Abstract

Purpose of the review

To describe current understanding and the relationship between urinary incontinence (UI), mobility limitations, and disability in older women with pelvic floor disorders.

Recent Findings

UI is a prevalent pelvic floor disorder in older women and is considered to be one of the most common geriatric problems. There is no clear classification of UI as a disease versus UI as a geriatric syndrome in the current literature. Since the disability is also prevalent in older women, an evaluation of the relationship between UI and disability, may improve ourunderstanding of UI as a disease or a geriatric syndrome. This relationship may be classified through different pathways. Some evidence suggests that mobility disabilities and UI in older women may have bidirectional pathophysiologic mechanisms through generalized muscle dysfunction.

Summary

Expanding research on the mechanisms of UI, mobility limitations, and disability in older women as well as their associations will enhance our insight into clinical, pharmacological, environmental, behavioral, and rehabilitative interventions. It will also lead to improved measures for prevention and treatment UI in older women. Thus, understanding UI, mobility limitations, and disability can have substantial implications for both clinical work and research in this area.

Keywords: urinary incontinence, geriatric syndrome, disease, disability, mobility

Pelvic Floor Disorders

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs), most commonly affecting older women, include urinary incontinence (UI - involuntary loss of urine), fecal incontinence (FI - involuntary loss of feces), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP – descent of pelvic organs) [1]. PFDs represent a major public health problem in the United States. A cross-sectional analysis of 1961 non-pregnant women (≥ 20 years) from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey revealed symptomatic UI as the most prevalent PFD found in 15.7% of women, followed by FI - 9.0%, and then by POP - 2.9% [2]. The prevalence of at least 1 PFD in the same cohort was 23.7% underscoring the high prevalence of these conditions. The proportion of women reporting at least 1 disorder increases incrementally with age, ranging from 9.7% in women between ages 20 and 39 years to 40.6-49.7% in those aged 80 years or older [2,3]. Given the changes in current demographics in the United States, it is estimated that the prevalence of PFDs will even increase further. The number of American women expected to develop with at least one PFD will increase from 28.1 million in 2010 to 43.8 million in 2050. The number of American women with UI is estimated to rise by 55% from 18.3 to 28.4 million between 2010 and 2050 [4]. Thus, the demands to prevent UI and/or treat older women with UI will continue to increase.

Women with UI suffer physical and emotional distress with higher rates of depression and experience diminished quality of life, reduction in work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being [3,5-7]. In addition to a significant burden at an individual level, UI is costly to society. After adjustment for age and co-morbid conditions, the risk of hospitalization is 30% higher and admission to a nursing facility is two times greater for incontinent women compared to their continent counterparts [8]. Not discounting these direct consequences to individual health, the direct economic burden of incontinence is enormous, accounting for an estimated $65.9 billion in 2007 and projected to increase to $82.6 billion in 2020 [9]. Given the immense health-related and fiscal costs of UI, more integrated management strategies are necessary to improve clinical outcomes and decrease UI in older women.

Urinary Incontinence – a Symptom, a Disease, and a Geriatric Syndrome

“Incontinence does not kill you – it just takes away your life”, one of the participants said during a focus group discussion [10]. UI is an embarrassing PFD that is frequently present during the span of a woman's life, as a symptom, a disease, or as a geriatric syndrome. A child with behavioral problems may develop bedwetting. A young woman may have UI symptoms as a result of a urinary tract infection or even a sexually transmitted disease. A middle-aged multiparous female develops UI, as a disease, that is treated with physical therapy, medications, or surgeries. Finally, when a woman ages with increased functional limitations and, eventually, UI, as a geriatric syndrome, ensues.

