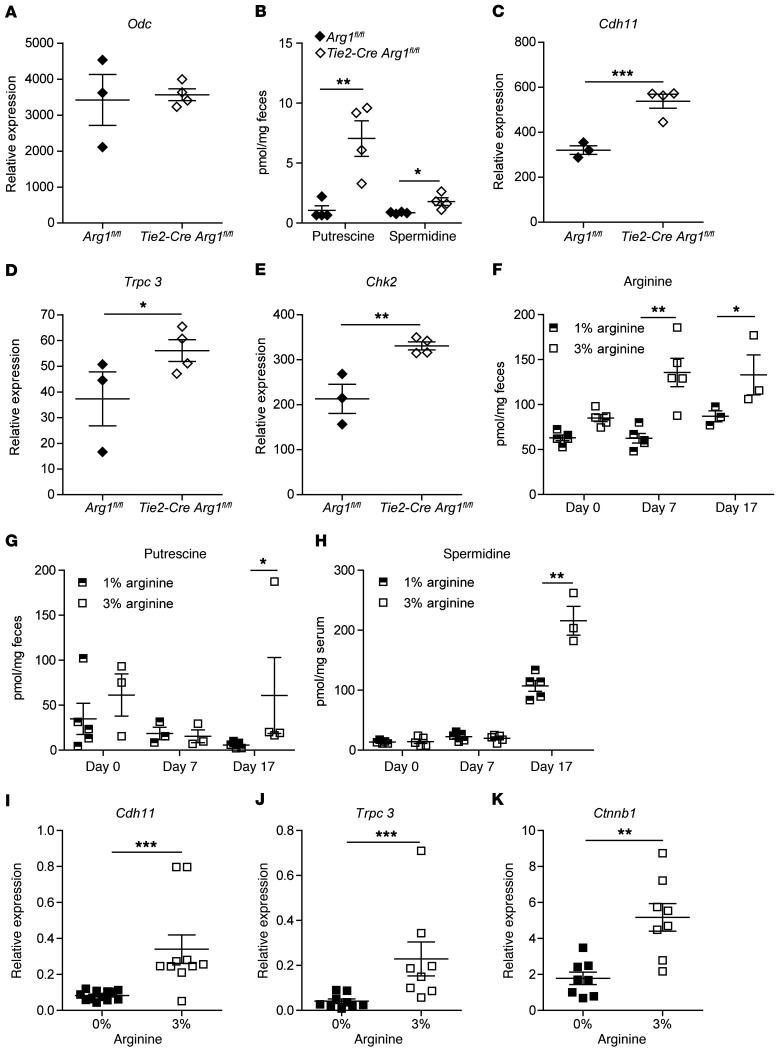

Arg1 generates ornithine and thereby forms the starting point for the synthesis of polyamines (Supplemental Figure 8). As the activity of ornithine decarboxylase (Odc), the rate-limiting enzyme of polyamine synthesis, is solely regulated by changes in the amount of ODC protein rather than by modifications of its catalytic activity (65), we assessed the expression of Odc in vitro and in vivo. Unstimulated Arg1-deficient bone marrow–derived DCs showed reduced Odc expression compared with WT (Arg1fl/fl) controls (Supplemental Figure 12A). Addition of E. coli enhanced Odc expression in Arg1-expressing DCs, but not in Arg1-deficient DCs. As a result, significantly more putrescine accumulated in cultures of Arg1-expressing DCs (Supplemental Figure 12B). In contrast, we did not detect significantly different regulation of Odc or other enzymes involved in the synthesis or degradation of polyamines in intestinal tissues of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice compared with littermate controls (Figure 7A and Supplemental Figure 13). Based on these observations, it was unexpected that the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice still contained higher amounts of putrescine and spermidine than the feces of littermate controls (Arg1fl/fl) (Figure 7B), which raised the possibility that intestinal microbiota contribute to the intraluminal polyamine metabolism.

Figure 7. Improved recovery from colitis in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice is associated with fecal accumulation of polyamines and the expression of polyamine target genes in colonic tissues.

(A) Expression of Odc was analyzed by RNA-Seq in colonic tissues. (B) Concentrations of polyamines were determined by HPLC in the feces. (C–E) Expression of Cdh11 (C), short Trpc3 (D), and Chk2 (E) were evaluated by RNA-Seq in colonic tissues. (F–H) Concentrations of l-arginine (F) and polyamines (G and H) were determined by HPLC in the feces (F and G) and serum (H) before l-arginine supplementation (day 0) or DSS application (day 7) and at the end of the experiment (day 17), as also depicted in the schematic of Supplemental Figure 18J. (n = 3–5). (I–K) Expression of Cdh11 (I), short Trpc3 (J), and Ctnnb1 (K) were assessed by qPCR in colonic tissues of 8–10 individual mice. Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) were fed control chow (A–H), l-arginine–free chow (I–K), or chow supplemented with 3% l-arginine (F–K). The ratio of the mRNA copies of the indicated genes relative to the Hprt copies was calculated (I–K), and the relative increase in the respective gene copy numbers comparing Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and littermate controls (Arg1fl/fl) in each cohort is displayed. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

There exists a strong relationship among polyamines, mucosal repair processes, and epithelial barrier function (66). Measuring the expression of several polyamine target genes in the gut, we found enhanced expression of various cadherins and protocadherins and of the transient receptor potential channel 3 (Trcp3) in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 7, C and D, and Supplemental Figure 14), all of which are critical for cell migration to sites of tissue injury (66). In addition, the expression of checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2), a serine-threonine kinase that regulates occludin mRNA translation and thus the maintenance and reestablishment of gut barrier integrity (66), was significantly higher in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 7E). These data support the concept that the accumulation of polyamines contributes to the resolution of colitis due to an enhanced repair of epithelial cell injury.

