This meta-analysis assesses randomized clinical trials of statins to determine the time to benefit for prevention of a first major adverse cardiovascular event in adults aged 50 to 75 years.

Key Points

Question

What is the time to benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in adults aged 50 to 75 years?

Findings

In this survival meta-analysis of 8 trials randomizing 65 383 adults, 2.5 (95% CI, 1.7-3.4) years were needed to avoid 1 cardiovascular event for 100 patients treated with a statin.

Meaning

These findings suggest that statin medications for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events may reduce cardiac events for some adults aged 50 to 75 years with a life expectancy of at least 2.5 years; no data suggest a mortality benefit.

Abstract

Importance

Guidelines recommend targeting preventive interventions toward older adults whose life expectancy is greater than the intervention’s time to benefit (TTB). The TTB for statin therapy is unknown.

Objective

To conduct a survival meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of statins to determine the TTB for prevention of a first major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) in adults aged 50 to 75 years.

Data Sources

Studies were identified from previously published systematic reviews (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and US Preventive Services Task Force) and a search of MEDLINE and Google Scholar for subsequently published studies until February 1, 2020.

Study Selection

Randomized clinical trials of statins for primary prevention focusing on older adults (mean age >55 years).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two authors independently abstracted survival data for the control and intervention groups. Weibull survival curves were fit, and a random-effects model was used to estimate pooled absolute risk reductions (ARRs) between control and intervention groups each year. Markov chain Monte Carlo methods were applied to determine time to ARR thresholds.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time to ARR thresholds (0.002, 0.005, and 0.010) for a first MACE, as defined by each trial. There were broad similarities in the definition of MACE across trials, with all trials including myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality.

Results

Eight trials randomizing 65 383 adults (66.3% men) were identified. The mean age ranged from 55 to 69 years old and the mean length of follow-up ranged from 2 to 6 years. Only 1 of 8 studies showed that statins decreased all-cause mortality. The meta-analysis results suggested that 2.5 (95% CI, 1.7-3.4) years were needed to avoid 1 MACE for 100 patients treated with a statin. To prevent 1 MACE for 200 patients treated (ARR = 0.005), the TTB was 1.3 (95% CI, 1.0-1.7) years, whereas the TTB to avoid 1 MACE for 500 patients treated (ARR = 0.002) was 0.8 (95% CI, 0.5-1.0) years.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that treating 100 adults (aged 50-75 years) without known cardiovascular disease with a statin for 2.5 years prevented 1 MACE in 1 adult. Statins may help to prevent a first MACE in adults aged 50 to 75 years old if they have a life expectancy of at least 2.5 years. There is no evidence of a mortality benefit.

Introduction

The American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) all recommend hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in adults aged 40 to 75 years who have an elevated risk (most often defined as ≥7.5% risk of major adverse cardiovascular event [MACE] within 10 years).1,2,3 These guidelines also emphasize the importance of individualizing statin decisions through clinician-patient discussions, owing to the tremendous heterogeneity in cardiovascular risk, comorbidity burden, and life expectancy in this population.

Although the benefits of statins to decrease cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke have been well documented for adults younger than 75 years, when these benefits occur is unclear. In contrast, the burdens of statins appear to occur relatively quickly. The most commonly reported adverse effect of statins is myalgia, which in some observational studies is reported by as many as 30% of patients within weeks of starting therapy.4 In addition, statins may contribute to immediate polypharmacy5 and drug-disease6,7,8,9 or drug-drug interactions,10 especially among the growing number of older adults with multiple comorbidities and limited life expectancy who are already using a large number of medications. Indeed, a randomized clinical trial in older adults with a life expectancy of less than 1 year showed worse self-reported quality of life at 60 days in patients who continued long-term statin therapy vs those from whom it was withdrawn.11

These short-term potential burdens and harms of statins, both perceived and real, highlight the importance of individualizing statin therapy so that it is preferentially targeted to the patients who are most likely to live long enough to also experience its benefits. Lee et al12 previously proposed a framework for individualizing prevention decisions in older adults that focuses on a patient’s life expectancy and the intervention’s time to benefit (TTB). Older adults with a limited life expectancy (usually defined as less than an intervention’s TTB) should avoid preventive interventions with an extended TTB, because these older adults would be exposed to the up-front harms and burdens of the intervention with little chance that they survive to experience the benefit. Although many indexes to predict life expectancy for older adults have been validated and are available through websites such as ePrognosis (ePrognosis.ucsf.edu), the TTB of statins for the primary prevention of MACEs is unclear.

