Abstract

Cyclic GMP is produced by enzymes called guanylyl cyclases, of which the membrane-associated forms contain an intracellular pseudokinase domain that allosterically regulates the C-terminal guanylyl cyclase domain. Ligand binding to the extracellular domain of these single transmembrane-spanning domain receptors elicits an increase in cGMP levels in the cell. The pseudokinase domain (or kinase-homology domain) in these receptors appears to be critical for ligand-mediated activation. While the pseudokinase domain does not possess kinase activity, biochemical evidence indicates that the domain can bind ATP and thereby allosterically regulate the catalytic activity of these receptors. The pseudokinase domain also appears to be the site of interaction of regulatory proteins, as seen in the retinal guanylyl cyclases that are involved in visual signal transduction. In the absence of structural information on the pseudokinase-guanylyl cyclase domain organization of any member of this family of receptors, biochemical evidence has provided clues to the physical interaction of the pseudokinase and guanylyl cyclase domain. An α-helical linker region between the pseudokinase domain and the guanylyl cyclase domain regulates the basal activity of these receptors in the absence of a stimulatory ligand and is important for stabilizing the structure of the pseudokinase domain that can bind ATP. Here, we present an overview of salient features of ATP-mediated regulation of receptor guanylyl cyclases and describe biochemical approaches that allow a clearer understanding of the intricate interplay between the pseudokinase domain and catalytic domain in these proteins.

Abbreviations

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- cGMP

guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- CNP

C-type natriuretic peptide

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

1. Introduction

Guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) was first discovered in rat urine in 1963 (Ashman, Lipton, Melicow, & Price, 1963). Levels of this second messenger are maintained inside the cell by conversion of GTP to cGMP by guanylyl cyclases and hydrolysis of cGMP to GMP by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Mammals express four soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) subunits (α1, α2, β1, and β2) and seven membrane-spanning or receptor guanylyl cyclases (rGC), namely, GC-A, GC-B, GC-C, GC-D, GC-E, GC-F, and GC-G (Potter, 2011a). In primates, GC-D and GC-G exist as pseudogenes, with multiple insertions and deletions accumulated during the course of evolution, that would generate truncated and/or non-functional proteins (Manning, Whyte, Martinez, Hunter, & Sudarsanam, 2002). The functions of these receptors are determined by the tissue and cell types in which they are located. They have essential roles to play in phototransduction, intravascular blood volume, vascular tone, bone development, and gut physiology (Potter, 2011a). rGCs can be activated by diverse peptides, but the extracellular ligands for rGCs involved in visual signal transduction are unknown.

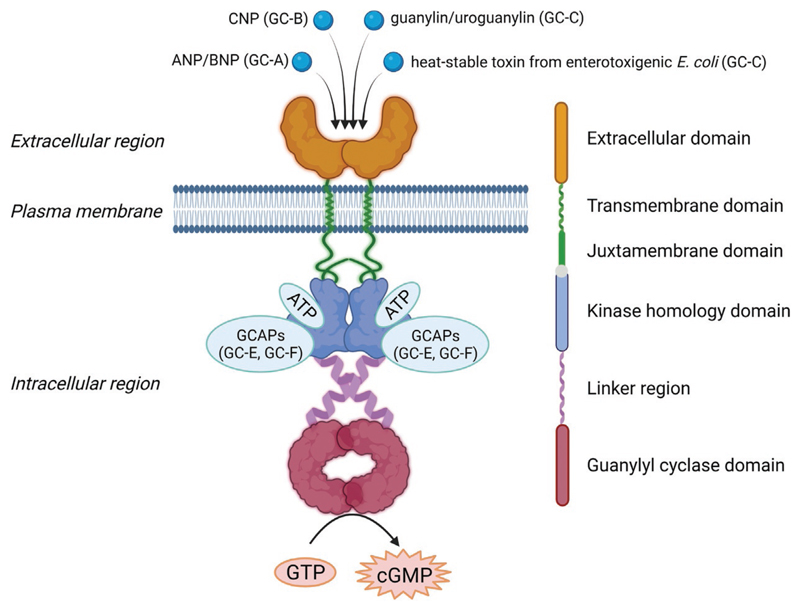

Receptor GCs are believed to function as homodimers because of the requirement for dimerization of the guanylyl cyclase domain for catalytic activity (Liu, Ruoho, Rao, & Hurley, 1997; Thompson & Garbers, 1995). These receptors have a complex multidomain organization that includes an N-terminal, extracellular domain required for ligand binding, a single transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane domain, followed by the pseudokinase or kinase-homology domain (KHD) responsible for allosteric regulation of the receptor (Potter, 2011b). Indeed, the first recognition of a "pseudokinase-like domain" in a protein was noted by David L. Garbers in a study related to the cloning of a plasma membrane-associated guanylyl cyclase from the sea urchin (Singh et al., 1988). The KHD is connected to the catalytic guanylyl cyclase domain through a linker region (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis of receptor GCs suggests coevolution of the KHD and its associated cyclase domain, and conservation of the sequence and length of a predicted helical region between these two domains (Biswas, Shenoy, Dutta, & Visweswariah, 2009).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of overall domain organization in receptor guanylyl cyclases. Receptor guanylyl cyclases function as homodimers where each monomer possesses six domains, namely, an N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) for ligand binding, a single membrane spanning transmembrane domain followed by adjacent juxtamembrane domain, a pseudokinase or kinase homology domain (KHD) which allosterically regulates the receptor, and an α-helical linker region connecting the KHD with the catalytic guanylyl cyclase domain. GC-C has an additional C-terminal domain of ~60 amino acids that helps in anchoring to the cytoskeleton (not shown). Numbers in the bracket indicate the approximate length of each domain (GC-C has been used as a reference). Diverse extracellular ligands can bind to the extracellular domain, and the ligands thus far identified are shown. The pseudokinase domain also serve as a binding site for guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAPs) which interact with Ca2+ to regulate guanylyl cyclase activity. ATP binds to the KHD of all rGCs.

A broader phylogenetic analysis of the KHDs of rGCs with protein kinases, in general, show that they branch close to tyrosine kinases (Fig. 2) (Kwon et al., 2019; Letunic & Bork, 2021). Shown in Fig. 3 is an alignment of the KHDs of rGCs along with Src tyrosine kinase, where critical blocks of residues required for kinase activity are shown. The KHD in these receptors are considered pseudokinases since they lack the aspartate residue present in the catalytic loop of classical protein kinases that binds the Mg2+ ion required for catalysis and transfer of the γ-phosphate of ATP to the kinase substrate (Knape & Herberg, 2017).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of human kinases. Phylogenetic analysis of 497 kinases from the human genome classifies them into 9 groups, namely, PKA, PKG, PKC like kinases (AGC), Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase (CAMK), casein kinase 1 (CK1), CDK, MAPK, GSK and CDK family (CMGC), NIMA-related kinase (NEK), receptor guanylyl cyclase (RGC), Ser-Thr specific protein kinase (STE), tyrosine-kinase like (TKL), and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). The receptor guanylyl cyclases cluster as a separate class close to receptor tyrosine kinases. The tree has been prepared using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de) (Letunic & Bork, 2021).

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of kinase homology domains (KHDs) from human and mouse receptor guanylyl cyclases (rGCs) with Src tyrosine kinase. Comparison of rGCs, from human and mouse, with Src tyrosine kinase. Mutations in the 3 motifs responsible for kinase activity (highlighted in black box) are shown. The Lys residue in the VAIK motif and Asp residue in the DFG motif, critical for interacting with ATP and metal ion is conserved across all rGCs. However, the Asp residue in the HRD motif responsible for phosphotransfer activity of a kinase is mutated to Asn (in GC-A), Ser (in GC-B) or Arg (in GC-C, GC-E, and GC-F).

Several studies have described the critical role of the KHD in regulating the activity of these receptors (Bhandari et al., 2001; Potter, 2011a). Consequently, multiple human disorders are associated with mutations in the KHD (Table 1). Therefore, understanding the regulatory mechanisms of the KHD will aid in the design of molecules that either activate or inhibit the receptor as required. It is important to note that structural information is only available for the ECD of GC-A (Ogawa, Qiu, Ogata, & Misono, 2004; Padayatti, Pattanaik, Ma, & van den Akker, 2004). Therefore, the pseudokinase domain of these receptors and residues involved in binding ATP have so far been characterized only through mutational and biochemical analyses.

