Abstract

Background

We systematically identified effective and resource-efficient strategies for recruiting families into health promoting intervention research.

Methods

Four databases were searched for reviews. Interventions were extracted from included reviews. Additionally, a Delphi study was conducted with 35 experts in family-based research. We assessed extracted data from our review and Delphi participants’ opinions by collating responses into overarching themes based on recruitment setting then recruitment strategies to identify effective and resource-efficient strategies for recruiting families into intervention research.

Results

A total of 64 articles (n= 49 studies) were included. Data regarding recruitment duration (33%), target sample size (32%), reach (18%), expressions of interest (33%), and enrolment rate (22%) were scarcely reported. Recruitment settings (84%) and strategies (73%) used were available for most studies. However, the details were vague, particularly regarding who was responsible for recruitment or how recruitment strategies were implemented. The Delphi showed recruitment settings and strategies fell under 6 themes: school-based, print/electronic media, community settings-based, primary care-based, employer-based, and referral-based strategies.

Conclusions

Under-recruitment in family-based trials is a major issue. Reporting on recruitment can be improved by better adherence to existing guidelines. Our findings suggest a multifaceted recruitment approach targeting adults and children with multiple exposures to study information.

Keywords: Delphi, overweight, screen time, intervention research

Introduction

Childhood overweight and obesity remains to be an omnipresent global public health issue as the prevalence has risen steadily worldwide over the past few decades [1–3]. Contributing to the increasing waistlines of young people is the proliferation of poor lifestyle behaviours, with few children meeting physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and fruit and vegetable consumption recommendations internationally [4–7]. Parents can influence their children’s health behaviours through a variety of mechanisms, including their general parenting style, parenting practices (e.g., rule setting), and their control over the home environment [8, 9]. Therefore, health promotion interventions targeting families may therefore be a valuable way to improve lifestyle behaviours physical activity among children [10, 11]. A vital first step towards this goal is the development of strategies to overcome barriers to recruitment.

The recruitment of participants into intervention research has been notoriously difficult for research teams around the world [12, 13]. Two reviews of publicly funded trials in the UK (through the National Institute for Health Research) found that only about half of the included trials recruited 100% of their target sample size within their pre-agreed timescale [14, 15]. The overall start to recruitment was delayed in 41% of trials, early recruitment problems occurred in 63% of trials [15], and just over one-third received an extension of some kind [14, 15]. There is little evidence that recruitment into intervention research is improving over time [12, 15]. Recruitment of families to research projects is particularly challenging [9, 16–18]. Elsewhere, we have described specific recruitment challenges we have encountered in previous work [19–21], but there has not been a comprehensive assessment of how to recruit families to family-based health promotion research.

The aim of this study was, therefore, to systematically identify effective and resource-efficient strategies for recruiting families into intervention research aimed at improving physical activity or nutrition or reducing levels of sedentary behaviour (including screen time) and overweight/obesity. Our objectives were to: (1) describe procedures used and outcomes related to recruitment (e.g., recruitment duration, strategies used, recruitment settings, reach, expressions of interest, enrolment rates); (2) determine the most optimal family-based recruitment strategies.

Methods

This study included two phases: (1) a systematic review of family recruitment methods and (2) a Delphi consensus study. Both phases examined the recruitment strategies used by researchers conducting family-based intervention research with outcomes related to physical activity, sedentary behaviour (including screen time), nutrition, and obesity prevention. Details of the protocol for this study were registered on PROSPERO (ref: CRD42019140042) and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=140042.

Phase 1 – Systematic review

Search strategy overview

Reporting of the systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [22]. In short, we identified relevant intervention studies through a systematic search of published reviews on the relevant topic. Intervention studies were then extracted from those included reviews. Subsequently, a forward search of the included intervention studies identified more recently published studies not captured in the included reviews.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews

All types of reviews describing the results of family-based experimental studies with outcomes related to physical activity, sedentary behaviour, nutrition, or obesity prevention were eligible for inclusion.

Intervention studies

Intervention studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Participants. Generally healthy school aged children and youth and at least one adult primarily responsible for their care. Studies focussed on pre-school or post-secondary aged youth samples were excluded, as were those with clinical populations (e.g., populations affected by any illness, disorder, or disability) or exclusively targeting children and youth affected by overweight/obesity.

Interventions. Interventions that deliberately attempted to implement a change in physical activity, sedentary behaviour, screen time use, nutrition, or prevent overweight/obesity were include. No restriction was placed on the type of comparison. Treatment interventions (e.g., weight management interventions) were excluded.

Study type. All experimental (e.g., randomised controlled trials [RCT], cross-over designs) and quasi-experimental designs were included. Cross-sectional and cohort studies were excluded. No limitations were set regarding the duration of the intervention or the follow-up period.

Types of outcome measures. Included studies could have employed any outcome measure related to physical activity, sedentary behaviour, screen time use, nutrition, or overweight/obesity prevention. However, outcomes must have been measured on at least one child and at least one adult primarily responsible for their care.

For both reviews and intervention studies, we set no limits on the earliest publication date. We included English language, peer-reviewed full text articles that reported primary data or protocols and had been published by February, 2019. Forward searching was conducted in August, 2019.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search for review articles in Cochrane Library, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus. The search included keywords to the population (“children/young people” and “parents”), interventions (“physical activity”, “nutrition”, etc.) and study type (e.g. “review”), Supplementary Table 1 shows an example of the full search strategy used in our Scopus database search. Identified references were imported into EndNote reference manager and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by a single reviewer, with a second reviewer double-screening a random 10%. Two reviewers independently screened full-text papers, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion. Reasons for exclusion were identified at this full-text screening stage. References of included reviews were reviewed in duplicate, and references of potentially relevant intervention studies or reviews extracted into EndNote. Following de-duplication, two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and then full-text versions of interventions studies identified; reasons for exclusion were identified at this stage. Any disagreements were discussed by the two reviewers until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

The following data was extracted from each intervention study: characteristics of study design and sampling, recruitment duration and strategies used, recruitment settings, and information about reach, expressions of interest, and enrolment (see Table 1). We sent the extracted data to first and last authors of studies published within the last 5 years (i.e., since 2014), inviting them to check the extracted data for accuracy and to add any missing information, if possible. We only contacted authors of articles published within the last 5 years as we believed this was a reasonable timeframe for records to be available and researchers to have adequate recall of the study.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

| Intervention name Study (first author; year of publication; country) | Study design, study arms, aims/objectives | Families/participants (Recruitment target; target and actual sample size; mean years of age ± SD at baseline; %female) | Recruitment (duration; settings; strategies used) | Reach, expressions of interest and enrolment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No intervention name Alhassan; 2018; USA |

Pilot RCT (3 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: child-mother, child alone, or control Aims/objective: to examine the feasibility and efficacy of a mother-daughter intervention on African-American girls’ physical activity |

Recruitment target: African-American mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: 60 dyads (20 dyads/group). Actual sample size: 76 dyads (n = 28 child-mother, n = 25 child alone, or n = 23 control) Family characteristics: children: 8.3 ± 1.3 years (100%); adults: 37.4 ± 7.7 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 125 dyads Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

