Abstract

Drug repurposing involves the identification of new applications for existing drugs at a lower cost and in a shorter time. There are different computational drug-repurposing strategies and some of these approaches have been applied to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Computational drug-repositioning approaches applied to COVID-19 can be broadly categorized into (i) network-based models, (ii) structure-based approaches and (iii) artificial intelligence (AI) approaches. Network-based approaches are divided into two categories: network-based clustering approaches and network-based propagation approaches. Both of them allowed to annotate some important patterns, to identify proteins that are functionally associated with COVID-19 and to discover novel drug–disease or drug–target relationships useful for new therapies. Structure-based approaches allowed to identify small chemical compounds able to bind macromolecular targets to evaluate how a chemical compound can interact with the biological counterpart, trying to find new applications for existing drugs. AI-based networks appear, at the moment, less relevant since they need more data for their application.

Keywords: COVID-19, network-based approaches, molecular docking, AI, new therapies, drug repurposing

Introduction

Recycling old drugs trying to treat new diseases, rescuing shelved drugs and extending patents’ lives make drug repurposing (also known as drug repositioning) an attractive form of drug discovery [1–4]. Repurposing can help to identify new therapies for diseases at a lower cost and in a shorter time, particularly in those cases where preclinical safety studies have already been completed [5]. It can play a key role in “therapeutic stratification procedure” for patients with rare, complex or chronic diseases with less effective or no marketed treatment options available [6]. To date, the most notable repurposed drugs have been discovered either through serendipity, based on specific pharmacological insights or using experimental screening platforms [7–11].

The advent of genomics technologies and computational approaches has led to the development of novel approaches for drug repositioning. With the drug-related data growth and open-data initiatives, a set of new repositioning strategies and techniques has emerged with integrating data from various sources like pharmacological, genetic, chemical or clinical data [12]. These methods can accumulate evidence supporting discovery of new uses or indications for existing drugs [13]. The effectiveness of this approach is proved by the fact that the estimated success rate of drug repurposing ranges from 30% to 75%. The highest success rate occurs when the use of a drug is expanded in the same therapeutic area of its 1st indication [14]. To accelerate and increase the scale of such discoveries, several computational methods have been suggested to aid in drug repurposing [15]. Computational drug-repositioning methods can be classified into target-based, knowledge-based, signature-based, pathway- or network-based and targeted-mechanism-based methods. These methods focus on different orientations defined by available information and elucidated mechanisms, such as drug-oriented, disease-oriented and treatment-oriented [16]. These computational drug-repositioning methods enable researchers to examine nearly all drug candidates and test them on a relatively large number of diseases within significantly shortened time lines.

Therefore, integration of translational bioinformatics resources can enable the rapid application of drug repositioning on an increasingly broader scale [17, 18]. Efficient tools are now available for systematic drug-repositioning methods using large repositories of compounds with biological activities [19, 20]. Drug-repurposing strategy has been applied to various epidemics diseases and finds its relevant role with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [21]. COVID-19 has emerged by a novel coronavirus, now known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [21]. The evidences on the mechanism of infection, also derived from previous studies on coronaviruses, suggest that a key process is the interaction of viral spike protein with human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2): the receptor-binding domain of spike protein binds to the peptidase domain of human ACE2.

In this way, this last protein assumes the role of receptor in the binding of the virus to the host cell [23, 24]. The role of TMPRSS is related to the infection process, as it is one of the host proteases that cleave the spike protein in specific sites, thus activating the viral entrance in the host cell [23, 25, 26]. The main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is a key enzyme, which plays a pivotal role in mediating viral replication and transcription [27]. The other viral proteins concur in virus replication and spreading [28]. An in silico [29] and an experimental [30] analysis of the interaction network between human and SARS-CoV-2 proteins have been recently published and could suggest the most important targets for developing therapeutic approaches against this virus. Drug repurposing has already been suggested for specific drugs in the treatment of the current COVID-19 outbreak [31]. In particular, a remarkable number of drugs reconsidered for COVID-19 therapy are or have been used in cancer therapy [32]. Indeed, potentially suitable drugs against this virus are essentially those affecting signal transduction, synthesis of macromolecules and/or bioenergetics pathways and those able to interfere with the host immune response, in particular, the life-threatening cytokine storm associated with severe COVID-19. Additionally, antiviral compounds are occasionally effective in fighting cancer [33].

Here we will explain the most widely used computational drug-repurposing techniques applied to the search for new therapeutic approaches against COVID-19. Questa parte mi sembrava che fosse stata cancellata nella revised version! Non era così?

Drug-repurposing strategies for COVID-19

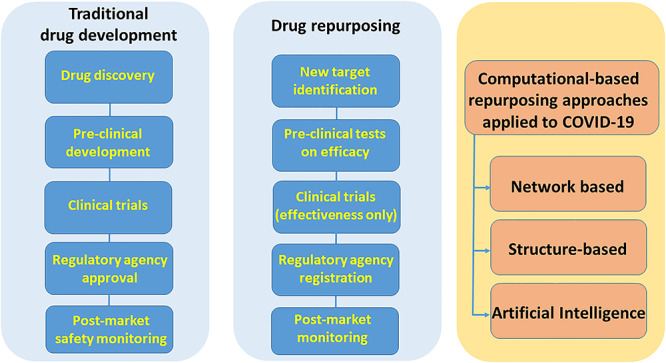

The drug-repurposing workflow is organized differently from traditional drug development. In drug repurposing there are fewer steps and different parameters to follow: compound identification, compound acquisition, development and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) post-market safety monitoring. Computational drug-repositioning approaches applied on COVID-19 can be broadly categorized as (i) network-based models, (ii) structure-based approaches or (iii) machine/deep learning approaches [4, 18, 19] (Figure 1). There are some papers that used hybrid approaches, and we classify, for example, a method consisting of both network and clustering as network-based if we think that network modeling is prevalent over machine learning. In this way, we find only few methods in which AI models are the prevalent methodology.

Figure 1.

Drug repurposing compared to traditional drug development workflow and drug-repurposing approaches applied to COVID-19

Network-based approach

Network-based approaches are vital and widely used in drug repositioning due to the associated ability to integrate multiple data sources [34, 35]. With the advances of high-throughput technology and bioinformatics methods, molecular interactions in the biological systems can be modeled by networks [36]. In these models, network nodes represent drugs, diseases or gene products, while edges represent interactions or relationships between nodes [37, 38]. The resulting pattern may facilitate the process of structure-guided pharmaceutical and diagnostic research with the prospect of identifying potential new biological targets. Previous studies have suggested that drug–target networks, drug–drug networks, drug–disease networks and protein interaction networks are useful in the identification of new opportunities for drug discovery or repositioning [39]. Network-based methodology combines a system pharmacology-based network medicine platform that quantifies the interplay between the virus–host interactome and drug targets in the human protein–protein interaction network [40].

There are two types of network-based approaches reviewed and applied to COVID-19 [41]: network-based clustering approaches and network-based propagation approaches. Network-based clustering approaches have been proposed to discover novel drug–disease or drug–target relationships [42]. These approaches aim to find several modules (drug–disease, drug–drug or drug–target) using clustering algorithms according to the topology structures of networks. Network-based propagation approaches are another important type of network-based approach. Human coronavirus (HCoV)-associated host proteins were collected from the literature and pooled to generate a pan-HCoV protein subnetwork. Network proximity between drug targets and HCoV-associated proteins was calculated to screen for candidate repurposable drugs for HCoVs under the human protein interactome model. By using a network-based method it is possible to analyze some important patterns useful to annotate the proteins that are functionally associated with HCoVs, which are localized within the comprehensive human interactome network. Furthermore, they can model the proteins that serve as drug targets for a specific disease and they may be suitable drug targets for potential antiviral infections owing to shared protein–protein interactions elucidated by the human interactome [43, 44].

