Abstract

Exposure to the mycotoxin aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) strongly correlates with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). P450 enzymes convert AFB1 into a highly reactive epoxide that forms unstable 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-guanyl)-9-hydroxyaflatoxin B1 (AFB1-N7-Gua) DNA adducts, which convert to stable mutagenic AFB1 formamidopyrimidine (FAPY) DNA adducts. In CYP1A2-expressing budding yeast, AFB1 is a weak mutagen but a potent recombinagen. However, few genes have been identified that confer AFB1 resistance. Here, we profiled the yeast genome for AFB1 resistance. We introduced the human CYP1A2 into ∼90% of the diploid deletion library, and pooled samples from CYP1A2-expressing libraries and the original library were exposed to 50 μM AFB1 for 20 hs. By using next generation sequencing (NGS) to count molecular barcodes, we initially identified 86 genes from the CYP1A2-expressing libraries, of which 79 were confirmed to confer AFB1 resistance. While functionally diverse genes, including those that function in proteolysis, actin reorganization, and tRNA modification, were identified, those that function in postreplication DNA repair and encode proteins that bind to DNA damage were over-represented, compared to the yeast genome, at large. DNA metabolism genes also included those functioning in checkpoint recovery and replication fork maintenance, emphasizing the potency of the mycotoxin to trigger replication stress. Among genes involved in postreplication repair, we observed that CSM2, a member of the CSM2(SHU) complex, functioned in AFB1-associated sister chromatid recombination while suppressing AFB1-associated mutations. These studies thus broaden the number of AFB1 resistance genes and have elucidated a mechanism of error-free bypass of AFB1-associated DNA adducts.

Keywords: genome profiling, aflatoxin, budding yeast, DNA damage, postreplication repair

The mycotoxin aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is a potent hepatocarcinogen. The signature p53 mutation, p53-Ser249, is often present in liver cancer cells from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients from AFB1-exposed areas, suggesting that AFB1 is a potent carcinogen because it is a genotoxin (Hsu et al. 1991; Shen and Ong 1996). A mutagenic signature associated with AFB1 exposure has been identified in HCC (Chawanthayatham et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2017). However, AFB1 is not genotoxic per se but is metabolically activated by P450 enzymes, such as CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 (Crespi et al. 1991; Eaton and Gallagher 1994; Gallagher et al. 1996), to form a highly reactive AFB1-8-9-epoxide (Baertschi et al. 1988). The epoxide reacts with protein, RNA, and DNA, yielding the unstable 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-guanyl)-9-hydroxyaflatoxin B1 (AFB1-N7-Gua) adducts that convert into stable AFB1-formamidopyrimidine (FAPY) adducts (Essigmann et al. 1977; Lin et al. 1977; Croy and Wogan 1981). The anomers of the AFB1-FAPY-DNA adduct block DNA replication or cause mutations in Escherichia coli (Smela et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2006) and in vitro (Lin et al. 2014). Metabolically active AFB1 can also indirectly damage DNA through oxidative stress (Shen et al. 1995; Beddard and Masey 2006; Bernabucci et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2015). Identifying genes that repair AFB1-associated DNA damage could help identify which individuals are at elevated risk for HCC. However, epidemiological data has been inconsistent, and only a few candidate DNA repair genes have been proposed, such as XRCC1 (Pan et al. 2011, Xu et al. 2015), XRCC3 (Long et al. 2008; De Mattia et al. 2017) and XRCC4 (Long et al. 2013).

AFB1 resistance genes have been identified from model organisms, revealing mechanisms by which AFB1-associated DNA adducts can be both tolerated and excised. Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathways function to remove AFB1-associated DNA adducts (Leadon et al. 1981; Alekseyev et al. 2004; Bedard and Massey 2006). Recently, the base excision repair gene (BER) NEIL1 has been implicated in direct repair AFB1-associated DNA adducts (Vartanian et al. 2017). To tolerate persistent AFB1-associated DNA lesions, translesion polymerases in yeast, such as those encoded by REV1 and REV7, and in mouse, such as Polζ, confer resistance and may promote genome stability (Lin et al. 2014).

While yeast does not contain endogenous P450 genes that can metabolically activate AFB1 into an active genotoxin (Sengstag et al. 1996; Van Leeuwen et al. 2012, Fasullo et al. 2014), human CYP1A2 can be expressed in yeast cells (Sengstag et al. 1996; Fasullo et al. 2014). Interestingly, metabolically activated AFB1 is a potent recombinagen but weak mutagen (Sengstag et al. 1996). CYP1A2-activated AFB1 reacts to form both the unstable AFB1-N7-Gua adducts and the stable AFB1-FAPY DNA adducts (Fasullo et al. 2008). The AFB1-associated DNA damage, in turn, triggers a robust DNA damage response that includes checkpoint activation (Fasullo et al. 2008), cell cycle delay (Fasullo et al. 2010), and the transcriptional induction of stress-induced genes (Keller-Seitz et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2006). Profiles of the transcriptional response to AFB1 exposure reveals induction of genes in growth and checkpoint signaling pathways, DNA and RNA metabolism, and protein trafficking (Keller-Seitz et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2006). While genes involved in recombinational repair and postreplication repair confer AFB1 resistance (Keller-Seitz et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2005; Fasullo et al. 2010), it is unclear the functional significance of many genes in the stress induced pathways in conferring resistance since transcriptional induction is not synonymous with conferring resistance (Birrell et al. 2002).

In this study, we profiled the yeast genome for AFB1 resistance. We asked which genes confer AFB1 resistance in the presence or absence of human CYP1A2 expression by screening the non-essential diploid collection by high throughput sequencing of molecular barcodes (Pierce et al. 2006; St Onge et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2010). While we expected to identify NER, recombinational repair, and postreplication repair, which had previously been identified (Keller-Seitz et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2005; Fasullo et al. 2010), our high throughput screen identified novel genes involved in AFB1 resistance. These included genes involved in Rad51 assembly, cell cycle progression, RNA metabolism, and oxidative stress. Our results thus underscore the importance of recombination in both mutation avoidance and in conferring AFB1 resistance.

Materials and Methods

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains were derived from BY4741, BY4743 (Brachmann et al. 1998) or YB204 (Dong and Fasullo 2003); all of which are of the S288C background (Table S1). The BY4743 genotype is MATa/α his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 LYS2/lys2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0. The diploid and haploid homozygous deletion libraries were purchased from Open Biosystems, and are now available from Dharmacon (http://dharmacon.gelifesciences.com/cdnas-and-orfs/non-mammalian-cdnas-and-orfs/yeast/yeast-knockout-collection/). The pooled diploid homozygous deletion library (n = 4607) was a gift of Chris Vulpe (University of Florida).

To construct the csm2 rad4 and csm2 rad51 double mutants, we first obtained the haploid csm2 strain (YA288, Table S1) from the haploid BY4741-derived deletion library. We introduced the his3 recombination substrates (Fasullo and Davis 1987) to measure unequal sister chromatid exchange (SCE) in the csm2 mutant by isolating the meiotic segregant YB558 from a diploid cross of YB204 with YA288. This csm2 strain (YB558) was subsequently crossed with MATα rad4::NatMX (YA289) and the csm2::KanMX rad4::NatMX meiotic segregant (YB660) was obtained. The rad51 csm2 double mutant was made by one step gene disruption (Rothstein 1983) using the Bam1H fragment rad51Δ (Shinohara et al. 1992) to select for Ura+ transformants in YB558.

Using LiAc-mediated gene transformation we introduced human CYP1A2 into BY4741, csm2, rad4, rad51, csm2 rad51, and csm2 rad4 strains. The CYP1A2-expression plasmid, pCS316, was obtained by CsCl centrifugation (Ausubel et al. 1995) and the restriction map was verified based on the nucleotide sequence of the entire plasmid. An alternative CYP1A2-expression plasmid, pCYP1A2_NAT2 was constructed by removing the hOR sequence from pCS316 and replacing it with a Not1 fragment containing the human NAT2.

Media and chemicals

Standard media were used for the culture of yeast and bacterial strains (Burke et al. 2000). LB-AMP (Luria broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin) was used for the culture of the bacterial strain DH1 strain containing the vector pCS316. Media used for the culture of yeast cells included YPD (yeast extract, peptone, dextrose), SC (synthetic complete, dextrose), SC-HIS (SC lacking histidine), SC-URA (SC lacking uracil), and SC-ARG (SC-lacking arginine). Media to select for canavanine resistance contained SC-ARG (synthetic complete lacking arginine) and 60 μg/mL canavanine (CAN) sulfate, and media to select for 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA) resistance contained SC-URA supplemented with 4x uracil and FOA (750 μg/ml), as described by Burke et al. (2000). FOA plates contained 2.2% agar; all other plates contained 2% agar. AFB1 was purchased from Sigma Co., and a 10 mM solution was made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Measuring DNA Damage-Associated recombination and mutation events

To measure AFB1-associated genotoxic events, log phase yeast cells (A600 = 0.5-1) were exposed to indicated doses of AFB1, previously dissolved in DMSO. Cells were maintained in synthetic medium (SC-URA) during the carcinogen exposure. After the exposure, cells were washed twice in H2O, and then plated on SC-HIS or SC-ARG CAN to measure unequal SCE or mutation frequency, respectively. An appropriate dilution was inoculated on YPD to measure viability (Fasullo et al. 2008).

Construction of CYP1A2-expression library

To introduce CYP1A2 (pCS316, Sengstag et al. 1996, and pCYP1A2_NAT2) into the yeast diploid deletion collection, we used a modified protocol for high throughput yeast transformation in 96-well plates (Gietz and Schiestl 2007). In brief, FOAR isolates were isolated from each individual strain in the diploid collection and inoculated in 96-well plates, each containing 100 μl of YPD medium. After incubation over-night at 30°, plates were centrifuged, washed in sterile H2O, and resuspended in one-step buffer (0.2 N LiAc, 100 mM DTT, 50% PEG, MW 3300, 500 μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA). After addition of 1 μg pCS316 and incubation for 30 min at 30°, 10 μl were directly inoculated on duplicate SC-URA plates. Two Ura+ transformants were chosen corresponding to each well and frozen in SC-URA 0.75% DMSO. We introduced the CYP1A2-containing plasmids into approximately 90% of the deletion collection.

