Abstract

Objective:

To explore the attitudes and beliefs of obstetrician-gynecologists in the United States (US) regarding the Medicaid postpartum sterilization policy.

Study Design:

We recruited obstetrician-gynecologists practicing in ten geographically diverse US states for a qualitative study using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists directory. We conducted semi-structured interviews via telephone, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using the constant comparative method and principles of grounded theory.

Results:

We interviewed thirty obstetrician-gynecologists (63.3% women, 76.7% non-subspecialized, and 53.3% academic setting). Participants largely described the consent form as unnecessary, paternalistic, an administrative hassle, a barrier to desired patient care, and associated with worse health outcomes. Views on the waiting period’s utility and impact were mixed. Many participants felt the sterilization policy was discriminatory. However, some participants noted the policy’s importance in terms of the historical basis, used the form as a counseling tool to remind patients of the permanence of sterilization, felt the policy prompted them to counsel regarding sterilization, and protected patients in contemporary medical practice.

Conclusion:

Many physicians shared concerns about the ethics and clinical impact of the Medicaid sterilization policy. Future revisions to the Medicaid sterilization policy must balance prevention of coercion with reduction in barriers to those desiring sterilization in order to maximize reproductive autonomy.

Implications -

Obstetrician-gynecologists are key stakeholders of the Medicaid sterilization policy. Obstetrician-gynecologists largely believe that revision to the Medicaid sterilization policy is warranted to balance reduction of external barriers to desired care with a process that enforces the need for counseling regarding contraception and reviewing patient preference for sterilization throughout pregnancy in order to minimize regret.

Keywords: Medicaid, postpartum sterilization, disparities, obstetrician-gynecologists, unintended pregnancies, women’s health policy, reproductive justice

1. Introduction

Unfulfilled sterilization requests contribute to adverse public health outcomes largely related to subsequent, often short interval, unintended pregnancies [1–3]. In the United States (US), unfulfilled sterilization requests are more common among women with Medicaid insurance [4–6]. This disparity is due, in part, to challenges complying with the federal Medicaid sterilization policy, which requires women to sign a standardized consent form and fulfill a minimum 30-day waiting period. Women with private insurance are not subject to these requirements [5]. The policy arose in the 1970s in response to a decades-long eugenics movement in which physicians were sterilizing racial/ethnic minority women and those of low socioeconomic status without their consent [2]. However, in contemporary practice, this policy may serve as a barrier to care for the very population it was designed to protect [2–7]. Challenges identified with the form include ensuring the form is available and waiting period has elapsed, literacy level of the form that surpasses the recommended literacy level for patient education and consent materials, lack of availability of the form in languages other than English and Spanish, and loss of Medicaid insurance after the immediate postpartum period have all been identified as challenges with the current policy [8–10]

Obstetrician-gynecologists (ob-gyns) play a pivotal role in the implementation of the Medicaid sterilization policy by providing comprehensive contraceptive counseling and performing sterilization surgery [11–13]. Several studies have looked at the role of non-medical factors that influence ob-gyns decision-making about providing sterilization, including implicit bias based on patient characteristics such as age, parity, race, and insurance status, among others [14,15]. Further, structural barriers to care given the intersection of classism and racism as well as the availability of alternatives to sterilization such as immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) may also impact clinical practice [14,16,17]. However, the viewpoints of ob-gyns regarding the Medicaid sterilization policy has, to our knowledge, largely not been reported. Therefore, we sought to explore the attitudes and beliefs of ob-gyns surrounding the Medicaid sterilization policy.

