Abstract

Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection is associated with bad obstetric history (BOH) and adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO). Here, we characterized antiviral humoral profiles, systemic and virus specific cellular immune responses concurrently in pregnant women (n = 67) with complications including BOH and associated these signatures with pregnancy outcomes. Infection status was determined using nested blood PCR, seropositivity and IgG avidity by ELISA. Systemic and HCMV specific (pp65) cellular immune responses were evaluated by flow cytometry. Seropositivity was determined for other TORCH pathogens (n = 33) on samples with recorded pregnancy outcomes. This approach was more sensitive in detecting HCMV infection. Blood PCR positive participants, irrespective of their IgG avidity status, had higher cytotoxic potential in circulating CD8+ T cells (p < 0.05) suggesting that infection associated cellular dysfunction was uncoupled with avidity maturation of anti-viral humoral responses. Also, impaired anamnestic degranulation of HCMV-pp65-specific T cells compared to HCMV blood PCR negative participants (p < 0.05) was observed. APO correlated with HCMV blood PCR positivity but not serostatus (p = 0.0039). Most HCMV IgM positive participants (5/6) were HCMV blood PCR positive with APO. None were found to be IgM positive for other TORCH pathogens. Multiple TORCH seropositivity however was significantly enriched in the APO group (p = 0.024). Generation of HCMV specific high avidity IgG antibodies had no bearing on APO (p = 0.9999). Our study highlights the utility of an integrated screening approach for antenatal HCMV infection in the context of BOH, where infection is associated with systemic and virus specific cellular immune dysfunction as well as APO.

Keywords: HCMV infection, Bad obstetric history, PCR, IgG avidity, Adverse pregnancy outcomes

1. Introduction

Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous pathogen and its infection in an immunocompetent individual, is controlled by humoral and cellular immune responses [1,2]. During primary infection, the virus undergoes latency and escapes immune clearance, persisting life-long and reactivating in immunocompromised states [3,4]. Pregnancy represents a state with an altered immuno-modulatory environment, known to facilitate HCMV infection/reactivation, which in turn puts pregnant women and new-borns at high risk of viral pathology [5].

The term Bad Obstetric History (BOH) implies history of two or more consecutive spontaneous abortions, intrauterine fetal death (IUFD), still birth, early neonatal death, fetal growth restriction and congenital anomalies. Maternal infections, including HCMV - the largest contributor to congenital infections worldwide [6,7], play a critical role in these adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) [8,9]. HCMV infection in pregnancy either primary or recurrent, can be transmitted to the developing fetus or new born, causing spectrum of serious complications and sequelae such as malformation, fetal growth restriction and death, low birth weight, ventriculomegaly, cognitive impairment, and sensorineural hearing loss. These have been associated with HCMV infection status during various stages of pregnancy [10–12].

During an active HCMV infection the virus is continuously shed and can be detected through Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in body fluids [13]. Earlier studies, have demonstrated the utility and sensitivity of blood PCR in detecting HCMV infection [14–16]. HCMV infection status can also be determined by analysing HCMV specific IgM, IgG and IgG avidity through Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) [17–19].

With high HCMV seroprevalence in women of reproductive age i.e. 80-90%, India still bears the highest burden of congenital HCMV birth prevalence which is >1.5% [20–22]. Recent studies have demonstrated higher HCMV seroprevalence in pregnant women with BOH compared to those women who had a normal previous pregnancy [15,23]. Thus, determining the virus specific immune correlates of pathogenesis and congenital transmission remain important research goals relevant to maternal and child health. Our study was aimed at characterizing HCMV infection status, antiviral humoral profiles together with systemic and HCMV specific cellular immune responses in pregnant women i.e. multigravida with BOH as well as primigravida with pregnancy complications (PC). Additionally, we explored the association of these profiles with pregnancy outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study subjects

In this cross-sectional study, 67 pregnant women, irrespective of trimester, in the age group of 18–45 years with pregnancy complications (Markers of Ultrasound such as hyper echogenic bowel and cerebral ventriculomegaly) diagnosed at recruitment including BOH were recruited from Nowrosjee Wadia Maternity Hospital, Mumbai in year 2016–2019. Pregnant women with gestational diabetes, autoimmune disorders, HIV, Hepatitis B, RTIs/STIs were excluded. The study was approved by the NWMH Ethics Committee (Ethics No. IEC-NWMH/AP/2015/005-version-02) and ICMR-NIRRCH Institutional Ethics Committee for Clinical Studies (Ethics No. D/ICEC/Sci-80/84/2015). Signed informed consent was obtained from all the subjects for their participation in the study. Trimester, age gravidity and obstetric history of the participants were noted.

2.2. Serology and PCR

Peripheral blood and stool samples were collected and screened for HCMV as mentioned previously [16,24,25]. Briefly, DNA extracted from blood and stool sample was subjected to HCMV specific nested PCR, to amplify morphological transforming region II (mtrII); plasma was subjected for detection of IgM and IgG antibodies against HCMV, Toxoplasma, Rubella and HSV-1 (TORCH) & 2, using RD-Ratio Diagnostics Elisa test system (purified and inactivated antigen) as per manufacturer instructions. HCMV IgG avidity was determined concurrently using 6 M urea as denaturing agent. The IgG avidity index (AI) was calculated as described previously [26–28] and the AI results were interpreted as follows: AI<40% = low avidity; AI 40–60% = intermediate avidity; AI>60% = high avidity [26–28]. HCMV infection status was interpreted as follows:

-

(A)

IgM negative, IgG positive with high HCMV IgG avidity: past primary HCMV infection

-

(B)

IgM negative, IgG positive with low/intermediate HCMV IgG avidity: recent HCMV infection

-

(C)

IgM positive, IgG positive with high HCMV IgG avidity: recurrent HCMV infection and

-

(D)

IgM positive, IgG positive with low/intermediate HCMV IgG avidity: primary HCMV infection [17–19].

