Abstract

Neuronal cell loss is a defining feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We xenografted human or mouse neurons into the brain of a mouse model of AD. Only human neurons displayed tangles, Gallyas silver staining, granulovacuolar neurodegeneration (GVD), phosphorylated tau blood biomarkers, and considerable neuronal cell loss. The long noncoding RNA MEG3 was strongly up-regulated in human neurons. This neuron-specific long noncoding RNA is also up-regulated in AD patients. MEG3 expression alone was sufficient to induce necroptosis in human neurons in vitro. Down-regulation of MEG3 and inhibition of necroptosis using pharmacological or genetic manipulation of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), RIPK3, or mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) rescued neuronal cell loss in xenografted human neurons. This model suggests potential therapeutic approaches for AD and reveals a human-specific vulnerability to AD.

Mouse models have not allowed us to address the crucial question how the defining hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)—amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, neuronal tau tangles, granulovacuolar neurodegeneration (GVD), and neuronal cell loss—relate to each other. The major problem is that tau pathology in these models can only be induced artificially, by using frontotemporal dementia causing tau mutation or by injecting tau seeds isolated from AD patient brains (1–3). Thus, the fundamental unanswered questions remain as to whether Aβ can induce tau pathology and how neurons die in AD. Unknown human-specific features that escape modeling in rodents are likely underlying this conundrum (4).

Two good models are available that replicate human features of AD: a three-dimensional cell culture based on different types of human cells (5) and xenografted human neurons in mouse brains (6). In this study, we improved the previously Nod-SCID–based xenotransplantation model (6) using the Rag2-/- (Rag2tm1.1Cgn) immunosuppressive genetic background and a single AppNL-G-F (Apptm3.1Tcs/Apptm3.1Tcs) knock-in gene to drive Aβ pathology. Human stem cell-derived neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) transplanted into control Rag2-/- mice integrated well and developed dendritic spines (fig. S1, A and B). Two months after transplantation, the xenografted neurons already displayed some characteristic mature neuronal (NEUN and MAP2) and cortical markers (CTIP2, SATB2, TBR1, and CUX2). Unlike rodent neurons, human neurons expressed equal amounts of 3R and 4R tau splice forms at 6 months after transplantation (figs. S1C and S5H). Compared to the previously used model (6), the animals showed a considerably longer life span (>18 months longer), allowing for the study of healthy human neurons during brain aging.

