Executive summary

With one billion people on the move or having moved in 2018, migration is a global reality, which has also become a political lightning rod. Although estimates indicate that the majority of global migration occurs within low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), the most prominent dialogue focuses almost exclusively on migration from LMICs to high-income countries (HICs). Nowadays, populist discourse demonises the very same individuals who uphold economies, bolster social services, and contribute to health services in both origin and destination locations. Those in positions of political and economic power continue to restrict or publicly condemn migration to promote their own interests. Meanwhile nationalist movements assert so-called cultural sovereignty by delineating an us versus them rhetoric, creating a moral emergency.

In response to these issues, the UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health was convened to articulate evidence-based approaches to inform public discourse and policy. The Commission undertook analyses and consulted widely, with diverse international evidence and expertise spanning sociology, politics, public health science, law, humanitarianism, and anthropology. The result of this work is a report that aims to be a call to action for civil society, health leaders, academics, and policy makers to maximise the benefits and reduce the costs of migration on health locally and globally. The outputs of our work relate to five overarching goals that we thread throughout the report.

First, we provide the latest evidence on migration and health outcomes. This evidence challenges common myths and highlights the diversity, dynamics, and benefits of modern migration and how it relates to population and individual health. Migrants generally contribute more to the wealth of host societies than they cost. Our Article shows that international migrants in HICs have, on average, lower mortality than the host country population. However, increased morbidity was found for some conditions and among certain subgroups of migrants, (eg, increased rates of mental illness in victims of trafficking and people fleeing conflict) and in populations left behind in the location of origin. Currently, in 2018, the full range of migrants’ health needs are difficult to assess because of poor quality data. We know very little, for example, about the health of undocumented migrants, people with disabilities, or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, or intersex (LGBTI) individuals who migrate or who are unable to move.

Second, we examine multisector determinants of health and consider the implication of the current sector-siloed approaches. The health of people who migrate depends greatly on structural and political factors that determine the impetus for migration, the conditions of their journey, and their destination. Discrimination, gender inequalities, and exclusion from health and social services repeatedly emerge as negative health influences for migrants that require cross-sector responses.

Third, we critically review key challenges to healthy migration. Population mobility provides economic, social, and cultural dividends for those who migrate and their host communities. Furthermore, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, regardless of location or migration status, is enshrined in numerous human rights instruments. However, national sovereignty concerns overshadow these benefits and legal norms. Attention to migration focuses largely on security concerns. When there is conjoining of the words health and migration, it is either focused on small subsets of society and policy, or negatively construed. International agreements, such as the UN Global Compact for Migration and the UN Global Compact on Refugees, represent an opportunity to ensure that international solidarity, unity of intent, and our shared humanity triumphs over nationalist and exclusionary policies, leading to concrete actions to protect the health of migrants.

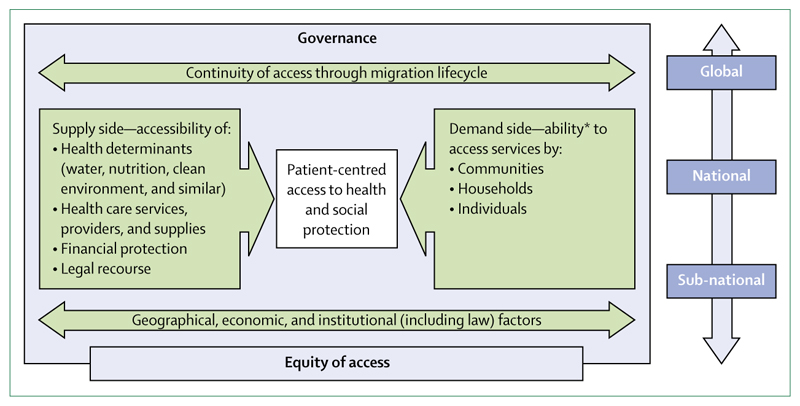

Fourth, we examine equity in access to health and health services and offer evidence-based solutions to improve the health of migrants. Migrants should be explicitly included in universal health coverage commitments. Ultimately, the cost of failing to be health-inclusive could be more expensive to national economies, health security, and global health than the modest investments required.

Finally, we look ahead to outline how our evidence can contribute to synergistic and equitable health, social, and economic policies, and feasible strategies to inform and inspire action by migrants, policy makers, and civil society. We conclude that migration should be treated as a central feature of 21st century health and development. Commitments to the health of migrating populations should be considered across all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and in the implementation of the Global Compact for Migration and Global Compact on Refugees. This Commission offers recommendations that view population mobility as an asset to global health by showing the meaning and reality of good health for all. We present four key messages that provide a focus for future action.

Introduction

Nearly one-seventh of the world’s population is now living in a location different from the one in which they were born.1 A migrant is someone who has moved across an international border or within her or his own country away from their habitual place of residence. Migration is not a new phenomenon. People have migrated throughout human history and population mobility continues to benefit many individuals and communities, contributing to social and economic advancement globally.

Despite the long history of human migration, international dialogue has recently become more prominent, although only rarely has attention been paid to migration as a core determinant of health. When individuals migrate, they enter new environments that have different health risks.2 Studies indicate that morbidity patterns among migrants are diverse and dynamic because of numerous interacting influences, such as an individual’s pre-departure health, socioeconomic and environmental conditions, local disease patterns and risk behaviours, cultural norms and practices, and access to preventive or curative therapies throughout the migration process.3

Health outcomes in migrants are heterogeneous, but evidence consistently shows the disproportionate health, social, and economic burdens of forced migration.4 Despite widespread recognition of the numerous migration related health risks, mobile populations—even forced migrants who are fleeing for their lives—are often met with punitive border policies, arbitrary detention, abuse and extortion, and are commonly denied access to care. Governments that introduce immigration policies legalising exclusion and rights abuse frequently cite national security concerns to justify migration controls that extend beyond their own borders. These policies can go as far as criminalising migrant status, and deterring asylum seekers by detaining them; even separating children from their parents, as seen in US Government immigration policies in 2018.5 All too often, government policies prioritise the politics of xenophobia and racism over their responsibilities to act forcefully to counter them.

Our current global political economy is driven by high-income industrial powers that draw on natural and human resources in LMICs. Moreover, laws and regulations that encourage unrestricted trade in goods, services, and capital are simultaneously being used to control labour mobility to further the political and economic interests of the wealthy, while often leaving poor communities behind. Global trade and pro-business policies in lower-income countries have drained natural resources, contributed to environmental degradation, and pushed people into hazardous, exploitative work to meet consumer demands for cheap goods such as so-called fast fashion.6

International conventions are in place to guide policy to support safer and more inclusive migration and can be used to counter some of these negative forces. As for all human beings, migrants are equally entitled to universal human rights without discrimination. All migrants thus have the right to the "highest attainable standard of health" according to international law.7 All migrants are entitled to equal access to preventive, curative, and palliative health care.8 They also have rights to the underlying social, political, economic, and cultural determinants of physical and mental health, such as clean water and air and non-discriminatory treatment.8 Human rights treaties entitle migrants to due process of law in border practices and freedom from arbitrary detention and restrictions on movement. These rights do not merely impose legal obligations on governments but are essential preconditions for social and economic integration, prosperity, social cohesion in any society, and wellbeing in the modern world.9 The substantial gap between the international legal requirements guaranteeing the human rights of migrants and the implementation of these laws by states provides important context for this Commission report.

In 2016, at the UN General Assembly, the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, and a further Compact to respond to acute and chronic refugee situations were initiated in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development target 10.7 (to facilitate safe, orderly, and responsible migration).10,11 Yet, these essential multilateral processes appear to be heading in a precarious direction, as exemplified by the US Government’s withdrawal from the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in 2017,12 the creation of potential internment camps termed migrant centres,13 and the reluctance of some EU countries to accept an equitable redistribution of migrants.

Our Commission’s journey

Worldwide mobility is our future—regardless of laws and walls. Our Commission was developed in light of the opportunity to realise the SDG commitments "to leave no one behind" and "to reach first those who are furthest behind",14 in the context of states’ guarantees to protect the human rights of migrants. We brought together 20 Commissioners with equal gender representation and wide geographical spread to generate transdisciplinary evidence, contemporary thought, and global expertise that draws on multiple scientific perspectives. To achieve this aim, Commissioners were drawn from a range of scientific backgrounds including sociology, policy, public health, law, humanitarianism, and anthropology.

