Abstract

The major challenges of most adult stem cell-based therapies are their weak therapeutic effects caused by the loss of multilineage differentiation capacity and homing potential. Recently, many researchers have attempted to identify novel stimulating factors that can fundamentally increase the differentiation capacity and homing potential of various types of adult stem cells. Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (WRS) is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed enzyme that catalyzes the first step of protein synthesis. In addition to this canonical function, we found for the first time that WRS is actively released from the site of injury in response to various damage signals both in vitro and in vivo and then acts as a potent nonenzymatic cytokine that promotes the self-renewal, migratory, and differentiation capacities of endometrial stem cells to facilitate the repair of damaged tissues. Furthermore, we also found that WRS, through its functional receptor cadherin-6 (CDH-6), activates major prosurvival signaling pathways, such as Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 signaling. Our current study provides novel and unique insights into approaches that can significantly enhance the therapeutic effects of human endometrial stem cells in various clinical applications.

Keywords: tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase, endometrial stem cells, therapeutic effects, Akt, ERK1/2 signaling

Graphical Abstract

Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (WRS) is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed enzyme that catalyzes the first step of protein synthesis. In addition to this canonical function, we identified for the first time that WRS is actively released from the site of injury in response to various damage signals both in vitro and in vivo and then acts as a potent nonenzymatic cytokine that facilitates the self-renewal, migratory, and differentiation capacities of endometrial stem cells to repair damaged tissues through the Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.

Introduction

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed enzymes that catalyze the first step of protein synthesis by covalently attaching amino acids to their corresponding tRNAs to form aminoacyl tRNAs during mRNA translation in the nucleus.1 Therefore, until relatively recently, these enzymes have been regarded as ubiquitously expressed housekeeping enzymes. Importantly, in addition to their known canonical activities, several studies have recently shown that some AARS family members may have noncanonical cytokine-like functions under specific physiological conditions, such as apoptosis,2 cell proliferation,3 glucose homeostasis,4 the inflammatory response,5 and vascularization.6 More recently, particular attention has been focused on the noncanonical functions of the family member tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (WRS) as a cytokine in the inflammatory response due to its rapid secretion to activate host defense pathways upon pathogen infection.7,8 These observations have raised the possibility that in addition to its previously reported canonical functions, WRS may have diverse biological activities as a secreted cytokine. Indeed, some previous studies have already shown that soluble WRS mediates antiangiogenic effects upon zinc binding,9 and WRS secreted by cord blood-derived stem cells in response to interferon-γ exerts a suppressive effect on excessive inflammation and disease progression in bowel disease.10 However, the noncanonical functions of WRS and their underlying molecular mechanisms in stem cell-mediated tissue regeneration remain unknown. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the cytokine functions of WRS that can regulate multiple beneficial functions of human endometrial stem cells.

The endometrium, which lines the cavity of the uterus, is one of the fastest growing tissues and undergoes extensive cyclic growth of up to approximately 7 mm within 1 week in every menstrual cycle.11 Similar to many other dynamic tissues, local clonogenic stem cells play a key role in the rapid regeneration and cyclic growth of the endometrial functional layer.12,13 Therefore, the continuous activation and mobilization of local endometrial stem cells that can give rise to individual uterine cell types are essential for the implantation of embryos and subsequent successful pregnancy.14 Importantly, Lucas et al.14 have shown that a deficiency of clonogenic endometrial stem cell populations limits the regenerative capacity of the endometrium and subsequently decreases pregnancy rates in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL). In this context, extensive research efforts have been devoted to investigating novel cytokines or molecules that can safely enhance the regenerative potential of endometrial stem cells and thus subsequently improve pregnancy rates.

In this context, we hypothesized that WRS is actively secreted in response to tissue damage and subsequently promotes the regeneration of injured tissues as a stem cell-boosting factor by enhancing various stem cell functions related to regeneration. Indeed, we found that WRS is actively released from the site of injury in response to various damage signals both in vitro and in vivo and then acts as a potent nonenzymatic cytokine that promotes the self-renewal, migratory, and differentiation capacities of endometrial stem cells to facilitate the repair of damaged tissues. Furthermore, we found that WRS, through its functional receptor cadherin-6 (CDH-6), activates major prosurvival signaling pathways, such as Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 signaling, which have been implicated in diverse cellular functions, including differentiation/pluripotency,15, 16, 17 recruitment,16,18 and self-renewal capacity,16,19 in various types of stem cells. Importantly, inhibition of these signaling pathways with selective inhibitors markedly attenuated the beneficial effects of WRS on endometrial stem cells. Another key finding from this study is that the in vivo therapeutic effects of transplanted stem cells were significantly increased upon prestimulation with exogenous WRS in mice subjected to endometrial ablation. Taken together, these results suggest that in addition to its well-known canonical functions (as an enzyme involved in catalyzing protein synthesis), WRS is actively secreted in response to tissue injury and subsequently enhances the therapeutic effects of stem cells in vitro and in vivo as a novel nonenzymatic cytokine.

Results

WRS Is Actively Secreted in Response to Multiple Damage Signals from Various Cell Types In Vitro and In Vivo

Human endometrial stem cells were freshly isolated from uterine tissue fragments as previously described20 (Figure S1A), and we then conducted expansion culture in vitro. Subsequently, the stem cell characteristics of the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using several positive and negative surface markers of stem cells, including CD34, CD44, CD45, CD73, CD105, and CD140b (Figure S1B). The ability of these stem cells to differentiate into multiple lineages, specifically adipocytes and osteoblasts, was analyzed by oil red O staining and alizarin red staining, respectively. Relative quantifications of lipid droplet formation and calcium mineral content were performed by measuring the absorbance at wavelengths of 500 and 570 nm, respectively (Figure S1C). A schematic representation of the main hypothesis about the noncanonical stem cell-stimulating functions of WRS is shown in Figure 1A. To confirm whether WRS is actively secreted from injured or stressed cells in response to various damage signals, multiple human cell types, including endometrial stem cells, fibroblasts, and vascular endothelial cells, were exposed to three different types of damage, namely, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and radiation. Interestingly, multiple types of human cells actively secreted WRS into the culture medium in response to various stress or damage signals in vitro (Figures 1B–1D). Next, systemic WRS levels in peripheral blood samples from mice with acid solution (trichloroacetic acid [TCA])-induced uterine damage were analyzed to further investigate whether tissue injury can induce WRS secretion into the circulating blood. Histological examination of endometrial lesions revealed that acidic TCA solutions markedly reduced endometrial thickness and increased apoptotic cells and vacuolar degeneration in mice (Figure 1E). Importantly, compared to the undamaged control, endometrial injury resulted in increased WRS secretion into the peripheral blood circulation in mice (Figure 1F). We also analyzed publicly available gene expression datasets deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) to study the correlations between enhanced WRS levels and various types of tissue damage. Consistently, WRS expression levels markedly decreased in skeletal muscle precursor cells from aged mice and during the differentiation of embryonic stem cells (Figure 1G). WRS expression also increased in culture medium supplemented with growth factors that stimulate pluripotency (Figure 1G). These results indicate that WRS is actively secreted from various cell types both in vitro and in vivo as an endogenous danger signal in response to multiple damage signals.

Figure 1.