2.3. Ex-vivo evaluation of systemic cellular immune response

Ex vivo evaluation of the frequency of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Treg cells, NKT like cells and NK cells was carried out by surface staining on whole blood collected in EDTA vacutainer with four combinations of the following fluorescently labelled monoclonal antibodies, anti-CD3 PE (Clone: SK7), anti-CD4 FITC (Clone: RPA-T4), anti CD8 AF488 (clone: SK1), anti-CD25 PECy7 (Clone: M-A251), anti-CD127 AF647 (Clone: HIL-7R-M21), anti-CD16 PE (Clone: 3G8), anti-Granzyme-B AF647 (Clone: GB11) antibodies; purchased from either BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) or Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA) as described previously [29,30].. Acquisition and analysis were performed on at least 50, 000 acquired lymphocytes on a BD ACCURI C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data Analysis was performed using FlowJo version 10.6.2 (BD Biosciences).

2.4. Ex-vivo PBMC stimulation and intracellular cytokine staining

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) and treated with DNase I (1 mg/ml) for 1 h to prevent cell clumping at 37 °C at 5% CO2. Following treatment, PBMCs were washed in complete media and stimulated in IL-2 (5U) containing complete medium with a pool of 138 peptides (15mers with 11 aa overlap) through 65 kDa phosphoprotein (pp65) of HCMV (strain AD169) obtained by JPT Peptide Technologies, Germany. The peptide was used at final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Stimulation was set, samples were processed, acquired and data was analysed as described previously [31].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). The data are presented as scatter plots, with bars indicating median values and groups were compared using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test, p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participant obstetric history

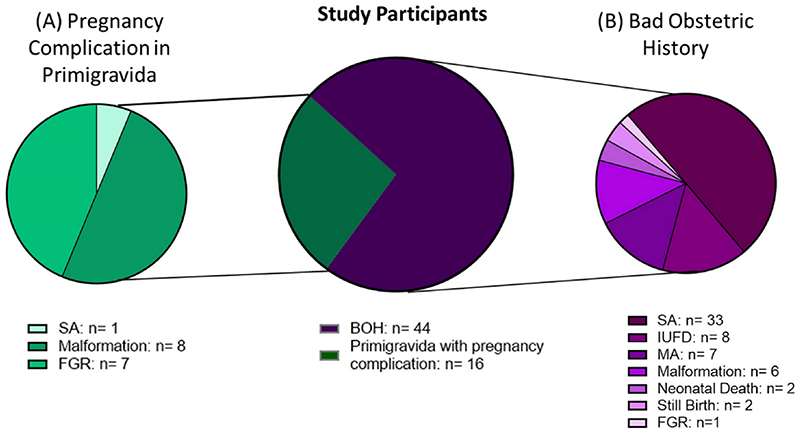

Among the 67 participants enrolled, 51 were multigravida with BOH, while 16 were primigravida with PC (Fig. 1). Complications observed in these 16 participants consisted of spontaneous abortion (SA) in 1, fetal growth restriction (FGR) in 7 and malformation in 8 (Fig. 1A). Obstetric history of 51 BOH cases consisted mainly of SA in 33 participants, intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) in 8, missed abortion (MA) in 7, malformation in 6, neonatal death in 2, still birth in 2 and FGR in 1 participant (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Obstetric history of pregnant women with (A) pregnancy complications in primigravida (PC) and (B) Bad Obstetric History (BOH). N = Number of participants in which the complication was seen. SA: spontaneous abortion; IUFD: intrauterine fetal death; MA: missed abortion; FGR: fetal growth restriction.

3.2. HCMV infection/exposure in pregnant women with BOH and PC

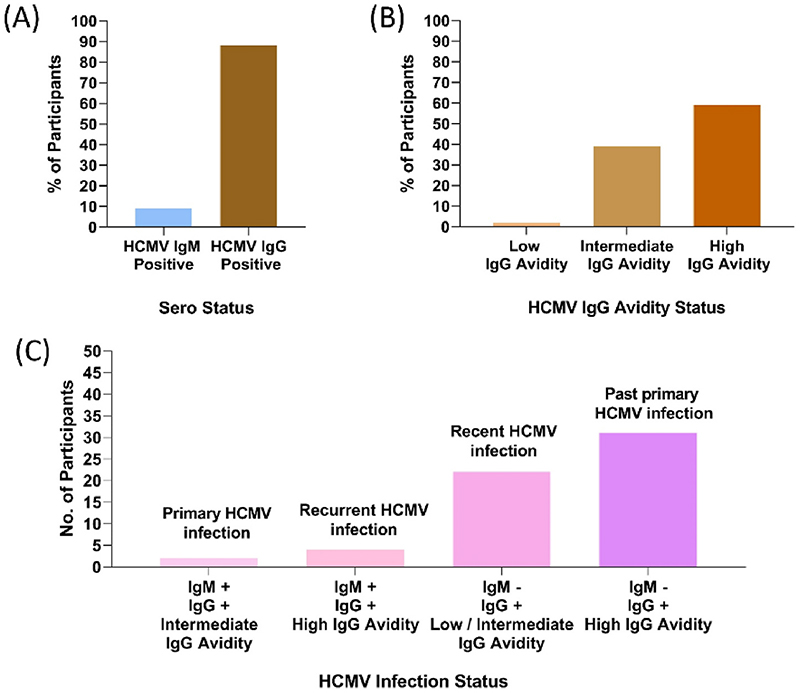

HCMV infection/exposure was determined by nested blood PCR, seropositivity and IgG avidity was measured concurrently. (Fig. 2, Table 1). In our cohort, 9% were HCMV IgM seropositive (6/67). A high seroprevalence of HCMV IgG of 88% (59/67) was observed (Fig. 2A). Of the 59 IgG seropositive participants, 59% had high avidity (35/59), 39% had intermediate avidity (23/59) and 2% had low avidity (1/59) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Distribution of HCMV seropositivity in pregnant women with BOH and PC.

(A) HCMV Serology status; n = 67 (B) HCMV IgG Avidity status; n = 59 (C) HCMV infection status; n = 59. +: Positive; -: Negative.

Table 1.

