Abstract

Background and Aims

Vagal parasympathetic dysfunction is strongly associated with impaired exercise tolerance, indicating that coordinated autonomic control is essential for optimizing exercise performance. This study tested the hypothesis that autonomic neuromodulation by non-invasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) can improve exercise capacity in humans.

Methods

This single-centre, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover trial in 28 healthy volunteers evaluated the effect of bilateral transcutaneous stimulation of vagal auricular innervation, applied for 30 min daily for 7 days, on measures of cardiorespiratory fitness (peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak)) during progressive exercise to exhaustion. Secondary endpoints included peak work rate, cardiorespiratory measures, and the whole blood inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide ex vivo.

Results

tVNS applied for 30 min daily over 7 consecutive days increased VO2peak by 1.04 mL/kg/min (95% CI: .34–1.73; P = .005), compared with no change after sham stimulation (−0.54 mL/kg/min; 95% CI: −1.52 to .45). No carry-over effect was observed following the 2-week washout period. tVNS increased work rate (by 6 W; 95% CI: 2–10; P = .006), heart rate (by 4 bpm; 95% CI: 1–7; P = .011), and respiratory rate (by 4 breaths/min; 95% CI: 2–6; P < .001) at peak exercise. Analysis of the whole blood transcriptomic response to lipopolysaccharide in serial samples obtained from five participants showed that tVNS reduced the inflammatory response.

Conclusions

Non-invasive vagal stimulation improves measures of cardiorespiratory fitness and attenuates inflammation, offering an inexpensive, safe, and scalable approach to improve exercise capacity.

Keywords: Ageing, Autonomic nervous system, Exercise, Neuromodulation, Vagus nerve

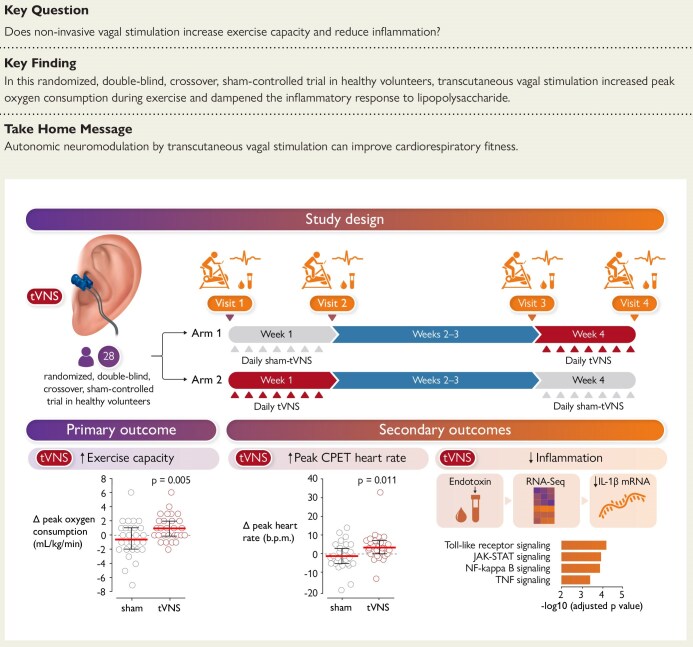

Structured Graphical Abstract

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Methods, primary and secondary outcomes for randomized, double-blind, crossover, sham-controlled trial of non-invasive vagal stimulation in healthy volunteers. tVNS, transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; RNAseq, RNA sequencing; IL-1β mRNA, interleukin-1 beta messenger RNA; JAK-STAT, Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription; NF-kappa B, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Translational perspective.

Non-invasive autonomic neuromodulation through transcutaneous vagal stimulation improves measures of cardiorespiratory fitness and restrains inflammation, offering an inexpensive, safe, and scalable approach that may improve cardiovascular health.

Introduction

Maintaining physical activity is essential for every aspect of cardiovascular, emotional, and cognitive health.1 Higher exercise capacity is strongly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, malignancy, neurodegenerative disease, and premature death.2 Regular exercise is required to maintain and improve cardiorespiratory fitness.3 Programmed moderate-to-vigorous physical activity has been demonstrated to be the most effective and time-efficient protective intervention for improving cardiometabolic outcomes.4 However, public policy measures aimed at achieving this goal by promoting physical activity at scale have had only a very modest impact.5

The autonomic nervous system controls the heart and circulation by the dynamic recruitment and withdrawal of parasympathetic (vagal) and sympathetic activities.6 Exercise capacity is critically dependent on highly orchestrated autonomic cardiovascular and respiratory responses required to support the metabolic demands of exercise.7 The increase in cardiac output during exercise occurs through sympathetic stimulation and vagal modulation8; both are essential for optimal physical performance.9 It is well known that higher exercise capacity is strongly associated with lower resting heart rate, indicative of increased cardiac vagal activity.10 Large clinical studies have demonstrated a robust association between vagal dysfunction, cardiovascular morbidity, and all-cause mortality.11,12 A more recent study in 1293 subjects aged over 65 years confirmed that vagal autonomic dysfunction is strongly associated with impaired exercise tolerance.9 There is also significant experimental and clinical evidence indicating that both acute inflammation and chronic inflammation are modulated by autonomic mechanisms,13 the recruitment of which can confer the anti-inflammatory benefits of exercise.

Advances in device-based non-invasive neurostimulation have made it possible to modulate autonomic balance in humans by applying low-intensity electrical stimulation to the vagal sensory innervation of the outer ear.14 Stimulation of certain regions of the pinna (such as the cymba conchae and the tragus, innervated by the auricular branch of the vagus nerve), called transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS), shifts autonomic activity towards a net vagal dominance.15–17 Autonomic neuromodulation via tVNS has been shown to confer organ protection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury18 and reduce inflammation.19

In heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction, electrical stimulation applied directly to the cervical vagus nerve was reported to increase 6-minute walking distance, although it had no effect on cardiac function, and objective measures of cardiorespiratory fitness were not assessed.20 This randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover trial was designed to test the hypothesis that tVNS can improve exercise capacity and modulate the inflammatory response in healthy volunteers (Structured Graphical Abstract).

