Abstract

Although lockdown measures to stop COVID-19 have direct effects on disease transmission, their impact on violent and accidental deaths remains unknown. Our study aims to assess the early impact of COVID-19 lockdown on violent and accidental deaths in Peru.

Based on data from the Peruvian National Death Information System, an interrupted time series analysis was performed to assess the immediate impact and change in the trend of COVID-19 lockdown on external causes of death including homicide, suicide, and traffic accidents. The analysis was stratified by sex and the time unit was every 15 days.

All forms of deaths examined presented a sudden drop after the lockdown. The biggest drop was in deaths related to traffic accidents, with a reduction of 12.22 deaths per million men per month (95% CI: −14.45, −9.98) and 3.55 deaths per million women per month (95% CI:-4.81, −2.30). Homicide and suicide presented similar level drop in women, while the homicide reduction was 2.5 the size of the suicide reduction in men. The slope in homicide in men during the lock-down period increased by 6.66 deaths per million men per year (95% CI:3.18, 10.15).

External deaths presented a sudden drop after the lockdown was implemented and an increase in homicide in men was observed. Falls in mobility have a natural impact on traffic accidents, however, the patterns for suicide and homicide are less intuitive and reveal important characteristics of these events, although we expect all of these changes to be transient.

Keywords: COVID-19, Suicides, Public policy, Lockdown, External deaths

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has had a serious impact on population health worldwide (Sohrabi et al., 2020), not only as a direct consequence of the infection but also due to the measures taken to reduce its transmission. These unprecedented changes in the lifestyles of millions have also impacted mental health, society and economy in various ways (Balhara et al., 2020; Ayittey et al., 2020).

The main strategies to reduce COVID-19 transmission are social distancing and isolation measures. Policies range from advising individuals to keep 2 m apart in public spaces all the way to generalized lockdowns (Wilder-Smith and Freedman, 2020), all to reduce the pace of transmission and to prevent health services from being overwhelmed (Matrajt and Leung, 2020).

By the middle of June 2020, Latin-America had become a focus of COVID-19 infection. To slow the spread, most of the region have taken severe lockdown measures (Dyer, 2020). Peru was one of the countries with the earliest and strictest national lockdown in Latin-America and has won international recognition for its pandemic response, starting restrictions right after the first confirmed case in mid-March 2020 and lasting for over 100 days until the end of June in most of the country (Dyer, 2020; Decreto Supremo N° 044–2020-PCM, 2020; Decreto Supremo N° 116–2020-PCM, 2020; Alvarez-Risco et al., 2020).

Although measures such as national lockdowns are expected to have a direct impact on transmission and subsequent mortality due to COVID-19 (Gerli et al., 2020; Alfano and Ercolano, 2020; Lau et al., 2020), the interruption of all daily activities suggests that they may also impact other aspects of health and causes of death (Thakur et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). Radical changes in the daily activities of individuals, self-isolation, financial uncertainty, job losses, and reduced incomes have the potential to influence mortality due to violent crimes, suicides, domestic violence, and other external causes of death (Thakur and Jain, 2020; Marques et al., 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Ashby, 2020).

Early reports have indicated a substantial drop in violent crime rates across the world, with a drop in crime close to 50% in some cities following some of the most restrictive measures (Stickle and Felson, 2020; Shayegh and Malpede, 2020). Reports of domestic violence have increased since social distancing measures came into effect, as victims are forced to be isolated with their abusers (Vieira et al., 2020; Sacco et al., 2020). The UN has estimated that domestic violence increased by over 30% in some countries since lockdown with a surge in the need for shelters (Women, 2020; Boserup et al., 2020).

Lockdowns have also been accompanied by travel bans and a reduction in mobility, leading to a decrease in the use of motor vehicles (Kerimray et al., 2020) with a consequential drop in traffic accidents and resultant emergency visits and deaths (Morris et al., 2020; Nuñez et al., 2020). The mental health effects of COVID-19 and of the accompanying economic crisis have also been profound, with suicide as a concern (Thakur and Jain, 2020). Previous pandemic scenarios have also shown a change in suicide trends including the 1918 influenza pandemic and 2003 SARS epidemic (Cheung et al., 2008; Wasserman, 1992).

Developing countries appear to be more susceptible to the effects of confinement on mental health, due to economic constraints, unavailability of food and overall socio-economic insecurity, which could aggravate psychological conditions (Islam et al., 2020). Increased suicides related to economic hardship as well as a result of the lockdown have been reported in Bangladesh (Bhuiyan et al., 2020; Mamun et al., 2020a; Mamun et al., 2020b), Pakistan (Mamun and Ullah, 2020) and India (Dsouza et al., 2020). Furthermore, there have been reports on special cases of suicides during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as couples making suicide pacts (Griffiths and Mamun, 2020), mother and son suicide pacts due to COVID-19-related online learning issues (Mamun et al., 2020a), suicide due to non-treatment by healthcare staff (Mamun et al., 2020b), and infanticide-suicide (Mamun et al., 2020c). A common denominator in these cases is the financial instability and uncertainty experienced during the pandemic, which makes an in-depth analysis of the issue necessary to take measures that can prevent this loss of life.