To determine whether the availability of l-arginine affects intraluminal polyamine concentrations, we analyzed mice fed normal chow (containing 1% l-arginine), l-arginine–free chow, or chow containing 3% l-arginine. We found that polyamines accumulated in the feces and in the serum upon dietary l-arginine supplementation (Figure 7, F–H), which was similar to the previously reported increase of polyamines in inflamed colon (41). In accordance with these observations, the expression of polyamine target genes in intestinal tissues of the host directly correlated with the availability of l-arginine (Figures 7, I–K).

l-arginine supplementation attenuates intestinal dysbiosis.

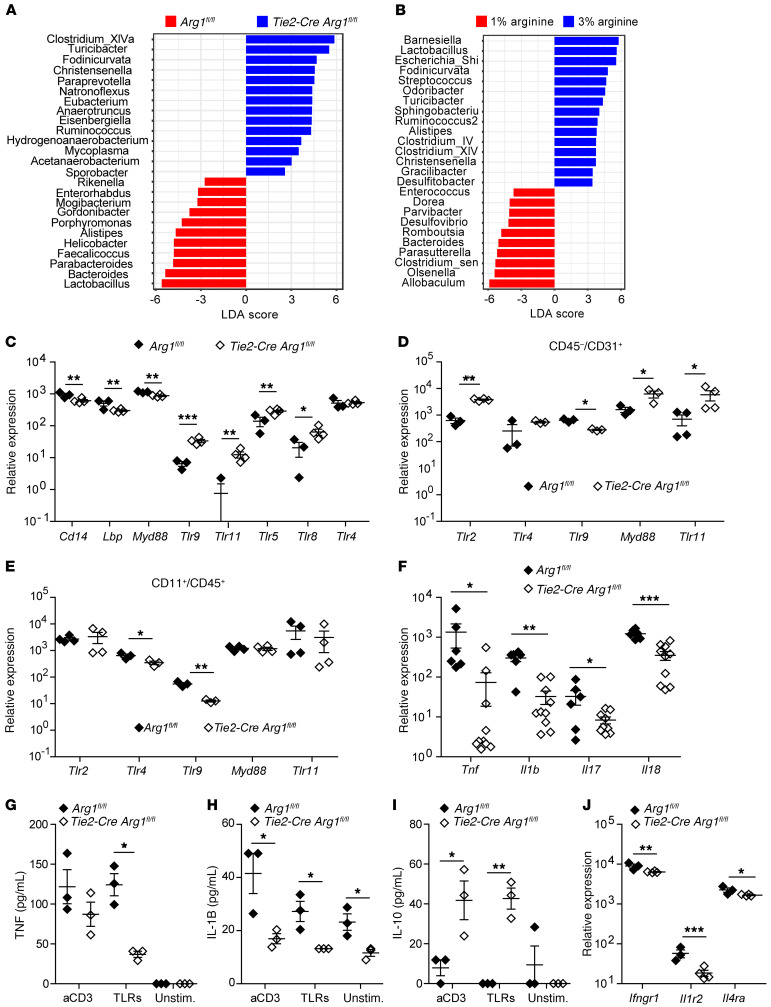

The preceding results indicated that an altered intraluminal polyamine synthesis presumably affects the progression of colitis. As bacteria in the gut are a known source of polyamines (27) and intestinal inflammation is associated with dysbiosis (67), we assessed the composition of the intestinal microbiota in the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) using 16S rRNA analyses. Strikingly, there was a significant expansion of Ruminococcus, Turicibacter, Fodinicurvata, Acetanaerobacteria, Clostridia spp., and Christensenella in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 8A). The latter bacterial genus has been associated with human health (68). Furthermore, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the gut of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice was higher than in WT littermates (2.14 ± 0.58 vs.1.18 ± 0.51; P ≤ 0.05). In contrast, in WT (Arg1fl/fl) mice, Enterobacteriaceae, Helicobacter, spp., and Bacteroides spp., all of which are known to contribute to the destruction of the colonic mucus layer, expanded (ref. 69, Figure 8A, and Supplemental Figures 15 and 16). Similarly to what occurred in the first experiment, enteric anaerobes such as Enterorhabdus (belonging to the order of Eggerthellales) and Alistipes (belonging to the order of Bacteriodales) also expanded in a second experiment in WT (Arg1fl/fl) litters, whereas Fodinicurvata, Anaerotruncus, Mycoplasma, and Clostridium VIX accumulated in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Supplemental Figure 17, A and B). Thus, Arg1 deficiency of the host promotes the accumulation of intestinal microbiota that help to restrain colitis.

Figure 8. Deletion of Arg1 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells and l-arginine supplementation of WT mice promotes the expansion of an antiinflammatory intestinal microbiota and alters the TLR expression pattern and the cytokine (receptor) profile.

