Abstract

Background

As a main line of defense of the respiratory tract, the airway epithelium plays an important role in the pathogenesis of asthma. CDHR3 and EMSY were reported to be expressed in the human airway epithelium. Although previous genome-wide association studies found that the two genes were associated with asthma susceptibility, similar observations have not been made in the Chinese Han population.

Methods

A total of 300 asthma patients and 418 healthy controls unrelated Chinese Han individuals were enrolled. Tag-single nucleotide polymorphisms (Tag-SNPs) were genotyped and the associations between SNPs and asthma risk were analyzed by binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

After adjusting for confounding factors, the A allele of rs3847076 in CDHR3 was associated with increased susceptibility to asthma (OR = 1.407, 95% CI: 1.030–1.923). For the EMSY gene, the T alleles of both rs2508746 and rs12278256 were related with decreased susceptibility to asthma (additive model: OR = 0.718, 95% CI: 0.536–0.961; OR = 0.558, 95% CI: 0.332–0.937, respectively). In addition, the GG genotype of rs1892953 showed an association with increased asthma risk under the recessive model (OR = 1.667, 95% CI: 1.104–2.518) and the GATCTGAGT haplotype in EMSY was associated with reduced asthma risk (P = 0.037).

Conclusions

This study identified novel associations of rs3847076 in CDHR3, as well as rs1892953, rs2508746 and rs12278256 in EMSY with adult asthma susceptibility in the Chinese Han population. Our observations suggest that CDHR3 and EMSY may play important roles in the pathogenesis of asthma in Chinese individuals. Further study with larger sample size is needed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12890-020-01334-0.

Keywords: CDHR3, EMSY, Asthma, Polymorphism, Susceptibility

Background

Asthma is a chronic airway inflammatory disease that affects populations throughout the world. A World Health Organization report [1] predicted that the number of asthma patients would increase to 400 million by 2025 and 250,000 patients may die from this disease each year. A recent survey indicated that the prevalence of asthma among individuals aged > 14 years was 1.24% and there are approximately 30 million asthmatic patients in China [2]. The pathogenesis of asthma is still incompletely understood but it is known that genetic factors play a significant part in asthma susceptibility. The heritability of asthma was estimated to be 60 to 70% in an Australian twin study [3]. Genetic factors contributed to 90% of the variance in the susceptibility to asthma in a 5-year-old twin pair study [4].

As the first barrier between the human body and the environment, the airway epithelium has an important role in regulating the inflammation, immunity and tissue repair in the pathogenesis of asthma [5]. One genome-wide association study (GWAS) of a Danish population identified Cadherin related family member 3 (CDHR3), which is highly expressed in human airway epithelium, as a susceptibility locus for childhood asthma with severe exacerbations [6]. A GWAS in 2017 demonstrated that Chromosome 11 open reading frame 30 (C11orf30), also called EMSY or BRCA2-interacting transcriptional repressor, another gene expressed in airway epithelium [7], was a risk locus for food allergy in a Canadian population [8] and this gene has been shown to be involved in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression [9]. However, there have been few studies of these two genes in Chinese asthmatics. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association of common variants in CDHR3 and EMSY with adult asthma in the Chinese population.

Methods

Study population

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of both healthy controls and asthma group was the same as previously described in our published article [10]. The asthmatic cases were diagnosed by at least three respiratory physicians from the West China Hospital. From September 2013 to September 2016, 3 ml of venous blood was collected from each unrelated subject and stored in a − 80 °C refrigerator. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Protocol No. 23).

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) selection and genotyping

Tag-SNPs of CDHR3 with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.05 and r2 ≥ 0.64 were chosen as we performed before [10]. The final selected 23 tag-SNPs of CDHR3 were rs3887998, rs12155008, rs41267, rs3892893, rs10270308, rs34426483, rs193795, rs2526978, rs381188, rs10241452, rs3847076, rs11981655, rs10808147, rs193806, rs2528883, rs41269, rs2526979, rs2526976, rs41262, rs41266, rs6967330, rs41270 and rs448024 (Table S1). The selection of SNPs in EMSY was the same as gene CDHR3 except for r2 ≥ 0.80 and literature review [11–14]. The 17 SNPs of EMSY were rs3753051, rs7125744, rs7926009, rs4945087, rs2508740, rs1939469, rs7115331, rs1044265, rs12278256, rs2513513, rs2508755, rs2155219, rs2513525, rs2508746, rs1892953, rs7130588 and rs10899234 (Table S2). Genomic DNA was extracted as we performed previously [10]. As a quality control measure, 5% of randomly chosen samples, were repeated genotyped. Both genotype results reached concordance rate of 100%.

Data analyses

Software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), version 21.0, was used for statistical analyses, with p < 0.05 indicating statistically significant.

