Abstract

Objective

The association between the use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) inhibitors and the risk of mortality from COVID-19 is unclear. We aimed to estimate the association of RAAS inhibitors, including ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) with COVID-19 mortality risk in patients with hypertension.

Methods

PubMed (MEDLINE) SCOPUS, OVID, Cochrane Library databases and medrxiv.org were searched from 1 January 2020 to 1 September 2020. Studies reporting the association of RAAS inhibitors (ACEi or ARBs) and mortality in patients with hypertension, hospitalised for COVID-19 were extracted. Two reviewers independently extracted appropriate data of interest and assessed the risk of bias. All analyses were performed using random-effects models on log-transformed risk ratio (RR) estimates, and heterogeneity was quantified.

Results

Fourteen studies were included in the systematic review (n=73,073 patients with COVID-19; mean age 61 years; 53% male). Overall, the between-study heterogeneity was high (I2=80%, p<0.01). Patients with hypertension with prior use of RAAS inhibitors were 35% less likely to die from COVID-19 compared with patients with hypertension not taking RAAS inhibitors (pooled RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.94). The quality of evidence by Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations was graded as ‘moderate’ quality.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, with prior use of RAAS inhibitors was associated with lower risk mortality from COVID-19 in patients with hypertension. Our findings suggest a potential protective effect of RAAS-inhibitors in COVID-19 patients with hypertension.

PROSPERO registration number

The present study has been registered with PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD 42020187963).

Keywords: hypertension, antihypertensive drugs, meta-analysis

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the recent COVID-19 pandemic, interfaces with the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) through ACE2. Recent studies have questioned whether RAAS inhibitors are safe in patients with COVID-19. However, observational studies involving patients hospitalised with COVID-19 that report the association of RAAS-inhibitors and COVID-19 severity or mortality risk have often yielded conflicting findings.

What does this study add?

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that prior use of RAAS inhibitors is associated with a lower risk of mortality by 35% in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19 (risk ratio 0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.94).

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Patients taking RAAS-inhibitors to manage their hypertension should continue to do as per current treatment guidelines.

Introduction

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for the recent COVID-19 pandemic, interfaces with the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).1 2 The current hypotheses related to the influence ACE2 may have in facilitating virus severity and mortality have been inconclusive. The increased expression of ACE2 is thought to potentially catalyse infection with SARS-CoV-2, and therefore, increase the severity and risk of death.3On the contrary, it has been found that ACE2 may be protective against acute lung injury.4

ACE2 is an 805-amino-acid, homologous to the human ACE1, with 40% identity and 61% similarity.5 SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2, which serves as host cell entry receptor.1 Prior research has suggested that ACE-inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin-II blockers (ARBs), which are commonly used in patients with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and congested heart failure, may upregulate ACE2 expression and thus could increase the risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.6 Although ACE1 and ACE2 are two different enzymes with different active sites, there are reports that ACEi affect the expression of ACE2 in the heart and kidneys.7 Furthermore, ARBs alter ACE2 expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels.7 8 ACE2 is upregulated in both the renal vasculature tissue and cardiac tissue as a result of RAAS inhibitor exposure.9

Individuals with cardiovascular disease including hypertension are at increased risk of death from COVID-19,10 and yet majority depend on RAAS inhibitors for hypertension control. Despite these theoretical uncertainties regarding whether pharmacological regulation of ACE2 may influence the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, there is clear potential for harm related to the withdrawal of RAAS-inhibitors in patients in otherwise stable condition. Therefore, the potential influence of ACEi and ARB on the susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 infection requires urgent exploration for a clarification.