2. Materials and Methods

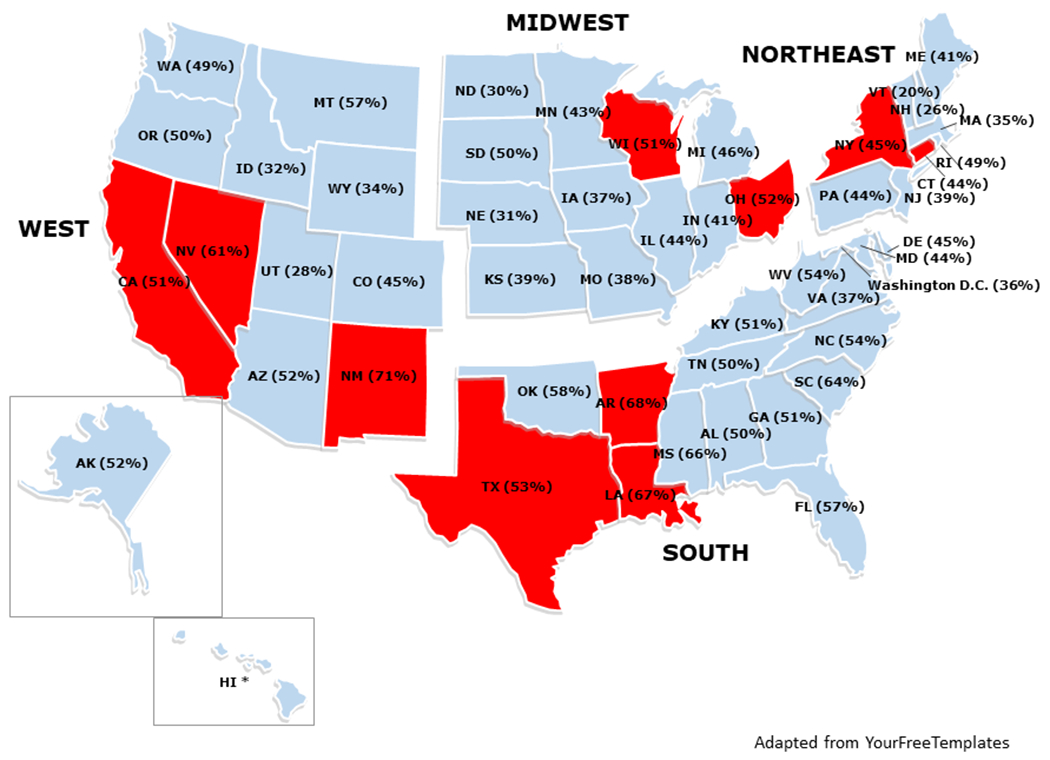

In this qualitative study, we conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with board-certified ob-gyns. We planned to initially interview approximately 30 physicians in order to likely achieve thematic saturation (or the point at which no new themes are identified). Given the desire to select a geographically diverse sample of physicians who likely had familiarity with the Medicaid sterilization policy, we selected two states within each of the four US census macro regions with the highest percentage of Medicaid-paid births in 2016 [18]. We also chose to include Texas and California given the large number of Medicaid-paid births and prior empiric studies on postpartum sterilization policies, for a total of ten states (Figure 1) [12]. We identified potential participants using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) online physician directory, which is searchable by state and lists members in each state by city. To identify ob-gyns, we first randomly selected ten cities per state and imported the names of ob-gyns in these ten cities into Excel. Junior Fellows in Practice, Fellow Senior Status, and Life Fellow or Founding Life Fellows were excluded as we sought to focus on Fellows with active clinical practices. We then randomized these names within the sheet. We contacted all selected physicians by practice email address if available by searching Google; if no email was found, we then contacted them by phone and fax. We attempted to contact each physician up to three times. We continued recruiting sequentially from the randomized list until we had interviewed three physicians in each state.

Figure –

Geographic distribution of study participants’ location selected by two states in each United States census macro region with the highest rate of Medicaid deliveries in 201612 in addition to Texas and California (red)

* Data not available

Before contacting potential participants, we developed and pilot-tested an interview guide with three ob-gyns. We revised the interview guide based on these pilot interviews. We obtained informed consent from participants before the interviews. We began interviews by asking questions regarding self-reported demographics and clinical practice type. We also asked about the types of practices and processes involved for women seeking postpartum sterilizations at their institutions. We included prompts regarding the positive and negative aspects of the policy, memorable clinical examples of use of the form, attitudes and concerns surrounding the use of the Medicaid sterilization form, opinions regarding the purpose of the waiting period, as well as similarities and differences in clinical practice and attitudes between women with private and Medicaid insurance seeking sterilization. Three individuals (R.P., L.M., and K.S.A.) with formal training and prior experience in carrying-out in-depth interviews as well as knowledge of sterilization practices conducted the interviews. We offered a $75 gift card as a token of appreciation for the participants’ time, as well as a $15 gift card to the practice support staff who assisted with coordinating the interview.