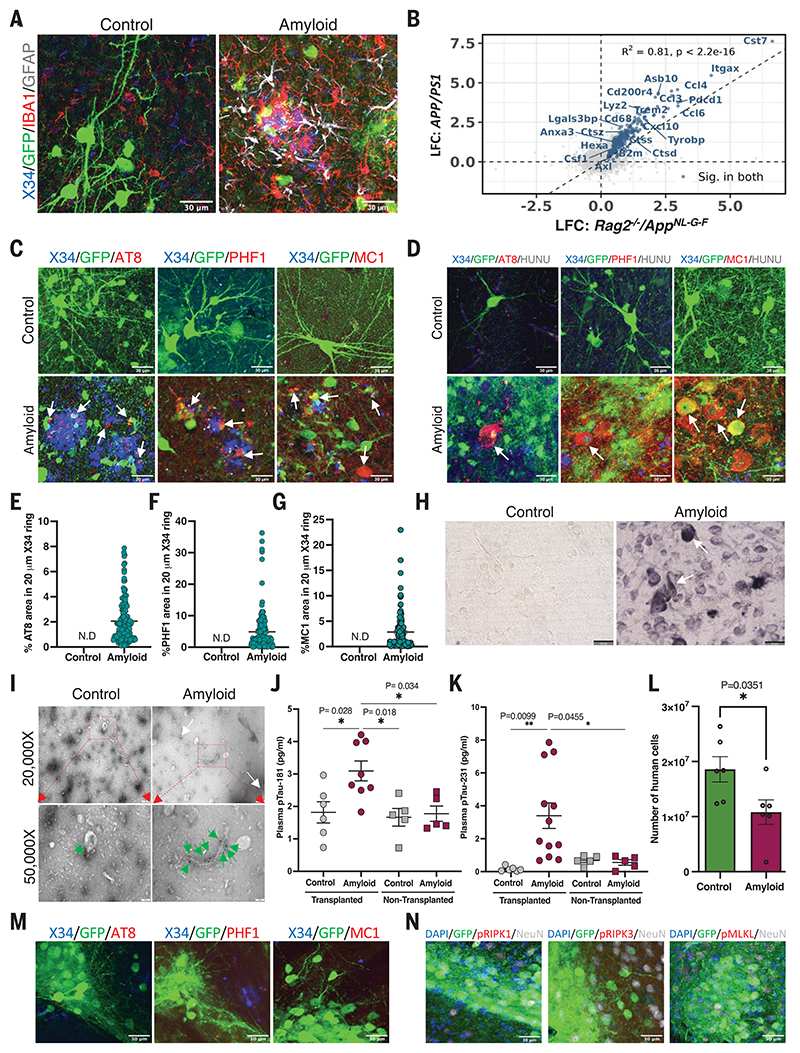

We xenografted 100,000 green fluorescent protein (GFP)–labeled H9-derived human cortical NPCs into Rag2-/-/AppNL-G-F (hereafter referred to as amyloid mice) or Rag2-/-/Appmm/mm (control mice). β sheet staining with dye X34 revealed robust plaque pathology in the amyloid mice (Fig. 1A and fig. S1, D and E). The number of cells (fig. S6H) and transcriptional profile of the human transplants at 2 months were very similar in control and amyloid mice (Fig. 2A). Thus, human neurons integrated and differentiated similarly in control and amyloid mice, in line with the fact that amyloid plaque pathology appeared only after 2 months in this model. Full-blown amyloid plaque pathology was seen at 18 months after transplantation. At this late point in time, human neurons in the control brain appeared generally healthy and displayed neuronal projections and dendritic spines intermingled with host microglial (IBA1) and astroglial (GFAP) cells (fig. S1D). In contrast, grafted neurons in the amyloid mice displayed severe dystrophic neurites associated with microgliosis (six to seven IBA1-positive microglia per Aβ plaque) and astrogliosis (two to three GFAP-positive astrocytes per plaque) (Fig. 1A and fig. S2, A and B). The glial cell recruitment to plaques was very similar to that seen in nongrafted control animals (fig. S3, A and B). Immunohistochemistry with anti–phosphorylated tau (p-tau) antibodies AT8 (p-tau Ser202 and Thr205), PHF1 (p-tau Ser396 and Ser404), and MC1 (pathological conformational tau epitope) demonstrated considerable deposition of neuritic plaque tau (NP-tau) (1) in the human neurons of the grafted amyloid mice (Fig. 1, C and D). About 2% (AT8), 5% (PHF1), and 3% (MC1) of the surface was stained with the indicated antibodies in a 20-μm ring around the Aβ plaques (Fig. 1, E to G). Both NP-tau– and AT8-positive neurons appeared as early as 6 months after transplantation (fig. S1E), indicating that amyloid deposition drives tau phosphorylation early on in this model. Notable tau pathology was not observed at 18 months in mouse neurons in the same animal nor in human grafted control or mouse neurons grafted in amyloid mice (Fig. 1, C and D, and figs. S1E, S3, C and H, and S4, A to C).

Fig. 1. Amyloid plaque deposition is sufficient to induce pathological tau in the grafts.

(A) Representative confocal images of grafted human neurons of 18-month-old control (n = 4) and amyloid (n = 4) mice. (B) Scatter plot comparing log fold changes (LFC) in APP/PS1 mice at 10 months and Rag2-/-/AppNL-G-F mice at 6 months old. Blue genes are significantly changed in both models (R2 = 0.81). (C) Representative confocal images showing NP-tau and neuronal soma tau (D) in 18-month-old control (n = 4) and amyloid (n = 4) mice. White arrows indicate X34 and NP-tau-positive cells. HUNU, human nucleus. Quantification of (E) AT8-positive tau, (F) PHF1-positive tau, (G) MC1-positive tau around Aβ plaque within 20 μm diameter in 18-month-old animals (n = 4, >100 plaques per mice). N.D, not detected. (H) Representative light microscope Gallyas silver stain images from 18-month-old control (n = 4) and amyloid (n = 4) grafted animals. (I) Electron micrograph image of immunogold-labeled sarkosyl insoluble tau fibrils isolated from 18-month-old control (n = 4) and amyloid (n = 4) mice. Tau fibrils are indicated with white (top panel) or green (bottom panel) arrows. (J) Quantification of plasma p-tau181 levels (every dot represents one mouse) and (K) p-tau231 levels from 18-month-old grafted and nongrafted mice. (L) Number of human neurons at 6 months after transplantation in control (n = 6) and amyloid (n = 6) mice using qPCR. (M) Confocal images taken from 6-month-old amyloid animals grafted with stem cell–derived mouse neurons (n = 4) did not stain with pathological tau markers (AT8, PHF1, or MC1) or (N) mouse-specific necrosome antibodies [pRIPK1(Ser166), pRIPK3 (Thr231/Thr232), or pMLKL (Ser345)]. The full panel, along with control mice, is shown in fig. S4, C and D. Scale bars: 30 μm [(A), (C), (D), (M), and (N)], 50 μm (H), 200 nm [(I), top row], 100 nm [(I), bottom row]. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was used in (J) to (K), and Student’s t test was used in (M).

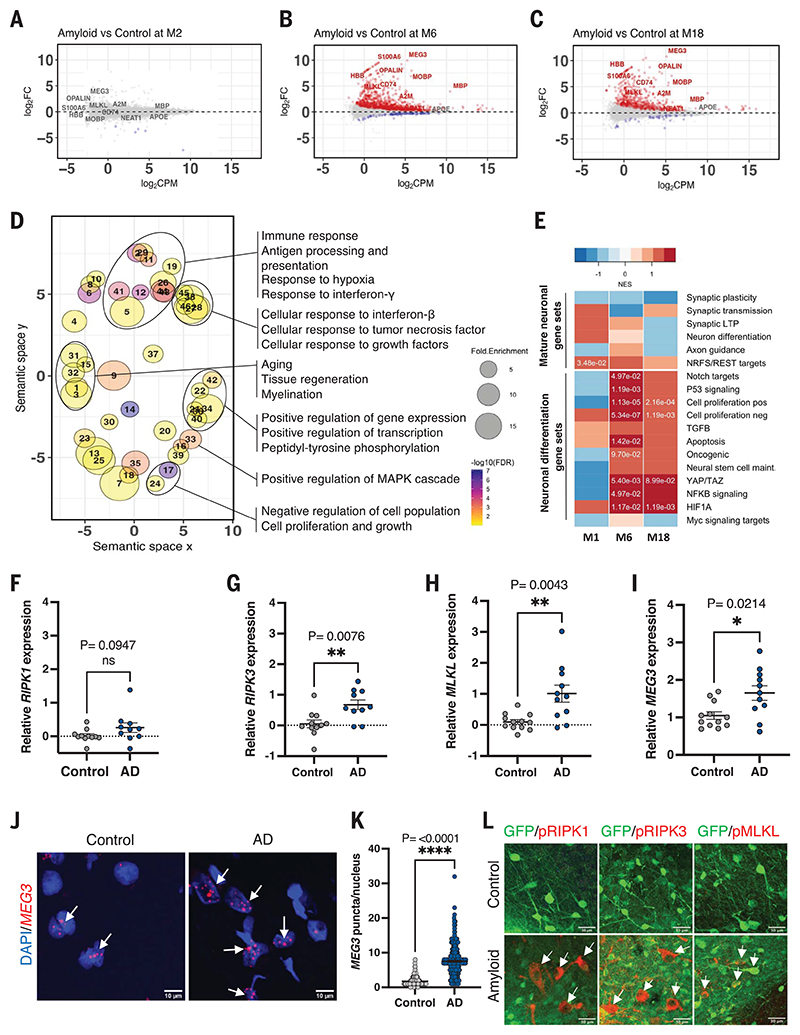

Fig. 2. Transcriptional changes in xenografted neurons.

