Abstract

Background & Aims:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is associated with significant disease burden and decreased quality of life (QOL). We investigated the effects of IBS on different areas of daily function and compared these among disease subtypes.

Methods:

The Life with IBS survey was conducted by Gfk Public Affairs & Corporate Communications from September through October 2015. Respondents met Rome III criteria for constipation-predominant or diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-C and IBS-D, respectively). Data were collected from 3254 individuals (mean age, 47 years; 81% female; and 90% Caucasian) who met IBS criteria.

Results:

Respondents who were employed or in school (n=1885) reported that IBS symptoms affected their productivity an average of 8.0 days out of the month and they missed approximately 1.5 days of work/school per month because of IBS. More than half the individuals reported that their symptoms were very bothersome. Individuals with IBS-C were more likely than with IBS-D to report avoiding sex, difficulty concentrating, and feeling self-conscious. Individuals with IBS-D reported more avoidance of places without bathrooms, difficulty making plans, avoiding leaving the house, and reluctance to travel. These differences remained when controlling for symptom bothersomeness, age, sex, and employment status. In exchange for 1 month of relief from IBS, more than half of the sample reported they would be willing to give up caffeine or alcohol, 40% would give up sex, 24.5% would give up cell phones, and 21.5% would give up the internet for 1 month.

Conclusions:

Although the perceived effects of IBS symptoms on productivity are similar among its subtypes, patients with IBS-C and IBS-D report differences in specific areas of daily function.

Keywords: abdominal pain, daily living, absenteeism, presenteeism

Introduction

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is associated with significant disease burden. Many studies have documented decreased quality of life1-3, elevated rates of psychological comorbidities4,5, and high economic costs associated with IBS6. For example, patients with IBS have been reported to have worse health-related quality of life than patients with diabetes or end-stage renal disease1 and up to 38% of individuals with IBS report having contemplated suicide as a result of their symptoms7.

The impact of IBS on daily functioning has been quantified primarily in studies of workplace absenteeism and presenteeism (lost productivity at work). In a survey mailed to households in the United States, individuals with IBS reported missing an average of 13.4 days of work or school per year, compared to 4.9 days for those without IBS8. A recent survey study reported that 24% of respondents had missed work in the last week due to IBS symptoms and 87% had experienced reduced productivity at work in the same time period9. Another study has estimated nearly 14 hours per week of lost productivity due to IBS in a 40-hour work week10.

Only a small number of studies have evaluated the impact of IBS on other aspects of daily living such as social interactions, relationships with friends/family, and activities outside the home. The first to report the impact of IBS across domains of daily living was a survey of 42 patients seen in tertiary care facilities, which outlined avoidance of activities such as exercise, work, household chores, socializing, travel, leisure, eating, and sexual intercourse11. That study reported that IBS patients were significantly more likely to avoid daily activities when symptoms were present, with over 40% of the sample reporting avoidance in each category when symptomatic. Another study using an online research survey of individuals in the community meeting Rome III criteria for IBS found that over 50% of the sample reported impairment in each domain of daily living, with higher rates of impairment reported by individuals who also met criteria for depression, anxiety, or panic disorders12. Two large survey studies, one in the United States and one in Europe, measuring the impact of IBS on daily life also reported high rates of impairment in domains such as eating outside the home, going out with friends, traveling, and going to new or unfamiliar places13,14. However, these studies have not distinguished between IBS subtypes. Only one prior study has approximated differences in impairment between IBS subtypes using subscales of a validated quality of life (QOL) questionnaire 15. That study reported lower overall QOL in diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D [n=56]) compared to constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C [n=54]), with significantly lower average scores in food avoidance, social reaction, and relationships subscales in IBS-D. However, no study to date has compared impairment of specific daily activities in IBS subtypes using a large, nationwide sample of individuals in the community with IBS-C and IBS-D.

