Abstract.

We report two cases of pediatric melioidosis. Both presented with erythema nodosum (EN) on the lower limbs. They both resided in an endemic region for this condition, and a presumptive diagnosis was made by high indirect hemagglutination assay titers of > 5,120 in both. Before this, there has been no recorded association between melioidosis and EN.

INTRODUCTION

Melioidosis is a disease caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Burkholderia pseudomallei. The organism is endemic to tropical regions worldwide, including northern Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.1–3 Most cases arise during the wet season, and transmission is predominantly thought to arise from inhalation, percutaneous inoculation, or ingestion.2,4 Current estimates suggest 165,000 cases of melioidosis and 89,000 resultant deaths worldwide per year.3,5 Pediatric cases represent 5–15% of the total number of cases.2,4 There are a broad spectrum of clinical presentations for melioidosis ranging from acute bacteremic pneumonia to disseminated visceral abscesses and localized infections.2,3 Known risk factors for melioidosis are diabetes mellitus, heavy alcohol use, chronic kidney disease, lung disease, and immunosuppression.3,4 Children who develop melioidosis typically do not have identifiable risk factors and are immunocompetent.2 Common presenting features of melioidosis in children vary depending on the geographic region. Pediatric melioidosis commonly manifests as localized cutaneous and soft tissue abscesses, with parotid abscesses being commonly reported from Thailand.2,3 In Australia, however, neurological presentations of melioidosis predominate.3

Recognizing atypical clinical presentations of melioidosis is vital toward reducing delay in diagnosis, providing optimal care, and reducing morbidity. In the following case series, we describe erythema nodosum (EN) as a novel clinical presentation of melioidosis. Written informed consent to use de-identified clinical information and photographs was obtained from both parents of the cases described.

Case 1.

A 2-year-old previously well boy presented with 13 days of fever, nasal congestion, and a red tender rash on the lower limbs. Symptoms developed after the patient was noted to have played in a rain-soaked backyard. Further history revealed the patient was born at full term from an uncomplicated pregnancy. The boy had no cough, dyspnea, photophobia, or neck stiffness. Physical examination revealed a well child appearing alert and active and afebrile with stable vitals. Lung fields were clear with equal bilateral air entry and a soft non-tender abdomen with absent organomegaly. Examination of the lower limbs revealed tender erythematous swellings on both shins consistent with EN. The lesions were hot and non-fluctuant, with irregular borders. Bilateral lymphadenopathy of the inguinal nodes was noted. There was no associated joint pain. No abnormalities were detected on chest X-ray. A full blood count revealed an elevated leukocyte count of 20 × 109/L with a neutrophilia of 12.57 × 109/L. Blood cultures were negative. Electrolytes and liver and kidney function tests were normal. The indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) serology for melioidosis was strongly positive with a titer of > 1:5,120.

In view of the highly positive melioidosis serology, treatment for melioidosis was initiated. Intravenous meropenem was administered for 1 week. This was followed by oral co-trimoxazole for a 3-month eradication course. Subsequent review indicated a fully recovered child with complete resolution of EN.

Case 2.