Methods

Study design and cohort

This single-centre trial was designed, implemented, and reported in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guideline.21 We employed a crossover design, as this enables the effects of interventions to be compared with high precision by avoiding between-patient variation.22 The study protocol was approved by the National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (21/LO/0856). The study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov on 18 October 2022 (NCT05619107), before the first participant was recruited. The results of the study are reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist for randomized crossover trials (see Supplementary data online, Table S1).

Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers (age >18 years), who then underwent a medical screening questionnaire after recruitment through local advertisements. Participants did not receive any compensation, except for reimbursement of travel expenses. There was no upper age limit. Individuals participating in dedicated exercise programs or those with relative contraindications to undertaking exhaustive cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) were excluded (see Supplementary data online, Table S2).23 Careful consideration was taken to ensure that there was a balance of sexes across the study. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Queen Mary University of London.24

Randomization and blinding

The randomized allocation of sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment was designed to minimize random effects of changes in activity between the participants. The crossover study design minimizes confounding factors that can occur in parallel-design studies and enables each participant to act as their own control, allowing between- and within-group comparisons.22 Volunteers were randomized to first receive either sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment in blocks of four without minimization (NCSS 11 Statistical Software, NCSS, Kaysville, USA). The randomization code was known only to the investigator who programmed the devices. Each device was labelled with the participant number, A or B. Investigators who recruited participants and performed the physiological testing were unaware of the volunteers’ study arm allocation or the randomization sequence. Both the investigators and participants were blinded to the study arm allocation and the results of CPET (except for SM, who conducted the CPET sessions).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

CPET was undertaken at the Sport and Exercise Medicine Exercise Facility, Queen Mary University of London. All tests were conducted at the same time of day between 9_a.m. and 12_p.m. After completing a health screening questionnaire and providing written consent, participants were instrumented with leads to capture ECG, which was recorded (Holter monitors, Spacelabs) for 10_min in the supine position before the participants were asked to stand for 3_min to assess the heart rate response to a standardized orthostatic challenge. Approximately 10_min after the resting ECG recordings, participants proceeded to undertake exhaustive symptom-limited CPET using a standard incremental ramp protocol on an electromagnetically-braked Lode Excalibur Sport Cycle Ergometer (Lode Instrumenten, Groningen, The Netherlands). Equipment was calibrated prior to each testing session. Data were collected using the cycle ergometer software (MetasoftR Studio, Leipzig, Germany).

Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation

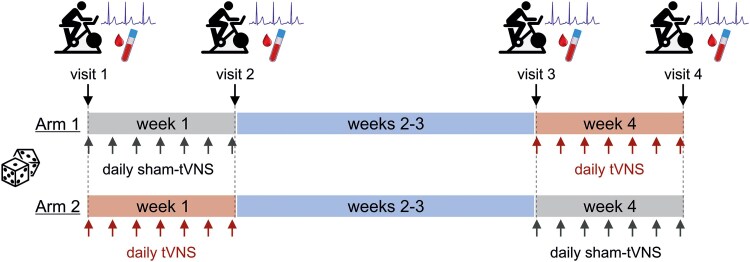

Volunteers were randomly allocated to receive sham-tVNS or tVNS for 30_min daily for 7 consecutive days (Figure 1). This protocol design was based on the results of preclinical studies that demonstrated increases in exercise capacity in experimental animals (rats) after 1 week of daily stimulations of vagal preganglionic neurons in the brainstem.9 We noted that most published studies involving longer periods of tVNS used unilateral auricular stimulations; in this study, tVNS was applied to both ears. This stimulation protocol was chosen based on evidence suggesting that applying sensory stimuli bilaterally is more effective than unilateral stimulations in inducing brain plasticity and repair.25,26

Figure 1.

Study protocol. 28 volunteers (14 females) were randomized into two arms of the study to first receive either sham-tVNS or tVNS applied for 30 min daily for 7 consecutive days, followed by a 2-week washout period before receiving the alternative treatment. At each visit, after 10 min of ECG recording followed by orthostatic testing, participants undertook exhaustive cardiopulmonary exercise testing using cycle ergometry. Participants were issued individual sham-tVNS or tVNS device units and were trained and instructed to use the device for 30 min at a standardized time each day for 7 consecutive days. Volunteers were contacted by video call during each session to ensure correct electrode clip placement and correct device use, as well as to monitor for potential adverse effects. A 10 mL venous blood sample was obtained at each visit from the participants who consented to repeated venepuncture

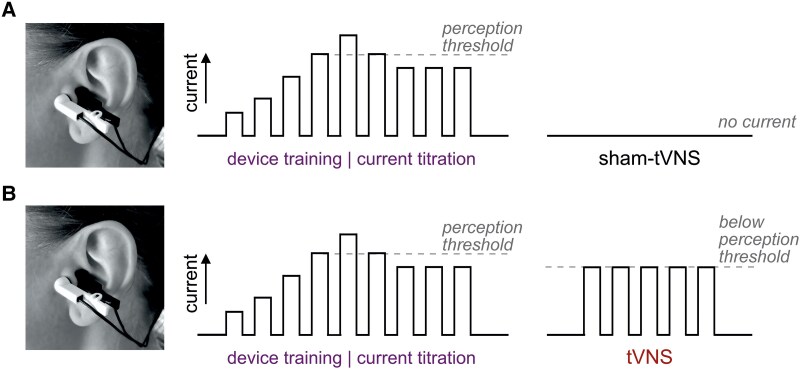

Individual sensitivities of the auricular tragi regions to electrical stimulation were determined during the first and third (baseline) visits using a dedicated battery-operated TENS training device (Totally TENS, Well-Life Healthcare). During device training, participants were instructed to place the electrode clips (with electrode surfaces made of electrically-conductive rubber) on the left and right tragi (Figure 2). The current amplitude was then gradually increased by the investigator conducting the training, starting from 0.1_mA, until the participant felt a tingling sensation, after which it was reduced to set the level of stimulation at ∼1.5_mA below this threshold. Once the threshold current was determined, participants were issued their individual TENS units, which were identical to the training device but with concealed controls. Stimulation current was set to 0_mA (sham-tVNS) or ∼1.5_mA below the individual perception threshold (tVNS), with 200_μs pulses generated at a frequency of 25_Hz.27,28 The stimulation current applied by participants receiving tVNS ranged between 4 and 12_mA.

Figure 2.

