Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the diagnostic role of new metrics, defined as individualized-thresholding of Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) parameters, in association with clinical factors (such as age, mammographic density, lesion size and depth) and the BI-RADS features in differentiating benign from malignant breast lesions.

Methods

Of 644 consecutive patients (median age, 55 years), prospectively referred for evaluation, 659 ultrasound detected breast lesions underwent SWE measurements. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the probability of malignancy. The area under the curve (AUC), optimal cutoff value, and the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were determined.

Results

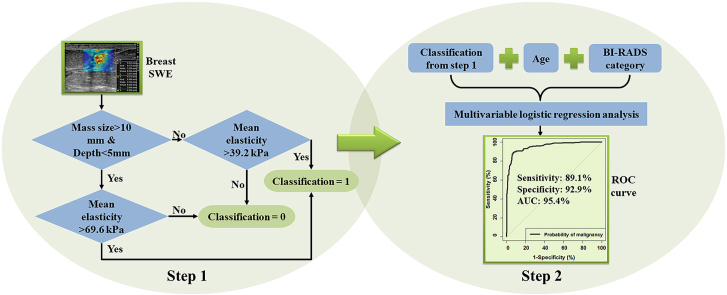

265 of 659 (40.2%) masses were malignant. Using two Emean cutoffs, 69.6 kPa for large superficial lesions (size >10 mm, depth ≤5 mm) and 39.2 kPa for the rest, the overall specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV were 92.6%, 86.8%, 88.8% and 91.3%, respectively. Combining multiple factors, including Emean with two cutoffs, age and BI-RADS, the new ROC curve based on the malignancy probability calculation showed the highest AUC (0.954, 95% CI: 0.938–0.969). Using the optimal probability threshold of 0.514, the corresponding specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV were 92.9%, 89.1%, 89.4% and 92.7%, respectively.

Conclusions

The false-positive rate can be significantly reduced when applying two Emean cutoffs based on lesion size and depth. Moreover, the combination of age, Emean with two cutoffs and BI-RADS can further reduce the false negatives and false positives. Overall, this multifactorial analysis improves the specificity of ultrasound while maintaining a high sensitivity.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast masses, Elastography, Shear wave elastography, Ultrasound

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Larger mass size and lower mass depth increase false positives in breast SWE.

-

•

Smaller mass size and increased mass depth increase false negatives in breast SWE.

-

•

Individualized elasticity cutoffs based on lesion size and depth improves the specificity.

-

•

Multifactorial analysis including age, individualized cutoffs, BIRADS improves sensitivity/specificity.

-

•

Mammographic breast density does not affect the SWE measurements of breast masses.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under curve

- ALN

Axillary lymph node

- BI-RADS

Breast imaging reporting and data system

- CI

Confidence intervals

- FNA

Fine needle aspiration

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IRB

Institutional review board

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROI

Region of interest

- SD

Standard deviation

- SWE

Shear wave elastography

- SWV

Shear wave velocity

- US

Ultrasound

- 2D

2-dimensional

1. Introduction

The high rate of unnecessary follow-ups and biopsies illustrate the importance of specificity for breast cancer detection [1]. Breast ultrasound (US) is the most common and effective imaging tool for the evaluation of palpable or mammographically detected breast lesions and increases the sensitivity of mammography [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. US, however, carries low specificity and leads to unwarranted benign biopsies in up to 76% of cases [6,7]. The breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) with US descriptors are used to assess and categorize breast lesions [8,9]. BI-RADS category 4 has a likelihood of malignancy ranging from 2% to 95%, and the subcategory BI-RADS 4a demonstrates less than 10% malignancy. Therefore, improved characterization of breast masses is needed to correctly downgrade BI-RADS 4a lesions to BI-RADS 3, and to reduce unnecessary benign breast biopsies [10].

Elastography has rapidly developed in the last two decades to help discriminate benign from malignant lesions based on tissue stiffness. Most malignant lesions exhibit higher stiffness than benign lesions [11]. Shear wave elastography (SWE) is a qualitative and quantitative method for measuring tissue stiffness. The high reproducibility and efficacy of SWE for differentiation of breast masses [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]] as well as the detection of metastatic axillary lymph nodes (ALN) [21] have been reported.

Challenges still remain as clinical factors may affect the lesion stiffness [22,23], resulting in a false-positive or false-negative diagnosis. It has been shown that mass depth affects shear wave velocity (SWV) measurements and the SWV decreases with greater lesion depth [24,25]. Moreover, SWV is underestimated in small lesions (especially for lesions <10 mm), leading to false negatives [22,23]. Additionally, age is a well-known risk factor for malignancy [26]. Mammography has a lower sensitivity in detecting cancers in women with mammographically dense breasts [27]. Overall, addition of SWE measurement of a breast mass to the standard BI-RADS features can improve accuracy and specificity of the final assessments [28].

