Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii (Aba) is an emerging opportunistic pathogen associated to nosocomial infections. The rapid increase in multidrug resistance (MDR) among Aba strains underscores the urgency of understanding how this pathogen evolves in the clinical environment. We conducted here a whole-genome sequence comparative analysis of three phylogenetically and epidemiologically related MDR Aba strains from Argentinean hospitals, assigned to the CC104O/CC15P clonal complex. While the Ab244 strain was carbapenem-susceptible, Ab242 and Ab825, isolated after the introduction of carbapenem therapy, displayed resistance to these last resource β-lactams. We found a high chromosomal synteny among the three strains, but significant differences at their accessory genomes. Most importantly, carbapenem resistance in Ab242 and Ab825 was attributed to the acquisition of a Rep_3 family plasmid carrying a bla OXA-58 gene. Other differences involved a genomic island carrying resistance to toxic compounds and a Tn10 element exclusive to Ab244 and Ab825, respectively. Also remarkably, 44 insertion sequences (ISs) were uncovered in Ab825, in contrast with the 14 and 11 detected in Ab242 and Ab244, respectively. Moreover, Ab825 showed a higher killing capacity as compared to the other two strains in the Galleria mellonella infection model. A search for virulence and persistence determinants indicated the loss or IS-mediated interruption of genes encoding many surface-exposed macromolecules in Ab825, suggesting that these events are responsible for its higher relative virulence. The comparative genomic analyses of the CC104O/CC15P strains conducted here revealed the contribution of acquired mobile genetic elements such as ISs and plasmids to the adaptation of A. baumannii to the clinical setting.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, comparative genomics, multi-drug resistance, carbapenem resistance, virulence factors, blaOXA-58

Data Summary

The authors confirm all supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through the Supplementary Material (available in the online version of this article).

Impact Statement.

Acinetobacter baumannii is an ESKAPE opportunistic pathogen cause of healthcare-associated infections worldwide. The majority of infections are caused by strains belonging to a limited number of globally spread clonal complexes (CC), exhibiting multidrug resistance (MDR) including to the last-resort carbapenems. MDR, is a main determinant of A. baumannii success in the nosocomial environment, and the molecular basis of its dissemination represents a research priority. Also, the A. baumannii traits enabling infection and persistence in the clinical setting are poorly resolved, particularly among the less-studied CC. Here, we conducted whole-genome sequence comparative analysis of three phylogenetically and epidemiologically related MDR A. baumannii strains of the CC104O/CC15P prevalent in South America, displaying different carbapenem-resistance phenotypes. We aimed to uncover the genetic events involved in their adaptation to the local clinical environment. This analysis revealed that different mobile genetic elements such as resistance plasmids and insertion sequences cooperatively contribute to genomic remodelling, thus securing adaptation and subsequent persistence of infective strains. A deep understanding of the strategies used by this pathogen to escape from antimicrobial treatment and host defenses is crucial for the adoption of measures aimed to limit its further dissemination.

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii (Aba) nowadays represents an important cause of infections in healthcare institutions worldwide generally affecting immunocompromised and severely injured patients [1–3]. Infections due to Aba, rarely reported before the 1970s, have dramatically increased during the last three decades paralleling the global spread of a limited number of epidemic clonal complexes (CC) displaying multidrug resistant (MDR)-phenotypes, and from which CC2 and CC1 are the best characterized lineages, and conforming thus the international clone (IC) II and I, respectively [2, 4]. A most worrisome problem in the actuality is the rapidly increasing resistance to last-resort carbapenems among Aba strains of the different CC [1–3, 5]. Aba carbapenem resistance arises from different factors that encompass as the main cause the acquisition of carbapenemase genes belonging to different carbapenem-hydrolysing class D β-lactamases (CHDL) classes including bla OXA-23, bla OXA-58 and bla OXA24/40, added to reductions of permeability due to the mutation of specific outer-membrane (OM) channels and efflux pumps [5–10]. The analysis of the origin and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AR) genes among MDR pathogens constitutes a research priority [11]. In this context, the molecular basis of resistance acquisition among Aba strains, and in particular among the less studied CCs, remains poorly resolved.

It is generally thought that Aba pathogenicity results from the combination of a remarkable ability to survive unfavourable environmental conditions, added to a high genomic plasticity and ability to acquire genes by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [3, 12–14]. Most Aba clinical strains invariably contain many acquired mobile genetic elements (MGE) of strong adaptive significance, including different plasmids and chromosomally located resistance islands (RI), encompassing several transposons and integrons, which play pivotal roles in both antimicrobial and heavy-metal ion resistances [2, 12, 15–18]. Furthermore, other traits that might be beneficial for survival in the host are carried by MGEs, including virulence factors, detoxifying mechanisms and genes for secondary metabolism pathways [2]. In addition, these strains carry a large repertoire of insertion sequences (ISs) capable not only of mediating gene disruptions but also large genome rearrangements, thus providing bacterial cells with an outstanding ability to rapidly respond to new environmental challenges contributing to a rapid adaptation to the clinical environment [19, 20].

AR derived from gene acquisition and/or mutation is generally considered a main determinant of the success of particular Aba strains in the nosocomial environment [2, 3, 5]. In contrast, virulence traits and the pathogenic potential of certain Aba lineages are less well defined [3, 5, 21]. As in other pathogens, a number of macromolecular structures have been associated to virulence including a capsular polysaccharide that protects cells from host complement killing and phagocytosis, a biofilm related to adhesion and motility, OM proteins (OMP) such as OmpA involved in host-cell recognition, internalization and pathogenicity, a lipooligosaccharide influencing host innate immune responses, iron capture systems, phospholipases C and D [3, 5, 22]. Notably, most genes related to the above functions are encoded in the core genome of the Aba clinical strains analysed, regardless of their affiliation to particular CCs or to sporadic isolates [2]. It thus remains an open question whether pathogenicity may arise by a differential regulation of virulence genes depending on the CC lineage (or even on internal lineages inside a given CC), on the polymorphic differences in shared virulence genes, or a combinatorial effect of multiple genes [2].

Whole-genome-sequence (WGS) comparisons have become a common place in examining strain-to-strain variability and in comparing pathogenic strains with environmental isolates, allowing the identification of underlying genetic determinants and mechanisms responsible for the observed phenotypic dissimilarities [23, 24]. When applied to Aba, WGS approaches have shed light on the mechanisms of acquisition and evolution of AR, population dynamics and epidemiology [2, 5, 23]. WGS have also illustrated extensive and redundant AR gene carriage and provided direct evidence of HGT and homologous recombination between Aba strains since their entry into the hospital, facilitating the adaptation of particular lineages to the prevailing clinical conditions [25, 26]. We have previously characterized the OMP variability among three genotypically closely related MDR Aba strains displaying different β-lactam susceptibility phenotypes, Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825, which were isolated from patients hospitalized in the Hospital de Emergencias Clemente Alvarez (HECA) of Rosario, Argentina [7, 8, 27, 28]. Ab244, originally characterized as ST39 [8] and re-designated ST104 following the MLST Oxford scheme [21], represents a sporadic strain isolated in 1997. This strain showed resistance to β-lactams such as ceftazidime, which constituted the antibiotic therapy employed for infections associated by MDR Aba at the hospital at this period. Ab242 is the representative strain of a carbapenem-resistant (CarbR) outbreak that occurred in the same year, and which followed the introduction of imipenem (IPM) therapy for the treatment of MDR bacterial infections [27]. The isolates of this clone showed either intermediate (16 µg ml−1) or resistant (≥32 µg ml−1) MIC values to ceftazidime [29]. Finally, Ab825 is a sporadic strain showing both ceftazidime and carbapenem resistance, and was isolated a year after the outbreak was controlled [27]. Our previous studies [8, 28] indicated substantial allelic variability at the level of the carO gene, encoding the second most abundant OMP of the Aba OM involved in IPM uptake. Ab244 and Ab242 harbour different carO alleles, namely carO variant II and carO variant III alleles, respectively [8]. In contrast, Ab825 carries a disrupted carO variant III gene due to the natural insertion (and selection) of an ISAba825 element [6].

In this work we performed a WGS comparative characterization of these three MDR Aba strains to evaluate in more detail their genetic variability and underlying causes, in an attempt to understand the mechanisms of adaptation and persistence of these genetically and epidemiologically closely related strains in the hospital environment.