Functional profiling of the yeast genome

The CYP1A2-expressing libraries were pooled and frozen in SC-URA medium containing 0.75% DMSO (n = 4150). The pooled cells (100 μl) were added to 2 ml of SC-URA and allowed to recover for two hours. Cell were then diluted to A600 = 0.85 in 2 ml of SC-URA and exposed to either 50 μM AFB1 in 0.5% DMSO, and 0.5% DMSO alone. Cells were then incubated with agitation at 30° for 20 hs. Similarly, the pooled BY4743 library (n = 4607) was directly diluted to A600 = 0.85 in YPD and also exposed to 50 μM AFB1 and DMSO for 20 hs. Independent triplicate experiments were performed for each library and each chemical treatment.

After AFB1 exposure, cells were washed twice in sterile H2O and frozen at -80°. Cells were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, 1% SDS, pH 8 and DNA was isolated by “smash and grab (Hoffman and Winston 1987).” Barcode sequences, which are unique for each strain in the deletion collection (Giaever et al. 2002; Giaever et al. 2004), were amplified by PCR using a protocol described by Smith et al. (2010). The primers used for amplification are listed in the Table S2. 125 bp PCR products were then isolated from 10% polyacrylamide gels by diffusion in 0.5M NH4Ac 1 mM EDTA for 24 hs (30°) followed by ethanol precipitation. The DNA was quantified after being resuspended in Tris EDTA pH 7.5 and the integrity of the DNA was verified by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide. Equal amounts of DNA were pooled from treated and untreated samples. The uptags were then sequenced using the Illumina Platform at the University Buffalo Genomics and Bioinformatics Core (Buffalo, New York). Sequence information was then uploaded to an accessible computer server for further analysis. The software to demultiplex the sequence information, match the uptag sequences with the publish ORFs, and calculate the statistical significance of the differences in log2N ratios was provided by F. Doyle. Tag counts were analyzed with the TCC Bioconductor package (Sun et al. 2013) using TMM normalization (Robinson and Oshlack 2010) and the edgeR test method (Robinson et al. 2010). Statistical testing was performed with edgeR TCC package for tag count comparison in the R programming language; an R script with invocation details is provided in the File S1. Data files have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database, GSE129699.

Over-enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) categories were identified by a hypergeometric distribution with freely available software from Princeton University using the Generic Gene Ontology Term Finder (http://go.princeton.edu/cgibin/GOTermFinder) and Bonferroni correction for P values. Enriched GO terms were further refined using ReViGO (Supek et al. 2011). Enrichment analysis was analyzed using Panther (http://pantherdb.org/tools/) with a P value cutoff of < 0.05 (Cherry et al. 2012, Mi et al. 2016). The AFB1 sensitivity of mutants corresponding to GO groups was verified by growth curves and trypan blue assays.

Growth assays in 96 well plate to measure AFB1 sensitivity

In brief, individual saturated cultures were prepared for each yeast strain. Cell density was adjusted to ∼0.8 × 107 cells/ml for all cultures. We maintained the cells in selective medium (SC-URA). In each microtiter well, 95 μl of media and 5 μl of cells (8 × 104 cells) were aliquoted in duplicate for blank, control and experimental samples. For experimental samples, we added AFB1, dissolved in DMSO, for a final concentration of 50 μM and 100 μM. The microtiter dish was placed in a plate reader that is capable of both agitating and incubating the plate at 30°, as previously described (Fasullo et al. 2010; Fasullo et al. 2014). We measured the A600 at 10 min intervals, for a total period for 24 hs, 145 readings. Data at 1h intervals was then plotted. To avoid evaporation during the incubation, the microtiter dishes were sealed with clear optical tape (Fasullo et al. 2010). To calculate area under the curve (AUC), we used a free graphing application (https://www.padowan.dk/download/), and measured the time interval between 0-20 hs, as performed in previous publications (O’Connor et al. 2012). After cells were exposed to AFB1 and DMSO, we calculated the ratio (AUC AFB1/AUCDMSO) × 100% to determine the percent yeast growth obtained in the presence of the toxin. For the wild-type diploid BY4743 expressing CYP1A2 (YB556), the percent of yeast growth after exposure to 50 μM is 89.7 ± 2.5. Statistical significance of differences between growth percentages for diploid strains and BY4743 were determined by the Student’s t-test, assuming constant variance between samples.

To determine epistasis of AFB1-resistance genes, we calculated the deviation ε according to ε = Wxy- Wx x Wy, where Wx and Wy are the fitness coefficients determined for each single mutant exposed to AFB1 and Wxy is the product. Fitness was calculated by determining the generation time of both the single and double mutants over three doubling times. Zero and negative values are indicative of genes that do not interact or participate in the same pathway to confer fitness (St. Onge et al. 2007).

Trypan blue exclusion assay to monitor cell viability after acute AFB1 exposure

To measure cell viability after AFB1 exposure, we performed a trypan blue exclusion assay. Selected strains expressing CYP1A2 were inoculated in SC-URA until cultures reached an A600 ∼0.1-0.5, and then exposed to either 50 μM in AFB1 or DMSO (solvent) alone. After incubating for 3 hs, cells were washed twice in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stained with trypan blue at a final concentration ∼10 μg/ml (Liesche et al. 2015). Cells were counted in a Nexcelom cellometer T4, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A minimum of 104 cells were counted and all strains were tested at least twice. Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t-test.

Western blot analysis

Expression of CYP1A2 was determined by Western blots and MROD assays. Cells were inoculated in SC-URA medium. Cells in log growth phase (A600 = 0.5–1) were concentrated and protein extracts were prepared as previously described by Foiani et al. (1994). Proteins were separated on 10% acrylamide/0.266% bis-acrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Human CYP1A2 was detected by Western blots using goat anti-CYP1A2 (Abcam), and a secondary bovine anti-goat antibody. For a loading control on Western blots, β-actin was detected using a mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam 8224) and a secondary goat anti-mouse antibody. Signal was detected by chemiluminescence, (Fasullo et al. 2014).

Measuring CYP1A2 enzymatic activity

We measured CYP1A2 enzymatic activity using a modified protocol described by Pompon et al. (1996). In brief, cells obtained from 100 ml of selective media were pelleted and resuspended in 5 ml Tris EDTA KCl (pH 7.5, TEK) buffer. After five minute incubation at room temperature, cells were pelleted, resuspended in 1 ml 0.6 M Sorbitol Tris pH 7.5, and glass beads were added. Cells were lysed by agitation. The debris was pelleted at 10,000 × g at 4°, and the supernatant was diluted in 0.6 M Sorbitol Tris pH 7.5 and made 0.15 M in NaCl and 1% in polyethylene glycol (MW 3350) in a total volume of 5 ml. After incubation on ice for 1 hr. and centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min, the precipitate was resuspended in Tris 10% glycerol pH 7.5, and stored at −80°.

CYP1A2 enzymatic activity was measured in cell lysates by quantifying 7-methoxyresorufin O-demethylase (MROD) activities (Fasullo et al. 2014), using a protocol similar to that quantifying ethoxyresorufin O-deethylase (EROD) activity (Eugster et al. 1992; Sengstag et al. 1994). The buffer contained 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5μM methoxyresorufin (Sigma) and 500 μM NADPH. The production of resorufin was measured in real-time by fluorescence in a Tecan plate reader, calibrated at 535 nm for excitation and 580 nm for absorption, and standardized using serial dilutions of resorufin. The reaction was started by the addition of NADPH and resorufin was measured at one minute intervals during the one hour incubation at 37°; rat liver microsomes (S9) were used as a positive control while the reaction without NADPH served as the negative control. Enzyme activities were measured in duplicate for at least two independent lysates from each strain and expressed in pmol/min/mg protein.

Data availability

All yeast strains and plasmids are available upon request and are detailed in Table S1. Three supplementary tables and two supplementary figures have been deposited in figshare. Next generation sequencing data (NGS) of barcodes are available at GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE129699). Additional supplementary files include six supplementary tables, three supplementary figures, and one file. Table S1 is a complete listing of strains and their genotypes. Table S2 is a complete listing of DNA oligonucleotides used in the HiSeq2000 experiments. Table S3 lists the methoxyresorufin demethylase (MROD) activities obtained from microsomal extracts of four deletion strains. Table S4 lists strains that were associated with positive m values. Table S5 lists strains that have not yet been confirmed as AFB1 sensitive by any criteria. Table S6 is a complete listing of the GO groups according to process for all 86 genes associated with negative m values identified in screens for AFB1 resistance. Figure S1 describes the percentage of growth obtained after 86 strains were exposed to 50 μM AFB1 and a subset of the more resistant strains that were exposed to both 50 μM and 100 μM AFB1. Figure S2 is a bar graph detailing the percent viability of strains after an acute exposure 50 μM AFB1. Figure S3 contains the growth curves for BY4743, shu1, shu2, and psy3 after exposure to 50 μM AFB1. File S1 describes edge R script with invocation details. Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25387/g3.12895313.

