Abstract

Background

Complement pathway inhibition may provide benefit for severe acute respiratory illnesses caused by viral infections such as COVID-19. We present results from a nonrandomized proof-of-concept study of complement C5 inhibitor eculizumab for treatment of severe COVID-19.

Methods

All patients (N = 80) with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 admitted to our intensive care unit between March 10 and May 5, 2020 were included. Forty-five patients were treated with standard care and 35 with standard care plus eculizumab through expanded-access emergency treatment. The prespecified primary outcome was day-15 survival. Clinical laboratory values and biomarkers, complement levels, and treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs) were also assessed.

Findings

At day 15, estimated survival was 82.9% (95% CI: 70.4%‒95.3%) with eculizumab and 62.2% (48.1%‒76.4%) without eculizumab (log-rank test, P = 0.04). Patients treated with eculizumab experienced a significantly more rapid decrease in lactate, blood urea nitrogen, total and conjugated bilirubin levels and a significantly more rapid increase in platelet count, prothrombin time, and in the ratio of arterial oxygen tension over fraction of inspired oxygen versus patients treated without eculizumab. Eculizumab-associated changes in complement levels, laboratory values, and biomarkers were consistent with terminal complement inhibition, reduced hypoxia, and decreased inflammation. TESAEs of special interest occurring in >5% of patients treated with/without eculizumab were ventilator-associated pneumonia (51%/24%), bacteremia (11%/2%), gastroduodenal hemorrhage (14%/16%), and hemolysis (3%/18%).

Interpretation

Findings from this proof-of-concept study suggest eculizumab may improve survival and reduce hypoxia in patients with severe COVID-19. Randomized studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of this treatment approach are needed.

Funding

Programme d'Investissements d'Avenir: ANR-18-RHUS60004.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pneumonia, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis, Complement pathway, C5 inhibitor, Cytokines

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

As of June 9, 2020, 4 publications (including 2 non‒peer reviewed preprints) reported evidence for over-activation of the complement system and complement-mediated thrombotic microvascular injury in patients with COVID-19. In addition, in 1 case report (press release) and 2 case series (each, n = 4), patients with COVID-19 showed clinical improvement after treatment with the complement C5 inhibitor eculizumab and/or ravulizumab.

Added value of this study

We report results from a series of 80 patients with severe COVID-19 who were treated with standard care (n = 45) or standard care plus intravenous eculizumab (n = 35). Patients treated with eculizumab had improved survival. Eculizumab-associated changes in complement levels, laboratory values, and biomarkers were consistent with terminal complement inhibition, reduced hypoxia, and decreased inflammation.

Implications of all the available evidence

This report substantiates, in a larger cohort, findings from reports showing clinical improvement with use of eculizumab as emergency treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 and may inform randomized studies of C5 inhibitors for COVID-19.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has spread from Wuhan, China, and as of June 9, 2020, has infected more than 7,000,000 people in 188 countries, causing >400,000 deaths [1,2]. The crude hospitalization rate for patients with COVID-19, the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2, is approximately 82 per 100,000 persons in the United States and 153 per 100,000 persons in France [3,4]. According to published reports, 5‒32% of confirmed, hospitalized patients require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [2,5]. In these severe COVID-19 cases, clinical manifestations may include pneumonia; acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) necessitating respiratory support; acute kidney, cardiac, and liver injury; sepsis; and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy [2,5].

Cytokine storm is thought to be a key step in the pathogenesis of ARDS following SARS-CoV-2 infection [6]. There are numerous cytokine-related molecules and pathways relevant to understanding the biological mechanisms underlying acute lung injury after viral infection. Among these, research has elucidated a critical role for the complement system, an important component of innate and adaptive immunity [7]. Complement signaling orchestrates key immunoprotective and anti-inflammatory functions, enabling clearance of pathogens and apoptotic cells [7]. However, complement activation and subsequent production of the proinflammatory anaphylatoxin C5a, a cleavage product of terminal complement protein C5, and formation of the terminal complement complex C5b-9, precipitate biological sequelae that can be harmful if unchecked, including activation of endothelial and phagocytic cells, generation of reactive oxygen species, and initiation of an inflammatory cytokine storm [8]. C5a-mediated effects have been shown to play a critical role in the development of acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic viruses [8]. In mice, complement inhibition directed at C5a or upstream proteins (ie, C3, C3a) reduced lung injury after SARS-CoV [9] and influenza H5N110 virus infection. In SARS-CoV−infected mice, this occurred without change in viral titer [9], suggesting that complement inhibition may provide protection from lung injury independent of viral load. Similar protection after C5a inhibition has been observed in animal models of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus [11], avian influenza H5N1 virus [10], and H7N9 virus infection [12]. Clinical studies have provided evidence for excessive complement activation in patients with SARS [13] and H1N1 influenza [14,15], correlating to some degree with disease severity [13,15]. Other work has shown that progression of SARS illness is accompanied by the development of autoantibodies that mediate a form of complement-dependent cytotoxicity that may lead to further lung injury [16]. More recently, clinical studies have shown evidence for over-activation of the complement pathway in patients with COVID-19 [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Collectively, these observations suggest that blocking complement activation using a C5 inhibitor may be an effective treatment option for SARS-CoV−mediated disease.

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that is approved for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG), and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. Eculizumab binds to terminal complement C5 with high affinity, inhibiting its cleavage to C5a and C5b and preventing the formation of C5b-9, which has variable effects, including lytic, proinflammatory, and prothrombotic properties [7,28,29]. Selective C5 blockade preserves upstream complement component activity essential for opsonization of microorganisms and prevention of immune complex disorders [28,30]. The ability of eculizumab to prevent tissue injury and the proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects of C5a and C5b-9 while preserving upstream immunoprotective and immunoregulatory functions suggests it may be an effective therapeutic for severe respiratory illness, including severe COVID-19. A recent case report and 3 small case series further suggest that this could be a promising therapeutic approach [[31], [32], [33], [34]]. Here, we present results from our proof-of-concept study of eculizumab as an experimental emergency treatment for patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the ICU.

