Abstract

A series of urea/thiourea substituted benzoxaboroles was investigated for the inhibition of the three carbonic anhydrases encoded by Vibrio cholerae (VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ). In particular, benzoxaborole derivatives were here first assayed for the inhibition of a γ-class CA, extending the panel of CA classes that benzoxaboroles efficiently target beyond α and β. Inhibition profiles demonstrated that VchCAα was significantly more inhibited compared to VchCAγ and, in turn, more efficiently modulated than VchCAβ. Among the many selective benzoxaborole ligands detected against VchCAα over the off-target hCA II, compound 18, a p-NO2-phenylthiourea derivative, even exhibited a fully selective inhibition profile against the three VchCAs over hCA II. A comprehensive ligand/target interaction study was performed in silico for all three VchCA isoforms providing the first molecular modeling investigation with inhibitors of a γ-class CA to the best of our knowledge. The present study reinforces the rationale behind the use of benzoxaboroles as innovative antibacterial agents with a new mechanism of action, furnishing suggestions for the rational design of new potent and selective inhibitors targeting V. cholerae CAs over human off-target ones.

Keywords: Carbonic anhydrase, inhibitors, benzoxaborole, Vibrio cholerae, in silico study

Cholera is a highly contagious acute diarrheal disease due to a Gram-negative bacillus, Vibrio cholerae. Morbidity and mortality associated with this disease remain a significant problem in the developing world. Even if the prognosis is good with appropriate treatment, with a mortality rate of <0.2%, without treatment, the mortality rate can be as high as 50–70%.1 The number of worldwide deaths due to the infection is estimated between 21 000 and 143 000.2 Among the Vibrio cholerae species, we can distinguish two toxigenic strains belonging to the serogroups O1 or O139 responsible for cholera.1,3 The treatment of this disease involves immediate rehydration (preferably) with oral rehydration solutions containing salt and glucose or with rice-based rehydration solutions and/or isotonic solutions intravenously to compensate for the massive hydro-electrolytic losses observed in individual patients. The adjunctive treatment is based on the oral administration of antibiotics such as tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides. Besides, this procedure is beneficial in moderate to severe cases. Two oral inactivated cholera vaccines are available, WC/rBS (licensed in the USA) and BivWC (used in endemic areas), inoculated in 2 or 3 doses and providing 60–85% protection for 2–3 years.1−4 However, there are strains of V. cholerae resistant to tetracycline, and sometimes polyresistant to various antibiotics.5−7

To assist the colonization of human hosts, V. cholerae secretes virulence factors, among which the main is the cholera toxin (CT). It is now established that the production of cholera toxin is essential for the prospect of acquiring the potential to cause epidemics by a serogroup. This has become particularly evident since the emergence of serogroup O139. The effects of cholera toxin are massive diarrhea, but the microorganism must first have escaped many of the host’s nonspecific defense mechanisms to colonize the small intestine successfully. Therefore, enterotoxic strains of V. cholerae must survive the acidity of the stomach, colonize the intestine, and excrete sufficient cholera toxin to produce the diarrheal response associated with cholera.6−8 New treatment therapies that target virulence genes, toxin production, and colonization by V. cholerae, either alone or in combination with current therapies, could be beneficial in reducing the global health burden caused by this pathogen, as alternatives to antibiotics become increasingly needed.5,6

One of the key physiological reactions for the life cycle of most organisms, including bacteria, is the hydration/dehydration of CO2. This critical reaction is connected with numerous metabolic pathways, such as the biosynthetic processes requiring CO2 or HCO3– and biochemical pathways, including pH homeostasis, secretion of electrolytes, and transport of CO2 and bicarbonate among others.9 The reversible hydration of CO2 is catalyzed by essential enzymes carbonic anhydrases (CAs), which belong to a superfamily of zinc metalloenzymes. Vibrio cholerae encodes carbonic anhydrases belonging to α-CA, β-CA, and γ-CA classes (VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ)10−15 that play an important role in the supplementation of CO2 and bicarbonate for the bacterial cellular metabolism and pH homeostasis.16−18 These three CAs could represent potential targets for the development of anti-infectives targeting V. cholerae colonization.19 The 3D structure of VchCAβ was solved by X-ray crystallography in 2015 revealing a tetrameric type II β-CA (Figure 1A).13 Structural information was not collected to date for VchCAα and VchCAγ. In contrast, the structures of α- and γ-class CAs from other bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori or Thermus thermophilus, were reported20,21 and depicted in Figure 1B–C.

