Abstract

Introduction

The rapid spread of COVID‐19 across the globe is forcing surgical oncologists to change their daily practice. We sought to evaluate how breast surgeons are adapting their surgical activity to limit viral spread and spare hospital resources.

Methods

A panel of 12 breast surgeons from the most affected regions of the world convened a virtual meeting on April 7, 2020, to discuss the changes in their local surgical practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Similarly, a Web‐based poll based was created to evaluate changes in surgical practice among breast surgeons from several countries.

Results

The virtual meeting showed that distinct countries and regions were experiencing different phases of the pandemic. Surgical priority was given to patients with aggressive disease not candidate for primary systemic therapy, those with progressive disease under neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and patients who have finished neoadjuvant therapy. One hundred breast surgeons filled out the poll. The trend showed reductions in operating room schedules, indications for surgery, and consultations, with an increasingly restrictive approach to elective surgery with worsening of the pandemic.

Conclusion

The COVID‐19 emergency should not compromise treatment of a potentially lethal disease such as breast cancer. Our results reveal that physicians are instinctively reluctant to abandon conventional standards of care when possible. However, as the situation deteriorates, alternative strategies of de‐escalation are being adopted.

Implications for Practice

This study aimed to characterize how the COVID‐19 pandemic is affecting breast cancer surgery and which strategies are being adopted to cope with the situation.

Keywords: Breast cancer surgery, COVID‐19, Triage, Surgical priorities, Alternatives to surgery

Short abstract

This article evaluates how breast surgeons are adapting surgical activity to limit viral spread and spare resources during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic is affecting health resources on a global scale and has a significant impact on oncological management [1]. Clinicians must balance standard cancer therapies with measures designed to limit the spread of COVID‐19. At the same time, health care workers face many challenges, including shortage of resources (e.g., personal protective equipment), excessive working hours, and psychological distress [2, 3, 4].

Breast cancer (BC) is a common disease affecting one in eight Western women and is potentially lethal [5]. For the majority of patients with early stage BC, surgery remains the primary treatment, but a delay from diagnosis to start of treatment of less than 90 days does not appear to adversely affect prognosis [6]. This rule, however, does not apply to all clinical scenarios, and patients who need surgery more urgently should be identified through appropriate and effective triage [7]. Decisions on treatment must take into account the individual risk of exposure and infection and balance it with the potential risk of a worse oncological outcome if the appropriate treatment does not commence in a timely fashion.

According to the World Health Organization, social distancing, quarantine (for asymptomatic COVID‐19–positive patients, people who came in contact with COVID‐19–positive patients, and people coming from areas with a high number of COVID‐19 cases), and wearing face masks when in proximity to others are the most effective measures to control the spread of COVID‐19. These measures can help to slow down the rate of new infections, allowing health care systems to cope with clinical demand and allocate sufficient resources in the quest for an effective therapy and continuing ongoing research [8, 9].

However, the combination of social distancing and reduced resources may clash with the surgical management of patients with breast cancer.

This study aims to examine the changes in the surgical management of patients with breast cancer during the different phases of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Results of this study will provide better understanding of how health care systems rapidly adapt to a new crisis and highlight key elements for planning the recovery phase.

Materials and Methods

Group for Reconstructive and Therapeutic Advancements (G.Re.T.A.) is an international organization founded in 2017 that aims to bring together breast cancer specialists to advance multidisciplinary educational and research activity [10]. The organization convened a virtual meeting entitled “The Surgical Management of Breast Cancer During the COVID‐19 Emergency.” A Web‐based poll designed to explore the different approaches and responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic was launched 3 days prior to the scheduled meeting.

Virtual Meeting

A panel of 12 dedicated breast surgeons from nine countries across three continents were invited to participate in a virtual meeting held on the April 7 at 4:00 p.m. GMT + 1. The panel included breast surgeons from those areas most affected at the time by COVID‐19 (Iran, Italy, Spain, U.K., and U.S.) together with other specialists from China, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland.

All panel members were invited as spokespersons for their respective multidisciplinary team.

In addition, an experienced medical oncologist (C.C.) was invited to contribute and supervise the multidisciplinary discussion. Panelists discussed the following topics in accordance with corresponding national and local/institutional guidelines:

Pandemic phase according to American College of Surgeons (ACS) [7]

Triage and management of new breast clinic referrals and breast cancer diagnoses

Surgical priorities

Alternatives to surgery

Management of admitted patients (including operating room)

Management and modalities of consultations

The virtual meeting was advertised through the G.Re.T.A institutional Web site and on social media. Ninety participants joined the meeting.

Web‐Based Poll

An anonymous Web‐based poll was set up on April 4, 2020, and all the panelists and the participants in the virtual meeting were invited to participate. The poll was also circulated through G.Re.T.A. social media in order to reach the largest number of participants. The poll was based on the American College of Surgeons' “COVID‐19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care of Breast Cancer” issued on March 24, 2020, by the ACS and available online [7] (supplemental online Table 1).

The questionnaire included eight items (supplemental online Table 2): geographical area, position of participant, pandemic phase according to the aforementioned guidelines, priorities in breast cancer surgical management (cases to be done as soon as possible), cases that can be deferred, alternative treatment approaches to be considered, modalities of consultations and long‐term follow‐up, and operating room schedule.

