Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are contaminants of critical concern due to their persistence, widespread distribution in the environment, and potential human-health impacts. In this work, published studies of PFAS concentrations in soils were compiled from the literature. These data were combined with results obtained from a large curated database of PFAS soil concentrations for contaminated sites. In aggregate, the compiled data set comprises more than 30,000 samples collected from more than 2,500 sites distributed throughout the world. Data were collected for three types of sites— background sites, primary-source sites (fire-training areas, manufacturing plants), and secondary-source sites (biosolids application, irrigation water use). The aggregated soil-survey reports comprise samples collected from all continents, and from a large variety of locations in both urban and rural regions. PFAS were present in soil at almost every site tested. Low but measurable concentrations were observed even in remote regions far from potential PFOS sources. Concentrations reported for PFAS-contaminated sites were generally orders-of-magnitude greater than background levels, particularly for PFOS. Maximum reported PFOS concentrations ranged upwards of several hundred mg/kg. Analysis of depth profiles indicates significant retention of PFAS in the vadose zone over decadal timeframes and the occurrence of leaching to groundwater. It is noteworthy that soil concentrations reported for PFAS at contaminated sites are often orders-of-magnitude higher than typical groundwater concentrations. The results of this study demonstrate that PFAS are present in soils across the globe, and indicate that soil is a significant reservoir for PFAS. A critical question of concern is the long-term migration potential to surface water, groundwater, and the atmosphere. This warrants increased focus on the transport and fate behavior of PFAS in soil and the vadose zone, in regards to both research and site investigations.

Keywords: PFOS, PFOA, AFFF, sources

1. Introduction

It has become evident that PFAS are ubiquitous in environmental media in the U.S. and many other nations (e.g., Prevedouros et al., 2006; Rayne and Forest, 2009; Ahrens, 2011; Krafft and Riess, 2015). Their widespread distribution coupled with their persistence and potential human-health impacts have fomented interest in PFAS transport and fate in the environment, an accurate understanding of which is critical to robust risk assessments and effective mitigation efforts. The transport and fate of PFAS in the environment is being investigated at multiple scales, from that of individual contaminated sites to global surveys. To date, research has focused primarily on occurrence and transport in the atmosphere, surface water, and groundwater. However, there are indications that soils serve as a significant reservoir and long-term source for PFAS, including locally, regionally, and globally.

The potential importance of soil as a global reservoir for PFAS was first quantified by Strynar et al. (2012), who measured the concentrations of 13 PFAS in samples of surface soil collected from 60 locations in 6 countries. The samples were collected from locations far from known PFAS-contamination sources including industries known to have used PFAS. PFAS occurrence was widespread across the sample locations. Strynar et al. estimated global soil loadings of 1860 and >7000 metric tons of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), respectively. Rankin et al. (2016) reported concentrations of 32 PFAS in surface soil samples collected from 62 locations across all continents. Quantifiable levels of more than one PFAS were present in all samples tested, including soils collected from remote locations. Washington et al. (2019) used the Rankin et al. data to calculate global soil loadings for 8 PFAS. The combined estimated load for all 8 PFAS ranged from 1500 to 9000 metric tons, with mean estimates of approximately 1000 metric tons for both PFOA and PFOS. These results indicate that soil has the potential to be a primary reservoir for PFAS. This is supported by the study reported by Liu et al. (2015), who employed a fugacity-based screening model to characterize regional-scale transport and distribution of PFOS in a coastal region of China. Soil was determined to be a major environmental reservoir for PFOS, contributing to >40% of the total mass.

Recent research focused on PFAS-contaminated sites has also indicated the importance of soil as a reservoir for PFAS. Anderson et al. (2016) evaluated PFAS concentrations in soils and other media for 100’s of samples collected from 40 sites across 10 military installations in the U.S. at which aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) had been used. The results demonstrated widespread presence in soil for the 19 PFAS tested. Anderson et al. (2019) reported a meta-analysis of PFAS soil-to-groundwater concentration ratios for samples collected from 324 AFFF source-zone sites across 56 military installations distributed throughout the continental U.S. The results demonstrated that soil is a significant reservoir for PFAS at these contaminated sites. The results of transport modeling conducted at individual contaminated sites also indicate that soils and the vadoze zone serve as a significant long-term source of PFAS (Shin et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2017).

The results summarized above clearly indicate the importance of soil and the vadose zone as a reservoir for PFAS. This mass can serve as a long-term contamination source to surface water, groundwater, the atmosphere, and biota. Considering the significance of this domain, it is critical to develop a more detailed understanding of the occurrence of PFAS in soil and the vadose zone. The objectives of the present study are three-fold. First, reported PFAS soil concentrations for locations with no known nearby PFAS contamination sources of any type are aggregated to determine typical background levels. Second, soils data are aggregated for PFAS contaminated sites as a function of source type. Third, the two data sets are compared to evaluate concentration differences between different types of sites. PFAS concentrations in surface soil are also compared to distributions in the vadose zone and to groundwater levels.

2. Materials and Methods

A literature search was conducted to identify published works reporting concentrations of PFAS in soil. Web of Science was a primary search tool employed. Google Scholar and Google were also used. In addition, cited references in all identified publications were examined for relevant works. Multiple search terms were used in various combinations, including “PFAS”, “Perfluor*”, “Polyfluor*”, “PFC”, “soil”, “vadose zone”, and “sediment”. All identified publications that included PFOS or PFOA as analytes were included in the analysis. Only 3 publications were excluded on this basis. The excluded publications were focused on precursor compounds only, which were not reported in many of the studies.

Information including the type of study, nature of the locations surveyed, the number of sampling locations, number of PFAS analyzed, ranges of total PFAS concentrations, and maximum reported concentrations for PFOA and PFOS were recorded. Almost all of the studies clearly specified that the data reported corresponded to soil samples collected from the top several centimeters of the ground surface. The very few studies that did not specifically state this information are presumed to also represent surface samples based on the context of the studies.

Sample processing and analysis methods varied somewhat across the studies. In addition, quantitative detection limits varied among the studies. Therefore, the data analysis was focused primarily on maximum reported concentrations. As noted below, the number of PFAS analyzed in each soil-survey study varied significantly. Hence, the present analysis will focus primarily on PFOS and PFOA.

In addition to the literature search, an analysis is conducted of the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database. This database comprises soil, vadose zone, and groundwater samples reported for hundreds of AFFF–impacted sites (i.e., source zones) across dozens of Air Force installations distributed throughout the continental U.S. To our knowledge, it is the largest database of its kind. Anderson et al. (2019) used this database to characterize soil-groundwater ratios for PFAS at these sites. However, they did not report specific PFAS concentrations, or examine depth-specific PFAS distributions. Hence, the present study employs this database to add new information and insight by reporting and evaluating actual soil concentrations for multiple PFAS. It also presents data sets for PFAS depth distributions in the vadose zone, notably comprising the deepest samples reported to date. This database is continually being supplemented with additional data sets, and as of 2019, the database comprises almost 25,000 soil and vadose-zone samples from 2,452 borehole sampling locations distributed across 1000 source zones (not counting non-detect samples). The sampling locations include (former) fire-training areas (FTA) as well as other sites where either episodic or incidental AFFF discharge occurred, including emergency response locations, AFFF holding ponds and lagoons and their outfalls, hangar-related AFFF storage tanks and pipelines, fire station testing and maintenance areas, and sites where biosolids from wastewater treatment plants were land applied.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Data