Genotype distributions under additive, dominant and recessive models were calculated by binary logistic regression analysis. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) among the controls was computed using plink software. Haploview and SHEsis software (http://analysis.bio-x.cn) were combined to perform linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype analysis. Potential function of significant SNPs was predicted by the software RegulomeDB (http://www.regulomedb.org/) and Haploreg v4 (http://compbio.mit.edu/HaploReg). Three measures, RERI (relative excess risk due to interaction), AP (the attributable proportion due to interaction) and S (synergy index), were applied to calculate biological interactions [15]. RERI and AP equal 0 and S equals 1 means no biological interaction. The interaction between these significant SNPs and smoking (smoking status = 1,non-smoking status = 0), sex (male = 1,female = 0) and body mass index (BMI, BMI ≥ 24 = 1,BMI<24 = 0) was calculated.

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 300 asthma patients and 418 healthy controls were enrolled. The average ages of asthma patients and controls were 43.6 ± 13.48 and 44.09 ± 13.75 years, respectively. No significant differences in sex, body mass index (BMI) and smoking history were observed between case and control groups (Table 1). Late-onset asthma (age of asthma onset ≥18 years) accounted for 74.3% in the case group. Most asthma individuals were outpatients (88.67%), and we could only get half of the patients’ reports of eosinophil count, total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), pulmonary function test and provocation or relaxation test. The other half of the patients’ relevant tests were done in other hospitals, but we couldn’t acquire. 58.33% of the patients adopted the step 4 treatment plan according to Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2018 update) [16], 12.67% adopted step 5, 3.33% used step 3 and the other patients’ treatment information was lost.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases and controls

| Characteristic | Control(n%) | Case (n%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 162 (38.76%) | 118 (39.33%) | 0.876 |

| Female | 256 (61.24%) | 182 (60.67%) | |

| Age (mean ± SD,years) | 44.09 ± 13.75 | 43.6 ± 13.48 | 0.64 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current and ex-smokers | 55 (13.16%) | 49 (16.33%) | 0.179 |

| Non-smoking | 207 (49.52%) | 247 (82.33%) | |

| Smoking status unclear | 156 (37.32%) | 4 (1.33%) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.94 ± 3.34 | 23.11 ± 3.28 | 0.517 |

| BMI < 24 | 227 (54.31%) | 197 (65.67%) | |

| BMI ≥ 24 | 121 (29.67%) | 103 (34.33%) | |

| Types of patients | |||

| Emergency patients or inpatients | 34 (11.33%) | ||

| Outpatients | 266 (88.67%) | ||

| Asthma onset time | |||

| Early-onset asthma(< 18 years old) | 42 (14.00%) | ||

| Late-onset asthma(≥18 years old) | 223 (74.33%) | ||

| Onset time unclear | 35 (11.67%) | ||

| Eosinophil count | 171 (57.00%) | ||

| Total IgE | 139 (46.33%) | ||

| Asthma with pulmonary function test | 174 (58.00%) | ||

| FEV1% predicted (mean ± SD) | 83.61 ± 19.97 | ||

| FEV1/FVC%(mean ± SD) | 72.37 ± 13.63 | ||

| Provocation test or relaxation test | 153 (51%) | ||

| Positive provocation test or relaxation test | 134 (44.67%) | ||

| Treatment scheme | |||

| Step 3 treatment | 10 (3.33%) | ||

| Step 4 treatment | 175 (58.33%) | ||

| Step 5 treatment | 38 (12.67%) | ||

Values are means ± standard deviation (SD) and absolute numbers (percentages). BMI body mass index; Early-onset asthma, age of asthma onset < 18 years; Late-onset asthma, age of asthma onset ≥18 years; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC forced vital capacity

Association analyses between CDHR3, EMSY SNPs and asthma susceptibility

The characteristics of the selected SNPs are listed in Table S1 and S2. Rs10899234 in EMSY and rs6967330 in CDHR3 were excluded due to their deviation from HWE in the control subjects (P < 0.05). The genotyping assays failed for rs12155008, rs41270 and rs448024 in CDHR3.

After adjusting for confounding factors including age, sex, BMI and smoking history, four SNPs were found to be associated with asthma susceptibility (Table 2 and Figure S1). The A allele of rs3847076 in CDHR3 was associated with increased susceptibility to asthma under the additive model (P = 0.032, OR = 1.407, 95% CI: 1.030–1.923). For EMSY, both the TC/TT genotype and T allele of rs2508746 were associated with decreased risk of asthma (dominant model: P = 0.019, OR = 0.660, 95% CI: 0.465–0.935; additive model: P = 0.026, OR = 0.718, 95% CI: 0.536–0.961). The TG/TT genotype and T allele of rs12278256 were associated with reduced asthma risk (dominant model: P = 0.033, OR = 0.563, 95% CI: 0.332–0.953; additive model: P = 0.027, OR = 0.558, 95% CI: 0.332–0.937). Finally, the GG genotype of rs1892953 showed an association with increased asthma risk under the recessive model (P = 0.015, OR = 1.667, 95% CI: 1.104–2.518). After excluding people who were lack of smoking or BMI information, we used the online software SNPStats (https://snpstats.net/) for statistical analysis again and the results (shown in the Table S3) were similar to Table 1. However, it should be reminded that some significant associations maybe were expected just by chance.