Bland-Altman MA plot showing differential expression of genes from RNA sequencing of human grafts from control and amyloid mice at (A) 2 months (control n = 5, amyloid n = 7), (B) 6 months (control n = 5, amyloid n = 5), and (C) 18 months (control n = 4, amyloid n = 3) after transplantation. Red indicates significantly up-regulated genes. Blue indicates significantly down-regulated genes [false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05]. FC, fold change; CPM, counts per million. (D) GO analysis showing terms associated with genes up-regulated at 6 months. Point size represents the fold enrichment of up-regulated genes in the term, and color represents the -log10FDR. Only terms with FDR < 0.1 are shown. The x and y axes represent the “semantic space” (54). (E) Heatmap of normalized enrichment scores (NES) in neuronal dedifferentiation gene sets ranked along the differentially expressed genes in the xenografts (amyloid versus control) shown in (A) to (C). Positive enrichments in red, negative enrichments in blue. Significant FDR values (Padj < 0.01) are shown as numbers. (F to H) Analysis of (F) RIPK1, (G) RIPK3, and (H) MLKL mRNA expression using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) on AD (n = 11) and control (n = 10) postmortem human brain samples. (I) Analysis of MEG3 gene expression using qRT-PCR on AD (n = 11) and control (n = 10) postmortem human brain samples. (J) Confocal images showing MEG3 RNAscope in the temporal gyrus of AD (n = 3) and control (n = 2) postmortem human brain samples. Scale bars: 10 μm. (K) Number of MEG3 puncta per nucleus in control (>100 nuclei per sample, n = 2) and AD (>100 nuclei per sample, n = 3). (L) Representative confocal images showing the expression of activated necroptosis pathway markers pRIPK1, pRIPK3, or pMLKL in red (white arrows) in 18-month-old human neurons in control (n = 4) and amyloid (n = 4) mice. Scale bars: 30 μm. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test used in (F) to (I) and (K).

Pathological, β sheet X34– positive tau reactivity was seen in the xenografted human neurons (fig. S2C). Furthermore, Gallyas silver staining and tau immunogold labeling of PHF fibril-like structures extracted with sarkosyl from grafted neurons in the amyloid mice (Fig. 1, H and I) confirmed the progression of p-tau into pathological states (>20 tau fibrils per electron microscopy grid (control n = 4, amyloid n = 4) (fig. S6F). Such pathology was largely absent in grafted control or nongrafted amyloid mice (Fig. 1H and figs. S6F and S3, I and J). Finally, and of clinical relevance, we found that the increase in p-tau181 and p-tau231 (7, 8) was statistically significant in the plasma of the grafted amyloid mice but not in control grafted or nongrafted mice (Fig. 1, J and K), reflecting increased secretion of soluble p-tau biomarkers into the bloodstream in response to amyloid pathology, as in human AD.

It is possible to quantify accurately up to 0.1 ng of human DNA in a mixture with 100 ng mouse genomic DNA using quantitative PCR (qPCR) (9) (fig. S6D). Using this assay, we estimated that up to 50% fewer human neurons were present in the amyloid animals compared with controls (Fig. 1L and fig. S6G) at 6 and 18 months after transplantation. Of note, no significant increases in human neurons in the control situation were observed (fig. S6E), and the number of mouse neurons was also not significantly affected in nongrafted control or amyloid mice (fig. S3, E to G). Thus, human, but not mouse, neurons developed AD-like tau pathology upon exposure to amyloid plaques in vivo and degenerated much like their counter-parts in the human brain by an unknown death process.

Previous work has found opposite effects of Rag2-/- immunodeficiency on amyloid plaque pathology and cellular responses (10, 11). Comparison of soluble Aβ (Aβ40 and Aβ42) and guanidine-extractable Aβ (Aβ40 and Aβ42) revealed no significant differences between Rag2-/-/AppNL-G-F and AppNL-G-F mice. Bulk RNA sequencing indicated that the main aspects of the innate microglia and astroglial cellular transcriptomic responses to amyloid plaques are maintained in the Rag2-/-/AppNL-G-F immunodeficient mouse compared with a previously characterized nonimmunosuppressed amyloid mouse (APP/PS1) (12, 13) (Fig. 1B) [coefficient of determination (R2) = 0.81 for differentially expressed genes]. Thus, although we acknowledge the lack of an adaptive immune system as a weakness of the model, we note that all key features of the neuropathology of AD were reproduced.

Transcriptional changes in xenografted neurons reveal induction of necroptosis

We isolated the transplanted neuron-positive brain regions from mice at 2, 6, and 18 months after transplantation and extracted total RNA for sequencing (mean human reads: ~13.3 million) (fig. S5, A and B). Mapping to mouse and human reference databases generated speciesspecific datasets. As expected, up-regulation of the mouse genes Axl, B2m, Cst7, Ctss, Itgax, Trem2, Tyrobp, Lyz2, Ccl3, and Ccl4 confirmed microglial activation when exposed to amyloid in Rag2-/-/AppNL-G-F mice (Fig. 1B; fig. S7, A to C; and table S2) (13). Human samples clustered according to genotype and age (fig. S5C). Differential expression (DE) analysis of the human grafts at 2 months showed only a few significantly down-regulated DE genes of unknown relevance (Fig. 2A and table S1). In contrast, DE of grafts in amyloid and control conditions at 6 and 18 months revealed 916 up-regulated and 73 down-regulated genes, and 533 up-regulated and 34 down-regulated genes, respectively (Fig. 2, B and C, and table S1). Gene alterations of interest included CD74, a marker for tau tangle-containing cells (14); HBB, a cortical pyramidal neuronal marker (15–17); and A2M, which is associated with neuritic plaques in AD human brains (18) (fig. S5E). In addition to the neuronal signature, in line with previous findings (19), we also observed astroglial and oligodendrocytic genes, including MOBP, MBP, OPALIN, S100A6, and APOE, among others, indicating that the grafted neural stem cells also generated glia in vivo (fig. S5F). A limitation of the current study is the lack of an accurate estimate of the cellular composition of the graft that might influence the transcriptional profile of the grafted cells. Nevertheless, the overall expression profiles of the grafts exposed to amyloid plaques at 6 and 18 months showed strong correlations (R2 = 0.88), suggesting that the pathological cell states of neurons at 6 and 18 months are similar (fig. S5G). We found a prominent enrichment using GSEA (gene set enrichment analysis) between previously published AD datasets (table S3), including the ROSMAP (Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project) cohort (20), and our data in transplanted neurons at 6 and 18 months after transplantation [adjusted P value (Padj) < 0.05] but not at 2 months (fig. S8, A and B). Furthermore, GSEA also revealed a clear enrichment in up-regulated genes from transplanted neurons and neurons directly reprogrammed from fibroblasts of AD patients (6 months: Padj = 1.64 × 10-5; 18 months: Padj = 2.19 × 10-4). These data confirmed that our transplanted neurons capture AD-relevant transcriptional signatures (21).