2. Methods

The study protocol is available in the supplementary material. Study registration number is NCT04355494 [35].

2.1. Patients and treatment

This nonrandomized controlled study included a consecutive cohort of patients ≥18 years of age admitted to the 36-bed COVID-19 ICU at Hôpital Raymond Poincaré, which was designated by the Minster of Health as the referral center for patients with COVID-19 living in the Hauts-de-Seine county (Southwest part of the greater Paris area: 176 km² and 1.6 million inhabitants). This hospital, which is part of the Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris network, had previously been identified by the European Network for Highly Infectious Diseases as having the capability of managing and treating highly infectious diseases and had been designated as a referral center by French Health Authorities during the Ebola Virus Disease and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus epidemics.

Study enrollment started on March 10, 2020, which was the date at which the ICU was converted into a COVID-19 only ICU. Enrollment was terminated on May 5, 2020, the date at which the ICU started recruiting patients for a different trial.

Inclusion criteria were severe COVID-19 confirmed by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Severe disease was defined as disease requiring ICU hospitalization. Additional inclusion criteria were symptomatic bilateral pulmonary infiltrates confirmed by computed tomography or chest X-ray ≤7 days before screening; and severe pneumonia, acute lung injury, or ARDS requiring supplemental oxygen. Patients were excluded if they weighed <40 kg; required <6 L/min of oxygen to maintain arterial oxygen saturation >90%; or had a life expectancy ≤24 h, unresolved Neisseria meningitidis infection, or hypersensitivity to murine proteins or to an excipient of eculizumab.

Patients were treated according to guidelines from the institution and the French Ministry of Health for severe COVID-19 [36,37], which included respiratory management, anticoagulants, antivirals, and antibiotics when indicated. On March 19, 2020, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., (Boston, MA, USA), subsequent to physician request and in accordance with relevant national regulatory authorities, provided access to eculizumab (300 mg/30 mL vials for intravenous infusion) as an experimental emergency treatment for adults with COVID-19 and severe pneumonia, acute lung injury, or ARDS. Placement in the eculizumab treatment group was based on the availability of eculizumab at the time of ICU admission. Patients, who were admitted to the ICU when eculizumab was available, were assigned to the eculizumab treatment group. Patients who were admitted when eculizumab was not available, were assigned to the control group. Specifically, patients received the first dose of eculizumab on March 21‒24, April 7, April 10‒17, and April 21‒May 6 of 2020.

Upon initial delivery of eculizumab, 10 consecutive patients received emergency treatment according to dosing procedures within a subsequently approved expanded-access program (EAP) protocol [35]. Twenty-five patients were then formally enrolled into the approved EAP protocol.

Single infusions of eculizumab 900 mg were administered intravenously over 45 min on days 1 (within 7 days of confirmed pneumonia or ARDS), 8, 15, and 22. Preliminary serum free eculizumab concentrations, CH50 and serum C5b-9 levels (data not shown and preliminary data from a case series) [34] suggested that more frequent and increased dosing of eculizumab was needed to achieve complete and sustained complement inhibition. A protocol amendment was implemented on April 17, 2020, which allowed higher and more frequent doses to be administered (1200 mg on days 1, 4, and 8 and 900 mg on days 15 and 22. Optional doses of 900 or 1200 mg could be administered on days 12 and 18 per investigator decision in consultation with the Medical Monitor). This regimen was designed to achieve immediate, complete, and sustained terminal complement inhibition.

Before initiating and during treatment with eculizumab, patients received vaccination and prophylactic antibiotics against meningococcal infection (ie, cefotaxime). These patients were scheduled to continue antibiotics for ≥60 days after the last infusion. Patients released from the ICU were required to remain hospitalized under quarantine until they were symptom-free for ≥2 days.

2.2. Study assessments and outcomes

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics and concomitant medication use were recorded in the hospital electronic health records at ICU admission. Physical examination, vital signs, and laboratory tests were recorded at ICU admission and during treatment. Antiviral treatment, respiratory support, vasopressor therapy, and renal replacement therapy were also recorded. Serum samples for analysis of biomarkers of complement activation were collected before each infusion (Supplementary Methods).

The primary outcome was survival (based on all-cause mortality) at day 15, representative of previously reported approximate median time to death [38]; this was the primary efficacy endpoint prespecified in the EAP protocol. Additional outcomes of interest were survival at day 28, number of days alive and free of mechanical ventilation at days 15 and 28 in patients ventilated at baseline, number of ICU-free days at days 15 and 28, and change in oxygenation status at day 15. Other outcomes included changes over time in respiratory function, markers of tissue hypoxia, hematology and clinical chemistry parameters, inflammatory mediators, serum eculizumab levels, and soluble biomarkers associated with complement activation. Safety was characterized based on the incidence of treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs) of special interest (infectious complications, hematologic disorders, and events associated with critical care); TESAEs were assessed daily from first administration through day 28 or discharge, whichever came first.

