Abstract

Background

Actinomyces oris is an early colonizer and has two types of fimbriae on its cell surface, type 1 fimbriae (FimP and FimQ) and type 2 fimbriae (FimA and FimB), which contribute to the attachment and coaggregation with other bacteria and the formation of biofilm on the tooth surface, respectively. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are metabolic products of oral bacteria including A. oris and regulate pH in dental plaques. To clarify the relationship between SCFAs and fimbrillins, effects of SCFAs on the initial attachment and colonization (INAC) assay using A. oris wild type and fimbriae mutants was investigated. INAC assays using A. oris MG1 strain cells were performed with SCFAs (acetic, butyric, propionic, valeric and lactic acids) or a mixture of them on human saliva-coated 6-well plates incubated in TSB with 0.25% sucrose for 1 h. The INAC was assessed by staining live and dead cells that were visualized with a confocal microscope.

Results

Among the SCFAs, acetic, butyric and propionic acids and a mixture of acetic, butyric and propionic acids induced the type 1 and type 2 fimbriae-dependent and independent INAC by live A. oris, but these cells did not interact with streptococci. The main effects might be dependent on the levels of the non-ionized acid forms of the SCFAs in acidic stress conditions. GroEL was also found to be a contributor to the FimA-independent INAC by live A. oris cells stimulated with non-ionized acid.

Conclusion

SCFAs affect the INAC-associated activities of the A. oris fimbrillins and non-fimbrillins during ionized and non-ionized acid formations in the form of co-culturing with other bacteria in the dental plaque but not impact the interaction of A. oris with streptococci.

Keywords: Biofilm, Initial colonization, Actinomyces oris, Fimbrillin, SCFAs

Background

Initial colonizers such as the oral bacteria Actinomyces spp., Streptococcus spp., Veillonella spp. and Neisseria spp. play important roles in biofilm formation in human oral cavities through their interactions with other bacteria on the tooth surface [1–4]. Biofilm communities on the tooth surface are polymicrobial [5, 6], and more than 60 to 90% of the biofilm bacteria in salivary components that coat the enamel surface are streptococci [7, 8]. Actinomyces spp. aggregate with Streptococcus spp. during the progression of dental caries and contribute to periodontal diseases [9–11]. Actinomyces oris, which was formerly referred to as Actinomyces naeslundii genospecies 2 [7, 12], is considered an initial colonizer that interacts with other bacteria in the oral cavity [13]. A. oris induces the coaggregation of the early colonizers Streptococcus gordonii and Streptococcus sanguinis with the intermediate colonizer Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral biofilms [1].

Human salivary components, such as statherin [14], proline-rich proteins (PRPs) [15, 16], gp-340 [17, 18] and mucin (MUC7) [19, 20], control the attachment and colonization of oral bacteria on the tooth surface [21]. A. naeslundii, which was formerly referred to as genospecies 1, and A. oris bind to PRPs and statherin, a phosphate-containing protein in salivary components [1]. A. oris have two functionally and antigenically distinct types of important fimbriae on the cell surface: type 1 and type 2 fimbriae are formed by the shaft fimbrillins, FimP and FimA, and the tip fimbrillins, FimQ and FimB, respectively [22]. Type 1 fimbriae mediate the attachment to PRPs on the tooth surface [23], and type 2 fimbriae mediate the coaggregation and late biofilm formation with streptococci [24–27].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are secreted by oral bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, F. nucleatum [28, 29] and Veillonella parvula [30]. In healthy human volunteers, the concentrations of acetic, lactic, propionic, formic, butyric and valeric acids among the total SCFAs detected in saliva were found to be 6.0 ± 3.5 mM, 1.2 ± 1.9 mM, 1.0 ± 0.8 mM, 0.5 ± 0.5 mM, 0.3 ± 0.4 mM and 0.05 ± 0.2 mM, respectively [31]. In another report, the maximum concentrations of butyric (8.8 mM), propionic (33.7 mM), acetic (52.6 mM) and formic acids (5.8 mM) were also detected in dental plaques from caries-free and caries-susceptible young subjects [32]. These starved plaque fluid samples predominantly contained butyric, propionic and acetic acids with high pKa values (dissociation constant) of 4.82, 4.87 and 4.76, respectively, and the total concentration of the mixture of all acids was 95.1 mM (94.3%). These acids effectively buffer the pH in the range considered in the study (i.e., pH 6 to 4). In the Stephan curve [33], acid production is just one of many biological processes that occur within human plaques exposed to sugar. The Stephan curve has played a dominant role in caries research over the past several decades. In oral biofilm bacteria, organic acids are mainly generated by the fermentation of sugars during or after the intake of food, including sugar, and reduce the pH to levels lower than 5.0 [34, 35]. However, fresh saliva is produced to neutralize the reduced pH of the biofilm. Constant stimulation by a low pH may affect biofilm bacteria on the tooth surface.

As we have previously reported, the rate of biofilm formation by A. naeslundii X600 cells was upregulated by 6.25 mM butyric acid, 3.13 mM propionic acid and 3.13 mM valeric acid compared to the rate in the control (no SCFA) in human saliva-coated 96-well microtiter plates [36]. When biofilm cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis, the results demonstrated that this upregulation was mediated by the heat shock protein GroEL [36]. Another report showed that the number of biofilms consisting of A. naeslundii X600 cells generated from initial attachment cells in a flow cell system was also increased by treatment with 60 mM butyric acid [37]. These reports suggested that the effects of SCFAs, including butyric acid, might induce the potentiation of the cell status required for initial cell attachment, colonization and biofilm formation [37, 38]. A total SCFA concentration of 60 mM and a low pH (pH 4.7) were required for the initial attachment of and biofilm formation by A. naeslundii [37]. SCFAs generated after the fermentation of sugars in the biofilm may affect the recolonization and spreading of Actinomyces spp. However, the relationship between SCFAs and the fimbrillin-dependent initial attachment of A. oris, which belongs to a different type than A. naeslundii, is not clear. A. oris shows fimbrillin-dependent activities related to cell adherence and aggregation in cocultures of A. oris and streptococci. The effect of SCFAs on cocultures of A. oris and oral streptococci and the relationship between fimbrillin and GroEL are also interesting issues.

In this study, we performed initial attachment and colonization (INAC) assays to determine the relationship between fimbriae and SCFAs in A. oris. We clearly determined that a total SCFA concentration of 60 mM involving acids with high pKa values (butyric, propionic and acetic acids) promoted type 1 (FimP and FimQ) and type 2 (FimA and FimB) fimbrillin-dependent INAC by live A. oris cells. However, the promotion of the FimA-dependent INAC of A. oris by SCFAs did not mediate the interactions of A. oris with S. sanguinis. FimA-independent INAC was associated with GroEL under the stress conditions induced by 60 mM butyric acid treatment. These results provide new evidence regarding the mechanisms of the fimbrillin-dependent and fimbrillin-independent INAC of A. oris on a human saliva-coated surface and the communication of A. oris with the oral bacteria that produce SCFAs.