SHARE-AP ACTION

Anand; 2007; Canada |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or usual care control Aims/objective: to determine if a household-based lifestyle intervention was effective at reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure |

Recruitment target: families on a Six Nations Reserve (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 57 families (n = 29 intervention; n = 28 control) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 10.9 ± 2.9 years (62.5%), control – 9.9 ± 3.2 years (60.5%); adults: experimental – 41.3 ± 9.0 years (not reported), control – 37.2 ± 8.8 years (not reported) 57 families (participants: n = 88 intervention; n = 86 control); average 3 participants/family |

Duration: 48 weeks Setting: not reported Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Arredondo; 2014; USA |

Pilot trial (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to examine the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy of an intervention on physical activity and correlates of physical activity of Latina preadolescents and their mothers |

Recruitment target: Latina mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: 11 dyads Actual sample size: 11 dyads Family characteristics: children: 9.6 ± 1.1 years (100%); adults: 36.7 ± 6.2 years (100%) |

Duration: 8 weeks Setting: church (n = 1 approached, n = 1 agreed) Strategies: Announcements in Spanish from the pulpit; flyers distributed by study staff and church leaders. |

Reach = ~ 864 parishioners (the church had 1800 enrolled parishioners and 48% were Latino). Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Baranowski, Henske; 1990; USABaranowski, Simons-Morton; 1990; USA |

Randomised controlled feasibility study (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or no treatment control Aims/objective: to reduce sodium, saturated fat and total fat, and increase aerobic activity |

Recruitment target: families who self-identified as Black-American (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 96 families (n = 50 intervention; n = 46 control) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 10.6 years (51.6%), control – 10.0 years (66.1%); adults: experimental – 31.8 years (79.4%), control – 32.9 years (88.2%) 96 families (participants: n = 63 adults and 64 children intervention; n = 51 adults and 56 children intervention) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools only (n = not reported) Strategies: mail, phone calls and home visits (up to 5 visits) of all Black-American students identified in listings in the public or private school systems . |

Reach = 728 Black-American families identified Total number of expressions of interest: N/A. This was not a sample of self-presenting volunteers. Initiated expression of interest: N/A Expressions of interest rate: N/A Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Mothers and Daughters Exercising for Life (MADE4LIFE) Barnes; 2015; Australia |

Pilot RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or 6-month wait-list control Aims/objective: to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a mother-daughter program to improve in physical activity |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: 40 dyads Actual sample size: 40 dyads (n = 40 mothers, n = 48 daughters) Family characteristics: children: 8.5 ± 1.7 years (100%); adults: 39.1 ± 4.8 years (100%) |

Duration: ~ 3 weeks Setting: schools (n = not reported) Strategies: media releases, school newsletter advertisements, school presentations to students and parents, local newspapers, and local television news |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 122 families Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: ~40-41 families/week Enrolment rate: ~13 families/week |

|

Family Affair Barr-Anderson; 2014; USA |

Pilot trial (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to test the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention designed to impact obesity-related behaviours (physical activity, healthy eating, and sedentary behaviour) among African-American adolescent girls and their mothers |

Recruitment target: African-American mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 18 dyads Family characteristics: children: 12.4 ± 1.3 years (100%); adults: 36.9 ± 5.7 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: radio advertisements, flyers and recruitment letters sent to or posted at youth and family-serving organisations, health-related businesses, churches, social and professional organisations; email distribution lists; Facebook posts; word-of-mouth |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Healthy Kids & Families study Borg; 2019; USA |

Quasi-experimental protocol (2 groups, pre- and 4 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or attention-control Aims/objective: to test the effectiveness of an intervention to promote a healthier lifestyle and to prevent childhood obesity among low-income and minority families. |

Recruitment target: parent-child dyads Target sample size: 240 dyads Actual sample size: 247 dyads (n = 121 intervention, n = 126 attention-control) Family characteristics: children: 7.8 ± 2.1 years (49%); adults: 36.2 ± 7.4 years (92%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools only (n = 9 schools) Strategies: letter from the school principal placed in child’s backpack by school staff; automated telephone messages from principals; research staff presented study at school events (e.g., parent nights, family events, Parent Teacher Organization meetings); interactions with parents at school drop-off/pick-up and after-school programs |

Reach = not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 605 parents Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Back-to-Basics (B2B) Healthy Lifestyle program Burrows; 2013; Australia |

Pilot trial (1 group, pre- and post-measure) Study arm: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an after-school obesity prevention strategy for families |

Recruitment target: parent-child dyads Target sample size: 10 dyads Actual sample size: 10 dyads Family characteristics: children: 7.3 ± 3.8 years (80%); adults: 31.0 ± 7.2 years (100%) |

Duration: 2 weeks Setting: schools only (n = 1) Strategies: study flyers; word-of-mouth by school staff |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: 5 dyads/week |

|

No intervention name De Bourdeaudhuij; 2002; Belgium |

Quasi-experimental (3 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: family arm, individual arm (adolescents), or individual arm (parents) Aims/objective: to explore the differences between a family- and an individual-based tailored nutrition education programme on fat reduction |

Recruitment target: parent-child dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: family condition: n = 55 dyads (n = 110 participants); individual condition (adolescents): n = 71 adolescents; individual condition (parents): n = 47 parents. Family characteristics: children: range = 15-18 years (not reported); adults: not reported |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools only (n = 52 classes from 2 secondary schools) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

MOVE/me Muevo Project Elder; 2014; USA |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post- measures) Study arms: experimental or control Hypotheses: (1) children in the experimental arm would have lower body mass index z-scores vs. control children after 2 years; (2) children in the experimental am spend more time in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and less time sedentary, eat fewer high-fat foods and sugary beverages, and more fruits, vegetables and water vs. control children |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 541 families Family characteristics: children: 6.6 ± 0.7 years (55%); adults: not reported |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools, libraries, street fairs, recreation centres (n = not reported) Strategies: targeted phone calls using telephone numbers obtained from a research marketing company (n = 8,600); families contacted via school- and community-based recruitment efforts (n = 1,000) |

Reach = 9,607 families Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Epstein; 2001; USA |

Randomised trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: increase fruit and vegetable (FV) intake treatment condition or decrease high-fat/high-sugar intake (FS) treatment condition Aims/objective: to evaluate the effect of a parent-focused intervention on parent and child eating changes and on percentage of overweight changes in families |

Recruitment target: families (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 30 families (FV: n = 13 parents and 13 children; FS: n = 12 parents and 13 children) Family characteristics: children: FV – 8.8 ± 1.8 years (54%), FS – 8.6 ± 1.9 years (77%); adults: FV – 39.1 ± 4.1 years (92%), FS – 42.2 ± 4.8 years (92%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: physician practices (n = not reported) Strategies: physician referrals, posters, newspapers, and television advertisements |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Fitzgibbon; 1995; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to examine the effects of an obesity prevention program on eating-related knowledge and behaviour of low income, Black-American girls and their mothers |