We initially structured our work with working groups around key themes including health systems, labour migration, forced migration, vulnerabilities, law, human rights and politics, sociocultural factors and identity, and data and health outcomes. We undertook a series of rapid systematic reviews to identify key literature in each area and build on these, as well as two formal systematic reviews and meta-analyses that informed the Commission and are published in detail alongside the report.15,16 Our work was done over a 2-year period with two London based authors’ meetings and a week-long in-person review of the first draft of the Commission at the Rockefeller Foundation, Italy, in November, 2017, along with extensive collaborative work online and by phone.

The principles that underpin our report are equity and inclusion of migrants in access to health and health enhancing resources and opportunities. The Commission settled on five goals for in-depth examination, which provide a focus throughout the four sections of the final report. First, we review evidence on migration and health, challenge common myths, describe the composition and characteristics of population mobility, and assess uses and limitations of migrant categories. Second, we examine multisector determinants of health and consider the implication of current sector-siloed approaches, such as the dichotomous goals of the health sector versus the security sectors. Third, we critically review key challenges to healthy migration by analysing health and migration in relation to culture and identity, rights, legal issues, and environmental hazards and climate change. Fourth, we examine equity in access to health and health services and offer evidence-based solutions to improve the health of migrants. Fifth, we look ahead to consider how our evidence can contribute to synergistic, ethical policies and feasible strategies to inform and inspire action by governments, international agencies, and health professionals to promote health in global mobility.

To tackle this complex subject, we developed a Migration and Health Determinants framework to consider the interactions between migration and the individual, population, and global health (see appendix, supplementary figure 1). The framework highlights key factors influencing the health of mobile populations, including legal, social, and health structures and systems; service access and support; exposures and behaviours particular to migrants; and the epidemiological changes (positive and negative) related to population mobility. These health influences are generally relevant for each stage of a migration process. Our Commission thus offers evidence on how various factors might benefit or be detrimental to individual and population health throughout a journey—including at origin, transit, destination, and return.

Migration and health is a diverse topic with an extensive existing literature. Although we began with a broad and ambitious remit, it is not possible to cover all aspects of migration and health, nor give an overview of all groups of migrants and the conditions they experience. There are many other facets of migration and health that were beyond the specific remit or bounds of the five main goals of this Commission, but we plan to do more in the post-Commission phase in collaboration with others across sectors who are working in this space. Recognising the Lancet Series on Health in Humanitarian Crises, and the Syria Lancet Commission, we have not presented substantive amounts of reference to policy documents, examples of best practice, or deeper analysis in the field of refugee studies. We feel these areas, and wider collaboration on forced migration, will be key for the post-Commission phase in achieving further research, policy, and operational impact. In addition, although we cite on the ground case studies, we were unable to systematically explore grey literature or repositories of migration and health operational and interventional practice.

Section 1. The case for action: what do we know about migration and health

Migration is a dynamic process

Migration seldom involves a single long journey from one place to settle in another. The diversity and complexity of migration patterns include people travelling long and short distances, within and across borders, for temporary or permanent residency, and often undertaking the journey multiple times. A clear delineation or rigid categorisation of different types of migration is rarely possible. The categorisation process attempts to classify a large, heterogeneous population according to limited criteria, which are not generally suited to capture the complex social dynamics of human mobility or necessarily the perspectives or needs of the people who are moving. Terms such as voluntary or forced migration, and categories such as refugees, asylum seekers, and international and internal migrants can partly help to understand migration dynamics. These same terms can also be used to "other" and discriminate against migrants, as well as generally being administrative definitions used to classify migrants for protection, assistance, or research—rather than a true representation of individual circumstances. Legal categories are instrumental for migration control and management by states and international agencies providing support, but might not fully explain an individual’s circumstances. However, for the purposes of the evidence presented in this report, we often use existing definitions (see supplementary table 1 in appendix), which enable us to draw on up-to-date migration literature and data sources. At the same time, throughout the report we will highlight the complex drivers of migration and the difficulties and potential dangers of assigning singular or narrow definitions. Migrant categories are not necessarily objective or neutral; distinctions frequently reflect the assumptions, values, goals, and interests of the parties who assign these labels.

It is also difficult to categorise people in relation to their reasons for migrating. A myriad of negative drivers and positive aspirations (push or pull factors) exist that motivate people to migrate. Individuals, families, and groups often have mixed motives for migrating, and their reasons can change over the course of a single journey. For instance, people seeking safety from conflict can be classified as refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, or internally displaced persons. However, before and during transit, especially in protracted conflicts where aid resources are insufficient, migration decisions can also relate to livelihoods and employment. Distress migration or migration due to entrenched poverty, food insecurity, and household economic shock (eg, illness, debt), is common worldwide. Distress migration is linked to local unemployment, household financial crises, poor crop production, and in some instances, forced evictions. Evictions can be linked to rising real estate prices, large development projects, and land confiscation.

Regardless of migration motives, economic contributions, or people’s rights, populist rhetoric has morphed all people who move as migrants, condemning them, irrespective of whether they are refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, or low wage workers. The catch-all term of migrant obscures the net social, political, and economic benefits of migration for destination communities and obscures a migrant’s contribution to their place of origin, supporting families and supplementing development aid, which, in turn results in greater global health.

Health throughout the migration process

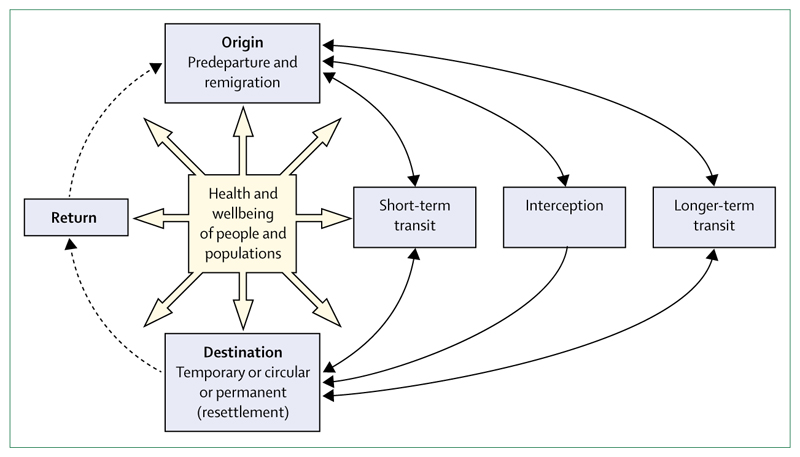

Migration trajectories involve various phases (figure 1) including, pre-departure circumstances at places of origin; short-term or long-term transit, which might involve interception by authorities, non-governmental groups, or criminal gangs; destination situations of long-term or short-term stay; and return to places of origin for resettlement or for temporary visits before remigration.3 In each phase of a person’s journey, potential health risks and possible health protective factors exist that can have a short-term or long-term effect on their wellbeing. As previously noted, the journeys are often diverse and rarely singular. It is common for labour migrants to undertake circular migration, transiting back and forth between their place of origin and destination, or remigrating to a new destination. When people are transiting between locations, their health and safety depends on the forms of transport (air travel, on foot across deserts, hidden in trucks) and the pathogenic or environmental exposures (malaria, tuberculosis, violence, heat exhaustion, dehydration) along the transit routes.17 Return migration also poses health risks and benefits. For instance, communities of origin could benefit from new skills or improved health behaviours gained by returning migrants,18 but conversely, individuals who are injured or disabled during their journey might return to locations with few services or support mechanisms. Importantly, policies to protect migrant and public health will be most effective if they take advantage of opportunities to address people’s health needs at the multiple phases of the migratory process.3 Maintaining the mental health and wellbeing of migrants and the families they might leave behind is particularly important. Even in the best possible conditions, migration is stressful and most people move in ways that are far from ideal; the stress of migration, travel conditions, and the causes that prompted migration in the first place, can all adversely affect mental health.

Figure 1. The migration cycle.

Migration, gender, and health

Both population mobility and the health implications of migration are highly gendered. That is, women, men, and sexual minorities are likely to encounter different health risks and protection opportunities at each phase of a migration journey—a journey they might have undertaken to flee gender-based violence. The risks begin before departure, when women and children could be at risk of violence and discrimination. Among those who are forcibly displaced, there is a particular risk of sexual violence, coercion, and sexual exploitation at all stages of their migration journey, such as accounts of the widespread rape of Rohingya women and girls forcibly displaced from Myanmar in 2016–17,19 or when moving along irregular and dangerous routes ending in official and unofficial detention centres as seen in the ongoing situation in Libya.20 Even when reaching zones of apparent safety, women and children have been exploited by humanitarian workers. This problem remains widespread suggesting that women and children might need protection from their so-called protectors.21 A systematic review of women and girls in conflict-affected settings indicated their extraordinary vulnerability to various forms of human trafficking and sexual exploitation, frequently occurring as underage or forced marriage and forced combatant sexual exploitation.22 Women and children are especially at risk when they migrate without the protection of family or social networks. Unaccompanied girls and boys who move in ways that are not readily detected by potential support mechanisms are particularly vulnerable to neglect, trafficking, abuse, and sexual exploitation. Examples include unaccompanied and separated children who resort to sex work to survive and shelter in parks and makeshift camps in Greece.23 Child marriages appear to increase among displaced populations,24 as parents are often forced to make impossible choices about their daughters based on their fear of sexual violence by armed forces or combatants and economic hardship.25 Sexual minorities might be among the most neglected and at-risk populations in circumstances of migration. The stigma associated with being LGBTI can subject individuals to bullying and abuse or force them to remain invisible. There appears to be little training for health and humanitarian aid professionals currently to meet the health needs of sexual minorities.