Because of the rapid evolution of the pandemic, a prespecified number of total participants was fixed at 100. The poll closed on April 14 after reaching the prespecified goal.

Data Analysis

Replies were grouped according to geographical area experiencing a similar phase of the pandemic. Replies to topics (d)–(h) are listed according to progressive restrictions. Because of the reduced sample size and in order to perform statistical analysis, we grouped variables to become bivariate (i.e., standard vs. restricted modalities) (supplemental online Table 3). Response rates were compared among groups using Fisher's exact test. Values of p < .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Virtual Meeting

On the meeting day, different countries and regions were in different phases of the pandemic [11], and therefore participants were in different ACS phases. This was true also within the same country and within large cities.

Differences were observed in the surgical management of BC among panelists from different countries and from different institutions within the same country (private vs. public hospitals, academic or tertiary care) and are summarized in Table 1. In some countries, multiple guidelines and consensus statements issued by different scientific societies and institutions were available [7, 12, 13, 14], whereas in other countries equally affected, no specific breast surgery–related guidelines had been released by official entities.

Table 1.

Virtual meeting results

| Location | Phase | Lockdown a | Screening | Management at admission | Surgical prioritization | Alternatives | Reconstruction | Outpatients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | / | January 23 | Stopped |

Travel History Clinical history Temperature screening CT scan; nucleic acid detection from samples of throat swabs One patient one single room Mask to all patients |

Surgical procedures that cannot be postponed: patients finishing NAC, cancer progressing during NAC, DCIS, malignant tumor such as sarcoma or malignant phyllodes tumor | NAC according to standard criteria |

Simplify reconstruction method (only implant‐based reconstruction, or tissue expander if possible PMRT) to reduce risks of complications and shorten time of exposure Decrease robot/free flap reconstruction |

WeChat group/e‐mail used during emergency Self‐protection and social distancing advised |

| Italy (Lombardy) | II | March 15 | Stopped |

Clinical history Temperature screening, blood check, SpO2, x‐ray Eventual swab or low‐dose CT in selected cases Suspicious cases were postponed (1–2 weeks) Visits mainly for pre‐ and postoperative patients “Hub and spokes” hospital model |

In 2–4 weeks: cancer progressing during NAC; premenopausal patients with aggressive disease not candidate for NAC, local‐regional recurrence within 48 months, pregnant patients, patients with complications In 4 and 8 weeks: grade 2 tumors, premenopausal patients with T < 3 cm, N0 cancer not candidate for NAC, patients who have finished neoadjuvant therapy >8 weeks: grade 1 tumors, DCIS, benign disease |

NAC according to standard criteria Endocrine therapy as a bridge to surgery in ER+ tumors out of priority criteria Outside standards MDT decision is needed |

Only immediate implant‐based reconstruction after mastectomy is allowed |

Postsurgery and “urgent” visits (3–10 days) E‐mail/phone calls Telemedicine service |

| Iran | II | March 20 | Stopped |

Any travel or close contact Clinical history Temperature screening, SpO2 Chest CT and COVID‐19 test only after consultation and for suspicious cases (if positive, admission denied) All procedures done as day cases |

Priority A/B A (as soon as possible): drainage of breast abscess, hematoma, ischemic flap B1 (start treatment before the pandemic is over): refractory or progressive case under neoadjuvant therapy, malignant phyllodes tumor, cancer in first trimester of pregnancy, diffuse or big comedo‐type DCIS B2 (if resources are enough): post‐neoadjuvant cases, T1 N0/T2 N1 luminal cases, stage 1 triple negative, discordance biopsy likely to be malignant, recurrent disease, ER− DCIS |

NAC according to standards and for chemo/anti‐HER2 agents sensitive irrespective of stage (except for TNBC stage 1) Endocrine therapy for ER+/HER2− (LumA‐like cases), reevaluate after 3 months; ER+ BC finishing NAC with partial/complete clinical, consider converting to endocrine therapy in order to delay surgery versus surgery for 4–8 weeks |

No reconstruction | Postsurgery and follow‐up done remotely |

|

Spain (private) |

I | March 29 | Stopped |

Clinical history Temperature screening Contacts If suspicious, admission denied and referred to swab test Negative PCR required to receive surgery Same day discharge Visits mainly for pre‐ and postoperative patients |

Surgical procedures that cannot be postponed (patients finishing preoperative systemic treatment) |

NAC according to standard criteria Endocrine therapy according to standard criteria and for premenopausal patients with HR+/HER2− ESBC |

Implant‐based reconstruction It is offered if low risk of complications (low BMI, no smokers, no comorbidities, <60 years) |

Limitations at the waiting room No follow‐up Telematic consultation whenever possible |

|

Spain (academic) |

III | March 29 | Stopped |

Clinical history Temperature screening, contacts history Negative PCR required to receive surgery Same day discharge Visits mainly for pre‐ and postoperative patients |

Surgical procedures that cannot be postponed (patients finishing preoperative systemic treatment) |

NAC according to standard criteria Endocrine therapy according to standard criteria and for premenopausal patients with HR+/HER2− ESBC |