Figure 1.

Ribbon representation of (A) the tetrameric type II VchCAβ (pdb 5CXK) [13]; (B) α-CA from H. pylori as monomer in complex with the CAI acetazolamide (pdb 4YGF);20 (C) active trimer of the γ-CA from T. thermophilus (pdb 6IVE) in adduct with phosphate.21

In our current research studies, searching for new chemotypes for the design of carbonic anhydrase, we develop new inhibitors in the benzoxaborole series, which demonstrated very potent inhibitory activity against human CAs isoforms as well as fungi and parasites CAs.22−27 Therefore, the purpose of our work is to provide new information about the potential of benzoxaboroles as potential inhibitors of the three CAs-classes of Vibrio cholerae, with a main focus on VchCAγ, as no benzoxaborole derivative has been assayed to date for this class of CAs. Additionally, a thorough interaction study in silico is here reported with benzoxaborole derivatives and the three VchCA isoforms. To the best of our knowledge, we described here the first molecular modeling investigation with inhibitors of a γ-class CA.

Inhibition data of benzoxaboroles 1–23 against VchCAs of α-, β-, and γ-classes were measured by a stopped flow CO2 hydrase assay28 and are shown in Table 1. Acetazolamide (AAZ) a clinically used sulfonamide inhibitor, was used as standard. Tavaborole (TVB), a benzoxaborole commercially used as topical antifungal medication, was included in the inhibition assay (Figure 2).

Table 1. Inhibition Data of hCA II, VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ with Benzoxaboroles 1–23, TVB, and the Standard Sulfonamide Inhibitor AAZ by a Stopped Flow CO2 Hydrase Assay28.

|

KI(nM)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | X | R | VchCAα | VchCAβ | VchCAγ | hCA II |

| 1 | 319 | 70313 | 2837 | 8180 | ||

| 2 | 142 | 8866 | 818 | 504 | ||

| 3 | 165 | 21830 | 1168 | 590 | ||

| 4 | O | CH2Ph | 90 | 42143 | 1874 | 439 |

| 5 | O | CH2-(3-Cl,5-CH3-Ph) | 53 | 61318 | 718 | 276 |

| 6 | O | Ph | 117 | 56351 | 705 | 730 |

| 7 | O | 4-Cl-Ph | 56 | 19532 | 650 | 707 |

| 8 | O | CH2-fur-2-yl | 164 | 79946 | 1229 | 841 |

| 9 | O | 4-F-Ph | 48 | 28046 | 644 | 480 |

| 10 | O | 4-CF3-Ph | 46 | 55124 | 957 | 456 |

| 11 | O | 2,4,6-Cl-Ph | 76 | 84459 | 895 | 272 |

| 12 | O | 2-OCH3,5-CH3-Ph | 556 | 67286 | 410 | 89 |

| 13 | O | 4-COCH3-Ph | 103 | 65084 | 1128 | 797 |

| 14 | S | CH2CH2Ph | 102 | 18372 | 554 | 1547 |

| 15 | S | 4-CH3-Ph | 109 | 2586 | 1762 | 1253 |

| 16 | S | napht-2-yl | 603 | 25994 | 2974 | 1148 |

| 17 | S | 4-OCH3-Ph | 165 | 2297 | 874 | 1250 |

| 18 | S | 4-NO2-Ph | 80 | 933 | 687 | >104 |

| 19 | S | CH2Ph | 96 | 30408 | 3955 | 1305 |

| 20 | S | 4-F-Ph | 112 | 6350 | 544 | 1500 |

| 21 | S | CH2-fur-2-yl | 220 | 31939 | 1996 | 2230 |

| 22 | S | 4-CF3-Ph | 72 | 1253 | 1919 | 1838 |

| 23 | S | Ph | 1204 | 19128 | 834 | 1625 |

| TVB | 157 | 97278 | 841 | 462 | ||

| AAZ | 6.8 | 451 | 473 | 12 | ||

Mean from 3 different assays, by a stopped flow technique (errors were in the range of ±5–10% of the reported values).

Figure 2.

Structure of benzoxaboroles evaluated against VchCAs and standard CAI.

Inhibitory profiles were displayed as inhibition constants (KIs) in comparison with those against the main physiological human isoform hCA II, off-target in this study (Table 1). The following structure activity relationship can be worked out on the basis of data from Table 1.