Table 2.

The four SNPs associated with asthma

| Genes | SNPs | Genetic models | Genotypes | Control n(%) | Case n(%) | P* | OR 95%CI* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDHR3 | rs3847076 | Dom | CC | 285 (68.2) | 185 (61.7) | 0.081 | 1.378 (0.962–1.973) |

| CA + AA | 133 (31.8) | 115 (38.3) | |||||

| Rec | CC + CA | 408 (97.6) | 285 (95.0) | 0.060 | 2.689 (0.958–7.545) | ||

| AA | 10 (2.4) | 15 (5.0) | |||||

| Add | CC/CA/AA | 0.032* | 1.407 (1.030–1.923)* | ||||

| EMSY | rs2508746 | Dom | CC | 244 (58.4) | 197 (65.7) | 0.019* | 0.660 (0.465–0.935)* |

| TC + TT | 174 (41.6) | 103 (34.3) | |||||

| Rec | CC + TC | 396 (94.7) | 288 (96.0) | 0.445 | 0.733 (0.331–1.626) | ||

| TT | 22 (5.3) | 12 (4.0) | |||||

| Add | CC/TC/TT | 0.026* | 0.718 (0.536–0.961)* | ||||

| EMSY | rs1892953 | Dom | AA | 115 (27.5) | 76 (25.3) | 0.647 | 1.094 (0.745–1.605) |

| GA + GG | 303 (72.5) | 224 (74.7) | |||||

| Rec | AA+GA | 319 (76.3) | 219 (73.0) | 0.015* | 1.667 (1.104–2.518)* | ||

| GG | 99 (23.7) | 81 (27.0) | |||||

| Add | AA/GA/GG | 0.081 | 1.240 (0.974–1.579) | ||||

| EMSY | rs12278256 | Dom | GG | 357 (85.4) | 272 (90.7) | 0.033* | 0.563 (0.332–0.953)* |

| TG + TT | 61 (14.6) | 28 (9.3) | |||||

| Rec | GG + TG | 417 (99.8) | 300 (100) | 1 | – | ||

| TT | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |||||

| Add | GG/TG/TT | 0.027* | 0.558 (0.332–0.937)* |

*Adjusted for sex, age, body mass index and smoking history with logistic regression, P < 0.05

Add additive model, Dom dominant model, Rec recessive model

Stratified analysis results by gender, smoking status, BMI status and onset age of asthma were shown in Table 3. The cut-off point of adult BMI in China is different from other countries, as 18.5 ≤ BMI < 24 kg/m2 meaning normal weight range and BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 meaning overweight or obese [17]. Allele A of rs3847076 was associated with increased susceptibility to asthma in male subgroup, smoking subgroup, BMI < 24 kg/m2 subgroup and late onset asthma subgroup (P = 0.023, OR = 1.869; P = 0.009, OR = 2.168; P = 0.005, OR = 1.835 and P = 0.023, OR = 1.457, respectively). Similarly, rs2508746 TC + TT was related with decreased asthma susceptibility in the non-smoking subgroup, non-overweight subgroup, and late-onset asthma subgroup in dominant model (P = 0.014, OR = 0.618; P = 0.027, OR = 0.612 and P = 0.016, OR = 0.637, respectively). Meanwhile, rs1892953 GG shown increased risk of asthma in the female subgroup, non-smoking subgroup, non-overweight subgroup, and late onset asthma subgroup in recessive model (P = 0.038, OR = 1.738; P = 0.04, OR = 1.615; P = 0.017, OR = 1.910 and P = 0.017, OR = 1.680, respectively). Rs12278256 T was still associated with decreased asthma susceptibility in female subgroups, non-smoking subgroups, and non-overweight subgroups in additive model (P = 0.032, OR = 0.465; P = 0.02, OR = 0.508 and P = 0.028, OR = 0.481, respectively). The interaction between these four SNPs and smoking, sex and BMI were shown in Table S4. We got significant interaction between rs3847076 and rs1892953 and smoking, sex and BMI, while no interaction was found between rs12278256 and these clinical phenotypes. Meanwhile, significant interaction could also be observed between rs2508746 and either gender or BMI.

Table 3.

