Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Excessive iron intake has been linked to diabetes risk. However, the evidence is inconsistent. This study examined the association between dietary heme and nonheme iron intake and diabetes risk in the Chinese population.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We included 17,026 adults (8,346 men and 8,680 women) who were part of the China Health and Nutrition Survey (1991–2015) prospective cohort. Dietary intake was measured by three consecutive 24-h dietary recalls combined with a household food inventory. Diabetes cases were identified through a questionnaire. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

RESULTS

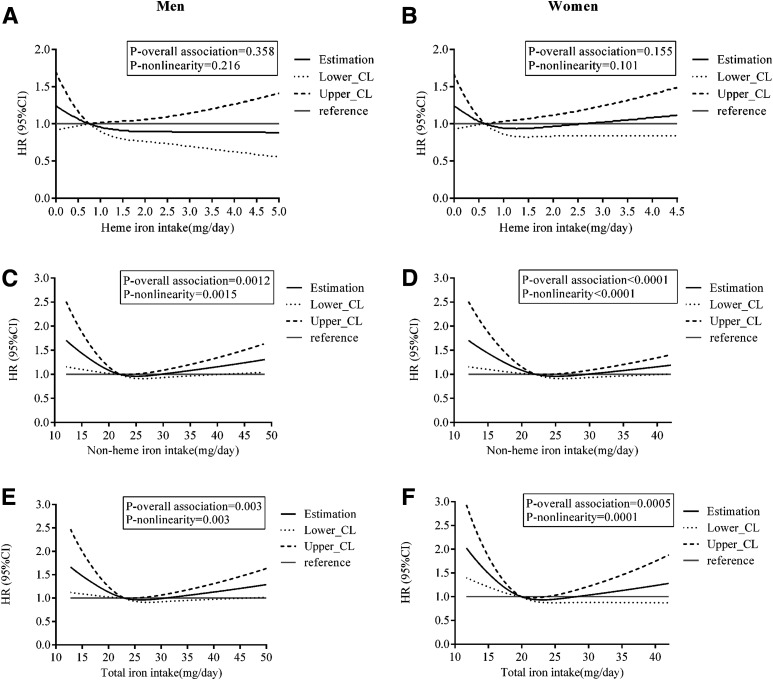

A total of 547 men and 577 women developed diabetes during 202,138 person-years of follow-up. For men, the adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for quintiles of nonheme iron intake were 1.00, 0.77 (0.58–1.02), 0.72 (0.54–0.97), 0.63 (0.46–0.85), and 0.87 (0.64–1.19) (P-nonlinearity = 0.0015). The corresponding HRs (95% CIs) for women were 1.00, 0.63 (0.48–0.84), 0.57 (0.43–0.76), 0.58 (0.43–0.77), and 0.67 (0.49–0.91) (P-nonlinearity < 0.0001). The dose-response curves for the association between nonheme iron and total iron intake and diabetes followed a reverse J shape in men and an L shape in women. No significant associations were observed between heme iron intake and diabetes risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Total iron and nonheme iron intake was associated with diabetes risk, following a reverse J-shaped curve in men and an L-shaped curve in women. Sufficient intake of nonheme or total iron might be protective against diabetes, while excessive iron intake might increase the risk of diabetes among men.

Introduction

Diet plays an important role in the development of diabetes (1). In addition to the role of macronutrients (2), excessive iron intake has been linked with an increased risk of diabetes (3). Iron is a critical element, participating in many vital cellular functions, including constitution of hemoglobin, oxygen delivery to tissues, DNA synthesis, mitochondrial electron transport, and muscle function (4). However, free iron is toxic. It damages cellular macromolecules and promotes cell death and tissue injury through the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reaction (5). In previous studies, excess accumulation of iron and associated oxidative stress (which can damage the islet cells, affect insulin secretion, and exacerbate insulin resistance) have been proposed as possible mechanisms of iron-induced diabetes (3,6).

The association between iron and diabetes was first reported in patients with a genetic iron-overload disorder, specifically, hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) (7). The prevalence of diabetes among patients with HH ranges from 25 to 60% (8). Nevertheless, other studies revealed that moderately elevated iron levels, within a range significantly lower than seen in patients with HH, were associated with impaired insulin sensitivity and increased risk of diabetes among otherwise healthy individuals (9,10). However, available evidence is inconsistent. For example, some studies (11,12) have observed nonlinear relationships between ferritin and diabetes risk; the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (13), following adjustment for metabolic syndrome components, reported a negative association between ferritin and diabetes risk.

Many epidemiological studies have explored the association between intake of dietary iron and risk of diabetes. Two systematic reviews (14,15), including four and five prospective studies, respectively, concluded that higher heme iron intake is associated with a greater risk of type 2 diabetes. In contrast, evidence from prospective studies for the association between diabetes and total dietary iron and nonheme iron intake is mixed. In fact, some studies reported no association (16–18), while others reported a positive association (19,20), and yet another reported a negative association (21). Among these studies, two (19,22) involved the Chinese population. Results from participants based in the Jiangsu province (19) showed that heme iron (in men and women) and total iron (in men) intake were positively associated with the risk of hyperglycemia. Moreover, results from Chinese descendants based in Singapore (22) showed heme iron, but not nonheme iron, to be associated with a higher risk of diabetes. In addition, a study involving the Japanese population (20) reported that dietary intake of total and nonheme iron, but not heme iron, was positively associated with the risk of diabetes.