Although by the end June 2020 most countries have relaxed their lockdown measures, their diverse consequences are still unclear and are just now beginning to be studied empirically. Our study aims to assess the early impact of the COVID-19 national lockdown on homicide, suicide, and traffic accident deaths in the Peruvian setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

We used data from the Peruvian National Death Information System (SINADEF) (Información de Fallecidos del Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones SINADEF, 2020) which collects daily death certificates nationwide with available data since 2017. SINADEF has improved the quality of data registration in the recent years, managing to improve its coverage including close to 80% of all deaths in the national territory (Vargas-Herrera et al., 2018). Even though coverage has improved, the updating of the database has a certain degree of delay. To assess this delay, the database published on SINADEF's web page (Información de Fallecidos del Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones – SINADEF, 2020) has been downloaded on a daily basis for one month. It was found that after 15 days, the database did not show an increase in data greater than 1% from the first day. For the present study, data on deceased adults (18 years old or older) is included from January 1st, 2017 until September 26th, 2020, using the database published on October 25 to minimize any lost of information.

On March 16, 2020, the Peruvian government decreed a state of sanitary emergency, suspending economic, academic, and recreational activities across the entire country of 32 million people. Only essential activities including food supply, pharmacies, and banking remained accessible. Moreover, international borders were closed, military and police patrolled the streets, and a curfew was instituted from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. Public transport capacity was also reduced by half and movement between regions within the country was banned. Although some of the components of the lockdown have changed throughout its implementation, the core aspects of the lockdown remained constant until the end of June 2020, after this point, the lockdown measures were relaxed maintaining the state of national emergency and with focalized lockdowns in some regions (Decreto Supremo N° 044–2020-PCM, 2020; Decreto Supremo N° 116–2020-PCM, 2020).

2.2. Measures

Because the lockdown was implemented in the middle of March and there is a relatively low count of daily deaths, we chose to aggregate the data in bins of 15 days each to have a uniform time unit throughout our study period.

Information on the cause of death, sex, and age were taken directly from the SINADEF report. The death certificate in the SINADEF system makes the distinction between non-external death, as death from an underlying disease or complication, and external death, as one that occurs as direct or indirect consequence of an injury (accidental, non-accidental or of undetermined intention) or of an injury that is the consequence of violence (homicide, suicide, accident or suspicion of having been caused intentionally) (MINSA, 2018). The specification of each type of external death is reported in an independent item for homicide, suicide, traffic accidents, work accidents and other types of accidental death. This item was used to identify the type of death, obviating the need to use the ICD 10 coding, which is underreported on the death certificates (Vargas-Herrera et al., 2018). The number of events was transformed into the rate per 1,000,000 population for better comparison based on the population report from the latest National Census (PERÚ – INEI, 2017).

Because the COVID-19 pandemic imposes additional stress on health workers and the health system, the reporting, and coding of deaths could be affected by this overload of work (Zylke and Bauchner, 2020; Leon et al., 2020). To estimate if external deaths recording was affected by this scenario, we estimated the proportion of external deaths labeled as “unspecified” as a proportion of the total external deaths. This fraction was assessed in the same way as the main outcomes to find any change in the trends after lockdown. We also examined trends in non-external deaths to ensure that registration was consistent before and during the lockdown.

To have a measure of the degree of compliance with lockdown and an approximation to the use of motor vehicles we used descriptive data from the mobile-phone mobility data provided by Google Community Mobility Reports for public transit places (Google LLC, 2020). This report presents the percent change in visits to transport places for each day compared to a baseline value.

2.3. Statistical analysis

To assess the immediate impact and change in the trend of COVID-19 lockdown, we analyzed the external death rates per population using an interrupted time series analysis (Turner et al., 2020). A linear regression model was fitted to the external deaths rates with a time variable (every 15 days), a variable to indicate post-lockdown, which was defined since March 16, 2020, and an interaction term between the post-lockdown indicator and the time variable, to evaluate a change in the slope of the outcome trend after lockdown. Stratified analysis was performed for women and men because of known differences in external deaths by sex. Autocorrelation of the time series was assessed through a correlogram and seasonality through visual inspection of the plots. The analysis was conducted using R 3.6.1.

3. Results

A total of 472,153 events were identified as adult deaths from January 1st, 2017 to September 26th, 2020. External deaths sum up to 15,591 including 7113 traffic accidents, 3117 homicides, 1752 suicides, and 3609 other forms of accidental deaths. No autocorrelation or seasonality was found in any time series because the entire follow-up period spanned only 5.5 months.