2.3. Oversight

The EAP protocol was approved by the local regulatory board (Agence National de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Council for harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local laws and regulations. Owing to the “state of health emergency” in France and French law regulating nationwide lockdown and prohibiting visits with patients, it was not possible to obtain prior written informed consent from patients or legal representatives. Therefore, assent from the closest relative was obtained via teleconference, and deferred written informed consent was recorded in all cases where prior informed consent could not be obtained, in accordance with guidance from the European Medicines Agency on the management of clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic [39]. The sponsor designed the EAP and provided eculizumab. Clinical and laboratory variables were independently extracted from hospital electronic health records. Assessments were recorded by research staff and analyzed independently by l'Unité de Recherche Clinique de l'Assistance Publique‒Hôpitaux de Paris (APHP) Paris-Saclay (Direction de la Recherche Clinique et de l'Innovation de l'APHP). All authors had full and independent access to all data and vouch for the integrity, accuracy, and completeness of the data and analysis and to adherence to the EAP protocol.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Because this was a proof-of-concept study, there was no formal sample size calculation; analyses included all patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the ICU between March 10 and May 5, 2020. The index date (baseline; day 0) was the date of ICU admission. Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and laboratory values were compared using Fisher's exact test (categorical variables) or the Wilcoxon tests (continuous variables); and missing values were not imputed. Survival rates were estimated from the data using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the resulting Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using a log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a Cox proportional-hazards model adjusted for sex and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) [40], with exposure as a time-dependent variable. Actual proportions for survival and rates of TESAEs were compared using Fisher's exact test. Changes in laboratory values over time were assessed using linear mixed models for longitudinal data with a time by group effect. Changes in C5b-9 levels and days alive and free of mechanical ventilation were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. P-values were two-sided. Analyses were performed with R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

2.5. Role of the funding source

Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provided eculizumab for emergency treatment as part of their EAP, designed the EAP protocol, funded medical writing and editorial support for development of this manuscript, and reviewed the manuscript only for technical and medical accuracy and veracity related to statements about eculizumab. Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., had no role in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and had no role in the decision to submit the data for publication. Statistical analyses were conducted independently by the authors. All authors had full access to the study data. The corresponding author (D.A.), in collaboration with the medical writers, prepared the initial manuscript draft. All authors participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, provided critical review of the manuscript, had full editorial control of the manuscript, and were responsible for final approval to submit for publication.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Between March 10 and May 5, 2020, 80 consecutive patients were admitted to the COVID-19 ICU and met inclusion criteria. No patients met exclusion criteria during screening. Thirty-five patients received treatment with eculizumab and 45 patients did not. Survival data were collected for all patients until day 28. Median (IQR) time from ICU admission to first dose of eculizumab was 3 (2‒5) days.

Of the 10 patients who were scheduled to receive 900 mg of eculizumab on days 1, 8, 15, and 22, 8 received all 4 doses, and 2 patients died before receiving all 4 doses. Of the 15 patients who converted to the amended dosing schedule after they had started taking eculizumab (on or after day 8), 10 received all 5 doses and 2 patients died before receiving all 5 doses. Of the 10 patients who were scheduled to receive the amended dosing schedule, 6 received all 6 doses, and 2 patients died before receiving all 6 doses. Five patients did not receive their full dosing schedule because they either refused the medication or had been discharged from the hospital.

Patient baseline characteristics, including diagnosis of severe pneumonia and ARDS and markers of complement activation and infection, did not differ significantly between groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Median age of patients treated with versus without eculizumab was 64 and 55 years, respectively (P = 0.30); 63% versus 76% were men (P = 0.31); and 37% versus 60% had severe ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 ≤100 mmHg), respectively (P = 0.07). Medians (IQR) scores on the SAPS II were 66 (48–71) and 56 (46–67), respectively (P = 0.08). Median time from first symptoms to hospitalization was 6 days (both groups). No statistically significant differences were found in standard medication use between groups. The proportion of patients who received remdesivir was 3% and 16%, respectively (P = 0.07), and 11% and 27%, respectively (P = 0.16), received lopinavir-ritonavir.

Table 1.

Patient baselinea demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic | With Eculizumab (n = 35) |

Without Eculizumab (n = 45) |

P-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 64 (54–71) | 55 (43–73) | 0.30 |

| Men, n (%) | 22 (63) | 34 (76) | 0.31 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 26.2 (22.2–31.1)c | 26.1 (23.5–28.5) | 0.84 |

| Time from symptoms onset to hospitalizationd, days, median (IQR) | 6 (3–8)c | 6 (5–9) | 0.19 |

| Time from hospitalization to ICU admission, days, median (IQR) | 2 (0–5)c | 1 (0–3) | 0.18 |

| SAPS IIe, median (IQR) | 66 (48–71) | 56 (46–67)f | 0.08 |

| SOFA scoreg, median (IQR) | 9 (8–12) | 8 (3–12)f | 0.22 |

| PaO2/FiO2, mmHgh | |||

| Median (IQR) | 102 (76–150) | 93 (74–130) | 0.90 |

| Severe ≤100, n (%) | 13 (37) | 27 (60) | 0.07 |

| Mild/moderate >100, n (%) | 22 (63) | 18 (40) | |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 21 (60) | 31 (69) | 0.48 |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 6 (17) | 15 (33) | 0.13 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 14 (40) | 16 (36) | 0.82 |

| Coronary heart disease | 6 (17) | 9 (20) | 0.78 |

| Cancer | 6 (17) | 7 (16) | 1 |

| Kidney failure | 1 (3) | 4 (9) | 0.38 |

| COPD | 0 | 3 (7) | 0.25 |

| Medication use, n (%) | |||

| Heparin, 4000 IU/day | 35 (100) | 44 (98) | 1 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 30 (86) | 41 (91) | 0.49 |

| Vasopressors | 6 (17) | 9 (20) | 0.78 |

| Lopinavir-ritonavir | 4 (11) | 12 (27) | 0.16 |

| Corticosteroids | 5 (14) | 4 (9) | 0.49 |

| ACE inhibitor | 2 (6) | 6 (13) | 0.46 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 2 (6) | 3 (7) | 1 |

| Remdesivir | 1 (3) | 7 (16) | 0.07 |

ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; BMI=body mass index; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU=intensive care unit; IQR=interquartile range; PaO2/FiO2=ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fractional inspired oxygen; SAPS II=Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Baseline was defined as the index date (date of ICU admission).