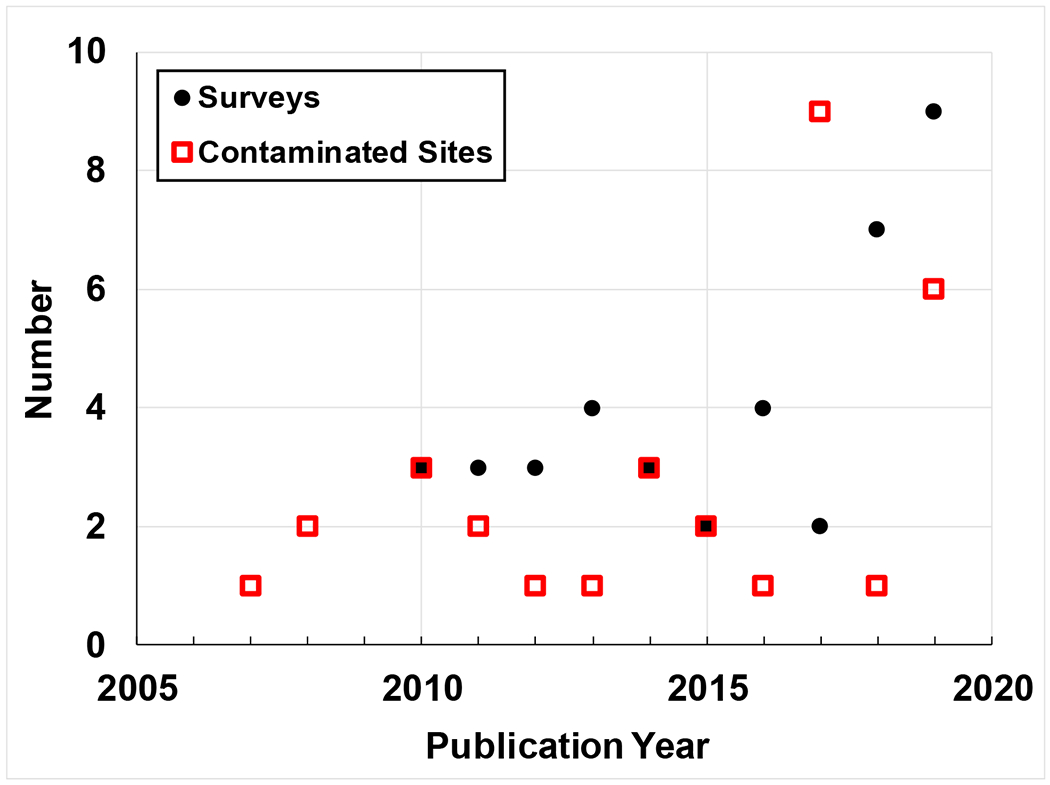

PFAS soil concentration data were obtained primarily from peer-reviewed journal articles. However, some data sets originated from various types of investigative reports. The numbers of studies reporting soil data are shown in Figure 1 as a function of year. A marked increase in the numbers of reports is observed for the past several years. Conversely, only three reports were published prior to 2010.

Figure 1.

Numbers of publications reporting PFAS concentrations in soil samples for surveys of background concentrations and contaminated sites. For some years the two types have identical numbers of publications, which shows as the filled circle residing within the open square.

Two types of studies were documented. One set can be classified as surveys of PFAS soil distributions for areas not directly impacted by PFAS sources. Specifically, the sampling sites for these studies are located in areas that do not have a known PFAS source in the immediate vicinity. These data are used to examine what will be referred to as “background” or ambient PFAS levels. A total of 40 background soil surveys were recorded, with three in effect repeated studies of the same area conducted by the same group. The second set of studies represent investigations conducted at a specific site or number of sites at which PFAS was manufactured, used, or disposed. These will be referred to as “contaminated” sites. A total of 32 reports were recorded for these types of sites.

3.2. Background Soil Concentrations

Relevant metadata for the soil surveys are reported in Table 1. In aggregate, the data comprise approximately 5700 soil samples collected from more than 1400 sampling locations across the world. The studies conducted by Strynar et al. (2012), which included 6 nations (U.S., China, Japan, Norway, Greece, and Mexico), and Rankin et al. (2016), which comprised 62 locations representing all continents (North America n=33, Europe n=10, Asia n=6, Africa n=5, Australia n=4, South America n=3 and Antarctica n=1), were large-scale surveys for which samples were collected from multiple nations across multiple continents. Of the 38 other studies, more than half (20) were conducted in China, showing that researchers there have been proactive in characterizing background levels of PFAS in soil. Six studies were conducted in Korea, 5 in the United States, and 4 in European nations.

Table 1.

PFAS concentrations in soil metadata collected from soil survey studies.

| Date | First author | Total PFAS Conca | Number of PFAS | Max PFOA Conc | Max PFOS Conc | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ug/kg | ug/kg | ug/kg | ||||

| 2010/2013 | Naile | 0.3 - 3.9 | 12 | 3.4 | 1.7 | Korea |

| 2010 | Li | 141 - 237 | 15 | 47.5 | 10.4 | China |

| 2010/2019 | Wang/Gao | 0.7 - 22 | 9 | 2 | 20 | China |

| 2011 | Pan | <0.3 - 9.4 | 9 | 0.5 | 2.4 | China |

| 2011 | Wang | 0.1 - 8.5 | 12 | 2.8 | 0.9 | China |

| 2011 | Wang | <0.1 - 1.7 | 12 | 0.5 | 0.7 | China |

| 2012 | Wang | 1.3 - 11 | 12 | 0.9 | 9.4 | China |

| 2012 | Strynar | <0.5 - 150 | 13 | 32 | 10 | Multiple |

| 2012 | Llorca | <0.1 - 5.8 | 18 | 1.5 | 5.4 | Tierra Del Fuego & Antarctica |

| 2013 | Wang | <0.1 - 1.8 | 22 | 0.3 | 0.4 | China |

| 2013 | Meng | <0.1 - 4.1 | 16 | 0.2 | 0.2 | China |

| 2014 | Kim | <0.05 - 1.6 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | Korea |

| 2014 | Tan | <0.1 - 1.8 | 16 | 0.3 | 0.1 | Nepal |

| 2015 | Xiao | 6 - 135 | 2 | 28 | 126 | United States |

| 2014/2015 | Shan/Jin | 0.7 - 28.8 | 11 | 9 | 0.3 | China |

| 2015 | Meng | 0.04 - 3.6 | 13 | 2.3 | 1.9 | China |

| 2016 | Chen | 0.3 - 5 | 17 | 25 | 2 | China |

| 2016 | Rankin | 0.05 - 15 | 32 | 3.4 | 3.1 | Multiple |

| 2016 | NH DES | <0.5 - 71 | 12 | 33 | 59 | United States |

| 2016 | Zhang | 0.1 - 4 | 21 | 4.2 | 2.7 | China |

| 2017 | Choi | <0.05 - 3.6 | 2 | 1.8 | 2.7 | Korea |

| 2017 | Liu | 1.9 -126 | 12 | 123.6 | 2.7 | China |

| 2018 | Meng | 3 - 64 | 12 | 5 | 4.2 | China |

| 2018 | Scher | 1.3 - 30 | 7 | 3 | 12 | United States |

| 2018 | Kikuchi | <0.02 - 20 | 28 | 0.6 | 1.7 | Sweden |

| 2018 | HWG | <0.2 - 5.1 | 6 | 0.5 | 3.1 | United States |

| 2018 | NEA | 0.4 - 174 | 17 | 3.3 | 162 | Norway |

| 2018 | Dalahmeh | 1.7 - 7.9 | 26 | 0.9 | 3 | Uganda |

| 2018 | Wang | <0.001 - 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.003 | China |