To help clinicians individualize statin therapy for primary prevention in older adults, we conducted a survival meta-analysis of the major randomized clinical trials to determine the TTB for statins, which we defined as the time from statin initiation to the prevention of a first MACE. We focused our analysis on adults aged 50 to 75 years because this age group has the most data from randomized clinical trials of the benefit of statins.

Methods

Literature Search

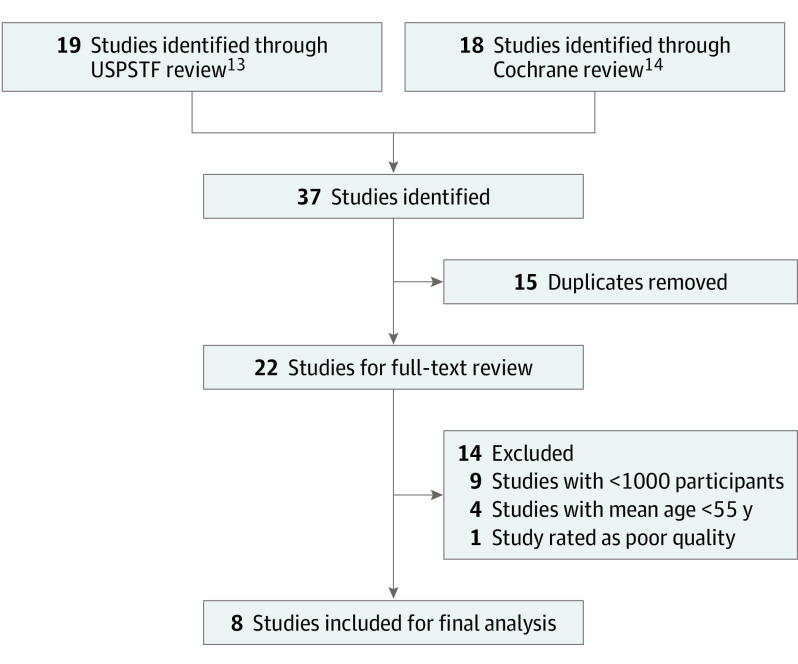

This study relied on publicly available, previously published studies. The Committee of Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, determined that this research did not meet the definition of human subjects research. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines. Two independent reviewers (L.C.Y. and A.R.) identified published trials from prior systematic reviews by the USPSTF13 and Taylor et al14 in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We also searched MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar for subsequently published relevant studies until February 1, 2020, using the search terms statin, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, primary prevention, older, and cardiovascular. The trial names, authors, and references of included trials and published systematic reviews were screened for other potential trials. The search strategy is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study Identification and Selection.

Google Scholar and MEDLINE were searched for subsequently published relevant studies. No additional studies were identified. USPSTF indicates US Preventive Services Task Force.

Eligibility Criteria

To identify trials with patients in our target age group, we only included randomized clinical trials with a mean patient age of older than 55 years. Given our focus on primary prevention, we focused on trials in which less than 15% of participants had known preexisting cardiovascular disease. In addition, we focused on larger trials (>1000 participants) and trials rated as high or moderate quality by Cochrane and USPSTF criteria.15

Data Extraction

Two data extractors (L.C.Y. and A.R.) obtained relevant data independently using a predetermined data collection table. Any discrepancies between data extractors were resolved by an independent data extractor (S.J.L.)

