Abstract

Objective

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by ischemic necrosis of the intestinal mucosa, mostly affecting premature neonates. Management of NEC includes medical care and surgical approaches, with supportive care and empirical antibiotic therapy recommended to avoid any disease progression. However, there is still no clear evidence-based consensus on empiric antibiotic strategies or surgical timing. This study was aimed to review the available evidence on the effectiveness and safety of different antibiotic regimens for NEC.

Study Design

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and CINAHL databases were systematically searched through May 31, 2020. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized interventions reporting data on predefined outcomes related to NEC treatments were included. Clinical trials were assessed using the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials, while the risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions was evaluated using the ROBINS-I tool. The certainty in evidence of each outcome’s effects was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach.

Results

Five studies were included in this review, two RCTs and three observational studies, for a total amount of 3,161 patients. One RCT compared the outcomes of parenteral (ampicillin plus gentamicin) and oral (gentamicin) treatment with parenteral only. Three studies (one RCT and two observational) evaluated adding anaerobic coverage to different parenteral regimens. The last observational study compared two different parenteral antibiotic combinations (ampicillin and gentamicin vs. cefotaxime and vancomycin).

Conclusion

No antimicrobial regimen has been shown to be superior to ampicillin and gentamicin in decreasing mortality and preventing clinical deterioration in NEC. The use of additional antibiotics providing anaerobic coverage, typically metronidazole, or use of other broad-spectrum regimens as first-line empiric therapy is not supported by the very limited current evidence. Well-conducted, appropriately sized comparative trials are needed to make evidence-based recommendations.

Keywords: necrotizing enterocolitis, empiric antibiotic therapy, systematic review, neonate, VLBW

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by ischemic necrosis of the intestinal mucosa, mostly affecting premature neonates.1–4

Incidence of NEC in the United States is estimated to be 1 to 3/1,000 live-births,5 but there are no accurate epidemiological data from low-middle income countries (LMIC).1,6,7

Pathogenesis of NEC is complex and multifactorial, including several risk factor such as prematurity, bacterial colonization of the gut, and formula feeding.8

Overall mortality ranges between 10 and 30% of affected neonates, reaching 50% in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants.8 In survivors, NEC could lead to life-threatening complications such as intestinal strictures, short bowel syndrome, and developmental delay.9–11

Management of NEC includes medical care and surgical approaches, with supportive care and empirical antibiotic therapy recommended in order to avoid any progression of the disease.12 However, there is still no clear evidence-based consensus on empiric antibiotic strategies or surgical timing.

Antimicrobial regimens administered for NEC include narrow and broad-spectrum antibiotics as single or combination therapy against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.13–16

In 2010, the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommended ampicillin associated with gentamicin and metronidazole, ampicillin with cefotaxime, and metronidazole or meropenem, with avoidance of clindamycin in neonates due to increasing resistance of Bacteroides fragilis.17

The “Recommendations for Management of Common Childhood Conditions” (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012) suggest intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) ampicillin (or penicillin) and gentamicin as first-line antibiotic treatment for ten days, with vancomycin plus cefotaxime as a suitable alternative, even though this regimen is more expensive and not applicable as the first choice in low-middle income countries. These recommendations also state there is no evidence for the addition of anaerobic coverage in NEC. Furthermore, three studies that directly compared antibiotic regimens in NEC were explored and the quality of evidence was graded low or very low.14,18,19

In the same year, Shah and Sinn published a Cochrane systematic review comparing the efficacy of different antibiotic regimens in preventing mortality and the need for surgery in neonates with NEC including two of the trials mentioned above.14,18 However, there was insufficient evidence to recommend a particular antibiotic regimen.20

This study systematically reviews the available evidence on the effectiveness and safety of different antibiotic regimens commonly administered to neonates with NEC using modern tools to critically appraise papers’ quality and to assess the level of certainty in evidence for the effects of different antibiotic regimens.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Search Strategy

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21 MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE [R] ALL from 1946 to May 31, 2020) EMBASE (Embase from 1974 to May 31, 2020), Cochrane CENTRAL (Issue 12 of 12, May 2020), and CINAHL (CINAHL from 1982 to May31,2020) databases were systematically searched using a strategy combining the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and free-text terms for antibiotics AND necrotizing enterocolitis AND neonates. The last search conducted was on May 31 2020. The full search strategy is available in the Supplementary Material (available in the online version).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized studies of interventions reporting data on predefined outcomes (mortality, need for surgery/bowel perforation, and strictures formation) related to an antibiotic treatment for NEC in neonates and infants were included. Studies reporting data on other (non-NEC) infections or with no data on NEC were excluded.