This study aims to investigate the effects of different clinical factors on SWE measurements. Based on the statistical analysis, a new metric, including individualized-thresholding SWE parameters using two cutoffs of Emean based on lesion size and depth, is proposed for breast lesion characterization. Finally, this study evaluates the diagnostic role of individualized-thresholding SWE discriminating parameters in association with BI-RADS, age, breast density, lesion size and depth in differentiating benign from malignant breast lesions, as well as identifying the potential factors related to false-negative and false-positive diagnoses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

This prospective study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB-Application # 12–003329) and was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. The cohort of our study included patients with breast concerns and were scheduled for breast biopsies. Concerns included palpable breast lumps found by physicians on routine clinical examination or by the patient themselves, and suspicious lesions identified in screening mammography. Most of the included lesions were categorized as BI-RADS 4 or 5 based on the imaging studies. These patients were recruited by our study coordinator and enrolled in this study before the biopsy. During the recruitment, patients with breast implants or mastectomies were excluded.

From April 2014 through August 2020, a total of 677 female patients (age range 18–89 years, mean age 54.4 ± 15.3 years, median age, 55 years) were recruited for the SWE study. Among them, 21 patients had previous ipsilateral breast cancer and underwent a lumpectomy. A signed written IRB-approved informed consent with permission for publication was obtained from each volunteer. The SWE study was conducted prior to the breast biopsy. After excluding 33 patients due to SWE cancelation, 644 patients with a total of 659 breast lesions were studied. Of the 659 lesions, 2 lesions initially scheduled for biopsy were diagnosed benign with additional imaging without undergoing biopsy. Of the remaining 657 lesions, 651 underwent US-guided core needle biopsy and 6 underwent fine needle aspiration (FNA). Therefore, pathological results served as the reference gold standard.

2.2. US imaging and SWE

The ultrasound examinations were performed by one of our two highly experienced sonographers, (D. D., K. K. M) with more than 30 years of experience in breast US. Both conventional B-mode and SWE data were acquired using a GE LOGIQ E9 (LE9) clinical scanner equipped with SWE capability and a 9L-D linear array probe (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) with a frequency range between 2 and 8 MHz. B-mode imaging was first used to find the lesion position. The machine was then switched to shear wave mode. The SWE measurement was acquired within a rectangle-shaped field of view (FOV). Normal breast tissue adjacent to the lesion was also included in the FOV. To reduce motion artifacts, the patient was instructed to suspend respiration during the SWE acquisition for approximately 3 s. Pre-compression was also minimized as it would substantially change the SWE results [29].

At least four images in the same orientation were obtained from each lesion. A member of the investigative team chose the most consistent image with the least artifact to draw the regions of interest (ROIs). For each lesion, three non-overlapping ROIs, 3 mm in diameter, were selected inside and in the tissue surrounding the lesion (peritumoral) on the B-mode US. The dual-panel measurement tool on the US scanner allowed the ROIs to appear at the corresponding SWV map at the same time. The number of ROIs were reduced for lesions less than 9 mm in size. The mean SWV, standard deviation, minimum SWV and maximum SWV for each ROI were calculated automatically by the LE9 system. For cases with more than one ROI, the averaged values were calculated for the analysis.

2.3. Clinical-pathologic parameters

Mammographic density was reported by the radiologist according to the clinical mammography images. Our institution does not perform routine whole-breast screening US. Therefore, we did not include a descriptor of background breast echotexture highlighted in BI-RADS Lexicon 5th Edition [30]. The presence of calcifications was read from the breast mammographic examination. Lesion depth (d) in this study was defined as the vertical distance from the skin surface to the top of the lesion shown on the clinical B-mode images. Lesion size (s) was recorded as the largest dimension shown in clinical B-mode ultrasound images. ALN status and histological type were obtained from biopsies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with RStudio (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA). The measured SWV was first converted to elasticity in kilopascals [31] for statistical analysis. The elasticity values were correlated to the results of the pathology. Kruskal-Wallis test and Wilcoxon test were used in statistical analysis. For both tests, p values of 0.05 or less were considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect of multiple factors on the diagnosis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) and determine the cutoff values, as well as the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. Specifically, the optimal cutoff is defined as the point closest to the point (0, 1) on the ROC curve [32].