Results

Effect of SCFAs on the INAC of A. oris

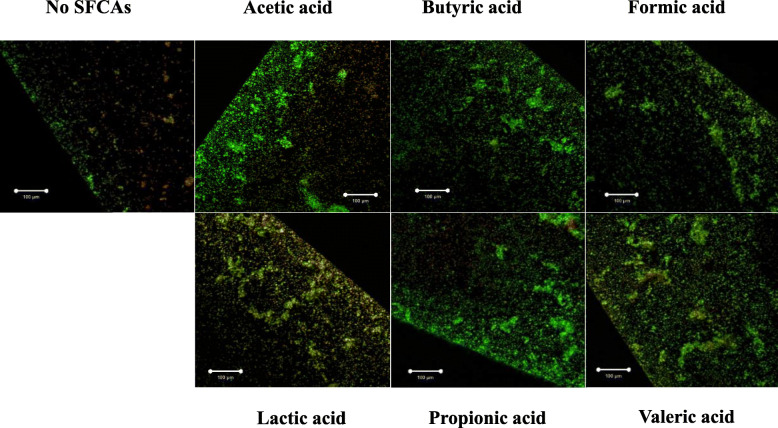

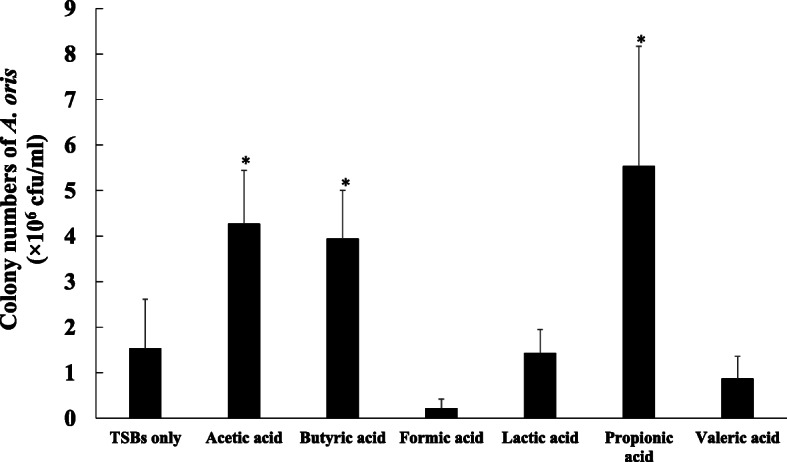

To confirm the effects of butyric acid on the INAC of A. oris, various concentrations of butyric acid were applied, and the dose-dependent effects of the butyric acid on the INAC were visually observed by confocal microscopy (S1 Fig). INAC was stimulated by levels of butyric acid higher than 30 mM (S1 Fig). Compared to the other concentrations, 60 mM butyric acid showed the greatest INAC. Other SCFAs treated at 60 mM concentrations also increased the initial attachment and aggregates of A. oris compared to the control (no SCFA) (Fig. 1). To confirm that the number of bacterial live cells was reflected in the amount of stimulation, the attached cells were removed and added onto BHI agar plates. After the cells were incubated for 48 h, the number of colonies was counted. Treatment with acetic acid, butyric acid or propionic acid significantly increased the number of cells compared to that observed in the no-SCFA control (p-value < 0.05), while the number of cells in the lactic acid and valeric acid treatment groups did not differ from that of the control condition (Fig. 2). Compared to the control, formic acid treatment led to a decreased number of cells. Therefore, the biological activities of acetic, butyric and propionic acids were different from those of formic, lactic and valeric acids.

Fig. 1.

Effect of SCFAs on the initial attachment and colonization of A. oris. A. oris MG1 was cultivated in TSB supplemented with or without 60 mM SCFAs (acetic, butyric, formic, lactic, propionic and valeric acids) for 1 h. The attached and colonized cells were observed at the edges of the wells. INAC was observed by confocal microscopy. Merged images of the live cells (green colour) and dead cells (red colour) are presented in the pictures, in which the effects of butyric acid on INAC were observed. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. Representative data from more than three independent experiments are presented in each panel

Fig. 2.

Number of live A. oris cells that were initially attached and colonized after treatment with SCFAs. A. oris MG1 was cultivated in TSB supplemented with or without 60 mM SCFAs (acetic, butyric, formic, lactic, propionic and valeric acids) for 1 h. The attached and colonized cells were harvested with a scraper, were pipetted, and placed onto BHI agar plates. These cells were counted on BHI agar plates after 48 h. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate experiments. The experiments were performed three times, with similar results obtained in each replicate. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between the two groups (Student’s t-test, p-value < 0.05, no SCFAs vs. SCFAs)

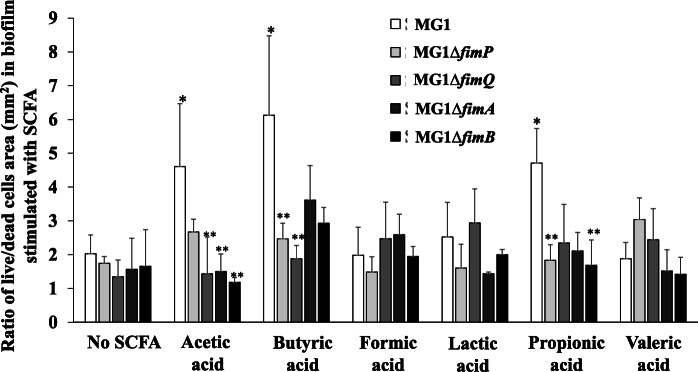

To explore the roles of fimbrillin in the initial attachment of A. oris, MG1 fimbrillin mutants (ΔfimP, ΔfimQ, ΔfimA and ΔfimB) were used in an INAC assay of cells treated with 60 mM SCFAs. The INAC of the fimbrillin-mutant A. oris was visibly increased by stimulation of SCFAs compared with no stimulation, but reduced compared to those of the wild-type MG1 control, which were treated with SCFAs (S2 Fig). In particular, the ΔfimA cells showed poor attachment and colonization. To clear whether live and dead cells are dominantly adhered on the saliva-coated plate surface, the percentages of the areas with live (green colour) and dead cells (red colour) in all the pictures obtained by the CLSM were calculated using ImageJ. The ratios of the live cell areas to the dead cell areas were re-calculated. The ratios were significantly higher in the acetic-, butyric- and propionic acid-treated MG1 cells than in the untreated MG1 cells (p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3). However, the ratios of the live cell areas to the dead cell areas induced by the formic, lactic and valeric acid treatments and the controls were equivalent. The increased initial attachment of A. oris was visually observed in all SCFA-treated wild-type cells (Fig. 1); however, significant increases in the number of attached live cells and the predominance of the live cell areas to the dead cell areas were observed with the acetic, butyric and propionic acid treatments but not with formic, lactic and valeric acid treatments (Figs. 1 and 3). Therefore, the cells that were observed to be initially attached may include more adherence and aggregation of dead cells after formic, lactic or valeric acids treatments than after acetic, butyric or propionic acids treatments. In the fimbrillin mutants, the ratios of the live cells areas to the dead cells were totally reduced as compared with wild-type in acetic, butyric and propionic acids (Fig. 3). With acetic and butyric acid stimulation, the ratios of the live cell areas to the dead cell areas were significantly lower in the ΔfimP, and ΔfimP and ΔfimQ than those in the wild-type strain, respectively (p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3). While the ratios were significantly lower in the ΔfimA and ΔfimB than the wild-type in acetic acid, the differences between the wild-type and mutant strains were not significant after butyric acid treatment. Therefore, type 1 and type 2 fimbrillins were both required for the acetic acid-induced increase in INAC, but type 1 fimbrillin was mainly necessary for the spread of the live cell attachment area in butyric acid. With propionic acid, the ratios of the live cell areas to the dead cell areas were significantly lower in the ΔfimP and ΔfimB than in the wild-type strain (p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3). The ratios were also lower in ΔfimQ and ΔfimA; however, the differences between the wild-type and mutant strains were not significant.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SCFAs on the INAC of the wild-type A. oris and the fimbrillin mutants. The INAC of the wild-type A. oris MG1 and the ΔfimP, ΔfimQ, ΔfimA and ΔfimB mutants were observed under conditions with or without SCFAs. The attached and colonized cells were stained using a LIVE/DEAD staining kit and observed by CLSM at the edges of the wells. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. TSB without SCFAs, TSB with 60 mM acetic acid, TSB with 60 mM butyric acid, TSB with 60 mM formic acid, TSB with 60 mM lactic acid, TSBs with 60 mM propionic acid and TSB with 60 mM valeric acid were used as the media for the INAC assays for the wild-type A. oris MG1 and the MG1 ΔfimA mutant strain. Live and dead cell areas were analysed by ImageJ from CLSM images, and the ratios of the live areas to the dead cell areas were calculated by ImageJ. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between the two groups (Student’s t-test, p-value < 0.05, *: no SCFAs vs. SCFAs, **: MG1 vs. each MG1 mutant)