| 2019 | Zhu | 0.5 - 35 | 17 | 4.9 | 9.7 | United States |

| 2019 | Cao | 0.6 - 5.1 | 17 | 2.7 | 0.1 | China |

| 2019 | Groffen | 0.8 - 53 | 15 | 3.7 | 37 | Belgium |

| 2019 | Kim | 0.1 - 13.9 | 17 | 2.1 | 0.7 | Korea |

| 2019 | Li | NR - 64.7 | 21 | 16.6 | 2.8 | China |

| 2019 | Seo | 2.5 - 8.8 | 19 | 0.3 | 1 | Korea |

| 2019 | Skaar | <0.05 - 7.1 | 14 | 0.01 | 7.1 | Norway |

| 2019 | Zhang | 4.2 - 49 | 12 | 23 | 1.2 | China |

| Overall | <0.001 - 237 | |||||

| maximum | 123.6 | 162 | ||||

| minimum | 0.01 | 0.003 | ||||

| median | 2.7 | 2.7 |

Note: < means below quantitative detection limit

Reported by the original study authors

The number of PFAS analyzed ranged from 2 to 32, with a mean of 14. Total PFAS concentrations ranged from <0.001 to 237 μg/kg. PFOS and PFOA were the most prevalent PFAS reported for almost all of the studies. The maximum reported concentrations for PFOS ranged from 0.003 to 162 μg/kg, while they ranged from 0.01 to 124 μg/kg for PFOA. The maximum concentrations exceeded 10 μg/kg for only 8 and 7 of the studies for PFOA and PFOS, respectively. The median maximum concentrations were 2.7 μg/kg for both PFOS and PFOA (Table 1).

Soil samples across the studies were collected from a wide variety of location types in both urban and rural areas. These included residential yards and gardens, agricultural fields, schoolyards, commercial sites, and parks. Measurable levels of PFAS were reported for all of these types of sites. The widespread occurrence across a large variety of sites has potential significant implications with respect to human exposure. A number of the studies focused on assessing PFAS occurrence in agricultural fields, and the results show widespread presence. This raises potential concern regarding transfer of PFAS into the food web.

While the sampling locations for these studies are some distance from identified PFAS-contaminated sites, the vast majority are in populated regions. The study by Wang et al. (2018) is noteworthy as it consists of samples collected from 28 unpopulated forested sites located in mountainous regions of China. The sampling sites were located tens to several hundred km from industrial or municipal sources of PFOA and PFOS. Maximum reported PFOA and PFOS concentrations were 0.01 and 0.003 μg/kg, respectively. Rankin et al. (2016) reported PFAS soil concentrations for a single sampling site located in Antarctica. PFOA and PFOS concentrations were 0.05 and 0.007 μg/kg, respectively. The PFOS and PFOA concentrations reported for these two studies are significantly lower than concentrations reported for all of the other studies.

3.3. Contaminated Sites

An overview of the literature data for contaminated sites is presented in Tables 2 and 3. The data are separated into primary-source sites (Table 2) and secondary-source sites (Table 3). The former include PFAS manufacturing sites, FTAs and other AFFF-testing locations at airports and military installations, and a crash site. The secondary-source sites include sites that are adjacent to PFAS-contaminated primary-source sites, or sites for which PFAS-contaminated media were used for some purpose. These latter sites represent for example locations at which biosolids and other amendments were applied to the ground surface, and/or sites at which surface water, groundwater, or treated wastewater was used for irrigation.

Table 2.

PFAS concentrations in soil metadata for primary-source contaminated sites

| Date | First author | Type of Site | Max PFOA Conc | Max PFOS Conc | Locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ug/kg | ug/kg | ||||

| 2008 | SFT | FTA | 141 | 8,924 | 4 sites in Norway |

| 2010 | Wang | PFAS manufacturing | 50 | 2,583 | 1 site in China |

| 2011 | Karrman | FTA | 12 | 1,905 | 1 airport in Norway |

| 2012 | Martinsen | FTA | - | 17,400 | 4 airports in Norway |

| 2013/2014 | Houtz/McGuire | FTA | 11,484 | 36,534 | 1 AFB in U.S. |

| 2014 | Bergstrom | FTA | 2 | 486 | 3 FTAs in Sweden |

| 2014/2015 | Shan/Jin | PFAS industrial park | 5.3 | 0.4 | 1 site in China |

| 2015 | Filipovic | FTA | 219 | 8,520 | 1 AFB in Sweden |

| 2016 | Anderson | AFFF Source Zones | 58 | 9,700 | 10 military installations in the U.S. |

| 2017 | Baduel | FTA | 40 | 4,000 | 1 site in Australia |

| 2017 | Mejia-Avendaño | Crash site | 29 | 9.3 | 1 site in Canada |

| 2017 | CRCCARE | FTA | 3,200 | 460,000 | unspecified number of sites in Australia |

| 2017/2019 | Hale/Hoisaeter | FTA | 75 | 3,000 | 1 airport in Norway |

| 2017-2019 | ASA | Airport | 6,400 | 84,200 | 6 airports in Australia |

| 2018 | Casson | FTA | 90 | 10,000 | 1 site in Australia |

| 2019 | Braunig | FTA | 55 | 13,400 | 2 airports in Australia |

| 2019 | Dauchy | FTA | 514 | 55,197 | 1 site not specified |

| 2019 | Groffen | PFAS manufacturing | 114 | 7,800 | 1 site in Belgium |

| 2019 | Skaar | FTA | - | 1,055 | 1 airport in Norway |

| 2019 | This study | AFFF Source Zones | 50,000 | 373,000 | many military installations in the U.S. |

| Overall | median | 83 | 8,722 |

FTA = fire training area

Table 3.

PFAS concentrations in soil metadata for secondary-source contaminated sites

| Date | First author | Location | Max PFOA Conc | Max PFOS Conc | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ug/kg | ug/kg | ||||

| 2007/2019 | Davis/Zhu | U.S. | 470 | - | adjacent to PFAS manufacturing plant |

| 2008 | Wilhelm | Germany | 910 | 5,500 | land application of industrial-waste derived amendment |

| 2010 | Wang | China | 34 | 189 | adjacent to PFAS manufacuring plant |

| 2010 | Washington | U.S. | 2,531 | 1,409 | land application of PFAS industrial waste-impacted municipal biosolids |

| 2011 | Sepulvado | U.S. | 38 | 483 | land application of municipal biosolids |

| 2017 | Gottschall | Canada | 0.8 | 0.4 | land application of municipal biosolids |

| 2017 | MEDEP | U.S. | 23.6 | 878 | land application of paper-mill residuals and municipal biosolids |

| 2017 | Braunig | Australia | 7 | 1,692 | use of contaminated groundwater for irrigation |

| 2017 | Liu | China | 623 | 7 | use of contaminated surface water for irrigation |

| Overall | median | 38 | 680.5 |

Data were reported for a total of more than 42 primary-source sites across the 22 literature studies. Incorporating the current data from the U.S. Air Force database brings the total number of sites to greater than 1000. PFOS was the predominant PFAS reported for almost all of the sites. This is to be expected given that the vast majority of sites are FTAs or other sites of AFFF use. Maximum reported concentrations for PFOS range from 0.4 to 460,000 μg/kg, with a median value of 8,722 μg/kg. The maximum reported concentrations for PFOA range from 2 to >50,000 μg/kg, with a median value of 83 μg/kg (Table 2).

