Abstract

Despite several oxides with trivalent cobalt ions are known, the sesquioxide M2O3 with Co3+ ions remains elusive. Our attempts to prepare Co2O3 have failed. However, 50% of Co3+ ions could be substituted for Ln3+ ions in Ln2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) with a cubic bixbyite structure where the Co3+ ions are in the intermediate-spin state. We have therefore examined the structural stability of Co2O3 and the special features of solid solutions (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu). The experimental results are interpreted in the context of ab initio-based density functional theory, molecular dynamics (AIMD), and crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (COHP) analysis. Our AIMD study signifies that Co2O3 in a corundum structure is not stable. COHP analysis shows that there is instability in Co2O3 structures, whereas Co and O have a predominantly bonding character in the bixbyite structure of the solid solution (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3.

1. Introduction

Among the transition metal oxides, cobalt oxides are of special interest because of the existence of cobalt in different oxidation as well as spin states, i.e., low-spin, high-spin, and intermediate-spin states.1 Among these, Co2+ generally has octahedral coordination and is in the high-spin state (t2g5eg, S= 3/2); Co4+ exists in the low-spin state (t2g5eg, S = 1/2). Unlike these two, Co3+ can exist in high-spin (HS, t2g4eg), low-spin (LS, t2g6eg), and intermediate-spin (IS, t2g5eg) states. Existence of the intermediate-spin state arises since the crystal field splitting energy is of the same order as the pairing energy.1,2 Many compounds containing cobalt ions in different oxidation states are known. However, CoO and Co3O4 are the only known binary oxides with Co2+ and Co2+/Co3+ states, respectively.3,4 This is unlike the neighboring Fe, which forms FeO, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4.5 It is somewhat intriguing that it has not been possible to form pure Co2O3. Since many of the transition metal oxides in which metal in the +3 state form sesquioxides in the corundum structure, one would expect Co2O3 to occur in this structure. The only report on Co2O3 is by Chenavas et al.6 who reported a high-pressure synthesis of the oxide with Co3+ in the low-spin state, which transforms to the high-spin state on heating. We have tried to prepare Co2O3 by high-pressure synthesis and other methods and failed to obtain the oxide. In view of this, we sought to investigate (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) solid solutions with composition similar to the LnCoO3 perovskites, wherein it appears to occur in the C-type rare earth oxide structure.

Perovskite oxides of the formula, LnCoO3 (Ln: Y or rare earth) show interesting electronic and magnetic properties. These perovskites are prepared by a solid-state reaction by heating the precursors in air (Ln = Y, La, Pr, Tb, and Dy) under 200 bar oxygen pressure (Ln = Ho, Er) and 20 kbar hydrostatic pressure (Ln = Tm, Yb, and Lu) above 900 °C.7 Some of the heavy rare earths, Ln = Y, Dy, Er, and Yb give rise to a solid solution of Ln2O3 with Co2O3 when the reaction is carried out at lower temperatures (500–600 °C).8 Here, we have carried out a detailed experimental investigation on the bixbyite form of ((Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3) (Ln = Y and Lu) by substituting Ln2O3 by 50% Co where cobalt exists in a trivalent state. Our experimental results are well supported with the theoretical approach using the first principle-based DFT calculations and AIMD simulations.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Experimental Studies