Populations of Western countries tend to consume animal-based diets, while populations of Eastern countries, such as China, tend to consume plant-based diets, characterized by higher quantities of vegetables and fruits, and lower quantities of animal-based products. This type of diet has been referred to as a “protective dietary pattern” against diabetes (23). According to our calculations, heme iron constitutes ∼4% of the total iron intake in a Chinese diet (24), which is much lower than 10–15% previously reported for Western diets (25). Despite these estimates, the two studies that were based on Chinese populations (19,22) reported that heme iron accounted for >10% of the total iron intake. Because the participants of these studies either were from an economically developed region of China or had settled in a developed country, we believe that these results are not representative of a typical Chinese diet. Therefore, the current study aimed to prospectively examine the association between heme and nonheme iron intake and diabetes risk in a large sample in China that consumes a predominantly plant-based diet.

Research Design and Methods

Study Population

The current study used data from a subcohort of the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS). CHNS is an ongoing, open, prospective cohort study in China, with a total of 10 rounds already completed. The survey was approved by institutional review boards at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill, NC), and the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Beijing, China), and each participant provided written informed consent. The cohort profile is described elsewhere (26).

CHNS included 36,387 participants with disease history and physical examination data available from 1991 to 2015. The current study included adult participants aged ≥18 years. We excluded participants who were pregnant, nursing, or disabled; had unavailable or incomplete diabetes information; or were lost to follow-up after the baseline or first survey entry in 2015. We also excluded participants with missing or implausible energy intake information (>5,000 or <700 kcal/day), a baseline diagnosis of diabetes, or a history of stroke, myocardial infarction, or any type of tumor at baseline. These diagnoses were excluded because they can lead to changes in diet and lifestyle. Finally, a total of 8,346 men and 8,680 women were included (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Assessment of Dietary Intake

Dietary intake assessment in CHNS involved three consecutive 24-h dietary recalls for participating individuals and a household food inventory, which involved the weighing and measuring of products (used to obtain information on edible oils and condiments consumption) over the same 3 days (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day). All field workers were trained nutritionists professionally engaged in nutrition work in their own counties who also had participated in other national surveys. A study that evaluated the accuracy of the dietary assessment method used in this survey compared with the household food inventory weighing method reported a 1% relative difference (74 kcal/day) for total energy (TE) intake between these two methods (27).

Nutrient intake was estimated by multiplying the consumed volume of each food item by the nutrient content of a standard portion size (100 g, on the basis of the Chinese Food Composition Tables [28–31]) before nutrient intake for all food items was summed. Heme iron was estimated as 40% (32) of the total iron available in meat items, including livestock, poultry, and fish (offal items were included in the corresponding meat group). After log-transformation, the intake of each nutrient or food group was adjusted for TE intake for men (2,451 kcal/day) and women (2,090 kcal/day) using the residual method (33). In the analyses, cumulative average intake values of each nutrient from baseline to the survey before outcome identification were used to reduce within-subject variation and best represent long-term dietary intake.

Measurement of Nondietary Risk Factors for Diabetes

Demographic and lifestyle information was obtained through questionnaires, including age, residence area (urban, rural), highest education level (low [primary school and lower], middle [lower middle school, upper middle school, and technical or vocational school], high [college, university, and higher]), smoking status (former or current, never), and alcohol consumption (yes, no). Body weight and height were measured by well-trained investigators who followed standard measuring procedures (34). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Physical activity level (PAL) was quantified into multiples of basal metabolic rate (BMR) in our analysis: 1.3 × BMR for very light (for both sexes), 1.6 and 1.5 × BMR for light, 1.7 and 1.6 × BMR for moderate, 2.1 and 1.9 × BMR for heavy, and 2.4 and 2.2 × BMR for very heavy in men and women, respectively. Per capita annual household income was divided into quartiles (low, medium, high, very high). For all nondietary covariates, we used the baseline year measure.

Outcome Identification

The participants had been asked to report their previous history of diabetes with a questionnaire-based interview at each follow-up since 1997. The questions were posed as follows: 1) “Has a doctor ever told you that you suffer from diabetes? If yes, 2) how old were you when the doctor told you about such a situation (years), and 3) did you use any of the following treatments, such as special diet, weight control, oral medicine, injection of insulin, Chinese traditional medicine, home remedies, or qigong (or spiritual treatment)?” For each survey, diagnosis of diabetes was confirmed if at least one of the three answers was yes. In addition, blood samples were collected and assayed, and the data were available only in 2009. Therefore, an additional fourth criterion (i.e., fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥6.5% [48 mmol/mol]) (35) was added for outcome ascertainment in 2009. As such, if at least one of the three answers concerning diabetes was yes or the fourth criterion was met, diabetes diagnosis was ascertained in 2009. Information on incident diabetes before 1997 was indirectly deduced from answers to subsequent questionnaires returned by the same individual. If multiple or inconsistent records regarding incident diabetes were present, we kept only the first record to minimize recall bias.

Statistical Analysis

We performed all the analyses separately for men and women. We also divided participants of each sex into five groups according to quintiles of dietary heme and nonheme iron intake. In the descriptive analyses, we calculated means (SDs) and medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]) for continuous variables and counts (percentages) for categorical variables. For tests of linear trend across quintiles, we used linear regression for continuous variables (with the median intake of each quintile as the variable included in the model) and χ2 with linear-by-linear association test for categorical variables.

