Abstract

Introduction

Mobility limitation is common and often results from neurological and musculoskeletal health conditions, ageing and/or physical inactivity. In consultation with consumers, clinicians and policymakers, we have developed two affordable and scalable intervention packages designed to enhance physical activity for adults with self-reported mobility limitations. Both are based on behaviour change theories and involve tailored advice from physiotherapists.

Methods and analysis

This pragmatic hybrid effectiveness-implementation type 1 randomised control trial (n=600) will be undertaken among adults with self-reported mobility limitations. It aims to estimate the effects on physical activity of: (1) an enhanced 6-month intervention package (one face-to-face physiotherapy assessment, tailored physical activity plan, physical activity phone coaching from a physiotherapist, informational/motivational resources and activity monitors) compared with a less intensive 6-month intervention package (single session of tailored phone advice from a physiotherapist, tailored physical activity plan, unidirectional text messages, informational/motivational resources); (2) the enhanced intervention package compared with no intervention (6-month waiting list control group); and (3) the less intensive intervention package compared with no intervention (waiting list control group). The primary outcome will be average steps per day, measured with the StepWatch Activity Monitor over a 1-week period, 6 months after randomisation. Secondary outcomes include other physical activity measures, measures of health and functioning, individualised mobility goal attainment, mental well-being, quality of life, rate of falls, health utilisation and intervention evaluation. The hybrid effectiveness-implementation design (type 1) will be used to enable the collection of secondary implementation outcomes at the same time as the primary effectiveness outcome. An economic analysis will estimate the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of the interventions compared with no intervention and to each other.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained by Sydney Local Health District, Royal Prince Alfred Zone. Dissemination will be via publications, conferences, newsletters, talks and meetings with health managers.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618001983291.

Keywords: clinical trials, rehabilitation medicine, geriatric medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Pragmatic evaluation of a scalable person-centred intervention.

Theory-based intervention informed by consumers, clinicians and policymakers.

Six-month study time frame will not test long-term intervention impacts.

Staffing in the trial does not enable those who do not speak English to participate.

Recruitment is based on self-reported mobility limitation rather than a standardised measure.

Introduction

Disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions.1 Mobility limitation (ie, difficulty or inability to walk) is a particularly common2 and serious form of physical disability. It is primarily due to neurological and musculoskeletal health conditions, physiological ageing and inactivity-related deconditioning.3 Walking impairment or ‘dismobility’ is predictive of adverse health outcomes, including death.3 Widespread screening for walking problems has been suggested as an additional vital sign, and development and testing of interventions for people with walking difficulties has been highlighted as an urgent research priority.3

Walking is required for many daily activities, thus individuals with difficulty walking are often unable to perform daily activities and require care services. Mobility limitation is particularly common in older people and, as the population is ageing, the impact of mobility limitation is increasing. Interventions that are able to increase mobility and reduce service needs in people with mobility limitations is likely to yield benefits for individuals and financial benefits for societies. Mobility limitation also affects younger adults with chronic acquired or congenital musculoskeletal or neurological conditions, conditions which are becoming more common due to better survival from serious illnesses and injuries.4 Mobility impairment with onset earlier in life also has an important impact on population health due to the lasting nature of the impairment and significant impacts on productivity.5 6

Physical activity participation has enormous untapped potential as a cost-effective approach to enhancing physical and mental health in people of most ages, health conditions and physical abilities.7 A Lancet editorial7 calls for physical activity to be taken more seriously as a population health intervention, given the strong evidence of physical and mental health benefits and poor participation rates. As well as enhancing the prevention and management of chronic conditions, physical activity is now known to have survival benefits.8 For example, taking a greater number of steps per day was associated with lower all-cause mortality over a 10-year follow-up period (adjusted HR (AHR) for all-cause mortality 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90 to 0.98 per 1000 steps; p=0.004).9 In those who increased daily steps there was a substantial reduction in mortality risk after adjusting for baseline daily step count (AHR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.72; p=0.002).9

People with health conditions affecting mobility can obtain additional benefits from physical activity including better mobility, fewer falls and less risk of hospitalisation.10 Physical activity enhances mobility through improved aerobic capacity, muscle strength, balance and coordination.11 More demanding mobility tasks such as stair-climbing and walking longer distances require greater levels of physical functioning. If a person’s physical functioning is lower than that required for independent performance of a particular activity, that is, below the ‘disability threshold’, they will require assistance or aids. Greater physical functioning provides ‘reserve capacity’ which acts as a buffer to ensure that functioning remains above the disability threshold even in the face of deterioration from factors such as physiological ageing, illness or injury. Much of the deterioration in physical fitness and mobility commonly thought to be due to ageing/health conditions is actually due to inactivity and thus at least partly treatable and preventable.12 Trials have confirmed that physical activity can improve walking ability and prevent the onset of disability.13 For example the onset of mobility disability was prevented by a structured physical activity programme in people aged 70 to 89 who had some physical limitation at baseline.13

Unfortunately, people with mobility limitations are less active than the general population.14 For example, 65% of Australians regularly participate in physical activities for recreation, exercise or sport, but only 24% of Australians with disabilities participate in such activities.15 Although widespread provision of supervised structured exercise programmes would be likely to significantly lessen mobility impairment at a population level, such an approach is unlikely to be broadly implemented by public health systems given the size of the target population. Self-funding of such interventions is out of reach for many individuals. More flexible intervention approaches that focus on physical activity more broadly, facilitate attendance at existing programmes, include self-management approaches and incorporate technology are likely to be more scalable. These approaches therefore warrant investigation.

