Abstract

Purpose:

Our purpose was to assess disease outcomes and late toxicities in pediatric patients with rhabdomyosarcoma treated with conformal photon radiation therapy (RT).

Methods and Materials:

Sixty-eight patients (median age, 6.9 years) were treated with conformal photon RT to the primary site on a prospective clinical trial. Target volumes included a 1-cm expansion encompassing microscopic disease. Prescribed doses were 36 Gy to this target volume and 50.4 Gy to gross residual disease. Chemotherapy consisted of vincristine/dactinomycin (n = 6), vincristine/dactinomycin/cyclophosphamide (n = 37), or vincristine/dactinomycin/cyclophosphamide-based combinations (n = 25). Patients were evaluated with primary-site magnetic resonance imaging, whole-body [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, and chest computed tomography for 5 years after treatment.

Results:

Five-year disease-free survival was 88% for low-risk (n = 8), 76% for intermediate-risk (n = 37), and 36% for high-risk (n = 23) patients (P≤.01 for low risk/intermediate risk vs high risk). The cumulative incidence of local failure (LF) at 5 years for the entire cohort was 10.4%. Tumor size at diagnosis was a significant predictor of LF (P <.01). Patients with head and neck primary tumors (n = 31) had a 35% cumulative incidence of cataracts; the risk correlated with lens dose (P = .0025). Jaw dysfunction was more severe when the pterygoid and masseter muscles received a mean dose of >20 Gy (P = .013). Orbital hypoplasia developed more frequently after a mean bony orbit dose of >30 Gy (P = .041). Late toxicity in patients with genitourinary tumors included microscopic hematuria (9 of 14), bladder-wall thickening (10 of 14), and vaginal stenosis (2 of 5).

Conclusions:

Long-term LF rates were low, and higher rates correlated with larger tumors. Treatment-related toxicities resulting in measurable functional deficits were not infrequent, despite the conformal RT approach. Ó 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Approximately 75% of children with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) require radiation therapy (RT) as part of multi-modality treatment to achieve cure.1 The radiation doses required to cure RMS are relatively modest; however, the young age of the patients means that long-term treatment effects, including alterations in growth and development, occur frequently. Furthermore, RT to the most frequent sites of RMS involvement—the head and neck (H&N), trunk, and extremities—often results in cosmetically evident and medically difficult effects requiring chronic management.2

Patients with H&N RMS experience bone-growth alterations, endocrinopathies, cataracts, hearing loss, and chronic oral cavity changes after therapy.3–7 Patients with trunk or pelvic RMS experience orthopedic complications and gastrointestinal or genitourinary dysfunctions.8–10 Patients with extremity RMS develop growth asymmetry owing to the exposure of long bones to radiation.11 Thus, delivering safe and effective RT is key to curing RMS while maintaining an acceptable long-term toxicity profile. Unfortunately, radiation avoidance is frequently not an option for patients with RMS because of the common primary tumor sites and risk of local recurrence.12 In addition, many studies of long-term effects of RT in patients with RMS have been single-institution retrospective studies using large-field nonconformal RT techniques, thus limiting detailed analyses and their applicability to current conformal treatments.9,11

The application of conformal RT modalities and reduced-volume targeting has yielded clinically meaningful reductions in the volume of normal tissue receiving high radiation doses without increases in local failure (LF).13–15 Based on these observations, we conducted a prospective phase 2 trial delivering conformal photon RT (both 3-dimensional [3D] conformal and intensity modulated) to the primary disease site in children with RMS, using specific limited-margin tumor targeting. The primary objective of this trial, which was the first to use a 1-cm targeting volume for RMS, was to ensure adequate local control with this more conformal and volume-reduced treatment approach. The secondary goal was to define the long-term toxicity profile of this approach, which used a smaller irradiated volume. Here we report long-term local disease control outcomes and site-specific toxicities from this trial. These data will serve as a critical benchmark for long-term toxicities associated with conformal photon RT and as a prospectively defined reference data set as we move forward with increasingly conformal treatment techniques, including proton beam RT, and consider further volume reductions.

Methods and Materials

Patient population

Sixty-eight pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients aged <25 years with RMS requiring radiation to the primary tumor site consented to, enrolled on, and were treated on an institutional review board–approved phase 2 institutional study of 3D conformal RT (3DCRT) or intensity modulated RT (IMRT) from 2003 to 2013.16 Patients were selected for RT based on standardized criteria used in recent Children’s Oncology Group (COG) trials for patients with RMS17 and were staged and grouped using the RMS-specific tumor, node, and metastasis staging system18 and the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group surgical grouping system. All patients with clinical group IIIA disease (biopsy only) at diagnosis received RT, as did any patient with group II disease (marginal resection or lymphatic involvement) or IIIB disease (partial resection) after resection. Only patients with alveolar histology with group I disease (complete resection) received adjuvant RT.