Effects of low pH and butyric acid on INAC

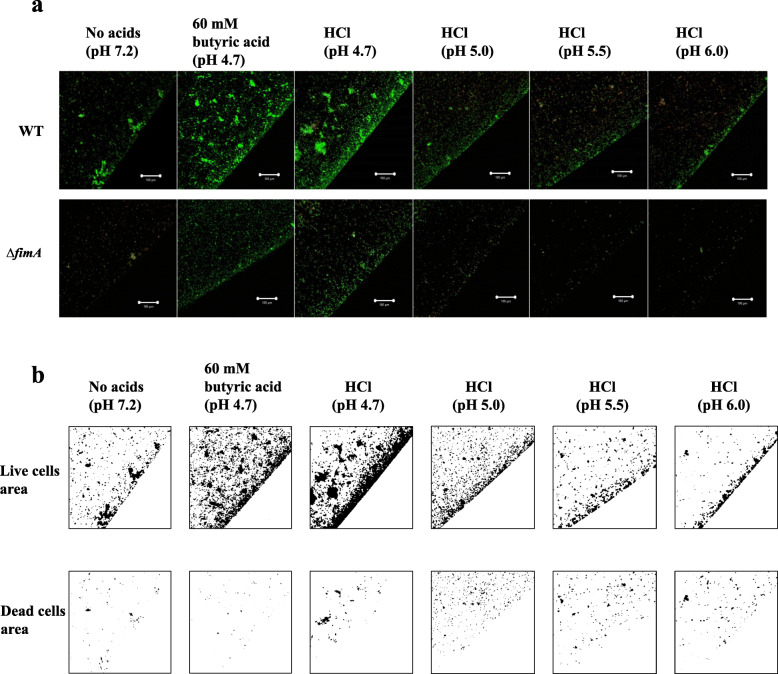

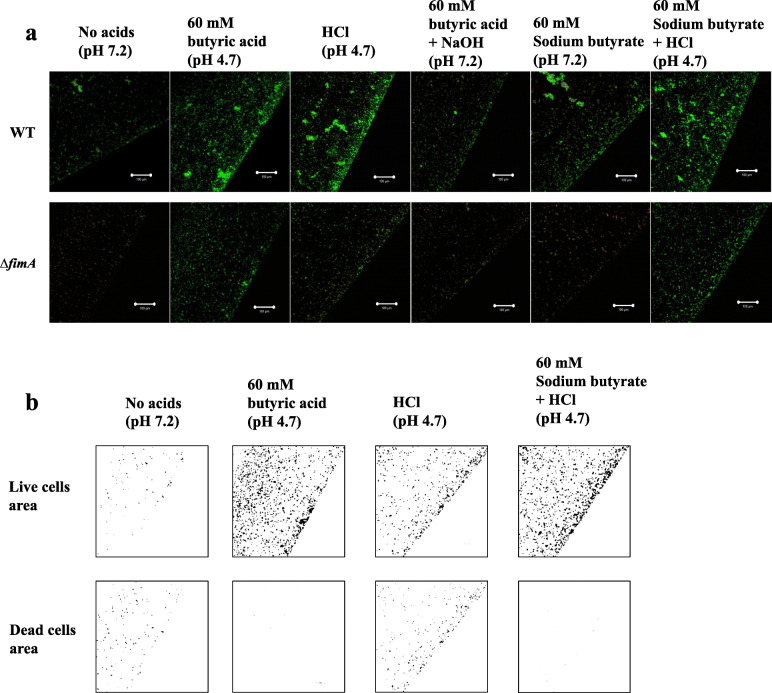

The culture of the TSB supplemented with 60 mM butyric acid had a pH of 4.7 and included both the ionized and non-ionized acid forms because 50% of butyric acid exists in the ionized form and 50% of butyric acid exists in the non-ionized form at pH conditions near pH 4.82 (the pKa for butyric acid). However, the ratio of the non-ionized form to the ionized form is reduced by increasing the pH. Treatment with 60 mM butyric acid induced an increase in the INAC of A. oris compared with the INAC rate induced by concentrations of butyric acid lower than 60 mM (S1 Fig). There is a possibility that an increase in the non-ionized forms affects the INAC at pH 4.7 during the 60 mM butyric acid treatment. Various pH conditions were generated with the strong acid HCl, and these changes resulted in complete conversion to only the ionized form because the pKa was − 8. The effects of these conditions were compared with those of the butyric acid treatment used in the INAC assay. The results showed that the primary pH 4.7 condition set with HCl reduced the INAC of the A. oris MG1 compared with that after 60 mM butyric acid treatment (Fig. 4a). However, the pH 4.7 condition, as prepared with HCl, induced greater INAC than those found with the other high pH conditions (pH 5.0, pH 5.5 and pH 6.0) and with no added acid. In the analyses of the live and dead cell areas of the MG1, the majority of cells were alive after the 60 mM butyric acid treatment under the pH 4.7 condition as prepared with HCl, but more dead cells were also observed under the conditions prepared with HCl than in the conditions created with 60 mM butyric acid or without added acid (Fig. 4b). However, the ionized acid form in the pH 4.7 condition, as prepared with HCl, was associated with positive effects on the INAC of live and dead MG1 cells. In contrast, the fimbriae-dependent INAC by live MG1 cells stimulated with 60 mM butyric acid was mainly associated with the presence of the non-ionized acid form because the pH 4.7 conditions prepared with HCl resulted in the total conversion to the ionized acid form, resulting in an increased number of dead cells. All mutants showed reduction of the INAC ratio of live and dead MG1 cells in acetic, butyric and propionic acids. To clear these mechanisms, we selected ΔfimA and compared with wild-type in various conditions of pH. For the MG1 ΔfimA, the pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl induced greater INAC than did the other pH conditions and the no-acid condition but a lower INAC than the 60 mM butyric acid condition (Fig. 4a). To elucidate the effects of the low pH with butyric acid, a pH 7.2 condition prepared with NaOH in 60 mM butyric acid, a pH 7.2 condition in sodium butyrate, and a pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl in sodium butyrate were evaluated with an INAC assay of the MG1 and MG1ΔfimA. Compared with the 60 mM butyric acid (pH 4.7) condition, the INAC was reduced by the increase in pH (pH 7.2) in the 60 mM butyric acid condition prepared by NaOH, and in contrast, the INAC was increased by the decrease in pH (pH 4.7) in the 60 mM sodium butyrate condition prepared by HCl in the MG1 and MG1ΔfimA (Fig. 5a). The ionized form was relatively increased in the NaOH-mediated pH conditions from 4.7 to 7.2 in 60 mM butyric acid because the ionized form is the main form present in pH conditions above the pKa. In contrast, positive effects on the INAC of the MG1 and MG1ΔfimA were observed when the non-ionized form was increased in the HCl-mediated pH conditions from 7.2 to 4.7 in 60 mM sodium butyrate. In the analyses of the live and dead cell areas of MG1ΔfimA, live cells were primarily observed in the 60 mM butyric acid and pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl in 60 mM sodium butyrate, but more dead cells were also observed under the pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl than those found under the other pH 4.7 conditions prepared with butyric acid and pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl in 60 mM sodium butyrate (Fig. 5a). The results in the pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl in sodium butyrate were similar to those in 60 mM butyric acid. Taken together, these data indicate that the fimbriae-independent INAC by live MG1ΔfimA cells stimulated with 60 mM butyric acid might be primarily associated with the non-ionized acid form.

Fig. 4.

Effects of 60 mM butyric acid and HCl-mediated pH conditions on INAC. a INAC of the wild-type A. oris MG1 and the MG1 ΔfimA mutant was observed in conditions with or without 60 mM butyric acid and at various pH values (pH 4.7, 5.0, 5.5 and 6.0) prepared with HCl. The attached and colonized cells were stained using a LIVE/DEAD staining kit and observed by CLSM at the edges of the wells. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. Images were further analysed to determine the areas of live cells and dead cells in MG1 using ImageJ. b Representative data from more than three independent experiments are presented in each panel

Fig. 5.