Methods

Study survey

Data from the “Life with IBS” survey was analyzed for this research study. This was an online (emailed) survey conducted for the American Gastroenterological Association by GfK Public Affairs & Corporate Communications (GfK) with the financial support of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Allergan plc. in September and October of 2015. The objective of the survey was to explore the attitudes of IBS sufferers, and to better understand their experiences living with IBS. Participants were recruited from a national sample (all 50 states) of Gfk ‘s large database of individuals in the United States. At initial recruitment into the database, participants provide information about their habits, health conditions, and other areas of interest, which is then used to select individuals for specific surveys. Gfk provides a modest incentive as well as opportunities to enter raffles and sweepstakes in order to encourage participation in their surveys and to foster member loyalty. Members receive approximately 1 emailed survey per week related to a variety of topics, with email and telephone reminders if the survey is not completed. Detailed information about GfK’s survey methodology is available elsewhere16.

To be considered eligible for this study, respondents had to meet Rome III criteria for IBS-C or IBS-D. Respondents were excluded if they met criteria for IBS-M, or if they reported having been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, colon cancer, stomach cancer or other cancer of the gastrointestinal tract.

Survey items were developed based on input from a team of physicians and researchers with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of IBS. The median survey response length was 17 minutes. The survey assessed the impact of IBS on specific activities of daily living using the questions shown in table 1. These questions inquired about number of days per month of missed work/school; reduced productivity at work/school; and interference with ability to participate in personal activities. Next, the questions asked respondents to rate how much they agreed with statements about the impact of IBS on other areas of living (e.g. feeling self-conscious about body image; avoiding sex; difficulty planning activities; problems traveling; spending less time with family/friends; avoiding situations without easily accessible bathrooms) using a 4-point scale: 1= “strongly disagree”; 2= “somewhat disagree”; 3= “somewhat agree”; 4 = “strongly agree”. Finally, respondents were asked to identify “trade-offs” (i.e. what they would be willing to give up) in exchange for 1 month of hypothetical symptom relief. For these questions, they indicated “yes” or “no” regarding willingness to give up each item or activity. The list of possible trade-offs is provided in table 1. Respondents were also asked about gastrointestinal symptoms experienced in the last 12 months and how bothersome overall gastrointestinal symptoms were on a 5-point scale (1=not at all bothersome; 2=a little bothersome; 3=somewhat bothersome; 4=very bothersome; 5=extremely bothersome).

Table 1 -.

Survey questions used to assess impact of IBS on daily living

| Question | Response Options |

|---|---|

| Productivity | |

| In a typical month, how many days, if any, do these symptoms interfere with your productivity (your ability to perform at work or school)? | Open input number |

| Days Missed From Work or School | |

| About how many days, if any, in a typical month do you miss work or school because of your gastrointestinal symptoms? | Open input number |

| Participation in Personal Activities | |

| In a typical month, how many days, if any, do these symptoms interfere with your ability to participate in a personal activity (party, sporting event, family activity, etc.)? | Open input number |

| Specific Activities | |

| My symptoms prevent me from enjoying my daily activities | ** |

| My symptoms make me feel self-conscious about how I look | ** |

| My symptoms make me feel “not normal” | ** |

| I have avoided sex because of my symptoms | ** |

| I have been told that I don’t seem accused of not seeming attentive, supportive or engaged when suffering from my symptoms | ** |

| It is difficult to plan things as I never know when my symptoms will act up | ** |

| My symptoms cause me to travel less | ** |

| I spend less time with my family and friends as a result of my symptoms | ** |

| I avoid situations where there won’t be a nearby bathroom | ** |

| I don’t feel like myself | ** |

| I feel like my symptoms prevent me from reaching my full potential/being successful | ** |

| Trade-Offs | |

| What, if anything, would you give up for one month to experience one month of relief from your gastrointestinal symptoms? | |

| 1. drinking caffeinated beverages | Yes/No |

| 2. drinking alcohol | Yes/No |

| 3. the internet | Yes/No |

| 4. sex | Yes/No |

| 5. cell phone | Yes/No |

Response options: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree

Demographic data included age (years), sex, race, highest education level; marital status, median income, and employment status (employed, self-employed, temporarily unemployed, full-time student; full-time homemaker, retired). For our analyses, we considered respondents who were employed, self-employed, or full-time students to be “employed”.