We set the baseline for each participant as the year of his or her first entry into the survey with a complete dietary record. The follow-up person-time for each participant was calculated from baseline until a first diabetes diagnosis, the last survey round before the participant’s departure from the survey, or the end of the latest survey (2015), whichever came first. We calculated incidence rates for diabetes by dividing the number of new diabetes cases by person-years of follow-up in each quintile.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% CIs for developing diabetes, adjusting for potential confounders that were frequently controlled in previous prospective studies that explored the relation between iron intake and diabetes risk. The Cox models were stratified by the year participants entered this study. To test the proportional hazards assumption, we conducted likelihood ratio tests to assess the significance of interaction terms of categories of intake and log-transformed follow-up time. No significant outcome was found concerning dietary exposures, which indicated that HRs for exposures remained reasonably constant over time. For the calculation of HRs among quintiles, the lowest intake quintiles were used as reference. Models were adjusted for covariates in a stepwise procedure. Model 1 was adjusted for age, BMI, and dietary intake of TE. Model 2 was further adjusted for other nondietary factors, including residence area, highest education level, household income level, PAL, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and history of hypertension at baseline. Model 3 was further adjusted for dietary intake of carbohydrates, protein, ratio of monounsaturated fat (MUFA)-to-saturated fat (SFA) intake, ratio of polyunsaturated fat (PUFA)-to-SFA intake, cholesterol, magnesium, cereal fiber, vegetables, and fruits. Mutual adjustment was performed for dietary heme iron and nonheme iron intake. Tests for trend for HRs were conducted using the median value for each quintile of intake as a continuous variable.

To evaluate the potential effect modification, we conducted stratified analyses according to age (<50 or ≥50 years), BMI (<24 or ≥24 kg/m2), smoking status (ever and current, or never), and alcohol consumption (yes or no). For each factor, we generated a multiplicative term by multiplying the median value of iron intake (mg/day) by dichotomized variables used in the multivariable model, assessing interactions with a likelihood ratio test.

We also used restricted cubic splines (RCS) to test for linearity and explore the shape of the dose-response association between dietary heme, nonheme, and total iron intake and diabetes risk in the multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analyses (model 3) for men and women, separately. We kept the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles as the knots and set the median intake as the reference. The SAS macro program %RCS_Reg for curve fitting was provided by Desquilbet and Mariotti (36).

All P values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS for Windows version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL) software.

Results

The present analysis included 17,026 participants. The median intake of total, heme, and nonheme iron was 23.0, 0.75, and 22.0 mg/day among men, and 20.0, 0.63, and 19.1 mg/day among women, respectively. At baseline, men with higher heme iron intake had a higher BMI, lower PAL, and higher education and income levels and were more likely to be urban residents and alcohol consumers. Men with higher nonheme iron intake had a higher BMI, lower income level, and higher prevalence of hypertension and were more likely to be urban residents (Table 1). Among women, the distributions of nondietary factors were mainly similar to that among men. Additional findings were that women with higher heme iron intake were less likely to be former or current smokers. Higher nonheme iron intake was also associated with higher prevalence of hypertension in women, but the opposite association was observed for heme iron intake (Table 2). In both men and women, the intakes of most other nutrients all increased with quintiles of heme iron intake, except that intakes of TE, carbohydrates, magnesium, and cereals fiber decreased. With increased quintiles of nonheme iron intake, the intakes of most other nutrients also increased, except that intakes of SFA, PUFA, MUFA, and heme iron decreased in both sexes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of baseline demographic and lifestyle factors and cumulative average food and nutrient intake according to quintiles of dietary intake of heme iron and nonheme iron in men (n = 8,346)*

| Quintiles of heme iron intake | Quintiles of nonheme iron intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | P-trend† | 1 | 3 | 5 | P-trend† | |

| Age (years) | 38.8 ± 15.6 | 39.9 ± 15.7 | 39.4 ± 14.8 | 0.475 | 40 ± 15.8 | 39 ± 14.7 | 40.1 ± 15.7 | 0.538 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8 ± 2.9 | 22.3 ± 3.3 | 22.8 ± 3.4 | <0.0001 | 22 ± 3.4 | 22.3 ± 3 | 22.6 ± 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| PAL (× BMR) | 1.96 ± 0.26 | 1.74 ± 0.32 | 1.64 ± 0.28 | <0.0001 | 1.77 ± 0.31 | 1.77 ± 0.32 | 1.76 ± 0.32 | 0.690 |

| Urban residence area | 237 (7.7) | 669 (21.8) | 903 (29.4) | <0.0001 | 494 (16.1) | 680 (22.1) | 698 (22.7) | <0.0001 |

| Education level | <0.0001 | 0.869 | ||||||

| Low | 867 (29.9) | 535 (18.4) | 365 (12.6) | 600 (20.7) | 561 (19.3) | 564 (19.4) | ||

| Medium | 773 (16.0) | 989 (20.4) | 1,107 (22.9) | 931 (19.2) | 987 (20.4) | 972 (20.1) | ||

| High | 29 (4.8) | 145 (24.0) | 198 (32.8) | 138 (22.8) | 121 (20.0) | 134 (22.2) | ||

| Household income level | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Low | 890 (37.0) | 419 (17.4) | 242 (10.1) | 455 (18.9) | 466 (19.4) | 523 (21.7) | ||

| Medium | 453 (20.4) | 468 (21.1) | 377 (17.0) | 432 (19.4) | 436 (19.6) | 406 (18.3) | ||

| High | 218 (11.5) | 413 (21.7) | 447 (23.5) | 363 (19.1) | 412 (21.7) | 361 (19.0) | ||

| Very high | 108 (6.0) | 369 (20.3) | 604 (33.3) | 419 (23.1) | 355 (19.6) | 380 (20.9) | ||

| Former or current smoker | 1,087 (20.9) | 1,008 (19.4) | 1,060 (20.4) | 0.242 | 1,039 (20.0) | 1,061 (20.4) | 1,033 (19.9) | 0.475 |

| Alcohol consumer | 969 (18.6) | 1,049 (20.2) | 1,081 (20.8) | 0.002 | 1,023 (19.7) | 1,065 (20.5) | 1,009 (19.4) | 0.734 |

| Hypertension | 327 (18.8) | 351 (20.2) | 346 (19.9) | 0.963 | 331 (19.0) | 344 (19.8) | 380 (21.8) | 0.001 |