Outcomes of Interest

Our primary outcome was time to the first major cardiovascular end point, defined by each trial as a composite of cardiovascular outcomes. Although each trial included different cardiovascular events as part of their major cardiovascular end point, there were broad similarities across trials. All trials included myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality, and 4 trials each included revascularization,16,17,18,19 angina,16,17,18,20 and stroke16,18,19,21 (see eTable in the Supplement for how each study defined cardiovascular events).

Statistical Analysis

Unlike most meta-analyses in which the statistic of interest (ie, hazard ratio) is reported in individual studies, our statistic of interest was the TTB, which was not reported by individual studies. To obtain the TTB for each study, we fit random-effects Weibull survival curves using the annual event data for the control and intervention groups, allowing both the scale and shape Weibull parameters to vary for each arm of the study. Using 100 000 Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations, we obtained point estimates, standard errors, and 95% CIs for rates of major adverse cardiovascular end points in the control and intervention arms of each study. From this model, we obtained estimates of time to specific absolute risk reduction (ARR) thresholds (0.002, 0.005, and 0.010) for each study. These ARR thresholds have been used in previously published TTB analyses22,23 and risk prediction tools for shared decision-making.24,25 Next, we pooled the estimates from each study using a random-effects meta-analysis model. Heterogeneity and its effects were evaluated by using the I2 statistic. The Markov chain Monte Carlo computations were conducted in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc); estimates for individual studies were obtained using R, version 3.4.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing); and a random-effects meta-analysis was conducted in STATA, version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC). We used similar methods to estimate TTB for cancer screening in previously published studies.22,23 We used the method of DerSimonian and Laird26 to estimate and assess statistical significance for the overall comparison effect. Differences were considered significant at a 2-sided P = .05.

Results

We identified 8 randomized clinical trials16,17,18,19,20,21,27,28 that met our inclusion criteria (65 383 participants; 33.7% women and 66.3% men). The trials ranged in size from 1129 to 17 802 participants. The mean age was similar across trials, ranging from 55 (range, 45-64) to 69 (range, 65-75) years. These trials enrolled participants from 1989 to 2010 and were generally successful in recruiting participants without known cardiovascular disease, with all studies reporting less than 10% prevalence of prior cardiovascular disease (including prior angina, myocardial infarction, and/or stroke). Seven trials16,17,18,20,21,27,28 reported baseline blood pressures meeting the 2017 ACC/AHA3 criteria for elevated or stage 1 hypertension (range, 132/78 to 164/95 mm Hg) and 7 trials16,17,18,19,20,21,27 had above-optimal to borderline high mean low-density-lipoprotein (108-192 mg/dL; to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259) levels based on the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III.29 Two trials18,19 focused exclusively on persons with type 2 diabetes; in the remaining studies, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes ranged from 2% to 25%. Characteristics of included trials are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Source (study) | No. of participants | Age, ya | Women, % | Mean baseline cardiovascular risk factors | Treatment | Follow-up duration, y | MACE ARR, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP, mm Hg | LDL-C level, mg/dL | Mean HDL-C level, mg/dL | |||||||

| Low-intensity statin | |||||||||

| Downs et al,20 1998 (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) | 6605 | 58 (45-73) | 15 | 138/78 | 150 | 36 | Lovastatin, 20-40 mg | 5 | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.0) |

| Nakamura et al,17 2006 (MEGA) | 7832 | 58 (40-70) | 68 | 132/78 | 157 | 58 | Pravastatin sodium, 10-20 mg | 5 | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.5) |

| Moderate-intensity statin | |||||||||

| Shepherd et al,27 1995 (WOSCOPS) | 6595 | 55 (45-64) | 0 | 136/84 | 192 | 44 | Pravastatin sodium, 40 mg | 5 | 2.3 (1.1 to 3.4) |

| Sever et al,28 2003 (ASCOT-LLA) | 10 305 | 63 (40-79) | 19 | 164/95 | 133 | 51 | Atorvastatin calcium, 10 mg | 3 | 1.4 (0.6 to 2.1) |

