Abstract

There are numerous ways that endocytic cargo molecules may be internalized from the surface of eukaryotic cells. In addition to the classical clathrin-dependent mechanism of endocytosis, several pathways that do not use a clathrin coat are emerging. These pathways transport a diverse array of cargoes and are sometimes hijacked by bacteria and viruses to gain access to the host cell. Here, we review our current understanding of various clathrin-independent mechanisms of endocytosis and propose a classification scheme to help organize the data in this complex and evolving field.

Endocytosis is a basic cellular process that is used by cells to internalize a variety of molecules. Because these molecules can be quite diverse, understanding the different pathways that mediate their internalization and how these pathways are regulated is important to many areas of cell and developmental biology. Any endocytic pathway that mediates the transport of a specific cargo will first require mechanisms for selection at the cell surface. Next, the plasma membrane must be induced to bud and pinch off. Finally, mechanisms are required for tethering these vesicles to the next stop on their itinerary and for inducing their subsequent fusion to this target membrane.

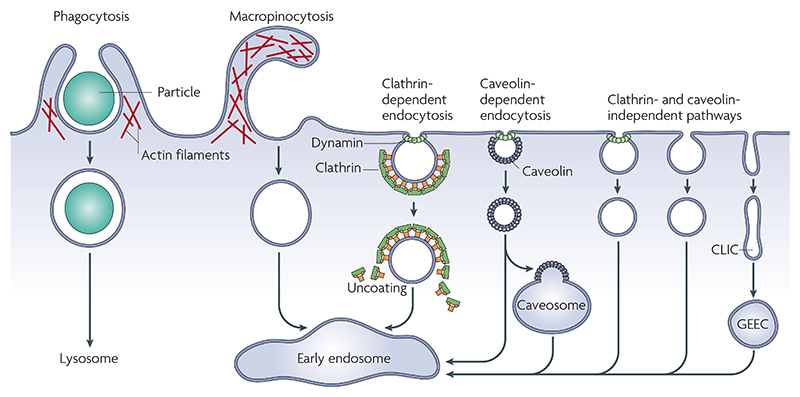

The discovery of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of specialized cargo1 and the subsequent identification of many of the players involved in this complex process (for example, adaptor complexes and Rab GTPases) has provided a fundamental paradigm for the analysis of membrane trafficking in cells (reviewed in REFS 2–4). Recently, however, several endocytic pathways that do not use clathrin have also emerged (FIG. 1; TABLE 1). Electron micrographs of some of the early intermediates in clathrin-dependent and -independent pathways are shown in FIG. 2. Some of these pathways are constitutive, whereas others are triggered by specific signals or are even hijacked by pathogens5. In addition, they differ in their mechanisms and kinetics of formation, associated molecular machinery and cargo destination.

Figure 1. Pathways of entry into cells.

Large particles can be taken up by phagocytosis, whereas fluid uptake occurs by macropinocytosis. Both processes appear to be triggered by and are dependent on actin-mediated remodelling of the plasma membrane at a large scale. Compared with the other endocytic pathways, the size of the vesicles formed by phagocytosis and macropinocytosis is much larger. Numerous cargoes (TABLE 1) can be endocytosed by mechanisms that are independent of the coat protein clathrin and the fission GTPase, dynamin. This Review focuses on the clathrin-independent pathways, some of which are also dynamin independent (FIGS 2,3). Most internalized cargoes are delivered to the early endosome via vesicular (clathrin- or caveolin-coated vesicles) or tubular intermediates (known as clathrin- and dynamin-independent carriers (CLICs)) that are derived from the plasma membrane. Some pathways may first traffic to intermediate compartments, such as the caveosome or glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein enriched early endosomal compartments (GEEC), en route to the early endosome.

Table 1. Mechanisms of clathrin-independent endocytosis*.

| Characteristics | Caveolar‡ | RhoA-regulated | CDC42-regulated | ARF6-regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo§ | Modified albumins | IL-2R-β | GPI-AP¶ | MHC I |

| GSL analogues | IL-2R-αβ | Fluid-phase markers | β1 integrin | |

| SV40; EV1 | γc-cytokine receptor‖ | CtxB¶ | E-cadherin | |

| Some integrins (for example, β1) | IgE receptor‖ | VacA toxin | GPI-AP | |

| CtxB¶ | Aerolysin | CPE | ||

| Ab-clustered GPI-AP# | IL-2R-α (Tac) | |||

| Structural components and machinery associated with pathway |

CAV1 | RhoA | CDC42 | ARF6 |

| PV1 | Dynamin | Flotillin-1** | Flotillin-1** | |

| Src | RAB5 | RAB11 | ||

| PKC-α | PI3K | RAB22 | ||

| Dynamin | EEA1 | PI3K | ||

| RAB5 | ||||

| Primary carriers | 50–80 nm diameter caveolin-coated vesicles and ‘grape-like’ aggregates | Uncoated vesicles | Clathrin- and dynamin-independent carriers (CLICs) | Unknown |

| Identity of earliest acceptor compartment | Caveosome or early endosome | Early endosome | GPI-AP enriched early endosomal compartments (GEECs) | Early tubular recycling compartment |

Ab, antibody; ARF6, ADP-ribosylation factor-6; CAV1, caveolin-1; CPE, carboxypeptidase E; CtxB, cholera toxin B; EEA1, early endosomal antigen-1; EV1, Echo virus; GPI-AP, glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein; GSL, glycosphingolipid; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL-2R, interleukin-2 receptor; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex I; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKC-α, protein kinase C-α; PV1, Polio virus; SV40, simian virus-40; VacA, Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin.

See Supplementary information S1 (table) for inhibitors and dominant negative proteins that are used to distinguish among the various clathrin-independent mechanisms.

The best caveolar markers vary with cell type (see text).

See text for representative references for different cargo molecules.

Although the specific requirements for endocytosis of molecules via a given pathway have not been rigorously established, available evidence suggests this classification.

Originally described as a caveolar marker, but recent data suggests uptake by the CDC42-regulated pathway31,33,104.

Crosslinking of GPI-APs shifts internalization from the CDC42-dependent pathway to the caveolar pathway37,105,106.

Currently, it is not clear if flotillin-1 is part of one or both of these pathways (see text).

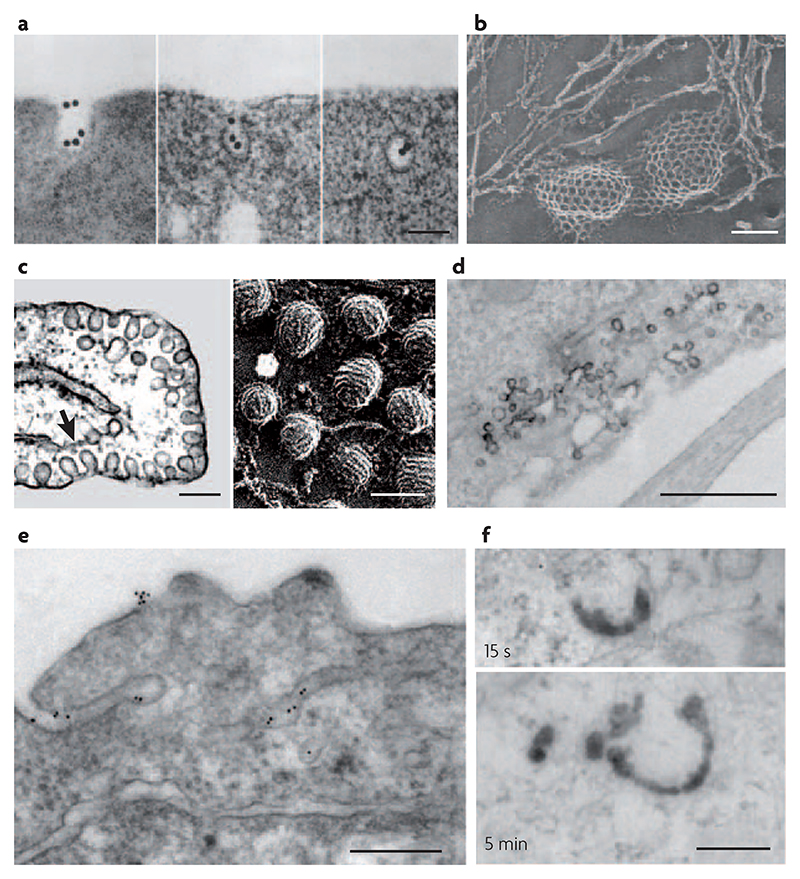

Figure 2. Electron micrographs of early intermediates in clathrin-dependent and independent pathways of endocytosis.