We audio-recorded interviews with participants’ permission, and professionally transcribed the files. We used Dedoose, a qualitative analysis software program, to code and manage the transcript data. Code development began with transcripts from five initial interviews, identifying thematic domains. We then coded the remainder of the interviews using a successive coding passes strategy, beginning with open coding of content at the level closest to the content of the text and continuing through broader and more analytic codes. We further delineated thematic domains as content analysis continued using principles of the grounded theory method [19]. We developed a coding scheme and dictionary using the constant comparative method throughout data analysis [19].

Two project staff (R.P. and L.M.) independently coded each transcript followed by a process of consensus coding. We reviewed and resolved any differences in coding at weekly team meetings. We identified 16 primary domains of inquiry and 24 sub-codes within the primary domains resulting in a total of 38 codes. We determined we reached thematic saturation by the completion of the 30 interviews as no new codes were generated in the final several interviews. Therefore, we made the decision to not conduct additional interviews in the ten selected states. We utilized a comparative analysis to examine the presence or absence of particular major domains and sub-themes across the interviews to look for areas of discussion that were unique to particular groups. We entered demographic information into Excel to conduct descriptive statistics.

The institutional review board at MetroHealth Medical Center approved this study.

3. Results

We interviewed a total of 30 ob-gyns by telephone among these 10 states (three in every state except four in Ohio and two in Rhode Island) (Table 1). Participants described both negative and positive aspects of the Medicaid sterilization policy. We describe these themes below and highlight findings using illustrative quotes with additional participant quotations presented in Table 2.

Table 1 –

Demographic and Practice Characteristics of Obstetrician-Gynecologists Qualitatively Interviewed Regarding Postpartum Sterilization

| Characteristics | Participants (N=30) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 19 (63) |

| Male | 11 (37) |

| Years in Practice | 20 (11-29) |

| Practice Type | |

| Academic | 16 (53) |

| Private | 8 (27) |

| Multi-specialty Group | 4 (13) |

| Hospital-based | 2 (7) |

| Specialty | |

| General obstetrician-gynecologist | 23 (77) |

| Maternal-Fetal Medicine | 3 (10) |

| Family Planning | 1 (3) |

| Other subspecialty | 2 (7) |

| Percent Medicaid Population Served | 55 (35-80) |

| Practice Location* | |

| Urban | 20 (67) |

| Suburban | 9 (30) |

| Rural | 2 (7) |

| Census Region | |

| Midwest | 7 |

| Northeast | 5 |

| South | 9 |

| West | 9 |

Presented as n(%) or median (interquartile range)

One participant noted both a suburban and rural practice location

Table 2 –

Themes and Representative Participant Quotations Selected from Thirty Interviews with Obstetrician-Gynecologists Regarding Postpartum Sterilization

| Criticisms of Form | |

| Administrative Hassle | “They have to have gone through the full rigmarole of sign the paper, paper in the right place, interpretation of the timeframe, et cetera.” “If the form is not in the chart, if the patient goes to the hospital she can swear up and down that she signed a form in the office. She came in emergency to the hospital. It’s Saturday morning and you don’t have the form. She can’t have a tubal ligation.” |

| Unnecessary | “I mean, yeah, they still have to sign a surgical consent with that, so I think all of the pertinent information with regards to risk/ benefits alternatives are discussed with the physician and the patient and that suffices.” |

| Paternalistic | “I think from again, an equity and justice standpoint, people should be allowed to do what they wanna do. We’re certainly not protecting poor women here like we’re some sort of savior.” “That said, it’s not like people don’t know what a tubal is. Most people understand that it’s sterilization. Most understand the permanency.” |