The most important and relevant network-based approaches used for COVID-19 are summarized in Table 1, which shows their benefits, bottlenecks, databases and other information. The 1st six approaches [45, 50] are based on clustering methodologies applied to protein-protein interactions (PPIs), drug–protein–disease, drug–target–disease and drug–disease, while the last two approaches [51, 52] are based on the propagation methodology. Both methodologies have been explained within the text. Moreover, these methodologies not only provide an opportunity to improve the performance of existing methods but also offer a tool to design more efficient and stable approaches.

Table 1.

Network-based drug repurposing

| References | Name algorithm | Method | Network | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Possible repurposing drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al. [45] | RNSC | Clustering | PPI | A global network algorithm to identify protein clusters on PPI network | The method considers both local and global information from network. Overlapped clusters can be detected as well. | Some information may be dropped because the cluster size is small | Tamoxifen, Fulvestrant, Geldanamycin, Loperamide, Raloxifene, Tanespymicin, Alvespimycin |

| Macropol et al. [46] | RRW | Clustering | PPI | An effective network clustering approach to identify protein clusters on PPI network | This is a general method with a high predicted accuracy. | It is a time and memory expensive method that cannot detect overlapped clusters. | Some complex proteins |

| Cheng-Yu et al. [47] | ClusterONE | Clustering | PPI | A global network algorithm to identify node clusters in a network | This approach outperformed the other approaches including MCL, RRW and others both on weighted and unweighted PPI networks | There is not a gold standard to evaluate clusters | Some complex proteins |

| Nepusz et al. [48] | ClusterONE | Clustering | Drug–protein–disease | A variant of the ClusterONE algorithm to cluster nodes on a heterogeneous network | This is an efficient clustering approach that integrates multiple databases | It is difficult to distinguish between positive associations and negative associations in the network | Iloperidone |

| Bader et al. [49] | ClusterONE | Clustering | Drug–target–disease | An algorithm to detect clusters in the network | This is a general and highly robust approach | This approach loses weakly associated genes of diseases and drugs | Vismodegib |

| Huimin et al. [50] | MBiRW | Clustering | Drug–disease | A bi-random walk-based algorithm to predict disease–disease relationships | Predictions of this approaches are reliable | The approach needs to adopt more biological information to improve the confidence of the similarity metric | Levodopa, Cabergoline, Canertinib |

| Vanunu et al. [51] | PRINCE | Propagation | Disease–gene | A global propagation algorithm to predict disease–gene relationships | This is a global network approach combined with a novel normalization of PPI weights and disease–disease similarities | This approach relies on phenotype data, and so some diseases that lack phenotype information are excluded. The performance of this approach relies on data quality | Some disease–gene relationships |

| Martìnez et al. [52] | DrugNet | Propagation | Disease–drug–protein | A comprehensive propagation method to predict different propagation strategies in different subnets | This method is robust and efficient | The performance of this approach relies on the quality of disease data | Methotrexate, Gabapentin |

Structure-based approaches

Virtual screening can help in identifying small chemical compounds able to bind macromolecular targets with known or predicted 3D structure. It allows to screen even millions of compounds in a limited time, reducing the costs for finding hits suitable to develop new drugs, as well as to find new targets for existing drugs. This approach is based mainly on molecular docking, a computational strategy first developed to understand how a chemical compound can interact with a biological counterpart, but nowadays largely used for many other tasks, including drug repurposing [53, 54].

The 1st examples of structure-based drug repurposing applied to COVID-19 were published even before 3D structures of the viral proteins became available. Researchers applied homology modeling methods [55] to predict the structures of several target viral proteins, such as 3-chymotrypsin-like (3CL) protease, also known as main protease (Mpro), Spike, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), helicase and papain-like (PL) protease, which were identified as the most important targets for antiviral activity. These models were then used to perform virtual screening of compound libraries, including approved drugs for clinics and natural compounds. However, very soon after the isolation of the SARS-CoV-2 virion particle and genome sequencing, the structural biology community started an unprecedented huge effort to solve the structures of the most important proteins involved in viral infection, replication and dissemination. Protein Data Bank (PDB), the worldwide database for macromolecular structures [56] opened a section dedicated to COVID-19-related entries, and the 1st structure, deposited on 5 February 2020, was the one of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with an inhibitor identified by computer-aided drug design, solved at 2.16 Å resolution [27] (Supplementary Figure 1).

Since then, almost 500 structures of SARS-CoV-2 proteins (update: 14 October 2020), alone or associated to ligands and/or to their target cell receptors, have been solved and made available to the scientific community. The structures have been solved mainly by X-ray crystallography (about 80% of structures) and with a good resolution ( 2.5 Å in about 67% of structures). The release of these data has triggered an explosion of computational studies aimed at predicting the ability of known drugs either to inhibit their activity, or to impair the recognition and association with cell counterparts, necessary for the virus to penetrate the host cells and replicate. The general protocol applied was the extensive virtual screening of databases of drugs, made by different docking approaches, often followed by further computational protocols, such as molecular dynamics simulations and the prediction of the free energy associated to the interaction of the top hits with the selected target protein, in an effort to increase the reliability of the docking results [57].

2.5 Å in about 67% of structures). The release of these data has triggered an explosion of computational studies aimed at predicting the ability of known drugs either to inhibit their activity, or to impair the recognition and association with cell counterparts, necessary for the virus to penetrate the host cells and replicate. The general protocol applied was the extensive virtual screening of databases of drugs, made by different docking approaches, often followed by further computational protocols, such as molecular dynamics simulations and the prediction of the free energy associated to the interaction of the top hits with the selected target protein, in an effort to increase the reliability of the docking results [57].

Generally, no experimental validation was provided to the results. The starting point for screening were usually very popular databases with at least a section dedicated to approved drugs, which can provide the molecular structures of the chemical com-pounds in a docking-ready format. Some examples of general, freely available databases are ZINC [58], PubChem [59], DrugBank [60], Drug3D [61], SuperDRUG2 [62], ChEMBL [63], KEGG [64] and MTiOpenScreen [65]. Also, Asinex (http://www.asinex.com/), KNApSAcK (http://www.knapsackfamily.com/KNApSAcK/), NPC (https://tripod.nih.gov/npc/), Reaxys (https://www.reaxys.com) and Selleckchem (https://www.selleckchem.com/) are popular resources for virtual screening of drugs, made by private companies. Other more focused databases for drug repurposing were also screened, such as DrugRepurposingHub [66]. In other cases, in-house databases were used. Many studies were made available as non-peer-reviewed preprints; in this review, we will not take them into account, judging them not sufficiently reliable. Of those published in a peer-reviewed form, we noticed that several papers were subjected to an accelerated peer-review process (less than 15 days) (Table 2), therefore these results must be considered with caution.

Table 2.