a|Thin-section views of reticulocytes incubated with gold-conjugated transferrin (AuTf) for 5 min at 37°C, which shows AuTf clustering into clathrin-coated pits and subsequently being endocytosed via coated vesicles. b | Rapid-freeze, deep-etch views of clathrin lattices on the inner surface of a normal chick fibroblast. c | Thin-section (left panel) and rapid-freeze, deep-etch images (right panel) of caveolae in endothelial cells. The arrow in the left panel points to the endoplasmic reticulum near deeply invaginated caveolae. d | Thin-section surface view of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated cholera toxin in the process of internalization via grape-like caveolae in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. e | Thin-section images of green fluorescent protein (GFP) with a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells and incubated with gold-conjugated antibodies against GFP. The antibodies show putative sites for clathrin- and dynamin-independent endocytosis. These represent surface-connected tubular invaginations where the gold probe is concentrated with respect to the rest of the plasma membrane. f | Thin-section micrographs of internalized HRP-conjugated cholera toxin incubated at 37°C in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, showing early intermediates in clathrin- and caveolin-independent endocytosis. Clathrin- and dynamin-independent carriers (CLICs) are observed after 15 s (top panel) and GPI-anchored protein enriched early endosomal compartments (GEECs) are observed after 5 min (bottom panel). The scale bar in a and b is 100 nm, in c is 200 nm (left panel) and 100 nm (right panel), and in d–f is 200 nm. Part a reproduced with permission from REF. 101 © (1983) Rockefeller University Press. Part b reproduced with permission from REF. 102 © (1989) Rockefeller University Press. Part c reproduced with permission from REF. 103 © (1998) Annual Reviews. Parts d and f reproduced with permission from REF. 31 © (2005) Rockefeller University Press. Part e reproduced with permission from REF. 37 © (2002) Elsevier.

Here, we discuss the characteristics of clathrin-independent (CI) endocytic pathways, the mechanisms of cargo selection and vesicle budding, the itineraries of internalized cargo, and the regulation of CI endocytosis. The CI internalization pathways of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis are not discussed, primarily because they belong to a separate class of endocytic processes that involve internalization of relatively large (>1 μm) patches of membrane6. However, these pathways may share some of the same molecular machinery, especially that related to the polymerization of actin in membrane remodelling.

Endocytosis: so many choices!

Many entry pathways into cells have been identified, which vary in the cargoes they transport and in the protein machinery that facilitates the endocytic process. The large GTPase dynamin was originally noted for its role in severing clathrin-coated vesicles from the plasma membrane and was subsequently found to be involved in a CI pathway that was mediated by caveolae (see below). Because vesicle scission at the plasma membrane is required for subsequent internalization, it was initially assumed that dynamin might have a role in all forms of endocytosis. However, it was later discovered that some CI pathways are dynamin-independent, at least when they are assessed by monitoring cargo internalization in the context of exogenous expression of mutant dynamin isoforms7 or from analysis of organisms that are homozygous for mutant dynamin8. In addition, some members of the ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) and Rho subfamilies of small GTPases have recently been suggested to have key roles in regulating different pathways of CI endocytosis9–13.

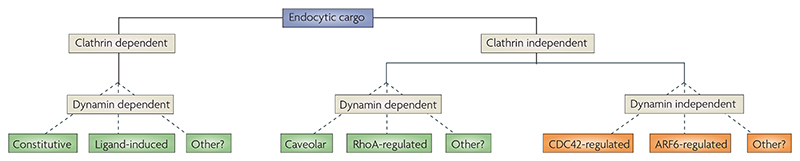

We propose a classification scheme for CI pathways, primarily for the purpose of arriving at a mechanistic understanding of the essential steps that are required to generate an endocytic vesicle in these pathways (FIG. 3). This is based on lessons that have been learned from the clathrin-mediated pathways, which show the irreducible requirements for a pinching mechanism (dynamin GTPase) and for cargo concentration (the clathrin coat and various adaptor proteins). The primary division in our classification scheme is the requirement for dynamin, thus, CI pathways are neatly divided in terms of those that use a dynamin-mediated scission mechanism (dynamin-dependent), and those that require other processes (dynamin-independent). A second feature apparent from the literature is the involvement of small GTPases in several CI pathways. We use this feature to classify the CI pathways further; the terminology CDC42-, RhoA- or ARF6-regulated endocytic pathway indicates that interfering with or modifying the function of these different GTPases affects the internalization (or trafficking) of one set of CI endocytic markers, but not another (see below and REFS 10,14,15). However, this terminology is not meant to imply that a given GTPase is directly involved only in a particular internalization mechanism — these pathways have been primarily defined by mutants of these GTPases, which are likely to affect many cellular processes16–18.

Figure 3. Proposed classification system for endocytic mechanisms.

A cargo protein can be endocytosed by either clathrin-dependent or clathrin-independent (CI) mechanisms. We propose that the CI pathways can be further categorized first by their dependence on the large GTPase dynamin, and then by other mechanistic components of the internalization pathway. This system is based on the current literature, which shows that interfering with or modifying the function of a particular GTPase affects the internalization or trafficking of one set of CI endocytic markers but not another. See TABLE 1 for endocytic markers that have been studied. The aim of this classification system for CI pathways is to categorize the molecular machinery that is associated with these pathways in the most parsimonious fashion consistent with the current literature. It is not meant to imply that a given GTPase is directly involved in regulating a particular internalization pathway because many other important cellular functions may also be regulated by that GTPase. There may be other, as-yet-unidentified CI pathways.

By dividing the CI pathways into the potential sub-classes outlined above, we aim to categorize the molecular machinery associated with these pathways in a straight-forward manner that is also consistent with the existing literature; however, alternative classification schemes have also been proposed (BOX 1). Although no system is likely to be completely satisfactory at this time, we believe that the scheme shown in FIG. 3 is helpful in providing a framework to organize and discuss the current literature in this rapidly growing field and to fuel systematic experimentation. A major task ahead is to identify the molecules that regulate particular CI endocytic mechanisms and to learn whether additional CI pathways exist.

Box 1. Classification criteria for endocytic mechanisms.

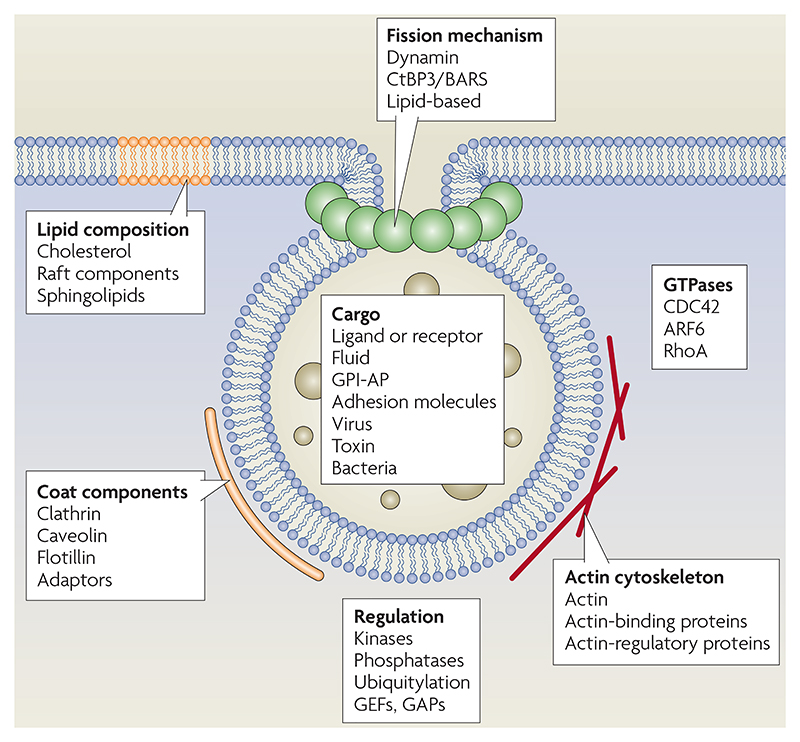

Many different factors affect clathrin-independent (CI) endocytosis (see figure) and could potentially be used to enumerate and classify these uptake mechanisms.