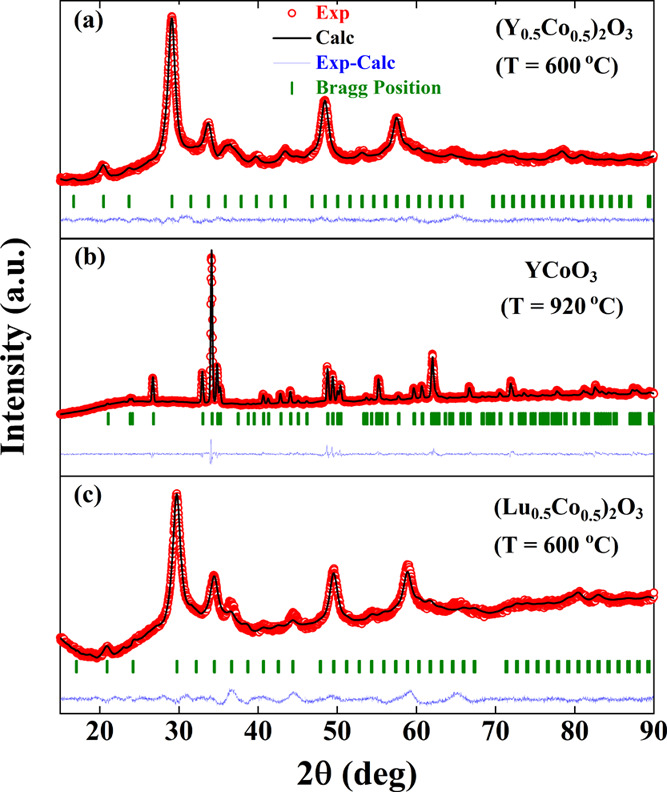

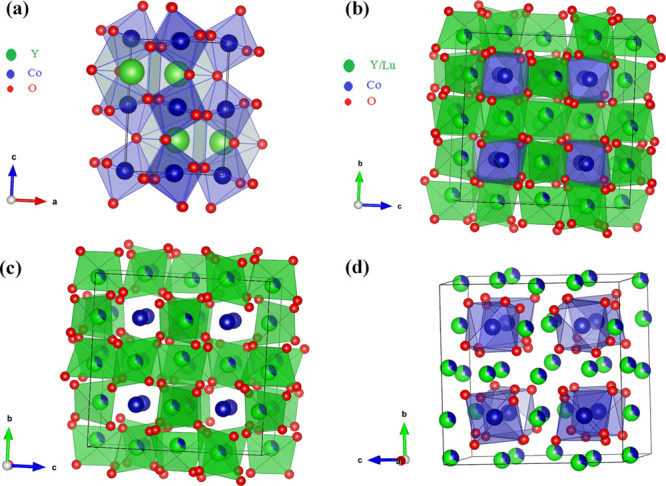

All our attempts to prepare Co2O3 have resulted in the formation of CoO and Co3O4 phases with no traces of the Co2O3 phase. We have therefore examined the structural aspects of Co2O3 present in the solid solution (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu). Rietveld refined powder X-ray diffraction profiles of (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 at two different temperatures (600 and 920 °C) and (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 at 600 °C are shown in Figure 1a, b, and c, respectively. XRD profiles fitted using the pseudo-Voigt function revealed that both solid solutions prepared at 600 °C crystallize in the cubic bixbyite structure with an Ia3̅ space group. Heating a (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 solid solution to 920 °C in oxygen gave rise to perovskite YCoO3 crystallizing in orthorhombic symmetry with a Pbnm space group, and the corresponding crystal structure is shown in the Figure 2a. Unlike (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3, a (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 solid solution at 800 °C decomposed into cubic Lu2O3 and Co3O4 phases. Refined structural parameters for perovskite YCoO3 and solid solutions, (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) are given in the Table 1. The crystal structure of YCoO3 consists of distorted CoO6 octahedra where Co is situated at the center surrounded by six oxygen ions. Oxygen occupies two different sites in the crystal structure. Y resides in the voids created by the surrounding CoO6 octahedra.9

Figure 1.

Rietveld refined X-ray diffraction profiles of (a) (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 (600 °C), (b)YCoO3 (920°C), and (c) (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 (600 °C).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of (a) perovskite YCoO3 (b) bixbyite (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu), (c) octahedra of Y/Lu (green colored) in (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3(Ln = Y and Lu), and (d) highlighted (blue colored) CoO6 octahedra.

Table 1. Structural Parameters Obtained by Rietveld Refined XRD for YCoO3and (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3(Ln = Y and Lu).

| compound | space group : Pbnm (orthorhombic); α = β= γ = 90° |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a = 5.14519(22), b = 5.42765(24), c = 7.37531(33) Å;

χ2 = 3.2% | |||||

| YCoO3 | x | y | z | Biso | Occ. |

| Y (4c) | –0.0157(6) | –0.0678(3) | 0.25 | 0.028(16) | 1.0 |

| Co (4b) | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.158(11) | 1.0 |

| O1 (4c) | 0.0970(18) | 0.5229(17) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| O2 (8d) | –0.1918(15) | 0.1996(15) | 0.0479(11) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| space group : Ia3̅ (cubic); α

= β= γ = 90° |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a = b = c = 10.6303(12)

Å; χ2 = 1.72% |

|||||

| (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 | x | y | z | Biso | Occ. |

| Y (24d) | –0.0271(1) | 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.422(32) | 0.333 |

| Co1 (24d) | –0.0271(1) | 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.422(32) | 0.167 |

| Co2 (8b) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.471(28) | 0.167 |

| O (48e) | 0.3962(8) | 0.1550(6) | 0.3812(9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

|

a = b = c = 10.3916(18)

Å;

χ2 = 3.1% |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 | x | y | z | Biso | Occ. |

| Lu (24d) | –0.02537(2) | 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.183(1) | 0.333 |

| Co1 (24d) | –0.02537(2) | 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.183(1) | 0.167 |

| Co2 (8b) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.164(1) | 0.167 |

| O (48e) | 0.4086(11) | 0.1506(12) | 0.3484(19) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

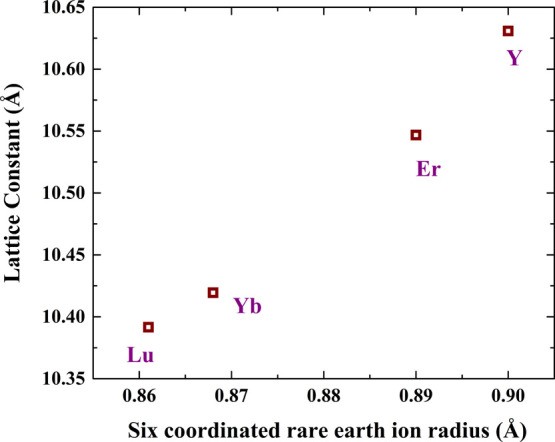

The crystal structure of solid solutions (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) is shown in the Figure 2b, which consists of two octahedral cation sites where eight Co atoms occupy 8b and other eight occupy 24d Wyckoff site, whereas Y or Lu occupies 24d Wyckoff sites. The octahedra LnO6 (Ln = Y and Lu) and CoO6 are highlighted in Figure 2c and d, respectively. The lattice constants of different cubic (C-type) (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y, Er, Yb, and Lu) solid solutions were plotted against corresponding lanthanide radii as shown in Figure 3. The lattice parameters of (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Er and Yb) are taken from ref (8). The linear nature of the plot confirms that the system follows Vegard’s law,10 which is attributed to the contraction of the unit cell of the (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 solid solution with decreasing size of lanthanide ions. Being the smallest lanthanide, Lu3+ forms a unit cell of volume, V ∼ 1122.2 Å3, which is 7% smaller than that of Y.

Figure 3.

Variation of lattice parameters of (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y, Er, Yb, and Lu) solid solutions with Ln3+ radius.