Regular physical activity participation requires motivation, capability and opportunity.16 Simply advising people to be more active is unlikely to safely enhance activity levels.17 Rather, advice needs to be specific, individualised, supported by a behaviour change framework and based on engagement with the person and their goals and priorities.18 Health coaching interventions that involve behaviour change techniques including goal-setting and are individually tailored are known to change behaviour in the general population.18–20 A recent systematic review21 found health coaching to improve physical activity levels in older people (standardised mean difference=0.29; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.39; p<0.001) and others have found motivational interviewing (a form of health coaching) to enhance physical activity in people with chronic conditions22 and in hip fracture survivors.23 These trials focussed on health conditions so did not cater specifically for people with impaired mobility. The impact of health coaching in this population is not known. Physical activity prescription in people with mobility limitations is complex so we hypothesise that tailored advice from physiotherapists will enhance activity levels.

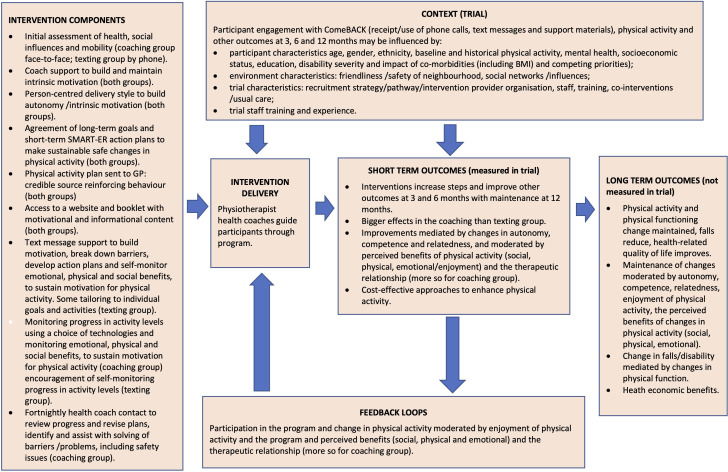

In consultation with consumers, clinicians and policymakers, our multidisciplinary investigator team developed two intervention packages based on behaviour change theories as outlined in the logic model (figure 1) and tables 1 and 2.16 24 25 Both interventions involve the development of a goal-based tailored physical activity plan (made in conjunction with a physiotherapist and sent to participants and their primary care physician (referred as a general practitioner (GP)) to reinforce physical activity participation), access to informational and motivational print and online resources and encouragement of use of activity monitors and suitable smartphone applications. We hypothesise that greater effects on measured physical activity levels will be evident from an enhanced intervention package (that also includes a face-to-face assessment and ongoing phone-based physical activity phone coaching both provided by a physiotherapist) compared with a less intensive intervention package (that includes a single phone call from a physiotherapist and text messages). We further hypothesise that both these interventions will have greater impacts on physical activity levels than no intervention.

Figure 1.

Logic model for the ComeBACK intervention. BMI, body mass index; GP, general practitioner.

Table 1.

Trial and intervention overview and reasoning by population, interventions, control and outcome

| Component | Rationale | Behavioural aspect addressed* |

| Population | ||

| Adults with mobility limitation due to any reason, able to leave the house without assistance |

|

n/a |

| Recruited from clinical sites and the community across four states |

|

n/a |

| Group 1: Coaching to ComeBACK package | ||

| One face-to-face assessment by physiotherapist |

|

Expert assessment of capability to suggest appropriate opportunities. Establishing /building motivation. |

| Patient-centred health coaching, incorporating behaviour change strategies including goal-setting and motivational interviewing |

|

Ongoing expert assessment of capability to suggest appropriate opportunities. Encouragement of capability enhancement. Feedback to assist with ongoing motivation. |

| Activity monitor or pedometer if desired |

|

Feedback to assist with ongoing motivation. |

| Tailored use of applications to encourage physical activity |

|

Feedback and rewards to assist with ongoing motivation. |

| Paper-based and online resources to support behaviour change |

|

Case studies and information to assist with capability and motivation. |

| Tailored physical activity plan developed and shared with GP |

|

Increased motivation. |

| Group 2: Texting to ComeBACK | ||

| Single session of tailored advice over the phone from a physiotherapist |

|

Expert assessment of capability to suggest appropriate opportunities. |

| Paper-based and online resources to support behaviour change |

|

Case studies and information to assist with capability and motivation. |

| Text messages |

|

Assist with motivation and problem-solving (capability). |

| Tailored physical activity plan developed and shared with GP |

|

Increased motivation. |

| Group 3: Texting to ComeBACK Later | ||

| No intervention for 6 months |

|

|

| Receipt of less intensive intervention after 6 months |

|

As above |

| Outcome | ||

| Physical activity |

|

n/a |

*Primarily using the COM-B (Capability Opportunity Motivation –>Behaviour) system16 for understanding behaviour change. Includes capability (an individual’s psychological and physical capacity for physical activity including knowledge and skills), opportunity (factors outside the individual that enable or prompt behaviour) and motivation (brain processes that energise and direct behaviour, that is, goals, decision-making, habits, emotional responding). This model acknowledges the role of individual action to change behaviours within a broader social context.