Alternatives to the endocytic mechanism classification system that is used in this Review (FIG. 3) might include cholesterol dependence, actin sensitivity or association with lipid rafts (which are often synonymous with detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs); see the list below). Another scheme is based on the pathways that different viruses can use when they enter cells.

Cholesterol dependence. Most endocytic pathways are sensitive to cholesterol perturbation, and clathrin-dependent92,93 and CI pathways29,48,49 are inhibited by the removal of cholesterol.

Lipid rafts. DRM-associated proteins can be accommodated in almost all endocytic pathways42.

Actin sensitivity. Many clathrin-dependent and -independent endocytic pathways show a differential sensitivity towards actin perturbation, depending on the cell type29,94.

Viral entry. This system reflects the range of endocytic machinery that may be recruited for the endocytic uptake of different viruses5. However, it is not clear how much of the mechanism that is associated with viral entry is assembled by induction through the interaction of virus and the cell-membrane receptors. In addition, there are little data that compare virus uptake with the uptake of the many endocytic markers that have been used to analyse CI endocytosis, which makes it difficult to use this system as a tool to organize and discuss the literature on CI pathways.

ARF6, ADP-ribosylation factor-6; CtBP3/BARS, C-terminal binding protein 3/brefeldin A-ribosylated substrate; GAPs, GTPase-activating proteins; GEFs, guanine nucleotide exchange factors; GPI-AP, glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein.

Dynamin-dependent CI pathways

Caveolae-mediated endocytosis is perhaps the best-characterized dynamin-dependent CI pathway. Caveolae are 50–80 nm flask-shaped plasma membrane invaginations that are marked by the presence of a member of the caveolin (Cav) protein family and are present in many cell types19–21. Biochemical and proteomic analyses of caveolar membrane fractions have shown that they are enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol22, signalling proteins and clustered glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-APs)23–25. Indeed, caveolar cargoes are diverse, ranging from lipids, proteins and lipid-anchored proteins to pathogens (TABLE 1). However, the study of caveolar endocytosis is complicated by the possibility that the same endocytic cargo may be internalized by different mechanisms in different cell types or may switch pathways in a single cell type under different conditions. For example, albumin is internalized by caveolae in some cell types (human skin fibroblasts and endothelial cells)26–28, whereas in Chinese hamster ovary cells it is internalized by a RhoA-dependent mechanism29 (see below and REFS 28,30–34 for other examples). This suggests the presence of redundant CI endocytic mechanisms that can be used by some cargo molecules.

A second, dynamin-dependent CI mechanism is a pathway that is dependent on the small GTPase RhoA35. This pathway was uncovered while studying the pathway that is responsible for internalizing the β-chain of the interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R-β), although it is also used to internalize other proteins in both immune cells and fibroblasts (TABLE 1). Following ligand binding, IL-2R-β partitions into detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs; BOX 2), a characteristic of membranes that is usually associated with CI endocytic processes. Neither dominant negative (DN) inhibitors of clathrin polymerization, nor epidermal growth factor pathway substrate-15 (EPS15; a protein involved in clathrin assembly), nor adaptor protein-180 (AP180, which is required for adaptor recruitment) affected endocytosis of IL-2R-β. However, uptake was strongly inhibited by DN dynamin and RhoA. Whether a RhoA-mediated process is required for the correct sorting of IL-2R-β into the endocytic pathway or during the endocytic process itself is currently unknown. Because RhoA is a key player in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics, RhoA could possibly be required for recruiting the actin machinery to regulate endocytosis via this pathway.

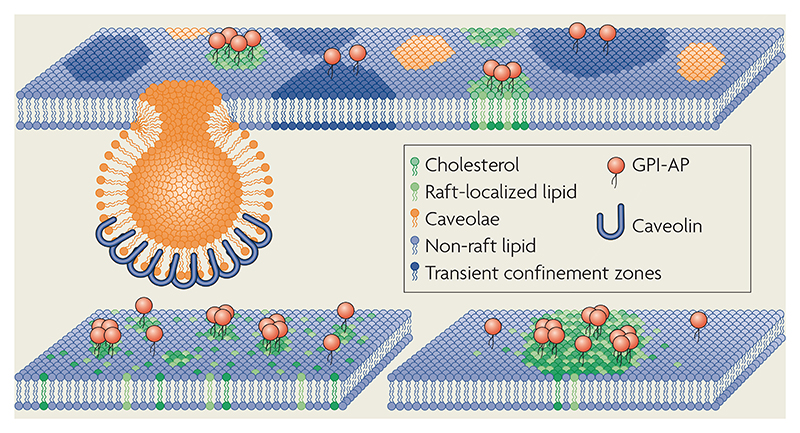

Box 2. Detergent-resistant membranes, rafts and lipid organization.

Cargo molecules that are associated with clathrin-independent (CI) endocytic pathways have often been thought to be endocytosed by lipid-raft-based mechanisms. Rafts have been proposed to be lipid-based sorting and signalling platforms that are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids22, mainly because of the observed dependence of sorting and signalling of lipid-tethered membrane components on cholesterol and sphingolipid levels in cell membranes95. Sphingolipids and phosphatidylcholine segregate into liquid-ordered (lo) and liquid-disordered (ld) phases above a certain cholesterol concentration in artificial membranes. Cholesterol-rich lo domains are relatively insoluble in cold non-ionic detergents96, whereas extraction of cell membranes by cold non-ionic detergents gives rise to a cholesterol-rich membrane fraction that is enriched in specific membrane proteins and lipids97. These observations have converged on a popular notion that rafts in cell membranes resemble the cholesterol-based phase segregation that is observed in artificial membranes and that rafts are ‘captured’ as a detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fraction. Unfortunately, the picture is not so simple (see REF. 58). The challenge ahead is to find new ways to probe lipid-dependent assemblies in the membranes of living cells. DRM association may be one, albeit imperfect, way to probe the potential association of membrane components in such assemblies. The figure shows two models of membrane rafts. In one model (top), the plasma membrane appears as a mosaic of domains, including caveolae, nanodomains that are enriched in glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-APs), and transient confinement zones98. In a second model (bottom), pre-existing lipid assemblies are small and dynamic and coexist with lipid monomers (left); however, they can be actively induced to form large-scale stable rafts (right)58. Top panel modified with permission from REF. 98 © (2002) Elsevier. Bottom panel modified with permission from REF. 58 © (2004) Blackwell Publishing.

Dynamin-independent CI pathways

A CI and dynamin-independent endocytic pathway was initially identified in HeLa cells, in which the expression of a mutant dynamin-1 blocked receptor-mediated endocytosis but apparently increased fluid-phase uptake via a CI pathway7. Dynamin-independent fluid-phase uptake has also been observed at non-permissive temperatures in Drosophila melanogaster haemocytes carrying a temperature-sensitive mutation in the GTPase domain of the protein that is encoded by shibire, the sole dynamin gene in D. melanogaster8. A common feature of constitutive dynamin-independent, CI endocytosis appears to be the use of small GTPases, either the Rho family member CDC42 or the Arf family member ARF6 (TABLE 1).