Methods

A. baumannii strains

Ab244, Ab242 and Ab825 (Table 1) are epidemiologically related MDR Aba strains from clinical specimens obtained from in-patients of the HECA. These three strains formed a clonal group as judged by a combination of genotypic procedures including OD-PCR, repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR (REP-PCR), and PFGE [27].

Table 1.

General traits and genomic features of A. baumannii strains under study

|

Strains |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ab242 |

Ab244 |

Ab825 |

|

|

General traits*1 |

|||

|

Former designation/alias |

24 214 |

24 474 |

825 |

|

Isolation date |

1997-10-01 |

1997-10-01 |

1999-03-01 |

|

Specimen/source |

ascitic fluid |

blood |

wound |

|

Carbapenem susceptibility Phenotype |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

Resistant |

|

Genomic parameters*2 |

|||

|

Depth of coverage |

47.6x |

25.9x |

103.0x |

|

Number of contigs |

107 |

99 |

99 |

|

Estimated size (Mbp) |

4 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

|

GC content (%) |

39.2 |

39.1 |

39.1 |

|

Number of CDSs |

3722 |

3659 |

3614 |

|

Number of tRNA genes |

61 |

64 |

63 |

|

Number of rRNA operons |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Prophage regions |

4 |

3 |

4 |

|

ISs |

12 |

10 |

45 |

|

Complete plasmids |

3 (accession numbers KY984045.1, KY984046.1 And KY984047.1) |

1 (accession number MG520098) |

2 (accession numbers MG100202.1 And MG100203.1 |

|

BioProject |

PRJNA398382 |

PRJNA398382 |

PRJNA398382 |

|

Biosample |

SAMN07509424 |

SAMN08028494 |

SAMN07573381 |

|

Accession |

|||

*1 See reference 27.

*2 Based on NCBI Prokaryotic annotation pipeline.

Genomic sequencing, assembly and annotation

Ab242 and Ab244 genomic DNA was isolated using a commercial kit (Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit, Promega), following the manufacturer’s protocols. The corresponding genomic sequences were obtained using a paired-end strategy with a 454 pyrosequencer (Life Science Corporation) at the Instituto de Agrobiotecnología Rosario (INDEAR, Argentina). Quality-filtered reads were de novo assembled using Newbler v2.5.3. Ab825 genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The genomic sequence was obtained in this case using a paired-end strategy using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer at the National Institute of Health (Lisbon, Portugal). Reads were subjected to quality assessment and further assembled using Velvet version 1.2.10. The de novo assembly process was optimized using the Velvet Optimiser script version 2.2.5.

For each genome, the resulting contigs were ordered and oriented with Mauve [30] using the Aba ATCC17978 genome as a reference (CP012004). The replication origins (oriC) were predicted by OriFinder [31]. All three assembled genome sequences were annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic annotation pipeline.

Presence of mobile genetic elements in the genomes was investigated by the following online tools and/or open-access database and manual examinations: IS Finder [32] for insertion sequence (IS) elements. IS insertion sites were inferred from draft genome assemblies by identifying fragments of the inverted repeats corresponding to these mobile elements at contig edges. Putative prophage sequences were identified by phaster analysis [33]. Genes encoding AR were identified with ResFinder 2.1 [34]. Assignments of sequence types (STs) for the three strains under study were done using the sequences of the housekeeping genes employed by each scheme [35].

In order to evaluate the occurrence and distribution of the various iron uptake systems reported for Aba, we first downloaded the complete genomes of 132 publicly available strains. We then performed blastN searches using as query the nucleotide sequences of the iron uptake clusters from Aba ACICU strain [36], with a minimal coverage length and sequence identity of 80 and 90 %, respectively. An identical approach was followed when analysing the presence of the cpaA gene, but in this case we used the nucleotide sequence of strain AB031 as query.

A. baumannii Ab244 plasmid assembly and analysis

A contig-encoding plasmid sequences was assembled from the pyrosequencing data derived from Ab244 strain. The circular structure of this plasmid was then verified by gap closure of contigs using PCR with specifically designed primer pairs (Table S1, Fig. S3, available in the online version of this article). All amplicons were subjected to sequence verification at the Sequencing Facility of Maine University.

Galleria mellonella infection assays

G. mellonella larvae were purchased from Sud Est Appats (http://www.sudestappats.fr/) and were used the day after arrival. Groups of 20 randomly picked larvae were used for each assay condition. Infections were performed as previously described [37]. Survival curves were plotted using prism software, and comparisons in survival were calculated using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test.

Results

General traits and genomic analyses of strains Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825

Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 (Table 1) are epidemiologically related MDR Aba strains obtained from inpatients hospitalized in HECA, Rosario, Argentina [27]. The three strains were subjected to WGS and subsequent analysis of the sequencing data, and a summary of the general genomic features of each of these strains is provided also in Table 1.

WGS analyses indicated that the Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 genomes were 4 000 608, 3 943 341 and 3 900 868 bp in length, respectively, with a G+C content of 39.1–39.2 % (Table 1). The obtained sizes and G+C contents therefore matched the reported averages for the genomes of the Acinetobacter spp., i.e. 3.87 Mb and 39.6 %, respectively [12]. Each of these strains contains only one chromosome, and house one to three plasmids depending on each strain as judged by the WGS analysis (Table 1).

The assignments of STs following the Oxford (STO) or Pasteur (STP) MLST schemes [21] were done using the sequences of housekeeping genes derived from the WGS data . These comparisons assigned, in the Oxford scheme, Ab244 and Ab242 both to ST104O and Ab825 to ST692O (Table S2). Since ST692O and ST104O differ only in the sequence of the gpi allele (Table S2), all strains were ascribed to the CC104O [21]. In turn, all of the above strains shared the same allelic profile in the Pasteur scheme, ST15P, thus conforming the CC15P (Table S2). These assignments are thus in full agreement with the equivalence between the two Aba MLST schemes [21]. A detailed analysis of the MLST database revealed that almost 78 % (49/63) of the strains assigned to CC104O/CC15P were isolated in South America (Table S2). This CC has received lower attention as compared to the main Aba CC1 and CC2, but it has been associated to the dissemination of CHDL genes including bla OXA-23, bla OXA-58 and bla OXA-143 not only in South America but also in a number of European and Asian countries [21, 38, 39]. Moreover, to our knowledge no WGS comparative analysis of CC104O/CC15P strains has been reported to date.

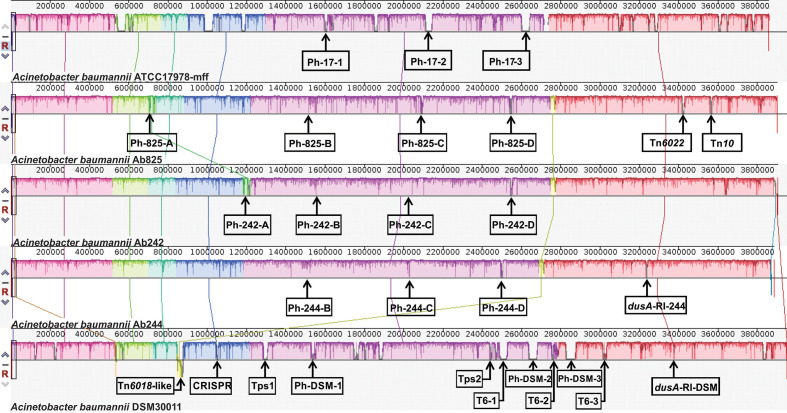

Comparative analysis of Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 chromosomes

A comparative analysis was next performed among the chromosomes of strains Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 (Fig. 1). Other Aba chromosomes included in these comparisons were those of the reference clinical strain ATCC17978 [40] and the pre-antibiotic era environmental strain DSM30011 [23]. The two latter strains are generally susceptible to most antimicrobials and were isolated by the middle of last century [23], thus providing a frame for the evaluation of major genome rearrangements among the strains under study. As seen in Fig. 1, a general shared synteny was found between all of the chromosomes of the analysed Aba strains, except for five regions including: (1) a Ph prophage region (Ph-A) common to Ab825 and Ab242 (Ph-825-A and Ph-242-A, respectively), although the location of insertion in the chromosome of each of these strains was different; (2) a Tn6018-like element common to Ab242, Ab244, Ab825 and also to DSM30011, but inserted in a different chromosomal position in each of the CC104O/CC15P strains and positioned in an inverted orientation in the DSM30011 chromosome; (3) a similar RI interrupting a tRNA dyhidrouridine synthase gene (dusA) present in Ab244 and DSM30011; (4) a second copy of a Tn6022 located in a different chromosome location in Ab825; and (5) a Tn10 element carrying tetracycline resistance determinants also in Ab825 only (see below for details).

