INTRODUCTION

Although clinical practice guidelines recommend against routine breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer screenings in older adults with less than 10-year life expectancy, a large proportion of these older adults continue to receive screening [1]. Consequently, growing efforts aim to reduce screening in this population. While prior studies have shown racial disparities in the receipt of cancer screening [2], whether the rates of over-screening, as defined by screening in those with limited life expectancy, differs among different racial groups is unknown. This information is important to target interventions to reduce over-screening and prevent unintended harms that may further exacerbate existing disparities. We aimed to describe the rates of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer screening by race and life expectancy in a nationally representative cohort of older adults.

METHODS

Using data from the first wave of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) in 2011 linked to Medicare claims, we constructed cohorts of older adults who were 65+ years old, continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare during the study period, and eligible for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer screening, respectively. Using the NHATS data, 10-year mortality risks were predicted from a validated index [3], which were then used to categorize participants as having < 10-year versus > 10-year median life expectancies. We used published algorithms to identify screening tests in Medicare claims data. For breast and prostate cancer screenings, we assessed rates of screening mammograms and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests, respectively, over a 2-year period (2011–2013). For colorectal cancer screening, we included screening colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood test through the end of our observation period (2011–2014). Due to the small number of participants in other racial categories, we focused our analysis comparing non-Hispanic blacks versus non-Hispanic whites. We examined cancer screening rates among blacks and whites by life expectancy categories. We then constructed logistic regression models to examine the association of race and life expectancy with the receipt of cancer screening while adjusting for age, geographic region, and sex (colorectal cancer screening only) and tested interaction between race and life expectancy category.

RESULTS

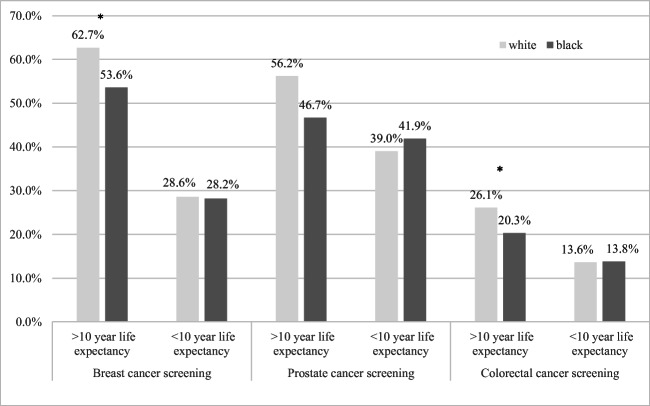

The analytic sample included 1905 women for breast cancer screening, 1195 men for prostate cancer screening, and 3509 older adults (2002 women, 1507 men) for colorectal cancer screening. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, among those with > 10-year life expectancy, we found significantly lower screening rates among blacks compared with whites for breast cancer screening (53.6% versus 62.7%, adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.64, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.45–0.90) and colorectal cancer screening (20.3% versus 26.1%, aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.92). However, in those with < 10-year life expectancy, the screening rates among the two racial groups were much more similar and no longer statistically different (breast cancer screening rates 28.2% versus 28.6%, aOR 0.85, 95% CI 0.57–1.27; colorectal cancer screening rates 13.8% versus 13.6%, aOR 0.91, 95% CI 0.59–1.40). Prostate cancer screening rates were not significantly different among whites and blacks overall or in either life expectancy subgroup. The interaction terms between race and life expectancy category were not statistically significant for any cancer screening (p = 0.274 for breast cancer, 0.129 for prostate cancer, and 0.300 for colorectal cancer).]-->

Table 1.

Odds ratios for receiving cancer screening among non-Hispanic blacks and whites, overall and stratified by predicted median life expectancy

| Cancer screening | Overall | > 10-year life expectancy† | < 10-year life expectancy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | N | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | N | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|

Breast Black |

423 | 0.66 (0.51, 0.86) | 0.002 | 207 | 0.64 (0.45, 0.90) | 0.01 | 216 | 0.85 (0.57, 1.27) | 0.42 |

| White | 1482 | Ref | 797 | Ref | 685 | Ref | |||

|

Prostate Black |

232 | 0.76 (0.50, 1.13) | 0.17 | 85 | 0.66 (0.36, 1.20) | 0.17 | 147 | 1.00 (0.62, 1.61) | 0.99 |

| White | 963 | Ref | 435 | Ref | 528 | Ref | |||

|

Colorectal Black |

714 | 0.75 (0.60, 0.93) | 0.01 | 299 | 0.71 (0.55, 0.92) | 0.01 | 415 | 0.91 (0.59, 1.40) | 0.66 |

| White | 2795 | Ref | 1357 | Ref | 1438 | Ref | |||

Models adjust for age, geographic region, and sex (colorectal cancer screening only). All analyses are weighted

†Using the mortality risk index developed by Cruz et al. [3], a median life expectancy of > 10 years is defined as a < 50% mortality risk over 10 years; a median life expectancy of < 10 years is defined as a > 50% mortality risk over 10 years

Figure 1.

Unadjusted screening rates for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers among non-Hispanic blacks and whites, stratified by predicted median life expectancy [3]. An asterisk denotes statistically significant differences. All screening rates are weighted.

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative cohort of older adults, our study confirmed important black-white disparities in breast and colorectal cancer screening for older adults with longer life expectancies. A few prior studies that examined overuse of screening as defined solely by screening beyond a certain age found lower screening rates among older minority patients [4]. In contrast, when we examined over-screening by limited life expectancy, we did not find racial differences in breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer screenings for those with limited life expectancies (though the interaction between race and life expectancy was not statistically significant). The reasons underlying this apparent attenuation of cancer screening disparities in those with limited life expectancy are unknown; it may be related to different patterns of health care utilization by life expectancy, that lower life expectancy is associated with lower socioeconomic status [5], or other factors. Despite guidelines recommending against routine cancer screening in patients with limited life expectancy, there remain substantial rates of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer screening in those with limited life expectancy across racial groups, and efforts to reduce over-screening are needed.

Author Contributions

Dr. Schoenborn had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Schoenborn, Huang, Boyd, Pollack

Data analysis and interpretation: Schoenborn, Huang, Boyd, Pollack

Preparation and review of the manuscript: Schoenborn, Huang, Boyd, Pollack

Funding Information

Dr. Schoenborn was supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (K76AG059984). Dr. Boyd was supported by 1K24AG056578 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of the paper.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. Dr. Pollack has stock ownership in Gilead Pharmaceuticals. We do not believe this has resulted in any conflict with the design, methodology, or results presented in this manuscript. Dr. Cynthia Boyd received a small payment from UptoDate for having co-authored a chapter on Multimorbidity, we do not believe this has resulted in any conflict with the design, methodology, or results presented in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Royce TJ, Hendrix LH, Stokes WA, et al. Cancer screening rates in individuals with different life expectancies. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1558–65. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray TF, Cudjoe J, Murphy J, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Wenzel J, Han HR. Disparities in cancer screening practices among minority and underrepresented populations. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33(2):184–198. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, et al. Predicting 10-year mortality for older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(9):874–876. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kressin NR, Groeneveld PW. Race/ethnicity and overuse of care: a systematic review. Milbank Q. 2015;93(1):112–38. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]