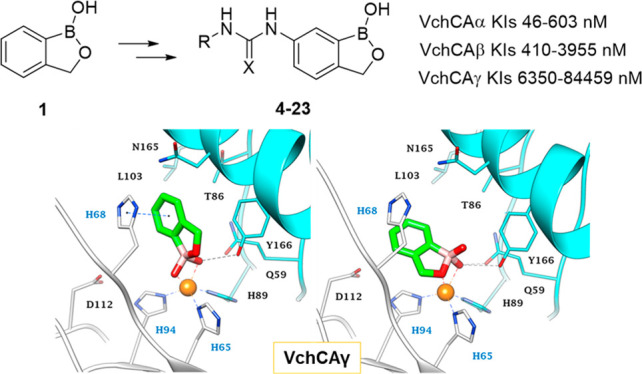

Significantly different inhibition profiles were measured with benzoxaborole 1–23 and tavaborole against VchCA isoforms α (KIs in a medium to high nM range), β (KIs in a medium to high μM range), and γ (KIs in a high nM to low μM range). In detail, the CO2 hydration activity of VchCAα was the most affected by the tested benzoxaboroles derivatives that showed KIs in the range 46–603 nM. Compound 23 only acted as a micromolar inhibitor (KI of 1.2 μM). This makes VchCAα even more inhibited by these benzoxaboroles than hCA II, the physiologically most relevant among hCAs (KIs ranging from 89 nM to 10 μM). The most effective VchCAα inhibitors were the halogenated ureido compounds 5, 7, and 9–11 with KIs spanning between 46 and 76 nM. Among the thioureido inhibitors, the trifluoromethylphenyl derivative 22 also showed an inhibitory activity of 72 nM against this α-CA, while the other halo-compound 20 displayed a KI above 100 nM. Among thioureas, a comparable KI was shown by the nitrophenyl derivate 18 (KI of 80 nM). The detachment of the aryl ring from the (thio)ureido linker by a 1 or 2 carbon units spacer produced a slight enhancement in the inhibitory action against VchCAα. This occurs with ureas 4 and 6 (KIs of 90 and 117 nM, respectively), and it is even more evident with thioureas 14, 19, and 23 (KIs of 102, 96, and 1204 nM, respectively). The 10-fold decrease of CAI efficacy measured swapping the oxygen atom of 6 to a sulfur, as in 23, suggests a loss of favorable ligand/target interactions or clashes induced by the S atom. The addition of substituents to the ring or, as aforesaid, its separation from the thioureido spacer, appears to restore favorable binding contacts to the target and thus KIs in a medium nanomolar range. It should also be stressed that several (thio)ureido substitutions (e.g., in 6, 8, 12, 13–16, 20, 21, and 23) did not produce a relevant breakthrough in the binding to VchCAα with respect to the simple benzoxaborole 1, its 6-NO2 (2), and 6-NH2 (3) derivatives and tavaborole that shows KIs between 142 and 319 nM.

Intriguingly, VchCAγ was markedly more inhibited than VchCAβ with KIs in the range 410–3955 nM. This is a relevant result as VchCAγ is the first γ-CA ever tested for inhibition by benzoxaborole derivatives. This widens the set of CA classes potently affected by such a CAI scaffold and, as a result the chorus of pathogens can be hit pharmacologically with benzoxaboroles (i.e., those encoding for γ-class CAs). The SAR against VchCAγ significantly differs from that illustrated for VchCAα. A rather flat inhibition trend was observed on the whole, with most inhibitors displaying KI values in the narrow span 544–1996 nM. The ureido derivative 12 harboring a 2-OCH3, 5-CH3-phenyl group solely went below 500 nM as far as the KI value against VchCAγ is concerned. On the other hand, the simple benzoxaborole 1 and thioureas 16 and 19 only exhibited KIs against this isozyme above 2.5 μM (2.8, 2.9, and 3.9 μM, respectively). In other words, most derivatization of the benzoxaborole scaffold of 1 increased VchCAγ inhibition, solely except for a naphthyl (16) or benzyl (19) tail within the thioureas subset. Of note, again the spacing of the outer aromatic ring by the linker had a detrimental effect on VchCAγ inhibition within the urea subset (KI more than doubled from 6 to 4) and partially in the thiourea subset (KI almost increased 5-fold from 23 to 19), as the further elongation of the linker up to 2-carbon atoms (14) brought back the KI to a medium nanomolar value (554 nM).