Functional Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of significantly up-regulated genes (Padj < 0.05) at 6 months using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) and REVIGO (Reduce and Visualize Gene Ontology) covered semantic space around positive regulation of transcription, protein phosphorylation, positive regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade, inflammatory responses, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon signaling, cell proliferation, aging, tissue regeneration, and myelination (Fig. 2D and table S1). Some reports have suggested that neurons in AD display signatures of hypomaturity, dedifferentiation, and cell cycle reentry (22–24). Using previously published datasets (table S1) and GSEA, we found that cellular signatures of hypomaturity, dedifferentiation, P53, hypoxia-inducible factor α signaling, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling, (positive and negative) regulation of cell cycle, and cell cycle reentry were indeed enriched in the 6 and 18 month grafts but not at 2 months (Fig. 2E). Conversely, mature neuronal marker pathways, such as synaptic plasticity, synaptic transmission, long-term potentiation, and axon guidance were not significantly enriched (Fig. 2E).

How neurons die in AD remains controversial (25, 26). As shown in Fig. 1L and fig. S6G, about 50% of xenografted human neurons were lost in the amyloid mice. We did not observe any significant alterations in the expression of genes associated with cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis or ferroptosis, but found significant up-regulation of MLKL, the gene encoding the executor protein of necroptosis (Fig. 2, B and C, and figs. S2E and S6, A to C). This was not observed in the transcriptome of the host tissue (fig. S7, A to C). We used pRIPK1- (Ser166), pRIPK3- (Ser227), and pMLKL-specific (Ser358) antibodies to stain brain tissue from 18-month-old grafted and nongrafted mice. We noticed intense punctuate staining with a vesicular pattern in the soma of the neurons in grafted amyloid mice. These vesicular structures co-stained with casein kinase 1 delta (CK1δ), a marker for granulovacuolar degeneration (Fig. 2L and fig. S6I). Nongrafted control and amyloid animals or mouse neurons derived from NPCs and similarly transplanted into mice did not display these pathologies (figs. S3D and S4D).

We validated this observation by qPCR on RNA extracted from the temporal gyrus of AD and age-matched control brain samples, revealing significant up-regulation of MLKL and RIPK3 (Fig. 2, F to H). We have, on the basis of our initial observations in the xenograft model, extensively confirmed the presence of necroptosis markers in GVD in AD patients in a previous publication (27). Thus, our model has predictive value for the neuropathology of AD.

MEG3 modulates the neuronal necroptosis pathway

We identified 36 up-regulated and 21 down-regulated long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the grafts of 6-month-old animals (table S1). Some of these noncoding RNAs (e.g., NEAT1) have been implicated in AD (28), but overall, it is unclear whether or how they contribute to pathogenesis. In our data, the lncRNA MEG3 (Maternally Expressed 3) was the most strongly (~10-fold) up-regulated gene in human neurons exposed to amyloid pathology (Fig. 2, B to C, and fig. S2D) but not in the host mouse neurons (fig. S7, D to F). MEG3 has been linked to cell death pathways (29) through p53 (30), is involved in the TGFβ pathway (31), and has been associated with Huntington’s disease (32).

While MEG3 has not been implicated in AD, we found up-regulation of MEG3 in AD patient brains in a single-nucleus transcriptomic database (33). We confirmed two- to threefold up-regulation of MEG3 in RNA extracted from the temporal gyrus of AD patients (table S5) using qPCR (Fig. 2I). MEG3 in situ hybridization combined with cell-specific immunohistochemical markers NeuN (neurons), IBA1 (microglia), and GFAP (astrocytes) demonstrated its exclusive expression in the nucleus of neurons (fig. S9, A and B) and its strong enrichment in AD brains [2 to 3 puncta per nucleus in control and 8 to 10 puncta per nucleus in AD brain (P = <0.0001)] (Fig. 2, J and K). In AD, MEG3-expressing neuronal nuclei appeared blotched, with reduced 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) intensity, and MEG3-positive neurons also displayed high levels of the necroptosis marker pMLKL (fig. S9C).