Challenging myths

In the current political climate, the term migrant raises a litany of myths and inaccurate stereotypes. While often used for political gain, falsehoods about migrants have frequently become publicly accepted. Here, we respond to common myths by offering data driven facts.

Are HICs being overwhelmed by migrants?

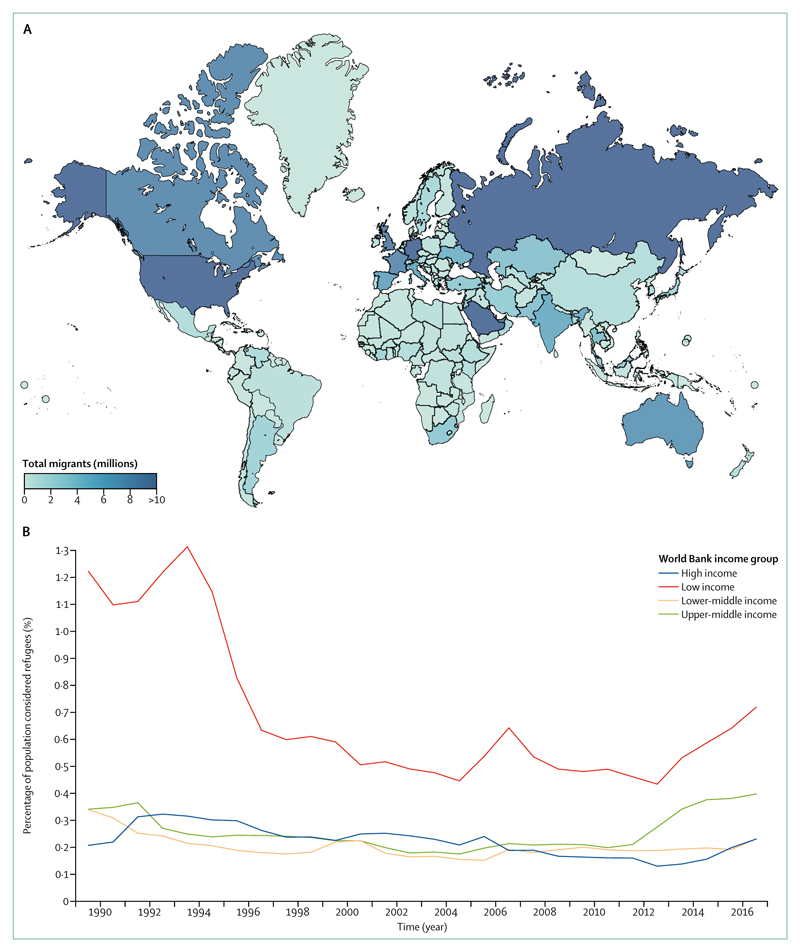

Discussions about migrants often centre around absolute numbers of migrants crossing international borders into HICs. This rhetoric tends to ignore findings that there has been little change in the percentage of the world’s international migrants, which has only risen from 2·9% to 3·4% from 1990 to 2017 globally, with diversity in geographical location of migrants (figure 2A). Although HICs have seen a greater rise in the percentage of migrants arriving from 7·6% to 13·4% (1990 to 2017), it is important to note that the percentage of the total population that were individuals who have been displaced and are currently living in HICs is considerably smaller than in LMICs. Furthermore, the figures for all international migrants in HICs include, for instance, students who pay for their education and often return to their countries of origin,28 and labour migrants who are net positive contributors to the economy. Previous waves of migration as a percentage of the global population (eg, Europeans colonising the Americas and Australasia) have been vastly greater in number than these recent trends. Similarly, the percentage of the world’s population that were refugees generally declined between 1990 and 2011. Subsequently, all countries saw an increase, but this was highest in LMICs (figure 2B). HICs had very little change in their refugee population, and it was low-income countries that had fluctuations from 1·3% to 0·4% (figure 2B). These data show that despite popular discourse to the contrary, changes in migration are more complex than the simple narrative of a rise in numbers. Overall, mobility patterns are highly regional and context specific, with less wealthy nations hosting disproportionate numbers of forcibly displaced populations.

Figure 2. International migration globally26.

(A) Global map of the total number of international migrants in 2015. (B) Percentage of population that were refugees by the World Bank Income group (1960-2017). Analysis done with data from the World Bank. Interactive online version available.27

Are migrants a burden on services?

Macroeconomic analysis on the effect of asylum seekers in Europe concluded that they have a positive effect on host countries’ economies.29 Nowadays, rather than burdening systems, migrants in HICs are more likely to bolster services by providing medical care, teaching children, caring for older people, and supporting understaffed services. Migration provides much needed high skilled and low skilled workers for economic growth. The way health-care markets are constructed, from both the supply and demand sides, is inextricably connected with human mobility. Hospitals, residential homes, child-care centres, and domestic and professional cleaning services are often staffed by migrants. Migrants constitute a considerable portion of the health-care workforce in many HICs and contribute to a substantial so-called brain gain in net-migrant receiving countries.30 For example, 37% of doctors in the UK gained their medical qualification in another country.31 Health-care workforce migration from poorer to wealthier countries has been the subject of extensive study. Health professionals migrate because of low remuneration, poor working conditions, work overload, and insufficient opportunities for professional advancement in their home countries.32 Higher-income countries reap the benefits. It is LMICs, such as Syria and Turkey, who host a higher proportion of displaced people, where it is challenging to deliver services for the poorest members of society. Although many migrants can access the labour markets, there are also many who might not have this same access with immediate and long-term consequences on livelihoods, social security, education, and health. Our systematic review and meta-analysis16 of global patterns of mortality however, provides evidence that international migrants, particularly those in HICs who are more likely to have actively chosen to migrate (such as economic, student, and family reunion migrants), are more likely to live longer compared with host populations across the majority of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 categories.

Are fertility rates among migrants higher than among host populations?

Despite populist rhetoric that migrants have many more children than host populations, the growth and decline of migrant populations in a country is affected by birth and death rates and inward and outward migration from a country. Using large scale longitudinal data from six countries (France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and UK), researchers found that migrants have lower first-birth rates than non-migrants with the exception of migrant Turkish women.33 Moreover, birth rates among migrants were barely at the level of population replacement (a total fertility rate below 2·1 births per woman) and often falling. Access to contraception also influences differences in fertility rates. Poor access to contraception among migrants is often related to inconsistent policies, guidelines, and provision of services. In the EU, migrants appear to have inadequate access to sexual and reproductive health care, including family planning services.34

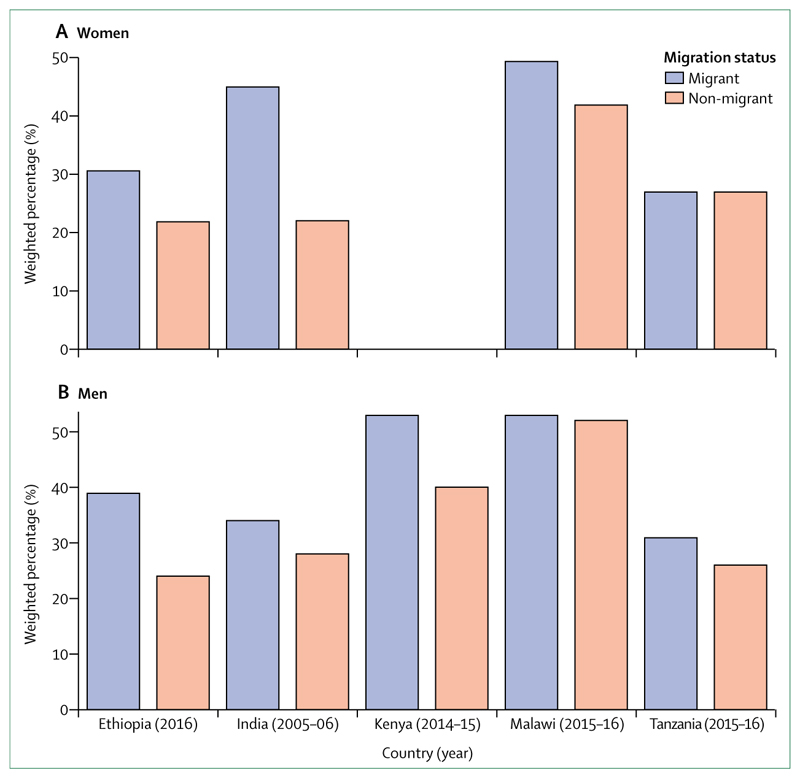

Evidence about fertility and its association with internal migration in LMICs is scarce. With Demographic and Health Survey data for the use of modern contraception by an individual’s migration category in five LMICs (Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Malawi, and Tanzania), we show that in each country internal migrants used modern contraception methods more often than non-migrants (figure 3). These results could be explained in substantial part by a person’s educational and socioeconomic status, supporting evidence that migrants have lower first-birth rates than non-migrants—and dispelling negative views about fertility among migrants. However, these data might not represent patterns among more marginalised groups such as undocumented migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, or displaced populations in humanitarian crisis situations. For these marginalised groups, in whom sexual assault is common, there is an even greater need for readily accessible sexual and reproductive health care.40