The pathophysiology of UI is multi-factorial and may vary at different stages of life [11]. UI, as a symptom, easily resolves when an underlying condition is identified and adequately treated. The most common risk factors for development of UI, as a disease, are obesity, multiparity, mode of delivery, family history, increased age, diabetes, stroke, depression, vaginal atrophy, pelvic surgery, radiation, and even systemic hormonal replacement therapy [11]. UI, as a disease, has 3 most common types - stress, urgency, and mixed (stress and urgency) incontinence [12]. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the involuntary leakage of urine with effort or exertion, during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as coughing, sneezing or lifting [1]. It develops due to weakness in pelvic floor muscles and ligaments [11]. It can be treated with pelvic floor muscle training or surgery [13]. Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), which falls under the umbrella of the overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome, is the involuntary loss of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by the sensation of urgency, a sudden compelling desire to urinate that is difficult to defer [1]. It is believed to occur due to neuromuscular imbalance at the bladder muscle, sacral innervation, and/or spinal and cortical levels of regulation [14]. The treatment is directed to address these regulatory problems with muscle training, medications, or nerve stimulation [14]. Finally, mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) that combines both stress and urgency symptoms is the most common type of UI. While SUI is more prevalent in younger women, MUI is the most common type of UI in older women (age ≥ 60 years), as urgency symptoms increase and stress symptoms decrease in prevalence through the ninth decade of life [15]. The accepted treatment approach for UI in older women is generally similar to the UI treatment in their younger counterparts. However, there is a continued dearth of level I evidence for such interventions in the older women with only a small number of older women included in clinical trials from which these treatment recommendations have been derived.

Multiple studies have classified UI in older women as one of the most common geriatric syndromes. In contrast to the term “disease”, geriatric syndromes refer to “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effect of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges” [16]. Therefore, the use of the term “geriatric syndrome” stresses “multiple causation of a unified manifestation” [17-19]. There is no consensus as to which conditions to consider as geriatric syndromes, but UI, falls, depression, cognitive impairment, including delirium, pressure ulcers, dizziness, and sensory impairment are often included [20]. The evaluation of 29,544 women aged ≥ 65 years from the Women's Health Initiative observational study revealed a high prevalence of geriatric syndromes with 76.3% of women in this population having at least one geriatric syndrome. UI, as a geriatric syndrome, was one of the most common conditions occurring in 29.3% (95% CI 28.8 – 29.9%) of participants [20]. In this cohort, for women with four or fewer geriatric syndromes UI and hearing impairment were most common geriatric syndromes. For those women with five or more geriatric syndromes, UI, dizziness, hearing and visual impairment were the most common geriatric syndromes, thus emphasizing that UI is one of the most common geriatric syndromes. Research has shown that UI, as a urologic disease, develops due to weakness in pelvic floor muscles and ligaments with presenting symptoms of SUI, or due to neuromuscular imbalance at the bladder muscle, dysregulation of sacral innervation and/or innervations at the spinal level and/or cortex with variable symptoms of OAB or UUI [11]. However, UI as a geriatric syndrome is not currently well defined. One could consider UI as geriatric syndrome in older women when multifactorial health conditions and functional limitations develop in addition to urologic abnormalities. Current clinical approach to treat UI in older women does not include the evaluation of women for functional limitations and, therefore, potentially missing to address non-urologic factors responsible for the development of UI, as a geriatric syndrome, in older women. Improved research and knowledge of UI and functional limitation in older women may lead us to better understanding in pathophysiology of UI in older women, to a paradigm shift in clinical approach and treatment of older women with UI, and eventually better delineation of UI, as a disease and as a geriatric syndrome.

Disabilities in Older Women

Disability is defined as the expression of physical or mental limitations in a social context or a gap between the person's capabilities and the demands of the environment. The pathway to disability begins from pathology with progression to impairment and then to physical, functional, and/or cognitive limitations, negatively impacting person's movements, senses, cognition, and others. According to the original classification scheme proposed by Nagi, functional limitations are defined as “limitations in performance at the level of the whole organism or person” [21,22]. By contrast, disability is defined as a “limitation in performance socially defined roles and tasks within a sociocultural and physical environment” [21,22]. Disability in older adults is an important and growing public health concern. It results in greater use of medical care, more institutionalizations, and poor physical and mental health [23-25]. Using objective measures or self-report, functional decrements can be assessed in different domains including impairments such as upper and lower body weakness, functional limitations, such as slow gait speed or chair rise time, and disability, such as need for help in performing Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs (IADLs - preparing meals, managing money, shopping for groceries or personal items, performing light or heavy housework, and using a telephone). Objective measures of physical performance have been promoted as useful measurements in the assessment of physical function [22]. Common tests to evaluate upper extremity functional limitations include pegboard tests and picking up objects while lower extremity functional limitations are commonly assessed with tests of gait speed and time to rise from a chair. The chair rise and gait speed assessments are frequently combined in some variant of the up-and-go test [22].

