Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal disease characterized by progressive muscle paralysis due to the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. Recent studies point out an involvement of the non-motor axis during disease progression. Despite smell impairment being considered a potential non-motor finding in ALS, the pathobiochemistry at the olfactory level remains unknown. Here, we applied an olfactory quantitative proteotyping approach to analyze the magnitude of the olfactory bulb (OB) proteostatic imbalance in ALS subjects (n = 12) with respect to controls (n = 8). Around 3% of the quantified OB proteome was differentially expressed, pinpointing aberrant protein expression involved in vesicle-mediated transport, macroautophagy, axon development and gliogenesis in ALS subjects. The overproduction of olfactory marker protein (OMP) points out an imbalance in the olfactory signal transduction in ALS. Accompanying the specific overexpression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and Bcl-xL in the olfactory tract (OT), a tangled disruption of signaling routes was evidenced across the OB–OT axis in ALS. In particular, the OB survival signaling dynamics clearly differ between ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), two faces of TDP-43 proteinopathy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on high-throughput molecular characterization of the olfactory proteostasis in ALS.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, proteomics, signaling, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, TDP-43 proteinopathy

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) derives from a combined degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and motor cortex with a median survival rate of less than five years [1]. The prevalence is 3–5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year, affecting individuals of both genders with a peak incidence in ages across 50–65 years and showing a considerable phenotypic variability [2,3,4]. ALS may be categorized as sporadic ALS (sALS; 90% of cases) or familial ALS (fALS; 10% of the cases) which is linked to mutations in a large variety of apparently unrelated genes [5] although mutations in SOD1, TARDBP, FUS and C9orf72 are collectively present in more than 50% of fALS cases [6]. The TARDBP gene encodes the TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43), one of the major components of inclusion bodies in motor neurons of ALS patients [7]. The clinical hallmark of ALS is the involvement of motor neurons which leads to muscle weakness and eventual paralysis. Despite all the progress made in the last decade, the etiopathogenesis of ALS is still unknown, and disease-modifying treatments that could slow ALS progression are very limited [3]. In addition to TDP43-protein aggregates, different mechanisms have been proposed to drive ALS pathogenesis such as impaired proteostasis, disturbed RNA metabolism, nucleocytoplasmic and cytoskeletal and axon-transports defects, impaired DNA repair, vesicle-transport defects, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, astrogliosis and oligodendrocyte dysfunction [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Despite the disruption of these mechanisms potentially interrelating with each other, triggering the degeneration and death of the motor neuron [14], it remains to be established whether these imbalances are involved in the pathogenic mechanism or are a secondary event of the ALS process.

Although primarily classified as a neuromuscular disease, novel neuropathological and imaging information indicate an involvement of the non-motor axis during ALS progression [3]. Therefore, the capacity to monitor extra-motor abnormalities could be useful to increase the diagnostic and prognostic potential in ALS. For instance, 50% of ALS patients present cognitive impairments related to frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [15,16]. In fact, it is well known that there is a common clinical spectrum between ALS and FTD [17,18]. Importantly, multiple studies point out that olfactory dysfunction may be a potential non-motor finding in both ALS and FTD, [19,20,21,22,23,24]. In addition, patient-derived olfactory mucosa has been proposed as a cellular model to define the non-neuronal contribution to ALS pathology [25]. TDP43-positive inclusions have been observed across secondary olfactory centers (orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus), primary olfactory cortex and the olfactory bulb (OB) in post-mortem ALS brains [26]. Part of the human sensory system pathology is also recapitulated in SOD1G93A mice, the most commonly used mouse model of ALS which, however, presents no TDP43 inclusions [27,28,29]. However, the impact of ALS on olfactory structures remains to be elucidated. The olfactory system comprises a sensory organ, the olfactory epithelium (OE), located inside the nasal cavity together with the specific olfactory brain regions, which include the OB (the first brain region responsible for the processing of odor information) and the olfactory tract (OT). Thus, the scent’s molecular information is captured by the olfactory sensory neurons, located in the OE. Then, this information travels through the different layers of the OB, which include mitral and tufted cells, finally reaching the OT [30]. In view of clinical and neuropathological data, an in-depth molecular screening of the olfactory proteostasis is necessary to unveil the missing links in the biological understanding of the olfactory neurodegeneration in ALS. In this work, we applied an olfactory proteotyping approach based on quantitative mass-spectrometry and biochemical approaches to analyze the magnitude of the OB and OT proteome imbalance in the pathophysiology of ALS.

2. Results and Discussion

Taking into account that the severity of TDP-43 pathology follows a rostro-caudal gradient [31,32], previous neuroproteomic workflows have been mainly applied at cortical and spinal cord levels [33,34]. Being aware that ALS-associated proteins present cellular prion-like properties [35,36] and the OB is a site for prion-like propagation in neurological disorders [37], we have used OB proteomics [38,39,40] to characterize, for the first time, the potential disarrangement in the olfactory proteostasis that occur in ALS.

2.1. OB Proteome-Wide Analysis in Human ALS

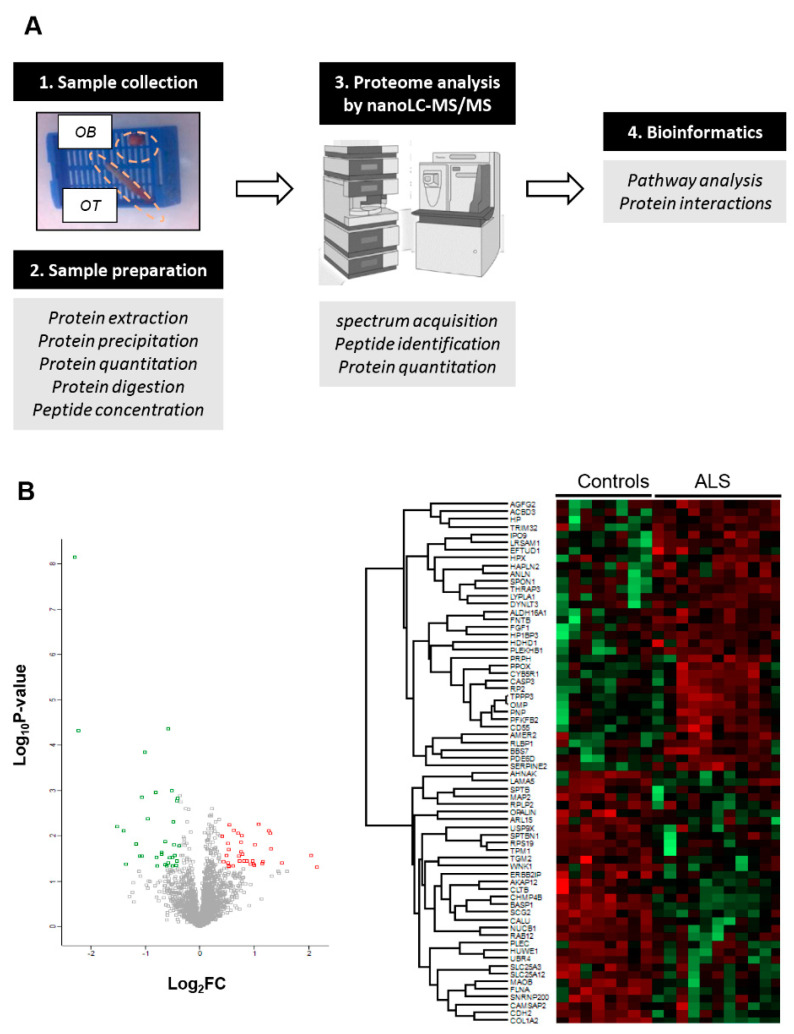

An in-depth label-free quantitative proteomics approach (Figure 1A) was used to monitor the OB protein expression profiling derived from ALS cases (n = 12) and neurological intact controls (n = 8). Among 4777 identified proteins, 2530 proteins were quantified across all samples (Supplementary Table S1), from which 68 proteins were differentially expressed (DEPs) between both groups (35 upregulated and 33 downregulated proteins in ALS) (Figure 1B and Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) An overview of the workflow used for the molecular characterization of the OB derived from ALS subjects (OB: olfactory bulb; OT: olfactory tract). (B) Volcano-plot representing the fold change of quantified proteins with associated p-value from the pair-wise quantitative comparisons of control vs ALS. Using international criteria, although 4777 proteins were identified, only proteins identified with at least two unique peptides were considered (2530 quantified proteins). A unique peptide is considered a peptide sequence that is exclusively present in a protein, and it is not shared across multiple proteins belonging for example to the same family. Down-regulated and up-regulated proteins are highlighted in green and red respectively (left). Heatmap representation showing both clustering and the degree of change for the differentially expressed proteins in ALS phenotype (Right).