WRS Is Actively Released by Various Cell Types in Response to Multiple Damage Signals In Vitro and In Vivo

(A) In addition to its canonical function, we hypothesized that WRS is actively released in response to multiple injury signals and functions as a stem cell-stimulating factor. (B) Endometrial stem cells, fibroblasts, or vascular endothelial cells were incubated in standard culture medium with or without aristolochic acid at various concentrations (10, 20, and 30 nM) to induce oxidative stress, after which the medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and the cells were cultured for 48 h. The proteins in the culture medium were harvested, precipitated with 10% TCA, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. (C) These cells were treated with or without paclitaxel at various concentrations (5, 10, and 20 μM) to induce DNA damage, after which the medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and the cells were cultured for 48 h. The proteins in the culture medium were harvested, precipitated with 10% TCA, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. (D) These cells were exposed to acute X-ray radiation at doses of 2, 4, and 6 Gy, after which the medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and the cells were cultured for 48 h. The proteins in the culture medium were harvested, precipitated with 10% TCA, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. To prove that the medium samples were not contaminated with cytosolic or nuclear content during the TCA precipitation procedure, the levels of β-actin in the culture medium were analyzed. (E) Treatment with the acidic solution (150 μL, administered directly into the uterine horn) caused significant uterine endometrial ablation on histological examination. Acute treatment with the acidic solution caused significant histological endometrial damage, with increased apoptosis and degenerative vacuoles. (F) Compared with the uninjured control, acidic solution-induced acute endometrial damage resulted in a significant increase in WRS secretion into the peripheral circulation. (G) The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was analyzed to further study the correlations between enhanced WRS levels and various types of tissue damage. β-Actin was used as the internal control. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

WRS Markedly Enhances Various Beneficial Functions of Human Endometrial Stem Cells In Vitro

Recently, Zhou et al.21 revealed that soluble WRS fragments can be produced by proteolytic cleavage of the full-length peptide or alternative RNA splicing and subsequently act as multifunctional cytokines (Figure 2A). We therefore determined whether exogenous WRS fragments can enhance several beneficial functions of endometrial stem cells as a stem cell-promoting cytokine. Indeed, the self-renewal potential of endometrial stem cells was markedly increased in the WRS treatment group compared with the nontreated control group (Figure 2B). Importantly, WRS treatment also significantly improved the migration capacity of endometrial stem cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C). To further confirm the promoting effect of WRS on the migration ability of endometrial stem cells, the expression profiles of MMP-2 and MMP-9, which play key roles in controlling cell invasion and migration by degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM), were analyzed using western blotting (Figure 2D). We further investigated the effects of WRS on the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 via gelatin zymography. Consistently, the activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were significantly increased in the WRS treatment group compared with the nontreated control group (Figure S2). Interestingly, WRS also markedly increased the self-renewal and migratory capacities of other types of human cells, including fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells (Figure S3). Additionally, WRS treatment significantly increased the multilineage differentiation potential of endometrial stem cells toward adipocytes and osteoblasts (Figure 2F). Consistently, the expression levels of pluripotency- or stemness-associated factors, such as NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2, were also strongly promoted by WRS treatment in endometrial stem cells (Figure 2G). We then analyzed the GEO database to further study the correlation between WRS levels and various physiological conditions. The expression levels of WRS were also significantly decreased in various degenerative conditions (aging or differentiation) and increased in proliferating cells compared to the corresponding controls (Figure 2H). These results suggest that WRS significantly enhances various beneficial functions of endometrial stem cells, such as migration capacity, pluripotency, self-renewal, and transdifferentiation potential, in vitro.

Figure 2.

WRS Significantly Increases Multiple Beneficial Functions of Human Endometrial Stem Cells In Vitro

(A) Soluble WRS fragments can be produced by proteolytic cleavage of the full-length peptide or alternative RNA splicing. (B) The enhancement of endometrial stem cell growth by WRS (100 nM, 1 μM) treatment for 72 h was determined by an MTT assay. (C) Endometrial stem cells were treated with WRS (100 nM, 1 μM) for 24 h, and then the effect of WRS on the migratory capacity was evaluated using a Transwell assay. WRS treatment markedly increased cell migration across the membrane. (D) The relative expression levels of key positive regulators of cell migration (MMP-2/9) were analyzed using western blotting. (E) Confluent stem cells were cultured in adipogenic or osteogenic medium with or without WRS treatment. The effects of WRS on adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation were determined by oil red O and alizarin red staining, respectively. Relative quantifications of calcium mineral content and lipid droplet formation were performed by measuring absorbance at 570 and 500 nm, respectively. (F) The real-time PCR results showed changes in the expression of the stem cell markers NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 after WRS treatment for 24 h. (G) The GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was analyzed to further study the correlations between WRS levels and various physiological conditions. DAPI staining was used to label the nuclei. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. β-Actin was used as the internal control. PPIA was used as a housekeeping gene for real-time PCR analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

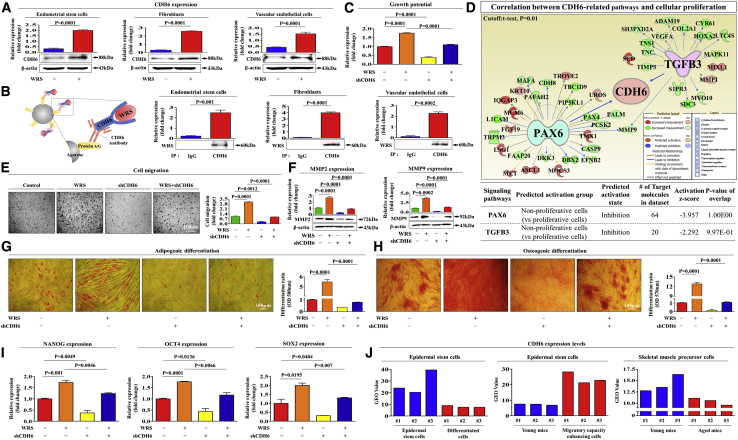

The Promoting Effects of WRS on Various Beneficial Functions Are Mediated through Its Functional Receptor CDH-6 in Human Endometrial Stem Cells In Vitro

Park et al.22 revealed that another AARS family member, glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GRS), is proteolytically fragmented and binds to K-cadherin (CDH-6) to inhibit tumorigenic activity. Additionally, WRS performs its antiangiogenic activity by binding to VE-cadherin.21 Consistently, our results showed that WRS treatment markedly increased CDH-6 levels in multiple cell types, including endometrial stem cells, fibroblasts, and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 3A). Next, immunoprecipitation with the CDH-6 antibody showed that WRS could directly bind to CDH-6 in all three cell types examined (Figure 3B). To further confirm whether CDH-6 can act as a functional receptor for WRS in endometrial stem cells, CDH-6 expression was effectively silenced by transfection with a specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting CDH-6 (Figures S4A–S4C). Consistently, WRS-mediated self-renewal capacity was significantly reduced by CDH-6 depletion (Figure 3C). To further investigate whether increased CDH-6-related signaling integrity is positively correlated with self-renewal capacity, we analyzed multiple gene expression profiles and their molecular networks using Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA). Negative regulators of CDH-6 (PAX [Z score = −3.957, p value = 1.00E−01] and transforming growth factor [TGF]-β3 [Z score = −2.292, p value = 9.97E−01]), which are involved in growth suppression, were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure 3D). WRS-induced migratory capacity (Figure 3E) and MMP-2/9 expression (Figure 3F) were also markedly reduced by CDH-6 depletion. In addition, we found that WRS-induced adipogenic (Figure 3G) and osteogenic (Figure 3H) differentiation was significantly attenuated by CDH-6 depletion. Consistently, the WRS-mediated expression of pluripotency-associated factors, such as NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2, was also significantly attenuated by CDH-6 depletion (Figure 3I). We analyzed the GEO database to further study the correlation between CDH-6 levels and various physiological conditions. Consistently, CDH-6 levels were significantly decreased in aged or differentiated cells compared to the corresponding control cells (Figure 3J). These results indicate that CDH-6 may serve as a functional receptor to mediate the stimulating effects of WRS on the multiple beneficial functions of endometrial stem cells.

Figure 3.