Compared to men, older women have a higher incidence and prevalence of functional limitations than men [26]. Women live longer than men, but also have worse health and higher rates of functional disabilities [27]. In 2011 the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey revealed staggering numbers of women with various disabilities in the United States. In one survey, out of all (23.633 million) female Medicare beneficiaries, there were 11.9 million (50.4%) with lower body mobility limitations (defined “little, some, a lot of difficulty, or could not walk a quarter of a mile), 9.9 million (42%) with upper extremities limitations (defined as a little, some, or a lot of difficulty, or could not reach or extend arms above shoulder level and write or handle and grasp small objects), and 11.7 million (49.5%) with functional disabilities in ADLs and/or IADLs [28]. The overwhelming majority of women aged >85 years had some functional limitations with a prevalence of 52.58% for upper extremities limitations and 78.17% for mobility disability, respectively.

UI and Disabilities in Older Women

Few reports focus on disabilities in older women with PFDs or UI. Nieto et al. recently described good functional status using self-reported and objective measures in younger women (mean age 58.4 years) undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery [29]. The baseline prevalence for ADLs and IADLs limitations in women ≥ 65 years undergoing surgery for POP was 31% and 12%, respectively in the study by Oliphant et al. [30]. Ereckson et al. showed that out of 150 women 65 years and older, presenting to clinic for a new consultation for PFD, 46 (30.7%) reported functional difficulty with dependence in performing at least one ADL activity [31]. Greer et al evaluated the prevalence of self-reported disabilities in a cohort of 4,458 women ≥ 40 years of age, with and without UI, from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005-2010 [32]. In this study, disabilities were measured based on self-reporting using the Physical Function Questionnaire. The authors reported the highest weighted prevalence of disabilities in women with UI age 70 years and older: 3.9% for ADLs, 7.1% for IADLs, 43.8% for mobility limitations, and 25.6% for functional limitations (difficulty stooping, crouching, or kneeling; lifting or carrying 10 pounds; and standing from an armless chair). The prevalence of all described functional limitations and disabilities with the exception of IADLs was higher in older women with UI compared to women without UI (p<0.01).

Given this high prevalence of both UI and functional limitations in the older women, the question arises whether there are common mechanistic pathways in their development and whether the presence of functional limitations in older women with UI would define UI is a geriatric syndrome in this population. Furthermore, the role of UI in the disability pathway has been mainly defined as a “passive or indirect” step to disability because UI negatively impacts quality of life, global well-being, life satisfaction, institutionalization, and may lead to death [8,33-35]. However, it has been suggested that UI has an “active” role in the development of disability as well [36].

UI and Mobility Limitations

There is emerging evidence for an association between UI and mobility limitations. A secondary database analysis of the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project revealed that approximately half of older women reported compromised mobility [37]. Women with daily UI were more likely to report not being physically active in the last month compared with women without UI (26.2% vs 14.3%, p<0.004). Women with daily UI were more likely to report falling at least once in the last 12 months compared to older women without UI (33.2% vs 22.6%, P = 0.046). Another report revealed that balance and gait impairments were significantly and independently associated with UUI (walking speed, lower versus higher quartile, odds ratio (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4-3.5); walking balance, unable versus able to do four tandem steps (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2-2.2), but not with SUI. The authors concluded that older women living at home had a strong association between limitation of motor and balance skills and UUI [38]. Jenkins et al. suggested a potential causal relationship between strength and lower body mobility and the development of UI. They found that decline in strength and body mobility predicted subsequent development of UI. The authors proposed that understanding the possible relationship between functional impairment in body mobility and UI is an important step towards developing appropriate interventions for the prevention, treatment, or management of urinary loss in older Americans [39]. Recently, Suskind et al. found that women aged 70 and older with a 5% or greater decrease in grip strength, an established marker of total muscle strength, had greater odds of new or persistent SUI, but not UUI [40]. Interestingly, body composition and muscle strength did not influence UUI, as only 5% or greater increase in walking speed was associated with new or persistent UUI over 3 years. Thus, this report is one of the most recent studies suggesting that body composition and muscle quality could be implicated in the mechanisms of developing SUI in older women.