3. Results

3.1. Participants

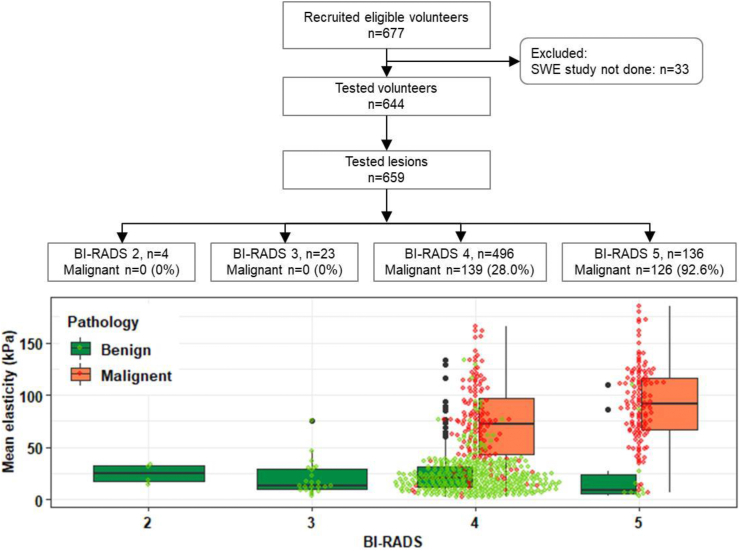

Of 659 lesions, 265 (40.2%) were malignant and 394 (59.8%) were benign. Information about the participants is summarized in Fig. 1. Among the 659 lesions, 4 were considered as BI-RADS category 2, 23 as BI-RADS category 3, 496 as BI-RADS category 4 and 136 as BI-RADS category 5. Most of the lesions included in this study were BI-RADS category 4 and above to keep the pathology as a reference gold standard. The malignancy rates in BI-RADS categories 4 and 5 were 28.0% and 92.6%, respectively. The boxplot in Fig. 1 shows the distribution of mean elasticity (Emean) with standard deviation (SD) for benign and malignant lesions in each BI-RADS category.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants and rates of malignancy with pathology as the reference standard. The bottom boxplot shows the mean elasticity with standard deviation for benign and malignant lesions in each BI-RADS group. Black dots represent the extreme values. In each BI-RADS group, the green dot represents the mean elasticity of three ROIs in each benign lesion and the red dot represents the mean elasticity of three ROIs in each malignant lesion.

3.2. Effects of mammographic density and age on SWE measurements

Table 1 displays Emean±SD of benign and malignant lesions among different mammographic density groups, including: a (fatty breast), b (scattered fibroglandular), c (heterogeneously dense), and d (extremely dense). The p value evaluated with Emean between different density groups was 0.260 for benign lesions and was 0.052 for malignant lesions. Significant differences for Emean were found between the benign and malignant lesions among the different density groups (p < 0.005). Lesions were also divided into three groups according to the patient age, and the corresponding Emean±SD for the benign and malignant lesions as shown in Table 1. The p value among different age groups was 0.318 for benign lesions and was 0.163 for malignant lesions. A significant difference in Emean was found between benign and malignant lesions in all age groups (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found for Emax, Emin and Esd among different age groups nor different density groups for both the benign and malignant lesions (results not shown).

Table 1.

Summary of the averaged Emean and patient number in each clinical factor group.

| Benign | p value | Malignant | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammographic density group | 0.260 | 0.052 | ||

| a | 27.1 + 18.2 (21) | 70.8 + 40.5 (18) | ||

| b | 23.4 + 21.6 (112) | 83.8 + 35.6 (107) | ||

| c | 23.6 + 17.9 (187) | 78.8 + 39.1 (123) | ||

| d | 27.6 + 22.4 (47) | 102.8 + 41.1 (17) | ||

| Age group (years) | 0.318 | 0.163 | ||

| 18-40 | 26.7 + 22.5 (94) | 96.5 + 44.5 (11) | ||

| 40-60 | 21.9 + 15.3 (191) | 79.4 + 36.6 (98) | ||

| 60-89 | 25.4 + 22.2 (109) | 82.3 + 38.9 (156) | ||

| Depth and size group | <0.001∗ | <0.001∗ | ||

| s ≤ 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm | 26.5 + 28.4 (33) | 60.0 + 39.9 (9) | ||

| s > 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm | 34.4 + 25.8 (73) | 109.6 + 28.5 (38) | ||

| s ≤ 10 mm and d > 5 mm | 19.1 + 13.2 (128) | 61.7 + 37.3 (78) | ||

| s > 10 mm and d > 5 mm | 22.6 + 15.8 (160) | 86.9 + 34.8 (140) |

Data are mean ± standard deviation in kPa. The numbers in parentheses are the breast lesion numbers.

∗p < 0.05, difference is statistically significant.

3.3. Effects of lesion depth and size on SWE measurement

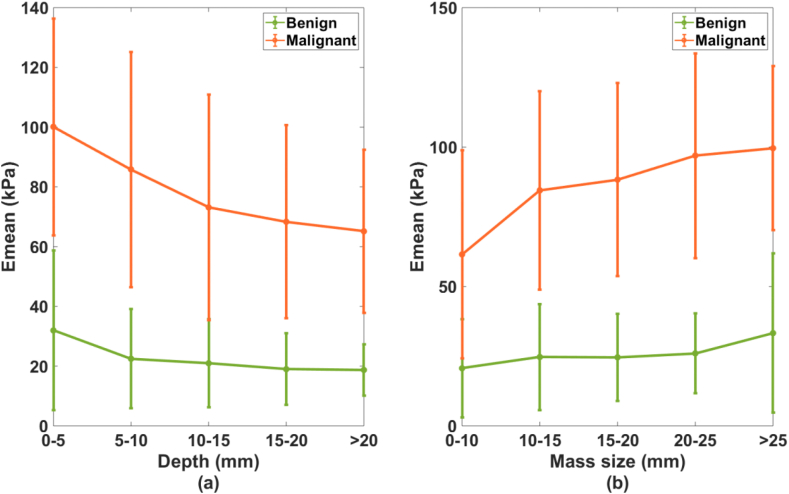

To learn the relationship between d (range, 0.5–30 mm; mean, 10.8 ± 5.9 mm) and SWE measurements, suspicious lesions were divided into five groups according to their depths. The five groups and their corresponding averaged Emean are shown in Fig. 2(a). A significant difference (p = 0.011) was found for the averaged Emean among the five depth groups. No significant difference was found for the averaged Emean among the lesion groups with d > 5 mm (p = 0.340), though the result indicated that the averaged Emean decreased as lesion depth increased.