Effects of 60 mM butyric acid with lowered pH on INAC. a INAC of the wild-type A. oris MG1 and the MG1 ΔfimA mutant strains were observed under the control condition, 60 mM butyric acid condition, pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl, pH 7.2 condition prepared with NaOH, 60 mM sodium butyrate condition and pH 4.7 condition with 60 mM sodium butyrate prepared with HCl. The attached and colonized cells were stained using a LIVE/DEAD staining kit and observed by CLSM at the edges of the wells. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. b Images were further analysed to determine the areas of live cells and dead cells in MGΔfimA using ImageJ. Representative data from more than three independent experiments are presented in each panel

Effects of the mixture of acetic, butyric and propionic acids on INAC

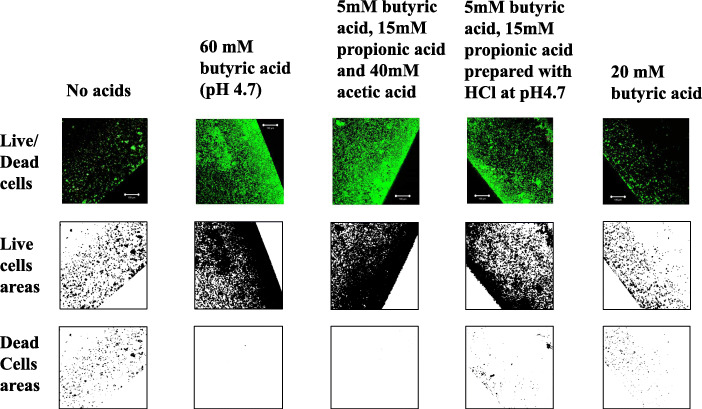

Common properties include the presence of 50% of the non-ionized forms in 60 mM acetic, 60 mM butyric and 60 mM propionic acids. Therefore, each non-ionized acid may have the same effects on the INAC of A. oris. In dental plaques, acetic, propionic and butyric acids are mixed and the mix acids may affect biofilm formation [31]. To confirm the effects of the mixture of butyric, propionic and acetic acids on INAC, 5 mM butyric acid, 15 mM propionic acid and 40 mM acetic acid, as referenced in a clinical data from a previous paper [32] and active level of concentration of each acid in this study, were used to prepare a total sample of mixed SCFAs of 60 mM and to apply in the INAC assay. The findings indicated that this mixture, as well as 60 mM butyric acid, induced extremely large INAC areas of live A. oris MG1 and MG1ΔfimA cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, the INAC areas of A. oris MG1 and MG1ΔfimA dead cells were low for both the 60 mM and the full mixture. To observe whether a total of 60 mM of high pKa acids (acetic, butyric and propionic acids) was necessary to induce the INAC areas, a pH 4.7 condition prepared by HCl (treatments with low pKa acids instead of acetic acid) in a mixture of 5 mM butyric acid and 15 mM propionic acid were assessed with the INAC assay, and the results were compared with those of the full mixture of high pKa acids. The INAC areas of the live A. oris MG1 and MG1ΔfimA cells were decreased in the pH 4.7 condition prepared by HCl in a mixture of 5 mM butyric acid and 15 mM propionic acid compared with the full mixture (Fig. 6). In contrast, the INAC areas of the A. oris MG1 and MG1ΔfimA with dead cells were increased in the pH 4.7 condition prepared by HCl in a mixture of 5 mM butyric acid and 15 mM propionic acid compared with the full mixture. These findings indicate that use of HCl instead of acetic acid led to decreased and increased INAC areas of live cells and dead cells, respectively. Twenty mM butyric acid (pH 6.1) induced slightly smaller INAC areas of A. oris wild-type and MG1ΔfimA consisting of live cells and dead cells than did the control condition of no acid. This indicated that pH was higher in 20 mM butyric acid than 60 mM (pH 4.7) and not enough for the stimulation to the induction of INAC cells.

Fig. 6.

Effects of a mixture of acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid on INAC. INAC areas of wild-type A. oris MG1 and MG1 ΔfimA by live cells and with dead cells were observed in the control, with no acid; with 60 mM butyric acid treatment; mixture of 5 mM butyric acid, 15 mM propionic acid and 40 mM acetic acid treatment; and under the pH 4.7 condition prepared with HCl in mixture of 5 mM butyric acid and 15 mM propionic acid, and 20 mM butyric acid. The attached and colonized cells were stained using a LIVE/DEAD staining kit and were observed by CLSM at the edges of the wells. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. Images were further analysed to determine the live and dead cell areas in MG1 using ImageJ. Representative data from more than three independent experiments are presented in each panel

Effect of SCFAs on INAC and the interactions between A. oris and S. sanguinis

Type 2 fimbriae mediate coaggregation and biofilm formation with other bacteria. Based on the results above, we hypothesized that A. oris FimA would be an important factor in the SCFA-stimulated INAC of A. oris in the presence of S. sanguinis or S. gordonii. To determine whether treatment by individual SCFA at 60 mM would affect the INAC of a culture of A. oris MG1 or MG1 ΔfimA strain mixed with streptococci, we performed INAC assays using A. oris and streptococci. S. salivarius was used for the INAC assay as a control.

A significant increase in INAC was observed in A. oris MG1 and S. sanguinis but not in A. oris MG1 with S. gordonii or S. salivarius (S3 Fig). Co-aggregation of MG1 with S. sanguinis was presented in various areas. In contrast, the INAC was visibly reduced in the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA with S. sanguinis, S. gordonii or S. salivarius compared to the wild-type A. oris MG1 and other streptococci (S4 Fig). The INAC areas of A. oris MG1 and S. sanguinis were clearly reduced by the addition of the SCFAs (S5 Fig). Furthermore, the INAC area of the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA with S. sanguinis was slightly reduced by the addition of SCFAs (S6 Fig). This INAC was also enhanced for the culture of A. oris MG1 mixed with S. sanguinis compared to the monoculture of S. sanguinis (S7 Fig). Moreover, SCFAs clearly inhibited the INAC of a monoculture of S. sanguinis (S7 Fig). However, the INAC area of a culture of the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA mixed with S. sanguinis was slightly increased compared to the monocultures of the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA or S. sanguinis (S7 Fig). These results demonstrate that SCFAs inhibited the INAC of a culture of A. oris mixed with S. sanguinis. We considered that the INAC of S. sanguinis may also be inhibited by SCFAs. In contrast, the INAC of A. oris was enhanced by SCFAs. A. oris FimA interacts with S. sanguinis [26], but this interaction is not induced by SCFAs, according to the INAC assay in this study In addition to FimA, other factors of A. oris may interact with S. sanguinis when the cells are treated with SCFAs.