To date, observational studies involving patients hospitalised for COVID-19 that report the association of RAAS-inhibitors and COVID-19 severity or death have yielded conflicting findings. Some studies report potential harmful associations of exposure to ACEi or ARBs with an increased risk of severity in COVID-19,11 and others have failed to confirm such findings of potential harmful association.12 13 Of note, these studies have significant unaddressed sources of bias that limit conclusions drawn from them. In this this systematic review and meta-analysis, the authors aim to delineate the association of RAAS-inhibitors use and mortality in patients with COVID-19. We hypothesise that RAAS-inhibitors may increase mortality rates from the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

This study is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology in online supplemental table 1.14 15 The authors state that all supporting data are available within the article and its online-only data supplement. We explored PubMed (MEDLINE) SCOPUS, OVID, Cochrane Library databases and medrxiv.org, using search criteria provided in online supplemental material text 1. We included all studies published from 1 January 2020 to 1 September 2020 that reported on the use of RAAS inhibitors (ACEi or ARBs) in patients hospitalised with COVID-19. We identified papers reporting the mortality risk in patients with and without exposure to RAAS-inhibitors. The following Medical Subject Heading and keywords were used for the literature search of PubMed and other databases: “receptors, angiotensin” OR “angiotensin” OR “angiotensin receptors” OR “angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors” “renin angiotensin aldosterone system” OR “angiotensin receptor blocker” OR “ace inhibitor” OR “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor” AND “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19” OR “coronavirus”. Two reviewers (ESH and AES) initially screened the titles and abstracts of all papers for eligibility. We included articles that reported the rates of death in COVID-19 patients with and without taking RAAS inhibitors. No limitations were applied on study design, country of publication or language. We excluded case reports or case series with less than 10 patients, studies not conducted on humans, review papers, meta-analyses, literature reviews and commentaries. Excluded studies were documented with reasons for their exclusion.

openhrt-2020-001353supp001.pdf (192.1KB, pdf)

Data extraction

Two reviewers (ESH and AES) then screened full-text articles. If necessary, a third reviewer (PS) was consulted in order to reach a consensus. Data extracted included the author, year of publication, country of publication, sample size, the number of patients in the RAAS inhibitor group that did or did not die, and the risk ratio (RR) estimates and 95% CI of mortality in the RAAS-inhibitor group compared with the non-RAAS inhibitor group, the mean or median age with their corresponding SD or IQR, respectively, the proportion that is male, and the covariates adjusted for in each study. We gave priority to adjusted RR estimates if available.

Study quality assessment and confidence in cumulative evidence

Two reviewers (ESH and AES) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for the quality assessment of included studies.16 NOS rates observational studies based on three parameters: selection, comparability between the exposed and unexposed groups, and exposure/outcome assessment. This scale assigns a maximum of four stars for selection, two stars for comparability and three stars for exposure/outcome assessment. Studies with less than five stars were considered low quality, studies receiving five through seven stars were considered moderate quality, and those receiving more than seven stars were classified as high quality. We assessed the quality of evidence (QoE) using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework using four levels of QoE: very low, low, moderate and high.17 The following domains were used for the assessment: risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias.18 We reported the overall strength of evidence of the outcome of interest.

Data analysis

The primary outcome of interest was mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19. The exposure of interest was the prior use of RAAS-inhibitors. We used the reported RR, HR OR as the measures of the association between exposure to RAAS-inhibitors and the risk of mortality in COVID-19. For studies without measures of associations, we applied a generalised linear mixed model to calculate the RR using the number of events and the sample size of each study group.19 We invoked a random-effects model to pool study results for the association between exposure to RAAS-inhibitors and the risk of mortality using the metagen function from the R package meta.20 The DerSimonian and Laird method was used to estimate the pooled interstudy variance (heterogeneity).21 We constructed forest plots to display pooled estimates. We assessed interstudy heterogeneity using I2 statistics, expressed as % (low (25%), moderate (50%) and high (75%)) and Cochrane’s Q statistic (significance level <0.05).22 23

Due to the potential differences in the study population in terms of sociodemographic characteristics and the possible confounding in the studies with unadjusted estimates (studies we calculated RR), we expected to see large variations in the effect estimates. Therefore, subgroup analysis comparing studies with and without adjusted estimates was done. We hypothesised that the studies with unadjusted estimates will yield larger effect sizes compared with studies with adjusted estimates. Furthermore, outlier and influence diagnostics sensitivity analysis was undertaken to explore the effect of each individual study on the overall pooled estimate.24 Additional sensitivity analysis was conducted where we included additional studies whose sample size was not limited to the population with hypertension. We did not conduct meta-regression analysis to explore sources of variation due to lack of sufficient number of studies (less than 10 for the main analysis). For the similar reasons, we did not create funnel plots or conduct Egger’s test.25 All statistical analyses were performed with R software, V.3.4.3 (R, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