Fig. 2.

Averaged mean elasticity with standard deviation for the benign and malignant lesions at different (a) depth groups and (b) size groups.

To investigate the relationship between SWE parameters and lesion size (range, 4–85 mm; mean, 15.3 ± 9.5 mm), we divided lesions into 5 different size groups (Fig. 2(b)). Lesions in groups with s > 10 mm were significantly stiffer than lesions with s ≤ 10 mm (Emean, p < 0.001). No significant difference was found for the averaged Emean among the groups with s > 10 mm (p = 0.060), though the results showed that the averaged Emean increased with increasing mass size.

According to these results, the lesions were finally grouped into two depth and size groups for further analysis. The depth groups were superficial lesions with d ≤ 5 mm and deep lesions with d > 5 mm. The size groups were small lesions with s ≤ 10 mm and large lesions with s > 10 mm.

Though the analysis above was based on Emean, similar results were observed for the other three SWE parameters. The averaged Emax and Emin in each group of benign and malignant lesions decreased with increasing depth and decreasing size. Also, the averaged Esd increased with increasing size for both the benign and malignant lesions. In other words, larger lesions showed stronger stiffness heterogeneity.

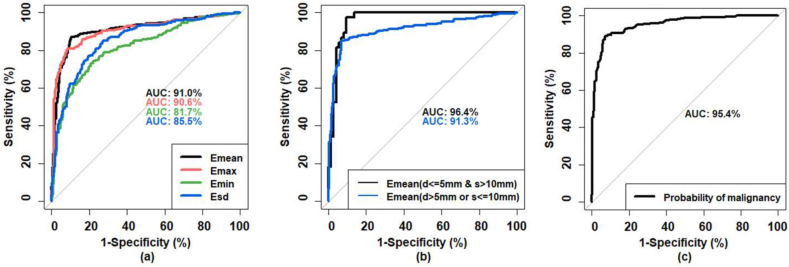

3.4. ROC curve analysis

ROC curves based on the four SWE parameters Emean, Emax, Emin, and Esd are shown in Fig. 3(a). The corresponding AUCs were 0.910 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.885–0.936), 0.906 (95% CI: 0.880–0.932), 0.817 (95% CI: 0.783–0.851), and 0.855 (95% CI: 0.825–0.885), respectively. AUCs for Emean and Emax were significantly higher than that generated with Emin or Esd (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference (p = 0.495) between the AUCs generated with Emean and Emax, and no significant difference (p = 0.056) between the AUCs generated with Emin and Esd; the AUC given by Emean was the highest among the four parameters. Therefore, the analysis in this study focused on the SWE parameter Emean. The optimal cutoff for Emean was 39.2 kPa, resulting in a sensitivity of 87.2%, specificity of 89.8%, PPV of 85.2% and NPV of 91.2%. When the same cutoff Emean = 39.2 kPa was used for all lesions together, the false positive rate was 0.226 and 0.056 for the superficial lesion group (d ≤ 5 mm) and deep lesion group (d > 5 mm), respectively, and was 0.062 and 0.129 for the small lesion group (s ≤ 10 mm) and large lesion group (s > 10 mm), respectively.

Fig. 3.

(a) Comparison for the ROC curves generated based on Emean,Emax, Emin and Esd. (b) ROC curves generated based on Emean for large superficial lesions (s > 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm) and the rest of the lesions (s ≤ 10 mm or d > 5 mm). (c) ROC curve based on the probability of malignancy predicted based on the combination of multiple factors including BI-RADS feature, Emean with two cutoffs based on lesion size and depth, and age.

To further improve the malignancy prediction, a combination of multiple factors was proposed. Following these results above, there are four combinations according to the two depth groups and two size groups: small superficial lesions (s ≤ 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm, N = 42), large superficial lesions (s > 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm, N = 111), deep small lesions (s ≤ 10 mm and d > 5 mm, N = 206), and deep large lesions (s > 10 mm and d > 5 mm, N = 300). The corresponding optimal cutoffs of Emean for the four combinations from the ROC analysis were 28.1 kPa, 69.6 kPa, 35.6 kPa and 39.0 kPa, respectively. The three groups with similar cutoffs were combined together. Thus, based on size and depth, all 659 lesions were classified into two groups: 1) large superficial lesions (s > 10 mm and d ≤ 5 mm, N = 111) and 2) the rest of the lesions (s ≤ 10 mm or d > 5 mm, N = 548). Large superficial lesions were significantly stiffer than other lesions (Emean, p < 0.001). The two corresponding ROC curves were shown in Fig. 3(b). The optimal cut-point of Emean was 69.6 kPa for the first group (large superficial) and was 39.2 kPa for the second group. The lesions were then classified based on the two elasticity cutoffs as benign or malignant accordingly. The multivariable logistic regression analysis was further performed based on the elasticity classification, age and BI-RADS feature. Statistical significance was observed for all coefficients. The probability of being malignant was calculated with [33]:

| Probability = logit−1(-12.896 + 0.054∗A+2.446∗B+3.931∗C), | (1) |

where A is patient age; B is BI-RADS score; C is the score of the elasticity classification based on the two cutoffs of the Emean, with 0 for benign elasticity classification and 1 for malignant elasticity classification; and logit−1 is the logistic function defined as logit−1(α) = 1/(1+exp(-α)). As shown in Fig. 3(c), the AUC given by the “Probability” is 0.954 (95% CI: 0.938–0.969). The optimal cutoff for the “Probability” was 0.514, indicating a specificity of 92.9%, sensitivity of 89.1%, PPV of 89.4% and NPV of 92.7%. The ROC curves for different parameters were summarized and compared in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the ROC curves generated with Emean for all lesions together, Emean for lesions with size >10 mm and depth ≤5 mm, Emean for lesions with size ≤10 mm or depth >5 mm, and probability of malignancy predicted based on the combination of age, Emean with two cutoffs, and BI-RADS feature.

| Emean for all lesions together | Emean for lesions with size >10 mm and depth ≤ 5 mm | Emean for lesions with size ≤10 mm or depth >5 mm | Combination of age, Emean with two cutoffs, and BI-RADS feature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal cutoff | 39.2 kPa | 69.6 kPa | 39.2 kPa | 0.514 |

| Sensitivity | 87.2% | 97.4% | 85.0% | 89.1% |

| Specificity | 89.8% | 90.4% | 93.1% | 92.9% |

| PPV | 85.2% | 84.1% | 89.8% | 89.4% |

| NPV | 91.2% | 98.5% | 90.0% | 92.7% |

| AUC | 0.910 (0.885–0.936) | 0.964 (0.932–0.997) | 0.913 (0.885–0.940) | 0.954 (0.938–0.969) |

Numbers in parentheses were 95% confidence interval.

3.5. Relationship between Emean and histology types

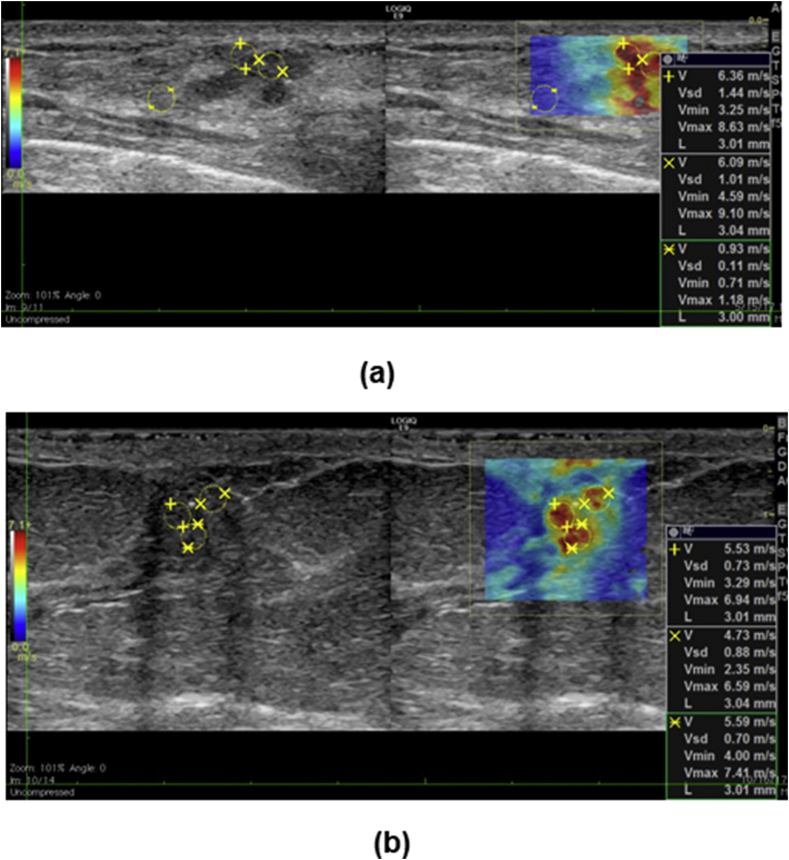

Diversified histological subtypes in 394 benign lesions and 265 malignant lesions were summarized in Table 3. The averaged Emean was 24.0 ± 19.3 kPa for benign lesions and was 81.8 ± 38.3 kPa for malignant lesions. No significant difference was found for Emean among different benign subtypes (p = 0.448) or malignant subtypes (p = 0.535). Fat necrosis exhibited the highest Emean (42.2 ± 36.4 kPa). Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) exhibited the lowest Emean (53.4 ± 41.6 kPa). Fig. 4 shows two examples of false positives that occurred in this study. Fig. 4(a) shows apparent high stiffness measured in a superficial fibroadenoma. Fig. 4(b) shows apparent high stiffness in a benign papilloma including calcifications inside.

Table 3.

