Abstract

Cancer is one of the most severe disease burdens in modern times, with an estimated increase in the number of patients diagnosed globally from 18.1 million in 2018 to 23.6 million in 2030. Despite a significant progress achieved by conventional therapies, they have limitations and are still far from ideal. Therefore, safe, effective and widely-applicable treatments are urgently needed. Over the past decades, the development of novel delivery approaches based on membrane-core (MC) nanostructures for transporting chemotherapeutics, nucleic acids and immunomodulators has significantly improved anticancer efficacy and reduced side effects. In this review, the formulation strategies based on MC nanostructures for delivery of anticancer drug are described, and recent advances in the application of MC nanoformulations to overcome the delivery hurdles for clinical translation are discussed.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Hybrid nanostructured materials, Drug delivery, Tumor microenvironment, Combination therapy

1. Introduction

Cancer is among the leading causes of mortality across the world with an estimated 9.6 million deaths in 2018, and the number of patients newly diagnosed with cancer is expected to rise to 23.6 million in 2030 (www.cancer.gov). The surgical, radiotherapeutic and chemotherapeutic strategies may provide curable means for cancer at early stages, but the prognosis is still poor for patients with advanced and metastatic cancers [1]. Recent advances in the development of small molecule inhibitors, nucleic acids and immunomodulators have significantly revolutionized the field of cancer therapy, but the application of these therapies to patients is retarded by limitations such as drug resistance, non-specific delivery, and toxicity [2]. It is well established that the clinical translation of these anticancer agents is highly dependent on the success of the delivery approach.

In recent years, substantial research has been undertaken regarding the design and assessment of nanoparticle (NP)-based delivery carriers for providing safe, effective and patient-acceptable therapeutic approaches [3]. Among these, the membrane-core (MC, also known as core-shell) nanostructure becomes a promising platform for developing cancer nanomedicine. This review describes MC formulation strategies for cancer therapy, and the barriers associated with in vivo delivery. In addition, the development of MC NPs under the investigation for cancer nanomedicine is described, with an emphasis on those designed to promise clinical translation.

2. Membrane-Core Nanostructured Formulations

MC NPs are generally characterized as a hybrid nanostructured system comprising inner core and exterior membrane, which can facilitate the combination of materials with distinctive physical, chemical, and biological properties (Fig. 1). This ordered assembly nanostructure is formed through chemical bonds and/or physical interactions between inner core and exterior membrane. The classes, properties and synthesis approaches of MC NPs have been substantially reviewed elsewhere [4]. The MC NPs opens up the potential for design of multifunctional NPs that are widely recognized favorable for biomedical application as compared to NPs with single functions. From drug delivery point of view, the core materials can efficiently encapsulate therapeutic cargos, and the membrane materials may provide benefits such as the reduction in consumption of precious materials, the overall stability and dispersibility, a controlled release of drugs inside the core, the surface modification with functional groups, and so on. The delivery formulations with MC nanostructure are summarized in Table 1, and selected recent examples are discussed below based on the material components.

Fig. 1.

Delivery strategies designed using membrane-core (MC) nanostructures to overcome the barriers for clinical translation. (A) The formulation of MC nanoparticles (NPs) are generally described as a hybrid nanostructured system comprising organic, inorganic, and biological materials. Following the ordered assembly process, MC NPs commonly demonstrate hybrid nanostructures. Physicochemical factors such as particle size, surface charge and stability are controllable during the formulation in order to facilitate delivery of MC NPs. (B) The combination of materials with distinct properties in MC NPs facilitates the design of multifunctional delivery systems. The surface functionalization furthers the potential of MC NPs as ‘smart’ drug delivery carriers for physiological stability, stimuli-responsive activity, cell- and tissue-targeted delivery, and controlled release. (C) Due to the complexity of cancer such as the metastasis, resistance to certain drugs and genetic diversity, the use of more than one treatment modality is considered a hallmark of cancer therapy. The co-formulation of distinct therapeutic components may be achieved using MC NPs. (D) Barriers to the clinical translation such as instability in the blood circulation, low tumor distribution, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, nanotoxicity and manufacture control may be potentially overcome by design of “smart” MC NPs.

Table 1.

Recent selective studies for delivery of anticancer cargos using membrane-core (MC) NPs including: formulation material, therapeutic cargo, tumor model, route of administration, and endpoint comment. (I.V. = intravenous; I.P. = intraperitoneal; I.T. = intratumoral; S.C. = subcutaneous; O.T. = orthotopic; M.T. = metastatic).

| Formulation material | Therapeutic cargo | Tumor model & Route of administration | Endpoint comment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | ||||

| Lipid-protamine-DNA (LPD) NPs | Plasmid DNA (expression of PD-L1 trap fusion protein) | CT26-FL3 O.T. syngeneic colorectal cancer & I.V. injection | The aminoethyl anisamide (AEAA)-targeted LPD NPs containing plasmid DNA produced PD-L1 trap transiently and locally in tumors, which synergized with oxaliplatin for tumor inhibition. | [5] |

| LPD NPs | Plasmid DNA (expression of LPS trap fusion protein) | CT26-FL3 O.T. and M.T. syngeneic colorectal cancer & I.V. injection | The AEAA-targeted LPD NPs containing plasmid DNA expressed LPS trap in tumors, and achieved synergic tumor inhibition when combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody. | [6] |

| LPD NPs | Plasmid DNA (expression of IL-10 and CXCL12 trap fusion proteins) | KPC O.T. syngeneic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma & I.V. injection | The AEAA-targeted LPD NPs containing plasmid DNA produced IL-10 and CXCL12 traps in tumors, achieving therapeutic efficacy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. | [7] |

| Lipid-calcium-phosphate (LCP) NPs | Plasmid DNA (expression of relaxin protein) | CT26-FL3 M.T. syngeneic colorectal cancer & I.V. injection | The AEAA-targeted LCP NPs containing plasmid DNA expressed relaxin protein inside the tumor microenvironment, generating anticancer efficacy against liver metastasis. | [8] |

| LCP NPs | Plasmid DNA (expression of CXCL12 trap fusion protein) | CT26-FL3 and 4T1 M.T. syngeneic liver metastasis & I.V. injection | The AEAA-targeted LCP NPs containing plasmid DNA produced CXCL12 trap in tumors, generating anticancer efficacy against liver metastasis. | [9] |

| Lipid NPs (LNPs) | Platinum derivative; miRNA (miR-655-3p) | HCT116-L2T M.T. xenogeneic liver tumor & I.V. injection | Liposomal NPs containing platinum derivative and miRNA significantly reduced tumor burden in a xenogeneic hepatic metastatic model without any observable toxicity. | [10] |

| LNPs | Paclitaxel (PTX); Thioridazine (THZ, anti-CSC agent); HY19991 (HY, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor) | MCF-7 O.T. and M.T. xenogeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | PTX was loaded into PEG-poly [(1,4-butanediol)-diacrylate-β-N,N-diisopropylethylenediamine] (PDB) to form PDB/PTX. The PDB/PTX along with THZ and HY were encapsulated into a micelle-liposome nanostructure consisting of PEG-peptide (PLGLAG)-vitamin E succinate (PPV), cholesterol and soybean phosphatidylcholine, which significantly increased the survival of tumor-bearing mice. | [11] |

| LNPs | Platinum derivative Dihydroartemisinin (DHA, a ROS-inducing drug) | CT26 S.C. syngeneic colorectal cancer & I.P. injection | LNPs containing platinum derivative and DHA synergistically suppressed tumor growth in mice. | [12] |

| LNPs | mRNA vaccines | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma and TC-1 S.C. syngeneic lung tumor & S.C. injection | LNPs containing mRNA vaccines induced a robust immune response, and were able to prolong survival of melanoma and human papillomavirus E7 tumor-bearing mice. | [13] |

| LNPs | siRNA against PLK1 | Granta-519 O.T. xenogeneic lymphoma & I.V. injection | A nanoplatform was developed by siRNA-loaded LNPs that were conjugated with a membrane-anchored lipoprotein (it can interact with the antibody crystallizable fragment domain). The antibody-targeted siRNA-loaded LNPs significantly prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice. | [14] |

| LNPs | siRNA against colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The dual-targeting LNPs significantly impaired the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) by blocking CSF-1R for tumor inhibition. | [15] |

| LNPs | CSF-1R inhibitor (conjugated BLZ945, AK750); Anti-SIRPα antibody | 4 T1 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer and B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The LNPs could significantly reprogram TAMs by inhibiting CSF-1R and SIRPα for controlled tumor growth. | [16] |

| LNPs | CSF1R inhibiting amphiphile (conjugated BLZ945); SHP2 inhibitor (SHP099) | 4T1 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer and B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The LNPs could effectively induce cancer immunotherapy by supressing CSF-1R and SHP2 for tumor regression. | [17] |

| Polymeric NPs | ||||

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)/poly (lactic acid) (PLA) NPs | Melan-A/MART-1 peptides (melanoma-associated antigens); Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists [CpG and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA)] | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & S.C. injection | The mannosylated PLGA/PLA NP was co-loaded with melanoma-associated antigens and TLR agonists for delivery of DCs through both phagocytosis- and ligand-mediated pathways. The combination of nanovaccine with anti-PD-1 and anti-OX40 antibodies successfully achieved immunotherapeutic efficacy for melanoma. | [18] |

| PLGA/ dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) NPs | siRNA against POLR2A | MDA-MB-453 O.T. xenogeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | The chitosan was modified with guanidine (CG). The guanidine moiety of CG was reacted with CO2 to form CG-CO2 in a pH-dependent manner, which could store CO2 at neutral pH for release at acidic environments. The siRNA/CG-CO2 core was encapsulated with PLGA and DPPC to form a MC NP, which significantly inhibited breast cancer growth. | [19] |