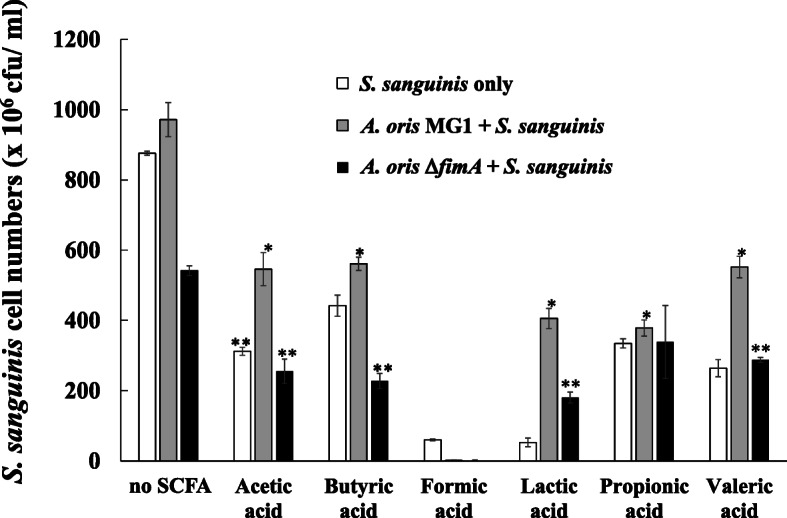

To determine the number of S. sanguinis cells in a monoculture of S. sanguinis and the number in a culture of S. sanguinis mixed with either A. oris MG1 or MG1ΔfimA, in conditions with or without SCFAs, the attached and colonizing cells were removed from the plates using a cell scraper. The cells were suspended in sterile PBS and plated onto mitis-salivarius selective agar plates. The stimulation of acetic, butyric and propionic acids increased CFU of A. oris MG1 (Fig. 1). However, the number of live S. sanguinis cells after the SCFA treatments was significantly lower than that in the control condition (p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 7). However, the number of live S. sanguinis cells in cocultures of A. oris MG1 and S. sanguinis was significantly higher than that in the S. sanguinis monocultures (p-value < 0.05) when cells were treated with acetic acid, butyric acid, lactic acid, propionic acid or valeric acid but not when the cells were treated with formic acid (Fig. 7). In contrast, the number of live S. sanguinis cells was significantly lower in cocultures of A. oris ΔfimA and S. sanguinis than in cocultures of A. oris MG1 and S. sanguinis without SCFA treatment and with butyric acid, lactic acid, or valeric acid treatments (p-value < 0.05) but not with formic acid or propionic acid treatments.

Fig. 7.

Number of S. sanguinis cells in S. sanguinis monocultures and in cultures of S. sanguinis mixed with A. oris MG1 or MG1 ΔfimA. The number of S. sanguinis colonies on mitis-salivarius agar plates was counted in a monoculture of S. sanguinis and in a culture of S. sanguinis mixed with A. oris MG1 or MG1 ΔfimA strains. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate experiments. The experiments were performed three times, with similar results obtained in each replicate. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between the two groups (Student’s t-test, p-value < 0.05, * no SCFA vs. SCFA, ** MG1 vs. MG1.ΔfimA)

Effects of anti-GroEL antibodies on SCFA-stimulated INAC

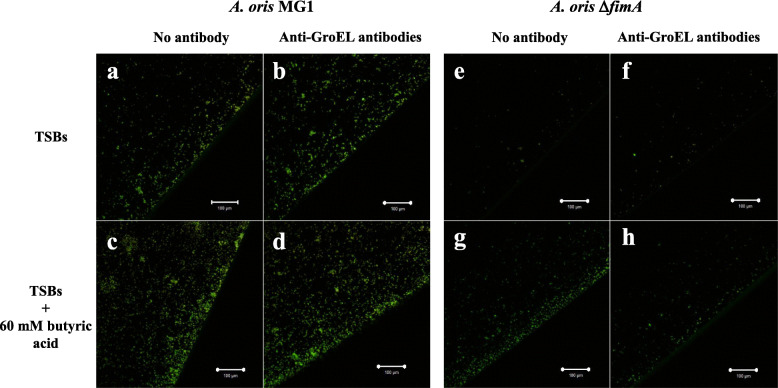

To observe the role of GroEL, which is associated with the initial attachment of A. naeslundii [37], in butyric acid-induced INAC, anti-GroEL antibodies were added to the cultures that were subjected to INAC assay. This antibody could not inhibit the INAC of the A. oris MG1 stimulated with butyric acid (Fig. 8 left). The INAC of A. oris MG1 ΔfimA was slightly enhanced by butyric acid, and this increase was inhibited by the anti-GroEL antibody (Fig. 8 right). Moreover, this increase in INAC was not inhibited by the control antibodies (anti-GBPC polyclonal rabbit antibodies; data not shown). Therefore, GroEL plays a key role in the INAC of the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA strain stimulated with butyric acid.

Fig. 8.

Effects of anti-GroEL antibodies on the INAC of A. oris. TSB only (a, b, e and f) and with 60 mM butyric acid (c, d, g and h) were applied to the cultures for the INAC assays of the wild-type A. oris MG1 and the MG1 ΔfimA strains. Anti-GroEL rabbit antibodies were diluted 1/4000 and applied to the cultures (c, d, g and h). The attached and colonized cells were observed at the edges of the wells. INAC areas were observed by confocal microscopy. Merged images of the live cells (green colour) and dead cells (red colour) are presented in the pictures, in which the effects of butyric acid on the INAC are observed. All CLSM images were obtained with a 10× objective. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. Representative data from more than three independent experiments are presented in each panel

Discussion

The 60 mM butyric acid, 60 mM propionic acid and 60 mM acetic acid treatments resulted in larger numbers of live A. oris cells and larger areas of type 1- and type 2-dependent INAC than those involving the other SCFAs. These acids are anionic acids with high pKa values and act as effective buffers during the production of organic acids, including those with low pKa values (e.g., lactic acid) [39]. The concentrations of butyric and propionic acids have been significantly associated with clinical measures of disease severity (e.g., pocket depth, attachment level), inflammation (e.g., subgingival temperature, % of sites bleeding when probed), and the total microbial load (all p-values < 0.05) [28]. Butyric and propionic acids at concentrations of 6.25 mM each promote FimA-dependent biofilm formation, including an increase in dead cells in vitro, as determined by experimental flow cell systems after 48 h [38]. Acids with high pKa values, such as butyric, propionic and acetic acids, may exhibit a specific ability to stimulate the INAC of both A. naeslundii and A. oris when applied at high concentrations (i.e., 60 mM for at least 1 h). Moreover, these SCFAs may mediate the biofilm formation of A. naeslundii and the FimA-dependent biofilm formation of A. oris at low concentrations (i.e., 6.25 mM for 6 h or more under induction with various SCFAs or for 48 h in conditions without these metabolites). Therefore, the combination of a high concentration of SCFAs with a short incubation time or a low concentration of SCFAs with a long incubation time might be the key to stimulating the INAC of Actinomyces spp. Additionally, SCFAs at 60 mM show a pH of 4.7; however, at 6.25 mM SCFAs, additional organic acids are required to achieve a pH of 4.7 after the sugars start fermenting during the long incubation time required for INAC.

Nonionized acids are considered to present high pKa values at pH 4.7, which enables them to induce INAC. The mixture of 5 mM butyric acid, 15 mM propionic acid and 40 mM acetic acid induced similar INAC areas in A. oris MG1 and the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA mutant to those induced by 60 mM butyric acid. According to the Stephan curve, the pH in dental plaques decreases to less than 5.0 after every meal [33], and at least a 60 mM concentration of SCFAs is required to decrease the pH to that level. Therefore, 60 mM (pH 4.7) is a very important threshold because it presents clinical relevance for caries development and the enhancement of A. naeslundii and A. oris colonization. Benevolent organisms such as V. parvula, which is an early colonizer on the tooth surface, might support the INAC of A. oris because it catabolizes lactate produced by streptococci into SCFAs with high pKa values, such as propionic and acetic acids, with a reduced ability to solubilize enamel [30]. Such metabolic cooperation among bacteria is crucial for the establishment of oral biofilms [40]. Taken together, these results indicate that nonionized acids in the mixture of SCFAs (such as those with high pKa values) exuded from the biofilm as the pH reaches 4.7 will disperse and reinforce biofilm formation by enhancing the new attachment and aggregation of A. naeslundii and A. oris. Moreover, organic acids in the plaque might induce the readhesion and colonization of A. naeslundii and A. oris in the subgingival area and periodontal pocket without streptococci. This scenario is supported by a report that Actinomyces spp. are a prominent component of the periodontal flora [41].