Recruitment target: Black-American mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 20 dyads (10 dyads/group) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 11.0 ± 1.0 years (100%), control – 11.0 ± 1.0 years (100%); adults: experimental – 31.0 ± 10.0 years (100%), control – 33.0 ± 5.0 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: tutoring program (n = 1) Strategies: advertisements in tutoring newsletter |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Children First Study Fornari; 2012; Brazil |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to evaluate whether an educational program for children could improve cardiovascular risk in parents |

Recruitment target: children and their parents Target sample size: 150 parents/group Actual sample size: 197 children and 323 parents (intervention = 105 children, 162 parents; control = 92 children, 161 parents) Family characteristics: children: experimental – = 8.2 ± 1.5 years (50%), control – 9.0 ± 1.5 years (51%); adults: experimental – 38.3 ± 6.0 years (55%), control – 39.3 ± 6.7 years (53%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools only (n = 1) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Active Families in the Great Outdoors Flynn; 2017; USA |

Feasibility trial (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to determine whether changes could be observed in: duration, frequency and type of outdoor physical activities performed by families; parent social cognitive outcomes and physical activity support behaviours |

Recruitment target: families (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 16 families (N = 52 participants; n = 25 parents, n = 27 children) Family characteristics children: 10.7 ± 3.3 years (52%); adults: 41.5 ± 7.9 years (60%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: flyers, email, word-of-mouth |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 38 families Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

| Take Action French; 2011; USA |

CRCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Hypothesis: the experimental group would gain less weight and increase healthful behaviours related to energy balance over 1 year compared to the control group |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 90 households (n = 45 households/group) Family characteristics: children = not reported; adults = 41.0 years (93%) ~4 members/family (~2 adults and ~2 children/family) |

Duration: 32 weeks Setting: libraries, worksites, schools, daycare centres, health clinics, religious institutions, park and recreation centres, grocery stores, and food co-ops (n = not reported) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 723 households Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: 22-23 households/week Enrolment rate: 2-3 households/week |

|

Families Reporting Every Step to Health (FRESH) Guagliano; 2019; UK |

Feasibility trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: ‘child-only’ or ‘family’ Aims/objectives: to describe intervention and recruitment strategy; assess the feasibility and acceptability of the FRESH recruitment strategy, intervention and outcome evaluation; explore options for optimisation |

Recruitment target: families (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: 20 families Actual sample size: 12 families (n = 14 children, 18 adults) Family characteristics: children: 8.3 ± 1.7 years (50%); adults: 39.8 ± 8.2 years (61%) Whole families = 4, parent-child dyads = 6, families with an additional adult or child = 2; 2-3 members/ family (range = 2-4). |

Duration: 8 weeks Setting: schools only. N = 11 schools approached, n = 5 agreed, n = 3 declined, n = 3 no response. Recruitment from community-based organisations planned, but not implemented. Strategies: assembly delivered to students; study leaflets given to students to bring home and emailed to parents from schools; reminder email sent from schools to parents 2 weeks after assembly. |

Reach = ~437 students Total number of expressions of interest:28 families Initiated expression of interest: 23 mothers, 5 fathers Expressions of interest rate: 3-4 families/week, 5-6 families/school assembly Enrolment rate: 1-2 families/week |

|

Scouting Nutrition & Activity Program+ (SNAP+) Guagliano; 2012; USA |

Quasi-experimental (1 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objectives: to evaluate a physical activity promotion intervention with a channel of communication to parents |

Recruitment target: Girl Scout troops and their parents Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 3 troops (n = 32 children, n. = 26 adults) Family characteristics: children: 9.5 ± 1.4 years (100%); adults: 37.1 ± 5.4 years (92%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: Girl Scouts troops (n = 3 troops invited and agreed) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Active 1 + FUN Ha; 2019; Hong Kong |

RCT protocol (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to evaluate the effectiveness of a family-based intervention on parents and their childrens’ physical activity |

Recruitment target: Students and their parents (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: 204 children Actual sample size: 187 children Family characteristics: children: 9.8 ± 1.2 years (41%); adults: unknown (78%) |

Duration: ~4-6 weeks Setting: Schools only (n = 100 invited; 9 responded and agreed; n = 1 dropout) Strategies: written information was circulated to parents; face-to-face parent-researcher sessions |

Reach: unknown Total number of expressions of interest: ~229 Initiated expression of interest: unknown (not collected). Expressions of interest rate: unknown (researchers only received a confirmed list from schools) Enrolment rate: unknown (researchers only received a confirmed list from schools) |

|

Abriendo Caminos Hammons; 2013; USA |

Pilot trial (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to test the effectiveness of a family-based healthy eating program aimed to reduce obesogenic behaviours among Latino parents and children. |

Recruitment target: Latino families, only 1 target child (5-13 years) and 1 parent measured Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 73 families Family characteristics: children: 8.5 years (49%); adults: 34.4 years (100%) ~4 family members/family (range = 2-9) |

Duration: 104 weeks Setting: trailer park (n = 1) and elementary school (n = 1) with known Latino population. Strategies: flyers, announcements, and word-of-mouth. Project coordinators were Latino and fluent Spanish speakers. |

Reach: unknown Total number of expressions of interest: unknown Initiated expression of interest: unknown Expressions of interest rate: unknown Enrolment rate: < 1 family/week |

|

Fit ‘n’ Fun Dudes Program Hardman; 2009; UK |

CRCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to increase daily step counts of girls with the support of their parents to maintain increases over time |

Recruitment target: parent-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: n = 32 children (intervention: n = 14 children; control = 18 children) Family characteristics: children: 10.6 ± 0.7 years (100%); adults: 41.0 ± 4.7 years (83%). |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Hopper; 1992; USA |

CRCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: school-and-home treatment condition, school-only treatment condition, and standard treatment control condition Aims/objective: to compare the effect of including versus not including a family participation component in a school-based program to develop children’s heart-healthy exercise and nutrition habits |

Recruitment target: parents and children or children only Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: school-and-home condition: n = 45 children and 42 parents; school-only condition: n = 43 children; control condition: n = 44 children Family characteristics: children: 11.6 ± 0.7 years (not reported); adults: 37.8 ± 6.8 years (74%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Teamplay Jago; 2013; UK |

Randomised controlled feasibility trial (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or no treatment control Aims/objectives: six specific aims related to: feasibility of recruitment, retention, and data collection; Intervention development and optimisation; estimating effect sizes of outcomes of interest (e.g., physical activity, screen-viewing) and sample size for definitive trial |

Recruitment target: parents of children 6-8 years old Target sample size: between 80-340 participants Actual sample size: 48 participants (intervention: n = 25, control: n = 23) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 6-8 years (62%), control – 6-8 years (69%); adults: experimental – age not reported (100%), control – age not reported (96%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools, coffee shops, children’s centres, play groups, school playgrounds (n = not reported) Strategies: leaflets, advertisements, face-to- face recruitment |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Motivating Families with Interactive Technology (mFIT) Jake-Schoffman; 2018; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: tech or tech+ Aims/objective: to test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of 2 family-based programs targeting improvements in parent–child dyad’s physical activity and healthy eating and delivered remotely |