GP, general practitioner.

Table 2.

Intervention description of the ComeBACK randomised controlled trial using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist

| Intervention description using the TIDieR checklist | ||

| Brief name | Intervention group 1 | Intervention groups 2 and 3 |

| Coaching to ComeBACK | Texting to ComeBACK and texting to ComeBACK Later* | |

| Why | Over 1 million Australians currently require assistance to, or are unable to, walk about their homes. The impact of mobility limitation is increasing due to population ageing. Physical activity participation has enormous untapped potential as a cost-effective approach to enhancing health in people of most ages, health conditions and physical abilities, however most people with mobility limitations are insufficiently active for health benefits. Remote interventions such as telephone health coaching and text-message support to encourage physical activity are scalable interventions which can be tailored to match the individual’s capacity and preferences. Physical activity prescription for people with mobility limitations is complex as they face additional barriers to physical activity participation, thus interventions delivered by health professionals such as physiotherapists are needed. A theoretical basis combining COM-B (Capability Opportunity Motivation –>Behaviour) model of behaviour change, Self Determination Theory and Social Cognitive Theory informs the choice of intervention components and underpins all participant materials. | |

| What procedures |

|

|

| What materials† |

|

|

| Who provided |

|

|

| How |

|

|

| Where |

|

|

| When and how much |

|

|

| Tailoring | The individually-tailored, person-centred approach will determine each person’s physical, cognitive, affective, environmental and social barriers and develop physical activity recommendations (including adaptations and/or assistance to overcome specific barriers) for each individual. Both interventions will link or recommend participants to existing community programmes, with a focus on identifying activities that participants will enjoy.40 Suitable options may include attendance at a group programme, such as those indexed on the Active and Healthy website (https://www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au/), and/or participation in sporting opportunities that cater for people with impaired mobility. Both interventions will also encourage reduced sedentary and inactive time by spending more time standing and walking and increased use of active transport (ie, walking, using public transport) and/or undertaking a home-based exercise programme. | |

*Texting to ComeBACK Later group will receive the same intervention as the Texting to ComeBACK group with a 6-month delay.

†Study resources (booklet, physical activity plan, website resources) will be made publicly available after the trial is completed.

Methods and analysis

Overview

This pragmatic hybrid effectiveness-implementation design (type 1) superiority trial (n=600) will use 1:1 concealed online randomisation to allocate adults with self-reported mobility limitations to a 6-month enhanced intervention, a 6-month less intensive intervention or a waiting list control group (who will receive the less intensive intervention after 6 months). Between-group comparisons will be undertaken at 6 months (all groups) and at 12 months (comparing two intervention groups).

The study primarily aims to establish the effects of the interventions, compared with each other and to control, on objectively-measured physical activity at 6 months (StepWatch, steps per day). Secondary outcomes include other physical activity measures, measures of health and functioning, individualised mobility goal attainment, mental well-being, quality of life, rate of falls, health utilisation and intervention evaluation. Secondary analyses will explore differential effects on the basis of recruitment source (health professional referral vs community advertising), assess implementation outcomes and establish the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility.

The trial is more pragmatic than explanatory in that it uses recruitment and intervention strategies relevant to the ‘real-word’ and is intended to help support a decision on whether such interventions should be delivered. A more explanatory trial would be undertaken in an idealised setting, to give the intervention its best chance to demonstrate a beneficial effect.26 A hybrid effectiveness-implementation design (type 1)27 will be used to collect implementation outcomes at the same time as effectiveness outcomes. A nested process evaluation will use both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore uptake by participants and acceptability of the intervention (to participants, health coaches and other stakeholders). The protocol for the process evaluation will be described elsewhere. The PRACTIS guide28 to implementation and scale-up of physical activity interventions was used to ensure that the interventions (and study recruitment methods) were as potentially scalable in future as possible. Future scale-up of the interventions, if found to be effective, will be guided by the model developed by Milat et al,29 along with the implementation outcomes and other aspects of the process evaluation. An economic analysis, which will be conducted alongside the trial, will aim to establish the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of the interventions compared with no intervention and to each other to assist funders of preventive health interventions to assess the value of such an approach for future investments. Table 1 shows the reasons for choice of different components, table 2 overviews the intervention in Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) format and figure 1 shows the overall logic and broader context for the trial. The first participant was recruited on 13 February 2019 and at the time of submission of this manuscript 156 participants had been randomised.