Fig. 1.

Linear comparison of the genomes of A. baumannii strains ATCC17978, Ab825, Ab242, Ab244 and DSM30011 inferred using Mauve. Each block corresponds to a DNA fragment of the chromosome and is distinctively coloured for clarity. The degree of conservation is indicated by the vertical bars inside the blocks. Their position relative to the genome line denotes co-linear and inverted regions. Putative prophages (Ph/strain-number; seeTable 3 for details) are displayed for all strains. Two regions usually associated with antimicrobials resistance (Tn6022 and Tn10) are shown for strain Ab825 (see text for details). Regions encoding a Tn6018-like element, a CRISPR-cas cluster, two-partner systems (Tps-1 and 2) and type-6 secretion-system-related genes (T6-1 to 3) are indicated for DSM30011 genome [23]. A resistance island inserted into the dusA gene is present in Ab244 and DSM30011 chromosomes.

It is worth noting the conspicuous absence in all three CC104O/CC15P strains of gene clusters encoding defensive mechanisms against biological aggressors such as: (1) genes associated to type-6 secretion systems (T6SS). In contrast, a complete T6SS main cluster and several toxin-encoding genomic islands are present in each of the ATCC17978 and DSM30011 chromosomes [37, 41]; (2) a CRISPR-cas anti-phage system, which is missing also in ATCC17978 but is present in DSM30011 [37]; (3) contact-dependent inhibition (CDI) type 5 secretion systems (T5SS) of the Two-partner system (Tps) subclass [42], absent in ATCC17978 as well. Remarkably, two different T5SS clusters are present in the DSM30011 chromosome (locus tag DSM30011_05955–60 and locus tag DSM30011_11640–45, respectively) [43] probably reflecting the environmental origin of this strain and the concomitant selection pressures [23].

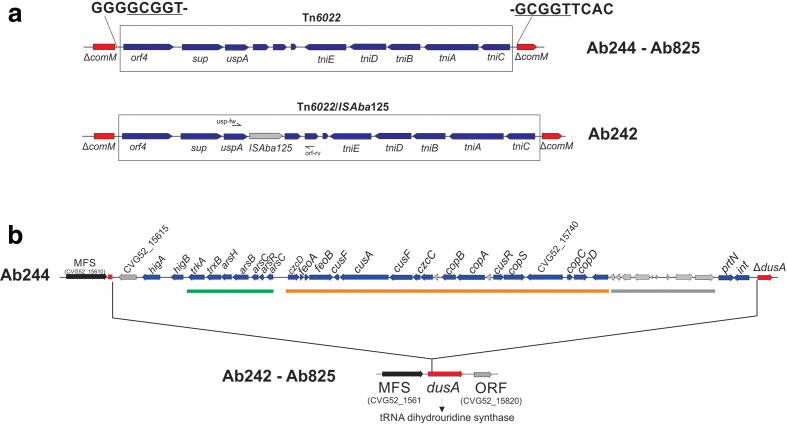

Resistance islands

Aba RI are important vehicles for the accumulation of different antimicrobial (AbaR) and heavy-metal ion-resistance genes [44]. The comparisons of the genomic sequences of 249 Aba strains indicated four well-defined hot-spots for AbaR insertions including comM, pho, astA, and an acetyl transferase (acetylT) gene [16]. In Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 chromosomes (Fig. 2a), the comM gene was found interrupted by the insertion of a Tn6022 composite transposon [45]. Tn6022 constitutes the basic backbone of AbaR4, a RI in which a Tn2006 transposon carrying a bla OXA-23 carbapenemase gene is inserted, and which is carried mostly by strains of the widely disseminated IC II [45–48]. The observation above that Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 contain within the comM gene a single Tn6022 element lacking resistance genes and inserted in all cases at an identical site (Fig. 2a) therefore indicated that its acquisition occurred most likely in a common ancestor. Moreover, that carbapenem resistance in Ab242 and Ab825 resulted from other mechanism(s). Of note, in the Tn6022 element carried by Ab242 a complete ISAba125 element was additionally located in the intergenic region between uspA and a hypothetical gene (locus tag CJU83_17765), thus suggesting that its acquisition occurred independently in this strain. In addition, a second Tn6022 copy was found in the Ab825 chromosome (Fig. 1), in this case disrupting an asnA l-asparaginase gene (locus tag CLM70_16865) in what constitutes a previously unreported location for this transposon.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representations of the genomic islands interrupting comM and dusA in the A. baumannii clinical strains under study. (a) Tn6022 elements found interrupting the comM gene in the three strains under study (see Table 2 for details). The direct repeat generated at the site of integration is shown enlarged and underlined. In the Tn6022 element found in Ab242, an additional ISAba125 element was localized downstream of the uspA gene. The sites of hybridization of the pair of primers (see Table S1) employed to corroborate this insertion by PCR amplification analysis is shown. (b) Genomic island interrupting the dusA gene in the Ab244 strain (see Table 2 for details). Copper and arsenic ion-resistance clusters are underlined by green and orange bars, respectively. Genes encoding hypothetical phage proteins (grey arrows) are underlined by a grey bar. For comparisons, the intact dusA gene and its flanking genes found in the chromosomes of both Ab242 and Ab825 strains are shown below.

Aba strains usually encode diverse gene clusters encoding systems involved in the detoxification of noxious compounds [49]. Interestingly, the three strains studied here carry a Tn6018-like transposon inserted in all of them at the same genomic position and carrying resistance genes to heavy-metal ions (Table 2). This element was previously identified in a reduced number of Aba strains isolated from the environment (DSM30011) and also from the clinical setting (AB031 and ATCC19606) [23]. This RI, which is missing in strain ATCC17978, is located in a different genomic locus and in an opposite orientation in the DSM30011 chromosome (Fig. 1). We previously reported [23] the presence of a 33 kbp RI encoding resistance to heavy-metal ions in DSM30011 interrupting the dusA gene (DSM30011_16220). This spot represents a common integration site for this kind of genetic element in Aba [49, 50]. The RI identified in DSM30011 includes arsenate and heavy-metal-ion detoxification systems such as ars, czc and cop, as well as genes putatively involved in iron ion transport (feoAB) [23]. A similar region was also detected at the Ab244 dusA locus (Fig. 2B and Table 2). Interestingly, this RI contains three additional genes, two of them encoding a HigAB toxin-antitoxin module [49, 50], and the other a Beta protein, which acts as an antitoxin of the Gop toxin that prevents host cell killing by the T4 bacteriophage [51]. These genes may serve to stabilize this RI in the Ab244 genome in cells transiting under non-selective environments.

Table 2.

Resistance islands

|

Toxic compounds- Resistance islands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Name |

Strain |

Position (bp) |

Length (kb) |

Integrase locus tag |

Integration site |

Upstream of integration site locus tag |

Downstream locus tag |

|

Tn6018-like |

Ab242 |

2742324–2778290 |

36.0 |

CJU83_ 13 560 |

tRNA-Ser-TGA |

CJU83_13360 NLPA lipoprotein |

CJU83_13570 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase |

|

Ab244 |

2683153–2719121 |

36.0 |

CVG52_ 13 180 |

CVG52_12975 NPLA lipoprotein |

CVG52_13190 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase |

||

|

Ab825 |

2739913–2776075 |

36.1 |

CLM70_ 13 810 |

CLM70_13610 NPLA lipoprotein |

CLM70_13820 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase |

||

|

DSM 30 011 |

843472–874327 |

30.8 |

DSM30011_04155 |

DSM30011_03930 transcription elongation factor GreB |

DSM30011_04160 SgcJ/EcaC family oxidoreductase |

||

|

dusA-RI |

Ab244 |

3233058–3273869 |

40.8 |

CVG52_ 15 810 |

dusA |

CVG52_15610 MFS transporter |

CVG52_15820 |

Mobile genetic elements in Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 genomes

Prophages

Bacteriophages provide a source of genomic variability in Aba [52]. The prediction of bacteriophage sequences in the clinical strains analysed here uncovered the presence of four prophages in the chromosomes of each Ab242 and Ab825, and three in Table 3 Ab244. Prophages inserted at the same chromosomal location in the three strains (i.e. Ph-B, C and D, Fig. 1, Table S3) showed nucleotide identities higher than 99 % and identical sequences for hallmark genes such as integrase, terminase, as well as for phage capsids and tails. Moreover, their integration sites are in concordance with previously reported hot-spots for phage integration in the Aba chromosome [16]. In contrast, prophages Ph-242-A and Ph-825-A, which were located only in strains Ab242 and Ab825, displayed different integration sites in the corresponding chromosomes (Fig. 1). From them, Ph-825-A was found in a tRNA-Arg gene (Table 3), an integration site already described in other Aba strains [16]. Ph-242-A, in turn, was also found inserted into a tRNA-Arg gene located in a different chromosome region when compared to Ph-825-A. In addition, Ph-242-A insertion generated a 15 bp-deletion at the 3′-end of the target tRNA-Arg gene (Table 3).