Statistics

Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were expressed as proportions. Comparisons of proportions were made using Chi square test for discrete outcomes, and continuous outcomes were compared using T test for pairwise comparisons. Respondents were considered to have avoided or been impaired in a specific daily activity if they rated their agreement as “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree”.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with each of the twelve areas of reported impairment. Variables included in these models included: IBS subtype, age, employment status (employed/not employed), sex, and bothersomeness of symptoms (rated on the 5-point scale described above). All of the variables of interest were included in a single logistic model to provide mutually adjusted estimates of the odds ratio (with 95% confidence interval (CI)) for the likelihood of reporting each area of impairment. We accounted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction and an alpha level for statistical significance of 0.004.

Results

Sample

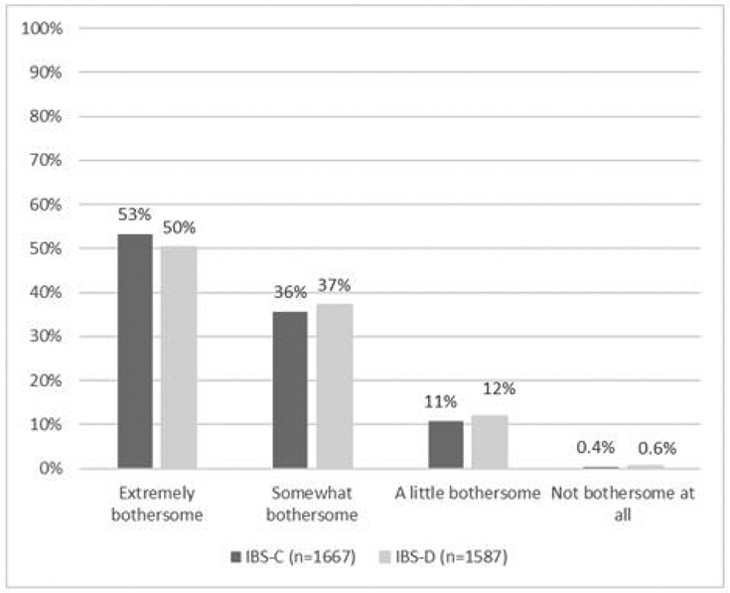

In total, 3,254 people (1,587 with IBS-D; 1667 with IBS-C) completed the questionnaires. The majority (81%) was female and Caucasian (90%). The mean age was 47.32 years (SD 15.14). Table 2 provides detailed demographics. The most commonly experienced symptom in both IBS-C and IBS-D was abdominal pain, with 84% of IBS-C and 93% of IBS-D respondents reporting having experienced the symptom in the last 12 months (table 3). Almost all (>99%) reported their gastrointestinal symptoms to be at least a little bothersome. More than half (53% IBS-C, 50% IBS-D) considered their symptoms to be at least very bothersome. There was no statistical significance in degree of bothersomeness of IBS symptoms between subtypes (Figure 1).

Table 2 -.

Demographics

| Characteristics | IBS-C n = 1667 |

IBS-D n = 1587 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 19 | 18.5 |

| Female | 81 | 81.5 |

| Age (average years, SD) | 47.92 (14.93) | 46.7 (15.34) |

| Race (%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 89 | 92 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 4 |

| Black | 5 | 2 |

| American Indian | 2 | 2 |

| Asian | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | 0 |

| Education (%) | ||

| High school or less | 17 | 14 |

| Some college | 44 | 40 |

| College | 39 | 46 |

| Marital Status (%) | ||

| Married | 65 | 65 |

| Widowed | 4 | 4 |

| Divorced | 14 | 14 |

| Single | 17 | 17 |

| Employment (%) | ||

| Employed | 46 | 50 |

| Self-employed | 8 | 6 |

| Temporarily unemployed | 5 | 6 |

| Full-time student | 3 | 2 |

| Full-time homemaker | 15 | 16 |

| Retired | 21 | 19 |

| Median Income | $68.52K | $69.62K |

Table 3 -.

Symptoms Experienced in the past year

| “Which of the following symptoms have you experienced in the past 12 months?” | |

| IBS-C (n = 1667) | |

| Abdominal pain | 83% |

| Bloating | 78% |

| Straining | 75% |

| Infrequent stools | 73% |

| Hard lumpy stools | 72% |

| Nausea | 46% |

| IBS-D (n = 1587) | |

| Abdominal pain | 93% |

| Loose watery stools | 89% |

| Cramping | 84% |

| Frequency of bowel movements | 81% |

| Urgency | 77% |

| Bloating | 69% |

| Loss of bowel control/fecal incontinence | 32% |

Figure 1.