Figure 3. Weighted percentage of men and women using modern methods of contraception by migration status35–39.

No data available for Kenyan women.

Are migrants damaging economies?

An overwhelming consensus exists on the positive economic benefits of migration, which is insufficiently acknowledged. In settings that offer universal access to minimum economic benefits, there has been much debate as to whether migrants receive more in social assistance than they contribute in taxes. The evidence examining this issue generally suggests that migrants make greater overall contributions, except in countries with a high proportion of older migrants.41 In advanced economies, each 1% increase of migrants in the adult population increases the gross domestic product (GDP) per person by up to 2%.42 Migrants increase income per person and living standards through greater contributions to taxes, which are of greater economic worth than the social or welfare benefits they receive.41 Furthermore, in the EU and some other European countries, free movement has been shown to address imbalances in the labour market43 by serving as an equilibrating force through the provision of labour where and when needed. These benefits are not just accrued by the wealthiest in society. Moreover, the World Bank Group estimated that migrants sent a total sum of US$613 billion to their families at origin in 2017.44 Approximately three-quarters of these remittances were sent to LMICs—an amount more than three-times larger than official development assistance—and these remittance flows have been growing steadily since 1990.44 In countries such as Liberia, Nepal, and Tajikistan, up to one-third of GDP comes from international remittances. Globally, these sums of money are large and can transform the lives of non-migrants.44

Are migrants disease-carriers that pose risks to resident populations?

Suspicion against migrants as carriers of disease is probably the most pervasive and powerful myth related to migration and health throughout history.45 Although historical examples exist of the introduction of disease into new settings through human mobility (eg, the spread of infection from European colonial settlers), the risk of transmission from migrating populations to host populations is generally low. For example, studies on tuberculosis suggest that the risk of transmission is elevated within migrant households and migrant communities, but not in host populations.46,47 Nonetheless, several HICs screen migrants for tuberculosis as part of pre-migration visa application checks.48 Although tuberculosis screening systems could benefit individuals through early detection, screening is often stigmatising and can spur xenophobic media messages,49 despite the negligible risk of transmission in countries with functioning public and universal health systems.46 Migrant populations might come from countries with a high burden of disease50 and it is not uncommon for disease outbreaks to be found in situations of conflict, which can disrupt already weak public health systems. Illness and infection can also be acquired or spread via transit routes and transport means. For example, air travel can facilitate the rapid geographical spread of infections. However, even risk of air travel related outbreaks is low–modest if the destination setting has strong surveillance and inclusive public health services.51 These services are also crucial to prevent pandemics, whether associated with population movement or not.52 Epidemiological patterns and related risks are readily addressed by assessing the infectious disease burden among populations and with use of data to design targeted interventions to contain outbreaks and prevent new infections through immunisation. However, because of the prejudice and unfounded fear that can be generated by misuse of surveillance data, caution is required when releasing potentially stigmatising disease prevalence figures for public consumption. We revisit this issue throughout the report and discuss the misuse of data.

Composition of mobile populations

Understanding the health of people on the move requires clarity about who is moving, why, and where, and the potential positive and negative effects. Here, we offer an overview of international migrants, internal migrants, labour migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, and climate refugees (an emerging group that is likely to increase in number). Data will be presented with use of the most widely applied migration categories—despite our previously stated reservations about the weaknesses of these categories—reviewing numbers and their associated limitations, geographical distribution, age and sex characteristics, and key issues for each group.

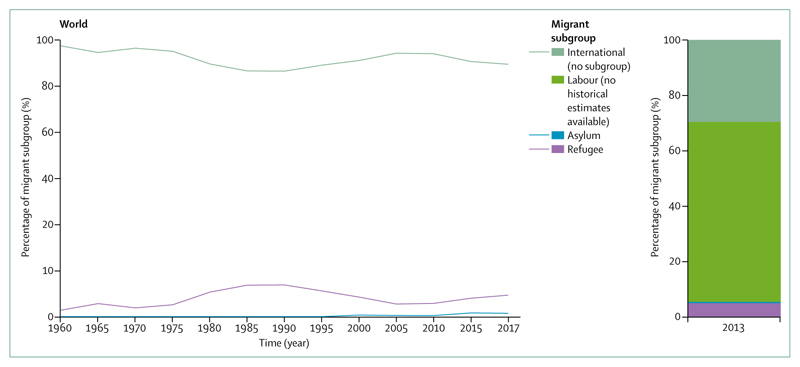

International migration

In 2017, there were an estimated 258 million international migrants, which accounted for 3·4% of the world’s population.53 Notably, most data for international migration between 1960 and 2017 did not classify migrants by subgroup. Estimates by the International Labour Organization indicate that labour migrants constituted 65% of all international migrants in 2013.54 However, 2013 was the only year for which global data were available on labour migration (figure 4). In 2017, Asia had the largest number of international migrants (80 million), closely followed by Europe (78 million), and North America (58 million).55 Globally, the largest number of international migrants were in the 30–34 age group and 48% were female.55 To date, data come primarily from population censuses, population registers, and nationally representative surveys, often with use of place of birth to establish international migrant status. For 47 countries, place of birth is not available so country of citizenship is used instead. This can potentially lead to overestimation of international migrant numbers. Conversely, these data can also underestimate migrant numbers by inappropriately excluding people born abroad with local citizenship. Data collection for international migration would benefit from better information on subgroups and categories of migrants with little data (eg, labour, undocumented, and trafficked) in order that these groups are not omitted from needs assessments and budget allocations for responses.

Figure 4. International migration by migrant subgroup26,54,55.

Percentage of all international migrants that were refugees, asylum seekers, and labour migrants, 1960–2017. Labour migration estimates only available for 2013. Refugee numbers are for those under the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ mandate and therefore do not include individuals under the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East’s mandate as data are not available back to 1960. Analysis done with data from UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Interactive online version available.27

Internal migration

Although international migration receives the most political and public attention, most movement globally is internal migration. In 2009, the number of people who moved across the major zonal demarcations within their countries was nearly four-times greater (740 million) than those who moved internationally.56 Approximately 40% of urban growth in Asia, Africa, and Latin America results from internal migration from rural to urban areas.57 In many LMICs, rural-rural internal migration to work in the agricultural sector still accounts for the largest number of people on the move.58 Previously, evidence suggested that internal migration was dominated by single men, however, recent trends show increases in women moving for work and to seek freedom from discriminatory social and cultural norms.59 From 2014 to 2050, the proportion of people living in urban areas, largely because of migration from rural areas, is expected to increase from 48% to 64% in Asia, and from 40% to 56% in Africa.57 Producing global estimates on internal migrants is methodologically challenging and routine data are rare.60

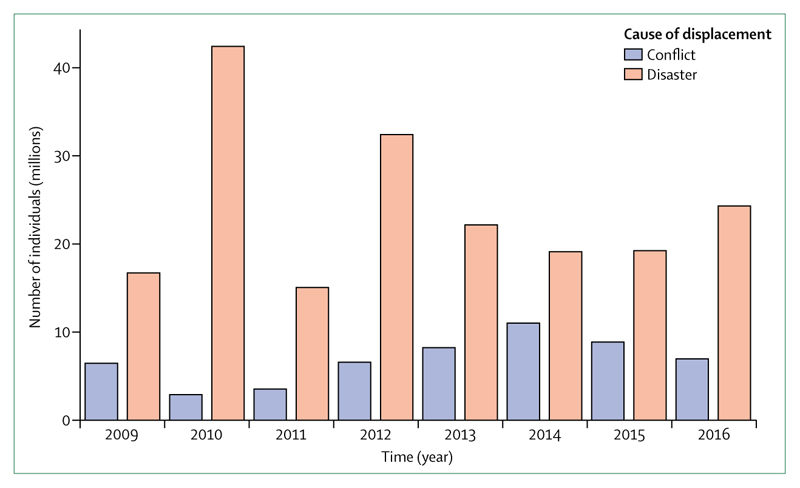

There are considerably more internally displaced persons because of conflict and natural disasters than asylum seekers and refugees globally. However, they also receive substantially less attention than asylum seekers and refugees, primarily because of the importance attached to national borders and citizenship, as well as the availability of better data collection for refugees. In 2017, there were 30·6 million newly internally displaced people associated with conflict and disaster.61 East Asia and Pacific was the region with the highest number of internally displaced people due to disasters and sub-Saharan Africa was the highest due to conflict and violence. Between 2008 and 2017, the number of individuals displaced because of conflict and violence was fewer than those resulting from disasters (figure 5).61

Figure 5. Total annual new displacements as a result of conflict and disasters globally61.