Calculated using Fisher's exact test or Wilcoxon test.

n=34.

One patient in each group was hospitalized before symptom onset; these patients contracted SARS-CoV-2 during a hospital stay and were subsequently transferred to the ICU.

SAPS II ranges from 0 (lowest risk of in-hospital mortality) to 163 (highest risk of in-hospital mortality).

n=44.

SOFA scores consist of 6 organ systems, which are graded from 0 (no organ dysfunction) to 4 (high organ dysfunction); total scores range from 0 (no organ dysfunction; low risk of mortality) to 24 (high organ dysfunction; high risk of mortality).

With eculizumab, n = 28; without eculizumab, n = 42.

3.2. Survival analyses

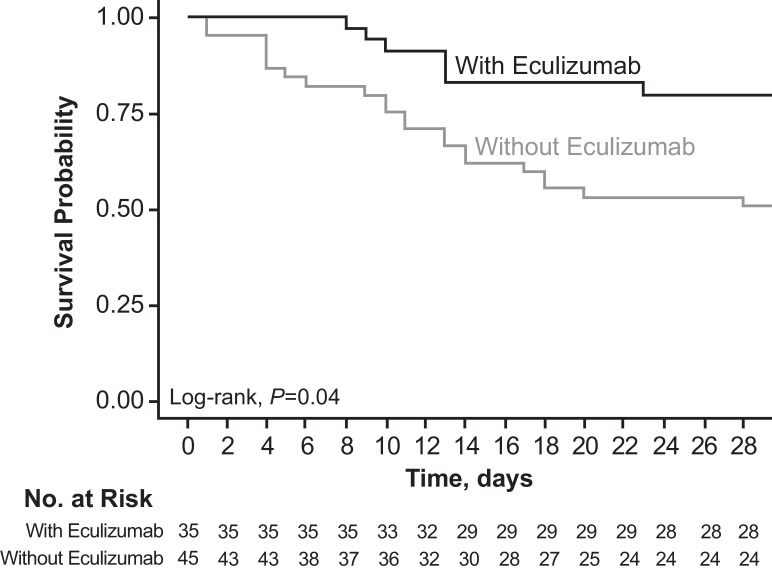

The estimated proportion of patients alive at day 15 was 82.9% (95% CI, 70.4%‒95.3%) for patients treated with eculizumab and 62.2% (95% CI, 48.1%‒76.4%) for patients treated without eculizumab; the estimated proportion of patients who were alive at day 28 was 80.0% (95% CI, 66.8%‒93.3%) and 51.1% (95% CI, 36.5%‒65.7%), respectively. In the prespecified statistical analysis, the log-rank test showed a significant difference in survival curves between groups (P = 0.04; Fig. 1). In the 2 secondary analyses of the primary outcome, crude and sex- and SAPS II‒adjusted HR (95% CI) for mortality at day 15 were 0.35 (0.14–0.90; P = 0.03) and 0.14 (0.02‒1.18; P = 0.07), respectively, and actual proportions for mortality at day 15 were 6/35 (17.1%) with eculizumab and 17/45 (37.8%) without eculizumab (P = 0.05). At day 28, crude and sex- and SAPS II‒adjusted HRs (95% CI) for mortality were 0.30 (0.13‒0.75; P = 0.007) and 0.23 (0.048‒1.11; P = 0.07), respectively. Actual proportions for mortality at day 28 were 7/35 (20.0%) with eculizumab and 23/45 (51.1%) without eculizumab (P = 0.005), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimated probability of survival.

Survival rates in patients treated with versus without eculizumab were estimated from the all-cause mortality data using the Kaplan–Meier method. The resulting Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using a log-rank test. Differences between survival curves were significant (P = 0.04).

In patients who were ventilated at baseline, median (IQR) number of days alive and free of mechanical ventilation at day 15 was 0 (0‒0) with and without eculizumab (P = 0.1). The median (IQR) number of ICU-free days at day 28 was 0 (0‒12) with eculizumab and 0 (0‒18) without eculizumab.

3.3. Oxygenation and biomarkers

At day 15, the proportion of patients treated with and without eculizumab who showed improvement in oxygenation, as measured by a shift in PaO2/FiO2 from ≤100 to >100 mmHg, was 66% and 25% (P = 0.0003), respectively (Table 2). Over time, patients treated with eculizumab experienced more rapid clearance of lactate (P = 0.003); more rapid increase in platelet count (P<0.001) and PaO2/FiO2 (P = 0.006); and more rapid improvement in prothrombin time (P = 0.004), blood urea nitrogen levels (P<0.001), total bilirubin levels (P<0.001), and conjugated bilirubin levels (P<0.001); other hematologic, chemistry, and respiratory parameters did not differ significantly between groups (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). The proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 (P = 0.04), IL-17 (P = 0.01), and IFN-α2 (P = 0.03) decreased more rapidly over time in patients receiving eculizumab (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2); there were no significant differences between groups in the evolution of other proinflammatory mediators or the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-4, IL-10, and IL-1RA (Table 3).

Table 2.

Improvement in oxygenation from baseline to day 15.

| PaO2/FiO2, mmHg | With Eculizumab (N = 35) |

Without Eculizumab (N = 45) |

P-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 35) |

Day 15 (n = 28b) |

Baseline (n = 45) |

Day 15 (n = 25c) |

||

| ≤100, n (%) | 13 (37) | 5 (17) | 27 (60) | 10 (40) | 0.08 |

| >100, n (%) | 22 (63) | 24 (83) | 18 (40) | 15 (60) | |

| Shift from ≤100 to >100, n/N (%) | – | 19/29 (66) | – | 4/25 (25) | 0.0003 |

N=number of patients with available data; PaO2/FiO2=ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fractional inspired oxygen.

