Abstract

Here we highlight the role of epitranscriptomic systems in post-transcriptional regulation, with a specific focus on RNA modifying writers required for the incorporation of the 21st amino acid selenocysteine during translation, and the pathologies linked to epitranscriptomic and selenoprotein defects. Epitranscriptomic marks in the form of enzyme-catalyzed modifications to RNA have been shown to be important signals regulating translation, with defects linked to altered development, intellectual impairment, and cancer. Modifications to rRNA, mRNA and tRNA can affect their structure and function, while the levels of these dynamic tRNA-specific epitranscriptomic marks are stress-regulated to control translation. The tRNA for selenocysteine contains five distinct epitranscriptomic marks and the ALKBH8 writer for the wobble uridine (U) has been shown to be vital for the translation of the glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and thioredoxin reductase (TRXR) family of selenoproteins. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxifying selenocysteine containing proteins are a prime examples of how specialized translation can be regulated by specific tRNA modifications working in conjunction with distinct codon usage patterns, RNA binding proteins and specific 3’ untranslated region (UTR) signals. We highlight the important role of selenoproteins in detoxifying ROS and provide details on how epitranscriptomic marks and selenoproteins can play key roles in and maintaining mitochondrial function and preventing disease.

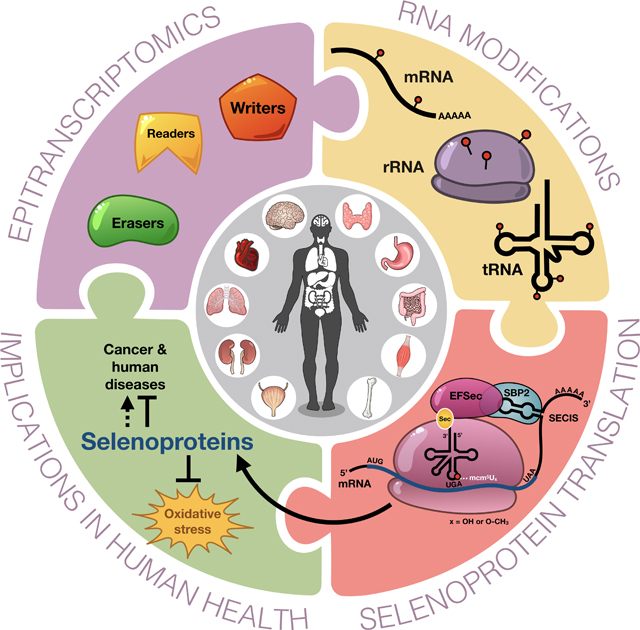

Graphical Abstract

1.1. Intro to RNA and Epitranscriptomics

Living systems use regulated gene expression for survival under stressful conditions. Gene expression involves transcription of the DNA message into RNA and translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) to proteins within the ribosome. During translation, transfer RNA (tRNA) carry amino acids to the ribosome where they are incorporated into a growing polypeptide via the direction of codon-anticodon interactions. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA), the predominant component of ribosomes, catalyzes peptide bond formation between two amino acids. While molecular mechanisms of stress responses at the epigenetic level function to modulate transcription and have been well studied and reviewed [1–3], epitranscriptomic regulation, using RNA modifications, to control the translation of stress response proteins has only recently been identified as an important determinant of protein expression[4–7]. In this review we highlight RNA modifications on different RNAs, detail tRNA modification systems and their role in translating selenoproteins. We also discuss recent epitranscriptomic findings on the control of stress induced protein expression by RNA modifications, and implications for mitochondrial function and selenoprotein based detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS), with defects linked to human disease.

RNA modifications are catalyzed by specific enzymes or RNA-protein complexes and may occur on the base and/or ribose sugar of the canonical adenosine (A), cytosine (C), guanosine (G) and uridine (U) nucleosides. The modifications can include simple changes such as deamination, methylation or acetylation, or hypermodifications such as queosine or N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) on tRNA [8]. The first mRNA modifications in the coding region were discovered in the 1970s [9] and were found to accelerate pre-mRNA processing and transport in HeLa cells [10]. In the 1980s, apolipoprotein B (apoB) mRNA was found to contain a tissue-specific cytidine-to-uridine base modification in the CAA codon at position 2153 which was not genomically encoded, resulting in a UAA stop codon and translational termination at this site [11,12]. The C to U change was present only in human and rabbit intestinal mRNA and resulted in a truncated version of the protein (termed APO-B48) while other tissues such as the liver did not have the edit and resulted in the full protein (APO-B100). It was the first example of a tissue-specific modification of a mRNA nucleotide resulting in two different proteins from the same primary transcript [12]. The enzyme APOBEC-1 (apolipoprotein B editing enzyme catalytic subunit 1) was found to catalyze the C to U editing of apoB, along with other factors [13–15], and APOBEC-1 was one of the early players which conceptually led to the modern field of epitranscriptomics.

Another early discovery of proteins that catalyze irreversible RNA modifications includes the ADAR (adenosine deaminase acting on RNA) family of enzymes, which deaminate adenosine on mRNA to inosine primarily in the 3’ UTR and intronic regions, suggesting a predominantly regulatory role of this edit (Fig. 1) [16]. While bioinformatics studies have identified more than 12,000 new A-to-I editing sites, only ~30 of those involve known protein-coding targets while the rest are located in noncoding regions such as introns and 5’ and 3’ UTRs [17,18]. The conversion of A to I is the most common type of RNA edit, and it serves critical functions in RNA processing, alternative splicing, protein function, development and immune response [19–22]. A related family of adenosine deaminases, the adenosine deaminases acting on tRNAs (ADATs), catalyze A to I at position 34 in 7–8 different cytosolic tRNAs (Fig. 2A) [25]. Inosine is also found in its methylated state (1-methylinosine) at position 37 and 57 [8]. The position 34 edit from A to I promotes pairing with codons ending in U, A and C [26].

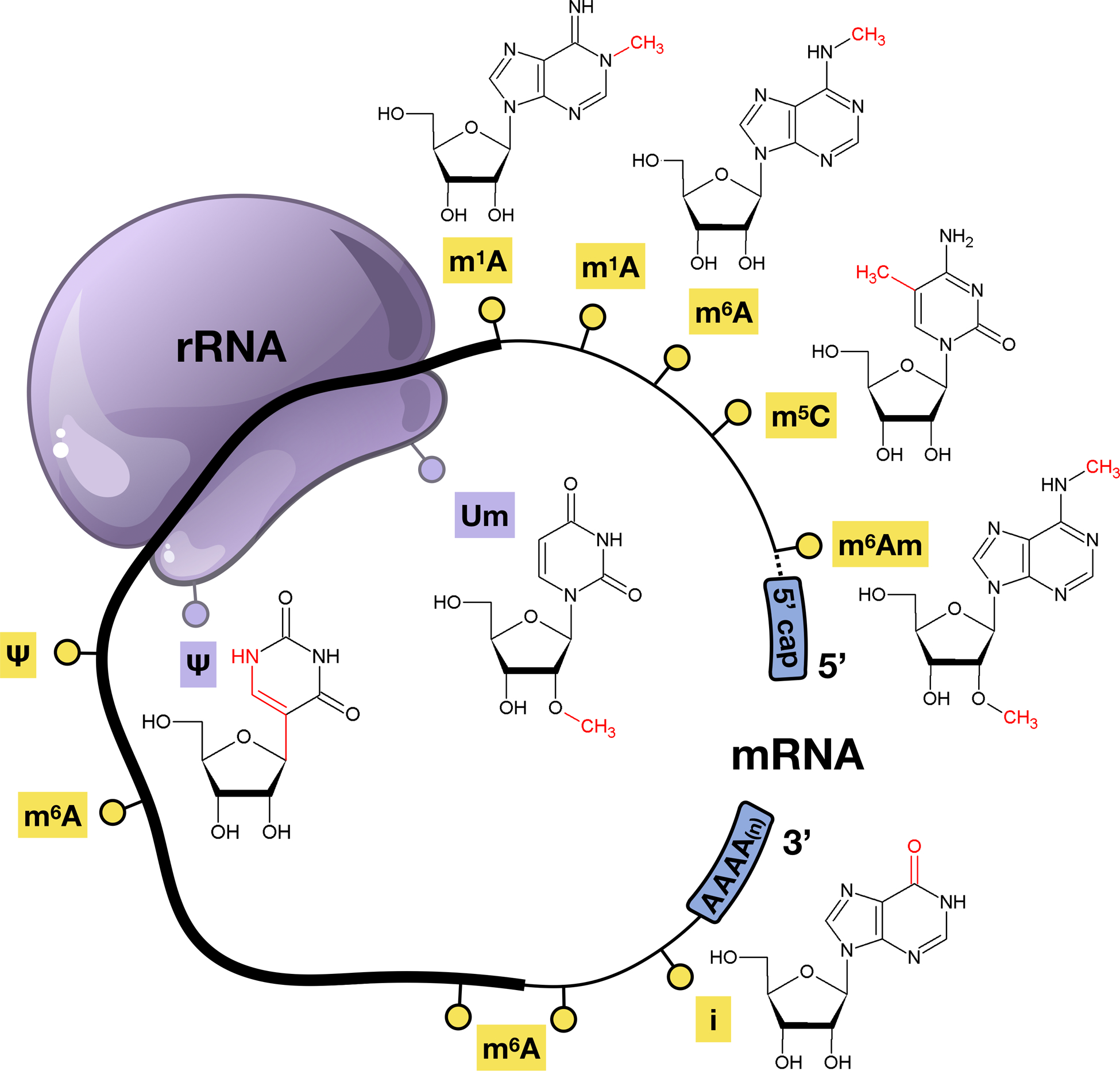

Figure 1. Common epitranscriptomic marks on mRNA and rRNA.

Six RNA modifications that are found on rRNA and mRNA, with the open reading frame (thick line) of mRNA and the 5’ and 3’ untranslated region (UTR)(thin line) highlighted to show where epitranscriptomic marks can be found.