| PLGA NPs | Indocyanine green (ICG); Titanium dioxide (TiO2) | 4T1 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer and B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The mannose-targeted PLGA NPs containing ICG and TiO2 significantly reprogrammed TAMs to the antitumor M1 phenotype, which induced cytotoxic T cell infiltration for antitumor responses. | [20] |

| PLGA NPs | Poly (I:C); Resiquimod (R848); CCL20 (MIP3α) | TC-1 S.C. syngeneic lung carcinoma & S.C. injection | The co-delivery of poly(I:C), R848 and MIP3α using PLGA NPs induced a favorable vaccination for T cell infiltration against tumors. | [21] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-modified NPs | Magnesium silicide [Mg2Si, a deoxygenation agent (DOA)] | 4T1 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer & S.C. injection | The PVP-modified NPs containing Mg2Si produced the aggregation of silicon oxide (SiO2) in tumors, resulting in blockage of tumor blood capillaries and preventing tumors from the oxygen supply. | [22] |

| Cyclodextrin-lysine NPs | Resiquimod (R848) | MC38 S.C. syngeneic colon cancer and B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The R848-loaded NPs led to efficient drug delivery to TAMs, which remodeled the tumor microenvironment for controlled tumor growth and against tumor re-challenge. | [23] |

| Poly(β-amino ester) NPs | mRNAs encoding interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) and IKKβ (a kinase that phosphorylates and activates IRF5) | ID8 M.T. syngeneic ovarian cancer; B16F10 M.T. syngeneic melanoma; DF-1 O.T. xenogeneic glioblastoma & I.V. injection | The co-expression of IRF5 and IKKβ using Di-mannose targeted polymeric NPs significantly reversed the immunosuppressive TAMs for inducing anti-tumor immunity and promoting tumor regression. | [24] |

| Poly(β-amino ester) NPs | Mitoxantrone (MIT); Celastrol (CEL) | BPD6 S.C. syngeneic desmoplastic melanoma & I.V. injection | A chemo-immunotherapeutic strategy was developed by the co-delivery of MIT and CEL using AEAA-targeted polymeric NPs, which significantly reshaped the fibrotic and immunosuppressive TME for tumor inhibition. | [25] |

| PEG-block-[(2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate)-co-(butyl methacrylate)-co-(pyridyl disulfide ethyl methacrylate)] (PEG-DBP), 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DEAEMA), hydrophobic butyl methacrylate (BMA), and thiol-reactive pyridyl disulfide ethyl methacrylate (PDSMA) copolymer NPs | 2′3′-cGAMP (cyclic dinucleotide agonists) | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.T. and I.V. injections | The administration of NPs containing 2′3′-cGAMP significantly inhibited tumor growth, increased animal survival, improved response to immune checkpoint blockage, and induced immunological memory for protection of tumor re-challenge. | [26] |

| Inorganic NPs | ||||

| Au nanorods@mesoporuous silica NPs (MSNs) | Zoledronic acid (ZOL) | 4 T1 M.T. syngeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | Au@MSNs-ZOL demonstrated in vivo bone-targeting capacity due to the affinity of ZOL with the bone. When triggered by NIR, Au nanorods inside Au@MSNs-ZOL achieved PTT, resulting in tumor inhibition and pain relief in mice. The PTT also promoted the ZOL release from the surface of Au@MSNs-ZOL, and the released ZOL inhibited farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPP synthase) for suppression of osteoclasts. | [27] |

| Carbon-dot NPs | Au atoms; Cinnamaldehyde (CA, for ROS generation) | HepG-2 S.C. xenogeneic liver tumor and patient-derived O.T. xenogeneic liver tumor & I.T. injection | Carbon-dot NPs were used for package of Au atoms, and the surface of Au-containing NPs was subsequently modified with triphenylphosphine (TPP, can target mitochondrion) and CA achieving MitoCAT-g. The MitoCAT-g released CA at acidic endosomes for ROS generation in mitochondria. Au atoms within NPs reduced the level of GSH in mitochondria by forming Au—S interactions with GSH. These resulted in tumor inhibition in mice xenografted with either cultured HepG-2 cells or resected liver tumors. | [28] |

| CaCO3 NPs | Anti-CD47 antibody | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & S.C. administration | The fibrinogen solution containing anti-CD47 antibody-loaded CaCO3 NPs and thrombin solution were sprayed and mixed within the tumor resection cavity after surgery to form an immunotherapeutic fibrin gel in situ, which achieved blockade of CD47 signaling pathways for immunotherapy therapy. | [29] |

| CaO2@ZIF-67 NPs | CaO2 (a material for oxygen supply); ZIF-67 (a material for generation of hydroxyl radicals); DOX | MCF-7 S.C. xenogeneic breast cancer & I.T. injection | When injected into tumors, CaO2@DOX@ZIF-67 NPs could produce O2 and H2O2 and release DOX for chemodynamic therapy and chemotherapy. | [30] |

| Hollow manganese dioxide (H-MnO2) NPs | Chlorine e6 (Ce6); DOX | 4T1 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | The PEGylated H-MnO2 NPs could release Ce6 and DOX at acidic environments within tumors for Ce6-induced decomposition of tumor H2O2 to relieve tumor hypoxia and for generating DOX-mediated chemotherapy in mice. | [31] |

| Iron chelated melanin-like NPs | Polydopamine (PDA) | CT26 S.C. syngeneic colon cancer mouse and 4 T1 O.T. syngeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | The iron chelated melanin-like nanoformulation repolarized M2 cells to M1 ones and induced photothermal therapy to release tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) for the presentation to APCs, leading to the controlled tumor growth and limited malignant metastasis. | [32] |

| Biomimetic carriers | ||||

| Tumor-derived antigenic microparticles containing lipid NPs and iron oxide NPs | CpG oligoDNA | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The tumor-derived antigenic microparticles (T-MPs) were developed to co-load CpG-lipid NPs and iron oxide NPs. The resultant formulation led to tumor antigen-specific immune response and induced infiltration of cytotoxic T cells for conversion from a “cold” tumor into a “hot” one. | [33] |

| Cancer cell membrane coated PLGA NPs | CpG oligoDNA | B16F10 S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The CpG-loaded PLGA NPs were surface coated with cancer cell membranes, and the resultant NPs significantly induced cancer immunotherapy. | [34] |

| Cancer cell membrane coated Poly (D,l-lactide-co-glycolide) NPs | Imiquimod (R837, TLR7 agonist) | B16-OVA S.C. syngeneic melanoma & I.V. injection | The poly(D,l-lactide-co-glycolide) NPs were first loaded with R837 and further coated with cancer cell membranes. The obtained nanovaccine showed enhanced uptake by APCs, significantly inducing antitumor immune responses. | [35] |

| Cancer cell membrane coated poly (caprolactone) (PCL)/Pluronic-copolymer F68 NPs | PTX | 4 T1 O.T. and M.T. syngeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | The cancer cell membrane coated nanoformulation was selectively accumulated into primary and metastatic sites of orthotopic and metastatic mice, significantly inhibiting tumor growth. | [36] |

| Cancer cell membrane coated MSNs | Daunorubicin (DNR); Anti-TFGβRII antibody | NALM-6 O.T. xenogeneic acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) & I.V. injection | The DNR-loaded MSNs were surface coated with leukemia cell membranes (they were modified with anti-TFGβRII antibody). This nanosystem could home to the bone marrow, in which the antibody was released to block TGF signaling pathway for enhanced chemotherapy of DNR. | [37] |

| Platelet membrane coated dextran NPs | PTX | MDA-MB-231 S.C. xenogeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | The RGD-nanogel containing TNF-α triggered vascular damage by activating the inflammation cascades. The platelet membrane coated PTX-loaded dextran NPs were then accumulated in tumors due to relay action between vascular damage signals and platelets for PTX release for tumors. | [38] |

| Bacteria-secreted outer membrane coated PLGA NPs | PBIBDF-BT (PBT, a PTT transducer); Cisplatin derivative | EMT6 S.C. syngeneic breast cancer and CT26 S.C. colorectal cancer & I.V. injection | The PBT and cisplatin derivative were encapsulated within PEG-PLGA, respectively. The PEG-PLGA/PBT and PEG-PLGA/cisplatin were surface coated with bacteria-secreted outer membranes, respectively. The resultant NPs could be internalized by neutrophils. When neutrophils penetrated into tumors, NPs were released in response to inflammatory stimuli and then internalized by cancer cells for PTT and chemotherapy. | [39] |

| Lipoprotein-based NPs | DiOC18(7) (a PTT agent); Mertansine (a microtubulin inhibitor) | 4 T1 O.T. and M.T. syngeneic breast cancer & I.V. injection | A lipoprotein-based (bLP) NP containing photothermal agent of DiOC18(7) (termed D-bLP) was developed for PTT to reshape the stromal TME. Following laser irradiation onto tumors, D-bLP significantly improved the accessibility of second-wave bLP NP containing mertansine (termed M-bLP) into cancer cells, which produced profound tumor suppression and metastasis inhibition of 4 T1 breast cancer models. | [40] |

Table 1. [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40].

2.1. Lipids

Lipid-based NPs are generally constructed by a combination of cationic, neutral and/or anionic lipids, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-conjugated lipids, and lipopolymers [41]. Liposomes with a particle size of ~50 to 200 nm are the classic example of lipid-based NPs, and they are generally characterized as vesicles with one lipid bilayer enclosing an aqueous space. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs may be encapsulated into lipid membrane and aqueous core, respectively, forming MC nanostructures (Fig. 2A). The evolution of liposomal NPs including the formulation approaches, solubility/bioavailability of drugs, and in vitro/in vivo delivery efficacy, has been extensively reviewed [42] [43] [44] [45]. In addition, nanoscale colloidal carriers made up of solid lipids (high melting fat matrix) namely solid lipid NPs (SLNs) have recently emerged as the new generation of lipid-based nanocarriers [46]. SLNs are usually fabricated by physiologically related lipids, which form a wax or solid core that is stabilized by surfactants (emulsifiers). Hydrophobic components can be dissolved or dispersed inside the core achieving MC nanostructures (Fig. 2B and C). SLNs provide favorable properties such as high drug loading, stability in nanometer size, and controlled/sustained release of cargos [47] [48], demonstrating great potential as a substitute of liposomes for drug delivery [49] [50] [51] [52].