Reference list from eligible articles was reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies.

This search was limited to studies that included human patients. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded. Review articles, case series, letters, notes, conference abstracts, and opinion articles were excluded.

Two reviewers (D.D. and A.G.) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of retrieved articles to assess the eligibility of studies for inclusion. Duplicate references were removed and disagreements were resolved by a consensus to generate the final list of papers.

Data Extraction

Data on each publication meeting inclusion criteria were extracted using a specific form designed by one reviewer (D. D.) and checked by the other reviewer (A.G.); disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data on study characteristics (study design), participants, antibiotic treatment, the proportion of participants with events of interest (e.g., death or surgical intervention), and outcome measures were extracted.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Clinical trials were assessed using the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) tool for randomized trials.22 The risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions was evaluated using the ROBINS-I tool.23

The bias assessment was done independently for each study by two reviewers (D.D. and J.A.). For each criterion, the included studies were classified as high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias; disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Summaries of Evidence

The certainty in evidence of effects for each outcome was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach24 into four categories: high, moderate, low, or very low.

Two reviewers (D.D. and J.A.) independently assessed the evidence available for each outcome; disagreements were resolved by consensus. The quality rating of each study did not affect the inclusion in this review but the quality of outcomes was considered in the synthesis of results in the form of the overall certainty in the evidence of effects.

Synthesis of Results

Due to high variation in study design and antimicrobial regimens, results were summarized narratively. For consistency, all results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) or risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for observational studies and RCTs, respectively.

Results

Study Selection Process

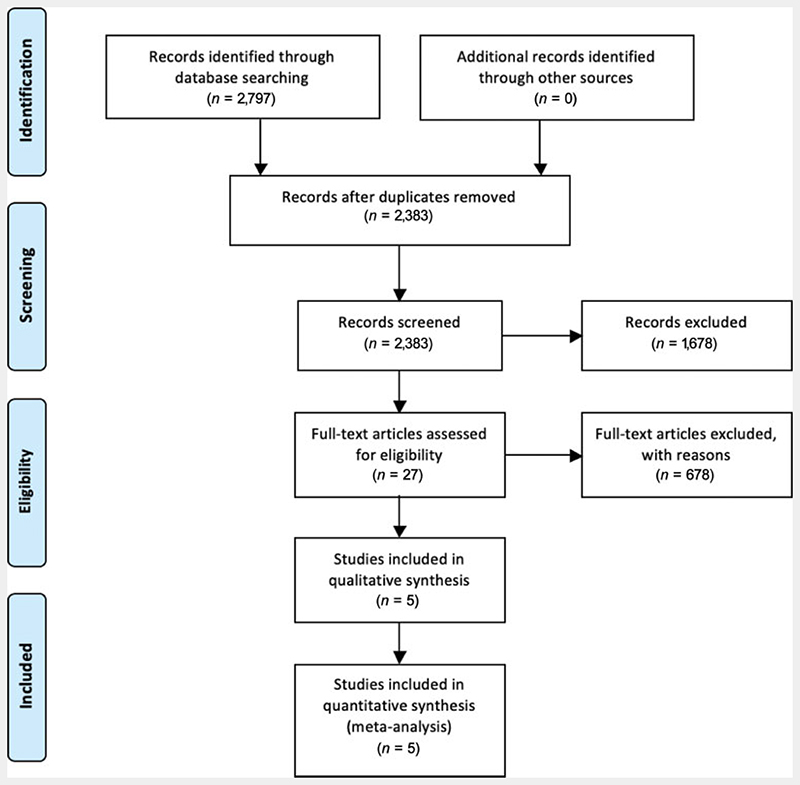

The flowchart in Fig. 1 summarizes study selection conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines.21 Five studies met the inclusion criteria.14,18,19,25,26

Fig. 1. Flowchart and study selection according to PRISMA guidelines. PRISMA, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study Characteristics

Three papers were set in the United States, one in Canada and one in South Korea. The study sample size varied from 20 patients14 to 2,78025 with 3,161 patients included through all the studies. Two studies were RCTs,14,18 while the other three were observational studies.19,25,26

Four studies (two RTCs and two observational studies) 14,18,19,26 adopted a standardized definition of NEC according to Bell’s criteria for patient inclusion, while one included all patients who received a diagnosis of NEC by the treating physician.25

One RCT compared the outcomes of parenteral (ampicillin plus gentamicin) and oral (gentamicin) treatment with parenteral only.14 Three studies (one RCT18 and two observational25,26) evaluated adding anaerobic coverage to different parenteral regimens. The other observational study compared two different parenteral antibiotic combinations (ampicillin and gentamicin vs. cefotaxime and vancomycin).19

Mortality and stricture formation were assessed in four studies,14,18,19,25 while all the included papers evaluated the need for surgery.