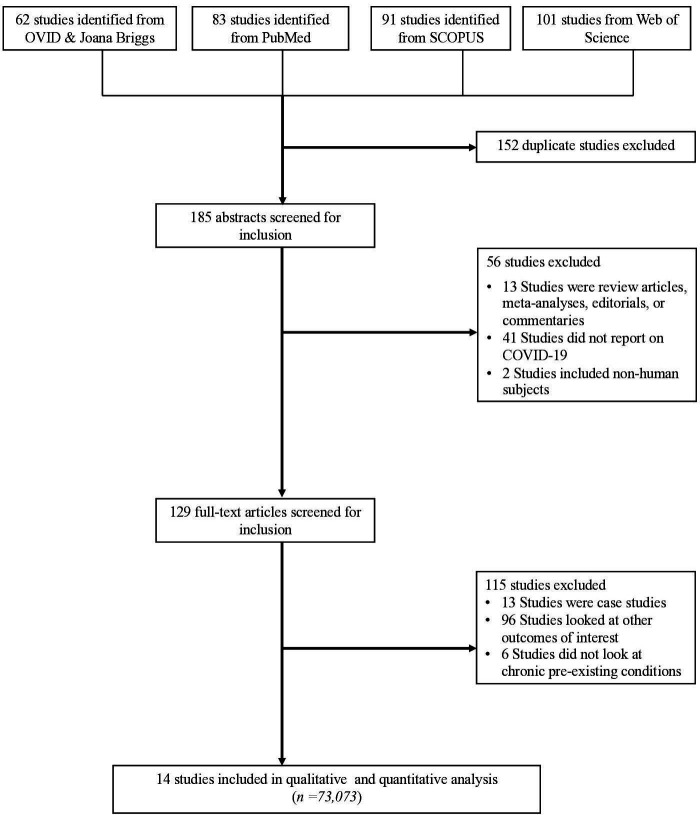

As shown in figure 1, we identified a total of 337 studies from the five databases. We excluded 152 studies because they were duplicates, leaving 185 studies. When screening titles and abstracts, we excluded 56 studies and another 115 based on full text, which left us with 73,073 patients with and COVID-19 from 14 studies for qualitative analysis and 72,981 patients from 12 studies for the quantitative analysis (table 1).11 12 26–37 The mean age was 61 years and 53% were male. The QoE by GRADE for the deaths was graded as ‘moderate’ quality (table 1). The median study quality score for studies was 8 out of 9 (range=7–9, table 1). Study-specific details and references are given in table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics for studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| Author | Country | Sample size (n) | Study type | Study period | Age, year | Male (%) | Covariates adjusted for | QoE | Quality score |

| Zhang12 | China | 3430 | Cohort | 31 Dec 2019–20 Feb 2020 | Median: 64 (IQR: 55–68) | 53 | Age, sex, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic renal disease, in-hospital medications (antiviral drug and lipid-lowering drug). | Moderate | 9 |

| Huang27 | China | 50 | Cohort | 7 Feb 2020–3 Mar 2020 | – | 54 | – | Low | 7 |

| Mancia28 | Italy | 37 031 | Case–control | 21 Feb 2020–11 Mar 2020 | Mean: 69 (SD: 13) | 63 | Age, sex, comorbidities and exposure to treatments. | Moderate | 8 |

| Li29 | China | 1178 | Cohort | 15 Jan 2020–15 Mar 2020 | Median: 56 (IQR: 38–67) | 46 | – | Medium | 8 |

| Mehta26 | United States | 18 472 | Cohort | 8 Mar 2020–12 Apr 2020 | Mean: 49 (SD: 21) | 40 | – | Moderate | 7 |