Recruitment target: parent-child dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 33 dyads (n = 17 tech+; n = 16 tech) Family characteristics: children: 11.0 ± 0.9 years (64%); adults: 43.0 ± 5.8 years (88%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: email announcements, flyers posted in community settings, paid newspaper ads, direct mail postcards |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 98 Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and Prevention of Adult Non communicable disease (CASPIAN) Study Kargarfard; 2012; Iran Kelishadi; 2010; Iran |

Non-RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: mother/daughter arm or student-only arm Aims/objective: to examine the effect of a physical activity program for high school girls and their mothers. |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads or students only Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: mother/daughter group: n = 206 girls and 204 mothers; student-only group: n = 60 girls) Family characteristics: children: 15.8 ± 1.0 years (100%) in mother/daughter group; 15.9 ± 1.3 years (100%) in student-only group. Adults: age not reported (100%) in either group |

Duration: not reported Setting: Schools (n = not reported) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

4-Health Lynch; 2012; USA |

Pilot RCT protocol (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or ‘best practices’ control Aims/objective: to develop, implement, and evaluate a parent-centred obesity prevention program for rural families. |

Recruitment target: children and their parents Target sample size: 75 participants/group Actual sample size: unknown Family characteristics unknown |

Duration: not reported Setting: 4-H (n = 25 4-H extension agents). Strategies: announcements and information at county fairs, announcements in 4-H newsletters, electronic and/or printed announcements to 4-H clubs, emails to 4-H listservs, and phone calls to 4-H leaders |

Reach: unknown Total number of expressions of interest: unknown Initiated expression of interest: unknown Expressions of interest rate: unknown Enrolment rate: unknown |

|

No intervention name Mark; 2013; Canada |

Pilot RCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: GameBike (experimental) or traditional stationary bike (control) Aims/objective: primarily, to compare usage of a GameBike to a traditional stationary bike placed in front of the television among parents and children |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 30 families (n = 59 adults, n = 38 children) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 6.0 ± 2.1 years (42%); control – 5.4 ± 1.7 years (42%); adults: experimental – 37.1 ± 6.6 years (52%), control – 36.6 ± 6.1 years (50%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: healthcare centres, recreation centres, daycares, preschools, and shopping malls (n = not reported). Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 58 families Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Kick Start Your Day Mohammad; 2012; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to evaluate a family-based nutrition and physical activity program targeting low-income Latino families |

Recruitment target: Latino families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 56 parents (n = 25 intervention, n = 31 control) and their children (n = not reported) Family characteristics: children: range = 6-12 years (not reported); adults: 37.0 ± 7.0 years (not reported) |

Duration: not reported Setting: community centre (n = 1) and clinic (n = 1) Strategies: flyers and brochures written in English and Spanish, presentation delivered at a parent-teacher association meeting and community leader forum |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Children, parents and pets exercising together (CPET) Morrison; 2013; UK Yam; 2012; UK |

Randomised controlled feasibility trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: experimental or no treatment control Aims/objectives: to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the CPET intervention and trial, preliminary evidence of its potential efficacy, planning and powering a future intervention, and to improve understanding of the frequency, intensity and duration of dog walking among dog owning families in Scotland |

Recruitment target: Families with dogs Target sample size: 40 families Actual sample size: 28 families (experimental: n = 16 families, control: n = 12 families) Family characteristics: children = 10.9 years (76%), adults = 44.8 years (82%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: primary schools (n = 37 approached; n = 35 agreed) Strategies: invitation letters sent to dog owning parents with children attending primary schools in one local authority area |

Reach: 350 letters sent Total number of expressions of interest: 127 families Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Dads and Daughters Exercising and Empowered (DADEE) Morgan; 2019; Australia |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or wait-list control Aims/objective: to evaluate a program designed to improve father-daughter physical activity and daughters’ fundamental movement skill competency; fathers’, daughters’ screen-time; fathers’ physical activity parenting practices |

Recruitment target: fathers and their daughters Target sample size: 86 fathers and 134 daughters Actual sample size: 115 fathers and 153 daughters (DADEE: n = 57 fathers, n = 74 daughters; wait-list control: n = 58 fathers, n = 79 daughters) Family characteristics: children: 7.7 ± 1.8 years (100%); adults: 41.0 ± 4.6 years (0%) |

Duration: 11 weeks Setting: not reported Strategies: university media release picked up by local television, radio, newspaper news outlets. |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 160 Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: 14-15 families/week Enrolment rate: ~10 families/week |

|

Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids (HDHK) Morgan; 2014; Australia Morgan, Lubans, Plotnikoff; 2011; Australia Williams; 2018; Australia |

Community RCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or a wait-list control Aims/objective: to evaluate the HDHK intervention when delivered by trained local facilitators in the community |

Recruitment target: fathers and their children Target sample size: 50 fathers and their children Actual sample size: 93 fathers and 132 children Family characteristics: children: 8.1 ± 2.1 years (45%); adults: 40.3 ± 5.3 years (0%) |

Duration: ~8 weeks Setting: schools (n = not reported) Strategies: school newsletters, school presentations, interactions with parents at school pick up, local media, and flyers distributed through local communities |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 116 Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: ~14-15 families/week Enrolment rate: ~11-12 families/week |

|

Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids (HDHK) Morgan, Lubans, Callister; 2011; Australia |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or a wait-list control |

Recruitment target: fathers and their children Target sample size: 44 fathers and their children |

Duration: ~8 weeks Setting: schools (n = not reported) Strategies: school newsletters, local media |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 107 |

| Lubans; 2012; Australia Burrows; 2012; Australia |

Aims/objective: to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of HDHK to help fathers lose weight and model positive health behaviours to their children |

Actual sample size: 53 fathers and 71 children Family characteristics: children: 8.1 ± 2.1 years (45%); adults: 40.3 ± 5.3 years (0%) |

Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: ~13 families/week Enrolment rate: ~6-7 families/week |

|

|

The San Diego Family Health Project Nader; 1989; USANader; 1992; USA Nader; 1983; USA Patterson; 1988; USA |

CRCT (4 groups, pre- and 3 post-measures) Study arms: Mexican-American experimental, Anglo-American experimental, Mexican-American control, or Anglo-American control Aims/objective: to decrease consumption of high salt, high fat foods; and increase frequency and intensity of physical activity |

Recruitment target: families (only up to 2 children and 2 adults measured) Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 206 families Family characteristics: Mexican-American experimental. Children: 12.1 ± 1.7 years (55%), adults: 37.1 ± 6.8 years (88%); Anglo-American experimental. Children: 12.1 ± 1.9 years (38%), adults: 39.4 ± 7.1 years (62%); Mexican-American control. Children: 12.0 ± 1.7 years (49%), adults: 35.6 ± 6.9 years (75%); Anglo-American control. Children: 11.8 ± 1.4 years (48%), adults: 36.9 ± 5.1 years (58%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: primary schools (n = not reported) Strategies: newspaper articles, Parent-Teacher Association meetings, community groups, and a family fun night (covered by a local TV station). |