| TE (kcal) | 2,509.2 ± 591.3 | 2,417.6 ± 539.7 | 2,378.4 ± 564.6 | <0.0001 | 2,409.9 ± 572.7 | 2,436.8 ± 525.3 | 2,460.7 ± 616.5 | 0.0002 |

| Carbohydrates (%TE) | 69.1 ± 8.3 | 56.6 ± 8.1 | 50.1 ± 9.8 | <0.0001 | 55.8 ± 11.9 | 57.9 ± 9.9 | 59.4 ± 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| Protein (%TE) | 11.1 ± 1.6 | 12 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 12.3 ± 2 | 13.4 ± 2.6 | <0.0001 |

| SFA (%TE) | 3.8 ± 2 | 7.2 ± 2.4 | 8.5 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 | 7.4 ± 3.4 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 6.2 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 |

| PUFA (%TE) | 5.9 ± 3.7 | 6.9 ± 3.7 | 7.1 ± 3.9 | <0.0001 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 6.9 ± 3.4 | 6.2 ± 3.6 | 0.002 |

| MUFA (%TE) | 6.6 ± 3.2 | 12.3 ± 3.6 | 14.5 ± 4.4 | <0.0001 | 13.2 ± 4.9 | 11.5 ± 4.4 | 10.3 ± 4.7 | <0.0001 |

| PUFA/SFA | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| MUFA/SFA | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 | 2 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Heme iron (mg/day) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.15) | 0.75 (0.66, 0.85) | 2.16 (1.82, 2.82) | <0.0001 | 0.85 (0.45, 1.32) | 0.76 (0.34, 1.46) | 0.70 (0.20, 1.56) | <0.0001 |

| Nonheme iron (mg/day) | 24.2 ± 8.7 | 22.1 ± 6 | 23.9 ± 7.7 | 0.259 | 16.4 ± 2.1 | 22 ± 0.6 | 32.6 ± 11.8 | <0.0001 |

| Iron (mg/day) | 24.2 ± 8.7 | 22.9 ± 6 | 26.6 ± 8.2 | <0.0001 | 17.4 ± 2.3 | 23.1 ± 1.1 | 33.8 ± 12 | <0.0001 |

| Magnesium (mg/day) | 379.9 ± 85 | 328.5 ± 60.3 | 326.7 ± 67.3 | <0.0001 | 298.4 ± 72 | 334.2 ± 51.2 | 391.6 ± 86.2 | <0.0001 |

| Cereals fiber (g/day) | 7.6 (4.4, 11.9) | 3.7 (3.0, 5.3) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.6) | <0.0001 | 3.3 (2.6, 4.2) | 3.9 (2.9, 6.3) | 4.3 (2.8, 8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/day) | 62.5 (17.2, 147.1) | 211.0 (140.3, 313.7) | 320.6 (238.3, 439.2) | <0.0001 | 194.1 (110.4, 301.1) | 229.9 (135.7, 337.9) | 208.3 (84, 344.9) | 0.006 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 323.5 ± 187.9 | 318 ± 169.5 | 318.7 ± 168.2 | 0.963 | 278 ± 115.2 | 323.8 ± 133.1 | 372.8 ± 272.1 | <0.0001 |

| Fruits (g/day) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 40.6) | 3.1 (0.0, 48.5) | <0.0001 | 0.0 (0.0, 18.8) | 0.0 (0.0, 40.9) | 0.0 (0.0, 30.8) | 0.0003 |

Data are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (IQR).

Information on nondietary factors was collected at baseline, and dietary data were estimated as energy-adjusted cumulative average intake from baseline and follow-up periods.

We used linear regressions to test the linear trends for continuous variables (with the median intake of heme or nonheme iron as continuous variables included in the regression models). We used χ2 with linear-by-linear association tests to test the linear trends for categorical variables.

Table 2.

Characteristics of baseline demographic and lifestyle factors and cumulative average food and nutrient intake according to quintiles of dietary intake of heme iron and nonheme iron in women (n = 8,680)*

| Quintiles of heme iron intake | Quintiles of nonheme iron intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | P-trend† | 1 | 3 | 5 | P-trend† | |

| Age (years) | 41 ± 15.9 | 40.8 ± 14.7 | 40.1 ± 14.7 | 0.217 | 41.1 ± 15.9 | 40.3 ± 14.4 | 41.2 ± 15.1 | 0.367 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5 ± 3.3 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | 0.786 | 22.1 ± 3.4 | 22.5 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| PAL (× BMR) | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 | 1.61 ± 0.24 | 1.63 ± 0.24 | 1.61 ± 0.24 | 0.763 |

| Urban residence area | 312 (9.4) | 688 (20.7) | 958 (28.8) | <0.0001 | 516 (15.5) | 700 (21.1) | 752 (22.6) | <0.0001 |

| Education level | <0.0001 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Low | 1,151 (27.6) | 800 (19.2) | 548 (13.1) | 600 (20.7) | 561 (19.3) | 564 (19.4) | ||

| Medium | 558 (13.9) | 845 (21.1) | 1,018 (25.4) | 931 (19.2) | 987 (20.4) | 972 (20.1) | ||

| High | 27 (5.4) | 91 (18.2) | 170 (34.0) | 138 (22.8) | 121 (20.0) | 134 (22.2) | ||

| Household income level | <0.0001 | 0.072 | ||||||

| Low | 894 (36.6) | 418 (17.1) | 230 (9.4) | 483 (19.8) | 482 (19.7) | 484 (19.8) | ||

| Medium | 445 (19.4) | 491 (21.4) | 413 (18.0) | 442 (19.2) | 472 (20.5) | 432 (18.8) | ||