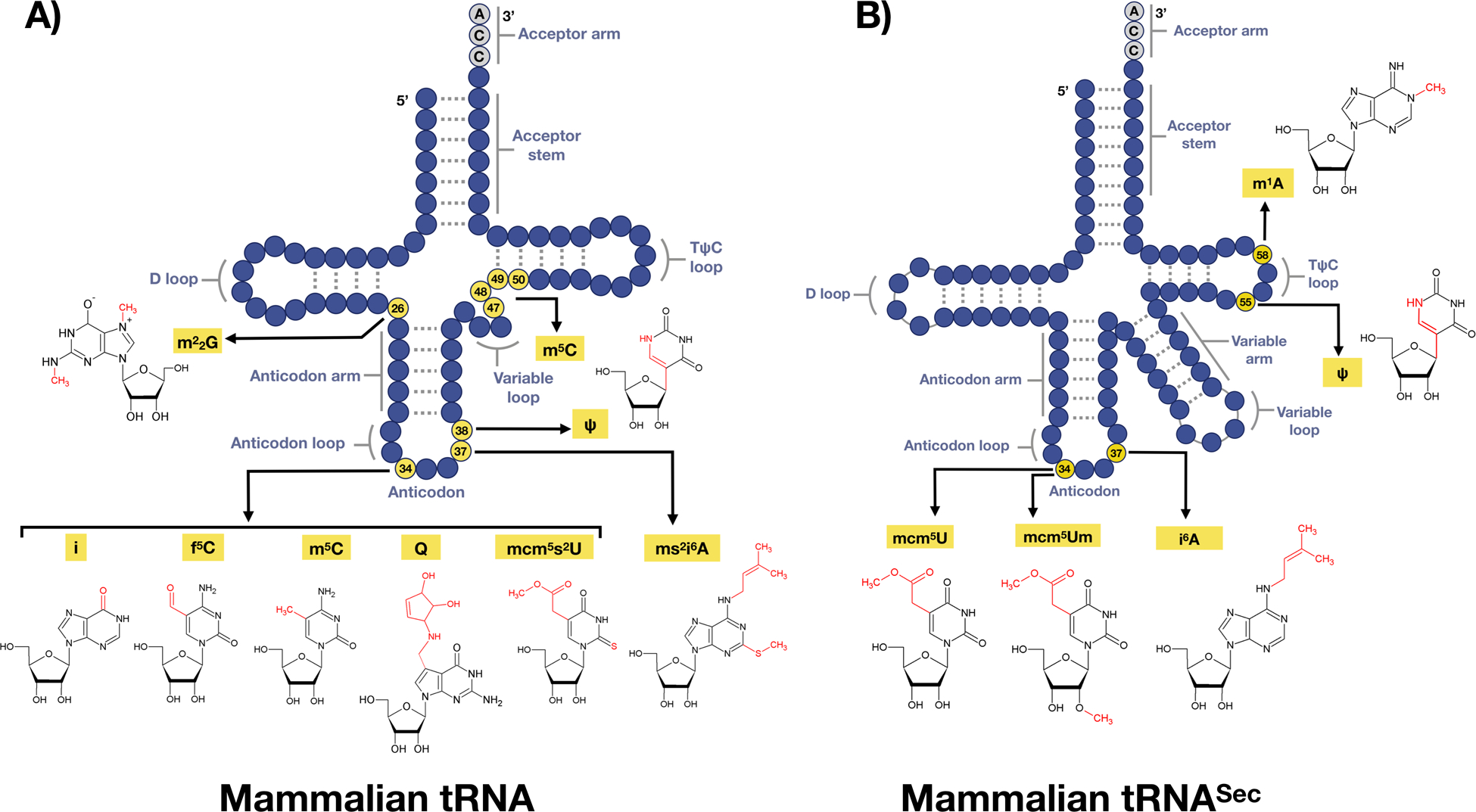

Figure 2. Some epitranscriptomic marks found on tRNA.

(A) There are on average 13 modifications on each tRNA species, with six epitranscriptomics marks highlighted. (B) tRNASec structure with 5 nucleoside modifications found on 4 positions.

Enzyme-catalyzed modifications can be found on almost every type of RNA and are able to fine-tune many aspects of gene expression. Over 140 post-transcriptional modifications across all types of RNA species have been identified to date (Fig. 1, Fig. 2), and these modifications directly influence RNA structure, function and have been linked to disease [8]. Various enzymes can add (“writers”), remove (“erasers”), and act upon (“readers”) RNA modifications, which can influence gene expression by altering charge, base-pairing potential, secondary structure, and protein-RNA interactions.

1.2. Epitranscriptomic marks on messenger RNA (mRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

Epitranscriptomic marks on mRNA include I, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), and pseudouridine (Ψ), with m6A and Ψ being the most abundant modifications based on mass spectrometry [27] (Fig. 1). m6A, m5C, and m1A have been identified within the mRNA coding sequence: [28–31]. Much of our understanding of readers, writers and erasers comes from studies on the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) posttranscriptional modification on mRNA (Fig. 1), [32–39]. The m6A epitranscriptomic mark can be located in multiple areas of the transcript, with common enrichment occurring near the stop codon in the open reading frame (ORF) as well as in the 3’ UTR [28,40]. The m6A writer complex consists of the Methyltransferase Like 3 (METTL3) and 14 (METTL14) proteins, which together form a METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer with additional accessory proteins such as Wilms tumor 1(WT1)-associated protein (WTAP), all together forming the N6-methyltransferase complex [41–43]. Dysregulation of m6A writer enzyme expression can promote tumor progression in glioblastoma stem cells [44], embryonic lethality [45], and disruption of neurogenesis [46].

The m6A modification was recently found to be dynamically regulated and control meiosis and stem cell differentiation and proliferation [47], heat shock response [48], DNA damage response [49], and tumorigenesis [50]. Dynamic regulation of epitranscriptomic marks is an emerging theme and global increases or decreases in specific RNA modifications can occur by changes in RNA level or regulated activity of writers and erasers. In mammals, m6A and its 2’-O-ribose methylated variant m6Am, have been shown to be dynamically regulated in the mouse brain in response to acute stress as well as in writer and eraser deficient mouse models [33]. In humans dysregulated m6A has been identified in major depressive disorder patients [51]. Notably, m6A was found to be reversible by the action of fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkylation repair homolog 5 (ALKBH5), both exhibiting robust m6A demethylase activity [52,53]. The addition and removal of m6A plays a dynamic role in a number of biological processes including mRNA transport, splicing, association with RNA binding proteins, UV-induced DNA damage response, oncogenesis and drug response [48,49,53,54]. ALKBH5, is expressed in many tissues, but most abundantly in the testes where its demethylase activity promotes mouse spermatogenesis and fertility [53]. ALKBH5 has also been shown to participate in cancer pathogenesis [55]. Patient-derived gliobastoma stem-like cells (GSCs) show high ALKBH5 expression, with its m6A demethylation of transcripts for the transcription factor FOXM1 driving tumorgenesis. Suppressing ALKBH5 also suppresses FOXM1 translation and reduces GSC proliferation [55]. Furthermore, ALKBH5 demethylase activity is important for antiviral innate immunity. DEAD-box helicase member 46 (DDX46) is a regulator of the immune response after viral infection, and recruits ALKBH5 to the nucleus. As the m6A modification is normally required for export of viral mRNA from the nucleus and for protein translation, ALKBH5 traps m6A modified antiviral transcripts in the nucleus by removing this mark [56].

The Ψ modification is the isomerization of the uridine base and was first characterized in both rRNA and tRNA [57–59]. This modification is also the most abundant in a wide range of cellular RNAs and highly conserved through evolution. However, the identification of this modification in mRNA was not discovered until recently with PseudoU-seq technology. PseudoU-seq technology is the high-throughput, single nucleotide resolution transcriptome mapping that allows the exploitation of N-cyclohexyl-N’–(2-morpholinoethyl)-carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulphonate (CMC) modification to determine the locations of Ψ [60]. The presence of an extra hydrogen bond donor on the non-Watson-Crick edge of pseudouridine affects structure to increase the thermodynamic stability of the Ψ-A base pairs by improving base pairing [61,62]. The Ψ modification is also known to affect RNA secondary structure and alter the stop codon read through [63,64]. In the case of mRNA, Ψ is catalyzed by the pseudouridine synthase (PUS) enzymes, specifically PUS1–4, PUS6, PUS7 and PUS9 [65].

Human ribosomes contain 80 ribosomal proteins and four rRNA chains, the 28S, 5S and 5.8S rRNAs in the 60S subunit, and 18S rRNA in the 40S subunit [66]. Among the human rRNA chemical modifications, approximately 95% are 2’-OH ribose methylations (2’-O-Me) and conversions of uridine (U) to pseudouridine (Ψ), (Fig. 2) while the remaining 5% of modifications are predicted to contain methylated bases and other modifications [67–69]. The exact biological effects of rRNA modifications are still under investigation, but the prevailing hypothesis is that they fine-tune translation, structure, and possibly ribosomal biogenesis [70]. There are 97 predicted Ψ in mammalian rRNA, including 28S, 18S, 5.8S and 5S rRNAs, and they predominately function in protein translation efficiency [71]. Pseudouridylation in rRNA is dependent on the Box H/ACA RNAs that are noncoding and fold into a hairpin-hinge-hairpin-tail secondary structure. There are few links between mammalian Ψ on rRNA and stress response and/or disease, with some links to cancer, mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia [72,73]. Mutations in PUS proteins and box H/ACA RNAPs are correlated with a range of diseases such as sideroblastic anemia, pituitary adenoma and mitochondrial myopathies [72,74].

1.3. Epitranscriptomic marks on transfer RNA (tRNA)

tRNAs are best known as the adaptor molecules of the translation machinery, in which they deliver the appropriate amino acids to the ribosomes according to the interaction of their anticodons with the codons of messenger RNAs (mRNAs). They are also critically involved in other cellular processes. Charged tRNAs act as amino acid donors not only to peptide chains during translation, but also to membrane lipids, peptidoglycan precursors, and the amino-terminus of proteins [75]. tRNAs also participate in stress responses and function as stress sensors [76]. For example, during nutrient deprivation eukaryotic cells respond by inhibition of protein synthesis, which can be mediated by tRNAs acting as signaling molecules. Starvation leads to limited availability of extracellular amino acids, which leads to accumulation of uncharged tRNAs in the cytosol. Uncharged tRNA can act as a signaling molecule by directly binding to the protein kinase GCN2 [77,78]. The now-activated GCN2 kinase phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2), which regulates translation in amino-acid starved cells and promotes synthesis of transcription factor GCN4, which activates amino acid synthesis genes. Interestingly, in budding yeast the GCN4-regulated transcripts exhibit a codon bias that can be linked to regulation by modified wobble uridines in tRNA [79].

tRNAs are extensively post-transcriptionally modified by epitranscriptomic writer enzymes, with these RNA modifications having structural and functional roles, as well as playing downstream roles in distinct biological processes. tRNA ribonucleoside modifications vary greatly in their type, location, and abundance. Ribonucleoside modifications are located throughout tRNA molecules and can affect tRNA stability, folding, transport, processing, localization and function [80]. On average, ~17% of the 80–90 ribonucleosides in tRNA are modified, ranging from relatively small structural changes, such as methylation to m5C or m1A, to highly intricate chemical alterations that give rise to hypermodified bases such as queuosine (Q) (Fig. 2). To highlight the importance of tRNA based epitranscriptomic marks, in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilius, depletion of m1A results in a thermosensitive phenotype implying a role of m1A in temperature adaptation. Bacterial, yeast, mouse and human cells deficient in tRNA modifications have been shown to be sensitive to DNA damaging agents and agents that promote increased ROS [5,81–86]. Global studies have demonstrated that the levels of epitranscriptomic marks in cytosolic tRNA are dynamically regulated during cellular stress [4–6]. For example, in response to oxidizing agents such as γ-radiation, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) or peroxynitrite (ONOO−), there is a significant increase in m5C, ncm5U, and i6A levels in yeast tRNA while the same modifications were unaffected in response to alkylating agents. In contrast, Um, mcm5U, mcm5s2U, m2G, and m1A modification levels increase in response to alkylating agents ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS), methylmethanesulfonate (MMS), isopropyl methanesulfonate (IMS) and N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-mitrosoguanidine (MNNG), and are conversely unaffected by treatment with oxidizing agents. The patterns of tRNA modifications are highly predictive and are responsive to distinct toxicants or stressors, and serve to reprogram translation to more effectively translate codon-biased transcripts into critical survival proteins in order to overcome the stress[4–6]. Stress-induced changes in tRNA have been observed in bacteria [7], yeast [4,87–90], mouse embryonic fibroblasts [91], human colorectal cancer cells [92] and melanoma cells [93].