Reach: ~6,000 children Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Behavior Opportunities Uniting Nutrition, Counseling, and Exercise (BOUNCE) Olvera; 2010; USA Olvera; 2008; USA |

CRCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: primarily, to assess the efficacy of the BOUNCE intervention for improving physical fitness and activity in Latino mother–daughter pairs |

Recruitment target: Latino mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: 50 dyads Actual sample size: 46 dyads (n = 26 experimental, n = 20 controls) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 9.9 ± 1.1 years (100%), control – 10.4 ± 1.1 years (100%); adults: experimental – 33.3 ± 4.6 years (100%), control – 38.2 ± 10.6 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: flyers mailed to homes of Latino families |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 57 parents Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Owens; 2011; USA |

Quasi-experimental (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to examine changes in physical activity and fitness in families after 3 months of home use of the Wii Fit |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 8 families (n = 21 participants) Family characteristics: children: 10.0 ± 1.6 years (50%); adults: 37.8 ± 4.9 years (78%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: local newspaper advertisement |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Etude Longitudinale Prospective Alimentation et Santé (ELPAS) study Paineau; 2008; France |

RCT (3 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: Group A (experimental), Group B (experimental), Group C (no treatment control) Hypothesis: family dietary coaching would improve nutritional intakes and weight control in free-living children and parents |

Recruitment target: families (parent-child dyad minimum) Target sample size: 295 families/experimental group and 420 families in the control group Actual sample size: 1,013 families (Group A = 297 families, Group B = 298 families, Group C = 418 families) Family characteristics: children: 7.7. years (52%); adults: 40.5 (82%) |

Duration: 16 weeks Setting: schools only (n = 54) Strategies: mailed study information |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Y Living Parra-Medina; 2015; USA |

Quasi-experimental (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to examine the impact of the Y Living Program on the weight status of adult and child participants |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 242 adults, 106 children Family characteristics: children: 12 (interquartile range: 10-14) years (49%); adults: 41 (interquartile range: 33-53) (81%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: churches, schools (n = not reported) Strategies: organisational newsletters, neighbourhood newspapers, word-of-mouth |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Choosing 5 Fruits and Veg Every Day Pearson; 2010; UK |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or no treatment control Aims/objective: to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a family-based newsletter intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents |

Recruitment target: parent-adolescent dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 49 dyads Family characteristics: children: experimental – 12.6 ± 1.0 years (44%), control – 12.3 ± 0.7 years (42%); adults: experimental – 44.4 ± 5.3 years (71%), control – 43.9 ± 3.6 years (75%) |

Duration: 16 weeks Setting: schools, universities, factories, warehouses, clubs/societies (n = not reported) Strategies: newspaper and website advertisements, posters in workplaces (universities, factories, warehouses), and letters through schools and activity clubs/societies |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Daughters and Mothers Exercising Together (DAMET) Ransdell; 2004; USA Ransdell; 2003; USA Ransdell; 2001; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: community-based or home-based experimental arms Aims/objective: to assess the effectiveness of home- and community-based physical activity interventions that target mothers and daughters to increase physical activity and improve health-related fitness |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 20 dyads Family characteristics: children: community-based – 15.2 ± 1.2 years (100%), home-based – 15.7 ± 1.5 years (100%);adults: community-based – 46.0 ± 8.5 years (100%), home-based – 44.0 ± 6.1 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: newspaper articles, local Girl Scout troop announcements, referral. |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Generations Exercising Together to Improve Fitness (GET FIT) Ransdell; 2005; USAOrnes; 2005; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: experimental or no treatment control Aims/objective: to compare a 6-month home based physical activity intervention to a control condition on physical activity and health related fitness in 3 generations of women |

Recruitment target: grandmother-mother- daughter triads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 17 triads Family characteristics: children: experimental – 10.8 ± 1.4 years (100%), control – 9.4 ± 1.5 years (100%); mothers: experimental – 37.8 ± 4.2 years (100%), control – 36.6 ± 4.2 years (100%); grandmothers: experimental – 60.7 ± 4.3 years (100%), control – 62.9 ± 4.5 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: not reported Strategies: newspaper, email and flyer advertisements, word-of-mouth |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Rhodes; 2019 CanadaQuinlan; 2015; Canada |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 3 post- measures) Study arms: physical activity education + planning (experimental) or physical activity education (control) Aims/objective: to evaluate whether a planning condition improves regular physical activity compared to an education-only control condition among families |

Recruitment target: families (minimum parent-child dyad required) Target sample size: 160 families Actual sample size: 102 families Family characteristics: children: intervention – 8.8 ± 2.3 years (50%), control – 9.1 ± 1.9 years (54%); adults: intervention – 42.2 ± 5.7 years (76%) intervention, control – 43.0 ± 5.7 years (83%) Dual-parent families = 52%; single- families = 44%; families with siblings = 29% |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools, recreation centres, health care centres, children’s recreation classes, shopping malls, and outdoor markets (n = not reported) Strategies: newspaper advertisements. Snowball recruitment was also used, where families received a CA$25 grocery store gift card if they referred another family. Recruitment was conducted by stratifying the city into regions to ensure diversity of families. |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 188 parents Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Rhodes; 2010; Canada |

Pilot RCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: standard intervention or standard intervention + planning Aims/objective: to examine the effect of a planning intervention compared to a standard condition on intergenerational physical activity in families |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 85 families Family characteristics: children: standard – range = 4-10 years (not reported) standard+ – range = 4-10 years (not reported); adults: standard – 38.6 ± 5.3 years (79%), standard+ – 39.0 ± 5.2 years (90%) |

Duration: 52 weeks Setting: daycares, recreation centres, preschools, primary schools (n = not reported) Strategies: flyers, poster advertisements |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 107 families Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: ~2 families/week Enrolment rate: ~1-2 families/week |

|

Scouting Nutrition & Activity Program (SNAP) Rosenkranz; 2010; USA Rosenkranz; 2009; USA |

CRCT (2 groups, pre- and post-measure) Study arms: experimental or standard-care control Aims/objective: to evaluate an intervention designed to prevent obesity by modifying Girl Scout troop meeting environments, and by empowering girls to improve the quantity and/or quality of family meals in their home environments |

Recruitment target: Girl Scout troops and their parents Target sample size: 8 troops with 20 girls/troop Actual sample size: 7 troops (mean = 11 girls/troop) Family characteristics: children: experimental – 10.6 ± 1.1 years (100%), control – 10.5 ± 1.3 years (100%); adults: experimental – age and % female not reported, adults: control – age and % female not reported |

Duration: not reported Setting: Girl Scouts troops (n = 7 troops) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Salimzadeh; 2010; Iran |

Quasi-experimental (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to evaluate the effectiveness of an exercise program on the body composition and physical fitness of mothers and daughters |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 35 dyads Family characteristics: children: 15.0 ± 1.6 years (100%); adults: 40.0 ± 3.8 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools only (n = 5) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: 300 students Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Schwinn; 2014; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to improve the well-being of girls living in public housing by improving dietary intake, increasing physical activity, and reducing drug use risks |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 67 dyads (n = 36 intervention, n = 31 control) Family characteristics: children: 11.9 ± 0.9 years (100%); adults: 36.2 ± 6.2 years (100%) |