Device settings. The individual sensitivities of the auricular tragi regions to electrical stimulation were determined during the first and third visits using a dedicated training device. During device training, participants were instructed to place the electrode clips on the left and right tragi. The current amplitude was gradually increased by the investigator conducting the training, starting from 0.1 mA, until the participant felt a tingling sensation. The current was then reduced to set the level of stimulation at ∼1.5 mA below this threshold. Once this threshold current was determined, participants were issued their personal device units, identical to the training device but with concealed controls. The stimulation current was set to 0 mA (A, sham-tVNS) or ∼1.5 mA below the individual perception threshold (B, tVNS), with 200 μs pulses generated at a frequency of 25 Hz

Volunteers were instructed to use the device for 30_min daily for 7 consecutive days and were contacted by video call during each session to ensure correct electrode clip placement and correct device use, as well as to monitor for potential adverse effects. Pre-specified side effects were sought daily (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2), and volunteers were asked to confirm that they remained blinded to the intervention.

Heart rate variability analysis

A researcher, blinded to study arm allocation, cleaned the ECG data, and used Kubios heart rate variability (HRV) Premium Version 3.5.0 software (Kubios, Kuopio, Finland) to derive HRV metrics from RR intervals using both time- and frequency-domain analyses from 5-minute epochs, in accordance with the recommendations of the ESC task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology.29 Participants underwent a 10-minute ECG recording session, during which they rested undisturbed in the supine position. Data from the last 5_min of the recording period were analysed.

Time-domain parameters included mean heart rate, the standard deviation of RR intervals (SDNN), and the root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD). Frequency-domain analysis was performed in an equidistantly sampled time series (cubic spline interpolation) using a sampling frequency of 5_Hz. Frequency-domain analysis was performed using the autoregressive method (which offers superior spectral analysis for the shorter data sequences30) to calculate spectral power (ms2) in the very low (<0.04_Hz), low (0.04–0.15_Hz), and high (0.15–0.4_Hz) frequency bands. The very-low frequency band of HRV is influenced by the activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, but depends primarily on parasympathetic drive31 and has a stronger association with adverse cardiovascular outcomes.32 Low-frequency HRV reflects sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic cardiac modulation under the control of the arterial baroreflex.33 The high-frequency HRV in most individuals reflects rhythmic parasympathetic modulation of heart rate in synchrony with respiration.34

RNAseq to study the inflammatory response ex vivo

Whole blood stimulation with an inflammatory ligand (lipopolysaccharide) was used to study the inflammatory response ex vivo.35 Participants were invited to provide four blood samples during the study, but this was not obligatory. Blood samples (10_mL) were collected into citrated containers and incubated with either sterile saline or Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (O111:B4; 20_ng/mL, Sigma, UK) at 37°C for 4_h. The samples were then transferred to PAXgene™ tubes (PreAnalytiX, Switzerland) for RNA stabilization, and stored at −80°C until assayed. Total RNA was extracted using the PAXGene RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a DNase step included to remove contaminating DNA. RNA samples were assessed for quantity and integrity using the NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer v2.0 (ThermoScientific, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), respectively. All samples that displayed an RIN score of 6.5 or higher were used for RNA library preparation (NEBNext Globin & rRNA Depletion Kit). Samples were randomized before library preparation and sequencing using NextSeq2000 P3 100-cycle kit (Illumina Inc., Cambridge, UK). Full details on RNAseq and analysis are provided in Supplementary Data.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the absolute change in VO2peak following sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment. Pre-specified secondary outcomes included work rate, respiratory rate, and heart rate at peak exercise, resting heart rate (recorded in the supine position), time- and frequency-domain HRV measures of cardiac autonomic modulation, heart rate recovery (HRR) 1_min after cessation of CPET, and the whole blood inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide ex vivo.

Data analysis

The robust repeated crossover design, which separates time period effects from treatment effects, remains valid only if no treatment × period interaction exists; therefore, a comparison of data obtained during Visits 1 and 3 was undertaken. If neither carry-over nor period effects are found, the appropriate analysis of continuous data from a two-period, two-intervention crossover trial is a paired t-test.36

As baseline readings did not differ between interventions, pairwise contrasts for sham-tVNS and tVNS were treated as independent groups. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made, as the study outcomes had been pre-specified in the analysis plan. All other outcomes were considered exploratory.

The statistical analyses were predefined in the protocol and the statistical analysis plan and finalized before unblinding (see Supplementary Data). There were no interim analyses or stopping rules. The sample size of 28 participants was calculated to allow detection of at least a 0.5_mL/kg/min difference in VO2peak for the crossover design, with 90% power and a type I error rate of 5%, assuming a standard deviation of 0.8_mL/kg/min for the difference between the two values for the same participant. For the age range of volunteers recruited, predicted VO2peak values for below-average to average cardiorespiratory fitness levels are between 31 and 38_mL/kg/min for women and between 35 and 42_mL/kg/min for men.37 Sample size justification for the RNAseq analysis is provided in Supplementary Data.

Results

Study cohort

42 healthy volunteers were assessed for eligibility, of whom 28 participants (mean age: 34 years old; range: 20–63; 50% female; Supplementary data online, Table S3) were randomized between 9 November 2022 and 16 May 2023. Every participant completed all four study visits, with 100% compliance for all interventions and physiological assessments (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1).

Safety and adverse effects

The mean electrical stimulation current applied by the participants of this trial was 5.5 ± 2_mA. Participants were unable to correctly identify their study group allocation (sham-tVNS or tVNS) on direct questioning (see Supplementary data online, Table S4). Pre-specified side effects were similar between the arms of the study (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2).