Primary treatment

The specifics of external beam RT (EBRT) and brachytherapy techniques have been reported previously.19 Briefly, target volumes were delineated on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) treatment-planning data sets; MRI data sets (typically obtained in the treatment position) were coregistered to the CT to fully define target volumes. Gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined as postchemotherapy imaging-defined soft-tissue abnormality including areas of normal tissue initially infiltrated by the tumor and initial bone involvement, allowing for volume reduction away from “pushing” borders. In patients whose tumors were resected, the GTV was defined as the surgical tumor bed. Areas at risk for microscopic disease were included in the clinical target volume (CTV) by using a 1-cm anatomically constrained expansion around the GTV, with a volume-reduction incorporating only the GTV in patients treated with definitive RT. Daily set-up uncertainty and patient motion were accounted for with the planning target volume (PTV) with site-specific expansions of 0.5 to 1.0 cm around both the CTV and GTV. Prescribed doses were 36 Gy to the CTV (and its PTV) and 50.4 Gy to the GTV (and its PTV). Delivery to target volumes could be sequential (36 Gy to the initial CTV/PTV, followed by a cone-down to an additional 14.4 Gy to the GTV/PTV over 28 daily fractions of 1.8 Gy) or simultaneous (integrated delivery of 36 Gy to the initial CTV/PTV delivered at 1.5 Gy per fraction and 50.4 Gy to the GTV/PTV at 2.1 Gy over 24 daily fractions). EBRT was delivered using 3DCRT (n = 43) or IMRT (n = 21), and 4 very young patients received interstitial brachytherapy.

Systemic therapy consisted of vincristine/dactinomycin (n = 5); vincristine/dactinomycin/cyclophosphamide (VAC) (n = 36); or other VAC combinations (n = 27) that incorporated irinotecan (n = 11), ifosfamide (n = 11), topotecan (n = 3), or other agents (n = 2). For intermediate-risk (IR) patients, the minimum cyclophosphamide dose (or equivalent)20 prescribed by the treatment plan was 16.8 g/m2; the median dose was 30.8 g/m2.

Follow-up

Follow-up evaluations are detailed in Methods E1 (available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.011). Toxicity was assessed weekly during RT and at each follow-up visit according to the National Institutes of Health Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0,21 and defined as early (within 3 months from the start of RT) or late. Site-specific assessments were conducted for ocular toxicities, jaw dysfunction, and orbital hypoplasia in patients receiving radiation to the H&N region and are detailed in Methods E1 (available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.011).

Statistical analysis

Treatment failure was classified as local if the recurrence was within the PTV. Adjacent or marginal failures were also considered local for the purpose of defining the cumulative incidence (CIN) of LF, which was estimated using the competing-risks method and compared by Gray’s test.22 Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time from study enrollment to any event (including LF, distant failure, secondary malignancy, or death from any cause), whereas disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from enrollment to any disease failure. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate EFS and DFS, and results are presented as the mean ± 1 standard error, with standard errors obtained using the Peto and Pike method,17,23 or with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The log-rank test was used for outcome comparisons. Cox regression was used to analyze the association of survival and prognostic factors, the effect of the total cyclophosphamide dose on LF and DFS, and the association of maximum RT dose and lens and cataract development; results are expressed as hazards ratios. Logistic regression and Pearson correlation were used to assess correlations of late effects with clinical, tumor, and treatment characteristics. Student’s t test was used to evaluate differences in the mean number of grade 1 or higher toxicities per patient by EBRT modality.