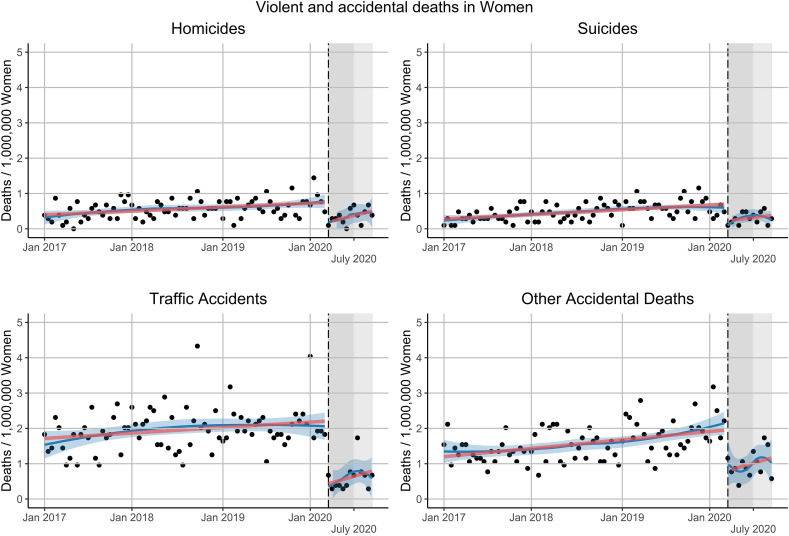

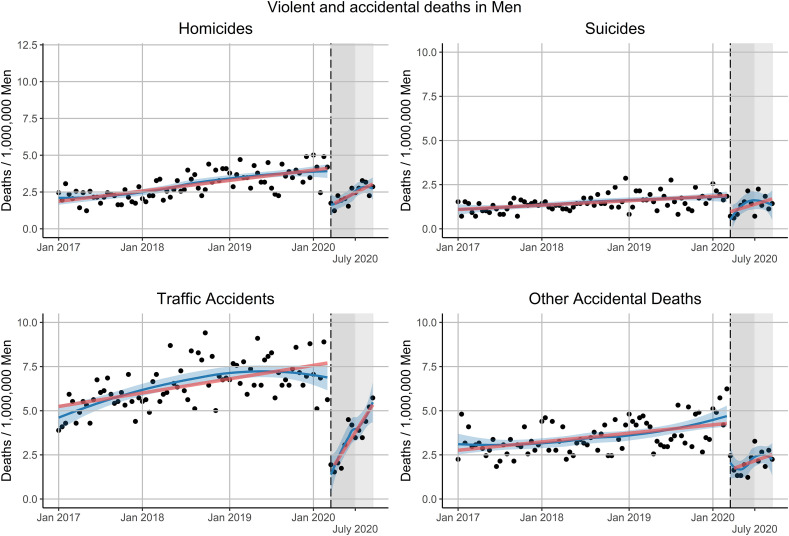

The time slope in the pre-lockdown period was positive for all types of external deaths in both sex groups with the highest for male traffic accidents, with an extra 0.77 deaths per year per million men (95% CI: 0.53, 1.00) and the lowest in female homicides, with an extra 0.11 deaths per year per million women (95%CI: 0.05, 0.17). All forms of external deaths presented a sudden drop after the implementation of the lockdown in both groups. The biggest difference in the post-lockdown period was in deaths related to traffic accidents, with a reduction of 12.22 deaths per million men per month (95% CI: −14.45, −9.98) and a reduction of 3.55 deaths per million women per month (95% CI:-4.81, −2.30) after the lockdown. Homicide and suicide presented a similar level drop in women with around 1 fewer death per million women per month, while the homicide reduction was 2.5 times the suicide reduction in men with 5 and 2 fewer deaths per million men per month respectively. Other forms of accidental deaths in women presented a reduction of 2 deaths per million women per month, being the second-highest drop in this group (Table 1 ). We detected an increase in the slope of traffic accidents in men in the post-lockdown period with an extra 6.66 deaths per million men per year (95% CI: 3.18, 10.15), an increase in the slope in suicides with an extra 1.20 deaths per million men per year (95% CI: −0.26, 2.65) and an increase in the slope in homicides with 2.19 deaths per million men per year (95% CI: 0.01, 4.37). No other major change in the post-lockdown slope compared to the pre-lockdown period was found in the other types of external death in women (Fig. 1 ) or men (Fig. 2 ). The post-lockdown follow-up is short and so there is limited statistical power to detect a slope change among these points (Hawley et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Interrupted time series coefficients by sex and type of external death.