Additional information for surface-soil concentrations retrieved from the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database is presented in Table 4 for 10 selected PFAS. Note that non-detects were excluded from the analysis. PFOS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), PFOA, and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) were the four with the greatest number of detections. PFOS is present at the highest concentrations overall, with maximum, mean, and median concentrations of 373,000, 22, and 18 μg/kg, respectively. 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonic acid (6:2 FTSA) has the second highest maximum, mean, and median concentrations. PFHxS and perfluorooctanesulfonamide (PFOSA) also exhibit relatively large maximum, mean, and median concentrations. While PFOA had the second highest recorded maximum concentration (50,000 μg/kg), it has lower median and mean concentrations. The median concentrations for all 10 PFAS are close to or exceed 1 μg/kg. It is anticipated that these metadata are likely to be representative of many AFFF-impacted sites given the large number of sampled locations comprising the database.

Table 4.

Surface-soil concentration metrics for select PFAS retrieved from the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database. All values are reported in μg/kg. See footnote for PFAS descriptions. Sampling interval depth ranges from 6 to 30 cm from surface.

| Metric | PFBA | PFHxA | PFOA | PFDA | PFBS | PFHxS | PFOS | PFDS | PFOSA | 6:2 FTSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0.1-820 | 0.07-15300 | 0.07-50000 | 0.03-430 | 0.05-5550 | 0.07-21000 | 0.09-373000 | 0.05-640 | 0.09-20000 | 0.2-68000 |

| Median | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 18 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.8 |

| Geometric Mean | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 22 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 6.5 |

| Number of Samples | 877 | 1690 | 2469 | 1100 | 927 | 2649 | 3450 | 573 | 635 | 632 |

PFBA=perfluorobutanoic acid; PFHxA=perfluorohexanoic acid; PFOA=perfluorooctanoic acid; PFDA=perfluorodecanoic acid; PFBS=perfluorobutanesulfonic acid; PFHxS=perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFOS=perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; PFDS=perfluorodecanesulfonic acid; PFOSA=perfluorooctanesulfonamide; 6:2 FTSA= 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonic acid

The secondary-source sites comprise 9 sites from 10 studies (Table 3). Maximum reported concentrations for PFOS range from 0.4 to 5,500 μg/kg, with a median value of 680 μg/kg. The maximum reported concentrations for PFOA range from 0.8 to 2,531 μg/kg, with a median value of 38 μg/kg. As discussed by some of the original-study authors, these data sets demonstrate that the use of PFAS-contaminated media such as biosolids and irrigation water can result in soil contamination, subsequent distribution to other media, and ultimately the potential for human exposure at locations far removed from the original PFAS source (Lindstrom et al., 2011; Braunig et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017).

Comparison of the median maximum concentrations reported for PFOS and PFOA reveals a distinct stratification among the three types of locations--- background sites (Table 1) vs. secondary-source sites (Table 3) vs. primary-source sites (Table 2). The median maximum background levels are 2.7 μg/kg for both PFOS and PFOA, as noted above. The median max PFOS concentration of 680 μg/kg for the secondary-source sites is more than 2 orders-of-magnitude higher than the background level for PFOS, whereas the median max PFOS concentration of 8722 μg/kg for the primary-source sites is 3.5 orders-of-magnitude higher than background. The median max PFOA concentrations for the secondary- and primary-source sites for PFOA are approximately 1 and 1.5 orders-of-magnitude higher, respectively, than the background level.

One point of interest is the relative ranges of soil versus groundwater concentrations reported for PFAS. Anderson et al. (2019) reported metadata specifically on this topic based on the database of AFFF-impacted sites at U.S. Air Force Bases. Ratios of soil-to-groundwater (Soil-GW) concentrations were reported for all tabulated PFAS for all assessed sampling sites. The aggregate Soil-GW ratio was observed to vary over 9 orders of magnitude, with log-transformed values ranging from approximately −2 to 7. Approximately 13% of the Soil-GW ratios were negative, reflecting soil concentrations that were lower than the corresponding groundwater concentrations. Conversely, the ratios were positive for the vast majority (87%) of data, reflecting greater soil concentrations. The peak log-transformed ratio was approximately 2, reflecting soil concentrations ~100-times greater than groundwater.

Several studies reported in Table 2 included both soil and groundwater concentrations for the contaminated sites. The aggregate log-transformed S-GW ratios for PFOS and PFOA are 2.5 and 2.1, respectively. Thus, the results are consistent with the analysis reported by Anderson et al. (2019). The overall results demonstrate that PFAS concentrations in soils at contaminated sites are typically orders-of-magnitude higher than groundwater concentrations.

3.4. Vadose-Zone Concentrations and Depth Profiles

Only 15 published studies (for 12 sites) reported depth profiles of PFAS concentrations. Seven of them reported deep profiles (>4 meters), and the remainder focused on shallow profiles (<1-2 meters). Davis et al. (2007) and Shin et al. (2011) reported concentrations down to ~5 meters. The deepest profiles were reported by Dauchy et al. (2019), which extended to 15 meters below ground surface. In many cases, the concentrations are observed to decrease by several orders-of-magnitude with depth.