Results

Event-free and disease-free survival

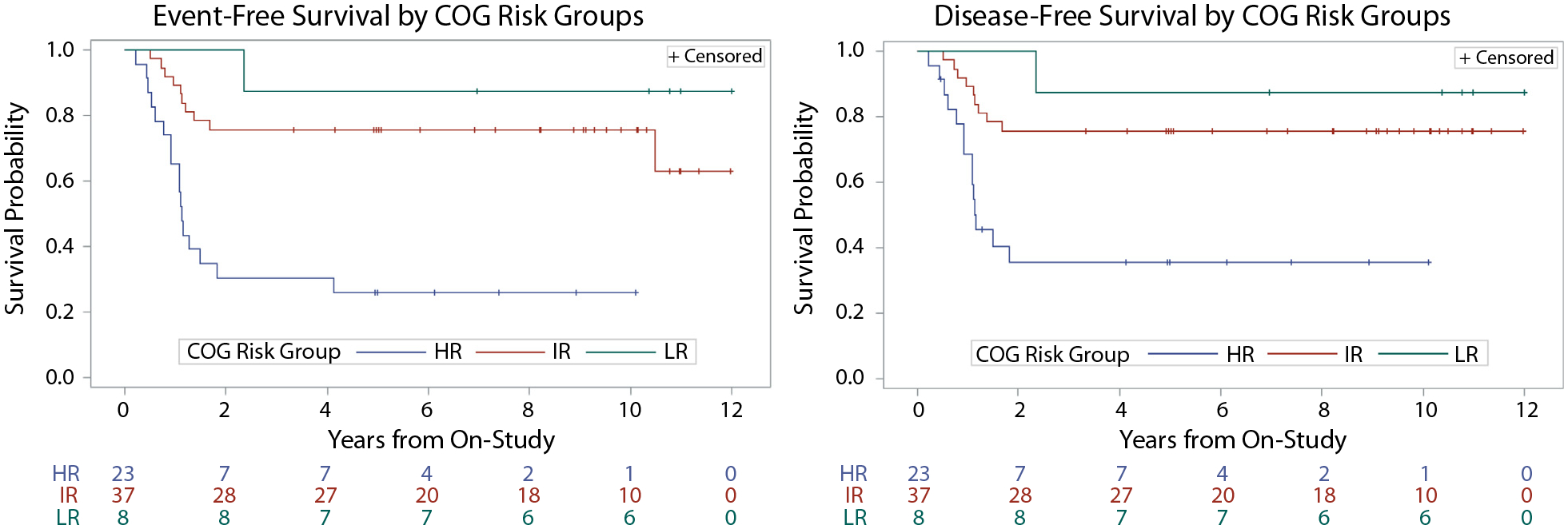

Baseline characteristics of the 68 patients treated on this trial are shown in Table 1. The 5-year EFS and DFS differed significantly across the COG-based risk groups: Both the 5-year EFS and DFS were 88% (±11%) for low-risk (LR) patients and 76% (±8%) for IR patients, and they were 26% (±10%) and 36% (±13%), respectively, for HR patients (P ≤ .01 for both EFS and DFS of LR/IR patients vs HR patients). The EFS and DFS of each risk group are shown in Figure 1. Two patients developed a secondary malignancy within the high-dose RT field at 4.5 (osteosarcoma) and 10.9 years (malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor), and 1 patient died of respiratory failure unrelated to RT.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | N = 68 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 38 (55.9%) |

| Female | 30 (44.1%) |

| Age at on-study (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.6 (6.1) |

| Median (range) | 6.9 (1.2–23.8) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Favorable | 15 (22%) |

| Orbit | 4 (6%) |

| Head and neck (excluding parameningeal) | 8 (12%) |

| Genitourinary (nonbladder/nonprostate) | 3 (4%) |

| Unfavorable | 53 (78%) |

| Bladder/prostate | 9 (13%) |

| Parameningeal | 20 (29%) |

| Extremity | 14 (21%) |

| Other | 10 (15%) |

| Stage | |

| 1 | 10 (14.7%) |

| 2 | 11 (16.2%) |

| 3 | 24 (35.3%) |

| 4 | 23 (33.8%) |

| Clinical group | |

| II | 5 (7.4%) |

| III | 40 (58.8%) |

| IV | 23 (33.8%) |

| COG risk group | |

| HR | 23 (33.8%) |

| IR | 37 (54.4%) |

| LR | 8 (11.8%) |

| Degree of disease present at RT | |

| Clear surgical margins | 1 (1.5%) |

| Microscopic disease | 12 (17.7%) |

| Gross disease | 55 (80.8%) |

| Disease extent | |

| Localized | 45 (66.2%) |

| Metastatic | 23 (33.8 %) |

| Tumor size at diagnosis (cm) | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.1 (4.3) |

| Median (range) | 6.0 (0.9–19.8) |

| With any events | |

| Yes | 28 (41.2%) |

| No | 40 (58.8%) |

| With any failure | |

| Yes | 24 (35.3%) |

| No | 44 (64.7%) |

| With distant failure | |

| Yes | 18 (26.5%) |

| No | 50 (73.5%) |

| With local failure | |

| Yes | 7 (10.3%) |

| No | 61 (89.7%) |

| Survival status | |

| Dead | 24 (35.3%) |

| Alive | 44 (64.7%) |

| Follow-up time, all patients (y) | |

| Mean | 5.9 |

| Median (range) | 5.4 (0.5–12.3) |

Abbreviations: COG = Children’s Oncology Group; HR = hazard ratio; IR = intermediate risk; LR = low risk; RT= radiation therapy; SD = standard deviation.

Fig. 1.

Event-free survival (EFS) (A) and disease-free survival (DFS) (B) stratified by Children’s Oncology Group risk group. Abbreviations: HR = high risk; IR = intermediate risk; LR = low risk.