Table 1. Mutations in the pseudokinase domain of receptor guanylyl cyclases associated with human disease.

| GC-B mutations | ||||

| c.1589C>A | A530D, A533D | |||

| c.1636A>T | N546Y, N549Y | |||

| c.1670G>A | R557H, R560H | |||

| c.1673T>C | I558T | rs751324720 | ||

| c.1684C>T | R562W | rs566096931 | ||

| c.1714A>T | R572a | rs1554673485 | ||

| c.1739C>G | T580S | rs1131692010 | ||

| c.1801C>T | R601C | rs1563988849 | ||

| c.1802G>A | R604H, R601H | |||

| c.1802G>T | R601L | |||

| c.1813C>T | Q605a | rs969576919 | ||

| c.1839C>G | I616M, I613M | |||

| c.1844T>G | L615W, L618W | |||

| c.1922C>T | S641L, S644L | |||

| c.1948T>G | C650G, C653G | |||

| c.1963C>T | R655C | rs587777596 | ||

| c.1968dup | V657fs | rs1554673888 | ||

| c.2065C>T | P689S, P692S | |||

| c.2105T>A | M702K | rs200129431 | ||

| c.2143C>T | Q715a | |||

| c.2150T>C | I717T, I720T | |||

| c.2162_2172del | S721fs | Trident hand | Limb undergrowth | Growth delay | Craniosynostosis syndrome | rs1057518817 | |

| c.2246G>A | R749Q, R752Q | Short stature with nonspecific skeletal abnormalities | ||

| c.2252G>A | S751N | |||

| c.2260C>T | R754W | rs371968545 | ||

| c.2261G>A | R754Q | rs763488261 | ||

| c.2266C>T | Q756a, Q759a | Intellectual disability | Epiphyseal chondrodysplasia, miura type | ||

| c.2299C>T | R767a, R770a | Short stature with nonspecific skeletal abnormalities | ||

| c.2302T>C | C768R | rs1057519333 | ||

| c.2321C>T | A774V | rs369154896 | ||

| c.2327G>A | R776Q | rs780293535 | ||

| c.2351G>A | G784D | |||

| c.2359C>T | R787W | rs114147262 | ||

| c.2360G>A | R787Q, R790Q | |||

| c.2362C>T | R788C, R791C | |||

| c.2363G>A | R788H, R791H | |||

| GC-C mutations | ||||

| c.1540A>G | I514V | |||

| c.1544T>C | L515P | |||

| c.1616T>C | I539T | Not provided | ||

| c.1798G>A | G600R | Intestinal obstruction in the newborn due to guanylate cyclase 2C deficiency | ||

| c.1997A>G | Y666C | |||

| c.2008G>A, c.2728T>C |

A670T, C928R | rs587784572, rs587784573 |

||

| c.2067T>G | N689K | Not specified | rs138497004 | |

| c.2086G>T | E696a | rs1057520701 | ||

| c.2155G>C | E719Q | Meconium ileus | rs895214647 | |

| GC-E mutations | ||||

| c.1608G>A | M536I | Cone-rod dystrophy 6 | Leber congenital amaurosis 1 | ||

| c.1615A>G | I539V | Not provided | rs61749753 | |

| c.1618C>T | R540C | Not provided | rs61749754 | |

| c.1619G>T | R540L | |||

| c.1624G>A | G542S | |||

| c.1633C>T | Q545a | rs1290420698 | ||

| c.1660G>A | V554I | |||

| c.1672G>A | D558N | rs188568530 | ||

| c.1694T>C | F565S | rs61749755 | ||

| c.1707G>T | Q569H | |||

| c.1713A>G | I571M | rs886043672 | ||

| c.1717A>G | I573V | rs61749756 | ||

| c.1720C>T | R574C | rs137853897 | ||

| c.1721G>A | R574H | rs560270873 | ||

| c.1724C>T | P575L | rs28743021 | ||

| c.1758G>T | E586D | |||

| c.1763G>A | R588Q | |||

| c.1766A>G | H589R | |||

| c.1771A>G | N591D | |||

| c.1773del | N591fs | rs794727952 | ||

| c.1774G>A | V592M | |||

| c.1804C>T | R602W | |||

| c.1806_1830del | A604fs | rs63749078 | ||

| c.1817G>A | G606D | |||

| c.1825G>A | A609T | |||

| c.1828C>A | L610I | |||

| c.1841A>G | N614S | |||

| c.1852G>A | V618I | |||

| c.1868C>T | T623M | |||

| c.1870C>T | R624W | |||

| c.1871G>A | R624Q | |||

| c.1877C>G | S626C | |||

| c.1887C>A | D629E | |||

| c.1901G>C | R634T | |||

| c.1904A>G | E635G | |||

| c.1924T>G | F642V | |||

| c.1937T>C | L646P | |||

| c.1943T>C | L648P | |||

| c.1957G>A | G653R | Not provided | rs61750160 | |

| c.1964G>A | R655K | Retinal dystrophy | ||

| c.1972C>T | H658Y | rs1598149154 | ||

| c.1974C>A | H658Q | |||

| c.1978C>T | R660a | rs61750161 | ||

| c.1979G>A | R660Q | rs61750162 | ||

| c.1984G>A | V662M | |||

| c.1991A>C | H664P | |||

| c.1992T>G | H664Q | rs1598149187 | ||

| c.1996C>T | R666W | |||

| c.1997G>A | R666Q | |||

| c.2008C>T | R670W | |||

| c.2015G>A | C672Y | |||

| c.2056G>A | G686S | |||

| c.2059C>T | H687Y | |||

| c.2078_2085del | A693fs | rs61750163 | ||

| c.2080C>A | Q694K | rs61750164 | ||

| c.2093C>G | P698R | |||

| c.2101C>T | P701S | rs34598902 | ||

| c.2108C>T | A703V | |||

| c.2122T>C | W708R | rs1064797217 | ||

| c.2129C>T | A710V | rs781725943 | ||

| c.2132C>T | P711L | |||

| c.2164C>T | R722W | rs34331388 | ||

| c.2165G>A | R722Q | |||

| c.2171C>T | T724M | |||

| c.2179G>A | G727S | |||

| c.2182G>A | D728N | |||

| c.2204T>C | I735T | |||

| c.2224C>T | R742C | |||

| c.2234del | P745fs | rs1598149659 | ||

| c.2237A>G | Y746C | rs61750166 | ||

| c.2248G>T | E750a | rs61750167 | ||

| c.2260G>A | E754K | |||

| c.2281C>T | R761W | |||

| c.2290C>T | P764S | |||

| c.2302C>T | R768W | rs61750168 | ||

| c.2303G>A | R768Q | rs750889782 | ||

| c.2312T>A | V771E | |||

| c.2317A>C | M773L | rs61750169 | ||

| c.2318T>C | M773T | |||

| c.2325G>T | Q775H | |||

| c.2335G>T | E779a | rs541299023 | ||

| c.2338T>C | C780R | |||

| c.2345T>A | L782H | rs8069344 | ||

| c.2359T>G | C787G | |||

| c.2377del | E793fs | rs1555635668 | ||

| c.2383C>T | R795W | |||

| c.2384G>A | R795Q | rs61750171 | ||

| c.2384G>T | R795L | Not provided | rs61750171 | |

| c.2393T>G | M798R | |||

| c.2395_2398dup | H800fs | |||

| c.2431G>A | G811S | rs1196292120 | ||

The introduction of a stop codon after the indicated amino acid. Data taken from ClinVar https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/.

2. Allosteric regulation of rGCs by the pseudokinase domain

2.1. GC-A and GC-B

Guanylyl cyclase A (GC-A), also called natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPR-A or NPR1), is activated by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) produced by atria and ventricles, respectively (Potter, 2011b; Suga et al., 1992). GC-A is expressed in the lung, kidney, brain, liver, adrenal, vasculature, adipose, and endothelial tissues and at lower levels in the heart (Bryan et al., 2006; Dickey et al., 2007; Potter, Abbey-Hosch, & Dickey, 2006). Guanylyl cyclase B (GC-B) shows 78% identity to GC-A in the intracellular region and is also called the natriuretic peptide receptor B (NPR-B or NPR2) (Schulz, Green, Yuen, & Garbers, 1990). GC-B is stimulated by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) and enhances long bone growth and oocyte maturation (Koller et al., 1991; Yasoda et al., 1998; Zhang, Su, Sugiura, Xia, & Eppig, 2010). GC-B is highly expressed in the brain, heart, lung, bone, ovary, fibroblast, and vascular smooth muscle cells (Chrisman, Schulz, Potter, & Garbers, 1993; Nagase, Katafuchi, Hirose, & Fujita, 1997; Schulz et al., 1989).

GC-A exists as a homodimer, and ligand binding does not induce further oligomerization (Chinkers & Wilson, 1992). Early on, it was hypothesized that the conformational changes seen in GC-A and GC-B upon ligand binding propagate through the KHD to the catalytic domain. Phosphorylation of the KHD at its N-terminus is essential for ligand-mediated signal transduction from the ECD to the catalytic domain in both GC-A and GC-B, although the identities of the kinases that phosphorylate these receptors remain unknown. The phosphorylated sites have been chemically determined in rat and human GC-A and GC-B. They are Ser487, Ser497, Thr500, Ser502, Ser506, Ser510, and Thr513 (in rat GC-A) and Ser513, Thr516, Ser518, Ser523, Ser526, and Thr529 (in rat GC-B) (Potter, 1998; Potter & Garbers, 1992; Potter & Hunter, 1998a, 1998b; Schroter et al., 2010; Yoder, Stone, Griffin, & Potter, 2010). Prolonged exposure to natriuretic peptides in intact cells, or treatment of membrane fractions with protein phosphatase 2A, reduces the phosphate content of these receptors. This is associated with a loss of natriuretic peptide-dependent guanylyl cyclase activity (Potter & Garbers, 1992). GC-A and GC-B show increased guanylyl cyclase activity (as monitored by cGMP production by radioimmunoassay (RIA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)) in the presence of non-ionic detergents, by unclear mechanisms. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation does not affect detergent-mediated cGMP production (Joubert, Labrecque, & De Lean, 2001; Potter, 1998).

Deleting the pseudokinase domain in GC-A led to a constitutively active receptor that was not stimulated further upon ligand addition. On the contrary, partial deletion of the KHD results in an inactive receptor (Chinkers & Garbers, 1989; Koller, de Sauvage, Lowe, & Goeddel, 1992).