Table 3.

Putative prophages*

|

Strain |

Name |

Length (kb) |

Nucleotide position (bp) |

Integrase locus tag |

Integration site |

Upstream locus tag |

Downstream locus tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ab242 |

Ph-242-A |

48.5 |

1174360–1222933 |

CJU83_ 05530 |

tRNA-pseudo-Arg-CCG |

CJU83_05525 ABC type transporter |

CJU83_05880 hypothetical protein |

|

Ph-242-B |

53.6 |

1519370–1573046 |

CJU83_ 07300 |

IR† (hypothetical protein-MFS transporter) |

CJU83_07295 hypothetical protein |

CJU83_07715 MFS Transporter |

|

|

Ph-242-C |

30.6 |

2076444–2107079 |

CJU83_ 10 280 |

IR† (malG-zapE) |

CJU83_10090 Malate synthase G |

CJU83_10285 ZapE (cell division protein) |

|

|

Ph-242-D |

43.5 |

2540407–2583982 |

CJU83_ 12 385 |

tRNA-Gly-GCC |

CJU83_12375 cysteine-tRNA ligase |

CJU83_12630 hypothetical protein |

|

|

Ab244 |

Ph-244-B |

53.7 |

1476585–1530289 |

CVG52_ 06995 |

IR (hypothetical protein-MFS transporter) |

CVG52_06990 hypothetical protein |

CVG52_07415 MFS transporter |

|

Ph-244-C |

29.2 |

2027692–2056979 |

CVG52_ 09970 |

IR (malG-zapE) |

CVG52_09790 Malate synthase G |

CVG52_09975 ZapE (cell division protein) |

|

|

Ph-244-D |

33.3 |

2488724–2522040 |

CVG52_ 12 065 |

tRNA-Gly-GCC |

CVG52_12055 cysteine-tRNA ligase |

CVG52_12250 hypothetical protein |

|

|

Ab825 |

Ph-825-A |

54.6 |

718987–773665 |

CLM70_ 03610 |

tRNA-Arg-CCT |

CLM70_03370 HchA, protein deglycase |

CLM70_03985 Aminoacid permease |

|

Ph-825-B |

62.3 |

1546982–1609384 |

CLM70_ 07550 |

IR (hypothetical protein-MFS transporter) |

CLM70_07545 hypothetical protein |

CLM70_08115 MFS transporter |

|

|

Ph-825-C |

41.3 |

2100618–2141947 |

CLM70_ 10 600 |

IR (malG-zapE) |

CLM70_10350 Malate synthase G |

CLM70_10605 ZapE (cell division protein) |

|

|

Ph-825-D |

40.3 |

2573757–2614071 |

CLM70_ 12 695 |

tRNA-Gly-GCC |

CLM70_12685 cysteine-tRNA ligase |

CLM70_12885 hypothetical protein |

*According to phaster predictions.

†IR; intergenic region.

Further bioinformatic analysis indicated that, with the only exception of Ph-244-D, all of the other prophage sequences described above encode for complete prophage components (Table S3).

Insertion sequences

The identity and number of IS copies present in the genomes of Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 was predicted by bioinformatic analysis (Table S4), and the inferred ISs were then manually curated. Remarkably, the Ab825 genome contains the larger variety and number of ISs with a total of 44, whereas only 14 and 11 IS copies were found in Ab242 and Ab244, respectively. Not only the number of ISs found in Ab825 is significantly higher than the reported average of 33 copies per Aba genome [19], but the diversity of IS families found in this genome is also high as well (Table S4). The most abundant IS elements found in the three Aba genomes analysed are intrinsic to the Acinetobacter genus (ISAba-type) and are generally present in multiple copies [19]. Among them the most prevalent is ISAba125, with 13 copies scattered throughout the whole Ab825 genome (Table 4).

Table 4.

Insertion sequence content of the A. baumannii strains under study*

|

Location |

IS type |

Strain |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ab242 |

Ab244 |

Ab825 |

||

|

Chromosomal contigs |

ISAba125 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

IS10 |

– |

– |

9 |

|

|

ISAba43 |

1 |

– |

6 |

|

|

ISAba31 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

ISAba42 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

ISAba1 |

– |

1 |

3 |

|

|

ISAba26 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

ISAba825 |

– |

– |

1 |

|

|

ISour |

1 |

2 |

– |

|

|

ISVsa3 |

1 |

1 |

– |

|

|

IS15DII |

– |

1 |

– |

|

|

Complete plasmids† |

ISAba125 |

2 |

– |

2 |

|

IS26 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

ISAba3 |

2‡ |

– |

2‡ |

|

|

ISAba825 |

1 |

– |

1 |

|

|

|

Total |

14 |

11 |

44 |

Of note, two novel ISs one of 1320 bp and the other of 2655 bp, were identified in the genomes of the clinical strains under study, and the corresponding sequences were submitted to the ISSaga database from ISfinder [32]. These new ISs were assigned the designations ISAba42 and ISAba43, respectively (Fig. S1). ISAba42 belongs to the IS256 family, and ISAba43 to the ISL3 family. ISAba42 carries a transposase gene encoding a protein of 403 amino acids with a 95 % of similarity to the ISEc39 transposase (CP001855) including a typical MULE domain [53] associated to Escherichia coli strain S43 [54]. IR-R and IR-L inverted repeats of 24/28 bp at the ends of ISAba42 were identified, as well as a 8 bp direct repeat (DR) at the site of insertion (Fig. S1). ISAba42 was only detected in the Acinetobacter sp. ACNIH1 plasmid pACI-3bd5 and in the chromosome of Acinetobacter sp. NCu2D-2. Remarkably, this IS was found interrupting a RTX-family toxin gene in the three analysed strains (see below).

In the case of ISAba43, six copies were found in the chromosome of strain Ab825 and only one in Ab242. ISAba43 bears two genes, the first encoding a drug resistance transporter of the Bcr/CflA subfamily (421 aa) and the second a DDE transposase (401 aa) displaying 69 % amino acid identity with the ISAeme19 transposase [55]. The IR-R and IR-L inverted repeats of this IS are 65 bp long each, and its insertion generated a direct repeat (DR) of 8–10 bp in length at the target site (Fig. S1). ISAba43 is present in the other 19 strains of the Acinetobacter genus.

It is worth noting that ISAba43 is the third in prevalence (n=6; Table 4) in strain Ab825, indicating a relatively relevant role in the remodelling of this genome.

Plasmids

Plasmids are the most frequent vehicles directly implicated in the acquisition of AR resulting from lateral gene transfer both intra- and inter-species [56]. Ab242 strain contains three plasmids (pAb242_9, pAb242_12, and pAb242_25) [57], Ab825 strain contains two plasmids (pAb825_36 and pAb825_12), and the carbapenem-susceptible (CarbS) Ab244 strain houses only a single plasmid (pAb244_7) (Table 1).

Ab242 and Ab825 strains display clinical resistance to carbapenem β-lactams including imipenem and meropenem (Table S5). The source of carbapenem resistance in these two strains is the presence of similar Rep-3 resistance plasmids (pAb242_25 and pAb825_36) containing identical adaptive modules of ~9.5 kbp carrying a bla OXA-58 gene within a defective Tn3, and in which the insertion of an ISAba825 in the ISAba3 copy located upstream of bla OXA-58 resulted in its overexpression [9, 57]. In addition, this adaptive module also encompasses a TnaphA6 composite transposon inserted downstream of the bla OXA-58 gene and conferring amikacin resistance to the Acinetobacter host (Table S5) [57]. Of note, the module is bordered by several sites potentially recognized by the XerC/D site-specific tyrosine recombinases of the host (XerC/D-sites) [57]. Moreover, we recently demonstrated that some XerC/D-sites present in Ab242 plasmids can actually constitute active pairs proficient for site-specific recombination (SSR) mediating plasmid fusions and resolutions, and postulated that these and subsequent structural rearrangements may facilitate the dissemination of resistance structures bordered by XerC/D-sites [57].