Results of stratification analysis based on gender, smoking status, BMI status, and onset age of asthma

| SNPs | Genetic models | Stratified by gender | Stratified by smoking status | Stratified by BMI status | Stratified by onset age of asthma | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | OR 95%CI | P | OR 95%CI | P | OR 95%CI | P | OR 95%CI | ||||||

| rs3847076 | Dom | male | 0.048* | 1.834 (1.005–3.347) | smoking | 0.018* | 2.252 (1.149–4.413) | BMI<24 | 0.004* | 1.925 (1.233–3.007) | late onset asthma | 0.063 | 1.428 (0.981–2.077) |

| Rec | 0.115 | 5.656 (0.654–48.882) | 0.09 | 4.222 (0.799–22.320) | 0.12 | 2.835 (0.761–10.559) | 0.049* | 2.861 (1.006–8.134) | |||||

| Add | 0.023* | 1.869 (1.091–3.202) | 0.009* | 2.168 (1.212–3.872) | 0.005* | 1.835 (1.234–2.726) | 0.023* | 1.457 (1.054–2.013) | |||||

| rs2508746 | Dom | female | – | – | non-smoking | 0.014* | 0.618 (0.420–0.908) | BMI<24 | 0.027* | 0.612 (0.396–0.946) | late onset asthma | 0.016* | 0.637 (0.441–0.919) |

| Rec | – | – | 0.498 | 0.737 (0.304–1.782) | 0.862 | 0.920 (0.361–2.347) | 0.419 | 0.706 (0.304–1.641) | |||||

| Add | – | – | 0.022* | 0.685 (0.495–0.947) | 0.06 | 0.710 (0.496–1.015) | 0.021* | 0.696 (0.511–0.948) | |||||

| rs1892953 | Dom | female | 0.548 | 1.159 (0.717–1.873) | non-smoking | 0.456 | 0.174 (0.770–1.790) | BMI<24 | 0.702 | 1.097 (0.682–1.766) | late onset asthma | 0.692 | 1.084 (0.726–1.620) |

| Rec | 0.038* | 1.738 (1.031–2.927) | 0.04* | 1.615 (1.021–2.553) | 0.017* | 1.910 (1.123–3.250) | 0.017* | 1.680 (1.095–2.578) | |||||

| Add | 0.108 | 1.282 (0.947–1.737) | 0.091 | 1.259 (0.964–1.644) | 0.096 | 1.297 (0.955–1.761) | 0.094 | 1.241 (0.964–1.599) | |||||

| rs12278256 | Dom | female | 0.037* | 0.468 (0.229–0.955) | non-smoking | 0.023* | 0.512 (0.287–0.913) | BMI<24 | 0.033* | 0.485 (0.249–0.944) | late onset asthma | – | – |

| Rec | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | ||||||||

| Add | 0.032* | 0.465 (0.231–0.936) | 0.02* | 0.508 (0.288–0.897) | 0.028* | 0.481 (0.250–0.923) | – | – | |||||

*Adjusted for sex, age, body mass index and smoking history with logistic regression, P < 0.05

Add additive model, Dom dominant model, Rec recessive model

We further explored the relationship between eosinophil count, total serum IgE, pulmonary function test of asthma patients and gene variants. Eosinophil count was higher in asthma patients with genotype CC of rs3847076 comparing to individuals with genotype CA (Table S5). Total IgE was related with four variants of CDHR3 and one variant of EMSY (Table S6). Both FEV1% predicted and FEV1/FVC% were significant different in nine SNP genotypes, including rs2508746 and rs1892953. Higher FEV1/FVC% was also seen in genotype GG of rs12278256 (Table S7). Due to the small number of samples, further verification research is needed.