| High | 250 (12.3) | 425 (21.0) | 483 (23.8) | 387 (19.1) | 438 (21.6) | 398 (19.6) | ||

| Very high | 147 (7.7) | 402 (21.0) | 610 (31.9) | 424 (22.2) | 344 (18.0) | 422 (22.1) | ||

| Former or current smoker | 105 (29.0) | 76 (21.0) | 35 (9.7) | <0.0001 | 63 (17.4) | 78 (21.5) | 71 (19.6) | 0.324 |

| alcohol consumer | 159 (15.5) | 227 (22.1) | 223 (21.8) | 0.0001 | 197 (19.2) | 211 (20.6) | 224 (21.9) | 0.126 |

| Hypertension | 348 (24.0) | 281 (19.4) | 247 (17.1) | <0.0001 | 252 (17.4) | 288 (19.9) | 310 (21.4) | 0.002 |

| TE (kcal) | 2,061.7 ± 536.5 | 2,034.3 ± 475.4 | 1,981.2 ± 492.9 | <0.0001 | 2,006.8 ± 525.9 | 2,026.3 ± 464.3 | 2,049.2 ± 558 | 0.006 |

| Carbohydrates (%TE) | 68.6 ± 8.1 | 57.3 ± 7.8 | 50.9 ± 9.1 | <0.0001 | 56.9 ± 10.7 | 58.6 ± 9.6 | 59.4 ± 11.1 | <0.0001 |

| Protein (%TE) | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 12.2 ± 1.7 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | <0.0001 | 11.6 ± 2.2 | 12.4 ± 2 | 13.7 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 |

| SFA (%TE) | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 8.6 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 | 7.3 ± 3.3 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | <0.0001 |

| PUFA (%TE) | 6.2 ± 3.7 | 7.2 ± 3.8 | 7.4 ± 3.9 | <0.0001 | 7 ± 4.5 | 7.3 ± 3.8 | 6.7 ± 3.8 | 0.001 |

| MUFA (%TE) | 7 ± 3.3 | 12.4 ± 3.6 | 14.7 ± 4.4 | <0.0001 | 13.1 ± 4.8 | 11.5 ± 4.4 | 10.7 ± 4.8 | <0.0001 |

| PUFA/SFA | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| MUFA/SFA | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 | 2 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Heme iron (mg/day) | 0.06 (0.00, 0.13) | 0.63 (0.55, 0.71) | 1.76 (1.49, 2.35) | <0.0001 | 0.68 (0.35, 1.12) | 0.61 (0.27, 1.10) | 0.56 (0.19, 1.25) | <0.0001 |

| Nonheme iron (mg/day) | 20.7 ± 5 | 19.3 ± 5 | 20.9 ± 7.1 | 0.038 | 14.5 ± 1.7 | 19.2 ± 0.5 | 27.8 ± 7.2 | <0.0001 |

| Iron (mg/day) | 20.8 ± 5 | 19.9 ± 5 | 23.2 ± 8.1 | <0.0001 | 15.3 ± 1.8 | 20 ± 0.9 | 28.9 ± 8.1 | <0.0001 |

| Magnesium (mg/day) | 326.4 ± 71.7 | 291.2 ± 55.4 | 290.8 ± 61.7 | <0.0001 | 262.2 ± 59.5 | 292.5 ± 42.9 | 348.8 ± 77.2 | <0.0001 |

| Cereals fiber (g/day) | 6.5 (3.7, 10.1) | 3.1 (2.5, 4.5) | 2.4 (1.9, 3.0) | <0.0001 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.8) | 3.3 (2.4, 5.6) | 3.5 (2.4, 7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/day) | 67.6 (17.9, 147.7) | 194.4 (120.3, 286.4) | 276.5 (199.9, 384.6) | <0.0001 | 172.3 (97.7, 266.5) | 200.0 (116.8, 298.6) | 191.6 (85.6, 321) | <0.0001 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 296.8 ± 194.7 | 293.9 ± 149.3 | 301.7 ± 156.2 | 0.422 | 250.8 ± 105.2 | 294 ± 121 | 370.1 ± 332.1 | <0.0001 |

| Fruits (g/day) | 0.0 (0.0, 11.7) | 8.8 (0.0, 53.4) | 16.7 (0.0, 68.2) | <0.0001 | 0.0 (0.0, 37.5) | 10.4 (0.0, 50.5) | 0.0 (0.0, 51.9) | 0.002 |

Data are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (IQR).

Information on nondietary factors was collected at baseline, and dietary data were estimated as energy-adjusted cumulative average intake from baseline and follow-up periods.

We used linear regressions to test the linear trends for continuous variables (with the median intake of heme or nonheme iron as continuous variables included in the regression models). We used χ2 with linear-by-linear association tests to test the linear trends for categorical variables.

During a median of 11 years of follow-up (202,138 person-years), we ascertained that 547 men and 577 women developed diabetes. The median age for men and women when first diagnosed with diabetes was 55 and 59 years, respectively. We observed that heme iron intake was not significantly associated with diabetes risk in either sex (Table 3). After adjusting for nondietary and dietary factors, nonheme iron intake negatively correlated with diabetes risk in women, which was marginally significant (P-trend = 0.080). In men, HRs (1.00, 0.77, 0.72, 0.63, 0.87) across quintiles of intake suggested a negative association, but the P-trend of 0.683 suggested that a linear trend between nonheme iron and diabetes risk was not statistically significant. For total iron intake, the results were similar to that of nonheme iron intake (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diabetes risk according to quintiles of cumulative average dietary intakes of heme, nonheme, and total iron in men (n = 8,346) and women (n = 8,680)