The role of CDC42 in dynamin-independent endocytosis was first identified by studying the effects of a Rho GTPase inhibitor, Clostridium difficile toxin B (toxin B), or of a DN construct of CDC42 on the internalization of GPI-APs8,31,36,37. This dynamin-independent pathway seems to be the main route for the non-clathrin, non-caveolar uptake of cholera toxin B (CtxB) as well as for the plant protein ricin38,39 and the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA)40 (TABLE 1). These carriers also represent the main mechanism of fluid-phase internalization in many cell types31,37, and are mainly devoid of cargo from the clathrin-dependent pathway36,37,41. However, it is likely that GPI-APs may take other routes into the cell in addition to the CDC42 pathway, especially if they laterally associate with proximal transmembrane proteins that are targeted to other pathways of internalization (discussed in REF. 42). For example, the GPI-anchored cellular prion protein (PrPC) is internalized by both clathrin- and caveolae-mediated pathways43–45. This could be due to the binding of specific molecules that might target PrPC to different pathways in different cell types46.

The primary carriers that bud from the cell surface by CDC42-regulated endocytosis have long and relatively wide surface invaginations, in contrast to the small spherical carriers that are characteristic of the clathrin and caveolar pathways31,37. Therefore, a large volume of fluid phase is co-internalized in a single budding event compared with these other mechanisms of internalization. This does not imply, however, that CDC42 is only involved in regulating this type of pathway: in dendritic cells, modulation of CDC42 function affects both macro-pinocytic uptake47 and phagocytosis. A recent study suggests that cholesterol-sensitive CDC42 activation is coupled to the recruitment of an actin-polymerization machinery, thus rendering this pathway sensitive to cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane and to inhibitors of actin polymerization48.

A role for the Arf family GTPase ARF6 has been suggested in the CI and dynamin-independent endocytosis of several proteins such as class I major histocompatibility complex molecules (MHC I), β1 integrin, carboxypeptidase E (CPE), E-cadherin and GPI-APs.

However, it should be noted that a direct role for ARF6 in CI internalization has not been explicitly established. Indeed, ARF6 has a potent role in actin remodelling, stimulates the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate by activating phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-5-kinase, and has also been implicated in regulating endosome dynamics by influencing the recycling rates of various membrane components14,49. Furthermore, the effects of ARF6, at least in some instances, may be cell-type specific. For example, ectopic expression of activated ARF6 stimulated the internalization of multiple membrane cargo (including GPI-APs) in HeLa cells49, whereas perturbation of ARF6 function did not affect the endocytosis of GPI-APs in Chinese hamster ovary cells41.

As mentioned above, GPI-APs have been demonstrated to be internalized by a CDC42-dependent pathway. Thus, whether the CDC42- and ARF6-regulated pathways are related or whether they are distinct mechanisms of CI endocytosis still needs to be determined. It seems likely that these two pathways will share common features, and as the same cargoes are studied more comprehensively in many different cell types, we may find that CDC42- and ARF6-regulated mechanisms of CI endocytosis represent variations on a similar theme. Alternatively, CDC42 may have distinct roles in the formation of specific endocytic carriers, whereas ARF6 may be important for membrane trafficking and recycling.

Mechanisms of cargo selection

Little is known about how cargo is selected for the different CI endocytic pathways. In contrast to clathrin-dependent endocytosis, in which specific adaptor molecules have been identified that recruit cargo to coated pits, no such well-defined adaptors for CI endocytosis have been identified. One potential mechanism that has been considered is sorting based on the association of cargo with microdomains at the plasma membrane. However, it should be noted that the association of cargo with DRMs (BOX 2) does not assure subsequent internalization by a CI mechanism50–52. The potential mechanisms for CI cargo selection have been divided into lipid- and protein-based mechanisms, although the various options within each type of mechanism are only beginning to be determined and their relative importance is unknown.

Protein-based mechanisms

Recently, it has been suggested that ubiquitylation could have a role in determining whether a protein is internalized via a clathrin-dependent or -independent mechanism. Ubiquitylation of some receptor tyrosine kinases such as the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor is mediated by c-Cbl, an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Although EGF receptors have been found to be internalized through clathrin-mediated and CI pathways, recently it has been suggested that ubiquitylation might be used to sequester EGF receptors into CI routes, despite the fact that they also have clathrin-pit localization signals. For example, high concentrations of EGF promote ubiquitylation of EGF receptors, association with DRMs, and endocytosis by a cholesterol-sensitive CI mechanism, possibly by caveolae51.

Mechanistically, the sequestration of cargo in caveolae has also been difficult to elucidate. EGF receptors are guided into the caveolar pathway by three ubiquitin interacting motif-containing proteins: EPS15, epsin and EPS15R (EPS15-related). However, all three proteins are somewhat redundant in their function because a strong inhibitory phenotype is only observed in triple small interfering RNA (siRNA) knock-down studies51.

Protein-based mechanisms of cargo sorting have also been implicated in the RhoA- and ARF6-regulated pathways of CI endocytosis. Specific internalization sequences are thought to be present in the cytoplasmic tail of the γc-cytokine receptor, which is internalized in a RhoA-dependent manner53. Therefore, a protein-based adaptor machinery that targets molecules specifically to this pathway could exist, although these adaptors remain to be discovered. In the ARF6-regulated pathway, CPE has a cytoplasmic tail sequence that confers binding to ARF6. Deletion of this tail region results in the inhibition of endocytosis, as does expression of DN ARF654. However, many cargoes that are internalized by the ARF6-regulated pathway and other CI pathways lack any known cytoplasmic signal; thus, other unknown mechanisms must regulate cargo sequestration for CI internalization.

Lipid-based mechanisms

In the absence of any protein adaptors and without the extension of a cytoplasmic tail for membrane-anchored proteins, other mechanisms for CI cargo selection must be invoked. One such mechanism is the nanoscale clustering of lipid-tethered proteins, which is emerging as an intrinsic sorting signal for the CDC42-dependent pathway for internalization of native GPI-APs55. Artificial crosslinking of GPI-APs into larger-scale structures instead directs these proteins into caveolar or other CI pathways.

CtxB can be internalized by clathrin-, caveolar- and CDC42-dependent pathways, suggesting it is organized in the membrane in different ways. Using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay, Nichols and colleagues have shown that CtxB is not significantly clustered when it is located in clathrin-coated pits, whereas considerable clustering is observed in other parts of the membrane56. It has been shown that monosialoganglioside GM1, the receptor for CtxB, is not distributed uniformly over the plasma membrane, but is concentrated approximately four-fold in non-coated invaginations57. Considering this, it will be important to examine the nanoscale organization of CtxB as it is internalized by different CI and dynamin-independent pathways. Nanoscale domains might come together to form active endocytic domains58 that are regulated by a specific pathway, or different CI mechanisms may show a preference for different sizes of microdomains. Alternatively, if there are multiple types of microdomain (as suggested by several studies42,59), these may serve to sort membrane components associated with these domains into different endocytic pathways. The challenge is to identify how lipid-based microdomains of different types may be assembled and recognized by cytoplasmic constituents.

Combined lipid–protein mechanisms

Integral membrane proteins with unusual topology, such as caveolin, may serve to link mechanisms of cargo selection that are based on lipid organization with a specific cytoplasmic machinery for subsequent internalization. Fluorescent analogues of glycosphingolipids (GSLs; a subclass of sphingolipids) are internalized primarily by caveolae in various cell types28,60,61; however, the basis for this selective internalization is not known. A recent study by Singh et al.62 indicated that the stereochemistry of a GSL, as well as its ability to cluster in membrane microdomains, have important roles in determining the pathway of internalization. GSL analogues of different stereochemistries are internalized by different endocytic pathways and, furthermore, a non-natural GSL analogue that does not cluster in membrane microdomains is not taken up in caveolae. Thus, the proper organization of GSLs into plasma-membrane domains appears to be required for targeting to caveolae.

