Abstract

Salmonella spp. are recognized as important foodborne pathogens globally. Salmonella enterica serovar Rissen is one of the important Salmonella serovars linked with swine products in numerous countries and can transmit to humans by food chain contamination. Worldwide emerging S. Rissen is considered as one of the most common pathogens to cause human salmonellosis. The objective of this study was to determine the antimicrobial resistance properties and patterns of Salmonella Rissen isolates obtained from humans, animals, animal-derived food products, and the environment in China. Between 2016 and 2019, a total of 311 S. Rissen isolates from different provinces or province-level cities in China were included here. Bacterial isolates were characterized by serotyping and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 14 clinically relevant antimicrobials were obtained by broth microdilution method. S. Rissen isolates from humans were found dominant (67%; 208/311). S. Rissen isolates obtained from human patients were mostly found with diarrhea. Other S. Rissen isolates were acquired from food (22%; 69/311), animals (8%; 25/311), and the environment (3%; 9/311). Most of the isolates were resistant to tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, and ampicillin. The S. Rissen isolates showed susceptibility against ceftriaxone, ceftiofur, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, and azithromycin. In total, 92% of the S. Rissen isolates were multidrug-resistant and ASSuT (27%), ACT (25%), ACSSuT (22%), ACSSuTAmc (11%), and ACSSuTFox (7%) patterns were among the most prevalent antibiotic resistance patterns found in this study. The widespread dissemination of antimicrobial resistance could have emerged from misuse of antimicrobial agents in animal husbandry in China. These findings could be useful for rational antimicrobial usage against Salmonella Rissen infections.

Keywords: human salmonellosis, Salmonella Rissen, multidrug resistance, minimum inhibitory concentration, public health

1. Introduction

Salmonella is a gram-negative bacterium that belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family [1]. Salmonella spp. are the most important bacterial pathogens among other foodborne pathogens and are responsible for causing gastroenteritis in humans [2]. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica includes more than 2600 serotypes and are capable of infecting animals and humans [3,4]. Infections caused by Salmonella spp. in farm animals has been documented as the leading cause of considerable economic losses worldwide [5,6].

Nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica are responsible for causing significant numbers of food-borne diseases in many countries [1,3,7]. Salmonella enterica serovar Rissen (S. Rissen) is one of the major Salmonella serovars generally found in swine and swine products, chicken meat, and humans with gastrointestinal diseases in different countries [8,9]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported S. Rissen as one of the top twenty most common Salmonella serovars linked with human infections [7].

The worldwide increase of foodborne infections linked with antimicrobial-resistant pathogenic microorganisms and the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AR) is one of key concerns in developing and developed countries [10,11]. On the other hand, another concern for human health in different countries is the emergence of multi-antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella strains and the continuous spread of those clones [4,12,13,14]. Salmonella spp. are responsible for causing key financial losses in the health care system as well as in the food industries [3].

Incidents of multidrug resistance in Salmonella spp., including other bacterial pathogens causing enteric diseases, has been reported in many continents and became a major health issue as this can spread internationally [15,16,17]. The food chain constitutes one of the most important mediums for spreading of antimicrobial resistance [18]. The farm animals are the potential pool of bacterial pathogens harboring multidrug resistance. The utilization of antimicrobials in agriculture for growth promotion of animals and for the treatment of the diseases caused by bacterial pathogens can lead to select antimicrobial-resistant pathogens [3,6]. In different studies, both pig and chicken meats have been documented as the reservoir for drug-resistant Salmonella spp. [1,8]. This spread of drug resistance through the food chain is considered as a major public health concern [19,20]. Therefore, an improved surveillance of multidrug resistance and resistance determinants in Salmonella is crucial for providing data on the magni tude and spectrum of AR in foodborne pathogens affecting humans and animals in different countries.

Increased AR has been reported in many serovars of Salmonella spp. globally [6,21]. However, very limited information on the occurrence of antibiotic resistance of Salmonella Rissen is available in China and elsewhere [22]. The objective of the present study was to determine the antimicrobial resistance patterns and properties of 311 Salmonella Rissen isolates obtained from humans, animals, animal-derived food products, and the environment from 15 provinces or province-level cities between 2016 and 2019 in China. We also conducted whole genomic sequencing (WGS) to investigate the antimicrobial resistance determinants among the selected MDR isolates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Source of Salmonella Isolates

The Chinese local surveillance system, including over 20 provinces or municipal cities’ CDCs in China, was led by the Shanghai CDC. The overall database has over 50,000 Salmonella clinical isolates collected since 2006, when Shanghai CDC joined the Global Foodborne Infections Network under the World Health Organization. During the past decades, in line with local CDCs in mainland China, Shanghai CDC gradually expand to collect Salmonella isolates all over China, including samples from humans, animals, food and the environment. The Salmonella Rissen isolates and their corresponding metadata were obtained from the Chinese local surveillance system. We selected 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained during 2016 to 2019 for this investigation, due to the following reasons: (1) these isolates represent the most recent isolates in the past four years at the time of preparation the manuscript; (2) these isolates were selected to capture the largest regions of mainland China.

2.2. Identification of Salmonella Isolates

The isolation of the microorganism was performed based on the protocol suggested by the World Organization for Animal Health Terrestrial Manual [23]. According to this recommendation, isolation of the microorganism was done on xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (XLD agar) plates. Briefly, 25 g of bacterial sample was pre-enriched in buffered peptone water (BPW) at 37 °C overnight. The enriched samples were then inoculated on modified semi-solid Rappaport–Vassiliadis (MSRV) and incubated at 42 °C for 24 h. A loopful of the positive growth taken from the MRSV colony was further inoculated on to xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) and was kept in an incubator for overnight. Among the suspected colonies, one colony was seeded in Luria–Bertani (LB) for DNA extraction and validated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Distinctive round red colonies with black centers on xylose lysine deoxycholate media were considered as probable Salmonella colonies.

