Abstract

Introduction

Non-pharmaceutical measures to facilitate a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a disease caused by novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, are urgently needed. Using the World Health Organization (WHO) health emergency and disaster risk management (health-EDRM) framework, behavioural measures for droplet-borne communicable diseases and their enabling and limiting factors at various implementation levels were evaluated.

Sources of data

Keyword search was conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, Medline, Science Direct, WHO and CDC online publication databases. Using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine review criteria, 10 bottom-up, non-pharmaceutical prevention measures from 104 English-language articles, which published between January 2000 and May 2020, were identified and examined.

Areas of agreement

Evidence-guided behavioural measures against transmission of COVID-19 in global at-risk communities were identified, including regular handwashing, wearing face masks and avoiding crowds and gatherings.

Areas of concern

Strong evidence-based systematic behavioural studies for COVID-19 prevention are lacking.

Growing points

Very limited research publications are available for non-pharmaceutical measures to facilitate pandemic response.

Areas timely for research

Research with strong implementation feasibility that targets resource-poor settings with low baseline health-EDRM capacity is urgently needed.

Keywords: health-EDRM, behavioural measures, non-pharmaceutical, primary prevention, droplet-borne, biological hazards, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, pandemic

Introduction

Uncertainties in disease epidemiology, treatment and management in biological hazards have often urged policy makers and community health protection agencies to revisit prevention approaches to maximize infection control and protection. The COVID-19 pandemic, a disease caused by novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has pushed global governments and communities to revisit the appropriate non-pharmaceutical health prevention measures in response to this unexpected virus outbreak.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) health emergency and disaster risk management (health-EDRM) framework refers to the structured analysis and management of health risks brought upon by emergencies and disasters and was developed based on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. The framework focuses on prevention and risk mitigation through hazard and vulnerability reduction, preparedness, response and recovery measures2 and further calls attention to the significance of community involvement to counteract the potential negative impacts of hazardous events such as infectious disease outbreaks.2 While the framework does not provide details on event-specific prevention, it is well justified for primary prevention measures against COVID-19, which is defined as a biological hazard under the health-EDRM disaster classification.3 While there is evidence for potential COVID-19 droplet transmission,4 the WHO has suggested that airborne transmission may only be possible in certain circumstances4 and further evidence is needed to categorize it as an airborne disease specifically.

Health-EDRM prevention measures can be classified into primary, secondary or tertiary levels.5 Primary prevention mitigates the occurrence of illness through an emphasis on health promotion and education aimed at behavioural modification6; secondary prevention involves screening and infection identification; tertiary prevention focuses on treatment. In the context of COVID-19, both secondary and tertiary preventive measures are complicated due to the high incidence of asymptomatic patients,7 the lack of consensus and availability of specific treatment or vaccine8 and the added stress on the health system during a pandemic. Primary prevention that focuses on protecting an individual from contracting an infection9 is therefore the most practical option. A comprehensive disaster management cycle (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery) encompasses both top-down and bottom-up measures.10,11 Top-down measures require well-driven bottom-up initiatives to successfully achieve primary prevention and effectively modify community behaviours.12 During and since the writing of this review, several landmark publications have studied and addressed the effect of non-pharmaceutical behavioural measures in preventing the transmission of COVID-19, generally concluding that while effectiveness and uptake of measures varied, behavioural change at personal and population levels is key to effectively control the spread of COVID-19.13–17 The purpose of this narrative review is to highlight the feasibility of implementing non-pharmaceutical preventive measures within a population facing an emergency, building on the health-EDRM framework, and theoretical aspects of behavioural change presented in other publications.

Based on the health-EDRM framework, which emphasizes the impact of context on efficacy of measure practices,3 this article examines available published evidence on behavioural measures that might be adopted at the personal, household and community levels for droplet-borne transmitted diseases and enabling and limiting factors for each measure. Additionally, this article reviews the strength of available scientific evidence for each of the behavioural changes, which may reduce health risks.

Methodology

A literature search was conducted in May 2020. English language-based literature published between January 2000 and May 2020 were identified and included. Further literature was identified using the references of those already reviewed. Types of literature include international peer-reviewed articles, online reports, commentaries, editorials, electronic books and press releases from universities and research institutions, which include expert opinions. Grey literature published by the WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other local government publications and information outlets were also included. Literature that did not fulfil the criteria was excluded, for example peer-reviewed studies without English-language abstracts.

Research databases examined in this study included PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, Medline and Science Direct. The keywords and phrases included in the initial search can be broadly categorized into three groups: those relating to the virus, including variations of COVID-19 nomenclature, or relevant to broader respiratory viruses (such as ‘COVID-19’, ‘SARS’, ‘enveloped viruses’); those relating to general disease prevention and management (such as ‘transmission’, ‘risk management’) and those relating to primary prevention measures (such as ‘handwashing’, ‘coughing and sneezing’, ‘face masks’). The full list can be found in Appendix 1. Behavioural measures as well as risk factors for infectious disease transmission were reviewed in order to generate 10 common preventive measures for discussion. The avoidance of cutlery sharing, for example, was generated after determining it as a highly preventable risk for infectious disease transmission. Each primary prevention measure was summarized narratively according to the risk factors, co-benefits, enabling and limiting factors and strength of evidence. Three reviewers assessed the studies independently and agreed on the final research used.

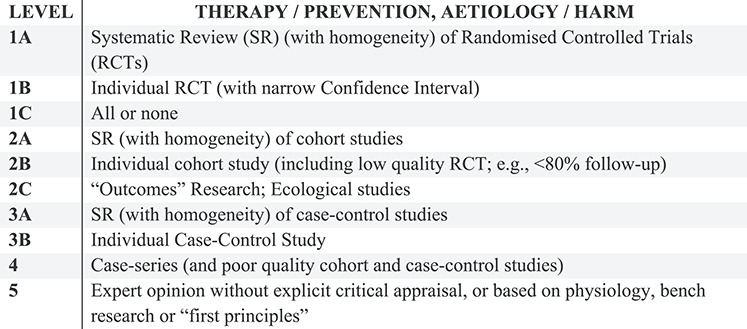

The literature was categorized according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence (Fig. 1),18 which systemizes strength of evidence into levels, based on the process of study design and methodology. Three reviewers collectively engaged in and agreed on the final categorization.

Fig. 1.

The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence (adapted from www.cebm.net).18

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this review.

Results

The search identified 104 relevant publications, all of which were reviewed and included in the results analysis. The search identified and grouped 10 common bottom-up, non-pharmaceutical, primary prevention behavioural measures, based on the health-EDRM framework. The review of evidence is disaggregated into the 10 prevention measures.

Six ‘personal’ protective practices (engage in regular handwashing, wear face mask, avoid touching the face, cover mouth and nose when coughing and sneezing, bring personal utensils when dining out and close toilet cover when flushing), two ‘household’ practices (disinfect household surfaces and avoid sharing cutlery) and two ‘community’ practices (avoid crowds and mass gatherings and avoid travel) were identified. Tables 1–3 highlight the potential health risk, desired behavioural changes, potential health co-benefits, enabling and limiting factors and strength of evidence available in published literature with regard to these measures.

Table 1.