| Type of death x 1,000,000 | 1 year Slope (95% CI) |

Post-lockdown Difference per month (95% CI) |

Post-lockdown x 1 year Interaction (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||

| Homicide | 0.11 (0.05, 0.17) | −1.10 (−1.65, −0.55) | 0.50 (−0.36, 1.36) |

| Suicide | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) | −0.94 (−1.41, −0.46) | 0.18 (−0.56, 0.91) |

| Traffic accident | 0.15 (0.02, 0.28) | −3.55 (−4.81, −2.30) | 0.57 (−1.39, 2.53) |

| Other accident | 0.23 (0.13, 0.34) | −2.31 (−3.30, −1.33) | 0.49 (−1.05, 2.03) |

| Men | |||

| Homicide | 0.70 (0.55, 0.84) | −5.05 (−6.45, −3.65) | 2.19 (0.01, 4.37) |

| Suicide | 0.24 (0.15, 0.34) | −1.84 (−2.74, −0.91) | 1.20 (−0.26, 2.65) |

| Traffic accident | 0.77 (0.53, 1.00) | −12.22 (−14.45, −9.98) | 6.66 (3.18, 10.15) |

| Other accident | 0.47 (0.29, 0.66) | −5.26 (−7.04, −3.48) | 1.23 (−1.55, 4.00) |

Fig. 1.

Interrupted time-series analysis external deaths by type of death in Women. The vertical black dashed line corresponds to the beginning of the lockdown (March 16, 2020) and the grey shading to the lockdown period and ligther grey to the relaxation of lockdown measures. The solid red lines correspond to the interrupted time-series linear regression model, the solid blue line corresponds to the LOESS smoother with 0.6 span and the blue shading corresponds to a 0.95 confidence interval around the LOESS smoother line. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Interrupted time-series analysis external deaths by type of death in Men. The vertical black dashed line corresponds to the beginning of the lockdown (March 16, 2020) and the grey shading to the lockdown period and ligther grey to the relaxation of lockdown measures. The solid red lines correspond to the interrupted time-series linear regression model, the solid blue line corresponds to the LOESS smoother with 0.6 span and the blue shading corresponds to a 0.95 confidence interval around the LOESS smoother line. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

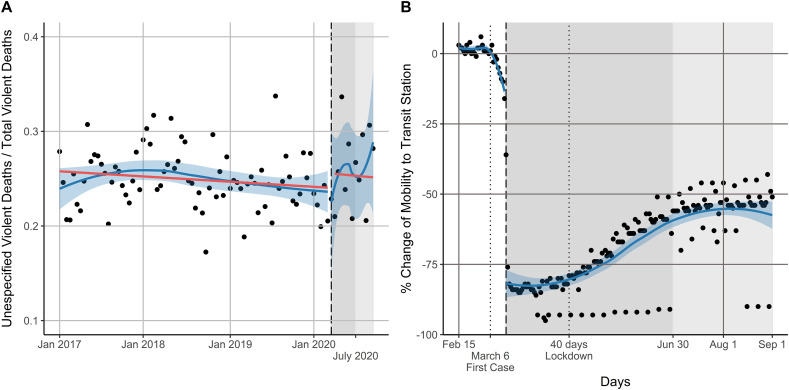

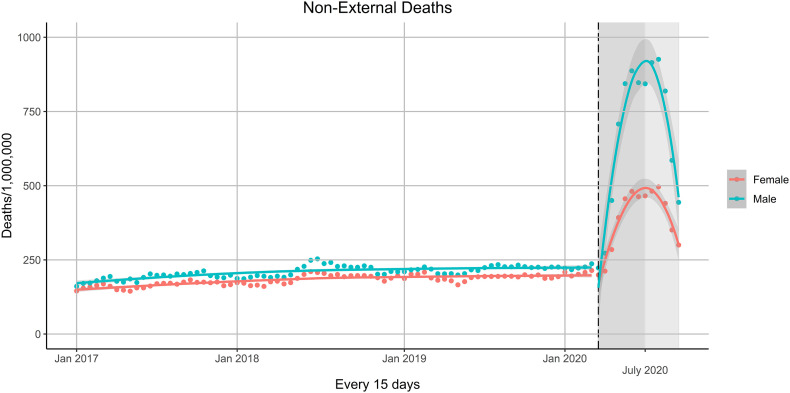

There was no change in the level or the trend of the unspecified external death proportion (Fig. 3A) and the registration of non-external deaths was also consistent in the post-lockdown period (Appendix Fig. 1). The mobility data (Fig. 3B) shows an early drop in mobility to transit stations right after the first confirmed case with a gradual reduction until the start of the lockdown. After lockdown, the mobility fell below −75% after the second day and held constant at around −80% for 40 days. After that period, mobility gradually recovered, with an increasing tendency through the end of the lockdown. The episodic drops shown close to −100% represent the strict curfew on Sundays and holidays.

Fig. 3.