In the above context, comparative sequence analysis between pAb244_7 (Fig. S2) housed by Ab244 and Ab242 plasmids [57] revealed an extensive sequence identity between pAb244_7 and pAb242_9 (from the latter strain) also lacking AR genes (Fig. S3). pAb244_7 has a length of 7965 bp and contains 13 ORFs, and none of them encoding antimicrobial resistant determinants (Fig. S2). The main difference between these two plasmids is the additional presence of an approximately 1.3 kbp region in pAb242_9 carrying a relBE toxin-antitoxin system and a fdx (ferredoxin) gene (Fig. S3). Of note, this region is also bordered by two directly oriented XerC/D-sites designated no. 14 and no. 16, respectively (Fig. S3). The presence of a XerC/D-site in an equivalent position in pAb244_7 (no. 14) strongly suggests that the acquisition of this 1.3 kbp fragment by pAb242_9 was also the consequence of structural rearrangements subsequent to a SSR event mediated by the XerC/D system. XerC/D-sites present in Acinetobacter plasmids have in fact been implicated in the acquisition of different modular structures including not only AR genes but also toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, heavy-metal-ion resistance genes, etc [18, 57–59]. The observations of this work thus provide further clues on the contribution of XerC/D-mediated SSR events to the structural remodelling of Aba plasmids and the dissemination of modular structures bordered by these sites.

Antimicrobial resistance differences between Ab244, Ab242 and Ab825 strains can be attributed to differences in resistance genes' repertoire or expression

The three analysed strains exhibited resistance to different β-lactams, except for carbapenems, and extended spectrum cephalosporins, quinolones and aminoglycosides (Table S5), thus classifying as MDR. The carbapenem and amikacin resistance phenotypes of Ab242 and Ab825 could be attributed to a plasmid-borne bla OXA-58 and aphA6 genes, respectively. However, the resistance to β-lactams such as ampicillin and cephalosporins, and differential levels of resistance to other antimicrobial classes such as folate synthesis inhibitors and tetracycline (Table S5) prompted us to perform bioinformatic predictions of the antimicrobial gene repertoire in the genome of the studied strains (Table S6). The resistance to ampicillin displayed by the three strains (Table S5) most likely reflects the contribution of different β-lactamase genes in the corresponding chromosomes including bla OXA-51 and bla ADC-25 (encoding a AmpC-type β-lactamase) in all of them, and a bla TEM-1-B in Ab244 (Table S6). The chromosomal bla OXA-51 gene is intrinsic to Aba and a hallmark of this bacterial species [60]. The insertion of ISs upstream bla OXA-51 generating strong promoters is the cause of CarbR phenotypes [61], but this was not the case of the strains analysed here (Table S6). This reinforced the above notion that carbapenem resistance in Ab242 and Ab825 resulted from the acquisition of the bla OXA-58 plasmid-borne gene. In addition, Aba carries a chromosomally encoded AmpC-type bla ADC-25 β-lactamase, and the overexpression of this gene resulting from the upstream insertion of ISAba1 elements providing a strong promoter has been associated to increased cephalosporin resistance [62, 63]. All of the Aba clinical strains analysed here showed resistance to different cephalosporins, with Ab242 showing lower (intermediate) resistance to ceftazidime and cefepime when compared to either Ab244 or Ab825 (Table S5). The higher levels of resistance to these two cephalosporins shown by the two latter strains could be thus attributed to the presence of an ISAba1 copy upstream of bla ADC-25 in the corresponding chromosomes (Table S6). Regarding resistance to folate synthesis inhibitors (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) shown by Ab242 and Ab244 (Table S5), these resistance profiles are in concordance with the presence of the sul2 gene in both strains (CJU83_19430 and CVG52_19110, respectively) [64, 65]. The susceptibility phenotype displayed by Ab825 (Table S5) represents a notable exception when compared to their genetically related strains as well as to other Aba clinical strains [5, 15, 66, 67]. This could be associated to the interruption of the use of these drugs to treat bacterial infections [68]. In turn, the tetracycline-resistant phenotype of Ab825 as compared to the other two strains (Table S5), likely reflects the presence of a Tn10 composite transposon [69] in this strain (Table 2 and Table S6). This transposon, possesses a total of eight genes [four of which have role(s) in tetracycline resistance], and was found inserted in the Ab825 chromosome in the intergenic region between a serine hydrolase gene (CLM70_17480) and a merR transcriptional regulator (CLM70_17535). The fact that this region is intact in both the Ab242 and Ab244 chromosomes suggests that this mobile element was independently acquired by Ab825.

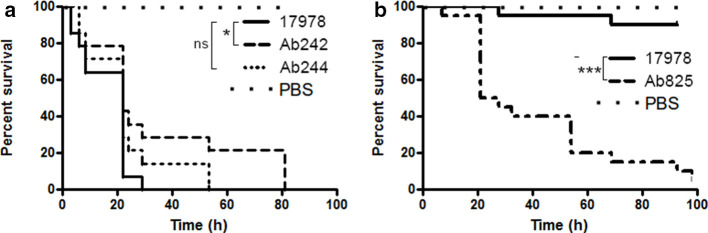

Comparative analysis of the virulence potential of the analysed A. baumannii clinical strains using the G. mellonella larvae insect model

G. mellonella larvae provide us with a reliable model to evaluate/compare the pathogenicity of different Aba strains [41, 70]. In the case of the different clinical strains analysed, and in comparison with ATCC 17978 used as an Aba reference strain, we observed that both Ab244 and Ab242 were significantly less virulent than ATCC17978 at a dose of 106 c.f.u. (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the killing of the larvae was abrupt when Ab825 was assayed at this bacterial load dose indicating a higher virulence for this strain to allow any comparison of virulence (not shown). In fact, when the injected Ab825 bacterial load was lowered tenfold to 105 c.f.u. (Fig. 3b), we consistently observed that this strain killed more efficiently the larvae than all of the other strains tested, including ATCC17978 (Fig. 3b) and Ab242 and Ab244, which for clarity were not included in the figure.

Fig. 3.

G. mellonella lethality assays of the different A. baumannii strains under study. (a) Comparative survival analysis of G. mellonella larvae injected with 106 c.f.u. doses of Ab242 or Ab244 strains. The same dose of the Aba ATCC17978 was also tested as a control reference strain (*P<0.05; n.s.: non-significant). PBS was used as a control. (b) Same, but employing 105 c.f.u. doses of Ab825 or ATCC17978. (***P<0.0001). In all cases the data are representative of three separate survival experiments, each performed with 20 larvae. Survival curves were constructed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by Log-rank analysis.

Identification of persistence and virulence determinants among the analysed A. baumannii strains

Next, we aimed to determine the genomic features that could explain the significant differences in virulence shown above by the analysed strains. Initial homology searches using as queries genes encoding virulence factors [13, 22, 71] over the genomes of the three Aba strains indicated the presence of most of them (Table S7). Some particular cases are hereafter described:

(i) Exopolysaccharides (EPS). Surface polysaccharides play a very important role in Aba pathogenesis [72]. EPS produced by Aba include a capsule and a short version of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen [73, 74], both of which are exposed in the cell surface and are highly immunogenic. However, the composition and structure of both K and O antigens vary considerably between strains, and these differences can substantially modify recognition by host defenses [75]. Our analysis indicated that the K-loci identified in the three MDR strains displayed similar genetic organization, which corresponds to that denominated PSgc12 in the classification of Hu et al. [75] (Fig. S4). A distinctive feature, is the interruption of the cgmA gene located between the pgm (encoding a phosphoglucomutase) and the gne genes (encoding a UDP-NAc-glucose-4-epimerase) by an ISAba31 element (Table S7, Fig. S4). Domain-search analysis indicated that cgmA encodes a hypothetical protein carrying a lipoteichoic acid synthase like domain (cd16015). Notably, and despite the fact that lipoteichoic acids have not been described among Gram-negative bacteria, this gene is widely distributed in both environmental and clinical isolates of Aba [23, 75]. Still, any potential role of cgmA in the capsule synthesis process remains to be determined, and whether its absence confers some selective advantages in the clinical environment. Moreover, an ISAba26 element was detected in the intergenic region between cgmA and gne (Fig. S4).