(Part 1): Personal practices as preventive measure—risk; behavioural change; health co-benefits; enabling and limiting factors and strength of evidence

| Engage in regular handwashing | Wear face mask | Avoid touching the face | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk |

|

|

|

| Behavioural change |

|

|

|

| Co-benefit(s) | |||

| Enabling factor(s) |

|

|

|

| Limiting factor(s) and/or alternative(s) |

|

|

|

| Strength of evidence |

|

|

|

| Risk | |||

| Behavioural change |

|

|

|

| Co-benefit(s) |

|

|

|

| Enabling factor(s) |

|

|

|

| Limiting factor(s) and/or alternative(s) |

|

|

|

| Strength of evidence |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Community practice as preventive measure—risk; behavioural change; health co-benefits; enabling and limiting factors and strength of evidence

| Avoid crowds and mass gatherings | Avoid travel | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | • Crowded areas with unknown people are considered high risk due to risk of droplet transmission and infection through contaminated surfaces • Talking can potentially result in respiratory infectious disease transmission108 • Possibility of transmission by asymptomatic carriers within a crowd increases risk109 |

• Travelling to areas with confirmed cases will increase an individual’s risk of potential exposure to COVID-19 • The stability of the virus on surfaces,20 the potential prevalence of asymptomatic carriers,109 the difficulty and lack of distancing,110 shared toilets and risk of toilet plume86 and uncertain travel history of others make environments. such as trains and aeroplanes, challenging in terms of protection and high risk in terms of COVID-19 transmission |

| Behavioural change | • Observe social distancing measures4,19,25,32–34,42,78,111 • A separation of 1 m is the minimum as recommended by the WHO.41 Although most droplets may not travel across this distance, novel studies exploring the influence of aerodynamics112 as well as the potential for sneezes to travel up to 8 m80 have led to the recommendation that possible distancing should be maintained wherever possible • Avoid congregating and take precaution when in public areas such as parks, cinemas and restaurants. These areas should make face mask wearing mandatory, carry out temperature checks, limit the number of people in attendance and practice distancing of people |

• Avoid travelling to areas with confirmed cases, which are of significant risk25,33,34 • Take all necessary personal protective measures such as wearing of face masks, eye googles, disinfecting immediate area with alcohol-based solution and avoiding food sharing • Implementing (for authorities) appropriate protective measures such as mandatory temperature checks prior to travel and/or upon arrival, reporting the travel and medical history of each traveller and distancing requirements on transport |

| Co-benefit(s) | • Reduced outdoor pollution due to minimized outdoor human activity.113,114 Lower exposure to outdoor air pollution, which causes respiratory illnesses such as lung cancer and contributes to mortality60,115 |

• Reduction of cross-border transmission111 • Improved general hygiene on transport such as trains or aeroplanes • Environmental benefit from reduced air-travel carbon footprint116 |

| Enabling factor(s) | • Ability to avoid crowded areas as permissible by population density, occupation, religion or culture | • Ability to make decisions on when or how to travel |

| Limiting factor(s) and/or alternative(s) | • Crowded areas may not be avoidable due to occupation, religious necessities or otherwise. Where gathering is necessary, individuals should take personal responsibility to wear masks, keep hands clean and maintain maximum distance from others | • Access to facemasks, goggles or alcohol-based solution for personal protection during travel • The necessity of travel, for personal or professional reasons, such as pilots and the cabin crew |

| Strength of evidence | • Studies on influenza and COVID-19117 indicate a potential role of mass gathering reduction in limiting transmission,118 though studies are limited and not yet conclusive • There are also studies on the elevated transmission of other viruses as a result of mass gatherings119–121 |

• The proximity and contact with individuals heighten the evidenced risk of taking in potential respiratory droplets containing COVID-19 from others • There is no clear evidence regarding increased risk from aeroplane travel specifically |

Table 2.

Household practices as preventive measure—risk; behavioural change; health co-benefits; enabling and limiting factors and strength of evidence

| Disinfect household surfaces | Avoid sharing utensils | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | • COVID-19 has varying stability on different household surfaces, including metal, wood, glass, plastic, paper and steel.100 • Personal belongings such as mobile phones and laptops have been shown to carry a high load of bacteria101,102 due to inadequate cleansing and lots of hand contact. The same may apply for virus particles |

• Studies have previously demonstrated cutlery sharing practices as a risk for oral transmission103 • Due to the high possibility of COVID-19 transmission through saliva droplets,81,82 it may pose similar risk • There is additional unknown risk due to potential for asymptomatic transmission25 |

| Behavioural change | • Disinfect households regularly,29,30,32–34,42 especially frequently touched objects and surfaces,48 with biocidal agents such as 62–71% ethanol, 0.1% sodium hypochlorite or 0.5% hydrogen peroxide79 • Use a dilution of 1:50 bleach for general household disinfecting of flooring and doors79 • Disinfect smaller objects, such as keys, or surfaces that come in contact with the face and mouth, such as mobile phones, with 62–71% ethanol or alcohol wipes instead,79 due to potential hazards from bleach104 |

• Avoid sharing of utensils or serving food from a communal dish with used utensils • Use designated serving utensils to prevent saliva-based droplet transmission • Maintain hygiene practices, such as adequate cleaning of all utensils |

| Co-benefit(s) | • Improved general household hygiene, such as mould reduction105,106 • Opportunity for mild physical activity to compensate for lack of outdoor exercise during COVID-19 social isolation |

• Reduced risk of other saliva-transmitted bacteria while utensil sharing90 • Reduced risk of dental caries transmission107 |

| Enabling factor(s) | • Access to proper disinfectants • Knowledge on safe use and storage of disinfectants |

• Availability of serving utensils • Cultural appropriateness, such as when seating in settings where such sharing is expected |

| Limiting factor(s) and/or alternative(s) | • Where resources are limited, households should use the best disinfectant possible, reduce the frequency of disinfection or target frequently touched surfaces such as door handles | • Where appropriate, hand consumption after adequate handwashing may be considered to avoid utensil sharing. Proper handwashing practices must be observed |

| Strength of evidence | • Studies exist on the effectiveness of various household disinfectants against other viruses, including coronaviruses79 • Evidence on the effectiveness against COVID-19 specifically is lacking |

• Given its transmission through droplets,19 and persistence in saliva,81 this prevention measure should be considered good practice • This measure was recommended by the CDC during the 2003 SARS outbreak.34 • There is no study on the impact of utensil sharing on COVID-19 specifically • Studies have noted potential spread of H. pylori via shared chopsticks91 |

Of note, a number of the reviewed articles report an assessment of more than one primary prevention measure. The review results showed that ~68% of the studied literature was associated with personal practices, 13% with household practices and 19% with community practices. The measures of engaging in regular handwashing, wearing face masks as well as avoiding mass gatherings were among the most commonly studied preventive measures. Details of each utilized reference can be found in Appendix 2.

Discussion

Evidence relating to 10 common health-EDRM behavioural measures for primary prevention against droplet-borne biological hazards were identified and reviewed. The information referenced here is based on best available evidence and will need to be updated as new studies and guidelines are published, and the understanding of the scientific community is enhanced. At the time of writing, there is an outstanding question as to whether COVID-19 is transmitted through droplet or aerosol in the community. Following the writing of this review, certain areas of evidence have evolved. On June 5, 2020, the WHO updated its official guidance to recommend that face masks be worn by the general public as a preventive measure against COVID-19 transmission.122 The WHO had previously recommended that masks be worn only by healthcare workers and people confirmed to have COVID-19, due to limited evidence that masks worn by health individuals may be effective as a prevention measure.123 The knowledge and consensus within the scientific community on COVID-19 continue to evolve at an unprecedented rate.

Although direct evidence on the efficacy of COVID-19-specific prevention measures is lacking, largely due to the novelty of the disease, five behavioural measures were identified: regular handwashing, wearing face masks, avoiding touching of face, covering during sneezing or coughing and household disinfecting. Five other potential behavioural measures were also identified through logical deductions from potential behavioural risks associated with transmission of diseases similar to COVID-19.79 Utensil-related practices, in particular, were heavily limited in evidence to support their efficacy against viral infections.