The primary comparisons will assess the effect on objectively measured physical activity at 6 months of the;

Enhanced intervention package (Coaching to ComeBACK group: one face-to-face assessment from a physiotherapist, tailored physical activity plan sent to participant and GP, physical activity phone coaching from a physiotherapist, activity monitors and/or applications, booklet and access to online resources) compared with a less intensive intervention package (Texting to ComeBACK group: single session of tailored advice by phone from a physiotherapist with health coaching training, tailored physical activity plan sent to participant and GP, unidirectional text messages, booklet and access to online resources);

The enhanced intervention package (Coaching to ComeBACK group) compared with no intervention (Texting to ComeBACK Later waiting list control group);

The less intensive intervention package (Texting to ComeBACK group) compared with no intervention (Texting to ComeBACK Later waiting list control group).

Participants

The trial will be conducted across four Australian states with recruitment through health services in hospital departments and the general community through community organisations as well as traditional and social media advertisements and stories. Participants with a range of health conditions who report difficulty or inability to walk 800 m30 will be recruited. The process evaluation will explore differences in feasibility and efficiency of recruitment in each of the settings to inform future implementation strategies.

The trial will involve consenting adults (18+ years) who are: living in the community (as opposed to residential care); have a mobility limitation (self-reported difficulty or inability to walk 800 m) but are able to leave their home without physical assistance from another person (but may use a walking aid); are judged by recruitment staff to have sufficient hearing and English language skills for a phone-based intervention. Trial participants are likely to be affected by one or more common and/or burdensome conditions such as, but not limited to, osteoarthritis, lower limb fractures, lower limb amputations, stroke, brain injury, respiratory conditions and obesity. The trial will exclude adults who are: permanent residents of residential aged care facilities; have the following medical conditions: delirium, acute medical illnesses, severe psychiatric disorders, rapidly progressive neurological diseases; have a major cognitive impairment (a diagnosis of dementia or a Memory Impairment Screen score of less than 5); are currently undertaking 150 min or more of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week (based on self-report); full-time wheelchair user; unable to wear a StepWatch Activity Monitor; not a regular user of a mobile phone (look at phone less than once per week); or have no Internet access.

Randomisation

Each participant will be randomised to one of the three groups after completion of baseline assessments. The trial will use a centralised web-based randomisation system using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). The randomisation schedule was developed by a researcher not involved in recruitment, outcome measurement or intervention delivery. This process will ensure concealment of allocation to groups and an auditable process. Randomisation to groups will be stratified by whether participants were recruited from the general community (via advertising, etc) or from health services.

Assessments

Assessments will occur prior to randomisation and at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation. The matchbox-sized StepWatch Activity Monitors used to objectively measure physical activity (primary outcome 6 month, secondary outcome 12 month) will be mailed to participants with reply-paid envelopes and clear instructions for use and will be worn at the ankle during waking hours for periods of seven consecutive days. Telephone calls will be made to participants who have not returned the devices and to those who require assistance wearing the device. Questionnaires will be administered online by participants or, if preferred mailed, or by phone by a research assistant unaware of intervention group allocation. Monthly online or paper calendars, with phone follow-up where necessary, will be used by participants to report falls and health and community service usage over the 12-month trial period to enable cost collation for the economic analyses. Where possible, data for all outcomes will be collected for all participants including those who cease participation in the interventions, unless the participant wishes to withdraw from the study. The primary outcome will be collected in a blinded fashion. StepWatch Activity Monitor data will be processed and analysed by staff unaware of intervention group allocation. All baseline measurements will be undertaken prior to group allocation. Due to the nature of the intervention being tested, full blinding of participants to intervention group allocation will not be possible. All the reassessment questionnaires will however be undertaken by researchers blinded to group allocation. Table 3 overviews the trial outcomes and measurement time points.

Table 3.

List of measures collected at BA, 3A, 6A and 12A for all study participants

| Information collected for all participants | BA | 3A | 6A | 12A | O |

| Socio-demographics. Age, gender, education, occupation, country of birth, language, living arrangements, health condition, agency support | Y | N | N | N | N |

| General health and function | |||||

| Functional comorbidity Index | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Technology exposure | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Mobility aids | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Body mass index | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Pain-related questions | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Self-reported fear of falling and balance level | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Late Life lower limb extremity Function and Disability Instrument33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Individualised mobility Goal Attainment Scale34 | Y | N | Y | Y | S |

| Quality of life | |||||

| The EQ-5D-5L36 | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Mental well-being | |||||

| Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Physical activity | |||||

| Average steps per days measured over a 1-week period using a StepWatch Activity Monitor | Y | N | Y | Y | P |

| Cadence and activity intensity levels using a StepWatch Activity Monitor | Y | N | Y | Y | S |

| The Incidental and Planned Exercise Questionnaire (IPEQ) | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Global Perceived Change scales on physical activity and walking | N | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Attitudes to physical activity | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Experiences of physical activity | N | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Falls and health utilisation | |||||

| Falls and fall-related injuries (monthly diaries for 12 months)50 | S | ||||

| Use of health services (monthly diaries for 12 months)50 | S | ||||

| Medication use | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Intervention evaluations | |||||

| Impressions of programme | Y# | Y% | S | ||

| Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) | Y# | Y% | S | ||

| Work Alliance Inventory-Short Revised Participant (WAI-SR) | Y# | Y% | S | ||

| Work Alliance Inventory-Short Revised Therapist (WAI-SRT) | Y# | Y% | S |

Y, YES; N, NO; BA, baseline assessment; 3A, 3 months assessment; 6A, 6 months assessment; 12A, 12-month assessment; O, outcome measure; S, secondary; P, primary; #, Group 1 and 2; %, Group 3.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the trial is physical activity, measured as average steps per day over a 1-week period at 6 months post baseline with the StepWatch Activity Monitor. This device was chosen as prior research by the present authors31 found it to be the most accurate device for step measurement in people with mobility impairment with average 98% (SD 12%) agreement with investigator-observed steps over a 6 min period as opposed to 17% (SD 19%) for the more commonly-used Actigraph device. The StepWatch Activity Monitor is simple to use, can be mailed to participants and does not give feedback to the wearer.