Duration: 4 weeks Setting: public housing development (n = 1) Strategies: Google AdWords, public housing development newspapers, Facebook and Craigslist advertisements |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: 86 Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: 21-22 families/week Enrolment rate: 16-17 families/week |

|

Brighter Bites (BB) Sharma; 2016; USA |

Quasi-experimental (2 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: BB (experimental) or school health program (control) Aims/objective: to evaluate the effectiveness of a school-based food co-op program to increase fruit and vegetable intake, and home nutrition environment among low-income children and their parents |

Recruitment target: parent-child dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 717 dyads (n = 407 intervention, n = 310 control) Family characteristics: children: 6.2 ± 0.4 years (52%); adults: 34.3 ± 7.4 years (90%) |

Duration: 2 school years Setting: schools only (n = 12) Strategies: not reported |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: 358-359 dyads/school year |

|

No intervention name Stolley; 1997; USA |

Pilot trial (2 groups, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to assess the effectiveness of an obesity prevention program on pre-adolescent girls and their mothers |

Recruitment target: mother-daughter dyads Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 65 dyads Family characteristics: children: intervention – 9.9 ± 1.3 years (100%), control – 10.0 ± 1.5 years (100%); adults: intervention – 31.5 ± 3.4 years (100%), control – 33.7 ± 6.8 years (100%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: tutoring program (n = 1) Strategies: advertisement in tutoring newsletter, letters sent to mothers of children registered at tutoring program, presentation delivered to parents at tutoring program orientation |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

One Body, One Life Towey; 2011; UK |

Quasi-experimental (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to evaluate a family-based programme designed to prevent obesity |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 272 children and 182 parents. Family characteristics: children: 8.0 years (50%); adults: age not reported (87%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: neighbourhood groups, local fetes, community groups, general practitioner surgeries, libraries, children’s centres, print media, schools (n = not reported) Strategies: flyers, posters, newsletters, word-of-mouth, referrals from healthcare professionals, local newspapers, and making team members visible in the community (e.g., attending events, delivering ‘taster sessions’). |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

Family Eats Weber Cullen; 2017; USA |

RCT (2 groups, pre- and 2 post-measures) Study arms: experimental or control Aims/objective: to improve parent and child fruit and vegetable intake |

Recruitment target: families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 126 families (n = 92 intervention; n = 34 control) Family characteristics: children: age not reported (55%); adults: 59% < 40 years (98%) |

Duration: not reported Setting: schools, churches, health fairs, community centres (n = not reported) Strategies: flyers, radio advertisements |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

|

No intervention name Ziebarth; 2012; USA |

Quasi-experimental (1 group, pre- and post-measures) Study arms: experimental arm only Aims/objective: to evaluate a family intervention programme designed to decrease overweight and obesity in Hispanic families |

Recruitment target: Hispanic families Target sample size: not reported Actual sample size: 47 families (n = 57 adults, n = 54 children) Family characteristics: children: age and % female not reported, adults: 32 years (not reported) |

Duration: not reported Setting: local churches, medical clinics, schools, self-service laundries, and community programs (n = not reported) Strategies: posters, announcements, word-of-mouth |

Reach: not reported Total number of expressions of interest: not reported Initiated expression of interest: not reported Expressions of interest rate: not reported Enrolment rate: not reported |

Risk of bias in individual studies and across studies

We were only interested in examining the strategies used for recruiting families into family-based intervention research, which does not inherently affect the internal validity (risk of bias) of a study. Therefore, we have decided not to include a risk of bias (quality) assessment.

Summary measures and synthesis of results

As indicated above, this study focused on family-based recruitment strategies, rather than study findings, which were therefore only presented descriptively.

Phase 2 – Delphi consensus study

Study design

The Delphi procedure or technique is a group process involving the interaction between the researcher and a group of identified experts on a specified topic [23]. This procedure is appropriate for research questions that cannot be answered with complete certainty, but rather by the subjective opinion of a collective group of informed experts [24]. Here, we used a Delphi procedure to determine, through the consensus of experts, the most effective and resource efficient strategies for recruiting families into intervention studies. Ethical approval for the study was obtained in July, 2019 through MRC Epidemiology Unit departmental ethical review.

Study procedures

Two groups of experts were selected to participate in this study, and received an email invitation: a) all first and senior authors of the intervention studies identified in Phase 1, and b) known experts in the field as identified by the study team. Delphi participants were also permitted to suggest other experts for invitation. All participants were asked to complete an informed consent online prior to the start of the study.

The Delphi study included 3 rounds using an online questionnaire created in Qualtrics. To start each round, participants were sent an email containing a direct link to the online questionnaire and given 1-2 weeks to complete. One reminder was sent 3 days before the deadline. After each round a summary of the findings was fed back to the participants.

Our protocol for each round of the Delphi study was based on a similar published study [25]. In round 1, participants responded to questions related to the most recent family-based study they had conducted (e.g., recruitment strategies, recruitment duration, sample size), and to provide their top 2 strategies for recruiting families in intervention studies (see Table 2 for questions). Following the deadline, the study team then reviewed the panel’s responses to their top strategies. We then collated responses into overarching themes based on the setting recruitment occurred in (e.g., schools) and then organised similar recruitment strategies used under each overarching themes.

Table 2. Questions asked during round 1 of the Delphi procedure.

| 1. | Was the most recent family-based experimental study that you conducted a pilot/feasibility trial or full-scale trial? |

| 2. | How many families did you aim to recruit in the study? |

| 3. | How many families were enrolled in the study? |

| 4. | How much time (in weeks) was allotted for recruitment? |

| 5. | Was this enough time to recruit the number of families you aimed to recruit? |

| 6. | Was the recruitment period extended? |

| 7. | How much additional time (in weeks) was allotted for recruitment? |

| 8. | In your opinion, what are the top 2 recruitment strategies that you have used in the family-based experimental research that you have conducted?

|

| 9. | Are there any recruitment strategies that you have used in previous studies that you have stopped or plan to stop using? |

| 10. | Are there any recruitment strategies that you would like to try but have not yet used? |

In round 2, participants reviewed the recruitment strategies put forward in round 1 and rated how effective and resource-efficient they believed each strategy to be separately on 2 different 4-point Likert scales (4 = very effective/resource-efficient, 1 = not effective/resource-efficient). To rank strategies, summary scores were created in which scores for effectiveness were weighted by a factor of 2. Therefore, the weighted scores for effectiveness ranged between 2 and 8 and the scores for resource-efficiency between 1 and 4. Effectiveness was weighted more than resource efficiency as we believed effectiveness was a more important factor related to recruitment strategies. The top 10 strategies were then taken forward to round 3.

In the final round, participants were asked to rank the final 10 recruitment strategies into their individual top 10. Following completion, all rankings were summed to determine an overall rank of the strategy (i.e., lower scores indicated higher ranks).