A previous report showed that Bacillus subtilis death results from a change in the intracellular pH caused by the passage of weak organic acids, such as acetic acid, across the cell membrane when incubated with B. subtilis at a pH value near the pKa (4.7) [42]. Weak acids can permeate bacterial membranes more readily than strong acids, such as HCl and lactic acid, because of the equilibrium between their ionized and nonionized forms at the pKa [43]. These nonionized forms pass through the bacterial membrane and induce stress in cells. In contrast, lactic acid cannot undergo conversion to its nonionized form from its ionized form at a pH of 4.7, and although the ionized form affects fimbrillins on the bacterial membrane surface, strong acids cannot pass through the membrane into the intracellular space. The type 1 and type 2 fimbriae-dependent INAC of A. oris MG1 live cells was greatly enhanced by treatment with each SCFA at 60 mM or with a mixture of the SCFAs with high-pKa organic acids (acetic, butyric and propionic acids) at a total concentration of 60 mM. Conditions in which the pH was brought to 4.7 with HCl, in which only the ionized acid form is generated, induced greater INAC of A. oris MG1 live cells together with dead cells than was induced by 60 mM butyric acid. The ionized form present at low pH causes cytoplasmic membrane damage to a major barrier to proton influx [44]. Proteins embedded in cell membranes are exposed to the detrimental effect of the acidic pH at their cellular location and inactivated [45, 46]. Fimbrillin-dependent and fimbrillin-independent INAC in live cells is considered to rely on the effects of nonionized organic acids on the membrane surface of the fimbriae in dental plaques. In contrast, the ionized form induces cell death through membrane damage, resulting in the dead cell-dependent initial adherence and aggregation of A. oris in lower-pH conditions.

As we previously reported, this SCFA-induced increase in biofilm formation by A. naeslundii is dependent on the expression of GroEL, a stress response protein [36]. The INAC of A. naeslundii induced by 60 mM butyric acid is also GroEL-dependent [37]. The INAC of A. oris MG1 ΔfimA cells stimulated with 60 mM butyric acid was inhibited by the anti-GroEL antibody. Therefore, the nonionized acid form of acids with high pKa values may be critical for GroEL-dependent and FimA-independent INAC. According to these results, the mechanism of the INAC of A. naeslundii × 600 might be similar to that of the A. oris MG1 ΔfimA mutant treated with 60 mM butyric acid and may not be dependent on fimbriae.

GroEL is a member of a group of heat shock proteins that includes HrcA, GrpE and DnaK, which are stress-responsive molecular chaperones in bacteria [43, 47, 48]. These proteins control protein misfolding and aggregation and promote protein refolding and proper assembly during conditions of stress [49]. Chaperones and stress response proteins may also act as microbial virulence factors when expressed at the cell surface, functioning as bacterial adhesins and promoting host tissue damage [49]. GroEL is exported outside of cells in membrane vesicles (MVs) [50]. Moreover, GroEL has been identified in MVs isolated from the culture medium of Propionibacterium acnes and Acinetobacter baumannii [51, 52]. In some probiotic lactobacilli, GAPDH, GroEL and DnaK have been identified as surface-associated moonlighting proteins that promote adherence and biofilm formation [53–55]. Under stress conditions, including the presence of butyric acid and propionic acid, MVs containing GroEL may be produced and connect live A. oris cells to solid surfaces.

S. gordonii and S. sanguinis, which are oral streptococci that commonly occur as early colonizers on the tooth surface, communicate with other oral bacteria and contribute to biofilm formation [56, 57]. S. gordonii and S. sanguinis express various antigenic types of cell wall polysaccharides on their cell surfaces. These polysaccharides serve as receptors for the Gal/GalNAc-reactive fimbrial lectin of A. naeslundii [58, 59]. Such interactions between the fimbriae of Actinomyces spp. and the polysaccharides of oral streptococci lead to the initiation of biofilm formation as well as biofilm development in multiple species in vivo and in vitro. However, SCFAs did not affect the interaction between the FimA of A. oris and S. sanguinis and principally induced the INAC of A. oris. Therefore, SCFAs and metabolites from other oral bacteria do not enhance the communication between Actinomyces spp. and oral streptococci such as S. sanguinis, S. gordonii, and S. mitis, which are associated with the development of biofilms.

In conclusion, among SCFAs, butyric acid, propionic acid, acetic acid and a mixture thereof stimulate the type 1- and type 2 fimbrillin-dependent INAC of A. oris live cells. The effects are dependent on the levels of the nonionized forms of weak organic acids. The INAC associated with the interactions of A. oris with oral streptococci [24] is FimA-dependent but is not mediated by SCFAs. The ionized acid form of SCFAs is properly utilized by fimbrillins and dead cells to induce INAC, and the nonionized acid forms that cross the cell membrane cause cell stress and increase the INAC of live cells. GroEL was also found to be a contributor to the FimA-independent INAC of live A. oris cells stimulated by nonionized acid. These results provide new mechanisms of fimbrillin-dependent and fimbrillin-independent INAC without physical interaction with oral streptococci in the communication between A. oris and the oral biofilm bacteria that produce SCFAs. However, our study does not fully elucidate the causal molecules involved, and further study of the molecular functions of fimbrillins, ionized and nonionized SCFA forms, and GroEL expression is necessary to understand the INAC of A. oris. Clinical studies using materials to trap these organic acids are also required to advance oral hygiene to the next level.

Conclusions

Among the SCFAs, weak organic acids: butyric acid, propionic acid, and acetic acid, which are produced in dental plaque, stimulate the type 1- and type 2 fimbrillin-dependent INAC of A. oris live cells. The effects are dependent on the levels of the non-ionized acid forms. The INAC associated with the interactions of A. oris with S. sanguinis or S. gordonii is FimA-dependent but is not mediated by the SCFAs. GroEL was also found to be a contributor to the FimA-independent INAC by live A. oris cells stimulated with non-ionized acid. These results provide new mechanisms for fimbrillin-dependent and fimbrillin -independent INAC in the communication of A. oris and the oral biofilm bacteria that produce SCFAs.

Methods

Human saliva collection

Un-stimulated human saliva samples were collected from 3 healthy volunteers (22 ~ 27 years old) and pooled into sterile bottle over a period of 5 min. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were transferred into new sterile tubes and sterilized by a 0.22-μm Millex-GP filter (Merck Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The sterilized human saliva samples were stored at − 20 °C until use.

INAC assays with monocultures or cocultures

The INAC of monocultures of the A. oris MG1 strain, MG1 fimbriae deletion mutants (ΔfimP, ΔfimQ, ΔfimA and ΔfimB) (Table 1) and streptococci (Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC10556, Streptococcus gordonii ATCC10558 and Streptococcus salivarius HT9R) and that of cocultures of A. oris MG1 or MG1 fimbriae deletion mutants with streptococci was assayed using the methods described in Arai et al. [37] with some modifications. First, the bacterial cultures of A. oris MG1 or MG1 fimbriae deletion mutants were washed with sterile PBS. Before the inoculation of the bacteria, 6-well culture plates (IWAKI Microplate; AGC, Tokyo, Japan) were coated with whole human saliva at 4 °C overnight and washed with sterile PBS. Each strain of bacteria was diluted with fresh Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), and the concentrations of the bacterial cells were then adjusted to an optical density of 0.4 at 600 nm using fresh TSB with 0.25% sucrose. Then, 350 μl of the A. oris MG1 or fimbriae deletion mutant dilutions was mixed into 2,650 μl of TSB with 0.25% sucrose, and this mixture was applied to the human saliva-coated six-well culture plate. After preincubation at 37 °C for 3 h in an aerobic atmosphere, the bacterial cultures were removed, and the bottom of each well was gently washed with sterile PBS to remove the unattached cells. Incubation times greater than 3 h were not selected because the metabolic products present after incubation might affect colonization and biofilm formation. A concentration of at least 60 mM was required to achieve a low pH of 4.7 under the experimental conditions, and this concentration was selected as the test concentration of SCFAs because it is a key criterion for initial attachment and biofilm formation [37]. TSB with or without 60 mM SCFAs, 60 mM butyrate and 60 mM butyrate prepared with HCl at pH 4.7, 60 mM butyric acid prepared with NaOH at pH 7.2 or a mixture of 5 mM butyric acid, 15 mM propionic acid and 40 mM acetic acid was applied, and the cells were incubated for up to 1 h at 37 °C. After this incubation period, the bacterial cultures were removed and gently washed again with sterile PBS. The attached cells at the edge and bottom of the wells were stained with a FilmTracer LIVE/DEAD biofilm viability kit (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) with final concentrations of 5 μM SYTO 9 and 30 μM propidium iodide. In a previous report [37], it was found that the bacteria were likely to physically adhere to and aggregate on the edge of the well after 3 h of incubation, and after removing planktonic cells by washing with PBS, the bacteria around the edge remained. The stained cells on the edge were observed with a confocal microscope {LSM 700 Meta NLO confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM); Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY}. The confocal images of INAC were visually observed using ZEN analysis software (Carl Zeiss). To calculate the percentages of the live and dead cell areas, triplicate assays were performed under each condition, and a typical image was selected from 3 images obtained with a confocal microscope. Three independent experiments were performed, and the 3 typical images of the initially attached cells from 3 independent experiments were analyzed using ImageJ 1.48 software.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strains | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| A. oris MG1 | Type strain, possesses type 1 and 2 fimbriae | Wu et al., 2011 [23] |