Secondary outcomes will be measured at 3, 6 and 12 months post baseline. Measures undertaken at 12 months will compare the two intervention groups and assess physical activity maintenance in the intervention groups and uptake in the waiting list control group (Texting to ComeBACK Later Group). Secondary outcomes include other physical activity measures (self-reported physical activity using the Incidental and Planned Exercise Questionnaire,32 cadence, activity intensity (6 and 12 months only) and average steps per day (12 months only) from the StepWatch Activity Monitor, global perceived change scores for physical activity and walking, attitudes to and experience of physical activity), pain (study specific questions), lower limb function and disability (Late Life Function and Disability Instrument,33 fear of falling and self-reported balance (5-point scales), individualised mobility goal attainment (Goal Attainment Scale34 at 6 and 12 months), mental well-being (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale,35 quality of life (EuroQol 5D-5L),36 body mass index, use of mobility aids, rate of falls and health utilisation (monitored using monthly calendars over 12 months) and measures evaluating impressions (study specific) and enjoyment (Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale)37 of the interventions and the therapeutic alliance between health coaches and participants (Working Alliance Inventory).38 The EuroQol 5D-5L will also be used to enable calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for the economic analyses.

Other measures Intervention costs and health and community service utilisation, as collected by monthly calendars, will be recorded for all participants and used as part of the economic evaluation. The experiences and attitudes of stakeholders, including participants, health coaches, clinicians and health service managers will be explored via semi-structured interviews and focus groups in order to inform future development and implementation of the ComeBACK interventions.

Adverse events will be defined as an unwanted and usually harmful outcome (eg, exercise-related falls, musculoskeletal injury, angina, shortness of breath or cardiovascular event). The event may or may not be related to the intervention, but it occurs while the person is participating in the intervention phase of the trial, that is, while they are doing mobility or physical activities. A minor adverse event is defined as an incident that results in no injury or minor injury. For example, a fall where the person sustains a small cut or bruise that requires none or minor medical intervention. A serious adverse event is defined as an incident that results in death, serious injury or hospitalisation. Adverse events will be monitored by records kept by participants and interviews at each follow-up period. Participants will also be asked to notify study staff immediately of any serious adverse events. Any adverse event occurring during the assessment and intervention process will be reported back to authors Hassett and Sherrington. It will then be decided if this is a recognised or unintended event relating to the study protocol. Unintended events will be reported to the three-person independent Data Monitoring Committee that has been established for this trial and comprises one medical professional and two allied health professionals experienced in the care of people with mobility limitations. Unintended events will also be reported to the approving Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The research team will review the event and determine whether it is person specific or whether there is a potential for this to occur to other participants and therefore consideration would be given as to appropriateness of continuing the research. Participants may experience muscle soreness at the start of the physical activity programme. This will be minimised by advice to increase activity levels gradually and to seek professional advice if soreness lasts for more than 3 days or interferes with daily activities.

Interventions

Intervention design was undertaken by our multidisciplinary author team guided by formal (qualitative pilot work) and informal input from consumers in the target population as well as consultations with clinicians, health service managers, population health service providers and health policymakers. The COM-B (Capability Opportunity Motivation –>Behaviour) model of behaviour change16 was used to guide the intervention design, with self-determination theory24 and social cognitive theory25 further underpinning the motivational component. Table 1 overviews the aspects of the COM-B addressed by each aspect of the intervention packages. Table 2 provides more detail on the interventions using the TIDieR format.39 The interventions are as follows.

Group 1: coaching to ComeBACK

Participants randomised to this group will be offered the following six intervention components;

A single face-to-face 1-hour assessment of mobility status, safety issues, medical, social and environmental influences on mobility, will be undertaken during a home visit by a physiotherapist (employed locally). Where a home visit is not possible, a videoconference will be conducted as an alternative. At the end of the assessment, a phone or videoconference call will be made to the health coach with both physiotherapist and the participant present to introduce and handover to the health coach and discuss any particular issues.