Reported bothersomeness of gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS-C and IBS-D

Impact on daily activities

Productivity.

Of the respondents who reported being currently employed or currently in school (n=1,885), 36% reported that IBS symptoms impacted their productivity at work or school at least 10 days out of the month (average=8.0 days/month, SD=8.1). There were no statistically significant differences between IBS-C and IBS-D in terms of impact on productivity: 37% of employed respondents with IBS-C and 35% of employed respondents with IBS-D reported that symptoms impacted productivity 10 or more days per month (IBS-C: average=8.2 days (SD=8.4); IBS-D: average=7.7 days (SD=7.7). Of all employed respondents, 15.4% reported that IBS did not impact productivity at all (16.2% in IBS-C and 14.5% in IBS-D).

Days missed from work or school.

Data on number of days missed from work or school in a typical month were available from 1,497 respondents (out of 1,885 who were employed or in school). IBS-D reported missing approximately 1.3 days of work/school per month while IBS-C reported missing an average of 1.7 days per month (p=0.032). Over half of the employed respondents (56%) reported missing no days of work/school due to IBS symptoms in a typical month (IBS-C=58%, IBS-D=55%); 38% of the sample reported missing between 1 and 5 days of work/school in a typical month (IBS-C=35%; IBS-D=40%); 4% reported missing between 6 and 10 days of work/school in a typical month (IBS-C=5%; IBS-D=3%, p=NS); and about 2% reported missing more than 10 days of work/school per month (IBS-C=2%; IBS-D=2%, p=NS).

Participation in personal activities.

When asked how often their IBS symptoms interfere with personal activities (e.g. parties, sporting events, family activities, etc.), 34% of both IBS-C and IBS-D reported that symptoms interfered at least 10 days per month.

Specific activities.

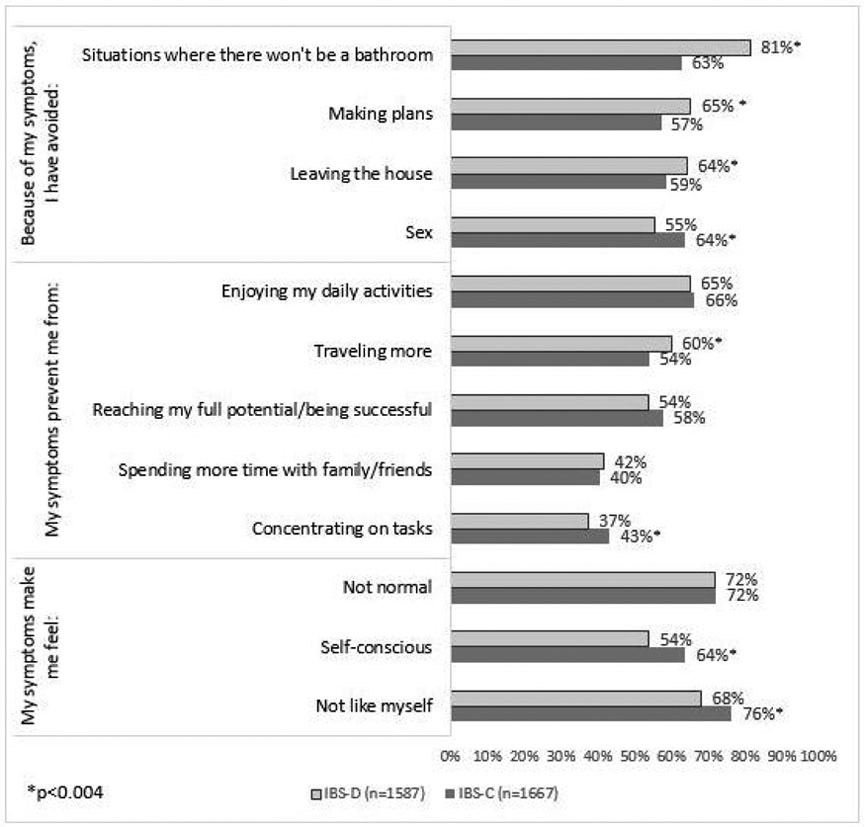

Respondents across subtypes reported a significant negative impact of IBS symptoms on overall daily functioning (Figure 2). For example, more than half the individuals reported their symptoms prevented them from enjoying daily activities, traveling more often, and feeling successful. Similarly, both subtypes reported avoiding situations where there would not be a bathroom, making social plans, leaving the house, and having sex. IBS also made the majority of individuals feel “not normal” and/or “self-conscious”.