Fisher's exact test was used to compare the categories of PaO2/FiO2 at day 15 between the two groups.

Data missing for 7 patients: 6 patients died and 1 patient left the hospital alive by day 15.

Data missing for 20 patients: 17 patients died and 3 patients left the hospital alive by day 15.

Table 3.

Estimateda differences in change in hematologic, chemistry, and respiratory parameters and inflammatory markers from day 1 to day 15.

| Parameter | With Eculizumab | Without Eculizumab | β Difference | P-Valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | βb | n | βb | |||

| Platelets, 109/L | 35 | 10.4 | 45 | 4.8 | −5.6 | <0.001 |

| Prothrombin time,% ratio patient/control | 35 | −0.4 | 45 | −0.9 | −0.5 | 0.004 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 35 | −0.1 | 45 | −0.1 | 0.01 | 0.7 |

| D-dimers, ng/mL | 35 | −88.4 | 41 | 320.8 | 409.2 | 0.1 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 35 | 2.5 | 45 | 2.6 | 0.05 | 0.9 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 35 | 0.09 | 45 | 0.4 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytes, 109/L | 35 | 0.06 | 44 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.8 |

| Procalcitonin, μg/L | 35 | −0.009 | 44 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| CRP, mg/L | 35 | −3.3 | 45 | −3.5 | −0.2 | 0.9 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 35 | 0.4 | 45 | 1.9 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Conjugated bilirubin, μmol/L | 35 | 0.3 | 44 | 1.5 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Troponin T, ng/L | 35 | −1.9 | 45 | −1.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| PaO2/FiO2, mmHg | 35 | 2.8 | 45 | 0.1 | −2.7 | 0.006 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 35 | −0.03 | 19 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.003 |

| TNF-α | 29 | –3.1 | 19 | –1.2 | 1.9 | 0.06 |

| IL-1β | 28 | –0.38 | 17 | –0.18 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| IL-6 | 29 | –53.6 | 19 | –9.8 | 43.8 | 0.04 |

| IL-8 | 29 | –6.3 | 19 | 2.5 | 8.8 | 0.20 |

| IL-1RA | 29 | –87.1 | 19 | –21.7 | 65.4 | 0.60 |

| IL-4 | 29 | –0.05 | 19 | –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.30 |

| IL-10 | 29 | 7.4 | 19 | –0.1 | –7.5 | 0.60 |

| IL-17 | 29 | –0.3 | 19 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| IFN-α2 | 29 | –0.2 | 19 | –0.07 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| IFN-γ | 29 | –1.4 | 19 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.08 |

CRP=C-reactive protein; IFN=interferon; IL=interleukin; IL-1RA=IL-1 receptor antagonist; PaO2/FiO2=ratio of partial pressure of oxygen to fractional inspired oxygen; TNF=tumor necrosis factor. Laboratory data were collected up to day 15 (time point for primary outcome) or up to death or ICU discharge.

Changes in laboratory values over time were assessed using linear mixed models for longitudinal data with a time by group effect.

Slope of change in parameter over time.

Calculated with linear mixed model for longitudinal data with time-by-group effect.

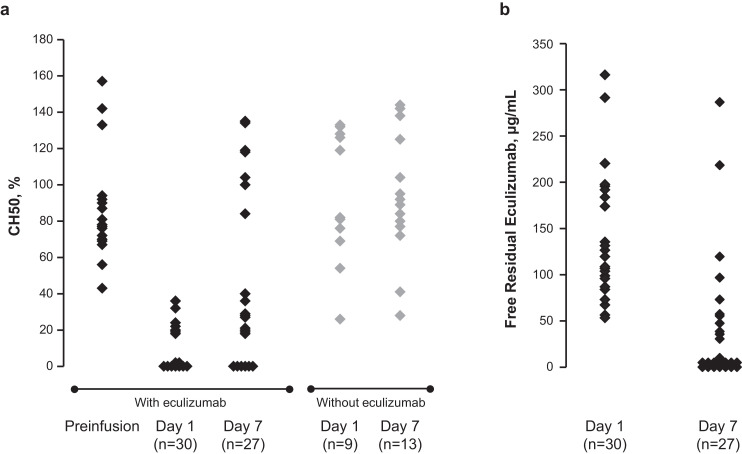

3.4. Complement activation

In patients receiving eculizumab, free residual eculizumab levels were variable (54‒320 µg/mL) on day 1 and undetectable in 15 of 27 patients on day 7 (Fig. 2). Among the patients with detectable eculizumab levels (>25 μg/mL), 8 of them had received 1200 mg of eculizumab on day 4 and had eculizumab levels ≥36 μg/mL. CH50 activity was decreased on day 1 compared with preinfusion activity, with detectable levels in 11 of 16 patients on day 7 (Fig. 2). Serum soluble C5b-9 levels decreased over time (Supplementary Table 3), whereas C3 and C4 levels remained stable (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Change from baseline to day 1 and day 7 in (a) CH50 activity in patients treated with and without eculizumab and (b) free residual eculizumab in patients treated with eculizumab.

The 50% hemolytic complement (CH50) assay is a validated method used to measure hemolytic complement activity. The CH50 assay can be used to measure changes in levels of C5 activity. Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds C5 and blocks complement activation at C5. Each diamond represents 1 patient sample.