Interactive online version available.27

Labour migration

The International Labour Organization estimates suggest that in 2013 there were 150·3 million international migrant workers in the world.54 Although official figures indicate that the largest proportion of international labour migrants is in North America and northern, southern, and western Europe, these figures are perhaps misleading. Regional labour migration in LMICs often goes uncounted because of regional and bilateral labour and trade agreements, as well as undocumented or irregular border crossing.54,62 LMICs are estimated to host roughly 25% (37·9 million of 150·3 million) of total labour migrants globally.54,63 Moreover, it is important to note that these figures will be underestimates as they exclude undocumented international migration between neighbouring countries and workers in the informal economy. Among labour migrants globally, 2013 figures indicate that more migrant workers are male (56%) than female (44%).54 Women more commonly work in service jobs (74%) and less often in manufacturing and construction work (15%).54 Increases in the migration of women could be due in part to shifts in gender, social, and migration norms, and in other part by remittances they will receive,64 which create greater opportunity for women to migrate. Adolescent girls also migrate for work, driven by financial incentives,65,66 and hopes for greater freedom and empowerment. However, recognition is growing of the number of young women who end up in exploitative work.67 Comparative national data are very poor for the patterns and prevalence of internal labour migration, especially for harder to monitor forms, such as seasonal and often circular migration.

Forced migration

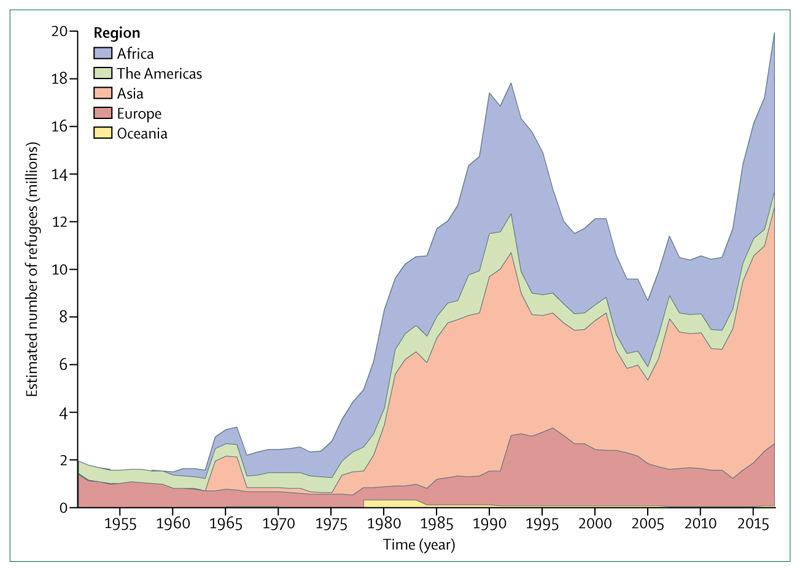

As of 2018, two billion people live in countries affected by civil unrest, violence, or ongoing conflict.68 In 2017 there were a total of 25·4 million refugees globally, with 19·9 million refugees under the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ mandate and 5·4 million Palestinian refugees under the UN Relief and Works Agency’s mandate. Monitoring historical refugees numbers that fall under the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ mandate reveals the percentage of international migrants who were refugees to have remained less than 11·4% following a peak in 1990 (figure 4). Consistent with the trend in percentage of refugees in relation to all international migrants, the number of refugees falling under the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ mandate decreased from 17·8 million to a low of 8·7 million from 1992 to 2005, followed by an increase to 19·9 million in 2017 (figure 6). Africa had the highest percentage of refugees under 18 years in terms of the countries of origin and countries of asylum application in 2015 (see supplementary figure 2 in the appendix). Further details on the regional variation in the number of refugees are provided in the supplementary figures 3 and 4 in the appendix. Previously, most forcibly displaced people lived in camp-like settings, however, now refugees are more likely to live outside of camp settings in developing regions; 85% of the world’s refugees reside in developing regions and 58% live in urban areas, as reported in the 2017 Global Trends Report. Forced displacement from long-term conflicts, such as the Syrian conflict, have resulted in a protracted refugee situation for millions of refugees, who often reside in urban and peri-urban settings without formal refugee status. For example, less than one-fifth of refugees in Jordan live in camps.69

Figure 6. Estimated refugee numbers under the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ mandate by region, 1951-2015.

Historical data in this figure do not include 5·4 million Palestinian refugees under the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East’s mandate in 2017, as historical data for this group are not available. Interactive online version available.27

There were an estimated 1·9 million claims for asylum in 2017 and a total of 3·1 million asylum seekers whose refugee status was yet to be determined.70 The number of asylum-seekers with pending claims increased by 28% by the end of 2017, compared with 2016 according to the 2017 Global Trends Report. Asylum-seekers are increasingly experiencing longer periods with pending claims. There is enormous variation in the total number of asylum seekers by country of origin (see supplementary figure 5 in the appendix) reflecting proximity to source countries, and the proportion successfully securing refugee status. In other categories of forced migrants, the numbers of individuals who are undocumented and often the most vulnerable, are not available as they are often not in contact with authorities.

Resettlement is a considerable challenge. Refugees with acute health and medical needs are among the top priorities for consideration for resettlement referral by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and some resettlement countries expedite consideration of refugees facing acute health risks. In 2018, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees established that about 1·2 million refugees around the world needed resettlement.71

Human trafficking and modern slavery

Human trafficking, forced labour, and forced marriage, now referred to collectively as modern slavery, is estimated to affect 40·3 million people globally, according to 2017 estimates from the International Labour Organization.72 These new figures indicate that there were 25 million people in forced labour and highlight that there are also 15 million people in forced marriage. This number equates to 5·4 people for every 1000 individuals in the world.73 Regionally, Asia appears to have the largest number of modern slavery cases, with 62% of all enslaved people, followed by Africa at 23%. Women and girls are disproportionately affected, accounting for 71% of cases, as are children, with one in four individuals who are trafficked under the age of 18 years. Women and girls are commonly trafficked for sex work, domestic service, and as brides. Men and adolescent boys are more likely to be recruited, often deceptively, for various forms of strenuous manual labour, including commercial fishing and construction.74 Sexual minorities who are trafficked are often subjected to forced sex work.

Climate change refugees

Global climate change is driven by anthropogenic atmospheric and oceanic warming, and has global effects causing rising sea levels, shrinking of the cryosphere, and ocean acidification. Climate change has the potential to affect and disrupt well known drivers and mechanisms of migration in the future to an unknown but potentially striking degree. The Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change,75 discusses the potential effects on migrants including the effect on urban health, extremes of heat, and the social effect of population redistribution as a result of only people from some demographics having the resources to move. A 2018 study suggested that by 2070, the combined effects of climate change and the vast expansion of irrigated agriculture could result in deadly heatwaves. Such heatwaves could make large parts of northern China, with a population of 400 million, uninhabitable.76 Climate change will also increase the frequency and intensity of hydrometeorological hazards.77

According to a 2018 report by the World Bank, climate change has the potential to force more than 143 million people to move within their country by 2050.78 The messages are that internal climate migration could be a reality, but not necessarily a crisis, and that migration can be a sensible climate change adaptation strategy if managed carefully and supported by good development policies and targeted investments. The effects of climate change on migration are largely uncertain because migration is driven by complex multicausal processes, which also include social, economic, political, and demographic dimensions. These dimensions impact on each other and can be driven by the effects of climate change. The uncertainty is compounded by the fact that refugees fleeing conflict, war, or persecution are protected by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.79 By contrast, no international law recognises climate refugees, who are mostly seen as searching for better economic conditions. The World Bank report is confined to internal displacement, which limits its scope. For Bangladesh, a country considered to be at the front line for climate change effects, the World Bank projects that by 2050 there will be 13·3 million climate migrants (surpassing the number of other internal migrants).78 In panel 1, this projection is tested with use of detailed census data from 2001 to 2011. Migration attributed to hydrometeorological hazard risks from all causes are projected up to 2050, exceeding the World Bank figure of 13·3 million internal climate migrants. Therefore, as with northern China, the combination of global climate change and local anthropogenically driven environmental degradation could trigger substantial increases in migration. In our analysis, there was no automatic assumption for Bangladesh that climate change will cause mass migration, but rather that mass migration is occurring now and will increase, projected from current trends with large scale census data.