(A and B) The composition of the intestinal microbiome was assessed by 16S rRNA analysis of fecal specimens collected from (A) 4 Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl), and (B) 6 WT mice with or without l-arginine supplementation on day 10. Linear discriminant analyses (LDA) were combined with effect size measurements (LEfSe), and the respective results at the genus level (A and B) are displayed. (C–J) The Tlr (C–E), cytokine (F–I), and cytokine receptor profile (J) were analyzed by RNA-Seq (C and J), qPCR (D–F), and ELISA (G–I) in colonic tissues (C, F, and J) and purified intestinal immune (G–I), CD45–CD31+ endothelial (D), and CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells (E). (n = 3–10). The ratios of the mRNA copies of the indicated genes relative to the Hprt copies were calculated. The relative increase in the respective copy numbers of genes from DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice compared with Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) is displayed. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or pairwise Wilcoxon’s tests. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

Next, we tested the impact of an increased availability of l-arginine on the composition of the intestinal microbiome of WT mice. Indeed, similarly to what occurred in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, the supplementation of WT litters with 3% l-arginine led to an accumulation of Christensenella, Ruminococcus, Turicibacter, and Fodinicurvata (Figure 8B, Supplemental Figure 17C, and Supplemental Figure 18). Thus, the protection conferred by l-arginine supplementation is paralleled by the expansion of an anticolitogenic microbiota.

Deletion of Arg1 alters the expression of TLRs and inflammatory cytokines.

Similarly to polyamines, Arg1 exhibits immunomodulatory functions in many cell populations (31). Whereas IL-4– and IL-13–induced Arg1 expression is mediated through activation of the transcription factor STAT6, microbe-driven Arg1 expression occurs via crosslinking of TLRs independently of the STAT6 pathway (14). While the mutual regulation of polyamines and TLRs is well established (65), it is not known whether Arg1 regulates TLR and/or STAT6 expression and subsequent cytokine responses. We found that the colonic expression of Myd88, individual Tlrs, and Tlr-associated molecules differed significantly between Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and WT littermates (Arg1fl/fl) (Figure 8C), whereas the differences of Stat6 mRNA expression did not reach statistical significance (1238 ± 29.32 reads in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice versus 1675.33 ± 297.1 reads in Arg1-expressing littermate controls; n = 3–4; P = 0.069). Remarkably, in the absence of Arg1, the expression of Tlrs was increased in endothelial cells (Figure 8D), but unaltered or decreased in myeloid cells (Figure 8E). These findings indicate an altered response of the host to intestinal microbiota after deletion of Arg1 within the endothelial and hematopoietic cell compartments. Alternatively, these changes in the TLR expression profile might be secondary to the alterations in the composition of the intestinal microbiome.

To investigate the immunological consequences of these alterations for the potential response to microbes, we assessed the cytokine profile in the gut of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl). Notably, the cytokine profile differed significantly between both mouse strains, with a reduction of proinflammatory cytokines and cytokine receptors in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 8, F–J). The mRNA expression of Il1b, Tnf, and Il18, all of which play a pathogenic role in IBD (70–78), was significantly suppressed in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 8F). While significantly more TNF and IL-1B proteins were also recovered from cultures of WT litters (Figure 8, G and H), IL-18 protein was only detected in a few cultures of WT cells upon TLR stimulation (data not shown). Furthermore, significantly more IL-10 protein was recovered from cultures of intestinal immune cells purified from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice than from the respective control cultures (Arg1fl/fl) (Figure 8I). The expression of several cytokine receptors was also reduced in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 8J).

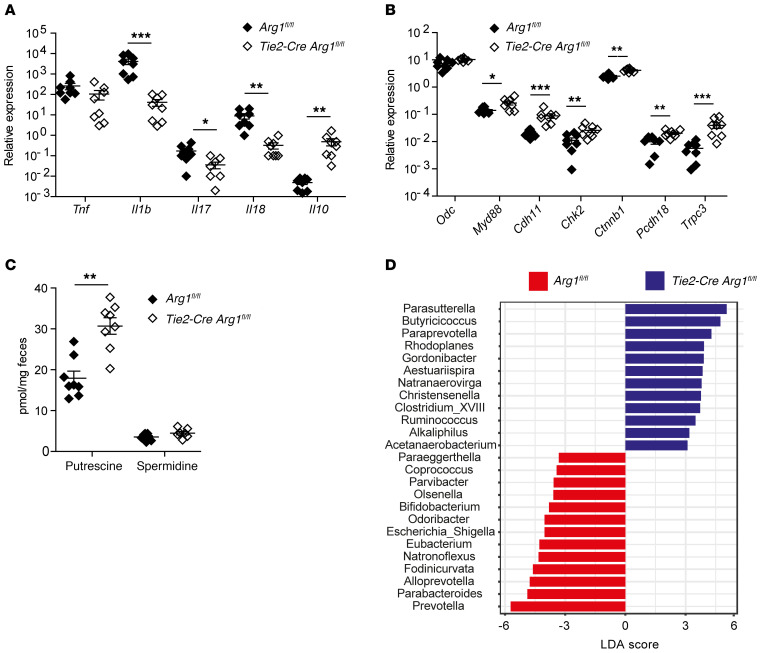

Feces from Arg1-deficient mice protects WT recipients against colitis.