Structure-based approaches for drug repurposing adopted for coronavirus with an accelerated peer-review process (15 days)

| Reference | Method | Starting dataset | Target | Possible repurposing drugs | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aanouz et al. [67] | Docking | 67 molecules of natural origin from Moroccan medicinal plants | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Crocin, Digitoxigenin, beta-eudesmol, | Accelerated peer-review (6 days) |

| Arun et al. [70] | Pharmacophore generation + docking + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) + MD on the top 4 hits | SuperDRUG2 (>4600 marketed pharmaceuticals) | Main protease (PDB: 6W63) | Binifibrate, Bamifylline | Accelerated peer review (8 days) |

| Das et al. [72] | Docking | Natural products, antivirals, anti-fungals, anti-nematodes, anti-protozoals (33 compounds) | Main protease (PDB: 6Y84) | Rutin, ritonavir, emetine, hesperidin, indinavir | Accelerated peer review (9 days) |

| Elfiky [109] | MD simulation + docking on representative structures | 31 compounds with known antiviral activity or in clinical trials + physiological nucleotides + negative controls | RNRP (homology model: template 6NUR) | Setrobuvir, ID-184, YAK | Accelerated peer review (7 days) |

| Elmezayen et al. [117] | Virtual screening + Docking + in silico prediction of ADMET profile + MD for top-ranked compounds + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | ZINC15 drug-like database (30,000 compound) + Drug Database (4,500 approved compounds from ChEMBL, DrugBank and Selleckchem) | Multitarget:Main protease (PDB: 6LU7);TMPRSS2 enzyme (homology model; template: 2OQ5) | Main protease: Talampicillin, lurasidone; TMPRSS2: Rubitecan, loprazolam | Accelerated peer review (13 days) |

| Gyebi et al. [75] | Docking + in silico ADMET analysis | 632 bioactive alkaloids and 100 terpenoids from African medicinal plants | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | 10-Hydroxyusambarensine, Cryptoquindoline, 6-Oxoisoiguesterin, 22-Hydroxyhopan-3-one, | Accelerated peer review (6 days) |

| Islam et al. [77] | Docking with 2 approaches + MD simulations on top 5 compounds + in silico ADMET | 40 phytochemicals with known antiviral properties against other viruses | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Baicalin, cyanidin-3-glucoside, alpha-ketoamide-11r | Accelerated peer review (5 days) |

| Kandeel et al. [112] | Docking + MD simulation of top 10 hits + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | 1697 clinical FDA-approved drugs from Selleckchem Inc. | PL protease (PDB: 6W9C) | Phenformin, quercetin, ritonavir | Accelerated peer review (6 days) |

| Khan et al. [80] | Docking + MD simulations of the top 5 compounds + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | In-house database of natural and synthetic molecules (>8000 compounds) along with 16 FDA-approved antiviral drugs | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Saquinavir, Remdesivir, Darunavir, flavone-derivative, coumarin-derivative | Accelerated peer review (14 days) |

| Lobo-Galo et al. [84] | Docking | Thiol-reacting FDA-approved drugs | Main protease (PDB:6LU7) | Disulfiram | Accelerated peer-review (14 days) |

| Muralidharan et al. [87] | Docking + MD simulations | Combination of Lopinavir, Oseltamivir, ritonavir | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | The three drugs have a stronger binding energy against main protease than each of the drug individually | Accelerated peer review (13 days) |

| Pant et al. [90] | Docking + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) + MD simulations | 700 compounds from ZINC and ChEMBL databases, 4100 compounds from DrugBank, 300 compounds from various databases, 66 compounds from FDA-approved drugs | Main protease (PDB: 6Y2F, 6W63) | Cobicistat, ritonavir, lopinavir, darunavir (FDA-approved drugs) | Accelerated peer review (8 days) |

| Shah et al. [12] | Docking | 61 molecules already used in clinics or under clinical scrutiny as antiviral agents | Main protease (PDB: 5R7Y,5R7Z, 5R80, 5R81, 5R82) | Lopinavir, Asunaprevir, Remdesivir, Indinavir, ritonavir, CGP42112A, ABT450, Marboran, galidesivir interact with >2 protein structures | Accelerated peer review (13 days) |

| Sinha et al. [120] | Docking | 23 Saikosaponins (traditional chinese medicine compounds) | Multitarget: Spike (PDB: 6VSB); nsp15 (PDB: 6W01); | Saikosaponin V (nsp15); saikosaponin U (spike) | Accelerated peer review (11 days) |

| Tazikeh-Lemeski et al. [115] | Structural score similarity + docking with 3 methods + MD simulations for raltegravir, maraviroc and sinefungin | 5 ligands similar to S-adenosylmethionine and sinefungin from 1516 FDA-approved drugs + maraviroc, raltegravir, favipiravir and prednisolone | RNA methyltransferase (nsp-16) (PDB: 6WH4) | Raltegravir, maraviroc | Accelerated peer review (15 days) |

| Wu et al. [122] | Docking | 78 antiviral drugs extracted from ZINC drug database (2924 compounds) and an in-house natural product database (1066 compounds) | Multitarget: Homology models of 18 SARS-CoV-2 proteins + 2 human targets | Representative hits: PLpro: ribavirin; Main protease: lymecycline; RdRp: valganciclovir; Spike: rescinnamine | Accelerated peer review (6 days) |

The results of most structure-based studies on drug repurposing against COVID-19 pandemic are summarized in Tables 3, 4 and 5. This list does not pretend to be exhaustive, given the speed by which new articles on these subjects are published.

Table 3.

Structure-based approaches for drug repurposing targeting main protease (Mpro)

| Reference | Method | Starting dataset | Target | Possible repurposing drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alamri et al. [68] | Covalent docking screening + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) + MD on the most promising hits for AFCL compounds; docking for FDA-approved library + MD on the most promising hits + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | 1000 compounds from Asinex Focused Covalent library and 116 anti-viral compounds from FDA-approved protease inhibitor library from PubChem | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Several covalent inhibitors + paritaprevir, simeprevir |

| Al-Khafaji et al. [16] | Covalent docking screening + MD on the top three hits | FDA-available covalent drugs | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Saquinavir, ritonavir, remdesivir, delavirdine, cefuroxime, oseltamivir, prevacid |

| Ancy et al. [69] | Docking + MD + free energy calculations | TMB607, TMC310911 (anti HIV-1 protease in clinical trials) | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | TMB607 |

| Bharadway et al. [71] | Docking + MD simulations | Doxycycline, tetracycline, demeclocycline, minocycline | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Doxycycline, minocycline |

| Fischer et al. [73] | Shape screening + 2 docking protocols + in silico prediction of ADMET profile + MD for top- ranked compounds (144 for full database + 38 for high-MW database) + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | ZINC database (>606,000,000 compounds) + ZINC database with MW > 500 g/mol (1,400,000 compounds) + commercially available HIV-hepatitis C antivirals from PubChem | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Apixaban, Nelfinavir, glecaprevir |

| Gimeno et al. [74] | Consensus docking + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | Drug3D (1930 FDA-approved drugs and active metabolites with MW <2000 Da) + Reaxys-marketed library (4536 drugs marketed) | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Perampanel,Carprofen,Celecoxib,Alprazolam, Trovafolxacin, Sarafloxacin, Ethyl biscoumacetate |

| Hage-Melim et al. [76] | in silico prediction of ADMET profile + Docking | SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Targeted Library (1017 compounds) + ML SARS Targeted Library (1577 compounds) | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Apixaban |

| Jimenez-Alberto et al. [78] | Docking + MD simulations on top 10 compounds + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | ZINC15 ” world” subset (4384 molecules approved for human use in major jurisdictions) | Main protease (homology model; templates: 2AMD, 1WOF, 2AMQ, 2D2D, 3E91, and 3EA7) | Daunorubicin, ergotamine, bromocriptine, meclocycline, amrubicin, ergoloid, ketotifen-N-glucuronide, N-trifluoroacetyladriamycin, 5a-reductase-inhibitor |

| Jin et al. [27] | Docking + High-throughput in vitro screening + cell-based assays | In house database of >10,000 potential binding compounds including approved drugs, drug candidates in clinical trials and other pharmacologically active compounds | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Cinanserin (by docking), disulfiram, carmofur, ebselen, shikonin, tideglusib, PX-12 (by HTS) |

| Kandeel and Al-Nazawi [79] | Docking | FDA-approved drugs from Selleckchem | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Chromocarb, ribavirin, telbivudine, vitamin B12, aminophylline, nicotinamide, triflusal, bemegride, aminosalicylate, pyrazinamide, temozolomide, methazolamide, tioxolone, propylthiouracil, cysteamine, methoxamine, zonisamide, octopamine, amiloride |

| Koulgi et al. [81] | Direct docking + ensemble docking | FDA-approved drug database + SWEETLEAD database | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Indinavir, ivermectin, cephalosporin-derivatives, neomycin, amprenavir |