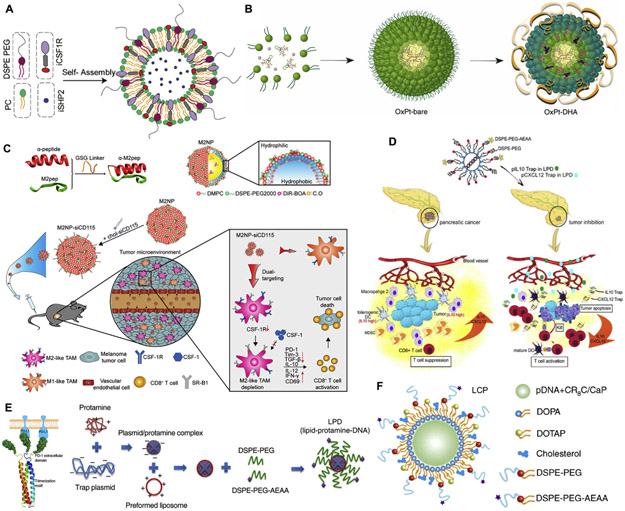

Fig. 2.

Delivery of anticancer agents using lipid-based MC NPs. (A) Liposomal NPs containing CSF1R- and SHP2-inhibitors for enhanced cytotoxicity and phagocytosis of TAMs (Adapted from [17], copyright 2019 Wiley). (B) Lipid-based NPs containing platinum derivative and Dihydroartemisinin (DHA, ROS-mediated drug) for synergistic inhibition of colorectal cancer (CRC) when combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody (Adapted from [12], copyright 2019 Nature Publishing Group). (C) Lipid-based NPs containing CSF-1R siRNA to reprogram TAMs for anticancer effects in melanoma (Adapted from [15], copyright 2017 American Chemical Society). (D) Lipid-protamine-DNA (LPD) NPs containing trap plasmids of IL-10 and CXCL12 for immunotherapeutic effects against pancreatic carcinoma (Adapted from [7], copyright 2019 American Chemical Society). (E) LPD NPs containing PD-L1 trap plasmid for synergistic cancer immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy in CRC (Adapted from [6], copyright 2018 Wiley). (F) Lipid-calcium-phosphate (LCP) NPs containing relaxin plasmid to achieve antitumor efficacy in combination with PD-L1 blockage against metastasis in the liver (Adapted from [8], copyright 2019 Nature Publishing Group).

In addition, cationic lipids or neutral lipids along with polycation, can condense nucleic acids via electrostatic interaction to form the MC nanostructured complex (lipopolyplex) [53]. For example, a lipid-polycation-DNA (LPD) formulation has been developed by Huang and colleagues for gene delivery. To prepare this formulation DNA was condensed by high molecular weight cationic polymers (e.g. protamine) into an anionic nanosized core, and the resultant core was coated by cationic lipids/liposomes [e.g. 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) and cholesterol] and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-polyethylene glycol (DSPE-PEG) conjugated with aminoethyl anisamide (AEAA, it is used for targeting sigma-1 receptors that are overexpressed on cancer cells [54]), achieving LPD with MC nanostructure (Fig. 2D and E). LPD has remarkably promoted the transfection, steric stabilization, and tumor specificity [55] [56] [57]. Recently, the transfection of plasmids encoded with small antibody-like proteins (termed traps) using LPD has demonstrated great potential for immunotherapy by remodeling the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) [55] [56] [57]. For example, an LPD containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) trap plasmid effectively blocked LPS inside tumors of mice with orthotopic and metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC), which significantly mitigated tumor growth and liver metastasis [6]. This anticancer effect was accompanied with the activation of immunogenic cells including CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) and the reduction of immunosuppressive cells including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), suggesting the importance of LPS blockade to induce immunotherapeutic responses in the gut-liver immune axis (Fig. 2E).

It has been reported that a calcium phosphate [Ca3(PO4)2] precipitate was produced by the interaction between calcium ions of calcium chloride (CaCl2) and phosphate groups of DNA, and the resultant precipitate significantly enhanced the gene transfection in cultured cells [58]. Although Ca3(PO4)2-based transfection approaches have been used for delivery of nucleic acids, limitations such as uncontrollable precipitation growth, instability and insolubility hinder the in vivo application [59]. A lipid-calcium-phosphate (LCP) formulation was therefore developed by Huang and colleagues to address these issues. To prepare LCP, two water-in-oil microemulsions containing CaCl2/nucleic acids and Na2HPO4, respectively, were mixed to form Ca3 (PO4)2 amorphous precipitate in which nucleic acids are entrapped [60]. The Ca3(PO4)2-nucleic acid core was stabilized by 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DOPA). Subsequently, the stabilized core was coated with DOTAP, cholesterol and DSPE-PEG-AEAA to form LCP with a MC nanostructure [61]. LCP has been applied as a versatile gene delivery construct in a number of cancer mouse models [62] [63] [64]. For example, liver metastasis is often evident when activated hepatic stellate cells (aHSC) form fibrosis in the liver [65]. Recently, it has been reported that relaxin (RLN, a peptide against fibrosis) may deactivate aHSCs for fibrosis resolution in the liver [66]. Thus, LCP was developed to deliver RLN plasmid into cancer cells and aHSCs inside metastatic sites in which the RLN protein was produced (Fig. 2F). As a consequent, the stromal TME was impaired by the RLN protein, significantly suppressing metastatic progression and promoting the animal survival [8].

The encapsulation of platinum-based drugs (e.g. cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin) into NPs is low due to the insolubility in both aqueous solutions and organic solvents. Recently, LCP-derived NPs have been developed by replacing the Ca3(PO4)2-nucleic acid core with the nanoprecipitate (which encapsulates platinum-based drugs) [67]. For example, a nanoprecipitate Pt(DACH).FnA (C26H35N9O7Pt) was formed by conjugation of [Pt(DACH)(H2O)2]2+ (the active form of oxaliplatin, OxP) and folinic acid [FnA, it can sensitize cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu)] [68]. The DOPA-stabilized nanoprecipitate was coated with DOTAP, cholesterol and DSPE-PEG-AEAA to form a MC NP (namely Nano-Folox). Due to the capacity of OxP to induce immunogenic cell death (ICD, it is able to induce the immune response to activate T lymphocytes for recognizing tumor-specific antigens [69]), Nano-Folox either alone or combined with 5-Fu successfully achieved chemo-immunotherapeutic effects in orthotopic and metastatic CRC mice without toxicity [68].

2.2. Polymers

Polymeric materials used for MC NPs mainly include poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [70] [71], poly(lactic acid) (or polylactide, PLA) [72] [73], Poly(β-amino ester) (PBAE) [74] [75], poly(amino acid) (PAA)/polypeptide [76] [77], polysaccharide (e.g. chitosan, alginate and hyaluronic acid) [78] [79], etc. Recent advances in polymerization approaches have significantly enabled the development of block copolymers with precise control over the architecture of individual polymeric components and with incorporation of different functions (e.g. responsive moieties, stealth groups, and targeting ligands) [80] [81][82]. A variety of formulation strategies based on the amphiphilic property of block copolymers, such as the oil-in-water (O/W) single emulsion process (for hydrophobic therapeutic cargos) and the water-in-oil-inwater (W/O/W) double emulsion method (for hydrophilic therapeutic cargos), have been used to form MC nanostructures [83]. Consequently, polymeric MC NPs have significantly improved solubility and bioavailability of drugs, facilitated targeted and controlled drug delivery, and mitigated toxicity and side effects (Table 1).

PLGA as a copolymer of lactic and glycolic acids (Fig. 3A and B) is one of the best-defined polymeric drug delivery carriers with respective to its biocompatible/biodegradable property, controllable release capability, and surface functionalization [84]. For example, the production of perivascular nitric oxide (NO) gradients may normalize tumor vessels, which can improve tumor response to anticancer agents [85]. However, a strategy for prolonged half-life, sustained release and targeted delivery of NO is currently lacking. Recently, a PLGA nanocarrier containing NO was developed to address these issues [86]. In this study, the dinitrosyl iron complex (DNIC, the NO donor) was encapsulated inside PLGA through the O/W single emulsion, and the surface of PLGA-DNIC core was stabilized with PEG. The resultant MC NP (termed NanoNO) could improve blood circulation by avoiding recognition of monocytes and macrophages and by preventing interaction of serum proteins. NanoNO demonstrated tumor accumulation, and subsequently provided the controlled and sustained release of NO from DNIC. Consequently, NanoNO at low-doses normalized tumor vessels and improved the efficacy of doxorubicin (DOX) in primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor and metastasis [86].

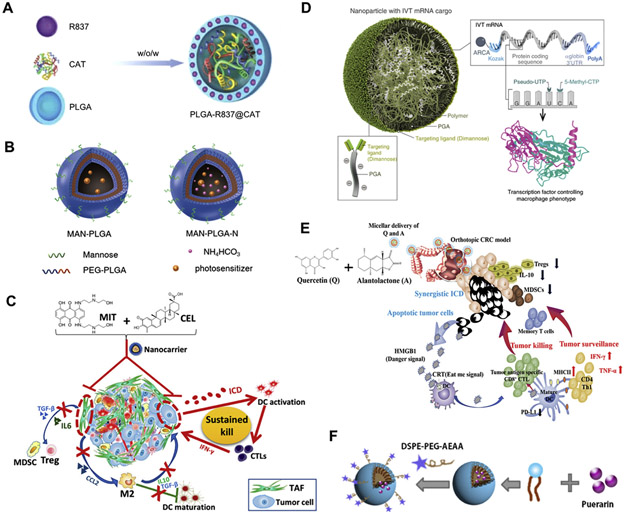

Fig. 3.