The efficacy and success of the 10 bottom-up behavioural measures reviewed here are subject to specific enabling and limiting determinants, ranging from demographic (e.g. age, gender, education), socio-cultural, economic (e.g. financial accessibility to commodities) and knowledge (e.g. understanding of risk, equipment use). The viability and efficacy of each measure may be limited by determinants and constraints in different contexts. Resource-deprived areas may face constraints and reduced effectiveness of implementation, especially for measures that require preventive commodities such as face masks and household disinfectants. As such, special attention should be given to rural settings, informal settlements and resource-deficit contexts where access to information and resources such as clean water supply are often limited,124,125 and sanitation facilities are lacking.126 For hygiene measures, different alternatives should be promoted and their relative scientific merits should be evaluated, such as the use of ash as an alternative to soap for handwashing67 or the efficacy of handwashing with alcohol sanitizer, which has been demonstrated in previously published studies for H1N1127 and noroviruses128 but not yet concretely for COVID-19. Meanwhile, for measures that have no direct alternatives available, it is important for authorities and policymakers to understand the capacity limitations of certain target groups and provide additional support or put in place other preventive measures. In cases where material resources are scarce, the measures of awareness on sneezing and coughing etiquette as well as avoiding hand-to-face contact are the most convenient to adopt as they require little to no commodities. However, it should be well noted that these measures are likely the most challenging in compliance and enforceability, as they rely on the modification of frequent and natural human behaviours whose modifications would require awareness and practice.50,51 Furthermore, these can be challenging to implement in target groups with less capacity for health literacy and translation of education into practice, such as infants and elderly suffering from dementia. Cultural patterns can be associated with behavioural intentions. In the case of avoiding utensil-sharing during meals, enforcing change may be conflicted with cultural and traditional norms in Asia and certain European communities.129

Of the enabling factors documented for each proposed measure, shared enablers can be identified: accessibility and affordability of resources; related knowledge, awareness and understanding of risk; and associated top-down policy facilitation. Majority of personal and household practices heavily rely on access to resources, such as adequate water and soap supply for regular handwashing, quality face masks and household disinfectants. Various theories of the ‘Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices’ model have assumed that individual knowledge enhancement will lead to positive behavioural changes.130 Health measures targeting mask wearing might aim to enhance (i) the individual’s risk perception, knowledge and awareness on protection effectiveness of masks, and how to properly wear a mask so that the prevention is most effective; (ii) an individual or community’s attitude towards the practice of mask wearing and encouraging compliance in the west, as studies demonstrate a relatively greater social stigmatization towards mask wearing among Westerners than East Asians131 and (iii) normalizing the practice of habitual mask wearing. Such a conceptual framework should be utilized in the implementation of the health initiatives. In terms of overarching knowledge, health education on symptom identification is also important, as seen on government platforms such as the CDC.42 Enhancing health-seeking behaviour of potential carriers is critical to promoting a rapid response for quarantine or hospitalization.

At the individual level, behavioural changes have different sustainability potentials and limitations. Measures can also result in unintended consequences. For example, regarding the improper disposal of face masks132 and the incorrect use of household disinfectants,133 careful monitoring is critical in order to maximize impact while minimizing further health and safety risks. Top-down policy facilitation and strengthening of infrastructure will be essential for effective implementation. Top-down efforts in resource provision, such as the distribution of quality masks to all citizens by the government or similar authority,134 enhance personal and household capacities to mitigate infection risks. Regarding compliance, the effectiveness of community practices, such as crowd and travel avoidance, is highly dependent on the needs and circumstances of an individual and a community. More assertive top-down policies such as travel bans and social distancing rules may drive bottom-up initiatives within communities under legal deterrence.135 However, in order to ensure population-level compliance to recommendations that have wide-ranging socioeconomic impact and involve more than a day-to-day behavioural change, careful risk and information communication is required, which takes into consideration practical, legal and ethical aspects. Research into promoting behavioural change during the COVID-19 pandemic have suggested that public health professionals, policy makers and community leaders can enhance compliance by creating a sense of motivation in individuals rather than creating anxiety that can lead to defensive avoidance.16 Information should be tailored and account for language, education and health literacy, with input from stakeholders, such as community leaders, religious heads or allied health workers, who can advise on how to enhance understanding of risks and benefits, especially if targeted at marginalized populations.16,17 It is important to create a bipartisan, shared sense of identity and cooperative responsibility within the population, for example using collective terms such as ‘us’ or ‘we’ in risk communication, and using interdisciplinary approaches that bring together groups from different backgrounds, such as medical practitioners, epidemiology experts, community leaders and non-governmental agencies working at the grassroots level.17

With regard to the strength of evidence available in the reviewed literature (Table 4), the largest proportion of studies fell into Level 5 (69%) classification, which encompasses a range of study designs and methodologies such as narrative reviews, experimental studies, modelling studies and expert opinions. Less than 1% of the identified resources were classified into ‘Others’, which includes the WHO Dashboard for latest figures on COVID-19. Level 4 studies, such as cross-sectional studies and case series, contributed a relatively large portion (16%) with many focusing on the disease progression and patterns of specifically identified patients. The low proportion of Level 1 studies (7%) compared to Level 4 or 5 may be attributed to the novelty of COVID-19. Higher level studies generally involve more rigorous and stringent methodologies, which would inevitably require more time.

Table 4.

Overview of behavioural measures against COVID-19 transmission in the reviewed articles, categorized by the OCEBM Levels of Evidence (See Appendix 2 for details)

| Category | Primary preventive measure | Number of referenced articles per OCEBM categorization level | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 1c | 2a | 2b | 2c | 3a | 3b | 4 | 5 | Others | Total | ||

| Personal practices | Engage in regular handwashing | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 34 |

| Wear face mask | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 18 | 1 | 31 | |

| Avoid touching the face | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 13 | |

| Cover mouth and nose when coughing and sneezing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 17 | |

| Bring personal utensils for when dining out | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 10 | |

| Close toilet cover when flushing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Household practices | Disinfect household surfaces | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 13 |

| Avoid sharing utensils | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| Community practices | Avoid crowds and mass gatherings | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 0 | 23 |

| Avoid travel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 9 | ||

| Total | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 27 | 116 | 1 | 167* | |

OCEBM, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

*Some of the 104 publications are referenced against more than 1 of the 10 primary preventive measures.

Regarding individual primary prevention measures, evidence is most lacking at all levels for the practices involving avoidance of utensil sharing (5%), bringing personal utensils (6%), travel avoidance (5%) and the closing of toilet lids when flushing (5%). On the other hand, most of the available evidence supports measures such as handwashing (20%), wearing face masks (19%) and avoiding crowds (14%). Literature relevant to regular handwashing was the strongest in terms of study design, with 26% of the total literature identified for this particular practice being Level 1 studies and 82% of all Level 1 studies identified being associated with regular handwashing. In the case of a novel or emerging disease such as COVID-19, there is limited available evidence that can be related specifically to the disease and pandemic, but some findings are deduced from studies on other similar viral infections and transmittable conditions, such as SARS or Influenza. Many measures proposed by health authorities are not based on rigorous population-based longitudinal studies. While handwashing is well regarded as a core measure by global and national public health agencies such as the WHO41 and CDC,42 and the chemical properties of eliminating enveloped viruses is well understood,43,65 specific studies on the efficacy of practice and impact on COVID-19 transmission are lacking. Due to the uncertainties of disease pathology and epidemiology, effectiveness of behavioural measures against COVID-19 is far from conclusive. Other uncertainties are also reported on virus surface stability20 and whether the efficacy of disinfectants against surface-stable viruses may vary with COVID-19.79 Similar deductive evidence approaches from studies on other viruses have been utilized to judge the efficacy of face masks or the closing of toilet lids.87,88 Although published evidence suggested individual measures such as covering coughs and sneezes to be helpful against droplet transmissions,19 further research is needed to understand the true efficacy of coverings such as masks, tissues or elbows as an adequate preventive measure against COVID-19.

Given the rapid knowledge advancement and research updates related to COVID-19, further study updates will be warranted to identify the most appropriate behavioural measures to support bottom-up biological hazard responses. Cost-effectiveness of the measures, their impact sustainability, co-benefits and risk implications on other sectors should also be examined and evaluated. Standardized studies across different contexts should be enhanced, for example conducting tests on the efficacy of different disinfectants or soaps under a standardized protocol. Such studies would increase evidence on individual and comparative efficacy of the behavioural measures.