The anticodon loops of nearly all tRNAs, including cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAs are almost always modified [8,94]. Modifications on position 34 and 37 are especially important and promote translational fidelity and optimized codon-anticodon interaction within the ribosome [95]. The U34 modifications 5-methoxycarbony-methyl-uridine (mcm5U) and 5-methoxycarbonyl-methyl-2-thiouridine (mcm5s2U) (Fig. 2), are catalyzed by elongator (ELP 1–6) enzymes, Alkylation repair homolog 8 (ALKBH8) methyltransferase, and the Ubiquitin-related modifier 1 (URM1) pathway [96]. The mcm5U modification can be found on tRNAs encoding lysine, arginine, glycine, glutamine, glutamic acid and selenocysteine[97–100], while the mcm5s2U is found on tRNAs for lysine, arginine glutamine and glutamic acid [99–101]. In budding yeast, the mcm5U and mcm5s2U modifications play key roles in preventing protein synthesis errors, which include amino acid misincorporation and −1 frameshifts, with writer deficiencies activating heat shock and unfolded protein response (UPR) pathways[102]. Wobble uridine modifications at position 34 (U34) are important for maintaining proteome integrity and loss of these modifications perturbs cellular signaling and causes proteotoxic stress [103,104]. Yeast studies have shown that tRNA modifications play important roles in reading frame maintenance such that tRNAs deficient in wobble U modifications enter the ribosome A-site with decreased efficiency [105,106]. Many genes encoding tRNA modification enzymes are critical for cell function during conditions of stress as well as general function, growth and development [107,108]. We have previously shown that Alkbh8-deficient MEFs have an impaired ability to catalyze mcm5Um modifications in response to H2O2 on tRNA for selenocysteine (tRNASec) and are sensitive to oxidizing agents [91]. The tRNA methyltransferase ALKBH8 has been directly linked to intellectual disability as a consequence of severe impairment in wobble uridine modifications [109]. Deficiencies in other tRNA-modifying enzymes are also linked to severe and complex human diseases and wide tissue vulnerability [107]. Kirino et al., 2004 linked mutations in mitochondrial methyltransferases on the tRNALeu(UUR) gene which caused mitochondrial myopathy, lactic acidosis, encephalopathy, and a specific group of mitochondrial encephalomyopathic diseases that cause stroke-like episodes (MELAS) [110]. A polyadenylation factor I subunit 1 (CLP1) is a multifunctional kinase that modifies tRNA, mRNA, and siRNA and is important for RNA maturation. As one example, a mutation in CLP1 destabilizes the tRNA endonuclease complex and results in impaired pre-tRNA cleavage as well as impaired ligation in the final step of tRNA maturation. This is a direct consequence of decreased CLP1-catalyzed phosphorylation required during tRNA maturation. The downstream result is cerebellar neurodegeneration due to the depletion of mature tRNAs and accumulation of unspliced pre-tRNAs [111]. CDK5 regulatory associated protein 1-like 1 (CDKAL 1) has been widely studied and linked to type 2 diabetes. CDKAL 1 is a mammalian methylthiotransferase that biosynthesizes 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbmoyladenosine (ms2t6A) in tRNALys(UUU) allowing accurate translation of AAA and AAG codons. Mice that were deficient in CDKAL 1, showed a decrease in insulin secretion, pancreatic islet hypertrophy and impaired blood glucose control. Cdkal1−/− mice were also hypersensitive to a high fat diet which induced ER stress. This study unveiled a suggested molecular pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in patients who carried Cdkal 1 risk alleles[112].

Position 37 on tRNA can carry several types of modifications, which vary among species. In eukaryotes, they include N6-isopentyladenosine (i6A) (Fig. 2), N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) and wybutosine (yW). tRNA isopentenyltransferase 1 (TRIT1) catalyzes the addition of i6A at position 37 on both cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAs in humans (Fig. 3). Re-expression of functional TRIT1 in A549 lung cancer cells significantly reduced colony formation, implicating TRIT1 as a potential lung tumor suppressor [113]. i6A is further hypermodified to 2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyl-A37 (ms2i6A) in four mitochondrial DNA-encoded tRNAs, mt-tRNATrp, mt-tRNATyr, mt-tRNAPhe, and mt-tRNASer(UCN) (Fig. 3) by a nuclear-encoded, mitochondrial enzyme, Cdk regulatory subunit-associated protein 1 (CDK5RAP1) [114]. Absence of ms2i6A due to knock down of Cdk5rap1 decreases translation of mitochondrial respiratory chain subunits, complex I, III and IV, compromising proper respiratory complex assembly and decreasing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [114]. Impairment of proper complex I and III translation in Cdk5rap1-null mice increases ROS leakage, and consequently, these mice are susceptible to oxidative stress and they exhibit accelerated myopathy and cardiac dysfunction under stressed conditions [114,115]. There are only 2 cytoplasmic tRNAs that carry i6A, cy-tRNASer(UCN) and tRNASec in mammalian cells and they are not hypermodified further [116]. The mt- tRNA t6A modification is also sensitive to CO2 as incubation of human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) in sodium bicarbonate-free tissue culture media significantly decreased t6A modifications which are rescued by sodium bicarbonate addition. The authors speculate that hypoxic conditions in solid tumors could also affect mt-tRNA t6A levels as mitochondrial CO2 is primarily provided by the TCA cycle whose activity is directly reliant on OXPHOS efficiency. Lin et al. noted that mitochondrial tRNA isolated from solid tumor xenografts decreased levels of t6A37 on tRNASer [117] suggesting that solid tumors may also display a CO2 dependency.

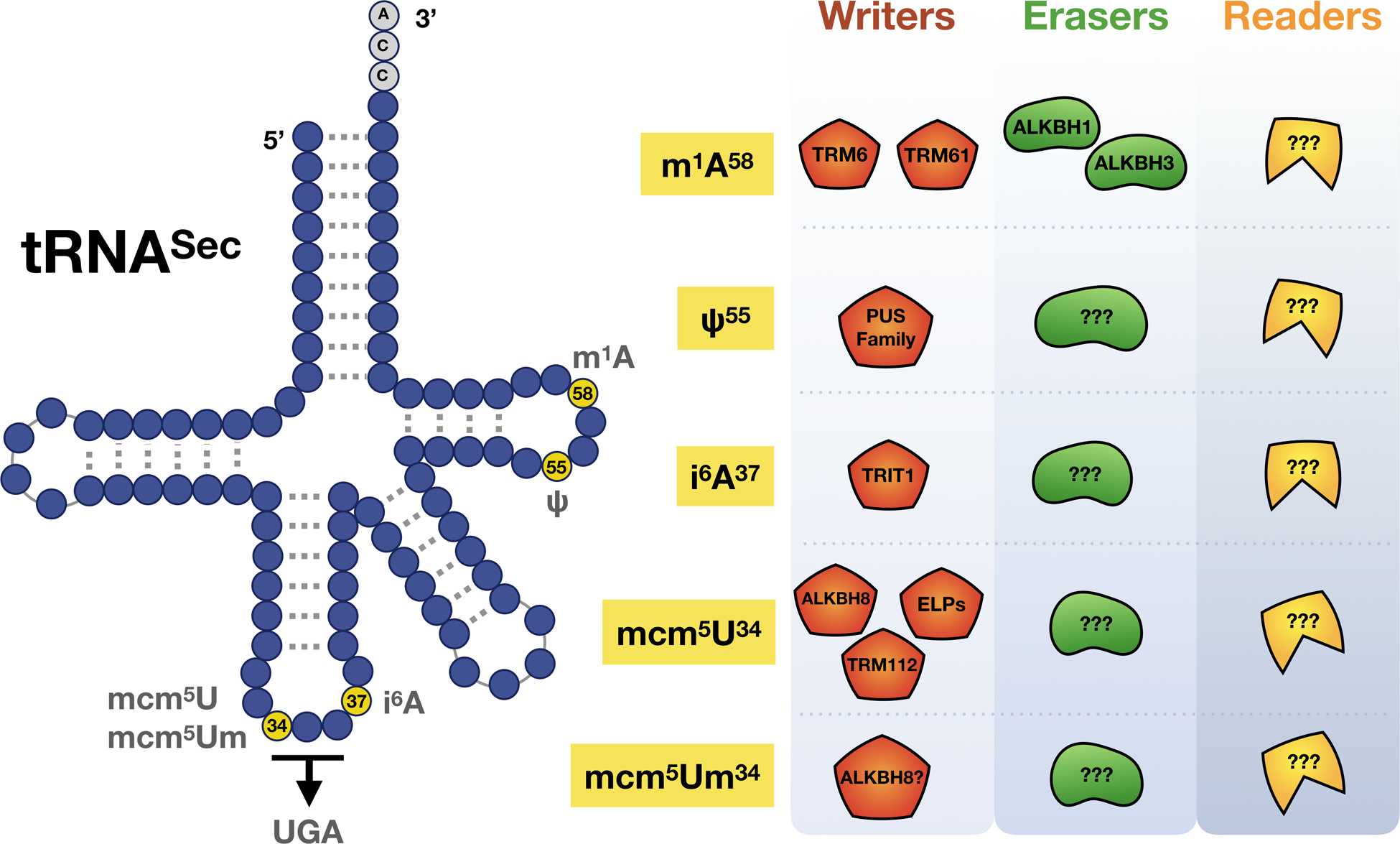

Figure 3. Readers, writers and erasers for the five major tRNASec modifications.

Known proteins and codons linked to the mcm5U, mcm5Um, i6A, Ψ and m1A modifications that play roles in regulating selenoprotein synthesis.

1.3. Epitranscriptomic Marks on Mitochondrial tRNA and their links to metabolism

Mitochondria translate some very specific transcripts into proteins that are essential for energy production and organelle function. Altered tRNA modification levels that disrupt mitochondrial function have been directly linked to the mitochondrial diseases myoclonus epilepsy associated with ragged-red fibers (MERRF) and mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) [110,118,119]. These diseases are caused by a mutation in mitochondrial tRNA genes, with the change in sequence preventing the formation of the tRNA modifications s2 and 5-taurinomethyluridine (tm5U), both disturbing codon–anticodon interactions to disrupt protein synthesis [119,120]. Defects or deficiencies in methyltransferase NSUM3 or Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase ALKBH1, which are responsible for f5C modification (Fig. 2) in mitochondria, can impair respiratory chain activity, resulting development of mitochondrial disease symptoms such as developmental disability, microcephaly, and OXPHOS deficiency in skeletal muscle [121–123]. As mitochondrial translation is used to synthesize key enzymes involved in metabolism, the resulting mistranslation defects can alter translation of mitochondrial proteins involved in the electron transport chain and ATP synthesis, and it can also dysregulate ROS levels [124]. The resulting defect in energy production is linked to the muscle weakness and neurological dysfunction associated with MERRF and MELAS, and provides a mechanistic link between tRNA modifications and energy metabolism [6].