Delivery of anticancer agents using polymer-based MC NPs. (A) PLGA NPs containing catalase and imiquimod for enhanced radiotherapy and immunotherapy in breast tumor (Adapted from [87], copyright 2019 Wiley). (B) PLGA NPs containing indocyanine green and titanium dioxide for phototherapy and immunotherapy in melanoma and breast cancer (Adapted from [20], copyright 2018 American Chemical Society). (C) Poly(β-amino ester)-based NPs containing mitoxantrone and celastrol for chemo-immunotherapy in mice with desmoplastic melanoma for (Adapted from [25], copyright 2017 American Chemical Society). (D) Poly(β-amino ester) NPs containing IRF5 and IKKβ mRNAs for immunotherapy in ovarian cancer, melanoma, and glioblastoma (Adapted from [24], copyright 2019 Nature Publishing Group). (E) A nanoemulsion prepared using DSPE-PEG and D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS) for co-encapsulation of quercetin and alantolactone to achieve immunotherapeutic efficacy in CRC (Adapted from [89], copyright 2019 American Chemical Society). (F) The nanoemulsion prepared using lecithin from soybean and DSPE-PEG-AEAA for delivery of puerarin to induce synergistic chemo-immunotherapeutic effects with anti-PD-L1 antibody in breast cancer (Adapted from [140], copyright 2019 Elsevier). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

A PLGA NP was produced through W/O/W double emulsion to co-encapsulate catalase (Cat; it is a hydrophilic enzyme that can mediate the decomposition of H2O2 to generate oxygen) inside the aqueous core and imiquimod (R837; it is a water-insoluble Toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 agonist as an immune adjuvant) into the PLGA shell [87]. The resulting co-formulation (termed PLGA-Cat/R837) could tremendously enhance radiotherapeutic efficacy via reducing the hypoxia and remodeling the immunosuppressive TME (Fig. 3A). Consequently, PLGA-Cat/R837 induced favorable immunotherapeutic effects when combined with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) blockade, resulting in significantly stronger antitumor effect in breast tumor metastasis model [87].

An AEAA-targeted PEGylated PLGA NP (PLGA-PEG-AEAA) was produced for co-delivery of DOX and icaritin (ICT) to HCC [88]. In this study, ICT induced mitophagy and apoptosis in HCC cells, which improved DOX-mediated ICD effects. A MC nanostructure was achieved when DOX and ICT were co-encapsulated in the hydrophobic core of PLGA-PEG-AEAA via a solvent displacement process. The co-formulation demonstrated pH-sensitive drug release and enhanced blood circulation and tumor accumulation of drugs. As a result, the co-formulation was able to remodel the immunosuppressive TME and trigger a robust immune response, achieving satisfactory anti-HCC effect in an orthotopic HCC mouse model [88].

In addition to PLGA, a variety of polymeric materials have also been employed for design of MC NPs (Fig. 3C, D, E and F). For example, a poly (β-amino ester)-based NP with PEGylated AEAA was produced for co-encapsulation of mitoxantrone (an ICD inducer) and celastrol (a pentacyclic triterpene compound) to animals with desmoplastic melanoma mice (Fig. 3C). The nanoformulation significantly triggered immunotherapeutic responses, reprogrammed the immunosuppressive microenvironments, and promoted the animal survival [25]. In addition, a nanoemulsion was produced using D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS) and DSPE-PEG by the ethanol injection method for co-encapsulation of quercetin and alantolactone (Fig. 3E). The nanoemulsion with two drugs at the optimal ratio was capable of activating ICD-mediated antitumor immunity and modulating the immunosuppressive TME in CRC mice [89]. This simple and safe nanoemulsion therefore demonstrates great promise for clinical application for CRC.

2.3. Inorganic materials

A variety of inorganic materials including gold NPs (AuNPs), superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (SPIONs), silica NPs, quantum dots (QDs) and carbon nanotubes, have generated considerable attention for biomedical application [90] [91] [92] [93] [94]. For example, AuNPs and SPIONs have been used for cancer diagnosis and phototherapy (Fig. 4A and B), due to their tunable and highly sensitive optical, electronic, and magnetic properties [95] [96]. In addition, the surface of inorganic materials can be physically coated and/or chemically conjugated by organic/inorganic moieties with different properties and functions [97], facilitating the design of MC nanostructured carriers for transporting drugs, proteins, and genes (Table 1).

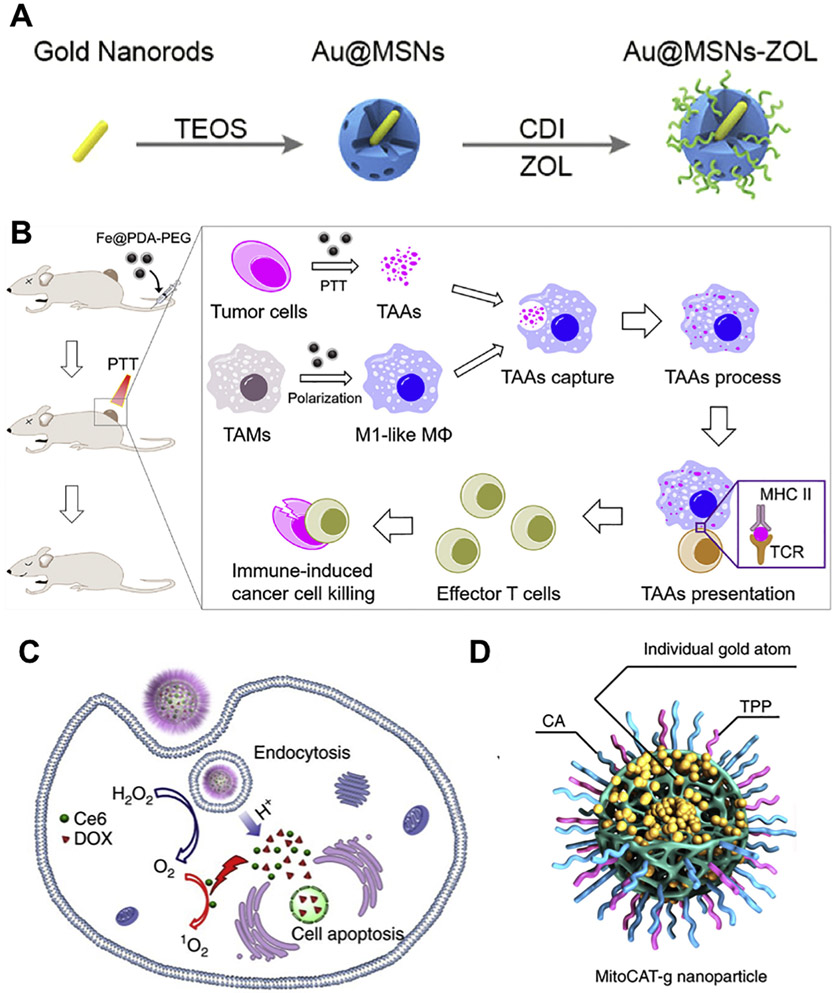

Fig. 4.

Delivery of anticancer agents using inorganic material-based MC NPs. (A) MSNs containing Au nanorods and zoledronic acid for photothermal therapy and chemotherapy in breast cancer (Adapted from [27], copyright 2019 American Chemical Society). (B) The iron chelated melanin-like NPs for photothermal therapy and immunotherapy in colorectal and breast cancers (Adapted from [32], copyright 2019 Elsevier). (C) Hollow MnO2 NPs for co-delivery of DOX and chlorine e6 for cancer chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy in breast tumor (Adapted from [31], copyright 2017 Nature Publishing Group). (D) Carbon-dot NPs containing Au atoms, cinnamaldehyde and triphenylphosphine for increasing ROS and decreasing GSH in liver tumors (modified from [28]).

Recently, a bone-targeted MC NP has been developed using inorganic materials for bone metastasis of breast cancer [27]. In this study, Au nanorods was encapsulated inside mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs) via a sol-gel method to achieve Au@MSNs. The surface of Au@MSNs was subsequently conjugated with zoledronic acid (ZOL) to produce Au@ MSNs-ZOL (Fig. 4A). Au@MSNs-ZOL demonstrated in vivo bone-targeting capacity due to strong affinity of ZOL with the bone. AuNPs may convert the absorbed light into heat that generates photothermal therapy (PTT) for cancer [98]. When triggered by near-infrared irradiation (NIR), Au nanorods inside Au@MSNs-ZOL achieved PTT, resulting in tumor growth inhibition and pain relief in mice with bone metastasis. The photothermal effect also promoted the ZOL release from the surface of Au@MSNs-ZOL, and the released ZOL inhibited farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPP synthase) for suppression of osteoclasts, providing synergistic efficacy with PTT [27].

In addition, a PEGylated hollow MnO2 (H-MnO2-PEG) MC nanostructure was developed to co-deliver DOX and chlorine e6 (Ce6, a photodynamic agent under 660 nm light irradiation) for cancer chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy (PDT), and immunotherapy (Fig. 4C). The H-MnO2-PEG-DOX/Ce6 formulation was dissociated at acidic pH inside the TME for release of drugs, and in the meanwhile H-MnO2-PEG mediated the decomposition of H2O2 into water and oxygen for relief of tumor hypoxia [31]. Following intravenous (i.v.) administration H-MnO2-PEG-DOX/Ce6 was mainly found in tumors of mice with subcutaneous breast cancer, implying efficient passive tumor accumulation of NPs. When tumors were treated with light irradiation, a significantly synergistic efficacy was achieved via chemo-photodynamic therapy. Furthermore, H-MnO2-PEG-DOX/Ce6 significantly reshaped the immunosuppressive TME, which with a combination of immune checkpoint inhibitor facilitated the abscopal effect for suppression of tumor growth at distant sites without light irradiation [31].