| Barrier to Care | “I honestly really don’t feel—I feel like it’s more of a barrier for my patients more than anything else, a barrier for them getting a procedure done that they want. I really don’t think the form serves much of a purpose other than preventing patients from accessing contraception.” “I think the patient who’s gotten limited care and several pregnancies and comes in in labor or needing a repeat C-section, and she hasn’t sought since 26 or 30 weeks and no one went over the paperwork and it’s her third or fourth C-section, and she say, ‘well you’re tie my tubes while you’re in there, right? Cause I can’t do this again.’ ‘Um, no, I’m not cause you have to sign this form.’ I think that situation, where we’re not even asking about it, where the patient comes in like, ‘I’m gonna be open. You’re gonna do this,’ is probably the most devastating of them.” “…but if you have somebody who this is their tenth child, they tell you, you know, ‘I’ve wanted it sort of past my fourth one, but I couldn’t never get the tubal papers signed soon enough,’ and it’s obvious they want it and they’re telling you before they’re in the pains of labor, but it happens to be on the same day, I think that I don’t question that this isn’t what the patient wants.” |

| Negative Health Outcomes | “say they had a c-section, which you know this could potentially require another surgical procedure, it just gets into a huge mess and you want to do what’s right for the patient, but you can’t incur those costs over and over again, and so these patients potentially leave the hospital without getting this tubal, potentially get pregnant again before it’s all said and done, and it’s really like we see this all the time, or even despite due diligence and efforts that we’ve made in the postpartum period, they get lost to follow-up, and then don’t present until their next pregnancy.” “let’s say I have a patient, who, for whatever reason, may have missed a visit and now they’re outside of the window of time where the form is gonna be valid and now Im gonna do a cesarean delivery expected, or expectedly, but I cannot do a tubal because she did not sign the consent form within the window of time. Now my next option is to do your surgery and then bring you back for a second surgery.” |

| Waiting Period | |

| Restrictive | “It’s interesting that, you know, a Medicaid hysterectomy, they just have to sign it. There’s no waiting period. But the tubal ligation is a waiting period.” “Probably just the fact that it doesn’t always get done in the fashion that it could have been, so they don’t get their procedure or whatever. Unfortunately, because, just because of the, again, lack of compliance or inconsistency with prenatal care, yeah.” |

| Beneficial | “I’d probably have a longer waiting period than three days, but that’s just me.… I’d probably make the waiting period a couple months… ‘cause people do change their mind. “ “I think the concept of having them sign ahead does demonstrate forethought and solid intention. If you just got the signature after they had delivered, that really might not be the ideal moment. If you’ve had a lot of pain in labor, you might be signing things you regretted later. I think the idea of getting consent months in advance is reasonable.” |

| Discriminatory Policy | |

| “Yeah, this one woman who’s on Medicaid I have to keep talking about it, and have this form signed by then, and revisit it, but the person on private insurance, I’d be like, “Oh, she’s okay. It’s alright.” | |

| I will have patients that sometimes come in that really want their tubes tied, but they came in at 37 weeks. They deliver their baby that same day or in the next today, and I can’t provide that procedure to those patients.…I do sometimes feel like they put some of our women at a disadvantage [because] the private insurance patients don’t have to wait 30 days. They can make up their mind that day.” | |

| If they wanted a tubal ligation six weeks later, we still get consent during pregnancy just in case they may have an emergency caesarean delivery…Private does not need it. That’s correct. That’s why I find it intrusive, invasive, inappropriate.” | |

| Putting Policy in Perspective | |

| Historical basis | “The historical purpose of the form was to create a—was to create an environment of transparency so that women understood what permanent sterilization means. In the history of Tuskegee and the history of other situations where practitioners would decide whether a patient needed to be sterilized or not.” “It was created to not cause unethical practices in “vulnerable populations,” but it seems to unfortunately in present time actually create the opposite and create a disparity among insurance and women with insurance and women without insurance so that it’s harder for them to get tubal ligations.” |

| Counseling tool | “I see it as an opportunity to protect the patient so she understands what she’s getting into, she understands that she’s consenting to what she wants, she understands what the risks and benefits are, what the—it is a permanent sterilization procedure that is not just, “oh, yes, just get ‘em reversed” kind of thing.” |

| Remind physicians to discuss | “think if it’s not in your normal practice to- to have a conversation about contraception, um, I guess it forces you to do that because you know the timing needs to occur.” |

| Protect contemporary patients | “For example, if you know then the provider can’t decide this woman needs tubes tied…she is reproducing, she is taking care of her kids and being judgmental and saying, you know, like I and mentioned, their third trimester they’re miserable. They say they don’t want any more kids, but they never brought it up before. That way you can’t make someone do it, or talk then into doing it where they really hadn’t planned that.” To me that’s bottom line is we should be doing whatever the patient wants. It’s just a matter of how you put in safety features so that we make sure patients are not being coerced and so that patients are not saying something they don’t really mean just because they’re in pain. |