| A. oris ΔfimP | Mutant of shaft fimbrillin of type 1 | Mishra et al., 2010 [24] |

| A. oris ΔfimQ | Mutant of tip fimbrillin of type 1 | Mishra et al., 2010 [24] |

| A. oris ΔfimA | Mutant of shaft fimbrillin of type 2 | Wu et al., 2011 [23] |

| A. oris ΔfimB | Mutant of tip fimbrillin of type 2 | Wu et al., 2011 [23] |

To determine the mechanism of the attachment and colonization of A. oris MG1 and MG1 ΔfimA, we added anti-GroEL polyclonal rabbit antibodies (diluted 1/4000; MBL: Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) to the first preincubation medium for 3 h and to the second culture medium with SCFAs for 1 h [37]. An anti-glucan-binding protein C (GBPC) polyclonal rabbit antibody was used as a control [36]. The effects of the antibodies and FruA were assessed by staining the cells with the FilmTracer LIVE/DEAD biofilm viability kit and through visual observation using a CLSM.

Counting of viable cell numbers in the initially attached and colonized cell cultures

Following the same cell preparation as used for the INAC assays, TSB with or without 60 mM SCFAs was applied, and the A. oris MG1 was incubated for as long as 4 h (pre-incubation for 3 h and incubation with SCFAs for 1 h) at 37 °C. After incubation, the bacterial cultures were removed, and the attached cells were gently rewashed with sterile PBS. The attached cells were then removed using a cell scraper (Sumitomo Bakelite Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and collected by pipetting them into a centrifugation tube. After washing with sterile PBS, the cells were diluted with sterile PBS and poured onto BHI agar plates. After 48 h of incubation in an aerobic atmosphere, the number of colonies was counted.

Statistical analysis

The comparisons of biofilm areas and percentages of live and dead cell areas between two groups were performed using Student’s t-tests, with statistical significance defined as a p-value < 0.05. Data were analysed with Microsoft Excel and SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics 24; IBM corporation, Armonk, NY).

Data availability statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank American Journal Experts (https://www.aje.com) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids

- INAC

Initial attachment and colonization

- PRPs

Proline-rich proteins

- CLSM

Confocal laser scanning microscope

- GBPC

Glucan binding protein C

- BHI

Brain heart infusion broth

Authors’ contributions

HS developed the initial idea of the study. HS and TS were involved in the study and design. IS performed the research. HS and IS wrote the manuscript. HS and IS performed the data analysis. The research plan for this project was conceived based on several rounds of discussions among all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for the Development of Scientific Research (16 K11537) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), and the Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (40105502). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the MEXT and the AMED in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of National Institute of Infectious Diseases for usage human saliva in coating plate (IRB approval number: 397). Prior to enrolment, written informed consent was obtained from each subject based on the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12866-020-01976-4.

References

- 1.Kolenbrander PE, Palmer RJ, Jr, Periasamy S, Jakubovics NS. Oral multispecies biofilm development and the key role of cell–cell distance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:471–480. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Ahmad A, Wunder A, Auschill TM, Follo M, Braun G, Hellwig E, et al. The in vivo dynamics of Streptococcus spp., Actinomyces naeslundii, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Veillonella spp. in dental plaque biofilm as analysed by five-colour multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:681–687. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz PI, Chalmers NI, Rickard AH, Kong C, Milburn CL, Palmer RJ, Jr, et al. Molecular characterization of subject-specific oral microflora during initial colonization of enamel. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2837–2848. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2837-2848.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Helmerhorst EJ, Leone CW, Troxler RF, Yaskell T, Haffajee AD, et al. Identification of early microbial colonizers in human dental biofilm. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1311–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalmers NI, Palmer RJ, Jr, Cisar JO, Kolenbrander PE. Characterization of a Streptococcus sp.-Veillonella sp. community micromanipulated from dental plaque. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:8145–8154. doi: 10.1128/JB.00983-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer RJ, Jr, Gordon SM, Cisar JO, Kolenbrander PE. Coaggregation-mediated interactions of streptococci and actinomyces detected in initial human dental plaque. J Bacteriol. 2003;85:3400–3409. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3400-3409.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paddick JS, Brailsford SR, Kidd EA, Gilbert SC, Clark DT, Alam S, et al. Effect of the environment on genotypic diversity of Actinomyces naeslundii and Streptococcus oralis in the oral biofilm. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:6475–6480. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6475-6480.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyvad B, Kilian M. Microbiology of the early colonization of human enamel and root surfaces in vivo. Scand J Dent Res. 1987;95:369–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1987.tb01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burne RA. Oral streptococci... products of their environment. J Dent Res. 1998;77:445–452. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desaymard C, Ivanyi L. Comparison of in vitro immunogenicity, tolerogenicity and mitogenicity of dinitrophenyl-Levan conjugates with varying epitope density. Immunology. 1976;30:647–653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shilo M, Wolman B. Activities of bacterial levans and of lipopolysaccharides in the processes of inflammation and infection. Br J Exp Pathol. 1958;39:652–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henssge U, Do T, Gilbert SC, Cox S, Clark D, Wickström C, et al. Application of MLST and pilus gene sequence comparisons to investigate the population structures of Actinomyces naeslundii and Actinomyces oris. PLoS One. 2009;6:e21430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung MK, Ragsdale PA. Synthesis and function of Actinomyces naeslundii T14V type 1 fimbriae require the expression of additional fimbria-associated genes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2629–2639. doi: 10.1128/IAI.65.7.2629-2639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons RJ, Hay DI, Cisar JO, Clark WB. Adsorbed salivary proline-rich protein 1 and statherin: receptors for type 1 fimbriae of Actinomyces viscosus T14V-J1 on apatitic surfaces. Infect Immun. 1998;56:2990–2993. doi: 10.1128/IAI.56.11.2990-2993.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li T, Khah MK, Slavnic S, Johansson I, Strömberg N. Different type 1 fimbrial genes and tropisms of commensal and potentially pathogenic Actinomyces spp. with different salivary acidic proline-rich protein and statherin ligand specificities. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7224–7233. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7224-7233.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay DI, Ahern JM, Schluckebier SK, Schlesinger DH. Human salivary acidic proline-rich protein polymorphisms and biosynthesis studied by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1717–1726. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730110701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ericson T, Rundegren J. Characterization of a salivary agglutinin reacting with a serotype c strain of Streptococcus mutans. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakobphol A, Xu F, Hoang VM, Larsson T, Bergstrom J, Johansson I, et al. Salivary agglutinin, which binds Streptococcus mutans and Helicobacter pylori, is the lung scavenger receptor cysteine-rich protein gp-340. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39860–39866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobek LA, Situ H. MUC7 20-Mer: investigation of antimicrobial activity, secondary structure, and possible mechanism of antifungal action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:643–652. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.643-652.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Rayment SA, Gyurko C, Oppenheim FG, Offner GD, et al. The recombinant N-terminal region of human salivary mucin MG2 (MUC7) contains a binding domain for oral Streptococci and exhibits candidacidal activity. Biochem J. 2000;345:557–564. doi: 10.1042/bj3450557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamkin MS, Oppenheim FG. Structural features of salivary function. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:251–259. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra A, Das A, Cisar JO, Ton-That H. Sortase-catalyzed assembly of distinct heteromeric fimbriae in Actinomyces naeslundii. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3156–3165. doi: 10.1128/JB.01952-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu C, Mishra A, Yang J, Cisar JO, Das A, et al. Dual function of a tip fimbrillin of Actinomyces in fimbrial assembly and receptor binding. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3197–3206. doi: 10.1128/JB.00173-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra A, Wu C, Yang J, Cisar JO, Das A, et al. The type 2 fimbrial shaft FimA mediates co-aggregation with oral streptococci, adherence to red blood cells and biofilm development. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:841–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cisar JO, Sandberg AL, Mergenhagen SE. Lectin-dependent attachment of Actinomyces naeslundii to receptors on epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1984;46:459–464. doi: 10.1128/IAI.46.2.453-458.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cisar JO, Vatter AE, Clark WB, Curl SH, Hurst-Calderone S, Sandberg AL, et al. Mutants of Actinomyces viscosus T14V lacking type 1, type 2, or both types of fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2984–2989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.56.11.2984-2989.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallberg K, Hammarström KJ, Falsen E, Dahlen G, Gibbons R, Hay DI, et al. Actinomyces naeslundii genospecies 1 and 2 express different binding specificities to N-acetyl-β-D-galactosamine, whereas Actinomyces odontolyticus expresses a different binding specificity in colonizing the human mouth. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1988;13:327–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1998.tb00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niederman R, Buyle-Bodin Y, Lu BY, Robinson P, Naleway C. Short-chain carboxylic acid concentration in human gingival crevicular fluid. J Dent Res. 1997;76:575–579. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendyk A, Marino V, Zilm PS, Howe P, Bafold PM. Effect of dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on experimental periodontitis in the mouse. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samaranayake LP. Essential microbiology for dentistry, 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingston; 2002. p. 114.