Mitochondrial redox homeostasis, which is a balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants, functions critically in a number of biological activities such as biosynthesis, signaling, and apoptosis [99]. As cancer cells generally possess an abnormal mitochondrial redox state that is characterized with high levels of ROS and antioxidants (e.g. glutathione, GSH), the depletion of antioxidants will cause rapid accumulation of ROS for apoptosis of cancer cells [100]. Recently, a novel MC nanoformulation has been developed to control redox homeostasis within mitochondria for increasing ROS and decreasing GSH [28]. In this study, carbon-dot NPs were used as support platform for package of highly stable and well dispersed Au atoms, and subsequently the surface of Au-containing NPs was modified with triphenylphosphine (TPP, can target mitochondrion) and cinnamaldehyde (CA, can generate ROS) achieving MitoCAT-g (Fig. 4D). Following cellular uptake of MitoCAT-g, CA was dissociated from NPs at acidic environments (e.g. endosomes) for generation of ROS. Meanwhile, Au atoms within NPs reduced the level of GSH in mitochondria by forming Au—S interactions with GSH. Consequently, the increment of ROS and reduction of GSH significantly amplified the oxidative stress and caused apoptosis of cancer cells, resulting in tumor growth inhibition in mice xenografted with either cultured HepG-2 cells or resected HCC tumors [28].

2.4. Biomimetic carriers

Recent advances in nanotechnology and an improved understanding of biological systems and cellular processes raise exciting opportunities for the design and application of biomimetic carriers for cancer therapy [101] [102] [103]. These biologically inspired carriers may be formulated using endogenous components or their analogues, which mainly consist of phospholipids (Fig. 5A), cells/cell membranes (Fig. 5B, C, D and E), and bacteria/viruses (Fig. 5F). They exhibit favorable drug delivery features in terms of high biocompatibility and biodegradability, low biological toxicities and immunogenicity, excellent tumor homing capacity, and controlled drug release (Table 1).

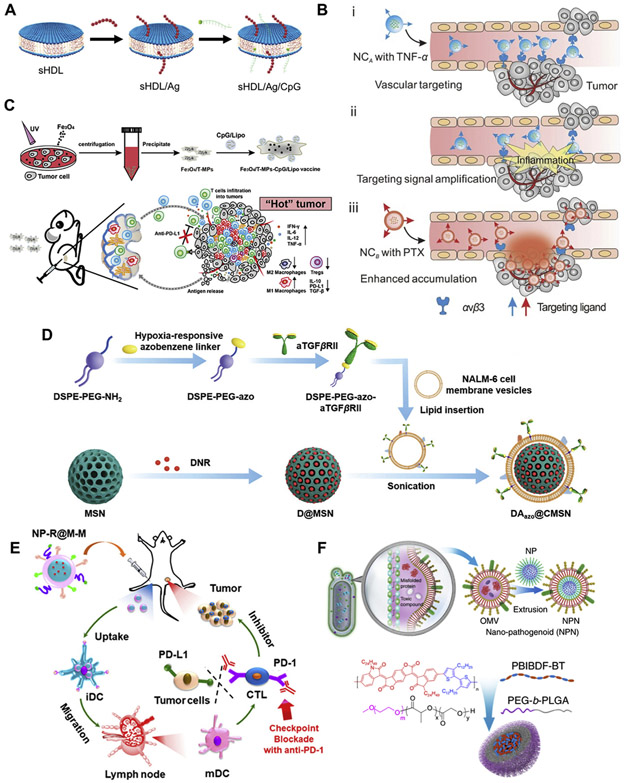

Fig. 5.

Delivery of anticancer agents using biomimetic carrier-based MC NPs. (A) High-density lipoprotein (sHDL)-based NPs for co-delivery of antigens peptides and CpG to induce immunotherapy in colorectal cancer (modified from [105]). (B) A relay drug delivery approach based on a nanogel containing TNF-α and a pH-sensitive dextran NP loaded with PTX for chemo-immunotherapy against breast cancer (Adapted from [38], copyright 2017 Wiley). (C) The tumor-derived antigenic microparticles developed to co-load CpG-lipid NPs and iron oxide NPs for immunotherapy in melanoma (Adapted with permission from [33], copyright 2019 American Chemical Society). (D) The MSNs coated with leukemia cell membranes for delivery of DNR and anti-TGF antibody in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Adapted with permission from [37], copyright 2020 Wiley). (E) PLGA NPs coated with cancer cell membranes for delivery of R837 to induce immune responses in melanoma (Adapted from [35], copyright 2018 American Chemical Society). (F) The PEG-PLGA/PBT and PEG-PLGA/cisplatin coated with bacteria-secreted outer membranes respectively for photothermal therapy and chemotherapy in breast and colorectal cancers (Adapted from [39], copyright 2020 Nature Publishing Group).

It was reported that the anticancer efficacy of peptide-based vaccines is limited due to inefficient co-delivery of antigen (Ag) peptides and adjuvants into lymphoid organs, poor presentation of antigens to DCs, and the inactivation, exhaustion and deletion of T lymphocytes [104]. To overcome these limitations, a high-density lipoprotein (sHDL) was synthesized using phospholipid and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1)-like peptide [105]. This sHDL formed a discoid nanocarrier to co-load Ag peptides and cholesterol-linked 5’-C-phosphate-G-3′ [CpG, a strong TLR-9 agonist] for generation of homogenous (polydispersity index of 0.2), stable (up to 30 days when stored at 4 °C), and ultrasmall (~10 nm) MC nanostructures (Fig. 5A). Following subcutaneous administration, the resultant co-formulation could efficiently deliver Ag and CpG to draining lymph nodes for robust Ag presentation by DCs, resulting in strong and durable Ag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in CRC and melanoma mouse models [105].

As discussed above, liposomes as conventional biomimetic carriers have been widely used for cancer nanomedicine. However, liposomes are not fully capable of reproducing the property and function of biological membranes due to their relatively simple structures. Alternatively, emerging evidence indicates the great promise for development of biomimetic carriers using entire cells [e.g. red blood cells (RBCs), platelets and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)], biological membranes (e.g. RBC membrane, platelet membrane, leukocyte membrane, MSC membrane and cancer cell membrane), and extracellular vesicles (e.g. exosomes) [106]. It is well established that a hallmark of inflammation or trauma is characterized by inflammation-triggered neutrophil assembly and damaged blood vessel-induced platelet accumulation [107]. Based on these physiological activities, a relay drug delivery approach was designed as follows [38]: 1) a nanogel containing tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) was produced by the single emulsion method and modified with the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide (it can selectively target integrins that are highly expressed on tumor blood vasculatures) and 2) a pH-sensitive dextran NP loaded with paclitaxel (PTX) was coated with platelet membranes (Fig. 5B). The RGD-nanogel could preferentially target tumor blood vasculatures via the interaction between RGD and integrins, and the TNF-α was then released to trigger vascular damage by activating the inflammation cascade signals [38]. Subsequently, the platelet membrane-coated dextran NPs were specifically accumulated inside tumors due to the relay action between vascular damage signals and platelets, and the encapsulated PTX was released to destroy microtubules of cancer cells. Consequently, this relay delivery strategy successfully inhibited the tumor growth in breast cancer mice [38]. In addition, It has been reported that primary tumor cells can invade vascular systems, enter the systemic circulation, and form cell colonies at distal sites for metastases [108]. This metastatic process is highly relied on the interactions between capillary endothelial cells and circulating tumor cells, and the interactions are mediated by cell-surface receptors and adhesion molecules on host cells and cancer cells [109]. Recently, a cancer cell membrane-coated NP was developed for delivery of PTX to the same type of tumor at primary and distal sites [36]. In this MC nanostructure (termed CPPNs), the core was formed with PTX-containing polymeric NPs [poly(caprolactone) and Pluronic F68], which was coated with 4 T1 cell membranes. Consequently, CPPNs were selectively accumulated into primary and metastatic sites of 4 T1 orthotopic and metastatic mouse models, significantly resulting in inhibition of tumor growth [36].

A summary of recent studies on the in vivo delivery of MC NPs in cancer therapy are described in Table 1, including: formulation materials, therapeutic cargos, cancer types, routes of administration, animal models, and endpoint comments.

3. Recent advances in design of Membrane-core nanoparticles - potential for cancer nanomedicine

Over the past decades significant advances have been achieved in the field of NP-based delivery systems, resulting in several Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nanomedicines for cancer therapy [110], from Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin) for Kaposi sarcoma, ovarian cancer and multiple myeloma in 1995 to Onivyde® (liposomal irinotecan) for pancreatic cancer in 2015 (see a list of marketed products in [111]). However, the number of nanotherapeutics approved for cancer patients is still very few relative to numerous publications and start-ups. The failure of clinical translation is mainly attributed to the complexity and dynamics of cancers. Therefore, it is critical to fully understand the delivery barriers from administration to arrival at the tumor site, which will facilitate the design of MC NPs for improving pharmacokinetics, enhancing tumor biodistribution, and achieving therapeutic efficacy in tumors.

3.1. In vivo delivery barriers

3.1.1. Blood circulation

Although the local administration of nanomedicines demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in superficially placed tumors, the systemic administration of nanotherapeutics into blood circulation is more desirable for tumors deeply inside the body (particularly for metastases). It is well known that particle size functions critically on the duration of NPs in the bloodstream. NPs with particle sizes of 5.5 nm or smaller may be removed from blood circulation and excreted via renal filtration [112], while those with hydrodynamic diameters of 10 nm or bigger may avoid glomerular clearance [113]. The discontinuous endothelia with vascular fenestrae (~50 to 100 nm) in the liver potentially lead to non-specific accumulation of ~10 to 100 nm NPs [114]. Moreover, >200 nm NPs may cause high retention into the spleen due to the size range (~200 to 500 nm) of inter-endothelial cell slits [115]. Therefore, NPs with an “ideal” size of ~100 to 200 nm are potentially able to overcome the aforementioned delivery barriers encountered during blood circulation.