Summary of the histopathologic results for 659 breast lesions.

| Histopathologic result | N | Emean±SD (kPa) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0.448 | ||

| Fibroadenoma | 147 | 24.0 ± 15.7 | |

| Breast benign changes with stromal fibrosis | 95 | 21.9 ± 19.5 | |

| Fibrocystic changes | 39 | 22.5 ± 20.1 | |

| Papilloma | 31 | 24.3 ± 19.5 | |

| Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia | 25 | 17.7 ± 13.0 | |

| Fat necrosis with scar/calcifications/fibrosis | 24 | 42.2 ± 36.4 | |

| Atypical/high riska | 16 | 24.5 ± 13.6 | |

| Adenoma | 7 | 21.8 ± 9.3 | |

| Duct ectasia | 6 | 25.0 ± 13.4 | |

| Othersb | 4 | 18.4 ± 5.2 | |

| Total | 394 | 24.0 ± 19.3 | |

| Malignant | 0.535 | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 167 | 80.7 ± 37.3 | |

| Invasive mammary carcinoma with mixed ductal and lobular feature | 45 | 90.7 ± 36.4 | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 32 | 93.3 ± 37.0 | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 16 | 53.4 ± 41.6 | |

| Non-mammary breast malignancies | 5 | 57.2 ± 36.1 | |

| Total | 265 | 81.8 ± 38.3 |

Including 8 atypical ductal hyperplasia, 3 atypical lobular hyperplasia, 2 atypical papillary lesions, 1 fibromyxoid spindle cell lesion with atypia, 1 radial scar with focal residual atypical hyperplasia associated with flat epithelial atypia, 1 atypical/high risk, and fibrocystic changes.

Including 1 mastitis, 1 radial scar with florid usual type ductal hyperplasia, 1 diabetic mastopathy, and 1 apocrine metaplasia.

Fig. 4.

Examples of false positive SWE measurements. (a) Transverse B-mode (left) and SWE (right) images of a superficial fibroadenoma. (b) Longitudinal B-mode (left) and SWE (right) images of a papilloma with calcifications present.

4. Discussion

Mammography and conventional ultrasound together play an essential role in deciding if a breast biopsy is needed. Adding SWE information to mammography and conventional ultrasound improves the overall clinical decision making. In this study, the effects of clinical factors, such as BI-RADS, age, mammographic breast density, mass depth and size on discriminating parameters of SWE Emean, Emax, Emin (indicators of stiffness), and Esd (indicator of the distribution of the stiffness) were evaluated. Our study showed that neither age, nor mammographic density, affects SWE measurements in benign or malignant lesions. Moreover, significant differences between benign and malignant lesions can be observed within each density/age group. Thus, SWE measurement is a suitable diagnostic tool for all patients at any age and with different breast density types.

In this study, we found that the averaged Emean decreased with increasing lesion depth, and the superficial lesion group exhibited the highest Emean. Similarly, previous phantom studies have shown that mass depth will affect SWV measurement [24,25] and SWE is gradually underestimated with increasing depth. This could be explained by the fact that the acoustic push beam attenuates significantly in more deeply located lesions and thus the induced shear wave becomes weak [24,34]. Although lesion depth affects the SWE measurement, no significant difference was found for the Emean among lesions within different depth groups with d > 5 mm. Therefore, SWE could still provide reliable results for deep lesions.

The significant effect of lesion size and depth on SWE measurements in this study prompted selection of two cutoffs: Emean = 69.6 kPa for the large superficial lesions and Emean = 39.2 kPa for the rest. When compared with the results using one cutoff Emean = 39.2 kPa, false positives decreased by about 27.5%, while the false negatives increased by about 2.9%. Combining all factors, age, Emean with two cutoffs, and BI-RADS, false negatives and false positives can be further reduced by about 17.7% and 3.5%, respectively. Thus, the proposed malignancy probability formula shows the highest AUC and gives the most accurate diagnosis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of applying two cutoffs to the Emean based on the lesion size and depth for breast lesion characterization. Moreover, it is the first time that the combination of Emean with two cutoffs, age, and BI-RADS feature was used for improving the breast cancer diagnosis accuracy.

There are possible reasons for the false positive diagnosis with SWE. One is that some benign lesions are stiff. In this study, fat necrosis shows the highest averaged stiffness among all benign types and produces the highest false-positive rate, which is not consistent with the finding of others [19,35,36]. This discrepancy could be because most of the fat necrosis cases in this study also had scar/calcification or fibrosis, which make the lesion stiff. Pre-compression also increases tissue stiffness [10,37] and therefore produces false positives [10]. Even with a highly experienced sonographer, pre-compression can be applied, especially for superficial lesions. This could explain the higher cutoff of Emean for large superficial lesions. The presence of calcifications and scar also leads to apparent stiffness, and therefore, can cause false positives [18,38,39].

The Emean for malignant lesions was much larger than that of benign lesions. However, a false-negative diagnosis may occur for malignant lesions. In this study, DCIS and non-mammary breast malignancies had higher false-negative rates, and they exhibited a lower Emean when compared with invasive carcinomas. This finding is consistent with what was shown in a prior study [19]. False negatives also happen in smaller lesions, especially when s ≤ 10 mm, meaning that the stiffness could be underestimated [22,23].