VchCAβ was the least inhibited by benzoxaboroles 1–23 among the isoforms encoded by V. cholerae. In fact, most inhibitors displayed KIs spanning in the range 6350–84459 nM. Thioureas 18 and 22 were the two best VchCAβ inhibitors, solely reporting KIs approaching 1 μM (933 and 1253 nM, respectively). Right after in terms of inhibition potency are again two thioureido compounds, namely the p-methyl and p-methoxy phenyl 15 and 17 (KIs of 2.6 and 2.3 μM). It is of interest that, against VchCAβ, thioureido derivatives showed a better inhibitory effectiveness on the whole with respect to ureas 4–13. In fact, the remaining thioureas showed KIs not overcoming the value of 31.9 μM (21), whereas most ureido derivatives reported inhibition constants in the range 42.1–84.4 μM, except for the p-halo compounds 7 and 9 (KIs of 19.5 and 28.0 μM). Interestingly, when the unsubstituted benzoxaborole 1 was again among the weakest VchCAβ inhibitors, its substitution in position 5, as in tavaborole, even worsened the affinity to the target producing the worst KI value of the study against the β-class isozyme.

As mentioned above, the measured inhibition of VchCAα by benzoxaboroles 1–23 is even greater than that previously reported against hCA II. In fact, the selectivity index (SI) calculated for VchCAα over hCA II (Table 2) is chiefly above 1, solely except for compound 12, which is instead more active against hCA II.

Table 2. Selectivity Index (SI) of Benzoxaboroles 1–23, TVB, and AAZ Calculated as CA II/VchCA KIs Ratio.

|

Selectivity Index (SI) over hCA II |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | X | R | VchCAα | VchCAβ | VchCAγ |

| 1 | 25.6 | 0.1 | 2.9 | ||

| 2 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | ||

| 3 | 3.6 | <0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| 4 | O | CH2Ph | 4.9 | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| 5 | O | CH2-(3-Cl,5-CH3-Ph) | 5.2 | <0.1 | 0.4 |

| 6 | O | Ph | 6.2 | <0.1 | 1.0 |

| 7 | O | 4-Cl-Ph | 12.6 | <0.1 | 1.1 |

| 8 | O | CH2-fur-2-yl | 5.1 | <0.1 | 0.7 |

| 9 | O | 4-F-Ph | 10.0 | <0.1 | 0.7 |

| 10 | O | 4-CF3-Ph | 9.9 | <0.1 | 0.5 |

| 11 | O | 2,4,6-Cl-Ph | 3.6 | <0.1 | 0.3 |

| 12 | O | 2-OMe,5-CH3-Ph | 0.2 | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| 13 | O | 4-COCH3-Ph | 7.7 | <0.1 | 0.7 |

| 14 | S | CH2CH2Ph | 15.2 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| 15 | S | 4-CH3-Ph | 11.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 16 | S | napht-2-yl | 1.9 | <0.1 | 0.4 |

| 17 | S | 4-OCH3-Ph | 7.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| 18 | S | 4-NO2-Ph | >125.0 | >10.7 | >14.6 |

| 19 | S | CH2Ph | 13.6 | <0.1 | 0.3 |

| 20 | S | 4-F-Ph | 13.4 | 0.2 | 2.8 |

| 21 | S | CH2-fur-2-yl | 10.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| 22 | S | 4-CF3-Ph | 25.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| 23 | S | Ph | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| TVB | 2.9 | <0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| AAZ | 1.8 | <0.1 | <0.1 | ||

A computational protocol consisting of joint docking and MM-GBSA and MD simulations was undertaken to explore in-depth the inhibitory profiles of benzoxaboroles 1–23 toward VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ.

Benzoxaboroles were shown to act as zinc-binder CAIs against hCA II in the form of their conjugated Lewis base. Compounds 1–4, 6, 12, 19, and 23 were observed in the tetrahedral anionic B(OH)2– form as tetra- and/or pentacoordinated around the metal atom in the hCA II active site.22 A subsequent in silico study showed that the same benzoxaborole derivatives can only exhibit a tetrahedral coordination geometry around the Zn2+ in the narrower active site of β-CAs from fungi.23 Thus, docking studies were performed considering the benzoxaborole B(OH)2– anion form.