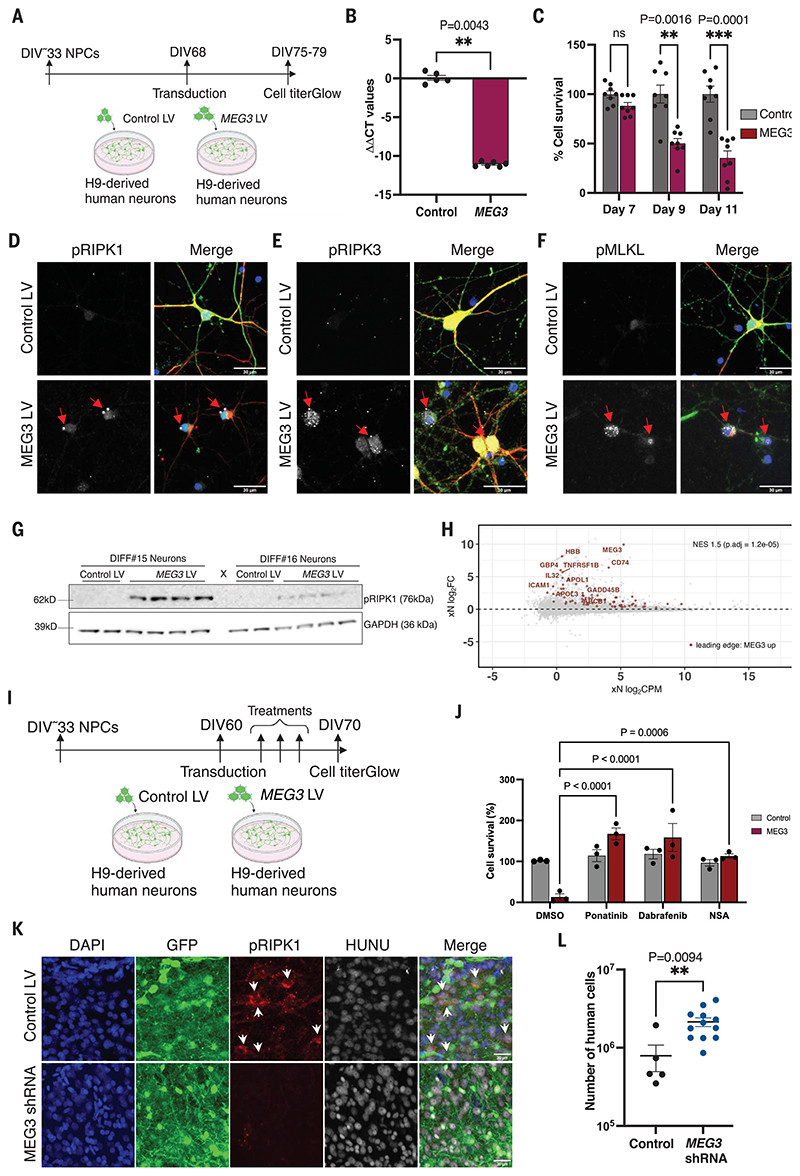

We performed Sanger sequencing on brain cDNA and found that from 15 known transcriptional variants (34), MEG3 transcript variant 1 (accession number NR_002766.2) was most abundantly expressed in human adult brain. A lentivirus was used to express MEG3 V1 in H9-derived mature cortical neurons (Fig. 3, A and B), resulting in strong reduction of cell viability at 9 days compared with control (Fig. 3C). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed the presence of activated necroptotic markers pRIPK1 (Ser166), pRIPK3 (Ser227), and pMLKL (Ser358) (Fig. 3, D to F). Necroptosis-positive neurons displayed a reduced amount of cyto-skeletal filament neurofilament-H (NF-H). Immunoblot analysis confirmed increased pRIPK1 (Ser166) levels (Fig. 3G). Notably, MEG3-induced cell loss was rescued by necroptosis inhibitors ponatinib, dabrafenib, or necrosulfonamide and by CRISPR-mediated deletion of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL in vitro (Fig. 3, I and J, and fig. S10, H to J).

Fig. 3. Long noncoding RNA MEG3 induces necroptosis in human neurons.

(A) Schematic representation of the MEG3 expression strategy using lentiviral vectors (LV) in H9-derived human neurons. (B) Analysis of the MEG3 expression 7 days after transduction with control LV (n = 5) or MEG3 LV (n = 6) in DIV75 neurons. (C) Analysis of neuronal cell survival using Cell-Titer-Glo reagent after transducing with either control LV (n = 8) or MEG3 LV (n = 8). (D) Confocal images showing pRIPK1 (Ser166), (E) pRIPK3 (Ser227), (F) pMLKL (Ser358) in neurons at DIV75 and 7 days after transduction with control LV (n = 3) or MEG3 LV (n = 3). Scale bars: 30 μm. (G) Immunoblot analysis of pRIPK1 (Ser166) levels 7 days after transduction (DIV75) with control LV (n = 4) or MEG3 LV (n = 8). Glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is the loading control. Two independent differentiations were analyzed. (H) Same Bland-Altman MA plot showing differential expression of bulk RNA sequencing of human grafts from 6 months, as in Fig. 2B. Genes highlighted in red are the leading-edge genes identified with GSEA, taking the top 400 up-regulated genes from the bulk sequencing of the primary neurons expressing MEG3 (fig. S10) and plotting them against the amyloid versus control fold changes of the human grafts (FDR < 0.05). (I) Schematic representation of the necroptosis inhibition in vitro using H9-derived human neurons (DIV60) with ponatinib (0.5 μM), dabrafenib (0.9 μM), and NSA (0.5 μM). (J) Analysis of neuronal cell survival using CellTiter-Glo reagent after necroptosis inhibitor treatment (n = 3). (K) Representative confocal images of grafted neurons showing pRIPK1 levels in samples obtained from the 6-month-old animals transplanted with control LV (n = 5) or the MEG3 shRNA (n = 5) transduced human NPCs. White arrows indicate pRIPK1-positive cells. Scale bars: 30 μm. (L) The human cell number was estimated from 6-month-old xenografted mice from control (n = 5) and MEG3 shRNA (n = 12) using qPCR. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test used in (B) and (L), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons used in (C), and two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test used in (J) to measure the statistical significance.

We performed RNA sequencing of MEG3-transduced neurons 7 days after transduction and compared the transcriptomic signatures with those from the xenografted neurons using GSEA. We ranked the genes from the amyloid and control xenografts according to their log fold change differential expression (at 6 months; see Fig. 2B) and compared those to the top up-regulated genes in response to MEG3 transduction in neurons in vitro. We found a significant enrichment of the up-regulated genes (normalized enrichment score = 1.5, Padj = 1.2 × 10-5) (Fig. 3H and table S4), suggesting that some transcriptional changes in the xenografted neurons in vivo might be the consequence of up-regulated MEG3. DE analysis of MEG3 transduced neurons revealed no changes in necroptosis genes (fig. S10, A to C). DAVID GO analysis of leading-edge genes from GSEA on up-regulated genes from 6-month transplanted human neurons and in vitro MEG3-expressing neurons revealed signatures of NF-κB and TNF signaling, which are related to necroptosis induction (35). In addition, signatures of lipid transport, interferon-γ signaling, positive regulation of peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, and apolipoprotein L signaling were observed (fig. S10D and table S4).