In addition, ~10 to 100 nm NPs cause significant assembly in Kupffer cells in the liver, while >100 nm NPs may be recognized by the mononuclear phagocytic system [MPS, it is part of the immune system, which is mainly composed of monocytes and macrophages in the liver (Kupffer cells), spleen, and lymph nodes] [116]. These lead to poor pharmacokinetics of NPs. Moreover, the surface of NPs may be non-specifically bound with serum proteins via either the effect between hydrophobic groups on proteins and hydrophobic moieties on NPs, or, the interaction between ions on proteins and ions on NPs [117]. These increase the NP size, causing uptake of larger particles by the MPS. To form a “stealth” formulation for long-term blood circulation, the surface grafting of NPs with stabilizing moieties has been extensively studied [118] [119]. For example, the modification of PEG (a highly hydrophilic polymer) may provide a hydrated layer that sterically keeps NPs from non-specific absorption of neighboring NPs or serum proteins. The impact of PEGylation on half-life of NPs in the bloodstream has been substantially discussed in terms of molecular weight, surface density, and conformation [118]. In addition, NPs with surface coating of biomimetic carriers (section 2.4) may be recognized as the “self” and thus avoid unwanted immune responses or rapid removal from the body [119]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that NPs with RBC-membrane coating achieved longer half-lives as compared to counterparts with PEG coating [120] [121] [122], suggesting that biomimetic carriers are a potential alternative to PEG or other polymeric materials such as poly(carboxybetaine) [123] and poly(sulfobetaine) [124], with respect to the pharmacokinetic profiles.

3.1.2. Tumor distribution

In contrast to the tight blood vessels in healthy organs, the blood vessels in rapidly growing tumors possess leaky vasculature gaps. The permeable vasculature may facilitate entry of NPs with particle sizes of <500 nm into tumors, and due to the poor lymphatic drainage system, NPs are trapped within the tumor bed [125]. This “passive” tumor accumulation of NPs is termed as the “enhanced permeability and retention” (EPR) effect. Furthermore, NPs may also be modified with targeting ligands to recognize the receptors uniquely found or overexpressed on tumor tissues, and when targeted NPs arrive at the tumor bed via the EPR effect, they may specifically target cells of interest via ligand-receptor-mediated pathways [126].

However, increasing knowledge raises significant debate about the contribution of the EPR effect on the improvement of NP-based drug delivery at tumor sites. Clinical studies reveal that the efficiency of the EPR effect is varied and can be affected by tumor type and size [127]. Accordingly, traceable NPs (e.g. SPIONs) may be applied as imaging guides to determine patients who are likely benefit from nanomedicine in terms of the EPR effect [128]. Moreover, NP delivery based on the EPR effect is limited due to the fact that the rate of leakage from tumor vessels is no more than 2-fold increment in comparison with that from healthy vessels [129]. Therefore, the development of novel strategies for better leakage and deeper penetration of drug delivery into tumor sites is highly welcome [130]. For example, a liposomal NP containing hydralazine (HDZ, it is used for high blood pressure) was formulated for modulating blood vessels of desmoplastic melanoma [131]. Following systemic administration of liposomal HDZ, the tumor permeability was significantly enhanced, which significantly fostered anticancer outcomes of liposomal DOX as second wave of treatment in tumor-bearing animals.

In addition to the EPR effect that allows “passive” accumulation, the “active” transport (e.g. transcytosis) may also be involved in NP extravasation at tumor sites [132]. Transcytosis is known as a type of transcellular transport by which a variety of macromolecules are carried from one side of the cell to the other (see details in [133]). Recently, a mechanistic study on the entry of NPs into tumors has been reported [134]. In this work, the tumor distribution of AuNPs (15, 50 and 100 nm) was investigated using different tools (inductively coupled plasma/mass spectrometry, transmission electron microscopy and 3D imaging) in four tumor-bearing mouse models (U87-MG subcutaneous xenograft glioma, 4 T1 orthotopic syngeneic breast cancer, MMTV-PyMT transgenic breast cancer, and patient-derived xenograft breast cancer) [134]. Following i.v. injection of AuNPs, the whole animal was fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA), and the tumor blood vessels were examined to determine the pathways for NP extravasation. As a result, AuNPs of three particle sizes were mainly found within the vesicles and cytoplasm and along the membrane of the endothelial cells of tumor vessels, indicating that AuNPs extravasate into tumors via transcytosis [134]. In separate experiments, tumor-bearing animals were first treated with PFA to block the morphological changes associated with transcytosis while maintaining the vessel architecture. Subsequently, the systemic circulation of NPs in the PFA-fixed animals was achieved using transcardial perfusion at a constant flow rate (~5 to 7 mL/min). Consequently, the amount of AuNPs found in tumor tissues was significantly decreased, demonstrating the dominant role of transcytosis in NP diffusion into tumors [134]. These results provide insights into understanding the “active” transport of NPs for improvement of tumor accumulation.

3.1.3. Tumor microenvironment

The TME is characterized as a highly complex environment surrounding tumors, and the interactions between cells and non-cell components within the TME provide a supporting soil for tumor initiation, development, and metastasis [135]. The heterogeneity inside the TME [e.g. hypoxia and dense extracellular matrix (ECM)] cause resistance to drug delivery, which has been substantially discussed elsewhere [136].

As a hallmark feature of tumors, hypoxia is often associated with the TME development characterized by variable oxygen concentrations, reduced pH, and increased ROS. Based on these features, hypoxiatriggered NPs have been developed for delivery of anticancer agents to treat a variety of tumors [137]. For example, a multifunctional copolymer (CP) was synthesized using three monomers including fluorene (it is a unit for blue emitting), dithiophene benzotriazole (it is a sensitizer to generate singlet oxygen), and dithiophene thienopyrazine (it is a unit for shifting emission maximum into NIR wavelengths) [138]. Subsequently, CP was modified by 2-nitroimidazole (NI, it is a hypoxia-sensitive water-insoluble moiety that is converted into water-soluble 2-aminoimidazoles under hypoxic environments). DOX was then packaged into CP-NI via a double-emulsion solvent evaporation method. This CP-NI/DOX was further coated with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) to form a light-stimulated hypoxia-sensitive MC nanoformulation [138]. I.V. administration of CP-NI/DOX/PVA demonstrated a long-term blood circulation due to the PVA shell and penetrated into tumor sites by the EPR effect. When tumors were irradiated with the light (532 nm and 0.28 W/cm2), this nanoformulation effectively achieved the singlet oxygen generation for PDT and the DOX release for chemotherapy [138].

In addition, high density of ECM also hinders the deep trafficking of NPs into tumors. As the primary source of ECM, fibroblasts become activated in tumors leading to the secretion of ECM components at higher levels than the inactivated counterparts of healthy tissues. Therefore, NP-based delivery strategies have been developed to target fibroblasts for overcoming ECM barriers [136]. For example, puerarin (an isoflavone extract original from the kudzu root) is able to decrease the myocardial oxygen consumption, control the blood sugar, and lower the ischemia reperfusion harm [139]. It has been reported that puerarin demonstrates a robust anti-fibrotic effect in different organs (e.g. the heart, liver and kidneys) [139]. Recently, a puerarin nanoemulsion (Nano-Pue) was developed to deactivate the stromal TME [140]. Nano-Pue was formulated with high encapsulation efficiency (~82%) using biocompatible lecithin from soybean as the emulsifier and post-modified with DSPE-PEG-AEAA for targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs, one of the most abundant stromal cells) (Fig. 3F). Results show that Nano-Pue achieved significantly higher in vivo reduction of TAFs (~6 folds) relative to negative controls, resulting in the removal of physical barrier associated with TME. Consequently, nano-PTX (ZY Therapeutics Inc.) as a second-wave treatment was accumulated inside tumors of mice with 4 T1 orthotopic breast cancer, resulting in synergistic chemo-immunotherapeutic efficacy in combination with anti-PD-L1 antibody [140].

Moreover, a number of stimuli-responsive NPs in responsive to internal physiological stimuli (including pH change, redox potential, enzymes and biomolecules) and to external physical stimuli (including light, heat, and ultrasound) have recently been developed (see review in [141] [142]), in order to achieve efficient and safe delivery of anticancer agents in the bloodstream and to foster therapeutic efficacy at both primary lesions and distant metastases [143].

3.2. Recent advances of membrane-core nanoparticles for cancer nanomedicine

Recently, the developments of MC nanostructured delivery strategies for transporting chemotherapeutics, nucleic acids and immunomodulators have been significantly advanced for cancer therapy. Selected recent examples of MC NPs that are currently under investigation for cancer nanomedicine will be highlighted in this section, with emphasis on those designed to promise clinical translation.