| Kumar et al. [82] | Docking + MD simulations on top 3 compounds | FDA-approved antiviral, anticancer and anti-malarial drugs from PubChem (>75 compounds) | Main protease (PDB: 6Y2F) | Lopinavir, Ritonavir, Tipranavir |

| Liu et al. [83] | Docking SCAR protocol for covalent and non-covalent drugs | ZINC15 ” in trials” catalog (5811 approved or investigational drugs worldwide) | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Itacinitib, Oberadilol, Telcagepant, Vidupiprant, Pilaralisib, Poziotinib, Fastamatinib, CL-275838, Ziprasidone, Folinic acid, ITX5061 |

| Lokhande et al. [85] | Docking + MD simulations for lead antiviral and FDA-approved compounds + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | 348 antiviral compounds and 2454 FDA-approved drugs from Selleckchem and DrugBank | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Mitoxantrone, leucovorin, birinapant, dynasore |

| Mittal et al. [86] | MD on apo/holo protein + docking + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) | Drugs from Selleckchem (227 protease inhibitors), DrugBank and Repurposing hub (13947 compounds) | Main protease (PDB: 6M03, 6LU7) | Leupeptin hemisulfate, pepstatin A, nelfinavir (protease inhibitors); Birinapant, Lypressin, Octreotide (other drugs) |

| Nutho et al. [88] | Docking + MD simulations + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) + pair interaction energy analysis | Lopinavir, ritonavir | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Ritonavir may have a greater inhibitory efficiency against main protease than lopinavir |

| Olubiyi et al. [89] | Ensemble docking | Over one million compounds including approved drugs, investigational drugs, natural products and organic compounds | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, steroid hormones |

| Sencaski et al. [91] | Docking | 57 selected molecules from DrugBank database | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Ciclesonide, raltegravir, tolvaptan, mezlocillin, camazepam, spirapril, bacampicillin, carbinoxamine, paromomycin, phensuximide, cefotiam, voriconazole, tobramycin, kanamycin, ospemifene, propylthiouracil, oseltamivir |

| Shamsi et al. [92] | Docking | FDA-approved drugs (2388 compounds) | Main protease (PDB: 6M03) | Glecaprevir, Maraviroc |

| Tsuji [93] | Combined docking | Compounds extracted from ChEMBL database (1,485,144 compounds), | Main protease (PDB: 6Y2G) | 64 potential drugs (11 approved, 14 clinical and 39 preclinical). Selected hits: Eszopiclone, sepimostat, curcumin, |

| ul-Qamar et al. [94] | Docking + MD simulations of the top 3 compounds | In-house library of 32,297 potential antiviral phytochemicals and traditional Chinese medicinal compounds | Main protease (homology model; template PDB: 3M3V) | 5,7,3’,4’-tetrahydroxy-2’-(3,3-dimethylallyl) isoflavone, myricitrin, and methyl rosmarinate |

| Wang et al. [95] | Docking + MD simulations for top docking hits + free energy calculations (MM-PBSA-WSAS) | 2201 approved drugs from DrugBank | Main protease (PDB: 6LU7) | Carfilzomib, Eravacycline, Valrubicin, Lopinavir, Elbasvir |

Table 4.

Structure-based approaches for drug repurposing targeting other viral proteins

| Reference | Method | Starting dataset | Target | Possible repurposing drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abo-Zeid et al. [98] | Docking | FDA-approved iron oxide nanoparticle | Spike receptor binding domain (PDB: 6VW1) | Fe O O and Fe and Fe O O

|

| Aftab et al. [106] | Docking first on known antiviral drugs, then on 1061 compounds from PubChem database, structurally similar to galidesivir | Ribavirin, penciclovir, nitazoxanide, nafamostat, chloroquine, galidesivir, favipiravir, interferon, remdesivir, sofosbuvir | RdRp (homology model: template: 6NUR) | Remdesivir, galidesivir, ribavirin, sofosbuvir |

| Ahmad et al. [107] | Docking | 7922 FDA-approved drugs from NPC database | RdRp (PDB: 6M71) | Ornipressin, Lypressin, Examorelin, Polymixin B1 |

| Choudhury et al. [108] | Docking | 30 compounds from literature, known or predicted as RdRp inhibitors | RdRp (PDB: 6M71) | Remdesivir, chlorhexidine |

| de Oliveira et al. [99] | MD simulation of the protein + docking + MD for top 3 candidates + free energy calculations (MM-PBSA) | 9091 FDA-approved drugs | Spike (starting structure not available in PDB) | Ivermectin + traditional herbal isolates |

| Drew and Janes [100] | Pocket identification + docking with 3 software | 1049 compounds from Drugs-lib dataset from MTIOpenScreen | Spike (PDB: 6VSB) | 100 top compounds, of which 20 anti-inflammatory drugs and 15 drugs approved for pulmonary diseases. |

| Durdagi [104] | Docking + short (10 ns) MD simulations of top 50 hits + free energy calculations (MM-GBSA) + long (100 ns) MD simulations of top 3 hits | 6654 small molecules from NPC library, including FDA-approved drugs and compounds in clinical trials | TMPRSS2 (homology model; template PDB 5CE1) | Benzquercin, difebarbamate, N-benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-PABA |

| Encinar and Menendez [114] | Docking + MD simulations of high-scoring compounds + free energy calculations (MM-PBSA) | About 9000 FDA-approved investigational and experimental drugs from DrugBank repository | RNA cap 2’-O-methyltransferase nsp16/nsp10 protein complex (PDB: 6W4H) | Tegobuvir, sonidegib, siramesine, antrafenine, bemcentinib, itacitinib, phthalocyanine |

| Fantini et al. [101] | MD simulation of Spike + ganglioside | Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine | Spike (PDB: 6VSB) | Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine can interfere with the binding of spike on the host cells |

| Feng et al. [102] | Docking + in silico prediction of ADMET profile for top 100 compounds + in vitro verification | Molecules in FDA-approved drug library (1234 selected compounds) | Spike (models obtained via either template-based approaches (templates: 5WRG, 6U7H, 6CRV, and 6LZG) and template-free approaches | Eltrombopag |

| Singh et al. [105] | Binding pocket prediction + docking with different approaches | Approx. 14,600 approved, investigational and experimental drugs from different repositories | TMPRSS2 (homology model; template PDB: 6O1G) | 156 molecules can bind to catalytic site of TMPRSS2 and 100 molecules on the exosite |

| Wei et al. [103] | Docking+ MD simulation + free energy calculations (MM-PBSA) on the top compound of each dataset | 2191 FDA-approved drugs from DrugBank and 13,026 natural compounds from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology | Spike (PDB: 6LZG) | Digitoxin, bisindigotin, raltegravir |

| Yadav et al. [113] | Docking + free energy calculations + in silico ADMET screening for top 7 inhibitors + MD simulation for top 3 inhibitors | 8722 antiviral compounds from Asinex Elite database + 265 FDA-approved drugs for infectious diseases from PubChem | Nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (PDB: 6VYO) | zidovudine |

Table 5.