To differentiate the allosteric effects of ATP from its phosphorylation effects, the non-hydrolyzable analog AMP-PNP and dephosphorylation resistant analog ATP-γ-S were used in assays with crude preparations of membranes prepared from cells or tissues (Chang et al., 1990; Gazzano, Wu, & Waldman, 1991; Kurose, Inagami, & Ui, 1987). ATP and AMP-PNP augmented ligand-independent or dependent GC-A activity in vitro when Mg2+ ions (required for the two-metal ion catalysis shown by nucleotidyl cyclases; see below) were provided in assays along with GTP. However, guanylyl cyclase activity was inhibited when Mn2+ ions were provided along with GTP, or assays were performed in the presence of non-ionic detergents (Chang et al., 1990; Gazzano et al., 1991; Kurose et al., 1987).

Detailed enzymatic analyses demonstrated that ATP shifts the kinetics from positive cooperativity in the absence of ATP to classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics in its presence. This results in a 10-fold reduction of the Michaelis' constant for GTP, allowing the receptor to function at physiological concentration of GTP in the presence of natriuretic peptides (Robinson & Potter, 2012). The crystal structure of the ECD of GC-A revealed that ligand binding results in a 24° counter-clockwise rotation in the ECD of one monomer with respect to the other (Ogawa et al., 2004). This conformational change is thought to propagate along the receptor through the KHD and ultimately relay the signal to the catalytic domain to form a functional catalytic domain dimer. Comparison with Src tyrosine kinase shows that the ATP-binding Lys residue in the VAIK motif and Asp residue in the DFG motif of GC-A and GC-B is conserved (Fig. 3). However, the Asp residue in the HRD motif required for phosphotransfer activity is replaced by Asn in GC-A and GC-B (Fig. 3). Alanine substitutions in the VAIK and DYG kinase motifs of GC-A and GC-B did not alter the phosphate content of the receptors or ligand-mediated activation, but prevented the ATP-dependent reduction of Michaelis' constant for GTP (Edmund, Walseth, Levinson, & Potter, 2019). To understand the mechanism of allosteric regulation by ATP, mutations were made to rigidify the regulatory and catalytic spine of the KHD (A533W in GC-A, M571F, and I583W in GC-B). This mimics the stabilization of the spine on ATP binding to protein kinases (Taylor, Meharena, & Kornev, 2019). These mutations increased guanylyl cyclase activity and reduced the Michaelis' constant for GTP, even in the absence of ATP (Edmund et al., 2019).

To determine the effect of ATP on cooperativity, substrate-velocity experiments were performed after deletion of the KHD. The absence of the KHD led to a shift from positive cooperativity to linear kinetics but failed to reduce the Michaelis' constant in the presence of ATP. Therefore, ATP binding to the catalytic domain of GC-A and GC-B is sufficient for its effect on cooperativity, but the reduction of the Michaelis' constant requires ATP binding to the KHD, coupled with ligand binding to the ECD (Edmund et al., 2019).

2.2. GC-C

Guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C; gene GUCY2C) has a similar domain architecture to GC-A and GC-B but possesses a C-terminal domain of 60 amino acids that anchors the receptor to the cellular cytoskeleton (Basu, Arshad, & Visweswariah, 2010). GC-C is predominantly expressed on the apical surface of intestinal epithelial cells and plays an important role in regulating intestinal fluid-ion homeostasis (Arshad & Visweswariah, 2012; De Jonge, 1975a, 1975b; Swenson, Mann, Jump, Witte, & Giannella, 1996). It is stimulated by the endogenous peptide hormones, guanylin and uroguanylin, and exogenous heat-stable enterotoxin (STa) from enterotoxigenic E. coli. STa acts as the super-agonist of GC-C and therefore results in diarrhea in infected individuals (Bose, Banerjee, & Visweswariah, 2020; Schulz et al., 1990). GC-C is also expressed in the kidney, airway epithelium, perinatal liver, stomach, brain, adrenal glands, and reproductive tissues (Forte, Krause, & Freeman, 1989; Jaleel, London, Eber, Forte, & Visweswariah, 2002). GC-C has been reported to exist both as a dimer and trimer (Vaandrager, van der Wiel, & de Jonge, 1993; Vaandrager, van der Wiel, Hom, Luthjens, & de Jonge, 1994). Similar to GC-A and GC-B, ligand binding to the ECD results in elaborate conformational changes along the length of the receptor, which relays the signal to the catalytic domain through the KHD. Unlike GC-A and GC-B, phosphorylation of GC-C is not required for its activity (Vaandrager et al., 1993). Activating protein kinase C using phorbol esters increases the phosphate content and activity of GC-C and results in a down-regulation of GC-C transcripts in colon carcinoma cell lines (Crane & Shanks, 1996; Roy et al., 2001; Vaandrager et al., 1993). In addition, phosphorylation by c-Src tyrosine kinase at the Y820 residue in the catalytic domain inhibits the catalytic activity of GC-C (Basu, Bhandari, Natarajan, & Visweswariah, 2009).

Although the KHD of GC-C lacks a glycine-rich loop typically seen in conventional kinases, a KHD-linker construct, expressed and purified from insect cells, bound ATP-agarose (Bhandari et al., 2001; Jaleel, Saha, Shenoy, & Visweswariah, 2006). Binding was abolished upon removal of the linker region (Jaleel et al., 2006). Thus, residues in the linker region outside the KHD are essential to fold the KHD domain into a structure capable of binding ATP. Homology modeling coupled with mutational and bio-chemical analyses revealed that K516 is the residue responsible for ATP binding and ligand-mediated regulation in GC-C (Bhandari et al., 2001). Failure of a monoclonal antibody to bind to an epitope C-terminal to K516 in the presence of ATP indicated that conformational changes occur in the KHD-linker region upon ATP binding (Jaleel et al., 2006). Ligand-addition to membrane fractions containing GC-C resulted in increased cGMP production in the presence of ATP, with Mg2+ as the metal cofactor in assays (Bhandari et al., 2001; Parkinson, Carrithers, & Waldman, 1994). However, ATP inhibits non-ionic detergent-mediated receptor activation (Bhandari, Suguna, & Visweswariah, 1999). ATP inhibits guanylyl cyclase activity of GC-C in the presence of Mn2+ as a cofactor, and this inhibition was also observed in the K516A mutant receptor (Bhandari et al., 1999). This indicates that ATP can also bind to an allosteric site in the catalytic domain and regulate guanylyl cyclase activity.

Tyrphostins, receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors that bind to the kinase domain of protein kinases, inhibit the catalytic activity of GC-C, suggesting that they may bind to the KHD. However, we showed that these molecules interact with the guanylyl cyclase domain (Jaleel, Shenoy, & Visweswariah, 2004). There is a very high similarity between adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases, with a few substrate-specifying residues determining whether ATP or GTP is used as a substrate (Beuve, 1999). Therefore, tyrphostins may bind to a region in the guanylyl cyclase domain that is the structural homolog of the catechol estrogen binding site in adenylyl cyclases (Steegborn et al., 2005).

2.3. GC-E and GC-F

Guanylyl cyclase E (GC-E) and guanylyl cyclase F (GC-F), also referred to as retinal GCs (RetGC1 and RetGC2, respectively), play a crucial role in phototransduction. GC-E expression has been detected in the retina and pineal gland, while GC-F expression is limited only to the retina (Lowe et al., 1995; Shyjan, de Sauvage, Gillett, Goeddel, & Lowe, 1992; Yang, Foster, Garbers, & Fulle, 1995). Although the domain architecture of GC-E and GC-F are similar to GC-A, GC-B and GC-C, extracellular ligands of GC-E and GC-F have not been identified yet. Instead, 20–24 kDa, soluble, intracellular calcium-binding proteins called guanylyl cyclase activator proteins (GCAPs) regulate the activity of GC-E and GC-F (Dizhoor et al., 1995; Dizhoor, Lowe, Olshevskaya, Laura, & Hurley, 1994; Gorczyca, Gray-Keller, Detwiler, & Palczewski, 1994; Palczewski et al., 1994). GCAPs are associated with the KHD of the cyclases constitutively, and their interaction is determined by the structure of the KHD. Cyclic GMP synthesis is induced by conformational changes in the GCAP/RetGC complex brought upon by Ca2+ binding. These conformational changes are such that the GCAP/RetGC complex produces cGMP only under low calcium concentrations. In contrast, an increase in intracellular calcium levels leads to inhibition of cyclase activity by the GCAPs (Laura & Hurley, 1998). Although GC-E has multiple serine and threonine residues in the kinase homology domain, phosphorylation is not essential for activation of the receptor (Bereta et al., 2010).

ATP enhanced GC-E activity both in the presence and absence of GCAPs (Aparicio & Applebury, 1996; Gorczyca, Van Hooser, & Palczewski, 1994). GC-E activity was increased two-fold in bovine rod outer segments in the presence of ATP, by increasing the Vmax of the enzyme. However, GCAP did not further potentiate activity in the presence of ATP (Gorczyca, Van Hooser, & Palczewski, 1994). Retinal GC is rapidly inactivated at physiological temperatures, and this inactivation could be prevented in the presence of GCAP2, ATP and AMP-PNP (Tucker, Laura, & Hurley, 1997; Yamazaki et al., 2003). This suggested that ATP binding to the pseudokinase domain could occur when the rGCs are bound to GCAPs, and the enhanced activation seen in the presence of ATP is a consequence of stabilization of GC-E. AMP-PNP and ATP-γ-S were more potent than ATP in mediating the increased activation/stabilization (Aparicio & Applebury, 1996). Interestingly, this study showed that an intrinsic protein kinase activity was seen with the purified receptor, though this result has not been confirmed by other investigators.