Local tumor control

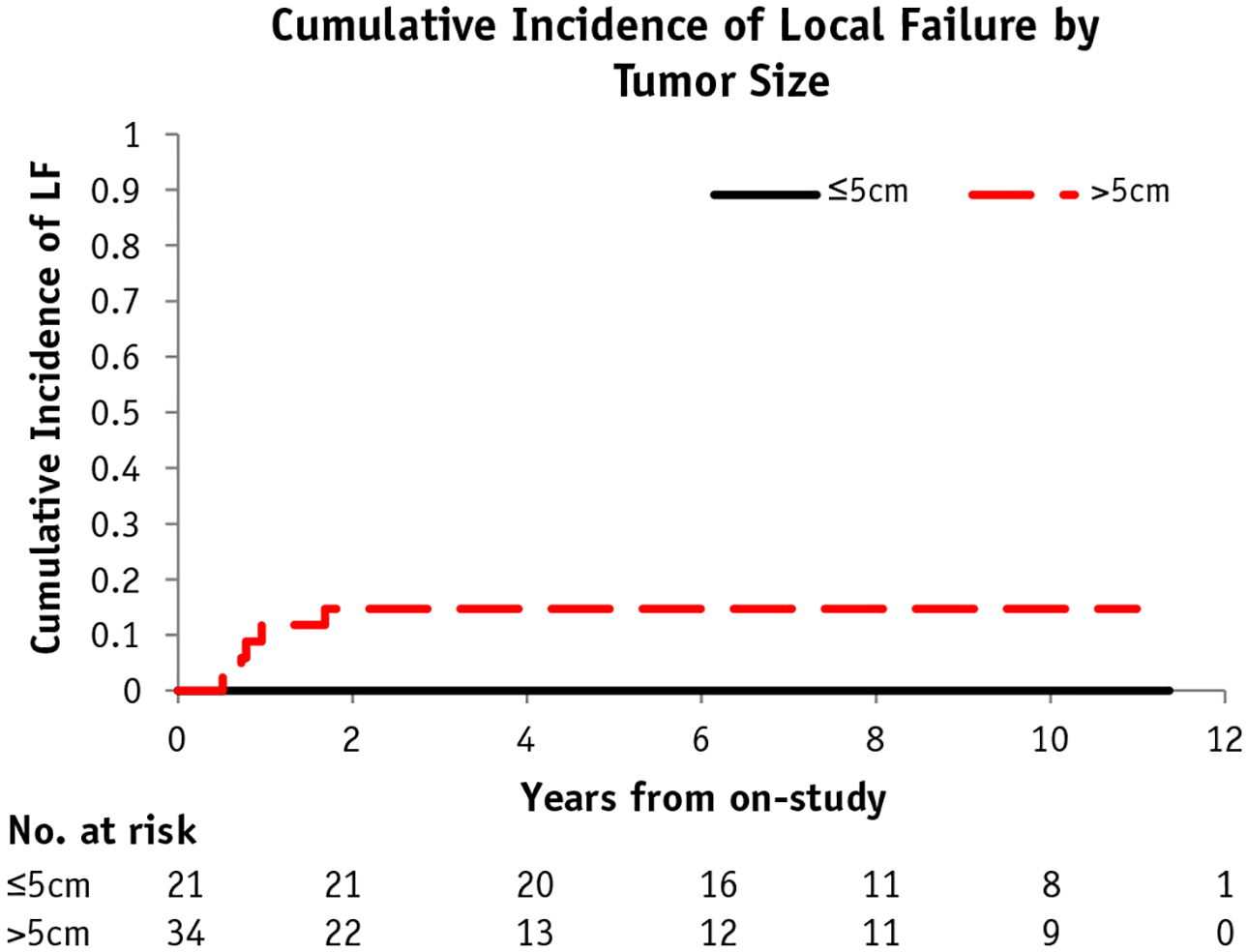

With a median follow-up of 5.4 years (range, 0.5–12.3 years) for all patients enrolled and 9.4 years for those remaining on study, 7 patients had local tumor recurrence. Of these 7 patients, primary tumor sites consisted of H&N (4 patients), trunk (2 patients), and genitourinary (1 patient), with all but 1 primary site considered unfavorable (soft palate). The CIN of LF after 5 years was 10.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.2%−20.9%). For the 55 patients who required definitive RT (with no surgical resection), the CIN of LF was 9.1% (95% CI, 4%−21%), and the median prescription dose was 50.4 Gy. Tumor size at diagnosis, as a continuous variable, was a significant predictor of LF (P <.01). When assessed as a binary variable of ≤5 cm versus >5 cm, the risk of LF was marginally elevated in larger tumors (CINs of LF were 0% and 14.8%, respectively; P = .067) (Fig. 2). Additionally, there was a nonsignificant trend toward increased CIN of LF in patients treated with IMRT compared with those treated with 3DCRT (P = .066). No other analyzed clinical factor, including tumor size (≤8 cm vs >8 cm), T-stage, histology, or tumor site (favorable vs unfavorable), achieved statistical significance for predicting LF in patients receiving definitive RT. Dosimetric analysis using coregistered imaging at the time of local recurrence demonstrated a median dose to the recurrent tumor volume of 100% of the prescribed dose (range, 88%−182%, including a brachytherapy case), whereas the median minimum dose was 97% (range, 72%−99%).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence (CIN) of local failure (LF) with competing risk by tumor size (≤5 cm or >5 cm).