The detailed analysis of the nucleotide sequences revealed interesting differences between the K-locus of the analysed strains. Firstly, strain Ab825 contains a different variation of the wzx gene. Wzx is in charge of translocating the short oligosaccharide repeat units across the inner membrane and into the periplasm [74]. There is a large sequence polymorphism between Aba Wzx proteins [48, 75], and it is widely accepted that these proteins possess significant substrate specificity, mainly involving the recognition of the first sugar in the repeat unit and also the presence of a side branch [76]. Consequently, the identification of a different wzx allele in Ab825 suggests that the basic oligosaccharide repeat unit in its capsule may differ from that of Ab242 and Ab244. In concordance with this hypothesis, the wagG and wagH genes predicted to code for proteins with sugar-branching activity (Fig. S4, Table S7), are only present in the Ab825 strain.

We then analysed the organization of the OC-locus. Twelve different OC-loci (namely OCL1-OCL12) have been defined on the basis of aminoacid sequence similarity analysis of more than 200 Aba strains [77]. A similar search revealed that each of the three strains analysed possess an OCL7-type locus. These loci displayed comparable gene contents (Table S7) encoding each five different glycosyl transferases, one polysaccharide deacetylase, three hypothetical proteins and one protein carrying a hydrolase domain.

(ii) Iron uptake. Since the ability to acquire iron from the host contributes to Aba virulence [78–80], we analysed the occurrence of different iron-uptake systems in the MDR strains. However, all of them showed five different clusters involved in the acquisition of iron ions (Table S7), including a feoABC cluster responsible for the active uptake of Fe(II) [36]; the acinetobactin cluster directing the synthesis of a widely characterized siderophore displaying a major role in Fe(III) ion scavenging [81]; two additional clusters involved in heme uptake (heme-uptake clusters 2 and 3) [36, 82], and a baumanoferrin gene cluster responsible of the synthesizes of a hydroxamate-type siderophore [36, 83]. To obtain clues on the distribution of the above iron acquisition systems in the general Aba population, we conducted genomic comparative analyses on 128 Aba clinical strains and three of environmental origin, DS002, DSM30011 and NCIMB8209 [23, 24], thus totalizing 132 publicly available genomes. We determined the presence of the five iron-uptake clusters mentioned above in 72 (54.5 %) of the above genomes. Remarkably, 57 (43.2 %) of the remaining strains carry four of these clusters, only lacking the heme-uptake cluster 3. Notably, this cluster is also absent from Aba environmental strains DSM30011 and NCIMB8209 [23]. It is also worth mentioning that Aba DS002, only carry three iron-uptake clusters [24], lacking acinetobactin as well as the heme-uptake cluster 3 [24]. The presence of the five iron-uptake systems in the Ab242, Ab244 and Ab825 strains reinforced the idea that their presence most probably contributed to the adaptation of Aba to the clinical environment [80].

(iii) CpaA. The cpaA gene encodes a metallopeptidase exhibiting the ability to cleave fibrinogen and coagulation factor XII, thus helping deregulate blood coagulation during infection [84]. CpaA, a substrate of the type-II secretion system, was thus proposed as a bona fide virulence factor [13, 85]. Our analysis indicated that all three strains lack the cpaA gene. In this context, the analysis of cpaA presence among the aforementioned genomes of 132 Aba strains showed that only 17 (12.9 %) carry this gene. Interestingly, six of them belong to ST10P and another three to ST23P. This indicates that this virulence gene is not broadly distributed in Aba clinical isolates, and suggests that its presence is restricted to some clonal lineages.

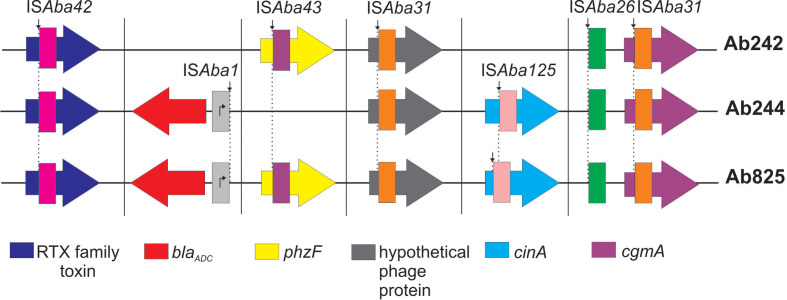

Insertion sites of IS elements in the chromosomes of the A. baumannii strains under study

The above observations prompted us to investigate other genetic variations over the Ab825 genome. IS elements are important drivers of genomic rearrangements in Aba clinical strains [19, 44]. Our analysis detected that some IS shared the same chromosomal insertion site between the three strains under study, as in the case of ISAba42 disrupting a gene encoding a type-I secretion-system-dependent protein, which probably functions as a RTX family toxin mediating biofilm development [86]; ISAba31 interrupting a gene for a putative phage protein, as well as the cgmA gene mentioned above (Fig. 4, Table S8). The insertional inactivation of any of the above three genes had not been reported previously in other Aba strains. These observations not only suggest that these three genes were already disrupted by the indicated ISs in a common ancestor of the three CC15P strains, but also reinforced their close clonal relationship detected by our genomic analysis. A study of 976 Aba genomes indeed found that phylogenetically closely related strains show analogous patterns of ISs inserted at equivalent sites in their genomes [19].

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the chromosomal location of ISs shared among Ab242, 244 and Ab825 strains. The IS positions are schematically depicted according to their location in the corresponding genomic sequence (Table S8). ISAba42 (magenta), ISAba43 (purple), ISAba31 (orange), ISAba125 (pink) and ISAba26 (green) interrupt different target genes whereas ISAba1 (light grey) falls in an intergenic region upstream of bla ADC gene (red arrow). Thus generating a strong promoter putatively enhancing the expression of this resistance gene. The IS insertion sites in a given target gene were depicted with a vertical black arrow and dashed lines. Genes are not drawn to scale.

Other IS integration events involved two out of the three strains under study. In this context, we mentioned above the ISAba1 copy located at the same position upstream of the bla ADC gene in Ab244 and Ab825 (Fig. 4, Table S8). Furthermore, a ISAba43 copy was found in Ab242 and Ab825 disrupting a gene encoding a PhzF-like protein [87] of unknown function (Fig. 4, Table S8). Moreover, a putative nicotinamide mononucleotide deamidase cinA gene implicated in competence [88], was interrupted by ISAba125 in both Ab244 and Ab825 (Fig. 4, Table S8). In this case, however, this IS was inserted at different locations within cinA, thus indicating independent acquisitions by each of these strains (Fig. 4). The IS-mediated inactivation of cinA has already been documented in at least 30 Aba genomes [19], although the physiological effects of these disruptions are unknown.

This bioinformatic analysis identified 16 IS-mediated gene disruptions in the Ab825 chromosome (Table S8). Some of the interrupted genes participate in biofilm formation and attachment to abiotic surfaces such as pgaB involved in the synthesis of poly-β-(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine PGA exopolysaccharide, csuA encoding a Csu pilus subunit, and a di-guanylate cyclase gene regulating biofilm production [2, 5, 89, 90]. In addition, an ISAba1 was found at the intergenic region between the CsuA/B component and a TetR-family transcriptional regulator (Table S8). Multiple IS integration events within the Aba csu cluster have been reported in clinical isolates [19], and the loss of the Csu pilus has been linked to niche specialization due to either increased invasiveness or enhanced survival [16]. It is therefore tempting to speculate that these IS-mediated disruption events may explain the only modest capacity of Ab825 strain to form biofilm and to adhere to both plastic surfaces and cultured epithelial lung cells [37].

Other genes encoding putative Aba virulence factors, such as a phospholipase D involved in host colonization [91] and the AsaA structural component of the T6SS [41, 92, 93] are also inactivated by ISAba125 elements in Ab825 (Table S8). Regarding the latter, we have previously demonstrated that Ab825 lacks a functional T6SS [37]. Of note, losses of T6SS main cluster genes have been previously reported in particular clonal lineages of phylogenetically and epidemiologically related Aba clinical MDR strains [26, 94, 95]. T6SS participates in interbacterial competition and may also have roles in host colonization, as judged by G. mellonella larvae model infection assays [37, 96]. However, the loss of this system in Ab825 and other MDR clinical strains suggests that it may not be critical for bacterial survival in the conditions prevailing in the nosocomial environment. Furthermore, silencing of the T6SS was recently shown to be critical for HGT through conjugation, which is crucial for AR spread [97]

Another gene disrupted by ISAba825 in strain Ab825 is carO, which codes for the second most abundant β-barrel protein after OmpA of the Aba outer membrane [10] (Table S8). CarO participates in the permeation of carbapenems across the OM [6, 7, 10], and has been proposed to also play roles in Aba pathogenicity [7, 8]. CarO enhances Aba cell adhesion and nasal colonization in mice mainly by inhibiting host inflammatory responses [98]. Other genes found disrupted by ISs in Ab825 are those encoding a ribonuclease D and a sensor histidine kinase (Table S8). The IS-mediated disruptions of these genes in other Aba strains have been previously described [19], but the physiological effects of these losses are hitherto unknown.