| Knopp et al,19 2006 (ASPEN) | 2410 | 61 (40-75) | 34 | 133/77 | 114 | 47 | Atorvastatin calcium, 10 mg | 4 | 0.4 (−2.4 to 3.1) |

| Neil et al,18 2006 (CARDS) | 1129 | 69 (65-75) | 31 | 149/82 | 118 | 53 | Atorvastatin calcium, 10 mg | 4 | 3.9 (NR) |

| Yusuf et al,21 2016 (HOPE-3) | 12 705 | 66 (>55) | 46 | 138/82 | 128 | 45 | Rosuvastatin calcium, 10 mg | 6 | 1.1 (0.4 to 1.8) |

| High-intensity statin | |||||||||

| Ridker et al,16 2008 (JUPITER) | 17 802 | 66 (>50)b | 38 | 134/80 | 108 | 49 | Rosuvastatin calcium, 20 mg | 2 | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.6) |

Abbreviations: AFCAPS/TexCAPS, Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study; ARR, absolute risk reduction; ASCOT-LLA, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid Lowering Arm; ASPEN, Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease End Points in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus; BP, blood pressure; CARDS, Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOPE, Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study; JUPITER, Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MEGA, Management of Elevated Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention Group of Adult Japanese; NR, not reported; WOSCOPS, West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study.

SI conversion factor: To convert cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean (range).

Reported as median.

Two studies17,20 (14 437 participants) examined low-intensity statins (eg, pravastatin sodium, 10 mg); 5 studies18,19,21,27,28 (33 144 participants), moderate-intensity statins (eg, rosuvastatin calcium, 10 mg); and 1 study16 (17 802 participants), high-intensity statins (eg, rosuvastatin calcium, 20 mg). Follow-up duration ranged from 2 to 6 years, and the ARR of MACE varied from 0.4% (95% CI, −2.4% to 3.1%) in the ASPEN study to 3.9% (95% CI not available) in the CARDS study. One study (JUPITER)16 reported that statins decreased all-cause mortality; a second study (WOSCOPS)27 reported that statins decreased cardiovascular mortality. No other study found that statins decreased mortality.

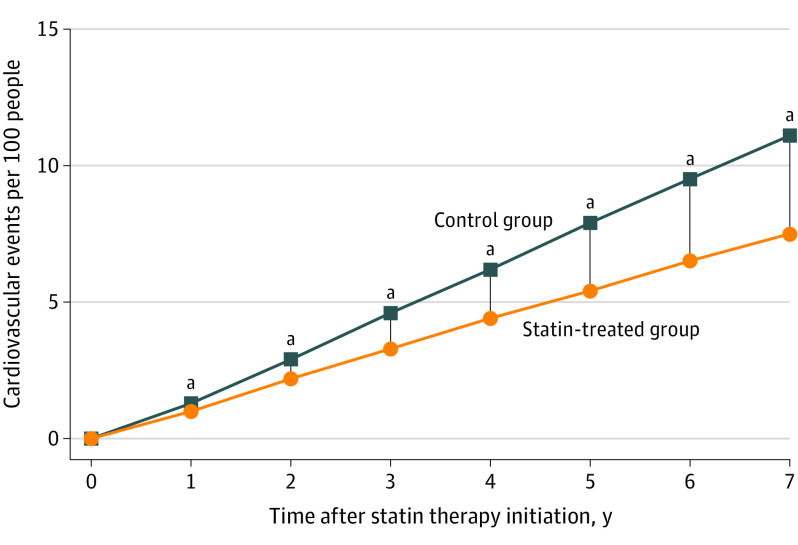

Our survival meta-analysis suggested that the benefit of statin therapy increased steadily with longer follow-up (Figure 2). For example, at 1 year, 0.3 MACEs were prevented for 100 persons treated with statins, increasing to 1.3 MACEs prevented at 3 years. By 5 years, 2.5 MACEs were prevented for 100 persons treated with a statin.

Figure 2. Pooled Mortality Curves for Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE).