Implant‐based reconstruction |

Limitations at the waiting room No follow‐up Telematic consultation whenever possible |

| U.K. (England) | II | March 23 | Stopped |

Clinical history Physical examination PCR test, if available, for every patient Recent CT chest (last 24 hours) or, failing that, CXR Clip all cancers when biopsy performed Aim for day case surgery; do minimum Minimum staff in theater; appropriate PPE for all staff All patients are intubated and extubated in theater |

Surgical priority given to patients with ER− disease first, then patients with HER2+ disease Post‐NAC High grade DCIS (ER+ started on HT, ER− candidate for surgery) If highly suspicious COVID‐19 infection or positive test, postpone surgery, then reevaluate Incise tumor and mark it to reduce specimen manipulation by pathologists (protect pathologists) All specimens are fixed in formalin |

NAC only for inoperable patients Endocrine therapy according to standard criteria and for ER+ DCIS (all core biopsies demonstrating DCIS should be tested for hormone receptor status) Perform genomic testing on the biopsy specimen for invasive breast cancer and consider endocrine therapy ER+/HER2− BC post‐NAC: consider converting to endocrine therapy in order to delay surgery ER+/HER2+ BC post‐NAC: consider converting to NET + anti‐HER2 therapy in order to delay surgery |

No reconstruction |

Triage all referrals Telephone consultation Face‐to‐face clinic; 5–6 patients per clinic 30‐minute slot each Patients aged ≥70 years or patients with significant comorbidities: no clinic visit Only phone consultation Start empirical HT if suspicious |

| U.K. (Scotland) | I | March 23 | Stopped |

COVID‐19 test only for symptomatic patients Clinical history Highly suspicious need PCR testing If safe, perform procedures as day surgery |

Surgical priority given to patients with ER− disease first, then patients with HER2+ disease Post‐NAC High grade DCIS (ER+ started on HT, ER− candidate for surgery) If highly suspicious COVID‐19 infection or positive test, postpone surgery 2/52, then reevaluate Incise tumor and mark it to reduce specimen manipulation by pathologists (protect pathologists) All specimens are fixed in formalin |

NAC according to standard criteria Endocrine therapy: ER+ DCIS (all core biopsies demonstrating DCIS should be tested for hormone receptor status) ER+/HER2− BC (perform genomic testing on the biopsy specimen, and consider endocrine therapy or NAC if appropriate) ER+/HER2− BC post‐NAC: consider converting to endocrine therapy in order to delay surgery ER+/HER2+ BC post‐NAC: consider converting to NET + anti‐HER2 therapy in order to delay surgery |

No reconstruction |

All urgent referrals are accepted Routine referrals postponed or cancelled |

| U.S. (New York City) | II | March 22 | Stopped |

Telephone triage Clinical history Temperature screening Blood check SpO2 +/‐ COVID‐19 test |

Life‐threatening conditions: breast abscess in a patient with sepsis, expanding hematoma Urgent cases: ischemic autologous tissue flap/mastectomy flap, patients who have finished NAC, progression under NAC BCS is preferred, provided that radiation oncology services are available and the risk of multiple visits or deferred radiation is acceptable If no ventilator available or high risk of exposure, BCS can be performed under local anesthesia via sedation |

NAC for TNBC/HER2+ (≥ T2 or N1) Some ER+/HER2− Inflammatory/ locally advanced BC Endocrine therapy: ER+ DCIS (all core biopsies demonstrating DCIS should be tested for hormone receptor status) ER+/HER2− BC (perform genomic testing on the biopsy specimen, and consider endocrine therapy or NAC if appropriate) ER+/HER2− BC post‐NAC: consider converting to endocrine therapy in order to delay surgery ER+/HER2+ BC post‐NAC: consider converting to NET + anti‐HER2 therapy in order to delay surgery |

Limited to tissue expander or definitive implant placement Autologous reconstruction should be deferred |

The majority of encounters are conducted remotely via telemedicine If need for in‐person evaluation special measures to reduce the risk of infection are put in place |

| Sweden | I | Decision on a regional level; decreased participation |

COVID‐19 test only for symptomatic patients If medically safe, perform procedures as day surgery |

Priority as follows: patients who have completed or discontinued primary chemotherapy, then TNBC, HER2+, then LumB, then LumA, DCIS grade 3 with larger size |

NAC according to standard criteria Endocrine therapy: >70 yr, LumA or B N0/1 60–70 yr, LumA N0 |

Perform breast reconstruction in exceptional cases; choose the simplest alternative |

Only absolutely necessary referrals Calls, video calls when appropriate |

|

| Denmark | I | March 12 | Unchanged | COVID‐19 test only for symptomatic patients |

BIRADS 4 and 5 lesions treated as always BIRADS 3 treated on MDT decision BIRADS 1–2 postponed |

NAC according to standard criteria Patients informed on potential risks of chemotherapy during the COVID‐19 pandemic |

As usual, some limitations for the DIEP flap | Normal consultations (only distancing) for BIRADS 4–5 and some BIRADS 3 |

| Switzerland (Italian‐speaking part) | I | March 16 | Stopped | COVID‐19 test for all symptomatic patients within 48 hours before surgery | Standard indications to surgery | NAC, including immune and endocrine therapy according to standard criteria | Standard indications for breast reconstruction if beneficial for patient, including autologous reconstruction |

Consultations limited to only not deferrable ones Most consultations via telephone, video calls or e‐mail |

| Portugal | I | March 18 | Stopped |

Clinical history Physical examination Temperature screening Chest x‐ray WBC COVID‐19 test for all symptomatic patients |

Patients completing NAC Only level I oncoplastic breast conserving surgery |

NAC according to standard criteria | No reconstruction |

Urgent referrals only Face masks for all patients and social distance in waiting room |

Lockdown dates as reported on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curfews_and_lockdowns_related_to_the_2019%E2%80%9320_coronavirus_pandemic (except for Iran).