Results

Phase 1 - systematic review findings

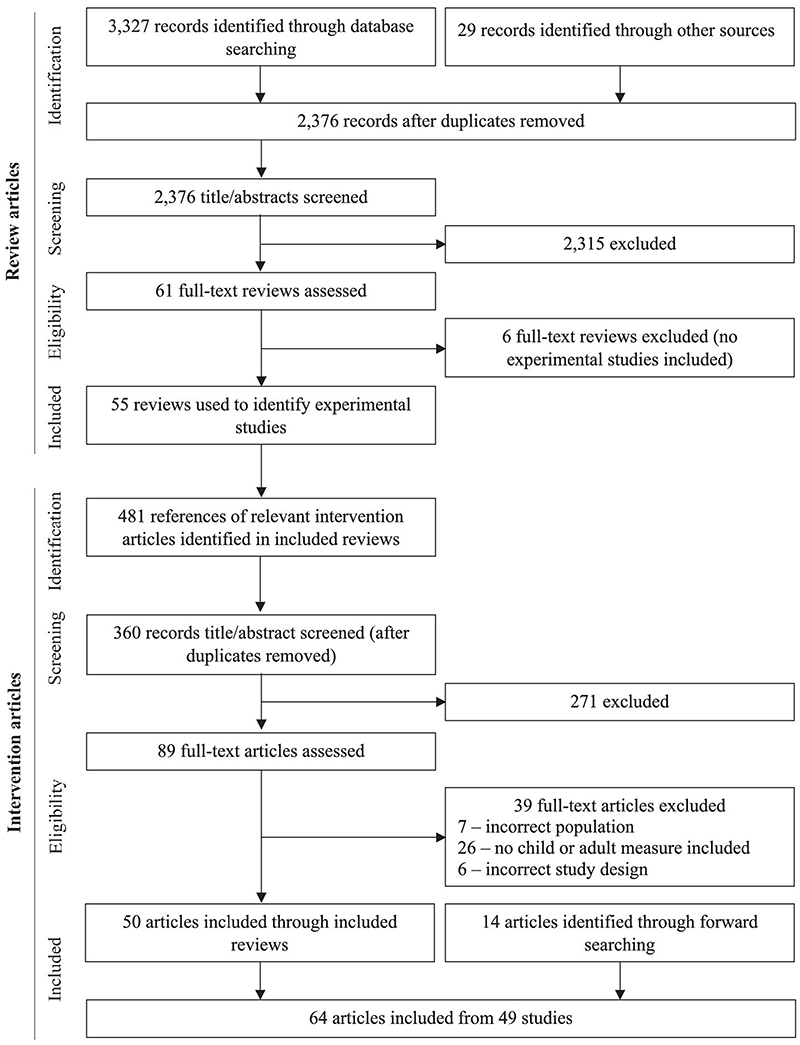

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. Fifty-five relevant reviews met inclusion criteria, from which 360 references to potentially relevant intervention studies were extracted and 50 were included. An additional 14 intervention studies were identified through forward searching, and therefore a total of 64 articles, describing 49 intervention studies, met the inclusion criteria. Study characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Of the 49 separate studies, the majority were undertaken in the United States (57%), were pilot or feasibility studies (43%), aimed to improve physical activity only (37%), and recruited parent-child dyads (53%) rather than participation of more family members. Publication dates ranged from 1983 to 2019 with 27% of included articles published in the last 5 years (i.e., since 2014; 17 of 64 articles). After attempting to contact authors of the 17 studies published in the last 5 years, we received responses for 7 of the 17 studies. Modifications were made or additional information was provided for 5 out of these 7 studies.

Figure 1. Modified PRIMSA flow diagram.

Table 1 and Table 3 provide details of all relevant recruitment data. Overall, a target sample size was presented a priori in 33% of studies with a median (interquartile range, IQR) target sample size of 120 (IQR 65-182) participants. Actual sample size was reported in 98% of studies and included a median of 100 (IQR 53-304) participants. Of the 16 studies for which target and actual sample sizes were provided, 56% recruited a sufficient number of participants. The recruitment period duration was reported in 33% of studies lasting a median of 10 (IQR 8-36) weeks. Few studies reported figures on reach (18%), expressions of interest (33%), expressions of interest rate (16%), who initiated an expressions of interest (< 1%), and enrolment rate (22%). Where reported, the median estimated reach was 437 (IQR 350-864) families of which 122 (IQR 92-174) expressed interest. The single study describing who expressed initial interest showed that in 82% of the cases these were mothers (23/28). Median weekly expression of interest rate was 14 (IQR 11-21) per week, with median enrolment rate at about 5 (IQR 2-11) families/dyads per week.

Table 3. Summary of recruitment figures from intervention studies included in the systematic review.

| Overall | Number of studies with relevant data (N = 49 studies) | |

|---|---|---|

| Target sample size (participants) | 120 (65-182) | 16 |

| Actual sample size (participants) | 100 (53-304) | 48 |

| Recruitment duration (weeks) | 10 (8-36) | 16 |

| Reach | 437 (350-864) | 9 |

| Expressions of interest | 119 (95-167) | 16 |

| Initiated expression of interest | 82% mothers | 1 |

| Expressions of interest rate (per week) | 14 (11-21) | 8 |

| Enrolment rate (families per week) | 5 (2-11) | 11 |

| Percentage of studies with under-recruitment | 38% | 6* |

Note. Median (interquartile range) values are presented unless indicated otherwise.

Only 16 of 49 studies provided a target and actual sample size, where 6 of 16 studies under-recruited.

Details on family recruitment settings and strategies was reported in 84% and 73% of studies, respectively. On average, researchers recruited from 2.2 ± 1.9 different settings and used 2.7 ± 1.2 recruitment strategies per study; there was no difference between full-scale trials, pilot/feasibility, or quasi-experimental trials in the number of recruitment settings or strategies used.

School-based recruitment was the most common recruitment setting, with community-based recruitment second. Community-based recruitment settings included: churches, recreation centres, play groups, libraries, fairs/fetes, sports clubs, 4-H, daycares, preschools, tutoring programs, malls, grocery stores, farmer’s markets, café’s, trailer parks, and laundromats. Recruitment also occurred through employers, primary care (e.g., general practitioners, health centres, other health-related businesses), and through print/electronic media.

Across settings, the most commonly used recruitment strategies included disseminating study information through leaflets, posters, or newsletters. School-based recruitment had the most recruitment strategies specific to the setting and included: leaflets, posters, newsletters, letters from the head teacher (i.e., principal), research teams presenting study information to students and parents at assemblies, research teams presenting study information at other school events (e.g., parent teacher association meetings), research teams soliciting parents during pick-up/drop-off. Local newspapers and referral-based recruitment (e.g., word-of-mouth) were also popular recruitment strategies. Less commonly reported recruitment strategies included using: electronic/digital media (e.g., television, radio, social media, Google AdWords, Craigslist), face-to-face recruitment (e.g., home visits, community demonstrations), mail, phone calling, and distribution lists (e.g. via marketing companies).