Phone-based health coaching will be delivered by trained physiotherapists through a centralised service. The initial session will include development of a tailored plan to improve physical activity through participation in suitable activities in negotiation with the participant and their carers (where appropriate). The choice of physical activity will be guided by personal preference, logistics, physical abilities and evidence of effectiveness of different intervention options. The coach will liaise with relevant treating health professionals to identify contraindications or precautions to exercise and ensure other causes of mobility limitation are optimally managed. Coaching sessions will be delivered at a tailored frequency of approximately every 2 weeks over a 6-month period and will take an average of 20 to 30 min each session. The coaching will incorporate behaviour change strategies including motivational interviewing (to explore and enhance reasons for being active (importance) and confidence to make changes, as well as to explore social influences on activity) goal-setting, problem-solving, building social support and experiential learning. The individually-tailored, person-centred approach will determine each person’s physical, cognitive, affective, environmental and social barriers and facilitators to physical activity and develop physical activity recommendations (including adaptations and/or assistance to overcome specific barriers) for each individual. The health coach will link participants to existing community programmes if desired, with a focus on identifying activities that participants will enjoy.40 Suitable options may include attendance at a group programme, such as those indexed on the Active and Healthy website (www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au) and/or participation in sporting opportunities that cater for people with impaired mobility. The coaching will also encourage reduced sedentary and inactive time by spending more time standing and walking or undertaking a home-based exercise programme, as well as increased use of active transport (ie, walking, using public transport). Staff have extensive experience in the management of people with walking limitations, have undertaken courses in health coaching and received 2 days of additional training in using behaviour change science and self-determination theory to guide intervention from author Greaves.

Activity monitors and GPS-based tablet/smartphone applications. Participants will be offered an Internet-connected activity monitor (such as the Fitbit) or a simple pedometer, if preferred, as pedometers are known to enhance physical activity through measurement and behavioural reinforcement.41

Physical activity plan developed jointly as outlined above will be shared with the participant’s GP with his/her consent soon after it is developed.

Paper-based booklet on physical activity, safe mobility and behaviour change, that is, study-specific, evidence-based and theoretically informed (by incorporating messaging and images that are consistent with self-determination theory (promoting autonomy, competence and relatedness for walking behaviour) and social cognitive theory (supporting self-regulation and identifying/reinforcing the perceived benefits (social, physical, emotional/affective).

Closed study website with three components: (1) why be active (incorporating motivational components consistent with self-determination theory); (2) how to be active (links to resources); and (3) how others do it (video case studies using modelling of successful peer behaviour as per Social Cognitive Theory).

Group 2: texting to ComeBACK

Participants randomised to this group will be offered the following five intervention components. The first two intervention components are unique to this group and the following three interventions are the same as Group 1.

Single session of tailored advice provided by phone by a physiotherapist. This call will last 50 to 60 min, will be informed by the baseline assessment results and provide advice about appropriate physical activity opportunities for the person’s interests and level of mobility. A follow-up email will be sent to summarise and reinforce key discussion points.

Text messages to encourage activity. Prescheduled unidirectional text messages with some tailoring and personalisation will commence at five times/week for the first month to provide motivational support (again using messages designed to be consistent with self-determination theory (promoting autonomy, competence and relatedness for walking behaviour) and social cognitive theory (supporting self-monitoring/self-regulation and identifying/reinforcing the perceived benefits (social, physical, emotional/affective)), planning support, problem-solving and maintenance support. Participants will then have the option of increasing intensity (daily messages) or decreasing intensity (three times/week) for the next 4 months prior to a gradual reduction in the frequency of messages. There is also an opt-out feature available at all times.

Physical activity plan developed jointly as outlined above and will be shared with the participant’s GP with their consent soon after it is developed.

Paper-based booklet that has study-specific information on physical activity, safe mobility and behaviour change that is evidence-based and theoretically informed (as outlined above).

Closed study website with three components: (1) why be active; (2) how to be active (links to resources including recommended activity monitors and physical activity applications); and (3) how others do it (video case studies using modelling of successful peer behaviour as per social cognitive theory).

Group 3: texting to ComeBACK later (waiting list control)

This group will not receive any intervention for the first 6 months of the trial but will be advised to continue usual activity levels and health service use. After 6 months, this group will receive the Texting to ComeBACK intervention package as outlined above.

Patient and public involvement

Consultations with consumers, clinicians and policymakers assisted in the design of intervention and study methods. This input was gained from (1) input from our multidisciplinary study team that includes health service managers and clinicians; (2) informal discussions with health service managers, health professionals, health service users, community members and those delivering interventions in our previous trials,42–44 and (3) formal qualitative work involving participants in our previous trials45 46 and our systematic reviews of qualitative studies.47 48

The study protocol and choice of intervention and assessment tools (including the burden on participants) was further guided by feedback from consumers obtained as part of the endorsement of the trial by the Australia & New Zealand Musculoskeletal Clinical Trials Network (ANZMUSC). Study results will be disseminated to participants via email or paper letters.

