Selective valorization of lignin to phenol is achieved by direct transformation of C–C and C–O bonds.

Abstract

Phenol is an important commodity chemical in the industry, which is currently produced using fossil feedstocks. Here, we report a strategy to produce phenol from lignin by directly deconstructing Csp2–Csp3 and C–O bonds under mild conditions. It was found that zeolite catalyst could efficiently catalyze both the direct Csp2–Csp3 bond breakage to remove propyl structure and aliphatic β carbon–oxygen (Cβ–O) bond hydrolysis to form OH group on the aromatic ring. The yield of phenol could reach 10.9 weight % with a selectivity of 91.8%. In this unique route, water was the only reactant besides lignin. A scale-up experiment showed that 4.1 g of pure phenol could be obtained from 50.0 g of lignin. The reaction pathway was proposed by a combination of control experiments and density functional theory studies. This work opens the way for producing phenol from lignin by direct transformation of Csp2–Csp3 and C–O bonds in lignin.

INTRODUCTION

Phenol is an important commodity chemical in the industry, with world production exceeding 11.5 megatons in 2019 (1, 2). The global phenol market is expected to grow continuously on the account of its commercial viability and rising demand for its extensive employment as organic chemical intermediate and raw chemical material for manufacturing various industrial products, particularly for phenolic resin, bisphenol A, nylon, cyclohexanol, epoxy, polycarbonate, pharmaceutical, etc. (3). In the industry, phenol is mainly produced from benzene via a multistep and indirect synthesis, namely, a cumene process that has several disadvantages, such as complicated and severe conditions, high consumption of energy and fossil raw chemicals, and serious environmental pollution (2, 4). Although direct hydroxylation of an aromatic ring (5, 6) is deemed as an operationally simple and environmentally benign process for producing phenol, the route is still dependent on fossil-derived benzene and limited by the overoxidation of phenol (4). Thus, more efficient and sustainable strategy, such as utilization of biomass as raw materials to economically produce phenol, is desired, which could liberate us from the reliance on fossil resource and is of great industrial and social significance (7).

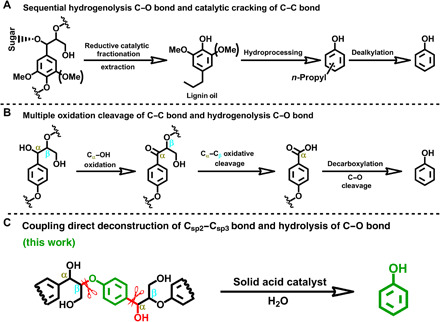

As the main constituent of lignocellulosic biomass, lignin is the most abundant renewable source composed of aromatic units in nature, which places a premium on strategies that pursue value-added aromatic chemicals from biomass (8–11). Synthesis of phenol using lignin is a promising route but is challenging. Recently, notable progresses have been achieved. Sels and co-workers (12) developed an integrated biorefinery process that converts 78 wt % (weight %) of birch into xylochemicals. In this process, the reductive catalytic fractionation of the wood initially produces a carbohydrate pulp amenable to bioethanol production and lignin oil. After extraction, the mixture of phenolic monomers in lignin oil is catalytically funneled into 20 wt % of phenol (based on lignin weight) by gas-phase hydroprocessing and dealkylation in sequence (Fig. 1A and detailed process shown in fig. S1A). Wang and co-workers (13) proposed a multistep methodology to produce phenol from lignin (Fig. 1B and detailed methodology shown in fig. S1B). In the first step, (Ar)Cα(OH)–Cβ structure in lignin is oxidized into Cα(═O)–Cβ intermediate. In the second step, (Ar)Cα(═O)–Cβ bond is oxidatively cleaved, and the (Ar)Cα(═O)–OH structure is formed. Last, aryl C–Cα (Csp2–Csp3) bond is deconstructed via decarboxylation. Together with the hydrogenolysis of the aliphatic β carbon–oxygen (Cβ–O) bond, the multistep oxidation strategy could yield a mixture of aromatics and phenol with a phenol selectivity of 60% (13).

Fig. 1. Sustainable routes for phenol production.

(A) The integrated biorefinery process for phenol production from wood (12). (B) Multistep oxidation-hydrogenolysis route for phenol from lignin, Cα, and Cβ are aliphatic α-C and β-C positions (13). (C) The route of this work for phenol production from lignin via coupling the direct deconstruction of Csp2–Csp3 bond and hydrolysis of aliphatic Cβ–O bond in H (p-hydroxyphenl) structure; Csp2–Csp3 is aryl C–Cα bond.

The development of a new route to produce phenol from lignin is still highly desirable, although some interesting works have been reported. We can propose from the representative H (p-hydroxyphenyl) structures in woody and herbaceous plants (fig. S2) that phenol can be efficiently obtained from lignin by directly deconstructing Csp2–Csp3 and aliphatic Cβ–O bonds, as illustrated in Fig. 1C. Up to now, extensive studies have been conducted on the cleavage of the C–O bond in lignin, and alkylphenols can be generated with the unbroken Csp2–Csp3 bonds (14–20). In this context, the efficient cleavage of the C–C bonds is the key for producing phenol from lignin. Csp2–Csp3 bond cleavage can be realized via dealkylation, dealkenylation, and reductive cleavage. Nevertheless, these existing strategies are still limited to harsh reaction conditions (12, 21–23). The cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bonds has usually been realized at above 400°C in the dealkylation process of the conventional biorefinery, which results in side reactions (12, 24). Thus, the cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bond at mild condition is necessary. Historically, the mild deconstruction of C–C bond has often been realized by coupling this process with simultaneous formation of other bonds, such as C–X (X = C, Si, N, O, S, F …) bond formation (25–30). The deconstructive functionalization method has limitation in lignin valorization because it involves multiple steps and has low atom economy (7). With these limitations in mind, the development of simple and effective methods for Csp2–Csp3 bond cleavage that facilitate the highly selective production of phenol from lignin remains a prominent goal and scientific challenge. Here, we report a mechanistically distinct and operationally concise strategy to produce phenol from lignin by direct deconstruction of the Csp2–Csp3 bond and hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O bond (Fig. 1C). This work provides an efficient and economical strategy for the selective valorization of lignin to phenol under mild conditions.

RESULTS

As discussed above, the cleavage of Csp2–Csp3 is crucial for the production of phenol from lignin. We commenced our investigations of the proposed deconstructive cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bond by evaluating a broad range of solid acid catalysts, supported catalysts, and mineral acids, using 4-(1-hydroxypropyl) phenol (1a) as the substrate (Table 1 and table S1) in water. After extensive screening of various conditions, we identified the optimized conditions shown in entry 1, which used cheap and environmentally benign HY30 zeolite (Si/Al = 30; fig. S3 and table S2) in H2O at 180°C for 1 hour (fig. S4), affording 94.6% yield of phenol (1b) at full conversion of 1a (fig. S5). The reaction did not occur without a catalyst (entry 2). It is well-known that the HY3 zeolite has its physique of Al-rich framework (31). However, most of the acid sites, especially the strong acid sites, are embedded deeply within the microporous framework that is difficult for the reactants to access and the reaction cannot occur (entry 3 of Table 1 for HY3). After the isomorphic substitution of framework aluminum by silicon, the high-silica Y zeolites, such as HY15, HY30, and HY40, have more mesoporous structures (fig. S3J and table S2), which allows the reactants to diffuse freely to the exposed strong acid sites (24). However, in contrast with HY30 and HY40 zeolites, HY15 has less mesoporous structures and lower concentration of strong acid sites (table S2), consequently leading to its lower yield of 1b under the same conditions (entry 3 of Table 1 for HY15). HY30 and HY40 zeolites have higher concentration of strong acid sites exposed in the mesoporous channels (table S2), affording them higher yields of 1b (entries 1 and 3 of Table 1). However, the acid sites of HY40 zeolite are less than that of HY30 (table S2), and thus, the catalytic performance of HY30 was better than the HY40 zeolite. Other types of zeolites such as ZSM-5, mordenite, beta, and MCM-41 could not promote the reaction effectively under such conditions (entries 4 to 7). The supported catalysts were not active for the reaction (entries 8 to 10). Only SO42−/ZrO2 catalyst could produce little product (entry 10). In addition, heteropoly and mineral acids gave no yield of 1b (entries 11 and 12). The above results indicate that the HY30 zeolite showed outstanding performance for catalyzing the reaction, over which the reaction could proceed at mild temperature (180°C) efficiently.