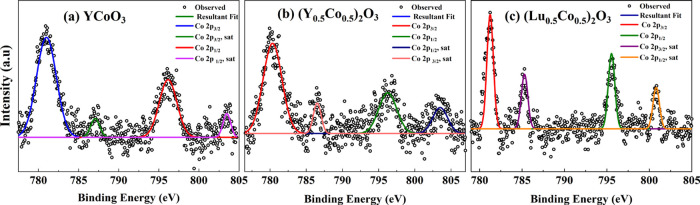

Our XPS study reveals the oxidation state of cobalt in perovskite YCoO3 as well as (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) solid solutions. The core level spectra of cobalt for YCoO3 and (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) are shown in Figure 4. The four signals due to cobalt in Figure 4a–c, correspond to energy levels Co 2p3/2, Co 2p1/2, and their satellites confirming the presence of trivalent cobalt ions.11

Figure 4.

Co 2p core level XPS spectra of (a) YCoO3, (b) (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3, and (c) (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3.

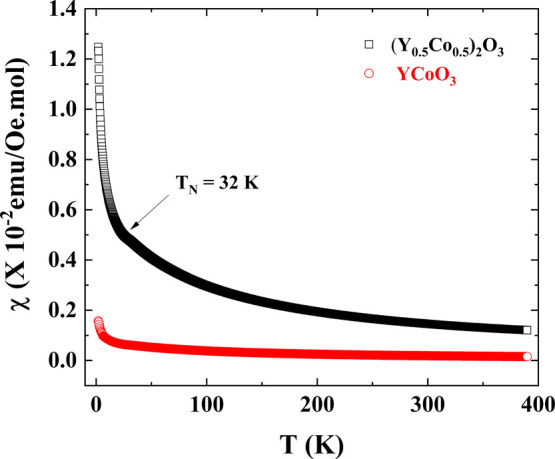

The temperature-dependent field-cooled (FC) magnetic susceptibility for YCoO3 and (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 was measured under an applied DC field of 100 Oe in the temperature range 2–390 K as shown in Figure 5. We find that perovskite YCoO3 shows a low-spin state (t2g6eg) from low temperature 2 to 390 K. (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 on the other hand shows an intermediate-spin state (t2g5eg) with μeff ∼ 2.13 μB. Spin state transitions of trivalent cobalt is well known in the perovskites LnCoO3 (Ln = La, Y, Pr, Nd, and Eu).12−14 Anomaly observed at TN ∼ 32 K in the magnetic susceptibility curve of (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 is attributed to antiferromagnetic ordering of Co3+ ions, which is further evidenced by a negative θCW value (Table 2). Similarly, (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 shows antiferromagnetic ordering below TN ∼ 25 K with μeff ∼ 2.68 μB, indicating the existence of Co3+ in the intermediate-spin state (t2g5eg).

Figure 5.

Comparative temperature-dependent field-cooled (FC) magnetic susceptibility curves of (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 and YCoO3 perovskites.

Table 2. μeff and θCW Values for (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 and (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3.

| (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 |

(Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μeff | θCW | μeff | θCW | |

| Ambient pressure | 2.13 μB | –91 K | 2.68 μB | –90 K |

| High pressure (1.5 GPa) | 2.84 μB | –93 K | 2.79 μB | –82 K |

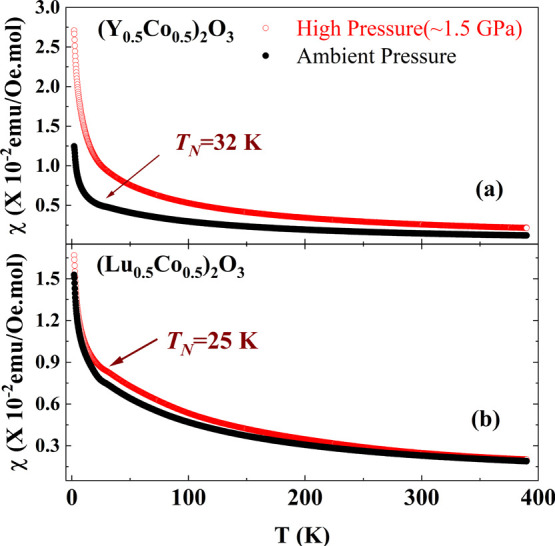

To explore the effect of pressure on the magnetic interaction of Co3+ ions in these solid solutions of Co2O3, a high pressure (1.5 GPa) was applied on (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) at room temperature for 1 hr, and the magnetic susceptibilities of the so-obtained (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 are compared with that of ambient pressure samples as shown in Figure 6a,b. There is no change observed in the phase of the high-pressure treated samples, and their XRD profiles are shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information).

Figure 6.

Comparative temperature-dependent field-cooled (FC) magnetic susceptibility curves of (a) (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 and (b) (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 synthesized in ambient pressure and high pressure (1.5 GPa).

Temperature-dependent inverse magnetic susceptibility is fitted using the Curie–Weiss law for ambient and high-pressure samples of (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) and are shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information). μeff and θCW values for (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) for ambient pressure and high-pressure treated samples are listed in Table 2. Even though Co3+ ions are existing in the intermediate-spin state in both the (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) solid solutions, (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3 has a high effective magnetic moment than that of (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3. This is attributed to the chemical pressure due to Lu3+ ions. On the other hand, external pressure increases the μeff in both the solid solutions and is more significant in (Y0.5Co0.5)2O3 than (Lu0.5Co0.5)2O3.

2.2. Theoretical Studies

Ab initio-based density functional theory (DFT) methods have become well-established techniques to study structural and chemical properties of various materials. Our computational methodology provides comprehensive understanding related to the structural stability and chemical bonding analysis of a well-known Al2O3 corundum structure followed by hypothetical Co2O3 crystal in the corundum phase. In order to further investigate the chemical aspects of Co3+ ions in the chemical environment, we study the bonding characteristics of Y2O3 with different doping concentrations of Co3+ ions. Our theoretical analysis based on first principles calculation supported by experimental findings will be discussed to interpret structural stability and chemical aspects more rigorously.