| Meng30 | China | 417 | Cohort | 11 Jan 2020–23 Feb 2020 | Median: 64.5 (IQR: 55.8–69.0) | 57 | – | Moderate | 8 |

| Zhang31 | China | 90 | Cohort | – | – | – | Age, sex, days from symptom onset to hospital admission, and exposure to treatments. | Low | 7 |

| Guo32 | China | 187 | Cohort | 23 Jan 2020–23 Feb 2020 | Mean: 59 (SD: 14.66) | 49 | – | Moderate | 7 |

| Bean33 | England | 1200 | Cohort | 1 Mar 2020–13 Apr 2020 | Mean: 68 (SD: 17) | 57 | Age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and ischaemic heart disease/heart failure. | Moderate | 9 |

| Zeng11 | China | 247 | Cohort | 5 Jan 2020–8 Mar 2020 | – | – | – | Moderate | 8 |

| Yang34 | China | 251 | Cohort | 5 Jan 2020–3 Mar 2020 | – | – | – | Moderate | 8 |

| Richardson35 | United States | 5700 | Case series | 1 Mar 2020–4 Apr 2020 | Median: 63 (IQR 52–75) | 60 | – | Moderate | 8 |

| Ip36 | United States | 3017 | Cohort | – | – | – | – | Moderate | 8 |

| Fosbøl37 | Denmark | 4480 | Cohort | 1 Feb 2020–4 May 2020 | Median: 54.7 (IQR 40.9–72.0) | 48 | Age, sex; education; income; history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, kidney disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, COPD, and malignancy; and use other antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, anticoagulants, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | Moderate | 9 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; QoE, quality of evidence.

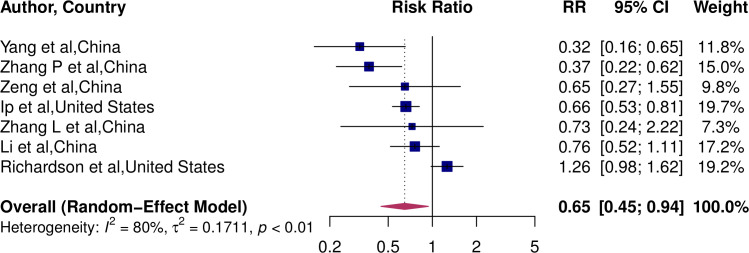

The association between taking RAAS inhibitors and COVID-19 mortality

Of the seven studies,11 12 31 34–36 included in the meta-analysis exploring the association between COVID-19 mortality and RAAS exposure in patients with hypertension, three reported a significantly lower risk with mortality (figure 2).12 34 36 No studies reported a significantly higher risk of mortality. The overall pooled estimates showed a 35% lower risk of mortality (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.94). Between-study heterogeneity was high (I2=80%, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Pooled RR for the association of RAAS-inhibitors and COVID-19 mortality. RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone.

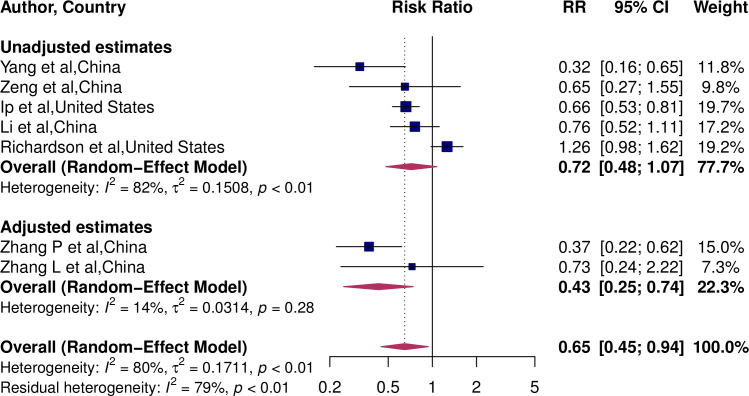

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analysis to explore whether there is a difference in pooled RR between studies that did and did not have adjusted RR estimates. The pooled RR of studies with adjusted estimate was 0.43 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.74), implying a 57% lower risk of death (figure 3). However, the pooled RR of studies with unadjusted estimates was 0.72 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.07), implying a lack of association with mortality risk (p for interaction=0.14).