To demonstrate the effect of intestinal microbiota on the outcome of colitis, we reconstituted B6 recipient mice treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics with fresh feces from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing littermates (Arg1fl/fl) and exposed them afterwards to DSS. In accordance with published studies on the pivotal role of the microbiota on the development of colitis (79, 80), untreated control mice developed colitis and lost weight upon DSS application, unlike mice that had received antibiotics (Supplemental Figure 19). FMT from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice into DSS-treated B6 recipients led to reduced intestinal tissue damage and an improved recovery from colitis (Figure 9, A–E, and Supplemental Figure 20), mimicking the protective effect of Arg1 deletion observed in DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice. Control recipients that received FMTs, but no DSS, did not exhibit any phenotype. The less severe colitis observed in DSS-treated B6 recipients of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl microbiota was paralleled by decreased Arg1 expression in mLNs and colonic tissues (Figure 9F) and a significantly diminished inflammatory cytokine profile, which resembled the cytokine pattern seen in DSS-treated Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 10A). In contrast, significantly more Il10 was detected in colonic tissues of FMT recipients from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors. Furthermore, despite unaltered levels of Odc mRNA, the expression of Myd88 and of polyamine target genes, such as cadherin 11 (Cdh11), Chk2, catenin β 1 (Ctnnb1), protocadherin 18 (Pcdh18), and Trpc3, was upregulated in recipients of FMTs from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice (Figure 10B). Most importantly, the accumulation of polyamines in the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl FMT recipients was enhanced (Figure 10C). As observed in Arg1-deficient donor mice (Figure 8A), Christensenella, Paraprevotella, Acetanaerobacteria, and Clostridia expanded in recipients of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl FMTs (Figure 10D and Supplemental Figures 21 and 22). In contrast, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, and Enterobacteriaceae were more abundant in the feces of recipients of FMTs derived from Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) donors (Figure 10D and Supplemental Figure 22). Accordingly, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the gut was increased in recipients of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl feces compared with recipients of WT (Arg1fl/fl) feces (2.54 ± 0.46 vs. 1.49 ± 0.24; P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 9. Microbiota from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice enhance recovery from DSS-induced colitis.

(A) Relative body weight change was monitored over 10 days in naive and DSS-treated B6 recipients of FMTs from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and respective WT control (Arg1fl/fl) donors. (B–E) Severity of colitis in B6 recipients of FMTs from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) donors was monitored by high-resolution endoscopy and histopathological analyses of H&E-stained tissue sections 10 (B and D) and 15 days (C and E) after DSS application (n = 3–8). (F) Expression of Arg1 was analyzed by qPCR in mLNs and colonic tissues of the respective DSS-treated recipients on day 10. Ratios of the mRNA copies of the indicated genes relative to Hprt copies were calculated, and the relative increase in the respective gene copy numbers between FMT recipients from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) donors is displayed. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

Figure 10. Enhanced recovery of FMT recipients from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors is associated with accumulation of polyamines and compositional changes in the intestinal microbiome.

(A and B) Expression of the indicated cytokines (A), Odc, Myd88, and the polyamine target genes Cdh11, Chk2, Ctnnb1, Pcdh18, and short Trcp3 (B) was analyzed by qPCR in colonic tissues of the respective DSS-treated recipients on day 10. Ratio of mRNA copies of indicated genes relative to Hprt copies were calculated, and the relative increase in the respective gene copy numbers comparing 8 FMT recipients from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) donors is displayed. (C) Concentrations of polyamines were assessed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) in the feces of 8 B6 recipients of FMTs from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl and Arg1-expressing (Arg1fl/fl) littermates. (D) Composition of the intestinal microbiome was assessed by 16S rRNA analysis on day 10 after FMT in 3 recipients of feces from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermate (Arg1fl/fl) controls. LDAs were combined with LEfSe, and the respective results at the genus level are displayed. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or pairwise Wilcoxon’s test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate SD of the mean.

When fecal microbiota were transferred from WT donors into either Arg1-deficient or Arg1-competent recipient mice, no significant differences were observed in the percentages of LP myeloid cells and in the expression of cytokines, Myd88, and polyamine target genes between the 2 recipient mouse strains (Supplemental Figure 23).

From these data, we conclude that the transfer of fecal microbiota from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors helps to resolve colitis in recipient WT mice due to the restriction of Arg1 expression, reduced cytokine expression, and enrichment of intestinal microbiota that accelerate the cure of the injured IEC layer due to polyamine accumulation.

Discussion

Arg1 is an arginine-metabolizing enzyme that influences a broad range of immunological and metabolic processes. As global Arg1 deletion causes neonatal death due to the pivotal role of Arg1 in the urea cycle, we resorted in our study to conditional Arg1fl/fl mice. The tissue- or cell type–specific deletion of Arg1 allowed us to assess the function of Arg1 in different compartments and cell types during intestinal inflammation. Arg1 is generally thought to promote tissue repair and regenerative processes and to cause immunosuppression by depriving T lymphocytes of l-arginine. In the work presented here, we identified a proinflammatory, antiresolving role of Arg1 within the endothelial and hematopoietic cell compartment using 3 well-established mouse models of colitis. Arg1 in ILC2s, myeloid, and endothelial cells maintained intestinal inflammation; deletion of Arg1 in either cell compartment alone was insufficient to ameliorate the disease. The protective effect of conditional Arg1 deletion was most prominent after one DSS cycle when other cellular sources of Arg1 were not able to compensate for the loss of Arg1 within the endothelial and hematopoietic cell compartment.

We found that in experimental colitis, endothelial Arg1 expression and subsequent inflammatory changes promoted vessel density, capillary leakage, and immune cell aggregation and transmigration. This is consistent with published data in human IBD, where microvascular dysfunction had been linked to diminished endothelial NO production due to depletion of the NOS substrate l-arginine by enhanced Arg1 activity in the intestinal microvessels and submucosal tissues (38). Similarly, endothelial Arg1 has been implicated in the development of diabetic endothelial dysfunction (81). Decreased availability of NO is known to promote endothelial adhesion and transmigration of inflammatory cells (82). We believe that the mucosal and submucosal damage seen in our DSS colitis model results from the enhanced influx of inflammatory cells in the presence of Arg1. This notion is in line with the previous observation that Nos3–/– mice (lacking endothelial NOS) exhibited more severe colitis than WT controls (83).