Mitochondria are a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which are generated during OXPHOS primarily as a result of electron leak and the 1-e− reduction of molecular oxygen (O2) to superoxide (O2•-) [125]. OXPHOS utilizes 5 protein complexes, ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I), succinate dehydrogenase (complex II), ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex III), cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) and ATP synthase (complex V), to provide chemical energy for cell survival [126]. Most of the subunits of complex I, III, IV and V are synthesized on cytosolic ribosomes, followed by transportation and assembly into mitochondrial membrane, and 13 subunits of these complexes are synthesized in mitoribosome and rapidly inserted into the mitochondrial inner membrane [127]. During OXPHOS, ATP synthesis is achieved by generating proton motive force through series of electron transfer processes, in which electron donors, NADH and succinate, are oxidized by complex I and II respectively, followed by electrons being transferred to complex IV through complex III and the electrons are reduced to molecular oxygen [127]. The concentration of potential electron donors and the production rate of ATP can influence the flux of O2•- [128] that is generated from complexes I and II in the mitochondrial matrix, and in both matrix and the intermembrane space by complex III [129,130]. O2•- generated from complex III can travel into the cytosol for signaling purposes [131] or enzymatically dismuted to H2O2 by superoxide dismutase proteins, SOD1 and SOD2 [132,133]. Although mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) are vital for maintaining cellular homeostasis via redox signaling[134–137], overproduction of mtROS can induce oxidative DNA damage and a wide range of pathologies [138]. As H2O2 and other ROS inducing agents have been shown to lead to epitranscriptomic reprogramming in cytosolic tRNA [139,140], there may be changes in RNA modification levels in mitochondrial tRNAs when metabolism, ATP levels and ROS levels change. Many ROS detoxifying proteins are selenoproteins which play important roles in limiting mtROS by consuming H2O2 and protecting mitochondria from aberrant redox activity [141,142]. Thioredoxin reductase 2 (TRXR2), a member of the mitochondrial thioredoxin system, controls the level of mt- H2O2 emission by maintaining thioredoxin 2 (TRX2) in a reduced state [143]. Increased steady-state H2O2 level, followed by cell death, decreased basal mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates, and decreased maximal and reserve respiratory capacity were observed in the cells treated with auranofin, a TRXR2 inhibitor [144]. In addition, TRXR2 deficient embryonic fibroblasts are highly sensitive to ROS when glutathione synthesis is inhibited. Further, Trxr2-null embryos are smaller in size, display increased apoptosis in the liver and show decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation [145].

1.4. Epitranscriptomic marks and systems linked to transfer RNA (tRNA) for selenocysteine

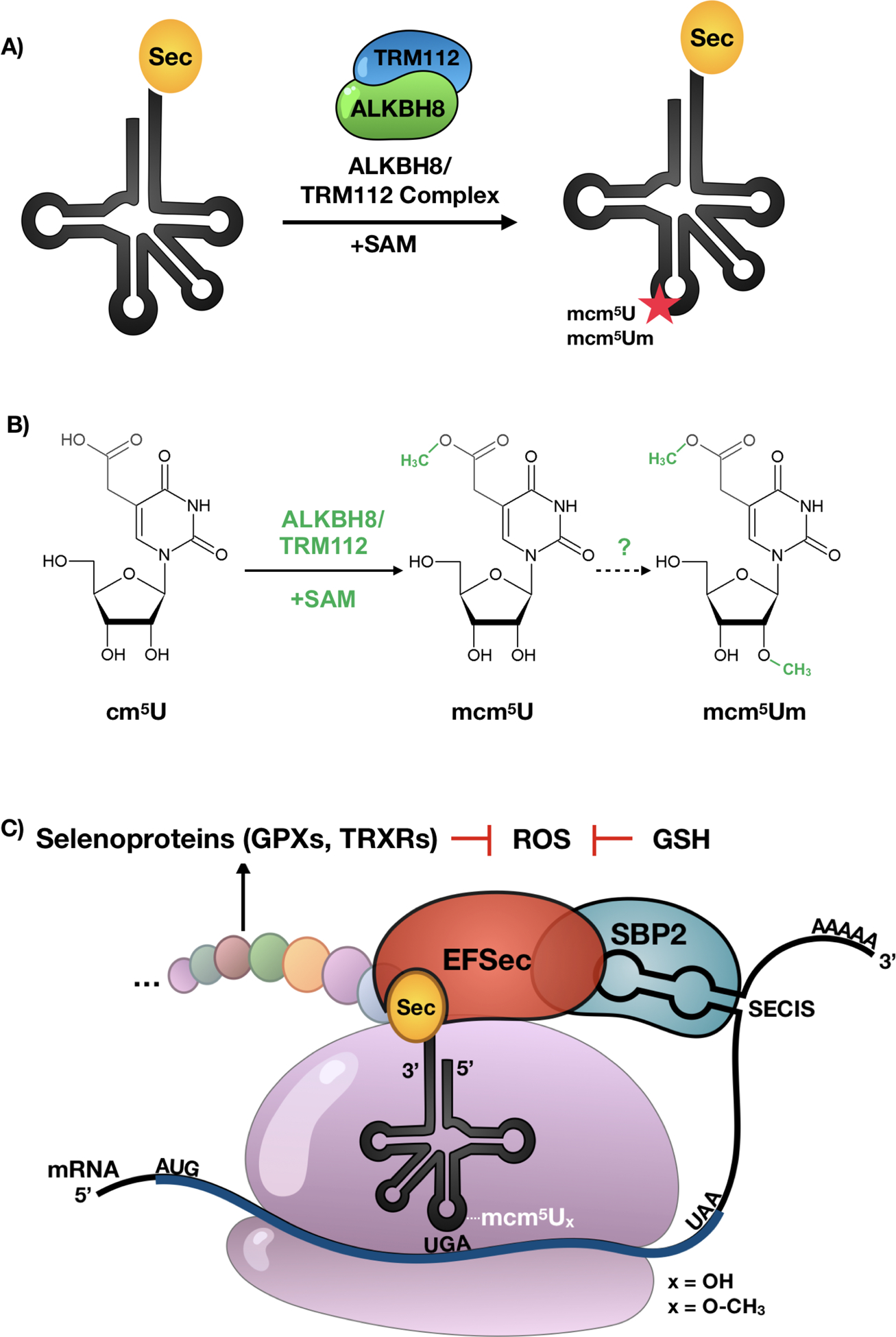

tRNASec is required for selenocysteine (Sec) biosynthesis and the production of ROS detoxifying selenoproteins. The production of selenoproteins requires a form of specialized translation called stop codon recoding, which utilizes specialized trans and cis-acting factors and is further detailed in section 1.5. Here we describe the distinct set of epitranscriptomic marks found on tRNASec that help regulate stop-codon recoding and selenoprotein synthesis, as tRNASec is the only known tRNA that governs the expression of an entire group of proteins. While canonical tRNAs contain on average 75 nucleotides, tRNASec is the longest tRNA species with 90 nucleotides in mammals and other eukaryotes (Fig. 2B and 3). This is in part due to its long variable arm and possession of the longest aminoacyl acceptor stem of any other tRNA [146,147]. tRNASec is under-modified relative to other tRNAs in humans, which contain 13 modifications on average but can have as many as 15–17, while tRNASec possesses only 5 possible epitranscriptomic marks [98,148]. tRNASec has 2 major isoacceptors: one containing mcm5U at wobble position 34, and the other mcm5Um at the same position, differing from the prior by a single methyl group addition. The 2’-O-ribosyl moiety found on mcm5Um is added to its mcm5U precursor in an ALKBH8 and selenium-dependent manner [82,100,149–151] (Fig. 2).

Multiple steps and enzymes are involved in the creation of both mcm5U and mcm5Um on tRNASec (Fig. 3). First, Uridine (U) is carboxymethylated to methyluridine (cm5U) by the ELP protein complex [152,153]. The tRNA methyltransferase ALKBH8, along with a small accessory protein TRM112, is required for the final step in the formation of mcm5U [100,154], with this precursor required for the 2’-O-ribose methylation to form mcm5Um (Fig. 4) [91]. Both tRNASec isoforms also have i6A, ψ55, and m1A modifications [150]. The i6A at position 37 is immediately 3’ of the anticodon and is catalyzed by TRIT1 in mammals. Knockdown of Trit1 results in decreased i6A and decreased selenoprotein expression in HepG2 cells [155]. The Ψ modification is catalyzed by PUS4 in eukaryotes [156–158]. The m1A mark is present at position 58 on tRNASec with this position being linked to structural stability and correct folding of the tRNA. [159]. In eukaryotes, the m1A writer is a complex consisting of catalytic protein TRM61A and RNA binding protein TRM6 [160]. The recent discovery of the m1A eraser protein ALKBH1 in mammals highlights the importance of this dynamic modification in regulating translation as ALKBH1-catalyzed demethylation results in decreased translation and usage of the unmodified tRNAs in protein synthesis [161]. The oxidative demethylase ALKBH3 is also able to remove m1A, as well as m3C, on RNA including tRNA [162,163]. ALKBH3 plays a protective function against alkylation damage on RNA via direct reversal of m1A and m3C to their original nucleosides. At the same time, it promotes angiogenin-catalyzed tRNA cleavage, an event occurring at greater frequency on unmodified tRNA, with the resulting tRNA-derived small RNAs having oncogenic functions by promoting ribosome assembly and preventing apoptosis [162,163].

Figure 4. The ALKBH8 epitranscriptomic writer regulates specialized translation by stop codon recoding.

(A-B) ALKBH8 requires a small accessory protein TRM112 along with the SAM to modify tRNASec from cm5U to mcm5U, a key step required for the formation of mcm5Um. (C) Epitranscriptomic marks work with cis and trans factors to regulate UGA stop codon recoding. Wobble uridine modifications at position 34 of tRNASec along the elongation factor EFSec, a selenocysteine insertion sequence (SECIS) in the 3’ UTR and an RNA binding protein SBP2 are required for selenoprotein synthesis. Many selenoproteins use glutathione (GSH) to regulate ROS levels.

The two tRNASec isoforms are correlated with expression levels of 2 classes of selenoproteins. In general, the mcm5U isoform is thought to serve the synthesis of housekeeping selenoproteins and, while the mcm5Um isoform is involved in translation of stress response selenoproteins and is more sensitive to selenium status [150,164,165]. These findings were elucidated using transgenic mice encoding an A→G mutation in the tRNASec gene at position 37, which results in decreased expression of selenoproteins [155]. Overexpression of the G37 tRNASec mutant led to changes in the distribution of the mcm5U and mcm5Um modifications and dysregulated specific stress responsive selenoproteins. These observations led to the realization that many of the selenoproteins responsive to selenium status are involved in stress-related functions, while those unaffected serve housekeeping functions [165,166] Epitranscriptomic marks on tRNASec are dependent not only on their writers for modification, but also on each other. For example, the m1A mod at position 37 is required for synthesis of ψ at position 55, a modification that governs tertiary structure. Likewise, mutation at any of the sites containing the i6A, m1A or ψ, or indeed any mutations that influence tRNASec secondary structure severely decreases or completely inhibit the 2’-O ribose methylation at position 34, a modification that also results in the conformational change of the tRNA [149,150].

