To the Editor

The 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19 due to SARS-CoV-2 infection) pandemic has been declared an international public health emergencyassociated with substantial mortality with global case numbers surpassing 2,000,0001.The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 diseasein children and young adults ranges from asymptomatic infections to mildsymptoms, only rarely leading to fulminant respiratory failure2. Here, we report the first case of life-threatening immune cytopeniasin a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This case highlights a previously unreported potential COVID-19-related complication2,3.

A17-year-old male with a history of refractory chronic immune thrombocytopenia (cITP)presented with progressive jaundice and fatigue in the setting of4 days of emesis, diarrhea, and fevers.Prior to this presentation, the patient’scITPhad beenwell controlled on eltrombopag and mycophenolate. Given thehistory of immune cytopenia, lymphopenia,splenomegaly,hypogammaglobulinemia and apersistently elevated CD3+CD4-CD8- T-cell population in peripheral blood, the patient had been thought to have autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) or an alternative immune dysregulation syndrome. Clinical sequencing had been unrevealing to date for a known genetic cause of immune dysregulation4. Importantly, the patient had previously negative direct antiglobulin (DAT) testing without signs of anemia or hemolysis, including in the months prior to presentation.

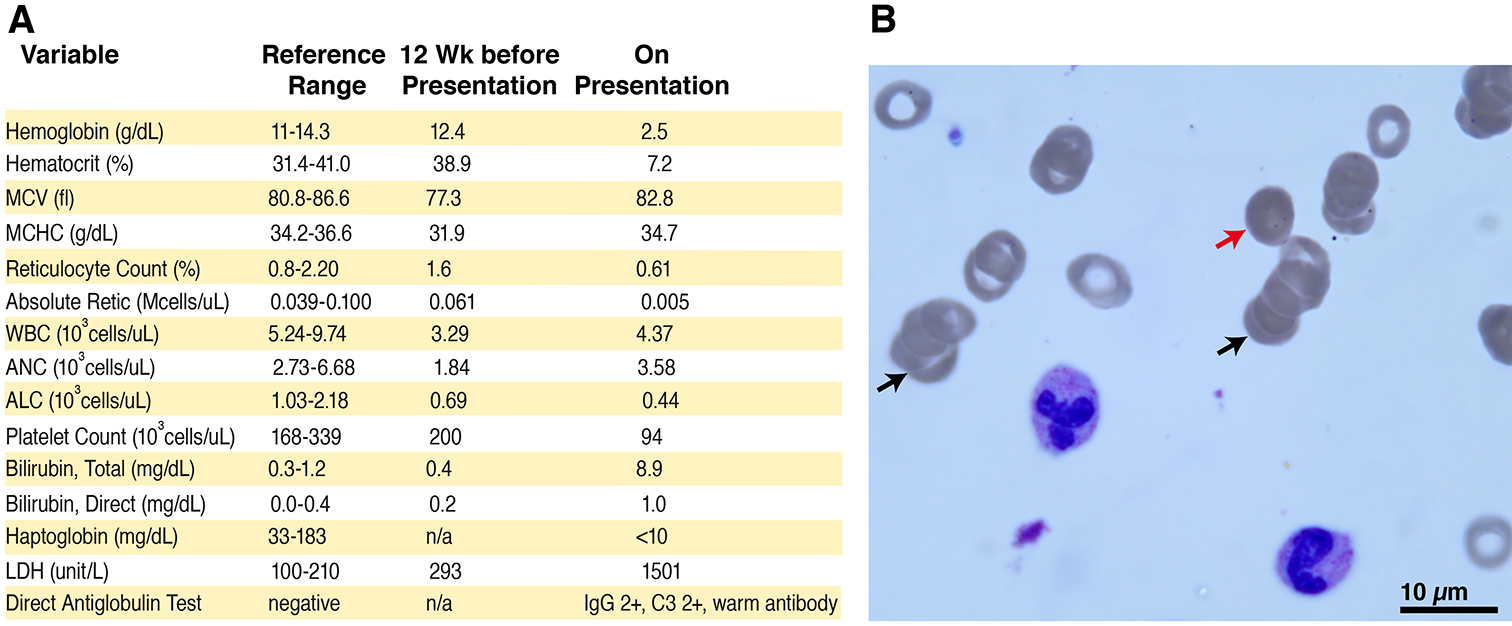

Upon presentation, the patient was noted to be alert but fatigued. He was febrile, tachycardic, tachypneic, and hypoxic.His initial exam was notable for marked pallor and jaundice. He had clear breath sounds bilaterally, but increased work of breathing. Chest radiograph showedmild prominence of perihilar markings. PCR nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 was positive and negative for other respiratory viruses. Laboratory evaluation demonstrateda warm DAT positive (IgG 3+, C3 1+) reticulocytopenic anemia with a hemoglobin of 2.5 g/dL and absolute reticulocyte count of0.011 cells/uL, LDH of 1280 units/L, and a total bilirubin of 8.9 mg/dL.Other abnormal hematological parameters included lymphopeniaand thrombocytopenia(Figure 1A). Peripheral blood smear demonstrated rouleaux formation, presence of microspherocytes, hypochromic microcytic red blood cells,and large platelets (Figure 1B). The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous corticosteroids andoxygen supplementation and received a red blood cell transfusion. Within 48 hours after initiation of corticosteroids, hemolysis improvedwith a stabilized hemoglobin and significant decrease in bilirubin and LDH.Additionally,oxygen saturations normalized after red blood cell transfusion and his respiratory status improved.Given the patient’s history of refractory cITP, he was restarted on his prior regimen of eltrombopag and mycophenolate and a steroid wean was initiated.

Figure 1: Laboratory evidence of autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

A) Panel A shows hematological parameters prior to presentation and upon admission. B) Panel B displays a representative image of the peripheral blood smear, demonstrating rouleaux formation (black arrows), presence of microspherocytes (red arrow), hypochromic microcytic red blood cells, as well as large platelets.

Overall,thispresentation was consistent with Evans syndrome with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), a disease that can be triggered through polyclonal activation of autoreactive B-lymphocytes, leading to the emergence of red blood cell-directed autoantibodies5. While a direct causal relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and manifestation of AIHA cannot be demonstrated, the temporal association of this presentation suggests SARS-CoV-2 infection as a potential trigger, particularly in a patient with an underlying immune dysregulation syndrome. With the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 disease attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we suggest that patients who are immunosuppressed or have underlying immune dysregulation may have atypical presentations. Indeed, the notable immune activation with COVID-19 disease in adults3 may be associated with altered presentations in those with immune dysregulation, such as the development of new onset autoantibodies as we report here.

Funding information:

This work is supported by NIH (R01 DK103794).

References:

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019. Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol 2020;40:24–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalfa TA. Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016;2016:690–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]