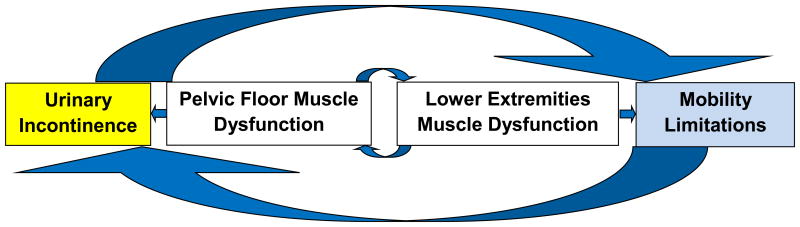

The relation between physical activity and UI has been suggested to be complex and bidirectional even in younger women [41]. UI in older women may contribute to the decline in mobility functioning during aging. Conversely, several reports have described the negative impact of mobility limitations on the increased risk of developing UI and the severity of UI symptoms [38,39]. This evidence highlights the potential bidirectional relationship between UI and mobility limitations. While the pathophysiology underlying UI and mobility limitations in aging women is largely unknown at present, the generalized dysfunction in the pelvic floor and lower body muscles (poor muscle quality) may play a significant role. The bidirectional relationship outlined in Figure 1 suggests mobility limitations could increase the risk of developing UI and exacerbate UI severity, while UI may contribute to greater mobility limitations, mediated by poor pelvic floor and lower extremity muscle quality highlighting that both UI and mobility limitations may have “active” roles in the development of each other (Figure 1). Increased high quality research in our understanding of UI and mobility limitations in older women is necessary to enhance our insight into clinical and rehabilitative interventions that will lead to improved measures for prevention and treatment of both UI and mobility limitations in older women. This information is critical and may be an integral component in the development of tailored intervention strategies for the prevention, treatment, and management of UI in older women.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of bidirectional relationship and the role of pelvic floor and lower extremities muscles in the development of urinary incontinence and mobility limitations in older women.

Proposed Conceptual Models for Understanding Relationships between UI and Disability

Coll-Planas et al highlighted that UI plays an “active” role in the development of disability [36]. The authors classified possible relations between UI and disability in the different pathways, including: 1) UI as a risk factor for functional decline and reduced physical activity through the increased risk of falls and fractures; 2) Functional decline and reduced physical activity as risk factors for the onset of UI; 3) Shared risk factors for UI and functional decline: white matter changes, stroke and other neurological conditions; 4) UI in a unifying conceptual framework: the multifactorial etiology of geriatric syndromes; 5) UI as an indicator of frailty. However, the authors also acknowledged that while geriatric research on UI has made significant progress, the mechanistic understanding of these pathways still remain limited. Given the previously stated possible bidirectional relationship between mobility limitations and UI, and later in life disability, further research into the mechanisms of bidirectional relationship between mobility limitations and UI mechanisms will help us to better prevent and treat mobility limitations and UI in older women, and eventually prevent or delay the development of disability. Despite unclear mechanisms, recent evidence supports the bidirectional relation between mobility limitations and UI in the first three conceptualized pathways [36]:

-

UI as a risk factor for functional decline and reduced physical activity through the increased risk of falls and fractures.

-

Functional decline and reduced physical activity as risk factors for the onset of UI.

-

UI and functional decline share common causes: white matter changes, stroke and other neurological conditions.

Further research to evaluate muscle dysfunction in lower extremities and pelvis in women with mobility limitations and UI will likely lead to better understanding of these pathways, and therefore, the development of evidence-based treatment of UI that are directed not at the bladder, but rather at non-urologic factors with non-urologic interventions to improve efficacy of current urologic treatments, such as medications or even surgeries. These measures could consist of diet, environmental interventions to decrease falls and fractures, multimodal strength and balance rehabilitation programs, treatment of modifiable cardio-cerebrovascular risk factors, and others. Eventually, better understanding of how functional impairments in multiple domains lead to UI and disability in a multifactorial unifying conceptual model of UI and disability (Figure 2), described by Coll-Planas, will allow us to define and differentiate UI as a disease and as a geriatric syndrome in older women with different treatment approaches.