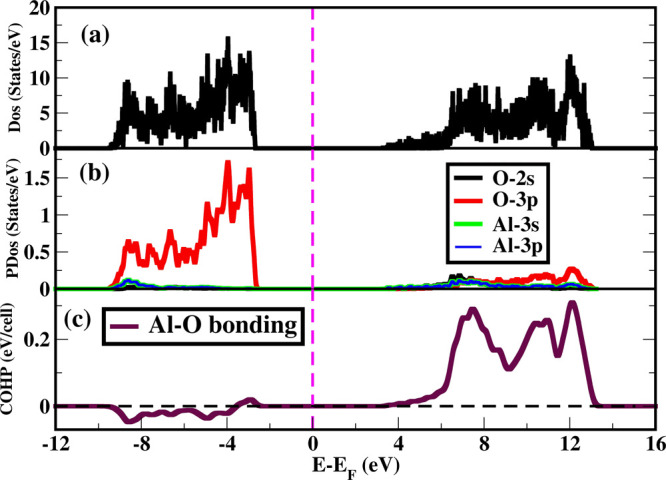

2.2.1. Al2O3

In the optimized structure of Al2O3, the DOS and the PDOS have been calculated (Figure 7a,b). From the DOS plot, it is clear that Al2O3 is an insulator with a DFT band gap of 3.4 eV. From the projected DOS, we find that interestingly the low-energy valence bands are dominated exclusively by the oxygen 3p orbitals with very small electronic contributions from Al orbitals. On the other hand, low-energy conduction bands remain almost empty and only at some high energy, it has small contributions from both the Al and O atomic orbitals. Moreover, we emphasize that the lack of overlap between Al and O orbitals in the valence band lead to very small orbital overlapping and less degree of covalence. In contrast, the charge transfer mechanism effectively dominates to form ionic bonds between Al and O atoms in stabilizing Al2O3 crystals in the corundum phase.

Figure 7.

(a) Density of states (DOS) of Al2O3; (b) projected DOS on relevant orbitals; (c) COHP is shown as a function of energy for the Al–O bond. PDOS indicates less orbital overlapping between Al and O atoms below the Fermi level although there is significant orbital overlapping above the Fermi level. Negative value of COHP below the Fermi level shows that Al2O3 is electronically stable. In figures, Fermi levels are considered as a reference.

To further understand the bonding characteristics, we study crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (COHP)15 analysis between Al and O orbitals (Figure 7c). The COHP is described as the negative of DOS multiplied by the corresponding Hamiltonian matrix elements. The negative and positive values of COHP suggest bonding and antibonding interaction between the electronic states, respectively. The negative value of COHP indicates bonding interactions between Al 3s–Al 3p and O 2p orbitals in the valence bands, which stabilizes the corundum structure of Al2O3.

2.2.2. Co2O3

To understand why there is no stable structure of Co2O3, we have carried out a series of optimizations of the corundum structures of Cr2O3 and Fe2O3 and obtained the M–M and M–O distances. Interestingly, in relaxed crystal structures of all of these oxides, there is no direct M–M bond. In fact, the distances between M–M are 2.60 Å (2.66 Å) and 2.93 Å (2.88 Å), respectively (the numbers in brackets are distances obtained from experiments). Expectedly, we find that all these oxides in their 3+ state show a high spin atomic ground state with varying magnetic moments and antiferromagnetic orders as found experimentally.

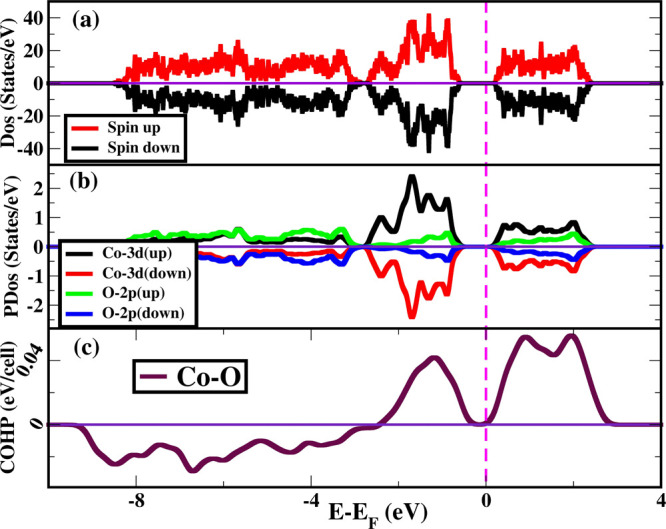

We started the optimization studies with the corundum structure of the Fe2O3 and substituted Fe atoms with Co atoms. The crystal structure has been relaxed using a fully variable cell and BFGS algorithm, and we find that Co3+ forms a low-spin atomic ground state with t2g6eg configuration. The relaxed (but unstable) structure shows that the distance between two Co atoms decreases compared to the Fe–Fe distance in the Fe2O3 corundum structure. The shorter Co–Co distance introduces strain in the system due to the repulsive e–e interaction between two octahedra. Because of the shorter distance between the Co atoms, bonding characteristics between Co and O atoms get influenced quite strongly. As a result, the bond length between Co and O decreases considerably (much shorter compared to other M–O bonds (Table 3) that leads to the large crystal field octahedral gap leading to S = 0 ground state for Co3+ ions. Our electronic density of states (Figure 8a) confirms that Co2O3 forms low-spin states. Energy levels below Fermi level spread from −8 to 0 eV, and the conduction bands spread from 0.6 to 2.5 eV. We also calculated projected density of states (PDOS) of Co 3d orbitals and O 2p orbitals in Figure 8b. From PDOS calculations, it is confirmed that there is significant orbital overlapping between Co 3d and O 2p orbitals in the valence band as well as in the conduction band.

Table 3. M–M and M–O Bond Length for the M2O3 Given Below for Antiferromagnetic Crystal Structure and Compared with the Experimental Value.