Risk of Bias Assessment for Clinical Trials

The risk of bias assessment for both RCTs is summarized in Table 1. Selection, performance, detection, attrition, and other bias have been assessed. Both studies resulted in overall high risk of bias.

Table 1. Risk of bias assessment for randomized controlled trials by Faix et al18 and Hansen et al14.

| Selection bias | Random sequence generation | Low risk | Low risk |

| Allocation concealment | High risk | Low risk | |

| Performance bias | Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear | Unclear |

| Detection bias | Blinding of outcome assessment | Low risk | Unclear |

| Attrition bias | Incomplete outcome data | Unclear | Unclear |

| Reporting bias | Selective reporting | Unclear | |

| Other bias | Anything else, ideally prespecified | High risk | |

| Overall bias | High risk |

The RCT by Faix et al enrolled 42 preterm infants to receive (IV) ampicillin and gentamicin or ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin. There was no difference in age or weight between the two arms (mean gestational age [GA] 29.2 ± 2.7 weeks with mean birth weight [BW] of 1,290 ± 560 g in the clindamycin group vs. 29.6 ± 3.7 weeks with mean BW of 1,310 ± 560 g in the control group). NEC’s diagnosis was made at the same time in both groups (29.6 ± 23.2 vs. 26.6 ± 24.7 days) with a standardized approach based on Bell’s criteria. In this study, no statistically significant difference was found for mortality rate between the two treatment arms (4/20 vs. 4/22, RR = 1.10 [0.32–3.83]) and no difference in the incidence of gangrene/perforation (4/20 vs. 2/22, RR = 2.20 [0.45–40.74] was found. Higher incidence of stricture formation (6/15 vs. 1/18, p = 0.022) and a longer time to reinstitution of enteral feeding (22.3 vs. 6.8 days, p < 0.05) were observed in the clindamycin group.18

In the trial developed by Hansen and colleagues, 20 infants with NEC were randomized to receive parenteral ampicillin and gentamicin or parenteral ampicillin and gentamicin with enteral gentamicin. The two arms were similar for GA (mean GA = 34.7 ± 1.3 vs. 35.6 ± 1.3 weeks), BW (mean BW of 2,220 ± 295 vs. 2,180 ± 198 g), and time to diagnosis (5.9 ± 1.3 days). All patients were diagnosed with NEC disease according to Bell’s staging criteria. The primary outcome studied was mortality, with no difference between treatment groups (1/10 vs. 2/10, RR = 0.5 [0.0535–4.6720]). No statistical difference was found for secondary outcomes perforation (1/10 vs. 2/10, RR = 0.5 (0.0535–4.6720), strictures formation (0/10 vs. 2/10, RR = 0.2 [0.0108–3.7051] or persistent ileus (1/10 vs. 0/10).14

Risk of Bias Assessment for Observational Studies

The risk of bias assessment for non-RCTs is summarized in Table 2. Bias due to confounding, selection of participants, interventions, deviation from intended intervention, missing data, measurements of outcomes, and selection of reported results have been assessed. Two studies resulted in overall moderate risk of bias,25,26 one with critical risk.19

Table 2. Risk of bias evaluation for the non–randomized controlled trials by Autmizguine et al,25 Luo et al,26 and Scheifele et al19.

| Bias due to confounding | Moderate | Moderate | Serious/critical |

| Bias in selection of participants into the study | Low | Low | Serious/critical |

| Bias in classification of interventions | Serious/critical | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bias due to deviation from intended interventions | Low | Low | Low |

| Bias due to missing data | Low | Moderate | Serious/critical |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Bias in selection of the reported result | Low | Serious/critical | Serious/critical |

| Overall bias | Moderate | Moderate | Serious/critical |

Autmizguine et al retrospectively identified all VLBW infants with medical or surgical NEC discharged from 348 neonatal intensive care unit (NICUs) between 1997 and 2012. A total of 1,390 infants who received anaerobic antimicrobial coverage were matched with 1,390 infants not exposed. Mean GA and BW were similar in both groups (27 weeks’ GA and BW of 946 g). In this study, the NEC diagnosis was not performed using Bell’s criteria but only based on physician opinion. Death, strictures, and the combined outcome of strictures or death were considered. No difference in mortality was reported between the two treatment groups, but in the subgroup with surgical NEC those treated with anaerobic antibiotics suffered significantly lower mortality (OR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.52–0.95). No significant difference was reported in the combined outcome of death or strictures, but strictures as a single outcome were more common in the anaerobic antimicrobial therapy group (OR = 1.73; 95% CI: 1.11–2.72).25