2.3. DNA Extraction by Boiling Method and PCR

DNA extraction was done by boiling method. A 1 mL bacterial sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000× g and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of DNase-RNase-free distilled water by vortexing. The tube was centrifuged at 14,000× g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded carefully. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of DNase-RNase-free distilled water by vortexing. The microcentrifuge tube was incubated for 15 min at 100 °C and immediately chilled on ice. The tube was centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000× g at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and incubated again for 10 min at 100 °C and chilled immediately on ice. An aliquot of 5 μL of the supernatant was used as the template DNA in the PCR reaction.

2.4. PCR Amplification of stn Gene

PCR for stn gene, for enterotoxin, was performed to confirm Salmonella spp. as recommended previously [24]. Extracted DNA was amplified by PCR using gene specific primers for stn forward primer (F1) 5′-TTGTGTCGCTATCACTGGCAACC-3′ and reverse primer (R1) 5′-ATTCGTAACCCGCTCTCGTCC-3′. The PCR protocol for amplification was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles, (i) denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s; (ii) primer annealing at 58 °C for 45 s, and (iii) primer extension at 72 °C for 45 s followed by final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

2.5. Serotyping by Agglutination Assay

We characterized O and H antigens by agglutination with hyperimmune sera and the serotype of Salmonella spp. was identified as per the Kauffmann–White scheme [25].

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

Susceptibility to different antimicrobials of all selected isolates was performed as minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations using a broth microdilution method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [CLSI, 2016]. The broth microdilution method was performed using Muller–Hinton broth and Muller–Hinton agar. In total, 14 clinically relevant antimicrobials from different classes were used to obtain the MIC values. The antimicrobial classes and the MIC range (mg/L) used in this susceptibility assay were penicillin (ampicillin, AMP, 0.125–128), beta-lactams (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, AMC, 0.5/0.25–64/32), cephems (ceftriaxone, CRO, 0.06–64; cefoxitin, FOX, 0.125–128; ceftiofur, TIO 0.06–64), aminoglycosides (gentamicin, GEN, 0.125–128; streptomycin, STR, 0.125–128), tetracyclines (tetracycline, TET, 0.125–128), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, CIP, 0.03–32; nalidixic acid, NAL, 0.125–128), sulfonamides (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, COT, 0.12/2.38–4/76; sulfisoxazole, FIS, 8–1024), macrolides (azithromycin, AZI, 0.125–128), and phenicols (chloramphenicol, CHL, 0.125–128). The MIC values of the antibiotics used were recorded for all bacterial isolates and compared to the CLSI breakpoints (for ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, cefoxitin, gentamicin, streptomycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and chloramphenicol) and the breakpoint recommendations from the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) (for ceftiofur, sulfisoxazole). Salmonella Rissen isolates that showed resistant to more than three classes of antimicrobial agents were defined as multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates.

2.7. Genomic Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

To better investigate the relation between the phenotypic antimicrobial resistance and its genetic determinants, genomic sequencing and bioinformatic analysis were conducted on eight selected extensive multidrug S. Rissen isolates among each host, including five from human origin, two from swine origin, and one from chicken meat origin.

The genomic DNA library was constructed using Nextera XT DNA library construction kit (Illumina, USA, no: FC-131-1024), followed by genomic sequencing using Miseq Reagent Kit v2 300cycle kit (Illumina, USA, No: MS-102-2002). High-throughput genome sequencing was achieved by the Illumina Miseq sequencing platform, as previously described [26,27,28]. The quality of sequencing was checked with FastQC toolkit, while low-quality sequences and joint sequences were removed with trimmomatic [29]. The genome assembly was performed with SPAdes 4.0.1 for genomic scaffolds [30], using the “careful correction” option in order to reduce the number of mismatches in the final assembly with automatically chosen k-mer values by SPAdes. QUAST [31] was used to evaluate the assembled genomes through basic statistics generation, including the total number of contigs and contig length. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) software (http://www.github.com/tseemann/mlst) was applied for the sequence type of the isolates for the in-house database. Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes was conducted using ABRicate software (http://www.github.com/tseemann/abricate).

2.8. Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were officially approved by the Shanghai CDC, which was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Human Isolates of S. Rissen Are Dominant

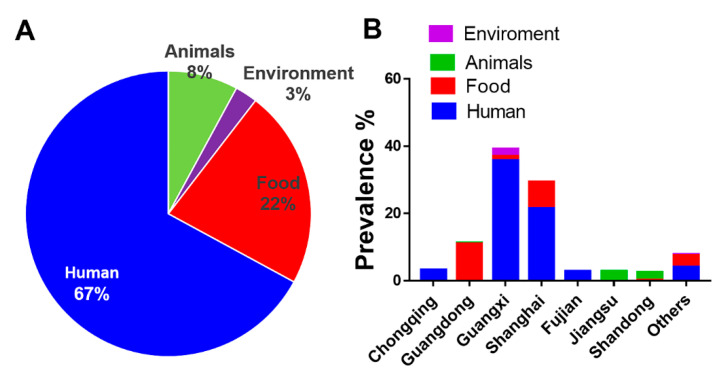

Human salmonellosis is considered as one of the key public health concerns worldwide. In this study, we worked on 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained from different sources. We obtained the greatest number of S. Rissen isolates from human (67%; 208/311). Out of 208 human samples, we obtained 103 samples from patients with diarrhea, five samples from patients with bacterimia, and 100 samples from asymptomatic carriers. Other S. Rissen isolates were obtained from animal-derived foods (22%; 69/311), animals (8%; 25/311), and the environment (3%; 9/311) (Figure 1A). Among 69 samples from animal-derived foods, one sample was obtained from beef, 20 samples were from chicken meat, three samples were from duck meat, and 45 samples were obtained from pork or pig meat. Among 25 samples obtained from animals, 17 samples were obtained from chicken and eight samples were of swine origin.

Figure 1.

The origin and geographic dynamics of 311 Salmonella Rissen isolates examined in this study. (A) Prevalence of 311 S. Rissen isolates according to the sample sources used in this study. The different sample sources included humans, animals, animal-derived foods, and the environment. (B) Prevalence, geographical distribution, and different sources of 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained from different provinces or province-level cities in China.