Results

We used three BY4743-derived libraries to profile the yeast genome for AFB1 resistance. The first was a pooled library of 4607 yeast strains, each strain containing a single deletion in a non-essential gene (Jo et al. 2009). The second was a pooled library of approximately 4900 strains each containing individual deletions in non-essential genes and was made by introducing pCS316 into each strain by yeast transformation. The third was a pooled library of approximately 5000 strains expressing both CYP1A2 and NAT2; this pooled library can be used to screen polyaromatic and heterocyclic compounds that require CYP1A2 and NAT2 for metabolic activation. By calculating area under the growth curves (AUC) for cells exposed to AFB1 and solvent (DMSO) alone and measuring the ratio (AUCAFB1/AUCDMSO), we determined that the AFB1 concentration to elicit ∼10% decrease in growth (D10,) for BY4743 expressing CYP1A2 (YB556) was 50 μM, while the dose to elicit a 16% decrease in growth (D16) was 100 μM. The number of AFB1 -associated DNA adducts formed in vivo after exposure to 100 μM AFB1 is less than twice of that detected after exposure to 50 μM AFB1 (Fasullo et al. 2008), suggesting that metabolic activation is more efficient after exposure to 50 μM AFB1; we therefore chose 50 μM AFB1 exposure to identify genes that confer resistance to AFB1-associated metabolites (Figure 1A). The D10 for BY4743 expressing CYP1A2 and the human oxidoreductase (hOR) was the same as in BY4743 cells expressing CYP1A2 and NAT2. To confirm metabolic activation of AFB1 into a potent genotoxin, we showed that growth of the rad52 diploid mutant was significantly impaired (Figure 1D). Cells that did not express CYP1A2 showed slight growth delay after cells were exposed to 100 μM AFB1 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Expression of CYP1A2 in the yeast diploid strain (BY4743). Top left (A) indicates CYP1A2-mediated activation of AFB1 to form a highly reactive epoxide that forms DNA, RNA, and protein adduct; Figure 1(A) adapted from Smela et al. (2002). The lower left panel (B) is a Western blot indicating 75, 50 and 37 kD molecular weight markers. Lanes A and B are lysates from BY4743 and BY4743 cells expressing CYP1A2 (YB556), respectively. The CYP1A2 (58 kD) protein and the β-actin (42 kD) protein are indicated. Right upper panel (C) is a growth curve of the diploid wild type (BY4743) and YB556 after exposure to 100 μM AFB1. Right lower panel (D) is a growth curve of YB556 and rad52 (CYP1A2, YB665) after exposure to 1% DMSO and 50 μM AFB1. Growth (A600) is plotted against time (Hs). Standard deviations are indicated at 1 h time points. Red lines indicate strains both expressing CYP1A2 and exposed to AFB1.

Confirmation of CYP1A2 activity

To confirm that CYP1A2 was both present and functional in the library, we performed Western blots (Figure 1B) and MROD assays, as in previous studies (Fasullo et al. 2014). Two independent assays were performed for four different ORFs (RAD2, RAD18, RAD55, and OGG1); the range of average MROD activity was 5-10 units pmol/sec/mg protein (see Table S3). These results are similar to what was observed for the wild type BY4743 expressing CYP1A2 (Fasullo et al. 2014) and for various haploid mutants (Guo et al. 2005). These studies indicate that CYP1A2 is active in diploid strains and can be detected by Western blots in BY4743-derived strains containing pCS316, in agreement with previous studies (Guo et al. 2005).

Identification of genes by barcode analysis

We classified genes that confer AFB1 resistance (q < 0.1) genes into: 1) those that confer resistance to AFB1 without CYP activation, and 2) those that confer resistance to P450-activated AFB1. After exposing cells to 50 μM AFB1, we identified barcodes for approximately 51% and 89% of the genes from pooled deletion library with and without CYP1A2, respectively (for complete listing, see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE129699).

One gene, CTR1, which functions in high-affinity copper and iron transport (Dancis et al. 1994), was identified as statistically different from the pooled library that did not express CYP1A2; this gene was identified twice in the screen (YPR124W and completely overlapping YPR123C). The human homolog confers drug resistance, suggesting human CTR1 is involved in xenobiotic transport (Furukawa et al. 2008). No DNA repair genes were identified in screening the library lacking CYP1A2, consistent with observations that cytochrome P450-metabolic activation AFB1 is required to form AFB1-associated DNA adducts (Fasullo et al. 2014).

Using the same stringent assessment (q < 0.1), in three independent screens, we identified 96 ORFs that confer AFB1 resistance in cells expressing CYP1A2, of which 86 genes have been ascribed a function, and one ORF, YBR099C, is completely internal to MMS4. Genes that confer resistance were associated with a negative m value (Table 1), as defined by fold change on a log2 scale; this indicates that corresponding deletion strains would be relatively depleted after AFB1 exposure, compared to exposure to solvent (DMSO) alone. Alternatively, genes associated with a positive m value (Table S4) imply that corresponding mutants would be relatively enriched after AFB1 exposure. 43 ORFs were only associated with a positive m value, and nine ORFs were associated with both a negative and positive m values in independent screens (Table S4).

Table 1. Fitness scores for 15 AFB1 resistant genes related to DNA repair and ranked by significance.

| Genea | m. valueb | Gene Functionc | q.valued |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAD54# | −6.60 | DNA-dependent ATPase that stimulates strand exchange; modifies the topology of double-stranded DNA; involved in the recombinational repair of double-strand breaks in DNA; member of the SWI/SNF family of DNA translocases; forms nuclear foci upon DNA replication stress | 3.09E-13 |

| MMS4 | −3.96 | Subunit of structure-specific Mms4p-Mus81p endonuclease; cleaves branched DNA; involved in recombination, DNA repair, and joint molecule formation/resolution during meiotic recombination | 4.44E-12 |

| RAD2* | −3.73 | Single-stranded DNA endonuclease; cleaves single-stranded DNA during nucleotide excision repair to excise damaged | 1.03E-10 |

| RAD55** | −3.98 | Protein that stimulates strand exchange; stimulates strand exchange by stabilizing the binding of Rad51p to single-stranded DNA | 1.96E-07 |

| REV3 | −4.15 | Catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase zeta | 2.39E-07 |

| RAD10** | −2.35 | Single-stranded DNA endonuclease (with Rad1p); cleaves single-stranded DNA during nucleotide excision repair and double-strand break repair | 3.04E-07 |

| REV1 | −4.07 | Deoxycytidyl transferase | 4.89E-06 |

| RAD17 | −4.24 | Checkpoint protein; involved in the activation of the DNA damage and meiotic pachytene checkpoints; with Mec3p and Ddc1p, forms a clamp that is loaded onto partial duplex DN | 9.13E-06 |

| RAD18** | −3.30 | E3 ubiquitin ligase; forms heterodimer with Rad6p to monoubiquitinate PCNA-K164 | 0.00421 |

| RAD23 | −6.20 | Protein with ubiquitin-like N terminus; subunit of Nuclear Excision Repair Factor 2 (NEF2) with Rad4p that binds damaged DNA; Rad4p-Rad23p heterodimer binds to promoters of DNA damage response genes to repress their transcription in the absence of DNA damage | 0.0188 |

| RAD4* | −2.22 | Protein that recognizes and binds damaged DNA (with Rad23p) during NER; subunit of Nuclear Excision Repair | 0.0499 |

| RAD1*# | −5.43 | Single-stranded DNA endonuclease (with Rad10p); cleaves single-stranded DNA during nucleotide excision repair and double-strand break repair; subunit of Nucleotide Excision Repair Factor 1 (NEF1); homolog of human XPF protein | 0.0612 |

| RAD5* | −3.79 | DNA helicase/Ubiquitin ligase; involved in error-free DNA damage tolerance (DDT), replication fork regression during postreplication repair by template switching, error-prone translesion synthesis | 0.0696 |

| CSM2# | −1.25 | Component of Shu complex (aka PCSS complex); Shu complex also includes Psy3, Shu1, Shu2, and promotes error-free DNA repair | 0.0790 |

| PSY3 | −2.12 | Component of Shu complex (aka PCSS complex); Shu complex also includes Shu1, Csm2, Shu2, and promotes error-free DNA repair; promotes Rad51p filament assembly | 0.0926 |

Genes in “bold” are those that are responsive to replication stress. *Appears twice among screens (q < 0.1). **Appears twice among screens (q < 0.1 and P < 0.05). #Transcription induced by AFB1 exposure.

m.value is the numeric vector of fold change on a log2 scale, rounded to three significant digits.

Gene function descriptions obtained from www.yeastgenome.org.

q value is the numeric vector calculated based on the p-value using the p.adjust function with default parameter settings, rounded to three significant digits.

To confirm the AFB1-sensitivity for strains associated with negative m values, we determined percent growth inhibition for individual strains and compared calculations with that obtained for BY4743 expressing CYP1A2 (YB556). The percent growth inhibition for 86 strains after exposure to 50 μM AFB1 was determined are listed in Figure S1; significance was determined by comparison with YB556. Among strains that indicated both positive and negative m values, growth curves indicated that these deletion strains were actually more AFB1-sensitive compared to the wild-type BY4743, consistent with the negative m values. We confirmed that of 79 out of 86 strains (92%) are AFB1-sensitive (Figure S1); growth curves are shown for a subset of these strains (Figure 2) and trypan blue staining indicated that viability is lost among representative strains after acute AFB1 exposure (Figure S2). Strains which have not been confirmed by any criteria are listed in Table S5. AUCs were calculated for a few strains (gtt1, ies2, sip18, tpo4) that were only associated with positive m values; none of these were AFB1-sensitive.

Figure 2.

Growth curves for selected diploid mutants identified in the high throughput screen. All strains contain pCS316, expressing CYP1A2. A600 is plotted against time (Hs). Standard deviations are indicated at 1 h time points. The growth curves (Panel A) are indicated for wild type (YB556) and the csm2, alk1, ssm4, cue1, and trm9 diploid mutants. Red lines indicate strains both expressing CYP1A2 and exposed to 50 μM AFB1. The bar graph (Panel B) indicates area percent growth of AFB1-exposed strains as determined by the ratio of the area under curves (area under the curve for treated strain/area under the curve for strain exposed to DMSO x 100%).