Sample size

The trial’s sample size (n=600) will provide 90% power to detect between-group differences of 1000 steps per day assuming a SD of 3000 steps (estimated from our pilot data), a dropout rate of 20%, alpha of 0.0167 (to adjust for multiplicity due to three trial arms), and correlation between initial and final measures of 0.6 (from our pilot data). This calculation was undertaken in Stata 13 using the sampsi command. On the basis of previous work by the investigators and others, we consider between-group differences of this magnitude to be likely to result in significant health benefits because 1000 steps/day, assuming a cadence of 80 steps/min, would equate to an additional 15 min of walking/day, a dose associated with health benefits and reduced mortality even in those with cardiovascular disease.49

Statistical analysis

Analysis of covariance, conducted using a linear regression approach, will be used to assess the effect of group allocation on the continuously-scored primary and secondary outcomes after adjusting for baseline scores and source of recruitment. Point estimates and their 95% CIs will be used to interpret results. Given our interest in comparing the two interventions with each other and with the control condition, between-group differences with p values <0.0167 will be considered significant. Planned subgroup analyses will assess differential effects of the intervention based on the stratification variable of recruitment source, as well as for severity of mobility limitation and age. Secondary analyses using causal modelling will be conducted to establish intervention effects in people with greater adherence. Analyses will be preplanned, by intention-to-treat, conducted while masked to group allocation and undertaken after range checks. A detailed Statistical Analysis Plan will be developed and signed off by all investigators prior to analysis.

The economic evaluation will take the perspective of the health and community care funder. Healthcare costs, community service costs and intervention costs will be collected over the trial period. Using mean costs and mean health outcomes in each trial arm, the incremental costs per (1) additional person with increased physical activity of more than 1000 steps per day; and (2) QALY gained will be calculated; results will be plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane. Bootstrapping will be used to estimate a distribution around costs and health outcomes, and to calculate the CIs around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios. One-way sensitivity analysis will be conducted around key variables and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis will estimate uncertainty in all parameters. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve will be plotted to provide information about the probability that the intervention is cost-effective, given willingness to pay for each benefit gained. Modelled analyses will explore the longer-term cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval and local governance approvals have been obtained (Lead ethics committee: Sydney Local Health District, Royal Prince Alfred Zone (22/08/2018×18–0234). All amendment requests will be submitted to these committees. Written informed consent from all participants will be obtained by study staff prior to study enrolment (see sample consent form in online supplemental material). Participant confidentiality will be maintained at all times and all data will be stored securely. Dissemination will be via publications, conferences, newsletter articles, letters to participants, talks to healthcare professionals and consumers and meetings with health department and health service mangers. Intervention materials will be made freely available at the end of the trial. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommended criteria for authorship on publications will be followed. Professional writers will not be used. The full protocol, de-identified data and statistical code will be made available on reasonable request. All authors will have full access to de-identified study data.

bmjopen-2019-034696supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)

Discussion

This study will address a key evidence gap regarding realistic scalable ways to enhance physical ability in people with impaired mobility. The trial interventions are designed to be tailored yet scalable. The interventions are designed by health professionals and involve individualised health professional input, but have minimal face-to-face contact in an effort to minimise travel time, increase availability and enable greater efficiency. The use of a central centre to deliver the interventions is a model designed to be implemented if found to be effective. The inclusion of the lower intensity (text message) group aims to ascertain whether there is sufficient benefits from this less resource intensive model.

It would have been useful and interesting to measure performance outcomes such as mobility, balance and strength at 6 and 12 months, but the size of the trial, geographical spread of participants and budget constraints preclude this.

Trial results will provide direct information about the costs and benefits of the intervention approach compared with current practice to enable funders of preventive health interventions to decide whether such approaches are worth investing in as a population health intervention.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Leanne_Hassett, @AnneTiedemann1, @HinmanRana, @mariacrotty15, @Tammy_Hoffmann, @ColinGreaves1, @mabpinheiro, @siobhancwong, @cathiesherr

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study and preparation of the study protocol. This manuscript was drafted by author CS who oversees all aspects of the study. Author LH oversees the intervention aspects of the study and the Sydney sites. Author SO oversees data collection and integrity and privacy. Author MvdB oversees the South Australian sites. Authors RSH and NFT oversee the Victorian sites. Author TH overs the Queensland sites. Authors CS, RSH, MC, TH, LH, NFT, LH and AT were Chief Investigators on the Grant application. Authors AM, DT, KB, KH and MJ were Associate Investigators on the Grant application. Associate Investigator Herbert is not an author on this paper but will guide statistical analysis. Authors DT, MJ and AM are senior clinicians and/or policy leaders. Author MP will undertake the economic evaluation under guidance from author KH. Author CG guided the use of behaviour change theory in intervention design. Author AM will guide the use of the scale-up tool he developed. Authors SO, CK and ER are employed to work on the study. Authors CK and ER are the physiotherapists who deliver the health coaching interventions and assisted with the design of the interventions. Author SW is a PhD student who will lead the implementation/process evaluation (to be reported separately). We are grateful to study participants and to the patient advisors who helped shape the intervention.

Funding: This work is supported by a project grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP 1145739). Authors LH, AT, RSH and CS receive salary funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship.