Figure 3.

Pooled RR estimates of studies by covariate adjustment.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted influential sensitivity analysis in which we excluded and replaced one study at a time from the meta-analysis and calculating the pooled RR for the remaining studies. No substantial changes from pooled RR were observed when other studies were removed in turn. The pooled RR ranged from 0.57 to 0.72 (p<0.0001 for all) (online supplemental figure 1). Next, we calculated the pooled estimates by including all studies (main analysis from seven studies shown in figure 2 plus five studies whose sample size was not limited to the population with hypertension).26 28 32 33 37 The pooled RR including all studies was 0.77 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.95). However, pooled RR was lower in studies with population not limited to patients with hypertension 0.87 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.10) compared with studies consisting of only patients with hypertension (online supplemental figure 2).

Discussion

Principal findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies consisting of 73 073 patients with a global representation suggests that the treatment of hypertension with RAAS-inhibitors is associated with a lower risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19. This finding is important, for the association between RAAS-inhibitor exposure and mortality in COVID-19 patients has been inconclusive thus far. This topic has been heavily debated, and some studies even have interpolated a risk of taking RAAS-inhibitors using data from previous coronavirus outbreaks and preclinical studies.6

Comparison with other studies

This review provides up-to-date results for the contribution of RAAS-inhibitor use on the lower risk of mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19 by synthesising a large number of recently published studies. The study yielded a large number of individuals from countries representing Europe, North America and Asia. Our study findings are similar to results from a previously published systematic review, suggesting a lower mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19.38 Guo et al evaluated studies published until 13 May 2020, and included 3936 patients from nine studies.38 They found a 43% (95% CI 0.38% to 0.84%) lower risk in mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19. In the current meta-analysis, the risk of mortality was approximately 35% lower in patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, a large-scale retrospective study demonstrated that in-hospital use of ACEi/ARBs was associated with a lower risk of 28-day death among hospitalised patients with COVID-19 and coexisting hypertension (adjusted HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.66).12 These data suggested that patients with hypertension might obtain benefits from taking ACEi/ARBs compared with the non-ACEi/ARBs in the setting of COVID-19. In addition to what is reported in published studies, this systematic review and meta-analysis incorporated evidence from the most recent studies, and a large sample size.

Potential mechanisms

RAAS-inhibitors have been found to mitigate the risk of severe lung injury by reducing the activation of the RAAS through the inactivation of angiotensin II4 and the generation of angiotensin (1–9)5 and angiotensin (1–7).39 Angiotensin (1–7) binds to the G protein-coupled receptors Mas to mediate various physiological effects including vasorelaxation, cardioprotection, antioxidation and inhibition of angiotensin II-induced signalling. This is one hypothesised mechanism illustrating how the treatment of chronic conditions with RAAS-inhibitors may be beneficial in COVID-19 patients. Alternatively, it is hypothesised that the biological mechanisms of RAAS inhibitors may predispose COVID-19 patients to severe disease and even mortality. These hypotheses are based on the observation that SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2, which serves as host cell entry receptor. Animal models suggest that ACEis and ARBs increase membrane-bound ACE2 receptors, which then increases the availability of cells for SARS-CoV-2 to bind and cellular entry.7 This hypothesis has sparked a debate in populations, for many individuals taking RAAS inhibitors have grown concerned that their medications may be predisposing them to developing COVID-19, and later dying from it.40 Our meta-analysis supports the notion that RAAS inhibitor exposure does not increase COVID-19-related mortality but rather shows a possible beneficial effect. Future studies should continue to explore the association between COVID-19 and the use of RAAS-inhibitors to further ascertain these findings.