| Quintiles of intake in men | Quintiles of intake in women | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 1,669) | 2 (n = 1,669) | 3 (n = 1,669) | 4 (n = 1,669) | 5 (n = 1,669) | P- trend | 1 (n = 1,736) | 2 (n = 1,736) | 3 (n = 1,736) | 4 (n = 1,736) | 5 (n = 1,736) | P- trend | |

| Heme iron | ||||||||||||

| Median intake (mg/day)* | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.75 | 1.21 | 2.16 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 1.76 | ||

| Cases/person-years | 115/21,486 | 124/22,053 | 106/20,463 | 112/19,477 | 90/17,287 | 152/21,389 | 115/22,202 | 118/20,725 | 102/19,484 | 90/17,569 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 0.96 (0.75–1.24) | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) | 1.02 (0.79–1.33) | 0.96 (0.73–1.27) | 0.97 | 1 (ref) | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.73 (0.57–0.95) | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) | 0.518 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 0.84 (0.63–1.12) | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | 0.167 | 1 (ref) | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) | 0.76 (0.57–1.02) | 0.118 |

| Model 3 | 1 (ref) | 0.86 (0.64–1.15) | 0.75 (0.53–1.07) | 0.77 (0.53–1.14) | 0.68 (0.44–1.05) | 0.155 | 1 (ref) | 0.74 (0.56–0.97) | 0.78 (0.56–1.07) | 0.68 (0.47–0.98) | 0.84 (0.56–1.26) | 0.982 |

| Nonheme iron | ||||||||||||

| Median intake (mg/day) | 17 | 19.91 | 22.02 | 24.48 | 29.29 | 14.97 | 17.39 | 19.14 | 21.26 | 25.38 | ||

| Cases/person-years | 95/17,678 | 104/21,419 | 110/21,397 | 107/21,754 | 131/18,518 | 106/17,324 | 99/21,069 | 105/22,265 | 133/22,193 | 134/18,518 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 0.75 (0.57–1.00) | 0.69 (0.52–0.92) | 1.02 (0.78–1.34) | 0.486 | 1 (ref) | 0.67 (0.51–0.88) | 0.65 (0.50–0.86) | 0.72 (0.56–0.94) | 1.00 (0.77–1.29) | 0.247 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 0.76 (0.58–1.01) | 0.73 (0.55–0.97) | 0.68 (0.51–0.90) | 0.99 (0.76–1.30) | 0.615 | 1 (ref) | 0.65 (0.49–0.86) | 0.62 (0.47–0.82) | 0.71 (0.55–0.93) | 0.98 (0.76–1.27) | 0.257 |

| Model 3 | 1 (ref) | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 0.72 (0.54–0.97) | 0.63 (0.46–0.85) | 0.87 (0.64–1.19) | 0.683 | 1 (ref) | 0.63 (0.48–0.84) | 0.57 (0.43–0.76) | 0.58 (0.43–0.77) | 0.67 (0.49–0.91) | 0.080 |

| Total iron | ||||||||||||

| Median intake (mg/day) | 17.92 | 20.86 | 23.03 | 25.43 | 30.6 | 15.7 | 18.17 | 19.95 | 22.05 | 26.45 | ||

| Cases/person-years | 106/18,038 | 101/21,223 | 103/21,882 | 110/21,647 | 127/17,976 | 112/17,628 | 82/21,216 | 130/22,417 | 123/22,372 | 130/17,736 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 0.73 (0.56–0.97) | 0.66 (0.50–0.87) | 0.69 (0.53–0.91) | 1.00 (0.77–1.29) | 0.505 | 1 (ref) | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | 0.78 (0.61–1.01) | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) | 1.03 (0.80–1.33) | 0.150 |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) | 0.65 (0.49–0.85) | 0.67 (0.51–0.88) | 0.94 (0.73–1.23) | 0.793 | 1 (ref) | 0.55 (0.42–0.74) | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | 0.69 (0.53–0.90) | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) | 0.198 |

| Model 3 | 1 (ref) | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) | 0.61 (0.46–0.82) | 0.60 (0.44–0.80) | 0.81 (0.60–1.11) | 0.513 | 1 (ref) | 0.54 (0.41–0.72) | 0.68 (0.52–0.89) | 0.57 (0.43–0.76) | 0.70 (0.52–0.96) | 0.203 |

Data are HR (95% CI) calculated by using Cox proportional hazards analyses. Model 1: adjusted for age, BMI, dietary intake of TE. Model 2: model 1 + residence area, highest education level, household income level, PAL, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and history of hypertension at baseline. Model 3: model 2 + dietary intake of carbohydrates, protein, ratio of MUFA-to-SFA intake, ratio of PUFA-to-SFA intake, cholesterol, magnesium, cereal fiber, vegetables, and fruits. Mutual adjustment was performed for dietary heme iron and nonheme iron. Tests for linear trend for HRs were conducted using the median value for each quintile of intake as a continuous variable. ref, reference.

Intakes were estimated as energy-adjusted cumulative average intake from baseline and follow-up periods.

In the analysis of effect modification (Supplementary Table 1), we did not observe significant effect modifications in stratified analyses except that among men, the negative association between nonheme iron and diabetes risk might have been stronger among former or current smokers than nonsmokers (P-interaction = 0.030). In fact, the HR for the highest versus lowest quintile of nonheme iron intake was 1.37 (95% CI 0.79–2.38) among nonsmokers and 0.70 (0.48–1.03) among former or current male smokers.