From 2008 to 2015, Luo and colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study based on the propensity score (PS = 1:1) matching to evaluate the effect of broad-spectrum antibiotics plus metronidazole therapy on preventing the deterioration of NEC from stage II to stage III in full-term and near-term infants.26

The diagnosis of NEC was based on modified Bell’s staging criteria. All infants who received broad-spectrum antimicrobials were divided into two groups, with and without metronidazole treatment. Risk factors associated with deterioration of stage II were further analyzed by a case-control study in the PS-matched cases. Before PS-matching, a total of 229 infants met the inclusion criteria. The demographic features were similar between the groups with (155/229) and without (74/229) metronidazole, while the deterioration of NEC rate was higher in the group treated with metronidazole (18.1% [28/155] vs. 8.1% [6/74]; p = 0.048). After PS matching, 73 pairs were matched, still with no significant differences between the two groups. NEC’s deterioration rate in infants treated with metronidazole was not lower than those who did not receive it (15.1 vs. 8.2%; p = 0.2). From the logistic regression analysis, it appeared that risk factors in the progression of NEC from stage II to III were sepsis (OR = 3.75, 95% CI: 1.7–11.99; p = 0.03), need for blood products or transfusion (OR = 8.00, 95% CI: 2.37–27.09; p = 0.001), and need of longer time for nasogastric suction (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00–1.21; p = 0.04).26

Scheifele et al compared 90 infants during two different study periods. Forty-six NEC cases during 1982 to 1983 received ampicillin plus gentamicin while 44 cases included during 1984 to 1985 received cefotaxime and vancomycin. Both groups were similar for GA and BW (mean BW = 1,828 vs. 1,980 grams), and Bell’s criteria were adopted to stage NEC disease. Besides mortality rate, this study assessed differences in early complications (e.g., need for surgery for peritonitis or protracted illness) or late complications (e.g., feeding intolerance or strictures formation). No differences were reported in any of these outcomes for neonates of birth weight >2,200 g. For infants with lower birth weight, better outcomes were reported in the group treated with cefotaxime and vancomycin. The mortality rate was lower in this group (p = 0.048), as were the need for surgery, peritonitis, and other major complications.19

Assessment of Certainty in Evidence

One RCT18 and one observational study25 compared the effect of adding anaerobic coverage to the standard regimen of ampicillin plus gentamycin on mortality, need for surgery/bowel perforation, and stricture formation. Despite no serious inconsistency, the certainty of evidence of effect for each outcome was graded very low due to serious limitations in methods for both studies (nonblind intervention in the RCT while in the observational study, NEC diagnosis was not based on standardized criteria but was assigned by the treating physician with a potential overlap of spontaneous intestinal perforation and NEC) and low precision with wide CIs around effect estimates. The assessment of certainty in evidence for ampicillin plus gentamicin regimen versus ampicillin, gentamicin, and anaerobic coverage is reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Assessment of certainty in evidence for Ampicillin plus gentamicin versus Ampicillin, gentamicin and anaerobic coverage18,25.

| Mortality | 2 | 1 RCT 1 observational study |

Serious limitationa | No serious inconsistency | From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 2,822 (2) | 311/1,410 | 342/1,412 | 0.91 (0.80–1.04) | Very low |

| Need for surgery/bowel perforation | 2 | 1 RCT 1 observational study |

Serious limitationa | No serious inconsistency | From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 2,116 (2) | 130/1,057 | 123/1,059 | 1.16 (0.92–1.46) | Very low |

| Stricture | 2 | 1 RCT 1 observational study |

Serious limitationa | No serious inconsistency | From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 2,813 (2) | 59/1,405 | 32/1,408 | 1.85 (1.21–2.82) | Very low |

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; GRADE, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Randomized controlled trial: single unit, Blinding of randomization: yes (concealed envelopes). Blinding of intervention: no. Complete follow-up: yes. Blinding of outcome: yes (radiologists interpreting the reports were unaware of the treatment assigned). Observational study: the diagnosis was not based on standardized criteria but was assigned by the treating physician.

Note: Potential overlap of spontaneous intestinal perforation and necrotizing enterocolitis diagnosis in the data set.