Figure 2.

Multifactorial unifying conceptual model of UI and disability –(Coll-Planas et al). Functional limitations in multiple domains compromise the compensatory ability resulting in both UI and disability. Used with permission from Springer.

Summary/Conclusions

UI, mobility limitations, and disabilities are prevalent conditions with a significant negative impact on the lives of millions of older women. The relationship between UI and disability can be shown through different pathways. An improved understanding of these conditions and their associations can have substantial implications for both clinical work and research in this area. Further research and understanding of UI, mobility limitations, and disabilities in older women will enhance our insight into clinical, pharmacological, environmental, behavioral and rehabilitative interventions and will lead to improved measures for prevention and treatment of both conditions in older women. Early evidence suggests that mobility limitations and UI in older women may have bidirectional pathophysiology mechanisms through generalized muscle dysfunction.

Contributor Information

Tatiana V. Sanses, Division of Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

Bela Kudish, Urogynecology Center for Women, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Florida Hospital, Orlando, FL.

Jack M. Guralnik, Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

•Of importance

••Of major importance

- 1.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association. (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):4–20. doi: 10.1002/nau.20798. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Silay K, Akinci S, Ulas A, Yalcin A, Silay YS, Akinci MB, et al. Occult urinary Incontinence in elderly women and its association with geriatric condition. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(3):447–51. Demonstrates prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life and performance status in older women. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;114(6):1278–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5•.Lai HH, Shen Bk, Rawal A, Vetter J. The relationship between depression and overactive bladder/urinary incontinence symptoms in the clinical OAB population. BMC Urol. 2016;16(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0179-x. Describes positive correlation between the severity of urinary incontinence and depression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Aguilar-Navarro S, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Grados-Chavarria BH, Garcia-Lara JM, Amieva H, Avila-Funes JA. The severity of urinary incontinence decreases health-related quality of life among community-dwelling elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012 Nov;67(11):1266–71. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls152. Epub 2012 Aug 9. Describes the negative impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thom DH, Haan MN, Van den Eeden SK. Medically recognized urinary incontinence and risks of hospitalization, nursing home admission and mortality. Age Ageing. 1997 Sep;26(5):367–74. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.5.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm JMCP. 2014 Feb;20(2):130–40. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.130. Evaluates a significant economic impact from urinary incontinence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland HE. Incontinence in older women. JAMA. 2010 Jun 2;303(21):2172–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Minassian VA, Bazi T, Stewart WF. Clinical epidemiological insights into urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2017 Mar 20; doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3314-7. Summarizes recent knowledge in epidemiology and pathophysiology of urinary incontinence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urinary Incontinence in Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov-Dec;21(6):304–14. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000231. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavelle ES, Zyczynski HM. Stress Urinary Incontinence: Comparative Efficacy Trials. Reviews the highest-quality clinical trials comparing contemporary treatment options for women with SUI. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;43(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White N, Iglesia CB. Overactive Bladder. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;43(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2015.10.002. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Burgio KL, Markland AD. Urinary incontinence in older adults. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011 Jul-Aug;78(4):558–70. doi: 10.1002/msj.20276. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995 May 3;273(17):1348–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olde Rikkert MG, Rigaud AS, van Hoeyweghen RJ, de Graaf J. Geriatric syndromes: medial misnomer or progress in geriatrics? Neth J Med. 2003;611:83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:574–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20••.Rosso AL, Eaton CB, Wallace R, Gold R, Stefanick ML, Ockene JK, et al. Geriatric syndromes and incident disability in older women: results from the women's health initiative observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013 Mar;61(3):371–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12147. Describes geriatric syndromes and disability in older women. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1976 Fall;54(4):439–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Assessing the building blocks of function: utilizing measures of functional limitation. Am J Prev Med. 2003 Oct;25(3 Suppl 2):112–21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Disability in older adults: Evidence regarding significance, etiology, and risk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Jan;45(1):92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00986.x. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004 Mar;59(3):255–63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Jan;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leveille SG, Penninx BW, Melzer D, Izmirlian G, Guralnik JM. Sex Differences in the Prevalence of Mobility Disability in Old Age: The Dynamics of Incidence, Recovery, and Mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000 Jan;55(1):S41–50. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.1.s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci . Demography and Epidemiology. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Asthana S, High K, Studenski S, editors. Hazzard's Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Co.; 2009. pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-andsystems/Research/MCBS/Data-Tables-items/2011CharAndPerc.html?DLPage=1&DLSort=0&DLSortDir=descending