There are some limitations in our study. Selection bias might exist. Considering breast pathology as the reference standard, most lesions were BI-RADS categories 4 and above, with limited high-risk patients in BI-RADS categories 2 and 3. Such selection does not represent a general screening population, but a population selected for biopsy, which may result in bias. As a consequence, the comparison of 2D-SWE and conventional US cannot be truly evaluated. Secondly, selection of the ROI was subjective and misplacement of the ROI could lead to different results. Thirdly, only a single view plane has been utilized in this study. It has been shown in previous studies that anisotropy correlates with some prognostic factors in breast cancer [40,41]. Therefore, further prospective comparison studies with larger recruitments are necessary to compare the mean elasticity along the two orthogonal orientations of the shear waves.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that breast mammographic density and patient age has no effect on the stiffness measurements. The false-positive rate can be significantly reduced when applying two different cutoffs to Emean based on lesion size and depth. Moreover, the combination of age,. Emean with two cutoffs and BI-RADS feature can further reduce the false negatives and false positives. Overall, this multifactorial analysis improves the specificity of ultrasound while maintaining a high sensitivity. Among the 659 breast lesions included in this study, there were 28 false positives and 29 false negatives. In terms of the clinical practice, a short-term recall of all benign diagnoses based on the multifactorial analysis would be helpful to catch the missed cancers.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [grant number R01CA148994] and the National Science Foundation [grant number CNS-1837572]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The NIH did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The research involved human participants. The study received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB-Application # 12–003329) and was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Signed IRB approved informed consent with permission for publication was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article and the authors affirm that they have no financial interest related to the technology referenced in this paper. AA received grant R01CA148994 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); AA and MF also received grant from National Science Foundation to support in part the project, however, the NIH and NSF did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Cindy Andrist for her valuable help in patient recruitment, Ms. Adriana Gregory, Dr. Max Denis, PhD, Dr. Mahdi Bayat, PhD, Dr. Viksit Kumar, PhD, Dr. Bae-Hyung Kim, PhD, Mr. Jeremy Webb, and Dr. Saba Adabi, PhD for their assistance in SWE data acquisition at different periods during the patient studies. Also we thank Mr. Duane Meixner, R.V.T., R.D.M.S., and Ms. Kate Knoll, R.V.T., R.D.M.S for scanning patients. The authors are grateful to Dr. Sonia Watson, PhD for her editorial help.