Table 1. Screening of catalysts for direct deconstruction of Csp2–Csp3 bond.

Standard conditions: 4-(1-hydroxypropyl) phenol (1a; 1 mmol), catalyst (0.3 g), H2O (4.0 ml), 180°C, 1 hour, 0.5 MPa of Ar, and 800 rpm. All reaction results are the averages of three experiments conducted in parallel.

| Entry | Catalyst variation | Yield/% |

| 1 | Zeolite HY30 | 94.6 |

| 2 | Noncatalyst | 0 |

| 3 | Zeolite HY3, HY15, and HY40 |

0, 8.7, 51.9 |

| 4 | Zeolite ZSM-59, ZSM-530, ZSM-563, and ZSM-5235 |

0, 0, 0, 11.3 |

| 5 | Zeolite mordenite10 and mordenite13 |

0, 0 |

| 6 | Zeolite beta13, beta30, and beta50 | 0, 0, 0 |

| 7 | Zeolite MCM-41 | 0 |

| 8 | Ru/SiO2, Ni/SiO2, and W/SiO2 |

0, 0, 0 |

| 9 |

and WO3/ ZrO2 |

5.3, 0 |

| 10 | WO3/AI2O3 and Nb2O5/AI2O3 |

0, 0 |

| 11 | Heteropoly acid | 0 |

| 12 | HCI, H2SO4, and H3PO4 |

0, 0, 0 |

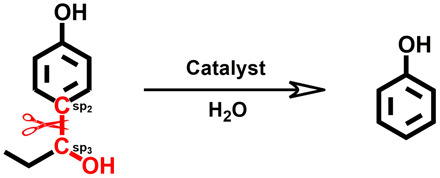

With the optimized conditions established, we studied the production of phenol from lignin (Fig. 2A, fig. S6, and table S3). As shown in Fig. 2A, 10.9 wt % yield of phenol was obtained from poplar lignin with a selectivity of 91.8% (based on lignin). In addition, small amount of 4-methylphenol (0.25 wt %), 2-methoxyphenol (0.40 wt %), and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (0.33 wt %) were formed. It can be reasonably inferred that 4-methylphenol was generated from the weak transmethylation of the produced phenol using methyl in the methoxy group (32). In comparison, the reaction of the lignin was also performed without the catalyst under the same conditions, which could not yield any low–molecular weight products (fig. S6E). These results highlighted the deconstructive strategy for the Csp2–Csp3 bonds in the H-, G (guaiacyl)–, and S (syringyl)–derived building blocks (fig. S7) (33, 34), establishing lignin as a renewable source for phenol. Notably, the scission of Csp2–Csp3 bonds in G and S units is more difficult due to the steric and electronic effects, which restrained the respective formation of 2-methoxyphenol and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol and afforded the high selectivity of phenol (13). We also performed the transformations of the lignins extracted from other woods, including pine, willow, and cypress, and herbaceous plant Phyllostachys pubescens (fig. S8). The yields of phenol were, respectively, 9.0, 6.3, 4.5, and 10.1% (based on lignin) with high selectivities. To get pure phenol, we conducted a scale-up experiment for the transformation of the poplar lignin (fig. S9), which produced 4.1 g of pure phenol from 50.0 g of lignin. The yield of phenol was slightly reduced comparing with the gas chromatography (GC) result mainly because of the loss in the separation process. To further prove the effectiveness of the catalyst, we studied the reactions of some lignin model compounds, and the results was summarized in Fig. 2B. The Csp2–Csp3 bond in H-derived (1a, 2a, and 3a), G-derived (4a, 5a, and 6a), and S-derived (7a, 8a, and 9a) model compounds could be efficiently cleaved, confirming the practicality of this strategy on the scission of the Csp2–Csp3 bond. Besides, the products from the dimeric lignin model compounds (3a, 6a, and 9a) also showed that phenolic hydroxyl (–OH) could be formed by the hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O bond, which is consistent with the conclusion that solid acid catalyst could promote the hydrolysis efficiently (35). The results further indicate that the protocol to produce phenol from lignin proposed in this work (Fig. 1C) is feasible.

Fig. 2. Deconstruction of lignin and lignin model compounds.

(A) Deconstruction of poplar lignin. Reaction conditions are the following: lignin (0.4 g), HY30 (0.4 g), H2O (5.0 ml), 200°C, 3 hours, 0.5 MPa of Ar, and 800 rpm. (B) Deconstruction of the representative lignin model compounds. Reaction conditions are the following: substrate (1 mmol), HY30 zeolite (0.3 g), H2O (4.0 ml), 180°C, 1 hour, 0.5 MPa of Ar, and 800 rpm. All reaction results in (A) and (B) are the averages of the three experiments conducted in parallel.

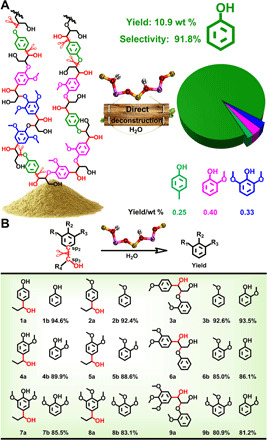

The deconstructive strategy for the Csp2–Csp3 bonds in lignin and its model compounds may be attributed to the labile chemical environment at the aliphatic Cα position with hydroxyl substituent. As a further recognition of this deconstructive strategy, we also considered diverse Csp2–Csp3 bonds with various chemical environments at the Cα position, which continued to study the versatility of the catalyst for cleaving robust C–C bonds. As shown in Fig. 3, a variety of alkyl substitution patterns, together with hydroxyl group (10a to 15a) at the Cα position [Csp2–Csp3(OH)R], were also tolerated, and the corresponding cleavage products (10b to 15b) were obtained in moderate to good yields (70 to 95%). The deconstructive efficiency was nearly equal to that of 1a when the hydrogen at the Cα position is replaced by CH3 (16a), with 95.0% yield of anisole (16b). The derivative of 1a without a substituent on benzene ring (17a) could likewise afford the deconstructive product 17b in a yield of 92.7%. When the hydroxyl group in 1a is isomerized at the aliphatic Cβ position (18a), the Csp2–Csp3 bond could also be deconstructed, but the reactivity was lower with a yield of 31.1% (18b). Furthermore, in several structurally and electronically distinct Cα-substituted (Csp2–Csp3X) bonds, including those bearing halogen (19a and 20a), ester (21a and 22a), and alkenyl (23a and 24a) groups, the Csp2–Csp3 bond could also be cleaved, but the efficiencies were relatively lower (19b to 24b) than that with hydroxyl group (1a). In comparison, p-hydroxybenzoic acid (25a) underwent decarboxylation to provide phenol (25b) in 90.6% yield, demonstrating that the deconstruction of the Csp2–Csp2 bond with the carbonyl environment at the Cα position [Csp2–Csp2(═O)OR] could be efficiently accessed by this strategy. Given the aforementioned cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bond with various Cα environments, the virtue of this strategy is evident in the deconstruction of Csp2–Csp3 bonds with the hydroxyl group at the Cα position, which is favorable to the transformation Csp2–Csp3 bond in lignin structure.