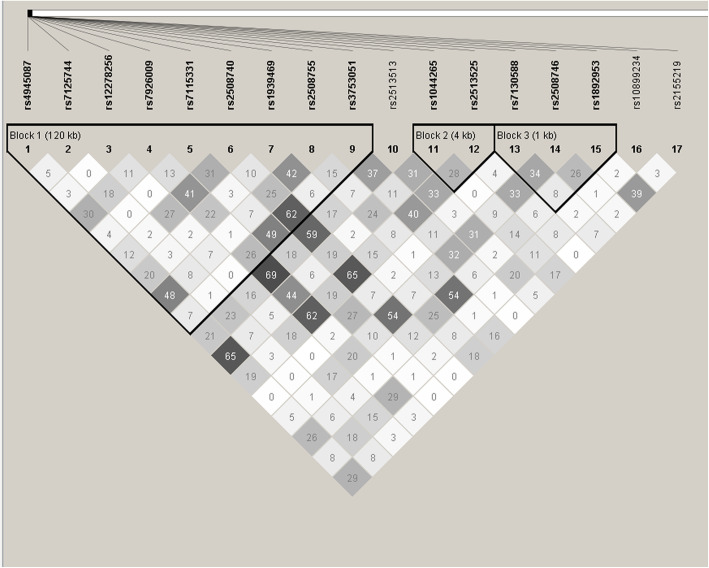

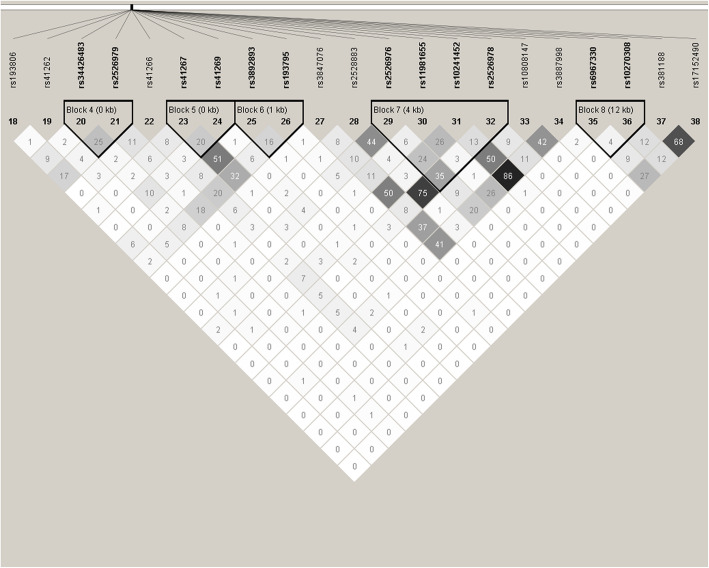

Haplotype and LD analysis

The LD between SNPs of CDHR3 and EMSY was low and those SNPs were divided into eight haplotype blocks with Haploview software (Figs. 1 and 2). Only the haplotype consisting of GATCTGAGT in block 1 of EMSY was associated with decreased risk of asthma (P = 0.037, OR = 0.615, 95% CI: 0.388–0.975) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

the Analysis of linkage disequilibrium of 17 SNPs in EMSY. Note: Each square represents the linkage disequilibrium of two corresponding SNPs, which is displayed as r2 × 100. The larger the darkness of the square, the larger the value of r2 × 100

Fig. 2.

the Analysis of linkage disequilibrium of 20 tag-SNPs in CDHR3. Note: Each square represents the linkage disequilibrium of two corresponding SNPs, which is displayed as r2 × 100. The larger the darkness of the square, the larger the value of r2 × 100

Table 4.

The association between EMSY haplotypes in block 1 and asthma susceptibility

| Haplotype | Case N (%) | Control N (%) | Chi2 | Pearson’s p | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAGTTAAAT | 207.00 (0.345) | 285.58 (0.342) | 0 | 0.999 | 1.000 (0.801–1.248) |

| GAGCGGAGC | 43.00 (0.072) | 57.59 (0.069) | 0.023 | 0.878 | 1.033 (0.685–1.556) |

| GAGCTAAAT | 44.00 (0.073) | 58.04 (0.069) | 0.054 | 0.815 | 1.050 (0.699–1.577) |

| GAGCTGAGC | 35.00 (0.058) | 52.18 (0.062) | 0.134 | 0.714 | 0.921 (0.592–1.432) |

| GAGTTAGGT | 178.00 (0.297) | 230.22 (0.275) | 0.589 | 0.443 | 1.095 (0.868–1.382) |

| GATCTGAGT | 28.00 (0.047) | 61.00 (0.073) | 4.346 | 0.037* | 0.615 (0.388–0.975)* |

| GGGCTAAAT | 60.00 (0.100) | 76.32 (0.091) | 0.246 | 0.62 | 1.094 (0.766–1.562) |

| Global result | 600 | 836 | 4.912565 | 0.555 |

For each haplotype, alleles were arranged in order of rs4945087, rs7125744, rs12278256, rs7926009, rs7115331, rs2508740, rs1939469, rs2508755 rs3753051. * means two-sided P<0.05

Functional prediction results

Four statistically significant SNPs were predicted using the software RegulomeDB and Haploreg v4 (Table S8). Rs144934374 is strongly linked to rs12278256 and its RegulomeDB scores is lower than that of rs12278256, suggesting that it may be the functional site represented by rs12278256. Acting as promoter histone marks or enhancer histone marks, or affecting DNAse is suggested to be associated with chromatin status, and binding proteins or altering regulatory motifs in ChIP-Seq suggest that transcription levels may be affected. It seems that these four SNPs may have certain effects on chromatin status and transcription level. Rs1892953 appears as an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) SNP in thyroid tissue [13].