1.5. Epitranscriptomic marks work with cis and trans factors to help regulate selenoprotein synthesis

Selenoproteins rely on a unique method of translation based on stop codon recoding because there is no dedicated codon for Sec incorporation. Sec insertion into proteins relies on cis-acting factors on the mRNA and trans-acting factors involved in bringing Sec-charged and properly modified tRNASec to the ribosome, where it recognizes and decodes the UGA stop codon (Fig. 4C). UGA recoding uses a 3’ UTR stem-loop structure termed the selenocysteine insertion sequence (SECIS) [167–169] that can help recruit machinery for specialized translation. It also uses a Sec-specific elongation factor (eEFSec), a GTP binding protein that was found to recognize charged tRNASec in vitro and in vivo [170]. Selenoproteins have expanded our understanding of the universal genetic code, which is comprised of 61 codons encoding for 20 amino acids, and 3 stop codons signaling the end of translation. The UGA stop codon has the added function of encoding for the 21st amino acid Sec, via the process of stop codon recoding [91,171–174]. Translational recoding of the UGA codon in eukaryotes is regulated by selenium availability and other core factors such as tRNASec modifications, Type I & II selenocysteine insertion sequence (SECIS) elements, SECIS Binding proteins (SBP2), elongation factors (eFSec), as well as enzyme-catalyzed epitranscriptomic marks on tRNASec [91,166,175]. Disruption of selenoprotein synthesis can occur due to selenium deficiency, mutations or changes in mRNA elements including UGA codon and SECIS elements, changes in RNA binding proteins or elongation factors involved in Sec translation, tRNASec mutations and writer deficiencies [82,168,169,175–179], with the latter two leading to decreased epitranscriptomic marks.

1.6. Selenoprotein function

25 and 24 selenoproteins have been discovered in humans and rodents, respectively. Selenoproteins can be classified into 6 functional groups: those with peroxidase/reductase activity, redox signaling, hormone metabolism, protein folding, selenium transport and Sec synthesis. The majority of selenoproteins confer protection against oxidative stress and damage, described below, but some are also involved in homeostatic processes such as calcium signaling, biosynthesis of phospholipids, and maintaining and transporting selenium within the body [180,181] (Table 1). Selenoproteins V, W and GPX4 function as essential proteins for spermatogenesis and overall vitality. The synthesis and transportation of selenium is aided by selenophosphate synthase, selenoprotein P (SEPP), and selenoprotein 15 (SEL15). The deiodinase family (DIO1–3) of selenoproteins that regulate thyroid hormone level and thyroid function[182]. Some selenoproteins have not been assigned a function. These include, Selenoprotein O, V and M.

Table 1.

The 25 human selenoproteins, their identifying information and current known functions. Selenoprotein gene nomenclature was recently updated as in [240]. We have therefore included the selenoprotein name in bold, and new and all previous abbreviations in parentheses. The abbreviation used in this manuscript is listed first.

| Selenoprotein | Number of Selenocysteine residues | Subcellular Localization | Molecular Wt (kDa) | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenoprotein K (SELK, SELENOK) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum, Plasma membrane | 10.64 | Required for T-cell proliferation and calcium flux in immune cells. Known to protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress. | [180,241–243] |

| Selenoprotein S (SELS, SEPS1, VIMP, SELENOS) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 21.16 | Protects cells from oxidative damage and ER stress-induced apoptosis. Removes misfolded proteins from ER lumen for degradation. | [180,197,202,223,241,244–247] |

| Selenoprotein O (SELO, SELENOO) | 1 | Mitochondrion | 73.49 | Cys-X-X-Sec motif suggests redox function; however, importance remains unknown. | [180,181,241] |

| Selenoprotein I (SELI, EPT1, SELENOI) | 1 | Transmembrane | 45.22 | Biosynthesis of phospholipids. Formation and maintenance of vesicular membranes. | [180,241,248] |

| Methionine sulfoxide reductase B1 (MSRB1, SELR, SELX, SEPX1) | 1 | Cytoskeleton, Nucleus | 12.76 | Methionine sulfoxide reductase. Known to be protective against neurodegeneration, lens cell viability, and oxidative damage during aging. | [180,241,249–252] |

| Selenoprotein H (SELH, SELENOH, C11orf31) | 1 | Nuclear | 13.45 | Gene expression regulator for glutathione synthesis, provides antioxidant defense. Involved in transcription. | [180,194,195,241,253] |

| Selenoprotein M (SELM, SEPM, SELENOM) | 1 | Golgi apparatus, Endoplasmic reticulum | 16.23 | Thiol-disulfide oxioreductase in endoplasmic reticulum. Role in protein folding. | [180,241,254,255] |

| Selenoprotein N (SEPN1, SELN, SEPN) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 65.81 | Regulates ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated calcium mobilization required for normal muscle development and differentiation. Regulator of redox-related calcium homeostasis and protection against oxidative stress. | [180,241,256–260] |

| Selenoprotein P (SEPP1, SELP, SELENOP) | 10 | Secreted, Cytoplasmic | 43.17 | Selenium transporter throughout organism, especially in brain and testes. Regulates glutathione peroxidase activity, heparin binding and heavy metal ion complexation. | [180,236,237,241,261–268] |

| Selenoprotein T (SELT, SELENOT) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 22.32 | Role in embryonic development and calcium mobilization. | [180,241,253,269] |

| Selenoprotein V (SELV, SELENOV) | 1 | Unknown | 36.8 | Expressed in testes. More functional evidence needed. | [180,241,253] |

| Selenoprotein W (SELW, SEPW1, SELENOW) | 1 | Cytoplasmic | 94.48 | Interacts with glutathione and plays an antioxidant role in cells. Protects developing myoblasts from oxidative stress and functions in muscle growth and differentiation. | [180,241,253,270–274] |

| Selenophosphate Synthetase 2 (SPS2, SEPHS2) | 1 | Cytosol | 47.31 | Participates in selenocysteine biosynthesis by providing selenium donor compound, selenophoasphate. Involved in synthesis of selenoproteins, including itself. | [180,241,275–277] |

| Selenoprotein 15 (SEP15, SELENOF) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 15 | Thiol-disulfide oxioreductase in endoplasmic reticulum. Maintains selenoproteins in the ER, role in protein folding. | [180,241,254,255,278] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 1 (GPX1, GSHPX1, Cytosolic Glutathione Peroxidase) | 1 | Cytoplasmic | 22 | Plays an overall recovery in cells after oxidative stress. Catalyzes the reduction of organic hydroperoxidases and H2O2. | [180,209,241,279–282] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 2 (GPX2, GSHPX-GI, Gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase) | 1 | Cytoplasmic | 21.95 | Protects intestinal epithelium from oxidative stress and defense when exposure to induced oxidative stress by ingested prooxidants or gut microbiota. | [182,283–285] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 3 (GPX3, Plasma gluthathione peroxidase) | 1 | Secreted | 25.55 | Main source in plasma is from the kidney. Serves as a local source of extracellular antioxidant capacity to protect against oxidative damage to extracellular matrix. Regulates bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) produced from platelets and vascular cells. | [180,241,286,287] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4, Phosholipid hydroperoxide gluthathione peroxidase) | 1 | Mitochondrion, Cytoplasmic | 22.18 | Facilitates reverses oxidation of lipid peroxides and metabolism of lipids such as arachidonic acid and linoleic acid. Protective role in cardiovascular disease by decreasing lipid peroxidation. Dual roles as an enzyme and structural protein, transformed in later stages of spermatogenesis into structural protein that becomes a constituent of mitochondrial sheath of spermatozoa. | [180,211,241,288–292] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 6 (GPX6, Olfactory gluthathione peroxidase) | 1 | Secreted | 24.97 | Expression restricted in developing embryo and olfactory epithelium in adults. Expected to have antioxidant role, more definitive evidence for role is needed. | [180,241,293] |

| Thioredoxin reductase I (TRXR1, TXNRD1, TR1) | 1 | Cytoplasmic, nuclear | 70.91 | Gene deletion is embryonic lethal. May possess glutaredoxin activity. Critical electron donor system in DNA replication during S-phase growth. | [180,241,294–299] |

| Thioredoxin reductase II (TRXR2, TXNRD2, TR3, Mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase) | 1 | Mitochondrion | 56.51 | Deletion is embryonic lethal. Regulation of mitochondrial redox homeostasis. Role in cardiomyocyte viability. | [180,191,193,241,300,301] |

| Thioredoxin-glutathione reductase (TRXR3, TXNRD3, TR2, TGR, Thioredoxin reductase 3) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum, Nucleus | 70.68 | Promotes disulfide bond formation in various sperm proteins. | [180,241,302] |

| Iodothyronine deiodinase I (DIO1, D1) | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 28.92 | Important for systemic active thyroid hormone levels. Providing source of plasma T3 by deiodination of T4 in peripheral tissues such as liver and kidney. | [180,224,241,303,304] |

| Iodothyronine deiodinase II (DIO2, D2) | 1 | Membrane | 30.55 | Important for local active thyroid hormone levels. Essential for providing the brain with appropriate levels of T3 during critical development period. | [180,241,303,305–309] |

| Iodothyronine deiodinase III (DIO3, D3) | 1 | Endosome membrane, Plasma membrane | 33.95 | Inactivates thyroid hormone. | [180,241,303,304] |

1.7. Selenoproteins as essential participants in stress responses

Selenoproteins are key regulators of stress responses, metabolism, and immunity. A majority of selenoproteins play a role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and viability, serving as antioxidant enzymes to mitigate damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Examples of these selenoproteins include selenoprotein K, S, H, N, GPX1–4, TRXR1–3. Many selenoproteins play vital roles in embryonic vitality and development. More than half of the human selenoproteins have a thioredoxin-like fold and are involved in thiol-dependent reactions and play roles in redox homeostasis. Redox signaling is involved in regulating many of the characteristics of cancer cells, which often exhibit dysregulated redox homeostasis and continuous and elevated production of ROS. Selenoprotein links to cancer are extensive and can be found as part of a number of excellent reviews and broad population studies [183–186]. GPX1 remains one of the best-characterized selenoproteins, and given its broad function as an antioxidant is a prime candidate in cancer risk, discussed in section 1.8. GPX1 is one of five Sec-containing GPXs capable of reducing H2O2 and lipid hydroperoxides using glutathione as the electron donor, protecting cells against oxidative damage via the reaction:

Glutathione disulfide (GSSG) is returned to its reduced and active state by glutathione reductase (GR) using NADPH as the electron donor. GPX1 is expressed in almost all cell types and is critical to maintaining proper redox balance within the body. This is especially true under stress as GPX1 deficient mice are more susceptible to ROS-inducing agents such as H2O2 and lung inflammation and damage due to influenza infection and cigarette smoke [187–189].

TRXRs are Sec-containing proteins critical for a variety of cellular functions, including all signaling pathways in which thioredoxin is involved as a reducing agent. Thioredoxins can reduce oxidized protein cysteine residues to form reduced disulfide bonds, and are maintained in their reduced and active state by TRXRs using NADPH as an electron donor. This system is critical for signaling pathways involved in the protection from oxidants [190]. TRXRs are also required for development as complete knockout of both TRXR1 and TRXR2 in mice result in severe growth abnormality and embryonic death at day 8.5 and 13, respectively [191–193]. Like GPXs, TRXRs play roles in the etiology of many cancers, further discussed in section 1.8.