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; BCS, Breast Conserving Surgery; BIRADS, Breast Imaging–Reporting and Data System; BMI, body mass index; CT, computed tomography; CXR, Chest X Ray; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; DIEP, deep inferior epigastric perforator; ER, estrogen receptor; ESBC, early stage breast cancer; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; HT, hormonal therapy; LumA, luminal A; LumB, luminal B; MDT, multidisciplinary team; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NET, Neoadjuvant Endocrine Therapy; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy; PPE, personal protection equipment; SpO2, oxygen saturation; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer; WBC, white blood cells.

The starting date of lockdown varied from January 23 (in China, where the lockdown was already concluded at the time of the meeting) to March 29 (Spain). Notably, this measure was not applied in Sweden, where social distancing was voluntary.

BC screening programs were halted in most countries, except for Sweden and Denmark. Most of the countries in phase 2 or 3 had implemented a triage system (the day before or the day of admission), which took place at the hospital or via teleconsultation in advance of any face‐to‐face (FTF) encounter (U.K. and U.S.). Screening methods varied between and within countries, ranging from clinical history only to temperature assessment with screening and oxygen saturation check and nasopharyngeal swabs with chest x‐ray/computed tomography scan. Nasopharyngeal swabs with negative results were mandatory before surgery in Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy (with variations according to local institution policy). In other countries, polymerase chain reaction testing on swabs was indicated only for symptomatic patients (Italy, U.K., Sweden, Denmark). Allocation of single rooms was routinely adopted in China, and the use of masks by patients was strongly recommended in all countries.

Same day discharge policy wherever possible was preferred although not mandatory (Italy, Spain, U.K., Sweden, Denmark, and U.S.).

Surgical prioritization varied between countries and according to the phase of the pandemic. China had resumed standard clinical practice, whereas Italy, the U.S., and the U.K. were prioritizing urgent cancer cases in anticipation of the need for intensive care unit (ICU) facilities. Priorities for surgery included patients with progressive disease while on neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), patients who have finished NAC, patients with small triple negative (TN) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive BC, and patients with T2N0 hormone receptor (HR) positive/HER2− BC not deemed eligible for neoadjuvant treatment cases (Italy). In Italy, Spain, and the U.K., patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) were not considered a priority and could be deferred (Italy >8 weeks) depending on ventilator availability. In the U.S. and U.K., receptor status testing was recommended for all cases of DCIS, and endocrine therapy was recommended for hormone HR+ DCIS [12, 13]. There was consensus across countries that primary systemic treatment was an acceptable alternative strategy to defer surgical excision and should be based on national or international guidelines. In both the U.K. and U.S., it was considered acceptable to defer surgery by commencing primary endocrine treatment in patients with HR+/HER2−, node‐negative tumors. Because of the broadening of indications for preoperative therapy, genomic (or Ki‐67/grade) testing of core biopsy material was discretionary for some higher‐risk tumors.

The majority of panelists deferred immediate breast reconstruction (IBR), especially more complex autologous flap‐based procedures, yet most considered two stage implant‐based IBR a safe and manageable option.

Web‐Based Poll

A total of 100 breast surgeons completed the poll, with the majority (90%) being fully accredited surgeons and only 10% being trainees. Two‐thirds of respondents (63%) worked in a phase 1 setting with relatively few patients with COVID‐19 and availability of ICU beds. Just over one third were based in the most severely affected European areas (Italy, Spain, France, and U.K.), with just 19% from South America, 8% from Iran, and the remaining 35% from other countries.

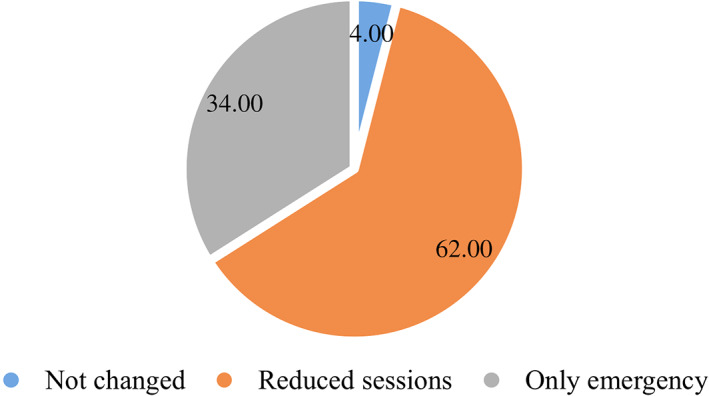

The poll revealed a general contraction of breast surgical capacity across the world, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Operating room schedule distribution.