Structure-based approaches for drug repurposing targeting simultaneously different proteins

| Reference | Method | Starting dataset | Target | Possible repurposing drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexpandi et al. [124] | Docking + in silico ADMET analysis | 113 quinoline drugs from DrugBank database | Multitarget: Main protease (PDB: 6LU7); spike (PDB: 6M17) and human ACE2 domain (PDB: 1R4L); RdRp (homology model, template not known) | For main protease: rilapladib, saquinavir, oxolinic acid, elvitegravir, For RdRp: elvitegravir, oxolinic acid, saquinavir, For the interaction between spike and human ACE2: rilapladib |

| Ekins et al. [116] | Docking with 3 different programs | For main protease: FDA-approved HIV-1 protease inhibitors and hepatitis C NS3/4A protease inhibitors (16 compounds).For spike: FDA-approved drugs (ca. 2400 molecules) | Multitarget: Main protease (PDB: 6LU7); Spike (homology model; template 2AJF) | For main protease: azatanavir, lopinavir. For spike: Rizatriptan, dasabuvir, pravastatin, empagliflozin |

| Hijikata et al. [121] | Structural comparison of ligands with known ligands of homologs of SARS-CoV-2 proteins | 8085 drugs from KEGG and DrugBank databases + 5780 metabolites from KNApSAcK database | Multitarget: Homology models of 17 SARS-CoV-2 proteins + 2 human targets refined by MD | Representative hits: Main protease: Magnesium pidolateNsp16: sinefunginACE: enalaprilat |

| Iftikhar et al. [118] | Iterative docking with the selected SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins + 100 irrelevant proteins of diverse classes to detect non-specific interactions | Starting from a library of 4512 compounds containing FDA-approved drugs against these viral proteins, 46 and 35 compounds were shortlisted against Mpro, RdRp and helicase. 62 FDA-approved antiviral drugs were also added | Multitarget: Main protease (PDB: 6LU7); RdRp (homology model; template not known); Helicase (homology model; template not known) | Main protease: rimantadine, bagrosin, grazoprevir. RdRp: casopitant. Helicase: meclonazepam, oxiphenisatin |

| Mahdian et al. [123] | Docking | 2471 FDA-approved drugs from DrugBank | Mutitarget: Main protease, PLpro, cleavage site, HR1 and RBD domain of spike protein (all homology models: templates not known), and TMPRSS2 (homology model, template not known) | For all tested target proteins: glecaprevir, paritaprevir, simeprevir, ledipasvir, glycyrrhizic acid, TMC-310911, and hesperidin |

| Zhang et al. [119] | In silico ADMET + docking | 115 natural compounds known for anti-SARS or anti-MERS activity extracted from literature screening or Chinese herbal database | Multitarget: Homology models of Mpro, Spike and PLpro (templates: 1UJ1, 6CAD and 5E6J, respectively) | 13 compounds, 11 of which targeting Mpro, 7 targeting PLpro, 1 targeting spike |

Most studies were focused to predict the ability of known drugs to bind SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [67–95]. However, little agreement is present among the potential candidates identified by these different studies. A possible reason could be the diversity of the selected starting databases and of the algorithms used in docking and virtual screening. Furthermore, a study on the structural properties of Mpro [96] found deep differences in the shape and size of the active sites of this protease with respect to SARS-CoV protease, suggesting that the repurposing of SARS drugs for COVID-19 may be ineffective. Most of the hits discovered in these studies belong to few classes of drugs: antiretrovirals, antineoplastic, antimalarial, immunomodulators, nucleotide inhibitors, protease inhibitors, ri-bonucleoside inhibitors and steroid hormones.

Another main target for drug-repurposing studies is spike protein (Supplementary Figure 2), which confers to the virus its ”crown” appearance and facilitates the binding with host ACE2 receptor, thus allowing the virus to enter the host cell [23, 24, 97]. Several studies were conducted targeting this protein [98–103]. In general, this protein has been proved a more difficult target than Mpro, and few drugs have been found. The article by Feng and coworkers [102], focused on the search for ligands of spike into a database of FDA-approved drugs, is the only one that provided an in vitro validation of the results, showing that eltrombopag, a non-peptide thrombopoietin receptor agonist, has a Kd for human ACE2 extracellular domain of 8.275 10

10 M and can also bind the S2 domain of spike protein with a Kd in the micromolar range. Therefore, this drug is potentially able to impair viral entrance in host cells. Two articles [104, 105] performed virtual screening on the homology model of the structure of human TMPRSS2, which facilitates cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 through the spike protein, and predicted benzquercin as the most promising hit for this protease.

M and can also bind the S2 domain of spike protein with a Kd in the micromolar range. Therefore, this drug is potentially able to impair viral entrance in host cells. Two articles [104, 105] performed virtual screening on the homology model of the structure of human TMPRSS2, which facilitates cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 through the spike protein, and predicted benzquercin as the most promising hit for this protease.

Studies for drugs impairing other macromolecular targets of SARS-CoV-2 are more scarce. RdRp was the focus of few studies [106–109]. In some cases, the authors reported that antivirals targeting RdRp of other viruses (HCV, MERS and SARS) such as sofosbuvir and remdesivir could bind and stop the activity of this protein. A recent clinical trial did not confirm the activity of remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2 [110] but other studies suggested that this drug can shorten the time to recovery in some patients [111]. On this basis, FDA issued an emergency use authorization for remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 patients hospitalized with severe disease. PLpro (Supplementary Figure 3) was the molecular target of a study [112] to evaluate the repositioning of FDA-approved antivirals, antibiotics, anthelmintics, antioxidants and cell protectives. Another study [113] predicted that zidovudine, an anti-HIV agent, could be able to bind to nucleocapsid protein (Supplementary Figure 4). Another article [114] targeted three differential traits of the intermolecular interactions of the RNA cap 2’-O-methyltransferase nsp16/nsp10 protein complex (Supplementary Figure 5), i.e. the (nsp10-stabilized) SAM-binding pocket of nsp16, the (nsp10-extended) RNA-binding groove of nsp16 and the unique nsp16/nsp10 interaction interface required by nsp16 to execute its enzymatic activity. Also, another study [115] applied structure-based drug repurposing to nsp16.

Multitarget studies were also performed. Starting from a strategy already developed against Ebola and Zika viruses, and considering compounds with in vitro activity against SARS and MERS, drug repurposing has been applied on the structures of spike+ACE2 interface and Mpro [116]. Other studies focused on the structures of the following targets: Mpro and TMPRSS2 [117]; RdRp, Mpro and helicase [118]; and Mpro, spike and PLpro [119]. Other authors [120] focused the study on the prediction of the interaction of saikosaponins (components of traditional Chinese medicine) with spike and nsp15. In two articles, the authors modelled all the proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and performed screening against all these targets. The 1st article compared the structures of known ligands of the templates used to model SARS-CoV-2 proteins to a dataset of drugs and active metabolites [121], whereas the 2nd article used these models to perform docking of a selected group of FDA-approved antiviral compounds and a library of natural compounds [122]. In their study, Mahdian and coworkers modelled five target proteins of SARS-CoV-2 (Mpro, PLpro, cleavage site, HR1 and RBD in Spike protein) and screened FDA-approved drugs against them [123]. Another multitarget study focused on quinolin-based inhibitors [124].

Most of these structure-based repurposing studies included in the library of compounds tested also treatments that gained attention not only to the scientific community. In particular, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, two old antimalarial drugs [125], and lopinavir and ritonavir, two anti-AIDS drug introduced in the therapy against SARS-CoV-2 [126] were predicted to bind several SARS-CoV-2 proteins. However, no benefit was observed with lopinavir–ritonavir treatment with respect to standard care in a randomized, controlled, open-label trial involving hospitalized adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection [127], and the utility of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 is still questioned [128, 129]. An additional contribution to the structure-based approach of drug repurposing was given by researchers that developed freely accessible Web servers to predict targets and for multi-target- and multi-site-based virtual screening. One example is D3Targets-2019-nCoV (https://www.d3pharma.com/D3Targets-2019-nCoV/index.php), which contains 20 viral proteins and 22 human proteins involved in virus infection, replication and release, with 69 different conformations and 557 potential ligand-binding pockets [130]. Other Web servers are available but not (yet) associated to peer-reviewed publications.

AI-based approaches

AI researchers are very active to fight COVID-19 effects, but few papers are concerning drug repurposing. In addition, although some of them have been written and publicly available, we found only few papers accepted for publication and online available on a journal, also if subjected to an accelerated peer-review process. In [131] authors proposed a deep learning approach for searching marketed drugs potentially with antiviral activities against coronaviruses. The system was proposed to quickly screen a large number of compounds with assigned learning datasets to find those with potential activities inhibiting SARS-CoV-2. An in vitro cell model for feline coronavirus replication was set up to evaluate the AI-identified drugs for antiviral activity verification.