Of the 79 AFB1-sensitive strains, 15 (19%) are deleted in well-documented DNA repair genes (Table 1). Another 64 are deleted for genes that have diverse functions (Table 2) but also include an additional five genes (BLM10, FUM1, PSY2, DPB3, NUP60) noted to confer resistance to diverse DNA damaging agents and placed in the DNA repair gene ontology group (Table 3). Five different genes, participating in nucleotide excision repair, postreplication repair and ribosome assembly were twice found among the 79 strains. An additional five genes were found that that were highly statistically different (q < 0.1) in one screen and statistically different in another screen (P < 0.05). Among these were those involved in proteolysis (CUE1), vacuolar acidification (VOA1), cell cycle progression (FKH2), DNA recombinational repair (RAD55) and postreplication repair (RAD18).

Table 2. Fitness scores for 64 AFB1 resistant genes ranked by significance.

| Genea | m. valueb | Gene Functionc | q.valued |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIX23 | −4.06 | Mitochondrial intermembrane space CX(n)C motif protein | 4.35E-10 |

| MRPL35 | −4.28 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein of the large subunit | 9.14E-10 |

| BIT2 | −3.96 | Subunit of TORC2 membrane-associated complex | 1.47E-08 |

| MNN10 | −4.30 | Subunit of a Golgi mannosyltransferase complex | 1.59E-08 |

| YND1 | −4.43 | Yeast Nucleoside Diphosphatase | 2E-08 |

| SPO1 | −3.52 | Meiosis-specific prospore protein | 5.48E-07 |

| PYK2 | −3.94 | Pyruvate kinase; appears to be modulated by phosphorylation | 8.44E-07 |

| TMA20 | −3.18 | Protein of unknown function that associates with ribosomes; has a putative RNA binding domain; interacts with Tma22p; null mutant exhibits translation defects | 9.88E-07 |

| DET1 | −4.35 | Decreased ergosterol transport | 2.06E-06 |

| TRX3 | −4.37 | Mitochondrial thioredoxin | 2.62E-06 |

| SSM4 | −1.67 | Membrane-embedded ubiquitin-protein ligase; ER and inner nuclear membrane localized RING-CH domain E3 ligase involved in ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) | 5.11E-06 |

| AKL1 | −3.05 | Ser-Thr protein kinase; member (with Ark1p and Prk1p) of the Ark kinase family; involved in endocytosis and actin cytoskeleton organization | 5.26E-06 |

| PPG1 | −2.78 | Putative serine/threonine protein phosphatase; putative phosphatase of the type 2A-like phosphatase family, required for glycogen accumulation | 8.95E-05 |

| GTB1 | −2.68 | Glucosidase II beta subunit, forms a complex with alpha subunit Rot2p; relocalizes from ER to cytoplasm upon DNA replication stress | 8.95E-05 |

| NUP60 | −2.49 | FG-nucleoporin component of central core of the nuclear pore complex; contributes directly to nucleocytoplasmic transport and maintenance of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) permeability barrier and is involved in gene tethering at the nuclear periphery; relocalizes to the cytosol in response to hypoxia | 0.000118 |

| SVF1 | −2.61 | Protein with a potential role in cell survival pathways; required for the diauxic growth shift; expression in mammalian cells increases survival under conditions inducing apoptosis | 0.000253 |

| ATP15 | −3.46 | Epsilon subunit of the F1 sector of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP synthase | 0.000292 |

| ATO3 | −4.18 | Plasma membrane protein, putative ammonium transporter | 0.000931 |

| PET10 | −7.89 | Protein of unknown function that localizes to lipid particles; large-scale protein-protein interaction data suggests a role in ATP/ADP exchange | 0.00128 |

| DAL82 | −7.08 | Positive regulator involved in the degradation of allantoin | 0.00347 |

| PIB2 | −5.64 | PhosphatidylInositol(3)-phosphate Binding | 0.00421 |

| DPB3 | −2.16 | Third-largest subunit of DNA polymerase II (DNA polymerase epsilon); required to maintain fidelity of chromosomal replication; stabilizes the interaction of Pol epsilon with primer-template DNA | 0.00449 |

| CKB1 | −6.44 | Beta regulatory subunit of casein kinase 2 (CK2); a Ser/Thr protein kinase with roles in cell growth and proliferation; CK2, comprised of CKA1, CKA2, CKB1 and CKB2, has many substrates including transcription factors and all RNA polymerases | 0.00449 |

| RAV1 | −5.20 | Regulator of (H+)-ATPase in Vacuolar membrane | 0.00449 |

| SWM1# | −2.14 | Subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC); APC is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates the metaphase-anaphase transition and exit from mitosis | 0.00449 |

| GRE3 | −2.09 | Aldose reductase; involved in methylglyoxal, d-xylose, arabinose, and galactose metabolism; stress induced (osmotic, ionic, oxidative, heat shock, starvation and heavy metals) | 0.00449 |

| HXK2 | −2.08 | Hexokinase isoenzyme 2; phosphorylates glucose in cytosol; predominant hexokinase during growth on glucose; represses expression of HXK1, GLK1 | 0.00449 |

| PSY2 | −5.28 | Subunit of protein phosphatase PP4 complex; Pph3p and Psy2p form the active complex; regulates recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint,; putative homolog of mammalian R3 | 0.00663 |

| DIT1 | −3.58 | Sporulation-specific enzyme required for spore wall maturation | 0.00676 |

| CKB2 | −2.15 | Beta’ regulatory subunit of casein kinase 2 (CK2); a Ser/Thr protein kinase with roles in cell growth and proliferation | 0.0103 |

| MIS1 | −1.72 | Mitochondrial C1-tetrahydrofolate synthase; involved in interconversion between different oxidation states of tetrahydrofolate (THF); provides activities of formyl-THF synthetase, methenyl-THF cyclohydrolase, and methylene-THF dehydrogenase | 0.0164 |

| ATP11 | −1.87 | Molecular chaperone; required for the assembly of alpha and beta subunits into the F1 sector of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP synthase | 0.0193 |

| SCW10 | −7.88 | Cell wall protein | 0.0193 |

| ROT2 | −1.74 | Glucosidase II catalytic subunit; required to trim the final glucose in N-linked glycans; required for normal cell wall synthesis | 0.0200 |

| FKH2 | −1.70 | Forkhead family transcription factor; rate-limiting activator of replication origins | 0.0204 |

| TRM9 | −2.32 | tRNA methyltransferase; catalyzes modification of wobble bases in tRNA anticodons to 2, 5-methoxycarbonylmethyluridine and 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine; may act as part of a complex with Trm112p | 0.0228 |

| HHF1 | −1.78 | Histone H4 | 0.0265 |

| ATG29 | −2.10 | Autophagy-specific protein; required for recruiting other ATG proteins to the pre-autophagosomal structure (PAS) | 0.0265 |

| MYO4 | −1.71 | Type V myosin motor involved in actin-based transport of cargos | 0.0265 |

| PEX3 | −2.01 | Peroxisomal membrane protein (PMP); required for proper localization and stability of PMP | 0.0338 |

| FUM1 | −4.56 | Fumarase; converts fumaric acid to L-malic acid in the TCA cycle | 0.0338 |

| NRP1 | −1.48 | Putative RNA binding protein of unknown function; localizes to stress granules induced by glucose deprivation; predicted to be involved in ribosome biogenesis | 0.0340 |

| CUE1**# | −1.09 | Ubiquitin-binding protein; ER membrane protein that recruits and integrates the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc7p into ER membrane-bound ubiquitin ligase complexes that function in the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway for misfolded proteins | 0.0378 |

| YIH1 | −1.74 | Negative regulator of eIF2 kinase Gcn2p | 0.0403 |

| GLO1 | −1.84 | Monomeric glyoxalase I; catalyzes the detoxification of methylglyoxal (a by-product of glycolysis) via condensation with glutathione to produce S-D-lactoylglutathione; expression regulated by methylglyoxal levels and osmotic stres | 0.0473 |

| CLB5 | −1.74 | B-type cyclin involved in DNA replication during S phase | 0.0475 |

| VOA1** | −6.42 | ER protein that functions in assembly of the V0 sector of V-ATPase; functions with other assembly factors; null mutation enhances the vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) deficiency of a vma21 mutant impaired in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retrieval | 0.0499 |

| RPN10 | −1.88 | Non-ATPase base subunit of the 19S RP of the 26S proteasome | 0.0537 |

| RPS4A | −1.66 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit; mutation affects 20S pre-rRNA processing; homologous to mammalian ribosomal protein S4 | 0.0549 |

| RNR3 | −1.37 | Minor isoform of large subunit of ribonucleotide-diphosphate reductase; the RNR complex catalyzes rate-limiting step in dNTP synthesis, regulated by DNA replication and DNA damage checkpoint pathways via localization of small subunit | 0.0563 |

| DST1# | −1.88 | General transcription elongation factor TFIIS; enables RNA polymerase II to read through blocks to elongation by stimulating cleavage of nascent transcripts stalled at transcription arrest sites | 0.0567 |

| BCK2 | −1.76 | Serine/threonine-rich protein involved in PKC1 signaling pathway; protein kinase C (PKC1) signaling pathway controls cell integrity; overproduction suppresses pkc1 mutation | 0.0696 |

| BLM10 | −1.52 | Proteasome activator; binds the core proteasome (CP) and stimulates proteasome-mediated protein degradation by inducing gate opening; required for sequestering CP into proteasome storage granule (PSG) during quiescent phase | 0.0718 |

| ERV46 | −1.34 | Protein localized to COPII-coated vesicles; forms a complex with Erv41p; involved in the membrane fusion stage of transport | 0.0779 |

| AUA1 | −2.33 | Protein required for the negative regulation by ammonia of Gap1p; Gap1p is a general amino acid permease | 0.0779 |

| DUS1 | −1.81 | Dihydrouridine synthase; member of a widespread family of conserved proteins including Smm1p, Dus3p, and Dus4p; modifies pre-tRNA(Phe) at U17 | 0.0785 |

| RIT1 | −0.915 | Initiator methionine 2’-O-ribosyl phosphate transferase; modifies the initiator methionine tRNA at position 64 to distinguish it from elongator methionine tRNA | 0.0807 |

| GFD1 | −7.71 | Coiled-coiled protein of unknown function; identified as a high-copy suppressor of a dbp5 mutation; protein abundance increases in response to DNA replication stress | 0.0846 |

| BUD20* | −1.08 | C2H2-type zinc finger protein required for ribosome assembly; shuttling factor which associates with pre-60S particles in the nucleus, accompanying them to the cytoplasm | 0.0849 |

| LAG2 | −1.52 | Protein that negatively regulates the SCF E3-ubiquitin ligase; regulates by interacting with and preventing neddyation of the cullin subunit, Cdc53p | 0.0899 |

| CLG1 | −5.33 | Cyclin-like protein that interacts with Pho85p; has sequence similarity to G1 cyclins PCL1 and PCL2 | 0.0899 |

| MET6 | −5.90 | Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase; involved in methionine biosynthesis and regeneration; requires a minimum of two glutamates on the methyltetrahydrofolate substrate | 0.0917 |

| RVS167 | −3.59 | Calmodulin-binding actin-associated protein; roles in endocytic membrane tabulation and constriction, and exocytosis | 0.0926 |

| BSC1 | −2.24 | Protein of unconfirmed function; similar to cell surface flocculin Flo11p; | 0.0932 |