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography analysis

After excluding patients treated with early RT for parameningeal primary tumor sites and those whose RT was significantly delayed (beyond 19 weeks from the start of chemotherapy), the timing of the fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT studies obtained before definitive RT ranged from 5 to 18.7 weeks after chemotherapy initiation, depending on the risk group. Eleven of the 28 patients so analyzed had residual primary-site FDG avidity near the time of RT (median, 13 days; range, 2–32 days from PET/CT to RT). The CIN of LF for patients with residual FDG uptake was 18.2%, versus 0% for patients without residual avidity, showing a trend toward statistical significance (P = .075) within the limitations of small patient subsets.

Effect of cyclophosphamide dose in IR patients

The effect of total cyclophosphamide dose on DFS and local control was analyzed by Cox regression in the IR cohort. Most IR patients (32 of 37) were prescribed a cumulative cyclophosphamide dose of >25 g/m2. Although higher cyclophosphamide doses correlated with decreased risk of LF (hazard ratio, 0.84; CI, 0.74–0.96; P = .009) and DFS (hazard ratio, 0.89; CI, 0.79–0.99; P = .038), this effect was no longer significant after adjusting for tumor size as a continuous variable (P = .711 and P = .810, respectively). When patients were grouped by the cumulative cyclophosphamide dose received, however, a significant difference in the CIN of LF in patients who received ≤25 g/m2 compared with those who received >25 g/m2 cumulative cyclophosphamide was observed (2-year CIN of LF 9.4% vs 60%, P = .008 Gray’s test). Yet, of the 8 patients who received ≤25 g/m2 cumulative cyclophosphamide, 6 had an initial tumor size >5 cm.

Toxicities of focal conformal RT

The maximum toxicity for each patient in each toxicity category is shown in Tables 2 and 3. When evaluated by EBRT modality, there was a trend toward statistically significant increased acute toxicities in patients treated with 3DCRT compared with IMRT (P = .06), and late effects were observed significantly more frequently in patients treated with 3DCRT (P = .003). Late toxicities of grade 3 or higher included 1 episode of hepatic veno-occlusive disease, a femoral fracture considered RT related, and 1 cystitis case. Veno-occlusive disease was observed in a 4.5-year-old female with stage 3, group III embryonal RMS of the retroperitoneum with a 12.5-cm primary tumor treated with an uncomplicated partial resection, VAC/vincristine/topotecan/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy with prolonged blood count recovery, and adjuvant 3DCRT (50.4 Gy). A femoral fracture was observed in an 8-year-old female with an HR stage 4, group IV alveolar RMS of the right thigh with a 6.5-cm primary tumor who received definitive 3DCRT and VAC/ifosfamide/etoposide chemotherapy. Maximum dose to the femur was 49.2 Gy. Cystitis developed in a male infant who received definitive 3DCRT and VAC/vincristine/topotecan/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy for alveolar RMS of the prostate at 1 year 9 months of age for an initial stage 3, group III, IR 9.9-cm tumor. Mean dose to the bladder was 34.6 Gy.

Table 2.

Acute radiation-related toxicities by Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0

| Toxicity grade | Radiation dermatitis | Radiation recall reaction | Arthritis | Muscle weakness | Myositis | Pain due to radiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 7 |

| Grade 2 | 25 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Grade 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Grade 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Table 3.

Late radiation-related toxicities by Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0

| Toxicity grade | Bone | Joint | Skin | Subcutaneoustissue | Kidney | Liver | Lung | SpinalCord | Bladder | Endocrine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 7 | 13 | 35 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 5 |

| Grade 2 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Grade 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Cataracts

Thirty-one patients had primary disease sites in the H&N region. The CIN of cataract formation in this cohort was 35% (±12%). Increasing dose to the lens (calculated as the average dose to the lens from the treatment plan) was a significant predictor of cataract formation after RT (P = .0025), whereas age at diagnosis as a continuous variable (P = .52) and tumor size at diagnosis as a continuous (P = .09) or categorical (≤5 cm vs >5 cm) (P = .17) variable were not. H&N subregion (orbital, parameningeal, or other favorable H&N sites) correlated highly with cataract occurrence (P = .0017). All patients with orbital disease sites developed cataracts, whereas only 15% of patients with parameningeal or other subregion primary sites did so.