The integral membrane proteins flotillin-1 and flotillin-2 (also called reggie-2 and -1, respectively63) may have a role in selecting lipid cargo for dynamin-independent endocytosis. First, crosslinked or ‘activated’ GPI-APs and CtxB are found to be co-localized with flotillin-1 and -2 at the surface of cells that lack caveolin64. Second, flotillin-1 is assembled in dynamic punctate structures at the cell surface that are distinct from clathrin and caveolin sites in the membrane56, which defines a further location that could recruit or trap specific membrane components. Finally, siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous flotillin-1 in cells caused a marked decrease in dynamin-independent endocytosis of fluid-phase markers, GPI-APs and CtxB. This implicates flotillin-1 as one of the cytoplasmic components of CI endocytosis56. However, it remains to be determined whether flotillin-1 has a direct role in cargo selection and vesicle budding, or whether it is a cargo molecule that is recognized by the CI endocytic machinery.

Mechanisms for membrane budding

The generation of endocytic carriers at the cell surface involves membrane deformation, its growth into a spherical bud or tubule and, finally, membrane scission. In the clathrin-mediated pathway, many membrane-deforming proteins such as clathrin, epsin and dynamin have been reported to be involved65. However, even in this well-studied pathway, the physico-chemical mechanism of membrane deformation and pinching are poorly understood. Recently, two theoretical models have been proposed that consider the material characteristics of the membrane and the machinery that is necessary for the generation of membrane buds (BOX 3). These theoretical approaches are important because they provide new ways of thinking about the budding process, and may rationalize the classification of these endocytic pathways based on the actin regulatory GTPases.

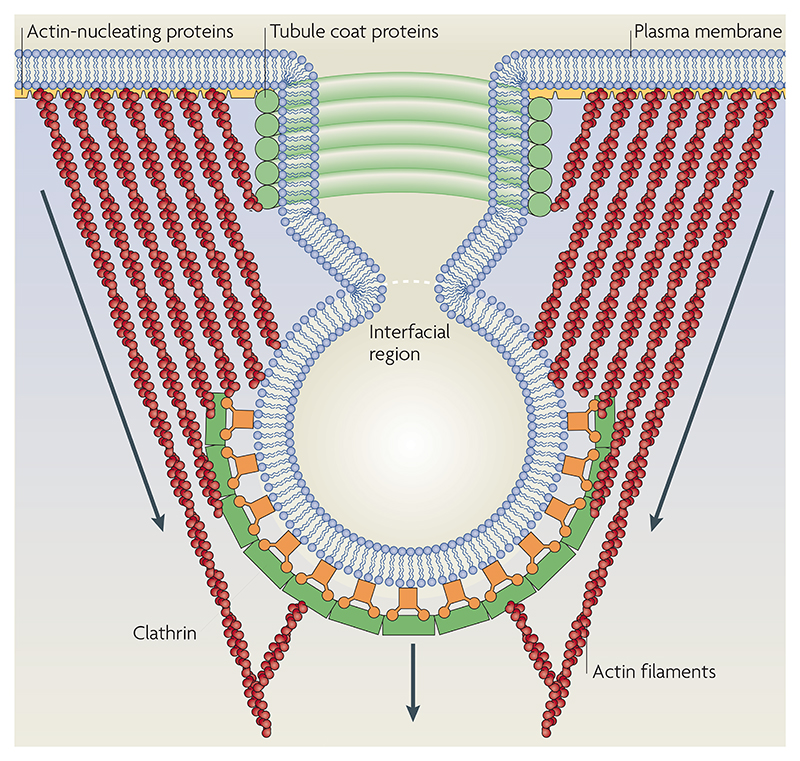

Box 3. Mechanisms of budding: recent theoretical perspectives.

The generation of endocytic carriers at the cell surface involves membrane deformation, its growth into a spherical bud or tubule and, finally, membrane scission. Recently, a general mechanism of membrane budding has been proposed in which the phase segregation of lipids could serve as a basis for initiating a membrane bud. The mechanism of generating this phase segregation might include protein-based accretion at a particular site that allows for the accumulation of specific cargo (for example, at clathrin-coated pits or at caveolae), which results in the spontaneous curvature of these membrane domains and their subsequent pinching by dynamin. However, it is unlikely that lipid-based mechanisms of cargo selection operate on similar principles, especially if they are raft-like or liquid-ordered (BOX 2). The chiral composition of rafts could spontaneously initiate buds of the appropriate morphology and dimension commensurate with those observed in clathrin-independent endocytic vesicles99. The figure shows a theoretical model for endocytosis in which actin filaments exert protrusive surface stresses on the bud and tubule100. The tubule coat proteins create a lipid-phase boundary between the bud and the tubule. The clathrin adaptor proteins (or alternative coats) may add to the bending modulus and spontaneous curvature of the bud region, and fission of membranes might be driven by a phase-separation mechanism. Figure modified with permission from REF. 100 © (2006) National Academy of Sciences.

Itineraries of CI endocytic cargo

Extensive studies that detail the itineraries of various cargo molecules have been carried out. For example, endocytosed GPI-APs can be detected in tubular invaginations that subsequently undergo fusion to generate distinct early endosomal compartments, termed GPI-AP-enriched early endosomal compartments (GEECs)31,37,41; CtxB is endocytosed via small tubular or ring-like carriers known as clathrin- and dynamin-independent carriers (CLICs) that bud directly from tubular invaginations at the plasma membrane31; and some cargo molecules of the ARF6-mediated CI pathway also localize to a distinct type of early endosome. Although not a focus of this Review, an important finding is that virtually all routes of entry eventually merge at the RAB5 and early endosomal antigen-1 (EEA1)-marked early endosome. Following internalization by distinct endocytic mechanisms and subsequent merging at the early endosome, cargo molecules are then sorted for delivery to various intracellular destinations or for recycling back to the plasma membrane. It is interesting to note that there can be differences in intracellular destinations even when two cargo molecules are internalized by the same mechanism. Various mechanisms have been suggested for sorting at the early endosome and are supported to varying degrees. These include sorting based on the unique tubulovesicular geometry of the early endosome66, selective retention67 or recycling of membrane components, lipid physical properties68,69 and the presence of a mosaic of proteins (for example, Rab GTPases) that are required for vesicle tethering and subsequent fusion steps70.

Regulation of CI endocytosis

The wide variety of cargo molecules that are able to stimulate and be internalized by CI pathways, including pathogens, lipids and growth factors, suggests that these pathways must be regulated. Indeed, various kinases and signalling molecules have been associated with membrane microdomains and caveolae, and a recent screen of the human kinome identified a total of 80 different kinases that are somehow involved in endocytosis of the caveolar cargo simian virus-40 (SV40)71. Furthermore, lipids may have a role in regulating CI pathways of endocytosis through their effects on the formation of distinct membrane domains and the clustering of proteins into these domains72. Finally, the dependence of many CI pathways on distinct small GTPases also provides a likely target for regulation.

Membrane composition and caveolar endocytosis

Pharmacological depletion or sequestration of cholesterol disrupts the integrity of caveolae and inhibits caveolar endocytosis of several cargo molecules (TABLE 1). However, other endocytic mechanisms are also cholesterol-sensitive and, depending on the cell type and the extent of depletion, might also be disrupted (Supplementary information S1 (table)). A general depletion of sphingolipids (that is, GSLs and sphingomyelin) also blocks multiple CI pathways, including caveolae-mediated endocytosis as well as the RhoA- and CDC42-regulated pathways. In contrast, depletion of GSLs alone selectively blocks caveolar endocytosis29. Furthermore, the effects of GSL depletion can be restored by incubation with exogenous GSLs, whereas disruption of RhoA- and CDC42-regulated endocytosis by sphingolipid depletion is restored by exogenous sphingomyelin (but not GSLs). These results suggest the importance of cellular sphingolipids in the regulation of different CI endocytic mechanisms.

Caveolar endocytosis is an inducible process and can be stimulated by the presence of cargo57,73–75. Indeed, acute treatment of human skin fibroblasts with non-fluorescent GSLs or elevation of cellular cholesterol levels stimulated the internalization of caveolar markers without affecting other clathrin-dependent and CI pathways61,76. One plausible model for the stimulation of caveolar endocytosis by exogenous lipids is that they alter the domain organization of the plasma membrane, thereby inducing the clustering and activation of signalling proteins at the plasma membrane that are needed to initiate caveolar uptake (for example, β1 integrins72,76). The effects of exogenous lipids on caveolar endocytosis are likely to be physiologically important. For example, gangliosides are shed from tumour cells, and thereby contribute to the tumour microenvironment53,77. Acute, local changes in cellular cholesterol might also occur as a result of many processes in vivo (for example, cell injury), which, in turn, could affect endocytosis as noted above.