RCS analysis showed no association between heme iron intake and diabetes risk in either men (P-overall association = 0.358) (Fig. 1A) or women (P-overall association = 0.155) (Fig. 1B). However, there was a significant nonlinear association between nonheme iron intake and diabetes risk in both men (P-nonlinearity = 0.0015) (Fig. 1C) and women (P-nonlinearity <0.0001) (Fig. 1D). A similar association occurred between total iron intake and diabetes risk in both men (P-nonlinearity = 0.003) (Fig. 1E) and women (P-nonlinearity = 0.0001) (Fig. 1F). Among men, the dose-response relationship between nonheme and total iron intake and diabetes risk followed a reverse J shape, suggesting that when intake was relatively low, there was a negative correlation between intake and risk. Meanwhile, when nonheme iron intake exceeded 41 mg/day or total iron intake exceeded 46 mg/day, the HR increased significantly.

Figure 1.

Multivariable-adjusted HRs (black solid lines) and 95% CIs (dotted and dashed lines) for risk of diabetes according to dietary intake of heme (A and B), nonheme (C and D), and total (E and F) iron in men and women, respectively, in model 3. The median intakes were set as references (gray solid lines) (HR = 1.00). CL, confidence limit.

Among women, the first half of the nonheme-diabetes and total iron-diabetes association curves was similar to that among men. Although the latter half of the curves seemed to have an upward trend, the HRs of higher intakes were not significant relative to the median intake level according to the CIs, which seemed more like L-shaped associations.

Conclusions

This prospective analysis examined the association between dietary heme, nonheme, and total iron intake and risk of diabetes among a large sample of Chinese adults. Nonheme and total iron intake each showed a nonlinear association with diabetes risk. At relatively low levels, relatively higher intake of nonheme or total iron was associated with a lower risk of diabetes. However, when nonheme or total iron intake exceeded certain thresholds, relatively higher intake increased the risk of diabetes among men. In contrast, heme iron intake was not associated with diabetes risk.

Several previous studies have shown a positive association between heme iron intake and the risk of developing diabetes. In a meta-analysis (14) of five prospective studies (four conducted in a Western and one conducted in a Chinese population), investigators reported a pooled relative risk of 1.33 (95% CI 1.19–1.48; P < 0.001) in individuals with the highest level of heme iron intake compared with that of the lowest level. Subsequently, in a prospective study of Chinese descendants resident in Singapore (22), heme iron was reported to be positively associated with a higher risk of diabetes.

The current study found no significant association between heme iron intake and diabetes risk. However, our results are not unique. In a prospective cohort study of the Japanese population (20), dietary heme iron intake had no significant correlation with diabetes. The authors (20) hypothesized that this result might have been due to very low dietary intake of heme iron (mean intake 0.2 mg/day) among the Japanese, which was much lower than the European (1.8 mg/day) and Chinese (1.5 mg/day) equivalent. In the present analysis, the median intake of heme iron was 0.75 and 0.63 mg/day for men and women, respectively, which was much lower than reported in previous studies and likely not high enough to increase diabetes risk. Our result suggests that the association between heme iron and diabetes is dose dependent, and low intake may not pose a risk.

Because nonheme iron accounts for the majority of total iron consumption in Western and Eastern diets, the results were always consistent; therefore, we discuss both types of iron intake together. Previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the association between nonheme or total iron intake and risk of diabetes. Two prospective studies involving American women (18) and Chinese adults (22) found no associations between nonheme iron intake and diabetes risk. Moreover, two other prospective studies (16,17) based in the U.S. reported no association between total iron intake and diabetes risk. Conversely, in a prospective study involving Chinese men (19) and Japanese adults (20), total iron intake was positively associated with diabetes. Meanwhile, a study involving American women (21) showed an inverse association between nonheme iron intake and diabetes risk.

The decreased risk of diabetes associated with nonheme iron intake might be ascribed to other nutrients and unknown components of the main dietary sources of nonheme iron, such as grains, fruits, and vegetables (21). Nevertheless, in the present analysis, the results for nonheme iron remained a marginally significant negative correlation, even after adjusting for cereals fiber, vegetables, and fruits in women and in men when intakes were at relatively low levels, which suggests that dietary protective ingredients in the main dietary sources of nonheme iron could not explain this association. As we know, iron constitutes the metal nucleus of many cellular enzymes and is important for most cellular processes, including insulin secretion, β-cell metabolism (7), and antioxidant defense system function (37). Therefore, it is necessary to consume a sufficient amount of iron to maintain normal glucose metabolism, which might underlie the inverse association between diabetes risk and nonheme and total iron intake observed in this study.

In the current study, when nonheme or total iron intake exceeded certain thresholds, the risk no longer decreased and became nonsignificant in women, while higher intake was associated with increased risk of diabetes in men. This sex difference might be due to the differences in iron storage between men and women. Men tend to have higher serum ferritin concentrations than women (38), which is a finding also confirmed by our previous study (24), while women are more inclined not to retain excess iron because of menstruation. As such, men tend to accumulate more body iron than women when consuming their usual diets. Furthermore, a study reported that elevated concentration of ferritin is significantly related with a higher risk of diabetes among men but not among women (39), which also suggests this sex difference. A higher body iron accumulation rate in men might be associated with accelerated oxidative stress, which can damage the islet cells, affect insulin secretion, and exacerbate insulin resistance (3,6).

The strengths of this study include the prospective cohort design, long follow-up period, and repeated dietary assessments with the use of 3-day dietary records. Furthermore, we controlled for a number of dietary and nondietary covariates to reduce the confounding effects, although unmeasured and residual confounding remains possible.

Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. First, the ascertainment of diabetes was based on a questionnaire, which might have led to misclassification of the outcome. Second, this study did not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Third, the available Chinese Food Composition Tables contained no data on heme iron content, and the rough estimate (40%) might have resulted in a discrepancy between the estimate and the true value. Fourth, in our study, information on some important factors that may potentially be associated with diabetes risk, such as family history of diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, drug consumption, glycemic load, and trans–fatty acid intake were not available. Because of these limitations, we could not reach a sound conclusion. Finally, this population consumed a predominantly plant-based diet, with a relatively low intake of heme iron; thus, our results may not be generalizable to populations with high heme iron consumption. Further high-quality prospective studies that account for all likely confounders and take a more credible approach to identify outcome are needed to confirm the association between iron intake and diabetes risk in a population that consumes a plant-based diet.