Fig. 3. Direct deconstruction of the Csp2–Csp3 bond with various bonding environments at the aliphatic Cα position.

Reaction results are the averages of three experiments conducted in parallel. Reaction conditions are the following: substrate (1 mmol), HY30 (0.3 g), H2O (4.0 ml), 180°C, 1 hour, 0.5 MPa of Ar, and 800 rpm. *Bzl, benzyl group; †Ac, acetyl group; ‡Bz, benzoyl group.

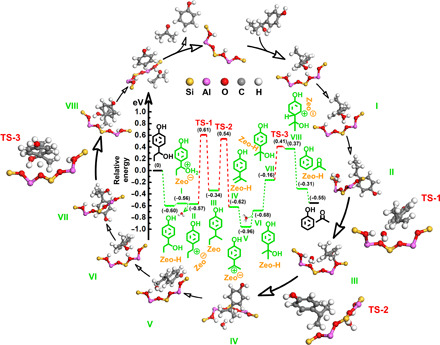

It is very interesting to study the reaction pathway for the transformation of lignin to phenol. As discussed above, the reaction involves the hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O group to the OH group and the direct cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bond (Fig. 1C). The pathway for the hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O bond over acidic catalyst is well known (35). Thus, in this work, we focus on studying the mechanism for transformation of the Csp2–Csp3 bond. We envisioned the deconstructive strategy to proceed via a stepwise protonated dehydroxylation, γ-methyl shift, and Csp2–Csp3 bond β scission pathway. To get more insight into the reaction mechanism, we performed density functional theory (DFT) studies of the reaction over the HY30 zeolite. The calculated reaction profile is shown in Fig. 4. The Cα hydroxyl group is initially protonated on a Bronsted acid site of HY30, leading to the formation of oxonium ion (structure I), which then transforms into a carbonium ion (structure II) with the elimination of H2O. Thermodynamically, γ-methyl on the side chain is then shifted to the aliphatic Cα position by the function of zeolite, evolving to the chemically adsorbed structure III with a migration barrier of 1.18 eV (TS-1), and subsequent proton abstraction by zeolite delivers structure IV in a lower barrier of 0.88 eV (TS-2). The structure IV then undergoes a second protonation at the Cα position to form carbonium ion V (structure V), and this would be pursued by the trap of H2O, which gives tertiary alcohol geometry (structure VI) and concurrently accomplishes another proton rejuvenation of the Bronsted acid site. Afterward, endothermically turning the benzene ring of the tertiary alcohol (structure VI) toward the Bronsted acid site gives the appropriate geometry (structure VII) to enable the protonation of the Csp2 position (structure VIII) with an effective barrier of 0.57 eV (TS-3). The resulting carbonium ion VIII undergoes desired Csp2–Csp3 bond β scission to exothermically generate phenol and acetone (21).

Fig. 4. Mechanistic studies.

Energy profile for the direct deconstruction of the Csp2–Csp3 bond on the HY30 catalyst. Reaction intermediates (I to VIII) and transition state (TS, 1 to 3). Zeo, HY30 zeolite.

In support of the mechanism, an isotope labeling test of 1a in H218O was conducted (fig. S10), and the molecular weight of propanone was 60, namely, propan-2-(18O)1 was generated, confirming that the deconstruction strategy proceeded initially with the facile dehydroxylation process but then hydroxylation again at the aliphatic Cα position using a molecule of water. During the optimization studies (fig. S4), we also found that the conversion of 1a was increased more quickly than the yield of phenol, indicating that the γ-methyl shift is the rate-determining step for the deconstruction of Csp2–Csp3 bond, which is consistent with the DFT mechanism studies.

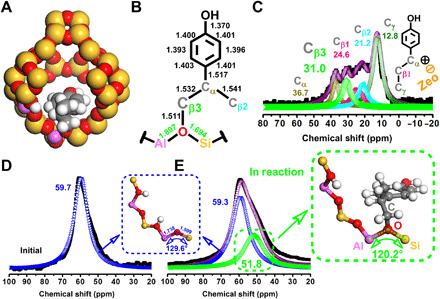

Notably, highly active nature and chemical accessibility of zeolite framework enabled the chemical bonding of the aliphatic C atom on the side chain to the Bronsted acid sites during the activation of the γ-methyl C atom (Cγ), which could be illustrated by the space-filling model (Fig. 5A) and core bond metrics (Fig. 5B) of the aforementioned structure III (Fig. 4), essentially affording the γ-methyl shift (36, 37). To further find the fate of aliphatic γ-methyl, the reaction of 1a was stopped after 10 min and subjected to 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis (Fig. 5C, fig. S11, and table S4). Although the 13C NMR signal for the Cγ atom could still be detected, we also observed a new resonance signal at 31.0 ppm (parts per million), together with the 24.6 and 21.2 ppm signals for the original β1–C and β2–C atoms (Cβ1 and Cβ2), which should be assigned to the Cβ3 atom shifted from the Cγ atom in reaction (38). The above resolved signals for all the Cβ atoms during the γ-methyl shift were further supported by the solid-state two-dimensional (2D) 13C{1H} dipolar-mediated heteronuclear correlation (HETCOR) NMR analysis (fig. S12 and table S5). Specifically, 13C signals associated with the original Cβ1 and Cβ2 atoms at 24.5 and 21.0 ppm are strongly correlated with the 1H signals at 1.5 and 1.9 ppm that should be associated with (–Cβ1H2–) and (–Cβ2H3) moieties in the intermediates II and III, respectively. The observed 13C and 1H signals at 12.7 and 0.7 ppm are assigned to the (–CγH3) moiety in the intermediate II. In accordance with the 13C NMR analysis (Fig. 5C), 2D 13C{1H} HETCOR NMR yields a well-resolved correlated signal at 31.2 ppm in the 13C dimension and at 2.0 ppm in the 1H dimension, which, again, reflects the transferred Cγ, namely, Cβ3 atom from the (–Cβ3H2-Zeo) moiety in the intermediate III. In particular, the chemical bonding with the oxygen atom in the framework [≡Al–O–Si≡] unit is believed to provide an inductive effect for the Cβ3 atom, which shifted its resonance downfield from that of the original Cβ1 and Cβ2 atoms, supporting the zeolite-catalyzed mechanism of the γ-methyl shift (39, 40). Such an intermediate [≡Al–O(Cβ3)–Si≡] unit referring to the new Cβ3 atom and zeolite oxygen atom was also validated by 27Al NMR and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses (Fig. 5, D and E, and fig. S14). As the tailor of the framework acidity, tetrahedrally coordinated Al [Al(IV)] in the framework of the initial and boiled zeolites always appears a single resonance at ca. 59.7 ppm (Fig. 5D and fig. S14A) (41). A shoulder resonance signal at ca. 51.8 ppm was identified in the operating zeolite, which could be assigned to the Al(IV) atom in the distorted [≡Al–O(Cβ3)–Si≡] environments (Fig. 5E). The charge compensation of the Cβ3 atom weakens the inductive effect of O atom from the neighboring Al(IV) atom, which reduces Al–O–Si bond angle and lengthened Al–O and Si–O bonds, shifting the resonance upfield from that of the Al(IV) atom in the regular [≡Al–O–Si≡] environments (42–44). In the FTIR spectra (fig. S14B), the intensity of the Bronsted acidic group [≡Al–OH–Si≡] at 3630 cm−1 decreased evidently for the zeolite in the reaction (45), and concomitantly, a measurable redshift in the infrared frequency was detected with respect to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the lattice cell [≡Al–O–Si≡], which should also be due to the lengthened Al–O and Si–O bonds caused by the interaction between the zeolite oxygen atoms in the framework [≡Al–O–Si≡] units and Cβ3 atoms (46), corresponding well with the 27Al NMR analysis. The above identifications are in excellent agreement with the DFT mechanism studies (Fig. 4) in which γ-methyl shift is proposed as the crucial step for the formation of the tertiary alcohol geometry (structure VI) that benefits the ultimate Csp2–Csp3 bond β scission (TS-3; 0.57 eV). By comparison, when the γ-methyl is replaced by H atom in the structural formula, the scission of the Csp2–Csp3 bond in 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethanol (Fig. 3, 10a) could also proceed via the protonation of the Csp2 position in the primary alcohol geometry, but a higher energy barrier of 0.72 eV (fig. S14) kinetically reduced the efficiency of the Csp2–Csp3 bond cleavage, agreeing well with the experimental result.