Values are the difference in MACE rates between control and statin-treated groups, which is equivalent to the absolute risk reduction and the number of cardiovascular events that are prevented per 100 people treated with a statin.

aP < .05 between groups.

We determined that 2.5 (95% CI, 1.7-3.4) years were needed to prevent 1 MACE per 100 adults aged 50 to 75 years treated with a statin (ARR = 0.010) (Table 2 and eFigure in the Supplement). Similarly, 200 adults aged 50 to 75 years would need to be treated with a statin for 1.3 (95% CI, 1.0-1.7) years to avoid 1 MACE (ARR, 0.005), and 500 adults aged 50 to 75 years would need to be treated with a statin for 0.8 (95% CI, 0.5-1.0) years to avoid 1 MACE (ARR, 0.002).

Table 2. TTB for the Primary Prevention of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events for Older Adults.

| Source (study) | TTB (95% CI), ya | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ARR = 0.002 | ARR = 0.005 | ARR = 0.010 | |

| Downs et al,20 1998 (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) | 1.1 (0.3-2.8) | 1.9 (0.8-3.8) | 3.2 (1.7-5.5) |

| Nakamura et al,17 2006 (MEGA) | 1.6 (0.4-4.4) | 3.5 (1.3-7.8) | 6.5 (3.2-11.8) |

| Shepherd et al,27 1995 (WOSCOPS) | 0.9 (0.2-2.3) | 1.5 (0.6-3.1) | 2.5 (1.3-4.4) |

| Sever et al,28 2003 (ASCOT-LLA) | 0.6 (0.2-1.3) | 1.4 (0.6-2.9) | 3.4 (1.3-7.3) |

| Knopp et al,19 2006 (ASPEN) | 2.5 (0.5-8.4) | 2.9 (0.8-7.7) | 3.5 (1.3-7.9) |

| Neil et al,18 2006 (CARDS) | 0.7 (0.1-2.9) | 1.0 (0.2-3.0) | 1.4 (0.5-3.4) |

| Yusuf et al,21 2016 (HOPE-3) | 1.9 (0.4-5.2) | 3.4 (1.2-7.8) | 5.2 (2.8-8.8) |

| Ridker et al,16 2008 (JUPITER) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) |

| Summary TTB, y | 0.8 (0.5-1.0) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 2.5 (1.7-3.4) |

| Test of heterogeneity | |||

| I2, % | 0 | 0 | 34.3 |

| P value | .90 | .71 | .15 |

Abbreviations: AFCAPS/TexCAPS, Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study; ARR, absolute risk reduction; ASCOT-LLA, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Lipid Lowering Arm; ASPEN, Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in Non–Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus; CARDS, Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study; HOPE, Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study; JUPITER, Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin; MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event; MEGA, Management of Elevated Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention Group of Adult Japanese; TTB, time to benefit; WOSCOPS, West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study.

ARR = 0.002 is the time to prevent 1 cardiovascular event per 500 persons treated with a statin for primary prevention; ARR = 0.005, time to prevent 1 cardiovascular event per 200 persons treated with a statin; and TTB for ARR = 0.010, time to prevent 1 cardiovascular event per 100 persons treated with a statin.

The TTB to specific ARR thresholds varied across studies (Table 2). For example, although the pooled time to prevent 1 MACE for 100 persons treated (ARR = 0.010) was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.7-3.4) years, the TTB for individual trials ranged from 1.4 (95% CI, 0.5-3.4) years in the CARDS study to 6.5 (95% CI, 3.2-11.8) years in the MEGA study. Statistical tests for heterogeneity demonstrated that variation in the effect estimates between different studies at each ARR threshold were likely due to chance (P = .90 at ARR = 0.002, P = .71 at ARR = 0.005, and P = .15 at ARR = 0.010), and our measure of inconsistency showed that the percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity was low to moderate (I2 = 0 at ARR = 0.002 and 0.005 and 34.3% at ARR = 0.010).