The limitations in this review include language, database inclusion, online accessibility of the article, grey literature and informal publication outlets, and missed keywords. Search terms were determined using variations of terms for COVID-19 or respiratory viruses, as well as a number of preventive practices that are well documented. However, search terms did not encompass the full spectrum of terms relating to behavioural measures. For community practices, the terms searched included ‘mass gathering’ and ‘social isolation’ but not ‘travel restriction’, although limiting travel was later identified as a standalone measure through reviewing the literature search results. Publications documenting the experiences of traditional, non-English-speaking, rural communities during the COVID-19 pandemic may not have been identified in this review. Further research should review the efficacy of various measures in different contexts and make comparisons with their alternative measures. Specifically, alternative preventive measures that can be practiced in resource-poor, developing communities, whose health systems and economies generally suffer the greatest impact during pandemics, are urgently needed. Increased understanding of how to effectively mitigate against biological hazards such as COVID-19 in various contexts will help communities prepare for future outbreaks and build disaster resilience in line with the recommendations from the health-EDRM framework.

Despite the constraints, this review has nevertheless identified common, relevant behavioural measures supported by best available evidence for the design and implementation of health policies that prevent droplet-borne biological hazards. Many of the measures recommended by authorities during the pandemic are based on best practice available rather than best available evidence. The possibility of conducting large cohort or randomized controlled studies is often complicated, and rather infeasible during a pandemic, as noted for face masks.136,137 Further studies are needed to understand the efficacy of frequently proposed measures for transmission risk reduction. Nonetheless, each of the measures identified has scientific basis in mitigating the risk of droplet transmission,19 either through personal measures such as handwashing or community-based measures that aim to reduce person-to-person contact. The 10 measures identified in this review constitute only a portion of those non-pharmaceutical and primary preventive behaviours that can mitigate against the transmission of a droplet-borne disease and do not represent the entire spectrum of either non-pharmaceutical or primary prevention measures. Alternatively, the measures identified here can also fall into other subsets such as ‘biological hazard prevention’ or ‘community outbreak prevention’. It is important to explore the efficacy of alternatives, notably for transmission prevention and risk communication in low-resource or developing contexts where the capacity of the health system to mitigate and manage outbreaks is weak. For example, while face masks are understudied, the scientific study of cloth masks as an alternative is severely limited,70 although recommended by the CDC.138 Such alternative studies should expand to consider different cultures and contexts where different varieties of disinfectants, face masks and utensils may be used. There is also potential for comparative effectiveness studies to explore measures that provide the greatest transmission risk reduction at the lowest transaction cost to the individual and community and should thus be prioritized in low-resource contexts.139

Conclusion

During the outbreak of a novel transmittable disease such as COVID-19, primary prevention is the strongest and most effective line of defence to reduce health risks when there is an absence of an effective treatment or vaccine. COVID-19 is and will be subjected to ongoing research and scrutiny by global scientists, health professionals and policy makers. While research gaps remain on the efficacy of various health-EDRM prevention measures in risk reduction and transmission control of COVID-19, suboptimal scientific evidence does not negate the potential benefits arising from good hygiene practices, especially where the likelihood for negative outcome is minimal. Despite the lack of rigorous scientific evidence, the best available practice-based health education content, effective means of information dissemination, equitable access to resources and monitoring of unintended consequences of the promoted measures, such as environmental pollution due to poor waste management, will be essential. A top-down approach should be multi-sectorial, bringing in policy makers with clinical, public health, environmental and community management expertise to develop a coordinated and comprehensive approach in this globalized world.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Dr Ryoma Kayano, from the WHO Centre for Health Development, for his valuable input and support into this publication.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Keywords and phrases searched, by subject grouping

| Subject group | Keyword or phrases searched | |

|---|---|---|

| Virus | COVID-specific | COVID-19 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | ||

| COVID-19 stability | ||

| 2019-nCOV | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 entry points | ||

| COVID-19 policies | ||

| WHO COVID-19 | ||

| CDC COVID-19 | ||

| COVID-19 advice | ||

| Ethics COVID-19 | ||

| Other related viruses | Droplet transmission | |

| Virus | ||

| Coronavirus treatment | ||

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome | ||

| SARS | ||

| Coronavirus | ||

| Enveloped viruses | ||

| Respiratory virus | ||

| Respiratory hygiene | ||

| Respiratory emission | ||

| Public Health | Epidemiology | Epidemiology |

| Transmission | ||

| Virus stability | ||

| Virus transmission | ||

| Host responses to virus | ||

| Virus outbreak | ||

| Prevention and management | Health-EDRM | |

| Risk management | ||

| Global health | ||

| Prevention | ||

| Infection risk reduction | ||

| Hygiene education | ||

| Primary prevention practices | Personal | Air pollution |

| Handwashing | ||

| Pollution mask | ||

| Face masks | ||

| Rural handwashing | ||

| Face touching | ||

| Coughing and sneezing | ||

| Toilet plume | ||

| Household | Disinfection | |

| Biocidal agents virus | ||

| Utensil sharing risk | ||

| Cutlery sharing risk | ||

| Phone hygiene | ||

| Sodium hypochlorite disinfection | ||

| Open defecation | ||

| Community | Mass gatherings | |

| Social isolation | ||

| Quarantine | ||

| Social distancing | ||

Appendix 2. Relevant measure(s), study design, relevant key finding(s) and/or conclusion of each utilized reference

| Ref. No. | Title | Journal or publication | Date of publication | Relevant measure(s) (See Key 1) | OCEBM Level of Evidence based on study design (See Key 2) | Relevant key finding(s) and/or conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Modes of Transmission of Virus Causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC Precaution Recommendations | WHO Scientific Brief | March 2020 | A, B, I | Level 5: Expert opinion on precaution recommendations, using research on the characteristics of COVID-19 | • With knowledge of droplet transmission (and particle size), droplet and contact precautions are recommended for COVID-19 • Importance of PPE and other practices such as frequent hand hygiene is indicated |

| 19 | COVID-19: A Call for Physical Scientists and Engineers | American Chemical Society NANO | April 2020 | A, D, H, I | Level 5: Expert opinion based on clinicians’ experiences and knowledge; presentation of questions, hypotheses and research needs regarding COVID-19 | • Elucidates basic biology of viruses and their transmission and infection pathway • Importance of handwashing and hygiene is demonstrated via explanation of the need to deactivate released virions before they reach a host • Identifies the major complications and understandings associated with current measures such as PPE and surface sanitization and make recommendations accordingly |

| 20 | Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1 | The New England Journal of Medicine | April 2020 | A, C, D, J | Level 5: An in vitro study of the surface stability of the SARS-Cov-2 strain compared to SARS-CoV-1 | • SARS-CoV-2 has similar surface stability compared to SARS-CoV-1 under experimental circumstances • Demonstrates stability on surfaces such as plastic and stainless steel with potential for aerosol and fomite transmission |

| 21 | Community Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, Shenzhen, China, 2020 | Emerging Infectious Diseases | June 2020 (Early Release) | B | Level 4: A case series on confirmed COVID-19 studied in order to understand the pattern of community transmission | • COVID-19 became endemic to Shenzhen. Community, intrafamily and nosocomial transmission routes were found. • Maintenance strategies are derived, such as minimizing public activity, using personal protection measures and the importance of early screening, diagnosis and isolation |

| 22 | A Familial Cluster of Pneumonia Associated with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Indicating Person-to-Person Transmission: A Study of a Family Cluster | The Lancet | February 2020 | B | Level 4: A case series exploring epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, radiology and microbiological findings of a family cluster of (initially) unexplained pneumonia | • Indicating person-to-person transmission via nosocomial and intrafamily means • Noted that many findings were similar to those of SARS patients in 2003 • One patient was initially asymptomatic—suggestion for early tracing, quarantine and control measures |