Genes in “bold” are those that are responsive to replication stress. *Appears twice among screens (q < 0.1). **Appears twice among screens (q < 0.1 and P < 0.05). #Transcription induced by AFB1 exposure.

m.value is the numeric vector of fold change on a log2 scale, rounded to three significant digits.

Gene function descriptions obtained from www.yeastgenome.org.

q value is the numeric vector calculated based on the p-value using the p.adjust function with default parameter settings, rounded to three significant digits.

Table 3. Aflatoxin resistant genes categorized by gene ontology groups involved in biological process and function.

| Term_ID | Description | P valuea | Annotationsb | Annotated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process GO:0006974 | Cellular response to DNA damage stimulus | 9.872E-09 | 22 | RAD4, CSM2, RAD23, RAD54, MMS4, DPB3, RAD55, RAD1, REV1, RAD18, CKB2, PSY3, REV3, FUM1, CKB1, BLM10, RAD2, RAD10, RAD17, NUP60, RAD5, PSY2 |

| GO:0006281 | DNA repair | 3.47E-08 | 20 | RAD4, CSM2, RAD23, RAD54, MMS4, DPB3, RAD55, REV1, RAD1, RAD18, PSY3, REV3, FUM1, BLM10, RAD2, RAD10, RAD17, NUP60, RAD5, PSY2 |

| GO:0019985 | Translesion synthesis | 2.56E-07 | 7 | CSM2, REV1, RAD5, DPB3, RAD18, PSY3, REV3 |

| GO:0000731 | DNA synthesis involved in DNA repair | 6.13E-07 | 7 | CSM2, REV1, RAD5, DPB3, RAD18, PSY3, REV3 |

| GO:0070987 | Error-free translesion synthesis | 7.62E-07 | 6 | CSM2, REV1, RAD5, RAD18, PSY3, REV3 |

| GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | 6.97E-06 | 23 | RAD4, FKH2, CSM2, RAD23, RAD54, MMS4, DPB3, RAD55, RAD1, REV1, RNR3, RAD18, PSY3, REV3, FUM1, CLB5, BLM10, RAD2, RAD10, RAD17, NUP60, RAD5, PSY2 |

| GO:0006301 | Postreplication repair | 1.47-05 | 7 | CSM2, REV1, RAD5, DPB3, RAD18, PSY3, REV3 |

| GO:0051716 | Cellular response to stimulus | 1.93E-05 | 34 | RAD4, GRE3, PSY3, SVF1, RAD2, MRPL35, RAD10, BIT2, NUP60, RAD5, DAL82, TRX3, PSY2, CUE1, CSM2, MMS4, RAD54, HXK2, RAD23, DPB3, YIH1, TRM9, RAD55, REV1, RAD1, TCM62, SSM4, RAD18, CKB2, REV3, FUM1, CKB1, BLM10, RAD17 |

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 2.03E-05 | 29 | RAD4, CUE1, CSM2, RAD23, RAD54, MMS4, YIH1, DPB3, GRE3, RAD55, RAD1, REV1, TCM62, SSM4, CKB2, RAD18, PSY3, FUM1, REV3, SVF1, CKB1, BLM10, RAD2, RAD10, RAD17, NUP60, RAD5, TRX3, PSY2 |

| GO:0006302 | Double-strand break repair | 2.05E-05 | 12 | RAD1, PSY3, REV3, RAD10, CSM2, RAD17, NUP60, RAD5, RAD54, MMS4, PSY2, RAD55 |

| GO:0042276 | Error-prone translesion synthesis | 3.69E-05 | 6 | REV1, RAD5, RAD18, DPB3, REV3 |

| GO:1903046 | Meiotic cell cycle process | 0.00490 | 13 | RAD1, DIT1, HHF1, CLB5, SPO1, RAD10, CSM2, RAD17, RAD54, MMS4, SWM1, PSY2, RAD55 |

| GO:0071897 | DNA biosynthetic process | 0.00210 | 9 | RAD1, REV1, RAD18, PSY3, REV3, RAD10, CSM2, RAD5, DPB3 |

| Function GO:0003684 | Damaged DNA binding | 4.50e-05 | 6 | RAD1, RAD17, REV1, RAD4, RAD23, RAD10 |

| GO:0004536 | Deoxyribonuclease activity | 0.00759 | 5 | RAD1, DPB3, RAD10, RAD2, RAD55 |

Adjusted P value using Bonferroni Correction, rounded to three significant digits.

Total annotated genes out of 79 genes.

According to GO process enrichment (https://go.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/GOTermFinder), resistance genes included those that function in the DNA damage response, DNA repair, postreplication repair, DNA damage stimulus, and meiotic cell cycle progression; 13 GO groups are shown in Table 3 (for full list of complete 86 putative ORFs, see Table S6). Of the 79 AFB1 resistance genes, 42 genes belong to the top 13 GO groups. One GO group that was unexpected was meiotic cell cycle process, which includes meiotic-specific genes SPO1 and DIT1. Among the stress responsive genes are those that function in cell wall maintenance and glycogen metabolism, which were previously identified to confer resistance to a variety of toxins, such as benzopyrene and mycophenolic acid (O’Connor et al. 2012). Other genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, such as GRE3 that encodes aldose reductase, could have a direct role in detoxification and is induced by cell stress (Barski et al. 2008). Genes involved in rearrangement of the cellular architecture include BIT2, AKL1 and PPG1; these genes function to rearrange the cellular architecture when cells are stressed (Schmidt et al. 1996). Thus, among AFB1 resistance genes are those that function to maintain structural integrity by affecting the cytoskeletal and cell wall architecture.

Other gene ontology groups encompass functions involved in mitochondrial maintenance and response to oxidative stress, and RNA metabolism (Table S6). Genes involved in mitochondrial function and response to oxidative stress include TRX3, MRPL35, MIX23, MIS1; TRX3 (thioredoxin reductase) functions to reduce oxidative stress in the mitochondria (Greetham and Grant 2009). RNA metabolism genes include those involved in chemical modification of tRNA, including MIS1, TRM9, DUS1, and RIT1, and those involved in RNA translation, such as TMA20 and YIH1. TRM9 confers resistance to alkylated DNA damage, and links translation with the DNA damage response (Begley et al. 2007). These genes are consistent with the notion that AFB1 causes oxidative damage and that mitochondria are targets of AFB1-induced DNA damage.

In grouping genes according to protein function and cellular components (Table 3 and Table 4), DNA repair complexes were readily identified. Among these were the Shu complex, and the NER complexes I and II (Table 4). However, other interesting complexes that were identified included the glycosidase II complex, and the CK2 complex. Because DNA repair and DNA damage response genes were the most prominent of the GO groups, we focused on the function of these genes in conferring AFB1 resistance. As expected, these genes included those that participate in DNA recombination (RAD54, RAD55), nucleotide excision repair (RAD1, RAD4, RAD1,RAD10, RAD23), and postreplication repair (RAD5, RAD18, REV1, REV3). Many of these genes function in cell cycle progression. For example, PSY2 and CKB2 (Toczyski et al. 1997) promote cell cycle progression after cell cycle delay or arrest caused by stalled forks or double-strand breaks, respectively.

Table 4. Protein complexes that participate in AFB1 resistance.

| GO-term | Descriptiona | Count in gene setb | Genesc | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:1990391 | DNA repair complex | 7 of 28 | RAD1, RAD2 RAD10, RAD4, RAD23, CSM2, PSY3 | 5.22E-05 |

| GO:0000109 | Nucleotide-excision repair complex | 5 of 16 | RAD1, RAD2 RAD10, RAD4, RAD23 | 0.00063 |

| GO:0017177 | Glucosidase II complex | 2 of 2 | GTB1, ROT2 | 0.0214 |

| GO:0000111 | Nucleotide-excision repair factor 2 complex | 2 of 3 | RAD4, RAD23 | 0.0299 |

| GO:0000110 | Nucleotide-excision repair factor 1 complex | 2 of 3 | RAD1, RAD10 | 0.02909 |

| GO:0005956 | Protein kinase CK2 complex | 2 of 4 | CKB1, CKB2 | 0.0385 |

| GO:0097196 | Shu complex | 2 of 4 | CSM2, PSY3 | 0.0385 |

Represents the number present among 79 genes.