Arg1 likely has cell-intrinsic effects on the biology of many cell populations. Altered Tlr expression, for example, might be one of these consequences within the myeloid cell lineage. TLRs enable communication between intestinal microbiota and the immune system of the host, but are also involved in the modulation of the gut microbial flora (84). Parallel to the altered Tlr expression pattern, we detected a shift in the composition of the intestinal microbiome when comparing Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice and Arg1-expressing littermate controls. These compositional changes are likely to contribute to the modified Tlr expression profile. Importantly, the altered intestinal microbiota of Arg1-deficient mice appears to contribute directly to the resolution of colitis: B6 WT mice that had received fecal microbiota from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors not only failed to upregulate Arg1, but also showed a mitigated course of colitis, similar to that seen in Arg1-deficient mice. In addition, the feces of Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice contained more polyamines as compared with that of WT littermates. The accumulated intraluminal polyamines most likely originated from the intestinal microbiota, as all enzymes of the polyamine synthesis pathway in the host remained unaltered. Polyamines presumably support mucosal repair and, thus, the resolution from intestinal inflammation, as seen in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice as well as in WT recipients of fecal microbiota from Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl donors. Further studies need to delineate whether the accumulation of polyamines in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice is due to increased production, altered turnover, and/or reduced consumption. In addition, the bacterial species that (a) thrive in the absence of host Arg1, (b) have the capacity to suppress Arg1 in recipient mice upon transfer, and (c) are suppressed or lost once Arg1 is upregulated need to be defined.

We observed that the proresolving and tissue-protective effects of polyamines correlated with enhanced expression of various polyamine target genes (65, 66), including cadherins, catenins, Trcps, and Chk2 (Figure 7, C–K, and Supplemental Figure 14). In addition, the altered Tlr expression pattern and cytokine profile might reflect a consequence of increased polyamine availability (65).

l-arginine is not only metabolized by Arg1, but also by other enzymes, such as Arg2 and NOS2. Under a regular diet, deletion of Nos2 already ameliorated the colitis to a degree similar to that seen in Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice, whereas deletion of Arg2 showed only a weak effect. Dietary restriction of l-arginine led to a progressive and ultimately lethal wasting disease in WT mice, which was delayed by the individual deletion of Arg1 or Nos2. Simultaneous deletion of Arg1 and Arg2 or Arg1 and Nos2 further reduced disease severity, indicating that Arg1, Arg2, and NOS2 all promote disease due to the consumption of anticolitogenic l-arginine. Conversely, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl mice fed a control diet developed less severe colitis compared with those fed an l-arginine–free chow. Together, these findings argue for an l-arginine–dependent protection that is partially blocked by the activity of Arg1. Indeed, availability of l-arginine is limited in patients with active UC (40, 85). Furthermore, the expression and/or activity of several l-arginine–using enzymes and transporters besides Arg1 is altered in IBD patients (40, 85, 86). As Arg1 inhibitors do not act in an isoform-selective manner or might even function as substrate for NOS or amidotransferases (13, 87, 88), dietary l-arginine supplementation, due to the expansion of polyamine-producing microbiota, is a more promising therapeutic option than the inhibition of arginase enzymatic activity.

Availability of sufficient amounts of l-arginine is known to shift the metabolism of immune cells from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation independently of Arg1 and NOS2 (89). Mechanistically, posttranslational methylation of arginine residues in proteins by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) might be involved, as these enzymes regulate multiple signaling pathways related to cell differentiation, proliferation, metabolism, and function. Although the capacity of l-arginine methylation to modulate inflammatory signaling pathways has been described (90), its role in human pathologies, including colitis, remains to be investigated.

In summary, Arg1 exerted an unexpected inflammatory effect in murine colitis, which involved the activity of myeloid and endothelial cells, an altered composition of the gut microbial flora, and a lack of intestinal polyamines. As Arg1 expression correlated with IBD severity in humans, the results offer alternative avenues for therapeutic intervention that need to be carefully evaluated in the future.

Methods

Further information can be found in Supplemental Methods.

Mice.

Cre-specific Arg1fl/fl mice (14) on a B6 background were obtained by independent backcrossing of respective Cre-deleter and Arg1fl/fl mice with C57BL/6 mice for 12 generations and intercrossing thereafter (15). Conditional Arg1-deficient mice (Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Villin-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Il13-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Cx3cr1-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl), Nos2–/–, Arg2–/–, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl × Nos2–/–, Tie2-Cre Arg1fl/fl × Arg2–/–, and their respective Arg1-expressing littermate controls (Arg1fl/fl) on a B6 background were age and sex matched and used at 7 to 12 weeks of age. Il4/Il13–/– mice and their respective WT controls (Il4/Il13+/+) were obtained from David Vöhringer (Universitätsklinikum Erlangen) and tissues of GF and SPF B6 mice from Marijana Basic and Andrè Bleich (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Hannover, Germany). All other mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were raised in an SPF environment.

Experimental mouse models and high-resolution mini-endoscopy.