WRS Increases Multiple Beneficial Functions of Endometrial Stem Cells through Its Cognate Receptor CDH-6

(A) Endometrial stem cells, fibroblasts, and vascular endothelial cells were treated with or without WRS (1 μM) for 48 h, after which CDH-6 expression was confirmed by western blotting. (B) Endometrial stem cells, fibroblasts, and vascular endothelial cells were treated with or without WRS (1 μM) for 48 h, after which the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibodies against CDH-6. We detected WRS on the same membrane by western blotting. This result suggests that direct binding occurs between WRS and its receptor CDH-6. (C) Endometrial stem cells were treated with 1 μM WRS alone or were concomitantly transfected with shRNA targeting CDH-6, and subsequent changes in cell viability were analyzed by an MTT assay. (D) Differentially expressed genes in nonproliferative cells and proliferative cells (GEO: GSE62564) were analyzed using IPA software to predict the activation state of CDH-6-related signaling pathways. (E) The inhibitory effect of CDH-6 knockdown on WRS-induced changes in migration ability was also analyzed by a (F) Transwell assay and western blotting for MMP-2 and MMP-9. (G and H) The attenuating effects of CDH-6 depletion on the ability of WRS to promote (G) adipogenic and (H) osteogenic differentiation potential were analyzed by oil red O staining and alizarin red staining, respectively. (I) The expression of the pluripotency-associated factors NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 was evaluated by real-time PCR. (J) The GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was analyzed to further study the correlations between CDH-6 levels and various physiological conditions. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. β-Actin was used as the internal control. PPIA was used as a housekeeping gene for real-time PCR analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

WRS-Induced Beneficial Effects on Human Endometrial Stem Cells Are Mediated by the PI3K/Akt and/or ERK1/2 Signaling Pathways In Vitro

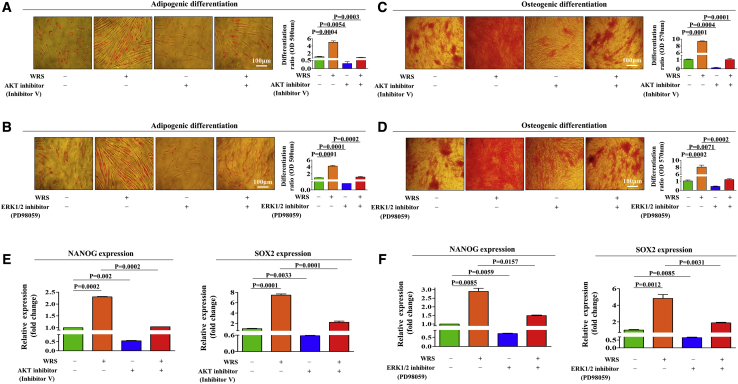

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the promoting effects of WRS on various endometrial stem cell functions, we analyzed the effects of WRS on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, which have been associated with pluripotency,23 self-renewal,24 and migration25 in multiple types of stem cells. We determined whether the PI3K/Akt and focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/ERK1/2 signaling pathways are activated by WRS treatment using western blotting (Figures 4A and 4B). We then investigated the effect of CDH-6 depletion on the ability of WRS to stimulate PI3K/Akt and FAK/ERK1/2 signaling. Importantly, WRS-induced PI3K/Akt and FAK/ERK1/2 signaling were clearly abolished by CDH-6 knockdown (Figures 4C and 4D). To further determine whether activation of Akt- or ERK1/2-related signaling pathway components is positively correlated with the self-renewal capacity of stem cells, we analyzed multiple gene expression profiles and their molecular networks using IPA. Positive regulators of Akt signaling, such as interleukin (IL)-15 (Z score = 3.438, p value = 2.45E−01), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Z score = 2.134, p value = 2.54E−02), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Z score = 1.965, p value = 2.71E−03), were enhanced in highly proliferative cells (Figure 4E). Negative regulators of ERK1/3 (MAPK1/3) signaling, such as TTP53 (Z score = −1.822, p value = 3.59E−01) and TGF-β1 (Z score = −3.253, p value = 1.00E−00), which are involved in growth suppression, were also inhibited in highly proliferative cells (Figure 4F). Consistently, the GEO database revealed that the expression levels of Akt (Figure 4G) or MAPK1/3 (Figures 4H–4I) were significantly decreased in various degenerative conditions, such as aging, growth suppression, or differentiation, compared to the corresponding control conditions. Next, to confirm whether the inhibition of these signaling activities attenuates the beneficial effects of WRS on endometrial stem cells, we analyzed the effects of the Akt inhibitor V or ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 on various endometrial stem cell functions, such as self-renewal, migratory, and multilineage differentiation capacities, in vitro with or without WRS treatment. Indeed, WRS-induced self-renewal ability (Figure 5A) and expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 (Figure 5B) were significantly abolished by inhibitor V or PD98059 pretreatment. Consistently, inhibitor V or PD98059 pretreatment attenuated WRS-induced migratory capacity (Figures 5C and 5D) and MMP-2/9 expression (Figures 5E and 5F) in endometrial stem cells. WRS-mediated adipogenic (Figures 6A and 6B) and osteogenic (Figures 6C and 6D) differentiation capacity and the expression levels of pluripotency-associated factors, such as NANOG and SOX2 (Figures 6E and 6F), were also significantly attenuated by inhibitor V or PD98059 pretreatment.

Figure 4.

WRS-Induced Stimulatory Effects on Endometrial Stem Cells Are Mediated by the FAK/ERK1/2 and/or PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

(A and B) Endometrial stem cells were stimulated for 10 min with or without WRS (1 μM) treatment. The endometrial stem cells were then lysed, and protein expression was analyzed by western blotting. The phosphorylation levels of PI3K/AKT (A) and FAK/ERK1/2 (B) signaling molecules were markedly enhanced in cells treated with WRS. (C and D) Endometrial stem cells were treated with 1 μM WRS alone or concomitantly transfected with shRNA targeting CDH-6, and subsequent changes in the phosphorylation levels of (C) PI3K and Akt and (D) FAK and ERK1/2 were analyzed by western blotting. (E and F) Differentially expressed genes in nonproliferative cells and proliferative cells (GEO: GSE66099, GSE28878, and GSE57083) were analyzed using IPA software to predict the activation states (either activated or inhibited) of the (E) Akt and (F) ERK1/2 signaling pathways. (G–I) The GEO database was analyzed to further study the correlations between the expression levels of (G) Akt, (H) MAPK1, or (I) MAPK3 and various degenerative conditions, such as aging, growth suppression, or differentiation. β-Actin was used as the internal control. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Suppression of the Akt or ERK1/2 Pathway with Specific Inhibitors Significantly Reduced the Ability of WRS to Promote Self-Renewal and Migratory Capacities

(A and B) Endometrial stem cells were pretreated with inhibitor V (10 μM) or PD98059 (20 μM) for 1 h prior to an additional 48-h treatment with 1 μM WRS, and subsequent changes in (A) cell viability and (B) Ki67 expression were analyzed by an MTT assay and western blotting, respectively. The attenuating effects of an Akt (C) or ERK1/2 (D) inhibitor on WRS-induced changes in stem cell migration were analyzed by a Transwell assay.The attenuating effects of an Akt (E) or ERK1/2 (F) inhibitor on WRS-induced changes in the expressions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were analyzed by western blotting. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. β-Actin was used as the internal control. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Suppression of the Akt or ERK1/2 Pathway with Specific Inhibitors Significantly Reduced the Ability of WRS to Promote Multilineage Differentiation Potential and Stemness

(A–D) Endometrial stem cells were pretreated with (A and C) inhibitor V (10 μM) or (B and D) PD98059 (20 μM) for 1 h prior to an additional 48-h treatment with 1 μM WRS, and subsequent changes in (A and B) adipogenic and (C and D) osteogenic differentiation potential were analyzed by oil red O and alizarin red staining, respectively. (E and F)The attenuating effects of (E) Akt or (F) ERK1/2 inhibitor on WRS-induced expression of the pluripotency-associated factors NANOG and SOX2 were analyzed by real-time PCR. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. PPIA was used as a housekeeping gene for real-time PCR analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