We found most of the S. Rissen isolates from humans were from Guangxi and Shanghai in China (Figure 1B). In a major Salmonella outbreak in the US in 2009, more than 80 people were infected by S. Rissen pathogens over four different states of the country [32]. Previous reports demonstrated a number of cases of human infections caused by S. Rissen in Demark, Ireland, and UK [33,34]. The risk of salmonellosis in humans as well as the increase of MDR Salmonella clones highlights the importance of the surveillance of rising S. Rissen pathogens. It has been found that about 95% of human salmonellosis is linked with the eating of undercooked or contaminated swine meat [35,36,37,38]. Salmonella could affect humans at any stages of the food production chain [39,40]. A recent study [41] demonstrated that the Salmonella contamination in animal-derived foods in Guangdong Province in China is very severe, posing significant risk for human infections. Considering the sporadic cases of Salmonella Rissen in humans, this study could shed light on the characterization of antibiotic susceptibility profile of S. Rissen isolates in humans, causing diarrhea and bacteremia, with the largest number of isolates included to date. This is of clinical significance and could guide regional risk assessments for future outbreaks in China.

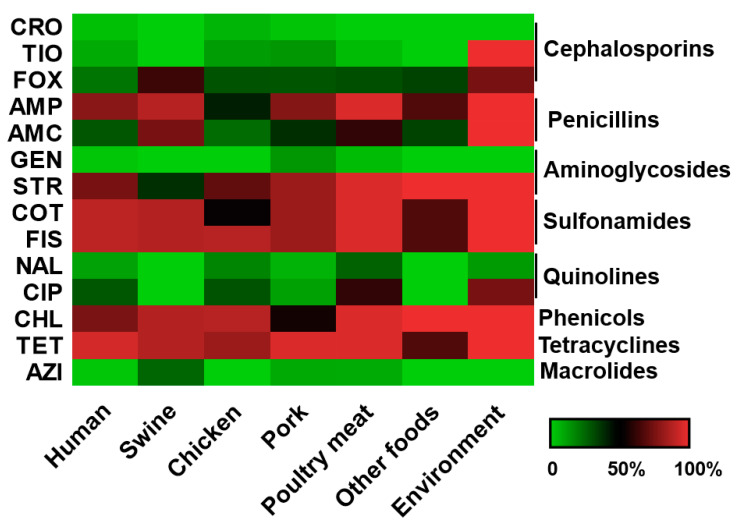

3.2. S. Rissen Showed Resistant Properties Against Important Antimicrobials

We found most of the S. Rissen isolates showed resistance to tetracycline, streptomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, sulfisoxazole, and ampicillin (Figure 2) which correlates well with other studies and could be linked with the findings that the antimicrobials were commonly used in swine farms in China [42,43]. Tetracycline is one of the most commonly used antimicrobial agents in humans, as well as in veterinary medicine, and is also one of the most extensively used drugs in animal husbandry in China and many other nations. Previous studies from different countries reported a high prevalence of tetracycline resistance in Salmonella Rissen [33,44,45]. High resistance to tetracycline could be explained by its extensive use to feed animals and this result was in accordance with other previous studies [46,47].

Figure 2.

The heatmap of antimicrobial resistance profile for S. Rissen isolates according to sample sources based on minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values. The 14 antimicrobials used in this study were as follows: ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (AMC), ceftriaxone (CRO), cefoxitin (FOX), ceftiofur (TIO), gentamicin (GEN), streptomycin (STR), tetracycline (TET), ciprofloxacin (CIP), nalidixic acid (NAL), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (COT), sulfisoxazole (FIS), azithromycin (AZI), and chloramphenicol (CHL). Each cell refers to the percentage of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial isolates recovered from different sample sources with a particular antimicrobial agent, from low (green) to high (red).

Previous reports described that Salmonella isolates displayed resistance against important antibiotics such as tetracycline, streptomycin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, amoxicillin, neomycin, and sulfonamide [48,49]. Another report [50] demonstrated the widespread occurrence of antibiotic resistance to ampicillin, streptomycin, tetracycline, sulfonamide, and chloramphenicol found in S. Rissen isolates from swine farms in upper northern Thailand. Among the S. Rissen isolates obtained from pigs in Europe, tetracycline was found to be the most common resistance phenotype [44,49]. A recent study [46] reported that 85.7% of the S. Rissen isolates from swine demonstrated resistance to tetracycline in Shandong Province, China. Garcia-Feliz et al. [51] reported 50% of the S. Rissen isolates, originating from pigs, were resistant to tetracycline alone. In another study, S. Rissen isolates from Thailand were resistant to many antibiotics such as tetracycline, ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, and chloramphenicol [52]. Emerging resistance of S. Rissen isolates to clinically relevant antimicrobials are an important public health issue.

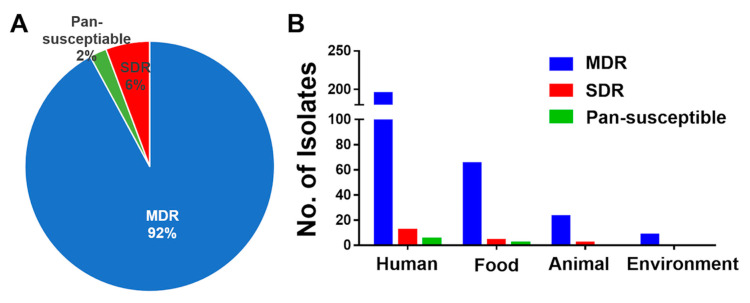

3.3. High Prevalence of MDR S. Rissen Isolates

In total, 92% of the S. Rissen isolates were found to be multidrug-resistant (MDR) in our study (Figure 3A). MDR is defined as resistance to three or more different classes of antibiotics. MDR S. Rissen isolates were obtained from all sources such as humans, food products, animals, and environments (Figure 3B). S. Rissen demonstrating multi-antimicrobial resistance has been recorded in Spain previously, and S. Rissen isolates showed MDR properties against four to nine different important drugs [51]. Studies by Tadee et al. [53] in Thailand reported that S. Rissen isolates demonstrated resistance against more than three drugs. Previously, Garcıa-Fierro et al. [54] described that 19% of the S. Rissen isolates were multidrug-resistant; the isolates were mostly (74%) resistant to tetracycline drug and also demonstrated significant percentages of resistance against ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and chloramphenicol, which supports our findings here.