Discussion

In this survival meta-analysis, the TTB to prevent 1 MACE for 100 adults aged 50-75 years treated with statins was 2.5 years. These results suggest that statins are most likely to benefit adults aged 50-75 years with a life expectancy of greater than 2.5 years and less likely to benefit those with a life expectancy of less than 2.5 years. In fact, because the potential harms of statins occurs within weeks, whereas the benefits take years, adults aged 50 to 75 years with a life expectancy of less than 2.5 years may be more likely to be harmed than helped by statin therapy.

Results in the Context of Previous Studies

Although this is the first study, to our knowledge, to use quantitative methods to determine the TTB for statins, the concept of TTB for statins has long been recognized as potentially important, and our results are consistent with previous findings on this topic.30 Holmes and colleagues31 conducted a systematic review of statin randomized controlled trials, focusing on TTB for all-cause mortality. Similar to our mortality findings, they found only 2 of 8 trials showed all-cause mortality benefit. In the 2 trials that did show benefit, the authors determined the TTB through visual observation of curve separation at 1.5 years for the ACAPS study32 and 2.5 to 3.0 years for the JUPITER study.16 Our study’s focus on MACE makes a direct comparison challenging. However, the relative similarity in TTB estimates from the study by Holmes et al31 and our study supports the general conclusion that it takes approximately 1.5 to 3.0 years for the benefits of statin therapy to be seen.

Uncertainty About the Harms of Statins

There is tremendous uncertainty surrounding the nature and frequency of statin-associated adverse events, complicating discussions about the potential benefits and risks of statins.33,34 Meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials of statins have generally shown that adverse event rates are similar in participants randomized to statin or placebo, suggesting no significant increase in adverse events with statins.35,36 However, many have argued that because trial populations are generally healthier than real-world clinical populations, observational studies may provide a more accurate estimate of the frequency of adverse events in clinical practice.37,38,39 These observational studies of statins in real-world clinical populations suggest that 10% to 25% of statin users have muscular symptoms,6,40,41,42 with a substantial minority discontinuing statins owing to the severity of these symptoms.43 Although studies suggest that patients who discontinue statins owing to adverse effects are often able to tolerate statins subsequently,44 high-quality observational studies suggest that statin-associated adverse events occur more frequently in clinical practice than randomized clinical trials.33,37,38 In addition, observational studies suggest a small but likely real increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes (about 0.2% per year of treatment).45

Taken together, our TTB estimation and previously published studies suggest that statins have substantial benefits (reducing MACEs by 0.4%-3.9% during 2.5 years) (Table 1) that accrue over time. Counterbalancing these benefits are the burdens and potential harms of statin therapy that usually occur within weeks of initiation.

Individualizing Decisions: Statin Risk-Benefit Discussions

These results can inform the risk-benefit discussions for statin treatment recommended by the AHA/ACC guidelines.3 For some patients, the delayed benefits of statin treatment (avoiding myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death) may be more important than the risks (most commonly myalgias and polypharmacy) that are usually reversible on discontinuation of statin treatment. For other patients with limited life expectancy (approximately 2.5 years), the prospect of immediate risks for a 1 in 100 chance of benefit in several years may lead to a decision to forego statin treatment. In fact, we may be underestimating the harms of statin therapy for patients with limited life expectancy, because our estimate of harms are from healthier populations, and patients with limited life expectancy and high comorbidity burden are likely at higher risk for adverse effects of statins.46,47,48,49 Given the uncertainty in the true rates of harms and the tremendous heterogeneity of older adults, the values and preferences of individual older adults should play a central role in decisions about statin therapy.

Individual patients may be best served by focusing on TTB results from an individual study rather than focusing on our pooled TTB results. For example, patients on low doses of statins may be best served by focusing on the MEGA study results showing relatively long times to benefit (ie, 6.5 years for an ARR of 0.010), because the MEGA trial used 10 to 20 mg of pravastatin sodium. Conversely, patients with diabetes may be best served by focusing on the CARDS study results showing relatively short times to benefit (ie, 1.4 years for an ARR of 0.010), because the CARDS study focused on persons with type 2 diabetes. Thus, although our summary TTB results provide a global estimate for primary prevention with statins, individual patients may be best served by focusing on TTB results from individual studies with similar statin interventions or patient characteristics.