To determine which GO biological processes and protein functions were most enriched among the AFB1 resistance genes we used the Panther software (Mi et al. 2016). A larger proportion of the AFB1 resistance genes are involved in DNA repair and metabolism, compared with the genome at large (Figure 3). A fraction of these genes also participate in postreplication repair, including DNA tolerance pathways that are error-free and error-prone replication (Table 5). In classifying protein functions, we analyzed whether hydrolases, nucleases, phosphatases, DNA damage binding were more enriched among the 79 AFB1 resistance genes, compared to the genome, at large (Figure 3). Of these groups, DNA damage binding was enriched among resistance genes (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

GO enrichment 79 AFB1 resistance genes, according to biological process and protein function. The top circles represent the number of genes of that are grouped according to Process, using the Generic Gene Ontology Term Finder, http://go.princeton.edu/cgibin/GOTermFinder. The bottom circles are those which are grouped according to protein function, using GO term finder according to function, https://www.yeastgenome.org/goSlimMapper. GO process groups included translesion synthesis, DNA synthesis involved in DNA repair, postreplication repair, DNA biosynthetic process, cellular response to DNA damage, DNA repair, meiotic cell cycle process, response to stress, and cellular response to stimulus. GO function groups include ion binding, hydrolase, nucleic acid binding, oxidoreductase, and transcription factors. Number of genes belonging to each GO is indicated within or just outside the pie slice.

Table 5. Enrichment of DNA repair and stress-responsive genes among AFB1 resistant genes.

| GO Biological Process | Yeasta | AFB1 Resistant Genes | Expectedb | Foldc Enrichment | P valued. | Significancee. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular response to DNA damage stimulus | 338 | 22 | 5 | 4.5 | 1.20E-06 | + |

| DNA synthesis involved in DNA repair | 20 | 7 | <1 | >7 | 8.00E-05 | + |

| Translesion synthesis | 18 | 7 | <1 | >7 | 4.42E-05 | + |

| DNA repair | 293 | 19 | 4 | 4.5 | 2.47E-05 | + |

| Cellular response to stress | 711 | 29 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 1.48E-04 | + |

| Postreplication repair | 30 | 7 | <1 | >7 | 8.35E-04 | + |

| Double-strand break repair | 136 | 11 | 2 | 5.6 | 5.97 E-03 | + |

| DNA biosynthetic process | 98 | 9 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 1.58 E-02 | + |

Number of total yeast genes in GO group based on reference list of 6026.

Number of expected genes among initial set of 79 ORFs based on reference list of 6026 genes; fractional values less than 1 were designated as <1.

Fold enrichment is the ratio of the number of AFB1 resistant genes identified to the expected number.

Displaying only results for Bonferroni-corrected probabilities, P < 0.05.

Significance indicated by “+”

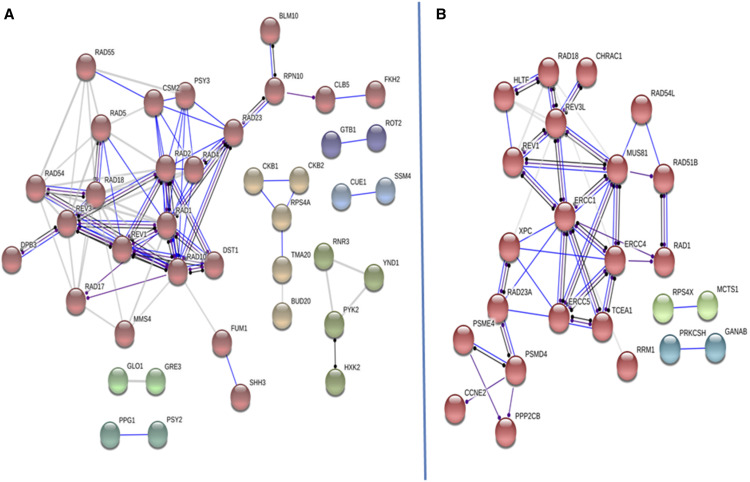

To further determine the strength of the interactions among the confirmed 79 AFB1 resistance genes, we performed interactome mapping, using STRING software (https://string-db.org/, Szklarczyk et al. 2019), which associates proteins according to binding, catalysis, literature-based, and unspecified interactions (Figure 4). The interactome complex in yeast included 78 nodes and 152 edges with a 3.77 average node degree. Besides the NER complexes, individual complexes included the Shu complex, the Glucosidase II complex, and the protein kinase CK2 complex (Table 4); the glucosidase II complex is conserved in mammalian cells (Figure 4). While the strength and number of these interactions was particularly strong among the DNA repair genes, other interactions were elucidated, such as the interactions of protease proteins with cell cycle transcription factors and cyclins (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The protein interactome encoded by AFB1 resistance genes in budding yeast (left, A) and protein interactome encoded by their associated human homologs (right, B). The interactome was curated using String V11 (https://string-db.org, Szklarczyk et al. 2019), using a high confidence level of 0.7 and MCL cluster factor of 1.1. Proteins are represented by colored circles (nodes); different colors represent distinct interacting clusters. A core group, in red seen in both images, includes proteins that function in DNA repair pathways, and interact with proteases, transcription and cell cycle factors. Lines represent the edges; a solid blue line indicates a binding event, a dark line indicates a reaction, and a purple line indicates catalysis. The lighter lines indicate a strong connection, as deduced from the literature. Lines that terminate with a dot indicate an unspecified interaction, whether positive or negative.

Since many known AFB1 resistance genes, which function in DNA repair and postreplication repair pathways, were not present among highly statistically different genes (q < 0.1), we also used a less stringent (P < 0.05) qualifier to identify potential AFB1 resistance genes. Among genes identified were additional members of the SHU complex, including SHU1 and SHU2. These genes were confirmed by additional growth curves (Figure S3) and the percent growth was determined (Figure S1).

The SHU complex was previously identified as participating in error-free DNA damage tolerance and mutation avoidance (Shor et al. 2005, Xu et al. 2013). The complex confers resistance to alkylating agents, such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), and cross-linking agents, such as cisplatin, but not to UV and X-ray (Godin et al. 2016). We previously showed that while X-ray associated unequal SCE (SCE) was RAD5-independent (Fasullo and Sun 2017), MMS and 4NQO-associated unequal SCE occurs by well-conserved RAD5-dependent mechanisms (Unk et al. 2010; Fasullo and Sun 2017). We therefore postulated that the SHU complex suppresses AFB1-associated mutagenesis while promoting AFB1-associated template switching. We introduced pCS316 (CYP1A2) into both the haploid wild-type strain (YB204) and a csm2 mutant (YB558, see Table S1) to measure frequencies of AFB1-associated unequal SCE and can1 mutations. Our results showed that while we observed a threefold increase in SCE after exposure to AFB1 in wild type strains, we observed less than a twofold increase in sister chromatid exchange in the csm2 mutant (Figure 5). However, we observed a net increase in AFB1-associated CanR mutations in the in csm2 mutant, compared to wild type (P < 0.05). Average survival was only slightly higher in the wild type (51%) than in the csm2 mutant (49%), but not statistically different (P = 0.8, N =4). We suggest that similar to MMS-associated DNA lesions, CSM2 functions to suppress AFB1-associated mutagenesis while promoting template switching of AFB1-associated DNA adducts.

Figure 5.

AFB1-associated sister chromatid recombination and mutagenesis frequencies in the wild type and csm2 haploid mutant. The top part of each panel shows the assays for sister chromatid exchange and mutagenesis; for both assays the oval represents the centromere and the single line represents duplex DNA. For simplicity, the left arm of chromosomes IV and V are not shown. (Top left, A) Unequal sister chromatid recombination is monitored by selecting for His+ prototrophs that result from recombination between the juxtaposed, truncated his3 fragments. The his3-Δ3′ lacks the 3′ sequences (arrow head), while the his3-Δ5′ lacks to promoter sequences (feathers). Both his3 fragments are located with the amino acid reading frames oriented to the centromere. The his3 fragments share a total of 450 bp sequence homology. Bottom of panel A shows the frequencies of unequal sister chromatid exchange (SCE) obtained from the wild type (YB204 pCS316) and the haploid csm2 mutant (YB559) after exposure to 0, 15, and 25 μM AFB1. (Top right, B) The arrow notes the occurrence of point, missense, or deletion mutations that can occur in the CAN1 gene and result in canavanine resistance (CanR) mutations. Bottom of panel B shows the frequencies of (CanR) mutants in wild type (YB204 pCS316) and csm2 (YB559) strain after exposure to 0 and 50 μM AFB1. For complete genotype, see Table S1.

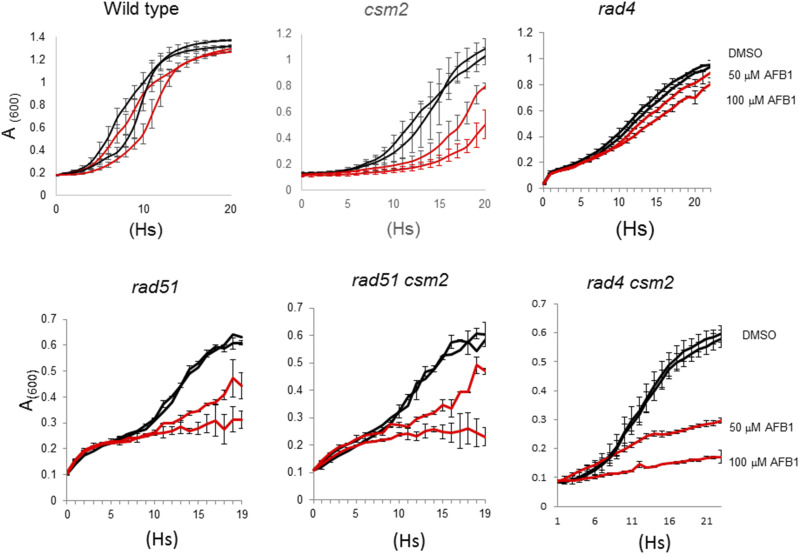

If CSM2 participates in a RAD51-dependent recombinational repair pathway to tolerate AFB1-associated DNA lesions, then we would expect that RAD51 would be epistatic to CSM2 for AFB1 resistance (Glassner and Mortimer 1994). We measured AFB1 sensitivity in the csm2, rad51 and csm2 rad51 haploid mutants compared to wild type, using growth curves (Figure 6). Our data indicate the csm2 rad51 double mutant is no more AFB1 sensitive compared to either rad51 single mutants indicating that CSM2 and RAD51 are in the same epistasis group for AFB1 sensitivity. In contrast, csm2 rad4 double mutants are more sensitive to AFB1 than either the csm2 and rad4 single mutants; the fitness measurement of the double mutant (0.071) is also less than the product of the csm2 (0.34) and rad4 (0.28) single mutants. These data indicate that CSM2 participates in a RAD51-mediated pathway for AFB1 resistance, and similar to RAD51, confers AFB1 resistance in a rad4 mutant (Fasullo et al. 2010).