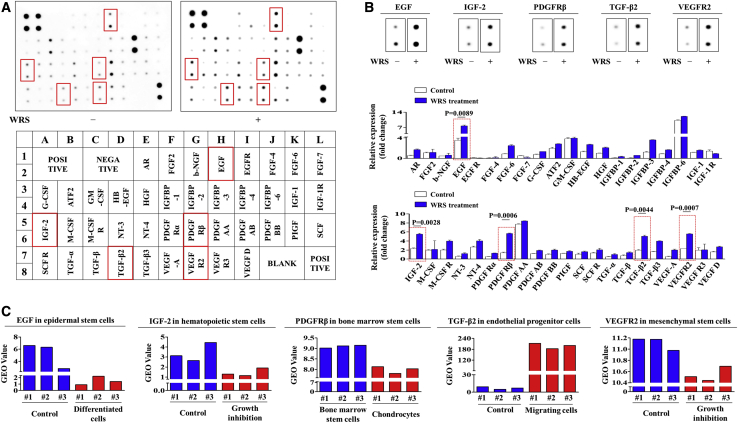

Profiling WRS-Induced Expression of Various Growth Factors and Their Correlations with Various Physiological Conditions

To determine whether the promoting effects of WRS on human endometrial stem cells can also be mediated by the secretion of various growth factors or cytokines, we conducted antibody arrays with or without WRS treatment. Interestingly, we detected changes in the expression of 40 proteins in WRS-treated endometrial stem cells. The expression levels of six growth factors, namely, EGF, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), IGF-2, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ), TGF-β2, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), were substantially increased by WRS treatment, whereas the expression of other growth factors was observed to have only minor changes from baseline levels (Figures 7A and 7B). These results suggest that these factors may be at least partly responsible for WRS-induced PI3K/Akt and/or FAK/ERK1/2 signaling and subsequent beneficial functions. We also analyzed publicly available gene expression datasets deposited in the GEO to further study the correlations between WRS-induced growth factors and various cellular conditions. Consistently, the GEO database revealed that the expression levels of the six most prominent factors also underwent corresponding changes in various degenerative conditions, such as aging, growth suppression, or differentiation, compared to the control conditions (Figure 7C). To further confirm whether these six most prominent factors that induced the investigated signaling pathways correlated with stem cell self-renewal capacity, we analyzed multiple gene expression profiles and their molecular networks using IPA software. Negative regulators of EGF, such as PTEN (Z score = −5.059, p value = 9.84E−01) and TGF-β1 (Z score = −3.103, p value = 9.39E−01), were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure S5A). Negative regulators of IGF-2, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (Z score = −5.567, p value = 7.39E−01) and E2F1 (Z score = −1.800, p value = 8.92E−01), were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure S5B). Negative regulators of PDGFRβ, such as TGM2 (Z score = −4.799, p value = 8.87E−01) and CIP2A (Z score = −2.624, p value = 4.24E−01), were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure S5C). Negative regulators of TGF-β2, such as TP63 (Z score = −2.754, p value = 1.00E−00) and EZH2 (Z score = −2.588, p value = 6.34E−01), were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure S5D). Finally, negative regulators of VEGFR-2, such as TP53 (Z score = −5.419, p value = 1.00E−00) and TGF-β1 (Z score = −2.694, p value = 1.00E−00), were inhibited in proliferative cells (Figure S5E). Both bioinformatics analyses consistently showed that the six most prominent factors are correlated with stem cell self-renewal capacity.

Figure 7.

WRS Induces the Secretion of Various Growth Factors or Cytokines, Which Are Related to the FAK/ERK1/2 and/or PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

(A and B) Human growth factor antibody array analysis was performed using WRS-treated or nontreated protein samples. The membrane was printed with antibodies against 40 growth factors, cytokines, and receptors. Six growth factors or related proteins (EGF, IGFBP3, IGF-2, PDGFRβ, TGF-β2, and VEGFR-2) were significantly increased in the WRS-treated protein samples (A). The changes of selected six growth factors were displayed and quantified (B). (C) The GEO database was also analyzed to further study the correlations between the six upregulated growth factors and the activation states of the Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. The data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

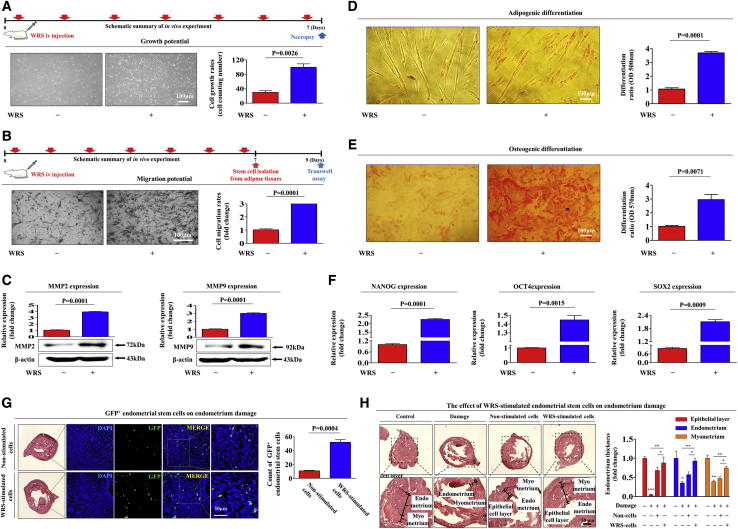

WRS Significantly Enhances the Therapeutic Effects of Endometrial Stem Cells in Mice Subjected to Endometrial Ablation by Increasing Their Capacity for Self-Renewal, Migration, and Differentiation

Our in vitro results suggest that WRS may act as a damage-inducible danger signal that can stimulate the therapeutic effects of endometrial stem cells by increasing their self-renewal, migration, and differentiation capabilities. Therefore, after intravenous WRS (3 mg/kg) injection for 7 consecutive days, endometrial stem cells were isolated from mouse uterine tissues. Consistent with the in vitro results, our in vivo data showed that WRS markedly enhanced the self-renewal potential of mouse endometrial stem cells (Figure 8A). In addition, the results from the Transwell assay (Figure 8B) and western blotting for the cell migration regulator MMP-2/-9 (Figure 8C) indicated that WRS had a significant stimulatory effect on the migration capacity of mouse endometrial stem cells in vivo. Moreover, WRS significantly enhanced the capacity of the cells to differentiate into adipocytes (Figure 8D) and osteoblasts in mice (Figure 8E). The mRNA levels of three pluripotency-associated transcription factors, namely, NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2, were also significantly enhanced by intravenous WRS administration in mice (Figure 8F). We further investigated whether WRS can increase not only the in vivo homing capacity of exogenously administered human endometrial stem cells to damaged sites but also their subsequent therapeutic effects in an endometrial ablation in vivo model. WRS-prestimulated human endometrial stem cells, which were labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Figure S6), were intravenously administered to immunodeficient mice, and then the in vivo homing capacity of the endometrial stem cells to the damaged sites of the endometrium was monitored using fluorescence microscopy. Importantly, compared with nonstimulated control cells, which were administered to uninjured normal mice, the WRS-prestimulated endometrial stem cells had significantly increased recruitment rates to local sites of endometrial damage in vivo (Figure 8G). Consistently, the relief of severe degenerative changes with loss of the endometrial functional layer induced by intravenous administration of WRS-prestimulated human endometrial stem cells was significantly greater than that induced by intravenous administration of unstimulated endometrial stem cells (Figure 8H). Taken together, these results indicate that WRS markedly increases the therapeutic effects of endometrial stem cells in vivo by stimulating their self-renewal, migration, and multilineage differentiation capacities.

Figure 8.