Representative ligands were submitted to QM geometry optimization (B3LYP/6-31G*+) and ESP charges computation prior to docking the molecules into the homology-built models of VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ and verifying the adducts stability by MD simulations. In fact, the pdb database only contains the 3D coordinates for VchCAβ that however is present in the type II or closed form of the enzyme (PDB 5CXK)13 and thus not suitable for docking aims. The HM models were respectively developed using as templates the solved coordinates of α-CA from Photobacterium profundum (5HPJ), type-Ι β-CA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (6D2N) and γ-CA from Escherichia coli (3TIO). The templates show the highest sequence identity percentage with the targets, namely 53%, 52%, and 61%, respectively (Figures S1–S9, Tables S1–S3, Supporting Information). The best scored HM-built models were used to figure out the binding mode of representative benzoxaboroles within VchCAs active sites. ΔG binding energies were computed by a MM-GBSA method, and the stability of the predicted ligand/target adducts was evaluated by 100 ns MD. The structure of the three investigated CA isoforms was stable during the computation with the backbone atom RMSDs exhibiting small fluctuations over the course of the dynamic. As well, all docked binding orientations showed a significant stability along the MD, with the Zn coordination being firmly maintained (Figures S10–S12, Supporting Information).

Despite the structural differences between VchCAα and hCA II (i.e., the hCA II α-helix structural motif residues ranging from 129 to 135 are replaced in VchCAα by a short coil formed by residues 128–132), benzoxaborole derivatives share similar interaction features within the bacterial and human isozymes.

In fact, the predicted binding mode for the unsubstituted benzoxaborole 1 in VchCAα strictly resembles the interaction mode within hCA II,22 and two main binding solutions, featured by almost the same interaction energy values with the target, were found with different coordination geometry, namely a tetrahedral (t, Figure 3A) and a trigonal bipyramid (p, Figure 3B). In the tetracoordinated form, the fourth coordination position about the metal ion is occupied by one hydroxyl group on the boron atom, that also forms a H-bond with the T189 side chain (95% stable along the MD); the other B–OH is involved in a bifurcated H-bond with the T189 backbone NH (92%) and the side chain hydroxyl group of T190 (81%). In the pentacoordinated pose, the cyclic oxygen atom additionally binds the Zn2+, and similar H-bonds as above only occur with T189, involving the residue side chain OH (97%) and the backbone NH (94%) groups, respectively. Moreover, a 65% stable water bridged H-bond occurs between the coordinating OH and H79. The position of the heterocycle in both orientations is further stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with residues from the lipophilic half of the binding cavity (V125, V135, L133, L188, and P192).

Figure 3.

Predicted binding mode of 1 (green) and 10 (blue) within VchCAα active site. (A) Tetrahedral (t); (B and C) trigonal bipyramid (p) coordinated poses of compounds 1 and 10, respectively. H-bonds and π–π interactions are shown as black and blue dashed lines, respectively. Water molecules are represented as red spheres.

The introduction of a bulky substituent at the 6 position of the benzoxaborole scaffold, as in derivative 10, the most potent VchCAα inhibitor, only enables a p-like binding mode, with the formation of H-bonds of stability comparable to those of derivative 1. The 4-CF3-phenyl-ureido pendant accommodates into the pocket formed by W23, H79, and P191, establishing π–π (43%) and VdW interactions (Figure 3C). A water bridged H-bond network occurring between the ureido oxygen atom and the N77 (53%) and Q82 (32%) side further stabilizes the adduct.

The binding site of the active VchCAβ dimer, as the other members of the β-CAs family, locates at the interface and is composed by amino acids from the two monomers forming the dimer (Figure 4). The zinc ion is coordinated by a His and two Cys residues belonging to the same monomer.

Figure 4.

Predicted binding mode for 1 and 18 within the type-I VchCAβ active site. Tetrahedral (t) coordinated poses of compounds (A) 1 and (B) 18. H-bonds and π–π interactions are shown as black and blue dashed lines, respectively. Water molecules are represented as red spheres. The labels of amino acids from different chains are colored differently.