HCMV Parameters of pregnant women with BOH and PC. +: Positive; L: low IgG avidity; I: intermediate IgG avidity; H: high IgG avidity. Bold indicates HCMV infected participants n = 55. Distribution of HCMV IgG Avidity status within HCMV seropositive (IgG+) individuals along with their HCMV PCR status was compared by Fisher’s exact test.

| HCMV Blood PCR status |

Serology | Avidity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM + | IgG+ | L | I | H | |

| Positive 49/67 73% | 5/49 (10%) |

42/49 (86%) |

0 | 19/42 (45%) |

23/42 (55%) |

| Negative 18/67 27% |

1/18

(6%) |

17/18 (94%) |

1/17

(6%) |

4/17

(24%) |

12/17 (70%) |

| p value | 0.3816 | ||||

Further, HCMV IgG seropositivity (with avidity) and IgM data was interpreted as depicted in Fig. 2C. 91% (61/67) participants were IgM negative, 87% (53/61) were IgG positive, out of which 58% (31/53) had high avidity indicating past primary HCMV infection (exposure) and 42% (22/53) had low or intermediate avidity indicating recent HCMV infection. Of the 6 IgM positive participants, all were IgG Positive, of which 4 participants were with high avidity indicating recurrent HCMV infection; 2 participants were with intermediate avidity indicating primary HCMV infection. Thus, using this approach 28/59 i.e. 47% participants were considered to be infected with HCMV.

Using PCR, 73% (49/67) participants were HCMV blood PCR positive (PP) (Table 1). Among the HCMV blood PCR negative (PN) participants, 1 was IgM positive, 1 with low avidity and 4 with intermediate avidity. Thus, using integrated data (Ig class, avidity and PCR positivity), 82% (55/67) of participants had been infected with HCMV at some point (Table 1). Also, individuals with intermediate or low avidity were more frequent (45%) in PP group, although not significantly (P = 0.3816), compared to those in PN group (30%). HCMV stool PCR was carried out on 31 samples of which only 39% (12/31) were PCR positive, showing evidence of viral shedding. Out of these 12, 67% (8/12) participants were in PP group. Whereas, of 19 stool PCR negative participants, 89% (17/19) participants were in PP group (Table 2A).

Table 2.

Distribution of HCMV Parameters of pregnant women with BOH and PC (A) HCMV stool PCR Positive (B) Distribution across the three trimesters (C) In individuals with primigravida and multigravida. + /P: Positive; N: Negative; L: low IgG avidity; I: intermediate IgG avidity; H: high IgG avidity. * 2 HCMV blood PCR positive participants sampled during their third trimester with high HCMV IgG avidity were also HCMV stool PCR positive indicating viral shedding. Distribution of HCMV IgG Avidity status within HCMV seropositive individuals in primigravida and multigravida group was compared by Fisher’s exact test.

| HCMV Blood PCR Positive |

IgG+ | L | I | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. HCMV stool PCR | |||||

| P = 12/31 (39%) | 8/12 (67%) | 11/12 (92%) |

0 | 5/11 (45%) |

6/11 (55%) |

| N = 19/31 (61%) | 17/19 (89%) | 16/19 (84%) |

0 | 8/16 (50%) |

8/16 ‘(40%) |

| B. Trimester n = 64 | |||||

| 1 (n = 15) | 14/15 93% | 14/15 (93%) |

0 | 9/14 (64%) |

5/14 (36%) |

| 2 (n = 30) | 21/30 (70%) | 26/30 (87%) |

1/26 (4%) |

9/26 (35%) |

16/26 (61%) |

| 3 (n = 19) | 13/19 (68%) | 16/19 (84%) |

0 | 4/16 (25%) |

12/16 (75%) |

| C. Gravidity Primigravida (n = 16) | 13/16 (81%) | 13/16 (81%) |

0 | 3/13 (23%) |

10/13 (77%) |

| Multigravida (n = 51) | 36/51 (70.5%) |

46/51 (90%) |

1/46 (2%) |

21/46 (46%) |

24/46 (52%) |

| p value | 0.2026 |

3.3. HCMV infection status at various trimesters of pregnancy

Twenty-three percent (15/64) of participants were recruited during the first trimester (≥12 weeks), 47% (30/64) during the second trimester (13–24 weeks) and 30% (19/64) during the third trimester (25–40 weeks) (Table 2B). A cross-sectional analysis revealed that HCMV blood PCR positivity was highest during the first trimester (93%) and declined modestly up to 68% in the third trimester (Fig. S5). Interestingly, high levels of blood PCR positivity persisted in spite of significantly increasing HCMV IgG avidity across the three trimesters i.e. 36%, 61% and 75% in first, second and third trimester respectively (Fig. S3). The overall HCMV IgG seroprevalence remained high across the three trimesters (Fig. S5). Viral shedding (detected by HCMV stool PCR positive) was found in 2 PP participants in third trimester despite of having high IgG avidity. (Table 2B).

3.4. Influence of gravidity on HCMV parameters in women with BOH and PC

Of the 16 Primigravida participants, 81% (13/16) were either PP or HCMV IgG positive (Table 2C). Of the 51 multigravida participants, 70.5% (36/51) and 90% (46/51) were PP and HCMV IgG positive respectively. Based on HCMV IgG avidity, we observed a clearly higher frequency of individuals with low (2%; 1/46) and intermediate avidity (46%; 21/46) in the multigravida group (p = 0.0846). This was in spite of both groups having comparable burdens of HCMV blood PCR positivity as well as HCMV IgG as indicated in Table 2C. The primigravida group contains 77% (10/13) individuals with high avidity, 23% (3/13) with intermediate avidity and none with low avidity. These results indicated the possibility of distinct affinity maturation mechanisms that may exist based on history of PC.

3.5. Increased cytotoxic potential associated with HCMV blood PCR positivity

To assess the impact of blood PCR positivity on systemic cellular immune profiles, we evaluated frequencies of major T cell subsets using multiparametric immunophenotyping, cross-sectionally for 53 participants (PP = 38; PN = 15) with the majority being in the second trimester (n = 24). (Figs. S1 and S2).

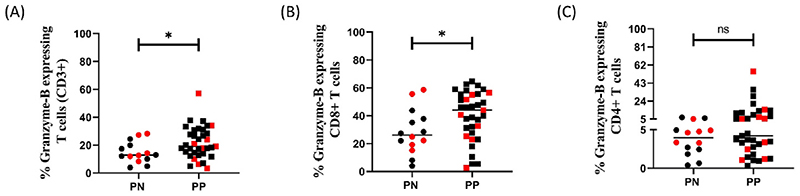

As shown in Fig. 3A, we observed a significant increase in the cytotoxic potential of total T cells i.e. frequency of Granzyme-B (GZB) expressing CD3+ T cells in PP group in spite of no apparent difference in frequency of total T cells (Fig. S6A). This increased cytotoxic potential seemed to be contributed by CD8+ T cells but not CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3B and C). This immune profile remained unchanged even when HCMV IgG negative participants were excluded (Fig. S7). Overall, the frequency of total CD4+ and CD8+ T as well as that of CD4+ T regulatory cells (CD25high CD127low) cells was not significantly different between the two groups (Figs. S6B, S6C, S6D).