Implications for research and clinical practice

The majority of patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and congestive heart failure use RAAS blockers to manage their conditions. Our findings suggest that patients taking RAAS-inhibitors to manage their chronic diseases may continue to do as per current treatment guidelines and based on the clinical judgement of their healthcare providers

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of our study include possible selection bias in the published literature as a result of the strict COVID-19 testing algorithm employed in the early stages of the pandemic. This may have resulted in missed COVID-19 cases or deaths. Nevertheless, this is the largest quantitative synthesis of evidence on the association between RAAS-inhibitor exposure and COVID-19 mortality. The regions with the highest burden of COVID-19, including Asia, Europe and North America, were represented thus increasing the external validity of our findings. The sample size included in this study was also quite large, allowing us to thoroughly cover a large population.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, prior use of RAAS inhibitors was associated with a lower risk mortality from COVID-19 in patients with hypertension. Our findings suggest a potential protective effect of RAAS-inhibitors in COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Patients taking RAAS-inhibitors to manage their chronic diseases may continue to do as per current treatment guidelines and based on the clinical judgement of their healthcare providers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Melissa Butt for reviewing and proving helpful feedback.

Footnotes

Twitter: @annassentongo

AES, PS and ESH contributed equally.

Contributors: AES, PS, ESH and VMC conceived the study. AES, ESH and PS conducted the literature search. AES and PS completed data analysis. AES, DL, PD, VMC, AL, JSO, ESH and PS interpreted the data. AES, ESH and PS wrote the manuscript. All authors agreed to the manuscript in its final form.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This is a systematic review and meta-analysis and individual patient was not used. Therefore we did not need IRB or an ethics board approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

References

- 1.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020;181:271–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease: a viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016219. 10.1161/JAHA.120.016219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e21. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005;436:112–6. 10.1038/nature03712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, et al. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 2000;275:33238–43. 10.1074/jbc.M002615200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrario CM, Ahmad S, Groban L. Mechanisms by which angiotensin-receptor blockers increase ACE2 levels. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:378–1. 10.1038/s41569-020-0387-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005;111:2605–10. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Ye Y, Gong H, et al. The effects of different angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers on the regulation of the ACE-AngII-AT1 and ACE2-Ang(1-7)-Mas axes in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling in male mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016;97:180–90. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Gallagher PE, et al. Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade on renal angiotensin-(1-7) forming enzymes and receptors. Kidney Int 2005;68:2189–96. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, et al. Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0238215. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng Z, Sha T, Zhang Y, et al. Hypertension in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a single-center retrospective observational study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, et al. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res 2020;126:1671–81. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Abajo FJ, Rodríguez-Martín S, Lerma V, et al. Use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. The Lancet 2020;395:1705–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells G. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis, 2004. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 17.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siemieniuk R, Guyatt G. What is GRADE. British Medical Journal best practice. Available: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/ [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 19.Chang B-H, Hoaglin DC. Meta-analysis of odds ratios: current good practices. Med Care 2017;55:328. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G. Meta-analysis with R: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW-L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:112–25. 10.1002/jrsm.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS, et al. Association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiology 2020;5:1020 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Z, Cao J, Yao Y, et al. The effect of RAS blockers on the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1119. 10.21037/atm-2020-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2431–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa2006923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Wang X, Chen J, et al. Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiology 2020;5:825 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J, et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:757–60. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1746200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Sun Y, Zeng H-L, et al. Calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate is associated with reduced case fatality rate of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. medRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:811 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bean D, Kraljevic Z, Searle T, et al. Ace-Inhibitors and angiotensin-2 receptor blockers are not associated with severe SARS-COVID19 infection in a multi-site UK acute Hospital trust. medRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang G, Tan Z, Zhou L, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors usage is associated with improved inflammatory status and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients with hypertension. medRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ip A, Parikh K, Parrillo JE, et al. Hypertension and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. JAMA 2020;324:168–77. 10.1001/jama.2020.11301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X, Zhu Y, Hong Y. Decreased mortality of COVID-19 with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors therapy in patients with hypertension: a meta-analysis. Hypertension 2020;76:e13-e14. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res 2000;87:e1–9. 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz JH. Hypothesis: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of severe COVID-19. J Travel Med 2020;27 10.1093/jtm/taaa041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2020-001353supp001.pdf (192.1KB, pdf)