Discussion

In this group of Chinese Han adults, the relationship between two airway epithelial-related genes EMSY and CDHR3 and risk of asthma were investigated, and four polymorphisms related to asthma susceptibility were obtained, which were rs3847076 of CDHR3 and rs2508746, rs1892953 and rs12278256 of EMSY. A further subgroup analysis of these four variants revealed that their association with asthma was present in different subgroups.

CDHR3, located on chromosome 7, is specifically expressed in ciliated airway epithelial cells which are the targets of Rhinovirus C (RV-C) infection, and its expression was positively associated with RV-C binding, replication and entry into the host cells [18, 19]. There are only a few studies describing the relationship between CDHR3 polymorphisms and asthma, and the results were inconsistent in different populations. The A allele of rs6967330 in CDHR3 increased the risk of wheezing and hospitalizations for childhood asthma in a Danish study [6]. Rs17152490, in LD with rs6967330, was reported to affect asthma risk through cis-regulation of its gene expression in human bronchial epithelial cells [20] . However, rs6967330 was only related to early-onset asthma in a Japanese population [21] and no association between rs6967330 and asthma was found in Chinese children [22]. In the present study, rs6967330 was not in HWE and our data suggest that rs3847076 may increase the risk of asthma in adults, which were inconsistent with the previous studies. The potential reasons for this discrepancy are as follows: Firstly, the susceptibility to asthma may differ in different populations, and secondly, late-onset asthma patients accounted for the majority of the case group in this study, in contrast to the above Japanese study which reported the positive relationship between rs6967330 and early-onset asthma in children. A future study of different asthma phenotypes would be beneficial to the accurate prevention and treatment of asthma.

Peripheral blood eosinophil was one of the main inflammatory cells involved in asthma and other allergic diseases [23]. Meta-analysis showed that the level of eosinophil in peripheral blood could better reflect the inflammatory status of eosinophil in airway [24], predicted the trend of long-term decline of lung function [25] and the risk of asthma attack in adults and children [26]. And more research is needed to determine whether rs3847076 genotypes of CDHR3 are related to the number of eosinophils. Some studies have shown that the serum total IgE level was related to the severity and control of asthma [27]. The relationship between CDHR3 variants and total IgE needed further investigated.

EMSY, located on chromosome 11q13.5, is expressed in the human airway epithelium and encoded by the EMSY protein. GWAS studies showed that EMSY was involved in allergic diseases including atopic dermatitis and food allergy [28, 29]. Several SNPs, rs7130588, rs10899234, rs6592657, as well as SNPs rs2508746 and rs1892953 that we studied were associated with total serum IgE levels in non-Hispanic Caucasian asthmatic patients [11]. In an eQTL analysis, Li et al. [20] reported that rs2508740, rs2513525, rs4300410 (in complete LD with rs7926009), rs10793169 (in complete LD with rs7926009), rs2513513 and rs4245443 were significantly correlated with mRNA expression levels of EMSY in human bronchial alveolar lavage. Another GWAS study reported that rs7130588 in EMSY was associated with asthma [30]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that rs2155219 in EMSY increased the risk of allergic sensitization [12]. In the present study, three SNPs (rs2508746, rs1892953 and rs12278256) were related to asthma susceptibility in the Chinese Han population, of which rs12278256 has not been reported in previous studies. As a variant located in the upstream region of EMSY, rs12278256 might affect the regulatory motifs and chromatin status of this gene and further study is needed to verify this hypothesis. Based on our results, rs2508746, rs1892953 and rs12278256 genotypes were associated with level of FEV1% predicted and/or FEV1/FVC%, which also suggested that gene EMSY was likely related with lung function.

Studies in the twin population have shown that susceptibility to asthma can be attributed to genetic factors [3, 4]. Although current genome-wide association studies have identified numerous polymorphisms associated with asthma susceptibility, the odds ratio (OR) is around 1.2, and only a small percentage of asthma prevalence can be contributed to them. Some experts have proposed to study the interaction between genes and environment [31, 32]. It is well known that environmental factors such as smoking and obesity are susceptibility factors for asthma, but the specific mechanism is not clear. A number of studies have shown that smoking is associated with increased risk of asthma, reduced efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids treatment, acute exacerbations, and airway remodeling in asthma [33–37]. Mechanisms of asthma in the obese may include mechanical factors and inflammatory immunity [38]. Studies have shown that the SNPs at 17q21.2 is associated with BMI levels in asthmatic patients [39]. Functional prediction suggests that the alternate A allele of rs3847076 decrease the effect on motif TCF4 relative to the reference C allele, according to the library [40].