Not all IS insertions selected in the Ab825 chromosome are necessarily gene disruptive. In fact, some ISs confined to intergenic regions (Table S8) may have enhancing effects on the expression of adjacent genes. In this regard, it has been shown that ISAba1, ISAba125 and ISAba825 have strong outward-facing promoters, and that their insertions up-regulate the expression of proximal genes in Aba as in the cases of several β-lactamases [9, 17, 57, 61] and catalases [20]. In fact, this is most likely the situation resulting from the insertion of ISAba1 upstream of the chromosomal bla ADC-25 gene (Fig. 4, Table S8) thus conferring cephalosporin resistance to the host; and ISAba825 upstream of the plasmid-borne bla OXA-58 gene in Ab242 and Ab825 thus conferring carbapenem resistance. Whether other IS insertions at IRs in the Ab825 chromosome were selected due to abolishing or enhancing expression of adjacent genes, and the possible effects on the pathophysiology of Aba, remain to be established.

Discussion

MDR Aba nosocomial infections have become a public health concern, with a pan-drug resistance scenario emerging in the horizon as a worrying threat [2, 3, 5, 11]. Rapid acquisition of additional drug resistance is considered a main determinant of the success of Aba strains in the nosocomial environment [2, 3, 5]. The Aba virulence potential in turn seems intrinsic to the species, with the clinical outcomes depending on multiple host–bacterial interactions [3]. Different epidemic strains may in fact use distinct combinations of virulence determinants to optimize adaptation to the human host [2]. In this context, WGS comparisons represents a powerful tool to analyse these strategies.

Here, we conducted WGS comparative analysis of three clonally and epidemiologically related MDR strains belonging to the CC104O/CC15P, a CC linked to the dissemination of different CHDL genes in South America and some European and Asian countries [21, 99, 100]. Expectedly from their close relationships a general shared synteny was found between the chromosomes of all of these strains. Still, a more detailed analysis uncovered a number of acquired traits that contributed to genetic variability between strains, among them a heavy-metal ions RI only in Ab244, and a Ph-A prophage common to Ab242 and Ab825 but absent in Ab244. Furthermore, a search for AR genes revealed different repertoires carried in the chromosome or in plasmids. The most relevant are those conferring resistance to carbapenems and aminoglycosides genes, embedded in an adaptive module carried by plasmids present in Ab242 and Ab825 [57]. Their acquisition certainly contributed to the adaptation of the studied strains to the hospital environment when imipenem therapy was implemented [27]. It is worth noting the presence in all strains hereby analysed of an intact Tn6022 copy disrupting the comM gene. This represents the common insertion site for this element in many Aba genomes, and provides a hot spot for the integration of additional MGE carrying different resistance genes which turn this region into a bona fide RI [16, 45]. Intriguingly, Ab825 contains a second intact copy of Tn6022 disrupting a asnA gene in an unreported chromosomal location for this transposon. In contrast, resistance genes conferring the MDR phenotype are scattered in the genome of these strains, and in some cases the acquisition of a proper resistance phenotype depends more on IS elements than on HGT events as is the case of ISAba1 driving overexpression of bla ADC-25 in Ab244 and Ab825 resulting in increased cephalosporin resistance.

Another interesting observation is the lack of defense mechanisms against biological aggressors such as CDI, and T6SS CRISPR-cas systems in the strains under study. The loss of these systems by IS inactivation or recombination processes might be beneficial for strain survival in the hospital setting, since it enables dissemination of MGEs such as plasmids [97, 101]. In this context, examination of the strains under study indicated an extensive IS dissemination over the Ab825 genome as compared to Ab242 and Ab244. A total of 44 IS copies were identified in Ab825, which reinforces the idea of their importance in the remodelling of the genome of this particular strain. Inspection of the integration sites showed a conspicuous IS-mediated inactivation of genes involved in the synthesis of surface-exposed structures such as exopolysaccharides, pili, T6SS and OMP such as CarO. These findings are in line with proposals of the pivotal role of the Aba envelope in the infection process, since it contributes to protection from external aggressors including antimicrobials, other membrane disrupting substances, and effectors of the innate immune system [22]. In this context, gene inactivation may be important for Aba virulence in the form of immune evasion [2, 74], as has been previously determined for this and other bacteria [25]. This could explain infection assays indicating that strain Ab825 shows increased virulence. In addition, the different gene composition of the Ab825 K-locus responsible for capsule synthesis could also contribute to its higher relative virulence.

Overall, the genetic variations detected in strain Ab825 may have had a relevant impact on its pathogenic potential. These findings point to an impressive ability of Aba to quickly modify its genome in order to evade both natural host defenses and antibiotic intervention.

Data Bibliography

A. baumannii Ab242 Repizo,G.D., Cameranesi,M., Limanksy,A.S., Moran Barrio,J. and Viale,A.M. NCBI NXGW00000000 (2017)

A. baumannii Ab244 Repizo,G.D., Cameranesi,M., Limanksy,A.S., Moran Barrio,J. and Viale,A.M. NCBI PGTR00000000 (2017)

A. baumannii Ab825 Repizo,G.D., Cameranesi,M. and Borges,V. NCBI NTFR00000000 (2017)

A. baumannii Ab244 pAb244-7 Cameranesi,M. Accession number MG520098 (2018)

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was supported by grants to A.M.V. and J.M.B. from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnológica (ANPCyT, Argentina, PICT-2015–1072 and PICT-2017–3536, respectively); Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina); Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Productiva, Provincia de Santa Fe; Argentina; and a FINOVI Young Researcher Grant to S.P.S. M.M.C. is a Postdoctoral Fellow of CONICET, A.M.V., J.M.B. and G.D.R. are Career researchers of CONICET, and A.S.L. is a Researcher of the Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Joao Paulo Gomez and Dr Vitor Borges (NIH, Lisbon, Portugal) for their valuable help in A. baumannii Ab825 sequencing and assembly.