Figure 8.

(a) Electronic density of states of spin-up (red) and spin-down (black) of the relaxed but unstable crystal structure of Co2O3. Here, zero energy level is considered as Fermi level. (b) Projected density of states of Co 3d and O 2p orbitals where states above the x axis are the contribution from spin up states, and states below is the contribution from spin down states. (c) Crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (COHP) of a Co–O bond (Co:4s Co:3d and O:2s O:2p).

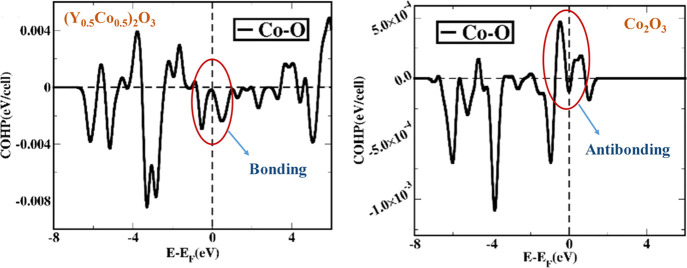

The COHP has been plotted in Figure 8c, where we have considered strong interaction between Co:4s, Co:3d and O:2s, O:2p in the unstable relaxed structure of Co2O3. Our results show that COHP value is positive near the Fermi level, which signifies that the strong interaction between Co:4s, Co:3d and O:2s, O:2p are antibonding in nature below and above the Fermi level. Interestingly, the interaction between Co and O are antibonding from −2.5 to −0.4 eV in the valence band and from 0.2 to 3 eV in the conduction band, suggesting that Co2O3 is least favorable in corundum or any other structure unlike other transition metal oxides (Fe2O3, V2O3, and Cr2O3). Antibonding nature of Co:4s, Co:3d and O:2s, O:2p partly destabilizes the structure of Co2O3. Interestingly, due to such partially destabilized bonding, the octahedral crystal field gives complete filling of t2g6 electrons with no unpaired electrons in Co3+ for bonding. Also, since 3d orbitals form narrow band semiconductors, this leads to such a small and almost overlapping bond distance between two octahedral Co ions, where we find highly unstable phonon modes (shown in Figure 9). Unstable phonon modes that are characterized by negative values of the frequencies in a phonon dispersion curve at any wave vector leads to dynamical instability in the crystal structure.

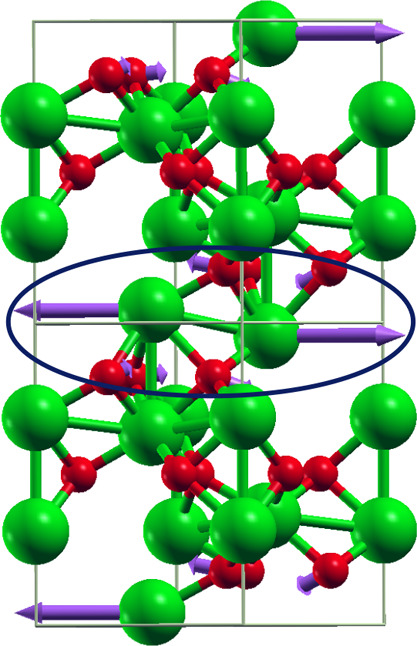

Figure 9.

Unstable relaxed corundum crystal structure of Co2O3 is calculated using PBE functional. Here, ‘green’ color balls represent Co atoms and ‘red’ color balls represent oxygen atoms. Purple arrows in a circle indicate unstable phonon mode of frequency −51 cm–1, which has been obtained performing phonon mode calculations through DFPT at Γ (Gamma) point.

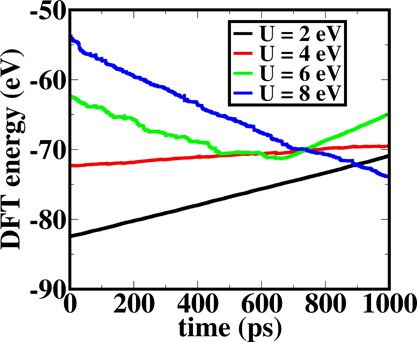

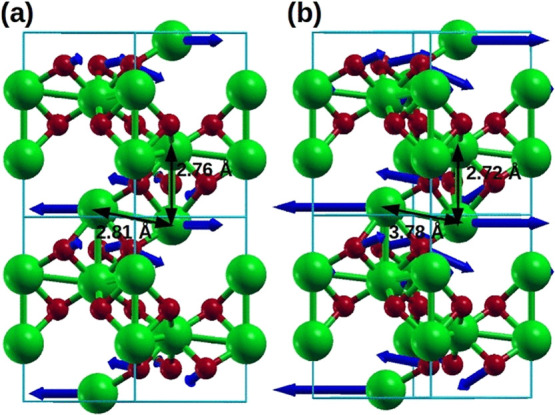

We have also performed ab initio molecular dynamics17,18 study considering different U values to find the structural stability of a Co2O3 crystal. In the simulation, we have plotted DFT energies or electronic energies for different values of U (U = 2, 4, 6, and 8 eV) up to 1000 ps and that have been shown in Figure 10. Interestingly, we find that DFT energies obtained using AIMD studies show considerable drift during the AIMD time steps. The drift in the DFT energies corresponding to different U values would certainly lead to structural instability of the Co2O3 corundum structure. To find the microscopic reasons for the structural instability, we have further analyzed the vibrational spectra of the system after 70 ps of AIMD run. These have been analyzed from the dynamical matrix of the force constants. Interestingly, we observe negative phonon mode at the high symmetry Γ point, which suggest that the Co2O3 corundum structure is unstable due to constrained geometry of the two octahedra wherein the two corner sharing Co3+ ions come at a distance of 2.78 Å. The structure without external pressure and with external pressure (80 kbar) are shown in Figure 11a,b, respectively, where we have marked the unstable phonon modes and the constrained geometry.