Colitis was usually induced by the administration of 2.5% DSS in drinking water for 1 week, followed by normal drinking water until day 10 or 15, in cell-specific Arg1-deficient and Arg1-expressing littermates. Knockouts and littermates were separated 2 to 3 weeks before the start of the experiments. Alternatively, mice were sensitized by epicutaneous application of 3% oxazolone (4-ethoxymethylene-2-phenyl-2-oxazolin-5-one; MilliporeSigma) at a dilution of 4:1 in a mixture of acetone and oil (100 μL) on day 0, followed by an intrarectal administration of 1% oxazolone in 50% ethanol (100 μL) on day 5 (91); 1 mg tamoxifen (MilliporeSigma) per mouse was applied intraperitoneally every 24 hours 3 days before and during the course of the DSS colitis in inducible Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl, Cdh5-Cre Arg1fl/fl, and Cdh5-Cre Arg1wt/wt mice. Feeding with l-arginine–free chow was started 7 days before the application of DSS and continued until the end of the DSS application cycle. The severity of inflammation in the gut was analyzed by colonoscopy (high resolution mini-endoscopy; Karl Storz), as described (92). Briefly, the score was based on the following 5 parameters: (a) thickening of the colon wall, (b) changes in the normal vascular pattern, (c) presence of fibrin, (d) mucosal granularity, and (e) stool consistency. Endoscopic grading was performed for each parameter (score between 0 and 3), leading to a cumulative score between 0 (no signs of inflammation) and 15 (very severe inflammation).

CLSFM and immunofluorescence spinning disc microscopy.

Respective tissue slides were analyzed with the confocal microscope LSM 700 or LSM 780 (ZEISS) using 405 nm, 488 nm, 555 nm, or 639 nm laser lines. Processing of the images was performed with ZEN Software 2009 (ZEISS). Isotype control staining was performed to exclude nonspecific binding of the used antibodies (data not shown). Acquisition was also performed with an inverted ZEISS spinning disc microscope equipped with an Evolve Celta EMCCD camera (Photometics) using 405 nm and 488 nm laser lines. Image analyses were performed with ZEN blue 2012 software (ZEISS).

RNA-Seq.

Profiling of whole-genome transcriptomic patterns was performed with 1 μg of high-quality total RNA per sample by RNA-Seq at the Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Core Unit of the Medical Faculty of FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg. Libraries of the samples were generated using the Illumina Stranded mRNA Library Kit. After sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq-2500 platform, sequences were assigned to their sample of origin according to the indices used. These demultiplexed reads were filtered for rRNAs, tRNAs, mt-rRNAs, and mt-tRNAs. The reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (ENSEMBL GRCm38.85) and assigned to genes using Subread featureCounts 1.5.3. Only uniquely mapping reads that could unambiguously be assigned to a single gene were considered for analysis. The reads were then rlog normalized, and differential expression calls were performed using DESeq2 1.16.1. For gene-level annotation, the biomaRt package was used. For advanced significance analysis, the following parameters were applied: empirical analysis of DGE, P < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction), log2 fold change > 2. Gene-enrichment and functional annotation analysis were performed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN). All original microarray data were deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO GSE151931). Data points from 1 animal were excluded, as subsequent genotyping identified it as a knockout instead of a WT mouse.

Statistics.

The normal distribution of each data set was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For the comparison of the means of normally distributed data of 2 groups, 1-tailed Student’s t test was used, while for more than 2 groups, 1-way ANOVA with post hoc test (Bonferroni’s) was applied. The respective tests used in the case of not normally distributed data were the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test, which was followed with Dunn′s multiple comparisons test if the former was significant. A sample size of at least 3 (n = 3) was used for each sample group in a given experiment, and a P value of 5% (P ≤ 0.05), 1% (P ≤ 0.01), or 0.1% (P ≤ 0.001) was considered significant to accept the alternate hypothesis. GraphPad Prism software was used for statistical analysis.

Study approval.

All procedures were approved by the local ethics committee of FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg. Patients gave written informed consent before participation in the study. All animal studies were performed in accordance with German law and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg and the Animal Experiment Committee of the State Government of Lower Franconia, Würzburg, Germany.

Author contributions

JB, MG, SW, BS, PT, KD, PJO, and JM designed experiments. US carried out mouse breeding. JB, MG, CG, HA, MM, CD, AH, BS, PT, KD, RA, MR, and SW performed experiments, scoring, and histopathology. SL and AE analyzed microarray data. CB and JM wrote the manuscript. The order of first authors was determined alphabetically.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rebekka Staudigl, Maria Glatter, Heike Dornhoff, and Victoria Langer for technical assistance. We thank Marijana Basic and Andrè Bleich for providing tissues of GF mice and David Vöhringer for providing Il4/Il13–/– mice and respective WT littermate controls. We are particularly grateful to the personnel of the Optical Imaging Center Erlangen (OICE; supported by CRC 1181, project Z2) for their help with confocal, 2-photon, and spinning-disc imaging. This study was supported by the Staedtler Stiftung (to JM), the German Research Foundation (DFG; grant MA 2621/4-1 to JM; grant CRC1181, project C04 to JM, US and CB; C02 to RA; and A08 to SW), and by Interreg V BY/CZ118 (to PJO).

Version 1. 07/28/2020

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 09/28/2020

Electronic publication

Version 3. 11/02/2020

Print issue publication

Version 4. 12/22/2020

Corrected Arndt Hartmann in author list.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5703–5720.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI126923.

Contributor Information

Julia Baier, Email: baierjulia@gmx.net.