WRS Increases the Therapeutic Effects of Endometrial Stem Cells by Stimulating Self-Renewal, Migration, and Multilineage Differentiation Capacities In Vivo

(A) Mice were treated daily for 7 days with WRS (3 mg/kg, intravenously) or vehicle (PBS). Stem cells were isolated from mouse uterine tissue, and the changes in cell viability were evaluated by an MTT assay. (B and C) The effects of WRS on the migratory capacity of stem cells in vivo were analyzed by (B) a Transwell assay and (C) western blotting for MMP-2/9. (D and E) The changes in (D) adipogenic and (E) osteogenic differentiation capacities were evaluated by oil red O staining and alizarin red staining, respectively. (F) The real-time PCR results showed significant changes in the levels of various stem cell markers, such as NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2, after WRS treatment in vivo. (G) Direct administration of acidic 2% TCA solution (150 μL) into the uterine horn caused severe degenerative changes, with loss of the endometrial functional layer. WRS-prestimulated endometrial stem cells (1 × 106 cells) were labeled with GFP and then injected intravenously into the tail veins of 7-week-old immunodeficient NSG mice with acute TCA-induced endometrial ablation. The mice were sacrificed 7 days after the GFP-labeled endometrial stem cells were injected. Green fluorescence images of consecutive sections showed the presence of GFP-labeled cells. (H) Uterine endometrial tissue was collected and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. TCA-induced loss of the endometrial functional layer with degenerative changes was significantly more alleviated by the transplantation of WRS-prestimulated endometrial stem cells. Bar graphs represent the average of three independent experiments. β-Actin was used as the internal control. Mouse HPRT was used as a housekeeping gene for real-time PCR analysis. The data represent the mean ± SD from eight independent experiments.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the novel noncanonical functions of WRS as a stem cell-stimulating cytokine that can enhance the tissue regeneration capacity of endometrial stem cells by increasing several beneficial functions, such as self-renewal, migration, and multilineage differentiation capacities. Consistently, a previous study showed that two other AARS family proteins, histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HRS) and asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase (NRS), were released from damaged muscle cells and induced chemotactic migration of lymphocytes and dendritic cells as autoantigens by activating chemokine receptors.26 Similar cytokine activities of other AARS family members were also reported by Park et al.,22 who revealed that GRS can be released from macrophages in response to tumor cell-released Fas ligand and subsequently suppress tumor formation by inhibiting ERK1/2 signaling in vitro and in vivo. The exact molecular mechanisms by which WRS performs noncanonical cytokine activities have not yet been fully elucidated. Physical binding of some protein domains to other protein domains may alter the dynamic and structural features of proteins, which, in turn, may confer novel cytokine activities. Indeed, the attainment of novel functions in the AARS family of proteins may be associated with the acquisition of different domains.27 Zhou et al.21 also found that WRS fragments can be generated as a result of proteolytic cleavage or alternative splicing and then act as multifunctional cytokines with diverse effects on tumor cells by binding to the cell junction molecule VE-cadherin at its N-terminal domain. Indeed, our results demonstrated for the first time that WRS is actively secreted from multiple cell types as an endogenous injury signal in response to various damage or stress signals in vitro (Figures 1B–1D) and in vivo (Figure 1E).

Many early studies demonstrating the transdifferentiation potential of stem cells suggested that transplanted stem cells can exert dramatic therapeutic effects by replacing damaged cells at the site of injury. Despite many promising results, one of the major challenges of stem cell-based tissue regeneration is the low survival rate of the cells after transplantation.28 Indeed, it is well known that few transplanted stem cells survive, and as few as 1% of the cells may be detectable later at the site of injury.29 This limited engraftment of administered cells is a major problem but is common across different fields of stem cell therapy. Therefore, therapeutic stem cell administration may be a means to initiate and/or stimulate a repair process rather than a direct cell-to-cell replacement.30 Consistently, many recent studies suggest that the ability of transplanted stem cells to secrete multiple cytokines and growth factors to stimulate tissue repair and immune responses may be as important as their transdifferentiation capacity for improving tissue regeneration.31, 32, 33 Indeed, we also found that WRS significantly enhances the therapeutic effects of endometrial stem cells by promoting their abilities of self-renewal (Figure 2B), migration (Figures 2D and 2E), and multilineage differentiation (Figures 2Fand 2G) in vitro. Moreover, WRS-treated endometrial stem cells actively secreted many growth factors known to promote tissue regeneration, specifically EGF,34 IGFBP3,35 IGF-2, 36 PDGFRβ,37 TGF-β2,38 and VEGFR-239 (Figures 7A and 7B). These results suggest that WRS-mediated stimulatory effects on various endometrial stem cell functions during the regeneration of injured tissues may be at least partly due to the stimulation of diverse cellular functions, such as self-renewal, migratory, and differentiation capabilities, by these secreted proteins.

However, to improve pregnancy outcomes, increasing the endometrial thickness in patients with infertility with a thin endometrium is one of the most difficult challenges. Although several therapeutic strategies, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF),40 hormones,41 estrogen,42 and growth factors,43 have been tried to improve endometrial growth, these strategies did not sufficiently improve endometrial thickness, overall implantation rates, or subsequent clinical pregnancy outcomes. Many investigators have reported that endometrial stem cells reside in the basalis layers of the uterus and that these local stem/progenitor cells are responsible for endometrial regeneration and uterine function during every human menstrual cycle.12 Consistently, defective function of endometrial stem cells is strongly associated with a thin endometrium44 and recurrent implantation failure or pregnancy loss.14 Therefore, many research efforts have been devoted to regeneration of damaged endometrium using various types of stem cells in infertile animal models with uterine damage. Kilic et al.45 showed that exogenously administered adipose-derived stem cells effectively increase vascularization and endometrial regeneration in damaged endometrial animal models. Similarly, direct transplantation of bone marrow stem cells into the uterine cavity significantly improved endometrial thickness in an animal model with a thin endometrium.46 Furthermore, Zhang et al.47 also demonstrated that the administration of umbilical cord stem cells can restore endometrial thickness by promoting angiogenesis and downregulating several proinflammatory factors in animal models with a thin endometrium. Several clinical studies applied autologous bone marrow stem cells to regenerate the human endometrium in patients with severe endometrial deficiency.48, 49, 50 Despite several promising initial results, these non-original, tissue-derived, stem cell-based therapeutic approaches did not sufficiently increase implantation rates (IRs) and subsequent clinical pregnancy rates (CPRs) in many cases. These limited therapeutic effects can be explained by the following factors: (1) the administered cells were not cognate endometrial stem cells, which are the optimal cell type for promoting endometrial regeneration, and/or (2) the therapeutic potential of the administered stem cells was not sufficient to support proper endometrial regeneration. In this context, we have enhanced tissue regeneration of cognate endometrial stem cells by promoting various beneficial functions with exogenous WRS treatment. Indeed, we observed that WRS stimulation before administration markedly increased the in vivo homing capacity of endometrial stem cells to the injured site (Figure 8G), and uterine degenerative changes, with severe loss of the endometrial functional layer, were significantly restored by WRS-prestimulated endometrial stem cells in vivo (Figure 8H).

A specific cellular receptor through which WRS can exert its various beneficial functions in stem cells has not been reported previously. Interestingly, we found that WRS can directly bind to the adherent junctional molecule CDH-6 (also known as K-cadherin) and exert its beneficial function (Figures 3A and 3B). Importantly, we also revealed that the promoting effects of WRS on the beneficial functions of endometrial stem cells, such as proliferation (Figure 3C), migration (Figures 3E and 3F), and multilineage differentiation capacities (Figures 3G and 3H), were markedly attenuated by CDH-6 depletion using a well-established shRNA approach. These results indicate that CDH-6 may act as a functional receptor to mediate the beneficial effects of WRS on endometrial stem cells. Although it seems that WRS increases the therapeutic effects of endometrial stem cells in vivo, possible off-target effects must be completely excluded for the clinical use of stem cells or WRS-prestimulated stem cells. In particular, administered stem cells seem to be prone to off-target effects due to their weak or absent transdifferentiation capacity in vivo. We can therefore reduce or completely eliminate possible off-target effects by enhancing the pluripotency and differentiation potential of stem cells with various growth factors or novel stimulatory components. Unfortunately, there is no reliable way to predict and measure the rate of possible off-target effects of administered stem cells in vivo. Nevertheless, extensive studies need to be conducted to accurately predict and ultimately eliminate off-target effects of stem cell-based therapy. Taken together, the results of this study suggest that in addition to its well-known canonical functions, WRS is actively released in response to tissue injury and subsequently increases the therapeutic effects of surrounding stem cells by promoting various beneficial functions through the FAK/ERK1/2 and/or PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Our current study provides novel and unique insights into approaches that can significantly enhance the therapeutic effects of human adult stem cells in various clinical applications. Although it seems that WRS increases the therapeutic effects of endometrial stem cells in vivo, possible off-target effects should be studied prior to clinical use.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of Human Endometrial Stem Cells

Human endometrial stem cells were obtained from endometrial tissues of uterine fibroid patients with written informed consent from the patients and approval from the Gachon University Institutional Review Board (IRB no. GAIRB2018-134). The endometrial tissue was minced into small pieces, and then the small pieces were digested in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 250 U/mL type I collagenase for 5 h at 37°C in a rotating shaker. The digestion mixture was then filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer to separate stromal-like stem cells from epithelial gland fragments and undigested tissue. The isolated cells were then cultured in StemMax mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) basal medium (human) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells, termed HUVECs (ATCC PCS-100-010), were purchased from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection). Fibroblasts (CCD-986sk) were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB) and then cultured in DMEM.