Figure 6.

Growth curves of wild type (YB155), csm2 (YB557), rad4 (YB661), rad51 (YB177), csm2 rad51 (YB663), and csm2 rad4 (YB660) haploid cells after exposure to 50 and 100 μM AFB1. (Left) Growth of cells containing pCS316 and expressing CYP1A2 after chronic exposure to 0.5% and 1.0% DMSO (black), 50 μM (red), and 100 μM (red) AFB1. The relevant genotype is given above the panel (see Table S1, for complete genotype). Approximately 105 log-phase cells were inoculated in each well, n = 2. A600 is plotted against time (hs). Bars indicate the standard deviations of measurements, n = 2.

Human orthologs for many essential yeast genes can directly complement the corresponding yeast genes (Kachroo et al. 2015). Human homologs are listed for 46 yeast AFB1-resistance genes (Table 6). These homologs include those for DNA repair, DNA damage tolerance, cell cycle, and cell maintenance genes. Several of these genes, such as the human CTR1 (Zhou and Gitschier 1997), can directly complement the yeast gene. Other DNA human DNA repair genes, such as those that encode RAD54 (Kanaar et al. 1996), RAD5 (Unk et al. 2010), and RAD10 orthologs, can partially complement sensitivity to DNA damaging agents (Aggarwal and Brosh 2012).

Table 6. Human genes orthologous to yeast resistance genes.

| Yeast Genea | Human Geneb | Description/Function |

|---|---|---|

| AKL1 | AAK1 | Adaptor protein 2 associated kinase 1 |

| ATP11 | ATPAF1 | F1-ATPase assembly factor 1 |

| ATP15 | ATP5E | ϵ subunit of human ATP synthase |

| BLM10 | PSME4 | Proteasome activator complex subunit 4 |

| CKB1 | CSNK2B | Casein kinase II subunit beta |

| CKB2 | CSNK2B | Casein kinase II subunit beta |

| CLB5 | CCNE2 | G1/S-specific cyclin-E2 |

| DST1 | TCEA1 | Transcription elongation factor A1 |

| DPB3 | CHRAC1 | Chromatin accessibility complex protein 1 |

| FKH2 | FOXE1 | Forkhead box protein E1 |

| FUM1 | FH | Fumarate hydratase, mitochondrial |

| GLO1 | GLO1 | GLyOxalase |

| GRE3 | AKRA1,B1,D1, E2, B10 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member, A1, B1, D1, E2, B10 |

| GTB1 | PRKCSH | Protein kinase C substrate 80K-H |

| HHF1 | HIST1H4D | Histone H4 |

| MIS1 | MTHFD1 | Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase |

| MIX23 | CCDC58 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 58 |

| MMS4 | EME1 and EME2 | Essential meiotic structure-specific endonuclease 1, essential meiotic structure-specific endonuclease subunit 2 |

| MRPL35 | MRPL38 | Large subunit mitochondrial ribosomal protein L38 |

| NRP1 | TEX13B | N (asparagine)-Rich Protein, Testis-expressed protein 13B |

| PEX3 | PEX3 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 3 |

| PPG1 | PPP2CB | Protein Phosphatase involved in Glycogen accumulation |

| PSY2 | PPP4R3B | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 4 regulatory subunit 3B |

| RAD1 | ERCC4 | DNA repair endonuclease XPF |

| RAD2 | ERCC5 | DNA repair protein complementing XP-G cells |

| RAD4 | XPC | DNA repair protein complementing XP-C cells |

| RAD5 | HLTF | Helicase-like transcription factor involved in DNA damage tolerance |

| RAD10 | ERCC1 | Excision Repair Cross-Complementing 1 ERCC1 |

| RAD17 | RAD1 | Cell cycle checkpoint protein RAD1 |

| RAD18 | RAD18 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RAD18 |

| RAD23 | RAD23A | UV excision repair protein RAD23 homolog A |

| RAD54 | RAD54L | DNA repair and recombination protein RAD54-like |

| RAD55 | RAD51B | DNA repair protein RAD51 paralog B |

| RAV1 | DMXL2 | Dmx like 2 also known as rabconnectin-3, involved in vacuolar acidification |

| REV1 | REV1 | REV1, DNA directed polymerase |

| REV3 | REV3L | REV3 Like, DNA directed polymerase zeta catalytic subunit |

| RNR3 | RRM1 | Ribonucleotide reductase catalytic subunit M1 |

| ROT2 | GANAB | Glucosidase alpha, neutral C |

| RPN10 | PSMD4 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4 |

| RPS4A | RPS4X | Ribosomal Protein of the Small subunit, 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform |

| SPO1 | PLA2G4A | Phospholipase A2 group IVA |

| SSM4 | MARCH6 | Membrane associated ring-CH-type finger 6 |

| TMA20 | MCTS1 | Malignant T-cell-amplified sequence 1, translation re-initiation and release factor |

| TRM9 | ALKB8 | Alkylated DNA repair protein alkB homolog 8 |

| YIH1 | IMPACT | Impact RWD domain protein; translational regulator that ensures constant high levels of translation upon a variety of stress conditions; impact RWD domain protein |

| YND1 | ENTPD4 and ENTPD7 | Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 4 and 7 |

Human genes derived from https://www.alliancegenome.org/gene/SGD:S000004022.

Discussion

Human CYP1A2-mediated activation of the mycotoxin AFB1 generates a highly reactive epoxide that interacts with DNA, RNA, and protein, forming adducts which interfere in replication, transcription, and protein function. Previous experiments have documented the role of checkpoint genes, RAD genes, and BER genes in conferring AFB1 resistance in budding yeast (Keller-Seitz et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2005; Fasullo et al. 2010). The goal of this project was to identify additional AFB1 resistance genes that may elucidate why AFB1 is a potent yeast recombinagen but a weak mutagen (Sengstag et al. 1996).

Here, we profiled the yeast genome for AFB1 resistance using three yeast non-essential diploid deletion libraries; one was the original library and the other two expressed human CYP1A2. We identified 96 ORFs, of which 86 have been ascribed a function and 79 were confirmed to be AFB1 sensitive, relative to the wild type. These resistance genes reflect the broad range of functions, including cellular and metabolic processes, actin reorganization, mitochondrial responses, and DNA repair. Many of the DNA repair genes and checkpoint genes have been previously identified in screens for resistance to other toxins (Lee et al. 2005; Giaever and Nislow 2014; De La Rosa et al. 2017). While individual resistance genes are shared among diverse toxins, such as doxorubicin, nystatin, cycloheximide, rapamycin, and amphotericin, the top ten AFB1-associated GO enrichments are not represented among these diverse toxins. However, AFB1-associated GO enrichments, including postreplication repair and translesion synthesis, are shared among genes that confer resistance to cross-linking agents, such as trichloroethylene (De La Rosa et al. 2017) and cisplatin (Lee et al. 2005). One similarity between cross-linking agents and metabolically activated AFB1 is that they can form DNA adducts that impede DNA replication.

While mitochondrial maintenance genes and oxidative stress genes (Amici et al. 2007; Mary et al. 2012) are expected AFB1 resistance genes based on studies of individual mutants (Guo et al. 2005; Fasullo et al. 2010), we also identified novel AFB1 resistance genes that participate in DNA postreplication repair, both by modulating checkpoint responses and by recombination-mediated mechanisms. Of key importance, the CSM2/SHU complex (Shor et al. 2005) was required for AFB1-associated sister chromatid recombination, underscoring the role of recombination-mediated template switch mechanisms for tolerating AFB1-associated DNA damage. Since many yeast genes are conserved in mammalian organisms (Bernstein et al. 2011), we suggest similar mechanisms for tolerating AFB1-associated DNA damage may be present in mammalian cells.

We used a novel reagent consisting of a pooled yeast library expressing human CYP1A2, on a multi-copied expression vector. Because CYP1A2 activates AFB1 when toxin concentration is low (Eaton and Gallagher 1994), our modified yeast library mimicked AFB1 activation when low hepatic AFB1 concentrations generate DNA adducts. One limitation of the screen in the CYP1A2-expressing library is that AFB1-associated toxicity is not directly proportional to AFB1 concentration (Fasullo et al. 2010); we speculate that CYP1A2 activity is the limiting factor. Although individual yeast strains expressed similar amounts of CYP1A2 activity from among the subset of deletion strains tested, it is still possible that profiling resistance among individual deletion strains is influenced by the stability or variable expression of the membrane-associated human CYP1A2 (Murray and Correia 2001). Second, many DNA repair and checkpoint genes that were previously documented to confer resistance, such as RAD52, were not identified in the screen (Guo et al. 2006; Fasullo et al. 2010). One possible reason is that some, such as rad52, grow poorly (Figure 1, Fasullo et al. 2008), and we suspect that other slow-growing strains dropped out early in the time course of exposure. Future experiments will more carefully assess generation times needed to detect known resistance genes in the library expressing CYP1A2.