Table 1.

Significantly deregulated proteins in OB derived from ALS subjects.

| Protein ID | Protein Name | Gene | p Value | FC | Activity/Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P80723 | Brain acid soluble protein 1 | BASP1 | 0.00 | 0.20 | transcription corepressor activity |

| P08123 | Collagen alpha-2(I) chain | COL1A2 | 0.00 | 0.21 | Integrin Pathway & Collagen trimerization |

| Q96PE5 | Opalin | OPALIN | 0.01 | 0.35 | oligodendrocyte terminal differentiation |

| Q7Z6Z7 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HUWE1 | HUWE1 | 0.01 | 0.38 | proteasomal degradation |

| O15230 | Laminin subunit alpha-5 | LAMA5 | 0.04 | 0.39 | Integrin Pathway & signaling by GPCR |

| Q09666 | Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK | AHNAK | 0.02 | 0.44 | Phospholipase-C Pathway |

| F5H7S3 | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain | TPM1 | 0.03 | 0.47 | cytoskeletal protein binding |

| O43852 | Calumenin | CALU | 0.00 | 0.48 | calcium ion binding |

| Q5T4S7 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase UBR4 | UBR4 | 0.03 | 0.48 | ubiquitin-protein transferase activity |

| P13521 | Secretogranin-2 | SCG2 | 0.00 | 0.50 | chemoattractant activity |

| Q02818 | Nucleobindin-1 | NUCB1 | 0.00 | 0.52 | Golgi calcium homeostasis |

| P21333 | Filamin-A | FLNA | 0.00 | 0.57 | crosslink actin filaments |

| P39019 | 40S ribosomal protein S19 | RPS19 | 0.03 | 0.58 | pre-rRNA processing |

| Q6IQ22 | Ras-related protein Rab-12 | RAB12 | 0.05 | 0.58 | Vesicle trafficking |

| O75643 | U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa helicase | SNRNP200 | 0.02 | 0.61 | mRNA splicing |

| P11277 | Spectrin beta chain, erythrocytic | SPTB | 0.03 | 0.62 | actin filament binding |

| Q93008 | Probable ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase FAF-X | USP9X | 0.01 | 0.64 | deubiquitinase, protein turnover |

| Q9NXU5 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 15 | ARL15 | 0.04 | 0.64 | GTP binding |

| Q15149 | Plectin | PLEC | 0.05 | 0.66 | Cytoskeleton remodeling Neurofilaments |

| F5GWT4 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase WNK1 | WNK1 | 0.04 | 0.67 | regulation of electrolyte homeostasis |

| Q9H444 | Charged multivesicular body protein 4b | CHMP4B | 0.00 | 0.67 | sorting of endocytosed cell-surface receptors |

| Q08AD1 | Calmodulin-regulated spectrin-associated protein 2 | CAMSAP2 | 0.03 | 0.68 | regulator of neuronal polarity |

| Q02952 | A-kinase anchor protein 12 | AKAP12 | 0.00 | 0.70 | subcellular compartmentation of PKA/PKC |

| P21980 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | TGM2 | 0.03 | 0.71 | cross-linking and conjugation of polyamines |

| P11137 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 | MAP2 | 0.04 | 0.71 | stabilization of microtubules |

| Q96RT1 | Protein LAP2 | ERBB2IP | 0.00 | 0.72 | Inhibits proinflammatory cytokine secretion |

| Q01082 | Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 1 | SPTBN1 | 0.02 | 0.72 | movement of the cytoskeleton |

| P05387 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 | RPLP2 | 0.03 | 0.73 | protein synthesis |

| O75746 | Calcium-binding mitochondrial carrier protein Aralar1 | SLC25A12 | 0.04 | 0.74 | exchange of Asp for Glu in the mitochondria |

| P27338 | Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] B | MAOB | 0.00 | 0.75 | metabolism of neuroactive and vasoactive amines |

| Q00325 | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | SLC25A3 | 0.04 | 0.75 | regulation of mitochondrial permeability |

| P19022 | Cadherin-2 | CDH2 | 0.00 | 0.75 | cell-cell adhesion |

| P09497 | Clathrin light chain B | CLTB | 0.02 | 0.77 | vesicle biogenesis |

| P07093 | Glia-derived nexin | SERPINE2 | 0.01 | 1.33 | endopeptidase inhibitor activity |

| Q08623 | Pseudouridine-5-phosphatase | HDHD1 | 0.04 | 1.35 | pyrimidine nucleoside salvage |

| Q7Z2Z2 | Elongation factor Tu GTP-binding domain-containing protein 1 | EFTUD1 | 0.03 | 1.41 | translational activation of ribosomes |

| P00491 | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | PNP | 0.01 | 1.43 | nucleoside binding |

| P49356 | Protein farnesyltransferase subunit beta | FNTB | 0.01 | 1.43 | farnesyltransferase activity |

| O60825 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 2 | PFKFB2 | 0.04 | 1.44 | Synthesis/degradation of fructose 2,6-bisP |

| Q9H3P7 | Golgi resident protein GCP60 | ACBD3 | 0.02 | 1.44 | maintenance of Golgi structure |

| P50336 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase | PPOX | 0.05 | 1.45 | heme biosynthesis |

| Q9GZV7 | Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 2 | HAPLN2 | 0.05 | 1.45 | establishment of blood-nerve barrier |

| Q96P70 | Importin-9 | IPO9 | 0.01 | 1.46 | nuclear protein import |

| P02790 | Hemopexin | HPX | 0.04 | 1.53 | heme transport |

| Q9BW30 | Tubulin polymerization-promoting protein family member 3 | TPPP3 | 0.01 | 1.54 | Regulator of microtubule dynamics |

| Q9UHQ9 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 1 | CYB5R1 | 0.01 | 1.62 | desaturation/elongation of fatty acids |

| O75608 | Acyl-protein thioesterase 1 | LYPLA1 | 0.03 | 1.64 | phospholipase activity |

| Q5SSJ5 | Heterochromatin protein 1-binding protein 3 | HP1BP3 | 0.04 | 1.66 | heterochromatin organization |

| Q13049 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM32 | TRIM32 | 0.02 | 1.69 | ubiquitin-protein transferase activity |

| O95081 | Arf-GAP domain and FG repeat-containing protein 2 | AGFG2 | 0.01 | 1.70 | GTPase activator activity |

| Q8IWZ6 | Bardet-Biedl syndrome 7 protein | BBS7 | 0.01 | 1.70 | cilium assembly |

| F5GZH3 | Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family B member 1 | PLEKHB1 | 0.03 | 1.73 | cell differentiation |