The systems was integrated with a feedback from antiviral activities by a cell-based FIP virus replication assay and the retrained AI model was established to screen further and again verified by the FIP virus replication assay. In [132] authors used a previously trained deep learning-based drug–target interaction prediction model, called Molecule Transformer-Drug Target Interaction (MT-DTI) [133] to identify commercially available antiviral drugs that could potentially disrupt SARS-CoV-2 viral components, such as proteinase, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and/or helicase. Since the model utilizes simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings and amino acid (AA) sequences, which are 1D string inputs, it is possible to quickly apply target proteins that do not have experimentally confirmed 3D crystal structures, such as viral proteins of SARS-CoV-2. To train the model, the Drug Target Common (DTC) database [134] and BindingDB [135] database were manually curated and combined. After the MT-DTI prediction, the raw prediction results were screened for antiviral drugs that are FDA approved and target viral proteins. To confirm the performance of MT-DTI at least in silico, authors compared the binding affinities of 3,410 FDA-approved drugs predicted by MT-DTI to those estimated by AutoDock Vina (a widely used 3D structure-based docking algorithm) [136]. The problem here is that the two models did not obtained exactly comparable results and then because a ground truth or in vivo experiments are necessary to confirm in-vitro hypotheses. On the other hand, the AI community is giving additional contributions to fighting COVID-19 by developing freely accessible Web servers and resources, as in the case of the CLAIRE Innovation Network, composed of 381 laboratories and institutions working in Europe in the area of AI (https://covid19.claire-ai.org/). In this context, also drug repositioning is one of the research topics by making available both data and computing facilities to interested researchers.

Conclusions

Drug repositioning is a field of drug research whose importance has been increasing in the past years, due to several advantages, such as the possibility to shorten the clinical trials, the extension of the life of an old drug by finding a new therapeutic target and the discovery of often-unknown relationships among apparently distant diseases. The urgency to find drugs to face COVID-19 pandemic has tremendously pushed this kind of research in the past months. Computational approaches has played and still play a major role to search weapons effective against SARS-CoV-2 virus among the arsenal of drugs available today, but to date, the results do not appear to live up to expectations. Judging by the literature, a major role in this race against time was played by structural bioinformatics, whose contribution was made possible also by the unprecedented speed with which the structures of the most important viral proteins were made available. However, many results of these studies appear not fully convincing. Very few studies on the same target converge on the same drugs, very few give an unquestionable evidence of an effect and almost none gives an experimental validation. Furthermore, many studies predict the effectiveness of discussed drugs that failed to demonstrate their efficacy in clinical trials.

We noticed that speed is the common feature of these studies. A proverb says: ”haste makes waste”, and what is true for popular wisdom is doubly true for scientific research, which needs time to carefully design a good experiment (irrespective if in wet laboratory or in silico), time to carefully perform it and, especially, time to carefully understand the results. Moreover, publications have also often been evaluated hastily, as it has been well explained in a work published by Palayew and coworkers [137]. We agree with their concerns and with their comment: ”Although the nature of this emergency warrants accelerated publishing, measures are required to safeguard the integrity of scientific evidence”. It is true that the world is struggling desperately to find a drug against SARS-CoV-2 as soon as possible, but science must resist the temptation to jump the gun and pursue the goal with the same rigor as ever.

On the other hand, AI-based and network-based approaches probably made a smaller contribution to the field of drug repurposing than would have been expected. Possibly, the reason is that these methods are based on knowledge, and at present we do not have a sufficient critical mass of knowledge about an organism whose existence was unknown until less than a year ago. This demonstrates the importance of basic research, often underestimated, as an indispensable substrate for the growth of knowledge essential for the development of research applied to biomedicine. Despite everything, the computationally based drug-repositioning approaches applied to COVID-19 have made it possible to highlight some drugs that would be worth testing into COVID-19 therapy, most of which are in the same therapeutic area of their current registered use, therefore their probability of success is high [14]. We are confident that they will be able to make an even more important contribution to win this battle against COVID-19 in the future.

Key points

Drug repurposing is an approach that has been proven effective to find drug against diseases.

The urgency of a pandemic condition may benefit of the drug-repurposing approach, thanks to the already available approvals for using in humans.

Critical aspects in the application of drug repurposing are the availability of data suitable to apply AI methods and the time needed for a careful evaluation of results before approving for publication.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was partly supported by ELIXIR IT research infrastructure project, the Italian Ministry of University and Research, FFABR 2017 program and PRIN 2017 program (grant number 2017483NH8 to A.M.).

Dr. Serena Dotolo is a post-doctoral researcher in the group of Prof. Roberto Tagliaferri at the University of Salerno. She is actively involved in the study of protein-protein networks by means of bioinformatics to identify new molecular targets for the development of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches of complex diseases.

Prof. Anna Marabotti is an Associate Professor of the University of Salerno. Her main research focus is the analysis and prediction of structures and structure-function-dynamics relationships of proteins involved in rare diseases, and the development of new therapies using computational biology approaches.

Dr. Angelo Facchiano is a senior researcher at the Institute of Food Sciences, CNR Italy. His research interests include biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology, bioinformatics and computational biology.

Prof. Roberto Tagliaferri is a Full Professor at the University of Salerno. His research interests include Artificial Intelligence, Statistical Pattern Recognition, Clustering, Biomedical imaging and Bioinformatics.

Contributor Information

Serena Dotolo, University of Salerno.

Anna Marabotti, University of Salerno.

Angelo Facchiano, Institute of Food Sciences, CNR Italy.