Panel 1. Projection for internal migrant numbers for Bangladesh by 2050.

The 2050 projection for internal migrants in Bangladesh was driven by hydrometeorological hazard risks under certain assumptions of social and political developments. Three different scenarios based on the combination of two development pathways and two climate trajectories were modelled by the World Bank.78 The modelling included three environmental variables: water stress, crop failure, and sea level rise, with a gravity model based on distance and attractiveness of the destination compared with the source area. The report defines climate migrants as people who have moved from their place of origin for at least 10 years and travelled over 14 kilometres within country because of climate change. The report aims to present a plausible range of outcomes rather than precise forecasts. The projection is based on a single model but has positive aspects such as the inclusion of socioeconomic factors, the choice of slow onset climate change variables, the use of whole globe decadal changes, and that downscaling can easily be achieved. The modelling was calibrated by the highest resolution population census data available at that time. The World Bank report projects that by 2050 there will be 13·3 million climate migrants in Bangladesh based on a pessimistic-realistic reference scenario with high emissions and unequal development.

To test the World Bank projection, the 2011 population and housing census data were collected from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. This database was prepared from household surveying in Bangladesh with a questionnaire that covered the respondents’ household characteristics, demography, migration details, and economic activities among others. 50 districts of 64 in Bangladesh were identified as vulnerable to hydrometeorological hazard risks: flooding and river erosion (23 districts); cyclones and storm surges (19 districts); and drought and groundwater depletion (8 districts). Some districts are affected by multiple hazards. Subsequently, the total number of life-time (greater than 10 years) and inter-district migrants (travelled more than 14 kilometres away) was identified in each district. The migrants constitute about 9%, 12%, and 5% of district-wise total population categorised according to flooding and river erosion, cyclone and storm surge, and drought and groundwater depletion as reasons to migrate. They were then filtered by selecting only people migrating from rural areas, on the basis of an assumption that the adaptive capacity to climate change is lower in rural communities in Bangladesh because of a lack of development and poverty. They constitute about 8%, 11%, and 4% respectively. After applying these filters, it is possible to assess the number of internal migrants attributed to hydrometeorological hazard risks in Bangladesh and whether this figure is compatible with the local context. This assessment is made by analysing primary data collected through actual field surveying under the supervision of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

4·07 million internal migrants were identified for the period of 2001–11, migrating because of these hydrometeorological hazard risks. They represented about 4% of the country’s total population and 41% of the total migrant population of flooding hit districts, 42% of the total migrant population of cyclone hit districts, and 31% of the total migrant population of drought hit districts. By considering Bangladesh’s population growth rate (varying between 0·22–1·00%) and a similar scenario (without new climatic and development interventions) up to 2050, it can be estimated that the total number of internal migrants attributed to hydrometeorological hazard risks will be 19·4 million, which will surpass the World Bank projection of 13·3 million internal climate migrants by 2050. However, it cannot be confirmed that these hydrometeorological hazard risks (eg, river erosion and groundwater depletion), and their frequency and intensity are attributed to climate change.77 While our analysis of primary data suggests that a greater number of people will potentially be affected than the World Bank report projects, it does not validate their projections for internal climate migrants.

Political, cultural, environmental, and structural determinants of migration and health

Political determinants of health

Migration has become highly politicised, especially as some politicians try to curry electoral favour by migrant-blaming and undermining the welfare state. Stigmatising rhetoric has meant that the rights of migrants are under attack by the same structures and processes that are supposed to protect them. This occurs both in their country of origin, potentially leading some to move, and during their migration journey. The views, words, and actions of individuals in power both instigate discrimination and restrict access to education, work, justice, and health. The term fake news has recently been used to describe inaccurate information deliberately created or used to mislead. In a world of social media and populist discourse, fake news is used against migrants to undermine trust and divide communities. A previous Lancet Commission on Global Governance80 outlined the major influences and governance deficits that affect health and the power disparities governing health inequity. This previous Commission highlighted how the goals of the health sector, which are inclusive towards better health for all, commonly come into policy conflict with the interests of influential global actors such as states and transnational corporations who prioritise national security, sovereignty, and economic goals.80 When considering the health of migrants in light of the Global Governance report, the convergence of health and migration is situated at the heart of these opposing governance goals. For example, the Global Governance Commission highlighted democratic deficits, or the insufficient participation of civil society, health experts, and marginalised groups, in the decision making process.80 Migrants often experience exclusion, and despite their participation as workers, consumers, and investors in the economy, they are frequently left out of democratic processes. The previous Commission report80 also indicated that these democratic deficits are compounded by weak or absent government or public accountability mechanisms to fix the failings in this exclusionary system. Moreover, the authors point out the leadership vacuum on health, which is particularly true for migrant health.80 For instance, in the UN system, these global concerns cross thinly through many UN mandates with no clear leadership or coordination with all relevant external actors (eg, civil society, philanthropic organisations, the media, business, and academia). With these profound governance gaps, voices are few and far between to combat the highly charged political rhetoric that demonises migrants.

Culture, ethnicity, and identity

Understanding issues of culture, ethnicity, and identity is crucial for achieving equity in health, including migrant health.81 Past and present migration dynamics have contributed substantially to the cultural and ethnic diversity of many societies, highlighting the importance of the cultural dimensions of health and medical care. Culture can be outlined as a linked group of customs, practices, and beliefs jointly held by individuals, social networks, and groups. These factors help define who they are, where they stand in relation to those within and beyond the group, and give meaning and order to life. Anthropologists describe culture as “a process through which ordinary activities and conditions take on an emotional tone and a moral meaning for participants”;82 this definition includes perceptions, beliefs, and practices related to health, suffering, and disease. Culture is thus never static but evolves in relation to a range of social, economic, and political factors, and experiences of individuals and groups.

Both migration and culture are processes that define an individual’s identity and are dynamic in nature. Migration and living as a migrant in transit or in a host community entails multiple occasions and stimuli for cultural adaptation and change, on individual and collective levels. Identity can initially be based on one’s place of origin (eg, ethnicity, nationality). As a migrant, aspects of oneself are regularly reshaped as new identities emerge and new labels are imposed (eg, migrant, foreigner, undocumented). New locations raise challenges and individuals develop strategies to respond to opportunities or constraints, including how they care for their own health and that of their family, and how they interact with health systems. On arrival at a destination, assimilation and acculturation could alter their risk profile to mirror patterns of local residents or their fellow migrants. Independent of specific ethnicity or country of origin, this change in risk profile could mean higher morbidity due to the deleterious interaction of multiple adverse structural factors, including marginalisation, poverty, the effect of immigration laws and legal status, and poor access to care.83 Analysing the dominant discourse in host countries around migrants helps us to understand how these populations tend to be othered. The questioning by the general population and governments of the deservingness of some groups of migrants for health care has eventually supported actual practices and structures of exclusion.84 Such measures are both fuelled by and contribute to the anti-migration environments, which make individuals feel uncertain about their future, their safety, and the security of their family.

At all stages of the migration process, individuals and groups could be affected by the toxic consequences of social exclusion and discrimination on the grounds of ethnicity, race, nationality, or migrant status. For some migrants, ethnic discrimination or persecution is their reason to leave their place of origin. Subsequently, in transit or in receiving countries, migrants are often subject to pejorative discourses fed by cultural stereotypes and racism. The creation of group identity through distinct cultural artefacts, language, and an assumed common origin or history is an essential feature of culture. However, this diversity can be used as a tool for discrimination, which can be created or increased by individuals who seek to divide communities. Divisive discourse has detrimental consequences, including the impact of raising unfounded fears of increased infectious diseases, violence, and demands on health resources within the host group, a situation well known from past and recent history. Migrants’ burden of discrimination is often doubled as they carry group characteristics that might be associated with additional prejudice and exclusion, for example related to intersectionality with gender or disabilities.