3.1. Criticisms of form

Participants were generally critical of the Medicaid sterilization consent form. The negative attitudes were reflected equally across all geographic regions. Many of the participants (n=20, 66%), particularly in the South and the West, felt the form was not helpful for the patient care they provided as it omitted important information physicians felt patients should know. In particular, participants criticized the form as it did not necessarily help them appropriately counsel patients in making decisions about sterilization. One respondent commented, “to me, it’s more of like this is a regret form, not necessarily a full consent form because it doesn’t really talk about the risk of bleeding, the risk of infection, the risk of failure.” These critiques led a female physician with over 10 years in practice in a suburban setting to state, “I think again, the form is just there to check the legal and administrative box…I don’t think the form is there to really help women make a decision. I think the clinicians have to help women make a decision.”

A significant concern shared by many physicians was how frequently the requirement to have a signed consent form created obstacles that undermined patient care. Some commented that patients’ irregular visits during pregnancy made it difficult for them to sign the form at least 30 days prior to delivery. Even when the form was signed on time, administrative issues, such as not having the signed form documented in a patient’s chart, also could prevent some women from obtaining a desired sterilization. A physician practicing in an urban setting in the South explained, “She forgot to bring the paper. The process for scanning into the chart, it goes down to Medical Records, and then they scan it. Sometimes it’s just a couple of weeks. So it wasn’t actually scanned into her chart yet. Nobody called me to say, oh, this patient wants a tubal. Do you have a copy of the consent?…They just didn’t do the tubal.”

For some in the South and Northeast, the form was identified as paternalistic, and represented governmental interference with patient autonomy. One male physician practicing for over 30 years in the Northeast stated, “I would get rid of the form. People have the right to make their own decisions. I don’t need the government to dictate to my patients how to do things.” Finally, several respondents commented that because some women were unable to get a sterilization owing to the lack of a valid, signed consent form, they had subsequent unintended pregnancies. Many of these participants noted that the availability of inpatient postpartum LARC at their hospitals served as a potential alternative strategy for patients with Medicaid insurance for whom the consent form was not valid.

3. 2. Waiting Period

Just over half (n=16) of the clinicians interviewed did not agree with the waiting period requirement because it may affect patients’ ability to achieve the desired sterilization. There were no differences observed across geographical region. In addition, many of these clinicians stated that a mandatory waiting period did not respect the patient’s autonomy and capacity to know what is best. One female physician practicing in the South commented, “I think these are grown up women…they can make up their own minds… it’s almost a little insulting that if someone wants their tubes tied that they have to wait to be told what they want.” Some clinicians also noted that waiting periods of similar lengths were not required for other procedures stating, “With proper counseling, risks, benefits, and alternatives, there is no waiting period for other surgical procedures, so I don’t see why there needs to be one for this.”

However, a minority of physicians, who were more likely to practice in the Midwest or the South, did support the current waiting period, given the potential for regret or the permanence of the procedure. Male physicians more commonly supported waiting periods than female physicians, either for Medicaid patients or for all patients. Of the eleven male respondents, five indicated that waiting periods were essential for some or all patients while only six of nineteen female respondents felt the same. One male physician in the South stated, “I think the concept of having them sign ahead does demonstrate forethought and solid intention. If you just got the signature after they had delivered, that really might not be the ideal moment. If you’ve had a lot of pain in labor, you might be signing things you regretted later. I think the idea of getting consent months in advance is reasonable.” Another stated, “I guess, the one benefit to the 30-day consent is that patients who change their mind, you may have a lower rate of regret because they actually have the time frame to really think about it. I think they may be really have a little more time to think about the procedure, so I think, in that way, it’s beneficial because they really—when they come in and they get the procedure done, they really want it done… It allows me to have the confidence that I’m doing the procedure on people who really want it done.”