Fig. 3. Cytotoxic potential in PN (n = 14) and PP (n = 35) pregnant women with BOH and PC.

(A) % Granzyme-B expressing T cells (CD3+) (B) % Granzyme-B expressing CD8+ T cells (C) % Granzyme-B expressing CD4+ T cells Data points in red indicates samples for which ICCS Assay was performed. Comparisons between groups were evaluated by non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; nsp ≥0.05). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

The aforementioned analysis was performed on individuals with high HCMV IgG avidity. Intriguingly, we observed the persistence of increased cytotoxic potential of total T cells and CD8+ T cells (Fig. S8) in spite of concomitant high avidity in these individuals. These results were suggestive of an apparent disconnect between virus specific humoral and systemic cellular immune profiles in PP participants.

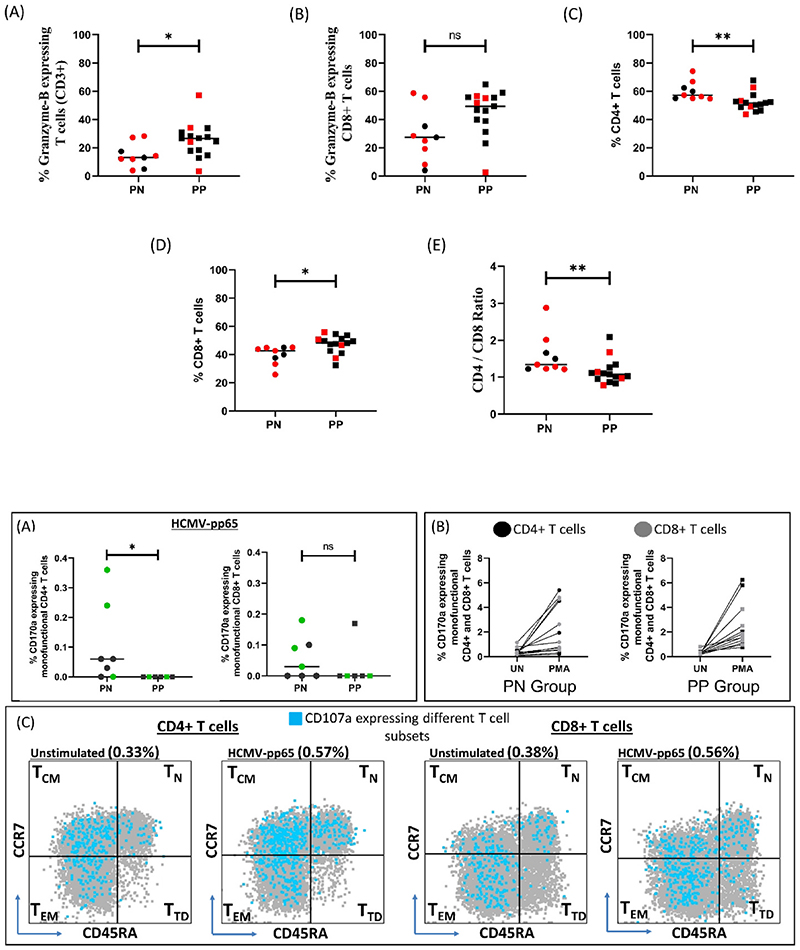

Finally, when focusing on the largest group of participants in their second trimester (PP = 15; PN = 9), we continued to observe increased cytotoxic potential in total T cells (significant) and CD8+ T cells within the PP group (Fig. 4A and B). Additionally, we delineated an altered and probably trimester specific CD4 to CD8 ratio in the PP group that was not discernible overall (Fig. 4C, D, 4E).

Fig. 4. Phenotypic and functional systemic immune response during second trimester in PN (n = 9) and PP (n = 15) pregnant women with BOH and PC.

(A) % Granzyme-B expressing T cells (CD3+) (B) % Granzyme-B expressing CD8+ T cells (C) % CD4+ T cells (D) % CD8+ T cells (E) CD4/CD8 Ratio. Data points in red indicates samples for which ICCS Assay was performed. Comparisons between groups were evaluated by non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; nsp ≥0.05). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3.6. HCMV specific T cell response in pregnant women with BOH and PC

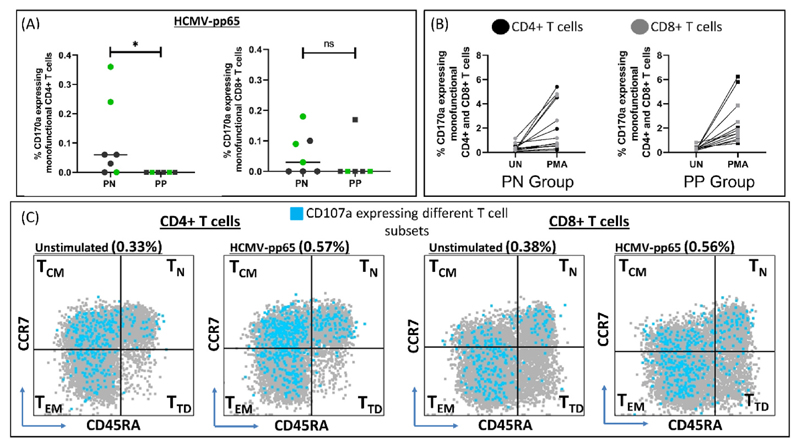

Further we sought, where possible, to delineate HCMV specific anamnestic T cell responses in the PN (n = 8) and PP (n = 7) groups. We assessed four distinct functions including cytotoxic degranulation (CD107a), Th1 cytokine production (IFN-γ and TNF-α) and chemokine production (MIP-1β) within different subsets of T cells (Fig. S9). One participant from each group was HCMV IgM positive, suggesting confounding of ‘recall’ responses due to an active infection and was excluded from the analysis (Supplementary File 2). No significant difference was observed in responder rates with respect to cytokine production although we observed some trends (Table S1). Individuals with detectable HCMV specific CD107a expressing (degranulating) monofunctional T cells (both CD4+ and CD8+) were almost exclusively observed in the PN group and not in the PP group (Fig. 5A), although all individuals retained the ability to upregulate CD107a following polyclonal stimulation by PMA (Fig. 5B, S10). In fact, responder rates for this function were significantly higher in the PN group compared to the PP group (zero responders) (Table 3). Further, within responding individuals, for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments, CD107a expression was majorly seen in non-naïve central memory (TCM; CD45RA-CCR7+) and effector memory (TEM; CD45RA-CCR7-) subsets (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. HCMV specific immune response in PN (n = 7) and PP (n = 6) pregnant women with BOH and PC.