As the pandemic worsened with increasing demand for ICU and ventilator facilities, there was a gradual shift from elective to emergency surgery only (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in the operating room schedule according to the American College of Surgeons phase.

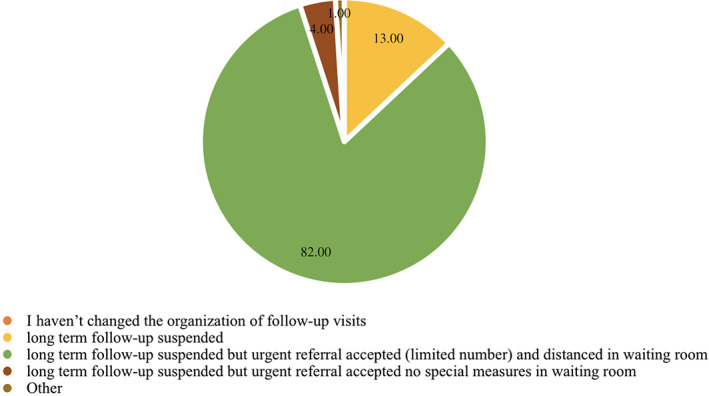

Similarly, the total number of FTF consultations fell across all countries surveyed (Fig. 3) with suspension of routine follow‐up visits and acceptance of urgent referrals only in more than three quarters of units in phase 1 (84%) and all those (100%) in phase 3.

Figure 3.

Organization of consultations and long‐term follow‐up visits.

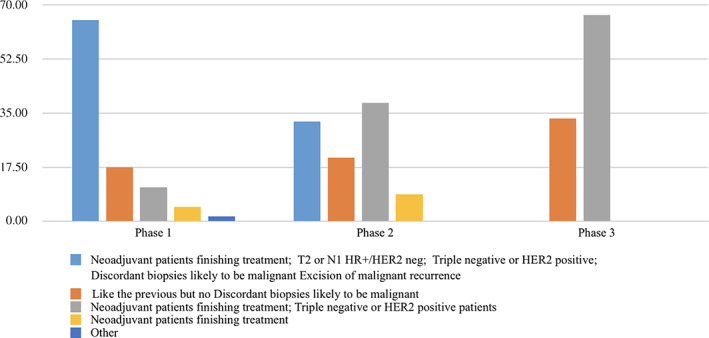

Just over half of respondents (52%) prioritized surgery after NAC, for T2N1 HR+/HER2− cancers, for discordant biopsies likely to be malignant, and for excision of malignant recurrence.

There was a statistically significant association between the level of surgical restriction and the pandemic phase (p = .001), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Changes in the surgical priorities according to the American College of Surgeons phase.Abbreviations: HER2 neg, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative; HR+, hormone receptor positive.

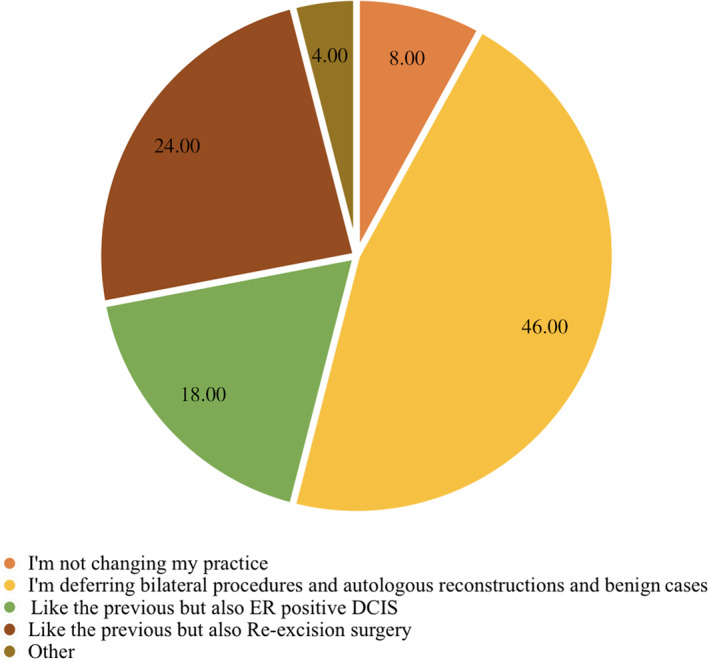

Overall, the great majority (88%) of surgeons deferred benign cases, bilateral procedures, and autologous reconstructive surgery (Fig. 5). With progression of the pandemic from phase 1 to 3, surgeons also deferred in situ HR+ disease as well as re‐excision cases.

Figure 5.

Distribution of cases that can be deferred.Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor.

Almost half (48%) of respondents offered primary systemic treatments as an alternative to surgery for the following categories of tumor. Endocrine therapy was offered for T1N0 HER+/HER2− tumors and some T2 or N1 HR+/HER2− cancers. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or single or dual anti‐HER2 agents were offered for TN and HER2+ tumors. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was offered for N1 cancer irrespective of subtype.

This approach was more likely to be adopted by participants with increasing severity of the COVID‐19 pandemic (40% in phase 1, 62% in phase 2, and 67% in phase 3). Fourteen and 8% of participants in phases 1 and 2, respectively, did not change their clinical decision‐making process in regard to neoadjuvant treatments (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in the alternative treatment approach according to the American College of Surgeons phase.Abbreviations: Her2 neg, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative; HR+, hormone receptor positive.