Figure 3.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) properties of 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained from humans, animals, animal-derived foods, and the environment in China. (A) Percentage of S. Rissen isolates found to be MDR in our study. (B) MDR S. Rissen isolates found from different sources such as humans, food products, animals, and environments. SDR = single-drug resistance, defined as resistance against one type of antimicrobial class.

The high incidence of MDR Salmonella Rissen in China found in this study is a serious public health concern. The emergence and dissemination of MDR Salmonella are frequently associated with the acquisition of bacterial mobile genetic elements (MGEs) [16,55]. The high occurrence of antibiotic resistance found in this study demonstrated the harmful impact of the unrestricted use of such antibiotics for growth enhancement, as well as in medicine, in China.

3.4. Genomic Characterization of an Extensively Drug Resistant Salmonella Rissen

Table 1 described the results of genomic analysis of S. Rissen isolates with different antimicrobial resistance genes found in the isolates, which could confer high level of antimicrobial resistance. Genomic analysis of tetracycline-resistant S. Rissen isolates showed the presence of tet (A) resistance genes responsible for tetracycline resistance. Resistance to tetracycline antimicrobials is controlled by tet genes and these genes are generally involved in active efflux of the antimicrobials, as well as in ribosomal protection and enzymatic modification. Among several tet genes responsible for tetracycline resistance in Salmonella, tet genes belong to classes A, B, C, D, and G were found most frequent types of genes [56,57]. blaTEM-1B resistance genes were found in ampicillin-resistant S. Rissen isolates in this study. The dominant bla gene conferring ampicillin resistance in most of the Salmonella serovars was found to be different types of blaTEM [58,59,60]. Different aminoglycoside resistance genes such as aadA2, aadA1, aac(6’)-Iaa, and aph(3″)-lld were found here and are demonstrated in Table 1. Among different mechanisms of aminoglycoside resistance, enzymatic modification is the most prevalent in pathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella spp. [4,61]. Through genome analysis, we found the sul3 antibiotic resistance gene in sulfaxisazole-resistant Rissen isolates. This same resistance gene sul3 was also found in trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant isolates. Another important gene dfrA12 was found in trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole-resistant S. Rissen isolates in our genomic study (Table 1). It has been found in many studies that resistance to sulfonamide antimicrobials is primarily mediated by the sul1, sul2, and sul3genes [62,63]. The major mechanism of trimethoprim resistance is the existence of integron-borne dihydrofolate reductases. The dfrA12 gene was among the different genes encoding dihydrofolate reductases reported in Salmonella previously [64,65,66,67]. The presence of different antimicrobial resistance genes in S. Rissen isolates mainly obtained from human demonstrates their MDR properties.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and whole genome analysis of MDR S. Rissen strains obtained in this study.

| Antibiotic Classes | SAL02425 | SAL02454 | SAL02475 | SAL02482 | SAL02490 | SAL02560 | SAL02592 | SAL02603 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | MIC (mg/L) |

Related Genes | |||

|

Antimicrobial

Susceptibility testing |

β-Lactam and β-Lactams inhibitor | AMP | >32 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-14 |

>32 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-14 |

>32 | blaCTX-M-14 | >32 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-27 |

>32 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-55 |

16 | 32 | bla TEM-1B | 32 | bla TEM-1B | |

| AMC | >32/16 | >32/16 | >32/16 | >32/16 | >32/16 | 8/4 | >32/16 | >32/16 | ||||||||||

|

Amino-

glycoside |

STR | 32 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa, aph(3 ″)-lld | 64 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa | 64 | aadA2, aac(6′)-Iaa | >64 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa | >64 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa, ant(3 ″)-Ia | >64 | aadA2, aac(6′)-Iaa | >64 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa, ant(3 ″)-Ia | >64 | aadA2, aadA1, aac(6′)-Iaa | |

| GEN | >16 | >16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Macrolides | AZI | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| Quinolone | CIP | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| NAL | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Phenicol | CHL | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 32 | CmlA2 | 32 | CmlA2 | 32 | CmlA2 | 32 | CmlA2 | |||||

| Sulfaxisazole | FIS | >256 | sul3 | >256 | sul3 | 1 | >256 | sul3 | >256 | sul3 | 1 | >256 | sul3 | >256 | sul3 | |||

| Trimethoprim/Sulphonamide | COT | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | >32/608 | dfrA12 | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | >32/608 | dfrA12 | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | >32/608 | dfrA12, sul3 | |

| Tetra-cyclines | TET | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | >32 | tet(A) | |

| Cephalo-sporines | CRO | >64 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-14 |

>64 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-14 |

32 | blaCTX-M-14 | >64 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-27 |

>64 |

bla

TEM-1B

blaCTX-M-55 |

2 | 4 | bla TEM-1B | 4 | bla TEM-1B | ||

| TIO | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 1 | >8 | >8 | ||||||||||

| FOX | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 32 | 32 | ||||||||||

| Host | Human | Human | Human | Human | Human | Live Swine | Chicken meat | Pork | ||||||||||

| Collection place | Fujian | Shanghai | Fujian | Chongqing | Chongqing | Jiangsu | Guangdong | Guangxi | ||||||||||

| Sequence type | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ST469 | ||||||||||