The in silico insights showed that the narrow active site of VchCAβ can accommodate benzoxaborole derivatives only as stably tetracoordinated (t) around the Zn(II) ion (Figure 4). The binding orientation is stabilized by multiple interactions with Y83: a Y83-OH···O–B interaction involving the second OH group of the ligand (that not coordinated to the Zn2+) and the hydroxyl group of the residue (67%); a π–π stacking interaction between the benzene ring of 1 and the phenyl ring of the amino acid (75%). In addition, the same OH group donates a H-bond to the D44 side chain carboxylate (69%) and is in H-bond contact with G100 (43%) through a bridged water molecule whereas the benzoxaborole endocyclic oxygen acts as an acceptor forming another H-bond with the Q33 side chain (58%). Moreover, the binding pose is further stabilized by vdW interactions with F61, V66, I116, and L120 (Figure 4A). However, the dynamic behavior of this adduct highlighted an overall reduced stability of the pose over the 100 ns long simulation (Figure S11, Supporting Information). This might probably be related to the enclosed, restricted active site of VchCAβ, when compared to other β-CAs (e.g., Can2),23 that prevents a consistent pose stabilization and induces the lower inhibitory profile of the benzoxaboroles against VchCAβ compared to VchCAα, VchCAγ, and Can2.

The predicted interaction mode for compound 18, the most effective VchCAβ inhibitor here, highlighted how the flexibility of the (thio)ureido linker allows the pendant in position 6 to accommodate in the lipophilic pocket formed by A106, L113, and I116 (Figure 4B). MD simulations pointed out that the persistence of the H-bonds involving the zinc binding group is enhanced by 10–15%, as well as the pose stability over the MD, with respect to derivative 1 (Figure S11, Supporting Information). The lodging of the X ureido atom in the inner portion of the aforesaid lipophilic cleft can support the more effective inhibitory action of thioureido over ureido derivatives. The p-NO2 group in 18 (and presumably the CF3 in 22, the second most potent VchCAβ inhibitor) favors water bridged H-bonds with residues at the outer rim of the binding cavity such as D109 (38%).

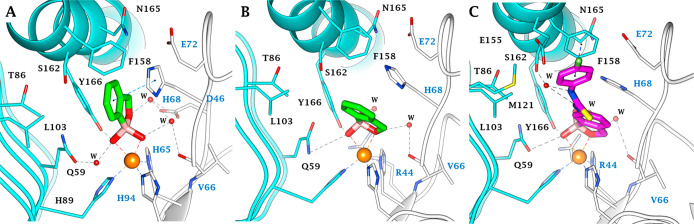

Likewise, the active site of the trimer VchCAγ, as other γ-CAs, locates at the interface and is composed by amino acids belonging to two distinct monomers (Figures 5 and 6). In the case of VchCAγ, the zinc ion is coordinated by three His residues belonging to distinct chains. Unlike VchCAβ, the active site of VchCAγ is roomy enough to accommodate two alternative stable pentacoordinated orientations (p1 and p2) for benzoxaborole 1 (Figures 5, 6, and S7, Supporting Information). In p1, the dual coordination around Zn2+ occurs by both OH groups of the ligand, with one also involved in a direct and a water mediated H-bond with the phenolic group of the Y166 (74%) and Q59 side chain (48%). The other OH and the endocyclic oxygen atom are water bridged with the V66 backbone C=O (37%) and the D46 (32%) side chain carboxylate (Figures 5A and 6A). Additionally, the benzene ring of 1 is sandwiched between H68 and T86, forming π–π (56%) and π–alkyl interactions with these residues. In p2, the endocyclic oxygen atom and an OH group of the ligand coordinate around the zinc ion. The p2 binding orientation is stabilized by two H-bonds with the phenolic group of Y166 and the amide side chain of Q59 (72% and 61% stable, respectively). The other OH and the cyclic oxygen atom are involved in 42% and 21% stable water bridges with the V66 backbone C=O and R44 side chain (Figures 5B and 6B). Moreover, it is in hydrophobic contact with T67, H68, and H94 (Figure 5B and 6B). From an energetical point of view, the p2 binding mode is favored over p1 (dG −52.34 kcal/mol vs −46.83 kcal/mol). Interestingly, the 6-ureido derivatives bind in the active site by a p2-like mode (Figure 6C), conserving a similarly stable H-bond network as described for derivative 1. The 4-F-phenylureido group of inhibitor 20, the most active against VchCAγ, extends toward the lipophilic half of the active site, interacting through a π–π interaction (45%) and VdW contacts with L103, M121, and F158. Further, the ureidic NH are commonly implicated in a water bridge with the S162 side chain (approximately 55% stable).

Figure 5.