Isolation and Culture of Mouse Uterine Tissue-Derived Stem Cells

The isolation of mouse uterine tissue-derived stem cells was approved and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (LCDI-2018-0138) of the Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute of Gachon University. Uterine tissue was minced into small pieces, and then the small pieces were digested in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 250 U/mL type I collagenase for 5 h at 37°C. The digestion mixture was then filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer. Isolated cells were then cultured in EBM-2 medium (Lonza) with EGM-2 supplements at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cell Proliferation Assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to determine the proliferation-stimulating capacity of truncated (Phe247∼Lys458) WRS (Cloud-Clone, RPB748Hu01), according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma, M5655). Cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with WRS or vehicle for 72 h. The viable cells were measured at 570 nm using a VersaMax microplate reader.

TCA Precipitation

Tissue culture dishes were seeded and incubated for each culture condition, and all of the supernatants were collected. They were then centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min (4°C) to remove the intact cells or cell debris from the supernatants. The supernatants were suspended in 10% TCA and kept at –4°C overnight. Then, the samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 5,000 × g and 4°C, and the supernatants were discarded. The resultant pellets were washed twice by centrifugation at 5,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min and resuspended in ice-cold PBS. The precipitated protein pellets were air-dried for 10–15 min and dissolved in 100–200 μL of ice-cold RBS for protein analysis.

In Vitro Cell Migration Assay

The stimulating effects of WRS on the migration potential of endometrial stem cells were evaluated by measuring the number of cells that migrated in response to WRS treatment divided by the number of spontaneously migrating cells. Cells were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well in 200 μL of culture medium in the upper chambers of permeable Transwell supports (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY, USA) to track the migration of cells. The Transwell chambers had 8.0-μm pores in 6.5-mm-diameter polycarbonate membranes and used a 24-well plate format. Noninvasive cells on the upper surface of each membrane were removed by scrubbing with laboratory paper. Migrated cells on the lower surface of each membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and stained with hematoxylin for 15 min. Later, the number of migrated cells was counted in three randomly selected fields of each well under a light microscope at ×50 magnification. The difference in each group is shown as the fold change.

Protein Isolation and Western Blot Analysis

Protein expression levels were determined by western blot analysis as previously described.51 Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), and 0.2 mM PMSF. The protein concentrations of the total cell lysates were measured by using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Samples containing equal amounts of protein were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 at room temperature (RT). Then, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against WRS (Cloud-Clone, PAB748Hu01), CDH-6 (Abcam, ab133632), β-actin (Abcam, ab189073), MMP-2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4022), MMP-9 (Cell Signaling Technology, 13667), total PI3K (Cell Signaling Technology, 4292), phosphorylated (phospho-)PI3K (Cell Signaling Technology, 4228), total Akt (Cell Signaling Technology, 4491), phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology, 4060), total-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9012), phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9101), total FAK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-558), or phospho-FAK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-11765) overnight at 4°C and then with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (BD Pharmingen, 554021) or goat anti-mouse IgG (BD Pharmingen, 554002) secondary antibodies for 60 min at RT. Antibody-bound proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents.

Immunoprecipitation Assay

Cells were lysed with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% NP-40, and 0.2 mM PMSF. Whole-cell lysates obtained by centrifugation were incubated with a 1/100 dilution of WRS antibody (Cloud-Clone, PAB748Hu01) or normal rabbit IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2027) and protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 20423) overnight at 4°C according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The immunocomplexes were then washed three times with lysis buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed using the ECL procedure according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Adipogenic Differentiation

Human- or mouse-derived endometrial stem cells were incubated in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 500 μM methylxanthine, 5 μg/mL insulin, and 10% FBS. Endometrial stem cells were grown for 3 weeks, with medium replacement twice per week. Lipid droplet formation was confirmed by oil red O staining. Relative quantification of lipid droplet formation was performed by measuring absorbance at 500 nm.

Osteogenic Differentiation

Human- or mouse-derived endometrial stem cells were incubated in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbate, and 10% FBS. Endometrial stem cells were grown for 3 weeks, with medium replacement twice per week. Differentiated cells were stained with alizarin red S to detect de novo formation of bone matrix. Alizarin red S in samples was quantified by measuring the optical density (OD) of the solution at 570 nm.

Flow Cytometry

FACS analysis and cell sorting were performed using FACSCalibur and FACSAria machines (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA, USA), respectively. FACS data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). Antibodies against the following proteins were used: allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated CD44 (BD Biosciences, 559942, dilution 1/40), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD133 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-080-081, dilution 1/40), CD34 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 30-081-002), CD44 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-095-180), CD45 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-080-201), CD73 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-095-182), CD105 (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-094-941), and CD140b (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-105-279). The FACS gates were established by staining with an isotype antibody or secondary antibody.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from endometrial stem cells was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using a Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN). The reaction was subjected to amplification cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 25 s. The relative mRNA expression of the selected genes was normalized to that of PPIA and quantified using the ΔΔCT method. The sequences of the PCR primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for qRT-PCR

| Gene | GenBank No. | Direction | Primer Sequence (5′→3’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human PPIA | NM_021130 | F | TGCCATCGCCAAGGAGTAG |

| R | TGCACAGACGGTCACTCAAA | ||

| Human OCT4 | NM_002701 | F | AGCCCTCATTTCACCAGGCC |

| R | TGGGACTCCTCCGGGTTTTG | ||

| Human NANOG | NM_024865 | F | TGGGATTTACAGGCGTGAGC |

| R | AAGCAAAGCCTCCCAATCCC | ||

| Human SOX2 | NM_003106 | F | AAATGGGAGGGGTGCAAAAGAGGAG |

| R | CAGCTGTCATTTGCTGTGGGTGATG | ||

| Human CDH6 | NM_004932 | F | ACCCAGTTCAAAGCAGCACT |

| R | GCAAACAGCACCACTGTCAC | ||

| Mouse HPRT | NM_013556 | F | GCCTAAGATGAGCGCAAGTTG |

| R | TACTAGGCAGATGGCCACAGG | ||

| Mouse OCT4 | NM_013633 | F | GCATTCAAACTGAGGCACCA |

| R | AGCTTCTTTCCCCATCCCA | ||

| Mouse NANOG | NM_028016 | F | GCCTTACGTACAGTTGCAGC |

| R | TCACCTGGTGGAGTCACAGA | ||

| Mouse SOX2 | NM_011443 | F | GAAGCGTGTACTTATCCTTCTTCAT |

| R | GAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCCGAGA |

Immunofluorescence Staining

Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for fluorescence staining. The samples were permeabilized with 0.4 M glycine and 0.3% Triton X-100, and nonspecific binding was blocked with 2% normal swine serum (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Staining was performed as described previously52 using a primary anti-phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, PHDH1) or anti-GFP (Invitrogen, V820-20) antibody. Samples were examined by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 Meta). Expression was calculated based on the green fluorescence area and density divided by the cell number, as determined from the number of DAPI-stained nuclei, in three randomly selected fields for each sample from a total of three independent experiments.

CDH-6 Knockdown

shRNA targeting CDH-6 (GenBank: NM_004932) and scrambled shRNA (shCTRL) were purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, South Korea). For efficient shRNA transfection, reverse transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 52887) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. We chose the CDH-6 shRNA that was most effective at the mRNA level from five shRNAs designed from the target sequence based on qRT-PCR analysis.