3.5. S. Rissen from Animal and Animal Products with Antimicrobial Resistance

We found 17% of S. Rissen isolates came from swine and swine products, 5% of isolates were from chicken, 1% were seafood isolates, and 3% of isolates were from the environment in this study. Pigs are often nonsyndromic carriers of different Salmonella serovars [68] and previous studies have shown that swine products could be easily contaminated by Salmonella spp. [21,53]. We found S. Rissen isolates from animals and animal-originated food products showed resistance against different clinically relevant antibiotics (Figure 2). The dissemination of drug resistance by animal meat products poses a serious public health concern. Previous studies confirmed swine production units in Spain as a main reservoir of S. Rissen [49,51]. Hendriksen et al. [33] previously reported that 80% of the S. Rissen isolates examined in Denmark were associated with swine products and showed resistance to tetracycline. The study also reported a similar kind of antimicrobial resistance pattern for undercooked as well as and ready-to-eat (RTE) food products found in Thailand. In another research work in South Korea, Salmonella Rissen was among the major serovars found in healthy as well as diarrhoeal swine, including a high incidence of resistance to tetracycline, streptomycin, and sulfamethoxazole [9]. Some literatures have reported that S. Rissen isolates have also been obtained from other food-producing animals, as well as animal-originated food products, such as poultry and beef, and from human clinical samples, though sometimes with less frequency than other Salmonella serovars [45,69,70,71]. This shows the rising of a successful S. Rissen clone that can have an effect globally by transmitting to different countries. A very recent study [11] found high levels of resistance among S. Rissen isolates recovered from a pig production chain in Thailand and the isolates showed a very high percentage of resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and nearly 80% of the bacterial isolates showed a MDR pattern. In another study in the northeastern part of Thailand and Laos, S. Rissen isolates showed high frequency of resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, sulfonamides, and trimethoprim in a swine production unit [72]. These reports showed the significance of stringent monitoring and maintaining of a clean environment in the pork production system. We found very few (3%) S. Rissen isolates from the environment and it is interesting to note that sometimes Salmonella can survive in the environment for a long time [73,74]. Routine surveillance of pig and poultry farms for Salmonella and rapid intervention will significantly improve global food safety and security.

3.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern of the S. Rissen Isolates

The S. Rissen isolates showed susceptibility or low-level resistance against ceftriaxone, ceftiofur, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, and azithromycin (Figure 2). Antibiotic classes, such as fluoroquinolones and beta-lactams, are commonly used in hospitals to treat infections caused by Salmonella spp. Quinolones or fluoroquinolones are broad-spectrum antibacterial agents and are used as an important drug of choice for the treatment of the invasive infections in humans and widely used in veterinary medicine. Fluoroquinolone compounds exert their effects by inhibition of some bacterial topoisomerase enzymes, such as DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. A small region of gyrA was identified as “quinolone resistance-determining region”, or QRDR, and changes in this QRDR region were found in bacterial pathogens with resistance to fluoroquinolones [75]. Beta-lactam antibiotics, which include the cephalosporins class, interfere with the cell wall synthesis by inhibiting the bacterial enzymes. One of the major causes of beta-lactam resistance is by antibiotic-inactivating enzymes known as beta-lactamases [75].

In accordance with our data, some reports in Thailand also demonstrated low-level resistance or susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, and ceftiofur. This could be possible because of the restricted use of these antimicrobial agents in the animal-derived food production systems [76,77,78]. Quinolones and third-generation cephalosporins are the antimicrobials most extensively used to treat both human and animal infections. Finding susceptibility to third generation cephalosporins is important, as this group of antibiotics is frequently used against highly invasive bacterial infections.

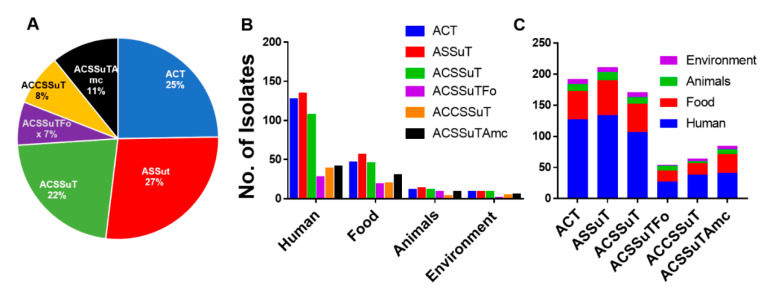

3.7. ASSuT (Ampicillin, Streptomycin, Sulphonamide, and Tetracycline), and ACSSuT (Ampicillin, Chloramphenicol, Streptomycin, Sulphonamide, and Tetracycline) Pattern of Antimicrobial Resistance

For nontyphoidal Salmonella or NTS, resistance to five antibiotics, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulphonamide, and tetracycline (ACSSuT), is an important resistance pattern. Another important pattern of resistance, ASSuT (ampicillin, streptomycin, sulphonamide, and tetracycline), has also emerged for Salmonella species and other foodborne pathogens. S. Rissen isolates in this study showed different antibiotic resistance patterns. The occurrence of clinically relevant tetra- or penta-drug resistance patterns such as ASSuT (27%), and ACSSuT (22%) were high, respectively. ACT (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline) (25%), ACSSuTAmc (11%), and ACSSuTFox (7%), were among the other prevalent antibiotic resistance patterns found in this study (Figure 4). ACT (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline), ACSSuTAmc (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid), and ACSSuTFox (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, and cefoxitin) antibiotic resistance patterns in S. Rissen isolates were mainly obtained from humans and animal-derived foods (Figure 4). Some of these important antimicrobial resistance patterns were also reported in our recent study on Salmonella Typhimurium [21]. Figure 4A, with the pie chart, shows the percentage of different antimicrobial resistance patterns of all 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained from different sources in China. Figure 4B,C shows different antimicrobial resistance patterns of all 311 S. Rissen isolates according to different sample sources.

Figure 4.