Maximilian Gänsbauer, Email: maximilian-gaensbauer@t-online.de.

Claudia Giessler, Email: claudia.giessler@uk-erlangen.de.

Harald Arnold, Email: harald.arnold@uk-erlangen.de.

Mercedes Muske, Email: mmuske@gmx.de.

Ulrike Schleicher, Email: ulrike.schleicher@uk-erlangen.de.

Manfred Rauh, Email: Manfred.Rauh@uk-erlangen.de.

Christoph Daniel, Email: Christoph.Daniel@uk-erlangen.de.

Benjamin Schmid, Email: benjamin.schmid@fau.de.

Philipp Tripal, Email: philipp.tripal@fau.de.

Katja Dettmer, Email: Katja.Dettmer@klinik.uni-regensburg.de.

Peter J. Oefner, Email: peter.oefner@klinik.uni-regensburg.de.

Raja Atreya, Email: raja.atreya@uk-erlangen.de.

Stefan Wirtz, Email: stefan.wirtz@uk-erlangen.de.

Christian Bogdan, Email: christian.bogdan@uk-erlangen.de.

Jochen Mattner, Email: jochen.mattner@uk-erlangen.de.

References

- 1.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(5):313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atreya R, et al. In vivo imaging using fluorescent antibodies to tumor necrosis factor predicts therapeutic response in Crohn’s disease. Nat Med. 2014;20(3):313–318. doi: 10.1038/nm.3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atreya R, et al. Antibodies against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induce T-cell apoptosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases via TNF receptor 2 and intestinal CD14+ macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(6):2026–2038. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark M, et al. American gastroenterological association consensus development conference on the use of biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, June 21-23, 2006. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):312–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knox NC, Forbes JD, Van Domselaar G, Bernstein CN. The gut microbiome as a target for IBD treatment: are we there yet? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(1):115–126. doi: 10.1007/s11938-019-00221-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy AN, Allegretti JR. Insights into the role of fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819836893. doi: 10.1177/1756284819836893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattner J, Schmidt F, Siegmund B. Faecal microbiota transplantation-A clinical view. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306(5):310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkinson CP, Grody WW, Cederbaum SD. Comparative properties of arginases. Comp Biochem Physiol B, Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;114(1):107–132. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)02138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotoh T, Mori M. Arginase II downregulates nitric oxide (NO) production and prevents NO-mediated apoptosis in murine macrophage-derived RAW 264.7 cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;144(3):427–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin Y, Liu Y, Nelin LD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediates expression of arginase II but not inducible nitric-oxide synthase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(4):2099–2111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotz M, König T, Ménard S, Gütle D, Bogdan C, Hornef MW. Cytokine-mediated control of lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of small intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology. 2007;122(3):306–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris SM. Recent advances in arginine metabolism: roles and regulation of the arginases. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(6):922–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Kasmi KC, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(12):1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schleicher U, et al. TNF-mediated restriction of arginase 1 expression in myeloid cells triggers type 2 NO synthase activity at the site of infection. Cell Rep. 2016;15(5):1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu G, Morris SM. Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond. Biochem J. 1998;336(Pt 1):1–17. doi: 10.1042/bj3360001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bando JK, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells constitutively express arginase-I in the naive and inflamed lung. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94(5):877–884. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monticelli LA, et al. Arginase 1 is an innate lymphoid-cell-intrinsic metabolic checkpoint controlling type 2 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(6):656–665. doi: 10.1038/ni.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westfall BB, et al. The arginase and rhodanese activities of certain cell strains after long cultivation in vitro. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4(5):567–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.4.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pohjanpelto P, Hölttä E. Arginase activity of different cells in tissue culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;757(2):191–195. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(83)90108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warnken M, Haag S, Matthiesen S, Juergens UR, Racké K. Species differences in expression pattern of arginase isoenzymes and differential effects of arginase inhibition on collagen synthesis in human and rat pulmonary fibroblasts. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381(4):297–304. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindemann D, Racké K. Glucocorticoid inhibition of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) induced up-regulation of arginase in rat airway fibroblasts. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;368(6):546–550. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogdan C. Regulation of lymphocytes by nitric oxide. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;677:375–393. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-869-0_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1028–1040. doi: 10.1038/nm.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pegg AE. Toxicity of polyamines and their metabolic products. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26(12):1782–1800. doi: 10.1021/tx400316s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider J, Wendisch VF. Biotechnological production of polyamines by bacteria: recent achievements and future perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91(1):17–30. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M, et al. Impact of intestinal microbiota on intestinal luminal metabolome. Sci Rep. 2012;2:233. doi: 10.1038/srep00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Martino ML, Campilongo R, Casalino M, Micheli G, Colonna B, Prosseda G. Polyamines: emerging players in bacteria-host interactions. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(8):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das P, Lahiri A, Lahiri A, Chakravortty D. Modulation of the arginase pathway in the context of microbial pathogenesis: a metabolic enzyme moonlighting as an immune modulator. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(6):e1000899. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(2):156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide synthase in innate and adaptive immunity: an update. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(3):161–178. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan C, et al. Chemical generation of nitric oxide in the mouth from the enterosalivary circulation of dietary nitrate. Nat Med. 1995;1(6):546–551. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundberg JO, Govoni M. Inorganic nitrate is a possible source for systemic generation of nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(3):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bäumler AJ, Sperandio V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature. 2016;535(7610):85–93. doi: 10.1038/nature18849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vázquez-Torres A, Bäumler AJ. Nitrate, nitrite and nitric oxide reductases: from the last universal common ancestor to modern bacterial pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;29:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kocna P, Fric P, Zavoral M, Pelech T. Arginase activity determination. A marker of large bowel mucosa proliferation. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1996;34(8):619–623. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1996.34.8.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai RB, Tolia V, Rabah R, Simpson PM, Vijesurier R, Lin CH. Increased colonic ornithine decarboxylase activity in inflammatory bowel disease in children. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(8):1565–1570. doi: 10.1023/A:1026654725101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horowitz S, et al. Increased arginase activity and endothelial dysfunction in human inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(5):G1323–G1336. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akazawa Y, et al. Inhibition of arginase ameliorates experimental ulcerative colitis in mice. Free Radic Res. 2013;47(3):137–145. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.756980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coburn LA, et al. L-arginine availability and metabolism is altered in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(8):1847–1858. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gobert AP, et al. Protective role of arginase in a mouse model of colitis. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):2109–2117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng L, Kelly CJ, Colgan SP. Physiologic hypoxia and oxygen homeostasis in the healthy intestine. A review in the theme: cellular responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;309(6):C350–C360. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00191.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albina JE, Henry WL, Mastrofrancesco B, Martin BA, Reichner JS. Macrophage activation by culture in an anoxic environment. J Immunol. 1995;155(9):4391–4396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, Vijay-Kumar M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2014;104:15.25.1–15.25.14. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1525s104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(4):225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shajib MS, et al. Interleukin 13 and serotonin: linking the immune and endocrine systems in murine models of intestinal inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e72774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevceva L, Pavli P, Husband A, Ramsay A, Doe WF. Dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis is ameliorated in interleukin 4 deficient mice. Genes Immun. 2001;2(6):309–316. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Ming XF. Arginase: the emerging therapeutic target for vascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Front Immunol. 2013;4:149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu C, Yu Y, Montani JP, Ming XF, Yang Z. Arginase-I enhances vascular endothelial inflammation and senescence through eNOS-uncoupling. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2399-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andres PG, et al. Mice with a selective deletion of the CC chemokine receptors 5 or 2 are protected from dextran sodium sulfate-mediated colitis: lack of CC chemokine receptor 5 expression results in a NK1.1+ lymphocyte-associated Th2-type immune response in the intestine. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6303–6312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Platt AM, Bain CC, Bordon Y, Sester DP, Mowat AM. An independent subset of TLR expressing CCR2-dependent macrophages promotes colonic inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6843–6854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waddell A, et al. Colonic eosinophilic inflammation in experimental colitis is mediated by Ly6C(high) CCR2(+) inflammatory monocyte/macrophage-derived CCL11. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5993–6003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim YG, et al. The Nod2 sensor promotes intestinal pathogen eradication via the chemokine CCL2-dependent recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Immunity. 2011;34(5):769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johswich K, et al. Role of the C5a receptor (C5aR) in acute and chronic dextran sulfate-induced models of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(12):1812–1823. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwan WH, van der Touw W, Paz-Artal E, Li MO, Heeger PS. Signaling through C5a receptor and C3a receptor diminishes function of murine natural regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210(2):257–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jain U, Woodruff TM, Stadnyk AW. The C5a receptor antagonist PMX205 ameliorates experimentally induced colitis associated with increased IL-4 and IL-10. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168(2):488–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grisham MB, Pavlick KP, Laroux FS, Hoffman J, Bharwani S, Wolf RE. Nitric oxide and chronic gut inflammation: controversies in inflammatory bowel disease. J Investig Med. 2002;50(4):272–283. doi: 10.2310/6650.2002.33281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coburn LA, et al. L-arginine supplementation improves responses to injury and inflammation in dextran sulfate sodium colitis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh K, et al. Dietary arginine regulates severity of experimental colitis and affects the colonic microbiome. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:66. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kibe R, et al. Upregulation of colonic luminal polyamines produced by intestinal microbiota delays senescence in mice. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4548. doi: 10.1038/srep04548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hambrecht R, et al. Correction of endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure: additional effects of exercise training and oral L-arginine supplementation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):706–713. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lucotti P, et al. Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(5):E906–E912. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hatoum OA, Binion DG, Otterson MF, Gutterman DD. Acquired microvascular dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease: Loss of nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pegg AE. Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(9):880–894. doi: 10.1002/iub.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Timmons J, Chang ET, Wang JY, Rao JN. Polyamines and gut mucosal homeostasis. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2012;2(Suppl 7):001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tamboli CP, Neut C, Desreumaux P, Colombel JF. Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53(1):1–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goodrich JK, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martens EC, Neumann M, Desai MS. Interactions of commensal and pathogenic microorganisms with the intestinal mucosal barrier. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(8):457–470. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neurath MF. Current and emerging therapeutic targets for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(5):269–278. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kanai T, et al. Macrophage-derived IL-18-mediated intestinal inflammation in the murine model of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(4):875–888. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Siegmund B, et al. Neutralization of interleukin-18 reduces severity in murine colitis and intestinal IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha production. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281(4):R1264–R1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishikura T, et al. Interleukin-18 overproduction exacerbates the development of colitis with markedly infiltrated macrophages in interleukin-18 transgenic mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(8):960–969. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nowarski R, et al. Epithelial IL-18 equilibrium controls barrier function in colitis. Cell. 2015;163(6):1444–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Günther C, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-α-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477(7364):335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]