Inhibition of necroptosis blocks human neuronal loss in the xenografted mice

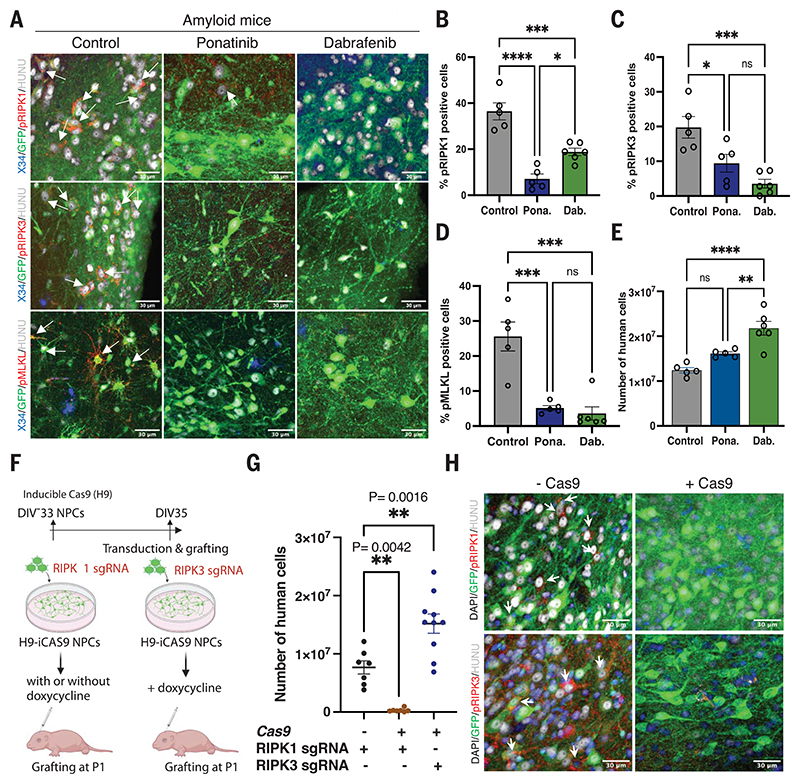

Blocking MEG3 up-regulation in NPCs using a previously characterized short hairpin RNA (shRNA) antisense construct (36, 37) significantly improved neuronal survival and was associated with down-regulated expression of necrosome proteins (Fig. 3, K and L, and fig. S10, E to G). It is possible that necroptosis markers are limited to the neurons that are remaining at the stage of pathological analysis. We thus treated xenografted mice (three groups of n = 5) from 2 until 6 months after transplantation with the orally available necroptosis kinase inhibitors ponatinib (30 mg/kg) and dabrafenib (50 mg/kg). Ponatinib inhibits RIPK1 (38) and RIPK3 (39) and is a US Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for the treatment of acute lymphoid leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia. Dabrafenib is a more specific inhibitor of RIPK3 (40). Immunostaining at 6 months revealed a large reduction in levels of pRIPK1, pRIPK3, and pMLKL in both treatment groups compared with untreated mice (Fig. 4, A to D), without alteration of the glial response to amyloid (fig. S9D). qPCR analysis of neuronal cell numbers revealed a significant increase in neurons in the dabrafenib-treated group compared with the control (Fig. 4E). Transplanting RIPK1 knockout NPCs generated using CRISPR-Cas9, as discussed earlier, demonstrated that neurons were not viable, in agreement with the lethal phenotype of RIPK1 in mouse (41). In contrast, deletion of the RIPK3 gene significantly improved neuronal survival (Fig. 4, F to H). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the significant decrease of necrosome signals in RIPK3-deficient human neurons.

Fig. 4. Inhibition of necroptosis prevents human neuronal cell loss in vivo.

(A) Confocal images showing activated necroptotic markers pRIPKl, pRIPK3, and pMLKL in amyloid animals (n = 5) and amyloid animals treated with ponatinib (n = 5) or dabrafenib (n = 6). White arrows indicate necroptosis marker-positive neurons. Scale bars: 30 μm. (B) Quantitative representation of percent of human cells immunoreactive to pRIPKl in control (n = 5) and ponatinib-treated (Pona.; n = 5) or dabrafenib-treated (Dab.; n = 6) animals. Control versus ponatinib: P ≤ 0.0001; control versus dabrafenib: P = 0.0007; ponatinib versus dabrafenib: P = 0.015. (C) Percent of human cells showing immunoreactivity to pRIPK3 in control (n = 5) and ponatinib-treated (n = 5) or dabrafenib-treated (n = 6) animals. Control versus ponatinib: P = 0.02; control versus dabrafenib: P = 0.0007; ponatinib versus dabrafenib: P = 0.2. (D) Quantitative representation of the percent of human cells showing immunoreactivity toward pMLKL in control (n = 5) and ponatinib-treated (n = 5) or dabrafenib-treated (n = 6) animals. Control versus ponatinib: P = 0.0003; control versus dabrafenib: P = 0.0001; ponatinib versus dabrafenib: P = 0.9. (E) Quantitative estimation of the number of human cells in control (n = 5) and ponatinib-treated (n = 5) or dabrafenib-treated (n = 6) grafted mice at 6 months after transplantation. Control versus ponatinib: not significant; control versus dabrafenib: P = 0.0001; ponatinib versus dabrafenib: P = 0.007. (F) Schematic representation of the RIPK1 and RIPK3 KO generation and transplantation. (G) Number of neurons surviving from 6-month-old mice transplanted with RIPK1 single guide RNA (sgRNA) without doxycycline (n = 7) or RIPK1 sgRNA with doxycycline (n = 7) or RIPK3 sgRNA with doxycycline (n = 10) using qPCR. (H) Representative immunofluorescence analysis of phosphorylated necroptosis markers pRIPK1 (n = 3) pRIPK3 (n = 3) from 6-month-old mice transplanted with RIPK1 sgRNA or RIPK3 sgRNA without and with Cas9 induction, as indicated. White arrows indicate pRIPK1- or pRIPK3-positive cells. Scale bars: 30 μm. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was used in (B) to (E) and (G).