Discussion

Resources and Surgical Management

Changes in the management of newly diagnosed breast cancer in response to COVID‐19 varied according to geographic area and pandemic phase, but also between different institutions within a particular country. The unprecedented speed and scale of the outbreak precluded the establishment of any formal guidelines based on international consensus.

Our survey confirms a global reduction in the volume of elective breast surgery that may be attributable either to a shortage of facilities and limited surgical capacity during the crisis or possibly to social distancing imposed by health authorities with resultant limited access to health care in general.

In principle, patients are prioritized for surgery based on completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, small (T1/N0) TNBC or HER2 subtypes, and T2 or N1 HR+/HER2− tumors. In the event of a shortage of ventilatory and operating room capacity, a crucial question is how long surgical management can be deferred without impairment of clinical outcomes. In a joint analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare–linked database and the National Cancer Database, delays of more than 90 days from diagnosis to treatment have been shown to be associated with reduction in overall survival rates of 3.1% to 4.6% [6]. By implication, it might therefore be considered appropriate to schedule surgery for within 90 days if no other treatment is commenced as primary therapy.

However, when breast surgery is performed, its impact on the health care system is relatively modest; there are relatively short operating times and limited need for intensive care facilities with much surgery being performed as a day case procedure with few complications. The readmission rate for complications after breast surgery as estimated by the American College of Surgeons–National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database is approximately 4% within 30 days [15]. The postsurgical ICU admission rate after breast surgery is estimated to be 1.8% and is not comparable to major surgery [16]. Few complications after breast surgery also mean fewer patients coming back to hospital for postsurgical consultation or secondary procedures, and consequently less urban mobility both of patients and caregivers.

Our survey confirms that theater lists can be managed with relatively few resources and that breast surgeons tend to use any residual capacity to operate (even in phase 2).

Special considerations apply to IBR, and these are very much dependent on local circumstances and operative capacity. Increased complication rates are associated with IBR (14.2% for implant‐based and 15.4% for autologous compared with 4.2% without IBR), and this has prompted some countries to limit all forms of IBR and in particular to stop autologous tissue‐based reconstruction [17]. For younger patients wishing to preserve the skin envelope, a “babysitter implant” or a formal epipectoral approach may be an option but might lead to additional postoperative visits and potential readmission to hospital. Most of the participants deferred bilateral procedures (such as most of stage II of tissue expander/implant reconstructions) or autologous reconstructions. According to the poll, during phase progression more restrictive indications also prevented re‐excisions and excision biopsy of uncertain lesions.

Alternatives to Surgery

With the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID‐19 pandemic in which there are potential shortages of ventilator equipment and ICU personnel, professional bodies have recommended alternative therapeutic options as a short‐term imperative. These are not necessarily based on published data but reliant on “educated assumptions and expert opinion” [18].

The panel relayed information on national and institutional recommendations for COVID‐19 protocols with several links available to association Web sites [7, 12, 13, 19]. The ACS triage, for instance, is recommending 6–12 months of primary endocrine treatment in luminal A tumors or tumors with Oncotype DX score < 25% [7]. However, before the current pandemic, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines supported use of primary endocrine therapy mainly in patients with comorbidities and low‐risk estrogen receptor–positive invasive breast cancer [20]. Historically, this treatment has been used for elderly patients with comorbidities who were considered unfit for surgery [21, 22, 23]. Concerns exist regarding preoperative endocrine therapy for premenopausal women or for those with longer life expectancy [24]. The ideal duration of preoperative endocrine treatment is unclear, but usually it should be given for at least 6 months, and in case of lack of response, surgery should be carried out [25, 26, 27]. In some countries, primary endocrine therapy is also advised for HR+ DCIS, and hence all core biopsies should be tested for HR [12, 13]. These approaches are in line with trials investigating nonoperative management of low‐risk DCIS in which primary endocrine therapy may be an option in the observation arm [28, 29, 30]. Nonetheless, observation alone can be considered for smaller low‐risk DCIS irrespective of HR status and pending operative availability [12]. Outcomes for DCIS managed without locoregional intervention were investigated using the SEER database, and low rates of progression to invasive disease were demonstrated. However, results may have been confounded by concurrent use of systemic endocrine treatment in some patients [31].

The poll revealed that a sizable proportion of participants considered primary chemotherapy to be routine for many patients with specific subtypes of breast cancer, namely, TNBC and HER2+. This practice could be extended to all patients with N1 disease irrespective of HR status and to some larger T2 HR+, HER2− cancers. Indeed, a trend for broadening indications for primary systemic therapy was evident with increasing gravity of the pandemic and pressure upon emergency services.

Some experts, according to national societies, are suggesting the use of genomic testing preoperatively to identify HR+/HER2− cancers, which may be chemosensitive, in order to defer surgery and give NAC irrespective of tumor stage [32].

Some experts, conversely, report a particular concern about the risk of COVID‐19 infection, because of immunosuppression, for patients undergoing chemotherapy. This had led some countries to restrict, instead of expand, the indications to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with early stage disease [13].