3.2.1. Chemotherapy

As discussed above, TAFs as one of the most abundant stromal cells play key roles in desmoplastic reaction that is highly associated with drug resistance and the formation of immunosuppressive TME. Recently, a biomimetic lipoprotein-based NP (bLP) containing photothermal agent DiOC18(7) (termed D-bLP) was developed for effective PTT to reshape the stromal TME [40]. Following 808 nm laser irradiation onto tumors, D-bLP significantly improved the accessibility of second-wave bLP NP containing mertansine (termed M-bLP) into cancer cells, which produced profound tumor suppression and metastasis inhibition of 4 T1 breast cancer models [40].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) cause resistance to currently available therapies, therefore, strategies that specifically target CSCs will promote cancer treatment and reduce side effects. Recently, a MC nanoformulation was developed to co-encapsulate thioridazine (THZ, an anti-CSC agent), PTX, and HY19991 (HY, an inhibitor for PD-1/PD-L1 axis) [11]. In this study, a pH-trigger copolymer, PEG-block-poly[(1,4-butanediol)-diacrylate-β-N,N-diisopropylethylenediamine] (termed PDB) was generated to load PTX. Subsequently, PDB/PTX, THZ, and HY were co-encapsulated into micelle-liposome nanostructures consisting of cholesterol, soybean phosphatidylcholine, and a matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive copolymer, PEG-peptide-vitamin E succinate. This NP-based cocktail approach demonstrated long-term blood circulation, increased drug concentrations, and facilitated spatiotemporally controllable drug release in tumors, which significantly reduced the population of bulk cancer cells and CSCs and fostered the infiltration of T cells, resulting in tumor regression and metastasis inhibition in mice with breast cancer [11].

3.2.2. Gene therapy

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as one of key cell types in the TME have gained significant attention due to their roles in supporting tumors and conferring therapy resistance. TAMs express pro-tumoral and immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, therefore, repolarization of M2 cells into M1 cells (anti-tumoral and pro-inflammatory phenotype) will facilitate anti-tumor activities [144]. Recently, a targeted nanoformulation has been developed for delivery of mRNA encoding transcription factors for M1 polarization [24]. In this study, mRNAs were electrostatically complexed by cationic poly (β-amino ester) (PbAE), and the PbAE.mRNA was subsequently packaged within polyglutamic acid (PGA) that was pre-conjugated with Di-mannose for specifically targeting macrophage mannose receptor 1 (MRC1, also known as CD206). The PGA.PbAE.mRNA nanoformulation achieved co-expression of Interferon Regulatory Factor 5 (IRF5) and IKKβ (a kinase for IRF5 activation), which successfully converted TAMs into the cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and facilitate tumor inhibition in mice with ovarian cancer, melanoma, and glioblastoma [24].

It is known that targeted therapies are currently lacking in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), while chemotherapy as the only approved method for TNBC causes low efficacy but high side effects. The deletion or mutation of TP53 impair the p53 tumor suppressor function. As POLR2A is one of irreplaceable neighboring genes of TP53, the inhibition of POLR2A also demonstrates therapeutic potential for TNBC with hemizygous loss of TP53 (TP53loss) [145]. Small interference RNA (siRNA) can potentially downregulate the expression of virtually any genes, providing a great promise for inhibition of POLR2A. Therefore, a pH-sensitive NP (termed nano-bomb) was designed to transport siRNA against POLR2A (siPol2) in TP53loss TNBC [19]. In this study, siRNA was electrostatically complexed with guanidine-modified chitosan (CG), and the guanidine moiety of CG was reacted with CO2 to form CG-CO2 in a pH-sensitive manner (CO2 is stable at physiological pH but can be released at acidic environments such as endosomes and lysosomes). The siRNA/CG-CO2 was encapsulated within PLGA and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) to form MC nanoformulation termed siPol2@NPs. Consequently, siPol2@NPs triggered endosomal escape of siRNA for effective intracellular trafficking, which significantly suppressed the expression of POLR2A and inhibited tumor growth in orthotopic TNBC mice [19].

3.2.2. Immunotherapy

Delivery of tumor antigens and adjuvants into lymph nodes demonstrates great potential for enhancing immunotherapeutic efficacy in cancers; however, this strategy is seriously retarded by the lack of appropriate tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and robust delivery systems. It has been reported that melittin as a component of bee venom induces necrosis and apoptosis of cancer cells for release of TAAs [146]. In addition, melittin is a host defense peptide, and can regulate various immunomodulatory effects [147]. However, melittin-mediated immunotherapeutic effects are compromised due to high toxicities and side effects. Recently, a lipid-based NP was developed using cholesterol oleate (CO) and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) for delivery of melittin [148]. Following intratumor injection, the resultant nanoformulation (melittin-NP) caused tumor cell necrosis and apoptosis, causing the release of TAAs in situ and bypassing the requirement of TAA loading into nanovaccines. Furthermore, melittin-NP could be transported into lymph nodes in which melittin fully exerted immunomodulatory effects to activate antigen presenting cells (e.g. DCs and macrophages). As a consequent, the vaccination of melittin-NP effectively induced systemic humoral/cellular anticancer immunities, leading to inhibition of ~70% of primary tumors and 50% of distant tumors in a bilateral flank melanoma mouse model [148].

It is now known that the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) critically regulates intracellular DNA-triggered interferon-dependent innate immunity [149]. Cyclic dinucleotide (CDN) agonists of STING may mediate antitumor immune responses [150]; however, the poor physicochemical features (e.g. hydrophilic backbone, anionic surface and instability) significantly limit the application of CDN agonists for cancer therapy. Recently, a PEG-block-[(2-diethylaminoethyl methacrylate)-co-(butyl methacrylate)-co-(pyridyl disulfide ethyl methacrylate)] copolymer was produced (termed polymersome) [26]. Polymersomes were subsequently modified with pH-triggered, positively charged 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate moieties and lipophilic butyl methacrylate groups, which promote cytosolic trafficking of 2′3′ cyclic guano-sine monophosphate/adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP) [26]. The obtained MC nanoformulation containing cGAMP successfully induced STING in both lymph nodes and the TME, leading to tumor inhibition and long-term survival rate of mice with melanoma [26]. In addition, a library of over 1000 ionizable lipid-like materials have recently been produced for delivery of mRNA vaccines in vivo to induce specific and robust STING-based immune responses [13]. The top-performing candidates, which demonstrated a similar structure with a non-saturated lipid-tail, a dihydroimidazole group and cyclic-amine head moieties, could stimulate STING pathway. These STING-triggered lipids were used to electrostatically complex with mRNA vaccines to form a MC nanoformulation. Consequently, the resultant nanoformulations simultaneously delivered mRNA and activated the anticancer immunity, which inhibited tumor progression and prolonged life span of mice with melanoma and papillomavirus E7 tumor [13].

3.3. Challenges for clinical translation of membrane-core nanoparticles

Despite substantial advances, the number of cancer nanomedicines approved for patients is still few, which is attributed to the complexity and dynamics of cancers. Therefore, it is really of critical importance to obtain better understanding in structural and physiological hurdles associated with NP delivery from administration to arrival at the tumor site (as discussed in section 3.1), which will facilitate the design of multifunctional MC NPs for improving cancer therapy. However, MC NPs formulated using distinct functional materials may induce unexpected toxic issues, causing a hurdle for clinical application [151] [152]. Recent developments in green chemistry have enabled the synthesis of nanomaterials by minimizing the use of hazardous constituents (see details in [153] [154] [155]), therefore alleviating the adverse effects of nanomedicines on the human body. Consequently, the application of green chemistry may potentially facilitate the formulation of multifunctional MC NPs to achieve “green nanomedicines” with better biocompatibility and lower toxicity.

It is also worth noting that the synthesis of MC NPs with multifunctional modifications can complicate large-scale production and cause variation from batch to batch. In order to achieve nanomedicines at the industrial level, operationally simple and reliable approaches are highly desirable. Recently, flow chemistry has received increasing attention due to its capacity for manufacturing highly functionalized and chiral chemicals (e.g. natural products [156] and active pharmaceutical ingredients [157]). In contrast to traditional batch chemistry processes, flow chemistry techniques allow highly flexible modulations to accomplish on demand synthesis in a fully automated continuous pattern [158]. Nanomaterials with desired properties (e.g. size, charge, shape and surface composition) can be achieved using a variety of continuous flow approaches by adjusting key synthesis parameters including temperature, mixing ratio, concentration, and reaction time (see selective examples in [159] [160] [161] [162]). Therefore, continuous flow technologies may be utilized to formulate reproducible and controlled nanomedicines at large scale for satisfying clinical scenario [163].

4. Conclusion

Recent developments of small molecule inhibitors, gene medicines and immunomodulators have profoundly revolutionized the field of cancer therapy. However, the application of these medical products to cancer patients is retarded by limitations such as drug resistance, non-specific delivery, and toxicity. The membrane-core (MC) nanostructure facilitates a combination of materials with different features and functions, leading to the design of multifunctional NPs with high drug solubility, loading, stability and bioavailability, efficient drug targeting and release, and low toxicity and side effects (Fig. 1). In addition, the physicochemical and biological characteristics of MC NPs may be adjusted to overcome in vivo delivery barriers such as poor pharmacokinetics, non-specific tissue distribution, and pro-tumoral and immunosuppressive TME (Figs. 2 to 5). Indeed, extensive research has demonstrated the potential of MC NPs for providing safe, effective, and patient-acceptable cancer nanomedicines (Table 1). Furthermore, challenges such as nanotoxicity and scalable/reproducible production still delay the application of nanomedicines for cancer patients. Therefore, these challenges should be addressed in the future for achieving clinical translation [164] [165].