Figure 10.

DFT energies have been plotted considering different U values as a function of AIMD time steps. Our computed plot shows significant drift, which further signifies that a Co2O3 corundum crystal structure remains unstable for different values of U.

Figure 11.

(a) Co2O3 crystal structure without external pressure and (b) Co2O3 crystal structure with external pressure. Due to applied hydrostatic external pressure on the unit cell, Co–Co distances along the c axis and along in-plane directions decreases as shown in Figure 11b. Blue arrows shown in the figure indicate unstable phonon modes, and the length of the arrows signifies the amount of force acting on the individual atoms introducing dynamical instability.

2.2.3. Y2O3

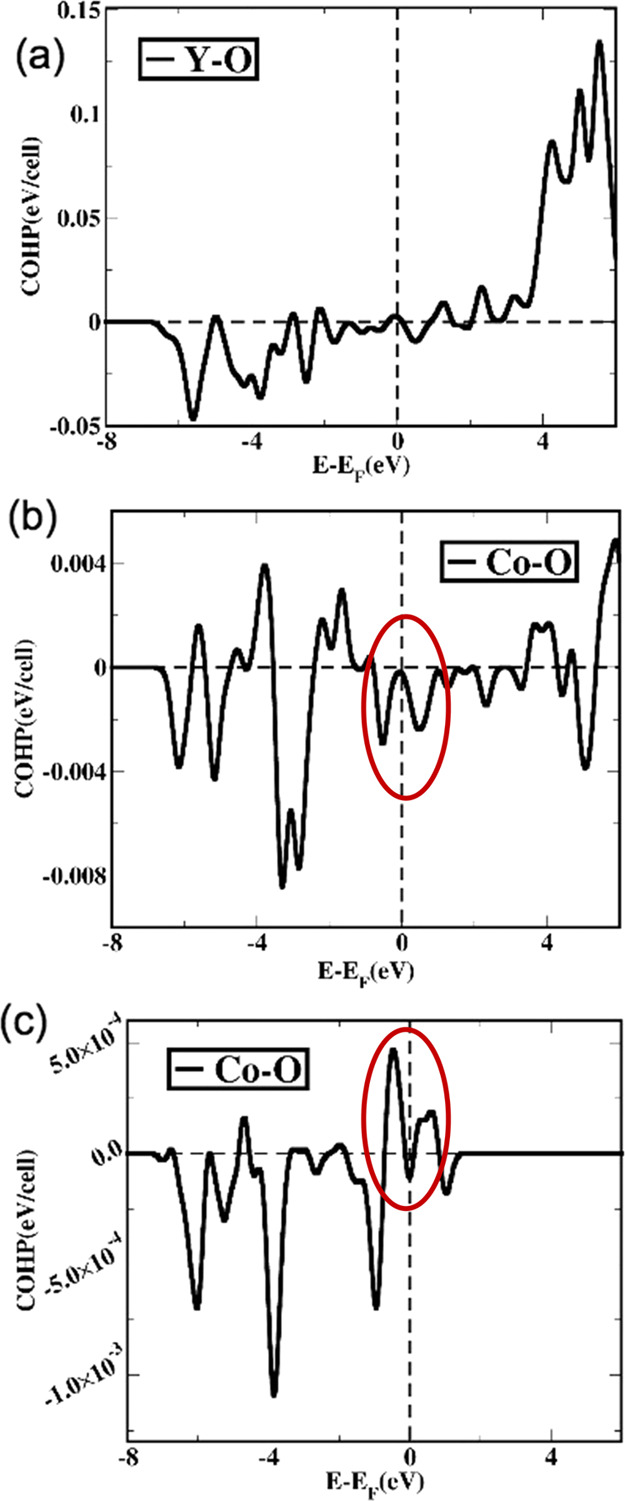

To elucidate microscopic reasons more rigorously, we consider Y2O3 unit cell in the cubic bixbyite structure. The unit cell contains 80 atoms (32 Y atoms and 48 O atoms). We notice that all of the crystallographic sites corresponding to Y atoms are not equivalent. There are 8 numbers of Y atoms (b sites) and 24 numbers of Y atoms (d sites). In the b site, Y atoms are present in the octahedral symmetry, and in the d site, Y atoms are placed in distorted octahedral symmetry. After optimizing the crystal, we perform electronic structure calculations and compute COHP for Y–O bonds. After that, we substitute 50% of Y with Co atoms and optimize the structure. Interestingly, we find that Co occupies eight numbers of b sites and eight numbers of d sites that are energetically favorable. As a result, 50% Co-doped Y2O3 stabilizes the crystal in the cubic form. The stability of 50% Co-doped Y2O3 has also been confirmed by COHP analysis and experiments.

Presence of bonding between Y–O orbitals (negative value of COHP in the valence band region) implies that the Y2O3 crystal structure is electronically stable) shown in Figure 12a. On the other hand, 50% of Co-doping in Y2O3 introduces that Co–O orbital interactions are bonding in nature near the Fermi level in the valence band, and it leads to a stable 50% Co-doped Y2O3 structure. In the special case, when we replace all the Y atoms by Co atoms in the Y2O3 cubic structure, we find the positive value of COHP close to the Fermi level in the valence band region, and the bonding characteristics are highly antibonding in nature, which essentially partly destabilizes the crystal. Experimentally, it has also been found that the Y2O3 crystal with all Y atoms doped by Co atoms is not stable. Finally, to quantify the degree of structural stability, we have tabulated ICOHP values for different orbitals and shown in Table S3 (Supporting Information). Such analysis would help to compare the bonding strength between the orbitals and determine the structural stability for different materials considered in this work.