Management of Screening, Outpatient Workload, and Referrals

Universal suspension of breast cancer screening services has been reported around the world. Depending on the duration of shutdown, there may or may not be any clinically meaningful impact on breast cancer mortality. It is also unclear whether during the recovery phase, rules of social distancing will impact on the number of women invited per each screening session.

Evidence for reorganization of FTF consultations has emerged from this poll, and this applies to both newly diagnosed symptomatic breast cancers and postoperative cases. According to the amended guidelines of the COVID‐19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium, in‐person visits should be converted to telemedicine, whenever possible, unless there is clinical urgency for FTF consultation [33]. The COVID‐19 pandemic has allowed widespread conversion to telemedicine, demonstrating its utility as an effective tool for social distancing in the clinical setting and for reducing outpatient workload without compromising optimal care. In the current crisis, telemedicine can be used to communicate both benign and malignant pathology results and to initiate endocrine treatment as primary or adjuvant therapy. Of course, reliable infrastructures should be available across the world, as well as trained staff, a validated workflow, and safe management of individual data [34]. The quality of care in telemedicine should be comparable to in‐person care, although physical examination is necessarily precluded. Nonetheless, the overall care process should not be compromised in any way that might threaten patient safety. Robust protocols must exist that permit discrimination between visits that can safely be performed in telemedicine and those mandating physical examination.

In some regions of the world affected by COVID‐19, local governments have opted for COVID‐19–dedicated and COVID‐19–free or –light hospitals for treatment of specific conditions. For example, in the U.K., U.S., and parts of Italy, some dedicated cancer hospitals have continued to offer oncological care within standard time frames and adhered to routine management protocols. A negative pharyngeal swab before access to these facilities was essential, and patients were treated only if negative for COVID‐19. In some institutions, cancer surgery was deferred for COVID‐19–positive patients pending resolution of symptoms and two subsequent negative swabs (COVID‐19–free hospitals), whereas other institutions reserved clinical and operating areas for treatment of COVID‐19–positive patients.

Conclusion

Approximately 150,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed every month worldwide. Once screening has been suspended and breast consultations reduced, delays in diagnosis of small screen‐detected and some symptomatic cancers might be expected. However, any delays attributable to COVID‐19 are unlikely to have any prognostic impact on these indolent, slow‐growing tumors or indeed for cases of “overdiagnosis.” This is why, after the pandemic, phase criteria for prioritization will continue to be refined and aid in selecting those patients who are appropriate candidates for primary surgery.

The unexpected contingency of COVID‐19 should not compromise the management of a potentially lethal disease like breast cancer. The results of this survey highlight a trend toward reduction of theater lists and outpatient facilities that is escalating across emergency phases. Our survey shows that physicians individually can be reluctant to abandon standards, change surgical priorities, or escape to alternative treatments until operating rooms are not available. However, more restrictions or alternative strategies are accepted as the situation worsens.

Access to cancer therapy should be managed in order to offer a level of care as close as possible to the standards. Now more than ever, multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for treatments on a case‐by‐case basis is highly recommended. Communication between surgical oncologists and health care authorities is largely awaited. Notwithstanding the importance of control measures, breast cancer surgery is not per se resource consuming, and it should be performed even with minimal capacity.

In this context, surgeons and health systems in general are invited to be resilient. This means that every strategy to get the same surgical outcomes should be pursued, waiting times should be used to increase prehabilitation, and observation or use of alternative therapeutic strategies should be performed within randomized trials or under strict surveillance.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Nicola Rocco, Giacomo Montagna, Rosa Di Micco, Giuseppe Catanuto

Provision of study material or patients: Li Chen, Bruno Di Pace, Antonio Jesus Esgueva Colmenarejo, Yves Harder, Andreas Karakatsanis, Marco Mele, Nahid Nafissi, Pedro Santos Ferreira, Wafa Taher, Antonio Tejerina, Alessio Vinci

Collection and/or assembly of data: Nicola Rocco, Giacomo Montagna, Rosa Di Micco, Giuseppe Catanuto, John Russell Benson

Data analysis and interpretation: Nicola Rocco, Giacomo Montagna, Rosa Di Micco, Giuseppe Catanuto, John Russell Benson, Carmen Criscitiello, Maurizio Bruno Nava, Anna Maglia

Manuscript writing: Nicola Rocco, Giacomo Montagna, Rosa Di Micco, Giuseppe Catanuto, John Russell Benson, Carmen Criscitiello, Maurizio Bruno Nava, Li Chen, Bruno Di Pace, Antonio Jesus Esgueva Colmenarejo, Yves Harder, Andreas Karakatsanis, Marco Mele, Nahid Nafissi, Pedro Santos Ferreira, Wafa Taher, Antonio Tejerina, Alessio Vinci

Final approval of manuscript: Nicola Rocco, Giacomo Montagna, Rosa di Micco, John Benson, Carmen Criscitiello, Li Chen, Bruno Di Pace, Antonio Jesus Esgueva Colmenarejo, Yves Harder, Andreas Karakatsanis, Anna Maglia, Marco Mele, Nahid Nafissi, Pedro Santos Ferreira, Wafa Taher, Antonio Tejerina, Alessio Vinci, Maurizio Nava, Giuseppe Catanuto

Disclosures

Carmen Criscitiello: Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Eli Lilly & Co. (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Table S1 American College of Surgeons: COVID‐19 Elective case triage guidelines for surgical care of breast cancer (7).