Discrimination towards migrants is commonplace and often conflated with racism. Anti-migrant discrimination and racism overlap, sharing features of prejudice against the other, which are forms of xenophobia but distinct entities. Racism is based on the belief that one race or ethnicity is superior, justifying discriminatory actions. Anti-migrant discrimination is directed against migrants and tends to be a combination of prejudice against the other with fear over the loss of something to the migrant (eg, a job, a service). Crucially, discrimination against migrants is usually racism; that is, it is directed towards people who appear physically or culturally different. This racism can occur not only between the migrant and host community but also between one migrant group and another.85,86 Why is this distinction important? In political discourse, racism is usually socially prohibited and sometimes illegal. Discrimination against migrants, however, is considered acceptable for many and is commonly used in populist rhetoric. Anti-migrant language is a tool that provides the opportunity to divide populations on ethnic grounds to advance the majority view and to mobilise fear and hatred. For example, in September 2015, in an interview to Jornal Opção, the now elected Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro described migrants from Bolivia, Haiti, Senegal, and Iran as "the scum of the world and their children are arriving in Brazil, as if we didn’t have enough problems to solve".87 When Viktor Orban, the Prime Minister of Hungary, was speaking about migrants in 2018 he stated that, "we do not want our own colour, traditions and national culture to be mixed with those of others".88 In the USA, anti-immigrant policies are associated with higher amounts of perceived discrimination in migrant and non-migrant Latino groups, providing a basis for the unequal treatment of both migrant and ethnic minority groups.89 A further study from the USA showed the effects on health; areas with higher anti-immigrant prejudice were associated with increased mortality generally among minority ethnic groups, but the migrants themselves had lower mortality.90 This could also have intergenerational consequences. A prominent raid against Latino migrants, in which 900 agents of the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested 389 employees in a meat-processing plant in Iowa in 2008, was associated with subsequent poorer perinatal outcomes (increased risk of low birthweight) among members of the Latino community.91 An example from the UK is the so-called hostile environment towards migrants created by the Conservative government leading to migrants and British citizens being denied health care. This hostile environment was recently highlighted in the Windrush scandal in 2018, in which British citizens who came to the UK from the Caribbean more than 45 years ago were deported, denied re-entry, lost jobs and accommodation, and were denied rights and benefits.

The sociopolitical context that leads to inequalities in health creates an accumulation of disadvantage throughout the lifecycle, and potentially over generations. Migrant related discrimination is a profound determinant of health, especially mental health and social wellbeing. Studies have shown the substantial mental health implications of living in a state of persistent unpredictability and uncontrollability over one’s future.92 Fear of deportation, discrimination, and targeted condemnation can influence a migrant’s willingness to seek care and maintain follow-up appointments, including to receive medical test results and follow treatment regimens. Studies indicate that the wider consequences of discrimination are substantial. It is estimated that Australia lost 3·02% of GDP (AUS$37·9 billion) over the period 2001–11 as a result of individuals experiencing some form of racial discrimination.93

Various countries have implemented interventions to address discrimination. For example, Canadian schools have implemented cross-cultural youth leadership programmes and anti-racism courses to equip students and staff to deal more effectively with racism.94 In South Africa, the Roll Back Xenophobia programme used community radio to help combat negative stereotypes of migrants and promote social inclusivity.95 However, efforts to raise awareness of and support the needs of particularly at-risk migrant communities have an uphill battle against nationalist forces, exclusionary systems, parsimonious resourcing, and service-level biases.

Environmental influences and hazards

Extreme environmental events and ensuing disasters can cause displacement of populations. These could be naturally occurring hazards, such as tsunamis, floods, earthquakes, or volcanic eruptions; pandemics of infectious diseases; or conflict and disaster, all of which form a complex driver of both internal and international migration. Importantly, the most substantial components of risk in a disaster are the vulnerability and exposure, rather than the environmental hazard itself.96 In this context, vulnerability refers to the susceptibility of an individual or population to the adverse effect of the hazard; the components of which are physical, social, economic, or environmental. Although disasters can result in an increase in vulnerability, they are also a consequence of the underlying vulnerability of communities, infrastructure, and processes because of poor preparation and mitigation.

The increase in extreme weather events has been linked to anthropogenic climate change,75,97 but global disaster deaths have reduced as a proportion of the population. This reduction is attributed to progress in Disaster Risk Reduction actions98 reducing the vulnerability of communities, infrastructure, and health-care systems, and through the establishment of early warning systems. Reactive policies to a crisis that fail to address vulnerability can amplify the social, economic, and environmental drivers that turn natural hazards into large scale disasters.99 The majority of disaster deaths occur in fragile and conflict-affected states where Disaster Risk Reduction is almost absent.100 Disaster Risk Reduction aims to increase resilience and reduce the risk of disasters.

Large disasters typically cost between 0·2 and 10·0% of annual GDP depressing the economy101 and these costs could be considerably higher for the lowest income countries. Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, economic losses equalled GDP.102 Large disasters can exacerbate economically driven migration trends, in the medium to longer term from rural to urban areas103 and internationally.104 However, for localised disasters, where effective aid equals disaster losses, there might be no net migration.105 Evidence from a longitudinal study over 15 years in Indonesia showed that mostly permanent migration generally did not occur in response to disasters, with the exception of landslides.106 However, there is contrasting evidence from the Caribbean islands, which had substantial post-disaster international migration, and tsunami affected Japan where large numbers of local working-age people and families from the Tohoku coast have permanently relocated to Tokyo and other large cities.107 Rising sea levels are likely to cause permanent migration of coastal populations in developing countries with the lowest likelihood of protection (eg, coastal defences), however the people living in these settings have strong abilities and desires to make their own mobility decisions.108 Evidence also shows migration into disaster areas after the disaster in response to government programmes to create jobs or as a result of economic migrants filling the jobs of displaced people. These inward migrants have heightened susceptibility to environmental conditions owing to lower social capital and poorer disaster awareness.

Slow-onset changes in land use and availability due to sea level rise, coastal erosion, precipitation, or agricultural degradation and sector loss will influence the pre-existing economic drivers of permanent migration.109 These changes might be caused by human interference, for example overuse of land or deforestation that renders the land infertile. Drought is a common cause of migration. For example, the drought in Odisha, India in 2001 resulted in 60 000 people migrating, mostly to the adjoining state of Andhra Pradesh in search of employment.110 Migration involves substantial costs and the people with fewest resources have the least capacity to move away, and so are the most vulnerable to harm. Furthermore, environmental change has the potential to even further diminish people’s resources, exacerbating the vulnerability of a population. A resulting sub-section of the population, with the least ability to move, can become trapped.111 This non-migration influenced by environmental change is of great humanitarian concern.

It is essential for areas at high risk of natural disasters to develop strong Disaster Risk Reduction actions to mitigate future potential hazards and minimise mortality. An example of where Disaster Risk Reduction is important are the Rohingya settlements in Bangladesh. The Rohingya are the world’s largest stateless population, stripped of citizenship in 1982 by the government of Myanmar. In late August 2017, renewed violence by the military of Myanmar spurred a rapid mass exodus of Rohingya (655 000 people in 3 months) to the south-eastern region of Bangladesh.112 These locations, such as Cox’s Bazar and Bandarban, are very susceptible to cyclones, flash flooding, and rainfall-induced landslides. This risk coupled with the temporary, makeshift shelters often created by cutting into mud hillsides render the Rohingya highly vulnerable to environmental disasters. There is an urgent need to conduct multihazard vulnerability mapping of the refugee camp and surrounding areas, conduct mapping of human mobility patterns, improve drainage capacities of refugee settlement areas, develop evacuation and relocation processes, examine resilience of existing health-care centres to potential hazards, and generate a post-disaster plan.113