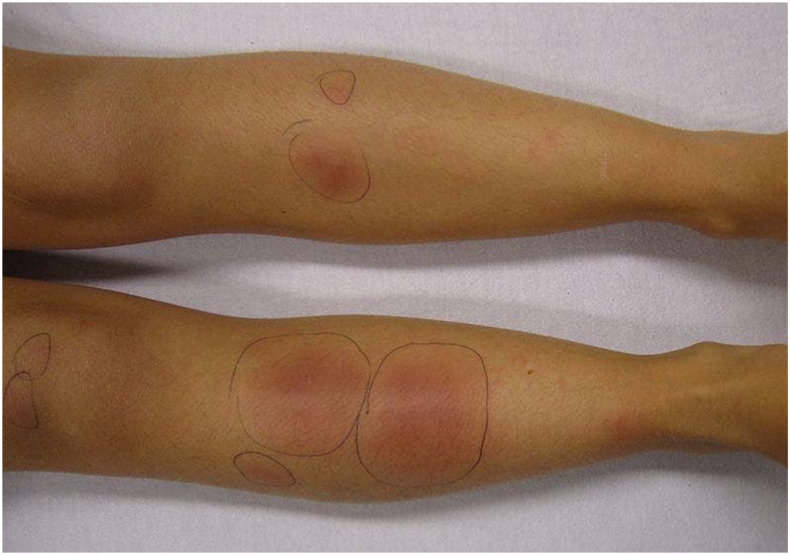

A 12-year-old girl presented to our hospital with erythematous tender skin lesions over her lower limbs. The lesions appeared 1 month following a major flood disaster. She denied direct skin contact with flood water. A skin biopsy taken was negative for bacterial/mycobacterial/fungal culture. Blood cultures were also negative. When reviewed, a clinical diagnosis of EN was made (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Erythema nodosum on both legs of Case 2. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

On further history, she had abdominal pain associated with diarrhea. There were no associated mouth ulcers, perianal disease, joint pain, dysphagia, or cough. She had no loss of appetite, weight loss, fever, or night sweats. She had been previously well. There was a family history of maternal Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

She had several investigations to exclude causes of EN including normal anti-streptolysin O and anti-DNase levels, nonreactive Mycoplasma serology, negative Cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus serology, negative Yersinia serology, and a negative QuantiFERON tuberculosis. She had a normal chest X-ray and angiotensin-converting enzyme. Antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti–double stranded DNA, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Over the course of several weeks, she continued to have recurrences of EN. Accompanying this, she had abdominal pain exacerbated by flares in EN. Her stools were loose stools with no mucous or blood.

Eventually, a high positive melioidosis serology was identified. Despite not isolating on culture, given the markedly high titer of > 1:5,120, she was admitted for treatment of melioidosis with IV ceftazidime.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were further investigated. computed tomography abdomen showed mild hepatomegaly and a thickened jejunal wall measuring 5.9 mm with no focal lesions or abscess. She had a normal fecal calprotectin, negative coeliac screen, negative stool culture viral PCR, and negative Clostridium toxin. She had an endoscopy and colonoscopy with normal biopsies.

Following 2 weeks of ceftazidime, she was commenced on oral co-trimoxazole maintenance therapy which was later changed to doxycycline because of drug-related neutropenia. She completed 3-month maintenance with complete resolution of EN and abdominal symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum is a well-recognized clinical entity with numerous clinical associations. Erythema nodosum has a peak incidence in women in the second to fourth decade of life but may occur at any age.6,7 In the pediatric population, both genders are equally affected; however, it is relatively uncommon in prepubertal children and rare before 2 years of age.6 Erythema nodosum is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, and a wide variety of conditions may trigger the development of EN such as infection, drug exposures, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease, pregnancy, vaccinations, and malignancy. It is idiopathic in approximately 50% of cases.6 Identified infectious causes of EN in the literature are highlighted in Table 1 with Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection being the most common cause in children.6,7

Table 1.

Infective causes of erythema nodosum

| Bacterial | Fungal | Viral | Protozoal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcal infection | Candida albicans | Epstein–Barr virus | Giardia lamblia |

| Tuberculosis | Trichophyton mentagrophytes | Hepatitis B virus | Entamoeba histolytica |

| Leprosy | Coccidioides immitis | Hepatitis C virus | Toxoplasma gondii |

| Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | Blastomyces dermatitidis | Parvovirus B19 | |

| Salmonella species | Histoplasma capsulatum | Human immunodeficiency virus | |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Sporothrix schenckii | Cytomegalovirus | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Parapoxvirus | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |||

| Chlamydia psittaci | |||

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae, | |||

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | |||

| Coxiella burnetii | |||

| Bartonella henselae | |||

| Helicobacter pylori | |||

| Gardnerella vaginalis | |||

| Francisella tularensis | |||

| Leptospira species | |||

| Brucella species |

Erythema nodosum classically presents with erythematous tender subcutaneous nodules on the pretibial area. Over time, the lesions tend to have a bruise-like appearance referred to as “erythema contusiformis,” and new crops of lesions can continue for 6 weeks.6 The underlying cause should be treated if possible,6 which may hasten resolution of the lesions as in the two cases presented. A diagnosis of EN usually can be made based on the clinical history and physical examination. A biopsy is useful for atypical cases. Regardless of the etiology, the characteristic histologic finding is a septal panniculitis without vasculitis.6,7