Recently, genetic studies have detected a lot of susceptibility genes for asthma. This study was the first attempt to investigate the association between CDHR3, EMSY and adult asthma susceptibility in the Chinese Han population. We found rs3847076 in CDHR3, rs2508746, rs1892953 and rs12278256 in EMSY were associated with the risk of adult asthma. However, there were some limitations to this study. Adjustment was not performed to correct the results for multiple testing, due to the weak effect of each single polymorphism on asthma susceptibility. In addition, the allergic phenotypes of the asthma patients were not clear and serum IgE levels were not analyzed in the study. Lastly, CDHR3 is a huge gene spanning over 159 kb and the strategy of tag-SNPs selection with r2 > 0.64 in this study may have missed some SNPs associated with the disease.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study is the first to identify that the airway epithelium related genes EMSY and CDHR3 were associated with adult asthma susceptibility in the Chinese Han population. The CDHR3 rs3847076 allele A and EMSY rs1892953 genotype GG may increase the risk of asthma. The EMSY rs2508746 and rs12278256 allele T may decrease asthma risk. A population with a larger sample size is needed for further exploration of the association.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Characteristics of Tag-SNPs in CDHR3. Table S2. Characteristics of the SNPs in EMSY. Table S3. The four SNPs associated with asthma susceptibility in remaining 549 individuals after excluding subjects with missing information on smoking or BMI. Table S4. Interaction between four SNPs and smoking, gender and BMI. Table S5. The two SNPs associated with the number of Eosinophil cell. Table S6. The five SNPs associated with total IgE. Table S7. The 13 SNPs associated with FEV1% predicted and 14 SNPs associated with FEV1/FVC%. Table S8. Functional prediction results by softwares RegulomeDB and HaploReg v4. Figure S1. The volcano plots of significant SNPs.

Acknowledgements

We thank everyone who provided blood samples and consent for genetic analysis. And we thank all of the clinicians, nurses and study coordinators for their contributions to the work.

Abbreviations

- Tag-SNPs

Tag-single nucleotide polymorphisms

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Study

- CDHR3

Cadherin related family member 3

- C11orf30

Chromosome 11 open reading frame 30

- SNPs

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

- MAF

Minor Allele Frequency

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- LD

Linkage Disequilibrium

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- RV-C

Rhinovirus C

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- eQTL

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci

- OR

Odds Ratio

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, JQH; Data and Formal analysis, YW and SQW; Project administration, MMZ, Guo Chen and JQH; Supervision, JQH; Writing – original draft, MMZ and GC; Writing – review & editing, AJS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The design of the study, sample collection, Genomic DNA extraction, SNP selection and genotyping were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 81370121] and the Health and Family Planning Commission of Sichuan Province Project [Grant No. 16PJ413]. The analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript writing were supported by the Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences & Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital Project [Grant No. 2017QN11] and the Sichuan Provincial Cadre Health Research Project [Grant No. 2018–211].

Availability of data and materials

All data of the study are available in the excel named “Additional file 2”.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols for this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Protocol No. 23). Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Miao-miao Zhang and Guo Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Miaomiao Zhang, Email: zhangmiaomiao0522@126.com.

Guo Chen, Email: 5503850@163.com.

Yu Wang, Email: 390628840@qq.com.

Shou-Quan Wu, Email: 76201313@qq.com.

Andrew J. Sandford, Email: Andrew.Sandford@hli.ubc.ca

Jian-Qing He, Email: jianqing_he@scu.edu.cn, Email: jianqhe@gmail.com.

References

- 1.WHO. Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. 2007. WHO website: http://wwww.hoint/respiratory/publications/global_surveillance/en/. Accessed 23 Apr 2018.