Figure 12.

(a) COHP of cubic Y2O3 has been mentioned. Negative COHP values between Y and O atomic orbitals imply that the Y2O3 crystal stabilizes in a cubic form. (b) COHP after the insertion of Co (50%) in place of Y atoms in Y2O3. (c) COHP has been calculated for the cubic phase of Y2O3 with all the Y atoms replaced by Co atoms.

We have also calculated the magnetic moments of individual Co atoms and find that Co ions in different crystallographic sites have different magnetic moments due to the difference in symmetry leading to crystal field splitting. Interestingly, we find the total number of unpaired spins of Co in a site and b site to be 2.2 and 1.92 μB, respectively. Experimentally, it has been found that Co has an intermediate-spin state with a spin-only value, 2.13 μB. The main point in the overall studies involving experimental and computational results is that Co2O3 with 3d6 Co3+ ions with S = 0 neither stabilizes in corundum nor in cubic form, while other systems with S = 0 (Y3+: 4d0 and Al3+: valence orbitals are 3s and 3p) stabilize in cubic and corundum crystal respectively, which is highly significant.

3. Conclusions

Based on the studies, it seems apparent that Co2O3 itself does not exist but forms stable solid solutions with Y2O3 and Lu2O3 in the cubic bixbyite structure. The solid solutions are formed at lower temperatures than the perovskites Y(Lu)CoO3. Co3+ ions in the solid solution are in the intermediate-spin state. The difficulty with Co2O3, unlike sesquioxides of other transition metals, is that interactions between Co:4s–Co:3d and O:2s–O:2p are antibonding in nature in the corundum structure, while it essentially has a bonding character in the bixbyite structure. This finding would be of interest in understanding the chemistry of transition metal oxides.

4. Experimental and Theoretical Methods

4.1. Synthesis and Characterization

We have attempted to synthesize Co2O3 at high pressures and temperatures using different precursors. In the first attempt, LiCoO2 and CoF3 were mixed and heated to high temperatures (900–1000°C) under high pressure (4.5 GPa). Again, the reaction was carried out using the precursor mixture of CoO and KClO3 under high pressure and temperature. Solid solutions of (Ln0.5Co0.5)2O3 (Ln = Y and Lu) were prepared by nitrate–citrate sol–gel combustion method as mentioned in a report8 in which lanthanide nitrate, cobalt nitrate, and citric acid in 1:1:10 stoichiometric ratio were dissolved in distilled water. This solution was heated to 80 °C with constant stirring until it forms a gel. The obtained gel was heated in an oven at 200°C for 12 h to give rise to a porous powder, which was later heated at 600 °C for 12 h in oxygen to remove carbonaceous content.

The phase purity was confirmed by carrying out X-ray diffraction measurements using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer where the sample was subjected to Cu Kα radiation in the range of Bragg angle (10° ≤ 2θ≤ 120°) under θ-2θ scan. XRD data have been analyzed by the Rietveld method19 using FullProf Suite software.20 X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were recorded using an Omicron Nanotechnology spectrometer with a monochromatic Mg Kα radiation as the X-ray source with energy E = 1253.6 eV. All the individual core level spectra are corrected using the C 1s level signal (284.6 eV). Cubic multianvil high-pressure apparatus was used to apply high pressure on polycrystalline powder of solid solutions. The pressure on the sample was increased to 1.5 GPa and maintained for 1 h at room temperature. DC magnetic measurements are done in SQUID VSM (Quantum Design, USA) in vibrating sample mode.

4.2. Theoretical Calculations

First principle-based density functional theory (DFT), as implemented in the Quantum Espresso package, has been used to calculate electronic structure properties. Projected augmented plane wave21 and a generalized gradient approximated (GGA) exchange–correlation energy22 with parameterized functional of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) are used. An energy cutoff of 50 Ry to truncate the plane wave basis states in representing the Kohn–Sham wave functions and an energy cutoff of 500 Ry for the basis states to represent charge density are used. The crystal structures are fully relaxed using the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) algorithm technique to minimize the energy until the magnitude of Hellman–Feynman force on each atom is less than 0.025 eV/Å. A uniform grid of 12 × 12 × 6 k-mesh in the Brillouin zone was used for relaxing the corundum crystal structure of M2O3. To include the effect of Coulomb interaction beyond GGA at transition metal sites, we consider GGA + U correction in Hamiltonian. Moreover, to incorporate the effect of Hubbard U in the calculation, we executed variable cell relaxation with different U values. After full relaxation of the crystal structure, we performed self-consistent calculations with the final optimized crystal coordinates. Besides, we have also studied density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)23 to calculate phonon modes at the zone center Gamma point to confirm the dynamical stability. We adopt U = 3.5 eV for our calculations, which is taken from the previous studies of a similar crystal structure.24,25 To justify the selection of U, we have also tested our calculations for other various U values (U = 2, 4, 6, and 8). Interestingly, we observe that although the magnitude of phonon eigenvalues varies with different U values, a few of the phonon eigenvalues still remain negative [shown in Table S1]. Negative eigenvalue of phonon signifies that the crystal structure is unstable with regards to small perturbation of atoms along the crystallographic directions. We have also analyzed the phonon eigenvectors associated with each eigenvalue for different U values. The imaginary eigenvectors do not show any drastic change in their directions, and the overall nature of phonons do not change with U values. Furthermore, we have plotted COHP for various U values to analyze bonding characteristics for better understanding of realistic chemical bonding picture in the framework of COHP methodology [shown in Table S2]. We find that there is no significant variation in COHP for different U values. In fact, we find an appearance of unstable antibonding characteristics in COHP below the Fermi level. The “degree of bonding” or bonding strength has been computed by integrating the COHP values below the Fermi level from −5.0 eV to Fermi energy (at 0.0 eV; all energy are scaled). The “degree of bonding” also suggests that with the increase in electronic correlations, the corundum structure becomes more and more unstable.