Because metabolically activated AFB1 causes protein, RNA, and lipid damage (Weng et al. 2017), besides DNA damage, we expected to find a functionally diverse set of AFB1 resistance genes. Among AFB1 resistance genes were those involved in protein degradation and ammonia transport, actin reorganization, tRNA modifications, ribosome biogenesis, RNA translation, mitochondrial, and metabolic functions. Some genes encoding these functions, such as BIT2 and TRM9, have important roles in maintaining genetic stability and in double-strand break repair (Schmidt et al. 1996; Begley et al. 2007; Schonbrun et al. 2013; Shimada et al. 2013). A more direct role in DNA repair mechanisms have been noted for FUM1 (Leshets et al. 2018; Saatchi and Kirchmaier 2019), DPB3 (Gallo et al. 2019), and BLM10 (Qian et al. 2013). Several genes, such as PPG1, are involved in glycogen accumulation; these genes are also required to enter the quiescent state (Li et al. 2015). Other genes are involved in cell wall synthesis, including MNN10, SCW10 and ROT2; we speculate that cell wall synthesis genes confer resistance by impeding AFB1 entrance into the cell, while genes involved in protein degradation in the ER may stabilize CYP1A2 and thus enhance AFB1-conferred genotoxicity. Indeed, two resistance genes, CUE1 and SSM4, are associated with degradation of mammalian P450 proteins in yeast (Murray and Correia 2001). Glucan and other cell wall constituents have also been speculated to directly inactivate AFB1, and yeast fermentative products are supplemented in cattle feed to prophylactically reduce AFB1 toxicity (Pereyra et al. 2013).

Although AFB1-associated cellular damage is associated with oxidative stress (Amici et al. 2007; Mary et al. 2012; Liu and Wang 2016) only a few yeast genes that confer resistance to reactive oxygen species (ROS) were identified in our screens. These genes included TRX3, YND1, VPS13, BIT2, GTP1, FKH2, SHH3, NRP1, and BUD20, which have a wide variety of functions (Schmidt et al. 1996; Greetham and Grant 2009; Bassler et al. 2012). While known genes associated with oxidative stress and oxidative-associated DNA damage, such as YAP1, SOD1, and APN1, were not identified, other mitochondrial genes, such as TRX3, were identified. Guo et al. (2005) also showed that the haploid apn1 mutant was not AFB1 sensitive. We offer two different explanations: first, the AFB1-associated oxidative damage is largely localized to the mitochondria, and second, there may be redundant pathways for conferring resistance to AFB1-associated oxidative damage, and therefore single genes were not identified. It is most likely the later as screens with oxidants (like t-BuOOH) also fail to identify expected antioxidant enzymes (Said et al. 2004).

A majority of the AFB1 resistance genes belong to GO groups that include postreplication repair, DNA damage-inducible genes, DNA repair, response to stimulus, or response to replication stress (Table 3). Proteins encoding functionally diverse genes, such as RAD54, RAD5, GFD1, TMA20, SKG3, GRE3, and ATG29, are repositioned in the yeast cells during DNA replication stress (Tkach et al. 2012). The requirement for unscheduled DNA synthesis was illustrated by identifying genes involved in the DNA damage-induced expression of ribonucleotide reductase; these included RNR3 and TRM9. TRM9, involved in tRNA modification, functions to selectively translate DNA damage-inducible genes, such as RNR1 (Begley et al. 2007).

One unifying theme was that cell cycle progression and recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest is a prominent role in mediating toxin resistance. FKH2 functions as a transcription factor that promotes cell cycle progression and G2-M progression. Other genes are involved in the modulation of the checkpoint response, such as PSY2. While CKB1 and CKB2 have broad functions, including histone phosphorylation and chromatin remodeling (Barz et al. 2003; Cheung et al. 2005), CKB2 is also required for toleration of double-strand breaks (Guillemain et al. 2007; Toczyski et al. 1997), and thus may function for the toleration of AFB1-associated damage. These genes support the notion that some of the AFB1-associated DNA adducts are well tolerated and can be actively replicated.

While we expected to identify individual genes involved in DNA damage tolerance, such as RAD5, REV1, REV3, the CSM2/PSY3 complex is novel. Absence of CSM2 confers deficient AFB1-associated SCE but higher frequencies of AFB1-associated mutations, suggesting that CSM2 functions to suppress AFB1-associated mutations by RAD51-mediated template switch mechanisms (Guo et al. 2006; Fasullo et al. 2008). Consistent with this idea, RAD51 is epistatic to CSM2 in conferring AFB1 sensitivity, while rad4 cms2 double mutant exhibits synergistic AFB1 sensitivity with respect to the single rad4 and csm2 single mutants. However, rad4 rad51 mutants still exhibit more AFB1 sensitivity than rad4 csm2, suggesting that RAD51 may be involved in conferring resistance to other AFB1-associated DNA lesions, such as double-strand breaks. We also expect that the RAD51 paralogs, RAD55 and RAD57, share similar AFB1-associated functions with RAD51. Considering that RAD57 is the XRCC3 ortholog, determining whether yeast RAD51 paralogs suppress AFB1-associated mutation will aid in identifying similar complexes in mammalian cells. Such complexes may elucidate why XRCC3 polymorphisms are risk factors in AFB1-associated liver cancer (Long et al. 2008; Ji et al. 2015).

Human homologs of several of the identified yeast genes (Table 6) are, hyper-methylated, mutated, or over-expressed in liver disease and cancer. For example, mutations and promoter methylations of the human RAD5 ortholog, Helicase-Like Transcription Factor (HLTF), are observed in hepatocellular carcinoma (Zhang et al. 2013; Dhont et al. 2016). Mutations in PRKCSH and GANAB, human orthologs of GTB1 and ROT2, are linked to polycystic liver disease (Porath et al. 2016; Perugorria and Banales 2017). The CKB2 ortholog, CSNK2B (Zhang et al. 2015; Chua et al. 2017; Dotan et al. 2001), is over-expressed in several liver cancers and therapeutics are currently in clinical trial (Gray et al. 2014; Li et al. 2017; Trembley et al. 2017). It is tempting to speculate that over-expression of CSNK2B also confers AFB1 resistance.

Human homologs of other yeast genes have been correlated to the etiology and progression of other cancers, including colon and renal cancer. These include the human homolog for TRM9, ALKB8, and the human homolog for TMA20, MCT1, which can complement translation defects of tma20 mutants and has been implicated in modulating stress (Herbert et al. 2001) and double-strand break repair (Hsu et al. 2007). MCT-1 overexpression and p53 is noted to lead to synergistic increases in chromosomal instability (Kasiappan et al. 2009). Heterozygous germline mutations of fumarate hydratase (FH) predispose for hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (Lehtonen et al. 2006). In both mammalian and yeast cells, FH participates in double-strand break repair (Leshets et al. 2018) and may thus suppress genetic instability.

In summary, we profiled the yeast genome for AFB1 resistance and identified novel genes that confer resistance. The novel genes included those involved in tRNA modifications, RNA translation, DNA repair, protein degradation, and actin reorganization. Genes that function in DNA damage response and DNA damage tolerance were over-represented, compared to the yeast genome. We suggest that the CSM2 (SHU complex) functions to promote error-free replication of AFB1-asociated DNA damage, and it will be interesting to determine whether mammalian orthologs of the SHU complex function similarly.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge William Burhans for his initial encouragement and support, and grants from the National Institutes of Health: R21ES1954, F33ES021133, and R15ES023685-03. We would like to thank Chris Vulpe for his gift of the pooled BY4743 library and guidance, Mingseng Sun for initiating work on AFB1-induced recombination, Jonathan Bard for bioinformatics expertise and valuable assistance in data processing, and Adam Smith and Akaash Kannan for technical contributions. Additional help was provided by Michael Dolan and Kevin Lin with bioinformatics.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25387/g3.12895313.

Communicating editor: G. Brown

Literature Cited

- Aggarwal M., and Brosh R., 2012. Functional analyses of human DNA repair proteins important for aging and genomic stability using yeast genetics. DNA Repair (Amst.) 11: 335–438. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseyev O., Hamm M. L., and Essigmann J. M., 2004. Aflatoxin B1 formamidopyrimidine adducts are preferentially repaired by the nucleotide excision repair pathway in vivo. Carcinogenesis 25: 1045–1051. 10.1093/carcin/bgh098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici M., Cecarini V., Pettinari A., Bonfili L., Angeletti M. et al. , 2007. Binding of aflatoxins to the 20S proteasome: effects on enzyme functionality and implications for oxidative stress and apoptosis. Biol. Chem. 388: 107–117. 10.1515/BC.2007.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G. et al. (Editors), 1995. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, Vol. 2, pp. 15.0.1–15.1.9. John Wiley & Sons, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Baertschi S. W., Raney K. D., Stone M. P., and Harris T. M., 1988. Preparation of the 8,9-Epoxide of the Mycotoxin Aflatoxin B1: The Ultimate Carcinogenic Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110: 7929–7931. 10.1021/ja00231a083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barski O. A., Tipparaju S. M., and Bhatnagar A., 2008. The aldo-keto reductase superfamily and its role in drug metabolism and detoxification. Drug Metab. Rev. 40: 553–624. 10.1080/03602530802431439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barz T., Ackermann K., Dubois G., Eils R., and Pyerin W., 2003. Genome-wide expression screens indicate a global role for protein kinase CK2 in chromatin remodeling. J. Cell Sci. 116: 1563–1577. 10.1242/jcs.00352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler J., Klein I., Schmidt C., Kallas M., Thomson E. et al. , 2012. The conserved Bud20 zinc finger protein is a new component of the ribosomal 60S subunit export machinery. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32: 4898–4912. 10.1128/MCB.00910-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard L. L., and Massey T. E., 2006. Aflatoxin B1-induced DNA damage and its repair. Cancer Lett. 241: 174–183. 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley U., Dyavaiah M., Patil A., Rooney J. P., DiRenzo D. et al. , 2007. Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications link translation to the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell 28: 860–870. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabucci U., Colavecchia L., Danieli P. P., Basiric Ã., Lacetera N. et al. , 2011. Aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 affect the oxidative status of bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 25: 684–691. 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]