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that amyloid pathology is sufficient to induce hallmark neuropathology of AD, including neuronal tangles and secretion of p-tau181 and p-tau231 biomarkers in blood, by simply exposing human neurons to amyloid plaques. We asked the crucial question of how neurons in AD die. Reports have proposed apoptotic mechanisms, but no convincing evidence has demonstrated that this drives neuronal cell loss in AD (42). Previous publications, one instigated by the observations in the xenograft mice, have confirmed that necroptosis occurs in the AD brain (27, 43). We demonstrate here that neuronal loss can be rescued by treatment with clinically relevant necroptosis inhibitors or by ablating the RIPK3 gene in transplanted neurons (40). Thus, we suggest that neuronal death in AD is largely driven by necroptosis, linking the loss of neurons to inflammatory processes that are upstream of this well-studied death pathway (13, 44, 45). Therapies that prevent neuronal cell loss, in combination with more-mainstream Aβ- and tau-targeted interventions, might be useful additions to the current efforts to develop disease-modifying strategies for AD (46–48). Necroptosis is an active area of drug development in cancer and ALS (49–51).

Our data suggest that necroptosis is downstream of the accumulation of pathological tau and is induced by the up-regulation of the non-coding RNA MEG3, possibly via TNF inflammatory pathway signaling. It needs to be mentioned that the imprinting status of MEG3 and its expression may differ among human embryonic stem cell lines (52). lncRNAs are important regulators of gene expression and influence a variety of biological processes, including brain aging and neurodegenerative disease (53). The large number of noncoding RNAs that are differentially expressed in our AD model warrants further investigation.

It is intriguing that human transplanted neurons display an AD phenotype, whereas mouse neurons interspersed within the graft or neurons derived from mouse NPCs and transplanted in a similar way as their human counterparts do not display such a phenotype. This suggests that unknown human-specific features define the sensitivity of the neurons to amyloid pathology. We noticed that the transplanted human neurons display signatures of down-regulation of mature neuronal properties and up-regulation of immature signaling pathways, which aligns with a recent study analyzing the transcriptional profiles in neurons directly derived from fibroblasts of AD patients (induced neurons) (21). Those neurons did not, however, show tangles, amyloid, or necroptosis markers, and it was therefore not clear how those observations relate to the classical hallmarks of AD. The contribution of these immature signatures to the disease process needs further investigation, but our data indicate that necroptosis is an important contributor to cell death in AD.

Transplanted human neurons, in contrast to transplanted mouse neurons, become diseased when exposed to amyloid pathology. Understanding the molecular basis of the resilience of mouse neurons to amyloid pathology will not only help to model the disease better but might also stimulate research into pathways that protect against neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Editor’s summary.

Neurons are one of the longest-living and enduring cell types of the human body. Balusu et al. xenografted human neurons into mouse brains containing amyloid plaques (see the Perspective by Sirkis and Yokoyama). The human neurons, but not the mouse neurons, displayed severe Alzheimer’s pathology, including tangles and necroptosis. Human neurons up-regulated the neuron-specific maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) in response to amyloid plaques. Down-regulation of MEG3 protected the neurons from dying in the xenograft model of Alzheimer’s disease. Downstream of MEG3, genetic or pharmacological manipulation of signaling kinases in the necroptosis pathway also protected neurons, suggesting a potential lead toward therapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s disease. —Stella M. Hurtley

Acknowledgments

B.D.S. is the lead contact. We thank V. Hendrickx and J. Verwaeren for animal husbandry and S. Munck, N. Corthout, A. Kerstens, and A. Escamilla Yala for their assistance with imaging (LiMoNe, VIB). Confocal microscope equipment was acquired through a Hercules Type 1 AKUL/09/037 to W. Annaert. We thank P. Baatsen, EM-platform of the VIB Bioimaging Core at KU Leuven, for assistance with electron microscopy imaging. AppNL-G-F mice were kindly provided by T. Saido (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan). PHF1 and MC1 antibodies were a gift from the P. Davies lab. We thank the Netherlands Brain Bank (NBB), Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Amsterdam, for providing the brain samples.

This research was funded in whole or in part by the Swedish Research Council (2021-03244, 2018-02532), UK Research and Innovation (MR/Y014847/1), and the European Research Council (AD834682, 681712, JPND2021-00694), cOAlition S organizations.