Jaw dysfunction

Thirty-one patients with H&N primary tumors were assessed for jaw depression before RT and throughout follow-up. The mean values for jaw depression at baseline, maximum depression during follow-up, and depression at last follow-up were 3.1 cm (95% CI, 3.6–2.7 cm), 4.0 cm (95% CI, 4.4–3.6 cm), and 3.8 cm (95% CI, 4.2–3.3 cm), respectively. Baseline values were significantly lower than values at last follow-up (P = .005). Baseline jaw depression was not influenced by initial tumor size or extent of surgery (biopsy vs resection) before RT. Increasing mean radiation dose to the pterygoid and masseter muscles was a significant predictor of reduced jaw depression after therapy (P = .013), but age at diagnosis was not associated with reduced jaw depression (P = .84). Mean doses of >20 Gy to the pterygoid and masseter muscles were significantly more likely to result in reduced jaw depression (mean, 3.4 cm) than were doses of ≤20 Gy (mean, 4.4 cm). Patients with higher Common Toxicity Criteria scores for mandibular dysfunction also received higher median doses to their pterygoid and masseter muscles (grade 0, 15.1 Gy; grade 1, 32.3 Gy; grade 2, 43.6 Gy; P = .013).

Orbital hypoplasia

Orbital bone growth was assessed in 16 patients who had at least 7 years of follow-up (median, 10.4 years) and facial RT exposure. Compared with the contralateral side, mean RT exposure to the orbital bones of >30 Gy resulted in enopthalmos (P = .041), but no significant association between age at diagnosis and ipsilateral orbital depth (P = .95) was observed. There was no correlation with differences in the measured volumes of the ipsilateral and contralateral orbits and the dose to the orbital bones.

Endocrinopathies

Eight patients with H&N primary tumors developed radiation-related endocrinopathies: 6 patients developed growth hormone deficiency, 1 had central hypothyroidism, and 2 (one of whom also had growth hormone deficiency) developed primary hypothyroidism. The mean doses to the hypothalamus, pituitary, and thyroid for these children were 25.1 Gy, 44.6 Gy, and 20.9 Gy, respectively.

Genitourinary

Of the 14 patients with a pelvic primary disease site, 9 had measurable hematuria during the first year after RT completion and 10 exhibited bladder-wall thickening after RT, based on CT surveillance imaging. No patient required permanent urinary diversion. Neither measurable hematuria nor bladder-wall thickening correlated significantly with mean bladder radiation dose. Long-term persistent grade 1 or 2 urinary symptoms of frequency, urgency, and/or incontinence were documented in 4 of 14 patients (28.6%). Two of 5 female patients (40%) experienced significant (grade 2) vaginal stenosis.

Extremities

Of the 14 patients with extremity primaries, 1 experienced a femoral fracture, with a maximum dose to exposed bone of 49.2 Gy (range, 21–55.8 Gy). Of these 14 patients, 13 had open bone physes adjacent to the at-risk irradiated volume before RT. Of the 26 evaluable open physes, 5 demonstrated closure during available short-tau inversion recovery–based MRI evaluations at follow-up. No correlation between increasing physis dose and physis closure was identified (P=.46). Older age at time of RT correlated with physis closure (P = .037), probably related to normal transition through puberty.

Discussion

This prospective phase 2 trial evaluated long-term tumor control and radiation-related complications in children, adolescents, and young adults with RMS treated with a novel, limited-target-margin approach with 3D image guided conformal photon irradiation. We hypothesized that using microscopic residual dosing of 36 Gy and gross residual disease dosing of 50.4 Gy targeting a reduced CTV margin of 1 cm would reduce the likelihood of late toxicities while maintaining rates of local control compared with historic RMS populations treated with less conformal approaches and larger target margins of 1.5 to 2 cm. Indeed, at a median follow-up of 5.4 years for all patients, the CIN of LF at 5 years was 10.4% (95% CI, 5.2%−20.9%). These rates compare favorably to those reported by COG for the D9803 trial, in which the overall LF rate was 19%.24 Moreover, all 7 local recurrences were within the initial high-dose region. Only initial tumor size predicted a higher risk of local recurrence, with no LFs observed in patients with tumors 5 cm or smaller and a 14.8% CIN of LF in patients with tumors larger than 5 cm. The effect of tumor size on local control was also observed in the D9803 trial, in which patients with larger tumors had an LR rate of 25%, as previously noted by our group.17,25

In this trial, although residual FDG uptake within the primary site before RT was observed more frequently in patients with local recurrence, this was not a significant predictor of LF, a finding supported by the COG ARST0531 and ARST08P1 studies.26 Based on these findings and on the effect of tumor size on LF, we are investigating the effect of dose escalation (59.4 Gy) for children with tumors larger than 5 cm in our current trial.27 The COG has followed a similar approach in its ongoing trial for patients with IR RMS,28 incorporating dose escalation for larger tumors and dose reduction for patients with specific imaging-based complete response incorporating CT/MRI and PET-CT or biopsy data. These trials should provide additional data on patients at higher or lower risk for LF and on the effect of RT dose.