3.5. Safety

Treatment-emergent SAEs of special interest through day 28 are shown in Table 4. The proportion of patients experiencing a TESAE of an infectious complication was significantly greater with versus without eculizumab (57% vs 27%, respectively; P = 0.01). Case details are described in Supplementary Table 4. Ventilator-associated pneumonia was reported in 51% versus 24% of patients treated with versus without eculizumab, respectively; bacteremia in 11% versus 2%; gastroduodenal hemorrhage in 14% versus 16%; and hemolysis in 3% versus 18%. Ventilator-associated pneumonia was treated with appropriate antibiotics (betalactam or cephalosporin, macrolides, aminosides, carbapenem). The patient who experienced pulmonary embolism was alive at the time of discharge.

Table 4.

Summary of TESAEs of special interest through day 28.

| Patients With Event, n (%) | With Eculizumab (n = 35) |

Without Eculizumab (n = 45) |

P-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious complications | 20 (57) | 12 (27) | 0.01 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 18 (51) | 11 (24) | 0.02 |

| Bacteremia | 4 (11) | 1 (2) | 0.2 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 |

| Gastroduodenal hemorrhage | 5 (14) | 7 (16) | 1 |

| Hemolysis | 1 (3) | 8 (18) | 0.07 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 |

| Catheter-related infection | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 |

| Cutaneous rash | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 0 | – |

TESAE=treatment-emergent serious adverse event.

Adverse event terms are based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 22.1.

Calculated using Fisher's exact test.

4. Discussion

The analyses reported here represent the largest and one of the first experiences using the complement C5 inhibitor eculizumab as emergency treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 [31,32]. Compared with patients not receiving eculizumab, but otherwise treated under the same institutional [37], French national [36], and international [41] guidelines, patients treated with eculizumab showed significantly improved survival. Improvements in key biomarkers suggest a potential mechanism of action involving improvements in oxygenation and inflammation subsequent to reduced terminal complement activation.

Serious respiratory manifestations [42] contribute to high mortality in patients with severe COVID-19; rates in patients who require mechanical ventilation range from 25% in a recent report from hospitals in the New York City region of the United States [43] to 97% in a report from Wuhan, China, early in the pandemic [38]. A randomized trial of lopinavir-ritonavir [44] showed a nonsignificant reduction in mortality at day 28 from 25% with standard care to 19% with lopinavir-ritonavir, and a small compassionate-use study of remdesivir [45] showed a mortality rate of 13% (median follow-up, 18 days); both studies included hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19, some of whom received mechanical ventilation. A phase 3 open-label trial of remdesivir, which excluded patients receiving ventilation at screening, showed overall day-14 mortality rates of 8% and 11% with 5- and 10-day treatment courses, respectively; in patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at day 5, rates were 40% and 17%, respectively [46]. Lastly, in a large trial of dexamethasone for hospitalized patients with COVID-19, mortality rates at 28 days in patients, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation and assigned to the usual care arm, was 41% [47]. In our hospital, observed mortality rates 15 and 28 days after ICU admission were 38% and 51%, respectively, and these were reduced to 17% and 20% in patients treated with eculizumab.

In preclinical studies, inhibition of complement proteins C3, C5, or their downstream products reduced lung injury after infection with highly pathogenic viruses [9–12]. Interestingly, inhibition of complement components C4 and factor B, which lie upstream from C3 and C5 in the complement pathway, appeared not to offer the same protection, indicating the importance of terminal complement blockade over inhibition of the alternative pathway [9]. Taken together with clinical reports showing over-activation of the complement system [13–15,17–21], these findings provide a rationale for blocking complement activation at C5 as a means to improve survival in severe respiratory illness without compromising the immunoprotective and immunomodulatory functions served by other components of the complement pathway.

In our study, baseline C5b-9 levels were elevated, and, at day 7, residual free eculizumab was not detectable in some patients who were treated with eculizumab, suggesting possible over-activation of the complement pathway. Similar findings were reported in a recently published case report series [34]. The unexpected rapid clearance of eculizumab suggests that higher or more frequent dosing may be appropriate in patients with severe COVID-19. In fact, 8 of the 12 patients who had detectable eculizumab levels in their serum at day 7 had received a 1200 mg dose of eculizumab on day 4. Nonetheless, the transient reduction in CH50 activity in patients who received eculizumab supports the concept that incomplete C5 inhibition is sufficient to enact clinical improvements. Reduced C5 activation represents an important mechanism for decreasing inflammation, cytokine production, and tissue damage [8,48]; and biomarker analyses suggest that the clinical improvements in patients who received eculizumab may have been mediated by reduced inflammation and improved oxygenation. Concurrent with C5b-9 reduction, patients treated with eculizumab experienced reductions in the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-17, and IFN-α2, as well as accelerated improvements in platelet count and clearance of lactate, a robust biomarker of tissue hypoxia [49]. Improvement in platelet count could be related to inhibition of complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy, a known effect of eculizumab in aHUS [24]. Based on preliminary evidence from a case series, over-activation of C5b-9 and subsequent complement-mediated microvascular injury could play an important role in severe COVID-19 [17]. Collectively, these findings suggest that C5 inhibition with eculizumab may lead to accelerated reduction of systemic and pulmonary inflammation induced by SARS-CoV-2, resulting in improved tissue oxygenation, improved survival, and more rapid resolution of severe illness. Clinical improvements observed in a small controlled study of combination therapy with eculizumab and the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib (n = 7) for moderate to severe COVID-19 suggest that targeting multiple, connected inflammatory pathways may be advantageous [50].

Serious AEs are frequent in patients treated in the ICU. Patients in this study presented with severe pneumonia, acute lung injury, or ARDS. Reported TESAEs were generally consistent with SAEs typically seen in critically ill patients treated in the ICU for COVID-19 (eg, ventilator-associated pneumonia). Overall, safety was also consistent with the approximately 10 years of safety data in patients with complement-mediated diseases (PNH, aHUS), which are not associated with the need for ventilator-assisted respiration [51]. However, it is important to note that in this patient cohort, infectious complications were more commonly reported in patients treated with eculizumab and that significantly more patients treated with eculizumab developed ventilator-associated pneumonia.