Author contributions

G.R., S.P.S., A.S.L and A.M.V. conceived and designed the work. M.M.C., J.P. and G.R. conducted the bioinformatics and experimental analysis. All authors analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Aba-, Acinetobacter baumannii; MGE-, mobile genetic elements; RI-, resistance islands.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files. Eight supplementary tables and four supplementary figures are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antunes LCS, Visca P, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog Dis. 2014;71:292–301. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong D, Nielsen TB, Bonomo RA, Pantapalangkoor P, Luna B, et al. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:409–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Brisse S. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roca I, Espinal P, Vila-Farrés X, Vila J. The Acinetobacter baumannii oxymoron: commensal hospital dweller turned pan-drug-resistant menace. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:148. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mussi M, Limansky A, Viale A. Acquisition of resistance to carbapenems in multidrug-resistant clinical strains of. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemother. 2005;49:1432–1440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1432-1440.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mussi MA, Relling VM, Limansky AS, Viale AM. CarO, an Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein involved in carbapenem resistance, is essential for L-ornithine uptake. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5573–5578. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mussi MA, Limansky AS, Relling V, Ravasi P, Arakaki A, et al. Horizontal gene transfer and assortative recombination within the Acinetobacter baumannii clinical population provide genetic diversity at the single carO gene, encoding a major outer membrane protein channel. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4736–4748. doi: 10.1128/JB.01533-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravasi P, Limansky AS, Rodriguez RE, Viale AM, Mussi MA. ISAba825, a functional insertion sequence modulating genomic plasticity and bla(OXA-58) expression in Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:917–920. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00491-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morán-Barrio J, Cameranesi MM, Relling V, Limansky AS, Brambilla L, et al. The Acinetobacter outer membrane contains multiple specific channels for carbapenem β-lactams as revealed by kinetic characterization analyses of imipenem permeation into Acinetobacter baylyi cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01737-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the who priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:318. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Touchon M, Cury J, Yoon E-J, Krizova L, Cerqueira GC, et al. The genomic diversification of the whole Acinetobacter genus: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:2866–2882. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding CM, Hennon SW, Feldman MF. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:91–102. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C-R, Lee JH, Park M, Park KS, Bae IK, et al. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms, and Prospective Treatment Options. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:55. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigro SJ, Post V, Hall RM. The multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii European clone I type strain RUH875 (A297) carries a genomic antibiotic resistance island AbaR21, plasmid pRAY and a cluster containing ISAba1-sul2-CR2-strB-strA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1928–1930. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AP, Sutton G, DePew J, Krishnakumar R, Choi Y, et al. A novel method of consensus pan-chromosome assembly and large-scale comparative analysis reveal the highly flexible pan-genome of Acinetobacter baumannii . Genome Biol. 2015;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nigro SJ, Hall RM. Structure and context of Acinetobacter transposons carrying the oxa23 carbapenemase gene. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1135–1147. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackwell GA, Hall RM. The tet39 Determinant and the msrE-mphE Genes in Acinetobacter Plasmids Are Each Part of Discrete Modules Flanked by Inversely Oriented pdif (XerC-XerD) Sites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00780-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams MD, Bishop B, Wright MS. Quantitative assessment of insertion sequence impact on bacterial genome architecture. Microb Genom. 2016;2:e000062. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright MS, Mountain S, Beeri K, Adams MD. Assessment of insertion sequence mobilization as an adaptive response to oxidative stress in Acinetobacter baumannii using IS-seq. J Bacteriol. 2017;199 doi: 10.1128/JB.00833-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karah N, Sundsfjord A, Towner K, Samuelsen Ørjan. Insights into the global molecular epidemiology of carbapenem non-susceptible clones of Acinetobacter baumannii . Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisinger E, Huo W, Hernandez-Bird J, Isberg RR. Acinetobacter baumannii: Envelope Determinants That Control Drug Resistance, Virulence, and Surface VariEnvelope Determinants That Control Drug Resistance, Virulence, and Surface Variability. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2019;73:481–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repizo GD, Viale AM, Borges V, Cameranesi MM, Taib N, et al. The environmental Acinetobacter baumannii isolate DSM30011 reveals clues into the preantibiotic era genome diversity, virulence potential, and niche range of a predominant nosocomial pathogen. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:2292. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yakkala H, Samantarrai D, Gribskov M, Siddavattam D. Comparative genome analysis reveals niche-specific genome expansion in Acinetobacter baumannii strains. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Montero CI, Stock F, Mijares L, et al. Genome-Wide recombination drives diversification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13758–13763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright MS, Haft DH, Harkins DM, Perez F, Hujer KM, et al. New insights into dissemination and variation of the health care-associated pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii from genomic analysis. mBio. 2014;5:e00963-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00963-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limansky AS, Zamboni MI, Guardati MC, Rossignol G, Campos E, et al. Evaluation of phenotypic and genotypic markers for clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii . Medicina. 2004;64:306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mussi MA, Limansky AS, Viale AM. Acquisition of resistance to carbapenems in multidrug-resistant clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii: natural insertional inactivation of a gene encoding a member of a novel family of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1432–1440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1432-1440.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Document M100S. 26th ed. Wayne, PA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. ProgressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao F, Zhang C-T. Ori-Finder: a web-based system for finding oriCs in unannotated bacterial genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, Sajed T, Pon A, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jolley KA, Maiden MCJ. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antunes LCS, Imperi F, Towner KJ, Visca P. Genome-Assisted identification of putative iron-utilization genes in Acinetobacter baumannii and their distribution among a genotypically diverse collection of clinical isolates. Res Microbiol. 2011;162:279. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Repizo GD, Gagné S, Foucault-Grunenwald M-L, Borges V, Charpentier X, et al. Differential role of the T6SS in Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clímaco EC, Oliveira MLde, Pitondo-Silva A, Oliveira MG, Medeiros M, et al. Clonal complexes 104, 109 and 113 playing a major role in the dissemination of OXA-carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Southeast Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;19:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stietz MS, Ramírez MS, Vilacoba E, Merkier AK, Limansky AS, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii extensively drug resistant lineages in Buenos Aires hospitals differ from the International clones I-III. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:601–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1510307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Repizo GD, Espariz M, Seravalle JL, Salcedo SP. Bioinformatic analysis of the type VI secretion system and its potential toxins in the Acinetobacter genus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Gregorio E, Zarrilli R, Di Nocera PP. Contact-dependent growth inhibition systems in Acinetobacter . Sci Rep. 2019;9:154. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36427-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roussin M, Rabarioelina S, Cluzeau L, Cayron J, Lesterlin C, et al. Identification of a Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition (CDI) System That Reduces Biofilm Formation and Host Cell Adhesion of Acinetobacter baumannii DSM30011 Strain. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2450. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright MS, Haft DH, Harkins DM, Perez F, Hujer KM, et al. New insights into dissemination and variation of the health care-associated pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii from genomic analysis. mBio. 2014;5:e00963-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00963-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Jung S-I, Kwon KT, Ko KS. Occurrence of diverse AbGRI1-type genomic islands in Acinetobacter baumannii global clone 2 isolates from South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01972-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seputiene V, Povilonis J, Sužiedeliene E. Novel variants of AbaR resistance islands with a common backbone in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates of European clone II. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1969–1973. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05678-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Post V, White PA, Hall RM. Evolution of AbaR-type genomic resistance islands in multiply antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1162–1170. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu F, Zhu Y, Yi Y, Lu N, Zhu B, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates reveals extensive genomic variation and diverse antibiotic resistance determinants. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Jabri Z, Zamudio R, Horvath-Papp E, Ralph JD, Al-Muharrami Z, et al. Integrase-Controlled Excision of Metal-Resistance Genomic Islands in Acinetobacter baumannii . Genes. 2018;9:366. doi: 10.3390/genes9070366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrugia DN, Elbourne LDH, Mabbutt BC, Paulsen IT. A novel family of integrases associated with prophages and genomic islands integrated within the tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase A (dusA) gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:4547–4557. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghisotti D, Finkel S, Halling C, Dehò G, Sironi G, et al. Nonessential region of bacteriophage P4: DNA sequence, transcription, gene products, and functions. J Virol. 1990;64:24–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.64.1.24-36.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Costa AR, Monteiro R, Azeredo J. Genomic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii prophages reveals remarkable diversity and suggests profound impact on bacterial virulence and fitness. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15346. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33800-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Babu MM, Iyer LM, Balaji S, Aravind L. The natural history of the WRKY-GCM1 zinc fingers and the relationship between transcription factors and transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6505. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eaves-Pyles T, Allen CA, Taormina J, Swidsinski A, Tutt CB, et al. Escherichia coli isolated from a Crohn's disease patient adheres, invades, and induces inflammatory responses in polarized intestinal epithelial cells. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chai B, Wang H, Chen X. Draft genome sequence of high-melanin-yielding Aeromonas media strain Ws. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:6693. doi: 10.1128/JB.01807-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cameranesi MM, Morán-Barrio J, Limansky AS, Repizo GD, Viale AM. Site-Specific Recombination at XerC/D Sites Mediates the Formation and Resolution of Plasmid Co-integrates Carrying a bla OXA-58- and TnaphA6-Resistance Module in Acinetobacter baumannii . Front Microbiol. 2018;9:66. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mindlin S, Beletsky A, Mardanov A, Petrova M. Adaptive dif modules in permafrost strains of Acinetobacter lwoffii and their distribution and abundance among present day Acinetobacter strains. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brovedan M, Repizo GD, Marchiaro P, Viale AM, Limansky A. Characterization of the diverse plasmid pool harbored by the blaNDM-1-containing Acinetobacter bereziniae HPC229 clinical strain. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evans BA, Amyes SGB. Oxa β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:241–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lopes BS, Amyes SGB. Role of ISAba1 and ISAba125 in governing the expression of blaADC in clinically relevant Acinetobacter baumannii strains resistant to cephalosporins. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1103. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.044156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Segal H, Jacobson RK, Garny S, Bamford CM, Elisha BG. Extended -10 promoter in ISAba-1 upstream of blaOXA-23 from Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3040–3041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00594-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tian G-B, Adams-Haduch JM, Taracila M, Bonomo RA, Wang H-N, et al. Extended-Spectrum AmpC cephalosporinase in Acinetobacter baumannii: ADC-56 confers resistance to cefepime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4922–4925. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00704-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]