Only one RCT14 evaluated adding oral gentamicin to an ampicillin plus gentamicin parenteral regimen. The certainty of evidence for all three analyzed outcomes was graded very low due to serious limitations such as very small sample size, unclear blinding of outcomes, and low precision. The assessment of certainty in evidence for ampicillin plus gentamicin regimen versus ampicillin, gentamicin, and oral gentamicin is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Assessment of certainty in evidence for ampicillin plus gentamicin versus ampicillin plus gentamicin and oral gentamicin14.

| 14 Quality assessment | Study event rates | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 1 | 1 RCT | No serious limitationsa | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 20(1) | 1/10 | 2/10 | 0.5 (0.0535–4.6720) | Very low |

| Need for surgery/ bowel perforation | 1 | 1 RCT | No serious limitationsa | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 20(1) | 1/10 | 2/10 | 0.5 (0.0535–4.6720) | Very low |

| Stricture | 1 | 1 RCT | No serious limitationsa | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 20(1) | 0/10 | 2/10 | 0.2 (0.0108–3.7051) | Very low |

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; NA, not available; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Randomized controlled trial, single unit. Blinding of randomization: yes. Blinding of intervention: yes. Blinding of outcome: unclear.

One observational study19 compared a broad-spectrum combination of cefotaxime plus vancomycin to a standard ampicillin and gentamicin regimen. Five infants in the ampicillin/gentamicin group received an additional antibiotic (clindamycin or vancomycin) 48 or more hours after onset of symptoms, in response to results of cultures of blood or peritoneal fluid. These infants were not excluded from the analysis.

In this case, the certainty of evidence for all the three outcomes was graded very low due to very serious limitations and low precision. The assessment of certainty in evidence for cefotaxime plus vancomycin versus ampicillin and gentamicin is reported in Table 5.

Table 5. Assessment of certainty in evidence for cefotaxime plus vancomycin versus ampicillin and gentamicin19.

| Quality assessment | Study event rates | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 1 | Observational study | Very Serious limitation a | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 90(1) | 0/44 | 5/46 | 0.0949 (0.0054–1.6681) | Very low |

| Need for surgery/bowel perforation | 1 | Observational study | Very Serious limitation a | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 90(1) | 7/44 | 14/46 | 0.5227 (0.2331–1.1723) | Very low |

| Stricture | 1 | Observational study | Very Serious limitation a | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 50(1) | 6/26 | 8/24 | 0.6923 (0.2811 1.7053) |

Very low |

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; NA, not available; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Five infants in the ampicillin/gentamicin group received an additional antibiotic (clindamycin or vancomycin) 48 or more hours after onset, in response to results of cultures of blood or peritoneal fluid. These infants were not excluded from analysis but probably benefited from the additional drug.

Finally, a retrospective study26 evaluated adding metronidazole for anaerobic coverage to different broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatments in preventing deterioration of NEC from stage II to stage III. In this case, the only outcome analyzed was the need for surgery since stage III includes NEC with pneumoperitoneum or large amounts of ascites, or someone who requires bowel surgery if medical therapy fails within 48 hours. The certainty of evidence was graded very low due to very serious limitations and low precision. Broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens analyzed in this study could also include piperacillin–tazobactam and meropenem which already have activity against anaerobic bacteria. Moreover, patients receiving metronidazole for 4 days were considered in the group without anaerobic coverage. The assessment of certainty in evidence for broad-spectrum antibiotics versus broad-spectrum antibiotics plus metronidazole in Table 6.

Table 6. Assessment of certainty in evidence for broad-spectrum antibiotics versus broad-spectrum antibiotics plus metronidazole26.

| Quality assessment | Study event rates | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for surgery/bowel perforation | 1 | Retrospective study | Very serious limitationa | NA Single study |

From high income setting | Not significant, with wide Cl | 229 (1) | 28/155 | 6/74 | 2.23 (0.96–5.15) | Very low |

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; GRADE, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NA, not available.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics regimens include piperacillin–tazobactam and meropenem that already have activity against anaerobic bacteria. Patients receiving metronidazole for 4 days have been considered in the group without anaerobic.

Discussion

This study was conducted to review all published studies on the effectiveness and safety of different antibiotic regimens administered in neonates with NEC. In 2012, Shah and Sinn stated insufficient data to recommend a specific antibiotic regimen and underlined the need for a large RCT to address this issue. In their systematic review, they included only two RCTs with a total of 62 patients. After 8 years, no specific RCT on the treatment of NEC has been performed. To update the previous systematic review,20 randomized, nonrandomized control trials and observational studies were included in this study and the GRADE approach was adopted to assess rating certainty in evidence and grading strength of recommendations.