Figure 2.

Impact of IBS symptoms on daily living: rates reporting impairment in each category as a result of symptoms in IBS-C and IBS-D

There were significant differences between subtypes of IBS in several activities of daily life (Figure 2). Respondents with IBS-C were more likely than IBS-D to report avoiding sex, feeling self-conscious about body image, have difficulty concentrating, and feeling “not like myself” as a result of their symptoms (p ≤ 0.004 for all comparisons). Respondents with IBS-D reported more avoidance of places without bathrooms, difficulty making plans, avoiding leaving the house, and traveling less than respondents with IBS-C (p ≤ 0.004 for all comparisons).

Multivariable analysis.

In separate multivariable logistic regressions predicting reported difficulty in each specific area of life and controlling for subtype (IBS-C vs. IBS-D), employment status (employed/student vs. unemployed), age, sex (male/female), and symptom bothersomeness, the subtype differences shown in figure 2 remained significant. Namely, in multivariable analyses respondents with IBS-C were significantly more likely than IBS-D to report avoiding sex, feeling self-conscious, having difficulty concentrating, and feeling “not like myself”. Respondents with IBS-C were significantly less likely than IBS-D to report avoidance of places without bathrooms, difficulty making plans, avoiding leaving the house, and traveling less as a result of their symptoms (see supplementary table 1).

In addition, being employed/student was independently associated with lower likelihood of difficulty making plans outside of the home, avoiding leaving the house, problems enjoying daily activities, and problems traveling. Older age was associated with lower likelihood of reporting difficulty leaving the house, avoiding sex, difficulty reaching one’s ‘full potential’, difficulty concentrating on tasks, feeling ‘not normal’, and feeling self-conscious. Higher symptom bothersomeness was significantly associated with difficulty with each domain. Finally, sex differences were noted in 5 of the domains, with women being more likely to report avoiding sex, feeling self-conscious about their bodies, and feeling “not like myself”. Women were less likely than men to report avoiding travel, avoiding spending time with family/friends, and difficulty concentrating due to symptoms. Univariate analyses are available in supplementary table 2.

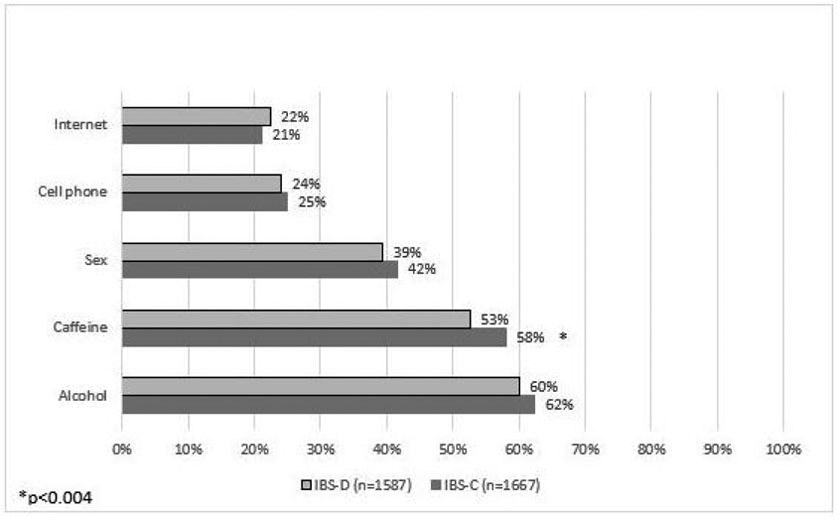

Trade-Offs.