The reason for the higher rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia was not investigated and larger randomized controlled studies are needed to characterize more thoroughly the safety of eculizumab treatment in patients with severe COVID-19. One possible explanation for this finding could be that since eculizumab patients survived longer on the ventilator, their cumulative risk of developing an infection was higher. Alternatively, complement inhibition by eculizumab may have altered bacterial clearance. With the exception of the well-recognized risk of infection due to the Neisseria bacteria, however, past experience with eculizumab has not suggested an increased risk of bacterial infections [51]. Lastly, the interpretation of these safety data must be made in the context of the efficacy data. Despite the known association of ventilator-associated pneumonia with substantial mortality [52], eculizumab treatment was associated with improved survival. Thus, this increase in serious infectious complications, though noteworthy, needs to be considered in the context of severe COVID-19.

Although this proof-of-concept study has some limitations, including the small number of enrolled patients, the lack of formal randomization, and the lack of blinding, every effort was made to make the analyses more robust. In order to reduce bias, the primary outcome was prespecified and all measures recorded in the electronic health records were analyzed. In addition, patients were assigned to eculizumab treatment or no eculizumab treatment based on availability of eculizumab at the time of ICU admission. Though this was not a formal randomization process, treatment allocation was not based on a clinical decision and therefore, the potential for physician bias in the assignment of treatment groups was reduced.

Nonetheless, some numerical differences in baseline characteristics between controls and eculizumab treated patients are apparent. These differences were not statistically significant, but patients treated with eculizumab tended to be older, to have a higher SAPS II score, and to be prescribed remdisivir and/or lopinavir-ritonavir less often than patients who were not treated with eculizumab. By contrast, fewer patients in the eculizumab group than in the control group had a baseline PaO2/FiO2 ≤100 mmHg. Assessing the impact of these differences on outcomes is difficult in such a small trial; and larger, randomized controlled studies are needed to support the results of this proof-of-concept study.

As the enrollment period (March 10-May 5, 2020) was dictated by external considerations and no power calculations were performed, the study may not have been sufficiently powered to detect a significant difference in the secondary analyses. However, a significant difference was found for the prespecified analysis, suggesting that these findings are worthy of follow-up.

Although this work was performed in a single institution, which may limit generalizability, this helped to ensure consistency of care for all patients and highlights the importance of defining institutional and national guidelines. Nevertheless, there is the potential for unidentified confounding variables, including nonspecific immune effects related to receipt of vaccines and antibiotics.

In conclusion, in this single-institution, proof-of-concept study, eculizumab treatment for patients with severe COVID-19 may have increased survival and may have accelerated improvement of biomarkers of tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Our data also suggest that treatment with eculizumab may be associated with an increased risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Though in our study, the survival and clinical improvement benefits outweighed the risks of developing ventilator-associated infections with eculizumab treatment, larger, randomized studies are needed to perform a more extensive risk:benefit analysis. Because this was a nonrandomized, proof-of-concept study, with the attendant limitations of a cohort study design, any conclusions drawn from statistical comparisons are meant to be hypothesis generating and to inform a more rigorous study in the future. These preliminary findings may form the basis for a larger clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of C5 inhibition in the treatment of patients with severe COVID-19, either alone or in combination with other agents. Indeed, 3 studies of eculizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT04288713, NCT04355494, NCT04346797) and 2 studies of ravulizumab (NCT04369469, NCT04390464) for COVID-19 are either ongoing or planned.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Djillali Annane: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. and grants from Programme d'Investissements d'Avenir during the conduct of the study; other (investigator) from Alexion outside the submitted work.

Nicholas Heming: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study; other (investigator) from Alexion outside the submitted work.

Lamiae Grimaldi-Bensouda: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Véronique Frémeaux-Bacchi: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Alexion, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Apellis, and personal fees from Biocryps outside the submitted work.

Marie Vigan: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Anne-Laure Roux: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Armance Marchal: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Hugues Michelon: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc, during the conduct of the study.

Martin Rottman: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Pierre Moine: reports non-financial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study; non-financial support and other (investigator) from Alexion outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work is part of Fédérations Hospitalo-universitaires (FHU) Saclay and Paris Seine Nord Endeavour to PerSonalize Interventions for Sepsis (SEPSIS) and Recherche Hospitalo-Universitaire en santé (RHU) Rapid rEcognition of CORticosteroiD resistant or sensitive Sepsis (RECORDS), which are funded by the French government through the Programme d'Investissements d'Avenir, project number ANR-18-RHUS60004. Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provided eculizumab for emergency treatment as part of their expanded access program: Alexion funded medical writing and editorial support for development of this manuscript, which was provided under the direction of the authors by Krystina Neuman, PhD and Nicole Strangman, PhD at ICON plc (North Wales, PA) and by Hélène Dassule, PhD (Lexington, MA).

Acknowledgments

Krystina Neuman, PhD, and Nicole Strangman, PhD, at ICON plc (North Wales, PA) helped writing and developing this manuscript and Hélène Dassule, PhD (Lexington, MA) helped to make revisions and write responses to reviewer comments. Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., reviewed the manuscript for technical accuracy related to statements about eculizumab.