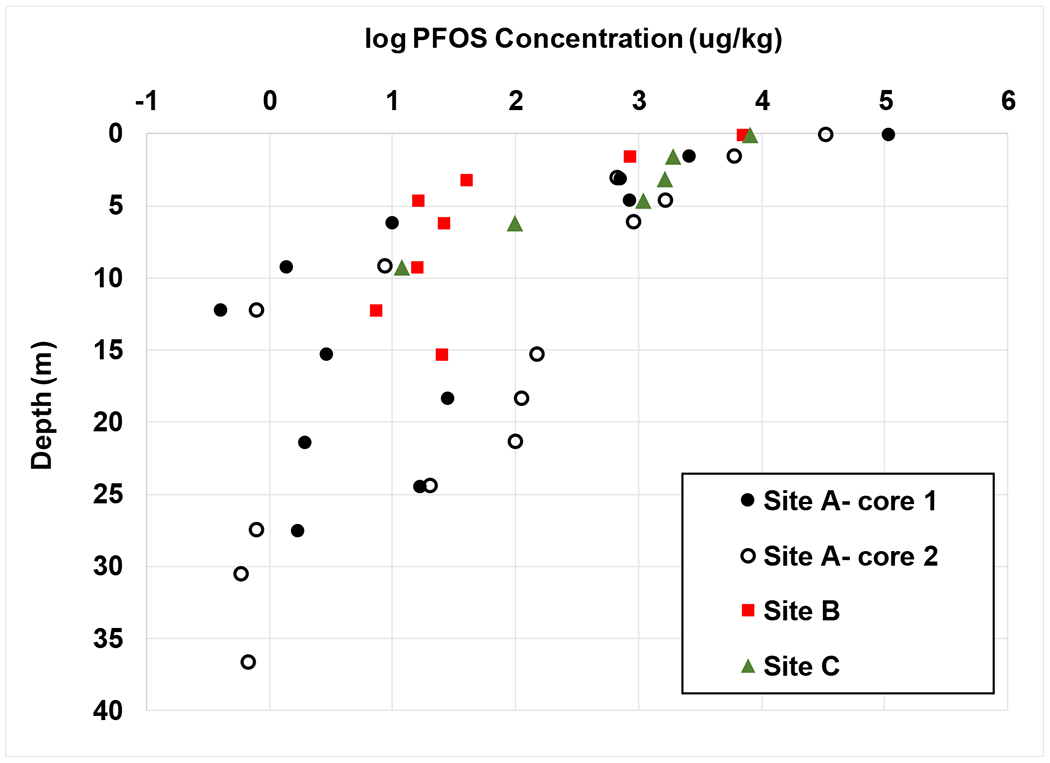

Example depth profiles for PFOS soil concentrations developed from data reported in the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database are presented in Figure 2. Data for Site A are recorded to a depth of 37 m below ground surface. These data represent to our knowledge the deepest reported soil-concentration depth profiles for PFAS in a vadose zone. Inspection of Figure 2 shows that PFOS concentrations decrease by several orders-of-magnitude with depth. Aggregate data for total PFAS reported in the database for a large number of borehole samples also exhibit exponential decreases with depth (Figure 3). These results are consistent with data typically reported for shallower profiles in the prior studies referenced in the preceding paragraph.

Figure 2.

Example depth profiles of PFOS soil concentrations developed using data from the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database.

Figure 3.

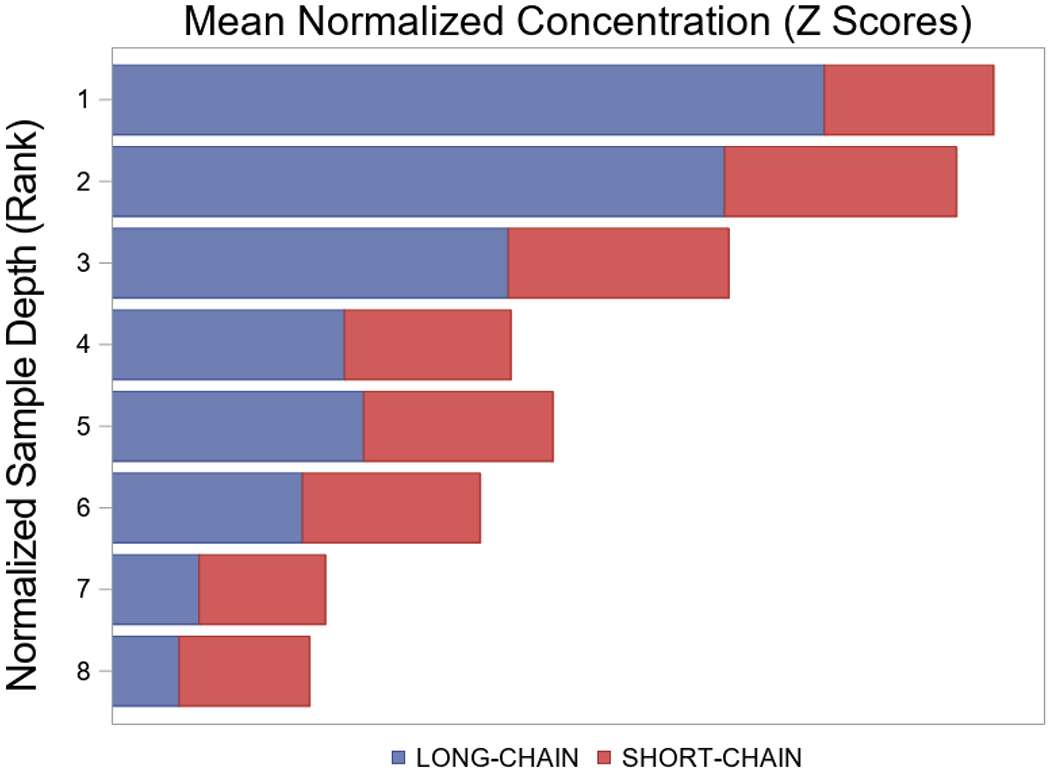

Depth distribution of total PFAS in soil as a function of chain length. The data represent 124 boreholes across 30 sites for which at least 8 depth-discrete samples were collected, tracked in the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database. Since the actual sample depths differed from location to location, depths were normalized by sequential rank, and generally reflect the interval from the ground surface to the water table. Similarly, total PFAS concentrations were normalized by the computation of standard normal (Z) scores for each borehole, and are summarized as the mean among all boreholes for short- and long-chain PFAS, respectively. Long-chain (≥C7) and short-chain are used as defined in Buck et al. (2011).

Aggregate concentration metrics retrieved from the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database are presented in Table 5 for subsurface soil concentrations of 10 PFAS. Comparison of these data to the results reported in Table 4 for surface soil reveals that the maximum concentrations are higher for the surface samples for all 10 PFAS. Conversely, geometric mean concentrations are higher for surface samples for some PFAS but not for others. The ratio of geomean concentrations for surface samples versus subsurface samples is reported in Table 5 for the 10 PFAS. It is observed that the ratios are >1 for the longer-chain PFAS and <1 for the shorter-chain PFAS. The only exception is perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA), for which the ratio is >1.

Table 5.

Subsurface-soil concentration metrics for select PFAS retrieved from the U.S. Air Force AFFF Impacted-Site database. All values are reported in μg/kg. See footnote for PFAS descriptions. Samples include all data excluding the data presented in Table 4.

| Metric | PFBA | PFHxA | PFOA | PFDA | PFBS | PFHxS | PFOS | PFDS | PFOSA | 6:2 FTSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0.07-170 | 0.07-2700 | 0.05-7220 | 0.0005-285 | 0.05-940 | 0.06-15300 | 0.1-160000 | 0.05-110 | 0.07-2500 | 0.2-21000 |

| Median | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 10 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| Geometric Mean | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 12 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 5.4 |

| Number of Samples | 947 | 1934 | 2881 | 360 | 1619 | 3825 | 4259 | 184 | 406 | 854 |

| Surface/Subsurface Geomeansa | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

ratio of geometric means for surface samples vs subsurface samples

PFBA=perfluorobutanoic acid; PFHxA=perfluorohexanoic acid; PFOA=perfluorooctanoic acid; PFDA=perfluorodecanoic acid; PFBS=perfluorobutanesulfonic acid; PFHxS=perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFOS=perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; PFDS=perfluorodecanesulfonic acid; PFOSA=perfluorooctanesulfonamide; 6:2 FTSA= 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonic acid

The difference in PFAS depth distribution as a function of chain length noted in Table 5 is observed for combined PFAS, as shown in Figure 3. Long-chain PFAS, ≥C7 (Buck et al. 2011), represent the majority of PFAS mass at the shallowest depths, whereas short-chain PFAS comprise the majority at deeper depths. Similar behavior has been reported in prior field studies (Washington et al., 2010; Sepulvado et al., 2011; Baduel et al., 2017; Casson & Chiang, 2018; Dauchy et al., 2019). For example, Washington et al. (2010) reported that the ratio of PFAS concentrations at ~1.5 meters to those at ~0.5 meter decreased with increasing chain length for all of the sample locations evaluated in their study. Baduel et al. (2017) reported that the maximum concentrations of the majority of longer-chain PFAS were in the top 1 meter, while most of the maximum concentrations of shorter-chain PFAS were at a depth of 2 meters or greater for their study site.