IPA

WRS-, CDH-6-, Akt-, ERK1/2-, EGF-, IGFBP3-, IGF-2-, PDGFRβ-, TGF-β2-, and VEGFR-2-related gene analyses were performed with IPA version 2.0 software (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA, USA). Differentially expressed genes (t test, p < 0.005) between nonproliferative cells and proliferative cells were subjected to WRS (GEO: GSE57083)-, CDH-6 (GEO: GSE62564)-, Akt (GEO: GSE66099)-, ERK1/2 (GEO: GSE28878 and GSE57083)-, EGF (GEO: GSE62564)-, IGFBP3 (GEO: GSE28874)-, IGF-2 (GEO: GSE21034)-, PDGFRβ (GEO: GSE63074)-, TGF-β2 (GEO: GSE28878)-, or VEGFR-2 (GEO: GSE68661)-related gene analysis. The significance of each factor was measured by Fisher’s exact test (p value), which was used to identify differentially expressed genes from the microarray data that overlapped with genes known to be regulated by a factor. The activation score (Z score) was used to show the status of predicted factors by comparing the observed differential regulation of genes (“up” or “down”) in the microarray data relative to the literature-derived regulation direction, which can be either activating or inhibiting.

R2 Database Analysis

We used the R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi/) to analyze the expression levels of WRS-, CDH-6-, Akt-, ERK1/2-, EGF-, IGFBP3-, IGF-2-, PDGFRβ-, TGF-β2-, or VEGFR-2-related genes between nonproliferative cells and proliferative cells. The values of these genes were log2 transformed and median centered. All of the graphics and statistical values were generated with GraphPad Prism 5.0, and p values were calculated with a two-tailed Student’s t test (p < 0.05).

Analysis of the GEO Database

GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) is a freely distributed database repository of high-throughput gene expression data generated by genome hybridization arrays, chip sequencing, and DNA microarrays.53,54 Researchers provide their experimental results in four categories: experimental designs, samples, platforms, and raw data. Clinical or experimental samples within each dataset are further organized based on various experimental subgroups, such as treatment, physiologic condition, and disease state. These categorized biological data are presented as “GEO profiles,” which include the dataset title, the gene annotation, a chart depicting the expression levels, and the rank for that gene across each sample.55 Gene expression data were selected from GEO datasets according to multiple parameters, such as tissues, cancers, diseases, genetic modifications, external stimuli, or development. The expression profiles of WRS, CDH-6, AKT, MAPK1/3, EGF, IGFBP3, IGF-2, PDGFRβ, TGF-β2, and VEGFR-2 in various degenerative conditions were analyzed according to previously established procedures.55

Growth Factor Antibody Array

The assay was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol (Abnova, AA0089). Briefly, WRS or vehicle-treated protein samples were incubated with antibody membranes overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with wash buffer, the membranes were incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-cytokine antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed three times and incubated with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. Chemiluminescence was used to detect the signals of the growth factors spotted on the nitrocellulose membrane.

Evaluation of the Effects of WRS on Normal and TCA-Induced Endometrial Ablation Animal Models

All of the animal experiments were approved and conducted in accordance with the IACUC (LCDI-2018-0138) of the Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute of Gachon University. The mice were randomly divided into control (vehicle) and WRS treatment groups. ICR mice were exposed to WRS (3 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) through intravenous injection for 10 consecutive days. The mice were anesthetized and exsanguinated by cardiac puncture, and then stem cells were isolated from uterine tissues. Additionally, 7-week-old immunodeficient NSG mice were subjected to treatment with 2% TCA (150 μL, administered directly into the uterine horn) to induce uterine endometrial ablation or with sterilized PBS vehicle as a control. WRS-stimulated or nonstimulated endometrial stem cells (1 × 106 cells) were labeled with GFP and injected intravenously into the tail veins of 7-week-old NSG mice with acute TCA-induced endometrial ablation. The mice were sacrificed 7 days after the GFP-labeled endometrial stem cells were injected. Mice from each group were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Uterine endometrial tissue was collected and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and evaluated using two-tailed Student’s t tests. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Author Contributions