(A) % CD107a expressing monofunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Data points in green indicates samples for which pregnancy outcome was available (B) Comparison of % CD107a expressing monofunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells between unstimulated (UN) and positive control (PMA) in PN and PP group. (C) CD107a expressing different monofunctional T cell subsets; TCM: Central Memory, TN: Naive, TEM: Effector Memory, TTD: Terminally differentiated in unstimulated and stimulated condition (pp65 peptide pool). Comparisons between groups were evaluated by non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05; nsp ≥0.05). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Table 3.

Comparison between number of responders for CD107a expression (Monofunctional) against pp65 in PN (n = 7) and PP (n = 6) Group. Comparisons between groups were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

| CD107a expression (monofunctional) against HCMV- pp65 |

HCMV Blood PCR Negative |

HCMV Blood PCR Positive |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cells | |||

| No. of Responders | 5 | 0 | 0.0210 |

| No. of Non-Responders | 2 | 6 | |

| CD8+ T cells | |||

| No. of Responders | 4 | 1 | 0.2657 |

| No. of Non-Responders | 3 | 5 |

3.7. Pregnancy outcomes

Of the 67 participants, pregnancy outcomes were available for 33 participants (Table 4), of which 73% (24/33) and 27% (9/33) were found to be in the PP group and PN group respectively (Fig. S11). Importantly, adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) were documented only in PP individuals (58.3%; 14/24; p = 0.0039) with similar distribution of BOH and PC (primigravida) i.e. 71% (10/14) and 29% (4/14) respectively compared to participants with normal pregnancy outcome (NPO), n = 19 (Table 4 and Fig. S11). In these 14 participants with APO, HCMV infection by blood PCR was detected in 50% (7/14), 29% (4/14) and 21% (3/14) during second, third and first trimester respectively (Table 5). Among these 14 individuals, 29% (4/14) showed SA and 71% (10/14) delivered neonates with low birth weight (<2.5 Kg). Interestingly, of 6 HCMV IgM positive participants in the pregnancy outcome group (n = 33), 5 were HCMV blood PCR positive and had APO (Table 4 and Fig. S12C; p = 0.0616).

Table 4.

Parameters of pregnant women with BOH and PC. L: low IgG avidity; I: intermediate IgG avidity; H: high IgG avidity. T: Toxoplasma, R: Rubella, C: HCMV, H: HSV 1 & 2. Comparisons between groups were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

| Pregnancy Outcome (n = 33) | HCMV Blood PCR Positive |

HCMV Blood PCR Negative |

HCMV IgG Negative |

L/I | H | HCMV IgM Positive |

HCMV IgM Negative |

TRCH IgG Positive |

TRCH IgG Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Pregnancy outcome (n = 14) | 14/14 | 0/14 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 10 |

| Normal outcome (n = 19) | 10/19 | 9/19 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 19 |

| p value | 0.0039 | >0.9999 | 0.0616 | 0.0245 |

Table 5.

HCMV parameters in pregnant women with BOH and PC exhibiting adverse pregnancy outcomes. n: number of participants; T = trimester; G = gravidity; P = positive; N = negative; LBW: low birth weight; TORCH status = IgG positivity for T: Toxoplasma, C: HCMV, R: Rubella and H: HSV-1&2.

| Adverse pregnancy outcomes n = 14 | HCMV blood PCR |

HCMV sero status of the mother | T | G | HCMV stool PCR |

TORCH status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous abortion, n = 4 | P | Primary HCMV infection | 1 | 6 | N | TRC |

| P | Past primary HCMV infection | 2 | 1 | P | TRC | |

| P | Recurrent HCMV infection | 2 | 4 | N | TRC | |

| P | HCMV Blood PCR positive but sero negative | 3 | 2 | N | – | |

| LBW (<2.5 Kg), Ventriculomegaly, n = 1, New-born: HCMV blood PCR positive | P | Past primary HCMV infection | 2 | 1 | N | TRCH |

| n = 10 on Day2; Death after 7months | P | Past primary HCMV infection | 1 | 3 | N | TRC |

| P | Past primary HCMV infection | 3 | 2 | N | TRCH | |

| P | Past primary HCMV infection | 3 | 1 | N | TCH | |

| P | Past primary HCMV infection | 2 | 3 | N | TRCH | |

| P | Recent HCMV infection | 2 | 3 | N | TCH | |

| P | Recent HCMV infection | 1 | 3 | N | C | |

| P | Recent HCMV infection | 3 | 9 | N | TRC | |

| P | Recurrent HCMV infection | 2 | 4 | N | RCH | |

| P | Recurrent HCMV infection | 2 | 1 | N | TRCH |

To assess the role of other known maternal infections with respect to APO, IgM and IgG seroprevalence was determined for all TORCH pathogens in participants with recorded pregnancy outcomes n = 33 (Fig. S12 A, B). None of the participants were found to be IgM positive for these (Fig. S12C). Similar frequencies of single HCMV seropositivity were observed in both APO and NPO groups (Figs. S12A and 12B). However, when distribution of multiple pathogen seropositivity was compared, we noticed a significant enrichment of all TORCH positivity (30.7%) in the APO group (Table 4, p = 0.024). One neonate born to mother recruited into the PP group with past primary HCMV infection, was diagnosed with ventriculomegaly and died after 7 months (third trimester, Table 5). TORCH sero status for this new-born was available as part of clinical history and showed Rubella, HCMV and HSV-1&2 IgG Positivity. Avidity information was not available; however, this new-born was HCMV blood PCR positive on Day 2 (Table 5). Presence of high HCMV IgG avidity antibodies were detected in significant fractions (64.2%; 9/14) of PP individuals with APO but was not significantly different (p = 0.999) from pregnant women with normal outcomes (52.6%; 10/19) (Table 4).