2.4. Non-primate rGCs: GC-D and GC-G

Guanylyl cyclase D (GC-D) is expressed in the olfactory bulb of rodents (Fulle et al., 1995; Juilfs et al., 1997; Meyer, Angele, Kremmer, Kaupp, & Muller, 2000). Guanylyl cyclase G (GC-G) is expressed in the lung, intestine, skeletal muscle, testes, and at lower levels in the kidney of the rat and mouse (Kuhn et al., 2004; Schulz, Wedel, Matthews, & Garbers, 1998). Carbon dioxide and bicarbonate ions can stimulate both GC-D and GC-G, and uroguanylin has been reported to activate GC-D (Arakawa, Kelliher, Zufall, & Munger, 2013; Chao et al., 2010; Guo, Zhang, & Huang, 2009; Leinders-Zufall et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2009). This is surprising since the sequence similarity in the ECD between GC-D and GC-C is low. GC-D plays an important role in olfaction and enhancing the food preference response in mice in diverse social contexts (Munger et al., 2010; Zimmerman, Nagy, & Munger, 2020).

Loss of GC-G leads to renal ischemia in mice (Lin et al., 2008). Both GC-D and GC-G have accumulated multiple mutations which introduce premature stop codons and truncations (Manning et al., 2002). The allosteric regulation mediated by the KHD of these receptors is yet to be understood.

2.5. Unusual guanylyl cyclases associated with a kinase domain

Many receptor-like kinases in plants contain a guanylyl cyclase catalytic center embedded within the C-terminal region of a kinase domain (Freihat, Muleya, Manallack, Wheeler, & Irving, 2014). Interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinase 3 (IRAK3) also contains a "guanylyl cyclase centre" and cGMP production appears to mediate downstream signaling of IRAK3 (Freihat et al., 2019). However, a very recent structure of the IRAK3 pseudokinase domain showed that the ~14 residues comprising the guanylyl cyclase core formed a part of the C-terminal lobe of the pseudokinase domain (Lange, Nelen, Cohen, & Kulathu, 2021). Therefore, this unusual report of cGMP production by this protein could result purely from interactions with soluble guanylyl cyclases in the cell, and not be a direct consequence of the guanylyl cyclase "core" present within the pseudokinase domain.

2.6. Equipment

The following laboratory equipment are needed to perform the experimental procedures described.

Table-top centrifuge for 1.5 and 2mL microcentrifuge tubes (Centrifuge 5415 D, Eppendorf)

Cooling table-top centrifuge for 1.5 and 2mL microcentrifuge tubes set to 4°C (MicroCL 17R, Thermo Scientific)

Centrifuge capable of reaching 3200 × g and reducing temperature to 4°C for centrifuging RIA vials and 50mL conical tubes (Eppendorf centrifuge 5810R, rotor A-4-62)

Centrifuge capable of reaching 100,000 × g and reducing temperature to 4°C (L8-60M Ultracentrifuge, Beckman-Coulter)

Sonicator (IKA T 10 basic ULTRA-TURRAX with S 10 N–5 G dispersing tool, Branson Digital Sonifier 450 with a 1/8″ tapered microtip)

Dounce homogenizer

Spectrophotometer (Tecan)

MonoQ anion exchanger column (GE Healthcare Systems)

Akta FPLC system (GE Healthcare Systems)

Superdex 200 10/30 column (GE Healthcare Systems)

Dry bath (Benchmark)

Water bath (Julabo)

Thermomixer (Eppendorf)

End over rocker (Bionova)

Horizontal rocker (Neolab)

Chemiluminescence imaging system (Biorad Chemidoc XRS+)

Magnetic stirrer (SpinIt)

Dialysis bag (Merck)

10K MWCO spin filter (Pall Corporation)

Mini-Protean tetra vertical electrophoresis cell (Biorad)

Mini-Trans blot electrophoretic transfer cell (Biorad)

Mini-Protean short plates and 1mm spacer plates (Biorad)

Hemocytometer

21-gauge needle

Light microscope

Humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2

Shaker incubator capable of attaining 37°C and 200rpm

Conical flask

15 and 50mL conical tubes

1.5mL microcentrifuge tubes

Flasks and dishes treated for tissue culture

Sterile pipettes for tissue culture

BSL2 laminar air flow hood for tissue culture and radioactive experiments

Glass chamber for thin layer chromatography

Table-top vortex

Plastic vials for radioimmunoassay

Gamma counter (Perkin Elmer)

2.7. Reagents

HEPES buffer (pH7.5)

MOPS buffer (pH7.1)

Tris-Cl buffer (pH7.5)

Sodium phosphate buffer (pH8.0)

Potassium phosphate buffer (pH6.8)

Sodium acetate buffer (pH4.75)

Phosphate buffer saline (pH7.5)

Sodium chloride (Merck)

Magnesium chloride (Merck)

Manganese chloride (Merck)

Calcium chloride (Merck)

Potassium chloride (Merck)

Imidazole (Merck)

Dipyridamole (Merck, cat. no.: D9766)

Glycerol (Merck)

Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Merck)

Ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) (Merck)

Dithiothreitol (Merck)

2-mercaptoethanol (MP Biomedicals)

Soyabean trypsin inhibitor (Merck)

Leupeptin (Merck)

Aprotinin (Merck)

Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Merck)

Pepstatin A (Merck)

Microcystin (Merck, cat. no.: M2912)

Creatine phosphate (Merck, cat. no.: CRPHO-RO)

Creatine phosphokinase (Merck, cat. no.: C3755)

Adenosine 5′ triphosphate (ATP) (Merck, cat. no.: A2383)

Guanosine 5′ triphosphate (GTP) (Merck, cat. no.: G8877)

AMP-PNP (Merck, cat. no.:10102547001)

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) (Merck, cat. no.: A1663, N8768)

Stable toxin peptide (Bachem, cat. no.: YMC31034–163-2 CB915)

Sodium orthovanadate (Merck)

Sodium pyrophosphate (Merck)

Sodium fluoride (Merck)

Acrylamide and bisacrylamide (Merck)

Pre-stained protein ladder (Biorad, cat. no.: 161-0374)

Immun-Blot PVDF membrane (Biorad, cat. no.: 1620177)

Whatman no. 1 and no. 3 filter paper (GE Healthcare Systems)

Substrate solution for horse radish peroxidase during western blot (Immobilon, Millipore)

Isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX) (Merck, cat. no.: I5879)

DNaseI (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

RNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

NP-40 (Merck)

Triton X-100 (Merck)

Lubrol-PX (Merck)

1-propanol (Merck)

Myristic acid (Merck, cat. no.: M3128)

Butanol (Merck)

Glacial acetic acid (Merck)

Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (G Biosciences)

Bovine serum albumin (Merck)

Bradford reagent [prepare 5 × stock solution by dissolving 100mg of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G (Merck) in 50mL of 95% ethanol followed by addition of 100mL concentrated orthophosphoric acid (Merck). Make up volume till 200ml with distilled water and filter through Whatman no. 1 filter paper (GE Healthcare Systems)].

Ni-NTA beads (GE Healthcare Systems, Cat. No.: 17-5628-01)

ATP-agarose beads (Innova Biosciences 502-0002; Merck A2767)

Luria Bertani broth bacteriological grade (Pronadisa)

Agar powder bacteriological grade (Applied Life Sciences)

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Merck) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for culturing HEK293 cells

TC-100 medium (Merck) with 10% FBS for culturing Sf21 insect cells

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Merck)

E. coli DH10Bac cells for propagation of bacmid DNA (Invitrogen). Use either chemically competent or electrocompetent cells for transformation

Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen)

E. coli BL21 DE3 pLysS for protein expression

Monosuccinyl cGMP tyrosine methyl ester (Sc-cGMP-TME) (Biolog, cat. no.: M 023-01s)

Na125I (half-life: 60days) (ARC, USA, cat. no.: ARI 102)

Chloramine T (Merck, cat. no.: 402869)

Sodium metabisulfite (Merck, cat. no.: S1516)

Activated charcoal (Merck)

3. Protocol

3.1. Preparation of membranes for studying GC-A, GC-B, and GC-C activity (Edmund et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2021)

Isolate required cells from the target tissue following standard protocols. The yield of receptor available for analysis will depend on the tissue and the cell type. For adherent cells in culture (e.g., HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids harboring cDNAs encoding the receptor of interest and cultured on DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum), wash the adherent monolayer of cells in a confluent 10cm tissue culture dish with ice-cold PBS (10mL) to remove serum and media components. For suspended cells (i.e., Sf21 cells grown in glass bottles or Erlenmeyer flasks), resuspend the cells (~107) by pipetting in the culture medium, centrifuge the cells at 300 × g at 4°C in a 15mL plastic conical tube. Carefully remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in chilled PBS (10mL), and centrifuge again at 300 × g. Remove the supernatant and keep the pellet.

Resuspend ~107 cells in the pellet in 1mL homogenization buffer containing 50mM HEPES pH7.5, 100mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1mM dithiothreitol, 5μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), 5μg/mL leupeptin, 5μg/mL aprotinin, 2mM PMSF, 10mM sodium orthovanadate, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20mM sodium fluoride, and 500μM isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX).

Lyse cells by sonication (IKA T 10 basic ULTRA-TURRAX with S 10 N–5 G dispersing tool) at 60cycles, 60% amplitude for 10 pulses (each pulse 5s).