| 23 | Tropism and Innate Host Responses of Influenza A/H5N6 Virus: An Analysis of Ex Vivo and In Vitro Cultures of the Human Respiratory Tract | European Respiratory Journal | March 2017 | B | Level 5: An in vitro study on tropism, replication competence and cytokine induction of virus isolates in cultures (Ex Vivo and In Vitro) derived from human respiratory tract | • Human H5N6 virus adapted to human airways, indicating a risk pattern for the virus upon entry into respiratory tract |

| 24 | 2019-nCoV Transmission Through the Ocular Surface Must Not Be Ignored | The Lancet | February 2020 | B | Level 5: An ophthalmologist’s expert perspective on additional risk through mucous membrane of eyes | • Suggestion for consideration of studies into conjunctival scrapings to look for signs of ocular transmission • Ophthalmologists must wear protective eyewear when examining suspect cases |

| 25 | Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19 | Journal of the American Medical Association | February 2020 | A, B, D, I, J, H | Level 4: A case series on a familial cluster of five patients with COVID-19 | • There is a potential mechanism of COVID-19 transmission via an asymptomatic carrier • Further study on the relevant mechanism is suggested |

| 26 | Emergencies Preparedness, Response: What Can I Do? | WHO | January 2010 | B | Level 5: A compilation of information on pandemic response (2009 H1N1) protective measures | • Regarding masks specifically, it suggests that masks are only needed if you are sick • Remarks on the importance of proper mask-wearing practice if the measure is adopted |

| 27 | SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors Are Highly Expressed in Nasal Epithelial Cells Together with Innate Immune Genes | Nature Medicine | April 2020 | B, C | Level 5: A study on SARS-CoV-2 tropism study via study of expression of viral entry-associated genes | • Genes found to be co-expressed in nasal epithelial cells, indicating a role in the initial phase of viral infection, spread and clearance |

| 28 | Use of Disposable Face Masks for Public Health Protection against SARS | Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health | April 2004 | A, B | Level 5: Expert opinion on the use of face masks and practice of personal hygiene as important measures to protect the general public from SARS | • States that protection against SARS for healthcare workers is different from the general public, as the latter is not subject to continuous exposure to droplet transmission from an infected patient • Expresses reduced risk of aerosol droplet transmission with masks • Notes importance of proper usage and frequent changing of masks • Also extends to mention importance of other personal hygiene practices such as handwashing due to survival of the virus on surfaces |

| 29 | SARS Transmission, Risk Factors, and Prevention in Hong Kong | Emerging Infectious Diseases | April 2004 | A, B, G | Level 3b: A case–control study to compare SARS case patients with undefined sources of infection with community controls | • Concluded that risk factors for SARS infection include visiting mainland China, hospitals and the Amoy Gardens (an estate with a SARS outbreak) • Indicates that frequent mask use in public venues, frequent handwashing and household disinfection were prominent protective factors |

| 30 | Respiratory Infections during SARS Outbreak, Hong Kong, 2003 | Emerging Infectious Diseases | November 2005 | A, B, D, G | Level 4: A cross-sectional study to compare the proportion of respiratory virus-positive specimens in 2003 and those from 1998 to 2002 | • No direct causal relationship was established • However, the study suggests a positive association between reduced influenza/respiratory infection incidence and population-based hygienic measures including face mask wearing, hand washing after contact with potentially contaminated objects, using soap for handwashing, mouth covering when sneezing or coughing and household disinfection |

| 31 | Controlling the Novel A (H1N1) Influenza Virus: Don’t Touch Your Face! | The Journal of Hospital Infection | November 2009 | A, C | Level 5: A letter to the editor on a study of surface swab specimens from patients with confirmed influenza A | • Indicates that virus strains of influenza A are found in surfaces such as bed rails, walls and sofas • Further implies the importance of hand hygiene, droplet and contact precautions and behavioural conditioning such as avoiding touching of the nose, eye or mouth to prevent and control influenza |

| 32 | Stopping the Spread of COVID-19 | Journal of the American Medical Association | March 2020 | A, C, D, G, I | Level 5: A set of guidelines with potential measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 | • Different methods of infection prevention including hand hygiene, social distancing, household disinfection and general personal hygiene are suggested |

| 33 | Prevention of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection | May 2020 | A, B, C, D, F, G, I, J | Level 5: A set of guidelines with information related to COVID-19 such as prevention suggestions and clinical features of the coronavirus | • Prevention advice such as mask wearing, avoidance of face touching, covering mouth and nose, putting the toilet lid down when flushing and general travel advice is suggested |

| 34 | Fact Sheet for SARS Patients and Their Close Contact | Centres for Disease Control and Prevention | 2003 | A, B, C, D, E, F, H, I, J | Level 5: A set of guidelines with information related to SARS such as symptoms, mode of transmission and prevention measures | • Personal protection measures, such as the avoidance of silverware sharing, handwashing and covering mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, are recommended |

| 35 | WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care | WHO | 2009 | A | Level 5: An extensive evidence-based guideline on the practice and science behind handwashing | • Extensive findings on best handwashing practice and efficacy of soap-based washing and alcohol against enveloped viruses |

| 36 | Simplifying the World Health Organization Protocol: 3 Steps Versus 6 Steps for Performance of Hand Hygiene in a Cluster-Randomized Trial | Clinical Infectious Diseases | August 2019 | A | Level 1b: A cluster-randomized trial assigning three-step versus six-step handwashing protocol | • Findings suggest that both significantly reduced the bacterial colony (with no significant difference between the two) but that the three-step guidelines had higher compliance Quantity of steps is not of great concern as long as areas are covered |

| 37 | The Common Missed Handwashing Instances and Areas after 15 Years of Hand-Hygiene Education | Journal of Environmental and Public Health | August 2019 | A | Level 4: A cross-sectional study looking at a cohort in Hong Kong and their handwashing and hand hygiene practices | • Indicates several areas of the hands which are commonly missed, as well as occasions during which handwashing should be performed • Relationship between age or education and hand hygiene practice is indicated |

| 38 | Hygiene and Health: Systematic Review of Handwashing Practices Worldwide and Update of Health Effects | Tropical Medicine and International Health | May 2014 | A | Level 1a: A systematic review of RCTs and quasi-randomized trials (+others). Studies observed rates of handwashing with soap in various populations and scenarios | • Significant global problem regarding poor practice of handwashing after contact with excrete is found |

| 39 | Assessment of Hand Hygiene Techniques Using the World Health Organization’s Six Steps | Journal of Infection and Public Health | December 2015 | A | Level 2b: An individual cohort study observing hand hygiene techniques over a period of 5 months | • Certain areas of the hand achieved lower areas of compliance during handwashing |

| 40 | Bacteriological Aspects of Hand Washing: A Key for Health Promotion and Infections Control | International Journal of Preventative Medicine | March 2017 | A | Level 3a: A systematic review of case–control studies | • Handwashing can reduce infectious agent’s transmission in the community and healthcare settings |

| 41 | Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public | WHO | April 2020 | A, B, C, D, I | Level 5: Expert opinion on personal protection from COVID-19 such as safe use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers | • Informs the public of the importance of actions such as regular handwashing with soap and water; cleaning hands with alcohol-based rub; social distancing; avoiding crowds; avoiding eye, nose, mouth touching; covering mouth and nose; staying home and health-seeking behaviour under the pandemic • Precautions on alcohol-based hand sanitizer use are also mentioned |

| 42 | How to Protect Yourself & Others | Centres for Disease Control and Prevention | April 2020 | A, B, D, G, I | Level 5: Expert opinion on how COVID-19 spreads and personal protection measures for COVID-19 | • Informs the public of person-to-person spread of the virus, the lack of vaccine to prevent COVID-19 and the importance of actions such as regular handwashing with soap and water, avoiding close contact, covering mouse and nose with a cloth face cover, covering coughs and sneezes, as well as cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and households under the pandemic |