We next extended our cellular immune analysis to a subset of the cohort with available follow-up data. Systemic cellular cytotoxic potential was not significantly different in APO (n = 8) and NPO (n = 12) groups (Fig. S13). While outcome data was only available for 3 individuals and 2 individuals in the PN and PP group respectively (Fig. 5A, coded in green) we observed intriguingly, that individuals with detectable HCMV specific degranulation responses were PCR negative and had NPO. Conversely, 2 individuals in the PP group had APO and reflected the lack of HCMV specific degranulation observed for the group overall. In summation, the data highlight HCMV blood PCR positivity and possibly lack of antiviral degranulating responses, but not sero status or viral shedding in stool as prognostic factors for APO in our cohort.

4. Discussion

In this study, using sero-status and PCR to establish HCMV exposure and/or infection within a cohort of pregnant women with BOH and PC we demonstrate an association of dysregulated cellular immunity with HCMV infection, which in turn was associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO).

HCMV infection is the most frequent cause of congenital infections globally [32]. A few studies have shown that determining IgG avidity helps in identifying HCMV infection status in pregnant women and can be used as a marker for predicting congenital HCMV infection [33–35]. However, no such data is available for India where more than 50% of women are of reproductive age [36]. In our study, an integrated approach (sero-status, avidity and blood PCR status) to detect HCMV infection in the setting of Indian women at high risk for APO, demonstrated increased sensitivity compared to any single approach including well established markers such as IgM seropositivity [23,37,38]. This study also provides heretofore unreported data on virus specific IgG avidity profiles in HCMV infected pregnant women from India. Interestingly, in primigravida participants having PC and those with BOH (multigravida) the burden of HCMV infection was similar, although distinct HCMV IgG avidity profiles were observed in a lower proportion of BOH participants exhibiting high avidity antibodies. This may be due to recurrent HCMV infection occurring in BOH participants. Further, we observed HCMV IgG avidity, cross-sectionally, in different trimesters. Our finding, that rates of blood PCR positivity, a clear indication of HCMV infection, did not appreciably decrease despite of increasing HCMV IgG avidity, led us to explore the possibility of cellular immune dysfunction that might accompany the persistent PCR positivity. We report for the first time that the PP group, irrespective of IgG sero-status showed a signature of increased cytotoxic potential, evinced through elevated GZB expression, in CD8+T cells. This was also seen in PP individuals with high HCMV IgG avidity. Additionally, PP individuals in the 2nd trimester had a significantly altered CD4/CD8 ratio compared to the PN group together with increased GZB expression in T cells. This suggested that infection associated cellular dysfunction was uncoupled with apparently intact affinity maturation in the humoral compartment in these individuals. Indeed, studies by Pera et al. [39,40], have demonstrated how even latent HCMV infection in adults can systemically alter CD57 levels in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Also, our results strengthen the case for effective antiviral cellular responses rather than humoral responses as being determinants for resolving infection [41–43]. Studies evaluating HCMV specific T cell immunity in the context of pregnancy associated infection are limited [44,45] and do not address BOH or cytotoxic virus specific T cells that would actually mediate viral clearance. In fact, to our knowledge, only a single report by Tarokhian et al., has attempted to address HCMV specific immunity in the context of BOH [46]. However, in contrast to our study, antiviral responses were evaluated in individuals with history of recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) but not in women with ongoing pregnancy. Also, virus specific responses were reported only with respect to the CD8+ T cell compartment. Furthermore, and curiously, the polyclonal response in these women to Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B (SEB) but not the HCMV specific response was reported to be impaired. In our study, albeit with fewer samples, we demonstrate a role for both CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the anti-viral response. Earlier work in adults with latent HCMV infection as well as pregnant women with primary HCMV infection, but without BOH, has also demonstrated the presence of circulating HCMV specific CD4+T cytotoxic [47] and memory cells [48,49] respectively. The latter have also been shown to correlate with protection from congenital transmission. Follow-up studies, a limitation of the current work, detailing concurrent HCMV specific humoral and cellular responses in pregnancy may shed further light on possible immunomodulatory therapies and correlates of pathogenesis.

A recent study by Faure-Bardon et al. [18], 2019 suggests that fetal HCMV infection can be severe if maternal primary infection occurs during first trimester of pregnancy. To evaluate the clinical significance of HCMV infection with observed signatures, we undertook the collection of pregnancy outcome data from PP and PN groups wherever available. In our study, women with documented APO were found to belong exclusively to the PP group and mainly, but not restricted to, the second trimester of their pregnancy. This suggests that HCMV infection occurring during pregnancy even after the first trimester might lead to APO.

Earlier reports have indicated that women with non-primary HCMV infection also carry a risk of delivering new-borns with symptomatic congenital HCMV infection [50,51]. In our study, while new-born HMCV infection status was not determined, 43% (6/14) of women with APO had non primary HCMV infection. Of the 14 women with APO, more than half (64.2%) had high HCMV IgG avidity at the time of sampling, underscoring the apparent disconnect between high HCMV IgG avidity and APO.

Our limited data on HCMV specific T cell immunity demonstrate that pregnant women who are IgM seronegative but blood PCR positive exhibit impaired degranulating cytotoxic T cell responses, which in turn, may be associated with poor pregnancy outcomes and need to be further evaluated. Significantly, studies by Proff et al. [52], and Wang et al. [53], have demonstrated direct inhibitory mechanisms of cytotoxicity involving viral products (UL36, UL37 and UL148) mediated by HCMV in preventing killing of infected cells.

5. Conclusion

In this study, using an integrated approach (PCR and serology), we demonstrate that HCMV infection is common in pregnant women with complications including BOH accompanied by dysfunctional systemic and virus specific cellular immune signatures. We also highlight the importance of maternal screening by blood PCR for HCMV infection during pregnancy to possibly mitigate adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106109.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants for their participation in this study. We gratefully acknowledge and thank all the staff of Nowrosjee Wadia Maternity Hospital for their help in enrolment of study participants. We are also grateful to India Alliance DBT Wellcome (Team Science Grant: IA/TSG/19/1/600019); Department of Biotechnology and intramural core support from ICMR-NIRRCH for funding this research study.