The migration and leaching behavior of PFAS in the vadose zone is expected to depend on a variety of factors including PFAS source properties (PFAS type, source input conditions, co-contaminants), soil properties, meteorological conditions, and other factors (Brusseau, 2018; Lyu et al., 2018; Brusseau et al., 2019a, 2019b; Guo et al., 2020). The majority of depth-profile data sets show high concentrations present at shallow depths and exponential decreases at greater depths. This distribution indicates significant retention of PFAS in the vadose zone over decadal timeframes. Several factors may influence the retention of PFAS in the vadose zone. One factor that can lead to enhanced retention compared to groundwater systems is adsorption of PFAS at air-water interfaces under water-unsaturated conditions (Brusseau, 2018, 2019, 2020; Lyu et al., 2018; Brusseau et al., 2019a; Guo et al., 2020). In addition, adsorption by the solid phase is always a contributing factor to some degree, with its impact mediated by geochemical properties of the geomedia and physicochemical properties of the PFAS (e.g., Higgins and Luthy, 2006; Anderson et al., 2016; Brusseau, 2019). Furthermore, adsorption by soil may be more important for nonioinc, cationic, and zwitterionic PFAS compared to the anionics (e.g., Xiao et al., 2019). Another factor of potential great importance for soil sources is the presence of precursor compounds, whose degradation can produce more recalcitrant PFAS and thus add to their mass fraction (e.g., Houtz et al., 2013; Anderson et al., 2016).

4. Conclusions

Soil PFAS concentration data were aggregated from the literature. The compiled data comprise samples collected from all continents, and from a large variety of locations in both urban and rural regions. PFAS were present in soil at almost every location tested. Low but measurable concentrations were observed even in remote regions far from potential PFOS sources. These observations have potential implications for human exposure through multiple routes. Given the level of PFAS production and use in Europe and the U.S., it would seem prudent to implement additional soil surveys in those regions. It would also be prudent to initiate surveys in other industrialized regions for which there are minimal data reported to date (e.g., regions of Asia and Africa). Additional surveys of remote areas are needed to supplement characterization of background levels of PFAS. PFOS and PFOA were typically the predominant PFAS of those measured. This observation may in part be influenced by the focus of many studies on a select few PFAS, often the legacy anionic compounds. Recent research has indicated the presence in the environment of numerous other PFAS comprising different molecular structures (e.g., Baduel et al., 2017; Xiao, 2017; Xiao et al., 2017). As such, future soil sampling studies should attempt to include a wider cross-section of PFAS.

Soil concentrations reported for PFAS-contaminated sites are generally orders-of-magnitude greater than background levels. Maximum reported PFOS concentrations ranged upwards of several hundred mg/kg. PFAS depth profiles generally show relatively high concentrations present at shallow depths and exponential decreases at greater depths. This distribution indicates significant retention of PFAS in the vadose zone over decadal timeframes. However, it is clear that PFAS have migrated to significant depths and that groundwater at most of these sites is contaminated with PFAS. This demonstrates that some degree of leaching has occurred at these sites. Greater understanding is needed of the migration behavior of PFAS in the vadose zone under different site conditions, including the potential impacts of factors such as source conditions, the presence of precursor compounds, physical and geochemical heterogeneity, and climatic conditions. Detailed site investigations will be critical to understand and predict the transport and fate behavior of PFAS in the vadose zone.

It is noteworthy that soil concentrations reported for PFAS at contaminated sites are often orders-of-magnitude higher than typical groundwater concentrations, ranging up to parts-per-million levels. Thus, research studies, site investigations, and modeling efforts characterizing PFAS transport in soil and the vadose zone need to be implemented with this in mind. The concentrations encountered at any given site will of course depend upon the nature of the PFAS source, the timeframe of contamination, site conditions, and many other site-specific factors.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate that PFAS are present in soils across the globe, and indicate that soil is a significant reservoir for PFAS. A critical question of concern is the long-term migration potential to surface water, groundwater, and the atmosphere. This warrants increased focus on the transport and fate behavior of PFAS in soil and the vadose zone, in regards to both research and site investigations.

Acknowledgements.

The research was support in part by funding from the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (P42 ES04940). B. Guo would like to acknowledge support from the Water, Environment, and Energy Solutions (WEES) program at the University of Arizona. We thank the reviewers for their constructive comments.

References

- Ahrens L, 2011. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the aquatic environment: a review of their occurrence and fate. J. Environ. Monit 13, 20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RH, Long G, Cornell, Porter, Ronald C, & Anderson, Janet K. (2016). Occurrence of select perfluoroalkyl substances at U.S. Air Force aqueous film-forming foam release sites other than fire-training areas: Field-validation of critical fate and transport properties. Chemosphere, 150, 678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RH, Adamson DT, Stroo HF, 2019. Partitioning of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances from soil to groundwater within aqueous film-forming foam source zones. J. Contam. Hydrol 220, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASA (Air Services Australia) (2017-2019). National PFAS Management Program. Site Investigations. http://www.airservicesaustralia.com/environment/national-pfas-management-program/

- Baduel C, Mueller J, Rotander A, Corfield J, & Gomez-Ramos M (2017). Discovery of novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) at a fire fighting training ground and preliminary investigation of their fate and mobility. Chemosphere, 185, 1030–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom S (2014). Transport of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in soil and groundwater in Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Bräunig J, Baduel C, Heffernan A, Rotander A, Donaldson E, & Mueller J (2017). Fate and redistribution of perfluoroalkyl acids through AFFF-impacted groundwater. Science of the Total Environment, 596-597, 360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräunig J, Baduel C, Barnes C, & Mueller J (2019). Leaching and bioavailability of selected perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) from soil contaminated by firefighting activities. Science of the Total Environment, 646, 471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, Jensen AA, Kannan K, Mabury SA, & van Leeuwen SP (2011). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 7(4), 513–541. 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau ML (2018). Assessing the potential contributions of additional retention processes to PFAS retardation in the subsurface. Sci. Total Environ 613-614, 176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau ML (2019). Estimating the relative magnitudes of adsorption to solid-water and air/oil-water interfaces for per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. Environmental Pollution, 254, article 113102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau ML (2020). Simulating PFAS transport influenced by rate-limited multi-process retention. Water research, 168, article115179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau ML, Yan N, Van Glubt S, Wang Y, Chen W, Lyu Y, Dungan B, Carroll KC, Holguin FO (2019a). Comprehensive retention model for PFAS transport in subsurface systems. Water Res. 148, 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau ML, Khan N, Wang Y, Yan N, Van Glubt S, Carroll KC, (2019b). Nonideal transport and extended elution tailing of PFOS in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol 53, 10654e10664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Wang C, Lu Y, Zhang M, Khan K, Song S, Wang P, & Wang C (2019). Occurrence, sources and health risk of polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in soil, water and sediment from a drinking water source area. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 174, 208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson R, & Chiang S (2018). Integrating total oxidizable precursor assay data to evaluate fate and transport of PFASs. Remediation Journal, 28(2), 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Jiao X-C, Gai N, Li X-J, Wang X-C, Lu G-H, Piao H-T, Rao Z & Yang Y-L (2016). Perfluorinated compounds in soil, surface water, and groundwater from rural areas in eastern China. Environmental Pollution, 211, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi G-H, Lee D-Y, Jeong D-K, Kuppusamy S, Lee YB, Park B-J, & Kim J-H (2017). Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) concentrations in the South Korean agricultural environment: A national survey. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 16(8), 1841–1851. [Google Scholar]