Data Sharing

The complete deidentified patient data set will be shared with researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved and will be made available with publication of the manuscript. Proposals should be submitted to Prof. Djillali Annane (djillali.annane@aphp.fr); to gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100590.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 2.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVIDView: a weekly surveillance summary of U.S. COVID-19 Activity, key updates for week 12, ending May 30, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 4.Santé Publique France. Infection au nouveau Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), COVID-19, France et Monde. Available at: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/articles/infection-au-nouveau-coronavirus-sars-cov-2-covid-19-france-et-monde. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 5.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Q., Wang B., Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the `Cytokine Storm' in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;80:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandya P.H., Wilkes D.S. Complement system in lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:467–473. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0485TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R., Xiao H., Guo R., Li Y., Shen B. The role of C5a in acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic viral infections. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015;4:e28. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gralinski L.E., Sheahan T.P., Morrison T.E. Complement activation contributes to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathogenesis. MBio. 2018;9:e01753. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01753-18. -18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun S., Zhao G., Liu C. Inhibition of complement activation alleviates acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:221–230. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0428OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y., Zhao G., Song N. Blockade of the C5a-C5aR axis alleviates lung damage in hDPP4-transgenic mice infected with MERS-CoV. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7:77. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0063-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun S., Zhao G., Liu C. Treatment with anti-C5a antibody improves the outcome of H7N9 virus infection in African green monkeys. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:586–595. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang R.T., Poon T.C., Chan K.C. Serum proteomic fingerprints of adult patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem. 2006;52:421–429. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.061689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohta R., Torii Y., Imai M., Kimura H., Okada N., Ito Y. Serum concentrations of complement anaphylatoxins and proinflammatory mediators in patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza. Microbiol Immunol. 2011;55:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berdal J.E., Mollnes T.E., Wæhre T. Excessive innate immune response and mutant D222G/N in severe A (H1N1) pandemic influenza. J Infect. 2011;63:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y.H., Huang Y.H., Chuang Y.H. Autoantibodies against human epithelial cells and endothelial cells after severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus infection. J Med Virol. 2005;77:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magro C., Mulvey J.J., Berlin D. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cugno M., Meroni P.L., Gualtierotti R. Complement activation in patients with COVID-19: a novel therapeutic target. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.006. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam L.M., Murphy S.J., Kuri-Cervantes L. Erythrocytes reveal complement activation in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.20.20104398v1. [preprint] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramlall V., Thangaraj P., Tatonetti N.P., Shapira S.D. Identification of immune complement function as a determinant of adverse SARS-CoV-2 infection outcome. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20092452. ; [preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rambaldi A., Gritti G., Micò M.C. Endothelial Injury and Thrombotic Microangiopathy in COVID-19: treatment with the Lectin-Pathway Inhibitor Narsoplimab. Immunobiology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2020.152001. 152001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carvelli J., Demaria O., Vély F. Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a-C5aR1 axis. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillmen P., Young N.S., Schubert J. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1233–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legendre C.M., Licht C., Muus P. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2169–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittock S.J., Berthele A., Fujihara K. Eculizumab in aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:614–625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard J.F., Jr., Utsugisawa K., Benatar M. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:976–986. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SOLIRIS (eculizumab) Alexion Europe SAS; Levallois-Perret, France: 2019. Summary of product characteristics. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merle N.S., Noe R., Halbwachs-Mecarelli L., Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Roumenina L.T. Complement system part II: role in immunity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:257. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan B.P., Walters D., Serna M., Bubeck D. Terminal complexes of the complement system: new structural insights and their relevance to function. Immunol Rev. 2016;274:141–151. doi: 10.1111/imr.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matis L.A., Rollins S.A. Complement-specific antibodies: designing novel anti-inflammatories. Nat Med. 1995;1:839–842. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diurno F., Numis F.G., Porta G. Eculizumab treatment in patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from real life ASL Napoli 2 Nord experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:4040–4047. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitts T.C. A preliminary update to the Soliris to Stop Immune Mediated Death in Covid-19 (SOLID-C19) compassionate use study. Hudson Medical. Available at: https://hudsonmedical.com/articles/soliris-stop-death-covid-19/. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- 33.Kulasekararaj A.G., Lazana I., Large J. Terminal complement inhibition dampens the inflammation during COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:e141–ee43. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peffault de Latour R., Bergeron A., Lengline E. Complement C5 inhibition in patients with COVID-19 - a promising target? Haematologica. 2020 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.260117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrials.gov. SOLIRIS® (Eculizumab) Treatment of Participants With COVID-19 (NCT04355494). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04355494, 2020.

- 36.Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Dans les établissements de santé: recommandations COVID-19 et prise en charge. Available at: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-infectieuses/coronavirus/professionnels-de-sante/article/dans-les-etablissements-de-sante-recommandations-covid-19-et-prise-en-charge Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 37.Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris. COVID-19 Réanimation et soins critiques. Available at: http://covid-documentation.aphp.fr/reanimation/. Accessed August 3, 2020.

- 38.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. ; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.European Medicines Agency. Guidance on the management of clinical trials during the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, version 2 (27/03/2020). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-10/guidanceclinicaltrials_covid19_en.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 40.Le Gall J.R., Lemeshow S., Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–2963. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Caironi P. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. ; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman J.D., Lye D.C.B., Hui D.S. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. ; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keshari R.S., Silasi R., Popescu N.I. Inhibition of complement C5 protects against organ failure and reduces mortality in a baboon model of Escherichia coli sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:E6390–E6E99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706818114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakker J., Nijsten M.W.N., Jansen T.C. Clinical use of lactate monitoring in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:12. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giudice V., Pagliano P., Vatrella A. Combination of ruxolitinib and eculizumab for treatment of severe SARS-CoV-2-related acute respiratory distress syndrome: a controlled study. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:857. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Socie G., Caby-Tosi M.P., Marantz J.L. Eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria and atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: 10-year pharmacovigilance analysis. Br J Haematol. 2019;185:297–310. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melsen W.G., Rovers M.M., Groenwold R.H. Attributable mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised prevention studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:665–671. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.