| A6NGJ0 | Dynein light chain Tctex-type 3 | DYNLT3 | 0.04 | 1.76 | intracellular retrograde motility of vesicles |

| Q8IZ83 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 16 member A1 | ALDH16A1 | 0.04 | 1.82 | oxidoreductase activity |

| Q9NQW6 | Actin-binding protein anillin | ANLN | 0.04 | 1.91 | actomyosin contractile ring assembly |

| P05230 | Fibroblast growth factor 1 | FGF1 | 0.04 | 1.96 | Integrin binding |

| O43924 | GMP-Phosphodiesterase delta | PDE6D | 0.04 | 1.97 | ciliary targeting of farnesylated proteins |

| P42574 | Caspase-3;Caspase-3 subunit p17;Caspase-3 subunit p12 | CASP3 | 0.04 | 1.99 | apoptosis execution |

| Q9HCB6 | Spondin-1 | SPON1 | 0.02 | 2.01 | attachment of spinal cord & sensory neuron cells |

| Q6UWE0 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase LRSAM1 | LRSAM1 | 0.01 | 2.12 | ubiquitin-protein transferase activity |

| P12271 | Retinaldehyde-binding protein 1 | RLBP1 | 0.04 | 2.22 | retinoid metabolism |

| Q8N7J2 | APC membrane recruitment protein 2 | AMER2 | 0.04 | 2.23 | Wnt signaling pathway |

| O75695 | Protein XRP2 | RP2 | 0.01 | 2.40 | post-Golgi vesicle-mediated transport |

| H3BLV0 | Complement decay-accelerating factor | CD55 | 0.01 | 2.45 | regulation of the complement cascade |

| Q9Y2W1 | Thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 3 | THRAP3 | 0.02 | 2.49 | regulation of mRNA splicing & transcription |

| P47874 | Olfactory marker protein | OMP | 0.04 | 2.84 | modulator of the olfactory signal-transduction |

| P00738 | Haptoglobin | HPR | 0.03 | 4.12 | antioxidant activity |

| P41219 | Peripherin | PRPH | 0.05 | 4.46 | Class-III neuronal intermediate filament |

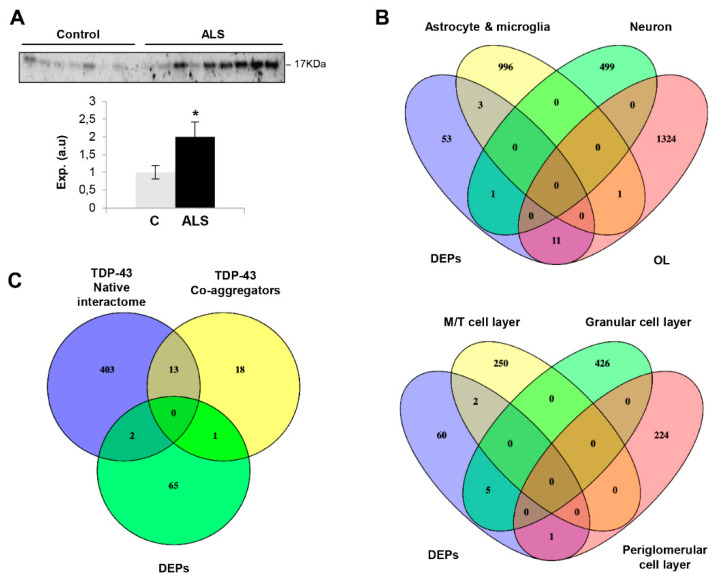

ALS-related proteins such as TDP43, SOD1 and FUS were unchanged in the OB (Supplementary Table S1). Curiously, 9 out of 68 DEPs have been previously linked to ALS (Table 1). Specifically, RPS19 is altered in reactive glial cells of hSOD1G93A mice [41]. PLEC and PRPH genes present mutations linked to familial ALS phenotypes [42,43]. MAP2 has been recently proposed as a CSF biomarker candidate in ALS [44]. MAOB and CASP3 activities are altered in the spinal cord of human ALS and motoneurons of SOD1-mutant mouse models, respectively [45,46]. SERPINE2 is a component of neurofilament conglomerates of motoneurons [47]. PLEKHB1 levels are deregulated in motoneurons at motor symptom onset in TDP-43-driven ALS models [48]. High CD55 levels have been observed in the motor end-plates of ALS [49]. Subsequent experiments were performed to check the levels of olfactory marker protein (OMP), an ALS-unrelated protein differentially expressed in ALS OBs. As shown in Figure 2A, OMP was upregulated in ALS at the level of the OB, confirming the mass-spectrometry results. OMP is involved in olfactory signal transduction with an apparent multitask role as a potential phosphodiesterase inhibitor upstream of cAMP production in olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) cilia [50], determining the duration of odor responses by OSNs [51,52], aiding the OSN maturation [53] and sparsening the primary olfactory input to the brain [54]. All this information together with the involvement of OMP in the formation and refinement of the olfactory glomerular map [55] points out that abnormal levels of OMP may trigger an aberrant interpretation of sensory stimuli in ALS patients.

Figure 2.

(A) OB Protein expression changes of OMP in ALS subjects by Western blotting. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. control group; (a.u: arbitrary units). (B) Cluster-enriched genes in specific brain cell-types (upper) and OB cell layers (lower) that are differentially expressed at the level of the OB in ALS subjects. (C) Venn diagram showing the overlap between differential OB proteins and experimentally demonstrated TDP-43 interactors and co-aggregators. (DEPs: differential expressed proteins; OL: oligodendrocyte; M/T: mitral/tufted cells).

It is important to note that the technological workflow applied is biased to the identification of highly abundant proteins, hampering the accurate detection and quantification of protein subsets expressed at low levels that may also be disrupted in ALS phenotypes. Moreover, our olfactory proteotyping is not able to differentiate between the OB cell layers. To overcome this drawback, previous single-cell RNA-seq datasets [56,57] were used to perform cell-type enrichment analysis across OB DEPs detected by mass-spectrometry. As shown in Figure 2B, a subset of olfactory DEPs is considered highly-enriched genes in specific brain cell populations: SCG2 in neurons, FGF1 in astrocytes, TGM2 and HP in microglia and COL1A2, OPALIN, SERPINE2, HAPLN2, TPPP3, PLEKHB1, ANLN, PDE6D, SPON1, RLBP1 and OMP in oligodendrocytes. Moreover, part of the proteostatic alterations tend to be specifically enriched in OB cell layers such as mitral/tufted cells (SCGN2, SPON1), periglomerullar cells (SERPINE2) and granular cell layers (BASP1, TPM1, RPS19, MAP2, SPTBN1) (Figure 2B). All these data help us to understand the molecular disturbances that accompany the neurodegenerative process across each cellular homeostasis in ALS.