The antimicrobial resistance pattern of Salmonella Rissen isolates. (A) Pie chart showing percentage of different antimicrobial resistance patterns of all 311 S. Rissen isolates obtained from different sources in China. (B,C) Different antimicrobial resistance patterns of all 311 S. Rissen isolates according to sample sources.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

As a retrospective epidemiological investigation, our study described a high incidence of antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella Rissen isolates recovered from diverse sources, especially from humans in China. Our results provide the first outline of rising drug resistance among S. enterica serovar Rissen, causing humans salmonellosis in China, which is relevant for both food safety and public health. The results we obtained here are more representative of China and could be useful for potential risk evaluation in the future. These findings could signify the possible risk of antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella infections in certain provinces or province-level cities in China. Therefore, there must be continuous epidemiological investigations on infections caused by Salmonella spp. in humans and animals and more studies are needed to advance our understanding about the development and dissemination of MDR strains. Pigs and swine products are one of the key reservoirs of Salmonella Rissen and there is a possibility that enhanced multiple antimicrobial resistance in S. Rissen will result in a rising number of human cases. Therefore, further whole genomic sequencing investigations could aim to resolve the genetic diversity in the S. Rissen population, as well as the antimicrobial resistance genetic makeup in certain critical antibiotic resistant S. Rissen isolates and the potential mechanism for their dissemination. Finding susceptibility to quinolones and third-generation cephalosporins is important and the data presented by this study could be used to recommend suitable therapeutic agents against Salmonella Rissen infections in China. Food safety should be improved and uncontrolled use of antimicrobials in growing food-producing animals must be closely monitored to ensure the public health safety.

Author Contributions

X.X. provided most of the bacterial isolates as well as the mete-data information, and conducted the experiments, S.B. made the figures and data analysis for this work, G.G. provided the bacterial isolates from diverse region of China and conducted the experiments. X.X., S.B. and G.G. made the first draft of manuscript. M.E. conducted the genomic sequencing and data analysis. Y.L. provided essential comments and helped with the editing of the manuscript. M.Y. conceived the idea, collected the data, and assisted with data analysis, rewrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Program on Key Research Project of China (2019YFE0103900; 2017YFC1600103; 2018YFD0500501), as well as European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 861917—SAFFI, Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19C180001) and Zhejiang Provincial Key R&D Program of China (2020C02032).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Boyle E.C., Bishop J.L., Grassl G.A., Finlay B.B. Salmonella: From pathogenesis to therapeutics. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:1489–1495. doi: 10.1128/JB.01730-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—Foodborne Diseases Active Sur-veillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 1996–2012. Wkly. Rep. 2013;62:283–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crump J.A., Sjölund-Karlsson M., Gordon M.A., Parry C.M. Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Laboratory Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Antimicrobial Management of Invasive Salmonella Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:901–937. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas S., Li Y., Elbediwi M., Yue M. Emergence and Dissemination of mcr-Carrying Clinically Relevant Salmonella Typhimurium Monophasic Clone ST34. Microorganisms. 2019;7:298. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengtsson B., Greko C. Antibiotic resistance--consequences for animal health, welfare, and food production. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014;119:96–102. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.901445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jajere S.M. A review of Salmonella enterica with particular focus on the pathogenicity and virulence factors, host specificity and antimicrobial resistance including multidrug resistance. Vet. World. 2019;12:504–521. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.504-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Food Safety Authority. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses. EFSA J. 2017;15:e05077. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vo A.T.T., van Duijkeren E., Fluit A.C., Heck M.E.O.C., Verbruggen A., Maas H.M.E., Gaastra W. Distribution of Salmonella enterica serovars from humans, livestock and meat in Vietnam and the dominance of Salmonella Typhimurium phage type 90. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;113:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim S.K., Lee H.S., Nam H.M., Jung S.C., Koh H.B., Roh I.S. Antimicrobial resistance and phage types of Salmonella isolates from healthy and diarrheic pigs in Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009;6:981–987. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalton C.B., Gregory J., Kirk M.D., Stafford R.J., Givney R., Kraa E., Gould D. Foodborne disease outbreaks in Australia, 1995 to 2000. Commun. Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2004;28:211–224. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2004.28.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasertsee T., Chuammitri P., Deeudom M., Chokesajjawatee N., Santiyanont P., Tadee P., Nuangmek A., Tadee P., Sheppard S.K., Pascoe B., et al. Core genome sequence analysis to characterize Salmonella enterica serovar Rissen ST469 from a swine production chain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;304:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elbediwi M., Pan H., Jiang Z., Biswas S., Li Y., Yue M. Genomic Characterization of mcr-1-carrying Salmonella enterica Serovar 4,[5],12:i:-ST 34 Clone Isolated From Pigs in China. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8:663. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elbediwi M., Pan H., Biswas S., Li Y., Yue M. Emerging colistin resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Newport isolates from human infections. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:535–538. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1733439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paudyal N., Pan H., Elbediwi M., Zhou X., Peng X., Li X., Fang W., Yue M. Characterization of Salmonella Dublin isolated from bovine and human hosts. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:226. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1598-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paudyal N., Pan H., Wu B., Zhou X., Zhou X., Chai W., Wu Q., Li S., Li F., Gu G., et al. Persistent Asymptomatic Human Infections by Salmonella enterica Serovar Newport in China. mSphere. 2020;5:e00163-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00163-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elbediwi M., Li Y., Paudyal N., Pan H., Li X., Xie S., Rajkovic A., Feng Y., Fang W., Rankin S.C., et al. Global Burden of Colistin-Resistant Bacteria: Mobilized Colistin Resistance Genes Study (1980–2018) Microorganisms. 2019;7:461. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7100461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwu C.J., Iweriebor B.C., Obi L.C., Basson A.K., Okoh A.I. Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Isolates from Swine in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J. Food Prot. 2016;79:1234–1239. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Exner M., Bhattacharya S., Christiansen B., Gebel J., Goroncy-Bermes P., Hartemann P., Heeg P., Ilschner C., Kramer A., Larson E., et al. Antibiotic resistance: What is so special about multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria? GMS Hyg. Infect. Control. 2017;12:Doc05. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Hello S., Hendriksen R.S., Doublet B., Fisher I., Nielsen E.M., Whichard J.M., Bouchrif B., Fashae K., Granier S.A., Jourdan-Da Silva N., et al. International spread of an epidemic population of Salmonella enterica serotype Kentucky ST198 resistant to ciprofloxacin. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;204:675–684. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Y., Zhou X., Jiang Z., Qi Y., Ed-Dra A., Yue M. Epidemiological investigation and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolated from breeder chicken hatcheries in Henan, China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:497. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X., Biswas S., Paudyal N., Pan H., Li X., Fang W., Yue M. Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium Isolates Recovered From the Food Chain Through National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System Between 1996 and 2016. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:985. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yue M., Song H., Bai L. Call for Special Issue Papers: Food Safety in China: Current Practices and Future Needs. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2020;17:471. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2020.29013.cfp4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.OIE . In: Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals 2018 in Salmonellosis. Hymann E.C., Poppe C., editors. World Organization for Animal Health; Paris, France: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu C., Yue M., Rankin S., Weill F.X., Frey J., Schifferli D.M. One-Step Identification of Five Prominent Chicken Salmonella Serovars and Biotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:3881–3883. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01976-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popoff M.Y., Le Minor L. Antigenic Formulas of the Salmonella Serovars. 8th ed. Institute Pasteur; Paris, France: 2001. WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas S., Elbediwi M., Gu G., Yue M. Genomic Characterization of New Variant of Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S)-Producing Escherichia coli with Multidrug Resistance Properties Carrying the mcr-1 Gene in China dagger. Antibiotics. 2020;9:80. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu H., Elbediwi M., Zhou X., Shuai H., Lou X., Wang H., Li Y., Yue M. Epidemiological and Genomic Characterization of Campylobacter jejuni Isolates from a Foodborne Outbreak at Hangzhou, China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3001. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X., Chen Y., Pan H., Pang Z., Li F., Peng X., Ed-Dra A., Li Y., Yue M. Genomic characterization of Salmonella Uzaramo for human invasive infection. Microb. Genom. 2020;6 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antipov D., Hartwick N., Shen M., Raiko M., Lapidus A., Pevzner P.A. plasmidSPAdes: Assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3380–3387. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higa J. Outbreak of Salmonella Rissen Associated with Ground White Pepper: The Epi Investigation. [(accessed on 20 June 2020)];2011 Available online: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/DFDRS/Documents/QSS_Presentation_SRissen_and_%20white%20pepper_010611.pdf.