- 29•.Nieto ML, Kisby C, Matthews CA, Wu JM. The Evaluation of Baseline Physical Function and Cognition in Women Undergoing Pelvic Floor Surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016 Jan-Feb;22(1):51–4. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000223. Provides baseline functional status assessment in older women with pelvic floor disorders undergoing surgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Oliphant SS, Lowder JL, Lee MJ, Ghetti C. Most older women recover baseline functional status following pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2014 Oct;25(10):1425–32. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2394-x. Evaluates changes in functional status on older women with pelvic floor disorders undergoing surgery for prolapse. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Erekson EA, Fried TR, Martin DK, Rutherford TJ, Strohbehn K, Bynum JP. Frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability in older women with female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2015 Jun;26(6):823–30. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2596-2. Epub 2014 Dec 17. Evaluates frailty, cognition, and functional disability in older women with pelvic floor disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32••.Greer JA, Xu R, Propert KJ, Arya LA. Urinary incontinence and disability in community-dwelling women: a cross-sectional study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015 Aug;34(6):539–43. doi: 10.1002/nau.22615. Determines that low preoperative functional status is associated with longer hospital stay and postoperative complications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubeau CE, Simon SE, Morris JN. The effect of urinary incontinence on quality of life in older nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Sep;54(9):1325–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson TM, Kincade JE, Bernard SL, Busby-Whitehead J, Hertz-Picciotto I, DeFriese GH. The association of urinary incontinence with poor self-rated health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 Jun;46(6):693–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Mehta KM, Covinsky KE. Urinary incontinence and its association with death, nursing home admission, and functional decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52(5):712–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Coll-Planas L, Denkinger, Nikolaus T. Relationship of urinary incontinence and late-life disability: implications for clinical work and research in geriatrics. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2008 Aug;41(4):283–90. doi: 10.1007/s00391-008-0563-6. Epub 2008 Aug. Proposes the pathways in relationship between urinary incontinence and disability. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37••.Erekson EA, Ciarleglio MM, Hanissian PD, Strohbehn K, Bynum JP, Fried TR. Functional disability and compromised mobility among older women with urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015 May-Jun;21(3):170–5. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000136. Assesses functional disabilities, including mobility disabilities, in older women with urinary incontinence by using self-reported and objective measures of performance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38••.Fritel X, Lachal L, Cassou B, Fauconnier A, Dargent-Molina P. Mobility impairment is associated with urge but not stress urinary incontinence in community-dwelling older women: results from the Ossebo study. BJOG. 2013 Nov;120(12):1566–72. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12316. Epub 2013 Jun 10. Evaluates balance and gait impairments association with urgency urinary incontinence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenkins KR, Fultz NH. Functional impairment as a risk factor for urinary incontinence among older Americans. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(1):51–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40••.Suskind AM, Cawthon PM, Nakagawa S, Subak LL, Reinders S, Satterfield S, et al. Urinary incontinence in older women: the role of body composition and muscle strength: from the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Dec 5; doi: 10.1111/jgs.14545. [Epub ahead of print] Proposes that body composition and muscle quality is implicated in the development of stress urinary incontinence in older women. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Sung VW, Kassis N, Raker CA. Improvements in physical activity and functioning after undergoing midurethral sling procedure for urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):573–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318263a3db. Demonstrates that surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence improves physical activity levels and physical functioning in younger women. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]