Funding

S.B. is a Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen (FWO) senior postdoctoral scholar (12P5922N). A.M.A. receives funding from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (RTI2018-101850-A-I00 and PID2021-125443OB-100 grants), also by FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa and RYC2020-029494-I by FSE invierte en tu futuro, the Alzheimer’s Association (grant AARG-21-850389), and the Basque Government (PIBA-2020-1-0030). E.S. receives funding from Alzheimer Nederland, the Ministry of Economic Affairs by means of the PPP allowance made available by the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health (Health Holland), and EU JPND/ZonMw. J.S. is supported by research grants from Stiftelsen för Gamla tjänarinnor, Demensfonden and Stohnes stiftelse. T.K.K. is funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskäpradet, 2021-03244), the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF-21-850325), the BrightFocus Foundation (A2020812F), the International Society for Neurochemistry’s Career Development Grant, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (Alzheimerfonden, AF-930627), the Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden, FO2020-0240), the Swedish Dementia Foundation (Demensförbundet), the Swedish Parkinson Foundation (Parkinsonfonden), Gamla Tjänarinnor Foundation, the Aina (Ann) Wallströms and Mary-Ann Sjöbloms Foundation, the Agneta Prytz-Folkes and Gösta Folkes Foundation (2020-00124), the Gun and Bertil Stohnes Foundation, and the Anna Lisa and Brother Bjornsson’s Foundation. H.Z. is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2018-02532); the European Research Council (681712); Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (ALFGBG-720931); the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (201809-2016862); the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer's Association (ADSF-21-831376-C, ADSF-21-831381-C, and ADSF-21-831377-C); the Olav Thon Foundation; the Erling-Persson Family Foundation; Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (FO2019-0228); the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant 860197 (MIRIADE); European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2021-00694); and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL. D.R.T. receives funding from FWO (G0F8516N and G065721N) and Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek (SAO-FRA 2020/017). The B.D.S. laboratory is supported by European Research Council (ERC) grant CELLPHASE_AD834682 (EU), FWO, KU Leuven, VIB, Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek, Belgium (SAO), the UCB grant from the Elisabeth Foundation, a Methusalem grant from KU Leuven, and the Flemish Government and Dementia Research Institute–MRC (UK). B.D.S. is the Bax-Vanluffelen Chair for Alzheimer’s Disease and is supported by the Opening the Future campaign and Mission Lucidity of KU Leuven.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization: S.B. and B.D.S. Methodology: S.B., K.H., K.C., D.T., N.T., A.Sn., L.S., I.C., A.M.A., J.S., T.K.K., H.Z., W.T.-C., D.R.T., E.S., and M.F. Investigation: S.B., K.H., K.C., D.T., A.Sn., I.C., A.A.M., A.Si., J.S., W.T.-C., E.S., L.S., J.S., T.K.K., and H.Z. Visualization: S.B., K.H., K.C., M.F., and N.T. Funding acquisition: S.B. and B.D.S. Project administration: S.B. and B.D.S. Supervision: B.D.S. Writing – original draft: S.B. and B.D.S. Writing – review & editing: S.B., K.H., K.C., A.Sn., D.T., N.T., A.Si., L.S., I.C., A.M.A., J.S., T.K.K., H.Z., W.T.-C., D.R.T., E.S., M.F., and B.D.S.

Competing interests: H.Z. has served on scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for AbbVie, Alector, Annexon, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, Cognition Therapeutics, Denali, Eisai, NervGen, Pinteon Therapeutics, Red Abbey Labs, Passage Bio, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave; has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, AlzeCure, Biogen, and Roche; and is a cofounder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. D.R.T. received speaker honoraria from Novartis Pharma Basel (Switzerland) and Biogen (USA); travel reimbursement from GE Healthcare (UK) and UCB (Belgium); and collaborated with GE Healthcare (UK), Novartis Pharma Basel (Switzerland), Probiodrug (Germany), and Janssen Pharmaceutical Company (Belgium). B.D.S. is or has been a consultant for Eli Lilly, Biogen, Janssen Pharmaceutical Company, Eisai, AbbVie, and other companies. B.D.S. is also a scientific founder of Augustine Therapeutics and a scientific founder and stockholder of Muna Therapeutics. W.-T.C. is an employee and stockholder of Muna Therapeutics.

Data and materials availability

RNA sequencing data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE195458). AppNL-G-F mice are available from T. Saido under a material transfer agreement (MTA) with RIKEN Institute. PHF1 and MC1 antibodies are available from the P. Davies lab under an MTA with Albert Einstein College. H9 cell lines are available under an MTA with WiCell. All materials used in the current work can be obtained upon request to B.D.S. and will be made available under the standard MTA of VIB.

References

- 1.He Z, et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:29–38. doi: 10.1038/nm.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grueninger F, et al. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattsson-Carlgren N, et al. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz2387. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guela C, et al. Nat Med. 1998;4:827–831. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi SH, et al. Nature. 2014;515:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espuny-Camacho I, et al. Neuron. 2017;93:1066–1081.:e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janelidze S, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26:379–386. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thijssen EH, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26:387–397. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensalah M, et al. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0211522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsh SE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1316–E1325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525466113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Späni C, et al. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:71. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sierksma A, et al. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e10606. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201910606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sala Frigerio C, et al. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1293–1306.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryan KJ, et al. Mol Neurodegener. 2008;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biagioli M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15454–15459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuang JY, et al. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e33120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown N, et al. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;59:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Gool D, De Strooper B, Van Leuven F, Triau E, Dom R. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90006-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W-T, et al. Cell. 2020;182:976–991.:e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostafavi S, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:811–819. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertens J, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:1533–1548.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arendt T. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:125–135. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arendt T, et al. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;920:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2661–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirths O, Zampar S. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8144. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fünfschilling U, et al. Nature. 2012;485:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koper MJ, et al. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139:463–484. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salta E, De Strooper B. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:189–200. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang N, Zhang X, Gu X, Li X, Shang L. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:30. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24731–24742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mondal T, et al. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7743. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chanda K, et al. RNA Biol. 2018;15:1348–1363. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1534524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grubman A, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:2087–2097. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48:R45–R53. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jayaraman A, Htike TT, James R, Picon C, Reynolds R. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:159. doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01264-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:3699–3706. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi H, et al. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e920793. doi: 10.12659/MSM.920793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fauster A, et al. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1767. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J-X, et al. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1278. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martens S, Hofmans S, Declercq W, Augustyns K, Vandenabeele P. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton K, et al. Nature. 2016;540:129–133. doi: 10.1038/nature20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roth KA. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:829–838. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caccamo A, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1236–1246. doi: 10.1038/nn.4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Strooper B, Karran E. Cell. 2016;164:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sierksma A, Escott-Price V, De Strooper B. Science. 2020;370:61–66. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Congdon EE, Sigurdsson EM. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:399–415. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sevigny J, et al. Nature. 2016;537:50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mintun MA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1691–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito Y, et al. Science. 2016;353:603–608. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan J, Amin P, Ofengeim D. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:19–33. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0093-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanson B. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:899–910. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1210732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rugg-Gunn PJ, Ferguson-Smith AC, Pedersen RA. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R243–R251. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lauretti E, Dabrowski K, Pratico D. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101425. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Supek F, Bosnjak M, Skunca N, Smuc T. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA sequencing data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE195458). AppNL-G-F mice are available from T. Saido under a material transfer agreement (MTA) with RIKEN Institute. PHF1 and MC1 antibodies are available from the P. Davies lab under an MTA with Albert Einstein College. H9 cell lines are available under an MTA with WiCell. All materials used in the current work can be obtained upon request to B.D.S. and will be made available under the standard MTA of VIB.