Although some physicians commented that a 30-day waiting period was too long given the barriers it created, they believed a shorter waiting period was reasonable to reduce regret and prevent making a permanent decision under duress. One male respondent practicing in the South stated, “I think the optimal waiting period, that may be subject to debate, but yeah, I think a waiting period is yes, you know, give certain circumstances, certain anxiety, the pregnancy or situations, then having a decision like that being made under duress is not good, so I think a wait is essential…I think you know to be perfectly honest, that is something that probably varies from each situation, but I think, honestly, if I were to say, 48 to 72 hours is a start.”

3.3. Discriminatory Policy

Additionally, many physicians expressed concerns about the different consent requirements for women with Medicaid versus those with private insurance. “I feel like it’s not really fair to have people that are on Medicaid wait and not others,” said one participant. Several (n=13) of the physicians, across the geographic regions, alluded to the potentially discriminatory implications of the policy. Physicians from the Northeast were less likely to discuss discrimination than physicians from other regions of the United States. Some physicians suggested that this may further exacerbate existing health disparities for this population. One female physician in the South commented, “It means women have to have access to healthcare early, which we already know is a problem in – we see it in our Medicaid population and in our African-American population, they enter prenatal care at a later gestational age in our system than our white, non-Hispanic women.… It’s harder to make sure that we’ve signed the paper within the right timeframe, whereas you can just ask patients who have insurance, “Do you want a tubal ligation? Are you sure you want it?” and have that conversation. They can just have a tubal ligation now.”

On the other hand, when discussing whether the current policy leads to inequitable treatment, most participants, from across all regions, that supported the concept of waiting periods felt that waiting periods should be applied to both privately insured and Medicaid patients, rather than only to one group. Only two participants felt the waiting period should be applied only to patients with Medicaid insurance due to concerns of age and potentially-associated regret.

3.4. Putting the Policy in Perspective

Although participants expressed multiple criticisms about the Medicaid sterilization policy, about half of the participants (n=16) identified some aspects of the policy that were positive, or they placed the policy in perspective when asked about their overall perspective of the form and the associated waiting period. Participants from the Midwest were most likely to express a positive aspect, while those from the Northeast were the least likely. For example, several physicians discussed the historical basis for the policy was to protect women who are from vulnerable populations stating, “I think it’s problematic to just get rid of it entirely because of the history of coercion for low-income women.” However, many also stated that the policy may now be outdated and doing more harm than good. One of these participants, a female physician practicing in the West, stated, “It was created to not cause unethical practices in ‘vulnerable populations,’ but it seems to unfortunately in present time actually create the opposite and create a disparity among insurance and women with insurance and women without insurance so that it’s harder for them to get tubal ligations.” There was no relationship between knowledge of the historical context and viewpoint regarding the contemporary need for a waiting period. Participants also did not discuss racism, implicit bias, or the ongoing need for protection from coercion in contemporary medical practice and largely reported that such discriminatory attitudes have changed over time.

Physicians from all regions also commented that the form, specifically, is another reminder of sterilization’s permanency and provides an opportunity to ensure voluntary consent. Some physicians used the form in their practice to counsel patients. One female participant in the West stated the form in essence required improved counseling for those with Medicaid versus private insurance stating that, “The funny thing is – cause we get so many Medicaid patients, sometimes it feel like that’s the norm, and when I see someone with commercial insurance, and we have to treat on their schedule, it feels almost wrong to counsel her less because she doesn’t have to come back, because she doesn’t have to wait…It’s a differential in the other way.” Thus, while most participants reported that comprehensive and longitudinal contraceptive counseling occurred despite the presence of the form, several did note the form was beneficial as it reinforced this need.

4. Discussion

Many physicians in this study shared concerns about the Medicaid sterilization policy, reporting that it was unnecessary, an administrative hassle, undermined patient decision-making, and discriminatory. While many participants were aware of the policy’s historical basis, most viewed it as creating systemic barriers for their patients who autonomously desired sterilization. A minority of physicians interviewed found the policy useful in terms of reinforcing key points of discussion during patient counseling and potentially minimizing regret by enforcing a waiting period.