Table S2. Web‐based poll questions

Table S3. Web‐based poll variables. Grouping of variables for statistical analysis

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. COVID‐19: Global consequences for oncology . Lancet Oncol 2020;21:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID‐19 and Italy: What next? Lancet 2020;395:1225–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell R, Banks C. Emergency departments and the COVID‐19 pandemic: Making the most of limited resources. Emerg Med J 2020;37:258–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID‐19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharma R. Breast cancer incidence, mortality and mortality‐to‐incidence ratio (MIR) are associated with human development, 1990‐2016: Evidence from Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Breast Cancer 2019;26:428–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER et al. Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons. COVID‐19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, March 24, 2020. Available at https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 8. Koo JR, Cook AR, Park M et al. Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 in Singapore: A modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P et al. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID‐19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med 2020;27:taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Group for Reconstructive and Therapeutic Advancements Web site . Available at https://greta.maurizionava.it. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- 11. COVID‐19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University . Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center Web site. Available at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Published 2020. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- 12. Society of Surgical Oncology. Resource for Management Options of Breast Cancer During COVID‐19 . Rosemont, IL: Society of Surgical Oncology, March 30, 2020. Available at https://www.surgonc.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/03/Breast‐Resource‐during‐COVID‐19‐3.30.20.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 13. Association of Breast Surgery . ABS Statement re COVID 19. London, UK: Association of Breast Surgery, March 2020. Available at https://associationofbreastsurgery.org.uk/news/2020/abs-statement-re-covid-19/. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soran A, Gimbel M, Diego E. Breast cancer diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up during COVID‐19 pandemic. Eur J Breast Health 2020;16:86–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al‐Hilli Z, Thomsen KM, Habermann EB et al. Reoperation for complications after lumpectomy and mastectomy for breast cancer from the 2012 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS‐NSQIP). Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22(suppl 3):S459–S469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T et al. Characteristics and outcomes of surgical patients with solid cancers admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA Surg 2018;153:834–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Connell RL, Rattay T, Dave RV et al. The impact of immediate breast reconstruction on the time to delivery of adjuvant therapy: The iBRA‐2 study. Br J Cancer 2019;120:883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van de Haar J, Hoes LR, Coles CE et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID‐19 era. Nat Med 2020;26:665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Italian Society of Surgical Oncology. Raccomandazioni Pratiche della Società Italiana di Chirurgia Oncologica sulla Gestione Chirurgica del Paziente Oncologico Durante la Pandemia COVID‐19. Naples, Italy: Italian Society of Surgical Oncology , 2020. Available at https://www.sicoweb.it/raccomandazioni-sico.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 20. Network National Comprehensive Cancer. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chia YH, Ellis MJ, Ma CX. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in primary breast cancer: Indications and use as a research tool. Br J Cancer 2010;103:759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bergman L, van Dongen JA, van Ooijen B et al. Should tamoxifen be a primary treatment choice for elderly breast cancer patients with locoregional disease? Breast Cancer Res Treat 1995;34:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hind D, Wyld L, Beverley CB et al. Surgery versus primary endocrine therapy for operable primary breast cancer in elderly women (70 years plus). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD004272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dowsett M, Ellis MJ, Dixon JM et al. Evidence‐based guidelines for managing patients with primary ER+ HER2‐ breast cancer deferred from surgery due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. NPJ Breast Cancer 2020;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fontein DB, Charehbili A, Nortier JW et al. Efficacy of six month neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal, hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer patients–a phase II trial. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:2190–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rusz O, Voros A, Varga Z et al. One‐year neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Pathol Oncol Res 2015;21:977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krainick‐Strobel UE, Lichtenegger W, Wallwiener D et al. Neoadjuvant letrozole in postmenopausal estrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive breast cancer: A phase IIb/III trial to investigate optimal duration of preoperative endocrine therapy. BMC Cancer 2008;8:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Francis A, Thomas J, Fallowfield L et al. Addressing overtreatment of screen detected DCIS; the LORIS trial. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2296–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L et al. Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open‐label, international multicentre, phase III, non‐inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ ‐ The LORD study. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1497–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hwang ES, Hyslop T, Lynch T et al. The COMET (Comparison of Operative versus Monitoring and Endocrine Therapy) trial: A phase III randomised controlled clinical trial for low‐risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). BMJ Open 2019;9:e026797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ryser MD, Weaver DL, Zhao F et al. Cancer outcomes in DCIS patients without locoregional treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:952–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Curigliano G, Cardoso MJ, Poortmans P et al. Recommendations for triage, prioritization and treatment of breast cancer patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Breast 2020;52:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ et al.; COVID‐19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020;181:487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bashshur R, Doarn CR, Frenk JM et al. Telemedicine and the COVID‐19 pandemic, lessons for the future. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:571–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Table S1 American College of Surgeons: COVID‐19 Elective case triage guidelines for surgical care of breast cancer (7).

Table S2. Web‐based poll questions

Table S3. Web‐based poll variables. Grouping of variables for statistical analysis