S.-R.P., S.-R.K., J.-B.I., and S.L. conducted the experiments; I.-S.H. designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2018R1A2A3074613). This work was also supported by the Technology Innovation Program funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) (no. 20005221).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.023.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Ibba M., Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han J.M., Myung H., Kim S. Antitumor activity and pharmacokinetic properties of ARS-interacting multi-functional protein 1 (AIMP1/p43) Cancer Lett. 2010;287:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park S.G., Shin H., Shin Y.K., Lee Y., Choi E.C., Park B.J., Kim S. The novel cytokine p43 stimulates dermal fibroblast proliferation and wound repair. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:387–398. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62262-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S.G., Kang Y.S., Kim J.Y., Lee C.S., Ko Y.G., Lee W.J., Lee K.U., Yeom Y.I., Kim S. Hormonal activity of AIMP1/p43 for glucose homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14913–14918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko Y.G., Park H., Kim T., Lee J.W., Park S.G., Seol W., Kim J.E., Lee W.H., Kim S.H., Park J.E., Kim S. A cofactor of tRNA synthetase, p43, is secreted to up-regulate proinflammatory genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23028–23033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakasugi K., Slike B.M., Hood J., Otani A., Ewalt K.L., Friedlander M., Cheresh D.A., Schimmel P. A human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase as a regulator of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:173–177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn Y.H., Park S., Choi J.J., Park B.K., Rhee K.H., Kang E., Ahn S., Lee C.H., Lee J.S., Inn K.S. Secreted tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase as a primary defence system against infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;2:16191. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H.C., Lee E.S., Uddin M.B., Kim T.H., Kim J.H., Chathuranga K., Chathuranga W.A.G., Jin M., Kim S., Kim C.J., Lee J.S. Released tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase stimulates innate immune responses against viral infection. J. Virol. 2019;93:e01291-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01291-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu X., Zhou H., Zhou Q., Hong F., Vo M.N., Niu W., Wang Z., Xiong X., Nakamura K., Wakasugi K. An alternative conformation of human TrpRS suggests a role of zinc in activating non-enzymatic function. RNA Biol. 2018;15:649–658. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1377868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang I., Lee B.C., Lee J.Y., Kim J.J., Lee S.E., Shin N., Choi S.W., Kang K.S. Interferon-γ-mediated secretion of tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases has a role in protection of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells against experimental colitis. BMB Rep. 2019;52:318–323. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.5.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLennan C.E., Rydell A.H. Extent of endometrial shedding during normal menstruation. Obstet. Gynecol. 1965;26:605–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gargett C.E., Nguyen H.P., Ye L. Endometrial regeneration and endometrial stem/progenitor cells. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2012;13:235–251. doi: 10.1007/s11154-012-9221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gargett C.E., Ye L. Endometrial reconstruction from stem cells. Fertil. Steril. 2012;98:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas E.S., Dyer N.P., Murakami K., Lee Y.H., Chan Y.W., Grimaldi G., Muter J., Brighton P.J., Moore J.D., Patel G. Loss of endometrial plasticity in recurrent pregnancy loss. Stem Cells. 2016;34:346–356. doi: 10.1002/stem.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng B., Wang C., He L., Xu X., Qu J., Hu J., Zhang H. Neural differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells influences chemotactic responses to HGF. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013;228:149–162. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forte G., Minieri M., Cossa P., Antenucci D., Sala M., Gnocchi V., Fiaccavento R., Carotenuto F., De Vito P., Baldini P.M. Hepatocyte growth factor effects on mesenchymal stem cells: proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:23–33. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song B.Q., Chi Y., Li X., Du W.J., Han Z.B., Tian J.J., Li J.J., Chen F., Wu H.H., Han L.X. Inhibition of Notch signaling promotes the adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through autophagy activation and PTEN-PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015;36:1991–2002. doi: 10.1159/000430167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang J.M., Yuan J., Li Q., Wang J.N., Kong X., Zheng F., Zhang L., Chen L., Guo L.Y., Huang Y.H. Acetylcholine induces mesenchymal stem cell migration via Ca2+ /PKC/ERK1/2 signal pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012;113:2704–2713. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gharibi B., Ghuman M.S., Hughes F.J. Akt- and Erk-mediated regulation of proliferation and differentiation during PDGFRβ-induced MSC self-renewal. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012;16:2789–2801. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho A., Park S.R., Kim S.R., Nam S., Lim S., Park C.H., Lee H.Y., Hong I.S. An endogenous anti-aging factor, sonic hedgehog, suppresses endometrial stem cell aging through SERPINB2. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:1286–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Q., Kapoor M., Guo M., Belani R., Xu X., Kiosses W.B., Hanan M., Park C., Armour E., Do M.H. Orthogonal use of a human tRNA synthetase active site to achieve multifunctionality. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:57–61. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park M.C., Kang T., Jin D., Han J.M., Kim S.B., Park Y.J., Cho K., Park Y.W., Guo M., He W. Secreted human glycyl-tRNA synthetase implicated in defense against ERK-activated tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E640–E647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller P., Langenbach A., Kaminski A., Rychly J. Modulating the actin cytoskeleton affects mechanically induced signal transduction and differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong L., Hughes O., Yung S., Hyslop L., Stewart R., Wappler I., Peters H., Walter T., Stojkovic P., Evans J. The role of PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK and NFκβ signalling in the maintenance of human embryonic stem cell pluripotency and viability highlighted by transcriptional profiling and functional analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:1894–1913. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao F., Hu X., Xie X., Liu X., Wang J. Heat shock protein 90 stimulates rat mesenchymal stem cell migration via PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015;71:481–489. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard O.M., Dong H.F., Yang D., Raben N., Nagaraju K., Rosen A., Casciola-Rosen L., Härtlein M., Kron M., Yang D. Histidyl-tRNA synthetase and asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase, autoantigens in myositis, activate chemokine receptors on T lymphocytes and immature dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:781–791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo M., Schimmel P., Yang X.L. Functional expansion of human tRNA synthetases achieved by structural inventions. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Modo M., Rezaie P., Heuschling P., Patel S., Male D.K., Hodges H. Transplantation of neural stem cells in a rat model of stroke: assessment of short-term graft survival and acute host immunological response. Brain Res. 2002;958:70–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pittenger M.F., Discher D.E., Péault B.M., Phinney D.G., Hare J.M., Caplan A.I. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019;4:22. doi: 10.1038/s41536-019-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukomska B., Stanaszek L., Zuba-Surma E., Legosz P., Sarzynska S., Drela K. Challenges and controversies in human mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:9628536. doi: 10.1155/2019/9628536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamari M., Nishino Y., Yamamoto N., Ueda M. Acceleration of wound healing with stem cell-derived growth factors. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 2013;28:e369–e375. doi: 10.11607/jomi.te17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iso Y., Spees J.L., Serrano C., Bakondi B., Pochampally R., Song Y.H., Sobel B.E., Delafontaine P., Prockop D.J. Multipotent human stromal cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction in mice without long-term engraftment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;354:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S.R., Kim J.W., Jun H.S., Roh J.Y., Lee H.Y., Hong I.S. Stem cell secretome and its effect on cellular mechanisms relevant to wound healing. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi S.M., Lee K.M., Kim H.J., Park I.K., Kang H.J., Shin H.C., Baek D., Choi Y., Park K.H., Lee J.W. Effects of structurally stabilized EGF and bFGF on wound healing in type I and type II diabetic mice. Acta Biomater. 2018;66:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kielczewski J.L., Jarajapu Y.P., McFarland E.L., Cai J., Afzal A., Li Calzi S., Chang K.H., Lydic T., Shaw L.C., Busik J. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 mediates vascular repair by enhancing nitric oxide generation. Circ. Res. 2009;105:897–905. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J., Hu X., Chen J., Li X., Wang L., Wang B., Peng W., Yang C., Li Z., Chen Y. Pericentral hepatocytes produce insulin-like growth factor-2 to promote liver regeneration during selected injuries in mice. Hepatology. 2017;66:2002–2015. doi: 10.1002/hep.29340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen J., Ishii Y., Xu G., Dang T.C., Hamashima T., Matsushima T., Yamamoto S., Hattori Y., Takatsuru Y., Nabekura J., Sasahara M. PDGFR-β as a positive regulator of tissue repair in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:353–367. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oshimori N., Fuchs E. Paracrine TGF-β signaling counterbalances BMP-mediated repression in hair follicle stem cell activation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson K.E., Wilgus T.A. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the regulation of cutaneous wound repair. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3:647–661. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L., Xu W.H., Fu X.H., Huang Q.X., Guo X.Y., Zhang L., Li S.S., Zhu J., Shu J. Therapeutic role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for infertile women under in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) treatment: a meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;298:861–871. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui N., Li A.M., Luo Z.Y., Zhao Z.M., Xu Y.M., Zhang J., Yang A.M., Wang L.L., Hao G.M., Gao B.L. Effects of growth hormone on pregnancy rates of patients with thin endometrium. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2019;42:27–35. doi: 10.1007/s40618-018-0877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma S., Rani G., Bose G., Saha I., Bathwal S., Chakravarty B.N. Tamoxifen is better than low-dose clomiphene or gonadotropins in women with thin endometrium (<7 mm) after clomiphene in intrauterine insemination cycles: a prospective study. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2018;11:34–39. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_9_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi K.W., Mamillapalli R., Sahin C., Song J., Tal R., Taylor H.S. Bone marrow-derived cells or C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) treatment improve thin endometrium in a mouse model. Biol. Reprod. 2019;100:61–70. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deane J.A., Gualano R.C., Gargett C.E. Regenerating endometrium from stem/progenitor cells: is it abnormal in endometriosis, Asherman’s syndrome and infertility? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;25:193–200. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32836024e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kilic S., Yuksel B., Pinarli F., Albayrak A., Boztok B., Delibasi T. Effect of stem cell application on Asherman syndrome, an experimental rat model. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2014;31:975–982. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao J., Zhang Q., Wang Y., Li Y. Uterine infusion with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improves endometrium thickness in a rat model of thin endometrium. Reprod. Sci. 2015;22:181–188. doi: 10.1177/1933719114537715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L., Li Y., Guan C.Y., Tian S., Lv X.D., Li J.H., Ma X., Xia H.F. Therapeutic effect of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on injured rat endometrium during its chronic phase. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9:36. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagori C.B., Panchal S.Y., Patel H. Endometrial regeneration using autologous adult stem cells followed by conception by in vitro fertilization in a patient of severe Asherman’s syndrome. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2011;4:43–48. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.82360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh N., Mohanty S., Seth T., Shankar M., Bhaskaran S., Dharmendra S. Autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory Asherman’s syndrome: a novel cell based therapy. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2014;7:93–98. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.138864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santamaria X., Cabanillas S., Cervelló I., Arbona C., Raga F., Ferro J., Palmero J., Remohí J., Pellicer A., Simón C. Autologous cell therapy with CD133+ bone marrow-derived stem cells for refractory Asherman’s syndrome and endometrial atrophy: a pilot cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31:1087–1096. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi E.S., Jung J.Y., Lee J.S., Park J.H., Cho N.P., Cho S.D. Myeloid cell leukemia-1 is a key molecular target for mithramycin A-induced apoptosis in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells and a tumor xenograft animal model. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong H.J., Jang G.B., Lee H.Y., Park S.R., Kim J.Y., Nam J.S., Hong I.S. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling/Id2 cascade mediates the effects of hypoxia on the hierarchy of colorectal-cancer stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22966. doi: 10.1038/srep22966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barrett T., Suzek T.O., Troup D.B., Wilhite S.E., Ngau W.C., Ledoux P., Rudnev D., Lash A.E., Fujibuchi W., Edgar R. NCBI GEO: mining millions of expression profiles—database and tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D562–D566. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barrett T., Edgar R. Mining microarray data at NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;338:175–190. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-097-9:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.