Centrifuge the suspension at 12,000 × g, 4°C for 60min. Aspirate the supernatant and retain for samples that contain intracellular domains of rGCs (i.e., the KHD-linker of the entire intracellular domain). Resuspend the pellet containing the membrane fraction in a phosphatase inhibitor buffer with 50mM HEPES pH7.5, 20% glycerol, 5μg/mL SBTI, 5μg/mL leupeptin, 5μg/mL aprotinin, 2mM PMSF, 10mM sodium orthovanadate, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate and 20mM sodium fluoride.

Estimate protein concentration in the crude membrane fraction using the Bradford reagent (see Section 3.2) and use for ATP binding assay or in vitro guanylyl cyclase assay. Advantages of estimating protein by this method are rapidity, reproducibility, minimal interferences, and high stability of protein-dye complex.

3.2. Preparation of membrane fractions from rod and cone outer segments for studying GC-E and GC-F activity (Yamazaki et al., 2003)

Isolate outer segment from 25 bovine retinas in dim to red light (to avoid photobleaching of rhodopsin) and resuspend them in 5ml of Buffer A (5mM HEPES pH7.5, 1mM DTT, 5mM MgCl2, 100μM CaCl2, 0.1mM PMSF, 5μM leupeptin, and 5μM pepstatin A).

Homogenize the suspension at 4°C by passing it through a needle with a 21-gauge diameter. Repeat 7 times.

Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 15min at 4°C to separate the membrane fraction.

Wash the pellet containing the membrane fraction in 5mL of buffer B (5mM HEPES pH7.5, 1mM DTT, 5mM MgCl2, 2mM EGTA, 0.1mM PMSF, 5μM leupeptin, and 5μM pepstatin A). Repeat 7 times.

Resuspend the membrane fraction in buffer C (10mM HEPES pH7.5, 1mM DTT, 2mM MgCl2, 0.1mM PMSF, 5μM leupeptin, and 5μM pepstatin A) at a concentration of 5mg/mL.

Estimate the concentration of rhodopsin in the membrane fraction (see Section 3.6.3) and use for ATP binding assay or in vitro guanylyl cyclase assay.

3.3. Preparation of membrane fractions from mammalian cells for studying GC-E and GC-F activity (Dizhoor et al., 1994)

Wash monolayer of adherent cells expressing GC-E or GC-F with ice-cold PBS.

Scrape the cells into ice cold 10mM MOPS pH7.1 containing 1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.5μg/mL leupeptin, 0.5μg/mL pepstatin and homogenize with 12 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer.

Remove debris by centrifugation at 200 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

Separate the membrane fraction by centrifuging at 100,000×g for 30min at 4°C.

Resuspend the pellet in 10mM MOPS pH7.1 and 1mM DTT.

Estimate protein concentration by the Bradford assay and use for ATP binding assay or in vitro guanylyl cyclase assay.

3.4. Purification of proteins

3.4.1. Purification of the intracellular domain of GC-A with KHD (GC-AID) or without KHD (GC-ACC+GC) (Pattanaik, Fromondi, Ng, He, & van den Akker, 2009)

Recombinant Bacmid DNA using DH10Bac cells and the Bac-to-Bac Expression system from Invitrogen was used to allow expression of a protein comprising amino acids 465 to 1029 of the entire intracellular domain of GC-A with an N-terminal a 6 × His-tag. High-Five cells were used for protein expression and harvested 72h following infection with recombinant baculovirus (5–10 multiplicity of infection; cell density ~106 cells/mL). An additional construct that did not contain the KHD but only the coiled-coil domain and the guanylyl cyclase domain, from residues 776–1029, was cloned and expressed in insect cells in a similar manner.

Lyse cells by sonicating in 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 8.0 containing 40mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 5μg/mL DNAseI, 10μg/mL RNAse, and protease inhibitor cocktail.

Add NP-40 to a final concentration of 1%.

Incubate the lysates at 4°C for 1h in a conical tube placed on a rocking platform.

Remove cell debris by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30min at 4°C.

Add washed Ni-NTA beads (1mL per 10mL of packed cells) to the supernatant and incubate for 2h at 4°C with rocking.

Centrifuge at 200g at 4°C to pellet the beads and pack them into a 5mL column.

Pass lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40 (3 × bed volume) through the column.

Wash the beads 15 times with the lysis buffer without NP-40 (10 × bed volume).

Elute the protein in 3 × bed volume of buffer containing 50mM sodium phosphate pH8.0, 250mM imidazole, 300mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 10% glycerol and the protease inhibitor cocktail.

Immediately after elution, add EDTA (pH7.0) to a final concentration of 10mM.

Exchange the buffer by dialysis against 10 volumes of buffer containing 20mM Tris-Cl pH8.0, 1mM DTT, and 10% glycerol, with 3 changes of buffer.

The sample is then applied to a MonoQ anion exchanger column (GE Healthcare Systems) and sample eluted with a 1-1M NaCl gradient with a flow rate of 1mL/per minute on an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare Systems).

Fractions containing the protein were then subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/30 column (GE Healthcare Systems) in a buffer containing 20mM Tris-Cl, pH8.0, 1mM DTT, 150mM NaCl and 10% glycerol with a flow rate of 0.2mL/min. Estimate protein using the Bradford method with BSA as a standard and use for ATP binding assay or in vitro guanylyl cyclase assay.

3.4.2. Purification of the entire intracellular domain of GC-C (GC-CID) or KHD-linker region of GC-C (GC-CKHD+CC) (Jaleel et al., 2006)

The entire intracellular domain of GC-C (residues 455–1073) and the KHD and coiled-coil region (residues 455–810) were cloned and expressed in Sf21 insect cells using the Bac-to-Bac expression system from Invitrogen (see Section 3.4.1).

For expression, cells are grown in 100mL of TC-100 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, with a starting cell density of 5 × 105/mL. Cells are grown with gentle shaking in a 500mL conical flask at 100rpm for 72h at 25°C.

The cell suspension is centrifuged at 1000 × g and the pellet resuspended in lysis buffer (3mL) containing 50mM HEPES pH7.5, 100mM NaCl, 5mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5μg/mL aprotinin, 5μg/mL leupeptin, 2mM PMSF, 10% glycerol.

Lyse cells by sonication at 4°C (Branson Digital Sonifier 450 with a 1/8″ tapered microtip) at 50% power till the cells lyse (usually 5min).

Centrifuge at 12,000×g for 60min at 4°C and harvest the supernatant which contains the soluble target protein (GC-CID or GC-CKHD+CC). Estimate total cytosolic protein using Bradford reagent with BSA as a standard and use for ATP binding assay or in vitro guanylyl cyclase assay.

3.4.3. Purification of guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 (GCAP-1) (Krylov, Niemi, Dizhoor, & Hurley, 1999)

Transform pET expression plasmid encoding GCAP-1 into E. coli BL21 DE3pLysE harboring pBB131 encoding yeast N-myristoyl transferase (NMT) and kanamycin resistance (Krylov et al., 1999). For transformation, mix 1 μg plasmid DNA with 50μL of E. coli BL21 DE3pLysE cells made chemically competent by calcium chloride, incubate on ice for 30min and give a heat shock for 2min at 37°C followed by immediate incubation on ice for 5min. Add 1mL of Luria broth without antibiotics and allow recovery for 1h at 37°C. Plate the cells on LB agar plate containing kanamycin (50μg/mL) and incubate at 37°C for 12–16 h.

Use a single colony to grow a culture (500mL) in Luria Broth with shaking in a 2L conical flask at 37°C and 200rpm. Grow to an OD600 of 1.

Supplement bacterial media with free myristic acid (50μg/mL) 30min before induction of expression with 1mM IPTG.

After expression for 2–5h at 37°C and 200rpm, lyse cells by sonication (Branson Digital Sonifier 450 with a 1/8″ tapered microtip) on ice in 5mL lysis buffer containing 40mM Tris-Cl pH7.5, 0.5mM EDTA, 1mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20μg/mL leupeptin, 100μM PMSF.

Centrifuge the lysate at 30,000×g for 30min at 4°C.

Wash the pellet twice with 10mL lysis buffer by resuspension and centrifugation at 30,000×g for 30min at 4°C.

Dissolve the pellet in 5mL of 6M urea and dialyze 3 times against 1000 volumes of lysis buffer without protease inhibitors.

Estimate protein concentration by the Bradford assay and use for guanylyl cyclase assays of GC-E and GC-F.

3.4.4. Purification of guanylyl cyclase activating protein 2 (GCAP-2) (Olshevskaya, Hughes, Hurley, & Dizhoor, 1997)

Transform pET expression plasmid into E. coli BL21 DE3pLysS harboring pBB131 encoding yeast N-myristoyl transferase (NMT) and kanamycin resistance as described above.

Use a single colony to grow a culture (500mL) in Luria Broth with shaking in a 2L conical flask at 200rpm. Grow to an OD600 of 1.

Supplement bacterial media with free myristic acid (50μg/mL) 30 min before induction of expression with 1mM IPTG.

After expression for 3.5h at 200rpm and 37°C, harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation at 8000×g for 20 min at 4°C.

Lyse the cells by sonication (Branson Digital Sonifier 450 with a 1/8″ tapered microtip) in 3mL lysis buffer containing 40mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.5mM EDTA, 1mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20μg/mL leupeptin, 100μM PMSF.

Centrifuge the suspension at 20,000 × g for 10min and wash the pellet thrice with 10mL of buffer A containing 20mM Tris-Cl pH7.5, 1mM EDTA, 7mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100μM PMSF, 20μg/mL leupeptin.

Extract GCAP-2 from the pellet by homogenization in buffer A supplemented with 100mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1mM EDTA, 6M urea for 30min at 4°C (5mL).