In response to the hypothetical question “What, if anything, would you give up for one month to experience one month of relief from your gastrointestinal symptoms?” over half the sample reported that they would be willing to give up alcohol or caffeine, 40% would give up sex for one month, while 25% would give up their cell phone and 22% the internet (Figure 3). IBS-D participants were generally more willing to give up daily conveniences than IBS-C, although the only significant difference between subtypes was in the IBS-D group’s willingness to give up caffeine.

Figure 3.

“What would you be willing to give up for one month to have one month of symptom relief?”. Rates reporting willingness to give up each item in exchange for one month of symptom relief in IBS-C and IBS-D.

Discussion

The results of this survey reveal that, although IBS-C and IBS-D are equally bothersome (>50% describing IBS as “very” or “extremely” bothersome), and were associated with similar levels of absenteeism/presenteeism, they impact specific areas of daily living in different ways. IBS-D was associated with more avoidance of activities outside of the home (e.g. travel, making plans, leaving the house, going places without easily accessible bathrooms), which remained significant even when controlling for age, sex, employment status, and symptom bothersomeness. IBS-C, on the other hand, was associated with more interpersonal impairment (e.g. feeling self-conscious, avoiding sex, difficulty concentrating), which also remained significant when controlling for the above-mentioned factors.

Our finding that individuals with IBS-D are more likely to avoid specific activities outside the home, especially those without easily accessible bathrooms (e.g. traveling), can likely be explained by symptoms such as increased bowel frequency and/or urgency. On the other hand, the finding that individuals with IBS-C are more likely to internalize their distress (e.g. feel self-conscious about body image) and to avoid physical intimacy likely has both physiologic and psychological explanations. For example, higher rates of avoidance of sex in IBS-C may be related to the frequently encountered pelvic floor symptom distress such as pelvic organ prolapse and lower urinary tract symptoms, residual stool in the pelvic colon and rectum, or co-existing pelvic floor tension myalgia syndrome17. Psychologically, avoidance of sex in IBS-C may be impacted by our finding that IBS-C respondents reported feeling more self-conscious about their body image. There is compelling literature identifying the interference of IBS on sexual relationships, but this literature has not distinguished between subtypes. In one study of women with IBS, 77% reported significant sexual dysfunction compared to 29% with IBD and 14% with duodenal ulcers20. In another study of both men and women, 43% reported significant sexual dysfunction, including decreased sex-drive and dyspareunia21.

Similarly, higher rates of feeling self-conscious about body image in IBS-C compared to IBS-D may be related to symptoms of bloating and distension that are commonly reported in IBS-C. Although there is some data to suggest that individuals with IBS have lower self-esteem and poorer coping strategies compared to healthy controls20, differences between subtypes have not been evaluated.

Responses to a hypothetical question asking what respondents would be willing to give up in exchange for one month of symptom relief provides insight into the distress caused by IBS symptoms. For example, 25% of the sample reported willingness to give up their cell phone for one month and 22% reported willingness to give up the internet. 40% reported willingness to give up sex for 1 month (although this may be inflated by those who are already avoiding sex due to symptoms) and over half of the sample reported that they would give up alcohol or caffeine for one month in exchange for symptom relief. There were no statistically significant differences between IBS subtypes here, except that IBS-D was more likely to give up caffeine compared to IBS-C, which may reflect dietary restrictions that are already in place for individuals with IBS-D. These findings are in line with other published data regarding what individuals with IBS might be willing to trade for symptom relief. For example, two separate studies have reported that individuals with IBS would be willing to give up an average of 15 years of their life in exchange for permanent symptom relief21,22.

Notably, there were no differences between subtypes in number of days per month of reduced productivity at work/school, number of days per month absent from work/school, or number of days with reduced participation in personal activities. In our sample, 36% of those who were employed or enrolled in school (n=1,885) reported that IBS symptoms impacted their productivity at work or school at least 10 days out of the month (average 8.0 days/month), with an average of 1.5 days of missed work or school per month. This rate of absenteeism is somewhat higher than a previous report of individuals with IBS missing an average of 13.4 days of work/school per year8, but the overall high rates of presenteeism and absenteeism due to IBS symptoms is consistent with the literature8-10

This study highlights important differences between IBS-C and IBS-D, which could impact the development and refinement of mind-body therapies for IBS, with tailored treatment goals for each IBS subtype. For example, treatment tailored specifically for IBS-D may be more behaviorally focused (e.g. exposure to specific situations outside the home) while treatment for IBS-C may be more cognitively focused (e.g. evaluating self-esteem and beliefs about self and others) in addition to targeting the bowel dysfunction and pain.