Fig. 5. Structural analysis of the C–C bond evolution in reaction of 1a.

(A) Space-filling model of structure III in Fig. 3. (B) Core bond metrics of structure III. (C) 13C NMR spectrum of the intermediates in the reaction of 1a; black solid square (■) represents the observed intensities; purple circle marks (○) is the total fitting curve; dark yellow regular triangle upward (△), pink regular triangle downward (▽), cyan hollow left triangle (◁), green diamond (◊), and olive hollow left triangle (▷) represent the fitting curves of Cα, Cβ1, Cβ2, Cβ3, and Cγ, respectively. (D) 27Al NMR spectrum of the initial HY30 zeolite; black solid square (■) represents the observed intensities; blue inverted triangle (▽) is the fitting curve of framework Al(IV). (E) 27Al NMR spectrum of the HY30 zeolite in reaction; black solid square (■) represents the observed intensities; purple circle marks (○) is the total fitting curve; blue inverted triangle (▽) and green yellow regular triangle (△) are the fitting curves of regular framework Al(IV) and Al(IV) bonding with Cβ2, respectively. Reaction conditions are the following: 1a (1 mmol), HY30 (0.3 g), H2O (4.0 ml), 180°C, 10 min, 0.5 MPa of Ar, and 800 rpm.

In the 13C NMR analyses (Fig. 5C, figs. S11A and S12A, and tables S4 and S5), the resonance signal for the aliphatic Cα atom in 1a at 73.9 ppm disappeared and shifted to 36.7 ppm, which verified that the hydroxyl group at the aliphatic Cα position could be protonated and eliminated rapidly in the reaction, agreeing with the DFT studies. It can be deduced that the labile chemistry of the hydroxyl group at the aliphatic Cα position [Csp2–Csp3(OH)] is the trigger for the efficient scission of the Csp2–Csp3 bond under such mild conditions, which facilitated the simultaneous deconstruction of the Csp2–Csp3 bonds and hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O bonds and eventually realized the direct abstraction of phenol from lignin structure (fig. S6, A and B). By contrast, during the conventional chemistry funnel processes (Fig. 1A), the cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bonds in the lignin oil–derived alkylphenols without hydroxyl group at the Cα position always required much higher reaction temperature (12). In the H-derived building blocks (figs. S7 and S15), the aliphatic Cα positions always have substituted hydroxyl groups (33, 47), which consequently provides the opportunity for direct deconstruction of the kinetically inert C–C bond under mild conditions for valorizing lignin into phenol. In addition, on the basis of the quantitative 13C analysis (fig. S15B), the amount of H-derived building blocks per 100 aromatic units in the extracted poplar lignin was 3.0 in the form of p-hydroxybenzoate (PB) unit. After the reaction, the 13C NMR signals for all the H-derived building blocks, including the PB units, disappeared in the lignin residue (fig. S15C), which corroborated the phenol production.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we developed a protocol to produce phenol from lignin by direct transformation of Csp2–Csp3 and C–O bonds under mild conditions, which was achieved by direct cleavage of Csp2–Csp3 bond to remove the propyl structure and hydrolysis of the aliphatic Cβ–O bond to form an OH group on the aromatic ring, and HY30 zeolite showed an outstanding catalytic performance for transformation of the both bonds. The yield of phenol could reach 10.9 wt % at optimized conditions on lignin basis, and the selectivity to phenol was as high as 91.8%. The scale-up experiment demonstrated that 4.1 g of pure phenol was obtained from 50.0 g of lignin. The experimental results and DFT calculations indicated that the chemical environment at the Cα position of the aliphatic chain was critical for the success of the strategy, and the Csp2–Csp3 bond was deconstructed via a dehydroxylation, γ-methyl shift, and C–C β scission pathway. This work opens an advanced approach and provides a sustainable route to obtain phenol from lignin. We anticipate that the scientific discovery is instructive for the exploration and valorization of biomass resources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

4′-Methoxypropiophenone (99%), 4′-methoxyacetophenone (99%), 3′,4′-dimethoxyacetophenone (98+%), 3′,4′,5′-trimethoxyacetophenone (99%), 4′-methoxybutyrophenone (97%), 4-methoxyphenylacetone (97+%), 4-methoxybenzaldehyde (98%), 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (98%), 3,4-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (99%), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde (99%), 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde (98%), 4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (97%), 2-methoxyphenol (98+%), bromoethane (98%), 1-bromohexane (99%), 1-bromododecane (98%), 2-phenylethyl bromide (98%), 1-bromo-3-phenylpropane (98%), (±)-1-phenyl-1-propanol (98+%), magnesium turnings (99+%), 4-n-propylphenol (98%), benzoyl chloride (99+%), thionyl chloride (99+%), phosphorus tribromide (99%), triethylamine (99+%), mordenite10 ammonium zeolite, aluminum oxide (99.5%), silicon dioxide (99.5%), ruthenium(III) chloride (anhydrous; Ru 47.7%), nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (98%), zirconium dichloride oxide octahydrate (98%), niobium(V) oxide (99.5%), chromium(III) acetylacetonate (97%), oxalic acid dehydrate (98%), and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (99%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. HY3 (Si/Al = 3), HY15, HY30, and HY40 were synthesized by Alfa Aesar. Ammonium hydroxide solution (28 to 30%), methylmagnesium chloride solution (3.0 M in tetrahydrofuran), and dimethyl sulfate (99%) were purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science and Technology Co. Ltd. Ammonium metatungstate hydrate (99.9%) was purchased from Strem Chemicals. 1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-propene was purchased from Ark Pharm Inc. 1-Methoxy-4-(1-propen-2-yl)benzene was obtained from Accela ChemBio Co. Ltd. ZSM-59, ZSM-530, ZSM-563, ZSM-5235, mordenite13, beta13, beta30, beta50, and MCM-41 zeolites were purchased from Nankai University Catalyst Co. Ltd. Silicotungstic acid, phosphotungstic acid, phosphomolybdic acid, hydrochloric acid (37%), sulfuric acid (98%), phosphoric acid (85%), acetic anhydride (98.5%), sodium borohydride (98%), bromine (99.5%), aluminum chloride (99%), and formaldehyde solution (37%) were provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Sodium chloride (99.5%), magnesium sulfate (99.5%), ammonium chloride (99.5%), sodium hydrogen carbonate (99.8%), and potassium carbonate (99%) were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagent Company. Poplar, pine, willow, and cypress were obtained from Gansu Province, China. P. pubescens was obtained from Jiangxi Province, China. Tetrahydrofuran (99.5%), ethyl acetate (99.5%), ethanol (99.5%), pyridine (99.5%), ether (99.5%), and acetone (99.5%) were purchased from Concord Technologies (Tianjin) Co. Ltd. Methylsulfoxide-d6 [D; 99.9%, 0.03% (v/v) tetramethylsilane (TMS)] was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. N2 (>99.99%), Ar (>99.99%), H2/Ar (H2, 10%; 99.99%), and O2/Ar (O2, 1%; 99.99%) were provided by Beijing Analytic Instrument Company. Deionized water was provided by the Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All reagents were used as received without further purification.