Dialyze twice against 300–1000 volumes of buffer A overnight at 4°C.

Remove precipitate by centrifugation at 30,000×g for 10 min.

Purify GCAP-2 by gel filtration on a Superdex 200 10/30 on an Akta FPLC system equilibrated with 10mM Tris-Cl pH7.5 and 10mM 2-mercaptoethanol, flow rate 0.2ml/min.

Estimate protein concentration by the Bradford method and use for guanylyl cyclase assays of GC-E and GC-F.

3.5. ATP-agarose binding assay (Edmund et al., 2019; Jaleel et al., 2006)

Crude whole cell lysates, membrane fractions containing full-length rGCs or cytosolic fractions containing the soluble intracellular domains of rGCs are prepared from mammalian or insect cells expressing the desired protein as described above. The amount of material taken would depend on the expression levels of the protein of interest in particular cell lines or extracts. This would have to be empirically determined for each receptor, based on the method of detection used to monitor presence of the protein. If western blot is used, that would depend on the affinity of the antibody used for blotting and would vary for each protein.

For membrane bound receptors, the membrane would first need to be suspended in 50mM HEPES pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, 10μg/mL leupeptin, 10μg/mL aprotinin, containing 1% Triton X-100 at a concentration of 5mg protein/mL. The suspension is then placed in a 15mL conical tube and placed on a rocker for 1h at 4°C and gently mixed. This would solubilize membrane-bound proteins. Centrifuge the sample at 16,000 × g at 4°C and retain the supernatant.

Dilute the supernatant or cytosolic fraction (1:10, v/v) in ATP-agarose interaction buffer. For GC-A, the buffer used is 50mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2. For GC-C, buffer used is 50mM HEPES pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, 10μg/mL leupeptin, 10μg/mL aprotinin, 0.1% Triton X-100.

Remove endogenous ATP by passing the protein mix from step 2 or 3 through a 10K MWCO spin filter. The protein of interest will be retained, and ATP will be removed in the flow-through. Bring down the volume by 90% and repeat this step twice in ATP-agarose interaction buffer.

Wash the agarose beads conjugated to ATP in the ATP-agarose interaction buffer thrice. Beads are available with a number of suppliers (e.g., Innova Biosciences 502-0002; Merck A2767) but ensure that the conjugation is through the γ-phosphate.

Add the required volume of washed ATP-agarose beads to 500μL of the protein mix from step 3 such that the final concentration ofATP on the beads is 250μM (for GC-A) or 200μM (for GC-C). The conjugation of ATP to agarose beads is usually at 1–5μMoles/mL, so for 500μL of sample volume, 100–125μL beads would be sufficient.

Incubate the reaction mixture in a 1.5mL tube for 1 h at 4°C with gentle mixing in an Eppendorf Thermomixer.

Wash the ATP-agarose beads thrice with chilled ATP-agarose interaction buffer (1mL each wash for GC-A) or twice with ATP-agarose interaction buffer with Triton X-100 and once without Triton X-100 (1mL each wash for GC-C).

Boil the beads in 200μL of reducing Laemmli buffer for 5 min prior to loading on the gel. SDS-PAGE is carried out in a 10% gel with 0.7–1.2% crosslinker, depending on the size of the protein of interest and the separation required. Gels are run at 200 V till the dye reaches the end of the gel. Markers used are from Biorad.

Transfer proteins to a PVDF membrane (Biorad, cat. no.: 1620177) in buffer containing 25mM Tris base, 192mM glycine, 20% methanol, pH8.3 at 200 V and 160mA for 120min using Mini-Trans blot electrophoretic transfer cell (Biorad).

Rinse the PVDF membrane in 10mM Tris-ClpH7.2, 100mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and block for 1 h at room temperature in 5% blocking solution (GE Healthcare systems) on a gentle rocking platform.

Incubate the membrane with respective primary antibodies for 12–14 h at 4°C on a gentle rocking platform. Dilute the primary antibody in TBST containing 5% BSA at the necessary dilution recommended by the manufacturer or standardized upon trial.

Wash the membrane thrice with TBST by incubating for 10 min each on a fast-rocking platform at room temperature.

Incubate membrane with secondary antibody diluted (at a concentration recommended by manufacturer or standardized upon trial) in TBST containing 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature on a gentle rocking platform. The type of secondary antibody will depend on the host species in which the primary antibody was raised.

Wash the membrane thrice with TBST by incubating for 10 min each on a fast-rocking platform at room temperature.

Visualize immunoreactive bands by chemiluminescence using Immobilon reagent (Millipore) on a Chemidoc XRS + system (Biorad).

3.6. Guanylyl cyclase assay

The catalytic guanylyl cyclase domain of rGCs belongs to the family of class III nucleotide cyclases (Biswas et al., 2009; Dove, 2017). Class III nucleotide cyclases undergo a head-to-tail dimerization to attain catalytic activity (Shenoy & Visweswariah, 2004; Zhang, Liu, Ruoho, & Hurley, 1997), with the active site formed by the two subunits at the dimer interface. Class III nucleotide cyclases convert ATP or GTP to their equivalent 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide following a two-metal supported mechanism (Liu et al., 1997). Receptor guanylyl cyclases homodimerize to form two active sites and bind two substrate molecules per dimer (Dove, 2017). Three residues form the functional catalytic center. An Asp residue from one protomer assists in proton abstraction and an Asn/Arg pair from another protomer stabilizes the transition state. One metal ion (B) stays bound to the β and γ-phosphates of ATP, while the other free metal ion (A) is called the catalytic ion. Ion A binds to the 30-OH of ribose of GTP and reduces its pKa, thus generating a nucleophile that attacks the α-phosphoanhydride bond in GTP and cleaves it through a direct displacement reaction. The transition state stabilizing Asn stabilizes the 3′ oxyanion generated by proton removal, while the Arg stabilizes a pentavalent transition state of the α-phosphate while it is subject to a nucleophilic attack by the 3α oxyanion leading to the formation of cGMP (Shenoy & Visweswariah, 2004; Zhang et al., 1997).

Guanylyl cyclase activity is assayed by measuring the amount of cGMP derived from GTP in the presence of MgCl2 or MnCl2, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor (isobutyl methyl xanthine; IBMX), and a GTP regenerating system. Free metal ions or allosteric regulators are added to the reaction mix as per requirement.

3.6.1. GC-A and GC-B (Edmund et al., 2019)

Dilute the protein (usually 10–50 μg total protein) in 20μL of phosphatase inhibitor buffer (50mM HEPES pH7.5, 20% glycerol, 5μg/mL soyabean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), 5μg/mL leupeptin, 5μg/mL aprotinin, 2mM PMSF, 10mM sodium orthovanadate, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20mM sodium fluoride).

Add 60μL of reaction cocktail prewarmed in a water bath to 25°C to obtain final reaction conditions of 25mM HEPES pH7.5, 50mM NaCl, 500μM IBMX, 0.5μM microcystin, 1mM EDTA, 0.1% BSA, 0.1mM GTP and a nucleotide triphosphate regeneration system containing 5mM creatine phosphate and 0.1μg/mL creatine phosphokinase.

To study effect of activators, add 20μL of a 5 × activation mix to obtain 5mM MgCl2 or MnCl2, 1mM ATP, 1μM ANP or CNP, 1% v/v Triton X-100 in the final reaction mix as required.

Incubate the reaction mix at 37°C for 10min in a water bath.

Stop the reaction with 400μL of ice-cold 50mM sodium acetate buffer (pH4.75) containing 5mM EDTA. Heat samples for 5 min in a boiling hot water bath in tightly capped Eppendorf tubes followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Collect the supernatant.

Estimate cGMP levels by radioimmunoassay (see Section 3.7) in the supernatant fractions.

3.6.2. GC-C (Saha, Biswas, Kondapalli, Isloor, & Visweswariah, 2009)

Dilute membrane or cytosolic protein with buffer (50mM HEPES pH7.5, 20% glycerol, 5μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), 5μg/mL leupeptin, 5μg/mL aprotinin, 2mM PMSF, 10mM sodium orthovanadate, 1mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20mM sodium fluoride) containing MgCl2 or MnCl2 (final concentration 10mM) in a total volume of 20μL. Usually, 10–50 μg of protein is sufficient for the assay.

To this add 20μL of reaction cocktail prewarmed in a water bath to 25°C, to final reaction conditions of 60mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 500μM IBMX, and a nucleotide triphosphate regeneration system containing 7.5mM creatine phosphate and 10 μg of creatine phosphokinase.

Add GTP, MgCl2 or MnCl2 stock solutions in a final volume of 10μL to achieve a final concentration of 1mM of each reactant.

To study the effect of activators, add 1mM Mg-ATP, 10−7M or 10−6M STa (for human and mouse respectively), or 0.1% Lubrol-PX to the protein mix (step 1).

Incubate the reaction mix at 37°C for 10min.

Stop the reaction by adding 400μL of ice-cold 50mM sodium acetate buffer (pH4.75). Heat samples for 5 min in a heating block set to 95°C in tightly capped Eppendorf tubes and centrifuge at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Collect the supernatant for measurement of cGMP by radioimmunoassay (see Section 3.7).

3.6.3. GC-E and GC-F (Tucker et al., 1997)

Dilute the membrane fraction to a rhodopsin concentration of 0.48 μg/μL (estimate total protein; 80% of total protein in washed retinal outer segments is rhodopsin (Papermaster & Dreyer, 1974)) in 2 × GC buffer (200mM KCl, 100mM MOPS, 14mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20mM MgCl2 or MnCl2, 16mM NaCl, 2mM EGTA). For kinetic analysis at least 10 concentrations of substrate (GTP) would be required. Therefore, ~150μL total volume would be needed.