Predicted binding poses of 1 and 20 in the VchCAγ active site: (A) p1 and (B) p2 of derivative 1 and (C) compound 20. H-bonds and π–π interactions are shown as black and blue dashed lines, respectively. Water molecules are represented as red spheres. The labels of amino acids from different chains are colored differently.

Figure 6.

Alternative view of the (A) p1 and (B) p2 interaction modes of 1 and (C) 20 in the VchCAγ active site. H-bonds and π–π interactions are shown as black and blue dashed lines, respectively. Water molecules are represented as red spheres. The labels of amino acids from different chains are colored differently.

In conclusion, a series of urea/thiourea substituted benzoxaboroles was investigated for the inhibition of the three CAs from Vibrio cholerae (VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ). In this study, benzoxaborole derivatives were first assayed to inhibit a γ-class CA, widening the panel of CA classes significantly affected by such a type of CAIs. The inhibitory activity was more intense against VchCAα compared to VchCAγ, which, in turn, showed an inhibition more potent respect to VchCAβ. Selective benzoxaborole derivatives were detected against VchCAα with a high selective index against the off-target hCA II. A compound was identified, namely the p-NO2-phenylthiourea 18, which exhibited a selective inhibitory action against all VchCAs over hCA II.

Additionally, an exhaustive in silico ligand/target interaction study was carried out with all three VchCA isoforms, including, to the best of our knowledge, the first molecular modeling investigation with inhibitors of a γ-class CA. The computational analysis showed that benzoxaborole derivatives adopt both a tetrahedral and trigonal bipyramidal zinc-coordination in complex with VchCAα and two alternative pentacoordinated geometries around the zinc ion in VchCAγ active site. In contrast, the active site of VchCAβ, narrower than that of the other VchCAs as well as of other β-CAs (i.e., Can2 from C. neoformans), was able to accommodate benzoxaborole derivatives bound to the zinc ion only by a tetrahedral geometry, with a lower stability emerging as a result of the 100 ns long MD.

The above findings indicate that benzoxaboroles represent an interesting chemotype worth developing as innovative antibacterial agents since they possess a new mechanism of action and isoform selectivity preferentially against the bacterial expressed CAs. This study enriches the inhibitory profiles database for the different Vibrio cholerae CA-classes. Furthermore, it furnishes suggestions for the rational design of new potent and selective inhibitors targeting V. cholerae CAs over human off-target ones.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche LabEx CheMISyst (ANR-10-LABX-05-01).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- CAI

carbonic annhydrase inhibitor

- AAZ

acetazolamide

- TVB

tavaborole

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00403.

Sequence alignment of VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ; 3D representation and parameters of homology models of VchCAα, VchCAβ, and VchCAγ and templates; supplemental modeling figure and materials and methods. (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Weil A. A.; Ryan E. T. Cholera: recent updates. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31 (5), 455–461. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO World Health Organization . Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cholera#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 2020-04-29).