2.2. Functional Analysis for the Differential Ob Proteome Detected in ALS

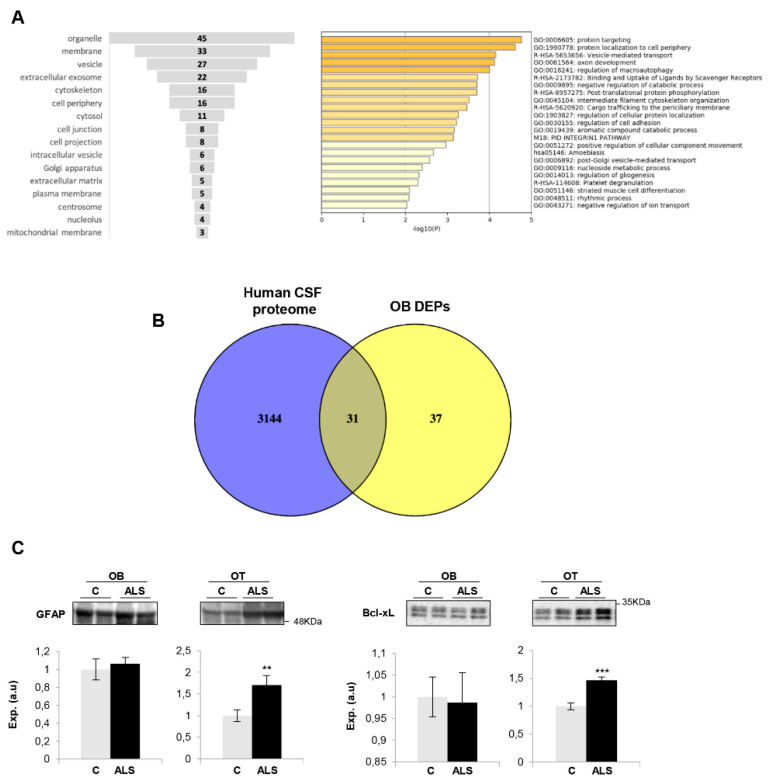

Due to TDP43-positive inclusions having been observed in the OB from ALS subjects [26], we have interlocked the native and co-aggregating interactome from human TDP-43 [58] with the differential OB dataset to obtain additional information about the potential role of the OB aberrantly expressed proteins in the field of ALS. The downregulated RNA binding proteins SNRNP200 (U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa helicase) and AHNAK (neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK) are components of the native TDP-43 interactome (obtained from BIOGRID; https://thebiogrid.org/) (Figure 2C). PRPH (Peripherin), the most OB upregulated protein in ALS, is a co-aggregator of TDP-43 (Figure 2C), previously detected in motor neuron inclusions of ALS. According to cellular component analysis, DEPs were mainly mapped in membranes, organelles, vesicles and cytoskeleton (Figure 3A). A deep synaptic ontology analysis revealed that part of the protein derangements is directly related to the structural integrity of the synapse (Supplementary Table S2). To characterize the metabolic modulation at the level of the OB, the differential proteomic map (Table 1) was functionally analyzed. As shown in Figure 3A, vesicle-mediated transport (p-value: 71248E-05), macroautophagy (p-value: 99648E-05), nucleoside metabolism (p-value: 0.004), axon development (p-value: 766171E-05) and gliogenesis (p-value: 0.004) were part of the significantly overrepresented dysregulated processes in ALS subjects (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 3.

(A) Functional analysis of OB differentially expressed proteins in ALS. Cell-compartment distribution (left) and statistically significant enriched GO terms (right). (B) Venn diagram of proteins found in human CSF and differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in ALS OBs. Numbers represent the number of shared proteins in the respective overlapping areas. (C) OT Protein expression changes of GFAP and Bcl-xL in ALS subjects by Western blotting. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. control group; *** p < 0.001 vs. control group (a.u: arbitrary units). Equal loading of the gels was assessed by stain free digitalization.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows through the interstitial spaces of the brain, including a route through the olfactory system, along the lateral olfactory stria, down the olfactory tract (OT) to the OB [59]. Due to this olfactory CSF conduit, we consider that the application of olfactory proteomics [60,61] is an innovative approach to explore pathophysiological changes that might be monitored in CSF as a novel source of biomarkers in the context of ALS. For that, the OB differential dataset was compared with the most extensive human CSF proteome characterization [62]. As shown in Figure 3B, around 50% of the differential OB proteins have been previously detected in CSF, where 26 out of 31 proteins have not been previously linked to ALS (see Table 1), opening doors for these to be explored in biofluids as potential biomarkers for ALS diagnosis.