The waiting period was emphasized as a key aspect of the policy that impinged on reproductive autonomy, especially as few other procedures require a 30-day waiting period. Many physicians in this study found the waiting period discriminatory as it only impacted women with Medicaid insurance. Some physicians, however, noted that the waiting period was helpful in ensuring patients truly desired sterilization and therefore, served to minimize regret. It was also noted by some physicians that rather than eliminating the waiting period entirely, it would be preferred to extend the waiting period to all women, regardless of insurance. One prior qualitative study demonstrated that the waiting period did not add value for the women interviewed, but the interviewees felt may be useful for other women [20]. Therefore, further exploration of the decision-making process surrounding sterilization could illuminate the value of the waiting period and the potential for regret.

Many physicians in this study also believed the policy was outdated and no longer necessary because they perceived the historical attitudes and practices which resulted in the protective Medicaid policy were no longer occurring in contemporary medical practice. However, physician bias and structural racism still contribute to disparities in maternal and child health outcomes [21–26]. Yet, no participant discussed this ongoing need for protection from potential coercion in interviews, highlighting a need for continuing professional education and reflection. For example, studies demonstrate paternalistic counseling regarding sterilization based on non-medical factors, such as age, parity, and marital status [14,15]. In our study, several physicians remarked during interviews that they were more likely to perform sterilizations if women had higher-order parity. While higher-order multiparity does confer additional pregnancy risks, physicians should be careful to not impose their own views regarding ideal family size or parity by either withholding or urging sterilization solely based on number of children [5]. Therefore, any future revisions to the Medicaid sterilization policy must balance prevention of coercion with reduction in barriers to those desiring sterilization in order to maximize reproductive autonomy [27].

Several physicians also noted that the consent form was useful in terms of reinforcing the need to counsel regarding sterilization early in pregnancy. Ideally, comprehensive contraceptive counseling is provided to all patients during their antenatal care – not just those desiring sterilization [28,29]. Participants also noted using the sterilization consent form as a tool during the informed consent discussion. However, the form is written above the recommended health literacy level of patient education materials, and many patients expressed difficulty with understanding the content of the form in prior studies [2,9,30]. Use of validated counseling and decision-making tools for contraceptive counseling, as well as revising the current Medicaid form to adhere to contemporary health literacy standards may, therefore, be more helpful for patients than the current practice [28].

Limitations include the potential for response bias as those whose practices are more impacted by the sterilization policy may have been more likely to respond. It is possible that our sample was entirely non-Hispanic white. As we did not ask about race, we are unable to assess whether and how personal experiences of racialized identity influence physician beliefs. Thus, the impact of physician demographic factors such as gender and race on sterilization counseling and practice deserve further study. Further, the potential for social desirability bias may have impacted the interviews as physicians may not have felt comfortable disclosing their attitudes regarding counseling practices for sterilization or whether the waiting period was beneficial. While we observed some differences on sterilization attitudes and beliefs based on gender and geographical region, further quantitative study is necessary to fully assess these patterns. While some participants noted that the ability to provide inpatient postpartum LARC served as an additional contraceptive option for patients who were unable to receive a desired postpartum sterilization, further exploration into the impact of inpatient postpartum LARC on sterilization rates, counseling by clinicians, patient preference, and the potential for coercion is needed [17,31,32].

In conclusion, the attitudes and beliefs of obstetrician-gynecologists surrounding the Medicaid sterilization policy are complex and diverse. Physicians are largely frustrated with the hassle and impact of the current policy. Yet, it is unclear what the ideal revision to the policy should entail given the need to balance protection from coercion, reduction in barriers, minimization of regret, and eliminate the discriminatory application. It is necessary to further obtain the input of patients, grassroots activists, clinicians, human rights attorneys, and health administrators as to the goals and nuances of such a revision. Further exploration of patient decision-making and an assessment of the occurrence of paternalistic or biased counseling in contemporary practice and systemic barriers to care are necessary to formulate evidence-based revisions to the Medicaid policy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Disclosure:

This project was funded by a grant from the Society for Family Planning Research Fund (SFPRF11-16) and the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, KL2TR0002547 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research (Dr. Arora. Dr. White received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01 HD079563). This manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or SFPRF.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion no. 530: access to postpartum sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:212–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Block-Abraham D, Arora KS, Tate D, Gee RE. Medicaid consent to sterilization forms: historical, practical, ethical, and advocacy considerations. Clin Obstet and Gynecol 2015;58:409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Borrero S, Zite N, Potter JE, Trussell J. Medicaid policy on sterilization—anachronistic or still relevant? N Engl J Med 2014;370:102–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum tubal sterilization. Contraception 2006;73:404–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion no. 695: sterilization of women: ethical issues and considerations. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arora KS, Wilkinson B, Verbus E, Montague M, Morris J, Ascha M, et al. Medicaid and fulfillment of desired postpartum sterilization. Contraception 2018;97:559–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterilization requests. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116(5): 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zite NB, Philipson SJ, Wallace LS. Consent to sterilization section of the Medicaid-Title XIX form: Is it understandable? Contraception 2007;75:256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zite NB, Wallace LS. Use of a low-literacy informed consent form to improve women’s understanding of tubal sterilization: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Borrero S, Zite N, Potter JE, Trussell J, Smith K. Potential unintended pregnancies averted and cost savings associated with a revised Medicaid sterilization policy. Contraception 2013;88:691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arora KS, Castleberry N, Schulkin J. Variation in waiting period for Medicaid postpartum sterilizations: results of a national survey of obstetricians-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:140–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Potter JE, Stevenson AJ, White K, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Hospital variation in postpartum tubal sterilization rates in California and Texas. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morris J, Ascha M, Wilkinson B, Verbus E, Montague M, Mercer BM, et al. Desired sterilization procedure at the time of cesarean delivery according to insurance status. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134:1171–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Arora KS, Castleberry N, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ counseling regarding postpartum sterilization. Int J Womens Health 2018;10:425–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Factors influencing physicians’ advice about female sterilization in USA: A national survey. Hum Reprod 2011; 26:106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kaiser Family Foundation. Beyond the numbers: Access to reproductive health care for low-income women in five communities, https://www.kff.org/report-section/beyond-the-numbers-access-to-reproductive-health-care-for-low-income-women-in-five-communities-executive-summary;2019. [accessed 15 June 15 2020].

- [17].Moniz MH, Chang T, Heisler M, Admon L, Gebremariam A, Dalton VK, et al. Inpatient postpartum long-acting reversible contraception and sterilization in the United States, 2008-2013. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(6):1078–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kaiser Family Foundation. Births financed by Medicaid. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid;2017. [accessed 7 March 2017].

- [19].Straus A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Foley O, Janiak E, Dutton C. Women’s decision making for postpartum sterilization: does the Medicaid waiting period add value? Contraception. 2018;98:312–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harris L, Wolfe T. Stratified reproduction, family planning care and the double edge of history. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014;26:539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Orchard J, Price J. County-level racial prejudice and the black-white gap in infant health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2017;181:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thorburn S, Bogart LM. African American women and family planning services: perceptions of discrimination. Women Health 2005;42:23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Downing RA, LaVeist TA, Bullock HE. Intersections of ethnicity and social class in provider advice regarding reproductive health. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1803–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yee LM, Simon MA. Perceptions of coercion, discrimination and other negative experiences in postpartum contraceptive counseling for low-income minority women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011;22:1387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gomez AM, Wapman M. Under (implicit) pressure: young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception 2017;96:221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brown BP, Chor J. Adding injury to injury: ethical implications of the Medicaid sterilization consent regulations. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1348–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion no. 654: reproductive life planning to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:e66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cavallaro FL, Benova L, Owolabi 00, Ali M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of counseling strategies for modern contraceptive methods: what works and what doesn’t? BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2019;0:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Natavio MF, Cortessis VK, Zite NB, Ciesielski K, Eggers H, Brown N, et al. The use of a low-literacy version of the Medicaid sterilization consent form to assess sterilization-related knowledge in Spanish-speaking women: results from a randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2018;97:546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Higgins JA, Kramer RD, Ryder KM. Provider bias in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) promotion and removal: Perceptions of young adult women. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(11): 1932–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Meier S, Sundstrom B, DeMaria AL, Delay C. Beyond a legacy of coercion: Long-acting reversible contraception and social justice. Women’s Reproductive Health 2019;6(1): 17–33. [Google Scholar]