Panel A: Interrupted time-series analysis the propotion of external deaths labeled as “unescpecified”. The solid red lines correspond to the interrupted time-series regression model. Panel B: Descriptive view of the percentage change in community mobility to transit stations before and after the lockdown period. The first vertical black dotted line corresponds to the firs case confirmation and the second the 40 day lockdown mark. Panel A and B: The vertical black dashed line corresponds to the beginning of the lockdown (March 16, 2020) and the grey shading to the lockdown period and ligther grey to the relaxation of lockdown measures, the solid blue line corresponds to the LOESS smoother with 0.6 span and the blue shading corresponds to a 0.95 confidence interval around the LOESS smoother line. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

In this nationwide time series analysis, we found that lockdown implementation was associated with a sudden reduction in all major forms of external deaths (homicides, suicides and traffic accidents represented 79% of total external deaths in 2019 (Peru: REUNIS, 2020)) with a detected change in the post-lockdown trend of suicides in men. Nonetheless, we do expect rates to return to their pre-pandemic levels at some future point. The biggest immediate absolute reduction was seen in traffic accidents and the smallest in suicides, but of course this also reflects the higher absolute burden of traffic accidents as a cause of death.

These results are consistent with both the theoretical rationale behind lockdown and various early reports in other parts of the world. The change in lifestyle and behaviors associated with limited outside activities and economic shutdown must certainly play a role in the mechanism behind the acute change in the rates of these types of deaths. Falls in mobility have a natural impact on road traffic accidents, since people staying at home are at no risk for these events. The decreases in suicide and homicide are less obvious. Suicide might be expected to increase from economic and social stress and the disruption of daily routine (Gunnell et al., 2020a; Sher, 2020a).

Expectations about homicide are also not so clear. As lockdown measures began, conventional crimes began to slow down around the world. Studies that evaluated the short-term effects of lockdown on different types of crime reports in Los Angeles and Indianapolis in the USA found a marked decrease in the robbery, burglary, and aggravated assault after the stay-at-home measures took place (Mohler et al., 2020; Campedelli et al., 2020).

Most homicides in men in Latin-America and around the world are associated with crime (Ribeiro et al., 2015; Drugs UNO on, Crime, 2019), and since lockdown, both murder and crime decreased in the region (Crimen cae en calles de Latinoamérica en tiempos de COVID-19, 2020). In Mexico, murder rates, which started at a historic high in 2020, dropped dramatically almost halfway from the national average of 81 per day to 54 after social distancing measures were put in place (Crime, 2020) and a similar pattern has been seen in other countries in the region. In our time series analysis, we also found a marked dropped in homicides after lockdown. Although this aligns with most reports in the region, this decrease in homicides contrasts with what is happening in some cities in the USA where crime is down, but murder is up, without a clear explanation of this divergence (Asher and Horwitz, 2020). Now in the post-lockdown period of our time series there is already the first hint of a increase in the rates of homicides.

Most homicides in men are associated with crime, however, most homicides in women are hate crimes, which are classified in Peruvian law as “feminicides”. In Peru, the first cause of homicide in women is intimate partner violence, with 1 of every 5 women having the partner as the perpetrator (Motta, 2019). Isolation measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 have created greater risks for women living in situations of domestic violence as the victims are isolated with their agressors (Sacco et al., 2020; Women, 2020; Neil, 2020). Although we found a reduction in women's homicides overall, this does not exclude the increase in other forms of violence. A recent study from Peru showed a 48% increase in calls to helpline for domestic violence since the pandemic, with effects increasing over time. Similarly, a study conducted in the USA found that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a 7.5% increase in domestic violence service calls during the 12 weeks after social distancing began (Leslie and Wilson, 2020).

The reduction in women's homicides found in this study might reflect the conditions in which partner-perpetrated violence occurs. According to a study carried out in autopsies of women victims of violence, the most frequent place where the body was found was in public places, rivers, or open fields (43.4%), compared to the home (22.9%) (Casana-Jara, 2020). Lockdown restrictions may have imposed an additional barrier in the occurrence of these tragic acts as police and military were constantly watching the streets.

Mental health during lockdown has also been a constant concern (Thakur et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020; Thakur and Jain, 2020; Torales et al., 2020; Monjur, 2020). Some initial reports show the increase in suicides rate during this pandemic as a consequence of lockdown, financial stress, uncertainty, and isolation (Monjur, 2020; Shoib et al., 2020). This financial uncertainty has also been reported in developed countries. In Canada two possible projection scenarios based on an increase in unemployment following the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a projected total of 11.6 to 13.6 excess suicides in 2020–2021 per 100000 (McIntyre and Lee, 2020).

The main factors contributing to suicidal behaviour during the pandemic have been characterized in terms of anxiety, stress, social isolation, fear of getting infected, uncertainty, and economic difficulties (Sher, 2020b; Gunnell et al., 2020b). These factors may lead to the exacerbation of phycological distress in vulnerable populations including those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, persons with low resilience, individuals who live in high disease areas and people who have someone close who has died of or is infected with COVID-19 (Sher, 2020b; Gunnell et al., 2020b; Beaglehole et al., 2018; Sher, 2019). Furthermore, those with pre-existing conditions include not only patients who were under retreatment before the pandemic, who might have difficulties finding treatment during the pandemic, but also a very large number of people with psychiatric conditions who did not receive treatment even before the pandemic (Kohn et al., 2004). People in suicidal crises require special attention, and the assistance services might be interrupted during the pandemic. Some might not seek traditional help due to fear of infection and others may seek help from helplines where the demand has exceeded the supply of services due to surges in calls and reductions in personnel (Gunnell et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020).