The chemotherapy regimen in our trial largely followed the D9803 IR protocol,17 which prescribed a dose of 2.2 g/m2/cycle of cyclophosphamide. Only 5 patients in our study received lower doses of cyclophosphamide, similar to that used in the most recent COG IR study,29 in which cyclophosphamide was dosed at 1.2 g/m2/cycle. Although we and others reported increased LF with lower cyclophosphamide doses, particularly among patients with parameningeal tumors,30–32 the present study showed no significant effect on LF in multivariate models incorporating tumor size, probably because of the small numbers of patients with low cyclophosphamide exposure. When grouped by receipt of a cumulative cyclophosphamide dose of 25 g/m2 or less, however, these patients did appear to have significantly higher risk of local tumor progression, although it is important to note that most patients who received a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide had large tumors (>5 cm).

A secondary objective of this trial was to define the risk of long-term toxicities by using state-of-the-art limited-margin conformal photon-based RT that minimized exposure of adjuvant normal tissues with the hope of reducing the number and severity of well-documented late effects.3,4,10,33 This was partially realized compared with prior studies using less conformal approaches with larger targeting volumes. Nine of 16 patients (56%) in our trial with orbital-bone RT exposure and mean bony orbit doses of >30 Gy experienced measurable changes in bone structure and shape. A similar proportion of patients (59%) with orbital RMS from IRS III developed orbital hypoplasia.3 Cataract rates were also similar in patients with orbital RMS (100% for our patients and 82% for those on IRS III).3 An analysis from an international workshop on bladder/prostate RMS noted that 31% of patients treated with definitive RT experienced some incontinence and 25% had chronic hematuria,10 whereas 29% of our patients with pelvic tumor sites experienced long-term grade I/II urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency, and/or incontinence) and 29% had measurable hematuria after 4 years. However, the incidence of cataracts in nonorbital H&N cases was 15% in our study, whereas 47% of patients reporting eye problems from IRS II/III developed cataracts.3 Only 19% of our patients with H&N RMS experienced growth hormone deficiency, whereas 48% of patients in IRS II/III were noted to have short stature.3 As has been observed in other studies of conformal RT,13,14 we observed a significant reduction in long-term treatment-related toxicities in patients treated with IMRT compared with 3DCRT. These improvements and similarities in late toxicities suggest that more focal techniques such as conformal therapy can reduce side effects in adjacent nontarget normal tissues when the organ can be partially or completely spared, but late toxicities may still occur when the end organ (eg, bladder or urethra) is part of the tumor target. Many of these toxicities, along with others such as jaw dysfunction, were significantly correlated with RT dose to a specific structure or end organ in our study, which may facilitate the prospective evaluation of site-specific RT planning objectives to further limit long-term toxicities.

Conclusions

With a follow-up of 9.4 years for living children without an event, most patients experienced both early and late grade 1 or 2 toxicities, yet very few experienced higher-grade acute or late toxicities. Although these patients will probably continue to accumulate toxicities as they age, this limited-margin radiotherapeutic approach appears to have been fairly well tolerated. That said, a potentially more useful aspect of this trial is the demonstration that many of the late effects studied and documented can be correlated with increasing RT dose and exposed tissue volume, suggesting that the risk of developing these toxicities can be further lowered by reducing normal tissue exposure with evolving RT modalities, such as intensity modulated proton therapy. Emerging proton therapy data suggest that this assertion may be correct and that disease control outcomes are not compromised, yet long-term follow-up is currently lacking.34 Although eliminating RT for selected patients may be the best way to reduce toxicity, our data suggest that continuing to refine our radiation approach, including an increasingly conformal technique with limited margins in patients who clearly benefit from this local tumor control therapy, can further minimize the risk of late effects without compromising local tumor control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments—

The authors thank Samantha Buhler for clinical trial data management and Keith A. Laycock, PhD, ELS, for scientific editing of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA021765, St. Jude Cancer Center Support Grant), and the Lance Armstrong Foundation to M.J.K.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none.

Radiation Therapy to Treat Musculoskeletal Tumors (RT-SARC) is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00186992.

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.011.