Catalyst preparation

Zeolite catalysts

HY3, HY15, HY30, HY40, ZSM-59, ZSM-530, ZSM-563, ZSM-5235, mordenite10 ammonium, mordenite13, beta13, beta30, beta50, and MCM-41 were pretreated by calcination at 550°C for 4 hours.

Ru/SiO2, Ni/SiO2, and W/SiO2 catalysts

Supported Ru/SiO2, Ni/SiO2, and W/SiO2 catalysts were prepared by commonly used wet impregnation method. In a typical preparation, SiO2 was dried at 120°C overnight before the impregnation. Ruthenium(III) chloride (0.103 g), nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (0.248 g), and ammonium metatungstate hydrate (0.067 g) were dissolved in 10 ml of deionized water separately. We describe the procedures, taking Ru/SiO2 as the example. The precursor solution was successively added dropwise to 30 ml of deionized water with 1 g of amorphous SiO2 at room temperature. The obtained mixture was vigorously stirred for 24 hours, evaporated under vacuum, and dried at 200°C for 12 hours in an oven. The as-prepared sample was reduced in a continuous 10% H2/Ar flow at 350°C for 1 hour. After being cooled to room temperature under Ar atmosphere, the reduced catalyst was exposed to 1% O2/Ar atmosphere for 1 hour to form a passivation layer to prohibit against bulk oxidation before exposure to air. Supported Ni/SiO2 and W/SiO2 catalysts were prepared by the same procedures for preparing the Ru/SiO2 catalyst. The prepared catalysts were denoted as Ru/SiO2, Ni/SiO2, and W/SiO2 catalysts.

SO2−4/ZrO2 catalyst

Zirconium hydroxide was prepared by the addition of an ammonium hydroxide solution into the aqueous solution of zirconium dichloride oxide octahydrate. The precipitation occurred with a pH value up to 10. Then, the gel was continually stirred for 2 hours at room temperature. After that, the gel was filtered, washed with deionized water, and then dried at 120°C for 16 hours.

Supported SO2–4/ZrO2 catalyst

In the experiment, 15 ml of 0.05 M−1 sulfuric acid solution was successively added dropwise to 30 ml of deionized water with 1 g of the obtained zirconium hydroxide at room temperature. The obtained mixture was vigorously stirred for 24 hours, evaporated under vacuum, and dried at 120°C for 12 hours in an oven. Last, the sample was calcined under an air flow at 550°C for 2 hours. The prepared catalyst was denoted as SO2–4/ZrO2 catalyst.

WO3/ZrO2 catalyst

Ammonium metatungstate hydrate (0.201 g) was dissolved in 10 ml of deionized water. Then, the precursor solution was successively added dropwise into 30 ml of deionized water with 1 g of the obtained zirconium hydroxide at room temperature. The obtained mixture was vigorously stirred for 24 hours, evaporated under vacuum, and dried at 120°C for 12 hours in an oven. Last, the sample was calcined under an air flow at 600°C for 3 hours. The prepared catalyst was denoted as WO3/ZrO2 catalyst.

WO3/Al2O3 catalyst

Ammonium metatungstate hydrate (0.201 g) was dissolved in 10 ml of deionized water. Then, the precursor solution was successively added dropwise to 30 ml of deionized water with 1 g of aluminum oxide at 60°C. The obtained mixture was vigorously stirred for 24 hours, evaporated under vacuum, and dried at 120°C for 12 hours in an oven. Last, the sample was calcined under air atmosphere at 600°C for 3 hours. The prepared catalyst was denoted as WO3/Al2O3 catalyst.

Nb2O5/Al2O3 catalyst

Supported Nb2O5/Al2O3 catalyst was prepared by commonly used wet impregnation method. Niobic acid (0.3 g) was dissolved in 10 ml of oxalic acid aqueous solution. Then, the precursor solution was successively added dropwise into 30 ml of deionized water with 1 g of aluminum oxide at room temperature. The obtained mixture was vigorously stirred for 24 hours, evaporated under vacuum, and dried at 120°C for 12 hours in an oven. Last, the sample was calcined under an air flow at 500°C for 3 hours. The prepared catalyst was denoted as Nb2O5/Al2O3 catalyst.

Catalyst characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples were obtained on a Rigaku D/max 2500 x-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα x-ray source radiation and operated at 40 kV and 200 mA. The 2θ range was scanned from 15° to 40° at a speed of 2°/min with a step width of 0.02°.

The analysis of temperature-programmed ammonia desorption (NH3-TPD) was performed on an AutoChem 2950 HP analyzer. All the samples were heated to 400°C at a rate of 10°C min−1 and maintained at 400°C for 1 hour. The adsorption of ammonia on the samples was performed at room temperature. After saturation, the samples were purged in a flowing pure nitrogen at 100°C for 1 hour to eliminate the physically adsorbed ammonia. Then, the NH3-TPD profiles were obtained in the range of 50° to 600°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1.

FTIR spectroscopy measurement was conducted using a Bruker TENSOR-27 FTIR instrument with a resolution of 2 cm−1, a spectral range from 400 to 4000 cm−1, and 128 scans for each sample. The spectral resolution of the spectrometer is 0.125 cm−1. The FTIR of pyridine adsorption was measured using a Nicolet Avatar 360 FTIR equipped with a vacuum cell. The samples are pressed into wafers and activated under vacuum at 500°C for 2 hours. After cooling the sample to room temperature, pyridine was injected in the cell and then treated under vacuum for 60 min at 100°C. The spectra were recorded after pyridine adsorption-desorption at 200° and 350°C, with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 in the region from 1400 to 3800 cm−1. The amount of acid sites in the samples was calculated according to the equations in (48).

29Si and 27Al magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance III 400-MHz spectrometer with a resonance probe of 4 mm. The 29Si MAS NMR spectra were recorded at a resonance frequency of 79.30 MHz, with 1.5 μs of pulse width, 2 s of delay time, and a spinning speed of 8 kHz with 2500 scans. 27Al MAS NMR spectra were recorded at a resonance frequency of 104.01 MHz, with 1 μs of pulse width, 0.5 s of delay time, and a spinning speed of 12 kHz with 8192 scans.

N2 adsorption-desorption experiments were conducted using a Micromeritics TriStar II 3020 at liquid nitrogen temperature. The sample was degassed at 300°C under vacuum for 24 hours before analysis. The micropore/mesopore surface areas were calculated using the t-plot model. The pore size distribution of the sample was calculated using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size model. The micropore/mesopore volumes were calculated using the t-plot and BJH models, respectively.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using an SEM S-4800 operating at 10 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using a TEM HT7700 operating at 100 kV. The contents of the supported metals on the catalysts were determined by inductively coupled plasma (Thermo Fisher Scientific, iCAP Q).