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by the Carolina Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence, United States (NIH grant CA198999) (to L.H.) and by Talents Cultivation Program of Jilin University (to J.G.), China.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

L.H. is a consultant with PDS Biotechnology, Samyang Biopharmaceutical Co., Stemirna and Beijing Inno Medicine. J.G. declares no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL, Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019, CA Cancer J. Clin 69 (2019) 363–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hanahan D, Rethinking the war on cancer, Lancet 383 (2014) 558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM, Peer D, Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ghosh Chaudhuri R, Paria S, Core/shell nanoparticles: classes, properties, synthesis mechanisms, characterization, and applications, Chem. Rev 112 (2012) 2373–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Song W, Shen L, Wang Y, Liu Q, Goodwin TJ, Li J, Dorosheva O, Liu T, Liu R, Huang L, Synergistic and low adverse effect cancer immunotherapy by immunogenic chemotherapy and locally expressed PD-L1 trap, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Song W, Tiruthani K, Wang Y, Shen L, Hu M, Dorosheva O, Qiu K, Kinghorn KA, Liu R, Huang L, Trapping of lipopolysaccharide to promote immunotherapy against colorectal Cancer and attenuate liver metastasis, Adv. Mater 30 (2018), e1805007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shen L, Li J, Liu Q, Song W, Zhang X, Tiruthani K, Hu H, Das M, Goodwin TJ, Liu R, Huang L, Local blockade of interleukin 10 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 with Nano-delivery promotes antitumor response in murine cancers, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 9830–9841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hu M, Wang Y, Xu L, An S, Tang Y, Zhou X, Li J, Liu R, Huang L, Relaxin gene delivery mitigates liver metastasis and synergizes with check point therapy, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goodwin TJ, Zhou Y, Musetti SN, Liu R, Huang L, Local and transient gene expression primes the liver to resist cancer metastasis, Sci Transl Med, 8 (2016) 364ra153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chan C, Guo N, Duan X, Han W, Xue L, Bryan D, Wightman SC, Khodarev NN, Weichselbaum RR, Lin W, Systemic miRNA delivery by nontoxic nanoscale coordination polymers limits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and suppresses liver metastases of colorectal cancer, Biomaterials 210 (2019) 94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lang T, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Ran W, Zhai Y, Yin Q, Zhang P, Li Y, Cocktail strategy based on Spatio-temporally controlled Nano device improves therapy of breast Cancer, Adv. Mater 31 (2019), e1806202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Duan X, Chan C, Han W, Guo N, Weichselbaum RR, Lin W, Immunostimulatory nanomedicines synergize with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy to eradicate colorectal tumors, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Miao L, Li L, Huang Y, Delcassian D, Chahal J, Han J, Shi Y, Sadtler K, Gao W, Lin J, Doloff JC, Langer R, Anderson DG, Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation, Nat. Biotechnol 37 (2019) 1174–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kedmi R, Veiga N, Ramishetti S, Goldsmith M, Rosenblum D, Dammes N, Hazan-Halevy I, Nahary L, Leviatan-Ben-Arye S, Harlev M, Behlke M, Benhar I, Lieberman J, Peer D, A modular platform for targeted RNAi therapeutics, Nat. Nanotechnol 13 (2018) 214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Qian Y, Qiao S, Dai Y, Xu G, Dai B, Lu L, Yu X, Luo Q, Zhang Z, Molecular-targeted immunotherapeutic strategy for melanoma via dual-targeting nanoparticles delivering small interfering RNA to tumor-associated macrophages, ACS Nano 11 (2017) 9536–9549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kulkarni A, Chandrasekar V, Natarajan SK, Ramesh A, Pandey P, Nirgud J, Bhatnagar H, Ashok D, Ajay AK, Sengupta S, A designer self-assembled supramolecule amplifies macrophage immune responses against aggressive cancer, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2 (2018) 589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ramesh A, Kumar S, Nandi D, Kulkarni A, CSF1R- and SHP2-inhibitor-loaded nanoparticles enhance cytotoxic activity and phagocytosis in tumor-associated macrophages, Adv. Mater 31 (2019), e1904364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Conniot J, Scomparin A, Peres C, Yeini E, Pozzi S, Matos AI, Kleiner R, Moura LIF, Zupancic E, Viana AS, Doron H, Gois PMP, Erez N, Jung S, Satchi-Fainaro R, Florindo HF, Immunization with mannosylated nanovaccines and inhibition of the immune-suppressing microenvironment sensitizes melanoma to immune checkpoint modulators, Nat. Nanotechnol 14 (2019) 891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xu J, Liu Y, Li Y, Wang H, Stewart S, Van der Jeught K, Agarwal P, Zhang Y, Liu S, Zhao G, Wan J, Lu X, He X, Precise targeting of POLR2A as a therapeutic strategy for human triple negative breast cancer, Nat. Nanotechnol 14 (2019) 388–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shi C, Liu T, Guo Z, Zhuang R, Zhang X, Chen X, Reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages by nanoparticle-based reactive oxygen species Photogeneration, Nano Lett. 18 (2018) 7330–7342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Da Silva CG, Camps MGM, Li TMWY, Chan AB, Ossendorp F, Cruz LJ, Codelivery of immunomodulators in biodegradable nanoparticles improves therapeutic efficacy of cancer vaccines, Biomaterials 220 (2019) 119417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang C, Ni D, Liu Y, Yao H, Bu W, Shi J, Magnesium silicide nanoparticles as a deoxygenation agent for cancer starvation therapy, Nat. Nanotechnol 12 (2017) 378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rodell CB, Arlauckas SP, Cuccarese MF, Garris CS, Li R, Ahmed MS, Kohler RH, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R, TLR7/8-agonist-loaded nanoparticles promote the polarization of tumour-associated macrophages to enhance cancer immunotherapy, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2 (2018) 578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhang F, Parayath NN, Ene CI, Stephan SB, Koehne AL, Coon ME, Holland EC, Stephan MT, Genetic programming of macrophages to perform anti-tumor functions using targeted mRNA nanocarriers, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu Q, Chen F, Hou L, Shen L, Zhang X, Wang D, Huang L, Nanocarrier-mediated chemo-immunotherapy arrested Cancer progression and induced tumor dormancy in desmoplastic melanoma, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 7812–7825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shae D, Becker KW, Christov P, Yun DS, Lytton-Jean AKR, Sevimli S, Ascano M, Kelley M, Johnson DB, Balko JM, Wilson JT, Endosomolytic polymersomes increase the activity of cyclic dinucleotide STING agonists to enhance cancer immunotherapy, Nat. Nanotechnol 14 (2019) 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sun W, Ge K, Jin Y, Han Y, Zhang H, Zhou G, Yang X, Liu D, Liu H, Liang XJ, Zhang J, Bone-targeted Nanoplatform combining Zoledronate and Photothermal therapy to treat breast Cancer bone metastasis, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 7556–7567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gong N, Ma X, Ye X, Zhou Q, Chen X, Tan X, Yao S, Huo S, Zhang T, Chen S, Teng X, Hu X, Yu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li J, Liang XJ, Carbon-dot-supported atomically dispersed gold as a mitochondrial oxidative stress amplifier for cancer treatment, Nat. Nanotechnol 14 (2019) 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen Q, Wang C, Zhang X, Chen G, Hu Q, Li H, Wang J, Wen D, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Yang G, Jiang C, Wang J, Dotti G, Gu Z, In situ sprayed bioresponsive immunotherapeutic gel for post-surgical cancer treatment, Nat. Nanotechnol 14 (2019) 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gao S, Jin Y, Ge K, Li Z, Liu H, Dai X, Zhang Y, Chen S, Liang X, Zhang J, Selfsupply of O2 and H2O2 by a Nanocatalytic medicine to enhance combined chemo/Chemodynamic therapy, Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 6 (2019) 1902137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yang G, Xu L, Chao Y, Xu J, Sun X, Wu Y, Peng R, Liu Z, Hollow MnO2 as a tumor-microenvironment-responsive biodegradable nano-platform for combination therapy favoring antitumor immune responses, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rong L, Zhang Y, Li WS, Su Z, Fadhil JI, Zhang C, Iron chelated melanin-like nanoparticles for tumor-associated macrophage repolarization and cancer therapy, Biomaterials 225 (2019) 119515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhao H, Zhao B, Wu L, Xiao H, Ding K, Zheng C, Song Q, Sun L, Wang L, Zhang Z, Amplified Cancer immunotherapy of a surface-engineered antigenic microparticle vaccine by synergistically modulating tumor microenvironment, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 12553–12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kroll AV, Fang RH, Jiang Y, Zhou J, Wei X, Yu CL, Gao J, Luk BT, Dehaini D, Gao W, Zhang L, Nanoparticulate delivery of Cancer cell membrane elicits multiantigenic antitumor immunity, Adv. Mater 29 (2017) 1703969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang R, Xu J, Xu L, Sun X, Chen Q, Zhao Y, Peng R, Liu Z, Cancer cell membrane-coated adjuvant nanoparticles with mannose modification for effective anticancer vaccination, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 5121–5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sun H, Su J, Meng Q, Yin Q, Chen L, Gu W, Zhang P, Zhang Z, Yu H, Wang S, Li Y, Cancer-cell-biomimetic nanoparticles for targeted therapy of homotypic tumors, Adv. Mater 28 (2016) 9581–9588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dong X, Mu LL, Liu XL, Zhu H, Yang SC, Lai X, Liu HJ, Feng HY, Lu Q, Zhou BBS, Chen HZ, Chen GQ, Lovell JF, Hong DL, Fang C, Biomimetic, hypoxia-responsive nanoparticles overcome residual Chemoresistant leukemic cells with co-targeting of therapy-induced bone marrow niches, Adv. Funct. Mater 30 (2020) 2000309. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hu Q, Sun W, Qian C, Bomba HN, Xin H, Gu Z, Relay drug delivery for amplifying targeting signal and enhancing anticancer efficacy, Adv. Mater 29 (2017) 1605803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li M, Li S, Zhou H, Tang X, Wu Y, Jiang W, Tian Z, Zhou X, Yang X, Wang Y, Chemotaxis-driven delivery of nano-pathogenoids for complete eradication of tumors post-phototherapy, Nat. Commun 11 (2020) 1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tan T, Hu H, Wang H, Li J, Wang Z, Wang J, Wang S, Zhang Z, Li Y, Bioinspired lipoproteins-mediated photothermia remodels tumor stroma to improve cancer cell accessibility of second nanoparticles, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Torchilin VP, Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 4 (2005) 145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].O’Driscoll CM, Griffin BT, Biopharmaceutical challenges associated with drugs with low aqueous solubility–the potential impact of lipid-based formulations, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 60 (2008) 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]