- 2.Lin J, Wang W, Chen P, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of asthma in mainland China: the CARE study. Respir Med. 2018;137:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffy DL, Martin NG, Battistutta D, et al. Genetics of asthma and hay fever in Australian twins. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142(6 Pt 1):1351–1358. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Beijsterveldt CE, Boomsma DI. Genetics of parentally reported asthma, eczema and rhinitis in 5-yr-old twins. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(3):516–521. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The airway epithelium in asthma. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):684–692. doi: 10.1038/nm.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnelykke K, Sleiman P, Nielsen K, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies CDHR3 as a susceptibility locus for early childhood asthma with severe exacerbations. Nat Genet. 2014;46(1):51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Oksvold P, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(2):397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asai Y, Eslami A, van Ginkel CD, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis in multiple populations identifies new loci for peanut allergy and establishes C11orf30/EMSY as a genetic risk factor for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(3):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varier RA, Carrillo de Santa Pau E, van der Groep P, et al. Recruitment of the mammalian histone-modifying EMSY complex to target genes is regulated by ZNF131. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(14):7313–7324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.701227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G, Luo L, Zhang M, et al. Association study of myosin heavy chain 15 polymorphisms with asthma susceptibility in Chinese Han. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:3805405. doi: 10.1155/2019/3805405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Ampleford EJ, Howard TD, et al. The C11orf30-LRRC32 region is associated with total serum IgE levels in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):575–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnelykke K, Matheson MC, Pers TH, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies ten loci influencing allergic sensitization. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):902–906. doi: 10.1038/ng.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consortium GT Human genomics. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348(6235):648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weidinger S, Willis-Owen SA, Kamatani Y, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(23):4841–4856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson T, Alfredsson L, Kallberg H, Zdravkovic S, Ahlbom A. Calculating measures of biological interaction. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(7):575-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Global Initiative for asthma . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Disease Control, people's Republic of China . Guidelines for Prevention and Control of overweight and Obesity in Chinese Adults. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bochkov YA, Watters K, Ashraf S, et al. Cadherin-related family member 3, a childhood asthma susceptibility gene product, mediates rhinovirus C binding and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(17):5485–5490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421178112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griggs TF, Bochkov YA, Basnet S, et al. Rhinovirus C targets ciliated airway epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0567-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Hastie AT, Hawkins GA, et al. eQTL of bronchial epithelial cells and bronchial alveolar lavage deciphers GWAS-identified asthma genes. Allergy. 2015;70(10):1309–1318. doi: 10.1111/all.12683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanazawa J, Masuko H, Yatagai Y, et al. Genetic association of the functional CDHR3 genotype with early-onset adult asthma in Japanese populations. Allergol Int. 2017;66(4):563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Zhang J, Hu H, et al. Polymorphisms of RAD50, IL33 and IL1RL1 are associated with atopic asthma in Chinese population. Tissue Antigens. 2015;86(6):443–447. doi: 10.1111/tan.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matucci A, Vultaggio A, Maggi E, et al. Is IgE or eosinophils the key player in allergic asthma pathogenesis? Are we asking the right question? Respir Res. 2018;19(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0813-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korevaar DA, Westerhof GA, Wang J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of minimally invasive markers for detection of airway eosinophilia in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(4):290–300. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hancox RJ, Pavord ID, Sears MR. Associations between blood eosinophils and decline in lung function among adults with and without asthma. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(4):1702536. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02536-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price DB, Rigazio A, Campbell JD, et al. Blood eosinophil count and prospective annual asthma disease burden: a UK cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(11):849–858. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka A, Jinno M, Hirai K, et al. Longitudinal increase in total IgE levels in patients with adult asthma: an association with poor asthma control. Respir Res. 2014;15:144. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marenholz I, Grosche S, Kalb B, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies the SERPINB gene cluster as a susceptibility locus for food allergy. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esparza-Gordillo J, Weidinger S, Folster-Holst R, et al. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffatt MF, Gut IG, Demenais F, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ober C. Asthma genetics in the Post-GWAS Era. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(Suppl 1):S85–S90. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-459MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura K, Nagata C, Fujii K, et al. Cigarette smoking and the adult onset of bronchial asthma in Japanese men and women. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):288–293. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60333-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimoda T, Obase Y, Kishikawa R, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on airway inflammation and inhaled corticosteroid treatment in patients with asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37(4):50–58. doi: 10.2500/aap.2016.37.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heijink I, van Oosterhout A, Kliphuis N, et al. Oxidant-induced corticosteroid unresponsiveness in human bronchial epithelial cells. Thorax. 2014;69(1):5–13. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverman RA, Boudreaux ED, Woodruff PG, et al. Cigarette smoking among asthmatic adults presenting to 64 emergency departments. Chest. 2003;123(5):1472–1479. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fattahi F, Hylkema MN, Melgert BN, et al. Smoking and nonsmoking asthma: differences in clinical outcome and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(1):93–105. doi: 10.1586/ers.10.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon AE, Holguin F, Sood A, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: obesity and asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(5):325–335. doi: 10.1513/pats.200903-013ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Murk W, DeWan AT. Genome-Wide Gene by Environment Interaction Analysis Identifies Common SNPs at 17q21.2 that Are Associated with Increased Body Mass Index Only among Asthmatics. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kheradpour P, Kellis M. Systematic discovery and characterization of regulatory motifs in ENCODE TF binding experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(5):2976–2987. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Characteristics of Tag-SNPs in CDHR3. Table S2. Characteristics of the SNPs in EMSY. Table S3. The four SNPs associated with asthma susceptibility in remaining 549 individuals after excluding subjects with missing information on smoking or BMI. Table S4. Interaction between four SNPs and smoking, gender and BMI. Table S5. The two SNPs associated with the number of Eosinophil cell. Table S6. The five SNPs associated with total IgE. Table S7. The 13 SNPs associated with FEV1% predicted and 14 SNPs associated with FEV1/FVC%. Table S8. Functional prediction results by softwares RegulomeDB and HaploReg v4. Figure S1. The volcano plots of significant SNPs.

Data Availability Statement

All data of the study are available in the excel named “Additional file 2”.