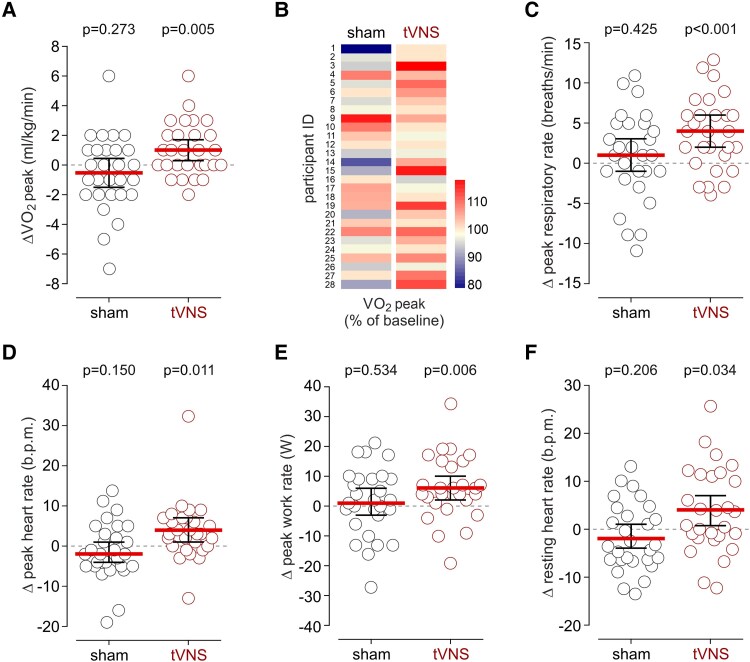

Primary outcome: peak oxygen consumption

The mean VO2peak recorded in the participants during the first visit was 32.9_mL/kg/min (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 29.4–36.4). Mean VO2peak values were similar between baseline Visits 1 and 3 (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3). tVNS applied for 30 min daily over 7 consecutive days increased VO2peak by 1.04_mL/kg/min (95% CI: .34–1.73; P = .005); there was no change in VO2peak after sham-tVNS (mean difference: −0.54_mL/kg/min; 95% CI: −1.52 to .45; P = .273) (Figure 3A; Supplementary data online, Figures S4–6). This effect of tVNS equated to a 3.8% (95% CI: 1.5–6.1) increase in VO2peak (Figure 3B), compared with no change after sham-tVNS (mean difference: −1.3%; 95% CI: −4.26 to 1.56).

Figure 3.

The effect of tVNS on measures of exercise capacity. (A) tVNS increased VO2peak by 1.04 mL/kg/min (95% CI: .34–1.73), compared to no change after sham stimulation (−0.54 mL/kg/min; 95% CI: −1.52 to .45). (B) Percentage changes in VO2peak after sham-tVNS or tVNS illustrated by heatmaps. tVNS increased VO2peak by 3.8% (95% CI: 1.5–6.1), compared with no change after sham-tVNS (mean difference: −1.3%, 95% CI: −4.26 to 1.56). (C) tVNS increased respiratory rate at peak exercise by 4 breaths/min (95% CI: 2–6), compared to no change after sham stimulation. (D) tVNS increased peak heart rate by 4 b.p.m. (95% CI: 1–7), compared to no change after sham stimulation. (E) tVNS increased power output at peak exercise by 6 W (95% CI: 2–10), compared to no change after sham stimulation. (F) tVNS increased resting heart rate measured in the supine position before CPET by 4 b.p.m. (95% CI: 1–7). Individual values and means (95% CI) are shown. P-values were determined by paired t-test comparisons between measurements taken at baseline and after sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment

Secondary outcomes

Respiratory rate at peak exercise recorded in the participants that received tVNS treatment was higher by 4_breaths/min (95% CI: 2–6; P < .001); there was no change in peak respiratory rate after sham-tVNS (1_breaths/min; 95% CI: −1 to 3) (Figure 3C). Heart rate at peak exercise was higher by 4_b.p.m. (95% CI: 1–7; P = .011) following tVNS treatment, compared to no change (−2_b.p.m.; 95% CI: −4 to 1) after sham-tVNS (Figure 3D). The mean peak work rate at the first visit was 220_W (95% CI: 193–247). tVNS increased power output at peak exercise by 6_W (95% CI: 2–10; P = .006); there was no change in peak work rate after sham-tVNS (1_W; 95% CI: −3 to 6) (Figure 3E; Supplementary data online, Figure S7).