- 33.Hendriksen R., Bangtrakulnonth A., Pulsrikarn C., Pornreongwong S., Hasman H., Song S., Aarestrup F. Antimicrobial Resistance and Molecular Epidemiology of Salmonella Rissen from Animals, Food Products, and Patients in Thailand and Denmark. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2008;5:605–619. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2007.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvine N. Communicable Diseases Monthly Report, Northern Ireland Edition. The Health Protection Agency. [(accessed on 20 June 2020)];2009 Available online: http://www.publichealth.hscni.net/directorate-public-health/health-protection/surveillance-data.

- 35.Giovannini A., Prencipe V., Conte A., Marino L., Petrini A., Pomilio F., Rizzi V., Migliorati G. Quantitative risk assessment of Salmonella spp. infection for the consumer of pork products in an Italian region. Food Control. 2004;15:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(03)00025-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mürmann L., Santos M., Cardoso M. Prevalence, genetic characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella isolated from fresh pork sausages in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Food Control. 2009;20:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pires S.M., Vieira A.R., Hald T., Cole D. Source attribution of human salmonellosis: An overview of methods and estimates. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014;11:667–676. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynne A., Foley S., Han J. Salmonella: Properties and Occurrence. Encycl. Food Health. 2016 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00608-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y., Liu C., Zhang Z., Hu Y., Cao C., Wang X., Xi M., Xia X., Yang B., Meng J. Distribution and Molecular Characterization of Salmonella enterica Hypermutators in Retail Food in China. J. Food Prot. 2015;78:1481–1487. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White D.G., Zhao S., Sudler R., Ayers S., Friedman S., Chen S., McDermott P.F., McDermott S., Wagner D.D., Meng J. The isolation of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella from retail ground meats. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1147–1154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L., Fu Y., Xiong Z., Ma Y., Wei Y., Qu X., Zhang H., Zhang J., Liao M. Highly Prevalent Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella From Chicken and Pork Meat at Retail Markets in Guangdong, China. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2104. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H., Paruch L., Chen X., van Eerde A., Skomedal H., Wang Y., Liu D., Liu Clarke J. Antibiotic Application and Resistance in Swine Production in China: Current Situation and Future Perspectives. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019;6:136. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bai L., Hurley D., Li J., Meng Q., Wang J., Fanning S., Xiong Y. Characterisation of multidrug-resistant Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli cultured from pigs in China: Co-occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and mcr-1-encoding genes on plasmids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2016;48:445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arguello H., Alvarez-Ordonez A., Carvajal A., Rubio P., Prieto M. Role of slaughtering in Salmonella spreading and control in pork production. J. Food Prot. 2013;76:899–911. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caleja C., de Toro M., Gonçalves A., Themudo P., Vieira-Pinto M., Monteiro D., Rodrigues J., Sáenz Y., Carvalho C., Igrejas G., et al. Antimicrobial resistance and class I integrons in Salmonella enterica isolates from wild boars and Bísaro pigs. Int. Microbiol. 2011;14:19–24. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao X., Ye C., Chang W., Sun S. Serotype Distribution, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Class 1 Integrons Profiles of Salmonella from Animals in Slaughterhouses in Shandong Province, China. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1049. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su J.-H., Zhu Y.-H., Ren T.-Y., Guo L., Yang G.-Y., Jiao L.-G., Wang J.-F. Distribution and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella Isolated from Pigs with Diarrhea in China. Microorganisms. 2018;6:117. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms6040117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riaño I., Moreno M.A., Teshager T., Sáenz Y., Domínguez L., Torres C. Detection and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Salmonella enterica strains of healthy food animals in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58:844–847. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Astorga Márquez R., Salaberria A., García A., Valdezate S., Carbonero A., García A., Arenas A. Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella Strains Isolated from Slaughtered Pigs in Spain. J. Food Prot. 2007;70:1502–1506. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.6.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li R., Xie M., Zhang J., Yang Z., Liu L., Liu X., Zheng Z., Chan E.W., Chen S. Genetic characterization of mcr-1-bearing plasmids to depict molecular mechanisms underlying dissemination of the colistin resistance determinant. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:393–401. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.García-Feliz C., Collazos J.A., Carvajal A., Vidal A., Aladueña A., Ramiro R., de la Fuente del Moral F., Echeita M.A., Rubio P. Salmonella enterica Infections in Spanish Swine Fattening Units. Zoonoses Public Health. 2007;54:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2007.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pornsukarom S., Patchanee P., Erdman M., Cray P., Wittum T., Lee J., Gebreyes W. Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analyses of Salmonella Rissen that Originated from Food Animals in Thailand and United States. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014;62:151–158. doi: 10.1111/zph.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tadee P., Boonkhot P., Pornruangwong S., Patchanee P. Comparative phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Salmonella spp. in pig farms and slaughterhouses in two provinces in northern Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.García-Fierro R., Montero I., Bances M., González-Hevia M.Á., Rodicio M.R. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance and Molecular Typing of Salmonella enterica Serovar Rissen from Different Sources. Microb. Drug Resist. 2015;22:211–217. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;303:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frech G., Schwarz S. Molecular analysis of tetracycline resistance in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Enteritidis, Dublin, Choleraesuis, Hadar and Saintpaul: Construction and application of specific gene probes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;89:633–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frye J.G., Jackson C.R. Genetic mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance identified in Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, and Enteroccocus spp. isolated from U.S. food animals. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:135. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Toro M., Sáenz Y., Cercenado E., Rojo-Bezares B., García-Campello M., Undabeitia E., Torres C. Genetic characterization of the mechanisms of resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate and third-generation cephalosporins in Salmonella enterica from three Spanish hospitals. Int. Microbiol. 2011;14:173–181. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eguale T., Birungi J., Asrat D., Njahira M.N., Njuguna J., Gebreyes W.A., Gunn J.S., Djikeng A., Engidawork E. Genetic markers associated with resistance to beta-lactam and quinolone antimicrobials in non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from humans and animals in central Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017;6:13. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.García V., Vázquez X., Bances M., Herrera-León L., Herrera-León S., Rodicio M.R. Molecular Characterization of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis, Genetic Basis of Antimicrobial Drug Resistance and Plasmid Diversity in Ampicillin-Resistant Isolates. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018;25:219–226. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramirez M.S., Tolmasky M.E. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updates. 2010;13:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang N., Yang X., Jiao S., Zhang J., Ye B., Gao S. Sulfonamide-Resistant Bacteria and Their Resistance Genes in Soils Fertilized with Manures from Jiangsu Province, Southeastern China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Antunes P., Machado J., Peixe L. Dissemination of sul3-containing elements linked to class 1 integrons with an unusual 3’ conserved sequence region among Salmonella isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1545–1548. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang W., Peng Z., Baloch Z., Hu Y., Xu J., Zhang W., Fanning S., Li F. Genomic characterization of an extensively-drug resistance Salmonella enterica serotype Indiana strain harboring bla(NDM-1) gene isolated from a chicken carcass in China. Microbiol. Res. 2017;204:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El-Sharkawy H., Tahoun A., El-Gohary A.E.-G.A., El-Abasy M., El-Khayat F., Gillespie T., Kitade Y., Hafez H.M., Neubauer H., El-Adawy H. Epidemiological, molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from chicken farms in Egypt. Gut Pathog. 2017;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krauland M., Harrison L., Paterson D., Marsh J. Novel integron gene cassette arrays identified in a global collection of multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica. Curr. Microbiol. 2010;60:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9527-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miko A., Pries K., Schroeter A., Helmuth R. Molecular mechanisms of resistance in multidrug-resistant serovars of Salmonella enterica isolated from foods in Germany. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:1025–1033. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonardi S., Bruini I., Alpigiani I., Vismarra A., Barilli E., Brindani F., Morganti M., Bellotti P., Bolzoni L., Pongolini S. Influence of Pigskin on Salmonella Contamination of Pig Carcasses and Cutting Lines in an Italian Slaughterhouse. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2016;5:5654. doi: 10.4081/ijfs.2016.5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Antunes P., Machado J., Peixe L. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and class 1 and 2 integrons in Salmonella enterica isolates from different sources in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58:297–304. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clemente L., Manageiro V., Ferreira E., Jones-Dias D., Correia I., Themudo P., Albuquerque T., Caniça M. Occurrence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases among isolates of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica from food-producing animals and food products, in Portugal. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;167:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Antunes P., Mourão J., Pestana N., Peixe L. Leakage of emerging clinically relevant multidrug-resistant Salmonella clones from pig farms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:2028–2032. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sinwat N., Angkittitrakul S., Coulson K.F., Pilapil F., Meunsene D., Chuanchuen R. High prevalence and molecular characteristics of multidrug-resistant Salmonella in pigs, pork and humans in Thailand and Laos provinces. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016;65:1182–1193. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maurer J., Martin G., Hernandez S., Cheng Y., Gerner-Smidt P., Hise K., D’Angelo M., Cole D., Sanchez S., Madden M., et al. Diversity and Persistence of Salmonella enterica Strains in Rural Landscapes in the Southeastern United States. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0128937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martinez-Urtaza J., Liebana E. Investigation of clonal distribution and persistence of Salmonella Senftenberg in the marine environment and identification of potential sources of contamination. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005;52:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Biswas S., Raoult D., Rolain J.M. A bioinformatic approach to understanding antibiotic resistance in intracellular bacteria through whole genome analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2008;32:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Samosornsuk S. Significant increase in antibiotic resistance of Salmonella isolates from human beings and chicken meat in Thailand. Vet. Microbiol. 1998;62:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tian-Grim S. Susceptibility patterns of clinical bacterial isolates in nineteen selected hospitals in Thailand. J. Med Assoc. Thail. = Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 1994;77:298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Isenbarger D.W., Hoge C.W., Srijan A., Pitarangsi C., Vithayasai N., Bodhidatta L., Hickey K.W., Cam P.D. Comparative antibiotic resistance of diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996–1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:175–180. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]