References

- 1.Bishop MW, Krasin M. Pediatric soft-tissue sarcomas Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, editors. Clinical Radiation Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015. p. 1403–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punyko JA, Mertens AC, Gurney JG, et al. Long-term medical effects of childhood and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;44:643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raney RB, Asmar L, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, et al. Late complications of therapy in 213 children with localized, nonorbital soft-tissue sarcoma of the head and neck: A descriptive report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies (IRS)-II and - III. Med Pediatr Oncol 1999;33:362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raney RB, Anderson JR, Kollath J, et al. Late effects of therapy in 94 patients with localized rhabdomyosarcoma of the orbit: Report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS)-III, 1984–1991. Med Pediatr Oncol 2000;34:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoot RA, Hol MLF, Merks JHM, et al. Facial asymmetry in head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017; 64:e26508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clement SC, Schoot RA, Slater O, et al. Endocrine disorders among long-term survivors of childhood head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma. Eur J Cancer 2016;54:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoot RA, Theunissen EA, Slater O, et al. Hearing loss in survivors of childhood head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma: A long-term follow-up study. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyn R, Raney RB Jr., Hays DM, et al. Late effects of therapy in patients with paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1992;10: 614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spunt SL, Sweeney TA, Hudson MM, Billups CA, Krasin MJ, Hester AL. Late effects of pelvic rhabdomyosarcoma and its treatment in female survivors. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7143–7151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raney B, Anderson J, Jenney M, et al. Late effects in 164 patients with rhabdomyosarcoma of the bladder/prostate region: A report from the international workshop. J Urol 2006;176:2190–2194; discussion 2194–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulino AC. Late effects of radiation therapy for pediatric extremity sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;60:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolden SL, Anderson JR, Crist WM, et al. Indications for radiotherapy and chemotherapy after complete resection in rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies I to III. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3468–3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng G, Wang T, Yang KY, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing outcomes and toxicities of intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 2012;104:286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viani GA, Viana BS, Martin JE, Rossi BT, Zuliani G, Stefano EJ. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduces toxicity with similar biochemical control compared with 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer 2016; 122:2004–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merchant TE, Kun LE, Krasin MJ, et al. Multi-institution prospective trial of reduced-dose craniospinal irradiation (23.4 Gy) followed by conformal posterior fossa (36 Gy) and primary site irradiation (55.8 Gy) and dose-intensive chemotherapy for average-risk medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;70:782–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krasin M Radiation Therapy to Treat Musculoskeletal Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00186992; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: Children’s Oncology Group Study D9803. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5182–5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence WJ, Anderson JR, Gehan EA, Maurer H. Pretreatment TNM staging of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: A report of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. Cancer 1997;80:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hua C, Gray JM, Merchant TE, Kun LE, Krasin MJ. Treatment planning and delivery of external beam radiotherapy for pediatric sarcoma: the St. Jude experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70:1598–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cancer Institute. Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events, 2.0 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program; 1999. Available at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. Accessed August 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Statistics 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. Analysis and examples. Br J Cancer 1977;35:1–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krasin M, Hua C, Spunt S, et al. FDG-PET/CT prior or subsequent to radiation is a poor predictor of local outcome in patients with group III rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:S116. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolden SL, Lyden ER, Arndt CA, et al. Local control for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: Results from D9803 according to histology, group, site, and size: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;93: 1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison DJ, Parisi MT, Shulkin BL, et al. 18F 2Fluoro-2deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) response to predict event-free survival (EFS) in intermediate risk (IR) or high risk (HR) rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS): A report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). J Clin Oncol 2016;34(15 suppl):10549. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krasin M Risk-Adapted Focal Proton Beam Radiation and/or Surgery in Patients With Low, Intermediate and High Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma Receiving Standard or Intensified Chemotherapy. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02567435; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A Combination chemotherapy with or without temsirolimus in treating patients with intermediate risk rhabdomyosarcoma. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02567435. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawkins DS, Chi YY, Anderson JR, et al. Addition of vincristine and irinotecan to vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide does not improve outcome for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2018;36: 2770–2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas JT Jr., Pappo AS, Wu J, Indelicato DJ, Krasin MJ. Excessive treatment failures in patients with parameningeal rhabdomyosarcoma with reduced-dose cyclophosphamide and delayed radiotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2018;40:387–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walterhouse DO, Pappo AS, Meza JL, et al. Reduction of cyclophosphamide dose for patients with subset 2 low-risk rhabdomyosarcoma is associated with an increased risk of recurrence: A report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2017;123:2368–2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casey DL, Wexler LH, Wolden SL. Worse outcomes for head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma secondary to reduced-dose cyclophosphamide. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;103:1151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulino AC, Simon JH, Zhen W, Wen BC. Long-term effects in children treated with radiotherapy for head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;48:1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladra MM, Szymonifka JD, Mahajan A, et al. Preliminary results of a phase II trial of proton radiotherapy for pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3762–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.