- 31.Yoo S, Geum-Sun A. Correlation of microorganisms and carboxylic acid in oral cavity. Int J Clin Prev Dent. 2005;11:165–170. doi: 10.15236/ijcpd.2015.11.3.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolis HC, Duckworth JH, Moreno EC. Composition and buffer capacity of pooled starved plaque fluid from caries-free and caries-susceptible individuals. J Dent Res. 1988;67:1476–1482. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowen WH. The Stephan curve revisited. Odontology. 2013;101:2–8. doi: 10.1007/s10266-012-0092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Y, Licandro H, Martin C, Septier C, Zhao M, Neyraud E, et al. The associations between biochemical and microbiological variables and taste differ in whole saliva and in the film lining the tongue. Biomed Res Int. 2018;14:2838052. doi: 10.1155/2018/2838052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dawes C. Why does supragingival calculus form preferentially on the lingual surface of the 6 lower anterior teeth? J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:923–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoneda S, Kawarai T, Narisawa N, Tuna EB, Sato N, Tsugane T, et al. Effects of short-chain fatty acids on Actinomyces naeslundii biofilm formation. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2013;28:354–365. doi: 10.1111/omi.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arai T, Ochiai K, Senpuku H. Actinomyces naeslundii GroEL-dependent initial attachment and biofilm formation in a flow cell system. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;109:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki I, Shimizu T, Senpuku H. Role of SCFAs for fimbrillin-dependent initial colonization and biofilm formation of Actinomyces oris. Microorganisms. 2018;6:114. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms6040114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margolis HC, Moreno EC, Murphy BJ. Importance of high pKA acids in cariogenic potential of plaque. J Dent Res. 1985;64:786–792. doi: 10.1177/00220345850640050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradshaw DJ, Homer KA, Marsh PD, Beighton D. Metabolic cooperation in oral microbial communities during growth on mucin. Microbiology. 1994;140:3407–3412. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplan I, Anavi K, Anavi Y, Calderon S, Schwartz-Arad D. The clinical spectrum of Actinomyces-associated lesions of the oral mucosa and jawbones: correlations with histomorphometric analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asensi V, Parra F, Fierer J, Valle E, Bordallo C, Rendueles P, et al. Bactericidal effect of ADP and acetic acid on Bacillus subtilis. Curr Microbiol. 1997;34:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s002849900145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salmond CV, Kroll RG, Booth IR. The effect of food presentatives on pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2845–2850. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown JL, Ross T, McMeekin TA, Nichols PD. Acid habituation of Escherichia coli and the potential role of cyclopropane fatty acids in low pH tolerance. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;37:163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(97)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilks JC, Slonczewski JL. pH of the cytoplasm and periplasm of Escherichia coli: rapid measurement by green fluorescent protein fluorimetry. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5601–5607. doi: 10.1128/JB.00615-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitko RD, Cleeton RL, Armentrout EI, Lee GE, Noguchi K, Berkmen MB, Jones BD, Slonczewski JL. Cytoplasmic acidification and the benzoate transcriptome in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Checa SK, Viale AM. The 70-kDa heat-shock protein/DnaK chaperone system is required for the productive folding of ribulose-biphosphate carboxylase subunits in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:848–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ciardi JE, McCray GF, Kolenbrander PE, Lau A. Cell-to-cell interaction of Streptococcus sanguis and Propionibacterium acnes on saliva-coated hydroxyapatite. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1441–1446. doi: 10.1128/IAI.55.6.1441-1446.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhandari V, Houry WA. Substrate interaction networks of the Escherichia coli chaperones: trigger factor, DnaK and GroEL. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;883:271–294. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23603-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Nedawi K, Mian MF, Hossain N, Karimi K, Mao YK, Forsythe P, et al. Gut commensal microvesicles reproduce parent bacterial signals to host immune and enteric nervous systems. FASEB J. 2015;29:684–695. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-259721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeon J, Mok HJ, Choi Y, Park SC, Jo H, Her J, et al. Proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles derived from Propionibacterium acnes. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2017;11(1-2):1600040. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Li ZT, Zhang RL, Bi XG, Xu L, Fan M, Xie D, et al. Outer membrane vesicles isolated from two clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strains exhibit different toxicity and proteome characteristics. Microb Pathog. 2015;81:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergonzelli GE, Granato D, Pridmore RD, Marvin-Guy LF, Donnicola D, Hésy-Theulaz IE. GroEL of Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 (NCC 533) is cell surface associated: potential role in interactions with the host and the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 2006;74:425–434. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.425-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kainulainen V, Korhonen TK. Dancing to another tune-adhesive moonlighting proteins in bacteria. Biology (Basel) 2014;3:178–204. doi: 10.3390/biology3010178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rieu A, Aoudia N, Jego G, Chluba J, Yousfi N, Bnandet R, et al. The biofilm mode of life boosts the anti-inflammatory properties of Lactobacillus. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:1836–1853. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito T, Ichinosawa T, Shimizu T. Streptococcal adhesin SspA/B analogue peptide inhibits adherence and impacts biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ge X, Shi X, Shi L, Liu J, Stone V, et al. Involvement of NADH oxidase in biofilm formation in Streptococcus sanguinis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:407–450. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cisar JO, Sandberg AL, Abeygunawardana C, Reddy GP, Bush CA. Lectin recognition of host-like saccharide motifs in streptococcal cell wall polysaccharides. Glycobiology. 2005;5:655–662. doi: 10.1093/glycob/5.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.