In the two cases reported here, we describe EN as a novel clinical presentation of melioidosis. This appears to be the first reported case series of EN presenting in cases of melioidosis in the literature. Although this report potentially identifies a new cause of EN, the single limitation is that the presumptive diagnosis was made by serology and not by tissue or blood culture. Culturing B. pseudomallei from relevant clinical material is the gold standard for diagnosing melioidosis.4 This is not always possible with bacteremia occurring in up to 73% of cases only.3 Hence, serology is occasionally useful in making the diagnosis. This is particularly so in cases where high IHA titers are noted.

Indirect hemagglutination assay is performed by using poorly defined antigens from strains of B. pseudomallei adsorbed to sheep erythrocytes. The sensitized erythrocytes are added to serial dilutions of heat-inactivated patient serum, and the IHA titer is the highest dilution of serum that causes distinct agglutination of erythrocytes.3 The IHA has a variable sensitivity (51–95%) and specificity (74–97%).3 High rates of background seropositivity in healthy individuals living in endemic regions contribute to the relatively low reliability of the IHA.8 However, the test is frequently performed with cutoff values assigned based on background seropositivity in the population. In a Thai study, 38% of healthy adults had seropositivity with an IHA titer ≥ 1:80.8 Hence, an IHA cutoff of less than 1:80 is deemed unlikely to indicate a true positive, and a titer of > 1:320 is likely to indicate infection with a specificity of 92%.3,9 In northern Australia where there is lower seroprevalence (2.5–8.7%),3 a negative serologic result has been previously defined as an IHA titer < 1:40 and a high positive result as between 1:160 and 1:1,280, with a very high positive result as > 1:1,280.10 Potential exposure to B. pseudomallei, given exposure post-rainfall, prompted clinical testing in both the cases described here. In these cases, the extremely high IHA titers of > 1:5,120 make it unlikely that this was due to background seropositivity.

Melioidosis is a disease with a wide spectrum of clinical presentation. Clinicians in endemic regions should have a low threshold to consider melioidosis in the setting of EN.

CONCLUSION

We describe two cases of atypical presentations of EN occurring in children where a serological diagnosis of melioidosis was made. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported association, and this requires further evaluation.

Acknowledgments:

We thank William Frischman and Andrew White, consultant pediatricians, for their involvement in the diagnosis and management of both patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Currie BJ, Jacups SP, Cheng AC, Fisher DA, Anstey NM, Huffam SE, Krause VL, 2004. Melioidosis epidemiology and risk factors from a prospective whole-population study in northern Australia. Trop Med Int Health 9: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLeod C, Morris PS, Bauert PA, Kilburn CJ, Ward LM, Baird RW, Currie BJ, 2015. Clinical presentation and medical management of melioidosis in children: a 24-year prospective study in the northern territory of Australia and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 60: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gassiep I, Armstrong M, Norton R, 2020. Human melioidosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 33: e00006-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiersinga WJ, Virk HS, Torres AG, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ, Dance DAB, Limmathurotsakul D, 2018. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4: 17107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limmathurotsakul D, et al. 2016. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol 1: 15008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung AKC, Leong KF, Lam JM, 2018. Erythema nodosum. World J Pediatr 14: 548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K, 2014. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J 20: 22376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaichana P, et al. 2018. Antibodies in melioidosis: the role of the indirect hemagglutination assay in evaluating patients and exposed populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg 99: 1378–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appassakij H, Silpapojakul KR, Wansit R, Pornpatkul M, 1990. Diagnostic value of the indirect hemagglutination test for melioidosis in an endemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg 42: 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng AC, O’Brien M, Freeman K, Lum G, Currie BJ, 2006. Indirect hemagglutination assay in patients with melioidosis in northern Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74: 330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]