This systematic review identified five papers: two RCTs and three observational studies with 3,161 patients included in all the studies.

The mortality rates reported ranged between 8 and 23% in the different studies and the variability could be mainly attributable to infants’ age and NEC staging of the included populations.

There is still an open debate on the need for anaerobic antimicrobial therapy for NEC with the WHO reporting a lack of data to judge potential benefits or risks of metronidazole. Even if the actual efficacy has not been assessed yet, its addition is common practice for coverage of anaerobic bacteria.27 Indeed, the role of anaerobic bacteria in neonates with NEC is unclear, possibly leading to the invasion of the intestinal mucosal and regulating inflammatory response.28–30

In both Faix et al and Autmizguine et al studies, the addition of anaerobic coverage did not result in statistically significant differences in mortality or the incidence of gangrene/perforation. Autmizguine et al did find that in a subgroup of patients with surgical NEC treated with anaerobic antibiotics, mortality was significantly lower; however, certainty in evidence for this assumption from GRADE approach resulted very low.18,25

In contrast, in the RCT conducted by Faix et al, strictures were reported for patients included in clindamycin arms.18 It is worth reminding that in 2010, the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America suggest avoiding the use of clindamycin in neonates with NEC due to increasing resistance of B.fragilis despite a lack of sufficient data on this risk.17

Luo et al retrospectively evaluated the effect of broad-spectrum antibiotics with or without metronidazole therapy on the need for surgery in full-term and near-term infants,26 showing no difference between the two groups in the clinical deterioration rate. However, it should be considered a moderate risk of bias study due to the design and the high number of confounders. First, the authors defined as broad-spectrum antibiotics semisynthetic penicillin, cephalosporin, carbapenems, vancomycin not considering that piperacillin–tazo-bactam, and meropenem already have activity against anaerobic bacteria. Second, patients receiving metronidazole for 4 days were included in the group without anaerobic coverage, not considering that the effect of an anaerobic drug in a fast-evolving disease, like NEC, could impact patient outcomes.

The pathogenesis of NEC is complex and multifactorial. Different risk factors have been demonstrated in development of NEC and various animal models have been proposed to understand their pathogenetic role better. Most important factors include: intestinal immaturity, altered immune response, mucosal barrier dysfunction, bacterial colonization and dysbiosis, formula feeding. Specific molecular regulators and cytokine expression (such as toll-like receptor 4 [TLR4], platelet-activating factor [PAF], interleukin 10 [IL-10], transforming growth factor-beta [TGF-beta], etc.) have been recently studied.8,31 All of these can lead to intestinal inflammation with mucosal ischemia and subsequent necrosis, bacterial translocation, and sepsis, with progression of NEC and clinical deterioration. Thus, broad-spectrum antibiotics with anaerobic coverage could be a reasonable option for patients with NEC who need surgical treatment. However, the certainty of evidence is very low to make firm assumptions and, overall, anaerobic coverage does not seem to reduce patient mortality or decrease the risk of deterioration in medical NEC.

Different studies have demonstrated the presence of abnormal intestinal microbiota VLBW neonates’stools, including both gram-negative and non–gram-negative bacteria, with a predominance of potentially pathogenic species.32–34 This could explain the lack of anaerobic coverage protective effect. With the assumption, other authors proposed to use broader spectrum regimens, with no anaerobic activity, instead of ampicillin plus gentamicin.

Despite evidence of the possible pathogenetic role of bacteria and neonates’ clinical septic appearance with NEC, a concomitant positive blood culture is uncommon in these patients. The high prevalence of gram-negative strain could be a reason for antimicrobial choice.35,36

Hansen and colleagues explored the possibility of adding oral gentamicin to the standard regimen based on ampicillin and gentamicin in an RCT.14 No difference was observed in mortality, perforation, and strictures formation. Furthermore, the dose prescribed in this population was higher than recent guidelines recommendations with the risk of increased drug toxicity without outcomes improvement. The number of patients recruited in this study was very low and the certainty of evidence for all the analyzed outcomes was graded very low.

The observational study by Scheifele et al compared ampicillin plus gentamicin versus cefotaxime and vancomycin. No differences were reported for mortality, need for surgery, and other major complications for neonates of BW >2,200 g, but there was an improvement for all these outcomes for neonates with BW <2,200 g.19 The observational study design and the small sample size limited the study’s quality, and the certainty of evidence for all outcomes was graded very low. Even if very weak, the results from this study indirectly suggest no need for anaerobic coverage in first-line treatment regimens.