Our results show that after lockdown the immediate rate of suicides declined, however, men presented an increase in the slope of suicides in the post-lockdown period. One of the factors may be the loss of employment and financial stressors which are well-recognised risk factors for suicide (Stuckler et al., 2009). Nearly 81% of men in Peru have a paid job compare to 64% women (Gutiérrez Espino and others, n.d.), and during the pandemic, the male working population in the country capital decreased by 47.3% and the female working population by 48.1% (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica, 2020).

These initial changes in suicide trends may give us an idea of what might come next as a result of these social changes. Furthermore, the lockdown might also affect the younger population differently. An exploratory study based on media reports found that reported suicides among adolescents and youths during the lockdown were related to loneliness, overwhelming academic distress and social media related psychological distress (Manzar et al., 2020).

Traffic accidents were the type of external death that decreased the most and this observation is consistent with many of the specific restrictions adopted, including the general limit of transit as well as the imposition of strict curfews at night and on Sundays. Other countries have also seen a decline in emergency room visits for trauma injuries related to traffic accidents after the lockdown (Nuñez et al., 2020; Sakelliadis et al., 2020).

An increasing rate towards the end of the lockdown is more apparent for traffic accidents than for other types of death. This mirrors quite closely the changes observed in mobility trends. Both, traffic accident deaths and the mobility change present as U-shaped trends during lockdown, demonstrating that the lockdown measures were not fully adopted at the beginning and that they eased gradually towards the end. Other forms of external death have also shown a decline and even appear to be in decline after the lockdown, however, as economic activities resume, this rate may recover the baseline level as with the other types of death.

This report constitutes an initial analysis of the trends in external deaths and as such, we recognize some limitations. Although we found that there was no major change in the occurrence of deaths coded as “unknown” cause, after lockdown, underreporting may be possible for other coding variables. This is a nationwide analysis and some differences by region may not be captured. Peru has tremendous diversity of lifestyle between coastal, mountain and jungle regions, and data come from large cities and small rural communities with radically different rates of events. Competing risk due to COVID-19 is also a possibility although most of the external deaths occur in the younger population, and not necessarily in the population at risk of dying because of COVID-19. For suicide, however, the populations may overlap to a greater extent (Mamun and Griffiths, 2020). Our analysis only considers the beginning and end of the lockdown thus the sudden initial drop that we have described may be accompanied by a sudden increase after the measures are lifted and a later follow-up analysis would be informative.

There is an urgency to consider and understand the myriad indirect mortality consequences of the policies adopted to respond to COVID-19. It is expected that some time after the lockdowns are completely lifted around the world, the lives lost from the impacts of these various policies on the economy, lifestyle, and mental health will outweigh the number of lives lost directly from infection. Indicators of this broad impact, including the types of external deaths studied here, will be crucial for future decision-making (VanderWeele, 2020).

5. Conclusions

Lockdown due to COVID-19 has impacted the rates of external deaths, showing a sudden drop after its implementation. The biggest change was seen in deaths related to traffic accidents. This initial drop should not be encouraging, since just as there was a marked drop at the beginning, it is likely to be an equally sharp increase after the lockdown is lifted and the economic activities are resumed. The patterns for suicide and homicide are less intuitive, however, and reveal important clues about the causes and characteristics of these events. There is an urgency for implementing a comprehensive response service for mental health during the pandemic, those services could be enhanced by the surveillance of factors contributing to suicidal behaviors as well as suicide trends in vulnerable populations. In the same way, assistance and prevention services against violence against women could benefit from close monitoring of feminicides and other types of violence. Usual intervention efforts need to be intensified during the lockdown and plan for when the lockdown ends, as a rebound effect might be expected. Policies should take into consideration other aspects of health that might be overlooked during this pandemic.

Credit author statement

RCA: Conception and design; Data Analysis; Writing; Review and Editing.

JK: Conception and design; Writing; Review and Editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Renzo Calderon-Anyosa: No Conflict of Interest.

Jay S Kaufman: No Conflict of Interest.

Financial disclosure: RCA was supported by a Tomlinson Doctoral Fellowship. No other funding was received.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Usama Bilal, MD PhD for his generous comments that helped to improve the current manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix Fig. 1.

Non-external death trends before and during the lockdown by sex. The solid red line corresponds to the LOESS smoother with 0.6 span in men and the blue line to the LOESS smoother with 0.6 span in women. The vertical black dashed line corresponds to the beginning of the lockdown (March 16, 2020) and the grey shading to the lockdown period and ligther grey to the relaxation of lockdown measures.

References

- Alfano V., Ercolano S. The efficacy of lockdown against COVID-19: a cross-country panel analysis. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00596-3. June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Risco A., Mejia C.R., Delgado-Zegarra J., et al. The Peru approach against the COVID-19 Infodemic: insights and strategies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0536. June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby M.P.J. Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Sci. 2020;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher J, Horwitz B. It's Been ‘Such a Weird Year.’ That's Also Reflected in Crime Statistics. The New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/06/upshot/murders-rising-crime-coronavirus.html. Published July 6, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020.