References

- 1.Berg W.A., Berg J.M., Sickles E.A., Burnside E.S., Zuley M.L., Rosenberg R.D. Cancer yield and patterns of follow-up for BI-RADS category 3 after screening mammography recall in the National Mammography Database. Radiology. 2020:192641. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolb T.M., Lichy J., Newhouse J.H. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165–175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg W.A., Blume J.D., Cormack J.B., Mendelson E.B., Lehrer D., Böhm-Vélez M. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. Jama. 2008;299:2151–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nothacker M., Duda V., Hahn M., Warm M., Degenhardt F., Madjar H. Early detection of breast cancer: benefits and risks of supplemental breast ultrasound in asymptomatic women with mammographically dense breast tissue. A systematic review. BMC Canc. 2009;9:335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehman C.D., Lee C.I., Loving V.A., Portillo M.S., Peacock S., DeMartini W.B. Accuracy and value of breast ultrasound for primary imaging evaluation of symptomatic women 30-39 years of age. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:1169–1177. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poplack S.P., Carney P.A., Weiss J.E., Titus-Ernstoff L., Goodrich M.E., Tosteson A.N. Screening mammography: costs and use of screening-related services. Radiology. 2005;234:79–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakashima K., Shiina T., Sakurai M., Enokido K., Endo T., Tsunoda H. JSUM ultrasound elastography practice guidelines: breast. J Med Ultrason. 2013;40:359–391. doi: 10.1007/s10396-013-0457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelson E.B., Berg W.A., Merritt C.R. Elsevier; 2001. Toward a standardized breast ultrasound lexicon, BI-RADS: ultrasound. Seminars in roentgenology; pp. 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdullah N., Mesurolle B., El-Khoury M., Kao E. Breast imaging reporting and data system lexicon for US: interobserver agreement for assessment of breast masses. Radiology. 2009;252:665–672. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523080670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg W.A., Cosgrove D.O., Doré C.J., Schäfer F.K., Svensson W.E., Hooley R.J. Shear-wave elastography improves the specificity of breast US: the BE1 multinational study of 939 masses. Radiology. 2012;262:435–449. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krouskop T.A., Wheeler T.M., Kallel F., Garra B.S., Hall T. Elastic moduli of breast and prostate tissues under compression. Ultrason Imag. 1998;20:260–274. doi: 10.1177/016173469802000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans A., Whelehan P., Thomson K., McLean D., Brauer K., Purdie C. Quantitative shear wave ultrasound elastography: initial experience in solid breast masses. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R104. doi: 10.1186/bcr2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosgrove D.O., Berg W.A., Doré C.J., Skyba D.M., Henry J.-P., Gay J. Shear wave elastography for breast masses is highly reproducible. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1023–1032. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2340-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S.H., Moon W.K., Cho N., Chang J.M., Moon H.-G., Han W. Shear-wave elastographic features of breast cancers: comparison with mechanical elasticity and histopathologic characteristics. Invest Radiol. 2014;49:147–155. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denis M., Mehrmohammadi M., Song P., Meixner D.D., Fazzio R.T., Pruthi S. Comb-push ultrasound shear elastography of breast masses: initial results show promise. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denis M., Bayat M., Mehrmohammadi M., Gregory A., Song P., Whaley D.H. Update on breast cancer detection using comb-push ultrasound shear elastography. IEEE T Ul Transon Ferr. 2015;62:1644–1650. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2015.007043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denis M., Gregory A., Bayat M., Fazzio R.T., Whaley D.H., Ghosh K. Correlating tumor stiffness with immunohistochemical subtypes of breast cancers: prognostic value of comb-push ultrasound shear elastography for differentiating luminal subtypes. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayat M., Denis M., Gregory A., Mehrmohammadi M., Kumar V., Meixner D. Diagnostic features of quantitative comb-push shear elastography for breast lesion differentiation. PloS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang J.M., Moon W.K., Cho N., Yi A., Koo H.R., Han W. Clinical application of shear wave elastography (SWE) in the diagnosis of benign and malignant breast diseases. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2011;129:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai M., Du L., Gu J., Li F., Jia X. Virtual touch tissue quantification using acoustic radiation force impulse technology: initial clinical experience with solid breast masses. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:289–294. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregory A., Denis M., Bayat M., Kumar V., Kim B.H., Webb J. Predictive value of comb-push ultrasound shear elastography for the differentiation of reactive and metastatic axillary lymph nodes: a preliminary investigation. PloS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226994. e0226994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y., Li G.-Y., Zhou J., Zheng Y., Jiang Y.-X., Liu Y.-L. Size effect in shear wave elastography of small solid tumors–A phantom study. Extreme Mech Lett. 2020:100636. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon J.H., Jung H.K., Lee J.T., Ko K.H. Shear-wave elastography in the diagnosis of solid breast masses: what leads to false-negative or false-positive results? Eur Radiol. 2013;23:2432–2440. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamanaka N., Kaminuma C., Taketomi-Takahashi A., Tsushima Y. Reliable measurement by virtual touch tissue quantification with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: phantom study. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1239–1244. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.8.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillman J.R., Chen S., Davenport M.S., Zhao H., Urban M.W., Song P. Superficial ultrasound shear wave speed measurements in soft and hard elasticity phantoms: repeatability and reproducibility using two ultrasound systems. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45:376–385. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White M.C., Holman D.M., Boehm J.E., Peipins L.A., Grossman M., Henley S.J. Age and cancer risk: a potentially modifiable relationship. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:S7–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nazari S.S., Mukherjee P. An overview of mammographic density and its association with breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2018;25:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s12282-018-0857-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg W.A., Zhang Z., Lehrer D., Jong R.A., Pisano E.D., Barr R.G. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. Jama. 2012;307:1394–1404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barr R.G., Zhang Z. Effects of precompression on elasticity imaging of the breast: development of a clinically useful semiquantitative method of precompression assessment. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:895–902. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao A.A., Feneis J., Lalonde C., Ojeda-Fournier H. A pictorial review of changes in the BI-RADS fifth edition. Radiographics. 2016;36:623–639. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bercoff J., Tanter M., Chaffai S., Fink M. Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE ultrasonics symposium. 2002. Ultrafast imaging of beamformed shear waves induced by the acoustic radiation force. Application to transient elastography; pp. 1899–1902. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermont J., Bosson J., Francois P., Robert C., Rueff A., Demongeot J. Strategies for graphical threshold determination. Comput Methods Progr Biomed. 1991;35:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(91)90072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan M.I. Why the logistic function? A tutorial discussion on probabilities and neural networks. Comput Cogn Sci Tech Rep. 1995;9503 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin H.J., Kim M.-J., Kim H.Y., Roh Y.H., Lee M.-J. Comparison of shear wave velocities on ultrasound elastography between different machines, transducers, and acquisition depths: a phantom study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3361–3367. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4212-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S.H., Chang J.M., Kim W.H., Bae M.S., Cho N., Yi A. Differentiation of benign from malignant solid breast masses: comparison of two-dimensional and three-dimensional shear-wave elastography. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1015–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans A., Whelehan P., Thomson K., Brauer K., Jordan L., Purdie C. Differentiating benign from malignant solid breast masses: value of shear wave elastography according to lesion stiffness combined with greyscale ultrasound according to BI-RADS classification. Br J Canc. 2012;107:224–229. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang J.M., Moon W.K., Cho N., Kim S.J. Breast mass evaluation: factors influencing the quality of US elastography. Radiology. 2011;259:59–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correas J.-M., Tissier A.-M., Khairoune A., Khoury G., Eiss D., Hélénon O. Ultrasound elastography of the prostate: state of the art. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gregory A., Mehrmohammadi M., Denis M., Bayat M., Stan D.L., Fatemi M. Effect of calcifications on breast ultrasound shear wave elastography: an investigational study. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skerl K., Vinnicombe S., Thomson K., McLean D., Giannotti E., Evans A. Anisotropy of solid breast lesions in 2D shear wave elastography is an indicator of malignancy. Acda Radiol. 2016;23:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y-l, Gao Y., Chang C., Wang F., Zeng W., Chen J-j. Ultrasound shear wave elastography of breast lesions: correlation of anisotropy with clinical and histopathological findings. Canc Imag. 2018;18:11. doi: 10.1186/s40644-018-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]