Regulation of distinct pathways through GTPases

In the absence of acute stress, it seems reasonable that the surface area of the cell will be relatively constant over time. Therefore, a change in the activity of a particular endocytic mechanism might be compensated for by alterations in other mechanisms of endocytosis. One of the first important clues supporting the concept of cross-regulation came from the work of Schmid and colleagues, who showed that the inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis following the expression of a temperature-sensitive dynamin mutant resulted in an upregulation of fluid-phase endocytosis7,78. Another example of the co-regulation of different CI endocytic mechanisms comes from studies of cells that were treated with tetrafluoroaluminate (AlF4), an agent that locks G-proteins in an activated state. This caused an upregulation of ARF6-mediated endocytosis in cells that were transfected with ARF6, whereas the CDC42-regulated pathway was inhibited, which implies that there are different modes of regulation for these pathways, potentially via G-proteins41.

An important clue as to how cross-regulation between the caveolar and CDC42-dependent (or RhoA-dependent) pathways might occur comes from a recent study by Nevins and Thurmond79. They showed that CAV1 functions as a novel CDC42 guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) in pancreatic β-cells. Analysis of the CAV1 amino-acid sequence revealed a motif that is conserved in GDIs, and this finding was further supported by in vitro binding assays that showed a direct interaction between CAV1 and GDP-bound CDC42. Importantly, CAV1 depletion resulted in an induction of activated CDC42 and an increase in CDC42-dependent insulin release from these cells. So, it is possible that factors affecting CAV1 levels or that alter its intracellular distribution might also alter the activation state of CDC42 (and possibly other Rho GTPases), resulting in a compensatory change in the levels of CDC42-dependent (or RhoA-dependent) endocytosis.

Coupling of secretion and endocytosis

To maintain a constant cell surface area, the delivery of new lipids and proteins to the plasma membrane might be balanced by the internalization of components at the cell surface. In the regulated endocytosis that is observed at the synapse in nerve termini, there is compelling evidence to implicate clathrin-dependent endocytosis in maintaining membrane homeostasis80. However, there is little evidence that supports this concept in constitutive systems, except in yeast, where most secretory mutants were also found to be defective in endocytosis81. Ito and Komori demonstrated that the enzymatic cleavage of cell-surface GSLs causes a rapid upregulation of GSL synthesis and delivery to the plasma membrane82, which suggests the presence of a homeostatic mechanism for plasma membrane GSLs. A recent study by Choudhury et al. provided new evidence for the coupling of caveolar endocytosis and secretory transport83. They showed that inhibition of the SNARE protein syntaxin-6 blocked delivery of microdomain-associated lipids and proteins from the Golgi to the plasma membrane in human skin fibroblasts, and this resulted in an inhibition of caveolar internalization. In another study, it was shown that if secretion by a dynamin-independent exocytic pathway is inhibited through siRNA-mediated knock-down of the membrane-fission protein C-terminal binding protein 3/ brefeldin A-ribosylated substrate (CtBP3/BARS), there is a concomitant block in dynamin-independent fluidphase uptake84. Although this result was interpreted as a direct effect of the CtBP3/BARS protein on dynamin-independent endocytosis, it is equally likely that it could be due to a coupling of dynamin-independent endocytosis and secretion.

Finally, an important potential regulator of all of the CI pathways is the actin cytoskeleton — endocytosis via all of these pathways is sensitive to agents that inhibit actin polymerization. Space constraints do not permit a discussion of this topic here, but several key references discuss the roles of the actin cytoskeleton and its regulatory machinery in various endocytic mechanisms15,85,86.

Conclusions and perspectives

The field of CI endocytosis has undergone enormous growth in recent years with the realization that these pathways have important roles in the regulation of cell growth and development, as well as important implications in the study of certain diseases and pathogens. Intense investigation over the past 30 years has uncovered different types of clathrin-mediated endocytic pits and pathways87–89. A similar debate is now underway regarding the distinct CI endocytic mechanisms that exist in eukaryotic cells, the best cargo molecules with which to study a particular pathway, the underlying protein machinery that regulates these pathways, and whether certain CI mechanisms are found only in specialized cell types.

The classification system (FIG. 3) that we have used here is based on the roles of dynamin and several small GTPases, and is likely to evolve as we learn more about this complex field. For example, the classification into dynamin-dependent versus dynamin-independent mechanisms has, in most cases, been assessed by over-expression of individual dynamin-1 or dynamin-2 mutants (for example, DYN2 Lys44Ala). However, other methods are needed to assess the effects of the various dynamin isoforms on CI internalization, such as siRNA-mediated depletion and the use of more specific inhibitors of dynamin90. Thus, the division of CI mechanisms into dynamin-dependent and -independent mechanisms may need to be re-evaluated in the future. Use of the terminology CDC42-, RhoA- or ARF6-regulated may also change if more specific recruiting molecules and effectors are uncovered along with the mechanisms for targeting them to different endocytic pathways. In addition to delineating the nature and number of CI mechanisms, it is important to resolve the confusion between the definitions of existing CI pathways. Morphometric measurements similar to those undertaken by Griffiths91 and, recently, by Parton and colleagues31 will be important for determining the surface area of the membrane that is endocytosed by each pathway.

Many exciting, yet challenging, areas of investigation lie ahead for those studying the CI pathways of internalization. For example, it will be important to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms for cargo selection in the absence of coats and adaptors as well as dissecting the mechanism(s) for vesicle fission that occur in the absence of dynamin. Specifically regarding lipids, another major area that requires further study is the role(s) of cholesterol in each pathway and the molecular basis by which cholesterol influences the different internalization mechanisms. It is also not clear whether additional CI endocytic mechanisms remain to be discovered, nor is it known for certain whether some bacteria or viruses induce their own endocytic itinerary, rather than following an existing trafficking pathway in the cell. Finally, a major challenge in the field will be to understand how all of the various endocytic mechanisms are regulated and integrated with each other and with other transport processes such as secretion. Undoubtedly, there will be a few surprises to come as new studies of CI endocytosis are carried out.

Supplementary Material

Rab GTPase

A Ras family GTPase that regulates membrane-trafficking events in eukaryotic cells. Different Rab proteins are specific for different transport pathways and different subcellular compartments.

Macropinocytosis

A mainly actin-dependent endocytic mechanism that is used to internalize large amounts of fluid and growth factors; vesicles mediating this form of endocytosis are usually uncoated and >500 nm in diameter.

Phagocytosis

An actin-based endocytic mechanism. It is mediated by cup-like membrane extensions that are used to internalize large particles such as bacteria.

Dynamin

A large GTPase of ~100 kDa. It mediates many, but not all, forms of endocytosis as well as vesicle formation from various intracellular organelles through its ability to tubulate and sever membranes.

Caveolae

50–80 nm flask-shaped pits that form in the plasma membrane and are enriched in caveolins, sphingolipids and cholesterol.

Caveosome

An intracellular compartment that is involved in the intracellular transport of simian virus-40 from caveolae to the endoplasmic reticulum.

Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein

A protein that is anchored to the extracellular membrane leaflet through the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol lipid modification rather than through a transmembrane protein domain.

Dominant negative protein

A mutant version of a protein that, when expressed, results in an inhibitory phenotype, usually by competing with interaction partners and thereby suppressing the function of the endogenous wild-type protein.

Carboxypeptidase E

An endopeptidase that is found in secretory vesicles and can activate neuropeptides. It may also function as a sorting receptor that sorts cargoes into the regulated secretory pathway.

Ubiquitylation

A post-translational modification that is added to some receptor tyrosine kinases following ligand binding. It mediates internalization and subsequent sorting at the level of endosomes.