Roberto Tagliaferri, Artificial Intelligence, Statistical Pattern Recognition, Clustering, Biomedical imaging and Bioinformatics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare to have not any conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Jin G, Wong ST. Toward better drug repositioning: prioritizing and integrating existing methods into efficient pipelines. Drug Discov Today 2014; 19:637–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shameer K, Readhead B, Dudley JT. Computational and experimental advances in drug repositioning for accelerated therapeutic stratification. Curr Top Med Chem 2015; 15:5–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun P, Guo J, Winnenburg R, et al. Drug repurposing by integrated literature mining and drug-gene-disease triangulation. Drug Discov Today 2017; 22:615–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gns HS, Gr S, Murahari M, et al. An update on Drug Repurposing: Re-written saga of the drugs fate. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 110:700–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Talevi A, Bellera CL. Challenges and opportunities with drug repurposing: finding strategies to find alternative uses of therapeutics. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2020; 15:397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Oliveira EA, Karen LL. Drug repositioning: concept, classification, methodology, and importance in rare/orphans and neglected diseases. J Appl Pharm Sci 2018; 8:157–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilkinson GF, Pritchard K. In vitro screening for drug repositioning. J Biomol Screen 2015; 20:167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hernandez JJ, Pryszlak M, Smith L, et al. Giving drugs a second chance: overcoming regulatory and financial hurdles in repurposing approved drugs as cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol 2017; 7:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanoli Z, Seemab U, Scherer A, et al. Exploration of databases and methods supporting drug repurposing: a comprehensive survey. Brief Bioinform 2020; bbaa003 Published online ahead of print, 14 February 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Xue H, Li J, Xie H, et al. Review of drug repositioning approaches and resources. Int J Biol Sci 2018; 14:1232–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iorio F, Rittman T, Ge H, et al. Transcriptional data: a new gateway to drug repositioning? Drug Discov Today 2013; 18:350–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shah B, Modi P, Sagar SR. In silico studies on therapeutic agents for COVID-19: Drug repurposing approach. Life Sci 2020; 252:117652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan RJ, Jha RK, Amera GM, et al. Targeting SARS-CoV-2: a systematic drug repurposing approach to identify promising inhibitors against 3C-like proteinase and 2-O-ribose methyltransferase. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–14. Published online ahead of print, 20 April 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neuberger A, Oraiopoulos N, Drakeman DL. Renovation as innovation: is repurposing the future of drug discovery research? Drug Discov Today 2019; 24:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J, Zheng S, et al. A survey of current trends in computational drug repositioning. Brief Bioinform 2016; 17:2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al-Khafaji K, Al-Duhaidahawi D, Taskin TT. Using integrated computational approaches to identify safe and rapid treatment for SARS-CoV-2. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–9. Published online ahead of print, 15 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park K. A review of computational drug repurposing. Transl Clin Pharmacol 2019; 27:59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lippmann C, Kringel D, Ultsch A, et al. Computational functional genomics-based approaches in analgesic drug discovery and repurposing. Pharmacogenomics 2018; 19:783–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xue H, Li J, Xie H, et al. Review of drug repositioning approaches and resources. Int J Biol Sci 2018; 14:1232–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker NC, Ekins S, Williams AJ, et al. A bibliometric review of drug repurposing. Drug Discov Today 2018; 23:661–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pawar AY. Combating devastating COVID-19 by drug repurposing. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 56:105984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dashraath P, Wong JLJ, Lim MXK, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020; 222:521–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven prote-ase inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181:271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020; 367:1444–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Millet JK, Whittaker GR. Host cell proteases: Critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015; 202:120–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shirato K, Kawase M, Matsuyama S. Wild-type human coronaviruses prefer cell-surface TMPRSS2 to endosomal cathepsins for cell entry. Virology 2018; 517:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 2020; 582:289–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Naqvi AAT, Fatima K, Mohammad T, et al. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020; 1866:165878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guzzi PH, Mercatelli D, Ceraolo C, et al. Master Regulator Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2/Human Interactome. J Clin Med 2020; 9:982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020; 583:459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of corona-virus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 2020; 109:102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jin Y, Yang H, Ji W, et al. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of COVID-19. Viruses. 2020; 12: 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li J, Lu C, Jiang M, et al. Traditional chinese medicine-based network pharmacology could lead to new multicompound drug discovery. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012; 2012:149762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou Y, Hou Y, Shen J, et al. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov 2020; 6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fan HH, Wang LQ, Liu WL, et al. Repurposing of clinically approved drugs for treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in a 2019-novel coronavirus-related coronavirus model. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020; 133:1051–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fakhraei S, Huang B, Raschid L, et al. Network-based drug-target interaction prediction with probabilistic soft logic. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 2014; 11:775–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Re M, Valentini G. Network-based drug ranking and repositioning with respect to DrugBank therapeutic categories. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 2013; 10:1359–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen H, Zhang H, Zhang Z, et al. Network-based inference methods for drug repositioning. Comput Math Methods Med 2015; 2015:130620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li J, Lu Z. Pathway-based drug repositioning using causal inference. BMC Bioinformatics 2013; 14 Suppl 16:S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ye H, Liu Q, Wei J. Construction of drug network based on side effects and its application for drug repositioning. PLoS One 2014; 9:e87864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tu YF, Chien CS, Yarmishyn AA, et al. A review of SARS-CoV-2 and the ongoing clinical trials. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barlow A, Landolf KM, Barlow B, et al. Review of emerging pharmacotherapy for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019. Pharmacotherapy 2020; 40:416–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Messina F, Giombini E, Agrati C, et al. COVID-19: viral-host interactome analyzed by network based-approach model to study pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Transl Med 2020; 18:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sadegh S, Matschinske J, Blumenthal DB, et al. Exploring the SARS-CoV-2 virus-host-drug interactome for drug repurposing. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. King AD, Przulj N, et al. Protein complex prediction with RNSC. Methods Mol Biol. 2012; 804:297–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Macropol K, Can T, Singh AK. RRW: repeated random walks on genome-scale protein networks for local cluster discovery. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma C-Y, Chen Y-PP, Berger B, et al. Identification of protein complexes by integrating multiple alignment of protein interaction networks. Bioinformatics 33: 1681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nepusz T, Yu H, Paccanaro A. Detecting overlapping protein complexes in protein-protein interaction networks. Nat Methods 2012; 9:471–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bader GD, Hogue CWV. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2003; 4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luo H, Wang J, Li M, et al. Drug repositioning based on comprehensive similarity measures and Bi-Random walk algorithm. Bioinformatics 32(17): 2664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vanunu O, Magger O, Ruppin E, et al. Associating Genes and Protein Complexes with Disease via Network Propagation. PLoS Comput Biol 2010; 6:e1000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martínez V, Navarro C, Cano C, et al. DrugNet: network-based drug-disease prioritization by integrating heterogeneous data. Artif Intell Med 2015; 63:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pinzi L, Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20:4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kumar S, Kumar S. Molecular docking: a structure-based approach for drug repurposing. In: In Silico Drug Design. Repurposing Techniques and Methodologies, 2019. Roy K, ed. pp. 161–189. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cavasotto CN. Homology models in docking and high-throughput docking. Curr Top Med Chem 2011; 11:1528–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berman HM, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Announcing the worldwide Protein Data Bank. Nat Struct Biol 2003; 10: 980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alonso H, Bliznyuk AA, Gready JE. Combining docking and molecular dy-namic simulations in drug design. Med Res Rev 2006; 26:531–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sterling T, Irwin JJ. ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone. J Chem Inf Model 2015; 55:2324–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, et al. PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47:D1102–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018; 46:D1074–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Douguet D. Data sets representative of the structures and experimental properties of FDA-approved drugs. ACS Med Chem Lett 2018; 9:204–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Siramshetty VB, Eckert OA, Gohlke BO, et al. SuperDRUG2: a one stop resource for approved/marketed drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 2018; 46:D1137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mendez D, Gaulton A, Bento AP, et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47:D930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, et al. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Labbé CM, Rey J, Lagorce D, et al. MTiOpenScreen: a web server for structure-based virtual screening. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:W448–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Corsello SM, Bittker JA, Liu Z, et al. The Drug Repurposing Hub: a next-generation drug library and information resource. Nat Med 2017; 23:405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Aanouz I, Belhassan A, El-Khatabi K, et al. Moroccan medicinal plants as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Computational investigations. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–9. Published online ahead of print, 6 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Alamri MA, Tahir Ul Qamar M, Mirza MU, et al. Pharmacoinformatics and molecular dynamics simulation studies reveal potential covalent and FDA-approved inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease 3CLpro. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–13. Published online ahead of print, 24 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ancy I, Sivanandam M, Kumaradhas P. Possibility of HIV-1 protease inhibitors-clinical trial drugs as repurposed drugs for SARS-CoV-2 main protease: a molecular docking, molecular dynamics and binding free energy simulation study. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–8. Published online ahead of print, 6 July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Arun KG, Sharanya CS, Abhithaj J, et al. Drug repurposing against SARS-CoV-2 using E-pharmacophore based virtual screening, molecular docking and molecular dynamics with main protease as the target. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–12. Published online ahead of print, 22 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bharadwaj S, Lee KE, Dwivedi VD, et al. Computational insights into tetracyclines as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro via combinatorial molecular simulation calculations. Life Sci 2020; 257:118080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Das S, Sarmah S, Lyndem S, et al. An investigation into the identification of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease using molecular docking study. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–11. Published online ahead of print, 13 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fischer A, Sellner M, Neranjan S, et al. Potential Inhibitors for Novel Coronavirus Protease Identified by Virtual Screening of 606 Million Compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gimeno A, Mestres-Truyol J, Ojeda-Montes MJ, et al. Prediction of novel inhibitors of the main protease (M-pro) of SARS-CoV-2 through consensus docking and drug reposition. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gyebi GA, Ogunro OB, Adegunloye AP, et al. Potential inhibitors of corona-virus 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro): an in silico screening of alkaloids and terpenoids from African medicinal plants. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–13. Published online ahead of print, 18 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hage-Melim LIDS, Federico LB, de Oliveira NKS, et al. Virtual screening, ADME/Tox predictions and the drug repurposing concept for future use of old drugs against the COVID-19. Life Sci 2020; 256:117963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Islam R, Parves MR, Paul AS, et al. A molecular modeling approach to identify effective antiviral phytochemicals against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–12. Published online ahead of print, 12 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jiménez-Alberto A, Ribas-Aparicio RM, Aparicio-Ozores G, et al. Virtual screening of approved drugs as potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Comput Biol Chem 2020; 88:107325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kandeel M, Al-Nazawi M. Virtual screening and repurposing of FDA ap-proved drugs against COVID-19 main protease. Life Sci 2020; 251:117627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Khan SA, Zia K, Ashraf S, et al. Identification of chymotrypsin-like protease inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 via integrated computational approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–10. Published online ahead of print, 13 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Koulgi S, Jani V, Uppuladinne M, et al. Drug repurposing studies targeting SARS-CoV-2: an ensemble docking approach on drug target 3C-like protease (3CLpro). J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–21. Published online ahead of print, 17 July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kumar Y, Singh H, Patel CN. In silico prediction of potential inhibitors for the Main protease of SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking and dynamics simulation based drug-repurposing. J Infect Public Health 2020;: S1876–0341 30526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liu S, Zheng Q, Wang Z. Potential covalent drugs targeting the main protease of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Bioinformatics. 2020; 36:3295–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lobo-Galo N, Terrazas-López M, Martínez-Martínez A, et al. FDA-approved thiol-reacting drugs that potentially bind into the SARS-CoV-2 main protease, essential for viral replication. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–9. Published online ahead of print, 14 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lokhande KB, Doiphode S, Vyas R, et al. Molecular docking and simulation studies on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro reveals Mitoxantrone, Leucovorin, Birinapant, and Dynasore as potent drugs against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–12. Published online ahead of print, 20 August 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mittal L, Kumari A, Srivastava M, et al. Identification of potential molecules against COVID-19 main protease through structure-guided virtual screening approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–19. Published online ahead of print, 20 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Muralidharan N, Sakthivel R, Velmurugan D, et al. Computational studies of drug repurposing and synergism of lopinavir, oseltamivir and ritonavir binding with SARS-CoV-2 protease against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–6. Published online ahead of print, 16 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nutho B, Mahalapbutr P, Hengphasatporn K, et al. Why are lopinavir and ritonavir effective against the newly emerged coronavirus 2019? Atomistic insights into the inhibitory mechanisms. Biochemistry 2020; 59:1769–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Olubiyi OO, Olagunju M, Keutmann M, et al. High throughput virtual screening to discover inhibitors of the main protease of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Molecules 2020; 25:E3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pant S, Singh M, Ravichandiran V, et al. Peptide-like and small-molecule inhibitors against Covid-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–10. Published online ahead of print, 6 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sencanski M, Perovic V, Pajovic SB, et al. Drug repurposing for candidate SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors by a novel in silico method. Molecules 2020; 25:E3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Shamsi A, Mohammad T, Anwar S, et al. Glecaprevir and Maraviroc are high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: possible implication in COVID-19 therapy. Biosci Rep 2020; 40:BSR20201256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tsuji M. Potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug candidates identified through virtual screening of the ChEMBL database for compounds that target the main coronavirus protease. FEBS Open Bio 2020; 10:995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. ul Qamar MT, Alqahtani SM, Alamri MA, et al. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J Pharm Anal 2020; 10:313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wang J. Fast identification of possible drug treatment of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) through computational drug repurposing study. J Chem Inf Model 2020; 60:3277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bzówka M, Mitusińska K, Raczyńska A, et al. Structural and evolutionary analysis indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is a challenging target for small-molecule inhibitor design. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ge XY, Li JL, Yang XL, et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013; 503:535–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Abo-Zeid Y, Ismail NS, McLean GR, et al. A molecular docking study repurposes FDA approved iron oxide nanoparticles to treat and control COVID-19 infection. Eur J Pharm Sci 2020; 153:105465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. de Oliveira OV, Rocha GB, Paluch AS, et al. Repurposing approved drugs as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein from molecular modeling and virtual screening. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–10. Published online ahead of print, 2 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Drew ED, Janes RW. Identification of a druggable binding pocket in the spike protein reveals a key site for existing drugs potentially capable of com-bating Covid-19 infectivity. BMC Mol Cell Biol 2020; 21:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fantini J, Di Scala C, Chahinian H, et al. Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloro-quine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 55:105960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Feng S, Luan X, Wang Y, et al. Eltrombopag is a potential target for drug intervention in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Infect Genet Evol 2020; 85:104419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wei TZ, Wang H, Wu XQ, et al. In silico screening of potential spike gly-coprotein inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 with drug repurposing strategy. Chin J Integr Med 2020; 26:663–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. DurdaGi S. Virtual drug repurposing study against SARS-CoV-2 TMPRSS2 target. Turk J Biol 2020; 44:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Singh N, Decroly E, Khatib AM, et al. Structure-based drug repo-sitioning over the human TMPRSS2 protease domain: search for chemical probes able to repress SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein cleavages. Eur J Pharm Sci 2020; 153:105495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Aftab SO, Ghouri MZ, Masood MU, et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a potential therapeutic drug target using a computational approach. J Transl Med 2020; 18:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ahmad J, Ikram S, Ahmad F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a drug repurposing study. Heliyon 2020; 6:e04502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Choudhury S, Moulick D, Saikia P, et al. Evaluating the potential of different inhibitors on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: a molecular modeling approach. Med J Armed Forces India 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.05.005. Published online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Elfiky AA. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci 2020; 248:117477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020; 395:1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kaddoura M, AlIbrahim M, Hijazi G, et al. COVID-19 therapeutic options under investigation. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11:1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Kandeel M, Abdelrahman AHM, Oh-Hashi K, et al. Repurposing of FDA-approved antivirals, antibiotics, anthelmintics, antioxidants, and cell protectives against SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–8. Published online ahead of print, 29 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Yadav R, Imran M, Dhamija P. Virtual screening and dynamics of potential inhibitors targeting RNA binding domain of nucleocapsid phosphoprotein from SARS-CoV-2. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–16. Published online ahead of print, 22 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Encinar JA, Menendez JA. Potential drugs targeting early innate immune evasion of SARS-coronavirus 2 via 2-O-methylation of viral RNA. Viruses 2020; 12:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Tazikeh-Lemeski E, Moradi S, Raoufi R, et al. Targeting SARS-COV-2 non-structural protein 16: a virtual drug repurposing study. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–14. Published online ahead of print, 23 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ekins S, Mottin M, Ramos PRPS, et al. Déjà vu: Stimulating open drug discovery for SARS-CoV-2. Drug Discov Today 2020; 25:928–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Elmezayen AD, Al-Obaidi A, Şahin AT, et al. Drug repurposing for corona-virus (COVID-19): in silico screening of known drugs against coronavirus 3CL hydrolase and protease enzymes. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–13. Published online ahead of print, 26 April 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Iftikhar H, Ali HN, Farooq S, et al. Identification of potential inhibitors of three key enzymes of SARS-CoV2 using computational approach. Comput Biol Med 2020; 122:103848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zhang DH, Wu KL, Zhang X, et al. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J Integr Med 2020; 18:152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sinha SK, Shakya A, Prasad SK, et al. An in-silico evaluation of different Saikosaponins for their potency against SARS-CoV-2 using NSP15 and fusion spike glycoprotein as targets. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020;1–12. Published online ahead of print, 13 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]