- Deen J.; Mengel M. A.; Clemens J. D. Epidemiology of cholera. Vaccine 2020, 38 (Suppl 1), A31–A40. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J. D.; Nair G. B.; Ahmed T.; Qadri F.; Holmgren J. Cholera. Lancet 2017, 390 (10101), 1539–1549. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C.; Oliver J. D.; Alam M.; Ali A.; Waldor M. K.; Qadri F.; Martinez-Urtaza J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4 (1), 8. 10.1038/s41572-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendrakumar L.; Gupta S. S.; Johnson J. B.; Ramamurthy T.; Thomas S. Molecular Adaptations and Antibiotic Resistance in Vibrio cholerae: A Communal Challenge. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25 (7), 1012–1022. 10.1089/mdr.2018.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B.; Verma J.; Kumar P.; Ghosh A.; Ramamurthy T. Antibiotic resistance in Vibrio cholerae: Understanding the ecology of resistance genes and mechanisms. Vaccine 2020, 38 (Suppl 1), A83–A92. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson J. S.; Withey J. H.; DiRita V. J. Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75 (12), 5542–9. 10.1128/IAI.01094-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. Biomedical applications of prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018, 28 (10), 745–754. 10.1080/13543776.2018.1497161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S.; Isik S.; Vullo D.; De Luca V.; Carginale V.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. DNA cloning, characterization, and inhibition studies of an α-carbonic anhydrase from the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (23), 10742–8. 10.1021/jm301611m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S.; De Luca V.; Scozzafava A.; Carginale V.; Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. Biochemical properties of a new α-carbonic anhydrase from the human pathogenic bacterium, Vibrio cholerae. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2014, 29 (1), 23–7. 10.3109/14756366.2012.747197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S.; Vullo D.; De Luca V.; Carginale V.; Ferraroni M.; Osman S. M.; AlOthman Z.; Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. Sulfonamide inhibition studies of the β-carbonic anhydrase from the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24 (5), 1115–20. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraroni M.; Del Prete S.; Vullo D.; Capasso C.; Supuran C. T. Crystal structure and kinetic studies of a tetrameric type II β-carbonic anhydrase from the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2015, 71 (Pt 12), 2449–56. 10.1107/S1399004715018635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S.; Vullo D.; De Luca V.; Carginale V.; Osman S. M.; AlOthman Z.; Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. Comparison of the sulfonamide inhibition profiles of the α-, β- and γ-carbonic anhydrases from the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26 (8), 1941–6. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S.; Vullo D.; De Luca V.; Carginale V.; di Fonzo P.; Osman S. M.; AlOthman Z.; Supuran C. T.; Capasso C. Anion inhibition profiles of α-, β- and γ-carbonic anhydrases from the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24 (16), 3413–7. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuaita B. H.; Withey J. H. Bicarbonate Induces Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression by enhancing ToxT activity. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77 (9), 4111–20. 10.1128/IAI.00409-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J. J.; Withey J. H. Bicarbonate increases binding affinity of Vibrio cholerae ToxT to virulence gene promoters. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 3872–80. 10.1128/JB.01824-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobaxin M.; Martínez H.; Ayala G.; Holmgren J.; Sjöling A.; Sánchez J. Cholera toxin expression by El Tor Vibrio cholerae in shallow culture growth conditions. Microb. Pathog. 2014, 66, 5–13. 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso C.; Supuran C. T. Inhibition of bacterial carbonic anhydrases as a novel approach to escape drug resistance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1237–48. 10.2174/1568026617666170104101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modakh J. K.; Liu Y. C.; Machuca M. A.; Supuran C. T.; Roujeinikova A. Structural basis for the inhibition of Helicobacter pylori α-carbonic anhydrase by sulfonamides. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127149 10.1371/journal.pone.0127149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Zhang Y.; Wang L.; Jing Q.; Wang X.; Xi X.; Zhao X.; Wang H. Molecular structure of thermostable and zinc-ion-binding γ-class carbonic anhydrases. BioMetals 2019, 32, 317–28. 10.1007/s10534-019-00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterio V.; Cadoni R.; Esposito D.; Vullo D.; Fiore A. D.; Monti S. M.; Caporale A.; Ruvo M.; Sechi M.; Dumy P.; Supuran C. T.; De Simone G.; Winum J. Y. Benzoxaborole as a new chemotype for carbonic anhydrase inhibition. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52 (80), 11983–11986. 10.1039/C6CC06399C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini A.; Cadoni R.; Del Prete S.; Capasso C.; Dumy P.; Gratteri P.; Supuran C. T.; Winum J. Y. Benzoxaboroles as Efficient Inhibitors of the β-Carbonic Anhydrases from Pathogenic Fungi: Activity and Modeling Study. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8 (11), 1194–1198. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini A.; Cadoni R.; Dumy P.; Supuran C. T.; Winum J. Y. Carbonic anhydrases from Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani chagasi are inhibited by benzoxaboroles. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018, 33 (1), 286–289. 10.1080/14756366.2017.1414808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini A.; Supuran C. T.; Winum J. Y. Benzoxaborole compounds for therapeutic uses: a patent review (2010- 2018). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018, 28 (6), 493–504. 10.1080/13543776.2018.1473379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcher A.; Nocentini A.; Supuran C. T.; Winum J. Y.; van der Lee A.; Vasseur J. J.; Laurencin D.; Smietana M. Bis-benzoxaboroles: Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation as Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (8), 1205–1210. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langella E.; Alterio V.; D’Ambrosio K.; Cadoni R.; Winum J. Y.; Supuran C. T.; Monti S. M.; De Simone G.; Di Fiore A. Exploring benzoxaborole derivatives as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: a structural and computational analysis reveals their conformational variability as a tool to increase enzyme selectivity. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34 (1), 1498–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifah R. G. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C.. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.