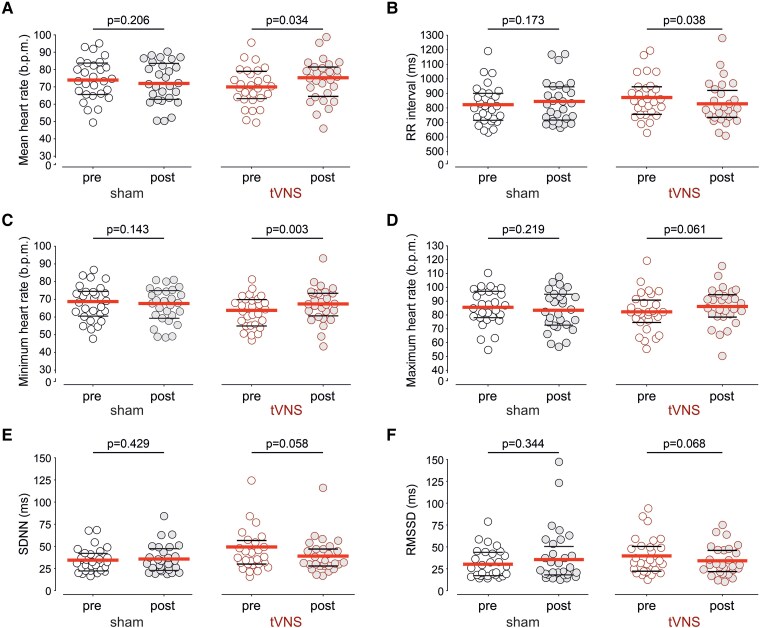

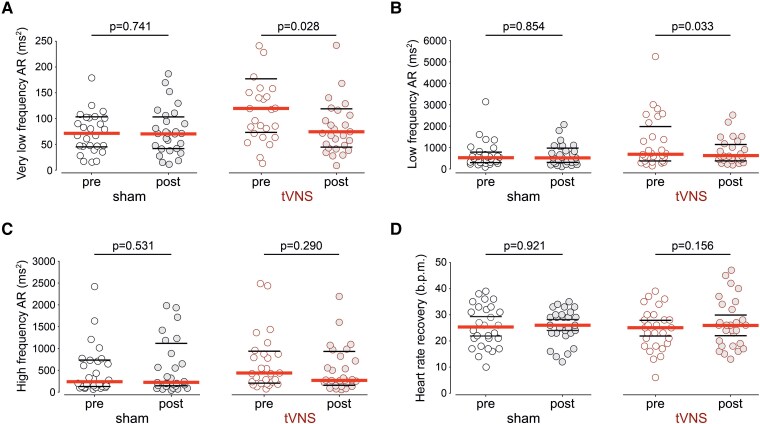

Explanatory measures: cardiac autonomic modulation

tVNS increased the resting heart rate measured in the supine position (before CPET) by 4_b.p.m. (95% CI: 1–7; P = .034; Figures 3F and 4A), with RR interval reduced by 42_ms (95% CI: 2–81; P = .038), compared to no change after sham-tVNS (22_ms; 95% CI: −10 to 55; P = .173) (Figure 4B). This increase in mean resting heart rate after tVNS treatment was accompanied by a higher supine minimum heart rate (Figure 4C). The orthostatic heart rate response to standing was not affected by sham-tVNS or tVNS (see Supplementary data online, Figure S8). tVNS treatment reduced SDNN and RMSSD (Figure 4E, F) and decreased the power of very-low frequency (Figure 5A) and low frequency (Figure 5B) HRV bands, but had no effect on the high-frequency HRV band (Figure 5C). HRR after the end of peak exercise was similar after sham-tVNS and tVNS treatment (Figure 5D).

Figure 4.

The effect of tVNS on time-domain measures of heart rate variability. Mean heart rate (absolute values, A), RR interval (B), minimum heart rate (C), maximum heart rate (D), standard deviation of the RR intervals (SDNN, E), and the root mean square of successive differences between normal heartbeats (RMSSD, F) were derived from ECG recordings obtained from participants in the supine position before and after sham-tVNS or tVNS. Individual values, medians, and 25th–75th percentiles are shown. P-values were determined by paired t-test comparisons between measurements taken at baseline and after sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment

Figure 5.

The effect of tVNS on frequency-domain measures of heart rate variability and heart rate recovery after exercise. Very-low frequency (<0.04 Hz, A), low frequency (0.04–0.15 Hz, B), and high frequency (0.15–0.4 Hz, C) bands of the HRV power spectrum were derived from the analysis of ECG recordings obtained from participants in the supine position before and after sham-tVNS or tVNS. (D) Heart rate recovery 1 min after the end of peak exercise, measured before and after sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment. Individual values, medians, and 25th–75th percentiles are shown. P-values were determined by paired t-test comparisons between measurements taken at baseline and after sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment

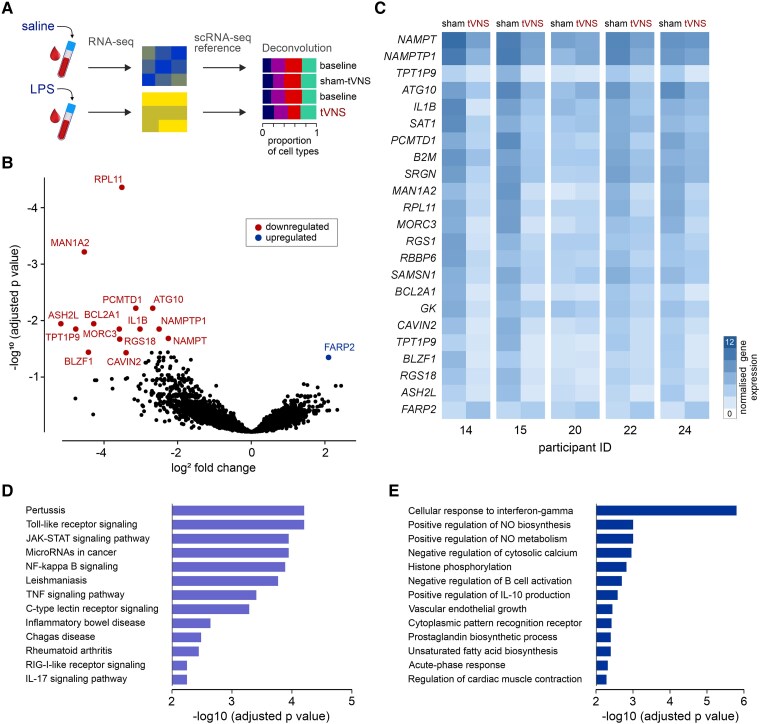

Exploratory analysis: acute inflammation ex vivo

We analysed the whole blood transcriptomic responses to lipopolysaccharide before and after sham-tVNS or tVNS in five trial participants who consented to venepuncture on each visit and who were randomized to sham-tVNS first (Figure 6A). Bioinformatic analysis of bulk RNAseq identified genes and signalling pathways activated by lipopolysaccharide (Figure 6B). Deconvolution of RNAseq data found similar proportions of immune cells in samples collected on each visit (see Supplementary data online, Figure S9). There were no transcriptomic differences between samples incubated with saline at each visit (see Supplementary data online, Figure S10). In blood samples collected from the participants that received tVNS treatment, the transcriptional response to lipopolysaccharide was markedly reduced, with fewer differentially expressed genes (FDR ≤ 0.05, minimum fold-change ≥ 1.5; χ²(3, 66 090) = 699.1, P < .0001; Supplementary data online, Figure S11), and 23 (of 16 789) genes including the transcript for the key pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β significantly downregulated (Figure 6C). Pathway analysis demonstrated that tVNS modulated signalling pathways (Figure 6D) through which vagal activity has been shown to restrain inflammation, including alpha-7 nicotinic receptor regulated Jak2-STAT3 signalling pathway.38 Pathways differentially affected by tVNS were predominantly those involved in the acute inflammatory response (Figure 6E; Supplementary data online, Figures S12–15).

Figure 6.