Phase 2 – Delphi study

We invited 107 experts to participate in the Delphi study representing all inhabited continents. Twenty-three experts actively declined as they either were no longer conducting family-based research (n = 3), did not have the time (n = 2), or no reason (n = 18). Six invitations bounced and no other email address was identified. Thirty-five participated in at least one round of the study; only 13 completed all rounds. Most participants were experienced researchers (full/associate/assistant professors, lecturers/senior lecturers; 82.8%), and most were from North America (71.4%) followed by Europe (11.4%), Australia/Oceania (8.6%), Asia (5.7%), and South America (2.9%).

Findings

Round 1 – overview of experience with recruitment settings and strategies

Twenty-one participants provided information in round 1; Table 4 summarises the median (interquartile range) recruitment duration and sample sizes of their family-based studies. The participants submitted 36 different recruitment strategies which fell into 6 overarching themes: school-based strategies (n = 4 Delphi participants recruited in schools), print and electronic media strategies (n = 8), community settings-based strategies (n = 7), primary care-based recruitment strategies (n = 4), employer-based strategies (n = 3), and referral-based recruitment (n = 3). See Supplementary Table 2 for an overview of the 36 recruitment strategies.

Table 4. Summary of Delphi participants’ responses to recruitment experiences.

| Overall | Feasibility/ pilot trials | Full-scale trials | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (N) | 21 | 11 | 10 |

| Target sample size | 80 (60-210) | 60 (45-70) | 225 (170-486) |

| Actual sample size | 79 (41-180) | 41(37-65) | 190 (131-375) |

| Initial recruitment duration (weeks) | 12 (7.5-52) | 8.5 (6-12) | 52 (10-68) |

| Percentage of studies where recruitment was extended | 33% | 36% | 30% |

| Recruitment extension duration (weeks) | 20 (8-37.5) | 8 (8-11) | 48 (37.5-50) |

| Enrolment rate (families per week) | 4 (2-9) | 3 (2-6) | 8(2-18) |

| Percentage of studies with under-recruitment | 62% | 55% | 70% |

Note. Median (interquartile range) values are presented unless indicated otherwise.

School-based recruitment

School-based recruitment strategies included study information distributed by: hard copy leaflets to parents via children, school newsletters, letters from head teachers on behalf of research team, leaflets via email (e.g., ParentMail) or other third party companies (e.g., Peachjar), assemblies to students and/or parents, students’ diary/agenda, research team attending parent meetings (e.g., orientation meetings, PTA meetings) or other school events (e.g., sports day), hosting parent/researcher nights or after school ‘drop in’ sessions, speaking to parents during pick up time.

Generally, most Delphi participants were successful at gaining approval from someone at most schools they approached to distribute study information. However, gaining approval could be time consuming and included multiple emails, phone calls, and/or face-to-face meetings (e.g., with head teachers, physical education coordinators, parent representatives). Some reported that, in future, they planned to either stop recruiting in schools or stop using passive recruitment strategies in schools (e.g., sending hard copy leaflets home with children to give to their parents). Staff time was considered a major resource requirement for recruiting in schools (e.g., searching for schools, visiting schools, travel time, assemblies/meetings preparation). In addition, many reported having to make multiple emails, phone calls, and/or face-to-face meetings for permission to distribute study information. Other resource requirements reported for school-based recruitment were travel costs (e.g., petrol, car hire), printing costs, and postage costs.

Print and electronic media-based recruitment

Participants reported using advertisements or stories about their study printed in magazines, newspapers, or other local publications as effective print-based recruitment strategies. Regarding recruitment strategies using electronic media, Delphi participants reported the following strategies as their most effective: social media posts (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) radio, television news, e-blasts (e.g., via university news, third party media groups, corporate mailing lists), and electronic newsletters.

Disseminating study information through social media was the strategy that the most participants planned to implement in future. They reported that print and electronic media were wide-reaching and generally inexpensive to use. However, those with experience with this recruitment strategy reported low and slow response rates. Creating regular content on social media platforms or newsletters (e.g., update posts, quarterly newsletter, blogs) was considered more beneficial than one-off posts, advertisements, or newsletters. Caution was raised that some media-driven strategies can be less targeted than others (e.g., posts in social media groups, television advertisements/stories), which can lead to a lot of interest from ineligible participants (and increased staff requirements). Staff time was considered the greatest resource requirement (e.g., searching for online groups/communities, creating content, increased eligibility checking).

Community settings-based recruitment

The strategies applied in community settings-based recruitment were hard copy leaflets or pull-tab posters, speaking to parents during pick up time after community clubs, using pop-up stands at local events to speak to families, and electronic neighbourhood bulletin boards. A wide variety of recruitment settings were reported, including churches, local museums, summer camps, Scouts/Guides, YMCA/YWCA, after-school programs, swimming pools, local events, local markets, Parkrun, newsagents, shopping centres, community centres, electronic neighbourhood bulletins, and local businesses.

Generally, reports indicated that recruiting in community settings was unpredictable, with high yields at some events and no interest at another. It was reported to be very time consuming to find appropriate places to recruit and stay on top of upcoming local events (and gaining approval to be at those events to recruit). Having staff attend events (e.g., local market, shopping centre) was also time consuming and generally occurred outside of normal working hours. Some participants planned to stop recruiting in some settings, specifically newsagents, community centres, and shopping centres because of the time investment required and poor yield. However, under some circumstances, community settings-based recruitment was suggested to be particularly effective, especially if the intervention is directly or partly tied to the recruitment setting. Some suggested that having outgoing staff could be important to engage families and it may be beneficial to target parents while they are waiting for their children to complete an activity (e.g., during swimming lessons). Again, staff time was the biggest resource requirement (finding appropriate locations to recruit and events to attend, gaining approval to attend, and attending and distributing recruitment material). Other resource requirements reported for community settings-based recruitment were costs associated with printing, postage, travel, and equipment (e.g., pop up gazebo, banners).

Employer-based recruitment

Employer-based recruitment strategies included hard copy leaflets displayed in employee common areas (e.g., staff kitchen) or emails to employees from within an organisation on behalf of the research team (e.g., an email sent from human resources to employees within an organisation).

Generally, most participants found employer-based recruitment very time consuming and had low levels of success at reaching and gaining approval from someone within an organisation to distribute study information. Recruitment in this setting allows a researcher to directly expose family decision makers (i.e., parents) to study information, however, it is quite untargeted as many will be ineligible. Staff time was considered the major resource requirement for recruiting employers as many participants reported having to make multiple emails and phone calls (mostly to generic emails or numbers) for permission to distribute study information. Costs associated with travel, printing, and postage need to be considered.

Primary care-based recruitment

Recruitment strategies used during primary care-based recruitment included hard copy leaflet displayed in general practitioners’ offices, letters sent from general practitioners or health care providers on behalf of research team, phone calls from health care providers on behalf of research team, letters or phone calls from research team directly to potential participants.

Gaining access to electronic health records was considered a very effective way to identify potential participants, but not necessarily for reaching participants as their contact information was sometimes not current. Approaches that were deemed minimally effective included letters about the study sent from healthcare providers to potential participants. It was cautioned that primary care-based recruitment can be very expensive (e.g., to access electronic medical records, time/reimbursement of the health care provider or general practitioners) and technically challenging.

Referral-based recruitment