This study has several strengths including its large sample size, inclusion of individuals from the community rather than tertiary centers, and ability to compare IBS subtypes. However, there are also several limitations. First, only IBS-C and IBS-D respondents were included and we were not able to evaluate the daily burden of IBS mixed type. Second, because this was an online survey, respondents were included based on self-report of IBS (using Rome criteria), and were not evaluated by a gastroenterologist or through evaluation of medical records. There is also the possibility of sampling and recall bias due to the online survey design. Third, this survey did not specifically assess the influence of other medical or psychiatric comorbidities on overall impairment of daily living and did not include a healthy or “non-IBS” control group for comparison. Fourth, at the time that this survey was conducted, there was no available validated measure of impairment in daily living for IBS and, as a result, the survey questions here did not use a validated measure. Finally, although this data was obtained from respondents in all 50 states, the sample is not representative of the national population in terms of demographic distribution.

In summary, results of this large survey-based study suggest that, although the perceived bothersomeness of IBS symptoms and reported rates of absenteeism/presenteeism are similar between IBS-D and IBS-C subtypes, individuals with IBS-C and IBS-D report differences in specific areas of daily functioning. Understanding these differences will be important in developing effective strategies for managing the effects of IBS symptoms on patients’ overall well-being.

Supplementary Material

What you need to know.

Background: We investigated the effects of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) on daily function and compared these among disease subtypes.

Findings: Although the perceived impact of IBS symptoms on productivity are similar in IBS-C and IBS-D subtypes, individuals with IBS-C and IBS-D report differences in specific areas of daily functioning.

Implications for patient care: This study highlights important differences between IBS-C and IBS-D, which could impact the development and refinement of mind-body therapies for IBS, with tailored treatment goals for each IBS subtype.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Monnikes H Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45 Suppl:S98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Olden K, Bjorkman D. Health-related quality of life among persons with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1171–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lea R, Whorwell PJ. Quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:643–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Agnihotri A, Pathak MK, et al. Psychiatric, somatic and other functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome at a tertiary care center. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;18:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandvik PO, Wilhelmsen I, Ihlebaek C, et al. Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: a striking feature with clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nellesen D, Yee K, Chawla A, et al. A systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Manag Care Pharm JMCP 2013;19:755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller V, Hopkins L, Whorwell PJ. Suicidal ideation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:1064–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Sci 1993;38:1569–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frändemark Å, Törnblom H, Jakobsson S, et al. Work Productivity and Activity Impairment in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Multifaceted Problem. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1540–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pare P, Gray J, Lam S, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006;28:1726–35; discussion 1710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corney RH, Stanton R. Physical symptom severity, psychological and social dysfunction in a series of outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res 1990;34:483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballou S, Keefer L. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on daily functioning: Characterizing and understanding daily consequences of IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/nmo.12982 [Accessed October 28, 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hungin APS, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, et al. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh P, Staller K, Barshop K, et al. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea have lower disease-specific quality of life than irritable bowel syndrome-constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:8103–8109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anon. GfK Knowledge Panel: A methodological overview. Available at: https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/US/documents/KnowledgePanel_-_A_Methodological_Overview.pdf [Accessed June 5, 2019].

- 17.Wong RK, Drossman DA, Weinland SR, et al. Partner burden in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2013;11:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guthrie E, Creed FH, Whorwell PJ. Severe sexual dysfunction in women with the irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and duodenal ulceration. Br Med J Clin Res Ed 1987;295:577–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fass R, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, et al. Sexual dysfunction in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Digestion 1998;59:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grodzinsky E, Walter S, Viktorsson L, et al. More negative self-esteem and inferior coping strategies among patients diagnosed with IBS compared with patients without IBS - a case–control study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:541–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.