- Ayittey F.K., Ayittey M.K., Chiwero N.B., Kamasah J.S., Dzuvor C. Economic impacts of Wuhan 2019-nCoV on China and the world. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(5):473–475. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balhara Y.P.S., Kattula D., Singh S., Chukkali S., Bhargava R. Impact of lockdown following COVID-19 on the gaming behavior of college students. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64(Supplement):S172–S176. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_465_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole B., Mulder R.T., Frampton C.M., Boden J.M., Newton-Howes G., Bell C.J. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2018;213(6):716–722. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan A.K.M.I., Sakib N., Pakpour A.H., Griffiths M.D., Mamun M.A. COVID-19-related suicides in Bangladesh due to lockdown and economic factors: case study evidence from media reports. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00307-y. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campedelli G.M., Aziani A., Favarin S. Exploring the Effect of 2019-nCoV Containment Policies on Crime: The Case of Los Angeles. ArXiv200311021 Econ Q-Fin Stat. 2020 doi: 10.31219/osf.io/gcpq8. March. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casana-Jara K.M. Características de la muerte de mujeres por violencia según las necropsias realizadas en la morgue del Callao. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública. 2020;37(2):297–301. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2020.372.5111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Yip P.S.F. A revisit on older adults suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1231–1238. doi: 10.1002/gps.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crime G. Crime and Contagion: The Impact of a Pandemic on Organized Crime. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved April 25, 2020.; 2020.

- Crimen cae en calles de Latinoamérica en tiempos de COVID-19. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/79e12fe6ab9d4db8bbba247048f9f7fc. Published April 10, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Decreto Supremo N° 044–2020-PCM. 2020March . https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pcm/normas-legales/460472-044-2020-pcm. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- Decreto Supremo N° 116–-2020-PCM 2020. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pcm/normas-legales/738529-116-2020-pcm June.

- Drugs UNO on, Crime . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2019. Global Study on Homicide 2019: Executive Summary. [Google Scholar]

- Dsouza D.D., Quadros S., Hyderabadwala Z.J., Mamun M.A. Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113145. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer O. Covid-19 hot spots appear across Latin America. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerli A.G., Centanni S., Miozzo M.R., et al. COVID-19 mortality rates in the European Union, Switzerland, and the UK: effect of timeliness, lockdown rigidity, and population density. Minerva Med. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.20.06702-6. June. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Google LLC. Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/data_documentation.html. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- Griffiths M.D., Mamun M.A. COVID-19 suicidal behavior among couples and suicide pacts: case study evidence from press reports. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D., Appleby L., Arensman E., et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D., Appleby L., Arensman E., et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Espino C, others. Perú: brechas de género 2018. Avances hacia la igualdad de hombres y mujeres. 2018.

- Hawley S., Ali M.S., Berencsi K., Judge A., Prieto-Alhambra D. Sample size and power considerations for ordinary least squares interrupted time series analysis: a simulation study. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:197. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S176723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Información de Fallecidos del Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones – SINADEF, 2020, [Ministerio de Salud] | Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos. https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/informaci%C3%B3n-de-fallecidos-del-sistema-inform%C3%A1tico-nacional-de-defunciones-sinadef-ministerio. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- Información de Fallecidos del Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones SINADEF, 2020, [Ministerio de Salud] | Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos. https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/informaci%C3%B3n-de-fallecidos-del-sistema-inform%C3%A1tico-nacional-de-defunciones-sinadef-ministerio. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica. Situación del mercado laboral en Lima Metropolitana. http://m.inei.gob.pe/biblioteca-virtual/boletines/informe-de-empleo/1/#lista. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Islam S.M.D.-U., Bodrud-Doza Md, Khan R.M., Haque MdA, Mamun M.A. Exploring COVID-19 stress and its factors in Bangladesh: a perception-based study. Heliyon. 2020;6(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerimray A., Baimatova N., Ibragimova O.P., et al. Assessing air quality changes in large cities during COVID-19 lockdowns: the impacts of traffic-free urban conditions in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Sci Total Environ. 2020;730:139179. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Taylor E.C., Cloonan S.A., Dailey N.S. Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R., Saxena S., Levav I., Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004;82:858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H., Khosrawipour V., Kocbach P., et al. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon D.A., Shkolnikov V.M., Smeeth L., Magnus P., Pechholdová M., Jarvis C.I. COVID-19: a need for real-time monitoring of weekly excess deaths. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10234) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie E, Wilson R. Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Available SSRN 3600646. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mamun M.A., Griffiths M.D. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? – the forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., Chandrima R.M., Griffiths M.D. Mother and son suicide pact due to COVID-19-related online learning issues in Bangladesh: an unusual case report. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00362-5. July. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., Bodrud-Doza Md, Griffiths M.D. Hospital suicide due to non-treatment by healthcare staff fearing COVID-19 infection in Bangladesh? Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;54:102295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., AKMI Bhuiyan, MdD Manzar. The first COVID-19 infanticide-suicide case: Financial crisis and fear of COVID-19 infection are the causative factors. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;54:102365. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzar M.D., Albougami A., Usman N., Mamun M.A. 2020. COVID-19 Suicide among Adolescents and Youths during the Lockdown: An Exploratory Study Based on Media Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques E.S., de Moraes C.L., Hasselmann M.H., Deslandes S.F., Reichenheim M.E. Violence against women, children, and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: overview, contributing factors, and mitigating measures. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(4) doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00074420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrajt L., Leung T. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Social Distancing Interventions to Delay or Flatten the Epidemic Curve of Coronavirus Disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8) doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113104. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINSA Guía técnica para el correcto llenado del Certificado de Defunción. 2018. http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/MINSA/4459.pdf

- Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., et al. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. J Crim Justice. 2020;68:101692. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monjur MR. COVID-19 and suicides: the urban poor in Bangladesh. Aust N Z J Psychiatry., June 2020:0004867420937769. doi: 10.1177/0004867420937769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Morris D., Rogers M., Kissmer N., Du Preez A., Dufourq N. Impact of lockdown measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic on the burden of trauma presentations to a regional emergency department in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Afr J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.06.005. June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta Angelica. 1st ed. Lima Perú; La Siniestra Ensayos: 2019. La Biologia Del Odio: Retoricas Fundamentalistas y Otras Violencias de Genero. [Google Scholar]

- Neil J. Domestic violence and COVID-19: Our hidden epidemic. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49 doi: 10.31128/AJGP-COVID-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez J.H., Sallent A., Lakhani K., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency traumatology service: experience at a tertiary trauma Centre in Spain. Injury. 2020;51(7):1414–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERÚ – INEI Perú: Resultados Definitivos de los Censos Nacionales. 2017. https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1544/

- Peru: REUNIS. Repositorio Único Nacional de Información en Salud - Ministerio de Salud, 2020. http://www.minsa.gob.pe/reunis/index.asp?op=51&box=712&item=712. Published 2019. Accessed July 9, 2020.

- Ribeiro E., Borges D., Cano I. Calidad de los datos de homicidio en América Latina. Bras Lab Análisis Violencia–Universidad Estado Rio Jan. 2015:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco M.A., Caputo F., Ricci P., et al. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on domestic violence: the dark side of home isolation during quarantine. Med Leg J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0025817220930553. June. 25817220930553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakelliadis E.I., Katsos K.D., Zouzia E.I., Spiliopoulou C.A., Tsiodras S. Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on characteristics of autopsy cases in Greece. Comparison between 2019 and 2020. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020;313:110365. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayegh S., Malpede M. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2020. Staying Home Saves Lives, Really! [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. Resilience as a focus of suicide research and prevention. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019;140(2):169–180. doi: 10.1111/acps.13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. COVID-19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide. Sleep Med. 2020;70:124. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM Int J Med. 2020;113(10):707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoib S., Nagendrappa S., Grigo O., Rehman S., Ransing R. Factors associated with COVID-19 outbreak-related suicides in India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;53:102223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickle B., Felson M. Crime rates in a pandemic: the largest criminological experiment in history. Am. J. Crim. Justice. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09546-0. June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D., Basu S., Suhrcke M., Coutts A., McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Jain A. COVID 2019-suicides: A global psychological pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062. April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Thakur K., Kumar N., Sharma N. Effect of the pandemic and lockdown on mental health of children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2020;1 doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03308-w. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O’Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S.L., Karahalios A., Forbes A.B., et al. Design characteristics and statistical methods used in interrupted time series studies evaluating public health interventions: a review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020;122:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele T.J. Challenges estimating Total lives lost in COVID-19 decisions: consideration of mortality related to unemployment, social isolation, and depression. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12187. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Herrera J., Pardo Ruiz K., Garro Nuñez G., et al. Resultados preliminares del fortalecimiento del sistema informático nacional de defunciones. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2018;35(3):505–514. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2018.353.3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira P.R., Garcia L.P., Maciel E.L.N. The increase in domestic violence during the social isolation: what does it reveals? J Epidemiol. 2020;23 doi: 10.1590/1980-549720200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wei H., Zhou L. Hotline services in China during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:125–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman I.M. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(2):240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1992.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women U. 2020. COVID-19 and Ending Violence against Women and Girls. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Miao M., Lim J., Li M., Nie S., Zhang X. Is Lockdown Bad for Social Anxiety in COVID-19 Regions?: A National Study in The SOR Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Snoswell C.L., Harding L.E., et al. The role of Telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(4):377–379. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylke J.W., Bauchner H. Mortality and morbidity: the measure of a pandemic. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11761. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]