2.3. Imbalance in Survival Pathways Across the Olfactory Bulb-Tract Axis in ALS

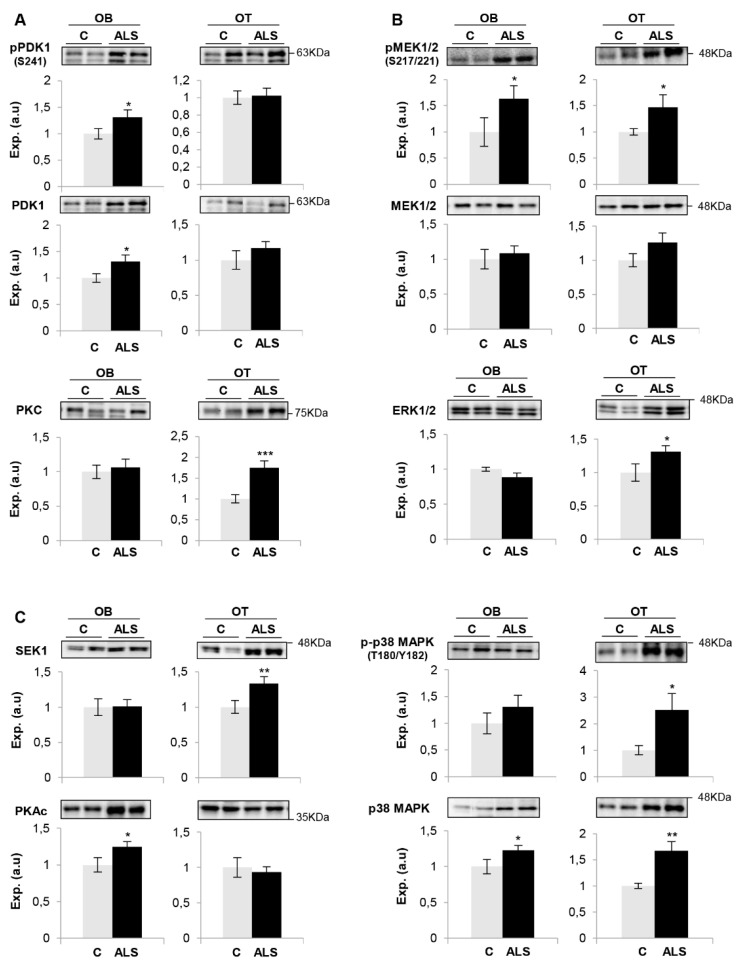

Much effort has been spent on studying the role of TDP-43 in human ALS pathogenesis but the available information is insufficient to understand the neurodegenerative impact at the level of olfactory areas. The olfactory tract (OT) is constituted by the axons coming from the mitral and tufted neurons located in the OB. Considering that the OT analysis may provide additional clues about the molecular disruptions along the olfactory system during the neurodegenerative process, subsequent experiments were performed to monitor olfactory astrogliosis across the OB–OT axis in ALS. We observed a specific increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in parallel with an overproduction of Bcl-xL in ALS OTs (Figure 3C). Both molecules are correlatively elevated in ALS (G93A) mice and affected humans, being considered relevant mediators in the astrocytic response to oxidative stress in ALS [63]. It is well known that multiple protein kinases are linked to a plethora of pathological mechanisms present in ALS and are considered to be the major drug target family exploited in the last decades [64]. Moreover, previous studies from our group have demonstrated a differential protein kinase imbalance across tauopathies, sinucleinopathies and tardopathies at the olfactory level [39,40,65]. Subsequent experiments were performed to partially monitor the signaling dynamics present in the OB-OT axis derived from ALS subjects. As shown in Figure 4, a significant increase in steady-state levels of PDK1 and PKAc was exclusively observed in ALS OBs with respect to controls (Figure 4A,C). While this is the first report linking PDK1 with ALS, it has been demonstrated that synaptic restoration by PKA drives activity-dependent neuroprotection to motoneurons in a mutSOD1 ALS mouse model [66]. On the other hand, steady-state levels of PKC, SEK1 and ERK1/2 were significantly increased at the level of OT in ALS subjects (Figure 4A–C). PKC activity is increased in ALS patients, suggesting effects on neuronal viability through voltage-dependent calcium channel regulation [67]. Moreover, several PKC isoforms are regulated and localized in the pre- and postsynaptic zones in the neuromuscular junctions, affected in ALS muscles [68,69]. Due to the complex functionality covered by all PKC isoforms in neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity, further exploration is needed to decipher the specific role of each PKC isoform (and its post-translational modifications) during the neurodegenerative process in ALS. We observed an overexpression of OT SEK1, an upstream regulator of JNK/SAPK. This pathway may play a neuroprotective role in motor neurons in ALS [70]; however, this route was unchanged across the ALS OB–OT axis (Supplementary Materials). ERK1/2 has been associated with TDP-43 aggregation [71]. Moreover, a significant increase in the activation state of MEK1/2 as well as an overexpression of p38 MAPK was observed across the OB–OT axis in ALS (Figure 4B,C). Interestingly, different therapeutic approaches leading to inhibit MEK1/2 inhibition have been established for potential ALS treatments. PD98059 reduces the phosphorylation of neurofilaments [72] and trametinib has shown preclinical efficacy in ALS models (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04326283). On the other hand, neurotoxic effects due to the appearance of reactive glial cells and the hyperphosphorylation of neurofilaments have been attributed to overexpression of p38 MAPK in the spinal motoneurons of transgenic SOD1 mice, increasing the production of nitric oxide and the apoptosis activation [73]. No appreciable changes were observed in the activation status of AKT, SAPK/JNK and CaMKII across the OB–OT axis in ALS (Supplementary Materials). Our data indicate that ALS induces a differential and tangled disruption in specific olfactory survival pathways, compromising the phosphorylation state and potentially the activity of multiple substrates at the level of the OB and OT, contributing to the increase of the proteostatic imbalance present at advanced stages of the disease.

Figure 4.

Signaling disruption across the OB-OT axis in ALS. State levels of PDK1, PKC (A), MEK1/2, ERK1/2 (B), SEK1, p38 MAPK, PKAc (C) across the OB-OT structures derived from controls and ALS subjects. Specific phosphorylation sites were also monitored in the case of PDK1, MEK1/2 and p38 MAPK. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. control group; ** p < 0.01 vs. control group. Equal loading of the gels was assessed using stain-free imaging technology, and protein normalization was performed by measuring total protein directly on the gels (a.u; arbitrary units).

On the whole, the kinase expression and/or activation profile partially differs between spinal cord and olfactory areas in ALS [74]. However, a downregulation in CaMKII, MEK1/2, PDK1 and PKC protein levels have been evidenced in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)-TDP43 subjects in respect to controls, maintaining normal levels of AKT, p38 MAPK and PKAc at the level of the OB [65]. All these data suggest that despite ALS and FTLD being two faces of TDP-43 proteinopathy with an overlap in clinical presentation and neuropathology, the OB proteostatic alterations clearly differ between both phenotypes. However, only 1–3% of the quantified OB proteome is aberrantly expressed in FTLD and ALS, compared with the olfactory proteostatic imbalance previously characterized in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (around 20%) [39,40]. Bearing in mind that additional studies are needed to evaluate the olfactory activation state of kinases responsible for TDP-43 phosphorylation/aggregation (CK-1δ, TTBK1/2 or CDC7) [64], our results lay the foundation for future exhaustive phosphoproteomics studies across the OB–OT axis in order to increase our understanding about the pathobiology that accompanies the neurodegenerative process across TDP-43 proteinopathies.

3. Materials and Methods

The workflow followed in this study is summarized in Figure 1A.

3.1. Materials

The following reagents and materials were used: anti-Bcl-xL (ref. 2764), anti-pAkt (Ser473) (ref. 4060), anti-Akt (ref. 4685), anti-pMEK1/2 (Ser217/221) (ref. 9154), anti-MEK1/2 (ref. 9126), anti-pERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (ref. 4370), anti-ERK1/2 (ref. 9102), anti-pPKA (Thr197) (ref. 5661), anti-PKA (ref. 4782), anti-pSEK1/MKK4 (Ser257/Thr261) (ref. 9156), anti-SEK1/MKK4 (ref. 9152), anti pSAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (ref. 9255), anti pSAPK/JNK (ref. 9252S), anti p-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) (ref. 4511), anti p38 MAPK (ref. 9212), anti-pCAMKII (Thr286) (ref. 12,716), anti-CAMKII (ref.11945), anti-pPDK1 (ser241) (ref. 3061), anti-PDK1 (ref. 3062) and anti-pPKC-pan (ref. 9379) were purchased from Cell signaling. Anti-GFAP (ref. ab7260) was purchased from Abcam. Anti PKC-pan (ref. SAB4502356) was from Sigma Aldrich. Electrophoresis reagents were purchased from Biorad and trypsin from Promega.

3.2. Human Samples

According to the Spanish Law 14/2007 of Biomedical Research, informed written consent forms of the Brain Bank of IDIBELL (Barcelona, Spain) were obtained for research purposes from relatives of patients included in this study. Post-mortem fresh-frozen olfactory bulbs and tracts of 12 ALS patients, and 8 age- and gender-matched controls, were obtained from the Brain Bank of IDIBELL (Barcelona, Spain) following the guidelines of Spanish legislation. The control group is composed of elderly subjects with no histological findings of any neurological disease. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all assessments, post-mortem evaluations, and procedures were previously approved by the Local Clinical Ethics Committee (PI_2019/108). All human brains considered in the proteomics and follow-up phases had a post-mortem interval (PMI) lower than 19 h (Table 2). In all cases, neuropathological assessment was performed according to standardized neuropathological guidelines [75].

Table 2.

Clinicopathological data of ALS subjects included in this study.

| Groups | Age (years) | Onset | Sex | PMI | Neuropathological Diagnosis | AD Stages | OB Analysis | OT Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 65 | - | F | 3 h 45 m | Status cribosus | I/0 | Yes | No |

| 74 | - | M | 9 h 25 m | Lacunar infarction | III/A | Yes | No | |

| 45 | - | M | 18 h 30 m | Status cribosus | 0/0 | Yes | No | |

| 51 | - | F | 4 h | No lesions | 0/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 67 | - | M | 5 h 50 m | Amyloid angiopathy | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 59 | - | F | 5 h 30 m | Metastatic carcinoma | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 60 | - | F | 12 h | Status cribosus | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 75 | - | M | 5 h 30 m | Status cribosus | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| ALS | 57 | Bulbar | M | 4 h | ALS | IIA | Yes | Yes |

| 75 | Bulbar | F | 4 h 5 m | ALS | IIA | Yes | Yes | |

| 79 | Spinal | F | 2 h 10 m | ALS | IIA | Yes | Yes | |

| 57 | Bulbar | F | 10 h | ALS | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 50 | Spinal | M | 10 h 10 m | ALS | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 75 | Bulbar | M | 3 h | ALS | II/B | Yes | Yes | |

| 71 | Spinal | M | 3 h 25 m | ALS | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 68 | Bulbar | F | 16 h 30 m | ALS | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 63 | Spinal | F | 18 h | ALS | I/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 53 | Bulbar | F | 10 h | ALS | 0/0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 71 | Bulbar | F | 18 h | ALS | I/A | Yes | Yes | |

| 45 | Spinal | F | 4 h | ALS | 0/0 | Yes | Yes |

3.3. Sample Preparation for Proteomic Analysis

Whole OB specimens (70–80 mg) derived from controls and ALS cases were homogenized using ‘’mini potters’’ in lysis buffer containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea and 50 mM DTT. The homogenates were spun down at 100,000× g for 1 h at 15 °C. Before proteomic analysis, protein extracts were precipitated and pellets were dissolved in 6 M Urea and Tris 100 mM pH 7.8. Protein quantitation was performed with the Bradford assay kit (Bio-Rad). The protein extract for each sample was diluted in Laemmli sample buffer and loaded into a 0.75-mm-thick polyacrylamide gel with a 4% stacking gel casted over a 12.5% resolving gel. The run was stopped as soon as the front entered 3 mm into the resolving gel so that the whole proteome became concentrated in the stacking/resolving gel interface. Bands were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and excised from the gel. Protein enzymatic cleavage (10 ug) was carried out with trypsin (Promega; 1:20, w/w) at 37 °C for 16 h as previously described (Shevchenko et al., 2006). Peptides were purified and concentrated using C18 Zip Tip Solid Phase Extraction (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