Education for migrant children and adolescents

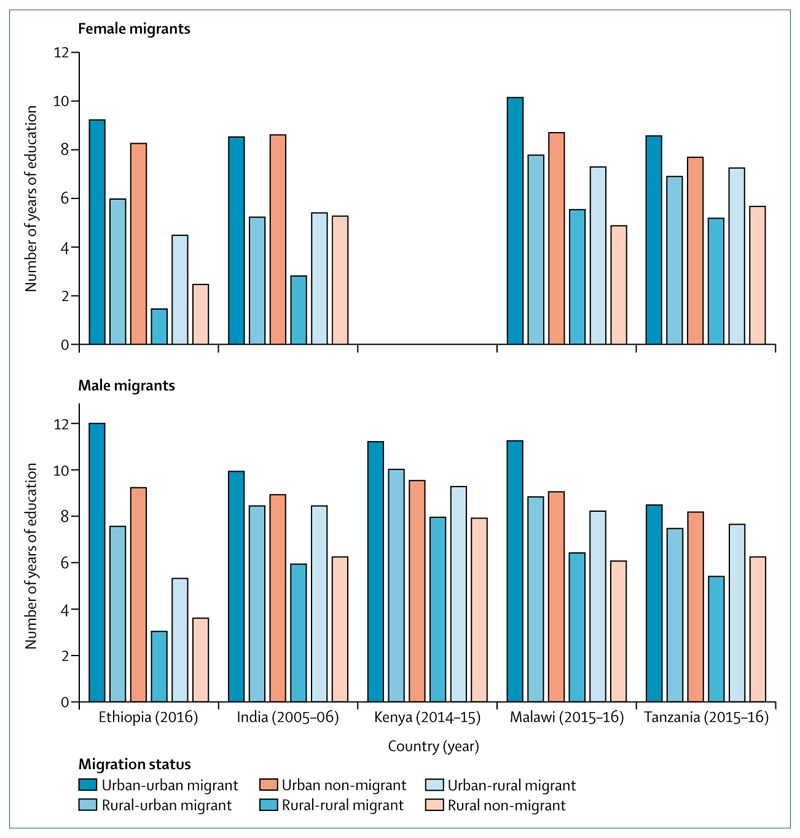

Education is essential for children and adolescents and is a determinant of future health and wellbeing. Education includes formal schooling, and acquisition of cognitive, social, and other soft skills that foster intellectual and social growth. Migration disrupts a child’s formal education, including difficulties accessing school. These difficulties have the potential to result in lost generations of educated adults, particularly for irregular child migrants and unaccompanied children. In a study of access to public schools in 28 developed and developing countries across the world, 40% of developed and 50% of developing countries did not allow immediate access to irregular migrant children.114 Migrant children might also be excluded from school in some countries because they have not undergone health screening,115 or they might miss school days because of their poor access to services to treat even simple illnesses. Migrant children in school can have poor educational attainment or decide to drop out because of language barriers, unsuitable materials, or teachers who are inadequately trained to support student integration. For migrant children with disabilities, obtaining an education can be especially challenging because few countries will prioritise adapting education and school structures or providing the necessary staff to ensure that children with disabilities can obtain a good education.116 Migrant students are more likely than native students to be placed in groups with lower curricular standards and lower average performance levels.117 An analysis of Demographic and Health Surveillance data from Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Malawi, and Tanzania on the association between mean number of years of education and internal migration status indicates that, on average, migrants have more years of education than non-migrants, with the exception of rural-rural migrants (figure 7). The differences in the educational attainment of female migrants and male migrants is notable among all groups, with males more likely to stay in school longer, especially among urban residents.

Figure 7. Weighted mean number of years of education by internal migration status35–39.

Internal migration in China is subjected to the Hukou system, which is a household registration system that establishes service entitlements by internal divisions on the basis of residency.118 These regulations can mean that internal Chinese migrants do not have access to their own public education system, or other services, because the child is not registered in the region that they live.119

However, where migration is managed well, children can integrate quickly into a new system with younger children assimilating particularly well. All children and adolescents, regardless of their status, should have access to education. According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child,120 states are responsible for making primary and secondary education available and accessible to all children, regardless of migration status. Primary education should be free and compulsory, and states should take progressive steps to make secondary education free as well. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities121 also requires that governments ensure equal access to basic services including education for people with disabilities. A practical example of the inclusion of child migrants is the Reaching All Children with Education programme in Lebanon, which sought to integrate large numbers of migrant Syrian children into its public school system, while simultaneously improving access for Lebanese children.122 The programme increased the number of school places, waived fees, and provided education grants with encouraging results emerging.122

Health and safety of labour migrants

Migrant workers’ earnings can sustain households and influence entire economies. For some labour migrants (primarily highly skilled individuals with sufficient education, employment, financial, or citizenship credentials), migration poses few risks. In these circumstances, migration is generally advantageous for livelihoods, health, and wellbeing. However, the majority of labour migrants are less well situated, often originating from LMICs and seeking work in response to financial or safety needs.

Distress migration or economic migration puts migrant workers at particular risk of unsafe transit and pressures, sometimes with coercion to engage in unsafe work conditions. Low wage labour migration is closely linked to globalisation and supply and demand, especially for cheap labour. Migrant workers in these jobs are often among the most invisible of migrant populations. Not only are they likely to work in informal or even illegal sectors but they are also less likely to take part in the formal economy, engage with the local community, or use official resources. Their safety is also often hindered by poor social, economic, or legal status to assert their rights.

Labour migrants rarely migrate on their own without the assistance of labour intermediaries, which includes both formal agencies and informal migrant networks. Labour brokers have a fundamental role in linking individuals to jobs, however it is not unusual for recruiters to charge exorbitant fees, causing migrants to incur substantial debt. Recruitment agents, including from a migrant’s own social network, often facilitate third-party contractual arrangements, day labour, piece-work, and similar precarious employment and pay arrangements. These arrangements lead to long hours, exhaustion, and serious health hazards. For example, Bolivian migrant workers have been led to seek jobs in harsh working conditions in textile workshops in Argentina through their social networks.123

Although labour migration has served to advance global markets and offer greater livelihood opportunities, there is growing recognition of the often exploitative and hazardous nature of many work sectors and their adverse effects on health and wellbeing, particularly in emerging economies. The health and wellbeing of migrant workers is directly related to their working and living conditions and influenced by broader social conditions (table). Harmful labour situations are not uncommon for many migrants, especially individuals in low wage sectors. Employment destinations frequently involve hazardous working arrangements, dangerous tasks, and unsafe or unhygienic living conditions. For example, commercial fishing is considered to have some of the most hazardous work conditions—especially in situations of exploitation or so-called sea slavery. A study among trafficking survivors in the Thai fishing industry reported higher injury rates than non-trafficked fish industry workers. Additionally, in the fishing industry more trafficked workers were subjected to severe violence, compared with non-trafficked workers (table).124

Table.

Low wage labour sectors and associated occupational hazards among migrant workers (see appendix for full list of references)

| Examples of occupational hazards and harm | Migrant health study findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex work | Poor condom negotiation or use can cause sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancy; sexual violence and confinement can cause anxiety disorders and depression | Migrant female sex workers in Benin, Ethiopia, and Kenya are at greater risk of HIV than non-migrant sex workers and higher risk of acute sexually transmitted infections in all settings |

| Construction | Work at heights can cause fatal falls and disabilities; heavy lifting can cause musculoskeletal problems; poor personal protective equipment can cause respiratory disease, dermatitis, and eye injury | In the USA, Latino construction workers were nearly twice (1·84, 95% CI 1·60-2·10) as likely to die from occupational injuries as their non-Latino counterparts |

| Manufacturing (eg, textiles) | Repeated bending and fixed postures can cause musculoskeletal damage and pain; sharp instruments can cause puncture wounds; dust particles can cause silicosis | In Malaysia, 64% of migrant workers had musculoskeletal pain caused or worsened by work compared with 28% of Malaysian non-migrant manufacturing workers |

| Commercial fishing | Environmental exposures (sun, cold, rain) can cause skin cancer, dehydration, frostbite; long hours and weeks with no break can cause exhaustion and pneumonia; unstable fishing vessels and inadequate life vests can cause drowning; fishing net and knife hazards can cause deep cuts and lost limbs | Survivors of trafficking working in the Thai fishing industry reported higher injury rates (47%) than non-trafficked fish industry workers (21%); 54% of trafficked fish industry workers experienced severe violence versus 10% of non-trafficked fish industry workers |

| Agriculture | Pesticide exposure can cause toxicity; environmental exposures (heat, cold, mosquitoes) can cause dehydration, kidney failure, headaches, and malaria; heavy lifting and bending can cause repetitive injury syndromes | In one greenhouse in Oman, 95% of workers were migrants; poor practices related to pesticide use resulted in numerous health problems, such as skin irritation (70%), headaches (39%), and vomiting (30%) |

| Domestic work | Physical, sexual, and verbal abuse, and social isolation can cause depression, anxiety, and suicide; extensive working hours and food deprivation can cause exhaustion; repeated lifting, bending, and reaching can cause musculoskeletal strain; chemical cleaning agents, cooking, ironing, and knives can cause skin damage and burns | A 2-year study in Kuwait found that hospital admission rates for domestic workers (93% from India, Philippines, and Sri Lanka) were 1·86 times higher than for Kuwaiti women (non-domestic worker control group); stress-related disorders were more common (49% vs 22%) in housemaids (of whom a majority are migrants) than Kuwaiti women |