Lignin extraction and characterization

The extraction of lignin was performed using the method similar to that reported in (49). A 1-liter autoclave (Weihai Xinyuan Chemical Machinery Co. Ltd.) was used. In a typical experiment, 70 g of poplar powder, 490 ml of acetone, and 210 ml of water were loaded into the autoclave. The autoclave was sealed and purged with N2 to remove the air at room temperature and subsequently charged with 0.5 MPa of N2. Then, the autoclave was heated to 160°C within 1 hour. After that, the stirrer was started with a stirring speed of 600 rpm, and the reaction time was recorded. After 1 hour, the autoclave was cooled down quickly, and the gas was released. The liquid was collected by a filtration process. The filter residue was washed three times with 200 ml of acetone/H2O (9:1), and the washing liquor was collected and combined with the filtrate liquid. After that, the liquid was concentrated under vacuum at 30°C until the liquid became muddy and then dissolved again by 30 ml of acetone. Then, the concentrated lignin solution was slowly poured into rapidly stirred 2000 ml of water, and the precipitate was filtered using a funnel with a pore size of 3 to 4 μm. Then, the crude lignin was dissolved by 150 ml of acetone/H2O (9:1) and then precipitated into water again in the same way. Last, the crude lignin was dissolved by 200 ml of solution of acetone/methanol (9:1) and dried by anhydrous MgSO4. The liquid was then slowly poured into rapidly stirred 2000 ml of diethyl ether and filtered using a funnel with a pore size of 3 to 4 μm. The lignin solid was freeze-dried under vacuum for 24 hours, and 3.1 g of poplar lignin was lastly obtained. The obtained lignin was dissolved in 550 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–d6 and characterized by 1H/13C 2D heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR and quantitative 13C NMR analyses using Bruker Avance III 500WB and Bruker Avance 600, as described by other researchers (33). For the quantitative 13C NMR analysis, chromium(III) acetylacetonate was used as the relaxation reagent.

Synthesis of the model compounds

1H NMR and 13C NMR analyses were performed on a Bruker Avance III 400 HD using DMSO-d6 as the solvent. 1H chemical shifts were referenced to TMS at 0 ppm, and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to DMSO-d6 at 39.6 ppm. Multiplicities are described using the following abbreviations: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; and m, multiplet. The details of the methods and procedures for the syntheses of the model compounds are described in Supplementary Text.

Catalytic performance

The reactions were carried out in a Teflon-lined stainless steel reactor of 20 ml with a magnetic stirrer. In a typical experiment, a suitable amount of reactant, catalyst, and water were loaded into the reactor. The reactor was sealed and purged with Ar three times to remove the air at room temperature and subsequently charged with 0.5 MPa of Ar. Then, the reactor was placed in a furnace at the desired reaction temperature. Then, the stirrer was started with a stirring speed of 800 rpm, and the reaction time was recorded. After the reaction, the reactor was placed in ice water, and the gas was released, passing through the ethyl acetate. The reaction mixture in the reactor was transferred into a centrifuge tube. Then, the reactor was washed with the ethyl acetate used for the gas filtration, which was lastly combined with the reaction mixture. After centrifugation, the catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture. The quantitative analysis of the liquid products in the organic phase was conducted using a GC (Agilent 6820) equipped with a flame ionization detector and HP-5ms capillary column (0.25 mm in diameter and 30 m in length). Identification of the products and reactant was performed using a GC–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system [Agilent 5977A, HP-5ms capillary column (0.25 m in diameter and 30 m in length)] and by comparing the retention time to the respective standards in GC traces. Biphenyl was used as the internal standard to determine the conversions of substrates, selectivities, and yields of the products. The carbon balance for the transformation of the model compounds was calculated using Caromatics balances, which was given relative to the aromatic products (50). The Caromatics balances for the transformation of the model compounds were larger than 95%. Mass balance for the lignin transformation was calculated using Eq. 1 (35). After the reaction, solid and liquid were separated by centrifugation, and the mass of the solid recovered was nearly the same as that of the catalyst charged. For the lignin transformation, internal standard (biphenyl for the organic phase) was used to determine the yields of the detectable products. After the recovery of the catalyst, the liquid reaction mixtures were subjected to a rotavap to remove the solvents and the volatile products. Then, the recovered residual solid was freeze-dried under vacuum for 24 hours. For the transformation of the lignin catalyzed by HY30 zeolite, the mass balance was 90 ± 5%. The structure of the lignin and the recovered residual solid were analyzed by 1H/13C 2D HSQC NMR and quantitative 13C NMR spectroscopy (Bruker Avance III 600 HD)

| (1) |

Recycling of catalyst

The reusability of the HY30 zeolite was tested using the reaction of 1a model compound. After the reaction, the reaction mixture in the reactor was transferred into a centrifuge tube. Then, the reactor was washed with ethyl acetate, which was lastly combined with the reaction mixture. After centrifugation, the used HY30 zeolite was separated from the reaction mixture and successively washed with ethanol (5 × 10 ml) and water (5 × 10 ml). Then, the recovered zeolite was dried at 120°C for 2 hours and subsequently calcined at 550°C for 4 hours. After the calcination, the recycled zeolite was reused directly for the next run.

Scale-up transformation of poplar lignin

The scale-up reaction was performed in 1-liter autoclave (Weihai Xinyuan Chemical Machinery Co. Ltd.). In the reaction, 50.0 g of lignin, 50.0 g of HY30, and 600 ml of H2O were added into the autoclave. The autoclave was sealed and purged with Ar to remove the air at room temperature and subsequently charged with 0.5 MPa of Ar. Then, the autoclave was heated to 200°C, and the autoclave reached the desired reaction temperature within 40 min. After that, the stirrer was started with a stirring speed of 800 rpm, and the reaction time was recorded. After the reaction, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature, and the gas was released. The liquid products were extracted from the reaction mixture using ethyl acetate and concentrated under vacuum. Crude phenol was then purified in a silica gel column with ethyl acetate–petroleum ether as the solvent (1:4, v/v) and concentrated under vacuum. Last, pure phenol was obtained by the crystallization process.

18O isotope labeling test

The isotope labeling experiment was carried out in a Teflon-lined stainless steel reactor of 20 ml with a magnetic stirrer. In the experiment, 4-(1-hydroxypropyl)phenol (1a) (1 mmol), HY30 (0.3 g), and H218O (4.0 ml) were loaded into the reactor. The reactor was sealed and purged with Ar three times to remove the air at room temperature and subsequently charged with 0.5 MPa of Ar. Then, the reactor was placed in a furnace and heated to 180°C. Then, the stirrer was started with a stirring speed of 800 rpm, and the reaction time was recorded. After 1 hour, the reactor was placed in ice water, and the gas was released. The reaction mixture in the reactor was transferred into a centrifuge tube. Then, the reactor was washed with ethyl acetate. After centrifugation, the catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture. Identification of the products was conducted using a GC-MS [Agilent 5977A, HP-5ms capillary column (0.25 nm in diameter and 30 m in length)] by comparing the MS spectra of the products to the reference spectra.

Detection of intermediates

The detection of intermediates was carried out in a Teflon-lined stainless steel reactor of 20 ml with a magnetic stirrer. In the experiment, 1-(4-methoxyphenyl) propan-1-ol (1a) (1 mmol), HY30 (0.3 g), and H2O (4.0 ml) were loaded into the reactor. The reactor was sealed and purged with Ar three times to remove the air at room temperature and subsequently charged with 0.5 MPa of Ar. Then, the reactor was placed in a furnace and heated to 180°C, the stirrer was started with a stirring speed of 800 rpm, and the reaction time was recorded. After 10 min, the reactor was placed in a bath of liquid nitrogen very quickly. When the reaction mixture was frozen, the gas was released immediately. The reaction mixture was freeze-dried under vacuum for 12 hours to remove the water. The detection of the intermediates in the dried sample was conducted by 13C NMR, solid-state 2D 13C{1H} dipolar-mediated HETCOR, and 27Al NMR analyses on Bruker Avance III 400. The solid-state 2D 13C{1H} HETCOR experiment was performed following the procedure described by McGehee and co-workers (51).

Computational methodology

The Vienna ab initio simulation package code based on frozen-core all-electron projector augmented wave method (52) and plane-wave basis was used to perform the spin-polarized DFT computations. The DFT functional PBE-D3 (Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof functional with the latest dispersion correction) was used. It corresponds to the PBE functional and the correction for dispersion effects proposed by Grimme et al. (DFT-D3) (53). A converged kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV was chosen. The structure optimization was carried out by minimizing forces with the conjugate-gradient algorithm until the force on each ion is below 0.02 eV/Å and the convergence criteria for electronic self-consistent interactions are 10−5. The zero vibrational energy correction was not taken into account. The minimum energy pathway for elementary reaction steps was performed using climbing-image NEB (Nudged Elastic Band) calculation (54).