3.4. Label Free LC-MS/MS

Mass spectrometric analyses were performed on an EASY-nLC 1200 liquid chromatography system interfaced with a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) via a nanospray flex ion source. A total of 1 ug of tryptic peptides was loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap100 precolumn (75 um × 2 cm, Thermo Scientific) connected to an Acclaim PepMap RSLC (75 um × 25 cm, Thermo Scientific) analytical column. Peptides were eluted from the column at a flow rate of 250 nL min-1 using the following percentage of buffer B in the gradient (buffer A: 0.1% formic acid, buffer B: 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid): 3 min 5%, 7 min 5–7%, 105 min 7–22%, 25 min 22–27%, 15 min 27–31%, 28 min 31–53%, 1 min 53–95%. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode and a data-dependent acquisition mode was used. The spray voltage was set at 1.9 keV, the capillary temperature at 300 °C and the S-Lens RF level at 50. Full MS scans were acquired from m/z 375 to 1800 with a resolution of 60,000 at m/z 200. The 15 most intense ions were fragmented by higher energy C-trap dissociation with normalized collision energy of 28 and MS/MS spectra were recorded with a resolution of 15,000 at m/z 200. The maximum ion injection time was 45 ms for survey and for MS/MS scans, whereas AGC target values of 3 × 106 and 5 × 105 were used for survey and MS/MS scans, respectively. A dynamic exclusion time of 40 s was applied and singly charged ions, ions with 6 or more charges, and ions with unassigned charge states were excluded from MS/MS. Data were acquired using Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific).

3.5. Protein Identification and Quantification

Mass spectrometry raw data were processed using the MaxQuant software (v.1.6.3.3) [76] following the next parameters. Data were searched against the Homo Sapiens UniProtKB database (February 2019) also containing frequent contaminants and the reversed version of all sequences. In the group-specific parameters, main peptide search and first search tolerance were set as 4.5 ppm and 20 ppm, respectively. In addition, trypsin was selected as the enzyme with a maximum of two missed cleavages, and methionine oxidation and N-terminal acetylation were selected as variable modifications whereas carbamidomethylation was selected as fixed. In the global parameters, the minimum peptide length was set to 7 amino acids, fragment mass deviation to 40 ppm and false discovery rate (FDR) for peptide spectrum match (PSM) and peptide and protein identification were set to 1%. The output file ‘’proteingroups.txt’’ generated by MaxQuant was then analyzed with the Perseus software (v.1.6.2.3) [77]. Potential contaminants and proteins identified as reversed were removed. Protein identification was considered valid with at least two unique or razor peptides whereas protein quantification was calculated using at least two unique peptides. Statistical significance was calculated by a two-way Student’s t-test (p < 0.05) and a 1.3-fold change cut-off was used. Thus, proteins with ratios below the low range of 0.77 were considered downregulated whereas those above the high range 1.33 were considered upregulated. Data visualization was also performed with Perseus. MS raw data and search results files were deposited in the Proteome Xchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository [78] with the identifier PXD021630 (reviewer account details: Username: reviewer_pxd021630@ebi.ac.uk; Password: akmkhVDw).

3.6. Bioinformatics

TDP43 interactome and pathway analysis were performed by BioGrid [79] and Metascape [80] respectively.

3.7. Western-Blotting

Equal amounts of protein (10 µg) were resolved in 4–15% stain free SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-rad). OB and OT proteins derived from control and ALS subjects (Table 2) were electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Trans-blot Turbo transfer system (up to 25 V, 7 min) (Bio-rad). Membranes were probed with primary antibodies (between 1:200 and 1:1000 dilution) in 5% nonfat milk or BSA according to manufacturer instructions. After incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000), the immunoreactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminiscence (Perkin Elmer) and detected by a Chemidoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Equal loading of the gels was assessed by stain free digitalization. After densitometric analyses (Image Lab Software Version 5.2; Bio-Rad), optical density values were normalized to total stain in each gel lane and expressed as arbitrary units.

4. Conclusions

Our work provides novel insights regarding the olfactory proteostatic imbalance present in ALS. Besides the pathological TDP-43 depositions previously observed in olfactory areas, we have unveiled OB proteostatic rearrangements (only 3% of the quantified OB proteome), mainly affecting vesicle-mediated transport, macroautophagy, and axon development as well as cell survival routes. Nine differentially expressed proteins have been previously linked to ALS (RPS19, PLEC, PRPH, MAP2, MAOB, CASP3, SERPINE2, PLEKHB1, CD55). Interestingly, the imbalance in OMP protein levels together with the disruption in PDK1/PKC, MEK/ERK, SEK1 and the p38 MAPK axis suggest a partial alteration in the odor signal transduction across the OB–OT axis in ALS. Our data facilitate the understanding of the role of the olfactory axis in ALS pathophysiology, identifying not only differences between TDP-43 proteinopathies but also 26 ALS-unrelated protein intermediates that may be explored in CSF as candidate biomarkers for ALS diagnosis in early stages of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the patients and relatives that generously donor the brain tissue for research purposes. We are indebted to the Neurological Tissue Bank of HUB-ICO-IDIBELL (Barcelona, Spain) for sample and data procurement. Authors thank all PRIDE Team for helping with the mass spectrometric data deposit in ProteomeXChange/PRIDE. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in the Proteomics Core Facility-SGIKER at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU, ERDF, EU). The Proteomics Platforms of Navarrabiomed and University of the Basque Country are member of Proteored (PRB3-ISCIII) and are supported by grant PT17/0019/009, of the PE I+D+I 2013-2016 funded by ISCIII and FEDER. The Clinical Neuroproteomics Unit of Navarrabiomed is member of the Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research (GCCR) and the Spanish Olfactory Network (ROE) (supported by grant RED2018-102662-T funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation).