The effect of tVNS on the inflammatory response. (A) Whole blood samples were obtained from five volunteers who consented to repeated venepuncture. The samples were incubated with either sterile saline or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 20 ng/mL). Bulk RNAseq was performed, followed by single-cell RNAseq referenced deconvolution. (B) Volcano plot illustrating differentially expressed genes in LPS-treated whole blood samples obtained from the participants that received sham-tVNS or tVNS. P-values were calculated using Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment (FDR < 0.05) for multiple testing. (C) Heatmap illustrating changes in the expression of 23 genes that were differentially affected by tVNS (false discovery rate <0.05; minimum fold-change ≥1.5). (D) Gene Ontology (KEGG) enrichment analysis for signaling pathways affected by tVNS. (E) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis for cellular processes affected by tVNS, derived from the genes differentially expressed in response to LPS stimulation

Discussion

The results of this randomized, sham-controlled, crossover trial in healthy volunteers show that autonomic neuromodulation by tVNS improves measures of cardiorespiratory fitness and restrains inflammation, offering an inexpensive, safe, and scalable approach to improve cardiovascular health. The outcome of the trial is consistent with the significant body of evidence suggesting that autonomic health is strongly associated with higher exercise tolerance7,9 and reduced systemic inflammation, mediated by vagal parasympathetic activity.39,40 This is the first sham-controlled crossover trial to examine the effect of tVNS on exercise capacity, cardiac autonomic activity, and inflammatory response. The crossover study design minimized confounding factors because each participant acted as their own control, allowing within-group comparisons.22

The magnitude of the tVNS effect observed in this study is functionally significant and clinically meaningful, given that tVNS applied for just 1 week improved VO2peak by as much as 1_mL/kg/min, or 3.8%. Even such a seemingly modest increase in a key measure of cardiorespiratory fitness would be expected to be strongly associated with significant health benefits if maintained long-term.3 Analysis of the UK Biobank data from 71 893 adults suggested that moderate amounts of vigorous physical activity for just 15_min daily confer a 16%–40% lower mortality risk.41 Notably, significant time commitment and effort are required to achieve increases in exercise capacity through conventional training regimes. For example, a seminal study in moderately trained male subjects showed that high-intensity aerobic interval training performed three times per week for 8 weeks was required to increase VO2max by 5.5%–7.2%, while other exercise protocols, including long slow distance running and lactate threshold training, followed for the same time period of 8 weeks, had lesser or no effect on measures of cardiorespiratory fitness.42 Other studies reported that high-intensity interval training in untrained lean and obese type 2 diabetic individuals for at least 5 weeks was required to increase peak oxygen consumption by 8%–15%.43,44

Our findings complement data obtained in clinical and experimental animal studies which support the hypothesis that vagal parasympathetic activity determines an individual’s ability to exercise. Analysis of HRR profiles after peak exercise in 1293 participants demonstrated that vagal autonomic dysfunction is strongly associated with reduced exercise capacity.9 In experimental animal studies, it was shown that inhibition of vagal activity reduced exercise capacity, while selective stimulation of vagal neurons increased exercise tolerance and this effect was associated with enhanced cardiac contractile response to sympathetic stimulation.9 Direct stimulation of vagal neurons was also found to maintain cardiac function and exercise capacity in an experimental model of heart failure.45 It has been suggested that parasympathetic activity modulates myocardial beta-adrenoceptor signalling and optimizes the responsiveness of the heart to sympathetic stimulation.7 In other words, vagal activity is required for the sympathetic nervous system to increase cardiac output sufficiently to support the metabolic demands of exercise. We hypothesize that the functional interactions between sympathetic and parasympathetic cardiac control are modulated by tVNS, leading to the improvements in measures of cardiorespiratory fitness observed in this study.

Results of HRV analysis are generally in line with previously reported effects of tVNS on HRV measures.15,46 The observed effects of tVNS on resting heart rate are consistent with known effects of vagal afferent stimulation, which—unlike direct stimulation of efferent vagal cardiac innervation—is associated with increases in heart rate due to afferent modulation of autonomic central drive.47 Increases in heart rate could be expected with tVNS, as this mode of stimulation captures the afferent fibres of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. The effects of bilateral auricular tVNS on heart rate may also differ from those of unilateral stimulation, given the complexity of spatial and temporal processing of vagal afferent information,48 which may be significantly influenced by pathological conditions associated with autonomic dysfunction including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.49

Different modes of exercise training and autonomic neuromodulation can confer beneficial effects on other systems, including the immune system. For example, endurance and interval training have been shown to increase telomerase activity and telomere length in mononuclear cells in healthy, but previously inactive individuals.50 tVNS had been shown to trigger systemic release of cardioprotective factor(s) that reduced ischaemia/reperfusion injury when plasma dialysate from the participants receiving tVNS was applied to isolated perfused rat hearts with myocardial infarction.18 The cardioprotective factor(s) had been found to be released from the spleen in response to tVNS.18 In this study, we show that tVNS restrains the inflammatory response, an observation consistent with the reported effects of autonomic modulation/vagal stimulation in experimental models. Discrete optogenetic stimulation of vagal afferents was reported to increase activities of splenic, renal, and lumbar sympathetic nerves, demonstrating that vagal afferent stimulation can also lead to sympathetic activation.40 Electrical stimulation of cervical or abdominal vagal projections in laboratory models had been shown to reduce inflammation in arthritis51 and endotoxemia.52

Regular physical activity plays an important role in both the primary and secondary preventions of cardiovascular disease.2 There is evidence that patients with circulatory system disease may benefit from physical activity to a greater extent than healthy individuals.53 Maintaining a physically active lifestyle is beneficial through numerous multisystem mechanisms,54 (although in a small number of highly trained individuals, extreme endurance training over the years may result in adverse cardiac remodelling.55) The safety profile and the effects of tVNS shown in this study provide proof-of-concept data suggesting that non-invasive autonomic neuromodulation can offer an adjunct approach to improve exercise tolerance. In particular, the growing population of older individuals with heart failure and/or coronary artery disease may benefit from this treatment.56 In a pilot sham-controlled, double-blind, parallel group, randomized clinical trial, 52 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction reported >90% adherence to sham-tVNS or tVNS treatment, applied for 1_h daily for 3 months.57 After 3 months, pre-specified secondary outcomes, including global longitudinal strain and blood tumor necrosis factor-α levels (as a measure of systemic inflammation) were favourably improved in patients randomized to active treatment, which correlated with better self-reported quality of life measures.57

The data from this trial require further validation in patient populations characterized by impaired exercise capacity. The generalizability of our findings is limited due to the single-centre volunteer study design. Additionally, the study was not designed to account for variations in baseline fitness, and volunteers were not engaged in structured exercise training programs before or during enrolment. Exploration of the well-documented sex-specific differences in exercise performance is also necessary.58 Further systematic studies in volunteers are required to determine the optimal tVNS stimulation parameters and duration of treatment.