Combine 12.5μL of the diluted mix from the previous step (6 μg rhodopsin) with 10μM dipyridamole and additional factors (detailed in step 3) to a total volume of 20μL.

Measure basal activity in the presence of 0.9mM CaCl2. For stimulated activity, preincubate membrane fractions in 2 × GC buffer in 30°C in the presence of 0.5mM CaCl2 coupled with 0.5mM ATP, 0.75mM AMP-PNP, 5.1μM (0.12mg/mL) GCAP-1 or 0.84μM (0.02mg/mL) GCAP-2 (purified as described in Sections 3.4.3 and 3.4.4) or 1% Triton X-100 for the required time durations in a total volume of 45μL.

Initiate the reaction by adding 5μL of 5mM GTP to attain a final concentration of 1mM GTP in the reaction.

Incubate the reaction mix for 10min at 30°C.

Stop the reaction by adding 450μL of ice-cold 50mM sodium acetate buffer (pH4.75).

Estimate cGMP concentration by radioimmunoassay as described below.

3.7. Radio-iodination of cGMP and radioimmunoassay (RIA)

All precautions required for use of radioactivity must be followed. Refer to Fig. 4 for schematic illustration.

Fig. 4. Schematic representation of radioiodination of cGMP and radioimmunoassay.

(A–D) Workflow for radioiodination of cGMP with I125. (E) A typical chromatogram post cGMP radioiodination depicting free iodine, mono and di iodinated Sc-cGMP-TME distributed across the fractions. (F) Curve depicting the determination of the dilution of cGMP antisera to be used in radioimmunoassay. Red arrowhead indicates antisera dilution corresponding to 50% specific binding. This dilution of antisera is to be used for 25,000 CPM of I125 Sc-cGMP-TME. (G) A typical standard curve of radioimmunoassay with cGMP concentration ranging from 5fmol to 10pmol. Concentration of cGMP in samples can be determined by interpolating against the standard curve.

For radio-iodination, mix 400 ng of monosuccinyl cGMP tyrosine methyl ester (Sc-cGMP-TME) with 600 μCi of NaI125 0.5 M potassium phosphate buffer pH6.8.

Initiate the reaction by adding 5μL of oxidizing agent chloramine T (1 mg/mL in potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.8) to a final reaction volume of 50μL.

Incubate the reaction mix on ice for 60s and stop it by adding 50μL of sodium metabisulfite (5 mg/mL) in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

Subject the reaction mixture to descending chromatography in a solvent system comprising 1-butanol: glacial acetic acid: water (12:3:5) for 7 h in an overnight saturated glass chamber using a Whatman 3 filter paper (~2*30cm) as the solid phase.

Dry the chromatogram and cut it horizontally into thin strips of 1 cm width to obtain individual fractions post chromatographic separation. Unlabeled, mono-iodinated and di-iodinated cGMP-TME migrate to different extents on the paper chromatogram and will therefore be present in separate fractions.

Incubate the strips in 1mL of 50mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.75 for 1 h at 4°C followed by vortexing at maximum speed at room temperature for 30 s for mechanical elution.

After allowing the paper strip to settle, estimate the radioactivity in each fraction by aliquoting 10μL of each fraction in an RIA vial (see Section 3.2) which is placed in a γ-counter. Tubes are counted for 30s.

A typical chromatogram (Fig. 4) will result in 3 peaks: di-iodinated cGMP migrating the furthest distance followed by mono-iodinated cGMP and free I125.

Use the fraction containing mono-iodinated Sc-cGMP-TME for radioimmunoassay after adding an equal volume of 1-propanol to fractions containing the labeled cGMP. Store at –20° C.

Set up the radioimmunoassay in a total volume of 300μL of 50mM sodium acetate buffer pH4.75 containing 5mg/mL BSA in RIA vials (see Section 3.2).

Provide a total input of ~25,000 CPM of 125I-cGMP-TME in each tube. Prepare dilutions of the available antiserum and add to the radiolabeled cGMP. Incubate the tubes at 4°C for 16 h. Add 1ml of ice-cold activated charcoal suspension (2 mg/L) in 50mM potassium phosphate buffer pH6.3 containing 1 mg/mL BSA. Free radiolabeled cGMP will bind to the charcoal.

Stand the tubes for 2min and centrifuge at 3000 × g for 20min at 4°C. Decant off the supernatant and place the tubes containing the charcoal pellet in the γ-counter. Count for 15 s. Determine the dilution of antibody required to achieve ~50% binding of the input radioactivity. This dilution will be used for the radioimmunoassay to estimate cGMP in samples.

For the assay to estimate cGMP in samples, assay volumes are 300μL and the amount of antiserum is that required for ~50% binding if ~25,000 CPM is added.

Prepare a set of 12 tubes for a standard curve having a range of 5 fmol to 10pmol unlabeled cGMP per tube. To make the standards, dilute the cGMP in 100μL of 50mM sodium acetate (pH4.75). Add 10–100μL of samples to be tested to a separate set of tubes and make up volume till 100μL with 50mM sodium acetate (pH4.75). Prepare 125I-cGMP-TME solution in 50mM sodium acetate (pH4.75) containing 5mg/mL BSA such that there is ~25,000CPM/100μL and add 100μL per tube. Dilute antiserum to the required amount (determined in step 13) in 50mM sodium acetate (pH4.75) containing 5mg/mL BSA and add 100μL of that to each tube. Set up two tubes which contain buffer but to which no antibody is added. These two tubes serve to estimate non-specific binding.

Incubate the reaction at 4°C for 12–16h.

Separate the free cGMP from cGMP bound to the antibody by adding 1mL of ice-cold activated charcoal suspension (2mg/L) in 50mM potassium phosphate buffer pH6.3 containing 1 mg/ml BSA.

Centrifuge the RIA vials containing the reaction mix at 3200 × g for 20min at 4°C.

Decant the supernatant and estimate the radioactivity of the free I125-cGMP-TME adsorbed on the charcoal using a gamma counter.

Set up a standard curve after subtracting non-specific binding from total counts bound (counts bound = input radioactivity – counts bound to charcoal).

Estimate the concentration of cGMP in samples from the standard curve

4. Summary

We present methods to monitor the allosteric regulation of rGCs by the pseudokinase domain. There is no structural information to date on the intracellular domain of this class of receptors. In its absence, one can speculate on interdomain interactions and regions critical for signal transmission using mutagenesis (Saha et al., 2009). Specific amino acids critical for the relay of information following ligand binding are identifiable, based on mutations in these residues and association with human disorders (Table 1). It is anticipated that the pseudokinase domain in these receptors could be targeted by small-molecule activators or inhibitors to regulate receptor activity. Several inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinases in therapeutic use indicate that the kinase domain is amenable to specific targeting (Wu, Nielsen, & Clausen, 2016). High-throughput screening approaches, perhaps using drugs already in use, using sensors to monitor cGMP production could be utilized for such studies in the future, but this would necessitate distinguishing molecules that interact with the guanylyl cyclase domain from those that bind solely to the pseudokinase domain. Alternatively, engineered constructs harboring the pseudokinase domain coupled to fluorescence sensors will allow direct monitoring of conformational changes that occur on binding of either ATP or small molecules.

Acknowledgments

A.B. acknowledges support from the Indian Institute of Science and the Commonwealth Scholarship Foundation, UK, with award number INCN-2020-140. S.S.V. is a JC Bose National Fellow (SB/S2/JCB-18/2013) and a Margdarshi Fellow supported by the Wellcome Trust DBT India Alliance (IA/M/16/502606).