To further investigate the effect of external pressure at room temperature as well as at higher temperature, we perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) as implemented in Vienna ab initio package (VASP).26,27 The plane wave basis set, scalar relativistic pseudopotentials, and projected augmented wave (PAW)28 methods were employed for molecular dynamics simulations. The Nose–Hoover thermostat and barostat29,30 were used to evaluate the equilibrium dynamics under the NPT ensemble. Equilibrium dynamics were maintained for 1000 ps with a time step of 1 fs after the equilibrium spanning of the first 20 ps. We also consider Y2O3 unit cell in cubic form and optimize the structure using the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shannon (BFGS) algorithm to minimize the energy until the magnitude of Hellman–Feynman force on each atom is less than 0.025 eV/Å. We consider similar exchange–correlation functional as have been taken for the Co2O3 corundum structure with a uniform grid of 6 × 6 × 6 k-mesh and an energy cutoff of 50 Ry.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the International Centre for Materials Science and Sheikh Saqr Laboratory at Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research for providing experimental facilities. A.S. acknowledges, SERB, DST, and the government of India for financial support. P.N.S acknowledges Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research for providing a research fellowship (JNC/S0484). R. K. B. thanks the UGC and the government of India, and S. K. P. acknowledges SERB, DST, and the government. of India for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03397.

Additional results including X-ray diffraction profiles of high-pressure treated samples and temperature-dependent inverse magnetic susceptibility curves fitted with the Curie–Weiss law, variation of phonon eigenvalues at Γ point as a function of Hubbard U, variation of integrated COHP (ICOHP)1-2 for Co–O bonding with the increasing values of Hubbard U, and integrated COHP (ICOHP) in eV/atoms for different materials (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Raveau B.; Seikh M., Cobalt oxides: from crystal chemistry to physics ;John Wiley & Sons: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa S.; Tohyama T.; Barnes S. E.; Ishihara S.; Koshibae W.; Khaliullin G., Physics of transition metal oxides. Springer Science & Business Media: 2013; Vol. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Tombs N. C.; Rooksby H. P. Structure of monoxides of some transition elements at low temperatures. Nature 1950, 165, 442. 10.1038/165442b0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roth W. The magnetic structure of Co3O4. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1964, 25, 1–10. 10.1016/0022-3697(64)90156-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell R. M.; Schwertmann U., The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses; John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chenavas J.; Joubert J. C.; Marezio M. Low-spin to high-spin state transition in high pressure cobalt sesquioxide. Solid State Commun. 1971, 9, 1057–1060. 10.1016/0038-1098(71)90462-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. A.; Martínez-Lope M. J.; de La Calle C.; Pomjakushin V. Preparation and structural study from neutron diffraction data of RCoO3 (R= Pr, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu) perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 1555–1560. 10.1039/B515607F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu B. S.; Gupta U.; Maitra U.; Rao C. N. R. Visible light induced oxidation of water by rare earth manganites, cobaltites and related oxides. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 591, 277–281. 10.1016/j.cplett.2013.10.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A.; Berliner R.; Smith R. W. The structure of yttrium cobaltate from neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 1997, 130, 192–198. 10.1006/jssc.1997.7279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denton A. R.; Ashcroft N. W. Vegard’s law. Phys. Rev.A 1991, 43, 3161. 10.1103/PhysRevA.43.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumkin A. V.; Kraut-Vass A.; Gaarenstroom S. W.; Powell C. J., NIST X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy database, NIST standard reference database 20, version 4.1. US Department of Commerce,Washington: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Knížek K.; Jirák Z.; Hejtmánek J.; Veverka M.; Maryško M.; Hauback B. C.; Fjellvåg H. Structure and physical properties of YCoO3 at temperatures up to 1000 K. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 214443. 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.214443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. N. R.; Seikh M. M.; Narayana C., Spin-state transition in LaCoO3 and related materials. In Spin Crossover in Transition Metal Compounds II; Springer: 2004; pp. 1–21, 10.1007/b95410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berggold K.; Kriener M.; Becker P.; Benomar M.; Reuther M.; Zobel C.; Lorenz T. Anomalous expansion and phonon damping due to the Co spin-state transition in R CoO3 (R= La, Pr, Nd, and Eu). Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 134402. 10.1103/PhysRevB.78.134402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deringer V. L.; Tchougréeff A. L.; Dronskowski R. Crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 5461–5466. 10.1021/jp202489s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger L. W.; Hazen R. M. Crystal structure and isothermal compression of Fe2O3, Cr2O3, and V2O3 to 50 kbars. J. Appl. Phys. 1980, 51, 5362–5367. 10.1063/1.327451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner J. Materials simulations using VASP—a quantum perspective to materials science. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2007, 177, 6–13. 10.1016/j.cpc.2007.02.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 2044–2078. 10.1002/jcc.21057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld H. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71. 10.1107/S0021889869006558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal J., Recent developments of the program FULLPROF. Commission on powder diffraction (IUCr) ;Newsletter; 2001,26, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953. 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroni S.; De Gironcoli S.; Dal Corso A.; Giannozzi P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 515. 10.1103/RevModPhys.73.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C.; Lei Y.; Wang G. Charged vacancy diffusion in chromium oxide crystal: DFT and DFT+ U predictions. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 215101. 10.1063/1.4970882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Ramadugu S. K.; Mason S. E. Surface-specific DFT+ U approach applied to α-Fe2O3 (0001). J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 4919–4930. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b12144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558–561. 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Hafner J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal--amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251–14269. 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nosé S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 511–519. 10.1063/1.447334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. Canonical dynamics: method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Phys. Rev. A 1985, 31, 1695–1697. 10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.