Considering the high cost of the cefotaxime–vancomycin regimen, it would not be feasible to use it as a first-line antibiotic treatment for NEC in low-resource settings as previously noted in WHO recommendations for the management of common childhood conditions.27

Moreover, even though ceftriaxone/cefotaxime and oral vancomycin are included in the Access Group of 2017 WHO Essential Medicine List for Children that classifies key antibiotics that should be widely available, affordable, and quality assured, these are also included in the Watch group that includes antibiotic classes that have higher resistance potential.37 The emergence of resistance linked to the wide use of these antibiotics could affect not only LMIC but all the NICUs around the world.

In this systematic review, all the included studies were set in high-income countries with an inevitable impact on its applicability in LMIC where access to more expensive drugs, radiologic investigation or surgical procedures are limited. Interestingly, Kanto et al in 1985 found that the survival rate following surgery was similar between extreme low birth weight and low birth weight infants38; moreover, a study conducted using data on 20,822 children confirmed that surgical patients had a greater length of stay, total hospital charges, and mortality.39 Another study comparing the neurodevelopmental outcomes between the surgical NEC group with those nonsurgically managed showed that they were significantly more likely to have cerebral palsy (OR = 2.74 [1.44–5.21] p = 0.002) and psychomotor impairment (OR = 1.85 [1.07 to 3.21], p = 0.03)31 if treated surgically. Although those studies suggest that the mortality and morbidity outcomes do not appear to be better when surgical intervention is available, it should be taken into consideration that the cohort with a worse NEC stage is more likely to require surgical management. Thus, the final results might have been biased by population selection and patient treatment allocation due to the more severe condition. Therefore, finding the best empiric treatment is imperative given the risk of rapid deterioration and the poor outcomes of those complicated cases that may require surgery.

We would like to mention a randomized clinical trial of five different antibiotic regimens for infants with complicated intra-abdominal infections that has been recently completed, enrolling more than 200 patients. This study (available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01994993) has not been published yet and it could be considered an interesting attempt to improve antimicrobial strategy in NEC. However, concerning to this manuscript, its main limitation is that all five of the study arms included an antianaerobic antimicrobial (either piperacillin–tazobactam, metronidazole, or clindamycin).

Despite the lack of trials to evaluate antibiotic treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis, many studies have been conducted to find potential preventive factors in NEC development. Probiotics, prenatal glucocorticoids, breastmilk, standardized feeding protocols, and bovine lactoferrin have been shown to reduce the risk of NEC in systematic reviews.40–42 The great attention to probiotics displays their spreading use in the last decades.

Conclusion

NEC is a severe condition still with high mortality and morbidity rates. So far, no antimicrobial regimen has been shown to be superior to ampicillin and gentamicin in decreasing mortality and preventing clinical deterioration. Despite weak evidence, anaerobic coverage with preference to metronidazole could be added in patients with complicated NEC requiring surgical treatment. The current literature does not support other broad-spectrum regimens as first-line empiric therapy. Due to lack of evidence, high-drug costs and the risk of selecting multidrug resistant bacteria, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be reserved in case of first-line treatment failure, especially in VLBW neonates. As the lack of a well-defined strategy for antimicrobial treatment of NEC is still so relevant, we stress the urgency of performing adequate comparative trials to make evidence-based recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Ampicillin and gentamicin are effective in decreasing mortality and preventing clinical deterioration in NEC.

Metronidazole could be added in patients with surgical NEC.

No study with high-quality evidence was found.