- CRCCARE 2017). Assessment, Management and Remediation for PFOS and PFOA Part 1:Background. Technical Report No. 38 CRC for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment, Newcastle, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Dalahmeh S, Tirgani S, Komakech A, Niwagaba C, & Ahrens L (2018). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water, soil and plants in wetlands and agricultural areas in Kampala, Uganda. Science of the Total Environment, 631-632, 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy X, Boiteux V, Colin A, Hémard J, Bach C, Rosin C, & Munoz J (2019). Deep seepage of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances through the soil of a firefighter training site and subsequent groundwater contamination. Chemosphere, 214, 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Aucoin M, Larsen B, Kaiser M, & Hartten A (2007). Transport of ammonium perfluorooctanoate in environmental media near a fluoropolymer manufacturing facility. Chemosphere, 67(10), 2011–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic M, Woldegiorgis A, Norström K, Bibi M, Lindberg M, & Österås A (2015). Historical usage of aqueous film forming foam: A case study of the widespread distribution of perfluoroalkyl acids from a military airport to groundwater, lakes, soils and fish. Chemosphere, 129, 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Liang Y, Gao K, Wang Y, Wang C, Fu J, Wang Y, Jiang G, & Jiang Y (2019). Levels, spatial distribution and isomer profiles of perfluoroalkyl acids in soil, groundwater and tap water around a manufactory in China. Chemosphere, 227, 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschall N, Topp E, Edwards M, Payne M, Kleywegt S & Lapen DR (2017). Brominated flame retardants and perfluoroalkyl acids in groundwater, tile drainage, soil, and crop grain following a high application of municipal biosolids to a field. Science of the Total Environment, 574, 1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groffen T, Eens M, & Bervoets L (2019). Do concentrations of perfluoroalkylated acids (PFAAs) in isopods reflect concentrations in soil and songbirds? A study using a distance gradient from a fluorochemical plant. Science of the Total Environment, 657, 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Zeng J, & Brusseau ML (2020). A mathematical model for the release, transport, and retention of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the vadose zone. Water Resources Research, 56 (2), e2019WR026667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale SE, Arp HPH, Slinde GA, Wade EJ, Bjørseth K, Breedveld GD, Straith BF, Moe KG, Jartun M, & Høisæter A (2017). Sorbent amendment as a remediation strategy to reduce PFAS mobility and leaching in a contaminated sandy soil from a Norwegian firefighting training facility. Chemosphere, 171, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CP & Luthy RG Sorption of perfluorinated surfactants on sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol 2006, 40, 7251–7256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høisæter A, Pfaff A, & Breedveld G (2019). Leaching and transport of PFAS from aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) in the unsaturated soil at a firefighting training facility under cold climatic conditions. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 222, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtz E, Higgins CP, Field JA, & Sedlak DL (2013). Persistence of perfluoroalkyl acid precursors in AFFF-impacted groundwater and soil. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(15), 8187–8195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HWG (Horsley Witten Group, Inc.) (2018). Immediate Response Action Plan Status Report 3, Barnstable Municipal Airport Hyannis, Massachusetts; RTN 4-26347, April 2018.

- Jin H, Zhang Y, Zhu L, & Martin J (2015). Isomer profiles of perfluoroalkyl substances in water and soil surrounding a chinese fluorochemical manufacturing park. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(8), 4946–4954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrman Anna, Elgh-Dalgren Kristin, Lafossas C, & Moskeland T (2011). Environmental levels and distribution of structural isomers of perfluoroalkyl acids after aqueous fire-fighting foam (AFFF) contamination. Environmental Chemistry, 8(4), 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi J, Wiberg K, Stendahl J, & Ahrens L (2018). Analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in soil from Swedish background sites. Rapport till Naturvårdsverket Överenskommelse NV-2219-17-003 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/edf9/bdb40780c32cebfa431cbb9c09eee3575702.pdf

- Kim Eun Jung, Park Yu-Mi, Park Jong-Eun, & Kim Jong-Guk. (2014). Distributions of new Stockholm Convention POPs in soils across South Korea. Science of the Total Environment, 476-477, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Ekpe OD, Lee J-H, Kim D-H, & Oh J-E (2019). Field-scale evaluation of the uptake of Perfluoroalkyl substances from soil by rice in paddy fields in South Korea. Science of the Total Environment, 671, 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafft MP, Riess JG, 2015. Per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS): environmental challenges. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci 20, 192–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom A, Strynar M, Delinsky A, Nakayama S, Delinsky AD, McMillan L, Libelo EL, Neill M, & Thomas L (2011). Application of WWTP biosolids and resulting perfluorinated compound contamination of surface and well water in Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(19), 8015–8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zhang C, Qu Y, Chen J, Chen L, Liu Y, & Zhou Q (2010). Quantitative characterization of short- and long-chain perfluorinated acids in solid matrices in Shanghai, China. Science of the Total Environment, 408(3), 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Oyang X, Zhao Y, Tu T, Tian X, Li L, Zhao Y, Li Y & Xiao Z (2019). Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds in agricultural environment, vegetables, and fruits in regions influenced by a fluorine-chemical industrial park in China. Chemosphere, 225, 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Lu Y, Xie S, Wang T, Jones K, & Sweetman A (2015). Exploring the fate, transport and risk of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in a coastal region of China using a multimedia model. Environment International, 85, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Lu Y, Shi Y, Wang P, Jones K, Sweetman AJ, Johnson AC, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Lu X, Su C, Sarvajayakesavaluc S & Khan K (2017). Crop bioaccumulation and human exposure of perfluoroalkyl acids through multi-media transport from a mega fluorochemical industrial park, China. Environment International, 106, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca M, Farré M, Tavano M, Alonso B, Koremblit G, & Barceló D (2012). Fate of a broad spectrum of perfluorinated compounds in soils and biota from Tierra del Fuego and Antarctica. Environmental Pollution , 163, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y, Brusseau ML, Chen W, Yan N, Fu X, Lin X, 2018. Adsorption of PFOA at the air-water interface during transport in unsaturated porous media. Environ. Sci. Technol 52, 7745–7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen K (2012). Polyfluorinated compounds at fire training facilities: Assessing Contaminated soil at 43 Norwegian airports. Presented at the Section for Waste Treatment and Contaminated Ground Common Forum Meeting, Bilbao, 23.10.12. https://www.emergingcontaminants.eu/application/files/8214/5217/1295/05_PresentationF_cpds_at_No_airports_Martinsen.pdf [Google Scholar]

- MEDEP (Maine Department of Environmental Protection) (2017). Stone Farm, Arundel Sample Collection - Data Report Summary; Report Date: June 15, 2017 https://kkw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/DEP-Phase-2-study.pdf