E3 ubiquitin ligase

An enzyme that functions downstream of or in combination with a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) to attach ubiquitin molecules to a target protein, marking the protein for subsequent recognition by ubiquitin-binding domains.

Ubiquitin interacting motif

A protein motif of ~24 amino acids that interacts with ubiquitin and, in some instances, is also necessary for the ubiquitylation of proteins that contain this motif.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

(FRET). A fluorescence-based method for detecting interactions between proteins that are <10 nm apart in a cell. This method is dependent on the spectral overlap between donor and acceptor chromophores and uses the transfer of (non-radiative) energy from an initially excited donor molecule to subsequently excite an acceptor molecule.

Transient confinement zone

A region of the cell membrane that is defined in single-particle diffusion studies of mobile molecules as an area where mobile species are likely to spend more time than expected from the analysis of the trajectory of diffusing species.

Kinome

The entire repertoire of kinases encoded by the genome of an organism.

Guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

A protein that inhibits the removal of guanosine diphosphate from the nucleotide-binding pocket of a GTP-binding protein, thus keeping it in the inactive state.

SNARE

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptor. A family of coiled-coil proteins that operate in paired complexes (vesicle SNAREs and target SNAREs) to mediate the fusion of donor and acceptor membranes, usually between a vesicle and an organelle or two vesicles.

C-terminal binding protein 3/brefeldin A-ribosylated substrate

(CtBP3/BARS). A member of the CtBP transcription co-repressor family of proteins. It is involved in the dynamin-independent fission of vesicles from the plasma membrane as well as from the Golgi apparatus.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to members of the Mayor and Pagano laboratories for comments on the manuscript, and to H.M. Thompson (Mayo Clinic College of Medicine) for expert editorial assistance and for generating the figure in BOX 1. We apologize to colleagues whose work has not been directly cited owing to space limitations. Research in S.M.’s laboratory was supported by a Senior Research Fellowship from The Wellcome Trust, the Department of Biotechnology (India), the Human Frontier Science Program, and intramural funds from the National Centre for Biological Sciences, India. Research in R.P.’s laboratory was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the National Niemann–Pick Disease Foundation, and intramural funds from the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Satyajit Mayor, Email: mayor@ncbs.res.in.