Footnotes

Author’ contributions

All authors have participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting or revising of the manuscript, and they have approved the manuscript as submitted.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Battersby C, Santhalingam T, Costeloe K, Modi N. Incidence of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis in high-income countries: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(02):F182–F189. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll BJ, Kanto WP, Jr, Glass RI, Nahmias AJ, Brann AW., Jr Epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis: a case control study. J Pediatr. 1980;96(3 Pt 1):447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen RD, Lambert DK, Baer VL, Gordon PV. Necrotizing enterocolitis in term infants. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40(01):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dollberg S, Lusky A, Reichman B. Patent ductus arteriosus, indomethacin and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants: a population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40(02):184–188. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman RC, Stoll BJ, Curns AT, Yorita KL, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Necrotising enterocolitis hospitalisations among neonates in the United States. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20(06):498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawase Y, Ishii T, Arai H, Uga N. Gastrointestinal perforation in very low-birthweight infants. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(06):599–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guner YS, Friedlich P, Wee CP, Dorey F, Camerini V, Upperman JS. State-based analysis of necrotizing enterocolitis outcomes. J Surg Res. 2009;157(01):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niño DF, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. Necrotizing enterocolitis: new insights into pathogenesis and mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(10):590–600. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgibbons SC, Ching Y, Yu D, et al. Mortality of necrotizing enterocolitis expressed by birth weight categories. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(06):1072–1075.:discussion 1075-1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rees CM, Pierro A, Eaton S. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of neonates with medically and surgically treated necrotizing enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(03):F193–F198. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.099929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy K, Yanowitz TD, DiGeronimo R, et al. Short-term outcomes for preterm infants with surgical necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol. 2014;34(10):736–740. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(01):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen TN, Ritter DA, Speer ME, Kenny JD, Rudolph AJ. A randomized, controlled study of oral gentamicin in the treatment of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 1980;97(05):836–839. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schullinger JN, Mollitt DL, Vinocur CD, Santulli TV, Driscoll JM., Jr Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Survival, management, and complications: a 25-year study. Am J Dis Child. 1981;135(07):612–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu VY, Joseph R, Bajuk B, Orgill A, Astbury J. Necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birthweight infants: a four-year experience. Aust Paediatr J. 1984;20(01):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1984.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(02):133–164. doi: 10.1086/649554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faix RG, Polley TZ, Grasela TH. A randomized, controlled trial of parenteral clindamycin in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 1988;112(02):271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheifele DW, Ginter GL, Olsen E, Fussell S, Pendray M. Comparison of two antibiotic regimens for neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20(03):421–429. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah D, Sinn JK. Antibiotic regimens for the empirical treatment of newborn infants with necrotising enterocolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(08):CD007448. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007448.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Autmizguine J, Hornik CP, Benjamin DK, Jr, et al. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act—Pediatric Trials Network Administrative Core Committee. Anaerobic antimicrobial therapy after necrotizing enterocolitis in VLBW infants. Pediatrics. 2015;135(01):e117–e125. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo LJ, Li X, Yang KD, Lu JY, Li LQ. Broad-spectrum Antibiotic Plus Metronidazole May Not Prevent the Deterioration of Necrotizing Enterocolitis From Stage II to III in Full-term and Near-term Infants: A Propensity Score-matched Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(42):e1862. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Recommendations for management of common childhood conditions. Evidence for technical update of pocketbook recommendations. [Accessed April 29, 2021]. at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44774/9789241502825_eng.pdf;jsessionid=071339604CC88B87-D9E7280EAC943796?sequence=1. [PubMed]

- 28.Elgin TG, Kern SL, McElroy SJ. Development of the neonatal intestinal microbiome and its association with necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Ther. 2016;38(04):706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brower-Sinning R, Zhong D, Good M, et al. Mucosa-associated bacterial diversity in necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS One. 2014;9(09):e105046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacob S, Iacob DG, Luminos LM. Intestinal microbiota as a host defense mechanism to infectious threats. Front Microbiol. 2019;9:3328. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanner SM, Berryhill TF, Ellenburg JL, et al. Pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis: modeling the innate immune response. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(01):4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta S, Ganesh M, Ray P, Narang A. Intestinal colonization among very low birth weight infants in first week of life. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(10):807–809. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Younge NE, Newgard CB, Cotten CM, et al. Disrupted maturation of the microbiota and metabolome among extremely preterm infants with postnatal growth failure. Sci Rep. 2019;9(01):8167. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44547-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arboleya S, Martinez-Camblor P, Solís G, et al. Intestinal microbiota and weight-gain in preterm neonates. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:183. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coggins SA, Wynn JL, Weitkamp JH. Infectious causes of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42(01):133–154. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.10.012. ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bizzarro MJ, Ehrenkranz RA, Gallagher PG. Concurrent bloodstream infections in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 2014;164(01):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. [Accessed April 29, 2021];Model list of essential medicines for children. at: https://apps.who.-int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273825/EMLc-6-eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanto WP, Jr, Wilson R, Ricketts RR. Management and outcome of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1985;24(02):79–82. doi: 10.1177/000992288502400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdullah F, Zhang Y, Camp M, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in 20,822 infants: analysis of medical and surgical treatments. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010;49(02):166–171. doi: 10.1177/0009922809349161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deshpande G, Rao S, Patole S. Probiotics for prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in preterm neonates with very low birthweight: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1614–1620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60748-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.AlFaleh K, Anabrees J. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4(04):CD005496. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas JP, Raine T, Reddy S, Belteki G. Probiotics for the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(11):1729–1741. doi: 10.1111/apa.13902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.