A low-symmetry rhombohedral unit cell was used to model faujasite zeolite (a = b = c = 12.22 Å, α = β = γ = 60°). The general formula of a faujasite zeolite with a pure silicon component is Si48O96. The faujasite zeolite framework contains only one crystallographically tetrahedral T site. On the basis of our experimental results, HY zeolites with a Si/Al ratio of 30 showed the best catalytic performance, indicating that there are approximately two aluminum atoms in a unit cell. Therefore, two aluminum atoms was included our HY unit cell model. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that the two aluminum atoms in the unit cell are spatially adjacent, i.e., one of the sites is used as an active site, and the other, due to space constraints, can adsorb or desorb water molecules to promote the reaction.

The reaction energy (ΔE) and activation energy (Ea) were calculated using the following two formulas: ΔE = E(FS) − E(IS) and Ea = E(TS) − E(IS), respectively. Here, E(TS), E(IS), and E(FS) are the calculated energies of the transition state, initial state, and final state of each elementary step, respectively.

The contribution of entropy to free energy in the adsorption/desorption process were considered in our work. Besora et al. (55) reported that the free-energy corrections from the direct application of popular computational packages with its usual simplified models based on IGRRHO (harmonic oscillator, rigid rotor, and particle-in-a-box) approaches can give a good estimate of the free-energy changes in the liquid-phase reaction. Greeley and co-workers’ work (56) indicated that the most important contributions arise from the translational entropy in the adsorption/desorption process. We used the Gaussian 09 package to calculate the translational entropy of molecules at 423.15 K (experimental temperature) based on the IGRRHO approximation, which is the default method of the package. It was estimated that (C2H5)(OH)CH–Ph–OH molecules lost 0.85 eV of entropic energy (TS) in the adsorption process; the desorption of C3H6O and Ph–OH molecules gained 0.79- and 0.83-eV entropic energy, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. N. Wu for assistance with the NMR measurements. Funding: The work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21703258, 21733011, and 21533011), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0403103), and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z191100007219009). Author contributions: Q.M. and B.H. conceived and designed the present work. J.Y., Q.M., and B.H. wrote the manuscript. J.Y. and Q.M. conducted all of the experimental work. X.S., B.C., Y.S., and J.X. assisted with SEM, TEM, XRD, and NMR measurements. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabd1951/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Niwa S.-i., Eswaramoorthy M., Nair J., Raj A., Itoh N., Shoji H., Namba T., Mizukami F., A one-step conversion of benzene to phenol with a palladium membrane. Science 295, 105–107 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.F. Zhu, J. A. Johnson, D. W. Ablin, G. A. Ernst, Market and technology overview, in Efficient Petrochemical Processes: Technology, Design and Operation (Wiley, ed. 1, 2020), pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H., Jiang T., Han B., Liang S., Zhou Y., Selective phenol hydrogenation to cyclohexanone over a dual supported Pd-Lewis acid catalyst. Science 326, 1250–1252 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morimoto Y., Bunno S., Fujieda N., Sugimoto H., Itoh S., Direct hydroxylation of benzene to phenol using hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by nickel complexes supported by pyridylalkylamine ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5867–5870 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanev P. T., Chibwe M., Pinnavaia T. J., Titanium-containing mesoporous molecular sieves for catalytic oxidation of aromatic compounds. Nature 368, 321–323 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang T., Zhang D., Han X., Dong T., Guo X., Song C., Si R., Liu W., Liu Y., Zhao Z., Preassembly strategy to fabricate porous hollow carbonitride spheres inlaid with single Cu-N3 sites for selective oxidation of benzene to phenol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16936–16940 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng W. P., Wang Y. Z., Zhang S., Gupta K. M., Hulsey M. J., Asakura H., Liu L. M., Han Y., Karp E. M., Beckham G. T., Dyson P. J., Jiang J. W., Tanaka T., Wang Y., Yan N., Catalytic amino acid production from biomass-derived intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5093–5098 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragauskas A. J., Beckham G. T., Biddy M. J., Chandra R., Chen F., Davis M. F., Davison B. H., Dixon R. A., Gilna P., Keller M., Langan P., Naskar A. K., Saddler J. N., Tschaplinski T. J., Tuskan G. A., Wyman C. E., Lignin valorization: Improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 344, 709–719 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao Y., Xia Q. N., Dong L., Liu X. H., Han X., Parker S. F., Cheng Y. Q., Daemen L. L., Ramirez-Cuesta A. J., Yang S. H., Wang Y. Q., Selective production of arenes via direct lignin upgrading over a niobium-based catalyst. Nat. Commun. 8, 16104 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X. J., Fan X. T., Xie S. J., Lin J. C., Cheng J., Zhang Q. H., Chen L. Y., Wang Y., Solar energy-driven lignin-first approach to full utilization of lignocellulosic biomass under mild conditions. Nat. Catal. 1, 772–780 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng H. Q., Cao D. W., Qiu Z. H., Li C. J., Palladium-catalyzed formal cross-coupling of diaryl ethers with amines: Slicing the 4-O-5 linkage in lignin models. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3752–3757 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao Y. H., Koelewijn S. F., den Bossche G. V., Aelst J. V., den Bosch S. V., Renders T., Navare K., NicolaI T., Aelst K. V., Maesen M., Matsushima H., Thevelein J., Acker K. V., Lagrain B., Verboekend D., Sels B. F., A sustainable wood biorefinery for low-carbon footprint chemicals production. Science 367, 1385–1390 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M., Liu M. J., Li H. J., Zhao Z. T., Zhang X. C., Wang F., Dealkylation of lignin to phenol via oxidation-hydrogenation strategy. ACS Catal. 8, 6837–6843 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudarsanam P., Peeters E., Makshina E. V., Parvulescu V. I., Sels B. F., Advances in porous and nanoscale catalysts for viable biomass conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2366–2421 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahimi A., Ulbrich A., Coon J. J., Stahl S. S., Formic-acid-induced depolymerization of oxidized lignin to aromatics. Nature 515, 249–252 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lan W., de Bueren J. B., Luterbacher J. S., Highly selective oxidation and depolymerization of α, γ-diol-protected lignin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2649–2654 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuai L., Amiri M. T., Questell-Santiago Y. M., Héroguel F., Li Y. D., Kim H., Meilan R., Chapple C., Ralph J., Luterbacher J. S., Formaldehyde stabilization facilitates lignin monomer production during biomass depolymerization. Science 354, 329–333 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Z., Fridrich B., de Santi A., Elangovan S., Barta K., Bright side of lignin depolymerization: Toward new platform chemicals. Chem. Rev. 118, 614–678 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renders T., Schutyser W., den Bosch S. V., Koelewijn S. F., Vangeel T., Courtin C. M., Sels B. F., Influence of acidic (H3PO4) and alkaline (NaOH) additives on the catalytic reductive fractionation of lignocellulose. ACS Catal. 6, 2055–2066 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClelland D. J., Galebach P. H., Motagamwala A. H., Wittrig A. M., Karlen S. D., Buchanan J. S., Dumesic J. A., Huber G. W., Supercritical methanol depolymerization and hydrodeoxygenation of lignin and biomass over reduced copper porous metal oxides. Green Chem. 21, 2988–3005 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toppi S., Thomas C., Sayag C., Brodzki D., Fajerwerg K., Peltier F. L., Travers C., Mariadassoua G. D., On the radical cracking of n-propylbenzene to ethylbenzene or toluene over Sn/Al2O3-Cl catalysts under reforming conditions. J. Catal. 