Strengths and Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in light of this study’s strengths and limitations. A major strength of our study is that this is the first, to our knowledge, to use quantitative methods to determine the TTB for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events with statins in adults aged 50 to 75 years and fills a critical gap for risk discussions about statins, especially for those patients with a limited life expectancy.

One limitation of our study is a direct result of the age range of study participants in previously published randomized trials for statins used in primary prevention. Although our focus was on older adults, we found only 3 studies with a mean age older than 65 years, leading us to include studies with younger participants. We were unable to include studies such as the Pravastatin in Elderly Individuals at Risk of Vascular Disease (PROSPER)50 owing to the high rates of preexisting cardiovascular disease (>20%, the exclusion threshold used by previously published systematic reviews13,14 for guidelines on primary prevention). In the studies included in our meta-analyses, therefore, most participants were aged 50 to 75 years, making our results most relevant for adults in this age group. Given the small numbers of study participants older than 75 years, it is unclear whether our results are applicable to these older adults, consistent with acknowledged limitations of the 2019 guidelines from the ACC/AHA3 and USPSTF.2,13 This is not surprising, because our analysis relied on many of the same studies that formed the evidence base for the previous guidelines. Ongoing studies, such as the Statin Therapy for Reducing Events in the Elderly (STAREE) trial, should provide valuable data to inform statin prescribing decisions in adults older than 75 years.51

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, only 1 of 8 randomized trials found that statins decreased all-cause mortality when used for primary prevention. We found that 100 adults aged 50 to 75 years would need to be treated for 2.5 years to avoid 1 MACE. This result suggests that statin treatment is most appropriate for adults aged 50-75 years with a life expectancy of greater than 2.5 years. For those with a life expectancy of less than 2.5 years, the harms of statins may outweigh the benefits. These results reinforce the importance of individualizing statin treatment decisions by incorporating each patient’s values and preferences.

eTable. Definition of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in the Included Studies

eFigure. Forest Plots for ARRs

References

- 1.Colantonio LD, Booth JN III, Bress AP, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure treatment guideline recommendations and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(11):1187-1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1997-2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):e285-e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson PD, Panza G, Zaleski A, Taylor B. Statin-associated side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(20):2395-2410. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos TRA, Silveira EA, Pereira LV, Provin MP, Lima DM, Amaral RG. Potential drug-drug interactions in older adults: a population-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(12):2336-2346. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanlon JT, Perera S, Newman AB, et al. ; Health ABC Study . Potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in well-functioning community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(2):228-233. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration Drug safety communication: interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury. Updated January 19, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-interactions-between-certain-hiv-or-hepatitis-c-drugs-and-cholesterol

- 8.Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A. Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Circulation. 2004;109(23)(suppl 1):III50-III57. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al. ; ACCORD Study Group . Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1563-1574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellosta S, Corsini A. Statin drug interactions and related adverse reactions: an update. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(1):25-37. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1394455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691-700. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC. Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2609-2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, Daeges M, Jeanne TL. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316(19):2008-2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor F, Huffman M, Macedo A, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published January 31, 2013. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.cochrane.org/CD004816/VASC_statins-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. US Preventive Services Task Force Procedure Manual Published December 2015. Accessed February 15, 2020. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFile/6/7/procedure-manual_2015/pdf