In conclusion, the data obtained in this study suggest that autonomic neuromodulation by non-invasive auricular vagal stimulation offers a low-risk, accessible, non-pharmacologic, and titratable intervention that may help to deliver a personalized approach59 to improve exercise tolerance and promote cardiovascular health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the time and dedication of the volunteers who participated in this study. We thank Dr Eva Wozniak for her expert bioinformatical assistance.

Contributor Information

Gareth L Ackland, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Amour B U Patel, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Stuart Miller, Sports Medicine, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Ana Gutierrez del Arroyo, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Jeeveththaa Thirugnanasambanthar, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Jeuela I Ravindran, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Johannes Schroth, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

James Boot, Genome Centre, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Laura Caton, Genome Centre, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Chas A Mein, Genome Centre, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Tom E F Abbott, Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London, London, UK.

Alexander V Gourine, Centre for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Neuroscience, Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology, University College London, London, UK.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

A.V.G. is a founder of Afferent Medical Solutions, a UK-based bioelectronics medicine company exploring device-based neuromodulation for the treatment of hypertension. G.L.A. is named in a patent related to the use of peripheral neuromodulation—US20230355972: "Neuromodulation for the treatment of critical illness".

Data Availability

Data can be shared upon reasonable request under a data use agreement. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author at g.ackland@qmul.ac.uk and should receive a response within 2 weeks.

Funding

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (RG/19/5/34463). G.L.A. was supported by British Oxygen Company research chair grant from the Royal College of Anaesthetists, administered by the National Institute for Academic Anaesthesia (G.L.A.) and UK National Institute for Healthcare Research CLRN Portfolio. G.L.A. is supported by the NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR300097).

Ethical Approval

Study protocol was approved by NHS Research Ethics (21/LO/0856).

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

The study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov on 18 October 2022 (NCT05619107).

References

- 1. Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet Lond Engl 2012;380:294–305. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valenzuela PL, Ruilope LM, Santos-Lozano A, Wilhelm M, Kränkel N, Fiuza-Luces C, et al. Exercise benefits in cardiovascular diseases: from mechanisms to clinical implementation. Eur Heart J 2023;44:1874–89. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, Jaber W. Association of cardiorespiratory fitness with long-term mortality among adults undergoing exercise treadmill testing. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e183605. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blodgett JM, Ahmadi MN, Atkin AJ, Chastin S, Chan H-W, Suorsa K, et al. Device-measured physical activity and cardiometabolic health: the prospective physical activity, sitting, and sleep (ProPASS) consortium. Eur Heart J 2024;45:458–71. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380:258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shoemaker JK, Gros R. A century of exercise physiology: key concepts in neural control of the circulation. Eur J Appl Physiol 2024;124:1323–36. 10.1007/s00421-024-05451-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gourine AV, Ackland GL. Cardiac vagus and exercise. Physiol Bethesda 2019;34:71–80. 10.1152/physiol.00041.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korsak A, Kellett DO, Aziz Q, Anderson C, D’Souza A, Tinker A, et al. Immediate and sustained increases in the activity of vagal preganglionic neurons during exercise and after exercise training. Cardiovasc Res 2023;119:2329–41. 10.1093/cvr/cvad115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Machhada A, Trapp S, Marina N, Stephens RCM, Whittle J, Lythgoe MF, et al. Vagal determinants of exercise capacity. Nat Commun 2017;8:15097. 10.1038/ncomms15097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Letnes JM, Berglund I, Johnson KE, Dalen H, Nes BM, Lydersen S, et al. Effect of 5 years of exercise training on the cardiovascular risk profile of older adults: the generation 100 randomized trial. Eur Heart J 2022;43:2065–75. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1351–7. 10.1056/NEJM199910283411804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jouven X, Empana J-P, Schwartz PJ, Desnos M, Courbon D, Ducimetière P. Heart-rate profile during exercise as a predictor of sudden death. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1951–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa043012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tracey KJ. Reflexes in immunity. Cell 2016;164:343–4. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Badran BW, Dowdle LT, Mithoefer OJ, LaBate NT, Coatsworth J, Brown JC, et al. Neurophysiologic effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) via electrical stimulation of the tragus: a concurrent taVNS/fMRI study and review. Brain Stimul 2018;11:492–500. 10.1016/j.brs.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clancy JA, Mary DA, Witte KK, Greenwood JP, Deuchars SA, Deuchars J. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in healthy humans reduces sympathetic nerve activity. Brain Stimulat 2014;7:871–7. 10.1016/j.brs.2014.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frangos E, Ellrich J, Komisaruk BR. Non-invasive access to the vagus nerve central projections via electrical stimulation of the external ear: fMRI evidence in humans. Brain Stimulat 2015;8:624–36. 10.1016/j.brs.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Couck M, Cserjesi R, Caers R, Zijlstra WP, Widjaja D, Wolf N, et al. Effects of short and prolonged transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on heart rate variability in healthy subjects. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin 2017;203:88–96. 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lieder HR, Paket U, Skyschally A, Rink AD, Baars T, Neuhäuser M, et al. Vago-splenic signal transduction of cardioprotection in humans. Eur Heart J 2024;45:3164–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aranow C, Atish-Fregoso Y, Lesser M, Mackay M, Anderson E, Chavan S, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces pain and fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:203–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gold MR, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Hauptman PJ, Borggrefe M, Kubo SH, Lieberman RA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of heart failure: the INOVATE-HF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:149–58. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dixon JR Jr. The international conference on harmonization good clinical practice guideline. Qual Assur San Diego Calif 1998;6:65–74. 10.1080/105294199277860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mills EJ, Chan A-W, Wu P, Vail A, Guyatt GH, Altman DG. Design, analysis, and presentation of crossover trials. Trials 2009;10:27. 10.1186/1745-6215-10-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guazzi M, Arena R, Halle M, Piepoli MF, Myers J, Lavie CJ. 2016 focused update: clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Circulation 2016;133:e694–711. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hays SA, Rennaker RL, Kilgard MP. Targeting plasticity with vagus nerve stimulation to treat neurological disease. Prog Brain Res 2013;207:275–99. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63327-9.00010-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwong PWH, Ng GYF, Chung RCK, Ng SSM. Bilateral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation improves lower-limb motor function in subjects with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e007341. 10.1161/JAHA.117.007341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farmer AD, Strzelczyk A, Finisguerra A, Gourine AV, Gharabaghi A, Hasan A, et al. International consensus based review and recommendations for minimum reporting standards in research on transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (version 2020). Front Hum Neurosci 2020;14:568051. 10.3389/fnhum.2020.568051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel ABU, Weber V, Gourine AV, Ackland GL. The potential for autonomic neuromodulation to reduce perioperative complications and pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2022;128:135–49. 10.1016/j.bja.2021.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 1996;93:1043–65. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burr RL, Cowan MJ. Autoregressive spectral models of heart rate variability: practical issues. J Electrocardiol 1992;25:224–33. 10.1016/0022-0736(92)90108-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taylor JA, Carr DL, Myers CW, Eckberg DL. Mechanisms underlying very-low-frequency RR-interval oscillations in humans. Circulation 1998;98:547–55. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.6.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guzzetti S, La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Maestri R, Borroni E, Porta A, et al. Different spectral components of 24 h heart rate variability are related to different modes of death in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2005;26:357–62. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldstein DS, Bentho O, Park M-Y, Sharabi Y. LF power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp Physiol 2011;96:1255–61. 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.056259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 1986;59:178–93. 10.1161/01.RES.59.2.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Müller S, Kröger C, Schultze JL, Aschenbrenner AC. Whole blood stimulation as a tool for studying the human immune system. Eur J Immunol 2024;54:2350519. 10.1002/eji.202350519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higgins J, Eldridge S, Li T. Including variants on randomized trials https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-23 (16 July 2024, date last accessed)