230, 255–268 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smaligo A. J., Swain M., Quintana J. C., Tan M. F., Kim D. A., Kwon O., Hydrodealkenylative C(sp3)-C(sp2) bond fragmentation. Science 364, 681–685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy S. K., Park J. W., Cruz F. A., Dong V. M., Rh-catalyzed C-C bond cleavage by transfer hydroformylation. Science 347, 56–60 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corma A., From microporous to mesoporous molecular sieve materials and their use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 97, 2373–2419 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan C., Lv X. Y., Xiao L. J., Xie J. H., Zhou Q. L., Alkenyl exchange of allylamines via nickel(0)-catalyzed C-C bond cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2889–2893 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu S., Shima T., Hou Z., Carbon–carbon bond cleavage and rearrangement of benzene by a trinuclear titanium hydride. Nature 512, 413–415 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y., Yuan X., Guo X., Zhang X., Chen B., Efficient 2-aryl benzothiazole formation from acetophenones, anilines, and elemental sulfur by iodine-catalyzed oxidative C(CO)-C(alkyl) bond cleavage. Tetrahedron 74, 6057–6062 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang M., Lu J. M., Li L. H., Liu H. F., Wang F., Oxidative C(OH)-C bond cleavage of secondary alcohols to acids over a copper catalyst with molecular oxygen as the oxidant. J. Catal. 348, 160–167 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun H., Yang C., Gao F., Li Z., Xia W., Oxidative C-C bond cleavage of aldehydes via visible-light photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 15, 624–627 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roque J. B., Kuroda Y., Gottemann L. T., Sarpong R., Deconstructive fluorination of cyclic amines by carbon-carbon cleavage. Science 361, 171–174 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu D. L., Wang L. Y., Fan D., Yan N. N., Huang S. J., Xu S. T., Guo P., Yang M., Zhang J. M., Tian P., Liu Z. M., A bottom-up strategy for the synthesis of highly siliceous faujasite-type zeolite. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000272 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng Q. L., Fan H. L., Liu H. Z., Zhou H. C., He Z. H., Jiang Z. W., Wu T. B., Han B. X., Efficient transformation of anisole into methylated phenols over high silica HY zeolites under mild conditions. ChemCatChem 7, 2831–2835 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan T.-Q., Sun S.-N., Xu F., Sun R.-C., Characterization of lignin structures and lignin-carbohydrate complex (LCC) linkages by quantitative 13C and 2D HSQC NMR spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 10604–10614 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H. J., Bunrit A., Lu J. M., Gao Z. Y., Luo N. C., Liu H. F., Wang F., Photocatalytic cleavage of aryl ether in modified lignin to nonphenolic aromatics. ACS Catal. 9, 8843–8851 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deepa A. K., Dhepe P. L., Lignin depolymerization into aromatic monomers over solid acid catalysts. ACS Catal. 5, 365–379 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blomsma E., Martens J. A., Jacobs P. A., Reaction mechanisms of isomerization and cracking of heptane on Pd/H-beta zeolite. J. Catal. 155, 141–147 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X., Wang C., Chu Y. Y., Xu J., Wang Q., Qi G. D., Zhao X. L., Feng N. D., Deng F., Observation of an oxonium ion intermediate in ethanol dehydration to ethene on zeolite. Nat. Commun. 10, 1961 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabrienko A. A., Arzumanov S. S., Toktarev A. V., Stepanov A. G., Solid-state NMR characterization of the structure of intermediates formed from olefins on metal oxides (Al2O3 and Ga2O3). J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 21430–21438 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zardkoohi M., Haw J. F., Lunsford J. H., Solid-state NMR evidence for the formation of carbocations from propene in acidic zeolite-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 5278–5280 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haouas M., Walspurger S., Taulelle F., Sommer J., The initial stages of solid acid-catalyzed reactions of adsorbed propane. A mechanistic study by in situ MAS NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 599–606 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X. Y., Liu D. X., Xu D. D., Asahina S. S., Cychosz K. A., Agrawal K. V., Wahedi Y. A., Bhan A., Hashimi S. A., Terasaki O., Thommes M., Tsapatsis M., Synthesis of self-pillared zeolite nanosheets by repetitive branching. Science 336, 1684–1687 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lippmaa E., Samoson A., Magi M., High-resolution 27Al NMR of aluminosilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 1730–1735 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Bokhoven J. A., Koningsberger D. C., Kunkeler P., van Bekkum H., Kentgens A. P. M., Stepwise dealumination of zeolite beta at specific T-sites observed with 27Al MAS and 27Al MQ MAS NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12842–12847 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ehresmann J. O., Wang W., Herreros B., Luigi D. P., Venkatraman T. N., Song W. G., Nicholas J. B., Haw J. F., Theoretical and experimental investigation of the effect of proton transfer on the 27Al MAS NMR line shapes of zeolite-adsorbate complexes: An independent measure of solid acid strength. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 10868–10874 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busca G., Acid catalysts in industrial hydrocarbon chemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 5366–5410 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiricsi I., Forster H., Tasi G., Nagy J. B., Generation, characterization, and transformations of unsaturated carbenium ions in zeolites. Chem. Rev. 99, 2085–2114 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y. D., Shuai L., Kim H., Motagamwala A. H., Mobley J. K., Yue F. X., Tobimatsu Y., Havkin-Frenkel D., Chen F., Dixon R. A., Luterbacher J. S., Dumesic J. A., Ralph J., An “ideal lignin” facilitates full biomass utilization. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau2968 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emeis C. A., Determination of integrated molar extinction coefficients for infrared absorption bands of pyridine adsorbed on solid acid catalysts. J. Catal. 141, 347–354 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huijgen W. J. J., Reith J. H., den Uil H., Pretreatment and fractionation of wheat straw by an acetone-based organosolv process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49, 10132–10140 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao Z., Engelhardt J., Dierks M., Clough M. T., Wang G. H., Heracleous E., Lappas A., Rinaldi R., Schuth F., Catalysis meets nonthermal separation for the production of (Alkyl) phenols and hydrocarbons from pyrolysis oil. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 2334–2339 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham K. R., Cabanetos C., Jahnke J. P., Idso M. N., El Labban A., Ndjawa G. O. N., Heumueller T., Vandewal K., Salleo A., Chmelka B. F., Amassian A., Beaujuge P. M., McGehee M. D., Importance of the donor: Fullerene intermolecular arrangement for high-efficiency organic photovoltaics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9608–9618 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kresse G., Joubert D., From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H., A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henkelman G., Uberuaga B. P., Jonsson H., A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Besora M., Vidossich P., Lledos A., Ujaque G., Maseras F., Calculation of reaction free energies in solution: A comparison of current approaches. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 1392–1399 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu X. K., Liu B., Greeley J., First-principles study of sructure sensitivity of ethylene glycol conversion on platinum. ACS Catal. 5, 2623–2631 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L. B., Yan L. S., Wang Z. M., Laskar D. D., Swita M. S., Cort J. R., Yang B., Characterization of lignin derived from water-only and dilute acid flowthrough pretreatment of poplar wood at elevated temperatures. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8, 203 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao W., Li X., Li H., Zheng X., Ma H., Long J., Li X., Selective hydrogenolysis of lignin catalyzed by the cost-effective Ni metal supported on alkaline MgO. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 19750–19760 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu S., Argyropoulos D., An improved method for isolating lignin in high yield and purity. J. Pulp Pap. Sci. 29, 235–240 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rabemanolontsoa H., Saka S., Comparative study on chemical composition of various biomass species. RSC Adv. 3, 3946–3956 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabd1951/DC1