Abbreviations

- HCMV

Human Cytomegalovirus

- BOH

Bad Obstetric History

- IUFD

Intrauterine Fetal Death

- APO

Adverse Pregnancy Outcome

- NPO

Normal Pregnancy Outcome

- PC

Pregnancy Complication

- PP

Recurrent spontaneous abortion

- RSA

HCMV Blood PCR positive

- PN

HCMV Blood PCR Negative

- GZB

Granzyme-B

- TORCH

Toxoplasma Rubella CMV HSV 1 & 2

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Harsha Chandrashekhar Palav: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Gauri Bhonde: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Varsha Padwal: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Shilpa Velhal: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jacintha Pereira: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Amit Kumar Singh: Methodology, Formal analysis. Sayantani Ghosh: Methodology, Formal analysis. Kalyani Karandikar: Methodology. Purnima Satos-kar: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Vikrant Bhor: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Vainav Patel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author disclosure statements

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Picarda G, Benedict CA. Cytomegalovirus: shape-shifting the immune system. J Immunol. 2018;200:3881–3889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kourí V, Correa CB, Verdasquera D, Martínez PA, Alvarez A, Aleman Y, Perez L, Golpe MA, Someilán T, Chong Y, Fresno C, et al. Diagnosis and screening for cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women in Cuba as prognostic markers of congenital infection in newborns: 2007-2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1105–1110. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181eb7388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Elder E, Sinclair J. HCMV latency: what regulates the regulators? Med Microbiol Immunol. 2019;208:431–438. doi: 10.1007/s00430-019-00581-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dell’Oste V, Biolatti M, Galitska G, Griffante G, Gugliesi F, Pasquero S, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, De Andrea M. Tuning the orchestra: HCMV vs. Innate immunity. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Parker EL, Silverstein RB, Verma S, Mysorekar IU. Viral-immune cell interactions at the maternal-fetal interface in human pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.522047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schleiss MR. Cytomegalovirus in the neonate: immune correlates of infection and protection. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/501801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Aljumaili ZKM, Alsamarai AM, Najem WS. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in women with bad obstetric history in Kirkuk, Iraq. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kumari N, Morris N, Dutta R. Is screening of TORCH worthwhile in women with bad obstetric history: an observation from Eastern Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29:77–80. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i1.7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Prasoona KR, Srinadh B, Sunitha T, Sujatha M, Deepika MLN, Vijaya Lakshmi B, Ramaiah A, Jyothy A. Seroprevalence and influence of torch infections in high risk pregnant women: a large study from south India. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2015;65:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0615-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tabata T, Petitt M, Fang-Hoover J, Zydek M, Pereira L. Persistent cytomegalovirus infection in amniotic membranes of the human placenta. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:2970–2986. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Marsico C, Kimberlin DW. Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection: advances and challenges in diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13052-017-0358-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Coppola T, Mangold JF, Cantrell S, Permar SR. Impact of maternal immunity on congenital cytomegalovirus birth prevalence and infant outcomes: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;7:1–13. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7040129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xia W, Yan H, Zhang Y, Wang C, Gao W, Lv C, Wang W, Liu Z. Congenital human cytomegalovirus infection inducing sensorineural hearing loss. Front Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/lmicb.2021.649690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Enan KA, Rennert H, El-Eragi AM, El Hussein ARM, Elkhidir IM. Comparison of Real-time PCR to ELISA for the detection of human cytomegalovirus infection inrenal transplant patients in the Sudan. Virol J. 2011;8:2–5. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fatima T, Siddiqui H, Ghildiyal S, Baluni M, Singh DV, Zia A, Dhole TN. Cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women and its association with bad obstetric outcomes in Northern India. Microb Pathog. 2017;113:282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goel A, Chaudhari S, Sutar J, Bhonde G, Bhatnagar S, Patel V, Bhor V, Shah I. Detection of cytomegalovirus in liver tissue by Polymerase chain reaction in infants with neonatal cholestasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:632–636. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Buxmann H, Hamprecht K, Meyer-Wittkopf M, Friese K. Primary human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection in pregnancy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:45–52. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Faure-Bardon V, Magny JF, Parodi M, Couderc S, Garcia P, Maillotte AM, Benard M, Pinquier D, Astruc D, Patural H, Pladys P, et al. Sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus following maternal primary infections are limited to those acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1526–1532. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Razonable RR, Inoue N, Pinninti SG, Boppana SB, Lazzarotto T, Gabrielli L, Simonazzi G, Pellett PE, Schmid DS. Clinical diagnostic testing for human cytomegalovirus infections. J Infect Dis. 2021;221:S74–S85. doi: 10.1093/INFDIS/JIZ601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zuhair M, Smit GSA, Wallis G, Jabbar F, Smith C, Devleesschauwer B, Griffiths P. Estimation of the worldwide seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2019:1–6. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Boppana SB, Manicklal S, Emery VC, Gupta RK, Lazzarotto T. The “silent” global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:86–102. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00062-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ssentongo P, Hehnly C, Birungi P, Roach MA, Spady J, Fronterre C, Wang M, Murray-Kolb LE, Al-Shaar L, Chinchilli VM, Broach JR, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection burden and epidemiologic risk factors in countries with universal screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:1–17. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Goswami L, Bezborah K, Saikia L. A serological study of cytomegalovirus infection in patients presenting with bad obstetric history attending Assam Medical College and Hospital. New Indian J OBGYN. 2017;3:86–89. doi: 10.21276/obgyn.2017.3.2.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Meshram H, Velhal S, Padwal V, Sutar J, Kadam R, Pereira J, Bhonde G, Karandikar K, Bhor V, Patel V, Shetty NS, et al. Hepatic interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor a expression in infants with neonatal cholestasis and cytomegalovirus infection. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;6:367–373. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2020.102172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sowmya P, Madhavan HN, Therese KL. Evaluation of three Polymerase chain reaction tests targeting morphological transforming region II, UL-83 gene and glycoprotein O gene for the detection of Human Cytomegalovirus genome in clinical specimens of immunocompromised patients in Chennai, India. Virol J. 2006;3:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Revello MG, Gerna G. Diagnosis and management of human cytomegalovirus infection in the mother, fetus, and newborn infant. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:680–715. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.680-715.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vilibić-Čavlek T, Ljubin-Sternak S, Vojnović G, Sviben M, Mlinaric-Galinovic G. The role of IgG avidity in diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection in newborns and infants. Coll Antropol. 2012;36:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Prince HE, Lapá-Nixon M. Role of cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG avidity testing in diagnosing primary CMV infection during pregnancy. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:1377–1384. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00487-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Salwe S, Singh A, Padwal V, Velhal S, Nagar V, Patil P, Deshpande A, Patel V. Immune signatures for HIV-1 and HIV-2 induced CD4 + T cell dysregulation in an Indian cohort. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3743-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Salwe S, Padwal V, Nagar V, Patil P, Patel V. T cell functionality in HIV-1, HIV-2 and dually infected individuals: correlates of disease progression and immune restoration. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;198:233–250. doi: 10.1111/cei.13342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kumar Singh A, Padwal V, Palav H, Velhal S, Nagar V, Patil P, Patel V. Highly dampened HIV-specific cytolytic effector T cell responses define viremic non-progression. Immunobiology. 2022;227 doi: 10.1016/J.IMBIO.2022.152234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rovito R, Warnatz HJ, Kiełbasa SM, Mei H, Amstislavskiy V, Arens R, Yaspo ML, Lehrach H, Kroes ACM, Goeman JJ, Vossen ACTM, et al. Impact of congenital cytomegalovirus infection on transcriptomes from archived dried blood spots in relation to long-term clinical outcome. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Neirukh T, Qaisi A, Saleh N, Rmaileh AA, Zahriyeh EA, Qurei L, Dajani F, Nusseibeh T, Khamash H, Baraghithi S, Azzeh M. Seroprevalence of Cytomegalovirus among pregnant women and hospitalized children in Palestine. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ebina Y, Minematsu T, Sonoyama A, Morioka I, Inoue N, Tairaku S, Nagamata S, Tanimura K, Morizane M, Deguchi M, Yamada H. The IgG avidity value for the prediction of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a prospective cohort study. J Perinat Med. 2014;42:755–759. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kaneko M, Ohhashi M, Minematsu T, Muraoka J, Kusumoto K, Sameshima H. Maternal immunoglobulin G avidity as a diagnostic tool to identify pregnant women at risk of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Al Kibria GM, Swasey K, Hasan MZ, Sharmeen A, Day B. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight, overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in India. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s41256-019-0117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dar L, Pati SK, Patro ARK, Deorari AK, Rai S, Kant S, Broor S, Fowler KB, Britt WJ, Boppana SB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a highly seropositive semi-urban population in India. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27 doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181723d55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Singh G, Sidhu MK. Bad obstetric history: a prospective study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2010;66:117–120. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pera A, Campos C, Corona A, Sanchez-Correa B, Tarazona R, Larbi A, Solana R. CMV latent infection improves CD8+ T response to SEB due to expansion of polyfunctional CD57+ cells in young individuals. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0088538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pera A, Vasudev A, Tan C, Kared H, Solana R, Larbi A. CMV induces expansion of highly polyfunctional CD4 + T cell subset coexpressing CD57 and CD154. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;101:555–566. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4a0316-112r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lissauer D, Choudhary M, Pachnio A, Goodyear O, Moss PAH, Kilby MD. Cytomegalovirus sero positivity dramatically alters the maternal CD8 T cell repertoire and leads to the accumulation of highly differentiated memory cells during human pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3355–3365. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wills MR, Poole E, Lau B, Krishna B, Sinclair JH. The immunology of human cytomegalovirus latency: could latent infection be cleared by novel immunotherapeutic strategies? Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:128–138. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Galitska G, Coscia A, Forni D, Steinbrueck L, De Meo S, Biolatti M, De Andrea M, Cagliani R, Leone A, Bertino E, Schulz T, et al. Genetic variability of human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates correlates with altered expression of natural killer cell-activating ligands and IFN-γ. Front Immunol. 2021;12:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.532484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fornara C, Zavaglio F, Furione M, Sarasini A, d’Angelo P, Arossa A, Spinillo A, Lilleri D, Baldanti F. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) long-term shedding and HCMV-specific immune response in pregnant women with primary HCMV infection. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2022;2022:1–12. doi: 10.1007/S00430-022-00747-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lim EY, Jackson SE, Wills MR. The CD4+ T cell response to human cytomegalovirus in healthy and immunocompromised people. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].C. Cd, C.D.T. Cell. CD107a Expression and IFN. 2014;7:323–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Casazza JP, Betts MR, Price DA, Precopio ML, Ruff LE, Brenchley JM, Hill BJ, Roederer M, Douek DC, Koup RA. Acquisition of direct antiviral effector functions by CMV-specific CD4 + T lymphocytes withcellular maturation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2865–2877. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mele F, Fornara C, Jarrossay D, Furione M, Arossa A, Spinillo A, Lanzavecchia A, Gerna G, Sallusto F, Lilleri D. Phenotype and specificity of T cells in primary human cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy: IL-7Rpos long-term memory phenotype is associated with protection from vertical transmission. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fornara C, Cassaniti I, Zavattoni M, Furione M, Adzasehoun KMG, De Silvestri A, Comolli G, Baldanti F. Human cytomegalovirus-specific memory CD4+ T-cell response and its correlation with virus transmission to the fetus in pregnant women with primary infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1659–1665. doi: 10.1093/CID/CIX622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tanimura K, Tairaku S, Morioka I, Ozaki K, Nagamata S, Morizane M, Deguchi M, Ebina Y, Minematsu T, Yamada H. Universal screening with use of immunoglobulin G avidity for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1652–1658. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yamada H, Tanimura K, Tairaku S, Morioka I, Deguchi M, Morizane M, Nagamata S, Ozaki K, Ebina Y, Minematsu T. Clinical factor associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women with non-primary infection. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Proff J, Walterskirchen C, Brey C, Geyeregger R, Full F, Ensser A, Lehner M, Holter W. Cytomegalovirus-infected cells resist T cell mediated killing in an HLA-recognition independent manner. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang ECY, Pjechova M, Nightingale K, Vlahava VM, Patel M, Ruckova E, Forbes SK, Nobre L, Antrobus R, Roberts D, Fielding CA, et al. Suppression of costimulation by human cytomegalovirus promotes evasion of cellular immune defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:4998–5003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720950115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.