Richard E. Pagano, Email: pagano.richard@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Pearse BM. Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1255–1259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1255. [Describes the isolation of highly purified coated vesicles from different sources and demonstrates that clathrin is the major coat protein, setting the stage for mechanistic studies of a prototypic coated-pit pathway] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousavi SA, Malerod L, Berg T, Kjeken R. Clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Biochem J. 2004;377:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth MG. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis before fluorescent proteins. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traub LM. Common principles in clathrin-mediated sorting at the Golgi and the plasma membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1744:415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh M, Helenius A. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkham M, Parton RG. Clathrin-independent endocytosis: new insights into caveolae and non-caveolar lipid raft carriers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:350–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damke H, Baba T, van der Bliek AM, Schmid SL. Clathrin-independent pinocytosis is induced in cells overexpressing a temperature-sensitive mutant of dynamin. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:69–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.69. [Key paper demonstrating that inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis results in an upregulation of clathrin-and dynamin-independent pinocytic endocytosis] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guha A, Sriram V, Krishnan KS, Mayor S. Shibire mutations reveal distinct dynamin-independent and-dependent endocytic pathways in primary cultures of Drosophila hemocytes. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3373–3386. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson JG, Klausner RD. ARF: a key regulatory switch in membrane traffic and organelle structure. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:527–532. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis S, Mellor H. Regulation of endocytic traffic by rho family GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss J, Vaughan M. Structure and function of ARF proteins: activators of cholera toxin and critical components of intracellular vesicular transport processes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12327–12330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qualmann B, Mellor H. Regulation of endocytic traffic by Rho GTPases. Biochem J. 2003;371:233–241. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG. Actin assembly and endocytosis: from yeast to mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:287–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.093127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol. 2004;265:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mineo C, Anderson RG. Potocytosis. Robert Feulgen Lecture. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s004180100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parton RG. Caveolae — from ultrastructure to molecular mechanisms. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:162–167. doi: 10.1038/nrm1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parton RG, Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aboulaich N, Vainonen JP, Stralfors P, Vener AV. Vectorial proteomics reveal targeting, phosphorylation and specific fragmentation of polymerase I and transcript release factor (PTRF) at the surface of caveolae in human adipocytes. Biochem J. 2004;383:237–248. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemaitre G, et al. CD98, a novel marker of transient amplifying human keratinocytes. Proteomics. 2005;5:3637–3645. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprenger RR, et al. Comparative proteomics of human endothelial cell caveolae and rafts using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:156–172. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minshall RD, Tiruppathi C, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Vesicle formation and trafficking in endothelial cells and regulation of endothelial barrier function. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s00418-001-0367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnitzer JE, Oh P. Albondin-mediated capillary permeability to albumin. Differential role of receptors in endothelial transcytosis and endocytosis of native and modified albumins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6072–6082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RD, et al. Selective caveolin-1-dependent endocytosis of glycosphingolipids. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3254–3265. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng ZJ, et al. Distinct mechanisms of clathrin-independent endocytosis have unique sphingolipid requirements. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3197–3210. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1101. [A systematic study that shows the importance of different classes of sphingolipids in modulating various mechanisms of endocytosis] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damm EM, et al. Clathrin-and caveolin-1-independent endocytosis: entry of simian virus 40 into cells devoid of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:477–488. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkham M, et al. Ultrastructural identification of uncoated caveolin-independent early endocytic vehicles. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massol RH, Larsen JE, Fujinaga Y, Lencer WI, Kirchhausen T. Cholera toxin toxicity does not require functional Arf6-and dynamin-dependent endocytic pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3631–3641. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlandi PA, Fishman PH. Filipin-dependent inhibition of cholera toxin: evidence for toxin internalization and activation through caveolae-like domains. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:905–915. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torgersen ML, Skretting G, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Internalization of cholera toxin by different endocytic mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3737–3742. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamaze C, et al. Interleukin-2 receptors and detergent-resistant membrane domains define a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00212-x. [An important study showing that IL2-R is internalized by a clathrin-independent mechanism that requires dynamin and is specifically regulated by RhoA] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fivaz M, et al. Differential sorting and fate of endocytosed GPI-anchored proteins. EMBO J. 2002;21:3989–4000. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabharanjak S, Sharma P, Parton RG, Mayor S. GPI-anchored proteins are delivered to recycling endosomes via a distinct CDC42-regulated, clathrin-independent pinocytic pathway. Dev Cell. 2002;2:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00145-4. [A mechanistic study of a distinct constitutive pinocytic pathway that is responsible for the transport of GPI-APs, is dynamin-independent and is regulated by CDC42] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Llorente A, Rapak A, Schmid SL, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Expression of mutant dynamin inhibits toxicity and transport of endocytosed ricin to the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:553–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simpson JC, Smith DC, Roberts LM, Lord JM. Expression of mutant dynamin protects cells against diphtheria toxin but not against ricin. Exp Cell Res. 1998;239:293–300. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gauthier NC, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin: a probe for a clathrin-independent and Cdc42-dependent pinocytic pathway routed to late endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4852–4866. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalia M, et al. Arf6-independent GPI-anchored protein-enriched early endosomal compartments fuse with sorting endosomes via a Rab5/phosphatidylinositol-3′-kinase-dependent machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3689–704. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma P, Sabharanjak S, Mayor S. Endocytosis of lipid rafts: an identity crisis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:205–214. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shyng SL, Heuser JE, Harris DA. A glycolipid-anchored prion protein is endocytosed via clathrin-coated pits. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1239–1250. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sunyach C, et al. The mechanism of internalization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored prion protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:3591–3601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters PJ, et al. Trafficking of prion proteins through a caveolae-mediated endosomal pathway. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:703–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shyng SL, Moulder KL, Lesko A, Harris DA. The N-terminal domain of a glycolipid-anchored prion protein is essential for its endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14793–14800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garrett WS, et al. Developmental control of endocytosis in dendritic cells by CDC42. Cell. 2000;102:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chadda R, et al. Cholesterol-sensitive CDC42 activation regulates actin polymerization for endocytosis via the GEEC pathway. Traffic. 2007;8:702–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naslavsky N, Weigert R, Donaldson JG. Characterization of a nonclathrin endocytic pathway: membrane cargo and lipid requirements. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3542–3552. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abrami L, Liu S, Cosson P, Leppla SH, van der Goot FG. Anthrax toxin triggers endocytosis of its receptor via a lipid raft-mediated clathrin-dependent process. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:321–328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigismund S, et al. Clathrin-independent endocytosis of ubiquitinated cargos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2760–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409817102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoddart A, et al. Lipid rafts unite signaling cascades with clathrin to regulate BCR internalization. Immunity. 2002;17:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Birkle S, Zeng G, Gao L, Yu RK, Aubry J. Role of tumor-associated gangliosides in cancer progression. Biochimie. 2003;85:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnaoutova I, Jackson CL, Al-Awar OS, Donaldson JG, Loh YP. Recycling of raft-associated prohormone sorting receptor carboxypeptidase E requires interaction with ARF6. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4448–4457. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma P, et al. Nanoscale organization of multiple GPI-anchored proteins in living cell membranes. Cell. 2004;116:577–589. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glebov OO, Bright NA, Nichols BJ. Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:46–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parton RG, Joggerst B, Simons K. Regulated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1199–1215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1199. [Demonstrates that caveolae are dynamic structures that undergo internalization and that this process is regulated by kinase activity and a network of actin] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayor S, Rao M. Rafts: scale-dependent, active lipid organization at the cell surface. Traffic. 2004;5:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madore N, et al. Functionally different GPI proteins are organized in different domains on the neuronal surface. EMBO J. 1999;18:6917–6926. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puri V, et al. Clathrin-dependent and-independent internalization of plasma membrane sphingolipids initiates two Golgi targeting pathways. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:535–547. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma DK, et al. Selective stimulation of caveolar endocytosis by glycosphingolipids and cholesterol. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3114–3122. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh RD, et al. Caveolar endocytosis and microdomain association of a glycosphingolipid analog is dependent on its sphingosine stereochemistry. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30660–30668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morrow IC, Parton RG. Flotillins and the PHB domain protein family: rafts, worms and anaesthetics. Traffic. 2005;6:725–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stuermer CA, et al. Glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored proteins and FYN kinase assemble in noncaveolar plasma membrane microdomains defined by reggie-1 and -2. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3031–3045. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slepnev VI, De Camilli P. Accessory factors in clathrin-dependent synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:161–172. doi: 10.1038/35044540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nrm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mukherjee S, Soe TT, Maxfield FR. Endocytic sorting of lipid analogues differing solely in the chemistry of their hydrophobic tails. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1271–1284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1271. [An important study demonstrating that lipid sorting along the endocytic pathway is affected by the hydrophobic tails of lipids] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma DK, et al. Glycosphingolipids internalized via caveolar-related endocytosis rapidly merge with the clathrin pathway in early endosomes and form microdomains for recycling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7564–7572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sonnichsen B, De Renzis S, Nielsen E, Rietdorf J, Zerial M. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [A seminal study that describes the sequestration of different Rab proteins into discrete domains on individual endosomes] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pelkmans L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of human kinases in clathrin-and caveolae/raft-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2005;436:78–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03571. [High-throughput screening of the human kinome showing that the signalling functions of cells are linked to endocytosis and vice versa] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh RD, et al. Inhibition of caveolar uptake, SV40 infection, and β1-integrin signaling by a non-natural glycosphingolipid stereoisomer. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:895–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tagawa A, et al. Assembly and trafficking of caveolar domains in the cell: caveolae as stable, cargo-triggered, vesicular transporters. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tiruppathi C, Song W, Bergenfeldt M, Sass P, Malik AB. Gp60 activation mediates albumin transcytosis in endothelial cells by tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25968–25975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsai B, et al. Gangliosides are receptors for murine polyoma virus and SV40. EMBO J. 2003;22:4346–4355. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sharma DK, et al. The glycosphingolipid, lactosylceramide, regulates β1-integrin clustering and endocytosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8233–8241. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guerrera M, Ladisch S. N-butyldeoxynojirimycin inhibits murine melanoma cell ganglioside metabolism and delays tumor onset. Cancer Lett. 2003;201:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vieira AV, Lamaze C, Schmid SL. Control of EGF receptor signaling by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1996;274:2086–2089. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nevins AK, Thurmond DC. Caveolin-1 functions as a novel CDC42 guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18961–18972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heuser JE, Reese TS. Evidence for recycling of synaptic vesicle membrane during transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol. 1973;57:315–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riezman H. Endocytosis in yeast: several of the yeast secretory mutants are defective in endocytosis. Cell. 1985;40:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ito M, Komori H. Homeostasis of cell-surface glycosphingolipid content in B16 melanoma cells. Evidence revealed by an endoglycoceramidase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12655–12660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choudhury A, Marks DL, Proctor KM, Gould GW, Pagano RE. Regulation of caveolar endocytosis by syntaxin 6-dependent delivery of membrane components to the cell surface. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:317–328. doi: 10.1038/ncb1380. [Inhibition of a target SNARE that is involved in secretory transport leads to selective inhibition of caveolar endocytosis] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bonazzi M, et al. CtBP3/BARS drives membrane fission in dynamin-independent transport pathways. Nature Cell Biol. 2005;7:570–580. doi: 10.1038/ncb1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. Harnessing actin dynamics for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pelkmans L, Püntener D, Helenius A. Local actin polymerization and dynamin recruitment in SV40-induced internalization of caveolae. Science. 2002;296:535–539. doi: 10.1126/science.1069784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haucke V. Cargo takes control of endocytosis. Cell. 2006;127:35–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Zhuang X. Ligands for clathrin-mediated endocytosis are differentially sorted into distinct populations of early endosomes. Cell. 2006;124:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M. Cargo regulates clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Cell. 2006;127:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Macia E, et al. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Griffiths G, Back R, Marsh M. A quantitative analysis of the endocytic pathway in baby hamster kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2703–2720. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rodal SK, et al. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:961–974. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Subtil A, et al. Acute cholesterol depletion inhibits clathrin-coated pit budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6775–6780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujimoto LM, Roth R, Heuser JE, Schmid SL. Actin assembly plays a variable, but not obligatory role in receptor-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. Traffic. 2000;1:161–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Edidin M. The state of lipids rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.London E, Brown DA. Insolubility of lipids in Triton X-100: physical origin and relationship to sphingolipid/cholesterol membrane domains (rafts) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1508:182–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brown DA, London E. Structure and origin of ordered lipid domains in biological membranes. J Membr Biol. 1998;164:103–114. doi: 10.1007/s002329900397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maxfield FR. Plasma membrane microdomains. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:483–487. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sarasij RC, Mayor S, Rao M. Chirality-induced budding: a raft-mediated mechanism for endocytosis and morphology of caveolae? Biophys J. 2007;92:3140–3158. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu J, Kaksonen M, Drubin DG, Oster G. Endocytic vesicle scission by lipid phase boundary forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10277–10282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:329–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Heuser JE, Anderson RG. Hypertonic media inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis by blocking clathrin-coated pit formation. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Anderson RG. The caveolae membrane system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Henley JR, Krueger EW, Oswald BJ, McNiven MA. Dynamin-mediated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:85–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.85. [One of the first demonstrations that caveolar endocytosis is dynamin-dependent] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fujimoto T. GPI-anchored proteins, glycosphingolipids, and sphingomyelin are sequestered to caveolae only after crosslinking. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:929–941. doi: 10.1177/44.8.8756764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mayor S, Rothberg KG, Maxfield FR. Sequestration of GPI-anchored proteins in caveolae triggered by cross-linking. Science. 1994;264:1948–1951. doi: 10.1126/science.7516582. [Demonstrates that crosslinking GPI-anchored proteins induces their internalization by caveolae.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.