- 37. Takken T, Mylius CF, Paap D, Broeders W, Hulzebos HJ, Van Brussel M, et al. Reference values for cardiopulmonary exercise testing in healthy subjects—an updated systematic review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2019;17:413–26. 10.1080/14779072.2019.1627874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Jonge WJ, van der Zanden EP, The FO, Bijlsma MF, Westerloo DJ, van Bennink RJ, et al. Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 2005;6:844–51. 10.1038/ni1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tamari M, Del Bel KL, Ver Heul AM, Zamidar L, Orimo K, Hoshi M, et al. Sensory neurons promote immune homeostasis in the lung. Cell 2024;187:44–61.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanaka S, Abe C, Abbott SBG, Zheng S, Yamaoka Y, Lipsey JE, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation activates two distinct neuroimmune circuits converging in the spleen to protect mice from kidney injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2021758118. 10.1073/pnas.2021758118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ahmadi MN, Clare PJ, Katzmarzyk PT, del Pozo Cruz B, Lee IM, Stamatakis E. Vigorous physical activity, incident heart disease, and cancer: how little is enough? Eur Heart J 2022;43:4801–14. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Helgerud J, Høydal K, Wang E, Karlsen T, Berg P, Bjerkaas M, et al. Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2max more than moderate training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:665–71. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180304570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hostrup M, Lemminger AK, Stocks B, Gonzalez-Franquesa A, Larsen JK, Quesada JP, et al. High-intensity interval training remodels the proteome and acetylome of human skeletal muscle. eLife 2022;11:e69802. 10.7554/eLife.69802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Larsen JK, Kruse R, Sahebekhtiari N, Moreno-Justicia R, Gomez Jorba G, Petersen MH, et al. High-throughput proteomics uncovers exercise training and type 2 diabetes–induced changes in human white adipose tissue. Sci Adv 2023;9:eadi7548. 10.1126/sciadv.adi7548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Machhada A, Hosford PS, Dyson A, Ackland GL, Mastitskaya S, Gourine AV. Optogenetic stimulation of vagal efferent activity preserves left ventricular function in experimental heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2020;5:799–810. 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bretherton B, Atkinson L, Murray A, Clancy J, Deuchars S, Deuchars J. Effects of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in individuals aged 55 years or above: potential benefits of daily stimulation. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:4836–57. 10.18632/aging.102074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ardell JL, Nier H, Hammer M, Southerland EM, Ardell CL, Beaumont E, et al. Defining the neural fulcrum for chronic vagus nerve stimulation: implications for integrated cardiac control. J Physiol 2017;595:6887–903. 10.1113/JP274678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shaffer C, Barrett LF, Quigley KS. Signal processing in the vagus nerve: hypotheses based on new genetic and anatomical evidence. Biol Psychol 2023;182:108626. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2023.108626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stavrakis S, Chakraborty P, Farhat K, Whyte S, Morris L, Abideen Asad ZU, et al. Noninvasive Vagus nerve stimulation in postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2024;10:346–55. 10.1016/j.jacep.2023.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Werner CM, Hecksteden A, Morsch A, Zundler J, Wegmann M, Kratzsch J, et al. Differential effects of endurance, interval, and resistance training on telomerase activity and telomere length in a randomized, controlled study. Eur Heart J 2019;40:34–46. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bassi GS, Dias DPM, Franchin M, Talbot J, Reis DG, Menezes GB, et al. Modulation of experimental arthritis by vagal sensory and central brain stimulation. Brain Behav Immun 2017;64:330–43. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Komegae EN, Farmer DGS, Brooks VL, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM, Martelli D. Vagal afferent activation suppresses systemic inflammation via the splanchnic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun 2018;73:441–9. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jeong S-W, Kim S-H, Kang S-H, Kim H-J, Yoon C-H, Youn T-J, et al. Mortality reduction with physical activity in patients with and without cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3547–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dempsey PC, Rowlands AV, Strain T, Zaccardi F, Dawkins N, Razieh C, et al. Physical activity volume, intensity, and incident cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43:4789–800. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sharma S, Merghani A, Mont L. Exercise and the heart: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1445–53. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pavasini R, Biscaglia S, Kunadian V, Hakeem A, Campo G. Coronary artery disease management in older adults: revascularization and exercise training. Eur Heart J 2024;45:2811–23. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stavrakis S, Elkholey K, Morris L, Niewiadomska M, Asad ZUA, Humphrey MB. Neuromodulation of inflammation to treat heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e023582. 10.1161/JAHA.121.023582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Santisteban KJ, Lovering AT, Halliwill JR, Minson CT. Sex differences in VO2max and the impact on endurance-exercise performance. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:4946. 10.3390/ijerph19094946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zubin Maslov P, Schulman A, Lavie CJ, Narula J. Personalized exercise dose prescription. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2346–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be shared upon reasonable request under a data use agreement. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author at g.ackland@qmul.ac.uk and should receive a response within 2 weeks.