Selenoprotein H (SELH), a dual-function selenoprotein acting as both a transcription factor for antioxidants and phase II metabolism enzymes, and also exhibiting oxidoreductase activity [194]. SELH was originally described as a thioredoxin reductase-like protein with significant glutathione peroxidase-like activity [195]. Overexpression of SELH protects neuronal HT22 cells against UVB-induced injury and death by inhibiting apoptotic cell death pathways and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and function, and suppression of superoxide production. Another selenoprotein involved in the response to stress is Selenoprotein S (SELS, also called VIMP). SELS is a widely expressed transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) important for managing ER stress in mammals via elimination of misfolded proteins [196–198]. SELS is also involved in regulating many important processes, such as oxidative stress [199], inflammation [200–202], adipogenesis [203], and apoptosis [198]. It has been shown that a polymorphism in the promoter region of the SelS gene (−105G→A) results in increased inflammatory markers IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α [202].

1.8. Selenoproteins and their link to human diseases

Studies have shown a link between dysregulation in selenoprotein biosynthesis and an increased risk of disorders affecting many major organ systems in the body. Mutations in the promoter region of genes for selenoproteins, the SECIS element, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or deletions in the coding frame have also been linked to the etiology of many cancers (Table 2). GPX1 is decreased in some tumors [204], while overexpression of GPX1 has been found to reduce tumor growth [205,206]. Associations between GPX1 and cancer risk have been found to include prostate [207], thyroid [208], head/neck cancer [209] and breast cancer [183,210]. Two Gpx1 polymorphisms in European populations are associated with advanced-stage prostate cancer risk: rs17650792 and rs1800668 [207]. GPX4 is unique among the protein family in that it can reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides [211]. Human population studies have shown that Gpx4 polymorphism is associated with increased risk for colon [212] and prostate cancer [213]. TRXR1 and TRXR2 have been linked to cancer etiology of the prostate, colon, and rectum [214–216]. Colorectal cancer has also been associated with polymorphisms in the selenoprotein SEP15 [217]. An in vitro study using mouse colon carcinoma CT26 cells suggests tumor-promoting effects of TRXR1, as well as SEP15, as cells with targeted knockdown of either selenoproteins exhibited reduced growth. Surprisingly, knockdown of both reversed the tumor-suppressive property suggesting that the two selenoproteins participate in interfering regulatory pathways in colon cancer cells [218].

Table 2.

Human population studies or mammalian models for specific selenoproteins and their link to human diseases.

| Disease Category | Selenoprotein | Cause | Disorder | Link or contributing factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune | Selenoprotein K | Deletion in all tissues | Immune disorder | Deficient Ca2+ flux in immune cells. | [310] |

| Cancer (Gastric) | Selenoprotein S | Polymorphism | Gastric cancer | Chinese Hunan Han and Japanese populations. | [220,311] |

| Intestinal | Selenoprotein S | Polymorphism | Inflammatory bowel disease | SelS mRNA expression is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines in Intestinal epithelial cells. However, the SelS –105G>A polymorphism is not associated with inflammatory bowel disease susceptibility. | [221] |

| Endocrine | Selenoprotein S | Polymorphism | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Polymorphism in the promoter region. | [222] |

| Cardiac | Selenoprotein S | Polymorphism | Coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke | Genetic variant rs8025174 increased coronary heart disease risk by 2.95 fold. Genetic variant rs7178239 increased risk of ischemic stroke by 3.35 fold, both in females in Finland. |

[223] |

| Cancer (Colorectal) | Selenoprotein S | Polymorphism | Colorectal cancer | SNP in SelS gene (rs34713741) associated with 2.25 increase in odds of colorectal cancer in females in a Korean population. | [217] |

| - | Selenoprotein O | - | Unknown | - | - |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein I | Exon skipping | Neurological disorders, inhibited neurodevelopment, inadequate myelination in the brain. | From case study of one patient, and in vitro in SELI deficient HeLa cells. | [312] |

| Neurological | Methionine sulfoxide reductase B1 | Deficiency | Alzheimer’s | MSRB1 possibly plays a protective role against Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A human fetal brain cDNA screen showed that MSRB1 interacts with Clusterin (CRU). This was shown to be a synergistic interaction, with CRU also interacting with the β-amyloid peptide, a pathological protein in AD. | [313,314] |

| Whole-body | Methionine sulfoxide reductase B1 | Knockout | Growth delays & increased oxidative stress | MSRB1 deficient mice have growth delays and increased oxidative stress, a phenotype exacerbated by dietary methionine deficiency. | [315,316] |

| Cancer (Colorectal) | Selenoprotein H | Overexpression | Colorectal cancer | In vivo & in vitro link between SELH overexpression and colorectal cancer. | [219] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein M | Decreased expression | Alzheimer’s disease | SELM may prevent β-Amyloid aggregation by resisting oxidative stress generated during β-Amyloid oligomer formation. In vivo link, SELM may play a protective role in the pathology of patients with Alzheimer’s. | [317,318] |

| Muscular | Selenoprotein N | Nonsense mutation | Rigid spine muscular dystrophy | Nonsense mutation in selenocysteine codon (TGA → TAA), preventing Sec insertion and resulting in short proteins. Missense and frameshift mutations in the ORF, and mutation in SECIS element (3’ UTR) all lead to rigid spine muscular dystrophy. | [178,257,258] |

| Muscular | Selenoprotein N | Knockout | Impaired muscle repair | SepN1−/− mouse model shows depletion of satellite cells required for muscle repair after injury resulting in impaired and imperfect repair. Muscle biopsies of patients with SepN1 mutation shows decreased satellite cells. | [319] |

| Muscular | Selenoprotein N | Mutation in SRE element | SEPN1-related myopathy | A single missense mutation (c.1397G>A) in the SepN1 SRE significantly reduces Sec insertion, destabilizes the mRNA and leads to decreased SEPN1 protein levels. | [320] |

| Intestinal | Selenoprotein P | Polymorphism | Colorectal cancer | Polymorphism in promoter region (rs2972994) | [212] |

| Intestinal | Selenoprotein P | Deficiency | Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease | Decrease in serum SEPP1 levels | [321] |

| Metabolic | Selenoprotein P | Increase in secreted protein from liver | Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia & (inferred) type 2 diabetes | In vitro, in vivo, and population studies | [322] |

| Metabolic | Selenoprotein P | Increase in circulating Selenoprotein P | Hyperglycemia | Japanese population. Elevation of circulating SEPP1 positively correlated with onset of hyperglycemia. | [323] |

| Musculoskeletal | Selenoprotein P | Polymorphism | Kashin-Beck disease | Du et al show that SNP in Sepp1 −105G>A gene associated with Kashin-Beck disease (KBD), with the AA genotype conferring significant risk. Sun et al show that KBD patients have significantly decreased serum SEPP1 levels compared to controls. | [324,325] |

| Renal | Selenoprotein P | Deficiency | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Decrease in SEPP1 and Se levels | [326] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein P | Knockdown | Alzheimer’s Disease | In vitro study in Neuronal N2A cells knows that RNAi knockdown of SEPP1 causes amyloid-beta induced toxicity and cell death. | [327] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein P | Decreased expression | Parkinson’s Disease | SEPP1 expression reduced in neurons of substantia nigra of Parkinson’s patients (post-mortem analysis of brain) | [328] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein P | Deletion | Impaired neurological function | Sepp1−/− mouse models show impaired function of parbalbumin (PV)-interneurons and changes in fear learning and sensorimotor gating. | [233] |

| Multiple | Selenoprotein P | Knockout | Reproductive disorder, neurological disorder | Required for Se homeostasis and metabolism. Diet dependent movement abnormality and weight loss when Sepp1−/− mice fed a low Se diet. | [236,237] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein T | Under- and overexpression | Parkinson’s disease | In vitro, in vivo, and patient studies. Complete deletion in mice results in embryonic lethality. | [329] |

| Neurological | Selenoprotein T | Conditional Knockout in nerve cells | Neurodevelopmental abnormalities, hyperactive behavior | SelT−/− young mice had reduced volume of hippocampus, cerebellum and cerebral cortex, and although compensated in adulthood the mice had hyperactive behavior. | [330] |

| Endocrine | Selenoprotein T | Conditional knockout of SelT in pancreatic β cells | Impaired glucose tolerance, decreased insulin production and secretion | In mouse pancreatic β cells. | [331] |

| - | Selenoprotein V | - | Unknown | - | - |

| Hypertension |

Selenoprotein W | Polymorphism | Pre-Eclampsia | SelW polymorphism (rs3786777) did not affect risk factor for pre-eclampsia (PE) in pregnant women, but PE patients had significantly lower circulating SELW protein levels. | [332] |

| Cancer (Colorectal) | Selenoprotein 15 | Polymorphism | Colorectal Cancer | In a Korean population, polymorphism in rs5845 and rs5859 in Sep15 significantly correlated with increased rectal cancer in males. | [217] |

| Eye | Selenoprotein 15 | Knockout | Cataract Development | Mice were viable and fertile, but had elevated oxidative stress in livers and cataract formation early in life. | [333] |

| Cancer (Colon) | Selenoprotein 15 | Targeted downregulationof Sep15 | Colon Cancer | In vitro mouse colon carcinoma study using mouse colon carcinoma CT26 cells. Downregulation of Sep15 suppresses cancer cell growth, suggesting a tumor-promoting property of SEP15. | [218] |

| Bone | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Polymorphism | Kashin-Beck disease | Tibetian population, Chinese Han population | [334,335] |

| Cancer (Thyroid) | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Oxidative stress | Thyroid cancer | Data from cancer patients. | [208] |

| Cancer (Bladder) | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Polymorphism | Bladder cancer | A polymorphism in Gpx1 resulting in an amino acid substitution (Pro198Leu) played a protective role against bladder cancer recurrence. WT patients had marginally shorter survival (p = 0.066), which was reduced to (p = 0.036) in whites. | [336] |

| Cancer (Head/Neck)/ Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Gpx1 expression level | Head/Neck cancer | A negative correlation between tumor stage and GPX1 expression was found in pre-treatment biopsies of head/neck cancer patients. | [209] |

| Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | IncreasedGpx1 expression and activity | Huntington’s Disease | Increased GPX1 expression and activity in Huntington Disease patients | [337] |

| Cancer (Breast) | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Loss of hetero-zygosity | Breast Cancer | Leucine vs. proline at GPX1 position 198 assessed, with leucine-containing allele more frequently associated with breast cancer samples. | [210] |

| Cancer (Prostate) | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Polymorphism | Prostate Cancer | Polymorphism in rs17650792 and rs1800668 associated with increased advanced colorectal cancer risk. | [207] |

| Gastrointestinal | Glutathione peroxidase 2 | Double knockout of Gpx1 & Gpx2 | Colitis | Combined disruption of Gpx1 and Gpx2 in mice. | [281] |

| Cancer (Rectal) | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | Polymorphism | Rectal Cancer | Genetic variablility in Gpx3 alters risk of rectal cancer, but not colon cancer (study identified 3 different polymorphisms, and in this case resulted in reduced risk of cancer). | [338] |

| Cancer (Colorectal) | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Polymorphism | Colorectal Cancer | rs713041 polymorphism in Gpx4 increases risk for colorectal cancer. | [212] |