Disclaimer: The funders have no role in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication, and will not have ultimate authority over any of these activities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.WHO Towards a common language for functioning disability and health. ICF, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AIHW Australia’s Welfare. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings SR, Studenski S, Ferrucci L. A diagnosis of dismobility--giving mobility clinical visibility: a Mobility Working Group recommendation. JAMA 2014;311:2061–2. 10.1001/jama.2014.3033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma VY, Chan L, Carruthers KJ. Incidence, prevalence, costs, and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the United States: stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95::986–995. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones E, Pike J, Marshall T, et al. Quantifying the relationship between increased disability and health care resource utilization, quality of life, work productivity, health care costs in patients with multiple sclerosis in the US. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:294. 10.1186/s12913-016-1532-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espahbodi S, Bassett P, Cavill C, et al. Fatigue contributes to work productivity impairment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: a cross-sectional UK study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:571–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das P, Horton R. Physical activity-time to take it seriously and regularly. Lancet 2016;388:1254–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Kamada M, et al. Association of step volume and intensity with all-cause mortality in older women. JAMA Intern Med 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0899. [Epub ahead of print: 29 May 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dwyer T, Pezic A, Sun C, et al. Objectively measured daily steps and subsequent long term all-cause mortality: the Tasped prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141274. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann TC, Maher CG, Briffa T, et al. Prescribing exercise interventions for patients with chronic conditions. CMAJ 2016;188:510–8. 10.1503/cmaj.150684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of sports medicine position stand. quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock RD, Carter S, Velloso CP, et al. An investigation into the relationship between age and physiological function in highly active older adults. J Physiol 2015;593:657–80. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the life study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:2387–96. 10.1001/jama.2014.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity--United States, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:407–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sports ABS. Physical recreation: a statistical overview. Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, White I, et al. Advising people to take more exercise is ineffective: a randomized controlled trial of physical activity promotion in primary care. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:808–15. 10.1093/ije/31.4.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards J, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, et al. Face-to-face interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:Cd010392. 10.1002/14651858.CD010392.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster C, Richards J, Thorogood M, et al. Remote and web 2.0 interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:Cd010395. 10.1002/14651858.CD010395.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011;11:119. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira JS, Sherrington C, Amorim AB, et al. What is the effect of health coaching on physical activity participation in people aged 60 years and over? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1425–32. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Halloran PD, Blackstock F, Shields N, et al. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in people with chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:1159–71. 10.1177/0269215514536210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Halloran PD, Shields N, Blackstock F, et al. Motivational interviewing increases physical activity and self-efficacy in people living in the community after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2016;30:1108–19. 10.1177/0269215515617814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147. 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koorts H, Eakin E, Estabrooks P, et al. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: the PRACTIS guide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:51. 10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milat AJ, Newson R, King L. Increasing the scale and adoption of public health interventions: a guide for developing a scaling up strategy. North Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss CO, Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K. Exploring the hierarchy of mobility performance in high-functioning older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62:167–73. 10.1093/gerona/62.2.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treacy D, Hassett L, Schurr K, et al. Validity of different activity monitors to count steps in an inpatient rehabilitation setting. Phys Ther 2017;97:581–8. 10.1093/ptj/pzx010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delbaere K, Hauer K, Lord SR. Evaluation of the incidental and planned activity questionnaire (IPEQ) for older people. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1029–34. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.060350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jette AM, Haley SM, Coster WJ, et al. Late life function and disability instrument: I. development and evaluation of the disability component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M209–16. 10.1093/gerona/57.4.M209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tennant A. Goal attainment scaling: current methodological challenges. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1583–8. 10.1080/09638280701618828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:63. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.EuroQol Group EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol 1991;13:50–64. 10.1123/jsep.13.1.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatcher RL, Gillaspy JA. Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychother Res 2006;16:12–25. 10.1080/10503300500352500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiviniemi MT, Voss-Humke AM, Seifert AL. How do I feel about the behavior? the interplay of affective associations with behaviors and cognitive beliefs as influences on physical activity behavior. Health Psychol 2007;26:152–8. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.S Oliveira J, Sherrington C, R Y Zheng E, et al. Effect of interventions using physical activity trackers on physical activity in people aged 60 years and over: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1188–94. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiedemann A, Rissel C, Howard K, et al. Health coaching and pedometers to enhance physical activity and prevent falls in community-dwelling people aged 60 years and over: study protocol for the Coaching for Healthy AGEing (CHAnGE) cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012277. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassett L, van den Berg M, Lindley RI, et al. Effect of affordable technology on physical activity levels and mobility outcomes in rehabilitation: a protocol for the activity and mobility using technology (amount) rehabilitation trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012074. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oliveira JS, Sherrington C, Paul SS, et al. A combined physical activity and fall prevention intervention improved mobility-related goal attainment but not physical activity in older adults: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2019;65:16–22. 10.1016/j.jphys.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamilton C, McCluskey A, Hassett L, et al. Patient and therapist experiences of using affordable feedback-based technology in rehabilitation: a qualitative study nested in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:1258–70. 10.1177/0269215518771820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haynes A, Sherrington C, Wallbank G, et al. "Someone's got my back”: older people’s experience of the coaching for healthy ageing program for promoting physical activity and preventing falls. J Aging Phys Act 2020:1–12. 10.1123/japa.2020-0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Older people's perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1268–76. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jang H, Clemson L, Lovarini M, et al. Cultural influences on exercise participation and fall prevention: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:724–32. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1061606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen CP, Wai JPM, Tsai MK, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378:1244–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60749-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farag I, Howard K, Ferreira ML, et al. Economic modelling of a public health programme for fall prevention. Age Ageing 2015;44:409–14. 10.1093/ageing/afu195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034696supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)