- 16.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. ; JUPITER Study Group . Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195-2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, et al. ; MEGA Study Group . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1155-1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69472-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neil H, Demicco D, Luo D, et al. Analysis of efficacy and safety in patients aged 65–75 years at randomization: Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS). Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2378-2384. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knopp RH, d’Emden M, Smilde JG, Pocock SJ. Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in the prevention of cardiovascular end points in subjects with type 2 diabetes: the Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in Non–Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (ASPEN). Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1478-1485. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1615-1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusuf S, Bosch J, Dagenais G, et al. ; HOPE-3 Investigators . Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2021-2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang V, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening: survival meta-analysis of flexible sigmoidoscopy trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1662. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye S, Leppin AL, Chan AY, et al. An informatics approach to implement support for shared decision making for primary prevention statin therapy. MDM Policy Pract. 2018;3(1):2381468318777752. doi: 10.1177/2381468318777752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Montori VM, Arciniega J, McGinn T. The Statin Choice decision aid in primary care: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):138-140. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. ; West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group . Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(20):1301-1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. ; ASCOT investigators . Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1149-1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipsy RJ The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(1)(suppl):2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray KK, Cannon CP. Time to benefit: an emerging concept for assessing the efficacy of statin therapy in cardiovascular disease. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2005;4(1):43-45. doi: 10.1097/01.hpc.0000154979.98731.5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes HM, Min LC, Yee M, et al. Rationalizing prescribing for older patients with multimorbidity: considering time to benefit. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(9):655-666. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0095-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furberg CD, Adams HP Jr, Applegate WB, et al. ; Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study (ACAPS) Research Group . Effect of lovastatin on early carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 1994;90(4):1679-1687. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.4.1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Parker BA; The National Lipid Association’s Muscle Safety Expert Panel . An assessment by the Statin Muscle Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(3)(suppl):S58-S71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas-Fernandez CH, Goldstein LB, Levey AI, Taylor BA, Bittner V; The National Lipid Association’s Safety Task Force . An assessment by the Statin Cognitive Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(3)(suppl):S5-S16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedro-Botet J, Rubiés-Prat J. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: beware of the nocebo effect. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2445-2446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adhyaru BB, Jacobson TA. Unblinded ASCOT study results do not rule out that muscle symptoms are an adverse effect of statins. Evid Based Med. 2017;22(6):210. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10 138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(3):208-215. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navar AM, Peterson ED, Li S, et al. Prevalence and management of symptoms associated with statin therapy in community practice: insights from the PALM (Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management) Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(3):e004249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson TA, Cheeley MK, Jones PH, et al. The Statin Adverse Treatment Experience Survey: experience of patients reporting side effects of statin therapy. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):415-424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Bégaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403-414. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-5686-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosshammer D, Lorenz G, Meznaric S, Schwarz J, Muche R, Mörike K. Statin use and its association with musculoskeletal symptoms—a cross-sectional study in primary care settings. Fam Pract. 2009;26(2):88-95. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaipichit N, Krska J, Pratipanawatr T, Jarernsiripornkul N. Statin adverse effects: patients’ experiences and laboratory monitoring of muscle and liver injuries. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(2):355-364. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0068-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenbaum D, Dallongeville J, Sabouret P, Bruckert E. Discontinuation of statin therapy due to muscular side effects: a survey in real life. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(9):871-875. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):526-534. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newman CBPD, Preiss D, Tobert JA, et al. ; American Heart Association Clinical Lipidology, Lipoprotein, Metabolism and Thrombosis Committee, a Joint Committee of the Council on Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Stroke Council . Statin safety and associated adverse events: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(2):e38-e81. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gutiérrez-Valencia M, Izquierdo M, Cesari M, Casas-Herrero Á, Inzitari M, Martínez-Velilla N. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(7):1432-1444. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herr M, Robine JM, Pinot J, Arvieu JJ, Ankri J. Polypharmacy and frailty: prevalence, relationship, and impact on mortality in a French sample of 2350 old people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(6):637-646. doi: 10.1002/pds.3772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870-2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DuGoff EH, Canudas-Romo V, Buttorff C, Leff B, Anderson GF. Multiple chronic conditions and life expectancy: a life table analysis. Med Care. 2014;52(8):688-694. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. ; PROSPER study group. PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk . Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1623-1630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11600-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gurwitz JH, Go AS, Fortmann SP. Statins for primary prevention in older adults: uncertainty and the need for more evidence. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1971-1972. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Definition of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in the Included Studies

eFigure. Forest Plots for ARRs