| Cancer (Prostate) | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Polymorphism | Prostate Cancer | Gpx4 polymorphism (rs2074452) linked to increase in prostate cancer risk and prostate-cancer specific mortality. | [213] |

| Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Decreased expression | Parkinson’s Disease | Reduced GPX4 expression in neurons of substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease patients (post-mortem analysis of brain). | [339] |

| Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Conditional knockout in neurons | Neurodegeneration in the hippocampus, seizures, | Conditional knockout in mouse neurons. | [231] |

| Embryonic | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Knockout | Embryonic lethality day 7.5 | Mouse embryos display lack of normal structural compartmentalization. | [230] |

| Bone | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Decreased mRNA levels | Kashin-Beck Disease | Decreased Gpx4 mRNA results in increased risk for Kashin-Beck Disease. | [340] |

| Bone/Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Exon skipping | Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SSMD) | 2 unrelated human cases with mutation in Gpx4 gene resulting in exon skipping, part of exon 4 in one case and exon 5 in another case. Severe bone defects and neurological abnormalities noted. | [232] |

| Renal | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | Knockout | Renal failure | Gpx−/− mice have increased ferroptosis-mediated cell death and lipid oxidation induced renal failure | [341] |

| Neurological | Glutathione peroxidase 6 | Increased expression level |

Huntington’s Disease | GPX6 increased in striatum. | [337] |

| Cancer (Colon) | Thioredoxin reductase I | Targeted downregulationof TrxR1 | Colon Cancer | In vitro mouse colon carcinoma study using mouse colon carcinoma CT26 cells. Downregulation of TrxR1 suppresses cancer cell growth, suggesting a tumor-promoting property of TRXR1. | [218] |

| Embryonic | Thioredoxin reductase I | Knockout | Embryonic lethality day 8.5 | Severe growth abnormalities, primitive streak mesoderm does not form (i.e. failure to gastrulate). | [191,192] |

| Cancer (Prostate) | Thioredoxin reductase I | Polymorphism | Prostate Cancer | TrxR1 SNPs rs11610799 and rs7138318 associated with increased risk for prostate cancer. | [215] |

| Cancer (Prostate) | Thioredoxin reductase II | Polymorphism | Prostate Cancer | TrxR2 SNPs rs3788317 and rs599245 associated with increased risk for prostate cancer. | [215] |

| Cardiac | Thioredoxin reductase II | Knockout | Cardiac failure and dilated cardiomyopathy | Complete knockout of TrxR2 in mice results in embryonic lethality at day 13. | [193] |

| Thyroid | Iodothyronine deiodinase I | Targeted disruption | Thyroid hormone disorder | Changes in thyroid hormone metabolism and excretion. | [224] |

| Neurological | Iodothyronine deiodinase II | Deletion of major coding exon of DIO2 | Auditory defects | Hearing loss and failed cochlear development in Dio2−/− mice. | [225] |

| Muscle | Iodothyronine deiodinase III | Ablated SECIS region of Dio3 gene | Muscle disorder | Defects in muscle regeneration. | [342] |

| Thyroid | Iodothyronine deiodinase III | Knockout | Hypothyroidism | Dio3−/− mice have hypothyroidism and defects in formation and function of thyroid axis. | [343] |

| Neurological | Iodothyronine deiodinase III | Deletion | Auditory defects | Failed cochlear development. | [226] |

| Neurological/ metabolic | Iodothyronine deiodinase III | Deletion | Disruption of circadian rhythm | Dio3−/− mice display leptin resistance, disrupted circadian rhythm and elevated energy expenditure & disrupted energy balance, and increased fat loss in response to T3 treatment. | [228] |

| Neurological, Metabolic | SECIS binding protein 2 (SBP2) | Nonsense Mutation, nonfunctional SBP2 protein | Abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism, delayed bone maturation, congenial myopathy, impaired mental development and motor coordination | Case study of 1 patient with mutation in SBP2 resulting in absence of all functional domains of the protein and severe developmental, neurological and metabolic phenotype. | [344] |

| Embryonic | SECIS binding protein 2 (SBP2) | Knockout | Embryonic lethal day 7.5 | Mouse SBP2 knockout model | [345] |

| Cancer | Alkylation repair homolog 8 | Overexpression | Bladder cancer | ALKBH8 is overexpressed in bladder cancer and promotes cancer progression.Knockdown causes death of cancer cells via downregulation of survivin. | [346,347] |

| Neurological | Alkylation repair homolog 8 | Truncating Mutation | Intellectual Disability | Study of two consanguineous families, truncating mutations in ALKBH8 lead to complete lack of ALKBH8-dependent tRNA modifications and intellectual disabilities. | [348] |

| Embryonic | Trsp | Knockout | Embryonic lethal day 6.5 | Mice with a targeted deletion of trsp gene died on day 6.5. | [176] |

| Neurological | Trsp | Conditional knockout in neurons | Neurodegeneration | Mouse model with inactivated trsp in neurons resulted complete loss of expressions. Loss of balance, growth delays, seizures and neurodegeneration evident. | [229] |

| Metabolic/Endocrine | Selenocysteine tRNA | i6A mutant | Diabetes | Reduced synthesis of selenoproteins due to an overexpression of i6A-mutant tRNASec. | [349] |

| Mitochondrial | TRIT1 (i6A writer) | TRIT1 mutation | Combined mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation deficiency | Defective i6A tRNA modifications | [350] |

| Reproductive/Neurological | ALKBH1 (m1A eraser) | Deletion | Sex ratio distortion and unilateral eye defects | One female mouse born for every 3–4 males (sex ratio distortion). Eye defects and craniofocal malformations also observed. | [351] |

| Neurological | ALKBH1 (m1A eraser) | Deletion | Embryonic lethal, histone H2A methylation defects | Most mice die at embryonic stage due to defects in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Also evidence of defects in histone H2A methylation. | [352] |

| Cancer (lung) | ALKBH3 (m1A eraser) | Overexpression | Non-small-cell lung cancer | Knockdown of ALKBH3 reduced both number and diameter of tumors in the peritoneum after mice were inoculated with the A549 human lung carcinoma cell line. | [353] |

| Cancer (prostate) | ALKBH3 (m1A eraser) | Overexpression | Human Prostate Carcinoma | ALKBH3 (alt name prostate cancer antigen 1 (PCA-1)) highly expressed in human prostate cancer. | [354,355] |

SelH transcripts and protein are overexpressed in some cancer cells such as LCC1 (lung cancer) and LNCaP (human prostate carcinoma)[195]. Overexpression of SELH has also been shown in human and mouse-derived colorectal cancer tissue [219]. Mutations specifically in the promoter region of SELS have been linked to gastric cancer [220], inflammatory bowel disease [221] and hashimoto’s thyroiditis [222]. SELS population studies also suggest disease risks due to genetic variants; polymorphism rs8025174 has been linked to increased risk of coronary heart disease, and rs7178239 has been linked to more than a 3-fold increase in risk of ischemic stroke in females [223]. Deletion of selenoproteins DIO2 and DIO3 has been linked to defects in the auditory and visual systems. In general, deiodinases catalyze the elimination of iodide from thyroid hormones. Although DIO1 deletion was not associated with any neurological phenotype [224], deletion of DIO2 resulted in hearing loss and malformations in the cochlea in mice [225]. Dio3−/− mice also display hearing loss, but unlike the Dio2−/− mice they had accelerated cochlear differentiation [226]. In addition, Dio3−/− mice had defects in retinal photoreceptor development and a loss of about 80% of cone photoreceptors affecting light and color vision [227]. Lastly, Dio3−/− mice were shown to have disrupted energy balance, leptin resistance, and a disrupted circadian rhythm [228].

The brain expresses almost all selenoproteins and mutations or deficiencies in selenoproteins are linked to a number of neurological dysfunctions. A conditional inactivation of the mouse tRNASec gene trsp in neurons resulted in total loss of selenoprotein expression in neurons and severely decreased expression in the cerebrum phenotypically resulting in loss of balance, growth retardation, seizures and neurodegeneration in mutant mice [229]. Complete inactivation of Gpx4 is embryonic lethal in mice [230,231], but mice with a conditional knockout of Gpx4 in neurons were found to have massive degeneration [229]. Mutations in Gpx4 in two separate human cases resulted in the embryonic lethal bone defect Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SSMD), a defining feature of which is also central nervous system abnormality [232]. Deletion of Selenoprotein P (Sepp1) in mice has been associated with neurological dysfunction including prevalence of seizures and decrease in activity, grooming behavior and motor coordination and delays in fear learning [233–235]. Sepp1 deletion results in drastically reduced selenium delivery to the brain [236,237]. These neurological phenotypes increased in male relative to female mice suggesting that male mice are more dependent on SEPP1 and Se for normal brain function [235].