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| CAMK II | Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| OB/OT | Olfactory bulb/olfactory tract |

| OMP | Olfactory marker protein |

| p38 MAPK | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PMI | Post-mortem interval |

| SAPK/JNK | (stress-activated protein kinase/Jun-amino terminal kinase) |

| SEK1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase Kinase 4 |

| TDP43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/21/8311/s1. Supplementary material includes additional loading controls and Western-blots; Table S1: Quantified OB proteome; Table S2: Synaptic Ontology; Table S3: Functional analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.; Data curation, E.S.; Formal analysis, M.L.-M., N.M.; Funding acquisition, J.F.-I. and E.S.; Investigation, M.L.-M., N.M., K.A., J.F.-I., E.S.; Methodology, M.L.-M., N.M., K.A., P.A.-B., I.F.; Neuropathology: P.A.-B., I.F.; Writing–original draft, E.S.; and all authors gave final approval of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science Innovation and Universities (Ref. PID2019-110356RB-I00 to JF-I and ES) and the Department of Economic and Business Development from Government of Navarra (Ref. 0011-1411-2020-000028 to ES). The study was also supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competiveness, Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIII) (co-funded by European Regional Development Fund, ERDF, a way to build Europe): FISPI17/000809 to IF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brown R.H., Jr., Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiò A., Logroscino G., Traynor B., Collins J., Simeone J., Goldstein L., White L. Global Epidemiology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;41:118–130. doi: 10.1159/000351153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardiman O., Al-Chalabi A., Chio A., Corr E.M., Logroscino G., Robberecht W., Shaw P.J., Simmons Z., van den Berg L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017;3:17071. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swinnen B., Robberecht W. The phenotypic variability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014;10:661–670. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renton A.E., Chio A., Traynor B.J. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen P.M., Al-Chalabi A. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: What do we really know? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011;7:603–615. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann M., Sampathu D.M., Kwong L.K., Truax A.C., Micsenyi M.C., Chou T.T., Bruce J., Schuck T., Grossman M., Clark C.M., et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yerbury J.J., Farrawell N.E., McAlary L. Proteome Homeostasis Dysfunction: A Unifying Principle in ALS Pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robberecht W., Philips T. The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:248–264. doi: 10.1038/nrn3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeynaems S., Bogaert E., Van Damme P., Van Den Bosch L. Inside out: The role of nucleocytoplasmic transport in ALS and FTLD. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:159–173. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y.R., King O.D., Shorter J., Gitler A.D. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling S.C., Polymenidou M., Cleveland D.W. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: Disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters O.M., Ghasemi M., Brown R.H., Jr. Emerging mechanisms of molecular pathology in ALS. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1767–1779. doi: 10.1172/JCI71601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Chalabi A., Calvo A., Chio A., Colville S., Ellis C.M., Hardiman O., Heverin M., Howard R.S., Huisman M.H.B., Keren N., et al. Analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as a multistep process: A population-based modelling study. Lancet. Neurol. 2014;13:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70219-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burrell J.R., Kiernan M.C., Vucic S., Hodges J.R. Motor neuron dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134:2582–2594. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abramzon Y.A., Fratta P., Traynor B.J., Chia R. The Overlapping Genetics of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:42. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao F., Almeida S., Lopez-Gonzalez R. Dysregulated molecular pathways in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis–frontotemporal dementia spectrum disorder. EMBO J. 2017;36:2931–2950. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strong M.J., Abrahams S., Goldstein L.H., Woolley S., McLaughlin P., Snowden J., Mioshi E., Roberts-South A., Benatar M., Hortobágyi T., et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—Frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017;18:153–174. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2016.1267768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elian M. Olfactory impairment in motor neuron disease: A pilot study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1991;54:927–928. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.10.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkes C.H., Shephard B.C., Geddes J.F., Body G.D., Martin J.E. Olfactory disorder in motor neuron disease. Exp. Neurol. 1998;150:248–253. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty R.L. Olfactory dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases: Is there a common pathological substrate? Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:478–488. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viguera C., Wang J., Mosmiller E., Cerezo A., Maragakis N.J. Olfactory dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018;5:976–981. doi: 10.1002/acn3.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilotto A., Rossi F., Rinaldi F., Compostella S., Cosseddu M., Borroni B., Filosto M., Padovani A. Exploring Olfactory Function and Its Relation with Behavioral and Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neurodegener. Dis. 2016;16:411–416. doi: 10.1159/000446802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunther R., Schrempf W., Hahner A., Hummel T., Wolz M., Storch A., Hermann A. Impairment in Respiratory Function Contributes to Olfactory Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:79. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Escudero V., Rosales M., Munoz J.L., Scola E., Medina J., Khalique H., Garaulet G., Rodriguez A., Lim F. Patient-derived olfactory mucosa for study of the non-neuronal contribution to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathology. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2015;19:1284–1295. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda T., Iijima M., Uchihara T., Ohashi T., Seilhean D., Duyckaerts C., Uchiyama S. TDP-43 Pathology Progression Along the Olfactory Pathway as a Possible Substrate for Olfactory Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2015;74:547–556. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson J., Sanelli T., Xiao S., Yang W., Horne P., Hammond R., Pioro E.P., Strong M.J. Lack of TDP-43 abnormalities in mutant SOD1 transgenic mice shows disparity with ALS. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;420:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ringer C., Tune S., Bertoune M.A., Schwarzbach H., Tsujikawa K., Weihe E., Schutz B. Disruption of calcitonin gene-related peptide signaling accelerates muscle denervation and dampens cytotoxic neuroinflammation in SOD1 mutant mice. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:339–358. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ringer C., Weihe E., Schutz B. SOD1G93A Mutant Mice Develop a Neuroinflammation-Independent Dendropathy in Excitatory Neuronal Subsets of the Olfactory Bulb and Retina. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017;76:769–778. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munger S.D., Leinders-Zufall T., Zufall F. Subsystem organization of the mammalian sense of smell. Annu Rev. Physiol. 2009;71:115–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brettschneider J., Del Tredici K., Toledo J.B., Robinson J.L., Irwin D.J., Grossman M., Suh E., Van Deerlin V.M., Wood E.M., Baek Y., et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74:20–38. doi: 10.1002/ana.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fatima M., Tan R., Halliday G.M., Kril J.J. Spread of pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Assessment of phosphorylated TDP-43 along axonal pathways. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015;3:47. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedl T.J., San Gil R., Cheng F., Rayner S.L., Davidson J.M., De Luca A., Villalva M.D., Ecroyd H., Walker A.K., Lee A. Proteomics Approaches for Biomarker and Drug Target Discovery in ALS and FTD. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:548. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iridoy M.O., Zubiri I., Zelaya M.V., Martinez L., Ausin K., Lachen-Montes M., Santamaria E., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Jerico I. Neuroanatomical Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Common Pathogenic Biological Routes between Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;20:4. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smethurst P., Sidle K.C., Hardy J. Review: Prion-like mechanisms of transactive response DNA binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2015;41:578–597. doi: 10.1111/nan.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polymenidou M., Cleveland D.W. The seeds of neurodegeneration: Prion-like spreading in ALS. Cell. 2011;147:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rey N.L., Wesson D.W., Brundin P. The olfactory bulb as the entry site for prion-like propagation in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;109:226–248. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Santamaria E. Olfactory proteotyping: Towards the enlightenment of the neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14:979–981. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.249220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lachen-Montes M., Gonzalez-Morales A., Iloro I., Elortza F., Ferrer I., Gveric D., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Santamaria E. Unveiling the olfactory proteostatic disarrangement in Parkinson’s disease by proteome-wide profiling. Neurobiol. Aging. 2019;73:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lachen-Montes M., Gonzalez-Morales A., Zelaya M.V., Perez-Valderrama E., Ausin K., Ferrer I., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Santamaria E. Olfactory bulb neuroproteomics reveals a chronological perturbation of survival routes and a disruption of prohibitin complex during Alzheimer’s disease progression. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9115. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09481-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acquadro E., Caron I., Tortarolo M., Bucci E.M., Bendotti C., Corpillo D. Human SOD1-G93A specific distribution evidenced in murine brain of a transgenic model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:1800–1809. doi: 10.1021/pr400942n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Togawa J., Ohi T., Yuan J.H., Takashima H., Furuya H., Takechi S., Fujitake J., Hayashi S., Ishiura H., Naruse H., et al. Atypical Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Slowly Progressing Lower Extremities-predominant Late-onset Muscular Weakness and Atrophy. Intern. Med. 2019;58:1851–1858. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2222-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oberstadt M., Classen J., Arendt T., Holzer M. TDP-43 and Cytoskeletal Proteins in ALS. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:3143–3151. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oeckl P., Weydt P., Thal D.R., Weishaupt J.H., Ludolph A.C., Otto M. Proteomics in cerebrospinal fluid and spinal cord suggests UCHL1, MAP2 and GPNMB as biomarkers and underpins importance of transcriptional pathways in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139:119–134. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekblom J., Aquilonius S.M., Jossan S.S. Differential increases in catecholamine metabolizing enzymes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 1993;123:289–294. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasinelli P., Houseweart M.K., Brown R.H., Jr., Cleveland D.W. Caspase-1 and -3 are sequentially activated in motor neuron death in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-mediated familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:13901–13906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240305897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chou S.M., Taniguchi A., Wang H.S., Festoff B.W. Serpin=serine protease-like complexes within neurofilament conglomerates of motoneurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998;160(Suppl. 1):S73–S79. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marques R.F., Engler J.B., Kuchler K., Jones R.A., Lingner T., Salinas G., Gillingwater T.H., Friese M.A., Duncan K.E. Motor neuron translatome reveals deregulation of SYNGR4 and PLEKHB1 in mutant TDP-43 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bahia El Idrissi N., Bosch S., Ramaglia V., Aronica E., Baas F., Troost D. Complement activation at the motor end-plates in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016;13:72. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0538-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reisert J., Yau K.W., Margolis F.L. Olfactory marker protein modulates the cAMP kinetics of the odour-induced response in cilia of mouse olfactory receptor neurons. J. Physiol. 2007;585:731–740. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buiakova O.I., Baker H., Scott J.W., Farbman A., Kream R., Grillo M., Franzen L., Richman M., Davis L.M., Abbondanzo S., et al. Olfactory marker protein (OMP) gene deletion causes altered physiological activity of olfactory sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9858–9863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakashima N., Nakashima K., Taura A., Takaku-Nakashima A., Ohmori H., Takano M. Olfactory marker protein directly buffers cAMP to avoid depolarization-induced silencing of olfactory receptor neurons. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2188. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15917-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee A.C., He J., Ma M. Olfactory marker protein is critical for functional maturation of olfactory sensory neurons and development of mother preference. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:2974–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5067-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kass M.D., Moberly A.H., Rosenthal M.C., Guang S.A., McGann J.P. Odor-specific, olfactory marker protein-mediated sparsening of primary olfactory input to the brain after odor exposure. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:6594–6602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1442-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albeanu D.F., Provost A.C., Agarwal P., Soucy E.R., Zak J.D., Murthy V.N. Olfactory marker protein (OMP) regulates formation and refinement of the olfactory glomerular map. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5073. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07544-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tepe B., Hill M.C., Pekarek B.T., Hunt P.J., Martin T.J., Martin J.F., Arenkiel B.R. Single-Cell RNA-Seq of Mouse Olfactory Bulb Reveals Cellular Heterogeneity and Activity-Dependent Molecular Census of Adult-Born Neurons. Cell Rep. 2018;25:2689–2703.e2683. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y., Chen K., Sloan S.A., Bennett M.L., Scholze A.R., O’Keeffe S., Phatnani H.P., Guarnieri P., Caneda C., Ruderisch N., et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ciryam P., Lambert-Smith I.A., Bean D.M., Freer R., Cid F., Tartaglia G.G., Saunders D.N., Wilson M.R., Oliver S.G., Morimoto R.I., et al. Spinal motor neuron protein supersaturation patterns are associated with inclusion body formation in ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E3935–E3943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613854114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ethell D.W. Disruption of cerebrospinal fluid flow through the olfactory system may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:1021–1030. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lachen-Montes M., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Santamaria E. Deconstructing the molecular architecture of olfactory areas using proteomics. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2016 doi: 10.1002/prca.201500147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lachen-Montes M., Gonzalez-Morales A., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Santamaria E. Deployment of Label-Free Quantitative Olfactory Proteomics to Detect Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Candidates in Synucleinopathies. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;2044:273–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9706-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macron C., Lavigne R., Nunez Galindo A., Affolter M., Pineau C., Dayon L. Exploration of human cerebrospinal fluid: A large proteome dataset revealed by trapped ion mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Data Brief. 2020;31:105704. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee J., Kannagi M., Ferrante R.J., Kowall N.W., Ryu H. Activation of Ets-2 by oxidative stress induces Bcl-xL expression and accounts for glial survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. FASEB J. 2009;23:1739–1749. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palomo V., Nozal V., Rojas-Prats E., Gil C., Martinez A. Protein kinase inhibitors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis therapy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bph.15221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lachen-Montes M., Gonzalez-Morales A., Schvartz D., Zelaya M.V., Ausin K., Fernandez-Irigoyen J., Sanchez J.C., Santamaria E. The olfactory bulb proteotype differs across frontotemporal dementia spectrum. J. Proteom. 2019;201:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baczyk M., Alami N.O., Delestree N., Martinot C., Tang L., Commisso B., Bayer D., Doisne N., Frankel W., Manuel M., et al. Synaptic restoration by cAMP/PKA drives activity-dependent neuroprotection to motoneurons in ALS. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217 doi: 10.1084/jem.20191734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krieger C., Lanius R.A., Pelech S.L., Shaw C.A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The involvement of intracellular Ca2+ and protein kinase C. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:114–120. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lanuza M.A., Santafe M.M., Garcia N., Besalduch N., Tomas M., Obis T., Priego M., Nelson P.G., Tomas J. Protein kinase C isoforms at the neuromuscular junction: Localization and specific roles in neurotransmission and development. J. Anat. 2014;224:61–73. doi: 10.1111/joa.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Camerino G.M., Fonzino A., Conte E., De Bellis M., Mele A., Liantonio A., Tricarico D., Tarantino N., Dobrowolny G., Musaro A., et al. Elucidating the Contribution of Skeletal Muscle Ion Channels to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in search of new therapeutic options. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:3185. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Migheli A., Piva R., Atzori C., Troost D., Schiffer D. c-Jun, JNK/SAPK kinases and transcription factor NF-kappa B are selectively activated in astrocytes, but not motor neurons, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997;56:1314–1322. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ayala V., Granado-Serrano A.B., Cacabelos D., Naudi A., Ilieva E.V., Boada J., Caraballo-Miralles V., Llado J., Ferrer I., Pamplona R., et al. Cell stress induces TDP-43 pathological changes associated with ERK1/2 dysfunction: Implications in ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:259–270. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0850-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strong M.J., Kesavapany S., Pant H.C. The pathobiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A proteinopathy? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005;64:649–664. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000173889.71434.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ackerley S., Grierson A.J., Banner S., Perkinton M.S., Brownlees J., Byers H.L., Ward M., Thornhill P., Hussain K., Waby J.S., et al. p38alpha stress-activated protein kinase phosphorylates neurofilaments and is associated with neurofilament pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu J.H., Zhang H., Wagey R., Krieger C., Pelech S.L. Protein kinase and protein phosphatase expression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord. J. Neurochem. 2003;85:432–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Strong M.J., Horobágyi T., Okamoto K., Kato S. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, primary lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular atrophy. In: Dickson D.W., Weller R.O., editors. Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publish Ltd.; Oxford, UK: 2011. pp. 418–433. 2011 International Society of Neuropathology. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cox J., Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tyanova S., Temu T., Sinitcyn P., Carlson A., Hein M.Y., Geiger T., Mann M., Cox J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:731–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vizcaino J.A., Deutsch E.W., Wang R., Csordas A., Reisinger F., Rios D., Dianes J.A., Sun Z., Farrah T., Bandeira N., et al. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oughtred R., Stark C., Breitkreutz B.J., Rust J., Boucher L., Chang C., Kolas N., O’Donnell L., Leung G., McAdam R., et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D529–D541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.