| 43 | Hand Hygiene and the Novel Coronavirus Pandemic: The Role of Healthcare Workers | The Journal of Hospital Infection | March 2020 | A | Level 5: Expert opinion on the importance of practicing respiratory and hand hygiene, as well as using personal protective equipment in healthcare settings | • Details the role of healthcare workers, nurses and midwives in providing primary point of care in communities and for pregnant women, respectively, especially during infectious disease outbreaks • Mentions details and precautions when using alcohol-based hand rubs for hand hygiene |

| 44 | A Schlieren Optical Study of the Human Cough With and Without Wearing Masks for Aerosol Infection Control | Journal of the Royal Society, Interface | December 2009 | B, D | Level 5: A study comparing the fluid dynamics of coughing with or without standard surgical or N95 mask wearing using video records | • Human coughing projects a rapid turbulent jet into the surrounding air • Wearing a surgical or N95 mask interrupts the natural mechanism of airborne infection transmission through blocking turbulent jet formation (N95 mask) or redirecting the exhalant (surgical mask) |

| 45 | Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks | Nature Medicine | April 2020 | B | Level 1b: A randomized controlled trial comparing exhaled breath samples (for respiratory virus shedding) in mask-wearing versus non-mask-wearing individuals | • Surgical face masks can prevent transmission of human coronaviruses and influenza viruses from symptomatic individuals • Surgical face masks reduce detection of coronavirus RNA in aerosols, with a trend towards reduced detection of coronavirus RNA in respiratory droplets |

| 46 | Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia | The New England Journal of Medicine | January 2020 | B | Level 4: A case series looking at characteristics and illness timelines of laboratory confirmed cases of COVID-19 | • Human-to-human transmission has occurred and that measures must be implemented towards populations at risk |

| 47 | Contamination by Respiratory Viruses on Outer Surface of Medical Masks Used by Hospital Healthcare Workers | BMC Infectious Diseases | June 2019 | B | Level 1b: An individual randomized controlled trial with two pilot studies (cohort). Participants told to wear medical masks and then masks were checked for respiratory viruses on the surface | • Virus presence on the face mask was higher when worn for a longer period of time (in the 6> subgroup) • The study concluded that because of this risk, the pathogens on the outer surface may cause self-contamination, with greater risk when worn for >6 hours • Indications that there should be a maximum time on mask usage |

| 48 | Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Environmental Conditions | The Lancet | May 2020 | B, G | Level 5: An experimental study on the stability of COVID-19 in different induced environmental conditions such as under heat stress and on different surfaces | • Infectious virus was not detected after 5-minute incubation at room temperature • Virus found to be stable at wide range of pH, and stable on surfaces such as outer lay of surgical masks • Virus was susceptible to disinfection methods |

| 49 | What You Need to Know About Infectious Disease | US Institute of Medicine | 2010 | C, D | Level 5: A book that contains expert opinion on infectious diseases and the nature of their transmission | • The mouth, the eyes and the nose are the body’s main entry points for transmittable conditions such as influenza • Coughing and sneezing facilitate the spread of droplet transmittable diseases |

| 50 | Face Touching: A Frequent Habit that Has Implications for Hand Hygiene | American Journal of Infection Control | February 2015 | C | Level 2b: A behavioural observation study of 26 participants exploring the habit of face touching | • Even among medical students, there was frequent face touching behaviour • This indicates towards the importance of hand hygiene too apart from the risk of self-inoculation from face touching which needs to be elucidated |

| 51 | Self-touch: Contact Durations and Point of Touch of Spontaneous Facial Self-touches Differ Depending on Cognitive and Emotional Load | PLOS ONE Medicine (Baltimore) | March 2019 | C | Level 2b: A cohort study exploring the behaviour of face touching and its link to cognitive and emotional loads | • Results showed that both the point of touch and contact durations were under influence from emotional and cognitive triggers |

| 52 | Protective Effect of Hand-washing and Good Hygienic Habits against Seasonal Influenza: A Case–Control Study | Medicine (Baltimore) | March 2016 | A | Level 3b: A single case–control study testing the link between influenza transmission and self-reported handwashing/unhealthy hygiene habits | • Frequent handwashing and better hygiene habits were associated with a reduction in the risk of influenza infection |

| 53 | Hand Hygiene and Risk of Influenza Virus Infections in the Community: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Epidemiology & Infection | May 2014 | A | Level 1a: A systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials aiming to evaluate the efficacy of hand hygiene measures against the reduction of influenza transmission | • Findings suggested that while hand washing may be effective (modest efficacy) against one mode of transmission, i.e. contact, further measures may also be important to control influenza transmission, for example face masks |

| 54 | Effect of Washing Hands with Soap on Diarrhoea Risk in the Community: A Systematic Review | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | September 2015 | A | Level 1a: A systematic review of 22 randomized controlled trials to compare diarrhoea occurrence in children and adults with or without handwashing measures | • Handwashing measures result in diarrhoea episode reductions in child day care centres in high-income countries as well as communities in low- and middle-income countries • It is a challenge to encourage the habitual maintenance of handwashing habits in people in the long term |

| 55 | Hand Washing Promotion for Preventing Diarrhoea | Cochrane Systematic Review | September 2015 | A | Level 1a: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and cluster RCTs to compare the effects of measures associated with handwashing on the occurrence of diarrhoea episodes in children | • Hand washing most likely reduces diarrhoea episodes in certain communities, as per the study’s findings • There may be lack of understanding on how to help people maintain habits related to handwashing in the long term |

| 56 | Reducing the Risk of Infection: Hand Washing Technique | Community Eye Health | March 2008 | A | Level 5: Expert guidance on components of a good handwashing route | Indicates that handwashing is critical to infection control and that there may be inadequate awareness on importance of handwashing techniques, which may be impeding effectiveness |

| 57 | The Effectiveness of Hand Hygiene Procedures in Reducing the Risks of Infections in Home and Community Settings Including Handwashing and Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizers | American Journal of Infection Control | December 2007 | A | Level 5: A report reviewing the evidence on hand hygiene and its link to infectious disease transmissions | • Hand hygiene is a significant component of good hygiene in households and communities and has significant benefit towards the reduction of infection transmission, including respiratory tract infections • Further conclusion that hand hygiene’s impact towards infectious disease reduction can be enhanced by improved persuasion of community handwashing (properly and at the right times) and that hand hygiene promotion should come hand in hand with other aspects of hygiene and associated education |

| 58 | Effectiveness of Commercial Face Masks to Reduce Personal PM Exposure | Science of the Total Environment | September 2018 | B | Level 5: A model-based study evaluating the efficacy of face mask respirators towards the reduction of airborne particle exposure and subsequent pollutant exposure | • Facemasks reduce exposure to urban pollution The efficacy of available face masks can vary in achieving exposure reduction to urban pollution |

| 59 | Exploring Motivations behind Pollution-Mask Use in a Sample of Young Adults in Urban China | Globalization and Health | December 2018 | B | Level 4: A cross-sectional survey exploring the role of socio-cognitive factors in affecting the decision of wearing a pollution mask in the context of young educated people | • Mask-wearing practice is influenced by various reasons including but not limited to level of education, social norms, self-efficacy, attitudes and past behaviour • The conclusion indicates the need towards changing the social perception towards mask-wearing practice |

| 60 | WHO | Air Pollution | WHO | N/A | B, I | Level 5: A collection of resources including global data on air pollution and subsequent protective measures | • Demonstrates that 9/10 people breathe air containing high levels of pollutants and concludes these as risk factors towards health |

| 61 | Air Pollution: A Smoking Gun for Cancer | Chinese Journal of Cancer | April 2014 | B | Level 5: A review on various articles to discuss key questions surrounding the link of air pollution with cancer incidence, with a focus on China | • Air pollution was and is a risk for cancer; it makes final recommendations such as the need for personal pollution monitoring devices as well as increase international collaborations upon this matter |