1.8. Concluding thoughts, epitranscriptomic marks could be linked to many diseases

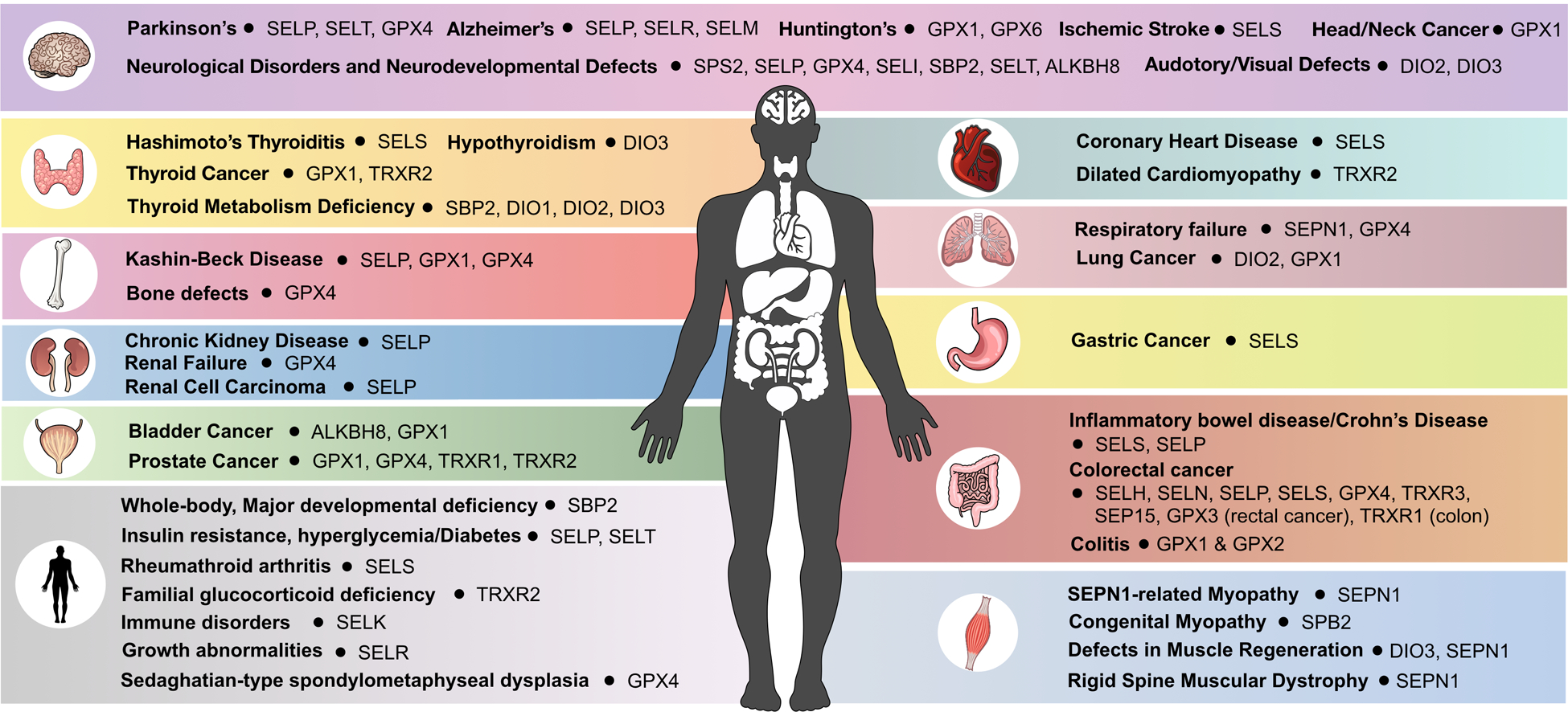

In this review we have highlighted examples of enzyme-catalyzed epitranscriptomic marks on RNA, and described how epitranscriptomic systems can function as regulatory elements during translation. Defects in RNA epitranscriptomic marks and their associated epitranscriptomic readers/writers/erasers have been linked to a number of human diseases, including developmental defects, neurological disorders, and cancer. The epitranscriptomic writer ALKBH8 is essential for promoting translation of selenoproteins, which are critical for development, homeostatic functions and stress responses. To date, studies have elucidated the function many human selenoproteins, outlined in Table 1, which includes redox signaling, oxidoreductase activity, selenium transport and storage, Sec synthesis, protein folding, and hormone metabolism. While it is clear that selenoproteins play critical roles in development and proper function of cells, organs, and organ systems, the human disease associations are complex. We highlight the importance of selenoproteins in detoxifying ROS, of which more than half of selenoproteins play important roles. Human and animal studies demonstrate the importance of properly regulated selenoprotein synthesis in preventing diseases of nearly every major organ system in the body; often involving biochemical pathways in the oxidative stress response (Table 2). The study of broad selenoprotein deficiency, such as in the case of disrupted UGA stop codon translation as a result of epitranscriptomic deficiencies, is also helpful in identifying the global role of selenoproteins in health and development.

The term “epitranscriptomics” was coined in 2012 [238,239], and a growing body of literature has identified more than 140 post-transcriptional modifications present on every type of RNA. Many studies discussed herein support the idea that RNA modifications function as an added level of translational control in stress responses. Deficiencies in writers and erasers have been linked to disrupted function and disease, with strong links between ALKBH1–3 and TRIT1 to ROS, mitochondrial function and cancer. Mitochondria are major sources of ROS production and rely on epitranscriptomic marks for regulated translation of ROS-management proteins, with mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase (TRXR2) being a prime example. Disruption of various RNA marks in mitochondria can also lead to disrupted OXPHOS and/or ATP synthesis often culminating in dysregulated ROS levels and resulting in devastating disorders such as developmental and neurological disability, cancer, and a host of other free radical diseases. We have endeavored to shed light on the significance of epitranscriptomic systems in regulating translation and mitochondrial function and their links to disease states, especially as they pertain to the specialized translation and function of selenoproteins.

Figure 5. Diseases linked to selenoproteins and dysregulated epitranscriptomic marks on tRNASec.

The 25 human selenoproteins and tRNASec writers and erasers were linked to diseases based on studies in mammalian systems (mammalian cells or animal models) and human diseases.

1.9. References

- [1].Bohacek J, Mansuy IM, Epigenetic inheritance of disease and disease risk, Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (2013) 220–236. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Johnstone SE, Baylin SB, Stress and the epigenetic landscape: A link to the pathobiology of human diseases?, Nat. Rev. Genet 11 (2010) 806–812. doi: 10.1038/nrg2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lian CG, Xu Y, Ceol C, Wu F, Larson A, Dresser K, Xu W, Tan L, Hu Y, Zhan Q, Lee CW, Hu D, Lian BQ, Kleffel S, Yang Y, Neiswender J, Khorasani AJ, Fang R, Lezcano C, Duncan LM, Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, Kakavand H, Houvras Y, Zon LI, Mihm MC, Kaiser UB, Schatton T, Woda BA, Murphy GF, Shi YG, Loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is an epigenetic hallmark of Melanoma, Cell. 150 (2012) 1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chan CTY, Deng W, Li F, Demott MS, Babu IR, Begley TJ, Dedon PC, Highly Predictive Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications Is Linked to Selective Expression of Codon-Biased Genes, Chem. Res. Toxicol 28 (2015) 978–988. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chan CTY, Dyavaiah M, DeMott MS, Taghizadeh K, Dedon PC, Begley TJ, A Quantitative Systems Approach Reveals Dynamic Control of tRNA Modifications during Cellular Stress, PLoS Genet. 6 (2010) e1001247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dewe JM, Fuller BL, Lentini JM, Kellner SM, Fu D, TRMT1-catalyzed tRNA modifications are required for redox homeostasis to ensure proper cellular proliferation and oxidative stress survival, Mol. Cell. Biol 37 (2017) MCB.00214–17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00214-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chionh YH, McBee M, Babu IR, Hia F, Lin W, Zhao W, Cao J, Dziergowska A, Malkiewicz A, Begley TJ, Alonso S, Dedon PC, tRNA-mediated codon-biased translation in mycobacterial hypoxic persistence, Nat. Commun 7 (2016) 1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boccaletto P, MacHnicka MA, Purta E, Pitkowski P, Baginski B, Wirecki TK, De Crécy-Lagard V, Ross R, Limbach PA, Kotter A, Helm M, Bujnicki JM, MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update, Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (2018) D303–D307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dubin DT, Taylor RH, The methylation state of poly A-containing-messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells, Nucleic Acids Res. 2 (1975) 1653–1668. doi: 10.1093/nar/2.10.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Camper SA, Albers RJ, Coward JK, Rottman FM, Effect of undermethylation on mRNA cytoplasmic appearance and half-life., Mol. Cell. Biol 4 (1984) 538–43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6201720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen S, Habib G, Yang C, Gu Z, Lee B, Weng S, Silberman, Cai S, Deslypere J, Rosseneu M, Et A, Apolipoprotein B-48 is the product of a messenger RNA with an organ-specific in-frame stop codon, Science (80-.) 238 (1987) 363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.3659919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Powell LM, Wallis SC, Pease RJ, Edwards YH, Knott TJ, Scott J, A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine, Cell. 50 (1987) 831–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Teng B, Burant C, Davidson N, Molecular cloning of an apolipoprotein B messenger RNA editing protein, Science (80-.) 260 (1993) 1816–1819. doi: 10.1126/science.8511591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Davidson NO, Innerarity TL, Scott J, Smith H, Driscoll DM, Teng B, Chan L, Proposed nomenclature for the catalytic subunit of the mammalian apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme: APOBEC-1., RNA. 1 (1995) 3 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7489485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Smith HC, Bennett RP, Kizilyer A, McDougall WM, Prohaska KM, Functions and regulation of the APOBEC family of proteins, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 23 (2012) 258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bass BL, Weintraub H, A developmentally regulated activity that unwinds RNA duplexes, Cell. 48 (1987) 607–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90239-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, Nemzer S, Hallegger M, Shemesh R, Fligelman ZY, Shoshan A, Pollock SR, Sztybel D, Olshansky M, Rechavi G, Jantsch MF, Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome., Nat. Biotechnol 22 (2004) 1001–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maas S, Rich A, Nishikura K, A-to-I RNA editing: recent news and residual mysteries., J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 1391–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Higuchi M, Maas S, Single FN, Hartner J, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2., Nature. 406 (2000) 78–81. doi: 10.1038/35017558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rueter SM, Dawson TR, Emeson RB, Regulation of alternative splicing by RNA editing., Nature. 399 (1999) 75–80. doi: 10.1038/19992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Scadden ADJ, O’Connell MA, Cleavage of dsRNAs hyper-edited by ADARs occurs at preferred editing sites., Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (2005) 5954–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Scadden AD, Smith CW, Specific cleavage of hyper-edited dsRNAs., EMBO J. 20 (2001) 4243–52. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen CX, Cho DS, Wang Q, Lai F, Carter KC, Nishikura K, A third member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene family, ADAR3, contains both single- and double-stranded RNA binding domains., RNA. 6 (2000) 755–67. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mladenova D, Barry G, Konen LM, Pineda SS, Guennewig B, Avesson L, Zinn R, Schonrock N, Bitar M, Jonkhout N, Crumlish L, Kaczorowski DC, Gong A, Pinese M, Franco GR, Walkley CR, Vissel B, Mattick JS, Adar3 is involved in learning and memory in mice, Front. Neurosci 12 (2018) 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maas S, Gerber AP, Rich A, Identification and characterization of a human tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase related to the ADAR family of pre-mRNA editing enzymes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 96 (1999) 8895–8900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].V Murphy F, Ramakrishnan V, Structure of a purine-purine wobble base pair in the decoding center of the ribosome, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11 (2004) 1251–1252. doi: 10.1038/nsmb866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dominissini D, Rechavi G, Loud and Clear Epitranscriptomic m1A Signals: Now in Single-Base Resolution, Mol. Cell 68 (2017) 825–826. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, Sorek R, Rechavi G, Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq, Nature. 485 (2012) 201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Squires JE, Patel HR, Nousch M, Sibbritt T, Humphreys DT, Parker BJ, Suter CM, Preiss T, Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA, Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (2012) 5023–5033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pullirsch D, Jantsch MF, Proteome diversification by adenosine to inosine RNA-editing, RNA Biol. 7 (2010) 205–212. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.2.11286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Li X, Xiong X, Zhang M, Wang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, Mao Y, Lv J, Yi D, Chen X-W, Wang C, Qian S-B, Yi C, Base-resolution mapping reveals distinct m1A methylome in nuclear- and mitochondrial-encoded transcripts, 68 (2017) 993–1005. doi: 10.1002/stem.1868.Human. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Niu Y, Zhao X, Wu YS, Li MM, Wang XJ, Yang YG, N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: An Old Modification with A Novel Epigenetic Function, Genomics, Proteomics Bioinforma 11 (2013) 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maity A, Das B, N6-methyladenosine modification in mRNA: Machinery, function and implications for health and diseases, FEBS J. 283 (2016) 1607–1630. doi: 10.1111/febs.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T, N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein, Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (2017) 6051–6063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yue Y, Liu J, He C, RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation, Genes Dev. 29 (2015) 1343–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.262766.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cao G, Li H-B, Yin Z, Flavell RA, Recent advances in dynamic m 6 A RNA modification, Open Biol. 6 (2016) 160003. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wu B, Li L, Huang Y, Ma J, Min J, Readers, writers and erasers of N6-methylated adenosine modification, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 47 (2017) 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Roignant JY, Soller M, m6A in mRNA: An Ancient Mechanism for Fine-Tuning Gene Expression, Trends Genet. 33 (2017) 380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR, The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15 (2014) 313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR, The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control, 15 (2014) 313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]