References

- Aparicio JG, Applebury ML. The photoreceptor guanylate cyclase is an autophosphorylating protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(43):27083–27089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H, Kelliher KR, Zufall F, Munger SD. The receptor guanylyl cyclase type D (GC-D) ligand uroguanylin promotes the acquisition of food preferences in mice. Chemical Senses. 2013;38(5):391–397. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad N, Visweswariah SS. The multiple and enigmatic roles of guanylyl cyclase C in intestinal homeostasis. FEBS Letters. 2012;586(18):2835–2840. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman DF, Lipton R, Melicow MM, Price TD. Isolation of adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate and guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate from rat urine. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1963;11:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu N, Arshad N, Visweswariah SS. Receptor guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C): Regulation and signal transduction. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2010;334(1-2):67–80. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu N, Bhandari R, Natarajan VT, Visweswariah SS. Cross talk between receptor guanylyl cyclase C and c-src tyrosine kinase regulates colon cancer cell cytostasis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(19):5277–5289. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00001-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereta G, Wang B, Kiser PD, Baehr W, Jang GF, Palczewski K. A functional kinase homology domain is essential for the activity of photoreceptor guanylate cyclase 1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(3):1899–1908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuve A. Conversion of a guanylyl cyclase to an adenylyl cyclase. Methods. 1999;19(4):545–550. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari R, Srinivasan N, Mahaboobi M, Ghanekar Y, Suguna K, Visweswariah SS. Functional inactivation of the human guanylyl cyclase C receptor: Modeling and mutation of the protein kinase-like domain. Biochemistry. 2001;40(31):9196–9206. doi: 10.1021/bi002595g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari R, Suguna K, Visweswariah SS. Guanylyl cyclase C receptor: Regulation of catalytic activity by ATP. Bioscience Reports. 1999;19(3):179–188. doi: 10.1023/a:1020273619211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas KH, Shenoy AR, Dutta A, Visweswariah SS. The evolution of guanylyl cyclases as multidomain proteins: Conserved features of kinase-cyclase domain fusions. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2009;68(6):587–602. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A, Banerjee S, Visweswariah SS. Mutational landscape of receptor guanylyl cyclase C: Functional analysis and disease-related mutations. IUBMB Life. 2020;72(6):1145–1159. doi: 10.1002/iub.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan PM, Smirnov D, Smolenski A, Feil S, Feil R, Hofmann F, et al. A sensitive method for determining the phosphorylation status of natriuretic peptide receptors: cGK-Ialpha does not regulate NPR-A. Biochemistry. 2006;45(4):1295–1303. doi: 10.1021/bi051253d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Kohse KP, Chang B, Hirata M, Jiang B, Douglas JE, et al. Characterization of ATP-stimulated guanylate cyclase activation in rat lung membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1990;1052(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90071-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao YC, Cheng CJ, Hsieh HT, Lin CC, Chen CC, Yang RB. Guanylate cyclase-G, expressed in the Grueneberg ganglion olfactory subsystem, is activated by bicarbonate. The Biochemical Journal. 2010;432(2):267–273. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M, Garbers DL. The protein kinase domain of the ANP receptor is required for signaling. Science. 1989;245(4924):1392–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.2571188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M, Wilson EM. Ligand-independent oligomerization of natriuretic peptide receptors. Identification of heteromeric receptors and a dominant negative mutant. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(26):18589–18597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman TD, Schulz S, Potter LR, Garbers DL. Seminal plasma factors that cause large elevations in cellular cyclic GMP are C-type natriuretic peptides. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(5):3698–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane JK, Shanks KL. Phosphorylation and activation of the intestinal guanylyl cyclase receptor for Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin by protein kinase C. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1996;165(2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00229472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge HR. The localization of guanylate cyclase in rat small intestinal epithelium. FEBS Letters. 1975a;53(2):237–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge HR. Properties of guanylate cyclase and levels of cyclic GMP in rat small intestinal villous and crypt cells. FEBS Letters. 1975b;55(1):143–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey DM, Flora DR, Bryan PM, Xu X, Chen Y, Potter LR. Differential regulation of membrane guanylyl cyclases in congestive heart failure: Natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR)-B, Not NPR-A, is the predominant natriuretic peptide receptor in the failing heart. Endocrinology. 2007;148(7):3518–3522. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Lowe DG, Olshevskaya EV, Laura RP, Hurley JB. The human photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclase, RetGC, is present in outer segments and is regulated by calcium and a soluble activator. Neuron. 1994;12(6):1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Olshevskaya EV, Henzel WJ, Wong SC, Stults JT, Ankoudinova I, et al. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a 24-kDa Ca(2+)-binding protein activating photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(42):25200–25206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove S. Mammalian nucleotidyl cyclases and their nucleotide binding sites. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2017;238:49–66. doi: 10.1007/164_2015_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmund AB, Walseth TF, Levinson NM, Potter LR. The pseudokinase domains of guanylyl cyclase-A and -B allosterically increase the affinity of their catalytic domains for substrate. Science Signaling. 2019;12(566) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau5378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte LR, Krause WJ, Freeman RH. Escherichia coli enterotoxin receptors: Localization in opossum kidney, intestine, and testis. The American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257(5 Pt 2):F874–F881. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.5.F874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freihat L, Muleya V, Manallack DT, Wheeler JI, Irving HR. Comparison of moonlighting guanylate cyclases: Roles in signal direction? Biochemical Society Transactions. 2014;42(6):1773–1779. doi: 10.1042/BST20140223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freihat LA, Wheeler JI, Wong A, Turek I, Manallack DT, Irving HR. IRAK3 modulates downstream innate immune signalling through its guanylate cyclase activity. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):15468. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulle HJ, Vassar R, Foster DC, Yang RB, Axel R, Garbers DL. A receptor guanylyl cyclase expressed specifically in olfactory sensory neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(8):3571–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzano H, Wu HI, Waldman SA. Adenine nucleotide regulation of particulate guanylate cyclase from rat lung. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1991;1077(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90531-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca WA, Gray-Keller MP, Detwiler PB, Palczewski K. Purification and physiological evaluation of a guanylate cyclase activating protein from retinal rods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(9):4014–4018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca WA, Van Hooser JP, Palczewski K. Nucleotide inhibitors and activators of retinal guanylyl cyclase. Biochemistry. 1994;33(11):3217–3222. doi: 10.1021/bi00177a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Zhang JJ, Huang XY. Stimulation of guanylyl cyclase-D by bicarbonate. Biochemistry. 2009;48(20):4417–4422. doi: 10.1021/bi900441v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel M, London RM, Eber SL, Forte LR, Visweswariah SS. Expression of the receptor guanylyl cyclase C and its ligands in reproductive tissues of the rat: A potential role for a novel signaling pathway in the epididymis. Biology of Reproduction. 2002;67(6):1975–1980. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.006445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel M, Saha S, Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. The kinase homology domain of receptor guanylyl cyclase C: ATP binding and identification of an adenine nucleotide sensitive site. Biochemistry. 2006;45(6):1888–1898. doi: 10.1021/bi052089x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel M, Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. Tyrphostins are inhibitors of guanylyl and adenylyl cyclases. Biochemistry. 2004;43(25):8247–8255. doi: 10.1021/bi036234n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert S, Labrecque J, De Lean A. Reduced activity of the NPR-A kinase triggers dephosphorylation and homologous desensitization of the receptor. Biochemistry. 2001;40(37):11096–11105. doi: 10.1021/bi010580s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juilfs DM, Fulle HJ, Zhao AZ, Houslay MD, Garbers DL, Beavo JA. A subset of olfactory neurons that selectively express cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterase (PDE2) and guanylyl cyclase-D define a unique olfactory signal transduction pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(7):3388–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knape MJ, Herberg FW. Metal coordination in kinases and pseudokinases. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2017;45(3):653–663. doi: 10.1042/BST20160327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, de Sauvage FJ, Lowe DG, Goeddel DV. Conservation of the kinase like regulatory domain is essential for activation of the natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclases. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1992;12(6):2581–2590. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2581-2590.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, Lowe DG, Bennett GL, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, et al. Selective activation of the B natriuretic peptide receptor by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) Science. 1991;252(5002):120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1672777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov DM, Niemi GA, Dizhoor AM, Hurley JB. Mapping sites in guanylyl cyclase activating protein-1 required for regulation of photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(16):10833–10839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, Ng CK, Su YH, Kilic A, Mitko D, Bien-Ly N, et al. Identification of an orphan guanylate cyclase receptor selectively expressed in mouse testis. The Biochemical Journal. 2004;379(Pt2):385–393. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurose H, Inagami T, Ui M. Participation of adenosine 5′-triphosphate in the activation of membrane-bound guanylate cyclase by the atrial natriuretic factor. FEBS Letters. 1987;219(2):375–379. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon A, Scott S, Taujale R, Yeung W, Kochut KJ, Eyers PA, et al. Tracing the origin and evolution of pseudokinases across the tree of life. Science Signaling. 2019;12(578) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aav3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SM, Nelen MI, Cohen P, Kulathu Y. Dimeric structure of the pseudokinase IRAK3 suggests an allosteric mechanism for negative regulation. Structure. 2021;29(3):238–251.:e234. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura RP, Hurley JB. The kinase homology domain of retinal guanylyl cyclases 1 and 2 specifies the affinity and cooperativity of interaction with guanylyl cyclase activating protein-2. Biochemistry. 1998;37(32):11264–11271. doi: 10.1021/bi9809674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T, Cockerham RE, Michalakis S, Biel M, Garbers DL, Reed RR, et al. Contribution of the receptor guanylyl cyclase GC-D to chemosensory function in the olfactory epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(36):14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2021;49(W1):W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Cheng CF, Hou HH, Lian WS, Chao YC, Ciou YY, et al. Disruption of guanylyl cyclase-G protects against acute renal injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(2):339–348. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ruoho AE, Rao VD, Hurley JH. Catalytic mechanism of the adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases: Modeling and mutational analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(25):13414–13419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DG, Dizhoor AM, Liu K, Gu Q, Spencer M, Laura R, et al. Cloning and expression of a second photoreceptor-specific membrane retina guanylyl cyclase (RetGC), RetGC-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(12):5535–5539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298(5600):1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MR, Angele A, Kremmer E, Kaupp UB, Muller F. A cGMP-signaling pathway in a subset of olfactory sensory neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(19):10595–10600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra V, Bose A, Kiran S, Banerjee S, Shah IA, Chaukimath P, et al. Gut-associated cGMP mediates colitis and dysbiosis in a mouse model of an activating mutation in GUCY2C. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2021;218(11) doi: 10.1084/jem.20210479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger SD, Leinders-Zufall T, McDougall LM, Cockerham RE, Schmid A, Wandernoth P, et al. An olfactory subsystem that detects carbon disulfide and mediates food-related social learning. Current Biology. 2010;20(16):1438–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase M, Katafuchi T, Hirose S, Fujita T. Tissue distribution and localization of natriuretic peptide receptor subtypes in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension. 1997;15(11):1235–1243. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Qiu Y, Ogata CM, Misono KS. Crystal structure of hormone-bound atrial natriuretic peptide receptor extracellular domain: Rotation mechanism for transmembrane signal transduction. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(27):28625–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]