| 62 | A Retrospective Approach to Assess Human Health Risks Associated with Growing Air Pollution in Urbanized Area of Thar Desert, Western Rajasthan, India | Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering | January 2014 | B | Level 2b: A retrospective cohort study looking into the air pollution measures and associated statistics on disease burden | • Environmental burden of disease and association to air pollution is a main concern in the fast-developing areas of India • Households exposed to high vehicle-caused pollution presented with greater prevalence of respiratory diseases for example |

| 63 | Saliva and Viral Infections | Periodontology 2000 | December 2015 | C, E | Level 5: A review on various publications associated with viral infections via the oral cavity and discussing assays | • Regarding saliva and its role in viral infections, it indicates that it plays a key role and that the mouth and eye are common sites for viral entry • Conclusion that the oral cavity is a significant area for infection as well as virus transmission |

| 64 | Detection of Bacterial Pathogens in the Hands of Rural School Children Across Different Age Groups and Emphasizing the Importance of Hand Wash | Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene | June 2019 | C | Level 4: A cross-sectional observational study on hand pathogens in 200 rural school children | • Concluded that in this rural-based cohort, the hands of the children were harbouring various, potentially fatal, pathogenic organisms and could thus be a major source of infection • Indication towards the importance of hand washing and the need to provide materials (which are not available to these groups) in order to reduce spread of infection, which is otherwise reducible via hand hygiene |

| 65 | Viricidal Activity of World Health Organization-Recommended Formulations Against Enveloped Viruses, Including Zika, Ebola, and Emerging Coronaviruses | The Journal of Infectious Diseases | March 2017 | A | Level 5: An in vitro experiment testing the efficacy of two WHO recommended alcohol-based formulations against different enveloped viruses | • WHO recommended alcohol-based formulations worked against the different enveloped viruses and the viricidal effect was strong |

| 66 | Effect of Handwashing on Child Health: A Randomised Controlled Trial | The Lancet | July 2005 | A | Level 1b: A randomized controlled trial randomly assigning of handwashing promotion to one group and no promotion to the other versus randomized controls. Outcomes explored included diarrhoea and acute respiratory tract infections | • Study found that households receiving plain soap with handwashing promotion had lower incidence of the studied infections and that there was not much difference between plain versus antibacterial soap • Indicates the importance of such programs and distribution of soap • Concluding that handwashing was effective in preventing conditions like diarrhoea and respiratory disease |

| 67 | Hand Cleaning with Ash for Reducing the Spread of Viral and Bacterial Infections: A Rapid Review | Cochrane | April 2020 | A | Level 5: A systematic review using different types of studies to assess the advantages and disadvantages of ash as an alternative to soap or other materials against viruses and bacteria | • Studies were unreliable and rarely adequate examined rate of infection. Therefore, ash could not be concluded as a suitable alternative |

| 68 | Comparison of Four Methods of Hand Washing in Situations of Inadequate Water Supply | West African Journal of Medicine | January 2008 | A | Level 1b: A randomized controlled trial comparing different methods of hand washing developed for use in developing countries | • The ‘Elbow way’ of handwashing is the gold standard with no evidence of post-contamination • Bucket and bowl as well as the single-bowl method result in cross contamination |

| 69 | Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic? | Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness | August 2013 | A | Level 1b: A randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of different household materials in making homemade masks as an alternative to commercial face masks | • While a homemade mask also results in a decrease in number of microorganisms expelled by volunteers, a homemade mask is significantly less effective than surgical masks and should only be a last resort for droplet transmission prevention |

| 70 | Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks | American Chemical Society Nano | April 2020 | B | Level 5: An experimental approach to assess common fabrics (such as cotton) and their filtration efficiencies | • Found that in general, cloth masks could potentially offer notable protection against transmission of particles, which have sizes within the aerosol range • Further findings on factors limiting effectiveness such as leakages due to fitting issues and influence of factors such as humidity, repeated use and washing |

| 71 | Handwashing: Clean Hands Save Lives | Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet | February 2020 | A | Level 5: An expert collection of information on handwashing as well as the explanations behind it | Collects the key points on handwashing as well as the science behind the measure to ultimately make recommendations regarding when to wash and how to wash |

| 72 | Effectiveness of Handwashing in Preventing SARS: A Review | Tropical Medicine and International Health | September 2006 | A | Level 3a: A systematic review of case–control studies to evaluate effectiveness of handwashing in protecting against SARS transmission | • Only three studies out of the 10 reviewed were statistically significant • While there is no conclusive evidence on the effectiveness of handwashing, this measure remains suggestive to protect against SARS transmission in the community and healthcare settings |

| 73 | Efficacy of Handwashing Duration and Drying Methods | International Association for Food Protection | July 2012 | A | Level 1b: A randomized controlled trial on the impact of soap or plain water, duration of practice, presence of debris and drying method on microorganism removal from hands through handwashing | • The use of soap, longer duration of handwashing and towel drying significantly remove microorganisms compared to plain water, shorter duration and air drying, respectively • Towel drying presented with a greater person-to-person variability. The presence of food debris made handwashing less effective |

| 74 | Risk Factors for SARS among Persons Without Known Contact with SARS Patients, Beijing, China | Emerging Infectious Diseases | February 2004 | B | Level 3b: An individual case–control study to compare unlinked probable SARS patients with other community-based controls | • Concluded that chronic medical conditions, visit to fever clinics, eating outside home and frequent taxi taking were risk factors in case patients • Also indicated that mask wearing is strongly protective in reducing risk for SARS |

| 75 | Mass Masking in the COVID-19 Epidemic: People Need Guidance | The Lancet | March 2020 | B | Level 5: Expert opinion on the importance of plans for mass masking adoptions in the community under the emergence of COVID-19 | • Indicates that compulsory social distancing and mass masking are the measures that appear to be temporarily successful in China • Expresses that while the efficacy of mask wearing may be lacking evidence, the absence of evidence should not be equated to inefficacy, especially in the context of COVID-19 with limited alternatives. • Suggests that masking can intercept the transmission link and urges governments and health authorities to make advance preparations on mass masking locally to prepare for challenges ahead |

| 76 | The Role of Community-Wide Wearing of Face Mask for Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2 | Journal of Infection | April 2020 | B | Level 4: A cross-sectional observational study with epidemiological analysis on COVID-19 confirmed cases in Hong Kong with community-wide masking and that of non-mask-wearing countries | • Community-wide mask wearing may potentially improve COVID-19 control through reducing infected saliva and respiratory droplet emission from infected individuals |

| 77 | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO | N/A | B | Others: Provides latest figures on COVID-19 new cases, confirmed cases and deaths in a timely manner | • Latest figure updates on COVID-19 |

| 78 | To Mask or Not to Mask: Modelling the Potential for Face Mask Use by the General Public to Curtail the COVID-19 Pandemic | Infectious Disease Modelling | April 2020 | B, I | Level 5: A study on hypothetical mask adoption scenarios. Proposed model simulations were used to evaluate the effect of mask-wearing on mortality reduction and reduced COVID-19 transmission. | • Mask wearing by the general public may be potentially effective in reducing community transmission and relieving the pandemic burden • Suggests that the community-wide benefits are likely to be the most significant when face masks are used with other protection practices such as social distancing, and when adoption is nearly universal with a high compliance |

| 79 | Persistence of Coronaviruses on Inanimate Surfaces and Their Inactivation with Biocidal Agents | The Journal of Hospital Infection | March 2020 | C, G | Level 5: A literature review on the persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and chemical disinfection strategies for biocidal agent inactivation | • Human coronaviruses can persist on inanimate surfaces like metal, glass or plastic for up to 9 days • They can be efficiently inactivated using biocidal agents • Early containment and prevention of further COVID-19 spread is crucial |