In summary, the association between dietary intake of nonheme or total iron and diabetes risk was nonlinear, following an L shape among women and a reverse J shape among men. Appropriate nonheme or total iron intake was protective against diabetes in both sexes in this study, while excessive intake increased the risk among men.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. This research used data from CHNS. The authors thank the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Carolina Population Center (P2C-HD-050924, T32-HD-007168), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD-30880, DK-056350, R24-HD-050924, R01-HD-38700), and the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (D43-TW-009077, D43-TW-007709) for financial support for the CHNS data collection and analysis files from 1989 to 2015 and future surveys and the China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Ministry of Health, for support for CHNS 2009, Chinese National Human Genome Center at Shanghai since 2009, and Beijing Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control since 2011.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. J.H. performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. J.H. and K.L. designed and conducted the research. A.F., S.Y., and X.S. contributed to data collating, suggestion on statistical analysis, and review and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. K.L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at https://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc19-2202/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Deed G, Barlow J, Kawol D, Kilov G, Sharma A, Hwa LY. Diet and diabetes. Aust Fam Physician 2015;44:192–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salas-Salvadó J, Martinez-González MA, Bulló M, Ros E. The role of diet in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21(Suppl. 2):B32–B48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simcox JA, McClain DA. Iron and diabetes risk. Cell Metab 2013;17:329–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Drygalski A, Adamson JW. Iron metabolism in man. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2013;37:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papanikolaou G, Pantopoulos K. Iron metabolism and toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005;202:199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swaminathan S, Fonseca VA, Alam MG, Shah SV. The role of iron in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1926–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen JB, Moen IW, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Iron: the hard player in diabetes pathophysiology. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;210:717–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajpathak SN, Crandall JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Kabat GC, Rohan TE, Hu FB. The role of iron in type 2 diabetes in humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1790:671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CH, Kim HK, Bae SJ, Park JY, Lee KU. Association of elevated serum ferritin concentration with insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism in Korean men and women. Metabolism 2011;60:414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montonen J, Boeing H, Steffen A, et al. Body iron stores and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. Diabetologia 2012;55:2613–2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forouhi NG, Harding AH, Allison M, et al. Elevated serum ferritin levels predict new-onset type 2 diabetes: results from the EPIC-Norfolk prospective study. Diabetologia 2007;50:949–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajpathak SN, Wylie-Rosett J, Gunter MJ, et al.; Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group . Biomarkers of body iron stores and risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:472–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jehn ML, Guallar E, Clark JM, et al. A prospective study of plasma ferritin level and incident diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1047–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao W, Rong Y, Rong S, Liu L. Dietary iron intake, body iron stores, and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2012;10:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Z, Li S, Liu G, et al. Body iron stores and heme-iron intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e41641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang R, Ma J, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary iron intake and blood donations in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Liu S. A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women: the women’s health study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2108–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajpathak S, Ma J, Manson J, Willett WC, Hu FB. Iron intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1370–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Z, Zhou M, Yuan B, et al. Iron intake and body iron stores, anaemia and risk of hyperglycaemia among Chinese adults: the prospective Jiangsu Nutrition Study (JIN). Public Health Nutr 2010;13:1319–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eshak ES, Iso H, Maruyama K, Muraki I, Tamakoshi A. Associations between dietary intakes of iron, copper and zinc with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a large population-based prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 2018;37:667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DH, Folsom AR, Jacobs DR Jr. Dietary iron intake and Type 2 diabetes incidence in postmenopausal women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Diabetologia 2004;47:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talaei M, Wang YL, Yuan JM, Pan A, Koh WP. Meat, dietary heme iron, and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:824–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He J, Shen X, Fang A, et al. Association between predominantly plant-based diets and iron status in Chinese adults: a cross-sectional analysis. Br J Nutr 2016;116:1621–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurrell R, Egli I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1461S–1467S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF, Popkin BM. The China health and nutrition survey, 1989-2011. Obes Rev 2014;15(Suppl. 1):2–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhai F, Barry MP, Ma L, et al. The evaluation of the 24-hour individual dietary recall method in China. Wei Sheng Yen Chiu 1996;25:51–56 [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Health of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Food Composition Table. Beijing, China, People’s Medical Publishing House, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute for Nutrition and Food Hygiene of the Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine Food Composition Table. Beijing, China, People’s Medical Publishing House, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention China Food Composition Table. Beijing, China, Peking University Medical Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention China Food Composition Table 2004. 1st ed Beijing, China, Peking University Medical Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monsen ER, Hallberg L, Layrisse M, et al. Estimation of available dietary iron. Am J Clin Nutr 1978;31:134–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(Suppl.):1220S–1228S; discussion 1229S–1231S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsay RS, Hanson RL, Knowler WC. Tracking of body mass index from childhood to adolescence: a 6-y follow-up study in China. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:149–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010;33(Suppl. 1):S62–S69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med 2010;29:1037–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganesh S, Dharmalingam M, Marcus SR. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes with iron deficiency in Asian Indians. J Med Biochem 2012;31:115–120 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aregbesola A, Voutilainen S, Virtanen JK, Mursu J, Tuomainen TP. Gender difference in type 2 diabetes and the role of body iron stores. Ann Clin Biochem 2017;54:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han LL, Wang YX, Li J, et al. Gender differences in associations of serum ferritin and diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity in the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014;58:2189–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.