- McGuire ME, Schaefer C, Richards T, Backe WJ, Field JA, Houtz E, Sedlak DL, Guelfo JL, Wunsch A, & Higgins CP (2014). Evidence of remediation-induced alteration of subsurface poly- and perfluoroalkyl substance distribution at a former firefighter training area. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(12), 6644–6652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia-Avendaño S, Munoz G, Vo Duy S, Desrosiers M, Benoı TP, Sauvé S, & Liu J (2017). Novel fluoroalkylated surfactants in soils following firefighting foam deployment during the Lac-Mégantic railway accident. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(15), 8313–8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Wang T, Wang P, Giesy JP, & Lu Y (2013). Perfluorinated compounds and organochlorine pesticides in soils around Huaihe River: A heavily contaminated watershed in Central China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 20(6), 3965–3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Wang T, Wang P, Zhang Y, Li Q, Lu Y, & Giesy JP (2015). Are levels of perfluoroalkyl substances in soil related to urbanization in rapidly developing coastal areas in North China? Environmental Pollution, 199, 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Wang T, Song S, Wang P, Li Q, Zhou Y, & Lu Y (2018). Tracing perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in soils along the urbanizing coastal area of Bohai and Yellow Seas, China. Environmental Pollution, 238, 404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naile JE, Khim JS, Wang T, Chen C, Luo W, Kwon B-O, Park J, Koh C-H, Jones PD, Lu Y, & Giesy JP (2010). Perfluorinated compounds in water, sediment, soil and biota from estuarine and coastal areas of Korea. Environmental Pollution, 158(5), 1237–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naile JE, Khim JS, Hong S, Park J, Kwon B-O, Ryu JS, Hwang JH, Jones PD, & Giesy J (2013). Distributions and bioconcentration characteristics of perfluorinated compounds in environmental samples collected from the west coast of Korea. Chemosphere, 90(2), 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEA (Norwegian Environment Agency) (2018). Environmental Pollutants in the Terrestrial and Urban Environment 2017, M-1076.

- NHDES (New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services) (2016). Investigation into the presence of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in New Hampshire. https://www.des.nh.gov/organization/commissioner/pfoa.htm

- Pan Y, Shi Y, Wang J, Jin X, & Cai Y (2011). Pilot Investigation of perfluorinated compounds in river water, sediment, soil and fish in Tianjin, China. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 87(2), 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevedouros K, Cousins IT, Buck RC, Korzeniowski SH, 2006. Sources, fate and transport of perfluorocarboxylates. Environ. Sci. Technol 40 (1), 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin K, Mabury S, Jenkins T, & Washington J (2016). A North American and global survey of perfluoroalkyl substances in surface soils: Distribution patterns and mode of occurrence. Chemosphere, 161, 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayne S, Forest K, 2009. Perfluoroalkyl sulfonic and carboxylic acids: a critical review of physicochemical properties, levels and patterns in waters and wastewaters, and treatment methods. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 44, 1145–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher D, Kelly J, Huset C, Barry K, Hoffbeck R, Yingling V, & Messing R (2018). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in garden produce at homes with a history of PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Chemosphere, 196, 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S, Son M, Shin E, Choi S, & Chang Y (2019). Matrix-specific distribution and compositional profiles of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in multimedia environments. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 364, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulvado J, Blaine A, Hundal L, & Higgins C (2011). Occurrence and fate of perfluorochemicals in soil following the land application of municipal biosolids. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(19), 8106–8112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan G, Wei M, Zhu L, Liu Z, & Zhang Y (2014). Concentration profiles and spatial distribution of perfluoroalkyl substances in an industrial center with condensed fluorochemical facilities. Science of the Total Environment, 490, 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Vieira V, Ryan P, Detwiler R, Sanders B, Steenland K, & Bartell S (2011). Environmental fate and transport modeling for perfluorooctanoic acid emitted from the Washington Works Facility in West Virginia. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(4), 1435–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SFT, (2008). Screening of polyfluorinated organic compounds at four fire training facilities in Norway (TA-2444/2008). https://evalueringsportalen.no/evaluering/screening-of-polyfluorinated-organic-compounds-at-four-fire-training-facilities-in-norway/ta2444.pdf/@@inline

- Skaar J, Ræder S, Lyche E, Ahrens M, & Kallenborn J (2019). Elucidation of contamination sources for poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) on Svalbard (Norwegian Arctic). Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(8), 7356–7363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strynar M, Lindstrom A, Nakayama S, Egeghy P, & Helfant L (2012). Pilot scale application of a method for the analysis of perfluorinated compounds in surface soils. Chemosphere, 86(3), 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B, Wang T, Wang P, Luo W, Lu Y, Romesh K, & Giesy J (2014). Perfluoroalkyl substances in soils around the Nepali Koshi River: Levels, distribution, and mass balance. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 21(15), 9201–9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Wang T, Giesy J, & Lu Y (2013). Perfluorinated compounds in soils from Liaodong Bay with concentrated fluorine industry parks in China. Chemosphere, 91(6), 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhao Z, Ruan Y, Li J, Sun H, & Zhang G (2018). Occurrence and distribution of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in natural forest soils: A nationwide study in China. Science of the Total Environment, 645, 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Lu Y, Chen C, Naile J, Khim J, Park J, & Giesy J (2011). Perfluorinated compounds in estuarine and coastal areas of north Bohai Sea, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62(8), 1905–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Chen C, Naile J, Khim E, Giesy J, & Lu S (2011). Perfluorinated compounds in water, sediment and soil from Guanting Reservoir, China. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 87(1), 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Lu Y, Chen C, Naile J, Khim E, & Giesy J (2012). Perfluorinated compounds in a coastal industrial area of Tianjin, China. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 34(3), 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fu J, Wang T, Liang Y, Pan Y, Cai Y, & Jiang G (2010). Distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate and other perfluorochemicals in the ambient environment around a manufacturing facility in China. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(21), 8062–8067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington J, Yoo H, Ellington J, Jenkins T, & Libelo E (2010). Concentrations, distribution, and persistence of perfluoroalkylates in sludge-applied soils near Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(22), 8390–8396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington J, Rankin K, Libelo E, Lynch D, & Cyterski M (2019). Determining global background soil PFAS loads and the fluorotelomer-based polymer degradation rates that can account for these loads. Science of the Total Environment, 651(Pt 2), 2444–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Barber L, Leblanc D, Sunderland E, & Vecitis C (2017). Geochemical and hydrologic factors controlling subsurface transport of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(8), 4269–4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm M, Kraft M, Rauchfuss K, & Hölzer J (2008). Assessment and management of the first German case of a contamination with perfluorinated compounds (PFC) in the Region Sauerland, North Rhine-Westphalia. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 71(11-12), 725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, (2017). Emerging poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: a review of current literature. Water Research, 124, 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Simcik M, Halbach T, & Gulliver J (2015). Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in soils and groundwater of a U.S. metropolitan area: Migration and implications for human exposure. Water Research, 72, 64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Golovko SA, & Golovko MY (2017). Identification of novel non-ionic, cationic, zwitterionic, and anionic polyfluoroalkyl substances using UPLC–TOF–MSE high-resolution parent ion search. Analytica Chimica Acta, 988, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Jin B, Golovko SA, Golovko MY & Xing B (2019). Sorption and desorption mechanisms of cationic and zwitterionic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in natural soils: Thermodynamics and hysteresis. Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 11818–11827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tan D, Geng Y, Wang L, Peng Y, He Z, Xu Y, & Liu X (2016). Perfluorinated compounds in greenhouse and open agricultural producing areas of three provinces of China: Levels, sources and risk assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, article 1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Pan Z, Wu Y, Shang R, Zhou X, & Fan Y (2019). Distribution of perfluorinated compounds in surface water and soil in partial areas of Shandong Province, China. Soil and Sediment Contamination, 28(5), 502–512. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, & Kannan K (2019). Distribution and partitioning of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids in surface soil, plants, and earthworms at a contaminated site. Science of the Total Environment, 647, 954–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]