| 80 | Turbulent Gas Clouds and Respiratory Pathogen Emissions: Potential Implications for Reducing Transmission of COVID-19 | Journal of the American Medical Association JAMA | March 2020 | D, I | Level 5: Expert opinion on turbulent gas clouds and respiratory pathogen emissions | • Suggests that pathogen-bearing droplets from a human sneeze can travel up to 7–8 m under forward momentum of the gas cloud • Indicates implications for prevention and precaution in COVID-19, including maintenance of distance away from infected individuals in healthcare settings |

| 81 | Human Saliva: Non-invasive Fluid for Detecting Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | March 2020 | E, H | Level 4: A case series on viral detection in saliva samples of COVID-19 patients on the first day of hospitalization | • Indicates consistent detection of coronavirus in saliva of COVID-19 patients admitted from first day of hospitalization • Demonstrates advantage of saliva sampling comfortability in epidemic situations such as COVID-19 • Suggests further investigation on human saliva diagnostic capacity for coronaviruses |

| 82 | Consistent Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Saliva | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Feb 2020 | E, H | Level 4: A case series on saliva viral load in self-collected saliva of COVID-19 patients | • Indicates consistent detection of live virus in saliva by viral culture • Suggests that saliva sampling is a promising and non-invasive method with high diagnostic, monitoring and infection control capacity in patients with COVID-19 infection |

| 83 | Microbiological Contamination of Environments and Surfaces at Commercial Restaurants | Ciência & Saúde Coletiva | 2010 | E | Level 5: A study on the levels of microbiological contamination on restaurant surfaces | • Extensive contamination by bacteria was observed in restaurant surfaces such as utensils, equipment and stainless steel benches • Suggests further sanitary measure to reduce risks of foodborne diseases |

| 84 | Contamination by Bacillus cereus on Equipment and Utensil Surfaces in a Food and Nutrition Service Unit | Ciência & Saúde Coletiva | September 2011 | E | Level 5: A study on the levels of microbiological contamination in food processing plants | Significant contamination by bacteria was identified in over 30% of the equipment and utensils studied in food processing plants |

| 85 | Detectable SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA in Faeces of Three Children During Recovery Period of COVID-19 Pneumonia | Journal of Medical Virology | March 2020 | F | Level 4: A case series in which information of COVID-19 infected children was collected, such as clinical characteristics and chest imaging | Concluded that SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA is detectable in the faecal samples of three children during their recovery from COVID-19 pneumonia |

| 86 | CUHK Finds that the Coronavirus Can Persist in Stool after Its Clearance in Respiratory Tract; Will Conduct Stool Test for People in Quarantine Camps for Early Identification | The Chinese University of Hong Kong | March 2020 | F, J | Level 4: A case series on the viral load of faecal samples from COVID-19 patients | • Concluded that all studied patients have COVID-19 virus detected in their faecal samples • For a minority of patients, virus was still present in the faecal sample 1–2 days after the respiratory sample tested negative |

| 87 | The Potential Spread of Infection Caused by Aerosol Contamination of Surfaces after Flushing a Domestic Toilet | Journal of Applied Microbiology | June 2005 | F | Level 5: A study to determine the level of aerosol formation and fall out within a toilet cubicle after toilet flushing through mimicking infectious diarrhoea | • Large numbers of microorganisms remained on the toilet bowl surface and in the bowl water, which are further dispersed to the air through further toilet flushing. • Indicates potential health risk to individuals who are unaware of this mode of transmission within the household |

| 88 | Lifting the Lid on Toilet Plume Aerosol: A Literature Review with Suggestions for Future Research | American Journal of Infection Control | October 2012 | F | Level 5: A review on the potential health risks of aerosol production during toilet flushing | • Toilet plume under toilet flushing may contribute to infectious disease transmission • Further research to assess toilet plume risks, especially in healthcare settings, is encouraged |

| 89 | Respiratory Hygiene and Cough Etiquette | Infection Control in the Dental Office | April 2020 | D | Level 5: Expert opinion on respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette | • Prevention is the best method for respiratory disease management • Proper hand hygiene and awareness on cough and sneeze etiquette is encouraged for successful prevention |

| 90 | Bacterial Transfer from Mouth to Different Utensils and from Utensils to Food | Graduate School of Clemson University | August 2009 | E, H | Level 5: A study on the transfer of bacteria from mouth to different utensils | • There is a significant bacterial transfer from mouth to utensils and further to food |

| 91 | Helicobacter pylori: Epidemiology and Routes of Transmission | Epidemiologic Reviews | July 2000 | E, H | Level 5: A review on the epidemiology and routes of transmission of Helicobacter pylori | • H. pylori infection is prevalent in Chinese immigrants in Australia who share chopsticks for communal dishes • A common mode of H. pylori transmission involves an oral-to-oral route through saliva |

| 92 | Potential for Aerosolization of Clostridium difficile after Flushing Toilets: The Role of Toilet Lids in Reducing Environmental Contamination Risk | The Journal for Hospital Infection | December 2011 | F | Level 5: A study on in situ testing using faecal suspensions to mimic disease bacteria and measure microorganism aerosolization as well as extent of splashing when toilet flushing | • Lidless toilets may lead to environmental contamination by microogranisms and associated health risks. Use of lidless toilets is thus discouraged. |

| 93 | Mobility Decline in Old Age: A Time to Intervene | Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews | January 2013 | D | Level 5: Expert opinion on mobility impairment in ageing populations | • Mobility decline is prominent in the old aged • It is important for behavioural measures to be in place for mobility function improvement • Further rigorous clinical trials are needed • The treatment and prevention of mobility impairments through expert collaboration are essential |

| 94 | Age-related Change in Mobility: Perspectives from Life Course Epidemiology and Geroscience | The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences | March 2016 | D | Level 5: Expert opinion on mobility impairment in ageing populations, explored through the perspectives of epidemiology and geroscience | • Physical deterioration in older persons results in mobility loss and impairment • It is important for behavioural measures to be in place to reduce the disability burden in populations |

| 95 | Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean | Science | February 2015 | E | Level 5: A report on the estimation of plastic waste mass in oceans by linking relevant worldwide data | • The amount of plastic waste generated across 192 coastal countries is determined • The major determining factors of a country’s contribution to plastic waste would be population size and waste management system quality • An estimation is made on the cumulative plastic waste quantity if waste management infrastructure is not improved |

| 96 | Microplastic Contamination of Wild and Captive Flathead Grey Mullet (Mugil cephalus) | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | March 2018 | E | Level 5: An investigation on microplastic ingestion in flathead grey mullets | • There was evidence of microplastic ingestion in the mullets • Individual, local and global actions to counteract the issue of plastic waste disposal into seas are encouraged |

| 97 | CityU Experts: Aerosol Droplets from Toilet Flushing Can Rise Up to One Metre; Covering Toilet Lid may not Completely Eliminate Disease Transmission; Toilet Bowl Must Be Regularly Cleaned | The City University of Hong Kong | February 2020 | F | Level 5: A study on how toilet flushing may produce aerosol droplets that facilitate disease transmission | • A single toilet flush can contaminate the washroom through the spread of pathogens in the air • The covering of toilet lid before flushing for washroom and air contamination reduction is recommended • Toilet lid covering may not completely inhibit pathogenic dissemination due to potential space between the lid and the bowl |

| 98 | The Coronavirus Pandemic and Aerosols: Does COVID-19 Transmit via Expiratory Particles? | Aerosol Science and Technology | April 2020 | D | Level 5: Expert opinion on the potential of COVID-19 transmission through expiratory particles | • Aerosol transmission may play a major role in the high transmissibility of COVID-19 • Ordinary speech has a potential of aerosolizing respiratory particles. • There are scientific unknowns relating to the mode of transmission It is important for experts to collaborate closely and effectively inform the public of potential infectious aerosol emission all the time, such as during coughing and sneezing |